David Boyle's Blog, page 70

September 18, 2013

School meals mustn’t mean trucking turkey nuggets

‘How on earth in austerity Britain can we afford Clegg’s £600m giveaway,’ asked the Daily Mail’s front page headline this morning, as if this was a bizarre luxury, a peculiar whim by the coalition’s junior partners.

‘How on earth in austerity Britain can we afford Clegg’s £600m giveaway,’ asked the Daily Mail’s front page headline this morning, as if this was a bizarre luxury, a peculiar whim by the coalition’s junior partners.There are a number of ways of addressing this, but it does imply just how strange the idea of prevention and investment to prevent is to the English soul.

Never mind that the Finnish approach to care and youth justice frontloads its spending into the early years to cut spending in later years – the reverse of our pattern in the UK. Never mind that Nurse-Family Partnerships, a mentoring programme for at-risk families giving birth in New York City, with 30 years of data, shows that savings carry on into until the baby is in its early twenties. English policy-makers seem not to get it (though, yes I know, Family-Nurse Partnerships (the UK version) have started here too).

So, of course the initiative to provide free school meals for the first three years in primary school is welcome – and important too. It is prevention in action. But there are two provisos that you can’t ignore.

One is that prevention is a far bigger challenge than school meals. It requires a constant effort to push spending further back up the chain of causality. It means blurring departmental boundaries until they practically disappear – it is ridiculous that prevention should be a burned sacrifice on the altar of long-running rivalry between Defra and the Department of Health on food.

And then there is the cost-benefit problem, constantly justifying prevention spending according to what it would save on budgets long gone by – when real prevention ought to mean a whole new kind of budgeting and a whole new understanding of what causes what.

But there is another proviso, and it is this.

Spending like this can potentially have a double or triple effect. It could be used to kick-start the local food economy in every area – a huge injection of economic localisation. It could mean a whole range of new food production and distribution enterprises, keeping the rewards local.

Alternatively it could go to a handful of big providers, on the grounds that trucking their turkey-chicken nuggets 300 miles a day for reheating is somehow more efficient.

One of the most exciting new food enterprises in Dorset started in reaction to Rentokil trucking in free school meals from Nottinghamshire (see picture).

It matters enormously which policy is pursued. One maximises the knock-on effects of prevention. The other is a waste of time and resources in comparison, and won’t result in effective employment for the disadvantaged children who eat the meals when they reach adulthood.

Published on September 18, 2013 11:07

September 17, 2013

Pretending there's no housing bubble

I was whizzing back down to London during the Lib Dems economy speech yesterday, but I watched it all later. Nick Clegg's summing up was highly effective. So was Vince Cable's 'hated Tories' speech later, not so much laying into his cabinet colleagues - as the news reports say - but laying into the election machinery behind them.

I was whizzing back down to London during the Lib Dems economy speech yesterday, but I watched it all later. Nick Clegg's summing up was highly effective. So was Vince Cable's 'hated Tories' speech later, not so much laying into his cabinet colleagues - as the news reports say - but laying into the election machinery behind them.But in retrospect, I find the whole business pretty infuriating. Clegg wasn't allowed to go over time - a sign of an authentic debate if ever there was one (I can't see Ed Miliband told to "bring his remarks to a close") - but the framing of the economy debate was obscure at best, and manipulative at worst.

It set the two sides arguing with each other on a series of propositions that nobody in the party would really disagree over. It sought out wafer thin, almost theological, distinctions - and pretended this was somehow a great victory or a great defeat.

Perhaps most annoyingly, it allowed the media to talk up a rift between Clegg and Cable when what was actually happening was a predictable rift between the Treasury and BIS. The economics motion was written from an irritatingly Treasury-centric standpoint, omitting what BIS was doing to rebalance the economy. That was what irritated Cable.

But perhaps the most annoying legacy of the debate is that it led otherwise sensible people like Danny Alexander to claim that there was no house price bubble. This gives the impression that there is somehow no problem about house prices - when actually the 30-year house price bubble is the biggest threat to the well-being of the next generation (see my book Broke ).

My own house would be worth £45,000 at average rates of inflation since 1937, when it was built, but it is actually now 'worth' ten times that. My children won't be able to afford to live in this not particularly prosperous south London suburb - not without 25 years indentured servitude in the financial industry (so much for wanting to be a teacher).

The truth is that the banks are, knowingly or unknowingly, stoking up house price rises because - at the moment - a worrying proportion of their property holdings are in negative equity. In fact, a quarter of their UK loans on commercial property are in that state. Of course they want to raise property prices up to the level of the last bubble - and they will: 70 per cent of business loans are on property.

These things matter. So why did the party engineer a conference debate dedicated to implying that somehow it doesn't?

I know, I know. It was all about what the government can do now - and the plan is to gear up local government borrowing to build affordable homes.

That is vital, but don't let's pretend that the property bubble hasn't been looming over our lives for a generation now. Any idea what the average UK home will be worth in 30 years time if prices rise until then as they have in the last 30 years? The answer is £1.2m.

