David Boyle's Blog, page 73

August 19, 2013

My one little niggle about Scottish independence

I am in Scotland, for the Edinburgh Book Festival, where I am speaking today (4pm if you can come!) and marvelling at the lengths the Scottish government are going to in order to get a yes vote to take Scotland independent next year. Not just the umpteenth centenary of the Battle of Bannockburn, but a whole year's celebration of Scottish culture and a special Scottish food year.

I am in Scotland, for the Edinburgh Book Festival, where I am speaking today (4pm if you can come!) and marvelling at the lengths the Scottish government are going to in order to get a yes vote to take Scotland independent next year. Not just the umpteenth centenary of the Battle of Bannockburn, but a whole year's celebration of Scottish culture and a special Scottish food year.I know this is terribly shocking of me, but I have no problem with Scottish independence. Not because I am a nationalist (nationalism is the precise opposite of Liberalism) but because I am certainly not a unionist.

I have been convinced over the last two decades, writing about localism, that Europe would be more free, more diverse, more contented, more innovative and wealthier if it was an alliance of at least 50 mini-states, More so than it is with the current trumpeting former colonisers.

I agree with Freddy Heineken (he called it Eurotopia), and Leopold Kohr (a man who once shared offices with Orwell, Hemingway and Malreux), that small nation states are more successful and more civilised than big ones.

That is where the European Union plays an absolutely crucial role, blurring the old nationalisms and providing an umbrella that can hold mini-states or collections of mini-states together.

They will be wealthier if they use, not just the euro, but also their own parallel mini-national currencies. The great Canadian maverick Jane Jacobs convinced me in Cities and the Wealth of Nations that currencies suit city-states better than great sprawling continents, because they can revalue their money relative to neighbours, to suit their particular needs:

"Singapore and Hong Kong, which are oddities today, have their own currencies and so they possess this built-in advantage. They have no need of tariffs or export subsidies. Their currencies serve those functions when needed, but only as long as needed. Detroit, on the other hand, has no such advantage. When its export work first began to decline it got no feedback, so Detroit merely declined, uncorrected.”

The great issues of localism are different these days. They are not about which functions suit which level of government best - they are about the correct balance between local executive action and supra-local unifying structures.

It isn't a question of whether we should break up RBS, or break up the UK, into constituent parts - it is how to network effectively to support the local parts. That isn't about control or national destiny; it is about effectiveness. It isn't about economies of scale any more, and if occasionally economies of scale make sense - well, they can network together like Visa to achieve them.

The German local banking system is networked together to share capital capital and other infrastructure. Scotland, England and Wales would not go their separate ways - how could they? They would network together some functions in a Council of the British Isles, so that they could be more independent.

The only thing that worries me about Scottish independence is when I look out of the window where I am staying in Edinburgh, and I am reminded of the staggering inhumanity of some Scottish architecture.

This apartment block is comfortable and sophisticated inside; outside it looks like a prison. So does the next street, so does the next. There are parts of Glasgow which include some of the most inhuman architecture I have ever seen anywhere in the world.

These monsters have been build during the union with England, so I don't suppose independence would make anything worse. But my Scottish genes demand I make some kind of complaint about the way the city government of Scotland has, largely thanks to Labour control, made a terrible hash of mass housing....

Published on August 19, 2013 00:59

August 17, 2013

Come to Edinburgh to talk about the middle classes

Every summer in August, London's literary types decamp in a big coach for a small square in Edinburgh New Town, for the Edinburgh Book Festival - and very good it is too. Good atmosphere, good company, blue skies, nice grass to sit on. Rather wonderful, in fact.

Every summer in August, London's literary types decamp in a big coach for a small square in Edinburgh New Town, for the Edinburgh Book Festival - and very good it is too. Good atmosphere, good company, blue skies, nice grass to sit on. Rather wonderful, in fact.I mention this because, as this blog is posted, I am speeding up to Edinburgh to joint them and to elucidate my book Broke: Who Killed the Middle Classes? , which remains the subject of some controversy.

I am very much looking forward to discussing the ideas in it with anyone who comes, at my event at the Book Festival at 4pm on 19 August. I am doing the event jointly with Richard Brooks, who has written a book called The Great Tax Robbery. So if you want to argue with me (or him), please come along.

There will the the added unknown to look forward to: how much defending the middle classes will go down with a Scottish audience. I am sure there will be civilised disagreement, but there is a part of me which worries that I may end up like Nigel Farage on his last visit to that city.

Do please come along and find out. I look forward to seeing you there.

Published on August 17, 2013 23:28

I have seen the future, and unfortunately it's Legoland

This week, two families were banned for life from Legoland Windsor for brawling with iron bars while they were queuing for the pirate ride. The news does rather put Legoland into perspective.

This week, two families were banned for life from Legoland Windsor for brawling with iron bars while they were queuing for the pirate ride. The news does rather put Legoland into perspective.It is one of those staggeringly expensive examples of an economy in microcosm that is dominated by monopolies and monopolistic concessions.

That is why it costs so much to get in, at least £140 for a family of four, booking far in advance. It is why it costs £2.90 per scoop of ice cream when you are there. It is why you have to pay £2 just to leave the car park, let alone get in.

It works on the same principle of similar resorts, Centerparcs for example, where you can buy whatever you like – at great expense – as long as it is from Tesco. They are kinds of prisons of pleasure. I'm not surprised it drives people to violence.

