Roy Christopher's Blog, page 14

May 22, 2022

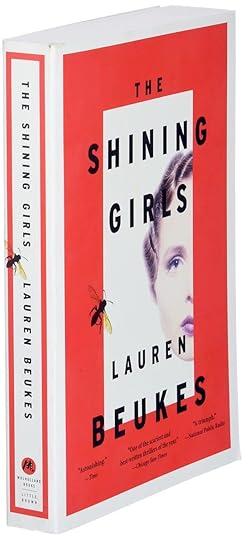

Shining Girls' Tangled Timeline of Transgression

Harper’s havoc reaches roughly from the 1930s to the 1950s and the 1990s. It’s a tangled mess of totems, trauma, and one who got away. As Harper puts it, "There are patterns because we try to find them. A desperate attempt at order because we can’t face the terror that it might all be random." Beukes had her own method, mess, and snapshots to deal with while writing. She had a murderous map, full of "crazy pictures, three different timelines, murder dates…" She told WIRED UK, "It’s been completely insane trying to keep track of all of this."

The Shining Girls is set in my former home of Chicago, which gave me both a history lesson and a feeling of familiarity. The differences among the decades in the story are as interesting as the use of usual local terms like “Red Line,” “Wacker Drive,” “Merchandise Mart,” and “Naked Raygun,” the latter thanks to the one that got away, the spunky, punky Kirby Mazrachi. The book is one part murder mystery, one part detective story, one part science fiction, and another part love story, but it’s all subtle, supple, and masterfully handled.

The Jesus Lizard gets name-dropped in the very first episode of the series. Unlike some of my other favorite books that have made it to the screen in recent years, the Shining Girls adaptation is apt, telling the story in a new way while remaining true to its spirit. Believable time travel is weirdly easier to manage on the page, but the show eases it in, only subtilely hinting at it early on. It's not an overt element of the story until episode six, when we're shown the house's powers full-blown.

1993 is the latest year Harper’s house will go. That’s also the year that Michael Silverblatt of the Los Angeles Times coined the term “transgressive fiction,” a term that aptly describes Beukes’ novel. Silverblatt used the term to describe fiction that includes “unpleasant” content such as sex, drugs, and violence, and coined it in response to the censor-baiting controversy of American Psycho by Bret Easton Ellis (Vintage, 1991), Patrick Bateman’s nearly choked conduit into the world. In Transgressive Fiction: The New Satiric Tradition (Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), Robin Mookerjee discusses Ellis, as well as many other literary forebears of Beukes and The Shining Girls. From mock epics like Ovid’s Metamorphoses and Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels to the perversions of J. G. Ballard and Nabokov to the cut-ups and borrowing of William Burroughs and Kathy Acker, on up to contemporary deviants like Chuck Palahniuk, Irvine Welsh, and Ellis, of course. Mookerjee discusses these writers’ novels through the Menippean mode of satire, in which the transgression is total rather than individual, a literary style that “opposes everything and proposes nothing,” as Mookerjee puts it. For instance, in American Psycho, whether Bateman is brushing his teeth or slicing up some hired young thing, his tone never changes. The effect is indirect, general not specific, and pervades the book’s ontology as a whole.

And so it is with the Shining Girls TV show, like its source novel: an eerie portrayal of transgression, trauma, and truth.

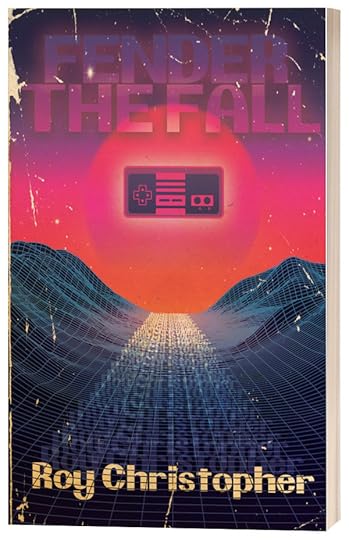

You Don’t Know What You’ve Got Until You Get It Back.My own sci-fi novella, Fender the Fall, is also a time-travel love story. Chris Bridges, a lovelorn physics graduate student who goes back in time to return the journal of his high-school crush in order to save his marriage and her life. The plan doesn’t go as planned.

It’s available from Alien Buddha Press! It’s 5”x8” and 136-pages long, like a good paperback should be. It’s the perfect weekend read.

I was fortunate enough to get Matthew Revert to design the cover and Mike Corrao to do the typesetting. As a result, it’s a sharp-looking little book.

Here’s what other people are saying about it:

“A fun, classic roller-coaster of a time-travel story that could have been published in the 1950s, except that it’s furnished with all manner of savvy insights into current 2020s life.” — Paul Levinson, author of The Plot to Save Socrates

“Fender the Fall is a nostalgia-infused journey through time about second chances and the causality of love. It’s a formative song from your youth revisited, a favorite VHS tape found in the back of your closet.” – Joshua Chaplinsky, author of The Paradox Twins

“Hard-boiled strange loops in a froth of weird.” – Will Wiles, author of Plume

Many thanks to Matt Revert and Mike Corrao for making this thing look so good; Red Focks for putting it out there; Paul Levinson, Josh Chaplinsky, Will Wiles, Jaqi Furback, Gabriel Hart, C.W. Blackwell, Ira Rat, J. Matthew Youngmark, and Jeph Porter for their time, feedback, and kind words; and Claire Putney, from whom I stole the title.

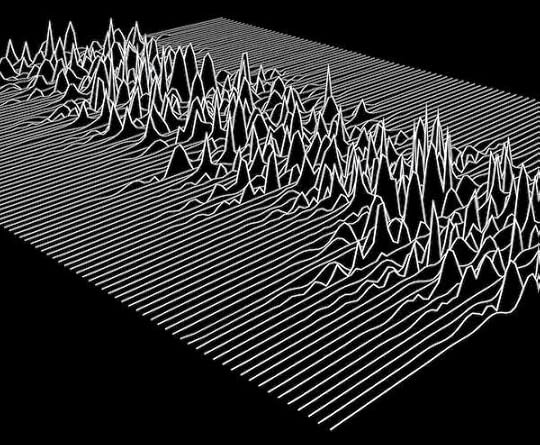

Here’s a soundtrack I put together while writing Fender the Fall. It has songs mostly from and around the years in the story (2002 and 1991).

Order your copy of this lovely, little paperback from Alien Buddha Press now! You won’t regret it.

Thank you for your time and attention, and for reading, responding, and sharing.

More soon,

-royc.

May 3, 2022

Generation X was a Band

If you were looking to get Cliff's Notes for the 1980s in musical form, you'd be hard pressed to find a better exemplar than Sigue Sigue Sputnik's 1986 debut, Flaunt It! Tony James described them as "hi-tech sex, designer violence and the fifth generation of rock and roll." A product of punk in the same way that Big Audio Dynamite and Devo were, their techno-pop sound was laced with samples from movies and media. Even after all of the work Trevor Horn had done defining a new sound for the decade, Sigue Sigue Sputnik was still exciting. At the time, for better or worse, they sounded like the future. In a move of unfortunate prescience, the band sold brief advertisements that played between the songs on the record. Ones for i-D magazine and Studio Line from L’Oréal share space with fake ones for The Sputnik Corporation and a Sputnik video game that never materialized. James touted the spots as commercial honesty, adding, "our records sounded like adverts anyway." Where the punk that preceded them railed against the dominant culture, Sputnik was out to to mirror it, to consume it, to corrode it from the inside. To interpolate an old Pat Cadigan story, the former was trying to kill it, the latter to eat it alive.

It would take Billy Idol a decade to embrace technology in the cyberpunk fashion that Sigue Sigue Sputnik had done in the 1980s. The reaction to Idol's 1993 concept record, titled simply Cyberpunk, is perhaps the best example of competing gen-X attitudes. The Information Superhighway, as it was often called at the time, was just making inroads into homes around the world, and its technology-based, cyberpunk, D.I.Y. influence was also creeping into the culture at large. In his 1996 book Escape Velocity: Cyberculture at the End of the Century, Mark Dery describes Idol's Cyberpunk as "a bald-faced appropriation of every cyberpunk cliché that wasn't nailed down" (p. 76). In contrast, our friends and O.G. cyberpunks themselves Gareth Branwyn and Mark Frauenfelder consulted Idol and were involved in various aspects of the record's release.

One of the unspoken yet central tensions among members of generation X is this idea of cultural ownership. It's the old battle of the underground versus the mainstream, but it's also the desire to introduce one to the other, to be the one who shepherds something from subcultural obscurity to mainstream success. We might be the last generation to feel these contradictions of capitalism. We might be the last generation for whom the concepts of underground and mainstream have any real meaning. The terms are still in use, but they don't denote the divisions of marketshare they once did.

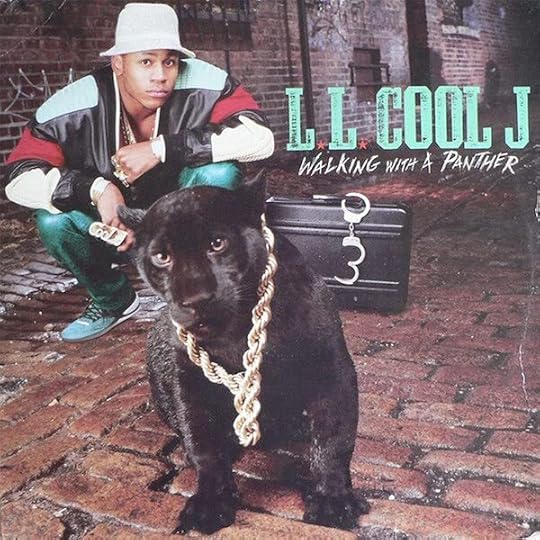

In another example of this cultural shift, LL Cool J came to fame in the mid 1980s with the Rick Rubin-produced records Radio in 1985 and Bigger and Deffer in 1987. The scrappy rawness of the young Cool J's raps over Rubin's reductive production proved irresistible to both the streets and the charts. By the time he released Walking with a Panther in 1989, Cool J was rich. Though the record sold well, it also suffered a backlash. The gen-X led hip-hop community was nonplussed by the overt materialism. Ten years later, during the Big Willie era, conspicuous consumption was one of the prevailing modes of hip-hop culture. From Nas to Biggie to Jay-Z, the contradictions of capitalism were on display, and only the underground was complaining (As I wrote previously, this same shift happened in skateboarding as it grew bigger than ever before during the 1990s).