Published on September 17, 2013 02:21

September 16, 2013

A nuclear compromise that makes me feel silly

I know. I look so youthful. You could hardly believe that I can remember the seventies. Unfortunately, I can. Winter of Discontent. Nuclear annihilation. Flared trousers, you know the kind of thing.

We used to talk then about the emergence of a new attitude in the UK: people who valued independence of mind and education, and put that above the need to impress their neighbours, people who believed in innovative local solutions, not big systems.

You might very well call them Liberal Democrats. I couldn’t possibly comment.

Years later, one of the gurus of this idea told me he had done a presentation at the Central Electricity Generating Board, the great bureaucratic monster which used to run energy in those days. Think of the supreme soviet, think Gromyko, mixed with a bit of Kafka.

The senior executive took him aside afterwards and asked him how he could recognise people like that - the 'inner directed' - in their own organisation.

'Why?' asked the speaker. 'I assume you want to encourage them.'

'No,' said the man from the CEGB. 'We want to root them out.'

So there was the great divide as we saw it then. Between energy produced by huge, technocratic, inflexible centralised systems run by men in white coats, and energy produced locally, where everyone has a stake, by solar panels on every roof top, every lamp-post, every structure, man made or otherwise. By every kind of renewable source, backed up for a time by the old sources.

And the only political force back in 1978 which recognised this idea, and which stood up against the disastrous nuclear reprocessing plant at Windscale/Sellafield, was the Liberal Party. Alone they went into the voting lobbies against the plutonium reprocessing plant that year. Of course I joined them; I joined them because they had a different vision of energy.

They still do even now, despite yesterdays vote.

But I'm more than a little sad that the party has abandoned its traditional, not to say heroic, opposition to nuclear energy - and I'm embarrassed too. The Lib Dems have appeared to have voted for an impossible option - backing nuclear expansion only if it involves no state subsidies - when everyone knows there isn't a nuclear plant in the world that can stand on its own two feet.

I don’t deny that climate change needs urgent action. But we have tried the nuclear path before, and it is achingly slow. By the end of the 1970s, nuclear was sucking up two thirds of the energy research budget. It will again. Experience from the seventies is that, once you go down the nuclear route, the sheer expense sucks up the available investment.

It’s the cuckoo in the nest. The triumph of hope over experience. Despite all the talk of a diverse portfolio, it squeezes out everything else.

Which brings me to Boyle’s Law.

I don't mean the way that liquids expand when heated, or anything like that. I mean this: Solar panels are bound to get cheaper and more efficient in the years ahead.

Every time manufacturing capacity doubles, the price of dollar energy drops by 20 per cent. They’re now so productive in Australia and Spain that the big utilities are trying to suppress them. The same old centralised CEGB thinking again. Actually, they hate diversity.

But here's the second part of Boyle's Law: nuclear is bound to get more expensive.

Because, of course the UK government is planning to subsidise via the price nuclear operators can sell at, and subsidising their responsibility for nuclear waste, for which there is still no long-term solution. And subsidising the insurance against devastating nuclear accidents. It isn’t economic otherwise.

Every time there’s a scare about terrorists getting hold of plutonium, and there are bound to be scares, the price will rise. Every time we worry about safety or security, the costs will increase. By going down this path, we will lock ourselves into those rising costs.

So I had hoped today we would shun the twentieth century technology, and go for a radical diverse local solution – not the rising costs of the men in white coats.

I might get over the disappointment, especially if we can define 'subsidy' properly, because it would rule out nuclear penjury. After 34 years in the party, I'm not going anywhere. But it is a bitter decision, for which I am going to have to suffer a great deal of ridicule in the green movement.

What makes it worse, I deserve to. It is ridiculous wishful-thinking. It is a bizarre compromise that makes no sense given the way the world is. It might feel nice to have a policy promising nuclear energy that pays its way, just as it might be nice to have an education policy where there no failing schools.

It is the politics of magic wands and makes the party look silly. Because nuclear energy doesn't pay its way anywhere and - according to Boyle's Law - it never will.

We used to talk then about the emergence of a new attitude in the UK: people who valued independence of mind and education, and put that above the need to impress their neighbours, people who believed in innovative local solutions, not big systems.

You might very well call them Liberal Democrats. I couldn’t possibly comment.

Years later, one of the gurus of this idea told me he had done a presentation at the Central Electricity Generating Board, the great bureaucratic monster which used to run energy in those days. Think of the supreme soviet, think Gromyko, mixed with a bit of Kafka.

The senior executive took him aside afterwards and asked him how he could recognise people like that - the 'inner directed' - in their own organisation.

'Why?' asked the speaker. 'I assume you want to encourage them.'

'No,' said the man from the CEGB. 'We want to root them out.'

So there was the great divide as we saw it then. Between energy produced by huge, technocratic, inflexible centralised systems run by men in white coats, and energy produced locally, where everyone has a stake, by solar panels on every roof top, every lamp-post, every structure, man made or otherwise. By every kind of renewable source, backed up for a time by the old sources.

