Roy Christopher's Blog, page 10

March 14, 2023

New Fossils, New Futures

In mid-March 2019, Repeater Books published Dead Precedents: How Hip-Hop Defines the Future. Its central argument is that the cultural practices of hip-hop are the cultural practices of the 21st century. In what Walter Benjamin would call correspondences, I use evidence from cyberpunk and Afrofuturism to make the book’s many claims.

Jeff Chang, author of Can’t Stop, Won’t Stop and co-editor of Freedom Moves, says, “Roy Christopher’s dedication to the future is bracing. Dead Precedents is sharp and accelerated.” Samuel R. Delany calls it “a book with so much energy and passion in it… a lively screed.”

What follows is the brief essay that serves as the Preface to Dead Precedents.

If you don’t know, now you know.

How Hip-Hop Defines the Future

“Space, that endless series of speculations and origins — of rebirths and electric spankings — is here not so much a metaphor as it is a series of fragmented selves, a place of possibilities and debris and explorations and atmosphere.”

— Kevin Young, The Grey Album: On the Blackness of Blackness

“Let us imagine these hip-hop principles as a blueprint for social resistance and affirmation: create sustain- ing narratives, accumulate them, layer, embellish, and transform them.”

— Tricia Rose, Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America

Several years ago, on one of my online profiles under “books” I listed only Donald Goines and Philip K. Dick. If you don’t know them, Donald Goines wrote about himself and his associates and their struggles as street hustlers, pimps, players, and dopefiends. Philip K. Dick wrote about the brittleness of reality, its wavy, funhouse perceptions through drugs and dreams. Goines wrote sixteen books in five years and Dick wrote forty-four in thirty. Both were heavy users of mind-altering substances (heroin and amphetamines, respectively), and both helped redefine the genres in which they wrote. They interrogated the nature of human identity, one through the inner city and the other through inner space.

The world according to Donald Goines and Philip K. Dick: one through the inner city and the other through inner space.

The world according to Donald Goines and Philip K. Dick: one through the inner city and the other through inner space.While I am certainly a fan of both authors, I posted them together on my profile as kind of a gag. I thought their juxtaposition was weird enough to spark questions if you were familiar with their work, and if you weren’t, it wouldn’t matter. I had no idea that I would be writing about the overlapping layers of their legacies so many years later.

To retrofit a description, one could say that Goines’ books are gangster-rap literature. They’re referenced in rap songs by everyone from Tupac and Ice-T to Ludacris and Nas. In many instances, Dick’s work could be called proto-cyberpunk. The Philip K. Dick Award was launched the year after he died, and two of the first three were awarded to the premiere novels of cyberpunk: Software by Rudy Rucker in 1983 and Neuromancer by William Gibson in 1985.

[Ed note: If you’re interested, wrote a bit about the connections between hip-hop and literature for Literary Hub for the book’s release.]

When cyberpunk and hip-hop were both entering their Golden Age, I was in high school. One day I was walking up my friend Thomas Durdin’s driveway. By the volume of the AC/DC sample that forms the backbone of Boogie Down Productions’ “Dope Beat,” I knew his mom wasn’t home. Along with the decibel level, I was also struck by how the uncanny pairing of Australian hard rock and New York street slang sounded. It was gritty. It was brash. It rocked. De La Soul’s 1996 record, Stakes is High, opens with the question, “Where were you when you first heard Criminal Minded?” That moment was a door opening to a new world.

I didn’t realize it then, but that new world was the twenty- first century, and hip-hop was its blueprint.

Boogie Down Productions Criminal Minded, side B, track 1: “Hope Beats.”

Boogie Down Productions Criminal Minded, side B, track 1: “Hope Beats.”I distinctly remember that the label on the record spinning around on Thomas’s turntable incorrectly named the song “Hope Beats.” An interesting mistake given that DJ Scott La Rock was killed just months after the record came out, prompting KRS-One to start the Stop the Violence movement. Where Criminal Minded is often cited as a forerunner of gangster rap, KRS-One was thereafter dedicated to peace. I’d heard hip-hop before, but the unfamiliar familiarity of the “Back in Black” guitar samples in that song make that particular day stick in my head.

Long before hip-hop went digital, mixtapes—those floppy discs of the boombox and car stereo—facilitated the spread of underground music. The first time I heard hip-hop, it was on such a tape. Hiss and pop were as much a part of the experience of those mixes as the scratching and rapping. We didn’t even know what to call it, but we stayed up late to listen. We copied and traded those tapes until they were barely listenable. As soon as I figured out how, I started making my own. We watched hip-hop go from those scratchy mixtapes to compact discs to shiny-suit videos on MTV, from Fab 5 Freddy to Public Enemy to P. Diddy, from Run-DMC to N.W.A. to Notorious B.I.G. Others lost interest along the way. I never did.

A lot of people all over the world heard those early tapes and were impacted as well. Having spread from New York City to parts unknown, hip-hop became a global phenomenon. Every school has aspiring emcees, rapping to beats banged out on lunchroom tables. Every city has kids rhyming on the corner, trying to outdo each other with adept attacks and clever comebacks. The cipher circles the planet. In a lot of other places, hip-hop culture is American culture.

Though their roots go back much further, the subcultures of hip-hop and cyberpunk emerged in the mass mind during the 1980s. Sometimes they’re both self-consciously of the era, but digging through their artifacts and narratives, we will see the seeds of our times sprouting. We will view hip-hop not only as a genre of music and a vibrant subculture but also as a set of cultural practices that transcend both of those. We will explore cyberpunk not only as a subgenre of science fiction but also as the rise of computer culture, the tectonic shifting of all things to digital forms and formats, and the making and hacking thereof. If we take hip-hop as a community of practice, then its cultural practices inform the new century in new ways. “I didn’t see a subculture,” Rammellzee once said, “I saw a culture in development.”

The Equation: RAMMELLZEE. [Photo by Timothy Saccenti.]

The Equation: RAMMELLZEE. [Photo by Timothy Saccenti.]The subtitle of this book could just as easily be “How Hip-Hop Defies the Future.” As one of hip-hop culture’s pioneers, Grandmaster Caz, is fond of saying, “Hip-hop didn’t invent anything. Hip-hop reinvented everything.” To establish this foundation, we will start with a few views of hip-hop culture (Endangered Theses), followed by a brief look at the origins of cyberpunk and hip-hop (Margin Prophets). We will then look at four specific areas of hip-hop music: recording, archiving, sampling, and intertextuality (Fruit of the Loot); the appropriating of pop culture and hacking of language (Spoken Windows); and graffiti and other visual aspects of the culture (The Process of Illumination). From there we will go ghost hunting through the willful haunting of hip-hop and cyberculture (Let Bygones Be Icons). All of this in the service of remapping hip-hop’s spread from around the way to around the world and what that means for the culture of the now and the future (Return to Cinder).

The aim of this book is to illustrate how hip-hop culture defines twenty-first-century culture. With its infinitely recombinant and revisable history, the music represents futures without pasts. The heroes of this book are the architects of those futures: emcees, DJs, poets, artists, writers. If they didn’t invent anything but reinvented everything, then that everything is where we live now. Forget what you know about time and causation. This is a new fossil record with all new futures.

Get Up On It! Your humble narrator with the book at Quimby’s in Chicago. [Photo by Liz Mason.]

Your humble narrator with the book at Quimby’s in Chicago. [Photo by Liz Mason.]Taking in the ground-breaking work of DJs and emcees, alongside writers like Philip K. Dick and William Gibson, as well as graffiti and DIY culture, Dead Precedents is a counter-cultural history of the twenty-first century, showcasing hip-hop’s role in the creation of the world in which we now live. As the book concludes, “We’re not passing the torch, we’re torching the past.”

I’m really quite proud of this book. If you don’t have it, let me know how we can fix that.

As always, thank you for reading,

-royc.

March 7, 2023

Ian MacKaye: Epic Problem

Ian MacKaye is a lot of things, but he’s best known as the co-founder of Dischord Records and the bands Minor Threat and Fugazi. One of the ways he came to punk practices was through skateboarding, which he describes as a discipline, a way to reinterpret the world. Punk, as he explains below, is also a way to reinterpret the world. If languages are our lenses, then these are his native tongues.

