David Boyle's Blog, page 63

December 9, 2013

Why our cities are going to change

I spent the last few days of last week teaching at Schumacher College. My task: to talk about how to change the world.

This involved talking about how to get politicians onside, and what makes them tick as a breed, and I found myself taking at not altogether welcome sideways look at myself – one foot ion the world of idealistic green economics and the other in the world of formal politics, in the shape of the Lib Dems.

The trouble with talking to idealists about parliamentary politics is that, for very good reasons, it looks like the art of compromise. From outside, it can look a little grubby. From inside Westminster, of course, the outside world looks alternatively feckless, sometimes apathetic and occasionally raucous.

None of these impressions is accurate, but they don't help communication.

I had to remind myself afterwards why I feel so hopeful about the future. The main reason goes back to the Schumacher Lectures in Bristol some years ago.

I gave my habitual seminar about the future of money and, to my surprise, over a hundred people turned up in the morning and another hundred in the afternoon, and that was just the fringe.

After one of these seminars, a very attractive girl called Rowena came up to me and asked my advice about how to start a goat farm.

This is not something that I've ever been asked before, but it occurred to me that – for the first time since the 1890s – there was a group of young people who interpreted their radicalism in terms of growing stuff.

They were a subset of a much larger cohort of highly intelligent, highly motivated group of 20-somethings, who might best be described as social entrepreneurs. They are now active in most cities and towns in the UK, often through the Transition Towns movement.

It must have felt like this in the 1930s, looking at the new cadre of young enthusiasts who were socialists in those days socialists and realising that – in a decade's time – they would be running the cities. And so it proved.

I feel the same now. In a decades time, those young people will be in their 30s and running our cities. A decade after that, no Westminster government will be able to act without them. They represent the future, and it is now steeped in transition economics.

The only thing that can stop them is the way that our Westminster politics manages to stay insulated from almost everything. There is a hideous self-perpetuating element to it, talented, intelligent, imaginative - and yet still boneheaded.

The phenomenon I’m talking about goes way beyond the Transition movement, but Transition provides part of the inspiration - which comes, in this case, from Rob Hopkins and his emphasis on the critical importance of doing things - hence his new book The Power of Just Doing Stuff. Previous local green action, like Local Agenda 21, was all about begging the local authority to do things - Transition realises that, to make things happen, you have to do it yourself.

The lesson here is partly for the Transition movement itself. It needs to rise to the next challenge. Now they are influencing city government, or just beginning to. Within a decade, they have to run the places.

What this means is not that they will be a political party, or an opposition administration in waiting, but that their skill at making things happen will make them indispensible to every political party.

This involved talking about how to get politicians onside, and what makes them tick as a breed, and I found myself taking at not altogether welcome sideways look at myself – one foot ion the world of idealistic green economics and the other in the world of formal politics, in the shape of the Lib Dems.

The trouble with talking to idealists about parliamentary politics is that, for very good reasons, it looks like the art of compromise. From outside, it can look a little grubby. From inside Westminster, of course, the outside world looks alternatively feckless, sometimes apathetic and occasionally raucous.

None of these impressions is accurate, but they don't help communication.

I had to remind myself afterwards why I feel so hopeful about the future. The main reason goes back to the Schumacher Lectures in Bristol some years ago.

I gave my habitual seminar about the future of money and, to my surprise, over a hundred people turned up in the morning and another hundred in the afternoon, and that was just the fringe.

After one of these seminars, a very attractive girl called Rowena came up to me and asked my advice about how to start a goat farm.

This is not something that I've ever been asked before, but it occurred to me that – for the first time since the 1890s – there was a group of young people who interpreted their radicalism in terms of growing stuff.

They were a subset of a much larger cohort of highly intelligent, highly motivated group of 20-somethings, who might best be described as social entrepreneurs. They are now active in most cities and towns in the UK, often through the Transition Towns movement.

It must have felt like this in the 1930s, looking at the new cadre of young enthusiasts who were socialists in those days socialists and realising that – in a decade's time – they would be running the cities. And so it proved.

I feel the same now. In a decades time, those young people will be in their 30s and running our cities. A decade after that, no Westminster government will be able to act without them. They represent the future, and it is now steeped in transition economics.

The only thing that can stop them is the way that our Westminster politics manages to stay insulated from almost everything. There is a hideous self-perpetuating element to it, talented, intelligent, imaginative - and yet still boneheaded.

The phenomenon I’m talking about goes way beyond the Transition movement, but Transition provides part of the inspiration - which comes, in this case, from Rob Hopkins and his emphasis on the critical importance of doing things - hence his new book The Power of Just Doing Stuff. Previous local green action, like Local Agenda 21, was all about begging the local authority to do things - Transition realises that, to make things happen, you have to do it yourself.

The lesson here is partly for the Transition movement itself. It needs to rise to the next challenge. Now they are influencing city government, or just beginning to. Within a decade, they have to run the places.

What this means is not that they will be a political party, or an opposition administration in waiting, but that their skill at making things happen will make them indispensible to every political party.

