Roy Christopher's Blog, page 6

March 17, 2024

Adversaries and Anniversaries

I was talking with my brother-in-law a few years ago about electric cars. He converts internal-combustion vehicles to electric, and he was explaining how gasoline is an energy-rich fuel source compared to batteries. That is, it takes far less gas to push a vessel over a distance than it does electricity from a battery.

Writing is an effort-intense way to express oneself. It takes a long time to write a book and then to get back whatever you’re going to get back. Some of it is just the way the medium is consumed. If you make a record or a movie, it only takes an hour or two for someone to experience it. A book takes much longer.

Five years later, heads still ain’t ready…

Five years later, heads still ain’t ready…Writing is difficult at every turn: it’s difficult to do, it’s difficult to get feedback, it’s difficult to get published, it’s difficult to sell, and it’s difficult to get read. This week marks the five-year anniversary of the release of my book Dead Precedents: How Hip-Hop Defines the Future from Repeater Books! Now, I’ve written and edited a few more books since, but even if it were my only book, I’d be proud of the final product.

The central argument of Dead Precedents is that the cultural practices of hip-hop are the cultural practices of the 21st century. In what Walter Benjamin would call correspondences, I use evidence from cyberpunk and Afrofuturism to make the book’s many claims—everyone from Philip K. Dick, William Gibson, and Rudy Rucker to Public Enemy, Shabazz Palaces, and Rammellzee, among others.

Dead Precedents with the hands from Run the Jewels’

RTJ3

. [photo by Tim Saccenti]

Dead Precedents with the hands from Run the Jewels’

RTJ3

. [photo by Tim Saccenti]Jeff Chang, author of Can’t Stop, Won’t Stop and co-editor of Freedom Moves, says, “Roy Christopher’s dedication to the future is bracing. Dead Precedents is sharp and accelerated.” And Samuel R. Delany calls it “a book with so much energy and passion in it… a lively screed.”

If you don’t know, now you know.

And if you still don’t have a copy, get up on it!

Another Anniversary

Another AnniversaryI was never an angry or a sad drunk, but I took a short break from the drink in January 2017. After a couple of out-of-pocket nights in March, I decided to try it again.

That was seven years ago, and I’ve found nothing bad about not imbibing. As Ian MacKaye once said, “If you want to rebel against society, don’t dull the blade.”

Amen.

Also, if you’d like a copy of Dead Precedents (or any of my books for that matter) and can’t afford one or whatever, let me know. We’ll work something out.

If you’ve read it, please consider posting a review. They really do help.

Thank you for reading,

-royc.

March 6, 2024

A Story, A Prophecy: DUNE Redux

I’ve seen the second part of Denis Villeneuve’s Dune adaptation a few times now, but I’m having a hard time putting it all into words.

Paul and Chani in Dune, Part Two.

Paul and Chani in Dune, Part Two.Here are a few:

Shai-Hulud will decideWho will and will not rideThe desert is hard on people Sand and wind and heat and prideBene Gesserit prophecy in the SouthWords that will bring them outTo the ears of the believersFrom the Reverend Mother’s mouthThe Voice from the Outer WorldCrysknife handle, fingers curledPaul Muad’Dib Usul AtreidesThe Fremen banner unfurledWhat follows is a primer on most of the previous adaptations of Dune, including versions by David Lynch (another bridge from 1984 to 2024) and Alejandro Jodorowsky, as well as Part One of Villeneuve’s version.

No spoilers for the new one though, so read on!

The Mythology and Missteps of DUNE“A beginning is the time for taking the most delicate care that the balances are correct,” opens Frank Herbert’s 1965 science-fiction epic Dune. Herbert says of the novel’s beginnings, “It began with a concept: to do a long novel about the messianic convulsions which periodically inflict themselves on human societies. I had this idea that superheroes were disastrous for humans.” The concept and its subsequent story, which took Herbert eight years to execute, won the Hugo Award, the first Nebula Award for Best Novel, and the minds of millions. In his 2001 book, The Greatest Sci-Fi Movies Never Made, chronicler of cinematic science-fiction follies David Hughes writes, “While literary fads have come and gone, Herbert’s legacy endures, placing him as the Tolkien of his genre and architect of the greatest science fiction saga ever written.” Kyle MacLachlan, who played Paul Atreides in David Lynch's film adaptation, told OMNI Magazine in 1984, “This kind of story will survive forever.”

Writers of all kinds are motivated by the search and pursuit of story. A newspaper reporter from the mid-to-late-1950s until 1969, Herbert employed his newspaper research methods to the anti-superhero idea. He gathered notes on scenes and characters and spent years researching the origins of religions and mythologies. Joseph Campbell, the mythologist with his finger closest to the pulse of the Universe, wrote in The Inner Reaches of Outer Space: Metaphor as Myth and as Religion (1986), “The life of mythology derives from the vitality of its symbols as metaphors delivering, not simply the idea, but a sense of actual participation in such a realization of transcendence, infinity, and abundance… Indeed, the first and most essential service of a mythology is this one, of opening the mind and heart to the utter wonder of all being.” Dune is undeniably infused with the underlying assumptions of a powerful mythology, as are its film adaptations.

Jodorowsky’s Dune look-book.

Jodorowsky’s Dune look-book.After labored but failed attempts by Alejandro Jodorowsky, Haskell Wexler, and Ridley Scott (the latter of whom offered the writing job to no less than Harlan Ellison) to adapt Dune to film, David Lynch signed on to do it in 1981. With The Elephant Man (1980) co-writers Eric Bergren and Christopher De Vore, Lynch started over from page one, ditching previous scripts by Jodorowsky, Rudolph Wurlitzer, and Frank Herbert himself, as well as conceptual art by H.R. Giger (who had designed the many elements of planet Giedi Prime, home of House Harkonnen), Jean Giraud, Dan O’Bannon, and Chris Foss. Originally 200 pages long, Lynch’s script went through five revisions before it was given the green light, which took another full year of rewriting. “There’s a lot of the book that’s isn’t in the film,” Lynch said at the time. “When people read the book, they remember certain things, and those things are definitely in the film. It’s tight, but it’s there.”

Lynch’s Dune is of the brand of science fiction during which one has to suspend not only disbelief in the conceits of the story but also disbelief that you’re still watching the movie. I’m thinking here of enjoyable but cheesy movies like Logan’s Run (1976), Tron (1984), The Last Starfighter (1984), and many moments of the original Star Wars trilogy (1977, 1980, 1983), the latter of which owes a great debt to Herbert's Dune. I finally got to see Lynch's version on the big screen in 2013 at Logan Theater in Chicago for the 30th anniversary, and again recently in Jacksonville for the 40th. As many times as I’ve watched it over the years, it was still a treat to see it the size Lynch originally intended.

