David Boyle's Blog, page 68

October 9, 2013

Big Landlord is watching you

I've been listening to a programme about a man from East Germany bursting through the Berlin Wall in an armoured car in 1963. It reminded me of a good test of Liberalism, which is this: where would you rather live?

I've been listening to a programme about a man from East Germany bursting through the Berlin Wall in an armoured car in 1963. It reminded me of a good test of Liberalism, which is this: where would you rather live?Despite the sympathy from the left in Western Europe that East Germany occasionally managed to conjure up, I am not aware of any examples of people from the West trying to escape to the East across the Berlin Wall. It was all the other way. Ask yourself: where would you rather live?

I try and use that simple question for deciding - just to conjure a question out of the hat - whether we ought to support home ownership or home renting for the mass of the population.

The reason I choose this example particularly is because I was on the receiving end of a particularly thoughtful review of my book Broke: Who Killed the Middle Classes? by the doyen of Lib Dem bloggers, Mark Pack (thank you, Mark). In it, he says that I am "not easily categorisable on the left/right spectrum" - which I take as a huge compliment.

But he also says this:

"It would have been interesting to hear more about whether or not David Boyle wants to make renting become a middle class norm and if so,the policies to make this a good outcome..."

The answer is that I don't. Not because I believe that the current method of distributing homes to people works - it patently doesn't, plunging people into 25 years of indentured servitude to their mortgage provider. But because I tend towards John Maynard Keynes' enthusiasm for "the euthanasia of the rentier".

For all the effort by the Fabian left to enthuse people about a life of renting, it is only too obvious why - generally speaking - people want to own homes rather than rent them if they possibly can (there are obvious exceptions to this, but you get the point).

It means there will come a time when they are not paying out rent. It means they can have funny wallpaper or pull down walls or do strange things to the garden. It means that, once the mortgage is paid off, they have an asset which nobody can take away, even when they fall on hard times. It means they can work as authors or artists or poets without worrying where the rent is going to come from. In short, it underpins their independence.

Of course people want to own. It makes them that much more economically independent, and in an uncertain world that is enormously important - it means that their home will not be taken away either by state authority or by the power of the market. That is why people like G. K. Chesterton supported small-scale property ownership as the radical solution - and why I do.

To suggest that people should embrace renting because it might be good for them may not be a lordly 'let them eat cake!' But it is a lordly 'let them live in rented accommodation!'.

It really makes no difference if the landlord is the public or voluntary sector. As yourself: what would you prefer? Especially as the public sector has an appalling record since 1960 of designing homes for their poor tenants.

But don't let's muddle this up with the wholly indefensible housing market, which - far from underpinning independence is now actually hastening slavery. It spreads indebtedness, undermines our ability to choose a career (we have to work in financial services) and looks set to impoverish our children. It also raises rents.

And it excludes an increasing proportion of the population. So much for a property-owning democracy.

The decision to press ahead further with the Help to Buy scheme this week is a particular disaster. It makes homes more affordable without doing anything to bring down prices, which can only push them up further. If prices rise in the next 30 years in the UK like they have in the last 30 years, the average UK will cost £1.2m - a kind of debt bondage for nearly all of us.

So what should we do? The answer has to be create parallel home ownership schemes which makes homes available to more people on a different basis, and which also brings down prices in the market.

Community Land Trusts are one way forward, dividing the ownership of the home itself from the ownership of the underlying land, which is then held mutually. But that relies on getting hold of the land affordably.

My own priority would be to shift money from regeneration into building homes for sale at a nominal price - an end to the lie of 'affordable' homes at £350,000 - on condition that the home can only be sold on at the same price it was originally sold for.

If we can build enough, and if it provides a genuine alternative, a parallel housing market, then it may offer a lifeline out of the bizarre and tyrannical pyramid scheme that our homes have become.

Published on October 09, 2013 02:32

October 8, 2013

Dreaming of target-free schooling

I had a short argument about targets last week. It made me feel quite nostalgic. I haven’t had one for years, not since the coalition promised to do away with them.

I had a short argument about targets last week. It made me feel quite nostalgic. I haven’t had one for years, not since the coalition promised to do away with them.They haven’t of course, though many targets have gone. In fact, they have introduced new ones in the form of payment-by-results contracts, turbo-charged with money. But for some reason, the arguments stopped.