Published on December 09, 2013 04:26

December 5, 2013

Why zoos used to be so funny

The news that an American court is being asked to decide if chimpanzees have the equivalent of human rights seems to me to be an important milestone.

The news that an American court is being asked to decide if chimpanzees have the equivalent of human rights seems to me to be an important milestone.The interview on the Today programme yesterday singled out elephants, whales and dolphins, as deserving similar treatment. They are self-aware, deeply intelligent and sentient. Of course they should be given 'personhood' under the law.

In fact, by the end of the interview - which had clearly been arranged for tongue-in-cheek treatment by John Humphreys - I was completely convinced.

I've no idea what the court will decide, but it does seem to be another nail in the coffin for zoos.

I have a theory about this. About two decades ago, I was working on a brilliant schools TV history series called Time Capsule (made by the equally brilliant Colin Still) and found myself ploughing through copy after copy of Victorian editions of Punch, in search of illustrations for the rostrum camera.

There were a large number of cartoons about zoos and it slowly dawned on me that they nearly all had something important in common. The zoo visitors were nearly always portrayed as roaring with laughter.

These days, zoos are rather po-faced, serious, politically correct places. The Victorian purpose of zoos - an afternoon of comedy - did survive into my lifetime in the form of the chimpanzees' tea party, but not for long. I believe that was why people used to visit them. The animals were funny.

Of course this is all very regrettable. Yes, there is a parallel with the previous century's recourse to Bedlam for a good laugh. But equally, I'm not sure that - when we laugh at and with our pets the whole time - the disappearance of laughter from zoos is altogether healthy.

Perhaps I'm just insensitive. But I'm not sure that the current very SERIOUS zoos are going to survive, at least in their current form - and it is pretty vital, if chimpanzees are going to get any kind of rights, that people are exposed to the existence of other species apart from their own.

Published on December 05, 2013 01:29

December 4, 2013

The economic consequences of Boris

The transcript of Boris Johnson’s notorious speech about IQ reveals it wasn’t quite as crass as it was portrayed. But it nearly was, and it also contains a tremendously important mistake about inequality.

I personally find the whole idea of Boris infuriating. This is because, since I had second preference vote in 2008I bestowed it on him rather than Ken Livingstone because of one issue alone: the blight of skyscrapers in London,

Ken used to call in architects and ask if they couldn’t make their plans any taller. It was part of his disastrous scheme to increase the population of London (now you have to queue to get out of the tube stations as well as queuing to get in, and still nobody has funded the necessary new schools).

Boris ran with the issue in his first election. The result: now he can hardly see a skyscraper without giving it permission.

So I feel a special sense of betrayal now that I discover that his stance, and maybe all his stances, was pure electoral cant.

Perhaps it is the authentic whiff of Blair: a man with a certain charm and apparently without convictions.

What do I have against skyscrapers? They are inhuman. They reduce us all by their brash monument to architectural or financier ego. They undermine our humanity. I hate them: the essence of London is to be human-scale – or it was.

And there in a nutshell is also my problem with Boris’ speech. Because greed, when it is exercised without restraint, has consequences for the rest of us. It is inhuman. It has architectural consequences, but it also has economic consequences.

He is right, of course, that some measure of inequality is necessary for the proper functioning of everything. “A man’s reach should exceed his grasp,” said Robert Louis Stevenson, and he was right.

Nobody believes everyone should be the same. But that isn’t the same as condoning a repulsive inequality, or the emergence of a new cadre of ubermensch, who cannot be regulated, who corrode what they touch and who are paid in king’s ransoms.

I know that Richard Wilkinson and his colleagues in the Equality Trust have discovered statistical links between inequality and a whole range of social problems. I’m not talking about that here. What worries me is the very specific economic consequences of the new elite.

They can be summed up in one word: inflation.

Why are house prices now unaffordable in London? Because of banker’s bonuses. It is Boris’ bankers that are driving out the middle classes – and raising the prices of a whole range of goods, making life less affordable. See my book Broke for more of an explanation.

Not to mention the speculation on food commodities, pushing up the prices.

No, the consequences of Boris’ financial elite is that civilised life is more difficult, less possible for the rest of us. It is the precise reverse of a property-owning democracy.

It is all very well to say that the elite pay a heavy proportion of tax. They also raise the property prices, adding disastrously to the costs of housing benefit – through no fault to the poor. They are walking inflation machines.

Boris wraps himself in the union jack in a subtle way, but let’s be clear. This kind of inequality is precisely the opposite of patriotic. It is corroding our way of life.

I personally find the whole idea of Boris infuriating. This is because, since I had second preference vote in 2008I bestowed it on him rather than Ken Livingstone because of one issue alone: the blight of skyscrapers in London,

Ken used to call in architects and ask if they couldn’t make their plans any taller. It was part of his disastrous scheme to increase the population of London (now you have to queue to get out of the tube stations as well as queuing to get in, and still nobody has funded the necessary new schools).

Boris ran with the issue in his first election. The result: now he can hardly see a skyscraper without giving it permission.

