David Boyle's Blog, page 66

October 30, 2013

When books disappear from libraries

Croydon's battered library system has not been exactly the envy of the world recently, closing six branch libraries and handing over the rest to be managed by John Laing Integrated Services, promising - you guessed it - investment in IT services.

Croydon's battered library system has not been exactly the envy of the world recently, closing six branch libraries and handing over the rest to be managed by John Laing Integrated Services, promising - you guessed it - investment in IT services.They finally took over three weeks ago, and just had time to put all the library staff in uniforms, before - hey presto! - they were bought by the service company Carillion.

Nobody seems to have informed the council of this, least of all Carillion, and there are now said to be 'discussions', which is only to be expected when you suddenly find your libraries are being run by a company you haven't actually chosen.

My family just spent the first day of the half-term wandering around library branches in search of a particular book (don't ask!). Their reaction, having eventually found the book in the central library was this:

Where on earth are all the books?

Thornton Heath Library has been recently redesigned at vast expense by architects FAT, but - as Sarah said when she arrived back - we've got more books in our house than they have.

I have noticed over the years that one of the first signs of a failing school is when the books start disappearing, usually replaced by gleaming computers - though there are precious few of these in the libraries either. It is a wholesale replacement of content with process, precisely the same disease which public services suffered from during the New Labour years.

So how are we to understand the news, revealed today by Apple chief executive Tim Cook, that sales of iPads to UK schools doubled in the last year (though Apple's profits are still falling)?

My nine-year-old has been remarking at his primary school about how there are now iPads everywhere, so something strange is going on.

So. Is this another example of the replacement of content with process, in a way that even McKinsey would approve of? Or is it an early warning sign that UK schools are going the same way as UK libraries - a hollowing out leading to a decline?

And before you accuse me of cynicism, ask yourself where the money is coming from. Was the Pupil Premium really intended to prop up Apple's profits?

Published on October 30, 2013 03:27

October 29, 2013

Deming, CQC and the new efficiency

Back in the 1940s, the great American theorist of 'total quality, W. Edwards

Deming warned that assembly lines, in themselves, were not efficient at all. We ought to listen to that, given that our public services are being re-designed by people who think that assembly lines are the apotheosis of efficiency.

Deming’s story is rather peculiar, because he found that his fellow Americans were not quite ready for this message, so he took his ideas to Japan after the Second World War, and was enormously influential.

Efficiency is all about getting things right first time, he said, because then you don’t have to do it again.

He was astonished at how much the American factory system wasted, in materials and time, just by failing to pay attention to quality. The result was the enormous sums of money were spent by organisations just to put right the mistakes they had made – and splitting up jobs means more mistakes.

Now Deming’s name is being gargled with at the moment by the influential NHS blogger Roy Lilley, as a way to explain how ineffective the CQC has been – in fact, about the whole business of inspection and how it has failed miserably to make hospitals safer.

It just so happens that I went to a fascinating conference yesterday, organised by Deming’s vicar on earth, the systems thinker John Seddon.

Seddon himself was stuck on a train thanks to the storm, but I did have the chance to hear from four amazing women from Monmouthshire County Council who are in the process of transforming social care assessments.

So much so that they seem to have provided a kind of template for the new flexible assessment system that the Welsh government are introducing in January.

Monmouthshire has developed a fascinating combination of systems thinking, Australian local area co-ordination. They call the result FISH (find individual solutions here).

It is about getting interventions right first time, the very essence of what Deming suggested.

What really excited me is the way they have turned the conventional call centre model on its head. No more phoning a call centre that will record details and hand over them over to back office experts, who will then set appointments and so on and so on, all before anything much happens.

Now people call up and speak direct to an expert, who can if at all possible sort things out there and then.

Some cases will need more complex assessments and work, but – by sorting out problems early and informally where possible – they have reduced the number of these by half.

There is a great deal more to say about all of this (which I won’t) but it does drive a coach and horses through the conventional, and evidence-free, government preference for shared back office services.

Seddon has been a lone voice describing how the front office/back office division has been increasing a sort of fake demand, at great expense. But there are two problems at the moment that have been bothering me.

