David Boyle's Blog, page 69

September 28, 2013

My encounter with Owen Jones

I spent yesterday afternoon in the dark on stage a the Soho Theatre, doing a session on class and power with Chavs author Owen Jones, among others (Harriet Sergeant and Henry Hitchings, who chaired the whole affair brilliantly).

I spent yesterday afternoon in the dark on stage a the Soho Theatre, doing a session on class and power with Chavs author Owen Jones, among others (Harriet Sergeant and Henry Hitchings, who chaired the whole affair brilliantly).Ever since I horrified the readers of the Guardian and Telegraph simultaneously by writing about the middle classes in April, I have been urged to debate with Owen Jones – so I had been looking forward to it.

In the event, it is hard to disagree with him that the working classes have been demonised. Just as I think he kind of agreed with my take – that ordinary life is becoming unaffordable for the working and middle classes too (he stresses low pay as the reason, I would stress inflation driven by the financial sector).

In fact, the only time I found myself disagreeing with him was in answer to a question about the political changes that need to happen.

He cited hope and the need to fight for change, as people have always done. It is true that is how political change happens.

People will certainly have to fight, in the political sense, but economic change requires something else as well. The middle classes are great institution builders. The working classes are great movement builders (the co-op movement). Both are going to have to start the local institutions and the enterprises that we need to create the kind of economy that can provide for people.

Because in the end, if the economy doesn't provide for nearly everyone, then it will provide for nobody – because the money drains away, even faster than it does now, to the financial institutions and the ubermensch who run them.

We have hardly any local financial institutions in this country (I know we have some credit unions and a handful of CDFIs). The monopolies have been allowed to close most of our local food producers and hollow out their suppliers. The number of local newspapers or news outlets is a tenth of what is was a century ago - and the same goes for most economic institutions.

We need new ones, and new businesses, but we also need a political force prepared to defend them, against the powerful monopolies that are coming to dominate in every sector.

So it is more than just about keeping hope alive, or any of the other political rhetoric. Hope implies that, somehow, politicians are going to change their minds and sprinkle fairy dust and provide for us all.

Because, in the end , if anyone is going to provide, it is going to have to be us – but we will need a political force to defend us while we do it.

Published on September 28, 2013 03:57

September 27, 2013

When Tesco funds the high street research

Everyone knows that, if you're a blogger, journalist, lawyer, judge, politician, it isn't really enough to be completely open-minded - you really have to be seen to be.

Everyone knows that, if you're a blogger, journalist, lawyer, judge, politician, it isn't really enough to be completely open-minded - you really have to be seen to be.But for some reason, that same injunction doesn't seem to apply to some academics. When you are passing authoritative judgement on GM crops, for example, it helps your credibility if you are not being funded by Monsanto, as the John Innes Research Centre discovered.

Demos is a think-tank, rather than an academic research centre, but even so there have been a few eyebrows raised about their new research about bank lending to SMEs - which was funded by Barclays of all people.

Their research found that small businesses are not actually being turned down for loans by the big banks. You might say surprise, surprise, which would be cynical. But really it doesn't matter because, even if the research was completely independent (which I'm sure it was), the fact that Barclays funded it renders it worse than useless.

I am kind of staggered by the naivety about this. A politician wouldn't get away with it. Nor would a judge. So why do scientists think being funded by an organisation absolutely committed to one particular slant will enhance their reputation for high-mindedness?

I've been thinking a little about this because of the rising clamour of the debate about the future of high streets. There are retailers who believe that out-of-town or online retailing renders the old way of shopping completely archaic. There are customers who point out that the shops moved away first, forcing people to follow. There are a whole range of points of view - these are mine.

It might seem sensible to have an academic centre dedicated to understanding the future of retailing, and the ESRC funds a unit at Southampton University to do exactly this.

But here is the bizarre thing - which renders all their publicly funded seminars and reports useless - Tesco funds it as well, and for some reason even ESRC can't see that this renders their own funding suspect.

Tesco has a very particular take on the future of high streets. I find it extraordinary that nobody at Southampton or ESRC can see that this compromises their findings, however open-minded they are being (and I am sure they are), and consequently wastes public money.

We do need an academic centre for an impartial understanding of this emerging debate. Southampton can't be it while they are accepting money from such an involved source.