So I feel a special sense of betrayal now that I discover that his stance, and maybe all his stances, was pure electoral cant.

Perhaps it is the authentic whiff of Blair: a man with a certain charm and apparently without convictions.

What do I have against skyscrapers? They are inhuman. They reduce us all by their brash monument to architectural or financier ego. They undermine our humanity. I hate them: the essence of London is to be human-scale – or it was.

And there in a nutshell is also my problem with Boris’ speech. Because greed, when it is exercised without restraint, has consequences for the rest of us. It is inhuman. It has architectural consequences, but it also has economic consequences.

He is right, of course, that some measure of inequality is necessary for the proper functioning of everything. “A man’s reach should exceed his grasp,” said Robert Louis Stevenson, and he was right.

Nobody believes everyone should be the same. But that isn’t the same as condoning a repulsive inequality, or the emergence of a new cadre of ubermensch, who cannot be regulated, who corrode what they touch and who are paid in king’s ransoms.

I know that Richard Wilkinson and his colleagues in the Equality Trust have discovered statistical links between inequality and a whole range of social problems. I’m not talking about that here. What worries me is the very specific economic consequences of the new elite.

They can be summed up in one word: inflation.

Why are house prices now unaffordable in London? Because of banker’s bonuses. It is Boris’ bankers that are driving out the middle classes – and raising the prices of a whole range of goods, making life less affordable. See my book Broke for more of an explanation.

Not to mention the speculation on food commodities, pushing up the prices.

No, the consequences of Boris’ financial elite is that civilised life is more difficult, less possible for the rest of us. It is the precise reverse of a property-owning democracy.

It is all very well to say that the elite pay a heavy proportion of tax. They also raise the property prices, adding disastrously to the costs of housing benefit – through no fault to the poor. They are walking inflation machines.

Boris wraps himself in the union jack in a subtle way, but let’s be clear. This kind of inequality is precisely the opposite of patriotic. It is corroding our way of life.

Published on December 04, 2013 09:36

December 3, 2013

Less should be more: the mismatch emerging in public services

I get my gas from British Gas. It isn't a perfect solution, and I will be getting £53 of their vast price increase back, I gather. Whoopee. I can't quite get my head around why this tweak works, but it has made me think about the way our services are currently structured.

Either way, I am not exactly celebrating.

Let me say, before anyone categorises me, that I have no problem with private companies delivering services, as long as they do so on a human-scale, and do so without so narrowing what they deliver that they spread extra costs around the system.

You might say that I am therefore against privatisation, but it isn't the principle that bothers me. It is the current practice.

But there is a more fundamental problem about the way privatised services behave, especially when it comes to cost-saving. It is the need they have to maximise profits.

The way this is usually tackled, at least for privatised utilities, is to impose a regulator in the situation which prevents profits from being maximised at the expense of consumers. That is all well and good, but it covers up the fact that there is an increasingly important mismatch between the needs of the shareholders and the needs of the public as a whole.

Take energy for example. The overwhelming need, for government and people alike, is to help people use less energy. The overwhelming imperative for the energy utilities is to encourage them to use more.

We cover up this mismatch using profit-making financial institutions, like ESCOs, that can share in the benefits of energy-saving. But there comes a point when it isn't enough - and it isn't enough now.

That is why I am unhappy about the responsibility for insulating poorly-build UK homes shifting from the energy companies to tax-payers. It means that this basic mismatch is now absolutely stark.

It is equally stark in privatised healthcare. Again, the needs of the public and the government are aligned. They both want less demand, less ill-health. The healthcare companies want something different.

Often the mismatch goes beyond stark, especially when contractors are paid for throughput, or paid for the number of calls they answer - never mind whether the calls are actually what the systems thinker John Seddon calls failure demand (people phoning up to find out why nothing happened last time they called).

This is a serious problem with the current public services agenda. It is a system problem. If it isn't solved, it will lead to rocketing costs. Because there comes a point where privatising services is no longer a useful way of saving money, because the efficiency savings have long since been made, and all they can do is get people to burn more energy.

Either way, I am not exactly celebrating.

Let me say, before anyone categorises me, that I have no problem with private companies delivering services, as long as they do so on a human-scale, and do so without so narrowing what they deliver that they spread extra costs around the system.

You might say that I am therefore against privatisation, but it isn't the principle that bothers me. It is the current practice.

But there is a more fundamental problem about the way privatised services behave, especially when it comes to cost-saving. It is the need they have to maximise profits.

The way this is usually tackled, at least for privatised utilities, is to impose a regulator in the situation which prevents profits from being maximised at the expense of consumers. That is all well and good, but it covers up the fact that there is an increasingly important mismatch between the needs of the shareholders and the needs of the public as a whole.

Take energy for example. The overwhelming need, for government and people alike, is to help people use less energy. The overwhelming imperative for the energy utilities is to encourage them to use more.

We cover up this mismatch using profit-making financial institutions, like ESCOs, that can share in the benefits of energy-saving. But there comes a point when it isn't enough - and it isn't enough now.