It is why the queues are so long for the rides as well, and – because the English don’t understand what semi-monopolies do, and English politicians turn a blind eye – they take it out on each other with iron bars when they have to queue in the heat.

Now, I have huge respect for Lego. It was started in 1932 by the Danish carpenter Ole Kirk Kristiansen , a dedicated pacifist.

The pacifist approach has now been 'finessed' by the new CEO from McKinsey, who turned round Lego’s fortunes with a series of film link-ups starting with Star Wars. But the basic flexibility of the game remains: my children could survive on Lego without any other toys at all.

But in fact Legoland Windsor is only licensed by Lego, which sold all their parks in 2005. It is actually run by Merlin Entertainments, a huge leisure behemoth based in Poole, which runs nearly 80 similarly expensive leisure ‘experiences’ on four continents – including most of their so-called rivals in the UK, Thorpe Park, Alton Towers, Madame Tussauds, Sealife centres, you name it.

My children have been pressurising me to go to Legoland. I have even been collecting the One Adult Goes Free tokens from the sides of Kellogg’s packets, but was unable to find out from their website how you can use these to book cheaply in advance.

There is an information line but it is a premium rate 0871 number, of course. There is another landline for customer service in the small print (01753 626182), but they don’t appear to answer their phone.

So I emailed the press office and, lo and behold, someone rang to give me the answer: you can’t book in advance using the Kellogg’s vouchers.

Still, the eye-watering expense of taking the family out for these is because Merlin Entertainments have too tight a hold on the entertainment resort market in this country. Break them up, I say.

If it was really made of Lego, I would break it up and make a new layout.

Published on August 17, 2013 01:40

August 16, 2013

How to grasp the NHS nettle

I have huge respect for the NHS blogger Roy Lilley and follow his blogs avidly, almost the only one I read every time it is published. He is extremely influential, by virtue of his enormous readership, and rightly so. In recent weeks, he has been asking rhetorically how the NHS needs to change.

This is an important question. There have been a string of high-level NHS reports saying non-specifically that the NHS has to change, and warning of imminent system breakdown, but there are precious few answers to the question: how? Few of them dare do more than tweak.

Even so, the recent CQC report into the hospital at Whipp's Cross is embarrassingly familiar and it does crystallise the problem - inadequate staffing, food put out of reach of elderly patients, not enough care or consideration. There is a problem out there, and although it isn't exactly clear why the NHS is facing a crisis now - its funding is ring-fenced after all - something is going on.

Partly the situation is politically confusing. There are elements where the last government is clearly to blame (the failures of the CQC and the PFI debt crisis) and there are elements where clearly it is the fault of the coalition (benefit changes, or fears of benefit changes, which emerge as extra demand on primary care and A&E). There is too much positioning, not enough prescription.

So I've been asking myself what I would do, and - since my family tells me that my blog is too filled with middle-aged complaints - I thought I would share the ten-point Boyle plan:

1. Consolidate the ruinous PFI loans: they are the looming public sector debt crisis, five years after the private sector debt crisis, and they need to be dealt with the same way - taken off the books of the trusts and put into a special financial vehicle designed to re-negotiate them and remove them. They may otherwise cost over £300bn, a huge drain on services.

2. Abolish the centralised inspection system: Roy Lilley is absolutely right that the CQC must go and its duties be handed to local Clinical Commissioning Groups. Monitor is still required: it needs to take charge of failing trusts.

3. Share the work with patients: the time has come for major investment in people-powered health and co-production, which Nesta believes will save at least £4.4bn and maybe considerably more. It is extraordinary that this is happening so little.

4. Take rights in new drugs: the government invests in health research but gets none of the financial benefits, while the drugs bill (now £11bn a year) spirals. Pricing according to the financial benefits of drugs, the current strategy, is not adequate (more on this another day).

5. Sack boards of failing trusts: there must be some sanction against the boards who allow their hospitals to end up inhumane places of care.

6. Hand back out-of-hours care to GP practices: easier said than done, I know, but the present system is a disgrace and a blot on the reputation of GPs.

7. Hand over patient records to patients: they should own their own data and give access to professionals that need it, rather than the present wasteful system of parallel agencies asking patients endlessly for permission to share (see PKB for example).

8. Do most follow-up appointments electronically: there is huge spare capacity in the system just because consultants have a rigid system that requires face-to-face follow-up appointments every six months, whether people need one or not.

9. Encourage hospitals to invest in primary care: they have the motivation to invest in prevention.

10.Investigate the perverse incentives: too many patients are being given the runaround because hospitals can charge more. All gaming behaviour that wastes resources for the system as a whole must be defined as 'anti-competitive'.

By which I mean that we will have an NHS which is not leaching money to PFI contracts, which is delivered partly by other patients and which is a great deal more flexible. I hope it will also fulfil Roy Lilley's claim this morning, that kindness is more important than technology, skills, drugs or investment.

And when you've done all that, I have a few more up my sleeve...

This is an important question. There have been a string of high-level NHS reports saying non-specifically that the NHS has to change, and warning of imminent system breakdown, but there are precious few answers to the question: how? Few of them dare do more than tweak.

Even so, the recent CQC report into the hospital at Whipp's Cross is embarrassingly familiar and it does crystallise the problem - inadequate staffing, food put out of reach of elderly patients, not enough care or consideration. There is a problem out there, and although it isn't exactly clear why the NHS is facing a crisis now - its funding is ring-fenced after all - something is going on.