Maybe this is a sign that people are hankering a little after the old days, though they are not that different to today. Yes, I know that payment-by-results targets are supposed to be about ‘outcomes’ and old-fashioned targets are about ‘outputs’ – but, in practice, those are not very different, and equally perverting. Real outcomes are not susceptible to counting.

There is a great deal of evidence that targets achieved what they were trying to do - of course they made the targets higher - but I’ve come across almost no evidence that they made services better.

Nobody after the Mid Staffs Hospital furore could possibly believe they also provide accountability or transparency – only for the narrow stuff that is actually being counted.

Perhaps there is a nostalgia setting in for the good old-bad old days of Deliverology and my book The Tyranny of Numbers (both circa 2001).

I thought of all this opening my Evening Standard yesterday evening to read, to my great astonishment, an op-ed article about education which I completely agreed with. I don’t think this has ever happened before. I am more crotchetty about education than anything else.

It is by the headteacher of School 21 in Stratford, Peter Hyman. School 21 is a non-selective free school in Newham with pupils all the way from 4-18.

He argues, quite correctly, that we are getting increasingly good at organising schools as they were designed a century or so ago, and then he gives a brief portrait – though he doesn’t put it like this – of a target-driven school:

“A relentless focus on the basics, a boot-camp approach to behaviour management and massive intervention in Years 10 and 11 to convert every D grade into a C grade.”

There is the basic New Labour school design (though ironically, Hyman was an education advisor to Tony Blair). That is what targets did to our schools, and it is a credit to teachers that – despite this hollowing out – they are as good as they are. Not just targets either but best practice, approved process, standards and single bottom lines in the shape of league tables geared too narrowly.

But of course Hyman is right. We need to get with what we need now.

As he says, we need to teach character as well as facts (and I’m not as much against facts as the chattering classes would suggest I should be). We need to teach children to be resilient and articulate and creative.

But what really grabbed my attention was this sentence:

“We believe that schools should be small, so that no child falls through the cracks and everyone has an education tailored to their needs.”

That is absolutely right. Factory-scale schools have been the direction now for a generation. They are the prime underlying cause of the middle-class panic. They infect our education system with alienation and inflexible systems – they are the precise opposite of the way we should be going.

According to American educationalists, the reason why received wisdom originally suggested that schools should be big was after the panic in American circles int he late 1950s, when they believed that the Russian edge in the Space Race was down to big schools.

Later, it was so obviously in the interests of the salaries of senior teachers that they have continued growing.

The first challenge to it came from Roger Barker, whose 1964 book Big School, Small School , with his colleague Paul Gump, first revealed that – despite what you might expect – there were more activities outside the classroom in the smaller schools than there were in the bigger schools. There were more pupils involved in them in the smaller schools, between three and twenty times more in fact. He also found children were more tolerant of each other in small schools.

This was precisely the opposite of what the big school advocates had suggested: big schools were supposed to mean more choice and opportunity. It wasn’t so.

Nor was this a research anomaly. Most of research has been carried out in the United States, rather than the UK, but it consistently shows that small schools (300-800 pupils at secondary level) have better results, better behaviour, less truancy and vandalism and better relationships than bigger schools. They show better achievement by pupils from ethnic minorities and from very poor families.

More on this in my book The Human Element.

But small schools is a long way from where we are now. And thanks to the failure of successive administrations in London to plan for their policies to raise the population, we now have even bigger schools, squeezed onto tiny concrete sites, crammers in more than one sense.

It is another reason why we need to reform and embrace the free schools idea, as eminently Liberal – as long as they are knitted into local authorities alongside other schools.

Published on October 08, 2013 02:01

October 7, 2013

Gagging, the Koch brothers and 38 Degrees

I showed my face at two of the party conferences this year, and I won’t say which one I was at on this occasion. But I heard an MP refer to what he called “the curse of 38 Degrees”.

I showed my face at two of the party conferences this year, and I won’t say which one I was at on this occasion. But I heard an MP refer to what he called “the curse of 38 Degrees”.For the uninitiated, 38 Degrees is a powerful campaigning platform, on the American model, that allows people to sign up for campaigns and to send emails to recalcitrant MPs or anyone else.