That is why I am unhappy about the responsibility for insulating poorly-build UK homes shifting from the energy companies to tax-payers. It means that this basic mismatch is now absolutely stark.

It is equally stark in privatised healthcare. Again, the needs of the public and the government are aligned. They both want less demand, less ill-health. The healthcare companies want something different.

Often the mismatch goes beyond stark, especially when contractors are paid for throughput, or paid for the number of calls they answer - never mind whether the calls are actually what the systems thinker John Seddon calls failure demand (people phoning up to find out why nothing happened last time they called).

This is a serious problem with the current public services agenda. It is a system problem. If it isn't solved, it will lead to rocketing costs. Because there comes a point where privatising services is no longer a useful way of saving money, because the efficiency savings have long since been made, and all they can do is get people to burn more energy.

Published on December 03, 2013 02:50

December 2, 2013

The strange irony about literary Hay-on-Wye

Thank you to everyone who came along to talk about

What If Money Grew on Trees

with Andrew Simms and I. There is obviously an appetite to talk about other possibilities – and their strange side-effects, and we both had a brilliant time.

Thank you to everyone who came along to talk about

What If Money Grew on Trees

with Andrew Simms and I. There is obviously an appetite to talk about other possibilities – and their strange side-effects, and we both had a brilliant time.The Hay Winter Festival is not quite the same as Hay-on-Wye in the vast tents in the summer, but it is rather wonderful nonetheless. In fact, I found Hay particularly life-enhancing last weekend, with its little Christmas lights, its beautiful bookshops and its dark, dark nights.

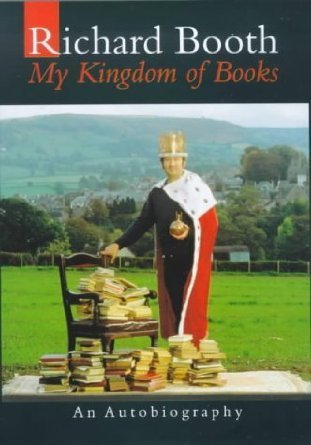

I was particularly pleased to visit Richard Booth’s new bookshop and to see, almost at a glance, the future of publishing.

Ebooks are driving old-fashioned book publishing in new directions, or rather old, more authentic directions, publishing real books as beautiful objects. Why would you buy a badly-published book if you could buy an ebook cheaper, after all?

Booth is the great pioneer of Hay as a book town. Back in 1973, he declared himself king of an independent Hay and led torchlight processions through the town. He was careful to avoid a charge of possible sedition by doing so on April Fool’s Day.

I was just interested in politics at the time (I was 14) and was thrilled by the idea, and collected Hay national memorabilia, which I still have in the back of my sock draw.

In fact, looking back, that may remain the big difference between Liberals and Social Democrats, before the famous merger of the two parties 15 years later. Liberals are fascinated by the idea of micro-states declaring UDI, of the continuing Passport to Pimlicotendency in our national life; social democrats are rather revolted by it.

Booth is one of the great pioneers of ultra-local economics, and I have huge respect for him. But there is an irony about Hay, which I recently discovered by reading Booth’s autobiography.

He made his money, and launched himself as the bookish saviour of an otherwise ordinary market town in the Welsh borders, by buying up the libraries of the working men’s clubs, which were being sold off in the 1960s – a kind of working class privatisation.

It is peculiar that the foundations of Hay today, that monument to middle class dreams, is based on the self-immolation of the tradition of working class self-help.

Published on December 02, 2013 05:55

December 1, 2013

The staggering re-invention of Clegg

This is a post about an aspect of the benefits for immigrants debate last week which has gone without comment - and it isn't really about immigration, but let's get that bit out of the way first.

Not everyone has found themselves supporting Nick Clegg's qualified support for Cameron's proposal on benefits for East European immigrants in the first three months of their stay. Including some people I usually agree with in every nuance, like Jonathan Calder.

I understand the argument that politicians should try to change perceptions not pander to them, but there may be moments where making that kind of stand simply drives people apart. I don't know (I know, I should know).

But I want to draw a Liberal distinction here, between hospitality, open cultures and open borders for refugees, who have - after all - given so much back to the UK. And, on the other side, encouraging people for boneheaded economic reasons to be footloose - and it may be that borders can be so open that they do that.

I believe in a multi-racial society. I believe in travel and the transmission of ideas between cultures. But I don't think that we should be discouraging community, and roots, and commitment to place.

I don't want to live in the kind of world where economic disadvantage can only be solved by getting onto a boat - as Norman Tebbitt's father famously got on a bike - and looking for work. As if we just abandon towns, cities and nations as the American pioneers abandoned their land, having exhausted it, and move east.

It is no basis for a happy, fulfilled and peaceful world. So yes, move if you have to - certainly if your life depends on it. But otherwise, let's find the economic tools we need to regenerate places. Don't let the narrow doctrine of comparative advantage lead us to abandon half the world.

But I must admit, that isn't the reason today for putting finger to keyboard.

It was at the end of the BBC news that I heard it. They reported Cameron's plans and then, at the end of the headline - as if it was a throwaway line - they said: "The deputy prime minister, Nick Clegg, has agreed to this."