First, how do you persuade Westminster and Whitehall that the whole caboodle of IT systems, back office divisions, and outcome-based management is actually undermining the effectiveness of services and making them more expensive?

Second, how do innovators like Monmouthshire confront the useless requirements of the existing regulatory system? Neither there, nor anywhere else, has the battle been won. In fact, it has hardly been joined yet.

Third, why on earth is Seddon describing his seminar roadshow as ‘Kittens are evil’? I know what it means of course, but it seems to imply a modesty and self-deprecation that his ideas don’t deserve.

Too many negatives, I say. We need kittens. Welcome to the new kittens, I say.

Published on October 29, 2013 07:11

October 28, 2013

Is Amazon included in the growth figures?

George Osborne is looking pleased with himself. The coalition believes it has been vindicated on the economy. Growth is now the fastest since - well only 2010, actually.

One of the casualties of the last few years, with Osborne anxiously scanning the horizon for the rescue he felt had to arrive, is a saner approach to the word 'growth'. Most radicals since Bobby Kennedy have regarded the unadorned growth figures as wholly irrelevant - and sometimes downright corrosive - to prosperity.

I think they are right, personally. If you can increase growth by spilling oil in the North Sea, by speeding up deaths on the roads or by going around blowing up the house price bubble, then it isn't a terribly meaningful figure.

I would leave that on one side, were it not for the handful of continuing mysteries about the growth figures.

Mystery 1: If growth is rising so fast, why are we not reducing the deficit this year?

Mystery 2: How much of it is actually just the ludicrous increase in house prices that is going on in London and the south east - fake prosperity if ever there was any?

Mystery 3: Given the continuing bubble in house prices (average home up £50,000 in value in a month), why is growth not actually much higher?

I ask the last of these because that key question, and one not being answered by any of the commentators now, is how much of the economy has been taken offshore and therefore not counted in the growth figures? Because that might explain something about why, despite sticking to spending cuts, the deficit is still not coming down.

So here are the questions to ask any official statisticians you happen to find standing next to you.

What percentage of the UK economy is now operating offshore?

What tax would the offshore sector be paying if they were not being allowed an unfair advantage over businesses that are still operating in the light?

Is Amazon's considerable business, including the wreckage of the UK book trade, counted in UK growth figures given that it is said to be operating out of Luxembourg?

In other words, can we rely on any of these figures as being anything like accurate?

Published on October 28, 2013 07:15

October 27, 2013

The radicalism of model railways

Maybe it is my age, but I find myself increasingly in the middle of other worlds - little universes complete in themselves. The fine art world/economics world (strange that one), and yesterday the model railway world.

Maybe it is my age, but I find myself increasingly in the middle of other worlds - little universes complete in themselves. The fine art world/economics world (strange that one), and yesterday the model railway world.My two boys are fascinated by model railways. I don't think I had been to any kind of display since I last left the annual Model Engineer exhibition in Victoria around 1971. Things have moved on somewhat, as I discovered at the amazing show put on by the Beckenham and District Model Railway Society.

These were the most extraordinary miniature worlds, often set earlier in the twentieth century, often with their own timetables. Hythe Station as it was before closing in 1951 (see picture of model above), docks, fishing ports, piles of coal, tiny wheelbarrows - not so much an evocation of a lost, perfect world, but a loving recreation of lost industrial landscapes.

And if you really want to be staggered, have a look at what this man built in the foundations of his house.

In the years between 1971 and 1979, I moved from models to politics (and one or two other things), and - since I can't get the models I saw yesterday out of my head - I have been wondering about their political significance.

One of the magazines I read as a student was called Vole. It has long since disappeared, merged like everything else probably with Resurgence, the great green survivor.

But Vole pulled off a trick which has never quite been managed since. It combined a green and local radicalism with a bit of humour and some apparently nostalgic articles about railways. I found it so influential that I find myself almost stuck in the same track now.

Because there is a hidden radicalism about railway nostalgia. It isn't for the days of state control - the people who rescued the Tallylyn Railway in 1951 were very conservative in that respect. All I can say is what it means for me.

