David Boyle's Blog, page 77

June 30, 2013

Why Crystal Palace is the next Islington, worse luck

Ah yes, the Crystal Palace Festival. It has been taking place this weekend, and it helped me see the place a little more clearly, even though I've lived there since 1986.

It has crept up on my how much the place has changed. It is now packed full of the kind of cultural entrepreneurial people I say in my book Broke are going to save the middle classes - and everyone else. Poets, breadmakers, writers, local publishers, local food distributors, a Transition Towns branch, Green & Browns at Crystal Palace Station, musicians, artists, designers, even a baby sling library, for goodness sake.

What is more, the place was packed without generating extra traffic in the local streets. This was overwhelmingly homegrown.

Part of the apotheosis of Crystal Palace has been the opening of the Overground line to Hackney, Canada Water and Islington, but that isn't the cause. You can't conjure up these kind of people in a year or so.

My prediction is that, in fifteen years time, Crystal Palace will be like Islington - exorbitant house prices, lawyers and, given the way our dysfunctional property market squeezes the life out of places, no entrepreneurs at all.

I wonder also whether it is the fact that it is below the radar of local government - an irritation to Croydon and Lambeth which slashed the local library, and a thorn in the side of Bromley which constantly wants to develop the park. Being on the corner of no less than five boroughs encourages a degree of benign neglect. I wonder whether, if Crystal Palace had been the heart of the London Borough of Norwood or something, they would have got Lend Lease in to build a shopping centre and destroyed the local economy altogether.

I met a retired senior officer from Bromley Council a year or so ago who agreed with me about the constant stand-off between the council and the residents about the park: the council thought it was a poor people's park - and poor people's parks, as we all know, have to pay their way and are endlessly messed around with and sold off (as in Ankara). Because Crystal Palace was so far from anywhere, they hadn't realised the ferocity with which people would defend its unkempt, untended, unofficial atmosphere.

So I'm proud to live here. In another era, I would be undoubtedly be campaigning for a Crystal Palace Unilateral Declaration of Independence. I just can't face the chore of climbing down onto the Overground to inspect people's passports.

Published on June 30, 2013 00:34

June 29, 2013

The secret of where those 1970s motorways came from

My blog yesterday about the roads programme in the 1970s, and what a disaster it was - despite the Treasury's enthusiasm for it in their recent announcement - has brought a whole lot of half forgotten thoughts bubbling, as thoughts do, to the surface. And some new ones entirely.

My blog yesterday about the roads programme in the 1970s, and what a disaster it was - despite the Treasury's enthusiasm for it in their recent announcement - has brought a whole lot of half forgotten thoughts bubbling, as thoughts do, to the surface. And some new ones entirely.First, thanks to Gareth Aubrey, I've read an absolutely fascinating website about the unbuilt motorways and bypasses of Britain. More about that in a moment.

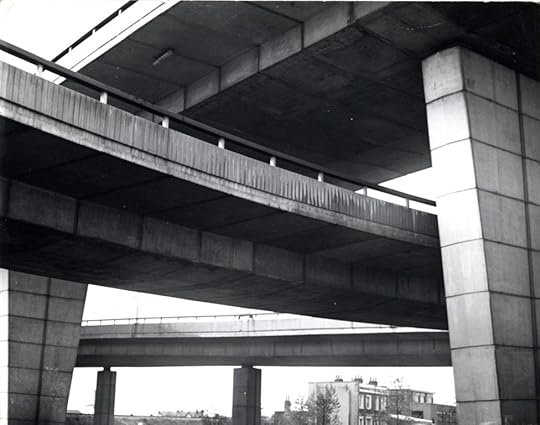

The second thing I remembered was one of the first public meetings I ever went to. I can't remember where it was exactly, only that it was organised by the Paddington Waterways Society, which played rather an important role in my upbringing, because my mother was the secretary. It was probably in 1970 and was about the Westway flyover (pictured above), then looming in concrete and bitumen over our neighbourhood in Maida Vale. I'm not sure how I came to be there.

"It is like a gun aimed directly at Islington," said one contributor, and there just dimly was the idea of how the frenetic road-building of the 1970s had also created the subsidised traffic that soon came to clog it.

And it could have been so much worse, as anyone can see driving along Westway today, with all the blocked exits that never quite became slip roads. The terrible blight on so many cities by inner urban motorways on both sides of the Atlantic in the 1970s never quite came to fruition in London.

But as the website Pathetic Motorways says, it so nearly did. This is their description of the extraordinary saga of the London Motorway Box, as the media called it, the little-lamented Ringways plan for London. It was eventually scuppered when the GLC changed hands in 1975, but it was no coincidence that the Brixton Riots six years later took place in an area that had been blighted for more than a decade by the Motorway Box plan.

All of which is a way of saying that a shiver went down my spine on Thursday when the Treasury announced with pride "the biggest investment in our roads since the 1970s". Does nobody remember the roads programme of the 1970s?

In fact, given the investment planned on another generation of nuclear white elephants, perhaps nobody remembers the 1970s at all - and Windscale, Dounreay, Torness and all the rest of those vast capital black holes, all bundled up in the huge pot of money we now know as The Deficit.

No institutional memory, that's the problem...

Finally, I had a vague memory about the UK motorway programme, which came to fruition in the 1970s, and where it originally came from. The answer was a trip which the County Surveyors Society - the driving force behind Britain's road-building programme - made to see the amazing autobahns of Nazi Germany in 1937. This is what one member of the delegation (R. A. Kidd) wrote some decades later:

"In all it was a wonderful experience, and one appreciated the German efficiency in the organisation of the whole trip. The imprint on our minds of a concept of a network of motor roads resulted in the County Surveyors' plan for motor roads in Britain, which unfortunately was pigeon-holed by the then Ministry of Transport for many years. In essence, however, it came to light in the Ministry's ultimate scheme, although the basic origin of this was probably never mentioned, or credit given to the Society." (quoted from A History of the County Surveyors' Society).