And the only political force back in 1978 which recognised this idea, and which stood up against the disastrous nuclear reprocessing plant at Windscale/Sellafield, was the Liberal Party. Alone they went into the voting lobbies against the plutonium reprocessing plant that year. Of course I joined them; I joined them because they had a different vision of energy.

They still do even now, despite yesterdays vote.

But I'm more than a little sad that the party has abandoned its traditional, not to say heroic, opposition to nuclear energy - and I'm embarrassed too. The Lib Dems have appeared to have voted for an impossible option - backing nuclear expansion only if it involves no state subsidies - when everyone knows there isn't a nuclear plant in the world that can stand on its own two feet.

I don’t deny that climate change needs urgent action. But we have tried the nuclear path before, and it is achingly slow. By the end of the 1970s, nuclear was sucking up two thirds of the energy research budget. It will again. Experience from the seventies is that, once you go down the nuclear route, the sheer expense sucks up the available investment.

It’s the cuckoo in the nest. The triumph of hope over experience. Despite all the talk of a diverse portfolio, it squeezes out everything else.

Which brings me to Boyle’s Law.

I don't mean the way that liquids expand when heated, or anything like that. I mean this: Solar panels are bound to get cheaper and more efficient in the years ahead.

Every time manufacturing capacity doubles, the price of dollar energy drops by 20 per cent. They’re now so productive in Australia and Spain that the big utilities are trying to suppress them. The same old centralised CEGB thinking again. Actually, they hate diversity.

But here's the second part of Boyle's Law: nuclear is bound to get more expensive.

Because, of course the UK government is planning to subsidise via the price nuclear operators can sell at, and subsidising their responsibility for nuclear waste, for which there is still no long-term solution. And subsidising the insurance against devastating nuclear accidents. It isn’t economic otherwise.

Every time there’s a scare about terrorists getting hold of plutonium, and there are bound to be scares, the price will rise. Every time we worry about safety or security, the costs will increase. By going down this path, we will lock ourselves into those rising costs.

So I had hoped today we would shun the twentieth century technology, and go for a radical diverse local solution – not the rising costs of the men in white coats.

I might get over the disappointment, especially if we can define 'subsidy' properly, because it would rule out nuclear penjury. After 34 years in the party, I'm not going anywhere. But it is a bitter decision, for which I am going to have to suffer a great deal of ridicule in the green movement.

What makes it worse, I deserve to. It is ridiculous wishful-thinking. It is a bizarre compromise that makes no sense given the way the world is. It might feel nice to have a policy promising nuclear energy that pays its way, just as it might be nice to have an education policy where there no failing schools.

It is the politics of magic wands and makes the party look silly. Because nuclear energy doesn't pay its way anywhere and - according to Boyle's Law - it never will.

Published on September 16, 2013 00:19

September 15, 2013

Strange to be blog of the year

Would you believe it. I can’t quite believe it myself, but you are now reading the Lib Dem Blog of the Year 2013.

Would you believe it. I can’t quite believe it myself, but you are now reading the Lib Dem Blog of the Year 2013.I feel slightly embarrassed to admit this, because I have only been blogging seriously since February, and I was among a number of really brilliant fellow nominees, any of whom could have won. So I am ever so grateful to those who nominated me – and very grateful to my fellow nominees who I have read to learn how to do it.

I have run this blog since 2007, but in rather a fitful way – and gave up entirely while I was at the Cabinet Office organising an independent review. It didn’t seem to fit very comfortably with being independent.

Then, earlier this year, in a desperate attempt to sell a few of my books, I started doing in every day. Soon I couldn’t stop. Goodness knows where all this will end.

So there I was at the Lib Dem Voice awards last night in the Crown Plaza hotel in Glasgow, which – like the conference centre – is a bit like Hampton Court maze, minding my own business, having been assured that I was quite safe and I didn’t have a cat in hell’s chance of winning.

What was I to say? Well, blogs are an effective protection for people who don’t think very well on their feet. Of course I hadn’t the foggiest idea what to say then.

So I’m just going to devote this post to a few more expressions of gratitude . . .

. . . to everyone who has been reading what I write, and who devote those minutes from their precious days to visiting my mind, however briefly. Even if they don’t agree. Especially if they don't agree.

. . . to everyone who sends me links to things they think will interest me.

. . . to everyone who has encouraged me by tweeting or telling me that they enjoyed reading the blog, and that the ideas I’ve struggled to express are worth struggling to express.

. . . to everyone who has taken the irrevocable step of actually buying one of my books as a result. You’ve made a middle-aged man very happy.

. . . to all my fellow bloggers who are dedicated to the grand cause that conversation about ideas, with ideas, for ideas, shall not perish from the Lib Dems.

Published on September 15, 2013 03:36

September 14, 2013

Why we need new institution builders

Thank you to everyone who came along to hear Harriet Sergeant, Stephanie Flanders and I, slugging it out at the Chiswick Book Festival this morning. It was packed out in the Tabard Theatre and it was a fascinating conversation, thanks largely to Stephanie's chairing powers.