1. The pre-Beeching railways are a kind of symbol of an alternative method of transport to unlimited motoring, a glimpse of a possible future not taken.

2. Those carefully nurtured flowerbeds on the platforms of the 1950s are a sign of what genuine localism could make possible, when the centralisation of corporate control these days means broken tarmac, and leaving the heaters on all summer.

3. The continuing success of preserved railway lines all over the country are an example of just what mutual communities of interest can achieve if left to themselves.

For me, the models I saw yesterday were all little utopias, miniature worlds with muck heaps and coal yards, where things broke down, but where attention to detail and a carefully manoeuvred screwdriver could sort things out. They are supported by a growing pan-European cottage industry of small retailers and manufacturers, making equipment to the various scales.

I have met the members of my local model railway club when I visited them in the capacious headquarters in the basement of a largely empty office block. I was staggered to find that most of them worked on the railways as well in the daytime. You can hardly call the modelling bug escapism.

It certainly tends to be nostalgic, but in a creative way. These models are so beautiful and intense that they can take the breath away. No, I'm inclined to think that this is more confirmation that small is still beautiful, inspiring and radical, and the triumph of human ingenuity over mass consumption.

Published on October 27, 2013 15:58

October 26, 2013

The strange story of the sinking of the Gulcemal

I have a feeling that the centenary events for the First World War are going to be a shock for some of us.

I have a feeling that the centenary events for the First World War are going to be a shock for some of us.I am old enough to remember the Old Contemptibles, those survivors of the British Expeditionary Force in 1914, marching along Whitehall on Remembrance Day, and they have all gone now. What next year will mark is the shift from remembrance to history - and to military historians in particular.

That means engaging with the former enemies properly, and on an equal basis. I still hear bizarre stories from military conferences about how the German or Turkish points of view are completely sidelined by old buffers, and embarrassingly so if there are German or Turkish experts present.

I was thinking about this because of the strange story, which I have just written about in the e-magazine Fighting Times , about the sinking of the former White Star liner Gulcemal (ex-Germanic) in the Sea of Marmora in 1915 (briefly on sale for 99p). The story is strange because - the gulf between British and Turkish military historians is still so wide - that it only just came to light, nearly a century later.

It happened because of a question whether the liner, once holder of the Blue Riband of the Atlantic, then carrying 6,000 Turkish reinforcements bound for Gallipoli, had actually sunk after its brush with the submarine E14. Night fell, the British never saw what happened and, for some reason, British officials never thought of asking the Turks.

Consequently, the British Admiralty paid out a record sum in 'prize money' for the sinking in 1919, just as the very same ship was being chartered by the British Military Mission in Berlin to take Russian prisoners of war home from Hamburg.

A typically bureaucratic mistake, and the article explains why it was made. You can hardly blame them, but why did nobody ask?

Published on October 26, 2013 03:37

October 25, 2013

Three urgent questions about bugging foreign leaders

"I would no more trust such MPs with my liberties than send them out to buy a pizza," said Simon Jenkins on the front page of the Guardian this morning.

He was comparing the political action, from both Democrats and Republicans in the USA, to control the business of total surveillance and the abject way that MPs over here stay silent in the face of their own failures to oversee the same process here.

The recent revelations that the USA has been bugging Angela Merkel ramps up the pressure. It is a serious question - not that nations haven't always spied on each other's leaders, because they have, but because this kind of activity needs to be brought within the rule of law.

If if isn't, experience shows that surveillance loses focus. Politicians and security mandarins are famously unable to distinguish between national security and their own dignity, and that has serious consequences for their own effectiveness.

The bugging of Angela Merkel's phone was so lazily achieved, and so pointlessly ordered, that these are becoming vital questions - and there are other urgent questions for us here too.

First one: are David Cameron's private conversations being listened to by the NSA, and reported to American security?

The second one is this: if not, what is the quid pro quo? Is there some agreement to share in the contents of conversations by Merkel and Hollande?

These are very serious questions. It does not threaten national security to ask them, though it will be embarrassing for politicians and officials - but, as I say, these things are very different.

Here is the third question: why are MPs over here not asking these questions? Why is the Labour Party not holding the government to account? Why is Miliband silent?

