Roy Christopher's Blog, page 4

December 4, 2024

DC Pierson: Time in the Box

My favorite actors tend to play minor characters. There’s something truly special about the MVPs on the sidelines who score wins for the team without much notice. They get bonus points if they’re also writers behind the scenes. DC Pierson has haunted the edges of my psyche for years. He’s popped up on Community, 2 Broke Girls, Key and Peele, Weeds, and a few Verizon commercials, among other places. Somewhere along the way, I started following his social media antics, subscribed to his newsletter, and found his books. A creator in the true Renaissance style, Pierson can do anything — and make it funny.

DC Pierson. Photo by Ari Scott.

DC Pierson. Photo by Ari Scott.I first saw Pierson in 2009’s Mystery Team, a collaboration between him Dominic Dierkes, Dan Eckman, Donald Glover, and the inimitable Meggie McFadden, that also features Aubrey Plaza, Ellie Kemper, Bobby Moynihan, John Daly, Neil Casey, Kay Cannon, and Matt Walsh, among others. It’s a juvenile adventure that feels like hanging out with your friends, causing mischief during a summer in middle school.

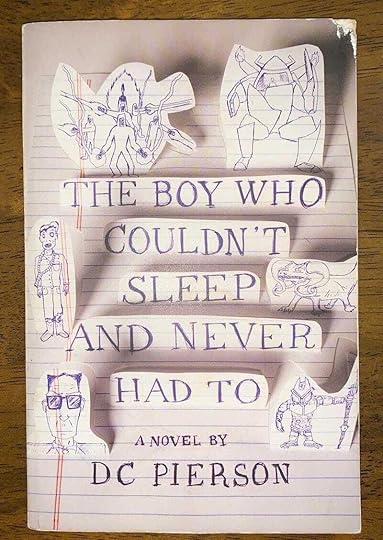

Pierson has also written for the VMAs and MTV Movie Awards. A veteran of improv comedy, his latest creations, “The Architect Who Built New York” video series and an adaptation of his first novel, The Boy Who Couldn’t Sleep and Never Had To (Vintage, 2010), are no less silly than his first— and no less serious.

Roy Christopher: I first saw you in Mystery Team (2009), which you co-wrote. In the meantime, the cast and crew of that movie has become a who's who of modern comedy. How did that project come about?

DC Pierson: That project was the (probably? We’ll see) culminating effort of DERRICK comedy, a sketch group I was in with Donald Glover, Dominic Dierkes, Dan Eckman, and Meggie McFadden. We’d made a lot of videos that got popular at the dawn of the YouTube era and pooled any money we made from touring, merchandising, and the barest beginnings of monetization, and along with some money from friends and family were able to shoot a feature. Prior to that we’d written a feature we wanted to try and get made the traditional way, and when it became clear that wasn’t gonna happen we wrote something we could conceivably make on an indie budget, including using Meggie’s parents’ house or Dan’s uncles’ hardware store / warehouse in Manchester, NH as shooting locations.

Dominic Dierkes, D.C. Pierson, and Donald Glover in Mystery Team (2009).

Dominic Dierkes, D.C. Pierson, and Donald Glover in Mystery Team (2009).Production scrappiness aside the most important part of that process was the writing. Time being money and all we knew we weren’t going to have the chance to improvise a bunch on set and do a bunch of takes. There were a few opportunities to do a little of that i.e., Matt Walsh’s scene with Jon Lutz at the office party late in the movie or Bobby Moynihan’s scenes in the supermarket, but at that point it’s not like you’re rolling for ten minutes hoping somebody will find what’s funny about the scene. You already have something serviceable written and are just watching a couple genius actor-improvisers make it even better like five times in a row and then you get to pick the best one. Going into it with a script where the story, characters, and especially jokes were all solid on the page was key. A lot of that was down to Dan and Meggie’s sense of what was feasible and achievable on a production level — and it deserves to be said, Dan’s ambition and visual sense really kind of made the videos and movie what they were in many ways, and Meggie figuring out how we could actually do stuff in a professional way really none of us were qualified to do in our late teens and early, early 20s — combined with Donald‘s experiences writing for 30 Rock that very much set the tone and the bar for the writing process.

And as for the casting, as you mentioned, we were really just pulling from people in the UCB community in New York that we were part of at that time. It was an incredibly cool scene to be a part of, and I’m still super grateful for it.

RC: That was right at the beginning of the social-media age, and you've leveraged several platforms for comedic purposes. Have you had a plan for those or do you just improvise as needed?

DCP: Ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha, no. It’s more like just keep swimming and try to stay visible. I think I took to Twitter because for better or for worse, I like wordplay and obscure pop culture references, and those both happened to be things that were valuable in that medium. It’s been a slower time adjusting to things like Instagram and TikTok, but I think I’m getting there now especially since I’ve decided to embrace making essentially short short solo sketch videos. It’s a combination of where the technology’s at, that I can just make them and edit them on my phone and the computer and don’t have to be terrifically skilled, with the fact that I come from a sketch background. And even though I don’t think it will become as bigger universal as Twitter was in a day, I am having a lot of fun on Bluesky, which is largely a text based platform like Twitter. We’ll see how it plays out, but at the moment it has a good community vibe.