Partly the situation is politically confusing. There are elements where the last government is clearly to blame (the failures of the CQC and the PFI debt crisis) and there are elements where clearly it is the fault of the coalition (benefit changes, or fears of benefit changes, which emerge as extra demand on primary care and A&E). There is too much positioning, not enough prescription.

So I've been asking myself what I would do, and - since my family tells me that my blog is too filled with middle-aged complaints - I thought I would share the ten-point Boyle plan:

1. Consolidate the ruinous PFI loans: they are the looming public sector debt crisis, five years after the private sector debt crisis, and they need to be dealt with the same way - taken off the books of the trusts and put into a special financial vehicle designed to re-negotiate them and remove them. They may otherwise cost over £300bn, a huge drain on services.

2. Abolish the centralised inspection system: Roy Lilley is absolutely right that the CQC must go and its duties be handed to local Clinical Commissioning Groups. Monitor is still required: it needs to take charge of failing trusts.

3. Share the work with patients: the time has come for major investment in people-powered health and co-production, which Nesta believes will save at least £4.4bn and maybe considerably more. It is extraordinary that this is happening so little.

4. Take rights in new drugs: the government invests in health research but gets none of the financial benefits, while the drugs bill (now £11bn a year) spirals. Pricing according to the financial benefits of drugs, the current strategy, is not adequate (more on this another day).

5. Sack boards of failing trusts: there must be some sanction against the boards who allow their hospitals to end up inhumane places of care.

6. Hand back out-of-hours care to GP practices: easier said than done, I know, but the present system is a disgrace and a blot on the reputation of GPs.

7. Hand over patient records to patients: they should own their own data and give access to professionals that need it, rather than the present wasteful system of parallel agencies asking patients endlessly for permission to share (see PKB for example).

8. Do most follow-up appointments electronically: there is huge spare capacity in the system just because consultants have a rigid system that requires face-to-face follow-up appointments every six months, whether people need one or not.

9. Encourage hospitals to invest in primary care: they have the motivation to invest in prevention.

10.Investigate the perverse incentives: too many patients are being given the runaround because hospitals can charge more. All gaming behaviour that wastes resources for the system as a whole must be defined as 'anti-competitive'.

By which I mean that we will have an NHS which is not leaching money to PFI contracts, which is delivered partly by other patients and which is a great deal more flexible. I hope it will also fulfil Roy Lilley's claim this morning, that kindness is more important than technology, skills, drugs or investment.

And when you've done all that, I have a few more up my sleeve...

Published on August 16, 2013 08:28

August 15, 2013

The perils of scientific morality and counting too much

I have been brought up for most of my conscious life with a vague knowledge of C. P. Snow's controversial 1959 lecture 'The Two Cultures'.

I have been brought up for most of my conscious life with a vague knowledge of C. P. Snow's controversial 1959 lecture 'The Two Cultures'.It was this which inspired the staggering rejoinder from the literary critic F. R Leavis, who attacked Snow bitterly without actually reading what he said. "To read it would be to condone it," he said.

Even so, I am probably more on Leavis' side than Snow's. Snow assumed that somehow the arts and the sciences were equal and opposite, when they are not. Important as science is, there is always a danger that morality, art, significance and the study of unmeasurable life, will collapse into science and become a miserable shadow of themselves.

That isn't to say that measurement plays no role in the liberal arts. Or to say that Snow was wrong that everyone needs some understanding of science. But to compare the two is a bit like comparing Shakespeare with a vacuum cleaner. You still need vacuum cleaners, of course, but still...

Now, thanks to the Canadian science writer Steven Pinker, the old debate is coming back to life again. His article in the American magazine New Republic defends science against the accusations of a reductionist 'scientism'.

The UK's most imaginative critic of scientism, Bryan Appleyard, has written a fascinating response - acknowledging that Pinker is at least right that critics are sometimes confusing the way some scientists behave with the ideals of the scientific method.

Quite right. Scientific propositions need to be falsifiable. They must remain tentative. Even so, Pinker manages to condemn "fate, providence, karma, spells, curses, augury, divine retribution, or answered prayers" - and he may be right, but it would be premature and unscientific to not rule out other creative forces yet to be understood.

I've read Pinker's article through a couple of times and there still seem to be two major weaknesses.

First, Pinker says this about morality:

"In combination with a few unexceptionable convictions— that all of us value our own welfare and that we are social beings who impinge on each other and can negotiate codes of conduct—the scientific facts militate toward a defensible morality, namely adhering to principles that maximize the flourishing of humans and other sentient beings. This humanism, which is inextricable from a scientific understanding of the world, is becoming the de facto morality of modern democracies, international organizations, and liberalizing religions, and its unfulfilled promises define the moral imperatives we face today."

You hear this from scientists often in the UK too, that scientific discoveries provide a 'de facto' morality. It can't be so, or - if it is - our morality is not founded on safe foundations.

What if our scientific knowledge changes? What if we find, as Robert Ardrey used to say, that we are actually descended from a race of killer apes? Does that change our basic morality? It is true that morality must be based on some scientific facts - but it will always go beyond it and rest, partly, on a human tradition which is beyond science (there are dangers there too, of course).