We rebelled against our parents like every generation does, but the unified nature of that rebellion is a thing of the past. The 1980s were the mainstream's last stand. With the 24-hour news cycle and the spread of the internet, any sort of monolithic pop culture began splintering irrevocably in the 1990s. Sigue Sigue Sputnik's slogan was "fleece the world," and while they railed against it all in 1976, the their punk predecessors the Sex Pistols reunited twenty years later, citing "your money" as the sole reason. These ideas were still somewhat shocking at the respective times, but now they seem downright quaint.

YOU GUESSED IT!This is another brief excerpt from my book-in-progress, The Medium Picture. It's up on the book's website without all of this stuff under it, if you'd like to share it. :)

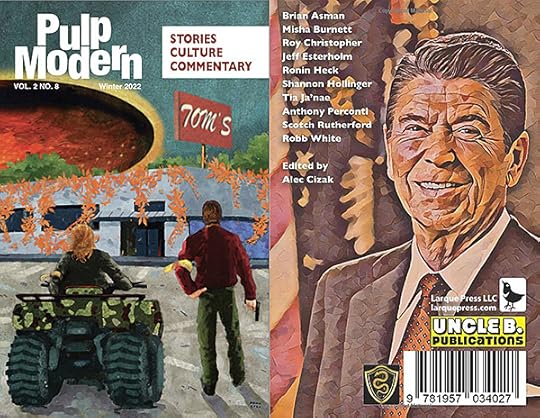

DIFFERENT WAVES, DIFFERENT DEPTHS:Quick announcement: I have just signed a contract with Uncle B. Publications to publish a collection of my short stories called Different Waves, Different Depths to be released in December. I am really excited! I've been wanting to put one of these together for a long time, and I finally have the stories and a home for them. I'm working on securing the cover art and laying out a few of the stories myself. Many thanks to Alec Cizak for believing in these stories and apologies to The Little One, Michelle Andino, from whom I stole the title.

Updates to follow!

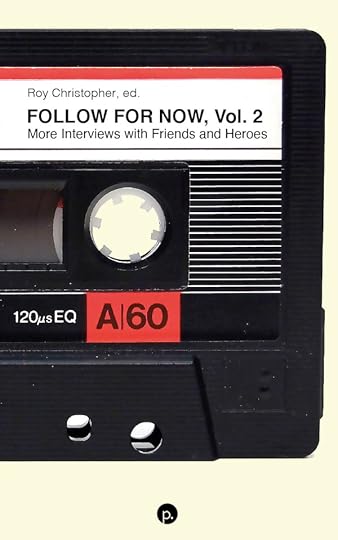

MORE INTERVIEWS WITH FRIENDS AND HEROES:My interview anthology, Follow for Now, Vol. 2 picks up and pushes beyond the first volume with a more diverse set of interviewees and interviews. The intent of the first collection was to bring together voices from across disciplines, to cross-pollinate ideas. At the time, social media wasn’t crisscrossing all of the lines and categories held a bit more sway. Volume 2 aims not only to pick up where Follow for Now left off but also to tighten its approach with deeper subjects and more timely interviews. This one is a bit more focused and goes a bit deeper than the last. It includes several firsts, a few lasts, and is fully illustrated with portraits of every interviewee.

“Relentlessly stimulating and insight-packed, Follow for Now is the kind of book I’d like to see published every decade, and devoured every subsequent decade, from now until the end of humanity.” — Maria Popova, Brain Pickings

The interviewees include Carla Nappi, Kristen Gallerneaux, Dominic Pettman, Rita Raley, Jodi Dean (by Alfie Bowne), Gareth Branwyn, Ian Bogost, Mark Dery, Brian Eno (by Steven Johnson), Zizi Papacharissi, Douglas Rushkoff, danah boyd, Dave Allen, Juice Aleem, Labtekwon, M. Sayyid from Antipop Consortium, Ish Butler from Shabazz Palaces, dälek, Matthew Shipp, Tyler, The Creator (by Timothy Baker), Tricia Rose, Sean Price, Rammellzee (by Chuck Galli), Cadence Weapon, El-P of Run the Jewels, Sadat X, Ytasha L. Womack, Bob Stephenson, Pat Cadigan, Mish Barber-Way, Chris Kraus, Simon Critchley (by Alfie Bown), Clay Tarver, Nick Harkaway, Simon Reynolds (with Alex Burns), Malcolm Gladwell, and William Gibson (by Kodwo Eshun).

Thirty-seven interviews deep, Follow for Now, Vol. 2 is a hefty collection of ideas and inspiration from some of the most important writers, artists, and thinkers of our time. It includes the first ever interview with Tyler, The Creator, one of the last with Rammellzee, and a lengthy discussion between William Gibson and Kodwo Eshun caps it all off.

Get yourself a pretty paperback or an open-access .pdf from punctum books!

Thank you for your time and attention, and for reading, responding, and sharing. You are appreciated.

More soon,

-royc.

April 18, 2022

Booty from the Bargain Bin

Our discretionary budgets back then were small, and cassettes cost around $10, while CDs were closer to $17. I remember the music industry titans at the time promising that the CD would soon cost the same as a tape, promising a cheaper CD. Instead, CDs stayed the same and the tape eventually edged upwards. LPs were all but gone with fewer and fewer new releases even appearing in the format.

Prohibitive pricing notwithstanding, buying music was always a risk. We might have heard a song or two from a friend or seen a late-night video, but most of what one might buy was unheard, a mystery that could turn out to be quite disappointing. I never knew when I was going to have enough money to buy another record, so in the event that I had money for a record in the first place, I had to hope whatever I was buying was good.

My friend Matt Bailie and I met through music in the ninth grade. He was talking about the first Metal Church record that had just come out, and I was spreading the gospel of Oingo Boingo. Every weekend we'd convene at his house to watch Headbanger's Ball on Saturday nights because the videos on that show represented "his" music and 120 Minutes on Sunday nights because it represented "my" music. For the most part, we hated everything they played on both shows, but once in a while there would be an old favorite, and less often, there would be something new we were into. More often than any other slot on the show, the last video on 120 Minutes was that new thing. I'd endure the whole two hours just to see what that last video would be. That's where I first heard songs by Pegboy, Primus, and Stone Roses.

Then as now, retail space in record stores is precious. Product has to move. If it's not moving, it gets extra incentive to do so. This means bargain bins. Typically located close to the front of the store, these displays were piled with releases the record labels were unloading at a discount or whatever stock the store needed to get rid of. A tape or LP at a fraction of the suggested retail price was too good to pass up. Subsequently I found many lifelong loves in those racks. Well known staples like Naked Raygun, The Jesus and Mary Chain, and Gang of Four were joined by lesser-known acts like Abecedarians, Devlins, and Bleached Black. These were complemented by cassette dubs, mixes from friends near and far, and the occasional full-price splurge on a new release. It was a weird blend of sounds, idiosyncratic in its breadth and fickle in its focus.

We knew so little about the bands we liked and less about the ones we didn't. We were starved for information. When I listen to new music now, I try to get back into the mind I had then. I try to listen to it for what it is--not completely without context, but with more of an ear for the sound than the discourse around the sound.

And I still check the bargain bins at every record store I go to, just in case.

MORE INTERVIEWS WITH FRIENDS AND HEROES:My interview anthology, Follow for Now, Vol. 2 picks up and pushes beyond the first volume with a more diverse set of interviewees and interviews. The intent of the first collection was to bring together voices from across disciplines, to cross-pollinate ideas. At the time, social media wasn’t crisscrossing all of the lines and categories held a bit more sway. Volume 2 aims not only to pick up where Follow for Now left off but also to tighten its approach with deeper subjects and more timely interviews. This one is a bit more focused and goes a bit deeper than the last. It includes several firsts, a few lasts, and is fully illustrated with portraits of every interviewee.

“Relentlessly stimulating and insight-packed, Follow for Now is the kind of book I’d like to see published every decade, and devoured every subsequent decade, from now until the end of humanity.” — Maria Popova, Brain Pickings

The interviewees include Carla Nappi, Kristen Gallerneaux, Dominic Pettman, Rita Raley, Jodi Dean (by Alfie Bowne), Gareth Branwyn, Ian Bogost, Mark Dery, Brian Eno (by Steven Johnson), Zizi Papacharissi, Douglas Rushkoff, danah boyd, Dave Allen, Juice Aleem, Labtekwon, M. Sayyid from Antipop Consortium, Ish Butler from Shabazz Palaces, dälek, Matthew Shipp, Tyler, The Creator (by Timothy Baker), Tricia Rose, Sean Price, Rammellzee (by Chuck Galli), Cadence Weapon, El-P of Run the Jewels, Sadat X, Ytasha L. Womack, Bob Stephenson, Pat Cadigan, Mish Barber-Way, Chris Kraus, Simon Critchley (by Alfie Bown), Clay Tarver, Nick Harkaway, Simon Reynolds (with Alex Burns), Malcolm Gladwell, and William Gibson (by Kodwo Eshun).

Thirty-seven interviews deep, Follow for Now, Vol. 2 is a hefty collection of ideas and inspiration from some of the most important writers, artists, and thinkers of our time. It includes the first ever interview with Tyler, The Creator, one of the last with Rammellzee, and a lengthy discussion between William Gibson and Kodwo Eshun caps it all off.

Get yourself a pretty paperback or an open-access .pdf from punctum books!

Thank you for your time and attention, and for reading, responding, and sharing.

More soon,

-royc.