I also have to say I share a certain weariness. A lot of people who are freelancers of various stripes, be they visual artists or actors or journalists or Drag performers of constantly having to schlep our wares from platform to platform, most of which seem Paternally hostile to promotion of any kind, even though we’re told that’s what we have to do and to be honest it is what we have to do. I guess in my case, maybe it karmically balances out because what we were making in DERRICK really did come along exactly the right time for how small YouTube was but that it existed at all. Granted, none of these things were as developed or capricious or even pernicious as they are these days and maybe that’s part of what was so lucky.

RC: You've been very prolific, and your newsletter is especially erudite and hilarious. Do you publish or perform everything you come up with, or do you save some things for longer or larger releases?

DCP: Thank you! I have fun doing it, but haven’t done it as much in the last year for various scarcity of bandwidth reasons. I would say in all forms I probably execute like 10% of the ideas I come up with, but that might be a very generous definition of the word idea. I also think — and here I’m quoting Tom Scharpling, author and host of The Best Show who I think is quoting someone else from his life: The execution is really all that matters, ideas are cheap. Of things I actually execute, like write a draft or shoot some of, most of those get out there. I’m not sitting on like a giant archive of unpublished work, though weirdly network effects and internet attention spans being what they are, it’s kind of like anyone who makes things is sitting on a giant archive of unpublished work because it seems like if you’re not constantly surfacing your own stuff, the kind of attention span Eye of Sauron immediately moves off of them. That said, I do have a an essay about going to see the Postal Service and Death Cab like a year ago that I wrote around that time and just never sent out for whatever reason, so thanks for the reminder.

Oh also, even as I say that I have a rough draft of a new book completed, and I need to like lower myself into the whale carcass of that at some point and finish it. More than anything it’s just a debt of honor I owe myself at this point.

RC: “ Execution over ideas.” Did you find that as hard to hear as I did?

DCP: Oh, for sure! And if you’re like me — which we all are, in this way — you’re getting older. So if you think about it for two seconds, or stop trying not to think about it, you realize that the horizon for doing all the ideas is getting smaller. That’s a panicky feeling but there’s also something freeing about it. Less time for doing things that seem like a generically good idea rather than the most You idea, the thing that you’re the most excited about.

RC: Your books were the next thing I was going to ask about. I don’t agree with them, but writers always seem to talk about how hard and thankless it is. Do you enjoy the practice of writing?

DCP: I do! I think I’ve even gotten quasi defensive of it in the post ChatGPT era — like, as long as we’ve been putting pen to paper or pushing the cursor forward writers have been complaining about the drudgery and the solitude of writing, and now all the sudden all these tech bros are coming out of the woodwork claiming to have “solved” it and it’s like, hold on — that’s our solitude and drudgery! It’s like the line from some 90s kids movie — “nobody hits my brother but me!”

There was a line in Top Gun: Maverick that resonated with me (a lot actually! I loved that movie!) about how even with all this modern war-fighting technology, success or failure in one of these insane dogfights those Top Gun rascals are always getting themselves into still comes down to "the man in the box," i.e., the human being in the really expensive fighter plane. The movie is a really thinly veiled metaphor for Cruise’s own feelings about old-fashioned movie craftsmanship and exhibition vs. the new degraded and rapidly diminishing versions of those things, feelings I happen to strongly share, so that helped. But also, the phrase immediately resonated with me as a good way to explain that ineffable and sometimes frustrating feeling of being a writer who is actually sitting down and writing.

I also have done a fair amount of writing for award shows and things, and when I got to the point where I was head-writing the shows, I realized what a lot of people who've done something long enough to ascend into a quasi-management position learn: You get separated from the thing you love that got you there in the first place. I would spend 99% of my time delegating or fielding emails from other people in charge of other parts of the show or in meetings or on calls. I'd be desperate to have time to just sit down and bang out drafts of things we needed for the show but wouldn't really be able to. Unfortunately (or fortunately) I think I’m pretty good at all that other stuff too, but it’s way less specialized. A gajillion people can type “circling back” in an email window. Not everybody can be (or wants to be) the proverbial Man in the Box. Also the world will intercede in infinite ways to keep you from being that (hu)Man. That line in the Top Gun sequel was a good reminder to try and maximize my time in the box.

RC: My parents were never into music and subsequently have never really understood my life-long love and interest in it. You had a very different experience. Can you tell me a little about that?