Dune is not necessarily a blight on Lynch’s otherwise stellar body of work, but many, including Lynch, think that it is. “A lot of people have tried to film Dune,” Herbert himself once said. “They all failed.” The art and design for Jodorowsky's attempt, by H.R. Giger, Moebius, Chris Foss, Dan O'Bannon, and others, was eventually parted out to such projects as Star Wars (1977), Alien (1979), and Blade Runner (1982). When describing the experience in the book Lynch on Lynch (2005), Lynch uses sentences like, “I got into a bad thing there,” “I really went pretty insane on that picture,” “Dune took me off at the knees. Maybe a little higher,” and, “It was a sad place to be.” Lynch’s experience with Dune stands with Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, and Terry Gilliam’s The Man Who Killed Don Quixote (2018) as chaotic case studies in the pitfalls of novel-adapting and movie-making gone difficult-to-wrong. As Jodorowsky says, “You want to make the most fantastic art of movie? Try. If you fail, is not important. We need to try.”

Denis Villeneuve and Rebecca Ferguson on the set of Dune, Part One. Photo by Chiabella James.

Denis Villeneuve and Rebecca Ferguson on the set of Dune, Part One. Photo by Chiabella James.I was as skeptical as anyone would be when Denis Villeneuve’s adaptation was announced, even though I'm a big fan of Villeneuve's work and his aesthetic. Everything from the foreboding of Enemy (2013) and the family drama of Prisoners (2013) to the abject and arid borderlands of Sicario (2015), to the damp alienness of Arrival (2016) and Blade Runner 2049 (2017) all seem to prepare Villeneuve to tackle the historical weight of Dune. In an era when it's difficult to imagine any single story having any kind of lasting impact, reviving a story from over 50 years ago seems as risky as trying to come up with something new. Sarah Welch-Larson writes at Bright Wall/Dark Room,

The movie is weighed down by the reputation of the novel that inspired it, by the expectations of everyone who’s loved the story, by the baggage it carries with it. The plot of the original novel is ponderous enough, concerned as it is with ecology and politics and conspiracies to breed a super-powered Messiah. Add 56 years of near-religious reverence within the science fiction community, plus a mountain of fair criticism and a history of disappointing screen adaptations, and any new version of Dune would be justifiably pinned under the weight of its own expectations.

One word that seems inextricable from Villeneuve’s Dune is scale. The scale of the planets, the ships, the interstellar travel, the desert of Arrakis, the massive Shai-Hulud, and even Baron Vladimir Harkonnen are all colossal, the sheer size of the story and its history notwithstanding. It's an aspect of the story that the other adaptation attempts don’t quite capture. To be fair, Lynch’s original cut was rumored to be four hours long, and Jodorowsky had a 14-hour epic planned. The fact that this two-hour movie is only the first part of his version gives us first indication that Villeneuve being realistic but also taking the size of it seriously.

Rebecca Ferguson is Lady Jessica. Photo by Chiabella James.

Rebecca Ferguson is Lady Jessica. Photo by Chiabella James.I’ve now seen it in the theater five times, one of those in IMAX, and the attention to scale is appropriate. The movie is nothing if it isn't immense, as wide as any of Earth's deserts, as dark as any of its oceans. It looms over you like nothing else you've ever seen. In a cast that includes Timothée Chalamet, Jason Momoa, Javier Bardem, Josh Brolin, Oscar Isaac, Sharon Duncan-Brewster, Stellan Skarsgård, Dave Bautista, Stephen McKinley Henderson, and David Dastmalchian, it’s Rebecca Ferguson’s performance as Lady Jessica that stands out. As powerful and dangerous as she is, she's also the emotional center of the movie. Chalamet’s Paul Atreides might be the one you follow, but Ferguson is the one you feel. She’s mesmerizing in the role.

In light of the new movies, Herbert’s novel continues to spread the story. The designer Alex Trochut did the cover designs for Penguin’s Galaxy series of hardbacks, including well-worn volumes like William Gibson's Neuromancer, Arthur C. Clarke’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness, and Herbert’s Dune. Trochut’s Dune logo is perfect. Not only do all of the letters work as a 90-degree tilted version of the same U-shaped form, but the logo itself works when spun to any side. Weirdly, this version appears on the back of the book. Why you would display the word “dune” any other way after seeing this is beyond me.

Beginnings are indeed delicate times, and Frank Herbert knew not what he had started. “I didn’t set out to write a classic or a bestseller,” he said. “In fact, once it was published, I wasn't really aware of what was going on with the book, to be quite candid. I have this newspaperman’s attitude about yesterday’s news, you know? ‘I’ve done that one, now let me do something else.’” He went on to write five sequels, and his son Brian and Kevin J. Anderson have written many other novels set in the Dune universe. Even for its author, the mythology of Dune proved too attractive to escape.

Dune, Part Two is in theaters now. See it as big and loud as you can.

Thank you for your continued interest and support,

-royc.

February 25, 2024

The Long Bright Dark

During the last episode of season four of True Detective, some cheered and others groaned when Raymond Clark said “time is a flat circle,” repeating Reggie Ledoux and Rustin Cohle’s line from season one. OG creator and showrunner Nic Pizzolato himself did not appreciate the homage to the original. Allusions as such can go either way.

At their best, allusions add layers of meaning to our stories, connecting them to the larger context of a series, genre, or literature at large. At worst, they’re lazy storytelling or fumbling fan service. It feels good to recognize an obscure allusion and feel like a participant in the story. It feels cheap to recognize one and feel manipulated by the writer. They are contrivances after all: legacy characters, echoed dialog, recurring locations or props—all of these can work either way, to cohere or alienate, to enrich the meaning or pull you right out of the story.

[WARNING: Spoilers abound below for all seasons of HBO’s True Detective .]

The spiral as seen in season four of True Detective: a motif smuggled out of the mythology of season one.

The spiral as seen in season four of True Detective: a motif smuggled out of the mythology of season one.Our experience with a story is always informed by our past experience—lived or mediated—but when that experience is directly referenced with an allusion, we feel closer to the story. Allusions are where we share notes with other fans, and they form associative paths, connecting them to other artifacts. So, if you recognized Ledoux or Cohle’s words coming out of Clark’s mouth, or if you recognized all of them as Friedrich Nietzsche’s eternal recurrence, you probably felt a closer tie to the story. As he wrote in The Gay Science (1882), “Do you want this again and innumerable times again?” For Nietzsche, this is all there was, and to embrace this recurrence was to embrace human life just as it is: the same thing over and over.

Rustin Cohle and Marty Hart in season three.