April 6, 2022

Friendship and the Deleuzian Delusion

Assemblages, rhizomes, bodies-without-organs, repetition, difference… I can’t claim to have an answer to Bogost’s question, as I can’t claim to understand much of the Deleuze that I’ve read (and I’ve read a lot of it, and a lot of it more than twice). I do know that a lot of it is difficult simply by dint of the contrarian angle on subjectivity: These books challenge the fundamental way(s) most of us tend to feel that being in the world works. Eugene Holland opens his 1999 book, Deleuze and Guattari’s Anti-Oedipus: Introduction to Schizoanalysis, with the obvious statement: “The Anti-Oedipus is not easy to read.” Regarding writing it with his coauthor, Deleuze said, “Between Félix and his diagrams and me with my verbal concepts, we wanted to work together, but we didn’t know how.” And about A Thousand Plateaus, he mused, “Now we didn’t think for a minute of writing a madman’s book, but we did write a book in which you no longer know, or need to know, who is speaking…” On page 22 of the latter, they even write it out, in black and white: “We are writing this book as a rhizome. It is compose of plateaus. We have given it a circular form, but only for laughs.” How is one to make sense of bastard philosophy such as this?

I once asked my friend and mentor Steven Shaviro what path to take as I embarked upon the plateaus alone for the first time. He suggested using Claire Parnet’s Dialogues as a sort of crib notes to the two major volumes mentioned above. Dialogues was compiled between the writing of Anti-Oedipus and A Thousand Plateaus. Deleuze talked about the book’s in-betweenness. That is, its being between both the two books and the three authors, writing that what mattered was “the collection of bifurcating, divergent, and muddled lines which constituted this book as a multiplicity and which passed between the points, carrying them along without going from one to the other.” And so it goes.

Many others have tried to make sense of Deleuze, with various tropes and varying degrees of success. Gregory Flaxman has faired better than most. Flaxman is not new to Deleuze: his book The Brain is the Screen: Deleuze and the Philosophy of Cinema was published in 2000. Gilles Deleuze and the Fabulation of Philosophy: Powers of the False, his book from 2011 uses the idea of friendship as an initial condition from which to reexamine Deleuze’s philosophy. Covering everything from Deleuze’s apprenticeship with Friedrich Nietzsche to his vow to overthrow Plato, Flaxman reintroduces aesthetics to Deleuzian studies, showing how Deleuze situated fiction in the center of a minor philosophy. He writes, “Deleuze declares no abiding loyalties: not only does he mingle with countless philosophers, but he flirts with just as many writers, filmmakers, and artists.” This nomadic “promiscuity” is one more reason that the well of Deleuze’s ideas isn’t likely to run dry any time soon, and Flaxman’s is a deep and welcome reconsideration. Moreover, his focus on friendship is intriguing. In The Two-Fold Thought of Deleuze and Guattari, Charles Stivale writes, “This rapport of friendship lies, I believe, at the very core of these authors’ collaborative engagement…” Nietzsche freed Deleuze from the arid areas of academe, and Deleuze focused Guattari without truncating his thoughts too much. If you’ve read any Guattari without Deleuze, you know they needed a trim here and there.

Speaking of friendship, if you’d like a more personal — and historical — look at Deleuze and his main co-conspirator, there’s François Dosse’s Gilles Deleuze & Félix Guattari: Intersecting Lives, which, appropriately enough, is 651 pages long. The duo met shortly after the revolts of May, 1968, to which Anti-Oedipus is largely a reaction: “Initially it was less a question of pooling knowledge than the accumulation of our uncertainties,” Guattari said in Chaosophy. Guattari had just been passed over as Lacan’s successor, which sent him into a deep depression tempered only by throes of mania. With a milder manner and more comfort within his confines, Deleuze was the calm of their storm, a storm that still surges through classes and discussions in philosophy, postmodernism, post-structuralism, cultural studies, film studies, net criticism, and so on. So, what was their beef with Marx, Freud, Plato, and every other thinker--save Nietzsche and Foucault, of course--that preceded them? It’s all here. Dosse’s book is the definitive story of these two major collaborators, thinkers, writers, jokesters, and, perhaps above all, friends.

Desire is under it all, according to the iconoclastic French duo. The capitalism machine creates layers and layers of desires and subsequently splits selves into schizophrenia (hence the subtitle of both volumes of their two-volume work: Capitalism and Schizophrenia). William Carlos Williams wrote in 1923, “The pure products of America go crazy.” That’s not exactly what they meant, but maybe that’s why Deleuze, along with Guattari, have such a hold on the academy’s mass mind: Our spirits are all spiraling apart in so many separate ways, just as they said they would all those years ago.

But maybe, as they were, we can still be friends.

You Don’t Know What You’ve Got Until You Get It Back.My sci-fi novella, Fender the Fall, is a time-travel love story. Chris Bridges, a lovelorn physics graduate student who goes back in time to return the journal of his high-school crush in order to save his marriage and her life. The plan doesn’t go as planned.

It’s available from Alien Buddha Press! It’s 5”x8” and 136-pages long, like a good paperback should be. It’s the perfect weekend read.

I was fortunate enough to get Matthew Revert to design the cover and Mike Corrao to do the typesetting. As a result, it’s a sharp-looking little book.

Here’s what other people are saying about it:

“A fun, classic roller-coaster of a time-travel story that could have been published in the 1950s, except that it’s furnished with all manner of savvy insights into current 2020s life.” — Paul Levinson, author of The Plot to Save Socrates

“Fender the Fall is a nostalgia-infused journey through time about second chances and the causality of love. It’s a formative song from your youth revisited, a favorite VHS tape found in the back of your closet.” – Joshua Chaplinsky, author of The Paradox Twins

“Hard-boiled strange loops in a froth of weird.” – Will Wiles, author of Plume

Many thanks to Matt Revert and Mike Corrao for making this thing look so good; Red Focks for putting it out there; Paul Levinson, Josh Chaplinsky, Will Wiles, Jaqi Furback, Gabriel Hart, C.W. Blackwell, Ira Rat, J. Matthew Youngmark, and Jeph Porter for their time, feedback, and kind words; and Claire Putney, from whom I stole the title.

Here’s a soundtrack I put together while writing Fender the Fall. It has songs mostly from and around the years in the story (2002 and 1991).

Order your copy of this lovely, little paperback from Alien Buddha Press now! You won’t regret it.

Thank you for your time and attention, and for reading, responding, and sharing.

More soon,

-royc.

March 30, 2022

The Science of Sound and Silence

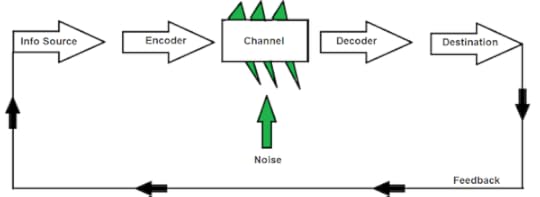

We often speak of noise referring to the opposite of information. In the canonical model of communication conceived in 1949 by Claude Shannon and Warren Weaver, noise is anything in the system that disrupts the signal or the message being sent.

If you’ve ever tried to talk on a cellphone in a parking garage, find a decent sounding radio station while driving through a fly-over state, or follow up on a trending topic on Twitter, then you know what this kind of noise looks like. Thanks to Shannon and Weaver and their followers, it’s remained a mainstay of communication theory ever since, privileging machines over humans. Well before it was a theoretical metonymy, noise was characterized as “destruction, distortion, dirt, pollution, an aggression against the code-structuring messages.” More pointedly, in his book Noise: The Political Economy of Music, Jacques Attali conceives noise as pain, power, error, murder, trauma, and youth—among other things—untempered by language. Noise is wild beyond words.

The two definitions of noise discussed above—one referring to unwanted sounds and the other to the opposite of information—are mixed and mangled in Hillel Schwartz’s Making Noise: From Babel to the Big Bang and Beyond, a book that rebelliously claims to have been written to be read aloud. Yet, he writes, “No mere artefacts of an outmoded oral culture, such oratorical, jurisprudence, pedagogical, managerial, and liturgical acts reflect how people live today, at heart, environed by talk shows, books on tape, televised preaching, cell phones, public address systems, elevator music, and traveling albums on CD, MP3, and iPod.” We live not immersed in noise, but saturated by it. As Aden Evens put it, “To hear is to hear difference,” and noise is indecipherable sameness. But, one person’s music is another’s noise—and vice versa, and age and nostalgia can eventually turn one into the other. In spite of its considerable heft (over 900 pages), Making Noise does not see noise as music’s opposite, nor does it set out for a history of sound, stating that “‘unwanted sound’ resonates across fields, subject everywhere and everywhen to debate, contest, reversal, repetition: to history.”

"Wherever we are, what we hear is mostly noise. When we ignore it, it disturbs us. When we listen to it, we find it fascinating." — John Cage

The digital file might be infinitely repeatable, but that doesn’t make it infinite. Chirps in the channel, the remainders of incomplete communiqué surround our signals like so much decimal dust, data exhaust. In Noise Channels: Glitch and Error in Digital Culture, Peter Krapp finds these anomalies the sites of inspiration and innovation. My friend Dave Allen is fond of saying, “There’s nothing new in digital.” To that end, Krapp traces the etymology of the error in machine languages from analog anomalies in general, and the extremes of two records from 1975, Lou Reed’s Metal Machine Music and Brian Eno’s Discreet Music, up through our current binary blips and bleeps, clicks and clacks—including Christian Marclay‘s multiple noisy artistic forays and Cory Arcangel’s digital synesthesia. This book is about both forms of noise as well, paying due attention to the distortion of digital communication.

"Without sound, celebration and grief look nearly the same."

— Sam in Ben Marcus’s The Flame Alphabet

Though considered the absence of not only noise but sound altogether, an entity defined by lack, silence is its own swollen signifier. We often find it awkward in social situations, public forums, on the radio. Anywhere we expect the sound of a voice, silence is suspect. “Uncomfortable silences,” Mia Wallace complains in Pulp Fiction, “Why do we feel it’s necessary to yak about bullshit in order to be comfortable?” We fill every space with sound. But, as the sultan of silence, John Cage, taught us, “Silence is not acoustic. It is a change of mind, a turning around.”

"The most successful ideological effects are those which have no need of words, and ask no more than complicitous silence."