Second, Pinker talks about the insights of science for archaeology, psychology and literary criticism - all of which is true, but there is a danger here as well. There are forces in our world now which would like to subsume the liberal arts into something much narrower, digitisable and measurable - which will limit the breadth of the human mind to make it seem comprehensible (see Appleyard's important book The Brain is Wider Than the Sky).

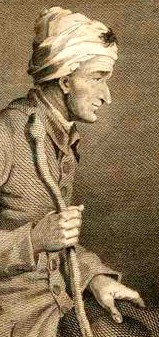

Although I'm sure Pinker would not fall for this himself, there are those out there in the grip of the strange obsession which gripped the eighteenth century Jedediah Buxton (see picture above). On his first trip to the theatre to see a performance of Richard III, he was asked whether he'd enjoyed it, and all he could say was that there were 5,202 steps during the dances and 12,445 words spoken by the actors. Nothing about what the words said, about the winter of our discontent made glorious summer; nothing about the evil hunchback king.

The story is funny now as then, but it is also faintly disturbing. Buxton is in some ways a fearsome symbol of the modern age, in which we count everything but see the significance of nothing.

More about Buxton in my book The Tyranny of Numbers . But why is the critique of this kind of scientism alive and well in the USA (see this for example) and yet relies on Bryan Appleyard and hardly anyone else over here? Or am I wrong?

Published on August 15, 2013 01:20

August 14, 2013

Coming soon: the fragmentation of conservatism

"Every boy and every gal,

That's born into the world alive,

Is either a little Liberal

Or else a little Conserva-tive."

So said W. S. Gilbert, but even when he was writing (Iolanthe, 1882), something was going on to confuse matters. The split in the Liberal Party over Ireland was made permanent by the rise of socialism - fear of socialism kept important strands of Liberalism muddled into the the conservatives well into the 20th century. They still are.

As a result, there are now two kinds of Conservatives (I am rather simplifying here, so please bear with me):

Those who believe that, if the rich and powerful are allowed to exercise their wealth and power, there will be advantages for everyone (the traditional conservative view, and by the way also Tony Blair's basic stance).Those who are motivated by independence, and a revulsion for those who would mess around with them (which includes an old-fashioned Liberal support for 'free trade').The problem is that, although the former are undoubtedly conservatives, the latter would have been recognisable as Liberals a century ago, and sometimes more recently too. They do not actually sit together very easily.

Free trade as currently interpreted confuses matters. The former support the right of the powerful to exercise their power. The latter support the right of small business to disrupt the powerful. These are not the same.

There are signs that this Auld Alliance is beginning to unravel, on both sides of the Atlantic. A fascinating article in the Guardian yesterday (thank you, Jody!) describes the divisions emerging over solar power in the Tea Party movement, in the Australian right and in parts of Europe too.

On the one hand, the Tea Party is funded by entrenched oil interests which pour scorn on solar power, along with all renewables. In some parts of the world, they are lobbying to tax it (in Spain, for example), just as - in Latin America - corporate interests have made collecting rainwater illegal, in case it reduces dependence on the water utilities.

On the other hand, there are those in all these places who are coming to see small-scale renewables as a guarantee of independence from state and corporate monopolies, and are reacting with fury to proposals to restrict or tax their right to adopt it.

In Western Australia, the utilities are horrified to find that demand for their energy is dropping fast. In Georgia, rebel Tea Party members have forced the monopoly utility to open up to more solar power, to the rage of their national organisers.

This is important. The fear of socialism is no longer enough to keep the Auld Conservative Alliance together. Nor is it enough, it seems to me, to allow those institutions which straddle the divide - the NFU and CBI, in this country - to survive either without choosing sides.

Are they backing the right of the big corporates or the big farmers to exercise unfettered semi-monopoly power (conservatism), or are they backing the right of disruptive small-scale enterprise to provide people with a measure of independence (liberalism)? Whose side are they on?

None of this would matter if this wasn't the key political faultline of the next decade - but it is. It spells real problems for conservative parties - who are also struggling with divisions between social conservatives and social liberals inside their ranks.

The real division of the next decade is the one which Liberalism was designed to fight - it is small versus big, independence versus dependence, people-power versus unfettered corporate power.

And I know which side I'm on. So before Liberal Democrats cast themselves completely adrift from the coalition, don't let's assume that they can't take a hefty chunk of the Conservative Party with them.

Published on August 14, 2013 01:29

August 13, 2013

Satisfying needs is not enough - this is why

There was a time when most neighbourhoods, and the poorer ones especially, were often alive with choirs, reading clubs, friendly societies, pigeon breeder clubs and all the rest. Not all of them, it is true, but many of them.

I remember reading Richard Booth's autobiography, describing how he built the first bookshops in Hay-on-Wye buying up the libraries from the working men's clubs.

But something else happened too. These poorer communities managed to get purpose-built community centres, and attracted grants for permanent professional staff to manage them.

The old charities which used to be run by small groups of friends in churches or working men’s clubs either died out or were pushed aside by the new lottery funded generation. Now the community centres in the Welsh Valleys, for example, usually have full-time managers and staff.

The peculiar thing is that they are often almost empty. What was once a network of voluntary projects and chapels gave way to a series of professional agencies, with paid staff, delivering services to passive consumers. Where did all that energy go?

In some ways, this is just an aspect of what the American sociologist Robert Putnam called ‘Bowling Alone’, a terrifying description of the erosion of neighbourhoods – watching the gentlemen of New London, Connecticut reduced to sitting alone in the local bowling alley, staring sadly upwards at the television.