[Portrait by Roy Christopher]

[Portrait by Roy Christopher]I found Minor Threat in high school, after they’d already broken up. I got both of their cassettes at a record store in a mall on a trip through in Huntsville, Alabama. From there, I followed Ian through string of bands—Egghunt, Embrace, Pailhead—but when Fugazi came together, it was clear that something else was going on. My friends and I didn’t know that their first self-titled EP was the beginning a phenomenal 15-year run, but we knew it was something special. Where Minor Threat helped define the genre of hardcore, Fugazi was beyond that, a little bit outside of the genres we knew at the time. I remember driving to the skatepark in my 1973 VW Beetle shortly after getting that first tape. My friend Sean Young sat in the passenger seat rewinding “Waiting Room” over and over the whole way there. The opening chords of that song sound as fresh now as they did then.

Fugazi went on an indefinite hiatus the same year that MySpace launched. The timing is significant because MySpace briefly became the online place for music, for bands and fans alike. In 2018 they lost 12 years of their users’ files in a server migration catastrophe. The lost files include everything uploaded between 2003 and 2015, over 50 million songs by 14 million artists, as well as countless photos and videos. As we offload and outsource our archives to these services, we run the risk of losing them without recourse.

If there’s a lesson there, it’s the same one MacKaye lives by: self-reliance. He’s been keeping his own archives all his life, but I’ll let him tell you about that.

Roy Christopher: You and I both came up and were introduced to this culture through skateboarding. How did you initially get into punk?

Ian MacKaye: It was around late ‘78 that I first encountered punk—really encountered it—meaning that I thought about it. I’d obviously seen it years earlier because the media was talking about it, but my friends in high school started talking about it, and I started to really have to give it a think. One of the dilemmas of punk for me at the time was that punk and skateboarding were opposite. So, the punks that I knew would never skateboard because that just seemed silly, and the skateboarders I knew just thought punks were freaks. Of course, the skateboarders were largely guys who were jocks or who just wanted to party, so it made sense that they would hate something new. I had to make this decision about wanting to be a punk or a skateboarder. Now the good thing about skateboarding, given that navigation was so central to the practice, is that it was like learning a language. They say that it's easier to learn a language if you've learned another language, and I think it's because you've gone through the process of reshaping sound already so you understand that it can be done, you can communicate with different sounds. So, I think in the same light, the time I spent skateboarding and looking at the world differently was perfect practice and preparation for punk. Because punk required looking at the world differently.

RC: Oh, yeah.

IM: It was actually in many ways a perfect way to enter it. Now, ironically, as we all know, punk and skateboarding became almost synonymous later on, which is not surprising to me, but at the time it was separate. It didn't occur to me since I wasn't living in Los Angeles where you had the first skaters who really got into punk. They picked up on the sort of the radicalness for the freedom of it or whatever. You have Steve Olson or Dwayne Peters, Tony Alva, Jay Adams, and that crew, once they got into it, then suddenly, like within a couple years, you had skate punks.

RC: Yeah, by the time I came in, which was during the Bones Brigade era, they were already merged.

IM: Right, exactly.

RC: I didn't know this about you, but I found out recently that you don't have any effects on your guitar, and you did that on purpose because you wanted to push those limits.

IM: Not only that, but I'm anti-option. I've been a vegan for 35 years and whenever somebody asks me why, I always say, ‘why not?’ Because there's a million great reasons to think about what you put in your body. The primary one is convenience, which is of course the death of the world, but I think that one of the great silver linings for me, especially in the olden days—not so much now because now it's become more common—but what was so wonderful was that I didn't have to spend a lot of time looking at a menu because there was one thing, and I was going to eat.

I like simple things like just in general. I think options are designed to confuse and delay. Another reason that I think there are so many options in our marketplace especially is to create sort of brand obedience. For instance, if you go to a larger grocery store and you go to their bakery section and you want to buy some bread, there's usually about, 25 different kinds of bread, which is a lot of different kinds of bread when you think about it! Or cereals. There's like 50 cereals! Yeah. That's a lot of cereals, but I think the only way that one can retain their sanity and navigate that many choices every time is to pick the one thing, right?

RC: Right.

IM: They pick the one kind of bread that they like. With the cacophony of options, they just reach in and grab the one, but here's the thing: They're all owned by one or two bakeries anyway.

The illusion is that we have all these choices we can make, but the net effect is that we don't make choices because there are so many that they become incomprehensible. You can't deal with it, so you just end up buying the one thing or getting the one kind of gas or the one whatever. I’m not suggesting that there were some evil geniuses thought this up [laughs]. I'm not like that. I'm not like a paranoid dude or a conspiracy guy, but—and this is a little bit like the skateboarding thing—I just learned how to look at things differently.

So, for me, options sort of get away from the beauty of a simple life. So, when you were talking about my guitar, yes, it's true. I don't like pedals. I never used them. I just thought it was interesting to just have one setup and then to use my body and the available volume knobs, the tone knobs, those things on my guitar and on the amp. What can I do to manipulate those things to create a variety of sounds, without having a computer just dial them up for me. I think one of the reasons that society is in a bit of a malaise is because of computers. The options provided by computers are completely overwhelming.

My original Minor Threat and Fugazi cassettes.

My original Minor Threat and Fugazi cassettes.For those of us who were pre-internet and post-internet, we can really see the distinction. I'm not a Luddite and I'm not nostalgic. I don't care about any of that. But the reality is that the relationship I had with music at a time where I would only be able to afford one or two records, and I would just have to go and listen to that record until I get to save up for the next record. I would listen to one record, you know, 40 times in a row. That experience is much more difficult when you have 4 million musical choices at your fingertips.

RC: How do you even know what you like?

IM: Right?! As a resource, it's amazing. There's a lot of times I'll read some book about music, and they'll mention some very obscure recording, and then I look and boom, I find it. I can't believe it's all there. So, I love the resource aspect of it, but I do think that that the relationship that I developed with music, maybe it's harder. I don't know. Because looking at my kid and other kids, they love music, but they're kind of overwhelmed with options and choices.

So, I'm a little tongue-in-cheek when I say convenience is the death of the world, but I think options and convenience are cousins for sure.

RC: You could definitely make the argument.

IM: I like fewer options.

RC: I struggle with my students to get them to take notes or pay attention to things that they don't need right at the moment because they live in such an on-demand kind of culture. You have created an archive—a Dischord archive, a Fugazi archive—and that's one of the things that I've been trying to argue with them is that they need to be holding onto their own stuff and not relying on companies online. So, what was the impetus to build this massive archive of your stuff.

IM: Well, I mean, the Fugazi Live Archive is just one part of a much larger archive of Dischord- and Fugazi-related materials. I think the impetus starts with a very simple reality, which is I am 60 years old, and in my entire life I've only lived in three houses. I own two of them, and my dad still lives in the first one. As a result, I didn't have to make that kind of painful choice about what I'm bringing and what I'm leaving or throwing away. So, there's that. That's just a reality. Then my mother was a journalist in the true sense of the word in that she kept journals for 60 of her 70 years. Not only did she keep journals, but she also typed them up and edited them. She kept filing cabinets of journals, letters, correspondence, genealogical work. She was an absolutely brilliant, brilliant person. She had a Panasonic cassette deck, and she would just leave it recording in a room. I used to think it was nice that mom liked to hear our voices when we were away, that she would record us. It wasn't until she died that I realized, it wasn't for her. It was for us, so we can hear her voice.

There was an emphasis on the idea of hanging on to things because they would take a different form as time passed. Maybe they would become more important, and you can always throw something away later. It's not like you have to make that decision can today. Later you can put it in the trash, but if you don't need to throw it away now, then maybe don't.

Then the next level is that I met Jeff Nelson in high school. He was in the Slinkees, and the Teen Idles. He's my partner at Dischord Records. Jeff is a saver, a collector. I got hit by a car once and years later, I found that he went out and he scooped up all the pieces of the shattered headlight that broke. He still had that stuff. It's just the way he is. He just has that kind of mentality, which I think resonated with my own tendency. So, both of us were just saving things because we thought they were important. I mean, you have to remember that this why Dischord Records was started: Not because we wanted to have a record label, but because we wanted to document something that was important to us. We didn't think the world need to have a Teen Idles record. We wanted the Teen Idles record. It was important to us. So, things that were important to us, we hung onto, and we continue hang onto.