— Pierre Bourdieu, Outline of a Theory of Practice

Silence indicates unheard voices. Mladen Dolar writes In Jonathan Sterne's The Sound Studies Reader, “The absence of voices and sounds is hard to endure; complete silence is immediately uncanny, it is like death, while the voice is the first sign of life.” Orfied Laboratories’ Anechoic Chamber, built by Eckel Industries and pictured above, is a foam room within a room, built on i-beams and springs, surrounded by steel. The outer room is encased in foot-thick, concrete walls. There’s a running bet at the lab offering a case of beer to anyone who can stay in it with the lights off for over 45 minutes. In a rather psychological example of what Douglas Kahn calls the “impossible inaudible,” no one’s been able to stay inside for more than half an hour. Its death-like silence makes its Guinness Book of World Records award as “The Quietest Place on Earth” seem sinister.

In her investigation of silence in fiction, Alix Ohlin notes, “Silence, created through ellipsis, white space, and repetition, is another form of erasure; it tells the reader of a pain that is too great to bear, yet must be borne.” just as Susan Sontag writes, “Silence remains, inescapably, a form of speech.” The complaint is often hidden until heard. Breaking the silence is the first step to its resolution. Tara Rodgers’ essay in Sterne’s collection, “Toward a Feminist Historiography of Electronic Music,” also equates silence to a unspoken grievance, quoting poet Adrienne Rich: “The impulse to create begins–often terribly and fearfully–in a tunnel of silence… The first question we might ask a poem is, What kind of voice is breaking the silence, and what kind of silence is being broken?” Similarly, in “The Audio-Visual iPod,” Michael Bull equates it with isolation. Silence makes an uneasy companion.

"Air has so much to say for itself. Sound is just bugged air."

— McKenzie Wark, Dispositions

Bugging the air and bugging the airwaves, sound surrounds us. In his essay, “The Auditory Dimension,” Don Ihde phenomenologically relates hearing to seeing, the silent to the invisible. Rephrasing the age-old, tree-falling-in-the-forest question, he writes, “Does each event of the visible world offer the occasion, even ultimately from a sounding presence of mute objects, for silence to have a voice? Do all things, when fully experienced, also sound forth?”

Tackling the presence of no object, Sterne’s MP3: The Meaning of a Format investigates the evolution and epistemology of our prevailing sound format. Originally intended as a way to transfer sound over phone lines, the MP3 has become a case study in the digital reorganization of an industry. “Chances are,” Sterne writes, “if a recording takes a ride on the internet, it will travel in the form of an MP3 file.” Identifying the internet as its native environment, the “dot-mp3” file extension was born on July 14, 1995. “At some point in the late 90s,” says Karlheinz Brandenburg, whose Ph.D. work in 1982 landed him in the middle of the development of the format, “MP3 was technically the best system out there, and at the same time, it was accessible to everybody.” These two aspects gave the MP3 an early foothold, it was patented in 1989, and now every device that plays digital audio files can play one. With the introduction of the first portable MP3-player in 1998, the record industry’s early-eighties nightmares were coming true, and the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) started its ongoing legal battle against the digital revolution. Once online file-sharing and the iPod came online around the turn of the millennium, the floodgates were open, and music was liberated not only from the dams of physical formats but also physical spaces. What once took rooms of equipment and stacks of physical media to enjoy is now in everyone’s pocket.

"There is a place between voice and presence where information flows." — Rumi

Sharing silence can be the ultimate sign of intimacy. The unspoken solace of a loved one close by manifests a complicit quiet. Mia Wallace continues, “That’s when you know you’ve found somebody special. When you can just shut the fuck up for a minute and comfortably enjoy the silence.”

Amen.

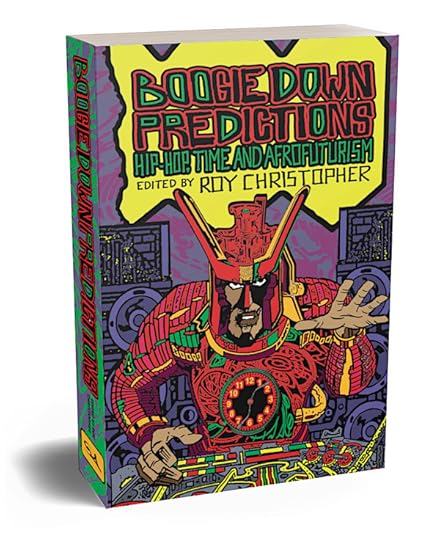

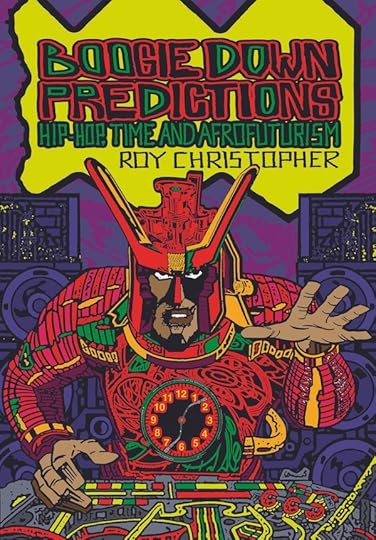

MORE ON THE SCIENCE OF SOUND:If you’re interested in the joyous noise of hip-hop, cyberpunk, and Afrofuturism, a bunch of my friends and colleagues and I have put together a collection of essays called Boogie Down Predictions: Hip-Hop, Time, and Afrofuturism. Harry Allen, Hip-Hop Activist and Media Assassin, says,

“How does hip-hop fold, spindle, or mutilate time? In what ways does it treat technology as, merely, a foil? Are its notions of the future tensed…or are they tenseless? For Boogie Down Predictions, Roy Christopher's trenchant anthology, he's assembled a cluster of curious interlocutors. Here, in their hands, the culture has been intently examined, as though studying for microfractures in a fusion reactor. The result may not only be one of the most unique collections on hip-hop yet produced, but, even more, and of maximum value, a novel set of questions.”

[Cover Art by Savage Pencil.]

Boogie Down Predictions is coming soon from Strange Attractor, but it's available for preorder from the outlet of your choice! Please preorder it if you can! Preorders set in motion all kinds of good stuff for books and their creators.

If you're still not convinced, here are more details, including the table of contents, back-cover blurbs, and a nice review from The Wire Magazine. The list of contributors on this thing includes Ytasha L. Womack, Kodwo Eshun, Tiffany E. Barber, Kembrew McLeod, Dave Tompkins, Steven Shaviro, Labtekwon, Juice Aleem, Aram Sinnreich, DJ Foodstamp, Erik Steinskog, and many others. Hold tight!

MORE NOISE:

[Dead Precedents with the hands from Run the Jewels' RTJ3. Photo by Tim Saccenti.]

In the past three years, over a thousand of you have picked up a copy of my book Dead Precedents: How Hip-Hop Defines the Future from Repeater Books. I just wanted to extend a special shout out: Thank you!

If you haven't gotten yours and are curious, you can find out more on my website or the recent three-year anniversary newsletter.

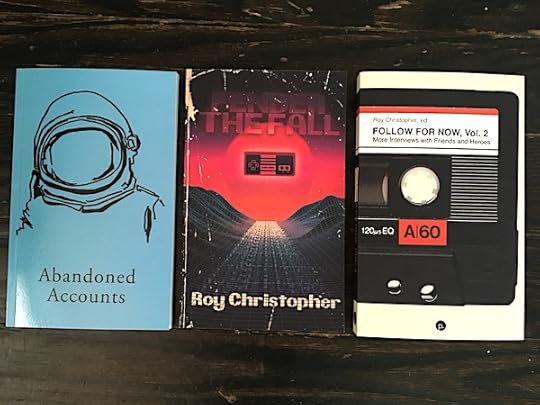

THREE NEW BOOKS:Also, in case you haven't snagged them yet, I have three (3!) new books out:

Follow for Now, Vol. 2: More Interviews with Friends and Heroes (from punctum books)

Fender the Fall (a sci-fi novella from Alien Buddha Press)

Abandoned Accounts (poetry collection from First Cut)

As always, thank your for reading, responding, and sharing! You are appreciated.

Hope you're well,

-royc.

March 22, 2022

Swarm Cities: Location is Everywhere

Since moving out on my own, I’ve gravitated toward cities: Seattle, Portland, San Francisco, San Diego, Austin, Atlanta, Chicago. Externalized memories built in brick and concrete. It reminds me of a passage from Steve Erickson’s novel Days Between Stations:

“What is the importance of placing a memory? he said. Why spend that much time trying to find the exact geographic and temporal latitudes and longitudes of the things we remember, when what’s urgent about a memory is its essence?”

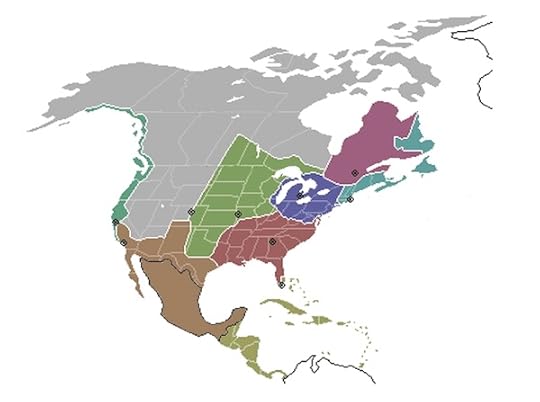

[The “nine nations” of North America. Image credit: A Max J // CC BY 3.0]

Our cities, those densely populated spaces of our built environment, have always been slowly redefining themselves. In 1981, there were the nine nations of North America. In 1991, the Edge Cities emerged. In 2001, we witnessed the worst intentions of a tightly networked community that lacked physical borders—what Richard Norton calls a “feral city,” a community that’s beyond the reach of law and order.

Our capital-driven, networked societies produce, more than anything else, ephemeral things — that is, things that are built, not to last, but to disappear and be displaced by newer versions of themselves. As David Byrne wrote in his Bicycle Diaries, cities “are physical manifestations of our deepest beliefs and our often unconscious thoughts, not so much as individuals, but as the social animals we are.” If our collective consciousness is flitting and flickering from one thing to the next, so shall our cities follow suit.

From flash mobs to terrorist cells, communities can now quickly toggle between virtual and physical organization. How long before our cities do the same?