It claims to have achieved some amazing things, including the provision of free school meals. Extraordinary – and all this time, I was under the naive impression that Nick Clegg and team had been working on how to make that happen. Apparently not.

I have taken part in some 38 Degrees campaigns. I knew the people who set it up. I even helped by advising them in its early stages.

But there clearly is a problem if MPs regard the process as a curse, when tens of thousands – maybe more – emails arrive in their in-boxes.

The problem isn’t around campaigning. It is the worry I have that none of my emails have ever been answered, and a nagging fear that they may actually be counter-productive or, more specifically, mistargeted.

On the occasions when I happen to know about the politics behind one of their campaigns, usually when it is directed at Lib Dem MPs or conference representatives, the political intelligence behind it is staggeringly inadequate. I don’t know about the other campaigns, but I worry about it.

I suppose it is my fault too. I know how few staff there are at the heart of the 38 Degrees machine. Perhaps I should have picked up the phone and advised them again, but there is something about their raucous tone that now prevents me.

But here is why I’m writing about it now. Because I have just received another message from 38 Degrees urging me to give them money to help them campaign against what they call the ‘Gagging Law’, actually the Transparency Bill now going through Parliament. Their description of the position is farcical.

And this is where my sympathy has finally expired, because it represents not just a misunderstanding – but a dangerous one, and one that will do nothing to prevent American-style oligarchs intervening in UK elections as they have in US ones.

As I write, the government has agreed – as they said they would – to make sure there is no misunderstanding, and to return the definition of ‘political activity’ to what it has been since 2000, when the Labour government first introduced the definition (but including rallies with an electoral purpose).

This is how John Thurso put the case, given that the changes he asked for have now been agreed:

"First the government has agreed to retain the existing definition of what non-party campaigning actually is: that is, activity that can “reasonably be regarded as intended to promote or procure the electoral success” of a party or candidate. Secondly, they have reverted to an existing definition of what constitutes 'election material', on which there is long established Electoral Commission guidance. These are crucial concessions, since those definitions have been in play since 2000, and no charity or non-party campaigner has ever claimed they were 'gagged' as a result."

Most charities operate under regulations from the Charity Commission which prevent them from getting involved in elections, and always have done, and it never stopped them from campaigning on the issues they care about whenever they need to. Nor should it.

I've got to be fair here. 38 Degrees have made the running, but they are backed by charities like NCVO and others. I've read their briefings and I don't understand how using the existing definition will make the law any more ambiguous, but I do accept there is some existing ambiguity which this bill doesn't clear up.

So you might reasonably ask why the UK should have legislation about electoral activity by non-candidates at all. The answer is summed up in one word: Koch.

The reason why this is so important is because of the Koch Brothers and their activities funding ultra-conservative election support in the USA, and those like them.

They set up lobby groups and non-profits to intervene, most of them well below the radar – but tax returns show that they spent $230 million in local interventions in the USA in the year before the last presidential election, and that was just through one of their organisations.

Look at the government shut-down, the blinkered oppositionism that has degraded American politics at federal level. That isn’t just about the Koch brothers, but we don’t want it here – we don’t want an open door to every oligarch who thinks they can intervene in our elections.

But 38 Degrees appears not to be bothered about that, as if somehow – if Koch UK was to land here – someone would rush in a law to prevent them. Some hope.

I’m not saying that they are somehow in league with Koch-style conservatism. That would be stupid. But they are being unbelievably naive – or they listened to the wrong people. Or something.

I know the bill doesn’t go far enough to rein in the lobbyists. But the last thing we need in this country is shadowy Koch-like figures among the ultra-rich intervening in constituencies for elections and using their considerable wealth to do so.

Why doesn’t 38 Degrees? And why don’t they see that, if they allow themselves to become so politically partisan - as they are doing - they are more easily dismissed as a ‘curse’ and their power, such as it is, will slip through their fingers?

Which is a pity, because it is a good idea - or it ought to be.

Published on October 07, 2013 02:15

October 6, 2013

How language changes - from splitting to spitting

It is now 99 years and about three weeks since my great-grandfather was killed, leading his regiment into action at the Battle of the Aisne in 1914. I'm not sure why I think of him particularly on these occasions, but I do.