DCP: Dang!! Well I'm sorry it wasn't something you grew up with in the house very much but it doesn't seem to have stopped you getting immersed in it — maybe because it was something you had to actively seek out or used to define yourself as a separate entity. (That unsolicited uncredentialed faux-therapy will be $125, please). I didn't grow up in a musical household the same way many friends of mine who themselves are way more “musical,” as in, playing instruments or singing, did — like, it wasn't a thing where my mom played piano or my dad and uncle would get guitars out and jam at family gatherings. But my parents were both pretty typical boomers (complimentary, in this instance) in that they both had really close relationships to the music they grew up on (The Beatles in my mom’s case and 70s rock in my dad’s) and my dad maintained an active interest in new music his whole life (my mom probably would've as well but she died when I was 12 — you can actually just repay me in some therapy about that).

The times I’m most grateful for now, as I wrote about in this essay, are evenings when I’d be visiting home as an adult and some combination of me, my dad, and my brothers would hang out on the couch in the living room in front of my dad and stepmom's state-of-the-art-at-the-time home entertainment system and switch off playing songs from our laptops. It was a lucky collision of where the technology was at — the peak iPod / iTunes era — and where we were at in our lives as father and adult / college / older teenage sons, and a lot of emotional conversations that might not have happened otherwise were had. Those are the times I most value and the thing I’d most like to have back, though my dad's gone now too. ROY, MAKE WITH THE THERAPY, PLEASE!!

It’s funny, I've been realizing recently that some music has gone from “this reminds me of my dad” — like, folky, quasi-ambient Windham Hill records or cool jazz played by white dorks who looked like NASA engineers — to “this is just music I like and actively want to seek out.” They say you become your parents and if this a form it takes for me, great. I will be listening to some of the mellowest shit of all time.

RC: What else is coming up in the DC Universe?

DCP: So much, I hope! Continuing to work on a feature script adaptation of my first book The Boy Who Couldn’t Sleep And Never Had To with my pals Dan Eckman and Meggie McFadden. It’s a process that’s had various fits, starts, and tantalizing near-misses with fruition over the years — and along we made this proof of concept short that still rules imo — and it’s at a phase where it’s the most exciting it’s been a long time .

I’m working on a live show with my very talented writer, actor friend Robbie Sublett that I’m also super excited about. It kind of ties in with exactly where we are in our lives and careers while also — hopefully — having a hook that gets people in the door. To be announced on that front.

I’ve also been posting a lot more short comedy videos to Instagram and TikTok and such, particularly a series where I play “The Architect Who Designed New York,” basically an excuse to walk around and make short, silly, one-liners I can then cut together based around stuff I see. Been really enjoying that. Every time I set out to shoot one I end up with enough material for almost two, so it keeps rolling.

UNF Filmmaking Club IntroductionIf you’re not interviewed out, Aidan Fridman and the Filmmaking Club at the University of North Florida sat me down for a short video about writing and teaching. Check it out!

Many thanks to DC Pierson for his time and thorough responses, and thank you for reading, subscribing, and sharing,

-royc.

November 8, 2024

Torn Together

I first experienced Eli Pariser’s fabled filter bubble twenty years ago, before scrolling the fevered feeds of social media had such a hold on us. I didn’t have a television, but my ex-girlfriend had one stored in our garage. I pulled it out specifically to watch the 2004 election coverage on the news. George W. Bush was up for reelection against challenger John Kerry. For the two years leading up to this election, I had been in graduate school in San Diego. So, no, I didn’t know anyone who liked Bush, no one who didn’t make fun of him, not a single person who had nice things to say. To be fair, I didn’t really know anyone who liked Kerry either, but…

I sat there, by myself, in front of that small cathode-ray television tube, wondering what the hell I was seeing. How could this many people be voting for the guy I was sure didn’t have a single fan on the continent?

That’s what it looks like when your bubble bursts, and you’re exposed to the cold light of consensus reality. That’s when you realize you were duped, but by whom?