“In the sagas it was said that humans dream with their hands, only their hands, and so have cities rather than sagas, monuments rather than memories.” — Ted Mooney, Easy Travel to Other Planets

According to Joel Garreau, an “edge city” is one that is “perceived by the population as one place.” Like in tight-knit neighborhoods, its residents staunchly identify with and defend it, resisting outside influence. Conversely, rapid transit has increased the exchange of ideas between once-isolated places, spurring innovation. The French philosopher Gilles Deleuze called these areas “any-space-whatever,” the space in his view only important for the connections it facilitates. Critiquing the much-lauded coming of the “smart city,” Adam Greenfeld wrote that “the important linkages aren’t physical but those made between ideas, technical systems, and practices.” After all, the first condition for a smart city is a world-class broadband infrastructure.

Connection is key — the connection could be the city.

[Peter Root, “Ephemicropolis,” 2010]

“We’ve created 10,000 places that are not worth caring about. Imagine the corrosive effect of that on our national psychology. How soon before we become a land not worth defending?” — James Howard Kunstler, in conversation with the author

It’s been argued that we are at work, rather unwittingly, building an “Ephemicropolis,” a sprawling urbanity without roots or reason. In his recent book Out of the Mountains, David Kilcullen defines four global factors that will determine the future of Ephemicropolis: population growth, urbanization, littoralization (the human tendency to cluster along shorelines), and connectedness. As more and more people meet and fall in love and populate the planet, they are doing so in bigger cities, near the water, and with more connectivity than ever.

Basically, the future of human hives is crowded, coastal, connected, and complex.

[Anish Kapoor’s Cloud Gate in Chicago. Image credit: Roy Christopher]

As soon as the coasts recede with the rising ocean tides, those hives will have to move inland. More importantly, they will have to disassemble, move, and reassemble in some fashion. Urban planner Kevin Lynch once called cities “systems of access that pass through mosaics of territory.” That description is fitting for what I call “swarm cities,” a tenuous but slightly more stable form of what Eric Kluitenberg refers to as “swarm publics”: “Today, we are witnessing the rise of swarm publics, highly unstable constellations of temporary alliances that resemble a public sphere in constant flux; globally mediated flash mobs that never meet, fueled by sentiment and affect, escaping fixed capture.”

“The city, as a form of the body politic, responds to new pressures and irritations by resourceful new extensions always in the effort to exert staying power, constancy, equilibrium, and homeostasis.” — Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media

Swarm cities are only as physical as they need to be. And, as connected as they are, they’re also only as cohesive as their sustainment demands. The networked freedom to live and work anywhere doesn’t always make location irrelevant, however; it often makes it that much more important. Kevin Lynch wrote, “Our senses are local, while our experience is regional.” Meanwhile, Robert J. Sampson argues for behavior based on our idea of local roots. The neighborhood effect is how we describe the interaction between individuals and their main network, and between the local and the global.

The neighborhood is where boundaries matter. It’s where human perception binds us within borders, where nodes are landmarks in a physical network, not connections in the cloud. As Italo Calvino wrote in his novel Invisible Cities: “The city, however, does not tell its past, but contains it like the lines of a hand, written in the corners of the streets, the gratings of the windows, the banisters of the steps, the antennae of the lightning rods, the poles of the flags, every segment marked in turn with scratches, indentations, scrolls.”

Like the landmarks and memories of neighborhoods, swarm cities are duplicitous, existing both inside and outside our heads.

“Memory is redundant: It repeats signs so that the city can begin to exist.” — Kathy Acker

Early on in his book In Divisible Cities, Dominic Pettman repurposes the idea of “mattering maps,” those maps we make to and from the things that matter: “A map that generates territory, rather than the other way around ... A map that does not represent cities that exist independently, but a map that brings cities into being.”

Cities used to spring up near water. Rivers crisscrossing through dirt provided the networks. Railroads and highways developed next, with the metropolis growing between their branches. Cities emerge where connectivity gets concentrated. Just as the telegraph separated communication from transportation, the current dominant forms of connectivity are not grounded in physical space. The cities of the future will emerge with cultural scripts as blueprints, with landmarks like 9/11, Columbine, and Katrina. Their unity condensed from vapor, all clouds -- or limbs and leaves with no roots. Think Home Depot instead of home. The strip mall as town hall. Disposable digs inhabited by a pop-up populace.

Local communities haven’t been diminished by global networks, they have come unmoored because their connectedness isn't physically grounded. There remains no absolute value to the region you happen to occupy. The nodes shift as needed. This is the cartography of the future: giant, sprawling mattering maps made of memories. Within them are vast and multiple new swarm cities to explore.

Acknowledgments: Originally written for Steven Johnson's How We Get to Next website, parts of this piece are now a part of "Location is Everywhere," Chapter 8 of my book-in-progress, The Medium Picture. Special thanks and apologies to Mark Wieman for the chapter title.

COMING SOON:

Our edited essay collection Boogie Down Predictions: Hip-Hop, Time, and Afrofuturism is coming soon from Strange Attractor! This colorful collaboration is available for preorder from the outlet of your choice! Please preorder it if you can! Preorders set in motion all kinds of good stuff for book releases and make me and my friends look really good in the eyes of my publisher!

Bestselling author of Dilla Time and The Big Payback, Dan Charnas says,

“The study of hip-hop requires more than a procession of protagonists, events, and innovations. Boogie Down Predictions stops the clock—each essay within it a frozen moment, an opportunity to look sub-atomically at the forces that drive this culture.”

If you're still not convinced, here are more details, including the table of contents, back-cover blurbs, a nice review from The Wire Magazine, etc. The list of contributors on this thing includes Ytasha L. Womack, Kodwo Eshun, Tiffany E. Barber, Dave Tompkins, Nettrice Gaskins, Steven Shaviro, Labtekwon, Kembrew McLeod, Juice Aleem, Aram Sinnreich, DJ Foodstamp, Erik Steinskog, and many others. Hold tight!

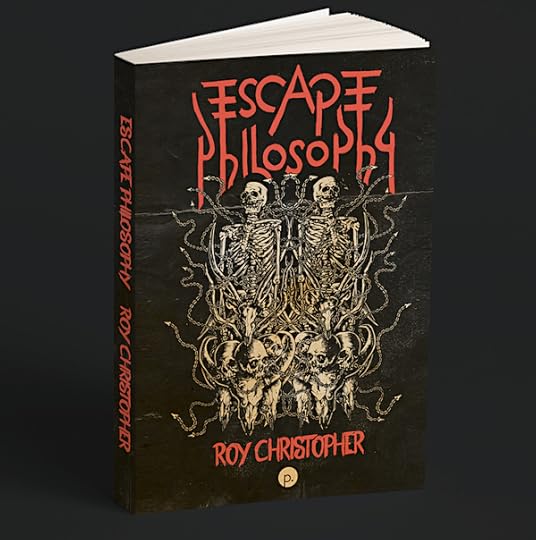

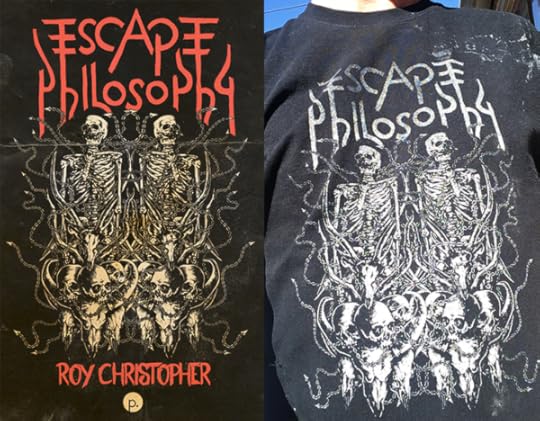

COMING SOONER:Also coming up is Escape Philosophy: Journeys Beyond the Human Body, about which Eugene Thacker, author of In the Dust of This Planet, says,

"Too often philosophy gets bogged down in the tedious 'working-through' of contingency and finitude. Escape Philosophy takes a different approach, engaging with cultural forms of refusal, denial, and negation in all their glorious ambivalence."

More about this one, coming soon from punctum books!

ICYMI:Also, in case you missed them in all of that, I have three (3!) new books out:

Follow for Now, Vol. 2: More Interviews with Friends and Heroes (from punctum books)

Fender the Fall (a sci-fi novella from Alien Buddha Press)

Abandoned Accounts (poetry collection from First Cut)

As always, thank you all for your continued interest and support and for reading, responding, and sharing! It is appreciated.

Hope you're well,

-royc.

March 16, 2022

Three Years of Dead Precedents: How Hip-Hop Defines the Future

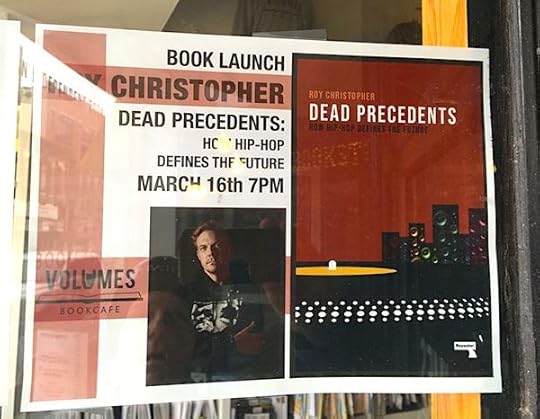

We launched Dead Precedents properly at Volumes Bookcafé in Chicago with readings by me, Krista Franklin, and Ytasha L. Womack.

[Krista Franklin, me, and Ytasha L. Womack. Photo by Lily Brewer.]

Ytasha and I went on to do a talk at the Seminary Co-op in Hyde Park, and I spoke at SXSW again, this time specifically about the ideas in Dead Precedents.

[Talkin’ beaks and rhymes at SXSW. Photo by Matt Stephenson.]

[As Pecos B. Jett called it, “Biz Marquee!“]

A couple of months later, I ventured to my adopted home in the Pacific Northwest. I got to speak at Powell’s City of Books in Portland with Pecos B. Jett. I was even on TV!