Thank you to everyone who came along to hear Harriet Sergeant, Stephanie Flanders and I, slugging it out at the Chiswick Book Festival this morning. It was packed out in the Tabard Theatre and it was a fascinating conversation, thanks largely to Stephanie's chairing powers.The session was billed as a discussion about our failing institutions, and - even though I talked about the middle classes and Harriet talked about south London gangs - there did seem to be some parallels.

What I argued in Broke is that the middle classes have been taken for a ride by the financial institutions they clung to. They were not sinless. They colluded in the results, confusing the notional value of their homes with real wealth, but they were still taken for a ride - and their miserable pensions, corroded by hidden charges, and the bleak outlook when it faces their children earning a roof over their heads, are the legacy.

But there is another link which we might have missed.

Our institutions have been hollowed out, partly by greed and arrogance (the financial ones), partly by digital Taylorism (the public services ones). Our leaders delude themselves as they look at the wholly misleading figures that pour out of the frontline - unaware, apparently, of how distant from reality they are.

But the great strength of the middle classes, not exclusively of course, is that they are institution builders. And never has our economy and society required effective institutions as much as they do now.

As I wrote this, I am travelling to Glasgow in a Virgin train where the seat reservations had not been downloaded until we left Euston, where there are no hot drinks because the boiler has broken down, and where they are too short staffed to provide a service in first class (so they tell me; I'm in third class). It is the UK's institutional failure in microcosm.

So I hope that the middle classes will realise the plight that faces their children and will create the institutions we need to give them a chance.

Effective banks are urgently required. Local lending institutions. Food businesses. Effective institutions capable of educating everyone, not giant factories dedicated to delivering outputs. And we need thousands of new enterprises to take on the monopolies - starting with a real UK competitor to Amazon.

So there we are. The middle classes. They might look like the problem, but potentially they are part of the solution.

Published on September 14, 2013 09:23

September 13, 2013

The Sound of Gunfire revisited

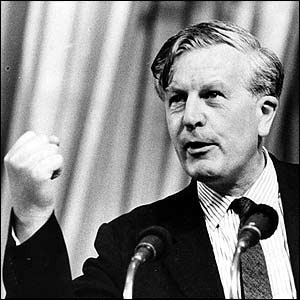

Tomorrow, I am reliably informed (thank you, Simon), is the 50th anniversary of Jo Grimond’s famous ‘Sound of Gunfire’ speech – probably the most famous speech he made, and a key moment in the very first Liberal Revival.

Tomorrow, I am reliably informed (thank you, Simon), is the 50th anniversary of Jo Grimond’s famous ‘Sound of Gunfire’ speech – probably the most famous speech he made, and a key moment in the very first Liberal Revival.I’ve just been reading it and it is strangely dated, perhaps not surprising given that it was given a month after Martin Luther King’s I Have a Dream speech and two months before the assassination of John Kennedy. In other words, it was a long time ago.

But the final peroration is memorable and important, especially for the generation of Liberals before mine, and here it is:

"War, delegates - war has always been a confused affair. In bygone days, the commanders were taught that when in doubt they should march their troops towards the sound of gunfire. I intend to march my troops towards the sound of gunfire. Politics are a confused affair and the fog of political controversy can obscure many issues. But we will march towards the sound of the guns...The reforms which we advocate are inexorably written into the future. We move with the great trends of this century. Other nations have rebuilt their institutions under the hard discipline of war. It is for Liberals to show that Britain, proud Britain, can do this as a free people without passing through the furnace of defeat."

It isn’t just nostalgic reading it now. There is something poignant about it. Take this, for example:

"What should citizenship of Britain mean today? What should we create here to which people would assent, so that people will be able to say, ‘I lived in the Sixties and Seventies and, for all my life, I shall be proud of the public life of my country’? What can we do to restore that confidence, that optimism, to draw people once again into their country’s affairs and give back power to the decent, hard-working, general British citizen?"

We know now that what actually lay ahead was stagnation, inflation, industrial standstill and a staggering lack of imagination. We also know that what those of us who actually lived through the 60s and 70s would remember – and the abiding greatness of the time – was the creative and cultural explosion, and which took place despite the absence of political leadership.

I remember, when I first went to a Liberal assembly (1982), I shared some of this sense of exclusion that you get in this speech – and, hey, let’s face it, that is the core of the Liberal psychology: we all feel a little left out. It seemed to me, then and now, a tragedy that UK politics had excluded its Liberal heritage and tradition.

We may not have changed things if Grimond had really succeeded in marching his troops to the sound of gunfire, but we would have injected that Liberal creativity into the political process as well as the cultural one.

What we did do was to create a revolution in local government, though even that was two decades away or more from Grimond's speech.

I remember, as a local government reporter in the early 1980s, a Labour councillor boasting to me that he simply threw away any letters addressed to him at home, because of the sheer cheek of his constituents writing to him there.