Behind all this is the strange untold story of community development, especially when lottery funding is involved. When local agencies or charities discover a local need, they apply for grants to tackle it, most of which goes on their salaries.

Then the mystery: as people discover the service, the need seems to grow. Agencies have to ration support. Then the grant runs out and everything has to be applied for again to keep people in jobs, but dressed up as something wholly new and innovative.

The handful of local people who had been genuinely involved get dispirited, and the agency starts looking around for another need that could be packaged as a grant application.

One academic has called it ‘farming the poor’. The civil rights lawyer Edgar Cahn came up against this problem quite by accident when he was defending his National Legal Services Programme, the service that helped organisations to sue the government to enforce their rights.

He had urged the programme over the years to ask the people they were helping to give something back, but they never quite got round to doing so. Then suddenly, in 1994, there was a Republican landslide, determined to reduce the federal budget deficit, and a young maverick called Newt Gingrich was in the House of Representatives, looking for ways of saving money.

The Republicans had never much liked the Legal Services Programme anyway, so the scene was set for the inevitable congressional hearings before it was shut down.

The programme was duly cut by a third and hamstrung in other ways. The hearings were held in Congress. But out of the three million people a year which the programme had helped for 33 years – that’s about 100 million households – not one client turned up at the hearings to defend it.

A year or so later, Cahn’s own law school was also under threat. This was the successor to Antioch, the District of Columbia School of Law, which was modelled on a teaching hospital. Students go out into the community and give legal help, but they don’t just give it. They ask for something back through one of the time banks in a Baptist church or in local housing complexes.

It was a difficult campaign to win, given that Washington already had six law schools and a massive budget deficit. Even the Washington Post was calling for it to be closed. But hearings organised by the District of Columbia Council didn’t go the same way as the ones in Congress.

Those who had been helped, and paid back, came out in droves to support the law school and it stayed open. Giving something back for the help they had received had made people defend the law school. Perhaps because it was more equal. It wasn’t charity any more. Cahn describes this as the power of ‘reciprocity’. More about this in my book The Human Element.

I tell this story because I got into trouble two days ago by criticising the Labour tradition of 'meeting needs'. I did so, not because I don't believe governments should meet needs, but because - if meeting needs becomes their sole purpose - then there are peculiar side-effects.

1. Politicians forget to ask why those needs arose in the first place, and never get round to taking action to prevent them.

2. The needs become the currency of public sector transaction: the only way of accessing support is to maximise your needs - of course they tend to grow.

3. The system turns its back on mutuality. It demands that people are passive and grateful. It disempowers.

"Charity wounds," said the great anthropologist Mary Douglas, and this is what she meant. It doesn't mean that needs should not be met, but it does imply that meeting them should be about building relationships. It means that people should ask each other for something back. It needs to be transactional.

This is the problem with the Labour tradition. It forgets that there is anything else beyond meeting needs. It sums up human beings as bundles of needs. It represents the apotheosis of need.

It is time we bundled up the whole Labour tradition and tried to move beyond it.

I remember reading Richard Booth's autobiography, describing how he built the first bookshops in Hay-on-Wye buying up the libraries from the working men's clubs.

But something else happened too. These poorer communities managed to get purpose-built community centres, and attracted grants for permanent professional staff to manage them.

The old charities which used to be run by small groups of friends in churches or working men’s clubs either died out or were pushed aside by the new lottery funded generation. Now the community centres in the Welsh Valleys, for example, usually have full-time managers and staff.

The peculiar thing is that they are often almost empty. What was once a network of voluntary projects and chapels gave way to a series of professional agencies, with paid staff, delivering services to passive consumers. Where did all that energy go?

In some ways, this is just an aspect of what the American sociologist Robert Putnam called ‘Bowling Alone’, a terrifying description of the erosion of neighbourhoods – watching the gentlemen of New London, Connecticut reduced to sitting alone in the local bowling alley, staring sadly upwards at the television.

Behind all this is the strange untold story of community development, especially when lottery funding is involved. When local agencies or charities discover a local need, they apply for grants to tackle it, most of which goes on their salaries.

Then the mystery: as people discover the service, the need seems to grow. Agencies have to ration support. Then the grant runs out and everything has to be applied for again to keep people in jobs, but dressed up as something wholly new and innovative.

The handful of local people who had been genuinely involved get dispirited, and the agency starts looking around for another need that could be packaged as a grant application.

One academic has called it ‘farming the poor’. The civil rights lawyer Edgar Cahn came up against this problem quite by accident when he was defending his National Legal Services Programme, the service that helped organisations to sue the government to enforce their rights.

He had urged the programme over the years to ask the people they were helping to give something back, but they never quite got round to doing so. Then suddenly, in 1994, there was a Republican landslide, determined to reduce the federal budget deficit, and a young maverick called Newt Gingrich was in the House of Representatives, looking for ways of saving money.

The Republicans had never much liked the Legal Services Programme anyway, so the scene was set for the inevitable congressional hearings before it was shut down.

The programme was duly cut by a third and hamstrung in other ways. The hearings were held in Congress. But out of the three million people a year which the programme had helped for 33 years – that’s about 100 million households – not one client turned up at the hearings to defend it.

A year or so later, Cahn’s own law school was also under threat. This was the successor to Antioch, the District of Columbia School of Law, which was modelled on a teaching hospital. Students go out into the community and give legal help, but they don’t just give it. They ask for something back through one of the time banks in a Baptist church or in local housing complexes.

