David Boyle's Blog, page 80

May 29, 2013

The most important policy issue of the age (and nobody's talking about it)

"They must feel the thrill of totting up a balance book,

A thousand cyphers neatly in a row. When gazing at a graph that shows the profits up, Their little cup of joy should overflow."

Not me, of course, but Bert the Chimney Sweep’s satirical take on Mr George Banks’ view of what life is all about.

Not me, of course, but Bert the Chimney Sweep’s satirical take on Mr George Banks’ view of what life is all about.

Mary Poppins was the first film I ever saw. My father took me there at the Odeon Haymarket in 1965 and I have only recently seen it again, and the satire was a bit more obvious to me now than it was before.

But Bert wasn’t pouring scorn on business. He was pouring scorn on the reduction of business to numbers, which then as now is the province of the City of London. Or that is how I put it in my book The Tyranny of Numbers.

Now, the news emerged today that Justice Secretary Chris Grayling is intending to privatise the courts system (though not the judges, thank goodness for small mercies). That means many underlings in the City are now letting their cup of joy overflow at the prospect. Probably not terribly excited at the prospect of running the courts, but the prospect of the loans they can raise on the back of all that property is certainly a joy-overflowing business.

Now I have no ideological objections to privatisation. In fact, I think the obsessive argument around public-versus-private has held UK politics back for a generation. But, as I said recently in a blog post, the stated purpose of privatisation has subtly shifted, and debate doesn’t seem to have caught up with it.

In the heady says of selling off BT, the promoters could reasonably claim that privatisation was about getting a better service. That is certainly what happened. But nobody claims or believes these days that privatisation will make services better, for example of the post office. Still less the court system.

Privatisation is now about ‘efficiency’. All across public services, systems are being retooled to suit this particular notion of ‘rationalised’ efficiency, which means wielding the IT systems to create economies of scale, borrowing from the assembly line to create faster throughput. It is about creating efficiencies by narrowing the objectives to a handful of numerical outputs.

The real issue is whether this style of efficiency is actually very efficient, and here we have the central policy issue of our age – which hardly anyone is talking about. It is this: are economies of scale possible in public services? (remember: you heard it here first!)

I’m not claiming that economies of scale are somehow out of the question. They are obviously available. The question is how quickly they are overtaken by dis-economies of scale because narrowing the objectives impoverishes the services and creates costs elsewhere.

This is such an important issue because the whole future of our public sphere depends on the answer – and despite what you hear, there is actually very little evidence.

Coming up with a resolution to this means being able to look at two or three dimensions to a problem at once, yet so much policy assessment is still stuck in the days when people could only look at one dimension at any one time - cost-benefit analysis that only looks at the benefits, GDP that never subtracts, everyone will recognise the kind of stone age policy-making tools that are still used.

My side of the argument would suggest that the diseconomies very rapidly overtake the economies, because public services badly need an approach that is flexible and human enough to make a difference, once and for all. The alternative is services New Labour-style - which maintain people in their need with constant, repeated rationalised interventions which make no real difference, and do so at huge expense.

That is the real issue before us. Not public versus private, but big versus small, and rationalised efficiency versus effectiveness.

It explains why privatisation is actually on the way out, and for two inter-related reasons. The only way profit-making companies can profit is by using these assembly line techniques, and they are not very effective - and therefore hugely expensive. Yet if they don't use them, the profits are no longer available.

That is why so many private sector contracts are unravelling (see Serco for example). There isn't enough money for them.

Privatisation is being squeezed between the horns of this dilemma - the available profit shrinking and the costs rising because their systems are so much less effective than they need to be.

That is the world that will face us by the next general election, and then what? Certainly, it is Privatisation RIP, but what will replace it?

A thousand cyphers neatly in a row. When gazing at a graph that shows the profits up, Their little cup of joy should overflow."

Not me, of course, but Bert the Chimney Sweep’s satirical take on Mr George Banks’ view of what life is all about.

Not me, of course, but Bert the Chimney Sweep’s satirical take on Mr George Banks’ view of what life is all about.Mary Poppins was the first film I ever saw. My father took me there at the Odeon Haymarket in 1965 and I have only recently seen it again, and the satire was a bit more obvious to me now than it was before.

But Bert wasn’t pouring scorn on business. He was pouring scorn on the reduction of business to numbers, which then as now is the province of the City of London. Or that is how I put it in my book The Tyranny of Numbers.

Now, the news emerged today that Justice Secretary Chris Grayling is intending to privatise the courts system (though not the judges, thank goodness for small mercies). That means many underlings in the City are now letting their cup of joy overflow at the prospect. Probably not terribly excited at the prospect of running the courts, but the prospect of the loans they can raise on the back of all that property is certainly a joy-overflowing business.

Now I have no ideological objections to privatisation. In fact, I think the obsessive argument around public-versus-private has held UK politics back for a generation. But, as I said recently in a blog post, the stated purpose of privatisation has subtly shifted, and debate doesn’t seem to have caught up with it.

In the heady says of selling off BT, the promoters could reasonably claim that privatisation was about getting a better service. That is certainly what happened. But nobody claims or believes these days that privatisation will make services better, for example of the post office. Still less the court system.

Privatisation is now about ‘efficiency’. All across public services, systems are being retooled to suit this particular notion of ‘rationalised’ efficiency, which means wielding the IT systems to create economies of scale, borrowing from the assembly line to create faster throughput. It is about creating efficiencies by narrowing the objectives to a handful of numerical outputs.