It is now 99 years and about three weeks since my great-grandfather was killed, leading his regiment into action at the Battle of the Aisne in 1914. I'm not sure why I think of him particularly on these occasions, but I do.This is what I ask myself. If he rose from the dead, from the village churchyard where he now lies, and popped back to London - would he be able to understand our newspapers?

If we found ourselves in London in September 1914, we would undoubtedly be able to understand his newspapers, but what about the other way around?

I don't mean words like 'tweet' or 'online'. They would have befuddled us even twenty years ago, but the way that language has changed, and the kind of shorthand language invented by the Daily Mirror under the future Lib Dem peer, Hugh Cudlipp.

And English usage changes surprisingly fast. And I am in danger here of turning this blog into a middle-aged rant about sloppy English. I have reached a dangerous age, and it is true that I notice shifts like 'taken off' rather than 'taken from'.

But the reason for writing this post is my surprise that the phrase 'splitting image' has now completely disappeared, to be replaced by 'spitting image'.

I've noticed it for some time, but it became kind of official in my mind at least this week reading two edited and proof-read document - including a novel by Kate Mosse - where it was clearly 'spitting image'.

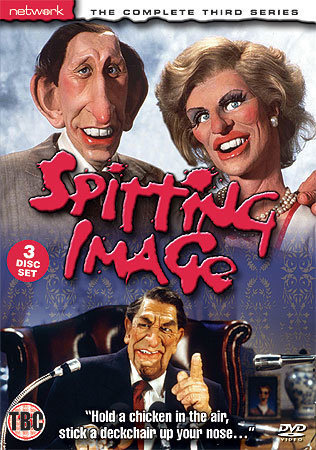

Do I mind this? Well, I don't think I have really any grounds for complaining about the way the spoken language changes, but I do complain when it is changed on the basis of a TV satirical programme using puppets, which ran on ITV from 1984 to 1996, with the name Spitting Image (a pun, geddit?). Especially as the puppets by Luck and Flaw nearly torpedoed the career of David Steel.

Steel went on to greater things, people seem to have forgotten the series - 1996 was 17 years ago after all - but it does seem to have shifted the language.

Every time I hear the shift, it irritates me. But it just shows how wrong you can be, because closer research reveals that actually the older version is 'spitting' after all.

What does that prove? I don't know. But here is one of their most spitting sketches, after Margaret Thatcher's overwhelming election victory of 1987. Watch out for Ted Heath putting his head in his hand.

Published on October 06, 2013 06:25

October 4, 2013

Energy giants, Liberalism and anti-trust

The headlines of national papers are very rarely the same, even if they are covering the same story. But on Wednesday, the

Times

and the Daily Telegraph both came up with the same one: 'Profit is not a dirty word, says Cameron'.

The headlines of national papers are very rarely the same, even if they are covering the same story. But on Wednesday, the

Times

and the Daily Telegraph both came up with the same one: 'Profit is not a dirty word, says Cameron'.This may be the sign of a similarly abject relationship to the press office at No 10. But both papers saw this phrase as the key element of David Cameron’s speech to his own conference.

By implication, we were supposed to see this as a riposte to Ed Miliband's attack on the energy providers. It also provides a glimpse of the next election – state control versus a defence of profit.

There is, in turn, an answer to Cameron: profit may not be a dirty word, but profiteering is. Can he tell the difference?

This is important because it reveals just how impoverished this debate is in the absence of a distinctive Liberal voice – and you partly have to blame the Lib Dems for this.

In the blue corner one party defends big business, and in the red corner they attack it. Where is the voice for small business which is not actually a subset of big business, but a distinct sector of its own? And a really crucial one, given that it is the SME sector that produces jobs and pays taxes.

I’m inclined to blame this damaging blind spot in the debate on the way that Liberalism has rolled over and accepted the slow shifting of language in economics away from its traditional position.

Liberals have allowed big business lobbies like the CBI to claim that they are speaking for all business.

They have allowed Labour and Conservative governments to gear regulation – banking, energy generation, public service commissioning – to suit the big corporates.

They have allowed free trade – originally a Liberal imperative to banish the economic shackles on the poor - to become a licence for the rich and powerful to ride roughshod over everyone else.

The result, it sees to me, is that costs are rising, and in every area. That is what happens when you become dependent on monopolies. It isn't just happening in energy either. Wherever you have monopolies or oligopolies of suppliers or providers, jobs shrink and prices rise.