It was a difficult campaign to win, given that Washington already had six law schools and a massive budget deficit. Even the Washington Post was calling for it to be closed. But hearings organised by the District of Columbia Council didn’t go the same way as the ones in Congress.

Those who had been helped, and paid back, came out in droves to support the law school and it stayed open. Giving something back for the help they had received had made people defend the law school. Perhaps because it was more equal. It wasn’t charity any more. Cahn describes this as the power of ‘reciprocity’. More about this in my book The Human Element.

I tell this story because I got into trouble two days ago by criticising the Labour tradition of 'meeting needs'. I did so, not because I don't believe governments should meet needs, but because - if meeting needs becomes their sole purpose - then there are peculiar side-effects.

1. Politicians forget to ask why those needs arose in the first place, and never get round to taking action to prevent them.

2. The needs become the currency of public sector transaction: the only way of accessing support is to maximise your needs - of course they tend to grow.

3. The system turns its back on mutuality. It demands that people are passive and grateful. It disempowers.

"Charity wounds," said the great anthropologist Mary Douglas, and this is what she meant. It doesn't mean that needs should not be met, but it does imply that meeting them should be about building relationships. It means that people should ask each other for something back. It needs to be transactional.

This is the problem with the Labour tradition. It forgets that there is anything else beyond meeting needs. It sums up human beings as bundles of needs. It represents the apotheosis of need.

It is time we bundled up the whole Labour tradition and tried to move beyond it.

Published on August 13, 2013 00:43

August 12, 2013

The middle class revolt against fundamentalism?

The BBC has just finished its series about the rise of the global middle class, but every few weeks there is more evidence of the middle class revolt emerging – first the Middle East, then Turkey, then Brazil, and then...

It may be premature to interpret this as one phenomenon, though that has hardly stopped some commentators – and it isn’t going to stop me today either.

What appears to be happening is that the global middle classes are emerging, only to discover how far the current economic system renders them powerless – and how far it threatens their continued existence. They lose public park in Ankara, or a bus fare in Rio, but these are just symbols of an underlying powerlessness.

What makes this a middle class revolt is not that they are defending middle class privileges.

It is that the global working classes no longer have the time, the space or the power to organise any kind of uprising. They are measured and controlled by tyrannical employers when they work, and – when they don’t – they are pre-occupied with the business of survival.

The prolific critic Slavoj Zizek has drawnparallels between the democratic reformers in the Middle East and the economic reformers in Latin America, arguing that they are both making a stand against fundamentalism that denies the importance of their humanity, and that they recognise the parallels.

It may be religious fundamentalism which clings to a bizarre belief in the literal truth of every sentence of holy scripture. Or it may be market fundamentalism, which clings to a bizarre belief in the objective reality of market values and the bottom line. It is at heart the same thing.

I find this idea compelling. It points to a similar crisis in economics and theology, and demands a humanistic response to both these kinds of spiritual impoverishment. Neither of them see the world as it really is. In theological terms, both put narrow simplifications above complex truth – which theologians used to call ‘idolatry’.

To make this comparison doesn’t mean rejecting genuine, complex religion, any more than it means rejecting markets. It means rejecting inhumane simplifications, single bottom lines, one-dimensional measures...

Perhaps it also sheds some light on one of the things that has been confusing me. Where is the spark of revolt against the market fundamentalism which is impoverishing the UK, where the middle classes are cowed, the working classes are powerless, and where political debate is so staggeringly narrow and constrained?

Because, watching the new pope, developing his pro-poor mission in Latin America, I have been wondering whether the spark of change is going to come from the Church.

I know this is anathema to the kind of positivist liberalism represented by Richard Dawkins and others. But it may be that only the Church is independent enough to see the problem clearly – and to recognise fundamentalism when they see it.

Then, there was the Archbishop of Canterbury weighing in to the payday loan companies, in a Church Militant tone of voice which we have not heard for a century or so.

He may have stepped back from this rhetoric in the days that followed. But it was so brave and clear, and tremendously hopeless, that I can’t get it out of my head.

Because we need that tone of voice, uncompromising, determined and human – threatening to drive the payday loan companies out of business. Aggressive on the side of what is right.

There is something going on in this space and I welcome it, and I am looking forward to the next intervention.

Incidentally, I am speaking at the Edinburgh Book Festival at 4pm on 19 August. If you want to debate these issues, or argue with me about my book Broke:Who killed the middle classes?, please come along...!

It may be premature to interpret this as one phenomenon, though that has hardly stopped some commentators – and it isn’t going to stop me today either.

What appears to be happening is that the global middle classes are emerging, only to discover how far the current economic system renders them powerless – and how far it threatens their continued existence. They lose public park in Ankara, or a bus fare in Rio, but these are just symbols of an underlying powerlessness.

What makes this a middle class revolt is not that they are defending middle class privileges.

It is that the global working classes no longer have the time, the space or the power to organise any kind of uprising. They are measured and controlled by tyrannical employers when they work, and – when they don’t – they are pre-occupied with the business of survival.

The prolific critic Slavoj Zizek has drawnparallels between the democratic reformers in the Middle East and the economic reformers in Latin America, arguing that they are both making a stand against fundamentalism that denies the importance of their humanity, and that they recognise the parallels.