The real issue is whether this style of efficiency is actually very efficient, and here we have the central policy issue of our age – which hardly anyone is talking about. It is this: are economies of scale possible in public services? (remember: you heard it here first!)

I’m not claiming that economies of scale are somehow out of the question. They are obviously available. The question is how quickly they are overtaken by dis-economies of scale because narrowing the objectives impoverishes the services and creates costs elsewhere.

This is such an important issue because the whole future of our public sphere depends on the answer – and despite what you hear, there is actually very little evidence.

Coming up with a resolution to this means being able to look at two or three dimensions to a problem at once, yet so much policy assessment is still stuck in the days when people could only look at one dimension at any one time - cost-benefit analysis that only looks at the benefits, GDP that never subtracts, everyone will recognise the kind of stone age policy-making tools that are still used.

My side of the argument would suggest that the diseconomies very rapidly overtake the economies, because public services badly need an approach that is flexible and human enough to make a difference, once and for all. The alternative is services New Labour-style - which maintain people in their need with constant, repeated rationalised interventions which make no real difference, and do so at huge expense.

That is the real issue before us. Not public versus private, but big versus small, and rationalised efficiency versus effectiveness.

It explains why privatisation is actually on the way out, and for two inter-related reasons. The only way profit-making companies can profit is by using these assembly line techniques, and they are not very effective - and therefore hugely expensive. Yet if they don't use them, the profits are no longer available.

That is why so many private sector contracts are unravelling (see Serco for example). There isn't enough money for them.

Privatisation is being squeezed between the horns of this dilemma - the available profit shrinking and the costs rising because their systems are so much less effective than they need to be.

That is the world that will face us by the next general election, and then what? Certainly, it is Privatisation RIP, but what will replace it?

Published on May 29, 2013 02:03

May 28, 2013

Down among the middle classes

I spent the bank holiday weekend immersed in the middle classes, camping in the Wye Valley. You could hear the great middle class call sign wafting across the campsite:

“I tell you what, you look after the children and I’ll faff around with the tent...”

I event ventured into the bastion of middle class life, Tyntesfield, the National Trust extravaganza outside Bristol.

The camping was lovely, the weather beautiful, the nights freezing and Tyntesfield was fabulous and magical. It comes to something when you can recognise something extraordinary in among the bric-a-brac, and I recognised a lifebelt from the German cruiser Bresslau, which escaped to Turkey in 1914 and was eventually mined in 1918 at the entrance to the Dardanelles.

How it got to be next to live next to a broken down bath chair in a National Trust property in England was anyone’s guess. The staff didn't know either.

It was a weekend that reminded me of some of the pecularities of the middle classes which I set out in my new book Broke: Who Killed the Middle Classes – their combination of law-abiding respectability with the assumption, unless proved otherwise, that all their neighbours are feckless.

Goodness knows, I felt it myself. It explains some of the reason why the middle classes are so suspicious of themselves, and increasingly so as they embrace a fashionable marketing-led bohemianism.

Tyntesfield was a revelation too. Just one teasel on each vintage chair was enough to prevent people from sitting on them. No signs ordering you around, no roped off areas, just restraint and tolerance.

This seems to me to be the central truth about the middle classes now, which alone is worth their survival, though - as I said in my book - their survival as a class looks increasingly precarious. Despite their suspicions, despite everything else, they are the force behind the increasing and almost unique tolerance of UK society.

Despite their reputation, the middle classes have actually presided over a period of unprecedented tolerance in British life, embracing a society that – despite the difficulties – is more and more diverse and multiracial, more and more tolerant of the peculiar way that people live, if they are not harming anyone else. And if this was not led by the middle classes, who was it led by?

I have wondered occasionally whether the National Trust might be a more effective political bastion for the middle classes than either Labour or the Conservatives, and said so in one of the first blogs I wrote here.

My admiration for the National Trust and its imagination and extraordinary volunteer-led good sense and good organisation. It is an inspiration for the public sector (or it ought to be). But I digress (and will again)...

“I tell you what, you look after the children and I’ll faff around with the tent...”

I event ventured into the bastion of middle class life, Tyntesfield, the National Trust extravaganza outside Bristol.

The camping was lovely, the weather beautiful, the nights freezing and Tyntesfield was fabulous and magical. It comes to something when you can recognise something extraordinary in among the bric-a-brac, and I recognised a lifebelt from the German cruiser Bresslau, which escaped to Turkey in 1914 and was eventually mined in 1918 at the entrance to the Dardanelles.

How it got to be next to live next to a broken down bath chair in a National Trust property in England was anyone’s guess. The staff didn't know either.

It was a weekend that reminded me of some of the pecularities of the middle classes which I set out in my new book Broke: Who Killed the Middle Classes – their combination of law-abiding respectability with the assumption, unless proved otherwise, that all their neighbours are feckless.

Goodness knows, I felt it myself. It explains some of the reason why the middle classes are so suspicious of themselves, and increasingly so as they embrace a fashionable marketing-led bohemianism.

Tyntesfield was a revelation too. Just one teasel on each vintage chair was enough to prevent people from sitting on them. No signs ordering you around, no roped off areas, just restraint and tolerance.

This seems to me to be the central truth about the middle classes now, which alone is worth their survival, though - as I said in my book - their survival as a class looks increasingly precarious. Despite their suspicions, despite everything else, they are the force behind the increasing and almost unique tolerance of UK society.