And here is Tesco's UK managing director Chris Bush explaining why they are abandoning plans to build in Sherborne (it wasn't the protests, apparently). He sounds open-minded about the questions that need answering:

"The real question driving this debate is this; how do you explain why some high streets untouched by supermarkets fail while others thrive with a mix of large and small retailers trading successfully side-by-side?"

Luckily, I'm in a position to answer his question. It is about whether the supermarket is genuinely an anchor store, or whether it actually seeks to compete with all the surrounding stores - and be a health centre and post office too. The monopolist approach is corrosive, the anchor store is - or can be - genuinely, well, anchoring.

For some reason, many planning authorities don't understand the difference, because they don't measure where the money will go - whether it will stay put circulating in the local economy or whether it will be hoovered up by the non-anchor supermarket and vacuumed away elsewhere.

These are important issues. There is a great deal of research that needs doing, especially if planning authorities are going to be properly informed. But I want my data produced and interpreted by someone who is not funded by one or other of the protagonists in the argument.

So, in the meantime, next time you are presented with data about the future of high streets or anything else, don't forget to ask where it came from.

Published on September 27, 2013 01:21

September 26, 2013

The centre ground doesn't mean doing nothing

I make no apology for returning, for the second day running, to Ed Miliband’s speech (well, OK, I am sorry actually). But the reaction to it by much of the media preyed on my mind all day yesterday.

The overwhelming reaction was that the speech marked the return of ‘Red Ed’. The headlines took the part of the power companies, threatening black-outs if their prices were cut. Matthew d’Ancona in the Evening Standard talked about him “abandoning the centre”.

Now, I’m as sceptical as the next man about the Labour leader. When he talked about bringing back socialism, I did blanche a little – but not because I think he will. But I can’t understand his commitment to a defunct political creed, which lived and died in the era of Fordist modernism.

The main criticism of Miliband seems to be that he has pushed his party to the Left because he has promised to act – on rising prices and market failure.

Yet that is what we used to expect party leaders to do. When they see the damage being done by the monopolies that have been allowed such power over our lives – largely by the Blair and Brown governments – then we expect politicians to tackle them.

And if tackling them means controlling the power of private monopolies – or, as they used to do in medieval times, setting a ‘just price’ – then that is what is has to be done, at least until you can break them up.

I say this partly because of my fears for my own party (the Lib Dems). There have always been marketing people around the leadership – and I have crashed four leaders so far as a party member – who try to reduce the message of Liberalism to mere strategy and positioning.

I don’t believe that the centre ground means never promising to change anything, as Matthew d’Ancona seemed to imply. I don’t believe for a moment that Nick Clegg thinks that either.

But clearly the Conservative press do. So maybe I need to revisit what I wrote yesterday about the Left endlessly defending the past rather than looking to the future.

I don’t believe Miliband represents the future, because he leads a party with no ideological bearings – which could turn out to be absolutely anything in power (and often does).

But I wonder if the complaints of the Right are, in a different way, a sign that they are also falling back on the great mistake of defending the solutions of the past rather than looking to the future.

Personally, I believe, that politicians who act on monopoly power – and find a means of doing so effectively – will inherit the earth, or the nation at least. We will see.

In the meantime, I'm debating some of these issues - around class and the future -at the Soho Literary Festival tomorrow afternoon. This includes my long-awaited encounter with Owen Jones of Chavs fame.

The organisers will no doubt want us to clash on class terms - in fact, it seems to me that the interests of the working classes and middle classes are now very similar. Either way, please come along and join in. It would be good to talk about it!

The overwhelming reaction was that the speech marked the return of ‘Red Ed’. The headlines took the part of the power companies, threatening black-outs if their prices were cut. Matthew d’Ancona in the Evening Standard talked about him “abandoning the centre”.

Now, I’m as sceptical as the next man about the Labour leader. When he talked about bringing back socialism, I did blanche a little – but not because I think he will. But I can’t understand his commitment to a defunct political creed, which lived and died in the era of Fordist modernism.

The main criticism of Miliband seems to be that he has pushed his party to the Left because he has promised to act – on rising prices and market failure.

Yet that is what we used to expect party leaders to do. When they see the damage being done by the monopolies that have been allowed such power over our lives – largely by the Blair and Brown governments – then we expect politicians to tackle them.