As a result of all those things I've just described you, these different circumstances, I essentially ended up with this massive collection of things. About 10 or 12 years ago, I had a number of friends die, and one of the friends who died, he had named a mutual friend to be the executor of his will. At some point, I asked our mutual friend how it went, and he said it was the greatest of gifts. Our late friend had basically identified, enumerated, and directed everything he had. I thought about it, and you know, my brain is big, and I know everything in Dischord House, but my brain stops when I die. So, I realized that I have all this stuff, but if I died and Amy and the others were going to have to contend with it, figure out what to do with it all. It was all mixed up because my life, my personal life and my musical life and the label life were all tied together. I know everything, but that's what really got me thinking about time to start cleaning up and get things organized. I still have miles to go, but at least now things have been split.

I have all my personal correspondence at home, my other house: 40 years of correspondence. I saved all the letters that people sent me—90% of them or something. So, I had boxes of these letters in my eaves, and I sat for four years with an archivist named Nichole Procopenko, and we went through every letter. We put into a collection. We have a large collection that breaks down into different subsets, and now it's researchable.

RC: Oh, that's amazing.

IM: So, someone calls and says, ‘I'm looking for this early-eighties punk from Des Moines,’ and I'm like, ‘I can help you!’ [laughs] I freak people out because I can lay my hands on things almost instantly that are in the database. It's all organized. Same with the tapes and fanzines and photos. That's the archive. People keep saying, ‘aren't you going to scan everything?’ No, I'm not. I have scanned the flyers because they're the most liquid of things.

The other thing about it, which is interesting, is a part of what has affected your students is that… I can't say this for sure, but I strongly suspect that the punk scene is probably the last youth movement that used paper. Like I know hip-hop came a little bit after punk, I just don't think people are using as much paper. They weren't corresponding as much. I think that there's something really interesting about that. I think it's important too, because the world that I'm a part of and was a part of back then was one that was beneath the radar of the industry, and since the industry controls history, that's their job. The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, they celebrate industry figures. The Grammys every year hand out awards for best Song of the Year, but every one of those songs, if not on an actual major label, it's distributed by a major label. What are the chances that of all the songs that are being written in the, in the world on any given minute of any given day, that every single best song of the year happened to go through a major? Statistically impossible. But that's the way it works. They own the history. So as a result, knowing that, I feel like it's important to hang on to evidence of prior civilization, the pottery shards that let people know that they weren't the first.

RC: Those are awesome stories, Ian. I won't take up any more of your time. I appreciate it. I'm glad we finally got to do this.

IM: All right, my friend. Good talking to you. If you ever find yourself in Washington, drop me a line, and I'll show you this madness. You'll probably get a kick out of it.

The Medium Picture

This interview was initially conducted to inform my forthcoming book, The Medium Picture, and it did! But it turned out so good that Ian and I decided to share the whole thing with you.

About the book, Howard Rheingold says, “If you want to understand the social, psychological, cultural effects of the media explosions of the past 50 years, The Medium Picture — thoughtful, comprehensive, and deep — is for you. Immersed in the contemporary digital culture he grew up with as a teenager, the Gen-X author is old enough to recall vinyl, punk, and zines — social media before TikTok and smartphones. The Medium Picture deftly illuminates the connections between post-punk music critique, the increasing virtualization of culture, the history of formal media theory, the liminal zones of analog vs digital, pop vs high culture, capitalism vs anarchy. The Medium Picture is the kind of book that makes you stop and think and scribble in the margins.”

Many thanks to Ian for taking the time, to Howard for the kind words, and to you for reading.

Thank you,

-royc.

March 1, 2023

The Bitten Word

For anyone who’s tried it, writing is challenging in many different ways and at many different stages. The writing process itself is long and full of its own inherent challenges, but getting editors or agents to read and publish your work presents another course of obstacles. Once you’ve written something and gotten it published, the last challenge is getting people to read it.

My friend Gareth Branwyn always says, “Writers write.” Writing and publishing are privileges, and I take both the work and the opportunity seriously. So, I appreciate your time and attention when I invade your inbox every week or so.

Thanks for reading Roy Christopher! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

What follows is a roundup of a few things I’ve recently gotten published in one form or another, with thanks to the editors and publishers who found these words worthy.

The Bitten Word

I have a piece (and an illustration) up today called “The Bitten Word” on Lit Reactor. As I did in a newsletter a while back, I propose a writing exercise based on interpolating the work of others. Here’s an excerpt:

Quoting and paraphrasing are common in writing disciplines such as journalism and academia, but plagiarism is anathema, punishable by excommunication. While endemic to the creative practices of hip-hop, the practice of interpolation also hotly debated. The orthodox rule there was no biting, but if you can take what someone else wrote and make it better, that’s worthy of respect. “I can take a phrase that’s rarely heard,” Rakim once rapped, “Flip it, now it’s a daily word.” Because of the perils of plagiarism, in writing practice, riffing on the work of another is not widely accepted, but it can be quite fruitful.

Read the full column at Lit Reactor.

Phantom Kangaroo Newsletter

My “Calm in the Chaos” security-envelope liner collage that first appeared in issue #26 of Phantom Kangaroo was in the first edition of the new PK weekly newsletter, both of which are edited by the magical and multi-talented Claudia Dawson. You should subscribe to this and her Many-Worlds Vision newsletter immediately.

Irony is for Suckers

I know you read it already, but my essay on irony from a few weeks ago is up on Sublation Magazine. Here’s the beginning:

“Irony used to feel like a defense against getting played,” writes the novelist Hari Kunzru, “a way for a writer to ward off received ideas and lazy thinking.” Broadly speaking, irony is the rhetorical strategy of saying one thing yet meaning another, usually the opposite. It also might be the most abused trope of our time. It’s beyond substance over style. It’s the absurd over the authentic. “It also made us feel nihilistic and defeated,” Kunzru continues. “More recently we’ve seen how it can be a screen for reactionary politics.” In the preface to his 1999 book, For Common Things, Jedidiah Purdy frames the overbearing irony of our era as a defense mechanism: "It is a fear of betrayal, disappointment, and humiliation, and a suspicion that believing, hoping, or caring too much will open us up to these." It’s an escape route, an exit strategy, a way off the hook in any situation, it’s become the dominant mode of pop culture, and we’re all tired of it.

Thanks to Alfie Bown for giving this one a second home. If you missed it somehow, you can read the full piece at Sublation.

“Messing with time, unsettling histories, opening portals.”

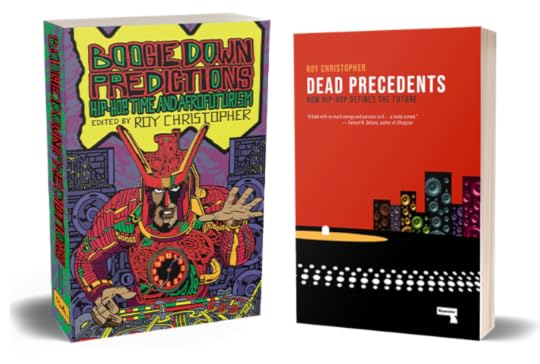

As you know, I have a couple of new books out. I’m still trying to spread the word, so if you know anyone who might be interested in either of these, let ‘em know.

BOOGIE DOWN PREDICTIONS: Hip-Hop, Time, and Afrofuturism

(Strange Attractor Press)

Jeff Chang, author of Can’t Stop, Won’t Stop and co-editor of Freedom Moves, says,

Roy Christopher’s dedication to the future is bracing. Boogie Down Predictions is a symphony of voices, beats, and bars messing with time, unsettling histories, opening portals.

Through essays by some of hip-hop’s most interesting thinkers, theorists, journalists, writers, emcees, and DJs, Boogie Down Predictions embarks on a quest to understand the connections between time, representation, and identity within hip-hop culture and what that means for the culture at large. Introduced by Ytasha L. Womack, author of Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture, this book explores these temporalities, possible pasts, and further futures from a diverse, multilayered, interdisciplinary perspective.

Featuring contributions from Omar Akbar, Juice Aleem, Tiffany E. Barber, Kevin Coval, Samantha Dols, Kodwo Eshun, Chuck Galli, Nettrice Gaskins, Jonathan Hay, Jeff Heinzl, Kembrew McLeod, Rasheedah Phillips, Steven Shaviro, Aram Sinnreich, André Sirois, Erik Steinskog, Dave Tompkins, Tia C.M. Tyree, Joël Vacheron, tobias c. van Veen, K. Ceres Wright, and Ytasha Womack.