You bet it wasn't mentioned, and certainly not in the 1970s - only three decades since the Blitz - but, yes, the original inspiration came from Hitler's autobahns.

Published on June 29, 2013 02:30

June 28, 2013

Roadbuilding? In the 1970s, it was a disaster

"The valley is gone and now every fool in Buxton can be in Bakewell in half an hour and every fool in Bakewell in Buxton," said John Ruskin when the viaduct across Monsal Dale in Derbyshire was planned.

Now the viaduct is preserved and I walked over it myself only last month, so Ruskin perhaps misjudged the situation.

But I did think of his words again when I heard details of the infrastructure spending planned by the government yesterday. The investment in public transport and green energy is tremendously important, partly because it will create local livelihoods for people long after the bulldozers have gone.

But I did think of his words again when I heard details of the infrastructure spending planned by the government yesterday. The investment in public transport and green energy is tremendously important, partly because it will create local livelihoods for people long after the bulldozers have gone.

But you have to wonder about HS2, given that just the contingency costs are more than the entire national arts budget. And most of all, I have been wondering about the boast that the road-building programme is unprecedented since the 1970s.

For those of us who dimly remember the 1970s, the road programme was a disaster. It increased traffic exponentially (see my blog about transport theorist Martin Mogridge, who worked out that reducing congestion requires reducing roadspace for cars). It created congestion. In urban areas, it blighted and destroyed neighbourhoods. Reports after the nationwide riots in 1981 said that every area where there had been serious rioting had been blighted by plans for urban motorways.

And if they are just bypasses, or pothole filling - as Danny Alexander put it - then why on earth are they being announced from Westminster, and not devolved to local authorities to decide?

But the real question is the one that Ruskin implies: are there actually any economic benefits to roadbuilding?

Yes, they provide work in the building - but there might be more useful ways of spending the money. Yes, public transport infrastructure certainly helps regeneration because it allows people to live in areas they felt were too remote before. Yes, high speed railways take people out of planes, which has to be a good thing.

But is there any evidence at all - beyond the bogus cost benefit analyses that just add things up and never subtract - that more roads increase wealth.

Because, on the face of it, all they do is increase the wealth of big Just-In-Time systems. On the face of it, they open up new markets for the big supermarkets, at the expense of local business. Is there really any evidence that this is new money? Because, as I see it, most road-building simply re-distributes local business to big business. It is therefore the very opposite of wealth or growth. It is what Ruskin called illth.

Far from being proud of the road-building programme of the 1970s, nothing went as far as that did to undermining local autonomy and local knowhow. It played an important part in making some parts of the nation into helpless supplicants to Whitehall.

Pouring our scarce resources into road-building means betting the exchequer on the idea that we are wealthier when we are more frenetically driving everywhere - which encourages the amalgamation of business and therefore reduces employment. It encourages the big versus the small.

It is precisely the opposite direction to which we should be going, which is gearing up local entrepreneurs to meet local needs - rather than exposing them to takeover by the big delivery machines.

Or am I wrong? Send me the evidence (no fatuous cost benefit analyses though) and put me out of my misery.

Now the viaduct is preserved and I walked over it myself only last month, so Ruskin perhaps misjudged the situation.

But I did think of his words again when I heard details of the infrastructure spending planned by the government yesterday. The investment in public transport and green energy is tremendously important, partly because it will create local livelihoods for people long after the bulldozers have gone.

But I did think of his words again when I heard details of the infrastructure spending planned by the government yesterday. The investment in public transport and green energy is tremendously important, partly because it will create local livelihoods for people long after the bulldozers have gone. But you have to wonder about HS2, given that just the contingency costs are more than the entire national arts budget. And most of all, I have been wondering about the boast that the road-building programme is unprecedented since the 1970s.

For those of us who dimly remember the 1970s, the road programme was a disaster. It increased traffic exponentially (see my blog about transport theorist Martin Mogridge, who worked out that reducing congestion requires reducing roadspace for cars). It created congestion. In urban areas, it blighted and destroyed neighbourhoods. Reports after the nationwide riots in 1981 said that every area where there had been serious rioting had been blighted by plans for urban motorways.

And if they are just bypasses, or pothole filling - as Danny Alexander put it - then why on earth are they being announced from Westminster, and not devolved to local authorities to decide?

But the real question is the one that Ruskin implies: are there actually any economic benefits to roadbuilding?

Yes, they provide work in the building - but there might be more useful ways of spending the money. Yes, public transport infrastructure certainly helps regeneration because it allows people to live in areas they felt were too remote before. Yes, high speed railways take people out of planes, which has to be a good thing.

But is there any evidence at all - beyond the bogus cost benefit analyses that just add things up and never subtract - that more roads increase wealth.

Because, on the face of it, all they do is increase the wealth of big Just-In-Time systems. On the face of it, they open up new markets for the big supermarkets, at the expense of local business. Is there really any evidence that this is new money? Because, as I see it, most road-building simply re-distributes local business to big business. It is therefore the very opposite of wealth or growth. It is what Ruskin called illth.

Far from being proud of the road-building programme of the 1970s, nothing went as far as that did to undermining local autonomy and local knowhow. It played an important part in making some parts of the nation into helpless supplicants to Whitehall.

Pouring our scarce resources into road-building means betting the exchequer on the idea that we are wealthier when we are more frenetically driving everywhere - which encourages the amalgamation of business and therefore reduces employment. It encourages the big versus the small.

It is precisely the opposite direction to which we should be going, which is gearing up local entrepreneurs to meet local needs - rather than exposing them to takeover by the big delivery machines.

Or am I wrong? Send me the evidence (no fatuous cost benefit analyses though) and put me out of my misery.