Despite their reputation, the middle classes have actually presided over a period of unprecedented tolerance in British life, embracing a society that – despite the difficulties – is more and more diverse and multiracial, more and more tolerant of the peculiar way that people live, if they are not harming anyone else. And if this was not led by the middle classes, who was it led by?

I have wondered occasionally whether the National Trust might be a more effective political bastion for the middle classes than either Labour or the Conservatives, and said so in one of the first blogs I wrote here.

My admiration for the National Trust and its imagination and extraordinary volunteer-led good sense and good organisation. It is an inspiration for the public sector (or it ought to be). But I digress (and will again)...

Published on May 28, 2013 03:15

May 27, 2013

The three lies of modern IT systems

I've rather belatedly realised there has been yet another IT catastrophe, this time at the BBC. I don't know the details, so I can't go on endlessly about how it fits into my uber-theory of IT cock-ups (basically because the systems that fail so expensively are really designed to take power away from people, not to enable them to do their job better).

There is another uber-theory, of course, which is that big mega-organisations like governments and mega public service broadcasters are staggeringly bad at specifying and managing IT projects, because they always over-complicate things. Perhaps we should be grateful that they only threw away £98 million.

More about where IT works and where it patently doesn't in my book The Human Element.

But as I was listening to the news about the BBC's digital sharing failure, I happened to be logging onto the website of yet another quango, using the same one of the variations of passwords I always use - and being asked for permission to plant cookies on my computer. It made me think how little we consider these apparent trifles.

After all, if I had said to myself - well, actually, now you mention it, I would prefer not to have cookies, I would have been excluded from their 'digital by default' services.

I don't actually have any choice. Rather as those companies which warn people with serious nut allergies that their products might contain traces of nuts, they are not actually being helpful - usually they don't - they are saying they can't be bothered to make sure.

So, since this is a bank holiday weekend, and the weather is brightening up (fingers crossed), here are the three lies of IT:

1. We are asking permission to embed cookies in your computer. It actually means: 'we will have nothing to do with you unless you let us plant our spy machines in your home'.

2. People are free to choose whether they accept our rules or not. Not actually. If you are confronted with agreeing to rules and conditions on a page from one of the semi-monopolist corporates that now dominate our lives - Microsoft or Google - then, unless you sign, you will be excluded completely from modern life. Probably arrested at airport security for good measure.

3. Our passwords are designed to give you security. Really? How many passwords do you have now? How many offices have you been where people keep their secure passwords on post-it notes above their screen?

I was 55 last week, so this may be may age speaking, but I find the reliance on passwords increasingly irritating. I have to juggle six of them just to get into my two children's homework. Of course, we need to keep identities secure, but there is a limit - and once you make passwords complex enough to keep you safe, then you increasingly need to write them down and render them insecure.

I offer this up as another Boyle's Law.

What I find especially irritating is that all the organisations we all deal with assume that they are the only one we deal with in the world. In fact, every store, service, quango and government department we use loads us down with more passwords and usernames.

It isn't sensible to use the same password for every organisation - and I don't - but I have recently been refusing to accept new passwords (from the bank and the tax credits megalith) and feel better every time.

They always sound a little hurt, but it doesn't seem to make any difference to accessing them. Of course it goes onto your records...

There is another uber-theory, of course, which is that big mega-organisations like governments and mega public service broadcasters are staggeringly bad at specifying and managing IT projects, because they always over-complicate things. Perhaps we should be grateful that they only threw away £98 million.

More about where IT works and where it patently doesn't in my book The Human Element.

But as I was listening to the news about the BBC's digital sharing failure, I happened to be logging onto the website of yet another quango, using the same one of the variations of passwords I always use - and being asked for permission to plant cookies on my computer. It made me think how little we consider these apparent trifles.

After all, if I had said to myself - well, actually, now you mention it, I would prefer not to have cookies, I would have been excluded from their 'digital by default' services.

I don't actually have any choice. Rather as those companies which warn people with serious nut allergies that their products might contain traces of nuts, they are not actually being helpful - usually they don't - they are saying they can't be bothered to make sure.

So, since this is a bank holiday weekend, and the weather is brightening up (fingers crossed), here are the three lies of IT:

1. We are asking permission to embed cookies in your computer. It actually means: 'we will have nothing to do with you unless you let us plant our spy machines in your home'.

2. People are free to choose whether they accept our rules or not. Not actually. If you are confronted with agreeing to rules and conditions on a page from one of the semi-monopolist corporates that now dominate our lives - Microsoft or Google - then, unless you sign, you will be excluded completely from modern life. Probably arrested at airport security for good measure.

3. Our passwords are designed to give you security. Really? How many passwords do you have now? How many offices have you been where people keep their secure passwords on post-it notes above their screen?

I was 55 last week, so this may be may age speaking, but I find the reliance on passwords increasingly irritating. I have to juggle six of them just to get into my two children's homework. Of course, we need to keep identities secure, but there is a limit - and once you make passwords complex enough to keep you safe, then you increasingly need to write them down and render them insecure.

I offer this up as another Boyle's Law.

What I find especially irritating is that all the organisations we all deal with assume that they are the only one we deal with in the world. In fact, every store, service, quango and government department we use loads us down with more passwords and usernames.