ESCAPE PHILOSOPHY: Journeys Beyond the Human Body

(punctum books)

We are all perpetually holding ourselves together. Our breath, our blood, our food, our spit, our shit, our thoughts, our attention—all tightly held, all the time. Then at death we let it all out, oozing at once into the earth and gasping at last into the ether.

The physical body has often been seen as a prison, as something to be escaped by any means necessary: technology, mechanization, drugs, sensory deprivation, alien abduction, Rapture, or even death and extinction. Taking in horror movies from David Cronenberg and UFO encounters, metal bands such as Godflesh, ketamine experiments, AI, and cybernetics, Escape Philosophy is an exploration of the ways that human beings have sought to make this escape, to transcend the limits of the human body, to find a way out.

As the physical world continues to crumble at an ever-accelerating rate, and we are faced with a particularly 21st-century kind of dread and dehumanization in the face of climate collapse and a global pandemic, Escape Philosophy asks what this escape from our bodies might look like, and if it is even possible.

Eugene Thacker, author of In the Dust of This Planet writes, “Too often philosophy gets bogged down in the tedious ‘working-through’ of contingency and finitude. Escape Philosophy takes a different approach, engaging with cultural forms of refusal, denial, and negation in all their glorious ambivalence.”

As always, thank you for reading and sharing.

More soon,

-royc.

Thanks for reading Roy Christopher! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

February 21, 2023

Shoegazing at Stars

In his new memoir, Spaceships Over Glasgow, Mogwai’s Stuart Braithwaite describes his teen years in terms eerily similar to my own: waiting eagerly for The Cure’s Disintegration to come out, whiling away the summer skateboarding, waiting to see them on “The Prayer Tour” in 1989. I did all of those things. Our paths diverged when he started making music and I started making zines. When he picked up a guitar, I picked up a copy-machine. We still revere the power of music in the same manner though.

Pedal Power: Mogwai live. Photo by Leif Valin.

Pedal Power: Mogwai live. Photo by Leif Valin.I’ve always thought of music as being romantic. It can take you from wherever you are to somewhere else in an instant. When I was a teenager, in particular, I romanticized about music and musicians endlessly. I’d daydream about how records were made and what the lives of those making them were like. The music itself would set fires in my imagination.

The son of Scotland's last telescope-maker, Braithwaite was perhaps destined for a life looking beyond the limits, his head aflame with sound. Once armed with his first guitar and exposed to the post-punk noise of the Jesus and Mary Chain and Sonic Youth and the shoegazing drone of My Bloody Valentine and Ultra Vivid Scene, as well as the goofy goth of The Cure, of course, he was on his way to the stars.

Thanks for reading Roy Christopher! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Some of my old listening stats from Last.FM.

Some of my old listening stats from Last.FM.Mogwai is consistently one of my most-listened-to bands. Their blend of mellow prog, raging guitars, and soundtracky drama has held my attention for years. It’s no wonder they’ve scored several films throughout their nearly 30-year career. There’s a lot of slowly building tension and cathartic release. For a long time there were no vocals, and for a while after there were, I didn’t hear them. They were disguised, machine voices, awash in layers of guitar squall and feedback, vocoded beyond recognition.

Even with a space seemingly cut out for them by a family of description-defying groups, ready-made genres, and audiences lying in wait, some sounds still don’t seem to fit anywhere. When genre-specific adjectives fail, we grasp at significant exemplars from the past to describe new sounds. Following Will Straw, Josh Gunn calls this “canonization”: The synecdochical use of a band’s name for a genre is analogous to our using metaphors, similes, and other figurative language when literal terms fall short. Where bands sometimes emerge that do not immediately fit into a genre (I’m thinking of Godflesh, Radiohead, or dälek) or adhere too specifically to the sound of one band (e.g., the early 21st-century spate of bands that sound like Joy Division), we run into this brand of genre trouble.

Post-rock would seem to be just such a genre. Ever since Simon Reynolds posited the word as “perhaps the only term open ended yet precise enough to cover all this activity” in The Wire in 1994, there has been a post-everything-else. Sometimes it’s just lazy writing, sometimes it’s for marketing purposes, and every once in a while a genre has truly emerged alongside its parent designation. There seems to be very little consensus on exactly where rock crossed the line and became something else, but the desire to push rock past its limits has surely been around since those limits were established.

Even so, the roots of what has become post-rock run deep and in many directions, from previous genres like prog, ambient, jazz, industrial, techno, and Krautrock in general, to specific acts like CAN, Brian Eno, PiL, Jim O’Rourke, and others. Just when you think post-rock is too narrow a designation for the bands discussed, with one quick list, one sees how wide its waves crash. Jack Chuter’s 2015 book, Storm Static Sleep: A Pathway Through Post-Rock, goes as far back as the New Romanticism of Talk Talk and its separate ways before moving on to Slint and Slint-inspired rock.

If any band is worthy of its own genre, it is Slint: a band certainly more talked-about than listened-to. About such talking and genres as they emerge in writing, the media historian Lisa Gitelman writes,

As I understand it, genre is a mode of recognition instantiated in discourse. Written genres, for instance, depend on a possibly infinite number of things that large groups of people recognize, will recognize, or have recognized that writings can be for.

As both Straw and Gunn describe canonization above, Gitelman contends that genres emerge from discourse, the talked-about. Subsequently, we internalize them. They are inside us. She continues,

Likewise genres—such as the joke, the novel, the document, and the sitcom—get picked out contrastively amid a jumble of discourse and often across multiple media because of the ways they have been internalized by constituents of a shared culture. Individual genres aren’t artifacts, then; they are ongoing and changeable practices of expression and reception that are recognizable in myriad and variable constituent instances at once and also across time. They are specific and dynamic, socially realized sites and segments of coherence within the discursive field.

With all of that said, the brand of post-rock that I am drawn to owes more to Mogwai than to Tortoise (e.g., Explosions in the Sky, This Will Destroy You, Godspeed You! Black Emperor, God is an Astronaut, Kinski, Hovercraft, Flying Saucer Attack, and Mogwai themselves, of course). Where Tortoise tends toward a sparse shuffle and strum, Mogwai has a propensity for layers of bump and rumble. Structurally, if the former were a lattice partition, the latter would be a brick wall. This is not to paint Tortoise (and their brethren, June of 44, Rodan, Rachel’s, The Shipping News, et al.)—or Slint—out of the picture. One of my all-time favorite bands, A Minor Forest, owes at least some of their sound to Slint. Any band pursuing this aural area has to contend with the mathematics of Tortoise and Slint, the guitar textures of Mogwai and My Bloody Valentine, the orchestrations of The Cure and Radiohead, and the electronic experiments of Aphex Twin and Autechre, among others. There’s a there in there somewhere.

It isn’t all taken so seriously though. One look at the track list on any post-rock record, and you’ll see that. Mogwai’s “Like Herod” from Young Team (1997) was named for the mishearing of someone saying “lightheaded.” Incidentally, that song’s working title was “Slint,” pointing to a post-rock cross-pollination years before Slint’s David Pajo sang back-up on “Take Me Somewhere Nice” from Rock Action (2001), which was notably as far from Slint as they’d ever sounded at the time.

It would be remiss of me not to mention Happy Songs for Happy People (2003) and Mogwai’s latest, As the Love Continues (2021). The former has been my main going-to-bed record for almost two decades now, since I picked up the CD at Off the Record in San Diego the day it came out. The latter is not only their newest record, it’s one of their best. Almost 30 years on, they’re still pushing themselves and making their best music. Not bad for the son of a telescope-maker and his music-obsessed friends.

It doesn’t matter what you call it, but noting the gauziness of genre doesn’t necessarily negate the pursuit of classification. As radically subjective as music fandom can be, it’s nice to have some buoys floating about.

Further Reading:

Stuart Braithwaite, Spaceships Over Glasgow: Mogwai, Mayhem, and Misspent Youth, London: White Rabbit, 2022.

Jack Chuter Storm Static Sleep: A Pathway Through Post-Rock, London: Function Books, 2015.

Lisa Gitelman, Paper Knowledge: Toward a Media History of Documents, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014.

Jeanette Leech, Fearless: The Making of Post-Rock, London: Jawbone Press, 2017.

Simon Reynolds, Shaking the Rock Narcotic, The Wire, May 1994.