Published on June 28, 2013 02:51

June 27, 2013

The way forward for local, asset-based recovery

Danny Alexander announced today the coalition’s plans for job-creating investment, in energy, road and rail infrastructure.

Some of the priorities seem a little strange (I'll return to the question of whether road-building helps anybody except the road-builders). But it just so happened that, this morning, I was also talking about jobs – at the annual conference of the Centre for Local Economic Strategies in Manchester.

Richard Kemp was there promising he would push for a Bank of Liverpool. And I talked about 'asset-based' economics, where economies re-grow using their own resources. Because, important as conventional job creation investment is, successive governments have forgotten the lost art of growing city economies from the bottom up. This is what I said:

Come back with me for a moment in my time machine to Birmingham in the 1870s.

Come back with me for a moment in my time machine to Birmingham in the 1870s.

An experiment was happening there in urban economics that is a bit like the opportunity that lies before us.

Here we are. Reading Far from the Madding Crowd.

Agonising about the farm workers strike.

And talking about the screw manufacturer Joseph Chamberlain.

A populist politician with a monocle and an orchid in his buttonhole.

At the end of 1873, he seized control of a city that was a byword for poverty and filth.

Yes it was the first city of the Industrial Revolution, but it was desperate too.

Overcrowded slums. Poisoned rivers. Occasional water supplies.

Chamberlain and his Liberal colleagues took control from a group of independent councillors who met regularly in a pub called the Woodman.

They had prided themselves on their ability to avoid spending any money at all. They called themselves the ‘Economists’.

And Chamberlain revived Birmingham. He paved it. Lit its streets. Infused it with enormous pride. Built parks and galleries and concert halls.

But the key point was that he did it using the assets at his disposal. The foul water, the money flowing through, the local people. He didn’t wait for central government grants or plead for corporate sponsorship. He used the assets he had.

So there’s the shape of our opportunity too.

Because there’s a kind of learned helplessness about British cities now.

They have learned from the Treasury to stay clear of economics.

They have learned to beg for handouts or inward investment.

Neither of which are going to resume any time soon.

So there’s an opportunity. It may be the only opportunity.

It’s to look afresh at what cities have at their disposal.

And use them to stitch together a plan for regeneration that can happen despite the international gloom.

Using the people they have. Replacing their imports. Maximising local money flows.

It is absolutely urgent that they learn to do this, but there isn’t much to go on.

There are examples of what can be done all over the world. Wadebridge or Bath for energy. Ludlow or Bridport for food. Cleveland, Ohio for local procurement.

But not a lot about how they can all be brought together.

So here’s my list of three things that need to happen first:

First, we need to formulate what we mean as one proposition.

Not as a list of good ideas, but as one asset-based idea.

We know what we’re talking about. I recently had a strange experience in the lobby of the Treasury with eight of us from the local economics ‘sector’, if I can call it that.

We were meeting for the first time and realised immediately we were taking about the same thing.

We have to set it down, around these kind of propositions: Local institutions, assets, money flows, a sense of place.

There is money around, but not nearly enough institutions to invest locally and those which do exist are often too risk averse for growing local markets.There are assets in communities – knowledge, skills resources, land and buildings – that can be harnessed to support local economic development.There is money flowing through the local economy, but when there are few local enterprises and supply chains it tends to flow straight out again.A sense of place, where all the economic levers belong and link together, underpins this approach.Second task. More difficult this one.

We have to give it a name.

Something not so glitzy that it puts off the serious policy-makers. Not ‘people power economics’.

But not so complicated that it puts off everyone else. Not ‘endogenous local growth theory’

When it has a name, we can demand it. We can say: Boris why aren’t you doing it? We can hold mayors to account for their failure to do it. We can campaign for it at local level.

And then the third thing. Don’t undersell it.

We have to make no small plans here. No failure to grasp the significance of what we’re doing.

We need to explain that this asset-based approach to local economics (ooh I named it!) isn’t just a nice thing you might add on to keep the proletariat happy.

It’s the critical factor that can make a difference between wealth and poverty.

And has always done so in the history of cities back through all time.

It is the way not an interesting new approach. It is the way forward.

It is the potential solution to inequality and dependence.

It may look small-scale, but small plus small plus small equals big.

We need to say that simultaneously to the right and left, and to American mayors as the same time as we say it to UK council leaders.

To working classes and middle classes – and I may say I feel particularly strongly about this one.

I’ve just written a book called Broke (shameless plug) and I can tell you this is as urgent for the middle classes as it is for the working classes.

The only people we don’t really need to worry about are the least friendly economists.

Hit them with a logical fork. Where this asset based approach is tried, it works. Economists will then either have to pretend it doesn’t work – and make themselves irrelevant - or incorporate it into their world view.

Either way, we win.

But there’s something else too. Cheap energy has encouraged cities to specialise, based on the economic doctrine of comparative advantage.

They have trucked in their fresh milk and food thanks to the invention of refridgeration (also 1873).

They have flown in their tomatoes and strawberries at Christmas time.

The main reason the shape of cities is going to have to change is the rising cost of energy.

We need to find decentralised sources of energy which no longer waste a third in transmission. And decentralised food production systems too.

The question is no longer whether aspects of this massive localisation is going to happen, but when it will happen.

That puts cities in the front line of change.

They urgently need the conceptual tools to help them make the shift.

To stop waiting hopelessly around for circumstances to improve or the Chinese to invest.

To make it happen.

And what I think we’re saying to them is this: where people live, then the resources, energy and imagination exist as well.

To create the local wealth they need.

Yes and well-being too, but we don’t need to dilute the message. It is wealth too.

Remember what Joseph Chamberlain said: “Be more expensive,” he urged other councillors.

I don’t think he meant spend more. He meant be more ambitious.