Rustin Cohle and Marty Hart in season three.Moreover, in season four we got the ghost of Rust Cohle’s father, Travis Cohle, a connection to the vast empire of the Tuttle family, and the goofy gag of recurring spirals. Season three had its passing connections to season one as well, as seen in the newspaper article in the image above. Given the pervasive references to it, season one may have been the show’s peak, but my favorite is still the beleaguered second season, the only one so far that stands free of allusions to the other seasons of the anthology. Perhaps it is the most hated season of the series because of its refusal to connect to and coexist with the others, yet—riding the word-of-mouth wave from season one—it’s also the most watched.

It should be noted that in addition to its lack of allusions to season one and any semblance of interiority, season two also lacks any sense of the spiritual. There is only the world you see and feel in front of you, no inner world, no adjacent beyond, no Carcosa. As Raymond Velcoro says grimly, “My strong suspicion is we get the world we deserve.”

Bezzerides and Velcoro share a moment of quiet contemplation.

Bezzerides and Velcoro share a moment of quiet contemplation.Season two continues the gloom of the first season, moving it from the swamps of Louisiana to the sprawl of Los Angeles. Like its suburban setting, season two stretches out in good and bad ways, leaving us by turns enlightened and lost. Though, as Ian Bogost points out, where Cohle got lost in his own head, the characters in season two—Ani Bezzerides, Paul Woodrugh, Frank Semyon, and Velcoro—get lost in their world. The physician and psychoanalyst Dr. John C. Lilly distinguished between what he called insanity and outsanity. Insanity is “your life inside yourself”; outsanity is the chaos of the world, the cruelty of other people. Sometimes we get lost in our heads. Sometimes we get lost in the world.

Rust Cohle in his storage shed in season one.

Rust Cohle in his storage shed in season one.To be fair, season one isn’t without its references to existing texts. Much of the material in Cohle’s monologues is straight out of Thomas Ligotti’s The Conspiracy Against the Human Race (Hippocampus Press, 2010), where he quotes the Norwegian philosopher Peter Wessel Zapffe (even using the word “thresher” to describe the pain of human existence), and the dark-hearted philosophy of Nietzsche, of course. The writings of Ambrose Bierce (“An Inhabitant of Carcosa”), H.P. Lovecraft (Cthulhu Mythos), and Robert W. Chambers (“The Yellow King”) also make appearances. Daniel Fitzpatrick writes in his essay in the book True Detection (Schism, 2014), “Through these references, engaged viewers are offered a means to unlock the show’s secrets, granting a more active involvement, and while these references are often essential and enrich our experience of the show, in its weaker moments they can make it seem like a grab-bag of half thought-through allusions.”

“One of the things that I loved most about that first season of True Detective was the cosmic horror angle of it,” says season four writer, director, and showrunner Issa López. “It had a Carcosa, and it had a Yellow King, which are references to the Cthulhu Mythos with Lovecraft and the idea of ancient gods that live beyond human perception.” The hints of something beyond this world, “the war going on behind things,” as Reverend Billy Lee Tuttle put it, pulled us all in. “That sense of something sinister playing behind the scenes, and watching from the shadows,” she continues, “is something that I very much loved.”

In his book on suicide, The Savage God (1970), Al Álvarez writes, “For the great rationalists, a sense of absurdity—the absurdity of superstition, self-importance, and unreason—was as natural and illuminating as sunlight.” By the end of season one, Rustin Cohle seems to embrace the eternal recurrence of his life, the spiral of light and dark—including his own daughter’s death. At the end of Night Country, Evangeline Navarro seems to do the same, walking blindly into extinction, one last midnight, a lone sister, fragile and numinous, opting out of a raw deal, lost both in her head and in the world.

Thank you for reading Roy Christopher. This post is public so feel free to share it.

Further Reading:David Benatar, Better Never to Have Been: The Harm of Coming Into Existence, Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Ambrose Bierce, Ghost and Horror Stories of Ambrose Bierce, New York: Dover, 1964.

Ray Brassier, Nihil Unbound: Enlightenment and Extinction, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.

Robert W. Chambers, The King in Yellow, Knoxville, TN: Wordsworth Editions, 2010.

Edia Connole, Paul J. Ennis, & Nicola Masciandaro (eds.), True Detection, Schism, 2014.

Jacob Graham & Tom Sparrow (eds.), True Detective and Philosophy: A Deeper Kind of Darkness, Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 2018.

Thomas Ligotti, The Conspiracy Against the Human Race, New York: Hippocampus Press, 2010.

Friedrich Nietzsche, The Gay Science, New York: Dover, 1882.

Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spake Zarathustra: A Book for All and None, New York: Macmillan. 1896.

Nic Pizzolatto, Between Here and the Yellow Sea, Ann Arbor, MI: Dzanc Books, 2015.

Eugene Thacker, In the Dust of This Planet: Horror of Philosophy, Vol. 1, London: Zer0 Books, 2011.

Eugene Thacker, Infinite Resignation, London: Repeater Books, 2018.

Exit Tragedy

Exit TragedyThreads from Rustin Cohle’s philosophy of pessimism and its various sources (some of which are listed above) run all the way through my book Escape Philosophy: Journeys Beyond the Human Body (punctum books). Eugene Thacker says, “Too often philosophy gets bogged down in the tedious ‘working-through’ of contingency and finitude. Escape Philosophy takes a different approach, engaging with cultural forms of refusal, denial, and negation in all their glorious ambivalence,” and Robert Guffey describes it as “a peculiar hybrid of Thomas Ligotti and Marshall McLuhan.”

If you like the dark philosophy of True Detective, check it out!

As always, thanks for reading, responding, and sharing,

-royc.

February 16, 2024

2024 vs 1984

After looking back at the unified election map from 1984 and griping about advertising again, I arrived this week on their intersection: Apple’s 1984 Super Bowl commercial introducing the Macintosh. It launched not only the home-computer revolution but also the Super Bowl advertising frenzy and phenomenon.

The commercial burned itself right into my brain and everyone else’s who saw it. It was something truly different during something completely routine, stark innovation cutting through the middle of tightly-held tradition. I wasn’t old enough to understand the Orwell references, including the concept of Big Brother, but I got the meaning immediately: The underdog was now armed with something more powerful than the establishment. Apple was going to help us win.

Apple has of course become the biggest company in the world in the past 40 years, but reclaiming the dominant metaphors of a given time is an act of magical resistance. Feigning immunity from advertising isn’t a solution, it provides a deeper diagnosis of the problem. Appropriating language, mining affordances, misusing technology and other cultural artifacts create the space for resistance not only to exist but to thrive. Aggressively defying the metaphors of control, the anarchist poet Hakim Bey termed the extreme version of these appropriations “poetic terrorism.” He wrote,

The audience reaction or aesthetic-shock produced by [poetic terrorism] ought to be at least as strong as the emotion of terror—powerful disgust, sexual arousal, superstitious awe, sudden intuitive breakthrough, dada-esque angst—no matter whether the [poetic terrorism] is aimed at one person or many, no matter whether it is “signed” or anonymous, if it does not change someone’s life (aside from the artist) it fails.