It isn't sensible to use the same password for every organisation - and I don't - but I have recently been refusing to accept new passwords (from the bank and the tax credits megalith) and feel better every time.

They always sound a little hurt, but it doesn't seem to make any difference to accessing them. Of course it goes onto your records...

Published on May 27, 2013 11:41

May 24, 2013

Outrage in the local currency world

Ever since 1992, when I saw green dollars in action in New Zealand, I’ve been fascinated by the idea that we should be able to conjure money out of nothing, by using our social networks.

My complementary currency heydays are now behind me but, during the 1990s, I found that I had got to know almost everyone involved in the idea of new kinds of money in the world – from Michael Linton in Canada (LETS and Community Way) to Heloise Primavera in Argentina (Global Barter Clubs).

I still think these ideas are important, and especially now that the Eurozone is grinding to a halt because big single currencies don’t work very well – they share the same fantasies as the gold standard, that money values are objectively real.

What Greece, Italy and Spain urgently need to do is to organise a range of regional currencies to operate alongside the euro to solve the basic problem – lots of people wanting to work, lots of work to be done, but no means of exchange to bring the two sides together.

But that’s another story. The complementary currency story has moved on somewhat since those days, thanks to bitcoin for the internet and time banks in public services, and my colleagues at the New Economics Foundation are in the midst of a fascinating pan-European project bringing together some of the most innovative new projects (ccia)

But the currency world has been thrown into some disorder by an important article in an academic journal called, of all things, Journal of Cleaner Production, which reviews all the evidence and says they don’t work.

It urges reformers to abandon the idea and concentrate instead on changing the way conventional money is created (97 per cent of it is now created in the form of loans by banks).

Well, having looked at the article, I’m not sure the argument is so clear cut, for the following reasons:

1. The author (Kristopher Dittmer) only looks at the prevailing models, like LETS and the German regional currencies, and these are only in the early stages of development.

2. He acknowledges the role that time banks play in rebuilding social networks, and points out that they don’t rebuild local economies – which they are really not designed to do anyway.

3. He doesn’t look at the new generation of complementary currencies emerging from Latin America, which concentrate on poverty reduction by supporting small enterprises.

This is important because, as the eminence gris of the movement Bernard Lietaer (one of the original designers of the euro) says, what we really need to do is to experiment with city regional currencies that can provide loans for productive enterprise.

This is what the network of community banks do in Brazil, and they now – rather unexpectedly – have the enthusiastic support of the Brazilian central bank. That is what the new currency started by French Prime Minister Jean-Marc Ayrault will do in Nantes.

I could say more, but I don't wnat to try the patience of my readers (if there are any). But the issue here is not whether we are going into a multi-currency world rather than a single currnecy one – bitcoin and Facebook will see to that.

The issue is whether we can, at a local or regional level, create our own money - and provide productive loans in it - to claw our own way out of recession. And I think we can.

My complementary currency heydays are now behind me but, during the 1990s, I found that I had got to know almost everyone involved in the idea of new kinds of money in the world – from Michael Linton in Canada (LETS and Community Way) to Heloise Primavera in Argentina (Global Barter Clubs).

I still think these ideas are important, and especially now that the Eurozone is grinding to a halt because big single currencies don’t work very well – they share the same fantasies as the gold standard, that money values are objectively real.

What Greece, Italy and Spain urgently need to do is to organise a range of regional currencies to operate alongside the euro to solve the basic problem – lots of people wanting to work, lots of work to be done, but no means of exchange to bring the two sides together.

But that’s another story. The complementary currency story has moved on somewhat since those days, thanks to bitcoin for the internet and time banks in public services, and my colleagues at the New Economics Foundation are in the midst of a fascinating pan-European project bringing together some of the most innovative new projects (ccia)

But the currency world has been thrown into some disorder by an important article in an academic journal called, of all things, Journal of Cleaner Production, which reviews all the evidence and says they don’t work.

It urges reformers to abandon the idea and concentrate instead on changing the way conventional money is created (97 per cent of it is now created in the form of loans by banks).

Well, having looked at the article, I’m not sure the argument is so clear cut, for the following reasons:

1. The author (Kristopher Dittmer) only looks at the prevailing models, like LETS and the German regional currencies, and these are only in the early stages of development.

2. He acknowledges the role that time banks play in rebuilding social networks, and points out that they don’t rebuild local economies – which they are really not designed to do anyway.

3. He doesn’t look at the new generation of complementary currencies emerging from Latin America, which concentrate on poverty reduction by supporting small enterprises.

This is important because, as the eminence gris of the movement Bernard Lietaer (one of the original designers of the euro) says, what we really need to do is to experiment with city regional currencies that can provide loans for productive enterprise.

This is what the network of community banks do in Brazil, and they now – rather unexpectedly – have the enthusiastic support of the Brazilian central bank. That is what the new currency started by French Prime Minister Jean-Marc Ayrault will do in Nantes.

I could say more, but I don't wnat to try the patience of my readers (if there are any). But the issue here is not whether we are going into a multi-currency world rather than a single currnecy one – bitcoin and Facebook will see to that.

The issue is whether we can, at a local or regional level, create our own money - and provide productive loans in it - to claw our own way out of recession. And I think we can.

Published on May 24, 2013 01:17

May 23, 2013

Why aren't homes being built? Because we can't afford them

Well, isn’t it extraordinary. The IMF just went ahead with their advice to the UK government without even reading my blog about house prices. Can you believe it?