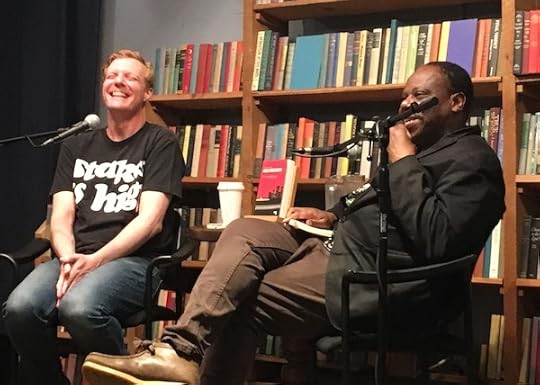

Next up was a fun chat at the Elliott Bay Book Company in Seattle with Charles Mudede.

[Me and Charles Mudede yuckin’ it up at Elliott Bay. Photo by Lily Brewer.]

I was also on my favorite Hip-hop podcast, Call Out Culture with my mans Alaska, Zilla Rocca, and Curly Castro.

I know Amazon is wack, but Dead Precedents was also a #1 New Release in both their Rap Music and Music History & Criticism categories.

[Take that, Beastie Boys Book!]

Dan Hancox reviewed Dead Precedents for The Guardian, writing that it is, "written with the passion of a zine-publishing fan and the acuity of an academic." Mark Reynolds at PopMatters wrote, "In Christopher’s construction, hip-hop is is not merely party music for black and brown Gen-Xers and millennials, but the first salvo in a radical, transformative way of understanding and making culture in the technological era — the beginning, in essence, of the world we’re living in now."

[Dead Precedents with the hands from Run the Jewels' RTJ3. Photo by Timothy Saccenti.]

Many thanks to all the people who bought the book, said nice things about it, came out to hear me talk about it, gave me rides, put me up at your home, or spread the word. There are too many people I owe to list here, but I appreciate all of you who have supported me and this book in any way.

BOOGIE DOWN PREDICTIONS: Hip-Hop, Time, and AfrofuturismIf you’re interested in more about hip-hop, cyberpunk, and Afrofuturism, a bunch of my friends and colleagues and I have put together a companion collection of essays called Boogie Down Predictions: Hip-Hop, Time, and Afrofuturism. Harry Allen, Hip-Hop Activist and Media Assassin says,

“How does hip-hop fold, spindle, or mutilate time? In what ways does it treat technology as, merely, a foil? Are its notions of the future tensed…or are they tenseless? For Boogie Down Predictions, Roy Christopher's trenchant anthology, he's assembled a cluster of curious interlocutors. Here, in their hands, the culture has been intently examined, as though studying for microfractures in a fusion reactor. The result may not only be one of the most unique collections on hip-hop yet produced, but, even more, and of maximum value, a novel set of questions.”

[Cover Art by Savage Pencil.]

Boogie Down Predictions: Hip-Hop, Time, and Afrofuturism is coming soon from Strange Attractor, but it's available for preorder from the outlet of your choice! Please get it if you can! Preorders set in motion all kinds of good stuff for book releases.

If you're still not convinced, here are more details, including the table of contents, back-cover blurbs, and a nice review from The Wire Magazine. The list of contributors on this thing includes Ytasha L. Womack, Kodwo Eshun, Tiffany E. Barber, Kembrew McLeod, Dave Tompkins, Steven Shaviro, Labtekwon, Juice Aleem, Aram Sinnreich, DJ Foodstamp, Erik Steinskog, and many others. Hold tight!

DEAD PRECEDENTS: Preface[What follows is the brief essay that serves as the Preface to Dead Precedents. If you don’t know, now you know.]

“Space, that endless series of speculations and origins — of rebirths and electric spankings — is here not so much a metaphor as it is a series of fragmented selves, a place of possibilities and debris and explorations and atmosphere.”

— Kevin Young, The Grey Album: On the Blackness of Blackness

“Let us imagine these hip-hop principles as a blueprint for social resistance and affirmation: create sustain- ing narratives, accumulate them, layer, embellish, and transform them.”

— Tricia Rose, Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America

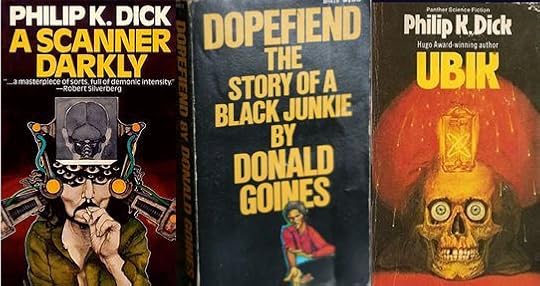

Several years ago, on one of my online profiles under “books” I listed only Donald Goines and Philip K. Dick. If you don’t know them, Donald Goines wrote about himself and his associates and their struggles as street hustlers, pimps, players, and dopefiends. Philip K. Dick wrote about the brittleness of reality, its wavy, funhouse perceptions through drugs and dreams. Goines wrote sixteen books in five years and Dick wrote forty-four in thirty. Both were heavy users of mind-altering substances (heroin and amphetamines, respectively), and both helped redefine the genres in which they wrote. They interrogated the nature of human identity, one through the inner city and the other through inner space.

While I am certainly a fan of both authors, I posted them together on my profile as kind of a gag. I thought their juxtaposition was weird enough to spark questions if you were familiar with their work, and if you weren’t, it wouldn’t matter. I had no idea that I would be writing about the overlapping layers of their legacies so many years later.

To retrofit a description, one could say that Goines’ books are gangster-rap literature. They’re referenced in rap songs by everyone from Tupac and Ice-T to Ludacris and Nas. In many instances, Dick’s work could be called proto- cyberpunk. The Philip K. Dick Award was launched the year after he died, and two of the first three were awarded to the premiere novels of cyberpunk: Software by Rudy Rucker in 1983 and Neuromancer by William Gibson in 1985.

[Ed note: If you’re interested, wrote a bit about the connections between hip-hop and literature for Literary Hub for the book’s release.]

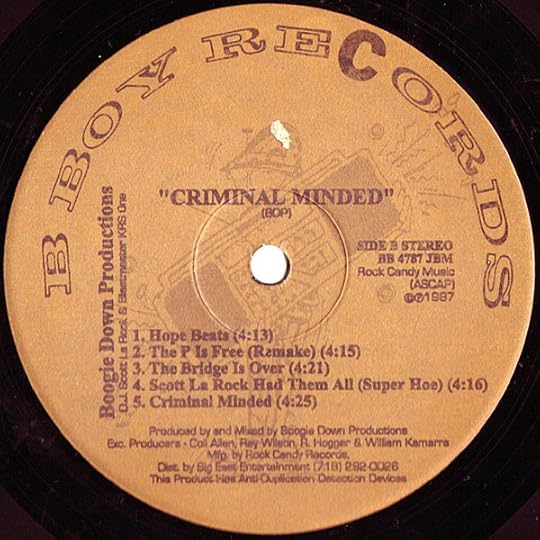

When cyberpunk and hip-hop were both entering their Golden Age, I was in high school. One day I was walking up my friend Thomas Durdin’s driveway. By the volume of the AC/DC sample that forms the backbone of Boogie Down Productions’ “Dope Beat,” I knew his mom wasn’t home. Along with the decibel level, I was also struck by how the uncanny pairing of Australian hard rock and New York street slang sounded. It was gritty. It was brash. It rocked. De La Soul’s 1996 record, Stakes is High, opens with the question, “Where were you when you first heard Criminal Minded?” That moment was a door opening to a new world.

I didn’t realize it then, but that new world was the twenty- first century, and hip-hop was its blueprint.

[Boogie Down Productions Criminal Minded, side B, track 1: “Hope Beats.”]

I distinctly remember that the label on the record spinning around on Thomas’s turntable incorrectly named the song “Hope Beats.” An interesting mistake given that DJ Scott La Rock was killed just months after the record came out, prompting KRS-One to start the Stop the Violence movement. Where Criminal Minded is often cited as a forerunner of gangster rap, KRS-One was thereafter dedicated to peace. I’d heard hip-hop before, but the unfamiliar familiarity of the “Back in Black” guitar samples in that song make that particular day stick in my head.

Long before hip-hop went digital, mixtapes—those floppy discs of the boombox and car stereo—facilitated the spread of underground music. The first time I heard hip-hop, it was on such a tape. Hiss and pop were as much a part of the experience of those mixes as the scratching and rapping. We didn’t even know what to call it, but we stayed up late to listen. We copied and traded those tapes until they were barely listenable. As soon as I figured out how, I started making my own. We watched hip-hop go from those scratchy mixtapes to compact discs to shiny-suit videos on MTV, from Fab 5 Freddy to Public Enemy to P. Diddy, from Run-DMC to N.W.A. to Notorious B.I.G. Others lost interest along the way. I never did.

A lot of people all over the world heard those early tapes and were impacted as well. Having spread from New York City to parts unknown, hip-hop became a global phenomenon. Every school has aspiring emcees, rapping to beats banged out on lunchroom tables. Every city has kids rhyming on the corner, trying to outdo each other with adept attacks and clever comebacks. The cipher circles the planet. In a lot of other places, hip-hop culture is American culture.

Though their roots go back much further, the subcultures of hip-hop and cyberpunk emerged in the mass mind during the 1980s. Sometimes they’re both self-consciously of the era, but digging through their artifacts and narratives, we will see the seeds of our times sprouting. We will view hip-hop not only as a genre of music and a vibrant subculture but also as a set of cultural practices that transcend both of those. We will explore cyberpunk not only as a subgenre of science fiction but also as the rise of computer culture, the tectonic shifting of all things to digital forms and formats, and the making and hacking thereof. If we take hip-hop as a community of practice, then its cultural practices inform the new century in new ways. “I didn’t see a subculture,” Rammellzee once said, “I saw a culture in development.”

[The Equation: RAMMELLZEE. Photo by Timothy Saccenti.]