Echoing Bey, the artist Konrad Becker suggests that dominant metaphors are in place to maintain control, writing,

The development in electronic communication and digital media allows for a global telepresence of values and behavioral norms and provides increasing possibilities of controlling public opinion by accelerating the flow of persuasive communication. Information is increasingly indistinguishable from propaganda, defined as “the manipulation of symbols as a means of influencing attitudes.” Whoever controls the metaphors controls thought.

In a much broader sense, so-called “culture jamming,” is any attempt to reclaim the dominant metaphors from the media. Gareth Branwyn writes, “In our wired age, the media has become a great amplifier for acts of poetic terrorism and culture jamming. A well-crafted media hoax or report of a prank uploaded to the Internet can quickly gain a life of its own.” Culture jammers, using tactics as simple as modifying phrases on billboards and as extensive as impersonating leaders of industry on major media outlets, expose the ways in which corporate and political interests manipulate the masses via the media. In the spirit of the Situationists International, culture jammers employ any creative crime that can disrupt the dominant narrative of the spectacle and devalue its currency.

"If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face—forever."

— George Orwell, 1984

“It’s clearly an allegory. Most commercials aren’t allegorical,” OG Macintosh engineer Andy Hertzfeld says of Apple’s “1984” commercial. “I’ve always looked at each commercial as a film, as a little filmlet,” says the director Ridley Scott. Fresh off of directing Blade Runner, which is based on a book he infamously claims never to have read, he adds, “From a filmic point of view, it was terrific, and I knew exactly how to do a kind of pastiche on what 1984 maybe was like in dramatic terms rather than factual terms.”

David Hoffman once summarized Orwell’s 1984, writing that “during times of universal deceit, telling the truth becomes a revolutionary act.” As the surveillance has expanded from mounted cameras to wireless taps (what Scott calls, “good dramatic bullshit”; cf. Orwell’s “Big Brother”), hackers have evolved from phone phreaking to secret leaking. It’s a ratcheting up of tactics and attacks on both sides. Andy Greenberg quotes Hunter S. Thompson, saying that the weird are turning pro. It’s a thought that evokes the last line of Bruce Sterling’s The Hacker Crackdown which, after deftly chronicling the early history of computer hacker activity, investigation, and incarceration, states ominously, “It is the End of the Amateurs.”

These quips could be applied to either side.

The Hacker Ethic—as popularized by Steven Levy’s Hackers (Anchor, 1984)—states that access to computers “and anything which might teach you something about the way the world works should be unlimited and total” (p. 40). Hackers seek to understand, not to undermine. And they tolerate no constraints. Tactical media, so-called to avoid the semiotic baggage of related labels, exploits the asymmetry of knowledge gained via hacking. In a passage that reads like recent events, purveyor of the term, Geert Lovink writes, “Tactical networks are all about an imaginary exchange of concepts outbidding and overlaying each other. Necessary illusions. What circulates are models and rumors, arguments and experiences of how to organize cultural and political activities, get projects financed, infrastructure up and running and create informal networks of trust which make living in Babylon bearable.”

If you want a picture of the future now, imagine a sledgehammer shattering a screen—forever.

Following Matt Blaze, Neal Stephenson states “it’s best in the long run, for all concerned, if vulnerabilities are exposed in public.” Informal groups of information insurgents like the crews behind Wikileaks and Anonymous keep open tabs on the powers that would be. Again, hackers are easy to defend when they’re on your side. Wires may be wormholes, as Stephenson says, but that can be dangerous when they flow both ways. Once you get locked out of all your accounts and the contents of your hard drive end up on the wrong screen, hackers aren’t your friends anymore, academic or otherwise.

Hackers of every kind behave as if they understand that “[p]ostmodernity is no longer a strategy or style, it is the natural condition of today’s network society,” as Lovink puts it. In a hyper-connected world, disconnection is power. The ability to become untraceable is the ability to become invisible. We need to unite and become hackers ourselves now more than ever against what Kevin DeLuca calls the acronyms of the apocalypse (e.g., WTO, NAFTA, GATT, etc.). The original Hacker Ethic isn’t enough. We need more of those nameless nerds, nodes in undulating networks of cyber disobedience. “Information moves, or we move to it,” writes Stephenson, like a hacker motto of “digital micro-politics.” Hackers need to appear, swarm, attack, and then disappear again into the dark fiber of the Deep Web.

Who was it that said Orwell was 40 years off? Lovink continues: “The world is crazy enough. There is not much reason to opt for the illusion.” It only takes a generation for the underdog to become the overlord. Sledgehammers and screens notwithstanding, we still need to watch the ones watching us.

Bluesky for Yousky?

Bluesky for Yousky?I’ve been down on social media a lot lately, but I have five Bluesky invitation codes. Of course, I found out after writing this that you don’t need an invitation code to join Bluesky anymore. My dude DC Pierson (Yo!) got me on there, and so far it’s a decent replica of an older, kinder Twitter, both less confusing than Mastodon and less bitchy than Threads. None of these platforms are going to replace those fleeting moments of sublime interaction that used to happen online on a daily basis (j/k), but I’ve been thinking about the potential of my five invitations. If I could converse with five cool people on a semi-synchronous, semi-regular basis, then I could justify my time on the platform. This is my last effort to make it work. So, if you’re interested, join up, follow me, and we’ll see what we can make of it.

And if you’re already on there, follow me.

As always, thank you for reading, responding, and sharing,

-royc.

January 29, 2024

The Gardening

Growing up watching cartoons and slapstick comedies made it seem like rare one-off events like getting stuck in quicksand, slipping on banana peels, and anvils falling from the sky were persistent problems in the world. Not only that, but primetime dramas made it seem like adults could get arrested for anything, and they might never even know the reason! The world seemed dangerous in ways that it really wasn’t.

Posited by George Gerbner in the early 1970s, cultivation theory states that among heavy television viewers, there is a tendency to view the world outside as similar to the world the way the television depicts it. That is, heavy media consumption tends to skew the general views of the media consumer.

Around the turn of the millennium there was a major push in certain underground circles to subvert consensus reality. The internet had connected people according to their esoteric interests (“find the others” as one popular site put it at the time), and it had evolved to a place where they could launch campaigns against the larger culture. Rabble-rousers came together in temporary autonomous zones to jam culture and pull pranks on the squares.

Josh Keyes, “Drift” (2020).