I did a double take. This was the BBC recognising what makes the difference between Cameron's proposal happening and it not happening, and it has huge implications for the way the two men are perceived.

Suddenly you realise that, behind every prime ministerial announcement, is this element of doubt in the minds of broadcasters. Has he got permission for this? Will it happen?

It really is staggering how far the DPM has travelled in just three years in post. Gone are the days when he was the supplicant as the leader of the smaller party. Now he appears as this supra-national, supra-political figure - hovering like a Lord Chief Justice over the political array - lending his benediction to some of Cameron's ideas and withholding it from others.

Perhaps the most skillful positioning, and despite a weekly radio phone-in, is that Clegg manages to appear careful and sparing in his public pronouncements, while Cameron's public pronouncements seem increasingly frequent and increasingly stressed.

I don't know how this has been achieved. I don't even know if it is a good thing for the Lib Dems, let alone the coalition, though it must irritate the prime minister beyond all measure. But it is astonishing and it is impressive.

Not everyone has found themselves supporting Nick Clegg's qualified support for Cameron's proposal on benefits for East European immigrants in the first three months of their stay. Including some people I usually agree with in every nuance, like Jonathan Calder.

I understand the argument that politicians should try to change perceptions not pander to them, but there may be moments where making that kind of stand simply drives people apart. I don't know (I know, I should know).

But I want to draw a Liberal distinction here, between hospitality, open cultures and open borders for refugees, who have - after all - given so much back to the UK. And, on the other side, encouraging people for boneheaded economic reasons to be footloose - and it may be that borders can be so open that they do that.

I believe in a multi-racial society. I believe in travel and the transmission of ideas between cultures. But I don't think that we should be discouraging community, and roots, and commitment to place.

I don't want to live in the kind of world where economic disadvantage can only be solved by getting onto a boat - as Norman Tebbitt's father famously got on a bike - and looking for work. As if we just abandon towns, cities and nations as the American pioneers abandoned their land, having exhausted it, and move east.

It is no basis for a happy, fulfilled and peaceful world. So yes, move if you have to - certainly if your life depends on it. But otherwise, let's find the economic tools we need to regenerate places. Don't let the narrow doctrine of comparative advantage lead us to abandon half the world.

But I must admit, that isn't the reason today for putting finger to keyboard.

It was at the end of the BBC news that I heard it. They reported Cameron's plans and then, at the end of the headline - as if it was a throwaway line - they said: "The deputy prime minister, Nick Clegg, has agreed to this."

I did a double take. This was the BBC recognising what makes the difference between Cameron's proposal happening and it not happening, and it has huge implications for the way the two men are perceived.

Suddenly you realise that, behind every prime ministerial announcement, is this element of doubt in the minds of broadcasters. Has he got permission for this? Will it happen?

It really is staggering how far the DPM has travelled in just three years in post. Gone are the days when he was the supplicant as the leader of the smaller party. Now he appears as this supra-national, supra-political figure - hovering like a Lord Chief Justice over the political array - lending his benediction to some of Cameron's ideas and withholding it from others.

Perhaps the most skillful positioning, and despite a weekly radio phone-in, is that Clegg manages to appear careful and sparing in his public pronouncements, while Cameron's public pronouncements seem increasingly frequent and increasingly stressed.

I don't know how this has been achieved. I don't even know if it is a good thing for the Lib Dems, let alone the coalition, though it must irritate the prime minister beyond all measure. But it is astonishing and it is impressive.

Published on December 01, 2013 00:58

November 30, 2013

When free trade gets twisted

[image error]

I speak as a Liberal when I say that nine score and a handful of years ago, our fathers brought forth a great idea into the political firmament. It was a logical extension of the anti-slavery movement, and it was called 'free trade'.

It framed the debate about business in terms of human liberty, explaining that when businesses get too big, or when they join forces with governments or ally with landed interests, then the prices rise - and those people who have been released from slavery fall victim to a new economic tyranny.

That was the 1830s. Thirty years later, simultaneously on both sides of the world - the North American slaves and the Russian serfs were declared free (both in 1863). In both cases, the worst fears of the new free-traders came to pass. The liberated slaves of the deep south and the newly freed peasants of Russia and Poland were both loaded down with debt which they could never repay - a new form of economic control.

Forty years after that, the American free traders took on the robber barons and monopolists in a series of actions, breaking up Rockefeller's Standard Oil and others. At the same time, the British Liberals were winning a landslide election on the cause of free trade - which they regarded as the right of small enterprise to challenge the status quo.

Over the following century, something peculiar happened. 'Free trade' became muddled. The Liberal campaigners turned to other things. Free trade slowly came to mean the rights of all business, however large. Later on, it became even more twisted to mean the right of the richest and most powerful to ride roughshod over everyone else, almost the precise opposite of its original intention.

Now, the news emerges that the long-term negotiations to bring about a EU-US trade agreement are back on.

What is in it? Some sensible stuff about recognising each other's standards and regulations probably. The issue of GM food and cloned meat will take a bit of unpicking, and probably remains unpicked.