And if tackling them means controlling the power of private monopolies – or, as they used to do in medieval times, setting a ‘just price’ – then that is what is has to be done, at least until you can break them up.

I say this partly because of my fears for my own party (the Lib Dems). There have always been marketing people around the leadership – and I have crashed four leaders so far as a party member – who try to reduce the message of Liberalism to mere strategy and positioning.

I don’t believe that the centre ground means never promising to change anything, as Matthew d’Ancona seemed to imply. I don’t believe for a moment that Nick Clegg thinks that either.

But clearly the Conservative press do. So maybe I need to revisit what I wrote yesterday about the Left endlessly defending the past rather than looking to the future.

I don’t believe Miliband represents the future, because he leads a party with no ideological bearings – which could turn out to be absolutely anything in power (and often does).

But I wonder if the complaints of the Right are, in a different way, a sign that they are also falling back on the great mistake of defending the solutions of the past rather than looking to the future.

Personally, I believe, that politicians who act on monopoly power – and find a means of doing so effectively – will inherit the earth, or the nation at least. We will see.

In the meantime, I'm debating some of these issues - around class and the future -at the Soho Literary Festival tomorrow afternoon. This includes my long-awaited encounter with Owen Jones of Chavs fame.

The organisers will no doubt want us to clash on class terms - in fact, it seems to me that the interests of the working classes and middle classes are now very similar. Either way, please come along and join in. It would be good to talk about it!

Published on September 26, 2013 08:23

September 25, 2013

Why the left is so conservative on services

Ed Miliband's speech was rather good, I thought. The line about the rising tide only lifting yachts was a telling one - that is the weakness, not just of this recovery, but most UK recoveries in recent decades. That pinpoints precisely the main criticism that can be levelled at the man in the Treasury.

Ed Miliband's speech was rather good, I thought. The line about the rising tide only lifting yachts was a telling one - that is the weakness, not just of this recovery, but most UK recoveries in recent decades. That pinpoints precisely the main criticism that can be levelled at the man in the Treasury.The only thing that worries me about it is this. How will a party with Ed Balls as Shadow Chancellor generate the energy and will to shift the domination of the financial sector in Treasury thinking? How will they create the kind of revolution in enterprise (local economics, local banks) that the nation needs?

I don't see it, I must say.

But there is a more fundamental problem, not just with the Labour Party but with the thinking of the left in the UK, and a courageous article in the Guardian by Compass founder Neal Lawson put the point bravely and effectively:

"In truth, the forward march of Labour was halted long ago. New Labour applied go-faster stripes to a clapped-out vehicle but won elections only by telling the country it wasn't really the Labour party any more. The sugar rush simply accelerated the long-term decline."

It is particularly courageous to call your own party 'clapped out', but he is right.

Then a more relaxed and thoughtful article on Chris Dillow's Stumbling and Mumbling blog (thank you, Simon) which sets out the difference between the prevailing direction of travel by social democrats, in the Labour Party and abroad, and the direction that I see as a Liberal one. This is not so much that the Labour Party is clapped out, but that its reliance on central control is indefensible and sclerotic.

Let's face it, public services are the most immediate difficulty. For those of us who believe in public services that are effective, and under democratic control, then there are three looming problems:

1. Centralisation has 'hollowed out' services so that they are not nearly as effective as they need to be, and and the way services are being contracted out is making it worse (see my book The Human Element ).

2. This combination of over-complexity and sclerotic process is forcing up costs - just as budgets are under the most ferocious pressure - in a way that threatens the fundamental existence of many services (see the Graph of Doom).

3. Over-professionalisation and a patronising preference for users to be passive and easier to process is also undermining the sustainability of the services too. The huge resource represented by service users, their families and neighbours, is almost completely side-lined.

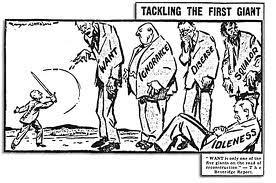

The combination of these crises, the interlinked problem of falling effectiveness and rising costs, threatens to unravel the welfare state set out by Beveridge. This isn't because he was wrong about slaying the Five Giants. It was because the way his settlement was put into effect by the Attlee government, and carried on since, has allowed the giants to come alive again every generation.