In those days, the public was excluded from many council meetings. They were not allowed to speak. Those one-party states in cities and counties led to stagnation, complacency, corruption, and some of the most inhuman public housing in the world.

The Liberals and then the Lib Dems were history’s chosen instrument. They broke that whole edifice apart.

And then, of course, they found themselves in government, and this is where the metaphor of the sound of gunfire is important. Grimond might equally have talked about Nelson’s injunction to “engage the enemy more closely”.

In both cases, it is critically important for the generals and admirals – and their troops – to know what is possible and who is on their side. They need to know what they are for and where they are heading. Because, as Grimond said, war is "a confused affair".

So I was fascinated to read Peter Oborne’s unexpected tribute to Nick Clegg in the Daily Telegraph this week, and to his leadership skills. And I think he is right. The Lib Dems haven’t been immune to mistakes in office – far from it – but they have been led with very great skill, hour-by-hour balancing the needs of the party with the needs of the country, and what is possible.

There are a whole list of ways in which the policies of the coalition are imperfect, often worse. But when you march towards the sound of gunfire, it makes no sense to mouth the word ‘betrayal’ at every imperfection and misjudgement, when the people leading us have imperfect information at the time, and have almost no time to form an opinion.

So I was sorry to see the barrage of criticism of Clegg over the David Miranda arrest when all he was guilty of, it seemed to me, was vetoing the idea of prosecuting the Guardian.

Heavens, I’m a Liberal. I believe in independence of mind. The idea of party discipline sticks in the throat. But it isn’t in the spirit of the Sound of Gunfire, the path that Grimond laid down, to constantly question the motives of our colleagues.

The battle is too confused for that. When the gunfire has died away, then we might have a chance to see more clearly. But for now, in the heat of battle, we do have to stick together if we possibly can. Not uncritically, but remembering that this is a very long march indeed.

It may be portentous to say so, but I think the Grimond legacy is our ability, generally speaking, to do so. We are able to do so only to the extent that we know what we are as Liberals, and that is thanks to Grimond.

Published on September 13, 2013 01:23

September 12, 2013

Come and debate with me in Chiswick

It really is quite extraordinary how much of our newspapers are taken up by two kinds of stories, which now seem to dwarf the rest. One is allegations of various kinds of sex abuse, the other is the gamut of possible scandals around care, services, measurement and inspection.

It really is quite extraordinary how much of our newspapers are taken up by two kinds of stories, which now seem to dwarf the rest. One is allegations of various kinds of sex abuse, the other is the gamut of possible scandals around care, services, measurement and inspection.When the history of the 2010s come to be written - and it would be nice to think I might write it myself - we may have to understand our obsession with these issues.

I'm not, of course, saying they are unimportant. I am though wondering why they take up quite so much news space, to the exclusion of so much else.

I also think they have something in common. Both are about the suspicions we share about the institutions we rely on. That is the question of the age, because so many of our institutions - public and private - have been hollowed out by the kind of digital Taylorism I wrote about yesterday.

So many of our institutions have had the human element surgically removed, rendering them ineffective and increasingly expensive.

I mention all this because I am doing a session at the Chiswick Book Festival on Saturday (11.45am) with Harriet Sergeant, author of Among the Hoods. It is called 'How Right and Left both got it wrong' and it is about precisely this: how our institutions failed us.

Harriet will be talking about her experience with gang members in Brixton. Anyone who has read her absolutely compelling book will know the criticism she reserves for the hopeless processes at the welfare agencies and Job Centre.

I'm talking about my book Broke: Who Killed the Middle Classes? and there is a similar problem there too: the crisis of the middle classes is not despite our financial institutions, it is because of them. They may have taken the middle classes for a ride with their naive connaivance, but they certainly took them for a ride. They are still doing so.

So come along and let's talk about whatever happened to our institutions. And it is being chaired by Stephanie Flanders!

Published on September 12, 2013 06:57

September 11, 2013

Spraying extra costs around public services

Where did it come from, this obsession with targets, with breaking down every aspect of a task into little bits that can be measured and processed?

Some people date it back to the moment in 1903 when the time and motion study pioneer Frederick Winslow Taylor rose to his feet in Saratoga Springs to explain his idea that every factory could be measured to work in what he called ‘the one best way”. (More about Taylor in my book Broke).

Maybe it was actually James Oscar McKinsey, the first management consultant. Whose consultancy still lives and dies by the highly misleading maxim “everything can be measured and what can be measured can managed”.

Maybe it was the technocrat’s technocrat, Robert Macnamara, who imposed ‘kill quotas’ on soldiers in the Vietnam War, only to find that the deaths rose but victory stayed elusive.

Whatever it was, the management business has spawned a vast industry which churns out targets, specifications, standards and obscure acronyms, while an even bigger industry puts them into effect. The idea dominates consulting just as it now dominates government – the Blair government introduced 10,000 new numerical targets in their first term of office, on everything from vandalism to the state of sailor’s teeth in the navy.

The great mistake this approach makes is that it breaks processes down into parts and measures them, just like an assembly line.