The truth is, as I wrote in my book Broke , that costs are rising so fast that ordinary middle class lives are no longer quite affordable – nor for anyone poorer. Because the economy is increasingly geared to suit the needs of the mega-rich. Recovery won't change that, and the sooner we face that the sooner we can act.

Is there anything we can do about it? Well, I think there is. It means re-dedicating the forces of Liberalism to their original economic policy: breaking up monopolies.

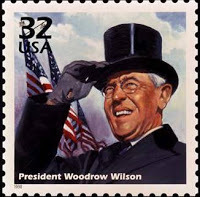

So I’m grateful to Tony Greenham for sending me this by the American Liberal Woodrow Wilson in 1913. This is how he put it:

"If monopoly persists, monopoly will always sit at the helm of the government. I do not expect to see monopoly restrain itself. If there are men in this country big enough to own the government of the United States, they are going to own it; what we have to determine now is whether we are big enough, whether we are men enough, whether we are free enough, to take possession again of the government which is our own...

"No country can afford to have its prosperity originated by a small controlling class. The treasury of America does not lie in the brains of the small body of men now in control of the great enterprises… It depends upon the inventions of unknown men, upon the originations of unknown men, upon the ambitions of unknown men. Every country is renewed out of the ranks of the unknown, not out of the ranks of the already famous and powerful in control."

So that is the way forward. Major anti-trust action, in energy, in the grocery market, in the online world, in pharmaceuticals and foods - not because they have necessarily broken the law, but because we need instead the inventions and ambitions of unknown men and women.

Published on October 04, 2013 05:09

October 3, 2013

Tutoring for two-year-olds?

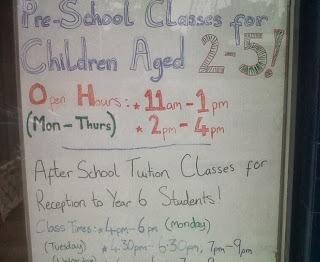

I came across this in a shop window near where I live (Crystal Palace) - in fact it is the first tutors that I've seen round here with a shop front, and it is filled with symbols of reliable-looking old-fashioned education, with sums on blackboards. A fascinating development.

I came across this in a shop window near where I live (Crystal Palace) - in fact it is the first tutors that I've seen round here with a shop front, and it is filled with symbols of reliable-looking old-fashioned education, with sums on blackboards. A fascinating development.This is the stuff of my time of life. The panic is beginning to grow in the breasts of people like me round here, with children aged nine, about what we are going to do about secondary schooling.

Every place is hard fought. A carpet millionaire has taken control of most of the nearby secondaries (from Peckham to Croydon), which seriously reduces our choices. And for those who really want to compete, well, the sky is the limit - but most of us don't, if we can possibly help it...

Still, I know of parents who have had tutors since the age of five or six, and are putting their children in for the great Rat Race - entrance exams for the super-selective grammar schools, every weekend, around the M25.

There is a kind of tutorial arms race going on. If your neighbours are employing tutors from the age of five, then maybe you have to - are your children going to be left behind? Of course, in those circumstances, those who can't afford tutors lose out. And so do the poor forcefed children, of course.

The Kent grammar school test is to be tweaked so that it can't be tutored, which is - as most people know - quite impossible.

As I took this photograph, someone came up behind me and said: "She's very good, you know." It was a kind of freemason's handshake, for those of us in the grip of the Great Secondary School Panic - a word in the ear, secretive, knowing. But then, this is the first hint I have ever seen that the tutoring arms race is now affecting the lives of those aged two.

I have tried to pinpoint the source of the panic in my book Broke: Who Killed the Middle Classes, so I don't want to go into this now. But part of it is undoubtedly the failure of successive governments to provide a major chunk of the middle classes with the kind of secondary schools they want - human-scale, friendly, inspiring, creative, nurturing...

And all they get to help them is school league tables, and I can't be the only one to be very dubious when confronted with the words 'outstanding'. I know the way targets work.

So I was fascinated to see emerging at the same time a project for a new Crystal Palace Primary School, which lists its priorities as developing the following character traits:

Curiosity

Determination

Enthusiasm

Gratitude

Optimism

Self-control

Social intelligence

I know that the free school programme has been flawed by the Department for Education's centralising grip, but the idea that people can be supported to set up their own schools - with safeguards of course - is a life-enhancing business, and goes with the grain of people's energies.