There they were advising George Osborne to kickstart the economy (I might have told him that), with an early start to infrastructure projects, schools building and similar.

But then they fell into the usual mistake about house prices. Barriers to construction must be removed or the Help to Buy scheme will simply boost prices. As I explained earlier, it isn’t barriers to construction that are boosting house prices – or even the housing shortage (though it doesn’t help) – it is too much money in property.

As much as 70 per cent of UK bank lending goes on property projects, and every pound stokes up the next bubble and unbalances the economy even more disastrously.

The real reason why there are 400,000 outstanding planning permissions for housing units is not because there are barriers to planning or to building homes – it is that people can’t afford them.

And here is the problem. When speculation and bonuses push up the price of homes beyond the ordinary middle classes, then prices will rise, but homes will remain unbuilt outside London and the south east.

If society becomes so unequal that the majority can’t take part in normal life, even normal middle class life (as I said in my new book Broke ) then the economy begins to seize up.

What happens is that the economy adapts, and this is the scary part. It changes so that the opportunities only require rich people to take them up. It isn't just the socially excluded who get excluded them, it is the previously affluent middle classes too.

As yourself why so many of the great British brands are luxury brands which most people can't afford - from Aga and Aston Martin to Burbery, Barbour and Bentley (why are they just As and Bs too?). Because the UK economy isn't for the likes of us any more. It's for the mega-rich. We exist on the crumbs that fall from their table.

There they were advising George Osborne to kickstart the economy (I might have told him that), with an early start to infrastructure projects, schools building and similar.

But then they fell into the usual mistake about house prices. Barriers to construction must be removed or the Help to Buy scheme will simply boost prices. As I explained earlier, it isn’t barriers to construction that are boosting house prices – or even the housing shortage (though it doesn’t help) – it is too much money in property.

As much as 70 per cent of UK bank lending goes on property projects, and every pound stokes up the next bubble and unbalances the economy even more disastrously.

The real reason why there are 400,000 outstanding planning permissions for housing units is not because there are barriers to planning or to building homes – it is that people can’t afford them.

And here is the problem. When speculation and bonuses push up the price of homes beyond the ordinary middle classes, then prices will rise, but homes will remain unbuilt outside London and the south east.

If society becomes so unequal that the majority can’t take part in normal life, even normal middle class life (as I said in my new book Broke ) then the economy begins to seize up.

What happens is that the economy adapts, and this is the scary part. It changes so that the opportunities only require rich people to take them up. It isn't just the socially excluded who get excluded them, it is the previously affluent middle classes too.

As yourself why so many of the great British brands are luxury brands which most people can't afford - from Aga and Aston Martin to Burbery, Barbour and Bentley (why are they just As and Bs too?). Because the UK economy isn't for the likes of us any more. It's for the mega-rich. We exist on the crumbs that fall from their table.

Published on May 23, 2013 05:51

May 22, 2013

Why is a Tory Chancellor skewering the middle class?

Since I work for myself, I don't often put myself onto London streets before 9am at the earliest - and I am certainly not mad enough to drive. The whole business of driving inside London in the working day reminds me of the mythical frog in the frying pan.

Since I work for myself, I don't often put myself onto London streets before 9am at the earliest - and I am certainly not mad enough to drive. The whole business of driving inside London in the working day reminds me of the mythical frog in the frying pan.I have no idea if frogs will actually fry if the heat increases slowly, but London traffic seems to fit into this metaphor. Wasting time in jams that would be quite unacceptable if we met them for the first time, just gets lazily accepted because they increase slowly.

Which is basically what I think about house prices, especially now that they are into acceleration mode again - with record prices in London, East Anglia and the south east. London prices up nearly ten per cent this year alone, with the average price in London over half a million pounds. Only two regions still have the good fortune to have falling prices.

My own home is a small semi worth just under half a million, which is ridiculous considering it cost about £800 when it was built in 1937, with a mortgage paid off in about 15 years, and costing about ten per cent of the average salary.

This is the ultimate frog-in-the-frying-pan phenomenon, and now boosted so egregiously by the government's Help to Buy scheme.

It happens slowly enough for the house-buying public not to notice what is happening - but the result is just the same. Government mistakes since 1980 are in the process of pricing the middle classes out of existence. I've explained whose fault this was in my new book Broke: Who Killed the Middle Classes , and the strange story of why it happened.

But what I find extraordinary is that a Conservative Chancellor can carry on the mistake - creating a property bubble, subjecting the lives of home-owners and rents to a lifetime of indentured servitude in jobs they don't want, just to pay the costs of a roof over their heads.

Why does he not see that making homes easier to buy at existing prices will push them up, and even further out of the reach of the next generation. There is only one way forward if there is to be another middle class generation, and that is to find ways to bring them slowly down.

Yes, there is an argument about why house prices rise, and why those prices accelerate. Politicians like to say that it is a shortage of homes, and there certainly is a shortage and it doesn’t help. But if it was only about housing shortage, you would expect massive price rises in the late 1940s, whereas – after a burst after the war – house prices stayed completely steady from 1949 to 1954. The graph of house price inflation follows the rise in mortgage lending.

In our own day, planning permission has already been given for 400,000 unbuilt homes in the UK, yet prices still rise, as they have done in places like Spain, where there is little or no planning restraint.