Josh Keyes, “Drift” (2020).A lot has changed since those heady days of us vs them. The squares are all online now, and the mainstream has split into a million tributaries. Online our media diets are now directed by search results that base what we see on what we’ve seen before and what’s popular among others like us. In other words, the algorithm-driven internet is a similarity engine, producing a shameless sameness around our interests and beliefs, cocooning each of us in an impervious reflective armor. This can create what Eli Parser calls a filter bubble, an echo chamber of news, information, and entertainment that distorts our view of the real world. As Parser told Lynn Parramore at The Atlantic,

Since December 4, 2009, Google has been personalized for everyone. So when I had two friends this spring Google “BP,” one of them got a set of links that was about investment opportunities in BP. The other one got information about the oil spill. Presumably that was based on the kinds of searches that they had done in the past.

Combine Gerbner’s cultivation theory and Parser’s filter bubble, and you’ve got a simple recipe for media-enabled solipsism. “Participatory fiction. Choose your own adventure,” the conspiracy theory chronicler Robert Guffey writes. “Virtual reality, but with no goggles necessary.” False microrealities like the Deep State, PizzaGate, and QAnon come alive in this environment. A limited ecosystem produces limited results.

It’s not farming and it’s not agriculture, it’s gardening: each of us hoeing a row, working a plot to grow only the food we want, regardless of what everyone else is eating.

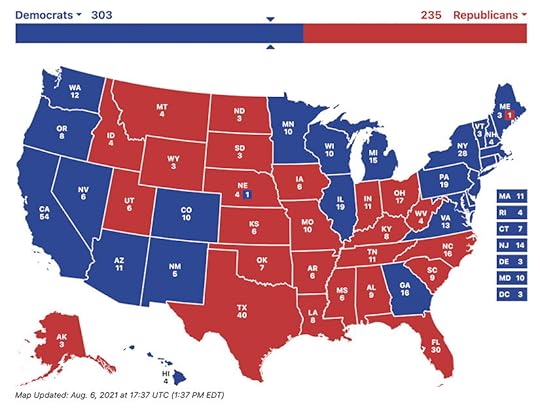

This fragmentation in the United States has never been more evident than during the last few presidential elections. Above is the electoral map from the last one. As the nightly network news spread out into 24-hour cable coverage, so did its audience and its intentions. In his book, After the Mass-Age, Chris Riley writes that instead of trying to get the majority to watch, each network preferred a dedicated minority: “Now you didn't win the ratings war by being objective; you won by being subjective, by segmenting the audience, not uniting them.” And we met them in the middle, seeking out the news that presented the world more the way we wanted to see it than the way it really was. With the further splintering of social media, we choose the news that fits us best. If we're all watching broadcast network news, we're all seeing the same story. If we're all on the same social network, no two of us are seeing the same thing.

Rewind: Above is the electoral map from the 1984 US presidential election. Republican incumbent Ronald Reagan carried 49 of the 50 states, while Walter Mondale pulled only his home state of Minnesota and the District of Columbia. The year 1984 stands as the most united these states have ever been behind a president.

This map is the product of broadcast and print media: one-to-many, mass media like television, radio, newspapers, and magazines. Over the past 40 years those platforms have divided and splintered further and further into unique, individual experiences. The 2020 map above is a product of the internet and social media: many-to-many, multiple sources and viewpoints, and fewer shared mediated experiences.

The medium is only the message at a certain scale, and that scale is diminished.

Reality doesn’t scale in the way that our media depicts it. Nietzsche once called any truth a “useful fiction.” Now that’s all we have, but a lot of them aren’t useful, and none of them are sustainable. A temporary autonomous zone is just that — temporary. There is no longer a consensus to subvert, but we need to know what everyone else is eating if we’re ever going to eat together again.

This is only one of the results of our media gardening. If we share fewer and fewer mediated experiences, some of those disconnections are going to have consequences. Tucked away in the alleys and valleys of our own interests, we stay entrenched in our own tribes, utterly outraged at any other tribe’s dis, disdain, or destruction of one of our own’s preciously held beliefs. The internet has exacerbated these conditions. Instead of more connection, there is a sense of more dis-connection. Where we are promised diversity, we get division. We burrow so deep in our own dirt that we can’t see the world as it really is: a spinning blue ball covered with tiny cells, passive plants, and dumb meat, each just trying to make its own way. Starting from from such focus, we can find ourselves in a place. We can belong at a certain level. It just feels like now we never seem to zoom out far enough to see the whole. Instead of giving us the tools to see the bigger picture, the algorithmic biases of our media feed our own individual biases.

Retreat is not the answer, retreat is the problem. We need more connection, not less — real connection. We need to eat at the same table once in a while. We need to engage more with those who aren’t like us. Lift the little ones, help the ones who need it, and learn as much about each other as we can.

The above essay is more musing from my next book, The Medium Picture, about which Douglas Rushkoff says,

Like a skateboarder repurposing the utilitarian textures of the urban terrain for sport, Roy Christopher reclaims the content and technologies of the media environment as a landscape to be navigated and explored. The Medium Picture is both a highly personal yet revelatory chronicle of a decades-long encounter with mediated popular culture.

And Charles Yu adds,

A synthesis of theory and thesis, research and personal recollection, The Medium Picture is a work of rangy intelligence and wandering curiosity. Thought-provoking and a pleasure to read.

Thank you for reading, responding, and sharing,

-royc.

January 17, 2024

Understanding Mediocre

A new year typically brings renewal and hope. I will admit to struggling to find it in these first couple of weeks of 2024. There are too many things we need to get out from under first. Satisficing, the resigning oneself to the first workable option as sufficient (the word itself a workable but unwieldy portmanteau of “satisfy” and “suffice”), is often considered a good thing, saving one from the needless pursuit of an elusive better or optimal solution. Too much of this good thing leads to the same old thing.

After writing about unintended outcomes and technology not solving problems a few weeks ago, I seem to have closed something else off. Now those unintended outcomes are all I see. Greatness is never achieved through satisficing. The road to mediocrity is paved with just good enough. Now more than ever, we need more than that.

There’s a story under there somewhere, I think.

There’s a story under there somewhere, I think.When you watch a video clip on YouTube, it is typically preceded (and often interrupted) by some sort of advertising. They give you a countdown clock to when the ad is over or to when you can click “skip” and get on with your initial purpose. The very existence of this click-clock indicates that the people at YouTube know that you don’t want to see the ad(s) on their site! They’ve been cracking down on plug-ins to black such ads, and they along with other such “services” offer premium packages where you can eschew all ads for an additional monthly fee (Gee, thanks!).

I mentioned direct mail in the preamble to my previous list, writing that a successful direct-mail advertising campaign has a response rate of 2% and what a waste that is for all involved (98%!). How much mail do you recycle compared to actual mail and written correspondence? Mail seems like an antiquated example, until you go online.

It’s global, yet it’s local.

It’s the next thing in Social.

Hip-hop, rockin’, or microbloggin’ —

You get updates every time you log in.

So, come on in, we’re open,

And we’re hopin’ to rope in

All your Facebook friends and Twitter memories.

There’s a brand-new place for all of your frenemies.

You don’t really care about piracy or privacy.