The trouble with processing people according to numerical categories is that it feels alienating. You start feeling outraged and end just feeling hopeless. The feeling of processing us all as assembly lines would has been set out brilliantly by the extremely clear-thinking blog System Thinking for Girls. It is a letter to big organisations explaining what it feels like:

"In big organisations, armies of people are employed to disguise original humans as categories, types and tariffs. This is done via documents and screens often by people who have never met or spoken to the original human."

This is the philosophy of the 'back office'. But note this: the letter isn’t really about dehumanising people. It is about the ineffectiveness that creeps in when you do so.

I hesitate to call these ‘inefficiencies’ because the search for 'efficiencies' has paradoxically created these extra costs which now weigh down public services as a result. Because real people aren’t like that – they are complex and usually non-standard and they need to be dealt with by a system that can deal with this variety.

The assembly line system, embedded in IT systems, can’t do this. The costs mount as all us non-standard people start bouncing around inside the system, creating costs, unprocessable. They mount because none of the available interventions on the organisations' dashboards really suit us. More about this in my book The Human Element.

And here, in a nutshell, is the reason why costs have been rising in public services, and will rise even faster as the big organisations start winning contracts and cut costs in this way – the Virgin Healthcare, Atos, G4S systems of this world.

This is not a privatisation problem. There is no reason why private organisations should not deliver services, as long as they are integrated – as GP surgeries have done since 1948. The problem is scale and wrong-headed systems.

Here is the reason why this kind of out-sourcing, to the out-sourcing giants, is going to be so expensive. Because they don’t just increase their own costs, often paid for on the basis of throughput by unsuspecting commissioners, they spray extra costs around the rest of the system.

They do so by narrowing the definition of what their systems are supposed to achieve, reducing them to numerical outputs which can be measured, and letting someone else pick up the bill for everything else - and for the failure of these Mc-interventions to work.

Then they can get paid for doing it twice, and three times, and so on and so on.

That is the problem a new approach to public services will have to tackle. It isn’t public versus private. It is big versus small. It is effective systems versus so-called efficient ones.

Some people date it back to the moment in 1903 when the time and motion study pioneer Frederick Winslow Taylor rose to his feet in Saratoga Springs to explain his idea that every factory could be measured to work in what he called ‘the one best way”. (More about Taylor in my book Broke).

Maybe it was actually James Oscar McKinsey, the first management consultant. Whose consultancy still lives and dies by the highly misleading maxim “everything can be measured and what can be measured can managed”.

Maybe it was the technocrat’s technocrat, Robert Macnamara, who imposed ‘kill quotas’ on soldiers in the Vietnam War, only to find that the deaths rose but victory stayed elusive.

Whatever it was, the management business has spawned a vast industry which churns out targets, specifications, standards and obscure acronyms, while an even bigger industry puts them into effect. The idea dominates consulting just as it now dominates government – the Blair government introduced 10,000 new numerical targets in their first term of office, on everything from vandalism to the state of sailor’s teeth in the navy.

The great mistake this approach makes is that it breaks processes down into parts and measures them, just like an assembly line.

The trouble with processing people according to numerical categories is that it feels alienating. You start feeling outraged and end just feeling hopeless. The feeling of processing us all as assembly lines would has been set out brilliantly by the extremely clear-thinking blog System Thinking for Girls. It is a letter to big organisations explaining what it feels like:

"In big organisations, armies of people are employed to disguise original humans as categories, types and tariffs. This is done via documents and screens often by people who have never met or spoken to the original human."

This is the philosophy of the 'back office'. But note this: the letter isn’t really about dehumanising people. It is about the ineffectiveness that creeps in when you do so.

I hesitate to call these ‘inefficiencies’ because the search for 'efficiencies' has paradoxically created these extra costs which now weigh down public services as a result. Because real people aren’t like that – they are complex and usually non-standard and they need to be dealt with by a system that can deal with this variety.

The assembly line system, embedded in IT systems, can’t do this. The costs mount as all us non-standard people start bouncing around inside the system, creating costs, unprocessable. They mount because none of the available interventions on the organisations' dashboards really suit us. More about this in my book The Human Element.

And here, in a nutshell, is the reason why costs have been rising in public services, and will rise even faster as the big organisations start winning contracts and cut costs in this way – the Virgin Healthcare, Atos, G4S systems of this world.

This is not a privatisation problem. There is no reason why private organisations should not deliver services, as long as they are integrated – as GP surgeries have done since 1948. The problem is scale and wrong-headed systems.

Here is the reason why this kind of out-sourcing, to the out-sourcing giants, is going to be so expensive. Because they don’t just increase their own costs, often paid for on the basis of throughput by unsuspecting commissioners, they spray extra costs around the rest of the system.

They do so by narrowing the definition of what their systems are supposed to achieve, reducing them to numerical outputs which can be measured, and letting someone else pick up the bill for everything else - and for the failure of these Mc-interventions to work.

Then they can get paid for doing it twice, and three times, and so on and so on.