Politicians get muddled about this because building houses sounds like a tangible thing they feel confident to tackle (though they usually don’t), whereas they don’t feel confident about mortgage supply at all. Yet that is the other side of the process: inflation is about too much money chasing too few goods, and the main reason for the extraordinary rise is that there has been too much money in property, both from speculation and from far too much mortgage lending.

Sometimes this came from people’s rising incomes, which translated into rising home loans. Sometimes it was lenders lending on increasing multiples of salaries. Sometimes, more recently, it was bonuses and buy-to-let investors.

But most of the time, it has been a catastrophic failure to control the amount of money available to lend, and which has fed into all the other trends to create a tumbling cascade of finance, with its own upward pressure on incomes and debt until the vicious circle now seems quite unbreakable.

It was a roller coaster that terrified and thrilled the middle classes, as they saw the value of their homes rise so inexorably, but which is now undermining the very basis for their continued existence.

Amazing really that this process is continuing, as yet another government sacrifices the next generation to help this generation onto the housing ladder - and especially amazing that it is an admirer of Margaret Thatcher at the helm as it happens. No wonder UKIP is threatening the Tory heartlands.

Published on May 22, 2013 01:46

May 21, 2013

The secret history of helicopter money

If you really want to see a property bubble at work, then get into a time machine and go back to Tokyo in the late 1980s and early 1990s. It was a fearsome business, impoverishing more people than it enriched and funding Japan's aggressive business expansion around the world as the bubble inflated land prices.

Grandparent mortgages - paid off by the generation after next - and hugely expensive tiny sleeping tubes: that is what happens when property bubbles get out of control (so watch out, George).

They also eventually pop. Japan's zombie economy was the result, and all the slightly breathy excitement about 'recovery' in the UK rather ignores the likelihood that we are in the same zombie position as they are.

One radical Japanese solution has been what they call 'helicopter money', which is where the central bank or Treasury simply creates the money - the way it used to be done - and it is distributed straight into the economy to get demand moving. This is what Adair Turner has been advocating here, and there was a fascinating discussion posted yesterday between Turner and other economists which came to the conclusion that it was worth trying.

Now, here's the odd thing. Here are influential economists discussing the practicalities of helicopter money creation - but where are the politicians? It is as if they are somehow above the practical business of creating money, as if it was somehow impolite to discuss how this is normally done (the banks create it in the form of loans) and how it could be done.

It is as if politicians were the unreformed men who avert their eyes at the grubby business of household work - wiping bottoms, stenching blood, washing dishes, holding up the sky.

This matters, partly because politicians ought to discuss a practical solution to our difficulties. And partly because, if it isn't discussed - then how can the details be properly debated? For example, where should the new interest-free money go?

To the banks? We tried that with quantitative easing and they just sit on it, or use it to fund bonuses - which raises house prices.

To people directly? That is what they tried in Japan, and they just spent it by paying off debt.

To provide very low-interest loans to small businesses? We have no infrastructure capable of lending it locally - the banks have proved themselves unable to do so.

To the Green Investment Bank to provide very low-interest loans to sustainable energy infrastructure? Maybe, but would it have the economic impact?

To community banks and community development finance institutions? Experience in the USA suggests that they can use it effectively within about a month. But our CDFI network is probably too small still to take all of it.

Would it be inflationary? Yes, unless we also prevent banks from creating money (this is another discussion). But it matters very much how much work the new money could do before it creates inflation. Or, to put it another way, it only creates inflation when it reaches the rich. So it makes sense not to let it trickle down, but let it bubble up. Don't helicopter it; plant it.

The other odd thing is how faulty the economic history is around this forbidden, whispered aspect of economics. Commentators point out that Milton Friedman suggested something similar in 1948. He certainly did, but because he was still under the influence of the great American liberal Henry Symons - the doyenne of the original liberal Chicago school of economists.

The other history which is never mentioned is that we did all this in the UK once before, almost exactly a century ago, under the Chancellorship of David Lloyd George. At the outbreak of the First World War, and to avoid a run on the banks, Lloyd George issued £1 and 10 shilling notes direct from the Treasury and continued to do so until 1919.

The first ones were rushed out within days, printed on postage stamp paper and were known as 'Bradburys', after Sir John Bradbury whose signature appeared on the bottom.

There are huge conspiracy theories around all this, thanks - it seems to me - to the failure of mainstream economists to discuss the way that money is created. There was nothing very special about the banknotes, which simply mimicked Bank of England notes in smaller denominations. But it did set a precedent for the Treasury to create money directly, if necessary, and to do so free of interest.

Incidentally, if you want to know where money usually comes from, you could do worse than look at the new book by my colleagues from the New Economics Foundation, together with a preface by Sir Charles Goodhart, formerly of the Bank of England.

Published on May 21, 2013 02:43

May 20, 2013

Prevention is the word that will save the NHS

The influential NHS blogger Roy Lilley asks precisely the right question this morning. Why is the Accident and Emergency service not like the Fire Service?

If the incidence of fires has dropped by 40 per cent, and it has – as we know thanks the review by Sir Ken Knight – what can the NHS learn from that? The answer lies in the neglected word ‘prevention’. The Fire Service has been devoting increasing energy and ingenuity into preventing fires.

Partly the success is down to smoke alarms, which are now in 86 per cent of homes. Strictly speaking, this isn't prevention exactly, it is early detection – but it still helps.