Be more imaginative. Be more generous. And I think we can now explain how it can be done.

Some of the priorities seem a little strange (I'll return to the question of whether road-building helps anybody except the road-builders). But it just so happened that, this morning, I was also talking about jobs – at the annual conference of the Centre for Local Economic Strategies in Manchester.

Richard Kemp was there promising he would push for a Bank of Liverpool. And I talked about 'asset-based' economics, where economies re-grow using their own resources. Because, important as conventional job creation investment is, successive governments have forgotten the lost art of growing city economies from the bottom up. This is what I said:

Come back with me for a moment in my time machine to Birmingham in the 1870s.

Come back with me for a moment in my time machine to Birmingham in the 1870s.An experiment was happening there in urban economics that is a bit like the opportunity that lies before us.

Here we are. Reading Far from the Madding Crowd.

Agonising about the farm workers strike.

And talking about the screw manufacturer Joseph Chamberlain.

A populist politician with a monocle and an orchid in his buttonhole.

At the end of 1873, he seized control of a city that was a byword for poverty and filth.

Yes it was the first city of the Industrial Revolution, but it was desperate too.

Overcrowded slums. Poisoned rivers. Occasional water supplies.

Chamberlain and his Liberal colleagues took control from a group of independent councillors who met regularly in a pub called the Woodman.

They had prided themselves on their ability to avoid spending any money at all. They called themselves the ‘Economists’.

And Chamberlain revived Birmingham. He paved it. Lit its streets. Infused it with enormous pride. Built parks and galleries and concert halls.

But the key point was that he did it using the assets at his disposal. The foul water, the money flowing through, the local people. He didn’t wait for central government grants or plead for corporate sponsorship. He used the assets he had.

So there’s the shape of our opportunity too.

Because there’s a kind of learned helplessness about British cities now.

They have learned from the Treasury to stay clear of economics.

They have learned to beg for handouts or inward investment.

Neither of which are going to resume any time soon.

So there’s an opportunity. It may be the only opportunity.

It’s to look afresh at what cities have at their disposal.

And use them to stitch together a plan for regeneration that can happen despite the international gloom.

Using the people they have. Replacing their imports. Maximising local money flows.

It is absolutely urgent that they learn to do this, but there isn’t much to go on.

There are examples of what can be done all over the world. Wadebridge or Bath for energy. Ludlow or Bridport for food. Cleveland, Ohio for local procurement.

But not a lot about how they can all be brought together.

So here’s my list of three things that need to happen first:

First, we need to formulate what we mean as one proposition.

Not as a list of good ideas, but as one asset-based idea.

We know what we’re talking about. I recently had a strange experience in the lobby of the Treasury with eight of us from the local economics ‘sector’, if I can call it that.

We were meeting for the first time and realised immediately we were taking about the same thing.

We have to set it down, around these kind of propositions: Local institutions, assets, money flows, a sense of place.

There is money around, but not nearly enough institutions to invest locally and those which do exist are often too risk averse for growing local markets.There are assets in communities – knowledge, skills resources, land and buildings – that can be harnessed to support local economic development.There is money flowing through the local economy, but when there are few local enterprises and supply chains it tends to flow straight out again.A sense of place, where all the economic levers belong and link together, underpins this approach.Second task. More difficult this one.

We have to give it a name.

Something not so glitzy that it puts off the serious policy-makers. Not ‘people power economics’.

But not so complicated that it puts off everyone else. Not ‘endogenous local growth theory’

When it has a name, we can demand it. We can say: Boris why aren’t you doing it? We can hold mayors to account for their failure to do it. We can campaign for it at local level.

And then the third thing. Don’t undersell it.

We have to make no small plans here. No failure to grasp the significance of what we’re doing.

We need to explain that this asset-based approach to local economics (ooh I named it!) isn’t just a nice thing you might add on to keep the proletariat happy.

It’s the critical factor that can make a difference between wealth and poverty.

And has always done so in the history of cities back through all time.

It is the way not an interesting new approach. It is the way forward.

It is the potential solution to inequality and dependence.

It may look small-scale, but small plus small plus small equals big.

We need to say that simultaneously to the right and left, and to American mayors as the same time as we say it to UK council leaders.

To working classes and middle classes – and I may say I feel particularly strongly about this one.

I’ve just written a book called Broke (shameless plug) and I can tell you this is as urgent for the middle classes as it is for the working classes.

The only people we don’t really need to worry about are the least friendly economists.

Hit them with a logical fork. Where this asset based approach is tried, it works. Economists will then either have to pretend it doesn’t work – and make themselves irrelevant - or incorporate it into their world view.

Either way, we win.

But there’s something else too. Cheap energy has encouraged cities to specialise, based on the economic doctrine of comparative advantage.

They have trucked in their fresh milk and food thanks to the invention of refridgeration (also 1873).

They have flown in their tomatoes and strawberries at Christmas time.

The main reason the shape of cities is going to have to change is the rising cost of energy.

We need to find decentralised sources of energy which no longer waste a third in transmission. And decentralised food production systems too.

The question is no longer whether aspects of this massive localisation is going to happen, but when it will happen.

That puts cities in the front line of change.

They urgently need the conceptual tools to help them make the shift.

To stop waiting hopelessly around for circumstances to improve or the Chinese to invest.

To make it happen.

And what I think we’re saying to them is this: where people live, then the resources, energy and imagination exist as well.

To create the local wealth they need.

Yes and well-being too, but we don’t need to dilute the message. It is wealth too.

Remember what Joseph Chamberlain said: “Be more expensive,” he urged other councillors.

I don’t think he meant spend more. He meant be more ambitious.

Be more imaginative. Be more generous. And I think we can now explain how it can be done.