It may be religious fundamentalism which clings to a bizarre belief in the literal truth of every sentence of holy scripture. Or it may be market fundamentalism, which clings to a bizarre belief in the objective reality of market values and the bottom line. It is at heart the same thing.

I find this idea compelling. It points to a similar crisis in economics and theology, and demands a humanistic response to both these kinds of spiritual impoverishment. Neither of them see the world as it really is. In theological terms, both put narrow simplifications above complex truth – which theologians used to call ‘idolatry’.

To make this comparison doesn’t mean rejecting genuine, complex religion, any more than it means rejecting markets. It means rejecting inhumane simplifications, single bottom lines, one-dimensional measures...

Perhaps it also sheds some light on one of the things that has been confusing me. Where is the spark of revolt against the market fundamentalism which is impoverishing the UK, where the middle classes are cowed, the working classes are powerless, and where political debate is so staggeringly narrow and constrained?

Because, watching the new pope, developing his pro-poor mission in Latin America, I have been wondering whether the spark of change is going to come from the Church.

I know this is anathema to the kind of positivist liberalism represented by Richard Dawkins and others. But it may be that only the Church is independent enough to see the problem clearly – and to recognise fundamentalism when they see it.

Then, there was the Archbishop of Canterbury weighing in to the payday loan companies, in a Church Militant tone of voice which we have not heard for a century or so.

He may have stepped back from this rhetoric in the days that followed. But it was so brave and clear, and tremendously hopeless, that I can’t get it out of my head.

Because we need that tone of voice, uncompromising, determined and human – threatening to drive the payday loan companies out of business. Aggressive on the side of what is right.

There is something going on in this space and I welcome it, and I am looking forward to the next intervention.

Incidentally, I am speaking at the Edinburgh Book Festival at 4pm on 19 August. If you want to debate these issues, or argue with me about my book Broke:Who killed the middle classes?, please come along...!

Published on August 12, 2013 07:24

August 11, 2013

Is there any reason for Labour's continued existence?

Perhaps it is even more significant that Labour backbencher George Mudie says he doesn't know what his party stands for, but Andy Burnham has caught the moment with his very public agonising - which amounts to much the same thing.

I have great respect for Andy Burnham. His summary of the fundamental problems of Westminster politics was spot on:

"I was schooled in this, kind of, 'how do we make a press release today that embarrasses the opposition?' That's the kind of politics that everyone was doing and the kind of culture developed where you're scrabbling over a bit of the centre ground with micro-policies that are designed to just create a little couple of days' headlines and create a feeling - but not change much else."

His solution is to merge health and social care under the auspices of the NHS. It is bold, and it plays to the Labour Party's old tradition - satisfying needs. He even sees the key problem of fragmentation in social care, which is has to be solved. He also recognises the importance of prevention, at least as far as good social care prevents people from turning up in primary care.

But there are three problems with this approach, brave as it is.

First, Burnham makes the same mistake as the coalition has made. He has not understood just how toxic the Blair-Brown legacy has been in public services, after a decade of target-driven centralisation, inflexibility and bone-headed IT investment along the lines laid down by McKinsey and others.

Health and social care do have to be merged, but they can't be merged using the existing system: it is built on the assembly line model and is not nearly effective enough at meeting people's real needs, not what the system thinks their needs are.

Second, Burnham includes no convincing analysis about why health and social care have been struggling, despite the ring-fencing of health services. Austerity might have been convincing, were it not for the fact that both systems have been increasing their costs much faster than the rate of inflation for years.

Is it an older population, more expensive drugs, or an increasingly alienated, isolated population, who receive treatment from the system as long as they remain passive? Any one of those requires some kind of analysis of how they can be tackled, or the costs of the new Greater NHS will rapidly overwhelm us - even after the austerity years.

It isn't enough to say that we just need to fund the current inflexible system better, with ever more central controls - in the Labour style - because people will not believe it, and they will be right not to. It was disastrous before. If they try and do it again, services will lose public trust.

But there is a third, more fundamental reason. Mudie was right: the Labour Party has not actually stood for anything much beyond positioning for some generations now, and their last period in power was presided over by a leadership which found it impossible to disagree with whoever was wealthiest or most powerful in any argument.

The party has long since ditched socialism, and according to the LSE, New Labour achieved no change in income inequality at all. In fact, they never tried.

The old Labour tradition (satisfying needs) is also problematic, given that - if satisfying needs is the heart of government, and the bureaucracy dedicated to that alone, then experience shows it tends to be deeply disempowering.

It is true, I am biassed against the Labour Party. I became interested in politics during the dull and reactionary Callaghan years, so I joined the Liberals. But Labour has still failed to develop an organising ideology. It means that when they take power, anything can happen.

I simply can't see the point of its continued existence.

I'm aware that I have said some related things about my own party sometimes. I'm also aware that my own party is in a coalition where their main power is simply to say 'no', on condition they don't do it very often. But I have been impressed by the discipline of the Lib Dem parliamentarians (far more so than their coalition partners).

I am kind of crossing my fingers that this may imply, despite all the difficulties and strains involved, that they have developed some underlying ideological coherence themselves.

I have great respect for Andy Burnham. His summary of the fundamental problems of Westminster politics was spot on:

"I was schooled in this, kind of, 'how do we make a press release today that embarrasses the opposition?' That's the kind of politics that everyone was doing and the kind of culture developed where you're scrabbling over a bit of the centre ground with micro-policies that are designed to just create a little couple of days' headlines and create a feeling - but not change much else."