Why worry about it? Because of what has appeared on Wikileaks about the draft of the new US-Pacific trade agreement, which was to have been 'fast-tracked' through Congress, and which includes a supra-national court system whereby any corporation can sue a government if it felt it was infringing its rights.

There is no way that a package of measures that pits the commercial objectives of the richest above our democratic rights to shape our lives is related to free trade in any sense. It is a kind of protectionism for the powerful, and for the status quo. It is the precise opposite of anything Cobden and Bright would have recognised.

For years, we in the political West have comforted ourselves that free trade in China would transform it into a genuine tolerant democracy. I'm not so sure that this perversion of free trade, monopolistic control bolstered by law - a kind of compulsory trade - will not eventually work the other way, and turn us into China.

But there is a more prosaic reason to worry about this.

The EU has a reputation in some circles for its mind-numbing regulation. Most of these are, in fact, as a direct result of the single market that the UK pushed through in the 1990s. Ironic, isn't it. Regulations about transparent procurement processes, and permission for state aid payments, all stem from the same source. Probably the US trade agreement, if it happens, will mean more of it.

That is free trade, of a kind. But in practice, it privileges large foreign competition against homegrown small business competition. It needn't do, but in practice it does - because only the biggest players can jump through the bureaucratic hoops (and that's before you get to the minimum size thresholds).

Like so much of the rest of the ersatz free trade agenda, it gives power to the powerful and protects them against competition from below. It is the very opposite of a Liberal free trade policy as recognised by Cobden and Bright all those decades ago.

It framed the debate about business in terms of human liberty, explaining that when businesses get too big, or when they join forces with governments or ally with landed interests, then the prices rise - and those people who have been released from slavery fall victim to a new economic tyranny.

That was the 1830s. Thirty years later, simultaneously on both sides of the world - the North American slaves and the Russian serfs were declared free (both in 1863). In both cases, the worst fears of the new free-traders came to pass. The liberated slaves of the deep south and the newly freed peasants of Russia and Poland were both loaded down with debt which they could never repay - a new form of economic control.

Forty years after that, the American free traders took on the robber barons and monopolists in a series of actions, breaking up Rockefeller's Standard Oil and others. At the same time, the British Liberals were winning a landslide election on the cause of free trade - which they regarded as the right of small enterprise to challenge the status quo.

Over the following century, something peculiar happened. 'Free trade' became muddled. The Liberal campaigners turned to other things. Free trade slowly came to mean the rights of all business, however large. Later on, it became even more twisted to mean the right of the richest and most powerful to ride roughshod over everyone else, almost the precise opposite of its original intention.

Now, the news emerges that the long-term negotiations to bring about a EU-US trade agreement are back on.

What is in it? Some sensible stuff about recognising each other's standards and regulations probably. The issue of GM food and cloned meat will take a bit of unpicking, and probably remains unpicked.

Why worry about it? Because of what has appeared on Wikileaks about the draft of the new US-Pacific trade agreement, which was to have been 'fast-tracked' through Congress, and which includes a supra-national court system whereby any corporation can sue a government if it felt it was infringing its rights.

There is no way that a package of measures that pits the commercial objectives of the richest above our democratic rights to shape our lives is related to free trade in any sense. It is a kind of protectionism for the powerful, and for the status quo. It is the precise opposite of anything Cobden and Bright would have recognised.

For years, we in the political West have comforted ourselves that free trade in China would transform it into a genuine tolerant democracy. I'm not so sure that this perversion of free trade, monopolistic control bolstered by law - a kind of compulsory trade - will not eventually work the other way, and turn us into China.

But there is a more prosaic reason to worry about this.

The EU has a reputation in some circles for its mind-numbing regulation. Most of these are, in fact, as a direct result of the single market that the UK pushed through in the 1990s. Ironic, isn't it. Regulations about transparent procurement processes, and permission for state aid payments, all stem from the same source. Probably the US trade agreement, if it happens, will mean more of it.

That is free trade, of a kind. But in practice, it privileges large foreign competition against homegrown small business competition. It needn't do, but in practice it does - because only the biggest players can jump through the bureaucratic hoops (and that's before you get to the minimum size thresholds).

Like so much of the rest of the ersatz free trade agenda, it gives power to the powerful and protects them against competition from below. It is the very opposite of a Liberal free trade policy as recognised by Cobden and Bright all those decades ago.

Published on November 30, 2013 01:28

November 29, 2013

The meaning of the housing bubble

"Sometimes thing don't always go/

From bad to worse..."

So wrote the poet Sheelagh Pugh, and I kind of agreed with her yesterday when I read about the Bank of England's decision to rein in Funding for Lending, and to provide a kind of ratchet effect that will reduce the dangerous acceleration of the housing market.

It isn't much and it isn't enough, but it is a start.

But first a bit of background. One of the stories I told earlier this year in my book Broke: Who Killed the Middle Classes? was about the demise of the so-called Corset in 1980.