Published on June 27, 2013 05:48

June 26, 2013

The great housing tyranny

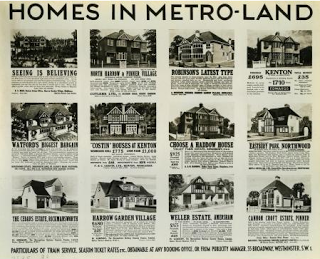

There is always a certain amount of snobbery, inverted and otherwise, about suburban semi-detached homes - especially those built between the wars, with their generous gardens, their little garden gates and garages and their twee stained glass front doors.

There is always a certain amount of snobbery, inverted and otherwise, about suburban semi-detached homes - especially those built between the wars, with their generous gardens, their little garden gates and garages and their twee stained glass front doors.They were designed without the aid of architects - their major sin as far as the architectural press is concerned - but they have been probably the most successful house design in our history. There are other people who don't believe anyone should have a garden. There are more perverse types who say, like Marie Antoinette, 'let them live in flats'.

Don't believe a word of it. There is something civilised and dignified about the semi and, yes - since you ask - I live in one myself.

I don’t know exactly what mine cost to buy originally in 1937, but it was somewhere around £700. In those days, the average mortgage cost ten per cent of your income and was paid off in fifteen years. The gardens were designed in the early years of Ideal Home magazine, to include space for hens. My own home is almost surrounded by a huge allotment space in northern Croydon.

As I say, it is all very civilised. But I do ask myself nearly every day how my children will afford anything of the kind - even how they will afford to rent anything of the kind.

This isn’t just a London phenomenon, or just confined to house prices – the same process have pushed average rents in London so far that you need a salary of £38,000 to rent a one-bedroom flat.

If house prices had increased at a civilised rate, my home would now be worth £40,400. In fact it is nearly worth £500,000, a ludicrous amount.

Which brings us to the latest cabinet 'rift'. Now, when the newspapers say there is a cabinet rift, it usually means a mild difference of emphasis. Perhaps the real worry is when they claim there isn't a rift. The latest rift described in these terms is between Nick Clegg and the Treasury and it is about housing. This is what he said in an interview with Nick Thornsby on Lib Dem Voice:

"But I totally agree with you that it would be real folly to simply go for easy wins on boosting supply of mortgages that doesn’t lead to supply of new housing. It’s probably one of my greatest frustrations that many of the levers that government can pull in housing can take a very long time to feed through. I’m like a stuck record round the cabinet table."

Clegg is quite right about this, and new housing is urgently needed. But there is a misunderstanding here, which is going to be tremendously important, and which seems to be shared by all politicians. It is the assumption that house price inflation is just a matter of demand and supply, whereas all the evidence is actually that it is about too much money in the system.

Of course, supply of housing isn't irrelevant. But solve that problem and the house prices will still rise - as they did under Blair and Brown because people were being lent four times joint salaries rather than three times one salary, and as they are now because of bankers bonuses and investors from the Far East.

Yes, we need more homes. But the reason so many sites with planning permission are not being built is because people can't afford to buy the homes, and they are not in places which can be advertised as good investments in Shanghai and Singapore.

The staggering 20 per cent rise in London rents over the last year is also because of rising property prices - this isn't about home ownership versus renting. It is about the best way of getting a roof over people's heads, where they need to live and with the maximum amount of control.

I believe that is best provided by mass home ownership. The idea of a "property-owning democracy" as the basis of human liberty was articulated by Conservatives but derives from renegade Liberals in the Distributist movement in the 1920s, and it is absolutely right. But it is completely incompatible with allowing our homes to become a tradeable commodity on the international markets.

It is also completely impossible if my small semi is worth half a million pounds, and - far from solving the problem - the Funding for Lending scheme will push up prices to even more tyrannical levels, even if huge numbers of homes are built.

I use the word 'tyrannical' deliberately. Because people are less free when they have to pay half their income in housing costs or more, less in control of their lives and much less able to follow the career and life path that thrills them most.

This is a far bigger and more potent issue than it seems, and I don't want my children eking out a living in indentured servitude to their landlord, in a job they loathe but need just to pay the rent, and unable to live near where they were born. It is the very opposite of civilisation.

Find out more in my book Broke.

Published on June 26, 2013 03:34

June 25, 2013

An apologia for austerity

I have a confession to make. I'm not quite as vitriolic in my opposition to austerity as I am supposed to be, though it is hard to be in favour of anything with a name like that.

In the Lib Dem policy committee, I spoke up for 'thrift' in the run-up to the 2010 election whenever I could (probably why I've been voted off). So let's remember, now that the new comprehensive spending package is about to be announced, that there remain reasons for tackling the deficit, even for a radical type like myself.

For me, back in 2010, these were the main reasons for backing thrift:

The international financial markets are indefensible, but - given that they exist - any country that runs too high a deficit (in their estimation) will be punished and find the decisions about what to cut taken out of their hands by international bankers. It is unconscionable that this could be allowed to happen to us.New Labour's public service reforms were not just disastrously expensive (£70 billion on IT alone) but led to even more expense by making the services less effective. The way to save public services, as I saw it, was to force local institutions to come up with innovative ways of making them effective again - and that meant spending cuts to break about the suffocating central controls.It so happened back then that the interests of economy and the interests of effective, sustainable public services happened to coincide. The unravelling of the CQC is some evidence of that half-articulated crisis in services that the last government presided over.

But then there is a problem, isn't there. Austerity has not actually reduced the deficit. Osborne has had to borrow about £275 billion more than he meant to since then, and the interest payments ratchet up.

This is partly because neither the NHS nor local government - with some notable exceptions - has really risen to the challenge of re-shaping services so that they are both more effective and less expensive. It is partly because the old system of regulation has been left virtually intact, and at great expense (CQC is only part of it). It is also, of course, because you can't cut your way to economic recovery.