He was comparing the political action, from both Democrats and Republicans in the USA, to control the business of total surveillance and the abject way that MPs over here stay silent in the face of their own failures to oversee the same process here.

The recent revelations that the USA has been bugging Angela Merkel ramps up the pressure. It is a serious question - not that nations haven't always spied on each other's leaders, because they have, but because this kind of activity needs to be brought within the rule of law.

If if isn't, experience shows that surveillance loses focus. Politicians and security mandarins are famously unable to distinguish between national security and their own dignity, and that has serious consequences for their own effectiveness.

The bugging of Angela Merkel's phone was so lazily achieved, and so pointlessly ordered, that these are becoming vital questions - and there are other urgent questions for us here too.

First one: are David Cameron's private conversations being listened to by the NSA, and reported to American security?

The second one is this: if not, what is the quid pro quo? Is there some agreement to share in the contents of conversations by Merkel and Hollande?

These are very serious questions. It does not threaten national security to ask them, though it will be embarrassing for politicians and officials - but, as I say, these things are very different.

Here is the third question: why are MPs over here not asking these questions? Why is the Labour Party not holding the government to account? Why is Miliband silent?

Published on October 25, 2013 06:16

October 23, 2013

John Major and the price of everyday life

The social democratic think tank the Policy Network has invited me, along with thousands of others I expect, to a seminar on what they call the Insider-Outsider Dilemma.

The social democratic think tank the Policy Network has invited me, along with thousands of others I expect, to a seminar on what they call the Insider-Outsider Dilemma.This is how it goes. Parties of the left are unsure whether they should appeal to people excluded from mainstream markets (claimants, outsiders) or to the mainstream people who get by (middle classes, insiders).

If they go for the outsiders they can, at least, be clear about where they stand - but they risk alienating everyone else.

If they go for the insiders, they have a potential winning constituency but risk losing their purpose and core beliefs, which has other downsides - like losing voters to the left.

Polly Toynbee is a speaker in the seminar, which kind of gives the game away a bit. I have to confess my own bias about this; that this is an irritatingly Fabian approach to the problem, which assumes that the purpose of the left is to defend the social democratic consensus exactly as it was circa 1970. But, in their defence, that's not how they put it.

So perhaps I'm being terribly unfair. But it seems to miss entirely the way the economy has been moving over the past generation, ever so slowly but inexorably.

The point is this. It is increasingly difficult for mainstream people in work, including ever larger chunks of the middle classes, to get by without support from the government.

They need Help to Buy because the housing market is geared for the interests and prices of foreign investors. They need housing benefit even though both partners are working. They need Funding for Lending, which still doesn't work, if they want to borrow money from a bank to start or expand a business. They get by on child tax credits or more old-fashioned kinds of credit via re-mortgaging or credit cards. Their pensions, the mainstay of the middle classes, have been corroded by the kind of investment managers that Prince Charles lambasted last week.

Increasingly, ordinary people can't afford the vast rents and mortgages in southern England, and the government moves to subsidise - brushing the basic problem under the carpet, shelling out in housing benefit for working families because rents are shooting up..

What is happening is that everything we thought of as the economy is beginning to move to the margins, often subsidised by taxpayers.

Energy prices rise as the big utilities extract the benefits of monopoly (and so do the French and the Chinese), and because successive governments wasted the returns from North Sea Oil.

Public services become increasingly unaffordable as the PFI contractors extract the benefits of successive governments determination - at whatever cost - to take their debts off their balance sheet.

Other monopolies make best use of the UK's bizarrely forgiving corporate tax regime to move whole sectors offshore (Amazon has done so for the book trade).

No one party has been responsible for the sheer unaffordability of mainstream life, so it isn't remarked on.

The Resolution Foundation has been tracking this trend as it spreads up through people and families on middle incomes - but it increasingly now afflicts families beyond Resolution's remit.

It is this peculiar and largely unremarked process that was at the heart of my book Broke: Who Killed the Middle Classes? (which also suggests some ways out).

And here is the answer to the Insider-Outsider Dilemma. There need be no real dilemma, because the insiders are increasingly outside the economy too.