The subtitle of this book could just as easily be “How Hip-Hop Defies the Future.” As one of hip-hop culture’s pioneers, Grandmaster Caz, is fond of saying, “Hip-hop didn’t invent anything. Hip-hop reinvented everything.” To establish this foundation, we will start with a few views of hip-hop culture (Endangered Theses), followed by a brief look at the origins of cyberpunk and hip-hop (Margin Prophets). We will then look at four specific areas of hip-hop music: recording, archiving, sampling, and intertextuality (Fruit of the Loot); the appropriating of pop culture and hacking of language (Spoken Windows); and graffiti and other visual aspects of the culture (The Process of Illumination). From there we will go ghost hunting through the willful haunting of hip-hop and cyberculture (Let Bygones Be Icons). All of this in the service of remapping hip-hop’s spread from around the way to around the world and what that means for the culture of the now and the future (Return to Cinder).

The aim of this book is to illustrate how hip-hop culture defines twenty-first-century culture. With its infinitely recombinant and revisable history, the music represents futures without pasts. The heroes of this book are the architects of those futures: emcees, DJs, poets, artists, writers. If they didn’t invent anything but reinvented everything, then that everything is where we live now. Forget what you know about time and causation. This is a new fossil record with all new futures.

As always, thanks for reading, responding, and sharing. It's mad appreciated.

Hope you're well,

-royc.

March 8, 2022

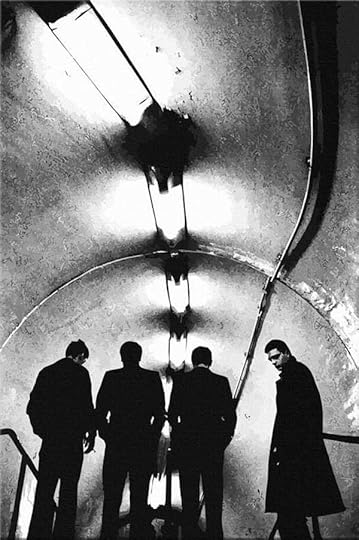

Joy Division: The Rest is Mystery

In Jon Savage's recent This Searing Light, the Sun, and Everything Else (faber & faber, 2019), Liz Naylor says, "My thing about Joy Division is they're an ambient band almost: you don't see them function as a band, it's just the noise around where you are." Even with his life’s story on film with the Anton Corbijn-directed Control (2007) and many books written, there remains so much mystery around Ian Curtis. “He seemed able to surrender control of his life as if it was nothing to do with him at all,” his widow Debbie wrote of him at the time of his overdose. Indeed, he wasn’t much in control as the band went straight back to doing shows. “Ian went straight from his suicide attempt to a gig at Derby Hall, Bury, on 8 April 1980,” Debbie writes in Touching from a Distance (faber & faber, 1995). He only sang two songs at that fabled show, which ended in an outright riot. Something, nay, many things had to break.

Just four years earlier on June 4, 1976, the Sex Pistols played another much-fabled show in Manchester to a few dozen people and even more empty chairs (the scene in the movie 24-Hour Party People supposedly has it about right). Supposedly everyone there left that show dead-set on starting a band. There’s even a book about it: I Swear I Was There: The Gig That Changed the World by Dave Nolan (Blake Publishing, 2006). In attendance were Pete Shelley and Howard Devoto (of the nascent Buzzcocks, who organized the gig but weren’t ready to play), Kevin Cummins (photographer who took many great pictures of the British punk and post-punk scene, including the one above), Mark E. Smith (The Fall), Mick Hucknall (Simply Red), Tony Wilson (TV personality and future Factory Records owner), Paul Morley (writer; chronicler of the Factory scene for NME; future co-counder of The Art of Noise), Rob Gretton (future manager), Martin Hannett (future producer), Morrissey (duh), and Bernard Sumner and Peter Hook (who of course went on to immediately start the band that would become Joy Division). Peter Hook gets all of this down in his Unknown Pleasures: Inside Joy Division (!t Books, 2013), and like Debbie Curtis, he was right there when it all went down, albeit facing different facets of there and a different facets of Curtis.

“Inside Joy Division” is an apt subtitle for this story as Hook was as inside as one gets. Playing high on the bass, as apparently Ian liked it, Hook’s bass-lines are some of the most distinctive in rock music of any kind. Hook’s prose in the book is even-handed, heartfelt, and hilarious. He’s open about what he remembers and what he can’t, and he struggles throughout with the mystery surrounding Curtis. As troubled and tortured as he was, Curtis always said he was okay, and everyone believed him to the very end. A lot of it was apparently written right in his lyrics, giving them an eerie prescience. Debbie, Annick, Tony, Martin, Rob, Steve, Bernard, Peter — no one near him believed he was singing about himself. It was his art.

Like Kurt Cobain, Jim Morrison, and Darby Crash, Ian Curtis was the stormy center of an iconoclastic young band. They were all “serious young men with important things on their minds,” as Tim Keegan describes Joy Division in The First Time I Heard Joy Division/New Order. All of these singers left behind a legacy of longing, but Peter Hook’s book helps explain the groupthink that may have contributed to their early deaths. It’s as tragic as it is truthful, and as complex as it is comedic.

As many did at the Sex Pistols gig above, everyone has that moment with a band. Scott Heim has set out to capture them — poignant and palpable — in his The First Time I Heard... series. The Joy Division/New Order entry boasts tales from members of Lush, The Jesus & Mary Chain, Maps, Rothko, Stereolab, Swervedriver, The Wedding Present, Bedhead, Silkworm, and Jessamine, as well as writers such as James Greer (once a member of Guided By Voices himself), Daniel Allen Cox, Sheri Joseph, Mark Gluth, and Sylvia Sellers-Garcia, among many others.

Having missed his one chance to see Joy Divsion before Curtis died, Philip King describes seeing New Order for the first time a few months later: “My memory of the show was the band looking very numb and solitary as though they were all on their own separate islands, having to deal with their grief on their own–and there being a very conspicuous space, center stage, where Ian Curtis would have stood.” The song “Ceremony” stands in that liminal space between Joy Division and New Order, between the presence and absence of Ian Curtis. Joy Division only performed the song live once just a week before Curtis died, and it became New Order’s first single. Illustrating that middle, and the lasting influence of both bands, here’s Radiohead doing a rather Pixiefied version of “Ceremony”:

In his 33 1/3 entry on Unknown Pleasures, Chris Ott describes Joy Division’s music as “potent as any drug: overwhelming, stupefying, and certainly addictive,” and in his book, Rip It Up and Start Again: Postpunk 1978-1984, Simon Reynolds cites Unknown Pleasures as one of the trinity of “postpunk landmarks” from 1979, along with Talking Heads’ Fear of Music and Public Image Ltd’s Metal Box — to which I would add Gang of Four‘s Entertainment!. Joy Division’s odd conventions are among the “hallmarks of indie sound.” One can hear their punky proto-goth in everything from Low, Codeine, Radiohead, and Godflesh to the more obvious Bedhead, Bloc Party, and Interpol.

Listening to Joy Division as much as I have over the years, a few key things about them emerge. As most of the above witnesses and writers are quick to point out, their chemistry is undeniable. As large as the presence and subsequent absence of Ian Curtis looms, Joy Division was the distinct product of these four guys. Think about most other truly great bands: They are something beyond their sum. It wouldn’t be what it is otherwise. Another thing that becomes evident is that they were still growing. Joy Division only recorded two full-length records and a handful of singles. Some of them are rock n’ roll romps reminiscent of Chuck Berry, some of them are Sex-Pistols punky, some of them hint at the goth/industrial bent that others would later pick up, and some of them are something else entirely. Their sound just wasn’t quite developed yet. With that said, it’s also obvious that they are one of the greatest groups to ever do it.

There’s no mystery about that.

ICYMI:Full disclosure regarding the piece above: I have an essay in the collection The First Time I Heard My Bloody Valentine, along with my man Alap Momin (dälek), Bob Mould, Christian Savill (Slowdive), Geoff Sanoff (Edsel), Jonathan Segel (Camper Van Beethoven), Scott Cortez (lovesliescrushing), Ian Masters (Pale Saints), Gazz Carr (God Is an Astronaut), and Kellii Scott (Failure), among several others.

Also, in case you missed them, I have three (3!) new books out:

Follow for Now, Vol. 2: More Interviews with Friends and Heroes (from punctum books)

Fender the Fall (a sci-fi novella from Alien Buddha Press)

Abandoned Accounts (poetry collection from First Cut)

Thank you for your continued interest and support! It is appreciated.

Hope you're well,

-royc.

February 28, 2022

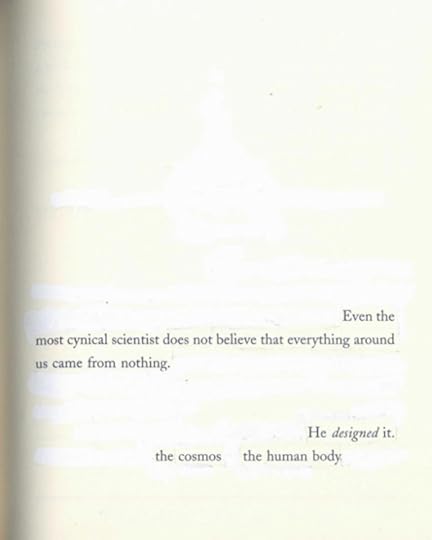

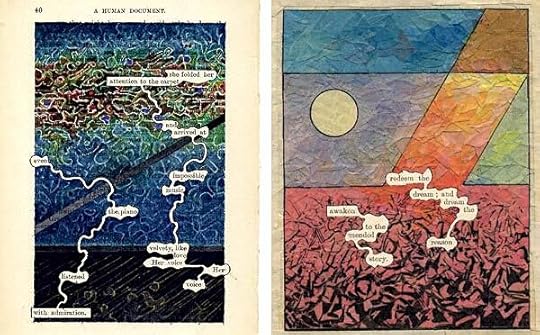

Revealing Poetry: The Art of Erasure

Erasure poetry both deconstructs and demonstrates the idea that books are bodies, playing operation with structure, doing surgery on syntax. My dear friend Danika Stegeman LeMay has a full book-length erasure of the text from God is in the Small Stuff for the Graduate by Bruce Bickel and Stan Jantz (Barbour Publications, 2004). It's called called GOD IS IN THE MALL, and an excerpt is available in Vol. 30 of Word for/ Word. This page gets right to it:

Danika's is the latest example of this practice I've seen done well, but the first was a while ago. Maybe it’s apt that I don’t remember exactly how or where, but I came across Tom Phillips‘ “treated Victorian novel,” A Humument (Tetrad Press, 1970), two decades ago at San Diego State University. Phillips took William Mallock’s A Human Document (Cassell Publishing, 1892) and obscured words on every page, leaving a few here and there to tell a new story. It’s part painting, part drawing, part collage, part poetic cut-up, and all weirdly, intriguingly unique.