It isn't fair to blame Beveridge, because he predicted precisely this problem as early as 1948. So it is no good to wrap yourself in the banner of the Spirit of '45, or defend a system that has been hollowed out - as the left endlessly seems determined to do. Because that approach threatens to lose us everything.

This is absolutely not an argument to sell everything off or close everything down. Quite the reverse. It is an argument to wake up, understand the looming crisis, and re-invent the welfare state in a way that gives it some chance of surviving. And that means making it much more effective.

Why has the political left been on the retreat for a generation? Because they are constantly looking backwards - constantly defending the solutions of previous generations - when they ought to be seeking out new ways forward. So why don't they?

Published on September 25, 2013 05:37

September 24, 2013

Facing down the Co-op vulture funds

I have had a number of bank accounts with the Co-op for some years now. I’ve complained about them occasionally but, overall, they are light years ahead of the service you get from any one of the big banks, which are like a brontosaurus in comparison, unaware of activity from their own tail.

I have had a number of bank accounts with the Co-op for some years now. I’ve complained about them occasionally but, overall, they are light years ahead of the service you get from any one of the big banks, which are like a brontosaurus in comparison, unaware of activity from their own tail.I believe the difference is that the Co-op is part of a mutual. I am theoretically part owner, and that word 'theoretically' is part of the problem. It means far too little in practice.

It also failed to prevent the Co-op’s previous management from buying Britannia Building Society, along with all their voluminous debts. Consequently, they are now in some difficulties. I can’t help feeling that, if Co-op had felt a little more like a mutual, that fate might have been avoided, but we shall never know.

They are not in so much difficulty that they have been unable to agree terms with creditors, and he we come to the nitty-gritty.

Because two creditors, American hedge funds which bought into the debt in the summer – particularly notorious vulture funds – are objecting to the plan. They are trying to force the Co-op Bank to abandon its mutual status and be listed on the stock market, though Co-op group will remain the majority owner.

Many of this predatory group remain secret. A Co-op committee is now deliberating over whether they are right.

It may be a little portentous to put it like this, but: nobody has asked me.

I believe that, technically, I’m not a co-owner of the bank. But I am a customer and a stakeholder, and I did not become a customer to be taken for granted – or to be the customer of a bank listed with shares that can be bought by speculators, at the behest of hedge funds.

Apparently, they believe I will be there as a customer whatever they do. It seems to me that, by making clear this isn’t the case, we might prevent the hedge funds having it all their own way.

If they win this battle, I hereby promise to close my Co-op bank accounts and credit cards, and withdraw my savings from their savings funds, and do whatever I can to leave them with an empty shell.

Who is with me?

Published on September 24, 2013 02:41

September 23, 2013

How the bubble adds to the welfare bill

There I was minding my own business on Saturday afternoon when the PM programme phoned and asked me what I thought of Rachel Reeves' comments about an income of £60,000 not being rich.

There I was minding my own business on Saturday afternoon when the PM programme phoned and asked me what I thought of Rachel Reeves' comments about an income of £60,000 not being rich.Since I'm not plugged umbilically into Twitter, this was the first I had heard of Labour's swoop on the votes of Middle England. Next thing I knew, I was on the air. This is what I said (17 mins in).

The thing is that, depending rather where you live, a salary of £60,000 clearly isn't poor, but in many parts of the UK it isn't rich either. You still need to be relatively careful of money, if you want a roof over you head. That far, Rachel Reeves was right.

An income of £60,000 will get you a mortgage of around £180,000. The average London home is worth £500,000. Nor is it just about buying homes, because the rental value of homes goes up with the cost of property - as I explained in my book Broke: Who Killed the Middle Classes? - which was why they had invited me onto the programme.

Probably both the Labour Party and the BBC would prefer to leave the argument like this - how can someone earning £60,000 not call themselves rich when people can get by fine on £20,000? But I managed to get in a sentence or so to look at the reasons for it.

The truth is that the economy in London and the south east, and spreading rapidly out across the whole nation, is increasingly geared for the needs and pockets of the ultra-rich. They determine the price of homes. They determine public policy, long after the last believer in the 'trickle down' effect went toes-up. It is their needs and demands which the Treasury hears. Of course, in those circumstances, £60,000 isn't going to be enough for comfort.