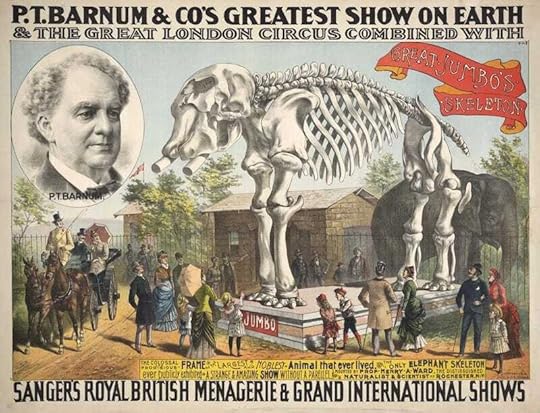

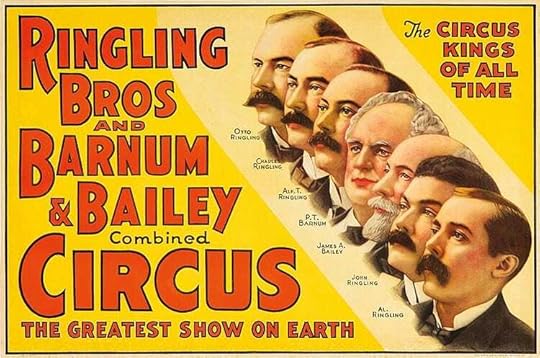

One of the first non-children books I read was a biography of P. T. Barnum. My middle-school mind was fascinated by his brash persona and his blatant sloganeering. “There’s a sucker born every minute,” he supposedly once said as he curated freak shows and curiosities and co-created the Barnum and Bailey Circus, “The Greatest Show on Earth.” Thankfully as a young impressionable mind, I didn’t internalize his con-man values. Maybe if I had, I wouldn’t need side jobs.

But the silver lining isn’t cynicism, nor are koans like that lost on the tricksters and trolls gatekeeping the path. Everybody knows everything yet fails to notice how far they have left to go and how little air they have left to breathe. That’s one of the defining features of a bubble: It’s sealed. Airtight.

“One of the saddest lessons of history is this: If we’ve been bamboozled long enough, we tend to reject any evidence of the bamboozle. We’re no longer interested in finding out the truth. The bamboozle has captured us. It’s simply too painful to acknowledge, even to ourselves, that we’ve been taken.” ― Carl Sagan, The Demon-Haunted World

But we don’t need the internet to be blind to the blight around us, stuck not seeing the things about the world we find too disturbing to know, too annoying to think about, or just plain too inconvenient to consider. We do a lot of it on our own. We all wander through the world with blurry lenses, what the literary theorist Kenneth Burke called “terministic screens.” Have you ever learned a new word and then started seeing it everywhere? Burke would say that it was always there, but you were filtering it out, obscuring it with ignorance. Once it became a part of your terministic screen, then you started seeing it.

Outside the circus, Barnum’s resonant ideas rang much louder than simply hawking curiosities for cash. He served two terms as a Republican in the Connecticut legislature, as well as serving as mayor of Bridgeport, Connecticut. Arguing for the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, the abolitionist Barnum said, “A human soul, ‘that God has created and Christ died for,’ is not to be trifled with. It may tenant the body of a Chinaman, a Turk, an Arab, or a Hottentot—it is still an immortal spirit.” In spite of his outdated nomenclature, the man most known as a 19th-century huckster had more progressive ideas than many of the current lot.

Now the terministic screens are actual screens, shiny rectangles, radiant with outrage. Now the most lucrative approach to news is anything that foments fear, anger, and resentment: any reaction is great, but rage is preferred and more profitable. Now the bubbles are smaller, stronger, and finding one’s way out is a lot more difficult. Any semblance of distortion your reality may have been teasing you with, easing your mind with a blur on the lens, a national election will quickly clear up for you. Your brain left broken, your shelter shattered.

Thanks for reading,

-royc.

October 28, 2024

What’s Your Favorite Scary Movie?

In the stray fourth installment of the Scream franchise, cinema club president Charlie Walker (played by Rory Culkin) describes the Stab movie in the making, as well as the aims of the killers in Scream 4 itself, saying they’re making “less of a shrequel and more of a screamake.”

Mindy Meeks-Martin (Jasmin Savoy Brown) explains the rules in 5CREAM (2022).

Mindy Meeks-Martin (Jasmin Savoy Brown) explains the rules in 5CREAM (2022).Mindy Meeks-Martin (Jasmin Savoy Brown) explains in Scream 5, “It sounds like our killer’s writing his own version of Stab 8, but doing it as a requel.” She adds, “Or a legacy-quel. Fans are torn on the terminology,” self-referentially explaining the existence of Scream 5 in the process. She continues:

See, you can't just reboot a franchise from scratch anymore. The fans won’t stand for it. Black Christmas, Child's Play, Flatliners, that shit doesn't work. But you can’t just do a straight sequel, either. You need to build something new. But not too new or the Internet goes bug-fucking-nuts. It has to be part of an ongoing storyline, even if that story should never have been going on in the first place. New main characters, yes, but supported by, and related to, legacy characters. Not quite a reboot, not quite a sequel, like the new Halloween, Saw, Terminator, Jurassic Park, Ghostbusters, fuck, even Star Wars. It always, always goes back to the original!

In addition to one of the Meeks laying out the rules, in all of the Scream movies, the killer asks the famous question, “What’s your favorite scary movie?” In Scream 4, when the live-streaming vlogger Robbie Mercer (Erik Knudsen) asks Kirby Reed (Hayden Panettiere), she answers, “Bambi.”

“How do you understand a thing by its shadow

when you don’t even know how shadows are thrown?”

– M. John Harrison, Wish I Was Here

I was three-years old when went to see my first movie in the theater, and the movie was Bambi. Like the titular fawn in Disney’s cartoon, I spent most of my time as a child with my mom. As soon as Bambi’s mom was killed on the screen, mine had to drag me out of the theater, wailing my head off. My disdain for Disney has never relented.