That is the problem a new approach to public services will have to tackle. It isn’t public versus private. It is big versus small. It is effective systems versus so-called efficient ones.

Published on September 11, 2013 02:12

September 10, 2013

NHS IT: time to try another way

Many years ago, right back in the mid-to-late 1980s, I was editor of a wonderful magazine called Town & Country Planning. My successor has done an excellent job ever since, but I have always missed it.

I remember, in those days, how many reports used to cross my desk about the estimated value of private sector housing dilapidations - the total amount that was required to repair the UK's housing stock.

One of the peculiar side-effects of the Lawson-inspired house price inflation which hit us about the time I moved on has been that we don't get so many of those reports any more. A combination of equity in the home and a nearby DIY store has kind of tackled the problem.

Here is the point I'm making. In the end, the problem wasn't solved by major investment by central government, as the authors of the reports tended to assume. It wasn't solved by a new government agency sending out approved designs. It was solved by tens of millions of ordinary homeowners, and especially young ones, going down to the shop and buying paint - and spending their weekends using it.

I simplify, of course. But sometimes the top-down solution isn't the best one. Often it isn't possible or affordable.

I have been thinking about this and how it relates to the perennial problem of NHS patient information, and how you tackle the parallel problem of lost notes.

We can be reasonably sure, after £12 billion went down the drain last time, that the top-down approach does not work, though that will not stop them trying again.

The influential NHS blogger Roy Lilley tackled the issue again a few days ago, and I was distressed to hear that a new attempt is being made. Unfortunately, the new announcement makes horribly similar noises to the old ones.

But Lilley also pointed the way forward towards the equivalent bottom up, DIY solution. St Helens and Knowsley Foundation Trust have a scheme called 'bring your own device 2 work', which allows all the staff's variety of systems to talk to each other - but not allow information out beyond them.

Last year, I met a pioneer of a similar bottom up solution that I believe will soon be widely adopted. Patients Know Best is a social enterprise started by a tech-savvy doctor called Mohammad Al-Ubaydli, and chaired by the distinguished former BSJ editor Dr Richard Smith.

It requires us to turn our idea of patient information on its head. Instead of the NHS owning the information about you, and getting itself into a terrible mess dealing with other agencies, and constantly asking permission to share information, PKB suggests that you should own the information yourself.

It requires a simple piece of software, and it means that you can give or withdraw access to your own information to whichever professionals in whichever public services you need.

Great Ormond Street adopted it for their patients some time ago, and the PKB approach is now spreading through GP surgeries in Kent. There is no reason either why it should be limited to health.

It requires no vast investment from IT consultancies. It doesn't require taxpayers to lose another £12 billion organising one inflexible centralised system.

It also fosters the kind of equal relationship between patient and professional that the NHS badly needs. It also, and here is the real reason for writing this, is the kind of entrepreneurial approach to government described in a fascinating American article about 'agile public leadership' (thank you, Ted, for sending it).

It is characterised by US chief technology officer Todd Park as “think big, start small, scale fast”. That is precisely the PKB model, rather than the lumbering top-down brontosaurus approach to IT that Whitehall still favours far too often.

I remember, in those days, how many reports used to cross my desk about the estimated value of private sector housing dilapidations - the total amount that was required to repair the UK's housing stock.

One of the peculiar side-effects of the Lawson-inspired house price inflation which hit us about the time I moved on has been that we don't get so many of those reports any more. A combination of equity in the home and a nearby DIY store has kind of tackled the problem.

Here is the point I'm making. In the end, the problem wasn't solved by major investment by central government, as the authors of the reports tended to assume. It wasn't solved by a new government agency sending out approved designs. It was solved by tens of millions of ordinary homeowners, and especially young ones, going down to the shop and buying paint - and spending their weekends using it.

I simplify, of course. But sometimes the top-down solution isn't the best one. Often it isn't possible or affordable.

I have been thinking about this and how it relates to the perennial problem of NHS patient information, and how you tackle the parallel problem of lost notes.

We can be reasonably sure, after £12 billion went down the drain last time, that the top-down approach does not work, though that will not stop them trying again.

The influential NHS blogger Roy Lilley tackled the issue again a few days ago, and I was distressed to hear that a new attempt is being made. Unfortunately, the new announcement makes horribly similar noises to the old ones.

But Lilley also pointed the way forward towards the equivalent bottom up, DIY solution. St Helens and Knowsley Foundation Trust have a scheme called 'bring your own device 2 work', which allows all the staff's variety of systems to talk to each other - but not allow information out beyond them.

Last year, I met a pioneer of a similar bottom up solution that I believe will soon be widely adopted. Patients Know Best is a social enterprise started by a tech-savvy doctor called Mohammad Al-Ubaydli, and chaired by the distinguished former BSJ editor Dr Richard Smith.

It requires us to turn our idea of patient information on its head. Instead of the NHS owning the information about you, and getting itself into a terrible mess dealing with other agencies, and constantly asking permission to share information, PKB suggests that you should own the information yourself.

It requires a simple piece of software, and it means that you can give or withdraw access to your own information to whichever professionals in whichever public services you need.