The Corset was the mechanism which restricted the flow of money into the mortgage market, so that house prices stayed stable, but housebuilders still made a profit.

Since it disappeared, the 30-year house price bubble - especially in the south east - first thrilled the middle classes and now looks set to destroy them (my children will be unable to rent or buy in London or the south east unless they work in financial services, a fate worse than death as far as I'm concerned).

The issue isn't really that the Corset should have stayed in place. The end of exchange controls in 1979 guaranteed its demise. The problem was that nothing was put in to replace it. In fact, within months of the decision to end the Corset, the whole tenor of the debate had shifted.

We know now that the idea that somehow all prices reflected something real was a fundamental mistake which still infects many – especially in banks, where they still bolster their balance sheets with property values, only to have those values slip through their fingers.

We might know that now but, by the end of the Corset, it flew in the face of the new spirit of the times to point it out.

Hidden in the archives of the Bank of England, I discovered a revealing note. It was a memo from the governor (Gordon Richardson) in May 1980, weeks before the Corset was finally loosened, and described meeting a City grandee who asked him why nothing had been put in place to replace it.

The deputy governor had added his own note on the file describing the hapless grandee:

"Were he a Tory MP he would I fear rightly qualify for a certain adjective in rather wide current use."

The adjective he referred to was ‘wet’, Margaret Thatcher’s new designation for her opponents in the cabinet. ‘Rather sad, I think,’ wrote the governor.

Nothing has replaced the Corset, and Thatcherism – heralded by the new and vigorously enforced consensus implied by this note – would countenance no such defences against insanity. House prices would find their proper level, whatever they happened to be, and the acceleration upwards had barely begun. The consequences have been profound.

Carney hasn't proposed a return to the Corset, but he has tiptoed in that direction. Banks will have to assess whether people taking out mortgages will be able to afford an increase in base rates to 3%. They will have to raise extra capital against the mortgages they lend.

There is no doubt that this will contract mortgage lending, though whether it will really increase small business lending remains to be seen - the evidence so far is that the big banks are no longer geared up or able to do this effectively.

I've just got two thoughts about this.

First, property prices in London and the south east are unsustainable. They are geared for the pockets of the ultra-rich, for bankers bonuses and foreign investors. They need to come down, slowly but surely, to make civilised life possible for the next generation.

Second, nobody seems to talk about this much, but the main source of money-creation in the economy these days is in the form of mortgage loans. If they contract, and nothing replaces them, there will be less money in the economy - and we will all be wondering why the world is deflating around us again.

That is the consequences of our collective failure to rebalance the economy.

From bad to worse..."

So wrote the poet Sheelagh Pugh, and I kind of agreed with her yesterday when I read about the Bank of England's decision to rein in Funding for Lending, and to provide a kind of ratchet effect that will reduce the dangerous acceleration of the housing market.

It isn't much and it isn't enough, but it is a start.

But first a bit of background. One of the stories I told earlier this year in my book Broke: Who Killed the Middle Classes? was about the demise of the so-called Corset in 1980.

The Corset was the mechanism which restricted the flow of money into the mortgage market, so that house prices stayed stable, but housebuilders still made a profit.

Since it disappeared, the 30-year house price bubble - especially in the south east - first thrilled the middle classes and now looks set to destroy them (my children will be unable to rent or buy in London or the south east unless they work in financial services, a fate worse than death as far as I'm concerned).

The issue isn't really that the Corset should have stayed in place. The end of exchange controls in 1979 guaranteed its demise. The problem was that nothing was put in to replace it. In fact, within months of the decision to end the Corset, the whole tenor of the debate had shifted.

We know now that the idea that somehow all prices reflected something real was a fundamental mistake which still infects many – especially in banks, where they still bolster their balance sheets with property values, only to have those values slip through their fingers.

We might know that now but, by the end of the Corset, it flew in the face of the new spirit of the times to point it out.

Hidden in the archives of the Bank of England, I discovered a revealing note. It was a memo from the governor (Gordon Richardson) in May 1980, weeks before the Corset was finally loosened, and described meeting a City grandee who asked him why nothing had been put in place to replace it.

The deputy governor had added his own note on the file describing the hapless grandee:

"Were he a Tory MP he would I fear rightly qualify for a certain adjective in rather wide current use."

The adjective he referred to was ‘wet’, Margaret Thatcher’s new designation for her opponents in the cabinet. ‘Rather sad, I think,’ wrote the governor.

Nothing has replaced the Corset, and Thatcherism – heralded by the new and vigorously enforced consensus implied by this note – would countenance no such defences against insanity. House prices would find their proper level, whatever they happened to be, and the acceleration upwards had barely begun. The consequences have been profound.

Carney hasn't proposed a return to the Corset, but he has tiptoed in that direction. Banks will have to assess whether people taking out mortgages will be able to afford an increase in base rates to 3%. They will have to raise extra capital against the mortgages they lend.

There is no doubt that this will contract mortgage lending, though whether it will really increase small business lending remains to be seen - the evidence so far is that the big banks are no longer geared up or able to do this effectively.

I've just got two thoughts about this.