In his 2022 book Cinema Speculation, Quentin Tarantino waxes nostalgic about the many adult movies he watched as a child. He accompanied his mom and stepdad to everything from Dirty Harry and Deliverance to Hardcore and Taxi Driver. Aside from a few autobiographical essays and a couple of critical homage, each chapter of the book is about a different movie, save the two chapters deservedly devoted to Taxi Driver, making Cinema Speculation a sort of memoir through movies.

In the introductory chapter, “Little Q Watching Big Movies,” Tarantino talks about being a grom in a grown-up world:

When a child reads an adult book, there’s going to be words they don’t understand. But depending on the context, and the paragraph surrounding the sentence, sometimes they can figure it out. Same thing when a kid watches an adult movie.

Now obviously, some things that go over your head, your parents want to go over your head. But some things, even if I didn’t exactly know what they meant, I got the gist.

It was fucking thrilling to be the only child in a packed room of adults watching an adult movie and hearing the room laugh at (usually) something I knew was probably naughty. And sometimes even when I didn’t get it, I got it.

Bambi, Flower, and Thumper in Walt Disney’s Bambi (1942)

Bambi, Flower, and Thumper in Walt Disney’s Bambi (1942)Eventually he addresses the reader’s concern with his young mind consuming the mature nature of such films, writing:

Was there any movie back then I couldn’t handle?

Yes.

Bambi.

Bambi getting lost from his mother, her being shot by the hunter, and that horrifying forest fire upset me like nothing else I saw in the movies. It wasn’t until 1974 when I saw Wes Craven’s The Last House on the Left that anything came close. Now those sequences in Bambi have been fucking up children for decades. But I’m pretty sure I know the reason why Bambi affected me so traumatically. Of course, Bambi losing his mother hits every kid right where they live. But I think even more than the psychological dynamics of the story, it was the shock that the film turned so unexpectedly tragic that hit me so hard. The TV spots really didn’t emphasize the film’s true nature. Instead they concentrated on the cute Bambi and Thumper antics. Nothing prepared me for the harrowing turn of events to come. I remember my little brain screaming the five-year-old version of “What the fuck’s happening?” If I had been more prepared for what I was going to see, I think I might have processed it differently.

Reading Tarantino’s account was definitely validating, even vindicating. I mean, I like scary movies, but not like that.

Knowing the rules helps shape our expectations. Knowing the rules might not take the scare out completely, but not knowing them can be devastating. Not even my in-depth study of the rules in the meantime has made me feel comfortable enough to see Bambi again.

What’s your favorite scary movie?

Happy Halloween!

Thank you for reading,

-royc.

October 16, 2024

The Acker Ethic

I’ve been thinking about allusion, quotation, and sampling in the broadest possible terms. It’s led me both deep into the self and what makes up consciousness and way, way outward into what constitutes reality. Some of the concerns are epistemological. That is, how we know what we know. And some are ontological. That is, how we be who we be. I’m zooming in and zooming out to find the limits of the concepts of reference and recycling.

Before we get to Kathy Acker’s writing practices, let’s start with brief survey of other perspectives:

In his book 2012: The Return of Quetzalcoatl (Tarcher, 2006), Daniel Pinchbeck extends Heisenberg’s idea that observation influences the observed into a Hegelian word-view that consciousness constitutes the core of reality, as if the physical world and our perception of it are merely two sides of the same phenomenon. Taken wholesale, it’s not quite solipsism, but it’s close. The act of writing blurs the lines even further.

In his introduction to Cicero’s On the Good Life, Michael Grant writes,

Cicero strongly believed that the universe is governed by a divine plan... When he looked round him at the marvels of the cosmos he could only conclude, adopting the “argument from design,” that they must be of divine origin. He was happy to adopt this form of religion, purified and illuminated by the knowledge of nature, because it justified his confidence in human beings, which was based, as has been seen, on the conviction that the mind or soul of each individual person is a reflection, indeed a part, of the divine mind.

Cicero held a distributed view of religion, each of us representing one aspect of the divine. Evoking both Immanual Kant and Jakob Johann von Uexküll in her book Ecstatic Worlds (MIT Press, 2017), Janine Marchessault writes,

Building upon Kant’s philosophy, Uexküll maintained that the world of every living organism on the earth is different from that of every other organism because of the uniqueness of its sensory organs and its environment; each creature inhabits a unique environment that is uniquely experienced. The world is thus made up of multiple, overlapping environments.

So, on one side, we’re each the eyes of the divine, but if each of us sees ourselves as the center of our own universe, then we all live in universes made up of our own observations and experiences. It’s its own many-worlds theory, even if just by a slight shift in point of view. For the sake of the discussion at hand, let’s adopt the theory—even if only by analogy. When we write, we take on a point of view, make observations, and relay experiences. Now, what if we step outside of ourselves and borrow points of view, observations, and experiences from others?