Great Ormond Street adopted it for their patients some time ago, and the PKB approach is now spreading through GP surgeries in Kent. There is no reason either why it should be limited to health.

It requires no vast investment from IT consultancies. It doesn't require taxpayers to lose another £12 billion organising one inflexible centralised system.

It also fosters the kind of equal relationship between patient and professional that the NHS badly needs. It also, and here is the real reason for writing this, is the kind of entrepreneurial approach to government described in a fascinating American article about 'agile public leadership' (thank you, Ted, for sending it).

It is characterised by US chief technology officer Todd Park as “think big, start small, scale fast”. That is precisely the PKB model, rather than the lumbering top-down brontosaurus approach to IT that Whitehall still favours far too often.

Published on September 10, 2013 02:39

September 9, 2013

Big banks: let's learn from Little Red Riding Hood

The most popular version of Little Red Riding Hood has the woodman storming into the Grandmother's house at the end of the story, killing the wicked wolf and slitting open his stomach - and, unharmed, out pops Little Red Riding Hood and her grandmother, none the worse for a bit of mild digestion. I've always wondered about this when I thought of Britain's dysfunctional and over-concentrated banking system, and the announcement yesterday about the rebirth of Trustee Savings Bank as a separate organisation rather confirms it.

The most popular version of Little Red Riding Hood has the woodman storming into the Grandmother's house at the end of the story, killing the wicked wolf and slitting open his stomach - and, unharmed, out pops Little Red Riding Hood and her grandmother, none the worse for a bit of mild digestion. I've always wondered about this when I thought of Britain's dysfunctional and over-concentrated banking system, and the announcement yesterday about the rebirth of Trustee Savings Bank as a separate organisation rather confirms it.Let me explain. In a flurry of consolidation, our banks wolfed each other down in the half century between 1870 and 1920 until there were just five left (and a few stragglers).

The culprit – probably more than the others – was Barclays, then known as Barclay, Bevan, Tritton, Ransom, Bouverie and Co, or in the City of London as the ‘long firm’. In 1896 they persuaded nine smaller banks to join them, mainly in the East and North, in a major enterprise to secure Barclays for the future.

This was a period when the middle classes were flocking to open bank accounts, just as the local banks which had served their forefathers disappeared month by month into the jaws of the City.

By the outbreak of the First World War, Barclays had doubled their branches, mainly by the most frenetic merger activity, starting straight away with the Newcastle bank Woods & Co. Their biggest takeover was the Consolidated Bank of Cornwall in 1905, itself a recent merger of family banks. The most dramatic was the purchase of United Counties Bank, giving Barclays a major presence across the Midlands.

By 1918, even the government was worried about this merger mania, and appointed a committee of inquiry which urged it to legislate at once. Being the British government, it never quite got round to the task, and agreed to drop the idea of anti-trust legislation – which was bitterly opposed by the banks – on condition that there would be no more mergers between the big ones.

Desperate to get under the wire, Barclay’s just had time to snap up the massive 601 branches of the London, Provincial and Western Bank. By 1920, they employed 11,000 clerks in 1,783 branches. There were now five big banks left standing: Midland, Westminster, Lloyds, Barclays and National Provincial (not the same Big Five of today, it is true).

It was already the most concentrated banking infrastructure in the world, and deeply conservative - one of the features of industries with no proper competition is conservatism, and so it was back then.

Left-handed people were banned from bank staff, at least in Barclays. Women were dismissed when they got married. Board minutes were still written by hand. In Barclays, ledger clerks were issued with special ink designed to clog any new fountain pens, which the banking oligarchy disapproved of.

In Manchester, banks were still transferring cash across the city using the last horse-drawn cabs as late as 1940. Now our banks have their attentions elsewhere, and take their domestic banking customers staggeringly for granted - as you would expect where there is no competition. They were allowed to swallow the competition, just as - only a decade ago - they swallowed most of the building societies.

So here is the question, and I asked it with more explanation and anecdote in my new book Broke (because the failing banking infrastructure is complicit in the demise of traditional middle class values) - do these forgotten banks still exist inside the belly of the wolves?

I know, it is true, that the branches being liberated by Lloyds are not the original TSB branches - most of them are former Cheltenham & Gloucester Building Society branches. It is also true that the new TSB will have to develop the skills required for local lending which have atrophied inside Lloyds.

But it is a start. Now what we have to do is to have the guts to act like the woodcutter in the tale of Little Red Riding Hood.

Round up the big bad wolves of banking, slit open their stomachs, and let the institutions we need come back out again into the light – the Woolwich (inside Barclays), Bristol & West (inside Bank of Ireland), Halifax (inside Lloyds), Girobank (Santander), Williams & Glyn’s (Royal Bank of Scotland), Martin’s (Barclays), Birmingham Municipal Savings Bank (Lloyds). And so on and so on.

Published on September 09, 2013 02:53

David Boyle's Blog

- David Boyle's profile

- 53 followers

David Boyle isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.