The Music is the MethodIf you enjoy this blend of music criticism and media theory, keep an eye out for my forthcoming book, The Medium Picture. I approach the study of media technology through music recording and its playback. The technologies involved in commodifying and consuming music have a rich history, and I leverage a brief version of it in the book.

Available as a free, open-access .pdf or standard paperback from punctum books.

Available as a free, open-access .pdf or standard paperback from punctum books.I apply a similar method in my recent book, Escape Philosophy: Journey’s Beyond the Human Body (punctum books, 2022). As Tobias Carroll writes in Heavy Feather Review,

Does the band Godflesh explain the current human condition? Before reading Escape Philosophy, I’d have been skeptical of this idea; now, I think I’m thoroughly on board. Christopher invokes the work of a number of artists who blend the transgressive and the transcendental (the aforementioned Godflesh, David Cronenberg, and dälek, among many others) and arrives at a new way of viewing the present moment.

More information, blurbs, reviews, and excerpts are available on my website.

As always, thank you for reading, responding, and spreading the love.

Power to you,

-royc.

Thanks for reading Roy Christopher! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

February 14, 2023

It Might Blow Up, but It Won't Go Pop

I was planning to revisit my interview with Posdnous of De La Soul next month when their catalog can finally be streamed online. I’m not a user of those services, but the absence of their work is a major hole that will be filled on March 3rd. If you’re not familiar, you should get that way.

Maseo, Trugoy, and Posdnous: De La Soul circa 1990.

Maseo, Trugoy, and Posdnous: De La Soul circa 1990.With the loss of Trugoy the Dove this week, there’s a new, more significant hole. With his delivery, somehow both soft and strong, he was my favorite member of the group. He made it all seem so effortless, casual even. His lyrics are ones I often cite as the reason I’ve stayed enamored with hip-hop since I first heard it and the reason I’ve made its study a significant part of my scholarly career. I’m still parsing his paragraphs.

Thanks for reading Roy Christopher! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

I met Dave only once, at the Fenix Underground in 1996 about 2 weeks after I did the interview with Pos below. He was cordial and kind, and the brief encounter reinforced my love of his music. His presence and prowess will be sorely missed in hip-hop, music, and this world.

The following piece was originally published in frontwheeldrive zine #47 in January 1997.

Stakes is Still HighIn 1989 when BDP’s Ghetto Music came out, my man Thomas (my main source for what was solid as far as Hip-hop was concerned) said he would tape it for me. What he failed to mention was that he was putting something else on the B-side… That tape changed the way I viewed the entire genre of Hip-hop. The songs on the flip of KRS-One’s usual positive raps were from De La Soul’s Three Feet High and Rising (Tommy Boy, 1989) . This was the first record that spoke freely about the ills of Hip-hop so far. It was the first anti-rap rap record. I wasn’t the only one geeked either: Kids who’d never thought twice about rap were all over De La. It was enough to make them denounce everything they’d established with Three Feet… on their next release, De La Soul Is Dead (Tommy Boy, 1991).

But Posdnous a.k.a. Wonder Why (Plug One), Trugoy the Dove a.k.a. Dr. Ama (Plug Two), and P. A. Mase a.k.a. Baby Huey (Plug Three) didn’t stagnate there. They’ve taken themselves and the whole genre with them (four records strong) to new heights with every release. Hip-hop is a genre that constantly rotates and changes. It’s nearly impossible to maintain any sort of popularity without selling your soul every time you come out. Longevity coupled with integrity in hip-hop is truly reserved for the absolute best.

I thought hard about the prospect of talking to De La Soul. Not only was I nervous and excited, but I felt like I already knew so much about them. De La Soul speaks from the soul. This fact cannot be denied. Their records reveal so much about what’s going on in their personal lives, there’s almost nothing to ask.

“We as people outside of the industry are alway trying to learn more,” Posdnous explains. “And whatever we take in, we try our best to convey it on wax. So beyond trying to find the best beats and the best music, we try to convey the best we can the evolution of the group. And not just trying to have the most positive message, because it could be in a negative light or us being upset or us not finding peace and tranquility… We try to balance it correctly because sometimes, regardless of how you feel, the best tracks may be focused on negative things. We try to have a balance of positive and negative on an album because there’s a balance to what a the human being is. All we try to do is just stay true to who we are as people. We can’t just focus on doing what we wanna do and let it be on wax. We separate ourselves as rappers and realize we are just people, and we just try to do the best we can as people. And that just naturally shows in our music. I’m just happy people have stuck behind us.”

Just two days after I talked to Pos, Biggie Smalls was gunned down in a drive-by shooting. Biggie was only twenty-four years old and is the second well-known emcee to be killed by gunfire in six months. Events like this are adored by all forms of media because the drama makes good copy, but in the process it gives rap music a bad name. The whole damn genre needs rehab. Just like the kids debating in the first scene of Spike’s movie Clockers, heads claim you’re not hard if you don’t kill people. Doing the things you talk about on record is considered by many “keeping it real,” but the grammatical first person in a rap song doesn’t necessarily mean the rapper.

“Even on an entertainment level,” Pos says addressing the issue, “back in the day, even when there was beef, it was more lyrically focused. Whereas now it’s on more of a physical level.” Theatrics used to play a huge role in lyrical storytelling, but nowadays one is expected to be that person — theatrics or not. This clash of lyrical-character versus man-on-the-street is like walls closing in. And those walls are already closed for Tupac Shakur and Chris Wallace.

“There’s a lot of groups trying to do positive things,” states Pos, “from Cool J to the Fugees trying to organize fund-raisers, Adam Yauch from the Beastie Boys doing the Tibetan Freedom Concert every year… There’s a host of others trying to do positive things.” The most important thing out here is creativity. Like KRS-One says, “You can be a pimp, hustler, or player, but make sure on stage you are a dope rhyme sayer.” Hip-hop is still a young culture and genre, so creativity is a must if it is to expand as an art form and even to simply maintain its existence. De La Soul is easily one of the major benchmarks of innovation in the short history of hip-hop, even though other groups have reached a larger audience by borrowing their style.

“I definitely feel we had some type of influence,” says Pos, “but sometimes I don’t even credit it to an influence, but just a reassurance of what we were already doing. I don’t like to think that a lot of groups were rapping one way and then when they heard us they started focusing on how we do things. There’s a lot of groups out there who had the same ideas, the same views, and the same energy, but we were just lucky enough to get on first so that helped a lot of record companies pay attention to the groups who were out there like that. When we were trying to put out unit together, there were a lot of rapers out before us that assured us that what we’re doing could be done.” Given, De La follows the orthodox traditions of hip-hop, but they blend so much of their own lives into the stew that it can’t help but come out innovative.

As irrelevant as it might seem to their true fans, De La’s record sales have dropped off since Three Feet High and Rising‘s surprise hit “Me, Myself, and I,” but that’s just not what De La Soul is about. “Obviously record sales have dropped because to us it’s not about trying to have this one radio hit that’s not really saying nothing at the end of the day — a year from now, or even a month from now and it’s not even remembered,” Pos says seriously. “We can make those easily. I’m not saying that ‘Me, Myself, and I’ is something that was necessarily forgotten, but we can make those for days. It was just never about making that. A lot of people do focus on that and at the end of the day for them, it’s about money. A lot of people want to get a lot out of hip-hop and don’t put anything into it. Forget it. This is a dying art form and I wast to put something back into it.”

Some of my old notebooks pages with De La lyrics and images.

Some of my old notebooks pages with De La lyrics and images.R.I.P., Dave.

Companion Compendia

Speaking of my scholarly pursuits, I have two books out on hip-hop and the future.

The central argument of my book Dead Precedents: How Hip-Hop Defines the Future (Repeater Books, 2019) is that the cultural practices of hip-hop are the blueprint to 21st century culture. Taking in the ground-breaking work of DJs and emcees, alongside science-fiction writers like Philip K. Dick and William Gibson, as well as graffiti and DIY culture, Dead Precedents is a counter-cultural history of the twenty-first century, showcasing hip-hop’s role in the creation of the world in which we now live.

My friends and I have continued this argument and its exploration in our collection, Boogie Down Predictions: Hip-Hop, Time, and Afrofuturism (Strange Attractor Press, 2022). Through essays by some of hip-hop’s most interesting thinkers, theorists, journalists, writers, emcees, and DJs, Boogie Down Predictions embarks on a quest to understand the connections between time, representation, and identity within hip-hop culture and what that means for the culture at large.