“I’m not an enclosed or self-sufficient being.” — Colette Peignot,

channeled by Kathy Acker in My Mother: Demonology

Kathy Acker in London in the late 1980s. [photo by Mark Baker]

Kathy Acker in London in the late 1980s. [photo by Mark Baker]Experimental writer and all around badass Kathy Acker would do just that. Her writing practice included variations on William Burroughs and Brion Gysin’s cut-up method, parody, pastiche, postmodernism, and forms that flirted with plagiarism. During a visit to RE/Search headquarters in 2012, her friend and ex-lover McKenzie Wark told V. Vale, “She would just read a book and re-write it. Sitting cross-legged on the floor, she would just read Treasure Island and re-write it. You don’t wait for inspiration, you just get going” (italics in original). Wark met Acker in July of 1995 when she was visiting Sydney, Australia. The next year, Wark visited her in San Francisco. Their brief relationship, which largely existed between those two meetings, is chronicled via their collected emails in I’m Very Into You: Correspondence 1995–1996 (Semiotext(e), 2015).

Like everyone who came in contact with her, Wark was irrevocably inspired. Acker left no stone unthrown, no line uncrossed. Wark continues, “When I met her, she had three books… And she was writing Pussy, King of the Pirates (Grove Press, 1996). It’s one-third Treasure Island and two-thirds something else, and she would just read these three books and, almost at random, re-write them.” Acker explained her methods in a1990 interview with Sylvére Lotringer:

I placed very direct autobiographical, just diary material, right next to fake diary material. I tried to figure out who I wasn’t and I went to texts of murderesses. I just changed them into the first person, really not caring if the writing was good or bad, and put the fake first person text next to the true first person. And then continue to see what would happen. I used pre-Freudian texts because I didn’t want to deal with Freudian jargon. It was a very naive experiment at first. I was experimenting about identity in terms of language.

Like a mash-up artist or hip-hop producer, Acker would sample other texts, recontextualizing them among her own. It wasn’t a shortcut, it was an experiment, an exploration outside herself. Marchessault adds, “The environment described by Uexküll is defined by a multiplicity of overlapping subjective experiences of time.” Acker continues,

What a writer does, in 19th century terms, is that he takes a certain amount of experience and he “represents” that material. What I’m doing is simply taking text to be the same as the world, to be equal to non-text, in fact to be more real than non-text, and start representing text.

Acker was not plagiarizing or imitating but representing another’s text. It’s not mimésis or mimicry in the Aristotelian sense. A symbol on a map represents a particular building or destination, but it isn’t imitating that building or destination. As Acker added, “I didn’t copy it. I didn’t say it was mine.” She was smuggling in other points of view, other observations, other experiences, others. Hers was a proto-punk act of creative destruction.

In her Acker biography, After Kathy Acker, Chris Kraus writes, “But then again, didn’t she do what all writers must do? Create a position from which to write?” Architect of a different vector of bomb, one designed to level the pedestals of the literary canon, Acker could have proclaimed, “Now I am become life, creator of worlds.”

These are not the cover of The Grand Allusion.

These are not the cover of The Grand Allusion.The above are notes for a bit in my book-in-progress, The Grand Allusion (forthcoming from Repeater Books). I am admittedly reaching past my understanding of these concepts, so I have to say thanks to McKenzie Wark and Steven Shaviro for their guidance on this topic.

And thank you for reading,

-royc.

Bibliography:

Kathy Acker, Hannibal Lecter, My Father, New York: Semiotext(e), 1991.

Kathy Acker & McKenzie Wark, I’m Very Into You: Correspondence 1995–1996, New York: Semiotext(e), 2015.

Kathy Acker, My Mother: Demonology, New York: Grove Press, 1994.

Kathy Acker, Pussy, King of the Pirates, New York: Grove Press, 1996.

Aristotle, Poetics, New York: Penguin Classics, 1996.

Michael Grant, Introduction, in Cicero, On the Good Life, New York: Penguin Books, 1971, 8.

Chris Kraus, After Kathy Acker: A Biography, New York: Semiotext(e), 2017.

Janine Marchessault, Ecstatic Worlds: Media, Utopias, Ecologies, Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2017.

Steven Shaviro, Doom Patrols: A Theoretical Fiction About Postmodernism, San Francisco, CA: Serpent’s Tail, 1996.

V. Vale, A Visit from McKenzie Wark, San Francisco, CA: RE/Search Publications, 2014, 21.

McKenzie Wark, Philosophy for Spiders: On the Low Theory of Kathy Acker, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2021.

October 2, 2024

When Everyone's a Winner

The dictum, “In the future, everyone will be famous for 15 minutes,” for which several sources have claimed credit, is widely attributed to Andy Warhol. Regardless of who first said it, those 15 minutes of the future are the popular origins of the long tail of fame. Though the phrase has been around since the late 1960s, its proposed future is here.