In fact, the insider-outsider dilemma ought increasingly to afflict parties of the right, as they struggle to find anyone who benefits much from the status quo.

This is also the background to what looked like a critically important intervention by John Major yesterday on energy bills.

Major may have been the great privatising prime minister, but he is also a bellwether for middle England. What makes his intervention so important is that he can see, just in the energy market, how people in mainstream society are beginning to need subsidy - and he doesn't see why the energy companies shouldn't pay for it.

That is symptom rather than cause. No political party has dared yet articulate the cause. It is time we started to knit together the bits of the picture so that they might have some chance of doing so.

Published on October 23, 2013 02:40

October 22, 2013

Energy, free schools and the search for flexibility

I first got interested in energy policy when I was at university at the end of the 1970s. It is strange to remember quite what we were up against in those days: a strange semi-soviet state organisation, the Central Electricity Generating Board, presided over by a Gromyko-like figure called Lord Marshall.

I first got interested in energy policy when I was at university at the end of the 1970s. It is strange to remember quite what we were up against in those days: a strange semi-soviet state organisation, the Central Electricity Generating Board, presided over by a Gromyko-like figure called Lord Marshall.It poured money into nuclear energy (with little to show for it). It throttled research into renewables, and miserably failed to solve the problem of nuclear waste. Oh yes, and there was also Tony Benn's nuclear police force.

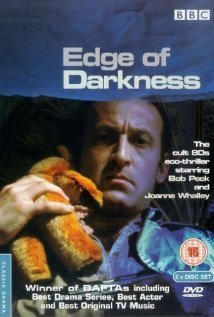

Ah, yes, it all comes flooding back. The Edge of Darkness and all that (I think it should be on TV again).

We may not want a profit-making oligopoly running our energy, paying vast salaries to managers, but the last thing we want is the CEGB back again. What we desperately need is some kind of system that is flexible and responsive, which encourages people and communities to invest in generating their own energy.

I thought of this as I received a number of emails forwarded from the ubiquitous internet campaigners 38 Degrees, urging me to sign a petition on their site calling for energy to be re-nationalised. An amazing 14,000 people seem to have signed it. Clearly they don't remember the CEGB.

But then, this isn't a blog post about energy - it is a post about flexibility.

I got interested in how we might make our public services flexible enough to suit a very wide variety of needs when I was looking at choice for the Barriers to Choice Review.

The mechanisms that allow for choice in health and education, for example, really ought to make the systems more flexible. In practice, thanks to the way these systems were designed under Tony Blair - largely by economists - they can often make the services more inflexible instead. You then get formal, approved 'choices', but they all look much the same.

Nick Clegg's intervention on free schools seems to have ruffled some feathers, but a close examination of what he said seems to reveal - well, what? It is hard to read, but I'm kind of imagining he is making a similar point: we need basic standards for all schools, but more flexibility everywhere, not just for the favoured few.

Yes, the point he makes most strongly appears at first to be the opposite of this - that schools should only employ qualified teachers and that the national curriculum should apply. Then he says this:

"I'm proud of our work over the last three years to increase school autonomy, which, in government with the Conservatives, has been through the academies programme."

So why the fury from backbench Conservatives? Odd and, yes I have to admit, I don't agree about the qualified teachers. There may well be people out there who have life experience that would be valuable for schools. I wouldn't want to force everyone through teacher training.

Flexibility means going with local energy, and the energy of local people, rather than clamping down on it - whether that is unqualified people who have something to offer or the energy of local parents shaping a new school.

But where Nick Clegg was absolutely right is that the artificial division emerging between local authority schools, forced into rigid adherence to a national curriculum that doesn't apply to free schools and academies, is divisive and quite unnecessary.

We have learned from the kind of flexibility that the free schools have provided. That flexibility should now be extended to all schools. A very basic curriculum should apply to all schools too. Flexibility works, as long as people are held to account for the education their schools deliver.

And actually, in the long run, the direct connection between the academies and free schools to central government is a threat to this flexibility. They need to come under the auspices of co-ordinating local authorities in the same way, but with the flexibilities guaranteed.