You just want music and friends as far as the eye can see.

So, sign up, sign in, put in your information.

It’s the new online destination for a bored, boring nation.

Tell your friends, your sister, and your mom.

It’s time for justgoodenough.com

When you log into Instagram and check your notifications (or your other accounts or even your email), how many of them are from people you follow and how many are from spam accounts? Mine are fairly even. That is, I spend as much time on these platforms deleting junk as I do “interacting” with friends and colleagues. I’m sure you have similar experiences.

Where is the break boundary? Where is the point when enough of us have had enough to actually ditch these platforms? I abandon my accounts every other month. None of them are essential after all. YouTube and Instagram are toys at best, amusements for brains trained to seek such tiny nuggets of validation and entertainment, but these same inconvenient priorities spill over into things that do matter. All noise and very little signal. All soggy vegetables and very little pudding.

We’re starving, but… Everything is okay.

Everything is just okay. And it won’t get better until we all demand something else. It won’t get better until we stop satisficing and give each other more of what we want and less of what they want us to have.

To the end of all of the above, I am planning on sending out fewer newsletters this year. I’m trying bi-weekly for now because one every week just seems like too many. Let me know what you think.

Oh, if you know someone who might enjoy this thing, please let them know!

And thank you for reading my words at any frequency,

-royc.

January 1, 2024

A Prayer for 2024

As I do at the beginning of every year, I’m sending you my poem “A Prayer for a New Year.” I wrote this one over 15 years ago, and it still serves as a reminder of all the things I want more and less of (I am aware of the grammatical inconsistencies in this piece, but I left them in for the sake of parallel structure. Call it “poetic license.”).

Whether you dig on poetry or not, please do take a moment with this one.

“Rabbit, rabbit… White rabbit.”

“Rabbit, rabbit… White rabbit.”More stretch, less tense.

More field, less fence.

More bliss, less worry.

More thank you, less sorry.

More nice, less mean.

More page, less screen.

More reading, less clicking.

More healing, less picking.

More writing, less typing.

More liking, less hyping.

More honey, less hive.

More pedal, less drive.

More wind, less window.

More in action, less in-tow.

More yess, less maybes.

More orgasms, less babies.

More hair, less cuts.

More ands, less buts.

More map, less menu.

More home, less venue.

More art, less work.

More heart, less hurt.

More meaning, less words.

More humans, less herds.

More verbs, less nouns.

More funny, less clowns.

More dessert, less diet.

More noise, less quiet.

More courage, less fear.

More day, less year.

More next, less last.

More now, less past.

More Poetry:

More Poetry:If you do dig on poetry, the poem above and many more are collected in my book Abandoned Accounts, about which Bristol Noir says, “Perfectly balanced prose. With the subtext, gravitas, and confidence of a master wordsmith. It’s a joy to read.”

Also, if you have a gift card you need to burn, I have several other recent books available! Check them out!

Happy 2024!

Thank you for your continued interest in my work and words,

-royc.

December 26, 2023

Idea, Reality, Lesson

Unintended outcomes are the furniture of our uncertain age. Decades of short-term thinking, election cycles, and bottom lines assessed quarterly have wound us into a loop we can’t unwind. In addition, our technologies have coopted our desires in ways we didn’t foresee. The internet promised us diversity and gave us division. Social media promised to bring us together, instead it fomented frustration and rage between friends and among family. We know the net result is bad, but we won’t abandon these poisonous platforms.

As straw-person an argument as it might be, direct mail is my favorite example. Successful direct-mail advertising has a return rate of 2%. That means that in a successful campaign, 98% of the effort is wasted. In any other field, if 98% of what you’re doing is ineffective, you would scrap it and start over.

I’ve been thinking about case studies of ineffective efforts and unintended outcomes, and I came up with five for your consideration — IRL: Idea, Reality, Lesson.

“Shadow Play,” Sharpie on paper, 2005.

“Shadow Play,” Sharpie on paper, 2005.Idea: AI as a tool for creativity.

Reality: Training large-language models (and the other software that currently pass as artificial intelligence) to be “creative” requires the unpaid labor of many writers and artists, potentially violating copyright laws, relegating the creative class to the service of the machines and the people who use them.

Lesson: Every leap in technology’s evolution has winners and losers.

Idea: Self-driving cars will solve our transportation problems.

Reality: Now you can be stuck in traffic without even having to drive.

Lesson: We don’t need more cars with fewer drivers. We need fewer cars with more people in them.

Idea: Put unused resources to use.

Reality: The underlying concept of companies like Uber and AirBnB—taking unused resources (e.g., vehicles, rooms, houses, etc.) and redistributing them to others in need—is brilliant and needed in our age of abundance and disparity. Instead of using what’s there, a boutique industry of rental car partnerships for ride-share drivers and homes bought specifically for use as AirBnB rentals sprung up around these app-enabled services. Those are fine, but they don’t solve the problem the original idea set out to leverage.

Lesson: You cannot disrupt capitalism. Ultimately, it eats everything.

Idea: Content is King.

Reality: When you can call yourself a “Digital Content Creator” just because you have a front-facing camera on your phone, then content is the lowest form. To stay with the analogy, Content is a peasant at best. Getting it out there is King. Getting and maintaining people’s attention is Queen.

Lesson: Distribution and Attention are the real monarchy.

Idea: Print is dead.

Reality: People have been claiming the death of print since the dawn of the web—over 30 years now—and it’s still patently untrue. Print is different, but it’s far from dead. Books abound! People who say this don’t read them anyway. Just because they want synopses and summaries instead of leisurely long reads doesn’t mean that everyone wants that.

Lesson: Never underestimate people’s appetite for excuses.

If more of what you’re doing is wasteful rather than effective, then you should rethink what you’re doing. Attitudes about technology are often incongruent with their realities, and the way we talk about its evolution matters. Moreover, while many recent innovations seem to be helping, there are adjacent problems they’re not solving. Don’t be dazzled by stopgap technologies that don’t actually solve real problems.

Print Lives!

Print Lives!I know you have some holiday gift cards about to burst into flames. Might I suggest using one on a book or two? I have several available. Check them out!

Thanks for reading.

Happy 2024!

-royc.

December 12, 2023

In Praise of Pulling Back

I wrote this essay three years ago, and it’s become one of my more popular newsletters. So, after I wrote a jumbley, rambley bit to share with you, I decided this one has a more germane message and reminder for this week: Stop looking for excuses and shortcuts. You have everything you need.

In the creative process, constraints are often seen as burdens. Budgets are too small, locations inaccessible, resources unavailable. Sometimes, though, the opposite is true. Sometimes a multiplicity of options can be the burden.“In my experience,” writes Brian Eno, “the instruments and tools that endure… have limited options.” Working with less forces us to find better, more creative ways to accomplish our goals. As sprawling and sometimes unwieldy as movies can be, low-budget and purposefully limited projects provide excellent examples of doing more with less.