Do yourself a favor or two: get them both.

As always, thank you for reading, responding, and sharing,

-royc.

Thanks for reading Roy Christopher! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

February 1, 2023

What Was Wound

I often make a distinction between my favorite bands and the bands I think are the best. Unwound is one of the few bands for which that distinction means nothing: They are both one of my all-time favorite bands and one of the best to ever do it. Unwound have now been apart longer than they were together, but every time I listen to one of their records, I am reminded just how great they were.

Unwound at Off The Record in San Diego, 1997. Photo by Dave Young.

Unwound at Off The Record in San Diego, 1997. Photo by Dave Young.Having moved to the Pacific Northwest in the summer of 1993, I was trying to ease myself into the then-exploding local music scene. Their recent national attention had me already familiar with many bands and labels, but there were many more that only had fame and notoriety in their home region. I was digging deeper. That’s when I found Unwound.

Thanks for reading Roy Christopher! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

On a trip to Alaska that winter, I bought Fake Train (Kill Rock Stars, 1993). I still have vivid memories of falling asleep to it on headphones every night during that trip, immersed in basement darkness and new sounds. Some of my favorite songs still are from that initial exposure. I was hooked. I bought New Plastic Ideas (Kill Rock Stars, 1994) on vinyl at Mother Records in downtown Tacoma the day it came out.

In the book Unwound: 1991-2091 (Numero Group, 2023), David Wilcox writes that The Future of What (Kill Rock Stars, 1995) “would prove to be not so much a radical departure as the sound of a band growing restless, clinging to their past even as they lashed out against it…” Oddly, this is what all of their records sounded like to me, each at the time that it came out. As Justin Trosper (guitar/vocals) told me in 1998, “Well, sometimes you go into the studio with an idea, and you come out with something totally different… Every one of our records has its own purpose. I don’t think we’ve aimed too high, and I don’t think any of our records are perfect.”

Unwound started out with a different drummer. Brandt Sandeno had been their drummer when he, Justin, and Vern Rumsey (bass) were called Giant Henry. Brandt moved on about the same time the band was moving on to something larger, more definitive. They recorded one record as Unwound, but it wouldn’t be released until they’d become a sonic force beyond their 3-piece aspirations. Something special was emerging. The missing piece was Sara Lund.

Vern, Sara, and Justin: Unwound portraits by Zak Sally.

Vern, Sara, and Justin: Unwound portraits by Zak Sally.Everyone involved — even Brandt — will admit that Unwound wasn’t truly Unwound until Sara started playing drums. Like most great bands, the Justin/Vern/Sara line-up didn’t waver until the three were no longer a band.

Lost in the Capitol Theater crowd, Olympia, WA, 1994. Photo by Roy Christopher.

Lost in the Capitol Theater crowd, Olympia, WA, 1994. Photo by Roy Christopher.Numero Group’s commemorative box includes 10 CDs, a DVD, and a 256-page, hardback book. The DVD includes various live and candid clips of Unwound from throughout their 11-year lifespan, including footage from the one time I saw them play (pictured above): April 10, 1994 at the Capitol Theater in Olympia, Washington. Unwound was opening for Jawbreaker while the latter was touring their last good record, 24-Hour Revenge Therapy (Tupelo/Communion, 1994). Unwound weren’t even listed on the flyer.

They weren’t even on the flyer.

They weren’t even on the flyer.These home movies from all phases of Unwound’s existence illustrate not only their unsung greatness but also just how hard they worked at it. Unwound was one of the best bands to push sounds through speakers and commit those sounds to tape.

discontents zine

discontents zineThe above is an excerpt from the pilot issue of discontents. Some of my old zine-making friends (namely Patrick Barber and Craig Gates) and I recently decided to return to our roots and make a new zine. It’s available from Impeller Press.

We asked a bunch of our friends to contribute. See the Table of (dis)Contents below. Maybe you recognize a few.

Cover art by Tae Won Yu. Printed by Patrick Barber.

Cover art by Tae Won Yu. Printed by Patrick Barber.Here is the Table of Contents:

Features:

Ceremony by Roy Christopher

STILL: A Tribute to Hsi-Chang Lin by Roy Christopher

Secret Bike-Riding Club by Cynthia Connolly

Chipping Shins by Greg Pratt

Drawing Lines by Andy Jenkins

Michael Cooper by Spike Jonze

James Ward Byrkit Interview by Roy Christopher

Two Poems by Peter Relic

Columns:

Preface: This is the pilot by Roy Christopher

UNSUNG: Unwound by Roy Christopher (excerpted above)

BILF: Charles Yu’s Interior Chinatown by Roy Christopher

Music Ruined My Life by Timothy Baker

1Q with Fatboi Sharif

Exit Interview: Marnie Ellen Hertzler

Get yours from Impeller Press before they’re all gone!

As always, thanks for reading, responding, and sharing the love.

Hope you’re well,

-royc.

Thanks for reading Roy Christopher! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

January 24, 2023

Boombox Apocalypse

The turntable is easily the most iconic cultural artifact associated with hip-hop culture, but the advent and adoption of the boombox had as much to do with its spread and tenacity. Before raps were on the radio, they were on the tapes. Think of the turntable and the microphone as the senders and the boombox and the cassette as the receivers: without recording and playback, hip-hop wouldn’t have lasted long. The already choked socioeconomic conditions from which it sprang could’ve buried it like so much tape hiss.

Radio Raheem’s Promax Super Jumbo boombox from Do the Right Thing (1989).

Radio Raheem’s Promax Super Jumbo boombox from Do the Right Thing (1989).Never put me in your box if your shit eats tapes. — Nas, “N.Y. State of Mind“

When Hip-hop migrated to the middle spaces between the coasts and big cities, it did so via cassettes. Long before everything went digital, mixtapes—those floppy discs of the boombox and car stereo—facilitated the spread of underground music. The first time I heard hip-hop, it was on such a tape. Hiss and pop were as much a part of the experience of those mixes as the scratching and rapping. We didn’t even know what to call it, but we stayed up late to listen. We copied and traded those tapes until they were barely listenable. As soon as I figured out how, I started making my own. We watched hip-hop go from those scratchy mixtapes to compact discs to shiny-suit videos on MTV, from Fab 5 Freddy to Public Enemy to P. Diddy, from Run-DMC to N.W.A. to Notorious B.I.G. Others lost interest along the way. I never did.

Mixtapes were such an integral part of its spread that I felt weird when I first bought a “Rap” CD (The same could be said for any other underground movement of the time: punk, hardcore, metal, etc.). When it was shared and heard, it was done so on scratchy cassettes. Sometimes these tapes were played in cars, home stereo systems, and Walkmans, but they were more importantly played in giant boomboxes, each occasion allowing producers taking advantage of different aspects of sample-based recording.

Unlike today’s personal media devices, the presence of the boombox was also a public presence. Just as we gather around some screens and stare at others alone, we once gathered around the speakers of boomboxes. The reception of hip-hop is as important as its inception, and that the boombox played a major role in its early days. It was the site and the sight of the sound in the streets. When I got my first Walkman and stopped lugging around my Sony boombox, it was a blessing to my back and the sanity of those around me (most notably my parents), but the boombox remains a part of the iconography of hip-hop.

From mixtapes to mash-ups, hip-hop is the blueprint to 21st century culture (This argument is the crux of my book Dead Precedents: How Hip-Hop Defines the Future). What used to be done via mixers, faders, and turntables is now done via software, iPhones, and the internet. In the hands of the indolent and uncreative, sampling is dull at best and disturbing at worst — but so is guitar-playing. As Laurie Anderson says, “very dangerous art can be made with a pencil.” You don’t need me to tell you that it’s not the tools that matter, it’s what you do with them.

A lot of people all over the world heard those early tapes and were impacted as well. Having spread from New York City to parts unknown, hip-hop became a global phenomenon. Every school has aspiring emcees, rapping to beats banged out on lunchroom tables. Every city has kids rhyming on the corner, trying to outdo each other with adept attacks and clever comebacks. From the boombox to Planet Rock, the cipher circles the planet.