The BBC may still want to foster the old arguments between the middle classes and the working classes - what, you don't feel well off on £60,000, shame on you! - when actually the interests of both now coincide.

It is to shift policy away from the monopolies and the financial sector, which are hoovering up the available wealth and remaking society as a flat proletariat, except for the 0.5 per cent of ubermensch at the top.

That is to look three decades ahead, to the next generation. But you can see the effects of the 30-year property bubble now - on welfare.

It is increasingly difficult to live an independent life on much less than, say, £18,000 in London, without support from the state. Property prices are rising again, cheer-led by the banks, and taxpayers are called upon to subsidise - not just the poor - but the increasing proportion of those who also can't afford to rent or buy.

So perhaps somebody could estimate the extra cost of housing benefit for every one per cent that property prices rise? Maybe they already have. If so, perhaps you could tell me. I think we should be told...

This is unfortunately just the beginning. Increasingly, ordinary life will become unaffordable, because that is what monopolies do, and that is what speculation does. It raises prices so that only a few can afford them. Then the state will find itself picking up the tab - funding for lending, funding for clothing, funding for computers, funding for children's eating, and then what...

Bizarrely, under a Conservative-led coalition, we are heading right back towards subsidised lives. First the poor, then the middle class, before they too are accused of scrounging for an unaffordable lifestyle. Can you imagine - why should we foot the bill to live in southern England? Surely it should be reserved for the rich?

Just because I don't want to live a subsidised life, that doesn't make me a Tory. Just because I want to lead an affordable life, that doesn't make me a socialist.

Published on September 23, 2013 02:30

September 22, 2013

Proof that change is actually slowing down

Last weekend, I found an old VHS of Steven Spielberg's film Back to the Future being sold off in the local library, along with the books, furniture, staff etc etc (thanks for nothing, Croydon Borough Council).

Last weekend, I found an old VHS of Steven Spielberg's film Back to the Future being sold off in the local library, along with the books, furniture, staff etc etc (thanks for nothing, Croydon Borough Council).I watched it through with my children, for whom it needed a lot of explaining.

But what I noticed was how strange it was looking back to 1985, when it was made, which is almost 30 years ago. This is ironic because it is all about going back in time 30 years from then, to 1955.

Regular readers of this blog (if there are any) will know that I am pretty sceptical about the idea, pedalled by American business and IT gurus, that change is accelerating.

Last time I wrote about this, my friend and inspiring blogger Mark Pack pointed me in the direction of a presentation he did which took apart those repeated claims that the take up of new technology is getting faster and faster. In fact, as he says, the take-up of radio in the 1930s was far faster than mobile phones today.

Well, for me Back to the Future revisited was conformation of this. The changes between 1955 and 1985 portrayed by the film were vast compared to those between 1985 and 2013 - from the bizarre cars and music through to the drugstores and dresses. And attitudes.

I have been wondering whether this is a delusion on my part because I can remember 1985 so well (Reagan, miner's strike, Iran-Contra, second Brixton Riot, remember?). I became editor of Town & Country Planning that year. It is certainly true that I had not used a computer, still less a mobile phone by then. IT has changed the way I work, but not vastly (though I certainly wouldn't be blogging).

Yet think of the other technological change over the last 30 years. Boeing 747s, still flying now. Volkswagen Golfs. Minis, for goodness sake. The clothes of 1985 would hardly look out of place now (heavens, I'm still wearing some of them).

My home might then have had carpets rather than a wooden floor. The offices we worked at in 1985 now lie empty and rotting. The value of our homes is corroding our lives - yes, there has been change. It occurred to me as I watched that one reason why pretend that change is accelerating is that we can't bear to look too closely at the reason it is slowing down: our political culture has lost the ability to imagine, and our administrative machinery is seizing up.

That is why, if I was to find myself in the movie Back to the Future and transported back three decades, I don't believe I would be disorientated in 1985. I might not even realise I had gone back in time - until, perhaps, I tried to remember how to use a phone box.

Published on September 22, 2013 01:36

September 21, 2013

UKIP and the meanings of words

I got a bit of a shock yesterday when I discovered I am six years older than Nigel Farage. This has not helped my self-esteem. I always thought of Farage as a creature from another age - maybe the 1930s, a sort of Terry-Thomas figure minus a handlebar moustache, a strangely elongated version of Bertie Wooster crossed with Basil Fawlty, practically ageless, but certainly generations older than me. A terrifying thought. that he is actually younger.