Public services are not very flexible these days. They are more expensive and less effective as a result. But the last thing they need, and the last thing the energy market needs, is to swap the current mildly inflexible system for something completely turgid.

Therein lies the edge of darkness.

Published on October 22, 2013 04:19

October 21, 2013

Read my lips. No nuclear subsidies

Picture the scene. There we were, May 2010, exhausted, flushed, staggered, the Lib Dems taking part in the special conference at the National Exhibition Centre in Birmingham, to agree the coalition on the terms offered.

I was so staggered myself that I lost my diary (email me if anyone found it, I'd like to know what I was supposed to be doing for the rest of 2010).

At some point during the business of wandering round the fake corridors and escalators that bedevil conference centres of all kinds, I was hailed by Chris Huhne, the new Secretary of State with responsibility for delivering a greener energy policy.

I turned around and saw him at the top of the escalator, and remember thinking that I had never seen anyone look so exhilarated - as well he might, joining the Liberal Democrats decades before and finding himself in the cabinet. He was also, as we know now, in love.

I knew, of course, as we all did, that the chances of him delivering a genuinely green energy policy were remote. The political difficulties were immense, and certainly haven't reduced since. But I believed that he would be able to shift the wasteful, creaking old monster we know as UK Energy Policy in a greener direction - and that it would help re-balance the economy too.

There was a problem: he would clearly not be able to adopt a strict Lib Dem position on nuclear energy, but there would be conditions, as Chris Huhne spelled out from the rostrum.

I was probably more reassured than I was by any other remark - in fact it is the only sentence I remember from the whole day. This was the moment when he borrowed from George Bush Sr: "Read my lips," he said. "No nuclear subsidies."

I am sure that, at the time, he believed this. This is not an attack on his honesty, or an attack on Huhne at all - he is a huge loss to frontline politics.

But what are we to make of this morning's announcement of the deal with French company EDF, giving it a guaranteed price for electricity for 35 years amounting to a subsidy of somewhere around £1 billion a year (if electricity prices stay the same)?

Everyone knows that nuclear energy would be impossible without some kind of guarantee, and I seriously doubt whether EDF will ever make money even on that one. But that was not what we promised ourselves - let alone anyone else.

The party's embarrassing new policy repeats the same glib non-position - no nuclear subsidies, when that is precisely what is now being agreed.

Don't get me wrong. I support the coalition. I think Ed Davey is doing an impressive job in the increasingly embattled position as Secretary of State for Energy and Climate Change. I know how hard he has worked for a better deal on the new Hinkley Point nuclear power station.

I also know that everything now depends politically on denying that the fixed price guarantee is a subsidy. It is - and it isn't the only one: there is another subsidy in the insurance against nuclear accidents and in the storage of nuclear waste for some centuries to come. There are also loan guarantees to EDF.

It also needs to get through rapidly-changing EU regulations about energy subsidies, currently being taken apart by the Germans.

But it is the opportunity cost which enrages me. Billion-pound-a-year subsidies are not that common, and imagine what we could do to the UK economy if that money - about £37.5 billion over 35 years - went into making the UK the manufacturing centre for renewable energy for the world.

And imagine, if we did so, how much lower our power bills would be at the end of it.

I was so staggered myself that I lost my diary (email me if anyone found it, I'd like to know what I was supposed to be doing for the rest of 2010).

At some point during the business of wandering round the fake corridors and escalators that bedevil conference centres of all kinds, I was hailed by Chris Huhne, the new Secretary of State with responsibility for delivering a greener energy policy.

I turned around and saw him at the top of the escalator, and remember thinking that I had never seen anyone look so exhilarated - as well he might, joining the Liberal Democrats decades before and finding himself in the cabinet. He was also, as we know now, in love.

I knew, of course, as we all did, that the chances of him delivering a genuinely green energy policy were remote. The political difficulties were immense, and certainly haven't reduced since. But I believed that he would be able to shift the wasteful, creaking old monster we know as UK Energy Policy in a greener direction - and that it would help re-balance the economy too.

There was a problem: he would clearly not be able to adopt a strict Lib Dem position on nuclear energy, but there would be conditions, as Chris Huhne spelled out from the rostrum.