Yes, they should be be brought under the auspices of local authorities, but at least people are able to provide themselves with the kind of schools they want in the great black hole of south London.

Otherwise we may go our whole lives before the local authorities or Whitehall provide us with a school dedicated to instilling gratitude and optimism, rather than the Gradgrindian business of tutoring kids into an early aduthood.

Why can't we have the choice of a secondary school dedicated to optimism and gratitude? Oh yes, I forgot, because the carpet millionaire is establishing his grip on the local secondary schools and he gets what he wants.

Published on October 03, 2013 02:11

October 2, 2013

The truth about authenticity

On one of the hottest afternoons of the summer, the comedy writer Jane Bussmann came down to the allotments that encircle my home in Crystal Palace to talk about authenticity. The resulting radio programme struggles with the idea and it is rather good.

On one of the hottest afternoons of the summer, the comedy writer Jane Bussmann came down to the allotments that encircle my home in Crystal Palace to talk about authenticity. The resulting radio programme struggles with the idea and it is rather good.My only mild complaint is that the way it was cut made it sound as if the Canadian writer Andrew Potter was calling me a purveyor of "dopey nostalgia".

But then again, maybe he was.

Because actually, the authenticity debate - if there is one - is not really about a face-off between nostalgic romantics and hard-headed, world-weary post-modernists. It is about the nature of humanity, and whether people need human contact. whether they are suited for living permanently in a virtual world - or even an entirely ersatz one. And it is about the truth.

My position is that people need the human element very much, and will fight to preserve the link to that - or at least the option of it - very hard indeed, Not everyone, but enough people.

So Andrew Potter rather misses the point. So does the Harvard University Press's contribution to the debate by James Gilmore and Joseph Pine. Of course authenticity isn't an absolute. We would be pretty suspicious of anything claiming to be completely authentic - it doesn't work for such a contradictory, mutli-faceted concept.

My own book Authenticity: Brands, Fakes, Spin and the Lust for Real Life came before either of them, and might sound a little starry-eyed by comparison - but actually I think it still stands.

I also think the debate is kind of going my way, I've spent the decade since the book came out pouring scorn on the branding industry, which seems to me just to be a fancy name for image - and pouring particular scorn on the naive branding consultants who talk about people's emotional commitment to particular brands.

In fact, most people I know hate most of the brands they use. They feel manipulated by them.

What I tried to say back then in 2003 was that, to genuinely feel authentic, companies needed to allow more human contact - or, as Anita Roddick used to say, to show more sophisticated emotions than fear and greed.

And now here is one of the world's top brand consultants, Chris Malone, saying something along the same lines. I haven't read his book The Human Brand, because it isn't published yet, But I read what he said in this week's Fortune magazine:

"Every brand is human, and every human is a brand. how we damage our reputations and repair them is surprisingly similar. It's about warmth ... it's humanising."

Quite right. Authenticity isn't really about nostalgia at all, it's about how to humanise.

But then, if I was truly authentic, I ought to admit that the allotment Jane interviewed me on, and which they described as mine, is actually Sarah's. I just cut the grass. I'm not that authentic.

Published on October 02, 2013 00:58

October 1, 2013

The new conservative mood and why it matters

Have you noticed that the word 'modernisation' is slowly disappearing from the political lexicon. At roughly the same speed as Tony Blair.

Have you noticed that the word 'modernisation' is slowly disappearing from the political lexicon. At roughly the same speed as Tony Blair.Why? Because people don't believe it any more. It became a weasel word. If you heard any service was being 'modernised', it usually meant 'streamlined', which took the humanity and usually also the effectiveness out of it. Nobody, except maybe the dinosaurs at McKinsey, believe in that kind of modernisation any more.

The last thing anybody wants of any institution they use is that it should be 'modernised' in that sense. Why would you, when modernised has come to mean 'lobotomised'?

I thought of this as I read a fascinating article by John Harris in the Guardian, which describes the emerging new conservatism in the UK - and how far away it is from the conservatism practised by the current leaders of the Conservative Party.