In his 1991 essay, “Pop Stars? Nein Danke!” Scottish recording artist Momus updates Warhol’s supposed phrase to say that in the future, everyone would be famous for 15 people, writing about the computer, “We now have a democratic technology, a technology which can help us all to produce and consume the new, ‘unpopular’ pop musics, each perfectly customized to our elective cults.” In Small Pieces Loosely Joined, David Weinberger’s 2002 book, he notes about bloggers, content creators, comment posters, and podcasters: “They are famous. They are celebrities. But only within a circle of a few hundred people.” He goes on to say that in the ever-splintering future, they will be famous to ever-fewer people, and—echoing Momus—that in the future provided by the internet, everyone will be famous for 15 people. Democratizing the medium means a dwindling of the fame that medium can support.

Around the turn of the millennium, the long tail, the internet-enabled power law that allows for millions of products to be sold regardless of shelf space, reconfigured not only how culture is consumed but also how it is created. It’s since gotten so long and so thick that there’s not much left in the big head. As the online market supports a wider and wider variety of cultural artifacts with less and less depth of interest, they each serve ever-smaller audiences. Even when a hit garners widespread attention, there are still more and more of us farther down the tail, each in our own little worlds.

In his 1996 memoir, A Year with Swollen Appendices, Brian Eno proposes the idea of edge culture, which is based on the premise that “If you abandon the idea that culture has a single center, and imagine that there is instead a network of active nodes, which may or may not be included in a particular journey across the field, you also abandon the idea that those nodes have absolute value. Their value changes according to which story they’re included in, and how prominently.” Eno’s edge culture is based on Joel Garreau’s idea of edge cities, which describes the center of urban life drifting out of the square and to the edges of town. The lengthening and thickening of the long tail plot our media culture as it moves from the shared center to the individuals on the edges, from one big story to infinite smaller ones.

Now, what does such splintering do to the economics of creating culture?

"The lottery sucks! I only won 17 bucks!" — Rioter in Bruce Almighty (2003).

"The lottery sucks! I only won 17 bucks!" — Rioter in Bruce Almighty (2003).Bruce Nolan, played by Jim Carrey in the 2003 movie, Bruce Almighty, is a man unimpressed with the way God is handling human affairs. In response, God lets him have a shot at it. One of the many aspects of the job that Bruce quickly mishandles is answering prayers. His head is flooded with so many, he can't even think. He sets up an email system to handle the flow, but the influx overwhelms his inbox. As a solution to that, he implements an autoresponder to send back a message that simply reads, “Yes” to every request.

Many of the incoming prayers are pleas to win the lottery. His wife’s sister Debbie hits it. “There were like 433 thousand other winners,” his wife Grace explains, “so it only paid out 17 dollars. Can you believe the odds of that?” Subject to Bruce’s automated email system, everyone who asked for a winning ticket got one. Out of the millions on offer, everyone who prayed to God to win the lottery won 17 dollars.

About 15 dollars. That’s what you get when you’re famous for 15 people for 15 minutes. That's what you get when everyone’s a winner.

"It’s all become marketing and we want to win because we’re lonely and empty and scared and we’re led to believe winning will change all that. But there is no winning."

— Charlie Kaufman, BAFTA, 2011

The mainstream isn’t the monolith it once was. It’s a relatively small slice of the total culture now, markedly smaller than it was at the end of last century. For better or worse, the internet has democratized the culture-creating and distributing processes we used to privilege (e.g., writing, music, comedy, filmmaking, etc.), and it’s brought along new forms in its image. Since the long tail took hold around the turn of the millennium, the edge culture of the internet has splintered even further via social media and mobile devices. Anyone can now create content and be famous for 15 people for 15 minutes—and earn 15 dollars for their efforts.

The Medium Picture

The Medium PictureThis repost from the archives is an excerpt from my book, The Medium Picture (coming out next year from the UGA Press). Here's the brief overview:

The ever-evolving ways that we interact with each other, our world, and our selves through technology is a topic as worn as the devices we clutch and carry everyday. How did we get here? Drawing from the disciplines of media ecology and media archaeology, as well as bringing fresh perspectives from subcultures of music and skateboarding, the book illuminates aspects of technological mediation that have been overlooked along the way. With a Foreword by Andrew McLuhan, The Medium Picture shows how immersion in unmoored technologies of connectivity finds us in a world of pure media and redefines who we are, how we are, and what we will be.

About The Medium Picture, William Gibson says,

“Very much looking forward to reading new Christopher, exactly the sort of contemporary cultural analysis to yield unnerving flashes of the future.”

And Paul Levinson adds,

“Brilliant, pathbreaking, palpable insights… Worthy of McLuhan.”

Be on the lookout…

As always, thank you for reading, responding, subscribing, and sharing,

-royc.