There are also limits to austerity, and the agreement to cut an average of £30 million more from the annual budgets of every local authority may begin to unravel civilisation as we know it.

On the other hand, we teeter on the edge of a precipice. When interest rates start to rise, as they inevitably will, the deficit will become overwhelming. What then?

Here are three things it seems to me we will have to do pretty soon, and the sooner the better as far as I'm concerned:

1. Unravel the remains of Labour's centralised public services regime, of which CQC is only the tip of a vast and ineffective iceberg. If this was anything like its American equivalent, it involved between a fifth and a third of all public service staff to audit the others, at vast expense, corroding the ability of the frontline to innovate. Give some of the money to the CCGs to run local inspections and abolish the great auditing epidemic.

2. Merge services locally. It is inconceivable that we can still afford seven different state agencies to knock on your door when you apply for disability support. I've written about the future, effective shape of public services elsewhere in this blog.

3. Create the money interest-free to pay off most of the debt. It is insane that the money for the national debt should be created by bankers - at great expense to the public purse - and not created by our own central bank, and that between a fifth and a quarter of national income should be diverted to pay the interest.

The first two of these must be done overwhelmingly to make services more effective, so that a minimum number of interventions is necessary - and the investment in troubled families presided over by Danny Alexander is evidence that this is beginning. If you do it to save money, it will only raise long-term costs, and unfortunately so much of the cuts have been decided on this basis so far.

The last one would be a controversial move, but we have kept the power to do this by staying out of the euro - and if it means averting national disaster, or the corrosion of our civilisation, then I know what I would choose.

This is what I would do if interest rates rose. I know what Osborne would choose. I suspect he would carry on cutting, past the point of no return. But what would Miliband and Balls do, now that they have accepted the spending review and rendered themselves virtually obsolete as an opposition?

Published on June 25, 2013 01:59

June 24, 2013

How the middle classes can fight back

Regular readers of this blog (if there are any) will be astonished that I haven't mentioned the middle classes, ooh , for weeks...

Let me put that right immediately. Because Mark Pack has pointed out the results of a new YouGov poll for Prospect about class in the UK and it confirms to some extent what I've been saying. Interestingly, 44 per cent of the poll identified themselves as middle class and 44 per cent said they were working class. A dead heat.

The rest didn't know, except for one per cent who said they were upper class - though whether this really was the One Per Cent or a few surviving aristocratic types, I don't know.

And sure enough, no less than 40 per cent said they believed it would be more difficult for the next generation to be middle class than their parents.

That is what I wrote in my book Broke: Who killed the middle classes? (read it to find out whodunnit).

I would take issue with the poll, at least, that only 23 per cent said this would be a bad thing. This seems to me to be naive and dishonest, and a clear example of the usual middle class disease - embarrassment about class. For reasons I've said elsewhere, it matters very much - and matters to everybody. Because if nobody can break out of the fetters of the proletariat, then we become a society with a tiny elite and a huge population, trapped in poverty and dependence, deeply unequal, unstable and dispiriting, with no leisure, culture or space.

I was thinking about this also as I was listening to the BBC's plans to expand their food awards into a fully fledged festival to back the growing movement for artisan and local food entrepreneurialism.

This seems to me to be an example of the middle classes clawing back some kind of role, as they will have to if they're going to survive.

But it isn't enough. It needs to go hand in hand with a new political strategy to support the new movement, if it is going to survive - to break up the privileged monopolies, to provide a lending infrastructure capable of supporting entrepreneurs, and above all to bring down the price of property.

It is absolutely staggering that parts of the media and political establishment are breathing sighs of relief that house prices and rents are accelerating ahead again, as if this was evidence of any kind of prosperity - except for the financial elite who profit from it.

It is equally staggering that the Treasury believes pushing up the price of homes, by helping people buy at inflated prices, helps anyone or rebalances the economy one jot.

So don't believe the middle classes are as relaxed about their own demise as the YouGov poll implies. But they haven't yet articulated what they need to survive - I think it's time they did.

Let me put that right immediately. Because Mark Pack has pointed out the results of a new YouGov poll for Prospect about class in the UK and it confirms to some extent what I've been saying. Interestingly, 44 per cent of the poll identified themselves as middle class and 44 per cent said they were working class. A dead heat.

The rest didn't know, except for one per cent who said they were upper class - though whether this really was the One Per Cent or a few surviving aristocratic types, I don't know.

And sure enough, no less than 40 per cent said they believed it would be more difficult for the next generation to be middle class than their parents.

That is what I wrote in my book Broke: Who killed the middle classes? (read it to find out whodunnit).

I would take issue with the poll, at least, that only 23 per cent said this would be a bad thing. This seems to me to be naive and dishonest, and a clear example of the usual middle class disease - embarrassment about class. For reasons I've said elsewhere, it matters very much - and matters to everybody. Because if nobody can break out of the fetters of the proletariat, then we become a society with a tiny elite and a huge population, trapped in poverty and dependence, deeply unequal, unstable and dispiriting, with no leisure, culture or space.

I was thinking about this also as I was listening to the BBC's plans to expand their food awards into a fully fledged festival to back the growing movement for artisan and local food entrepreneurialism.

This seems to me to be an example of the middle classes clawing back some kind of role, as they will have to if they're going to survive.

But it isn't enough. It needs to go hand in hand with a new political strategy to support the new movement, if it is going to survive - to break up the privileged monopolies, to provide a lending infrastructure capable of supporting entrepreneurs, and above all to bring down the price of property.

It is absolutely staggering that parts of the media and political establishment are breathing sighs of relief that house prices and rents are accelerating ahead again, as if this was evidence of any kind of prosperity - except for the financial elite who profit from it.

It is equally staggering that the Treasury believes pushing up the price of homes, by helping people buy at inflated prices, helps anyone or rebalances the economy one jot.