The first thing we think of in these terms, because we are members of the metropolitan middle classes (speak for yourself! I am), is UKIP and the hatred of foreigners. But don't let's dismiss English conservatism so blithely.

Harris was talking about the growing sense in the nation that modernisation, globalisation and internationalisation, as practised by Blair and Osborne (can you see the difference between the two twins?), has not served us very well.

It is small C conservatism to regret the closing of your local pub or post office, to bemoan the destruction of traditional banks, the failure of lobotomised institutions.

It is small C conservatism to regret the privatisation of Royal Mail, one of the great institutions of state.

Nobody any more believes that this will improve the service, provide any sense of mutuality or leadership, or give any grounded sense of community. Not even the promoters of the privatisation plan can possibly believe that. But they believe somehow that it will be worth it because a new owner can raise the necessary capital to - no, don't say it - modernise.

That is not a conservative act. Not something that any middle English conservative, with a healthy sceptical view of political language, could possibly be thrilled about. This is how Harris puts it:

"But too many modern Tories' conservatism is dissonant, for some key reasons. First – and here, picture George Osborne, who is not actually a small-c conservative at all – most of them are brimming with neoliberal zeal, and for all their thin approximations of patriotism, have a tin ear for issues that go from politics and economics into questions of national identity, culture and people's feelings for where they live."

That is absolutely right, and it provides an opportunity for the opponents of the Conservative Party, which Miliband tried to fill a little last week with his Labour-style populism ("keep still and we'll give you money").

The great danger is that the Westminster elite will regard this quiet kind of conservatism as too dangerous, too backward-looking, even mildly racist - so that they don't hear it properly and miss its creative, localist power.

Or take the usual line of the Westminster bubble and shut it out completely, while the elite embrace our existing lobotomised institutions with new fervour. The danger then is that you push middle England straight into the waiting arms of Nigel Farage - or worse.

Published on October 01, 2013 01:35

September 30, 2013

Where Osborne is right - and where he 's horribly wrong

I warmed a little to George Osborne last year when I found myself in the same theatre, watching the musical of Swallows and Amazons. But I must admit, spending my breakfast listening to him this morning was a threat to my digestion - as the emotions veer between irritation and frustration and back again.

I warmed a little to George Osborne last year when I found myself in the same theatre, watching the musical of Swallows and Amazons. But I must admit, spending my breakfast listening to him this morning was a threat to my digestion - as the emotions veer between irritation and frustration and back again.There are two of his propositions which I believe are fundamentally right. That you should ask people to give something back in return for their benefits, and that you should not let people moulder their lives away on the dole - or its Labour equivalent, incapacity benefit.

The right to lead a useful life is an unacknowledged human right, but an important one, and paying people on the strict condition that they do nothing is a an equally unacknowledged horror.

But there are two big problems with the welfare announcement today, and they are both about the effectiveness or otherwise of public institutions.

The first is that, if we are really talking about a new effective system to help people into jobs, then the emphasis wouldn't be on the sanctions for people who refuse.

There do need to be sanctions, but - let's face it - this is the angle that the Conservatives appear to want to emphasise on the first day of their conference, as they look nervously over their right shoulder at UKIP.

It is no coincidence that the community service described by Osborne, and the community service served by people instead of prison, seem identical. It can't possibly be transformative if it is a punishment.

The second is that the institutions of welfare have been hollowed out over a generation, as I described in my book The Human Element . They are now one-dimensional, punitive, slightly brutal and wholly ineffective. Using them to drive a transformation in the lives of long-term jobless people is like swerving out onto the fast lane in your lawnmower

The reality of the hopeless institutions that Job Centres have become are in Harriet Sergeant's book Among the Hoods , where she describes their complete failure to help the Brixton gang members she befriended. It made her furious.

Oddly enough, I recently came across someone who had worked in the Brixton Job Centre in the 1980s. She managed to draw some satisfaction from the job by focussing on a few individuals she could help and battling the system until she found them a job.

This kind of humane, transformative behaviour is that much more difficult in our institutions after 13 years of New Labour 'reforms'. They will be completely impossible under the dysfunctional delivery system planned for what would otherwise be a transformative idea, the universal benefit..