As Lilley says, the real problem is people with Long Term Conditions, who account for 70 per cent of the costs of primary care. It so happens that the NHS is at its very least effective here, trying to maintain patients in their conditions at huge expense for the rest of their lives – rather than helping them find ways of managing and improving the conditions themselves (I write as someone with chronic eczema, when the mere thought of NHS dermatologists now makes my skin creep).

I’ve written about this before, and regular readers (if there are any) will know that there are lessons to be learned from:

Flexibility, and the power that patients have to vary the way they are treated and the arrangements around that, as I said in my review on barriers to choice. Co-production: the People-Powered Health project at Nesta calculates that this aspect of self-care and mutual support would save the NHS at least £4.4 billion, and may save as much of a fifth of the cost of treating long-term conditions.System thinking, and the way that the public services need to be seen as a whole system rather than an alphabet soup of overlapping and conflicting jurisdictions. But here lies the real difficulty and the real reason why the Fire Service is different from the NHS. The Fire Service is vertically integrated and is the only agency that deals with putting out fires, while navigating the health an social care system is a full-time job in itself.

That means that investing in effective innovation in one area of public health will accrue to somebody else’s budget. It is a recipe for waste and stagnation.

Now, say what you like about the health reforms – and I have – but putting the doctors and local authorities in charge of paying for the NHS (the new CCGs) does provide a structure that has some motivation for innovating.

The trouble is that they can still load all the costs on the local foundation trust's A&E service. We also need to find ways that the big hospitals can reach out into the neighbourhood and stem some of the demand that floods through in ill-health – and this is a perfect project for hospitals and CCGs combined. Both need to invest and both stand to gain.

Either way, prevention has to be the new buzzword in public services. It is the pathway to a solution to rising costs and struggling effectiveness – but it means structuring the system so that it is flexible.

If the incidence of fires has dropped by 40 per cent, and it has – as we know thanks the review by Sir Ken Knight – what can the NHS learn from that? The answer lies in the neglected word ‘prevention’. The Fire Service has been devoting increasing energy and ingenuity into preventing fires.

Partly the success is down to smoke alarms, which are now in 86 per cent of homes. Strictly speaking, this isn't prevention exactly, it is early detection – but it still helps.

As Lilley says, the real problem is people with Long Term Conditions, who account for 70 per cent of the costs of primary care. It so happens that the NHS is at its very least effective here, trying to maintain patients in their conditions at huge expense for the rest of their lives – rather than helping them find ways of managing and improving the conditions themselves (I write as someone with chronic eczema, when the mere thought of NHS dermatologists now makes my skin creep).

I’ve written about this before, and regular readers (if there are any) will know that there are lessons to be learned from:

Flexibility, and the power that patients have to vary the way they are treated and the arrangements around that, as I said in my review on barriers to choice. Co-production: the People-Powered Health project at Nesta calculates that this aspect of self-care and mutual support would save the NHS at least £4.4 billion, and may save as much of a fifth of the cost of treating long-term conditions.System thinking, and the way that the public services need to be seen as a whole system rather than an alphabet soup of overlapping and conflicting jurisdictions. But here lies the real difficulty and the real reason why the Fire Service is different from the NHS. The Fire Service is vertically integrated and is the only agency that deals with putting out fires, while navigating the health an social care system is a full-time job in itself.

That means that investing in effective innovation in one area of public health will accrue to somebody else’s budget. It is a recipe for waste and stagnation.

Now, say what you like about the health reforms – and I have – but putting the doctors and local authorities in charge of paying for the NHS (the new CCGs) does provide a structure that has some motivation for innovating.

The trouble is that they can still load all the costs on the local foundation trust's A&E service. We also need to find ways that the big hospitals can reach out into the neighbourhood and stem some of the demand that floods through in ill-health – and this is a perfect project for hospitals and CCGs combined. Both need to invest and both stand to gain.

Either way, prevention has to be the new buzzword in public services. It is the pathway to a solution to rising costs and struggling effectiveness – but it means structuring the system so that it is flexible.

Published on May 20, 2013 02:58

May 19, 2013

Cuckoos and the economics of orchards

Years ago, I interviewed the former economics adviser to the Jersey government for the New Statesman, and he explained to me how the island's tax haven status had been like a cuckoo in the nest.

Years ago, I interviewed the former economics adviser to the Jersey government for the New Statesman, and he explained to me how the island's tax haven status had been like a cuckoo in the nest. Financial services are so profitable (and I might add, so safe - you can get bailed out) that other forms of enterprise become economic. First the agriculture runs down, then the tourism, then - with over 500 banks on the island - nobody else can afford a home. It is the same process that is happening, much more slowly, in London.

But there was a story in the Evening Standard this week which made me realise that there are the other forces working in the same direction - monopolistic supermarkets making small farming uneconomic, competing with Chinese wages and Far Eastern-style employment standards. The result is the bizarre story that de-regulating migrant Bulgarian and Romanian workers in the UK could lead to the end of British orchards.

This was what the Home Office Migration Advisory Committee told Home Secretary Theresa May. The idea is that the migrant workers will be able to work elsewhere in the UK economy shortly, and will abandon fruit-picking. Prices will rise, the supermarkets will reject UK fruit, and there go the apple orchards.

It is tempting to ask who picked the fruit before the Bulgarians came to do it a few years ago, but there is a deeper problem than this. It means that supermarkets are using their semi-monopoly position to force fruit producers into lower than economic prices - just as they have done with milk.