So don't believe the middle classes are as relaxed about their own demise as the YouGov poll implies. But they haven't yet articulated what they need to survive - I think it's time they did.

Published on June 24, 2013 02:38

June 23, 2013

Something is shifting in attitudes to Clegg

It's a strange thing, but something about Liberator magazine seems to be shifting in the zeitgeist (is that an expression?).

Liberator has become something of an institution. I like to think it was started and run by people a little older than I am, but I fear it is actually my generation.

Now, decades later, there is a sort of exhausted pessimism about it - but you have to admire its staying power when everything else has gone online. It is still anti-centre ground strategies, still holding firm to the way that 'radical Liberalism' used to be interpreted circa 1982 - which is the year I went to my first Liberal conference (Bournemouth it was).

It hardly needs saying that Liberator has been predictably sceptical about the coalition, and about centrism generally. Much more sceptical than I am. And predictably critical of Lib Dem leaders, and especially perhaps of Nick Clegg.

But I found a strange change of tone as I leafed through the latest edition. It is no less irritable, no less pessimistic, but the emphasis is changing about the leader.

"Nick Clegg has proved he can be a Liberal, loud and proud..." says the commentary.

Even Michael Meadowcroft declares himself "more of a Nick supporter".

This isn't quite the moment to talk about the idea of the 'centre ground', because I tend towards Liberator's position on that. We don't want Liberalism to look like a mere compromise between two realities.

I also agree with Jonathan Calder that the way the media is briefed to regard party activists as fodder to be told off by leaders is pretty exhausting, and extremely misleading. As if the Lib Dems who played a leading role in being the second party of local government somehow preferred protest to power.

But it also seems to me that this awakening of sympathy for the leader might be significant.

It coincides with a series of conversations I have had with people, from across the political spectrum, who happen to express admiration for what Clegg has achieved - and how he has survived everything that has been flung at him.

I have a feeling that we will see more of this, and that it may form the basis for the way history categorises the years we are living through. That the Lib Dem leader has played an extremely tough hand with great skill, concentrating on the very limited number of things that can be achieved, and holding the Liberal line in highly challenging times.

Of course he hasn't called it right every time - that would have been superhuman - and I am only too aware having just conducted a government review, just how difficult it is to change anything, even when you are the government. But my admiration of how he has conducted himself, and his everlasting stocks of dignity and good humour, grows all the time.

And I don't think I'm the only one who notices it.

Quite apart from anything else, it appears he has saved the country from abolishing the BBC, bringing back hanging and from 'Margaret Thatcher Day'. A blessed relief.

Liberator has become something of an institution. I like to think it was started and run by people a little older than I am, but I fear it is actually my generation.

Now, decades later, there is a sort of exhausted pessimism about it - but you have to admire its staying power when everything else has gone online. It is still anti-centre ground strategies, still holding firm to the way that 'radical Liberalism' used to be interpreted circa 1982 - which is the year I went to my first Liberal conference (Bournemouth it was).

It hardly needs saying that Liberator has been predictably sceptical about the coalition, and about centrism generally. Much more sceptical than I am. And predictably critical of Lib Dem leaders, and especially perhaps of Nick Clegg.

But I found a strange change of tone as I leafed through the latest edition. It is no less irritable, no less pessimistic, but the emphasis is changing about the leader.

"Nick Clegg has proved he can be a Liberal, loud and proud..." says the commentary.

Even Michael Meadowcroft declares himself "more of a Nick supporter".

This isn't quite the moment to talk about the idea of the 'centre ground', because I tend towards Liberator's position on that. We don't want Liberalism to look like a mere compromise between two realities.

I also agree with Jonathan Calder that the way the media is briefed to regard party activists as fodder to be told off by leaders is pretty exhausting, and extremely misleading. As if the Lib Dems who played a leading role in being the second party of local government somehow preferred protest to power.

But it also seems to me that this awakening of sympathy for the leader might be significant.

It coincides with a series of conversations I have had with people, from across the political spectrum, who happen to express admiration for what Clegg has achieved - and how he has survived everything that has been flung at him.

I have a feeling that we will see more of this, and that it may form the basis for the way history categorises the years we are living through. That the Lib Dem leader has played an extremely tough hand with great skill, concentrating on the very limited number of things that can be achieved, and holding the Liberal line in highly challenging times.

Of course he hasn't called it right every time - that would have been superhuman - and I am only too aware having just conducted a government review, just how difficult it is to change anything, even when you are the government. But my admiration of how he has conducted himself, and his everlasting stocks of dignity and good humour, grows all the time.

And I don't think I'm the only one who notices it.

Quite apart from anything else, it appears he has saved the country from abolishing the BBC, bringing back hanging and from 'Margaret Thatcher Day'. A blessed relief.

Published on June 23, 2013 01:51

June 22, 2013

Why is everyone so angry these days?

The extraordinary scenes in cities across Brazil, where a million people came out on the streets in the last few days in anti-government protests, make me wonder whether something global isn't going on.

The extraordinary scenes in cities across Brazil, where a million people came out on the streets in the last few days in anti-government protests, make me wonder whether something global isn't going on.The disturbances in Ankara over the proposed development of a park seemed like an extension of the Arab Spring, but Brazil isn't remotely in the Middle East.

What holds these protests in common is that it is sometimes a small trigger - rising bus fares in this case - that sets them off. But the anger seems genuine enough - or would we, if this was happening in UK cities, dismiss them as looters or 'anarchists'?

Perhaps the real question is the same one somebody asked me in Boots recently, after a bust-up with an enraged customer: why is everyone so angry these days?

One answer seems to me to stem from the work of the anthropologist Polly Wiessner, from the University of Utah, an expert on the !Kung bushmen in southern Africa. What she says about them that’s relevant here is the amazing networks of reciprocal obligation they have. Not just with each other – but with families hundreds of miles away.