No, let's imagine for a moment what kind of institution might turn Osbrne's announcement into something genuinely transformative:

A system that is really able to get to grips with the complex lives of individuals, on a coaching basis, and make something happen.A real choice of community activity, not just semi-slavery picking up litter.An opt-out for single parents with families, for whom there is far more important work

That kind of system would be more expensive to run, but then it might also have some impact - if that is genuinely what Osborne wants, rather than just headlines. But, otherwise, what's the point?

Published on September 30, 2013 03:15

September 29, 2013

How to save Greece from a debtors prison

When you worry a little about the results of your policies, it is a good time to stop and think.

When you worry a little about the results of your policies, it is a good time to stop and think.I don’t mean some of the less successful effects of the coalition, because those are not necessarily Lib Dem policies. They are compromises to achieve other reforms, as any coalition has to make.

I’m thinking of Greece. The people of Greece were sacrificed to save the euro, once a major Liberal contribution to economic policy; now rather an embarrassment.

The Greek debt is still ballooning as a proportion of GDP. The so-called Troika's rule over Greece, on behalf of the technocrats, has constantly failed in its predictions, yet it is the Greeks who suffer - as I may have mentioned before.

The problem wasn’t the bail-out, which had to happen. It was the major discouragement given to Greece by the European bankers when it came to getting any kind of democratic mandate. And it was what went with technocratic rule.

The Greek people are now held in the equivalent of a debtors’ prison, which will have potentially devastating consequences to come – and these may not be very far off after the news last week..

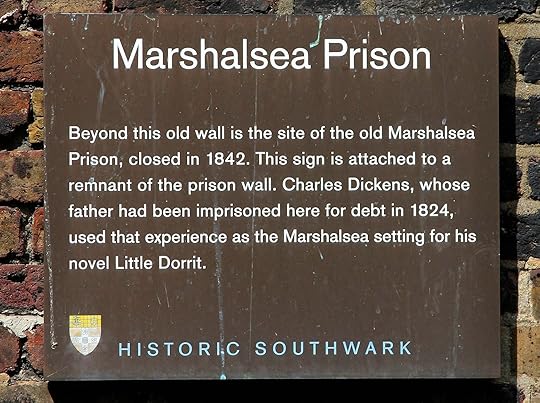

But the real problem is the same as every debtors’ prison – the Marshalsea in Little Dorrit was no different – that you can’t exactly trade your way out from inside it. Nor can the Greeks trade their way out from inside the cage constructed by the Troika.

Here is the question, and it needs answering: how does a nation find ways of keeping life going while the debts are paid?

And behind that lies another rather important question too: how does a disadvantaged region or city regenerate itself when the national interest rates are set to prevent inflation in the rich areas?

I think a potential answer is beginning to emerge.

Forget single currencies. Welcome to the age of multiple currencies, which can be used in countries like Greece while the euro debts are extracted. They can provide a life-giving liquidity, give advantages to un-used local resources, and encourage enterprise. Not instead of the national currency or euro, but alongside them.

Something along those lines is already emerging in Greece, just as they did in Argentina in similar circumstances a decade ago. But far too slowly.

But the only country in the world where financial regulators are actually enthusiastic about the idea is Brazil. Ironically, the community banks pioneered there have been using knowhow financed originally by the European Commission. Yet the idea seems a million miles from the current euro orthodoxy.

There is little evidence yet that complementary currencies are emerging on any kind of scale, but they are increasingly talked about. My colleague Susan Steed found this amazing graph which shows an extraordinary acceleration of interest in the idea (mentions in Google books). There is also a little blip during the Great Depression (Irving Fisher’s book Stamp Scrip, no doubt).

I think this is an idea whose time has come. It stands for diversity against uniformity and manages to combine a means for self-determination with a commitment to cross-border internationalism.

It does everything the euro claimed to do, in other words, without plunging the poor areas into poverty.

For that and many other reasons, I think Liberals need to embrace this idea. The euro project is dead: it represented a sort of economic naivety on the part of Liberal internationalists, who failed to bheed Keynes' warnings against internationalising money. But there is no reason why we have to go back to national currencies and central banks.

I’m speaking about this at a meeting on October 9 to celebrate the new edition of Stir magazine. Do come along and argue with me!

Published on September 29, 2013 03:53

David Boyle's Blog

- David Boyle's profile

- 53 followers

David Boyle isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.