Companion Compendia

As I mentioned above, the central argument of my book Dead Precedents: How Hip-Hop Defines the Future (Repeater Books, 2019) is that the cultural practices of hip-hop are the blueprint to 21st century culture. Taking in the ground-breaking work of DJs and emcees, alongside science-fiction writers like Philip K. Dick and William Gibson, as well as graffiti and DIY culture, Dead Precedents is a counter-cultural history of the twenty-first century, showcasing hip-hop’s role in the creation of the world in which we now live.

My friends and I have continued this argument and its exploration in our collection, Boogie Down Predictions: Hip-Hop, Time, and Afrofuturism (Strange Attractor Press, 2022). Through essays by some of hip-hop’s most interesting thinkers, theorists, journalists, writers, emcees, and DJs, Boogie Down Predictions embarks on a quest to understand the connections between time, representation, and identity within hip-hop culture and what that means for the culture at large.

Do yourself a favor or two: get them both.

I stole the title of this post from the Hangar 18 song. Shout out to Tim and Ian.

Thank you for reading, responding, and sharing,

-royc.

January 19, 2023

Answering Machines

“Welcome to the world of Pinecone Computers,” Miles Harding (played by Lenny Von Dohlen) reads from a computer manual in Electric Dreams (1984). “This model will learn with you, so type your name and press Enter key to begin.”1 Since the big-screen tales of the 1980s PC-era, the idea of machines merging with humans has been a tenacious trope in popular culture. In Tron (1982) Kevin Flynn (played by Jeff Bridges) was sucked through a laser into the digital realm. Wired to the testosterone, the hormone-driven juvenile geniuses of Weird Science (1985) set to work making the woman of their dreams. WarGames (1983) famously pit suburban whiz-kids against a machine hell-bent on launching global thermonuclear war. In Electric Dreams (1984), which is admittedly as much montage as it is movie, Miles (von Dohlen, who would go on to play the agoraphobic recluse Harold Smith in Twin Peaks, who kept obsessive journals of the towns-folks’ innermost thoughts and dreams) attempts to navigate a bizarre love triangle between him, his comely neighbor, and his new computer.

Theodore Twombly meets Samantha in Spike Jonze’s Her.

Theodore Twombly meets Samantha in Spike Jonze’s Her.From the jealous machine to falling in love with the machine, the theme remains pervasive. As artificial-intelligence researcher Ray Kurzweil writes of Spike Jonze’s 2013 movie Her, “Jonze introduces another idea that I have written about […] namely, AIs creating an avatar of a deceased person based on their writings, other artifacts and people’s memories of that person.”2 In the near future of Her, Theodore Twombly (played by Joaquin Phoenix) writes letters for a living, letters between fathers and daughters, long-distance lovers, husbands, wives, and others. In doing so, he is especially susceptible to the power of narrative himself since his job involves the constant creation of believable, vicarious stories. His ability to immerse himself in the stories of others makes it that much easier for him to get lost in the love of his operating system, Samantha (voiced by Scarlett Johansson), as she constructs narratives to create her personality, and thereby, their relationship.

Thanks for reading Roy Christopher! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Cognitive scientist Douglas Hofstadter calls our imbuing machines with more intelligence than they have—even when we know better—“The ELIZA Effect,” after Joseph Weizenbaum’s text-based psychoanalytic computer program, ELIZA. Hofstadter writes, “the most superficial of syntactic tricks convinced some people who interacted with ELIZA that the program actually understood everything that they were saying, sympathized with them, even empathized with them.”3 ELIZA was written at MIT by Weizenbaum in the mid-1960s, but its effects linger on. “Like a tenacious virus that constantly mutates,” Hofstadter continues, “the Eliza effect seems to crop up over and over again in AI in ever-fresh disguises, and in subtler and subtler forms.”4 In the first chapter of Sherry Turkle’s Alone Together, she extends the idea to our amenability to new technologies, including artificial intelligence, embodied or otherwise: “and true to the ELIZA effect, this is not so much because the robots are ready but because we are.”5

Virtual Girlfriend: “Knowledge Acquiring and Response Intelligence,” Kari 5.0.

Virtual Girlfriend: “Knowledge Acquiring and Response Intelligence,” Kari 5.0.More germane to Jonze’s Her is a program called KARI, which stands for “Knowledge Acquiring and Response Intelligence.” According to Dominic Pettman’s first and only conversation with KARI, as described in his book, Look at the Bunny, there’s a long way to go before any of us are falling in love with our computers. After interacting with a similar bot online, Jonze agrees. “For the first, maybe, twenty seconds of it,” he says, “I had this real buzz—I’d say ‘Hey, hello,’ and it would say ‘Hey, how are you?,’ and it was like whoa… this is trippy. After twenty seconds, it quickly fell apart and you realized how it actually works, and it wasn't that impressive. But it was still, for twenty seconds, really exciting. The more people that talked to it, the smarter it got.” The author James Gleick comes to the conceit from the other side, writing, “I’d say Her is a movie about (the education of) an interesting woman who falls in love with a man who, though sweet, is mired in biology.” At one point in the movie, Samantha imagines the same fate for herself: “I could feel the weight of my body, and I was even fantasizing that I had an itch on my back—(she laughs) and I imagined that you scratched it for me—this is so embarrassing.” The dual feelings of being duped by technology and mired in biology sit on the cusp of the corporeal conundrum of what it means to be human, to have not only consciousness but also to have a body, as well as what having a body means.6

Mechanical MatrimonyWhere some see the whole mess of bodies and machines as one, big system. Others picture the airwaves themselves as extensions. “Telepresence,” as envisioned by Pat Gunkel, Marvin Minsky, and others, sets out to achieve a sense of being there, transferring an embodied experience across space via telephone lines, satellites, and sensory feedback loops.7 It sounds quaint in world where working from home is normal for many and at least an option for others, but Marshall McLuhan was writing about it in the 1960s, and Minsky and his lot were working on it in the 1970s.

Still others imagine a much more deliberate merging of the biological and the mechanical, postulating an uploading of human consciousness into the machines themselves. Known in robotic and artificial intelligence circles as “The Moravec Transfer,” its namesake, the roboticist Hans Moravec, describes a human brain being uploaded, neuron by neuron, until it exists unperturbed inside a machine.8 But Moravec wasn’t the first to imagine such a transition. The cyberpunk novelist and mathematician Rudy Rucker outlined the process in his 1982 novel, Software. “It took me nearly a year to really figure out the idea,” he writes, “simple as it now seems. I was studying the philosophy of computation at the University of Heidelberg, reading and pondering the essays of Alan Turing and Kurt Gödel.”9 Turing was an early inventor of computing systems and AI, best known for the Turing test, whereby an AI is considered to be truly thinking like a human if it can fool a human into thinking so. Gödel was a logician and mathematician, best known for his incompleteness theorem. Both were heavily influential on the core concepts of computing and artificial intelligence. “It’s some serious shit,” Rucker writes of the process. “But I chose to present it in cyberpunk format. So, no po-faced serious, analytic-type, high literary mandarins are ever gonna take my work seriously.”10 In Rucker’s story, a robot saves its creator by uploading his consciousness into a robot.

NASA’s own Robert Jastrow wrote in 1984 that uploading our minds into machines is the be-all of evolution and would make us immortal. He wrote,

at last the human brain, ensconced in a computer, has been liberated from the weakness of the mortal flesh. […] The machine is its body; it is the machine’s mind. […] It seems to me that this must be the mature form of intelligent life in the Universe. Housed in indestructible lattices of silicon, and no longer constrained in the span of its years by the life and death cycle of a biological organism, such a kind of life could live forever.11

In the 2014 movie Transcendence, Dr. Will Caster (played by Johnny Depp) and his wife Evelyn (played by Rebecca Hall) do just that. Caster is terminally ill and on the verge of offloading his mortal shell. Once his mind is uploaded into a quantum computer connected to the internet, Caster becomes something less than himself and something more simultaneously. It’s the chronic consciousness question: What is it about you that makes you you? Is it still there once all of your bits are transferred into a new vessel? The Casters’ love was strong enough for them to try and find out.

Escape Philosophy

Escape PhilosophyThe essay above is an excerpt from Chapter 3, “MACHINE: Mechanical Reproduction,” of my book Escape Philosophy: Journeys Beyond the Human Body, which is available as an open-access .pdf and beautiful paperback from punctum books. It’s really quite good, but don’t take my word for it…

“An interesting read indeed!” — Aaron Weaver, Wolves in the Throne Room

“An interesting read indeed!” — Aaron Weaver, Wolves in the Throne RoomAs always, thank you for reading,

-royc.