I was probably more reassured than I was by any other remark - in fact it is the only sentence I remember from the whole day. This was the moment when he borrowed from George Bush Sr: "Read my lips," he said. "No nuclear subsidies."

I am sure that, at the time, he believed this. This is not an attack on his honesty, or an attack on Huhne at all - he is a huge loss to frontline politics.

But what are we to make of this morning's announcement of the deal with French company EDF, giving it a guaranteed price for electricity for 35 years amounting to a subsidy of somewhere around £1 billion a year (if electricity prices stay the same)?

Everyone knows that nuclear energy would be impossible without some kind of guarantee, and I seriously doubt whether EDF will ever make money even on that one. But that was not what we promised ourselves - let alone anyone else.

The party's embarrassing new policy repeats the same glib non-position - no nuclear subsidies, when that is precisely what is now being agreed.

Don't get me wrong. I support the coalition. I think Ed Davey is doing an impressive job in the increasingly embattled position as Secretary of State for Energy and Climate Change. I know how hard he has worked for a better deal on the new Hinkley Point nuclear power station.

I also know that everything now depends politically on denying that the fixed price guarantee is a subsidy. It is - and it isn't the only one: there is another subsidy in the insurance against nuclear accidents and in the storage of nuclear waste for some centuries to come. There are also loan guarantees to EDF.

It also needs to get through rapidly-changing EU regulations about energy subsidies, currently being taken apart by the Germans.

But it is the opportunity cost which enrages me. Billion-pound-a-year subsidies are not that common, and imagine what we could do to the UK economy if that money - about £37.5 billion over 35 years - went into making the UK the manufacturing centre for renewable energy for the world.

And imagine, if we did so, how much lower our power bills would be at the end of it.

Published on October 21, 2013 02:59

October 20, 2013

Why Ocado needs to take on Amazon

I must admit, I am caught on the horns of a dilemma. I've been writing this blog nearly every day since February, since completing the Barriers to Choice Review for the government.

I must admit, I am caught on the horns of a dilemma. I've been writing this blog nearly every day since February, since completing the Barriers to Choice Review for the government. I am in favour of choice. It is a difficult word; I've sat in meetings with hospital doctors when they all folded their arms and stared at me, just because the conversation was supposed to be about choice. But, for all the ambiguities and difficulties, there is something a good deal worse than choice - no choice.

But what I see around me is often the signs of shrinking choices. Most of the secondary schools in the area I live in have been taken over by a carpet millionaire. Where is the choice there?

I would like to move my business account to a local bank which will invest my savings in local enterprise. There isn't one. Where is the choice there?

And I would like to use this blog to link to my books so that people can buy them somewhere else apart from a monopolistic website like Amazon. Where is the choice there?

There is my dilemma. I write this blog partly to remind people occasionally that I've written some rather readable books which they have almost certainly failed to read yet. There are other websites to rival Amazon, but they don't really fit the bill.

There is Hive, which is brilliant, but they charge postage on orders under £15 (I use them to buy books, but it is more difficult selling books that way). There is the Book Depository, but the regulators - in their wisdom - allowed Amazon to take them over. There is Waterstone's, but they don't sell my ebooks.

It is a sure sign of monopoly when you don't actually have any choice. I have a choice when it comes to buying, and I certainly exercise it, but Amazon is now so powerful that it seems pointless to sell books by linking to anywhere else.

In any case, this isn't just about books. Amazon already operate an unfair advantage by doing their business offshore and avoiding UK tax, which their UK competitors can't. The future for any competition seems bleak - not to mention the tax receipts from retailing.

What we urgently need is a potential UK competitor to Amazon. I would certainly use them - no, let's be clear - as long as they are efficient, I am absolutely aching to use them. So here is my solution: it is time for Ocado to gear up and take their rightful place. I'm right behind them...

But it will require the UK government to step in and make sure that any new UK competitor can operate effectively and fairly against tax avoiders like Amazon. They can't allow the tax avoiders to drive out the rest - but that will happen, unless they ACT.

Published on October 20, 2013 02:19

David Boyle's Blog

- David Boyle's profile

- 53 followers

David Boyle isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.