Like many of us, the filmmakers James Wan and Leigh Whannell started off with no money. The two recent film-school graduates wrote their Saw (2004) script to take place mostly in one room. Inspired by the simplicity of The Blair Witch Project (1999), the pair set out not to write the torture-porn the Saw franchise is known for, but a mystery thriller, a one-room puzzle box. Interestingly, like concentric circles, the seven subsequent movies all revolve around the events that happen in that first room. They’re less a sequence and more ripples right from that first rock. And let’s not forget that the original Saw is still one of the most profitable horror movies of all time, bettered by the twig-thin budget of The Blair Witch Project and the house-bound Paranormal Activity (2007), two further studies in constraint.

Coherence (2013): A story small enough to tell among friends over dinner but big enough to disrupt their beliefs about reality.

Coherence (2013): A story small enough to tell among friends over dinner but big enough to disrupt their beliefs about reality.James Ward Byrkit’s Coherence (2013) is also the product of pulling back. After working on big-budget movies (e.g., Rango, the Pirates of the Caribbean series, etc.), Byrkit wanted to strip the process down to as few pieces as possible. Instead of a traditional screenplay, he spent a year writing a 12-page treatment. Filmed over five nights in his own house, Coherence documents a dinner party gone astray as a comet flies by setting off all sorts of quantum weirdness. The story is small enough to tell among friends over dinner but big enough to disrupt their beliefs about reality. With the dialog unscripted, the film unfolds like a game. Each actor was fed notecards with short paragraphs about their character’s moves and motivations. Like a version of Clue written by Erwin Schrödinger, Coherence works because of its limited initial conditions, not in spite of them.

Hard Candy (2005): Patrick Wilson and Elliot Page square off in close quarters.

Hard Candy (2005): Patrick Wilson and Elliot Page square off in close quarters.When the producer David W. Higgins was developing the film Hard Candy (2005), he knew the story should play out in the tight space of a single room or a small house, so he hired playwright Brian Nelson to write the script. Not as cosmic as Coherence, Hard Candy nonetheless tells a big story in as small a space and with fewer people. The budget was intentionally kept below $1 million to keep the studio from asking for changes to the controversial final product — another self-imposed constraint in the service of freedom. Tellingly, Nelson also wrote the screenplay for Devil (2010), which transpires almost entirely in the confines of an elevator.

“Try to do something on the right scale, something that you can do yourself.”

— Laurie Anderson

The first time I saw Laurie Anderson was on Saturday Night Live. I was 15. I will never forget that night, standing in my parents’ living room aghast. I was as intrigued as I was terrified. Her pitch-shifted voice and the stories she told… She performed the songs “Beautiful Red Dress” and “The Day the Devil.” When her next record, Strange Angels, came out in 1989, I got it on cassette, CD, and LP. I don’t know why. I just had to have it on all available formats. She has been one of my all-time favorite people ever since. “Try to do something on the right scale, something that you can do yourself,” she explains in the interview above, acknowledging another aspect of external constraints: We have to stop thinking that access to the Big Equipment is going to solve all of our problems. If we look, we quite often have everything we need.

Suga Free is one of my favorite West Coast rappers. In the live, house-arrest version of “Do It Like I’m Used to It” below, he illustrates how a lack of resources can’t hold back a great artist. As Anderson says in the clip above, “Very dangerous art can be made with a pencil.” In this case from 1995, Suga Free uses a ballpoint pen, a nickel, and a dining-room table to put together a whole-ass song: “pen and nickel, in the Nine-Nickel.”

In a much less-impressive house-bound version, sometime during the lockdown I did a virtual reading of my short story “Not a Day Goes By” for The Sager Group (Don’t worry, my hair has long since been cut). The story is about a guy stuck in a Groundhog Day-like time-loop, so it should feel familiar to those adhering even marginally to quarantine rules. If you’d rather read the story than listen to me mumble through it, it was published on Close to the Bone today.

Narratives have personalities we have relationships with. An audience can’t get to know something that continually evolves into something else. Eno concludes, “A personality is something with which you can have a relationship. Which is why people return to pencils, violins, and the same three guitar chords.” Personalities have limits. Intimacy requires constraints. Don’t let lack of resources stop you from pursuing a project. The end result might be better anyway.

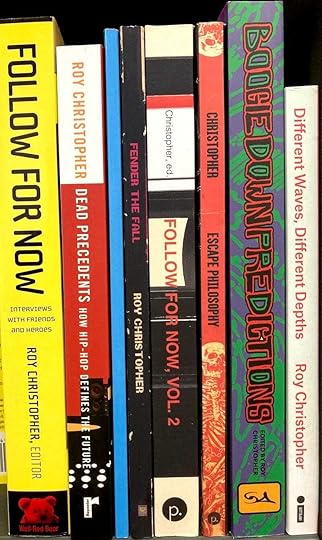

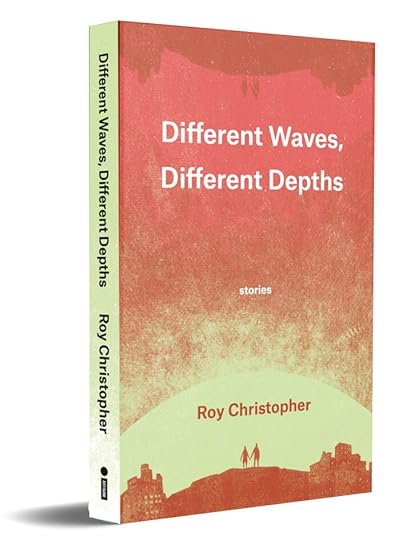

Different Waves Await

Different Waves Await“Not a Day Goes By” and 8 other stories are included in my most recent book, Different Waves, Different Depths (Impeller Press). I’m quite proud of these stories, Patrick Barber’s design, and Jeffrey Alan Love’s cover illustration. It’s the perfect package, and it makes a great and unique gift, along with my other recent books.

Get some!

Hey, I currently have a book under review at an academic press, and my birthday is Friday, so think happy thoughts!

As always, thank you for reading, responding, and sharing. I appreciate your attention.

Let’s make stuff,

-royc.

December 4, 2023

Artificial Articulation

No one reads. People say this all the time, and as a writer, it’s very hard to hear. If I’m ever forced to start a podcast, that will be the reason, and it might be the name. If no one reads, why are we outsourcing writing? According to a recent article on Futurism, sports magazine Sports Illustrated allegedly published reviews generated by artificial intelligence. Not only that, but the bylines on those articles belonged to writers who weren’t real either.

Drew Ortiz, a “Product Reviews Team Member” for Sports Illustrated.