1Steve Barron, dir., Electric Dreams, written by Rusty Lemorande (Los Angeles: Virgin Films, 1984).

2Ray Kurzweil, “A Review of ‘Her’ by Ray Kurzweil,” Kurzweil.com, February 10, 2014.

3Douglas Hofstadter, Fluid Concepts and Creative Analogies: Computer Models of the Fundamental Mechanisms of Thought (New York: Basic Books, 1995), 158.

4Ibid.

5Sherry Turkle, Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other (New York: Basic Books, 2011), 24–25.

6As Hayles notes, “when information loses its body, equating humans and computers is especially easy.” N. Katherine Hayles, How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999), 2.

7See Marvin Minsky, “Telepresence,” OMNI Magazine, June 1980, 45–52.

8See Hans Moravec, Mind Children: The Future of Robot and Human Intelligence (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1988). For another early example, see G. Harry Stine, “The Bionic Brain,” OMNI Magazine, July 1979, 84–86, 121–22.

9Rudy Rucker, “Outer Banks & New York #1,” Rudy’s Blog, August 2, 2015.

10Ibid.

11Robert Jastrow, The Enchanted Loom: Mind in the Universe (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1984), 166–67.

January 9, 2023

Irony is for Suckers

"Irony used to feel like a defense against getting played," writes the novelist Hari Kunzru, "a way for a writer to ward off received ideas and lazy thinking." Broadly speaking, irony is the rhetorical strategy of saying one thing yet meaning another, usually the opposite. It also might be the most abused trope of our time. It's beyond substance over style. It's the absurd over the authentic. "It also made us feel nihilistic and defeated," Kunzru continues. "More recently we've seen how it can be a screen for reactionary politics." In the preface to his 1999 book, For Common Things, Jedidiah Purdy frames the overbearing irony of our era as a defense mechanism: "It is a fear of betrayal, disappointment, and humiliation, and a suspicion that believing, hoping, or caring too much will open us up to these." It's an escape route, an exit strategy, a way off the hook in any situation, it's become the dominant mode of pop culture, and we're all tired of it.

In his book, The Comedian as Confidence Man, Will Kaufman explains the feeling, coining what he calls irony fatigue, the exhaustion of ironic distance as the promise of play collides with the pursuit of truth. He discusses the comedian Bill Hicks having to edit lines from his twelfth, unaired appearance on Late Night with David Letterman. Hicks maintained his "Warrior for Truth" persona, claiming all the while that they were "just jokes." He didn’t intend to offend because he was just kidding. Having it both ways is perhaps impossible for a figure under public and media scrutiny, but what about your classmates, colleagues, and friends? What about the coffee shop denizen? Are they for real, or are they joking? Why is everyone so veiled in irony? Princeton Professor Christy Wampole writes,

Ironic living is a first-world problem. For the relatively well educated and financially secure, irony functions as a kind of credit card you never have to pay back. In other words, the hipster can frivolously invest in sham social capital without ever paying back one sincere dime. He doesn't own anything he possesses.

Three major cultural epochs came and went in the meantime: cool became uncool, the nerds had their revenge, and stark sincerity was pushed to its breaking point. One was already faltering when the 21st century arrived. Everything that used to be cool is now remade, rebooted, or recycled. Resorting to irony is the only response that quells the cognitive dissonance of dealing with such a contradictory world. Between the death of cool and the ironic now, the geeks rose to rule all and emo culture came to the fore, the latter allowing young men to reveal their emotions. We all know the story of the geeks, theirs was a rise to riches, an underdog having its day, as Purdy put it in 1999, "They are not so much ushering in the next millennium as riding out the last." The emo kids never enjoyed such empowerment.

In America's post-9/11 cultural climate of mourning, confusion, anger, and uncertainty, the emo subculture gained momentum as a way for young people to express and deal with their anger and uncertainty. The music and the open wounds allowed young people mourn in public. In his 2003 book Nothing Feels Good, Andy Greenwald frames emo culture as a teen phenomenon, a culture of kids who haven't "thought the deep thoughts yet—they're too caught up in their own private drama and they’ve found a music that privileges that very same drama—that forces no difficult questions, just bemoans the lack of answers." Post-9/11 America might have been about forcing the difficult questions, but it was just as much about bemoaning the lack of answers, and emo made either one okay. Coming of age already leaves teenagers feeling uprooted and untethered, with no home and no sense of belonging. The feeling was only exacerbated by the events of September 11th. Now, not only were their bodies and relationships changing in unprecedented ways, but the world was doing the same thing. As Robert Pogue Harrison puts it, "Wherever the real imposes itself, it tends to dissipate the fogs of irony." This lack of roots provides the backdrop for the mass emergence of emo culture. Emo allowed dudes to be as sappy and sincere as they wanted to be. "If we stay with the sense of loss," Judith Butler writes in her book Precarious Life, "are we left feeling only passive and powerless, as some might fear?" The feeling of being only passive and powerless is at the core of emo culture. She continues,

Or are we returned to a sense of human vulnerability, to our collective responsibility for the physical lives of one another? Could the experience of a dislocation of First World safety not condition the insight into the radically inequitable ways that corporeal vulnerability is distributed globally? To foreclose that vulnerability, to banish it, to make ourselves secure at the expense of every other human consideration is to eradicate one of the most important resources from which we must take our bearings and find our way.

Where emo culture folds under the weight of affect and uncertainty, Butler urges us to follow it outward. Parks & Recreation creator Mike Schur tells Mike Sacks, "sincerity is the opposite of 'cool' or 'hip' or 'ironic'." All of these tribulations may seem trivial, but, as Jaron Lanier writes, "pop culture is important. It drags us all along with it; it is our shared fate. We can't simply remain aloof." If our pop culture is just recycling plastic pieces of the past, where it is dragging us?

Simon Reynolds draws a parallel between nostalgic record collecting and finance, "a hipster stock market based around trading in pasts, not futures," in which a crash is inevitable: "The world economy was brought down by derivatives and bad debt; music has been depleted of meaning through derivatives and indebtedness." After all what is emo if not punk-rock chocolate dunked in goth peanut butter? For better or more likely for worse, what emerged after emo culture was the cult of irony. In the ennui of the everyday, we no longer strive to be sincere or cool, but coldly ironic. Nostalgia for simpler times but times not taken to heart is our default stance. Filters on digital photos that make them look old represent not only longing but the undermining of that longing. It's irony fatigue filtered in sepia and framed like a Polaroid.

Wampole cites generational differences, the proliferation of psychotropic drugs, and technological connectivity as reasons for widespread irony. To live in the image of irony is to avoid risk. It means not ever having to mean. She writes, "Moving away from the ironic involves saying what you mean, meaning what you say and considering seriousness and forthrightness as expressive possibilities, despite the inherent risks." You don't even have to be cool, geeky or emo, but you can if you want to.

As I mentioned last time, I have a collection of illustrations and logo designs up for the month of January at Reset Mercantile in Dothan, Alabama. The video clip above is from the First Friday Art Crawl on January 6, 2023. It was a good time.

Thanks to Justin April at Reset for hosting, Ryan Mills at Big as Life Media for the video, Mike Nagy, and everyone else for coming through.

The pieces are up all month, so check them out if you're in the area.

Thanks for reading,

-royc.

January 3, 2023

A Prayer for a New Year

More stretch, less tense.

More field, less fence.

More bliss, less worry.

More thank you, less sorry.

More nice, less mean.

More page, less screen.

More reading, less clicking.

More healing, less picking.

More writing, less typing.

More liking, less hyping.

More honey, less hive.

More pedal, less drive.

More wind, less window.

More in action, less in-tow.

More yess, less maybes.

More orgasms, less babies.

More hair, less cuts.

More ands, less buts.

More map, less menu.

More home, less venue.

More art, less work.

More heart, less hurt.

More meaning, less words.

More humans, less herds.

More verbs, less nouns.

More funny, less clowns.

More dessert, less diet.

More noise, less quiet.

More courage, less fear.

More day, less year.

More next, less last.

More now, less past.

[Spike Jonze Smith grind, charcoal pencil sketch, 12/24/2022]

Art Show AlertI'll have some of my drawings and logo designs up on the wall again this month at Reset Mercantile in Dothan, Alabama. This is my first solo art show, and I couldn't be more stoked on the venue. Many thanks to Justin April for hooking this up.