First, property prices in London and the south east are unsustainable. They are geared for the pockets of the ultra-rich, for bankers bonuses and foreign investors. They need to come down, slowly but surely, to make civilised life possible for the next generation.

Second, nobody seems to talk about this much, but the main source of money-creation in the economy these days is in the form of mortgage loans. If they contract, and nothing replaces them, there will be less money in the economy - and we will all be wondering why the world is deflating around us again.

That is the consequences of our collective failure to rebalance the economy.

Published on November 29, 2013 01:07

November 28, 2013

The antidote to sclerosis brought on by complexity

The blogpost is cross-posted from www. newweather.org...

The blogpost is cross-posted from www. newweather.org...I listened to the Localis lecture by Penrith MP Rory Stewart yesterday, talking about the importance of local action - if we are going to fulfil our promise to our children that they can grow up and re-make the world.

He told the story of a small village in his constituency and their long battle to get a broadband connection, digging the trench, raising money and eventually persuading the government to fund the remaining £17,500 - a long, exhausting process.

Exhausting because of the complications which inevitably emerge for this kind of project: was the decision to choose the only possible contractor open and transparent? Would Brussels give permission to pay this money in state aid? You can imagine the kind of thing.

All this is, of course, paradoxically the result of the single market, the side-effects of a certain interpretation of free trade - and I expect there will be even more of it imposed on us under the new EU-US trade agreement.

But it also demonstrates the sheer complexity of making anything happen now, however simple and uncontroversial. The sheer complexity of government at all levels discourages action: we don't know what side-effects there will be. It is often just too much of a risk to experiment by finding out.

If the political world is too complicated then the same is even more true of economics. The economic world is so staggeringly complex that no sane economist will be able to predict the consequences of anything much. The result is that economists, like civil servants and politicians, are like deer caught in the headlights. They dare not even imagine major changes. They dare not, even in their sleep, dream of different worlds.

Which brings me to the new book I have edited called What If Money Grew on Trees? It is a series of very short contributions, by economics writers, in answer to 50 different What If questions - what if money did grow on trees? What would happen?

These are alternative tales of the present and immediate future, written as honestly as possible about the effects and side-effects. And one of my co-authors (Andrew Simms) and I are delving into the world of other possibilities, at the winter version of the Hay Literary Festival at 1.55pm on Sunday.

Do come along and imagine with us!

Published on November 28, 2013 01:26

November 27, 2013

Turning the PR industry on its head, at last

Lord Leverhulme famously said this about advertising: "Half the money I spend on advertising is wasted, and the problem is I do not know which half".

If that was true of advertising, then how much more true of it in public relations. You would be lucky just to waste half your money, certainly if you add up the retainer, the vast amount of wasted stuff pushed into envelopes, the sheer irritation of PR as conventionally delivered.

I speak as someone who has been too often on the wrong end of PR. I remember, in the days when I was editor of Town & Country Planning in the late 1980s, I came to learn which envelopes should go straight in the bin. Among them were the wads of press releases published by the British Standards Institution, and delivered to me and thousands of others, at vast expense.

All of this mild rant is a way of explaining why I was excited to see a new model emerge, and I need a bit of transparency here - the co-founder, Kate Vick, is a friend. But I think she and her business partner Alie Griffiths have hit on a big idea when they launched One Day a Month.

PR is so much more complicated than it was when I used to open envelopes and get press releases. Who in their right mind uses press releases these days, except as a way of controlling what their spokespeople say? Social media opens the whole thing up.

The reason I was interested in this is that it is a potential game-changer in the PR industry, opening it up far more widely - and to people who would never accept, and can't afford, the usual way of doing things.

And it doesn't rely on IT. This is a new model the old-fashioned way: a new conception of how business can be organised. It can work...

If that was true of advertising, then how much more true of it in public relations. You would be lucky just to waste half your money, certainly if you add up the retainer, the vast amount of wasted stuff pushed into envelopes, the sheer irritation of PR as conventionally delivered.

I speak as someone who has been too often on the wrong end of PR. I remember, in the days when I was editor of Town & Country Planning in the late 1980s, I came to learn which envelopes should go straight in the bin. Among them were the wads of press releases published by the British Standards Institution, and delivered to me and thousands of others, at vast expense.

All of this mild rant is a way of explaining why I was excited to see a new model emerge, and I need a bit of transparency here - the co-founder, Kate Vick, is a friend. But I think she and her business partner Alie Griffiths have hit on a big idea when they launched One Day a Month.

PR is so much more complicated than it was when I used to open envelopes and get press releases. Who in their right mind uses press releases these days, except as a way of controlling what their spokespeople say? Social media opens the whole thing up.

The reason I was interested in this is that it is a potential game-changer in the PR industry, opening it up far more widely - and to people who would never accept, and can't afford, the usual way of doing things.

And it doesn't rely on IT. This is a new model the old-fashioned way: a new conception of how business can be organised. It can work...

Published on November 27, 2013 03:24

David Boyle's Blog

- David Boyle's profile

- 53 followers

David Boyle isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.