Still, you have to hand it to him. His political skills seem to have attracted no less than 150 journalists to the UKIP party conference this week. You have to hand it to him - he has an enviable ability to cut through political verbiage.

Anyone who doubts the Farage phenomenon should watch this clip of his speech to deeply uncomfortable looking German bankers in the European parliament, taking what seems to me to be a genuinely liberal line on the euro crisis. Politics does need people like that.

But what I wanted to say was this. I realise I must be the only person in the world, apart from Farage's colleague Godfrey Bloom, to feel sorry for Godfrey Bloom.

There he is making a deeply unwise comment about women not cleaning behind the fridge in a fringe meeting, and the next thing he knows, he is out on his ear.

And of all the things that Farage might need to apologise for - his brand of populism, his strange other-worldly policies on crime, military spending and immigration (they have to speak "fluent English" apparently) - what really upsets him is that Bloom has not realised that the word 'sluts' has changed in meaning since he was a boy, some centuries ago.

Personally I don't clean behind my fridge. I've never actually been there. It is uncharted territory. It may be a black hole sucking in dark matter for all I know. No doubt Godfrey Bloom would forgive this on the grounds that, as a man, I ought to be outside slaying things.

But what this strange incident tells me is that UKIP has started worrying about political correctness. It has started agonising about the impression it gives beyond its core support. It means they are just like other political parties - and that will blunt Farage's straight-talking. like nothing else

First, you complain about your colleagues understanding of four letter words. The next thing you know, you are dissembling like all your opponents. It is a slippery slope and it is fascinating to see that UKIP are now on it.

Published on September 21, 2013 01:38

September 20, 2013

Why property really isn't theft after all

For some peculiar reason, even in this age of the internet, I still get too many magazines. They pile up for months, and sometimes longer than months, waiting to be read - or at least flicked through. But one of the few magazines I read all the way through is the Journal of Liberal History.

For some peculiar reason, even in this age of the internet, I still get too many magazines. They pile up for months, and sometimes longer than months, waiting to be read - or at least flicked through. But one of the few magazines I read all the way through is the Journal of Liberal History.I don't have to read the whole thing in this latest issue because one of the articles is by me: it is called 'Three acres and a cow' and it is about the story of the man who used the slogan, the Liberal MP and agrarian campaigner Jesse Collings (unfortunately requires password).

It tells the story of Collings' tireless campaign for allotments and smallholdings and why, when he was the inspiration behind the Allotments and Smallholdings Act 1908 - which David Cameron recently had to promise to protect - he actually voted against it. It is all in my ebook about the strange hidden history of the allotments movement.

The frustrating element of the tale is that the the kind of transformation in land ownership and small-scale agriculture Collings imagined, and could see in other European countries on his summer jaunts with Joseph Chamberlain, never came to pass.

The great opportunity that opened up for land reform on that scale in the UK was a victim Home Rule divisions in the Liberal Party and the frustration of Lloyd George’s Land Campaign by the First World War.

The 1885 slogan ‘Three acres and a cow’ continued to be associated with the Liberal Party well into the second half of the twentieth century, but with little understanding about its origins or objectives - which was all about giving the poor some measure of economic independence. When the generation after Collings began to pull together the lost and frayed strands of his campaign, they did so outside the Liberal Party.

Why? Well, it has something to do with Chamberlain's defection - along with radicals like Collings - to the Liberal Unionists. A generation later, the Fabian influence had crept into the mainstream Liberal Party - always a pity, it seems to me - and confusion about land ownership followed.

The main thrust of the 1906 Liberal government was to build on the idea of security of tenure and they saw it differently to Collings. ‘The magic of property, such as it is, is derived not from ownership but from security,’ said H. H. Asquith, the Home Secretary. So when the Liberals’ twin Smallholdings and Allotments Bills emerged, in 1907 and 1908, security not ownership was the objective.

In fact, would-be smallholders had to find a fifth of the purchase money themselves. This was the proposal of a commission chaired by the banker Sir Edward Holden, who said that a new land bank should only advance four-fifths of the price at 4 per cent interest.