Phillips claims that he picked A Human Document because of its price-point (“no more than three pence,” he said), but Mallock’s “novel” is oddly suited for Phillips’ repurposing. The original novel is a scrapbook of sorts of journal entries, correspondence, and other ephemera left behind by two deceased lovers. Mallock wrote of these scraps in his introduction that “as they stand they are not a story in any literary sense; though they enable us, or rather force us, to construct one out of them for ourselves.” In her book Writing Machines, N. Katherine Hayles characterizes this introduction as “uncannily anticipating contemporary descriptions of hypertext narrative.”

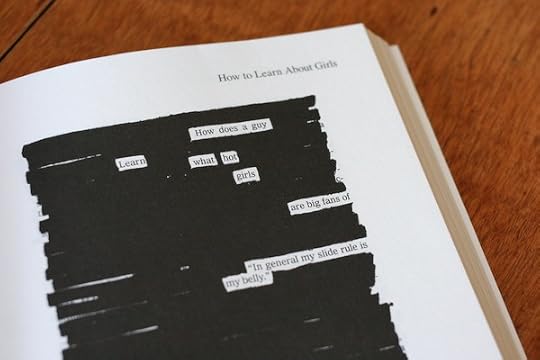

In a simpler example, Austin Kleon "stole like an artist" and created a best-seller using only markers and copies of The New York Times. His Newspaper Blackout (Harper Perennial, 2010) takes Tom Phillips’ methodology to its most basic tenet: poetry as erasure.

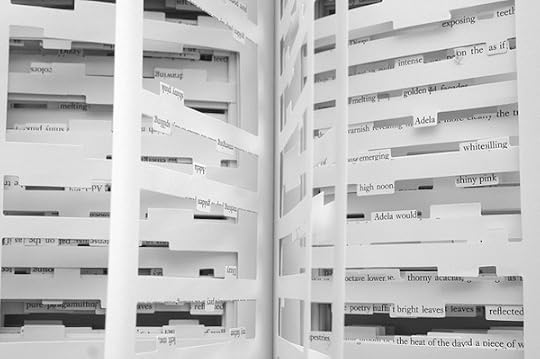

Taking a step up instead of down, Jonathan Safran Foer opted for physical subtraction, creating a textual sculpture. Foer treated his favorite novel, The Street of Crocodiles by Bruno Schulz (Penguin, 1963), by cutting out words, creating Tree of Codes (Visual Editions, 2010). You can watch the making-of on YouTube.

Giving due credit to his forebears, Foer told The New York Times, “It was hardly an original idea: it’s a technique that has, in different ways, been practiced for as long as there has been writing — perhaps most brilliantly by Tom Phillips in his magnum opus, A Humument. But I was more interested in subtracting than adding, and also in creating a book with a three-dimensional life. On the brink of the end of paper, I was attracted to the idea of a book that can’t forget it has a body.” Foer also acknowledges the project’s constraints as well as the power of his source material, adding,

Working on this book was extraordinarily difficult. Unlike novel writing, which is the quintessence of freedom, here I had my hands tightly bound. Of course 100 people would have come up with 100 different books using this same process of carving, but every choice I made was dependent on a choice Schulz had made. On top of which, so many of Schulz’s sentences feel elemental, unbreakdownable. And his writing is so unbelievably good, so much better than anything that could conceivably be done with it, that my first instinct was always to leave it alone.

For about a year I also had a printed manuscript of The Street of Crocodiles with me, along with a highlighter and a red pen. The story of Tree of Codes is continuous across pages, but I approached the project one page at a time: looking for promising words or phrases (they’re all promising), trying to involve and connect what had become my characters. My first several drafts read more like concrete poetry, and I hated them.

As opposed to the anyone-can-do-it tack of Kleon, Foer took the tools and text at hand and made something truly new. Like A Humument before it, Tree of Codes is a unique object worthy of thoughtful consideration. As DJ Scratch once said, “The reason we respect something as an art is because it’s hard as fuck to do.” Taking elements of others’ work and making it your own is one thing. Taking the whole damn thing and completely transforming it into something else is art.

15th ANNIVERSARY OF FOLLOW FOR NOW:

Today is the last day to take advantage of my 15th anniversary celebration offer! If you send me your receipt for the purchase of a paperback copy of Follow for Now, Vol. 2 from punctum books, I'll send you a signed copy of Vol. 1! Get all 80 interviews! Two decades of thought from minds of all kinds! If you're still not convinced, here's more about Vol. 2!

ICYMI:Also, in case you missed them in all of that, I have three (3!) new books out:

Follow for Now, Vol. 2: More Interviews with Friends and Heroes (from punctum books)

Fender the Fall (a sci-fi novella from Alien Buddha Press)

Abandoned Accounts (poetry collection from First Cut)

As always, thank you for your continued interest and support! It is appreciated.

Hope you're well,

-royc.

February 16, 2022

Announcements, Annotations, and an Anniversary

But first, it's the...

15th ANNIVERSARY OF FOLLOW FOR NOW:In February of 2007, with the help of several of my friends, I self-published my first book, the interview anthology, Follow for Now: Interviews with Friends and Heroes. Patrick Barber did the design (inside and out) and Adem Tepedelen did the copyediting, both of whom I worked with at The Rocket Magazine in Seattle in the 1990s. Other contributors include Mark Dery, Erik Davis, Tom Georgoulias, Brandon Pierce, Paul Barman, Paul D. Miller, and John Brockman, and the list of interviewees is too long to put here. It's really quite good!

To celebrate the 15th anniversary of the first volume, if you send me your receipt for the purchase of a paperback copy of Follow for Now, Vol. 2 from punctum books, I'll send you a signed copy of Vol. 1! Get all 80 interviews! Two decades of thought from minds of all kinds! If you're still not convinced, here's more about Vol. 2!

SEEDS TOSSED:I have a few pieces written and drawn on pages floating around this month and a few more coming up!

I have a story about hip-hop in 1981 in the new issue of Pulp Modern. The piece gave me an opportunity to correct some mistakes I made in my book Dead Precedents and in subsequent interviews. Pulp Modern is edited by Alec Cizak, and this one also includes pieces by Misha Burnett, Jeff Easterholm, Anthony Perconti, Ronin Heck, Scotch Rutherford, Robb White, and the baddest poet, Tia Ja'Nae.

I have another security-envelope collage in the new issue of Phantom Kangaroo. Phantom Kangaroo is the product of the magical and multitalented Claudia Dawson, and Issue #26 also includes words and images by Bernardo Villela, K. Johnson Bowles, Olga Gonzalez Latapi, Melissa Cannon, Ilaria Cortesi, Jason Brightwell, MJ McGinn, Amy Young, Anna Shirshova, Priyanka Kapoor, Barbara Candiotti, Steph Amir, Gareth Branwyn, Rebecca Davis, Alex Thayer, Donna Dallas, Zack Rogow, and J. Campbell.

I have an illustration coming out in the April issue of [Alternate Route]. Founded and edited by Michael Starr, [Alternate Route] is a quarterly independent literary magazine, and my drawing is from a dream I had about a crow taking a multiple-choice test. I'll send a link when it comes out.

I also have a short story coming out in an as-yet-unnamed anthology for Malarkey Books. I'm really excited about that because Malarkey has been very supportive of my writing the past couple of years. They published an excerpt from my next non-fiction book, Escape Philosophy: Journeys Beyond the Human Body (coming this summer from punctum books; see below), and the prologue to my novel-in-progress, Hope for Boats (no idea yet when that'll be finished!).

DELAYED BUT NOT DETERRED:Up next is the edited essay collection Boogie Down Predictions: Hip-Hop, Time, and Afrofuturism from Strange Attractor, which has been pushed back to a May 10th release due to global supply-chain issues. I am hopeful that the world will finally let this book come out then though. Here are more details, including the table of contents, back-cover blurbs, a nice review from The Wire Magazine, etc. The list of contributors on this thing is staggering, if I do say so myself! Hold tight!

MOST METAL MERCH:As I mentioned above, Escape Philosophy: Journeys Beyond the Human Body is coming out this summer from punctum books. What I didn't mention is that I am hand-screening T-shirts and back-patches of the cover image that Matthew Revert and I did! Pictured above is my test print. This might be my only book project where such Metal merch is appropriate, so I'm going all out. I'll let you know when they're available.

ONLINE AGAIN:I just built a new website for my media-theory book-in-progress, The Medium Picture. It's full of excerpts and book-adjacent essays. I'll have an announcement about this one soon. In the meantime, check out the website!

ONE MORE THING:

My friends Patrick Barber, Craig Gates, and I have been working on a new zine called discontents. The sticker above was designed by Craig and I (I did the Thrasher knock-off logo; He did the drawing and the final layout). The pilot issue includes writing by Cynthia Connolly, Peter Relic, Andy Jenkins, Spike Jonze, Fatboi Sharif, Timothy Baker, and Greg Pratt, artwork by Zak Sally and Tae Won You, as well as work by Patrick, Craig, and myself. Subjects include Ceremony, Unwound, Tony Rice, Hsi-Chang Lin a.k.a. Still, Charles Yu's Interior Chinatown, Crestone director Marnie Elizabeth Hertzler, Coherence director James Ward Byrkit, and others. More on this project as we wrap it up. Soon!

ICYMI:Also, in case you missed them in all of that, I have three (3!) new books out:

Follow for Now, Vol. 2: More Interviews with Friends and Heroes (from punctum books)

Fender the Fall (a sci-fi novella from Alien Buddha Press)

Abandoned Accounts (poetry collection from First Cut)

I think that's about it, besides a couple of things I can't tell you about yet...

What ch'all been doing?

Thank you all for your continued interest and support! It is appreciated.

Hope you're well,

-royc.