She was in the Kalahari desert in 1974 when torrential rains destroyed the harvest, and watched while, one by one, the families made the trek to stay with their friends where there was enough food.

The links with these distant families might have been inherited for generations, but they were there in an emergency. New game sanctuaries and arbitrary lines on maps are corroding these – and the distant partners are dwindling for the bushmen, but some links carry on. Any extra food or resources they have is still given away to facilitate these long-distance ties of obligation.

It means in practice that people in the Kalahari talk about what they owe their friends – the distant ones and their neighbours – the whole time. Are they really in need of help? Did they help too much? And so on. It’s a tireless and exhausting subject of conversation.

But Polly Wiessner says it is what makes human beings unique: social relationships of reciprocity. It is wonderfully secure, but it’s also a bit of a burden - it means you’re always being asked for things. You are never really quite alone or private.

She goes back there nearly every year, and she always finds the same thing when she comes home to her university. At first, there’s a huge sense of relief to have escaped these intricate networks of obligation. Then, five days later, she suddenly feels a deep sense of loss and loneliness.

Over the years, she’s come to believe this is because these reciprocal ties of obligation are part of being human, and I think she's right.

We know people build relationships by giving and receiving from the age of eight months old. We know from brain scans that the pleasure area lights up when people co-operate. We are hard-wired for reciprocity.

I wrote more about this in my book The Human Element. But it means that, when organisations arrange themselves in opposite ways, they run into trouble. Charities or public services which just give and ask for nothing back. Services which pretend to support us but are actually all about meeting targets. Companies which pretend to do ‘deals’ which still abandon customers when they need help.

It explains a little the quite irrational rage we have against them. But when it comes to governments which are constantly betraying the rhetoric that elected them - or siding with the powerful against the powerless (because their wealth will 'trickle down') - the same thing happens.

I think this goes some way to explaining why we feel so cross so much of the time. We constantly feel that the institutions and companies around us are offering us reciprocal relationships which they constantly betray.

A government that offers support for people who work hard and then gives them 'digital by default'. Or leaves them hanging on the call centre line while the bill ticks up. Or organises them so that they can be more easily processed by computer. Or grubs up the only green space in the neighbourhood...

These are all relatively small things. But they matter: they are a source of endemic rage.

Published on June 22, 2013 09:00

June 21, 2013

GM and the right to save your own seeds

I published a short ebook last year as a radical history of the allotments movement, and quoted the following letter to Country Life written at the height of the first Dig for Victory campaign in September 1917:

I published a short ebook last year as a radical history of the allotments movement, and quoted the following letter to Country Life written at the height of the first Dig for Victory campaign in September 1917:“The assumption on which a national policy of agriculture is based seems to be that the food supply of the country depends chiefly on the large cultivators. One is not prepared to say that there is no truth in this. The five-hundred acre farm must yield a greater absolute percentage of the food supply than the little plots. Still, that is not all the truth... Some remarkable instances can be given to show how this works out practically. For example, a man who had cultivated forty rods of land, when he set about it was able to produce as much from twenty rods as he had done from forty rods.”

I remembered this yesterday as my Twitter feed came alive with rage about the GM non-debate. In fact, the peculiar corner of Twitter which steams its way into my mobile phone was alive all yesterday with complaints about the BBC's handling of the story about GM crops.

Environment minister Owen Paterson has ignored the coalition agreement to give his enthusiastic backing to them, and - although I didn't hear the Today interview - the BBC seems to have displayed its not terribly rare ignorance of the issues.

I am not enough of a scientist to know whether the safety issues are real. That isn't the point. The real question is the monopoly power that GM crops gives to a handful of global megacorps carving up the world's food production between them (see picture of Monsanto and Bayer above) - and the income they extract from it, and from the poorest subsistence farmers every time they plant seeds which they used to be allowed to save until the following year.

Lord Melchett put it best, I thought:

"GM... is the cuckoo in the nest. It drives out and destroys the systems that international scientists agree we need to feed the world. "We need farming that helps poorer African and Asian farmers produce food, not farming that helps Bayer, Syngenta and Monsanto produce profits,"

Here is the point I wanted to make. There is another argument about how to feed a growing world population more effectively. It is not to tax the poorest farmers in this way, and provide them with expensive biotech that may or may not increase yields, driving to consolidate farms and seek economies of scale.

The other approach, which has development experts on side, is to support small farmers - because, in the end, attention to detail by committed small farmers will produce food, in the right places, at the right prices.

This is, once again, small versus big. Economies of scale versus diseconomies of scale.

The discovery that small farmers out-produce big farmers was set out in the 1970s by Amartya Sen, but it actually isn't a very new idea - as the letter to Country Life shows. The great radical William Cobbett noticed it when he was defending Horton Heath in Dorset from enclosure, noting that poor people could make poor land productive:

“The cottagers produced from their little bits, in food, for themselves, and in things to be sold at market, more than any neighbouring farm of 200 acres.

He noted that ten farms of a hundred acres each could produce more than one farm of a thousand acres. But it was a varied and diverse productivity, compared to the handful of products grown by the big farms. And there lies the source of the muddle. Monsanto and those like them don't measure yield in the same way.

Nor are they actually breeding the best seeds for small farmers. They are breeding for transportability, suitability for industrial production, while the small farmers - those who still hang onto the right to save their own seeds - breed for diversity and resilience.

That's why I am not on Paterson's side. Feeding the world means putting the means of providing for themselves in the hands of as many of the poorest people as possible. Undermining these support systems will really mean people dying of hunger, not making them dependent on the tender mercies of the big GM food corporates.

That's why GM food is a Liberal issue. It isn't about feeding the poor. It's about monopoly and dependence.

Published on June 21, 2013 03:58

David Boyle's Blog

- David Boyle's profile

- 53 followers

David Boyle isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.