His solution is to merge health and social care under the auspices of the NHS. It is bold, and it plays to the Labour Party's old tradition - satisfying needs. He even sees the key problem of fragmentation in social care, which is has to be solved. He also recognises the importance of prevention, at least as far as good social care prevents people from turning up in primary care.

But there are three problems with this approach, brave as it is.

First, Burnham makes the same mistake as the coalition has made. He has not understood just how toxic the Blair-Brown legacy has been in public services, after a decade of target-driven centralisation, inflexibility and bone-headed IT investment along the lines laid down by McKinsey and others.

Health and social care do have to be merged, but they can't be merged using the existing system: it is built on the assembly line model and is not nearly effective enough at meeting people's real needs, not what the system thinks their needs are.

Second, Burnham includes no convincing analysis about why health and social care have been struggling, despite the ring-fencing of health services. Austerity might have been convincing, were it not for the fact that both systems have been increasing their costs much faster than the rate of inflation for years.

Is it an older population, more expensive drugs, or an increasingly alienated, isolated population, who receive treatment from the system as long as they remain passive? Any one of those requires some kind of analysis of how they can be tackled, or the costs of the new Greater NHS will rapidly overwhelm us - even after the austerity years.

It isn't enough to say that we just need to fund the current inflexible system better, with ever more central controls - in the Labour style - because people will not believe it, and they will be right not to. It was disastrous before. If they try and do it again, services will lose public trust.

But there is a third, more fundamental reason. Mudie was right: the Labour Party has not actually stood for anything much beyond positioning for some generations now, and their last period in power was presided over by a leadership which found it impossible to disagree with whoever was wealthiest or most powerful in any argument.

The party has long since ditched socialism, and according to the LSE, New Labour achieved no change in income inequality at all. In fact, they never tried.

The old Labour tradition (satisfying needs) is also problematic, given that - if satisfying needs is the heart of government, and the bureaucracy dedicated to that alone, then experience shows it tends to be deeply disempowering.

It is true, I am biassed against the Labour Party. I became interested in politics during the dull and reactionary Callaghan years, so I joined the Liberals. But Labour has still failed to develop an organising ideology. It means that when they take power, anything can happen.

I simply can't see the point of its continued existence.

I'm aware that I have said some related things about my own party sometimes. I'm also aware that my own party is in a coalition where their main power is simply to say 'no', on condition they don't do it very often. But I have been impressed by the discipline of the Lib Dem parliamentarians (far more so than their coalition partners).

I am kind of crossing my fingers that this may imply, despite all the difficulties and strains involved, that they have developed some underlying ideological coherence themselves.

Published on August 11, 2013 04:32

August 10, 2013

Has change actually been slowing down?

Would the hapless Euro-MP Godfrey Bloom have offended with the same remark about bongo-bongo land a generation ago - in, say, 1967?

Would the hapless Euro-MP Godfrey Bloom have offended with the same remark about bongo-bongo land a generation ago - in, say, 1967?I have a feeling he would have done. Even the year before Enoch Powell's 'Rivers of Blood' speech, and the dockers marching in his support, most of us in the UK would have found it tasteless and boorish, if not offensive.

Though, it is a marginal call. Am I alone in remembering the lines of the original signature tune to the BBC’s Start the Week, sung by Lance Percival, and the line the follows “come to Bradford in the sun”? (I won't say what I think it was in case my memory is faulty).

The reason I have been wondering this is that I turned nine in 1967 and went for my birthday outing with a few friends to Chislehurst Caves(where are you now, Adam, James, Justin...?). I haven't been back since, until yesterday when, for my son's ninth birthday outing, I went again.

I wish I could say it hadn't changed at all. To be honest, I didn't remember a great deal (though it was extremely satisfying, after all this time, to wander around underground with an oil lamp).

What now feels like nostalgia was then more like uncategorisable impressions, so it is hard to make comparisons. But I have been wondering whether really so much has altered since then.

What has definitely shifted is social attitudes, to sexuality and race – or at least how one refers to it in public – and definitely in the role of women. IT has also changed, but I wonder really whether that is as big a transformation as we think it is, however wedded we are to the screen. We have also gained the concept of 'offensive' but at the cost of becoming more offended, more puritanical and so much narrower in public debate - but I was hardly taking part in pubic debate in those days, so I may be wrong.

I have a mobile phone, which I certainly never had in 1967, but I probably watch less television – my children certainly watch very much less than I did.

But apart from that, what has changed? In London, we have been working similar hours, going to the same sports venues, and catching the same bus routes with the same numbers, for well over a century. I have been travelling in jumbo jets for my entire life. The mini (see assembly line picture above from 1967) has been in production in Oxford since I was three - and it still is.

Doctor Who’s Tardis seems to be much the same as well.

Compared to the staggering technological changes of the first two decades of the last century, when cars, submarines, aeroplanes and cinema took giant leaps, to emerge fully formed around 1967, when the original pioneers were often still alive.

More about this in my submarine ebook Unheard, Unseen.

All of which is my way of saying this: don't believe it when people tell you that change is accelerating. In the UK, it has actually been slowing down.

And there is an old dinosaur like Godfrey Bloom mouthing off to prove it.

Published on August 10, 2013 02:11

David Boyle's Blog

- David Boyle's profile

- 53 followers

David Boyle isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.