New smallholding tenants would have to pay the interest on the loan to buy the land for their farms, but the ownership would still stay with the county councils. ‘It is, in short a communalization of the land, not at the expense of the hated landlord, but at that of the ‘sweated’ tenant,’ said a furious Collings.

The Left has been in a muddle about property and land ownership ever since.

Small-scale ownership isn't everything - especially if there is no security, as Asquith said - but people want a stake, in their own home or plot of land. The Left has missed the point by condemning all ownership - as if we should all be dependent tenants - when they should have been condemning large-scale ownership, landlordism, rentiers.

Liberalism remains confused, and has not given the development campaigns, in Latin America and India - to give people real ownership of a plot of land - the attention and support they needed.

The Fabian failure to understand the lure of ownership rights, and why it is so powerful - and why it is reasonable that people should want that kind of personal stake - has allowed the disaster of burgeoning house prices to come close to destroying the whole thing. It is currently flinging us back into the world of the rentier.

In other words, Collings was right.

Published on September 20, 2013 02:46

September 19, 2013

When hospitals start gaming with patients

I heard a fascinating anecdote yesterday about a senior doctor at one of the big London teaching hospitals, who joked that his patients left the hospital anaemic because they had gone through so many blood tests in his care.

I heard a fascinating anecdote yesterday about a senior doctor at one of the big London teaching hospitals, who joked that his patients left the hospital anaemic because they had gone through so many blood tests in his care.I was at an inspiring conference in Oxford organised by the Centre for Sustainable Healthcare, so there were a lot of this kind of anecdote around.

The doctor was exaggerating, of course, but for NHS insiders it is always obvious what he was talking about. The NHS payments system is set up so that there are endless blood tests, each one charged to the local CCG, and none of the results shared with other hospital departments.

One of the recommendations of my Barriers to Choice Review was that the Department of Health needs to look more closely at how the payment system is gamed. The initial response by the government agreed that this needed to be investigated and promised to work with Monitor to look at it. I hope they do.

Here is some of the gaming I’ve come across since then, and it goes way beyond just having blood tests over and over again:

Patients who are sent back to GPs when hospital tests reveal some other problem, because first referrals can be charged more than secondary referrals from inside the hospital.Hospital doctors who are forbidden to talk informally to GPs in case it prevents chargeable appointments.Out-patients departments which refuse to do one-stop shops because they can charge more by making patients come back.Regular six-month follow up appointments with hospital consultants, which have to be carried out face to face, whether patients need them or not.Out-patients departments (I heard this about an opthamology department) which fills up slots with patients who don’t really need to be there, to provide them with the income to treat the patients who do.

My feeling is that all these need to be classed as anti-competitive behaviour – deliberately wasting people’s time and wasting NHS resources to game the system for individual institutions or departments – but this is just a stopgap solution.

It is also unfairly condemnatory: the hospitals are responding to perverse signals by the payments system, and it is hard to blame them for that.

The real question is whether the NHS is being well served either by the split between primary and secondary care (which prevents integration) or by the split between purchasers and providers (which encourages gaming).

Most big corporations don t have internal markets like this because they know it wastes resources. There are exceptions, and they are usually a disaster (see what happened when they tried it at Sears).

It leads to internal squabbling and major waste. It also leads to a kind of accountancy arms race. When foundation trusts employ coders at £1,000 a day to push up each coding to a higher tariff (and they do), it forces CCGs to employ their own coders to challenge them.

Personally, I think the days of the internal market – a money-wasting innovation by management consultants McKinsey – are over. I’m not sure what needs to replace it, but it will certainly include integration, personal budgets, local accountability and flexibility.

Whatever payment system we choose need to encourage health units to reach out upstream of the demand, and act to reduce the number of alcohol-related admissions. Or the weight of depression. Or poor diets, or all the other things that so affect their ability to succeed. At the moment, they don't see this as their business, despite the huge impact it has on them.

In other words, we need an NHS that can look at the bigger picture intelligently, rather than acting like experimental rats in a maze. The coalition’s health and well-being boards may turn out to key to this at local level.

It would be ironic if they turned out to be a game-changer after all, but I think they will.

Published on September 19, 2013 01:40

David Boyle's Blog

- David Boyle's profile

- 53 followers

David Boyle isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.