Drew Ortiz, a “Product Reviews Team Member” for Sports Illustrated.Meet Drew Ortiz, a “neutral white young-adult male with short brown hair and blue eyes” (likely on purpose), and a “Product Reviews Team Member” for Sports Illustrated. One of Drew’s many articles for SI claims that volleyball “can be a little tricky to get into, especially without an actual ball to practice with.” True enough, Drew, but it’s also tricky to get into if you don’t have an actual body to practice with either.

Look, Drew is just like you and me.

Look, Drew is just like you and me.Drew was eventually replaced briefly by Sora Tanaka, a “joyful asian young-adult female with long brown hair and brown eyes.” Futurism also notes Jim Cramer’s TheStreet hosting articles by Domino Abrams, Nicole Merrifield, and Denise McNamera — all pseudonyms for AI-generated pseudoscribes.

Sora Tanaka, a “joyful asian young-adult female with long brown hair and brown eyes.”

Sora Tanaka, a “joyful asian young-adult female with long brown hair and brown eyes.”Given that this path was paved when we first outsourced our thinking to written language, it’s perhaps most fitting that what passes for artificial intelligence these days are large language models, none of which can play volleyball but can write about it. The computer scientists Allen Newell and Herbert A. Simon defined thinking in just such terms, writing, “A physical symbol system has the necessary and sufficient means for general intelligent action.” The externalization of human knowledge has largely been achieved through text — a physical symbol system. Cave paintings, scrolls, books, the internet. Even with the broadening of bandwidth enabling sound and video, all of these media are still heavily text-based.

In a paper from 1936 titled “On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem,” the mathematician and computer scientist Alan Turing posited that humans compute by manipulating symbols that are external to the human brain and that computers do the same. The paper serves as the basis for his own Universal Turing Machine, algorithms, and the fields of computer science and AI.

I am admittedly a lapsed student of AI, having dropped out of the University of Georgia’s Artificial Intelligence masters program midway through my first semester there in the late 1990s. My interest in AI lies in the weird ways that consciousness and creation butt heads in the midst of such advanced technologies. As Al Burian sings on the Milemarker song “Frigid Forms Sell You Warmth,” “We keep waiting for the robots to crush us from the sky. They sneak in through our fingertips and bleed our fingers dry.” If humans have indeed always been part technology, where do the machines end and we begin? As the literary critic N. Katherine Hayles told me years ago,

In the twenty-first century, text and materiality will be seen as inextricably entwined. Materiality and text, words and their physical embodiments, are always already a unity rather than a duality. Appreciating the complexities of that unity is the important task that lies before us.

“Manufacturing Dissent” multimedia on canvas by me, c. 2003.

“Manufacturing Dissent” multimedia on canvas by me, c. 2003.In his book Expanded Cinema (1970), the media theorist and critic Gene Youngblood conceived television as the “software of the world,” and nearly a decade later in their book Media Logic (1979), David Altheide and Robert Snow argue that television represents not only the totality of our culture, but that it gives us a “false sense of participation.” With even a marginally immersive medium like television one needn’t upload their brain into a machine to feel it extending into the world, even as the medium itself encroaches on the mind.

A medium is anything that extends the senses or the body of humans according to Marshall McLuhan in his classic Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (1964). More specifically, McLuhan saw the “electronic media” of the time — radio, telephone, television — as extensions of our nervous system. Jussi Parikka writes that we must stop thinking about bodies as closed systems and realize that they are open and constituted by their environment, what Humberto Maturana and Francisco J. Varela call “structural coupling.” Our skin is not a boundary; it is a periphery: permeable, vulnerable, and fallibly open to external flows and forces through our senses. Parikka adds, “[W]e do not so much have media as we are media and of media; media are brains that contract forces of the cosmos, cast a plane over the chaos.” We can no longer do without, if we ever could.

Our extensions have coerced our attentions and intentions.

We are now the pathological appendages of our technological assemblages.

Desire is where our media and our bodies meet. It’s where our human wants blur with our technologies. It is the inertia of their meeting and their melding, whether that is inside our outside our bodies is less relevant than whether or not we want to involve ourselves in the first place. Think about the behaviors that our communication technology affords and the ones we find appropriate. They’re not the same. Access is the medium. Desire is the message.

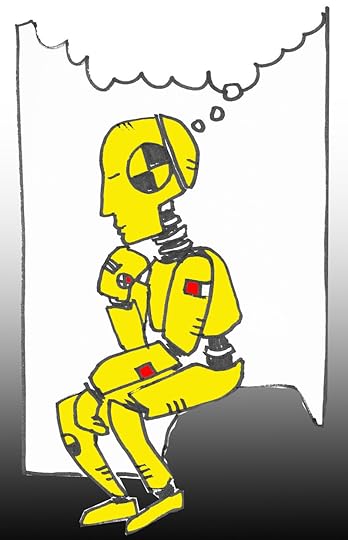

Crash-testing intelligence [Sharpies and Photoshop by me, 2023].

Crash-testing intelligence [Sharpies and Photoshop by me, 2023].Steve Jobs once said that the personal computer and the television would never converge because we choose one when we want to engage and the other when we want to turn off. It’s a disparity of desire. A large percentage of people, given the opportunity or not, do not want to post things online, create a social-media profile, or any of a number of other web-enabled sharing activities. For example, I do not like baseball. I don’t like watching it, much less playing it. If all of the sudden baseballs, gloves, and bats were free, and every home were equipped with a baseball diamond, my desire to play baseball would not increase. Most people do not want to comment on blog posts, video clips, or news stories, much less create their own, regardless of the tools or opportunities made available to them. Cognitive surplus or not, its potential is just that without the collective desire to put it into action. Just because we can doesn’t mean we want to.

The Turing Test, which is among Alan Turing’s other top contributions to the fields of computer science and artificial intelligence, is more accurately a test of the human who’s interacting with the machine. The test, as outlined in Turing’s 1950 article “Computing Machinery and Intelligence,” states that a machine is considered to be truly thinking like a human if it can fool a human into thinking it is (a.k.a. “The Imitation Game”). So, according to the language and the lore, artificial intelligence doesn’t have to be real, it just has to be convincing. Now that Drew Ortiz, Sora Tanaka, and the other machines can do these symbol-manipulation tasks for us, we’ve outsourced not only our knowledge via text but now the writing of that knowledge, not quite the thoughts themselves but the articulation thereof.

The Medium Picture

The Medium PictureThe above is another edited excerpt from my next book, The Medium Picture, about which Douglas Rushkoff has the following to say:

Like a skateboarder repurposing the utilitarian textures of the urban terrain for sport, Roy Christopher reclaims the content and technologies of the media environment as a landscape to be navigated and explored. The Medium Picture is both a highly personal yet revelatory chronicle of a decades-long encounter with mediated popular culture.

More on this project soon.

Thank you for reading words from a real human being,

-royc.