But there is a bigger issue too. What else can't we afford to do in the UK? We can't afford to train many of the staff in the NHS, which is staffed by recruiting direct from training colleges in developing countries. Now, apparently, we can't imagine how we might use our existing orchards to grow fruit - except by importing the poor and desperate to do it for us?

The cuckoo in the nest syndrome again. It isn't what I would call the 'balanced economy' that the coalition promised in 2010. Nor is it the kind of economy that spreads the benefits much further than financial services.

And what will become uneconomic for us next? Growing wheat? Making screws? Making ships has pretty much disappeared already.

And all because monopoly power undermines realistic pricing. That, and a fetishistic over-emphasis on the doctrine of comparative advantage, which suggests that - because we have banks and speculators - it isn't worth doing anything else. If the British Disease used to be poor management and the closed shop, it is now the way our rulers cling to speculation and financial services as if it could feed us.

Well, I for one will continue to eat local fruit - and if the supermarkets can't stock it, I will be buying it elsewhere. The fact there is now an elsewhere, in the burgeoning local food movement, is one of the hopes for the economy and the future.

Published on May 19, 2013 04:51

May 18, 2013

Call centre menus: reach for your hatchet

During his research into the ruthless side of the modern economy, the journalist Simon Head discovered a fascinating paper, published in 1997, about a customer relationship management IT system in action.

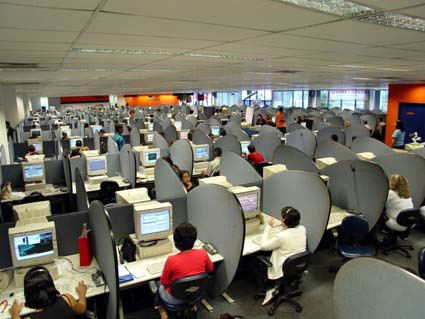

It was written by two researchers at Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Centre in Silicon Valley, and they describe a corporation called MMR, a thinly disguised version of Xerox, and their IT system called CasePoint, which was designed to automate the conversations between customers and agents. The idea was to cut the cost of sending technicians out to repair Xerox machines. It would all be done automatically by call centre staff over the phone.

CasePoint didn’t work. Call centre staff were supposed to take down exactly what the customers said and the system would feed it to the experts to come up with solutions. The call centre staff were only allowed to ask questions exactly as they were worded on the screen.

The trouble was, when it came to the point, the customers used ‘unauthorised’ language of their own which the system couldn’t understand. By the end of the trial period, the researchers couldn’t find one example where CasePoint had done its job properly. That is what tends to happen when human beings are excluded from systems.

The trouble was that, when the managers and software designers were told this, they decided it was an irrelevant detail and that they should carry on with the system regardless. They wanted to see how far they would rely “exclusively on machine expertise as a substitute for agent knowledge”. The answer was: not very far.

This is the dream of IT consultants: a machine that can have a conversation with a human being without them knowing they are talking to a computer. In fact, most people who have been phoned by a computer will tell you that, the more like a human being the machine is, the more unnerving the experience.

Computers show little signs that they will ever be able to confront a human personality with their own. Maybe they will one day, but I doubt it: all they can do is to fake a personality, usually with some marketing or processing intent. Until they go beyond this into genuine artificial intelligence, their failure to do so can only be hugely expensive.

CasePoint is an extreme example of what happens when IT takes over functions it shouldn’t, where it deliberately excludes closer human contact. More about this in my book The Human Element.

But it is also an example of the great unchallenged nonsense of a 'shared back office' service. The key assumption is that customer-facing systems can be automated entirely - what the government calls 'digital by default'. It also assumes that untrained system operators will just service requests, find a place for each query on the software, and hand it back to automated back office systems - or, failing that, experts.

There is very little evidence that this idea, embraced by government and consultants alike, saves money. Of course automation often seems to save money, but consultants very rarely subtract - so they fail to see the diseconomies of scale until it is too late.

Only when the costs mount, as the systems thinker John Seddon explains, does anyone wonder (and often they don't even then) whether the automation has made the system frustrating and inflexible, and therefore wasteful - because some people have to come back again and again (what Seddon calls 'failure demand').

And the most obvious times when we encounter this phenomenon is the 'Press button 2' syndrome. Which is why the story of the retired IT manager timing each stage through different call centres is so fascinating - six minutes for each of the four levels at HM Revenue and Customs.

But what really amazed me about the story was what he said:

"In an ideal world, he said, companies should just offer different phone numbers for different services."Isn't that what we had only a few years ago? There is a good reason why we don't - because people's queries often don't fit the boundaries set down (as we find so often pushing buttons).

I even remember Simon Hughes' campaign for the London mayor proposed 'One Number for London' as its main policy demand - about the least exciting political demand I have ever come across. If he had won, and the One Number was up and running - how many different options would people have to go through now?

No, it only works if there is a human being, sensible, flexible and empowered enough to make things happen, at the other end. That requires IT support at their end, not push buttons at our end.

Because, after all, as C. S. Lewis put it, in the mouth of Mr Beaver: "Take my advice. When you meet anything that's going to be human and isn't yet, or used to be human and isn't now, or ought to be human and isn't, you keep your eyes on it and feel for your hatchet."

Published on May 18, 2013 03:43

David Boyle's Blog

- David Boyle's profile

- 53 followers

David Boyle isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.