September 22, 2024

Awful Ever After

I woke up in the middle of a curve. These days feel like more and more taking a turn too hard and trying to regain your bearings. Sometimes the centrifugal realizations aren’t even new, but they get recontextualized repeatedly around that curve, given new information, knowledge, or experience.

For example, I realized a while ago that the idea of cool isn’t a stable phenomenon. Everything that used to be cool is now remade, rebooted, recycled—when it isn’t rejected outright. That realization is not new, but it has a new relevance when the cool that is contested is your own. When your own idea of cool slips from the zeitgeist, it’s a reckoning. It’s one thing to hold an idea like that out at an academic length, and wholly another to be slammed right up against it.

“Here there is a tabula rasa of indifference. It is like attending a family gathering and realizing you are old, and the new generation does not give a fuck about you or your experience.” – from Tade Thomson’s Rosewater

There’s a time just before your own that remains relevant and influential whether you acknowledge it or not. We tend to compress the time before us right up against our first memories, like a wave against a wall, forgetting the ocean of events swelling behind it. But no one cares what was cool before they were born. An abject lack of history makes it all fair game. Some things that happened “in the ‘90s” actually happened in the ‘60s, ‘70s, or ‘80s. No one really cares when.

We tend to compress the time before us right up against our first memories, like a wave against a wall, forgetting the ocean of events swelling behind it.

In addition, if you’re waiting to get back to that lovely little time—accurate or not, real or imagined—as if something will change and we’ll all return to some former state of comfort or ease, you can stop waiting: We’re never going back—not to the time before a certain presidency, not to the time before COVID-19, not to the time before 9/11, not even the time before social media and smartphones.

For example, The technical infrastructure of television is unrecognizable compared to what it was during its debut in our homes, but it’s still here, our window to the wider world. The telephone has also been wholly reconfigured, but it’s still here, always with us. We can’t cut the cord. Once we adopt these things, they don’t go away.

When I look up from my phone and see everyone else walking around staring at their phones, I always think about us looking back on this time. “Remember when everyone used to walk around looking at their phones? Ah, the Good Ol’ Days!” But can you imagine the next thing being better? Wearables and implants aren’t better to me than just being able to leave the damn devices at home. That’s never going to happen again.

So, are we really trying to stay connected or are we just trying to stay distracted? Maybe the curve never straightens back out. Maybe this is the new normal: chronic dizziness from rounding the grate in the drain, over and over, amen.

New clipping. Video!To take the sting out of my Sunday morning musing, here’s a new video from my dudes clipping.! “Run It” is from the hip-hop vs cyberpunk project, Dead Channel Sky, due out next March from Sub Pop (more on that soon). Check it out!

Thank you for reading, responding, and sharing,

-royc.

September 12, 2024

BOOGIE DOWN PREDICTIONS is Two!

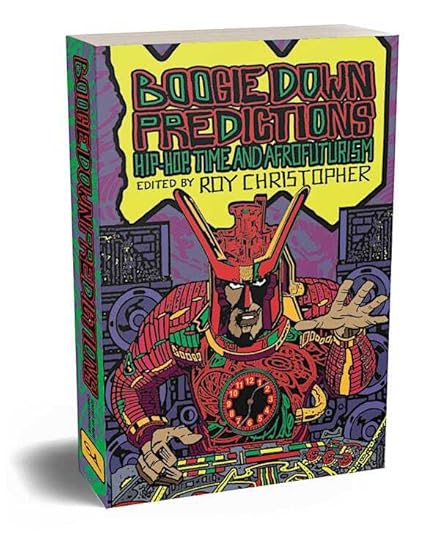

Hey, it’s been two years since Boogie Down Predictions dropped!

The great Greg Tate called it, “The bomb diggety!” and Dan Charnas says, “Roy Christopher has given us more than a book; it’s a cypher and everyone involved brought bars.”

Here’s a bit more about how it came together and what it’s been up to since. Read on!

Cover art by Savage Pencil.

Cover art by Savage Pencil.While I was writing my book Dead Precedents: How Hip-Hop Defines the Future (Repeater Books, 2019), I gathered up some friends, and we put together an edited collection as sort of a companion to Dead Precedents. Time was one of the aspects of both hip-hop and science fiction that I didn’t get to talk about much in that book, so I started asking around. I found many other writers, scholars, theorists, DJs, and emcees, as interested in the intersection of hip-hop and time as I was. I had three solid pieces at the end of the first day! As I continued contacting people and collecting essays, I got more and more excited about the book. Boogie Down Predictions: Hip-Hop, Time, and Afrofuturism is a quest to understand the connections between time, representation, and identity within hip-hop culture, as well as what that means for the culture at large.

Crazy respect to Jeff Chang for the kind words.

Crazy respect to Jeff Chang for the kind words.Here’s my Preface to Boogie Down Predictions:

That Banging is the Rhythm.That Banging is the Beat.

“It’s harder to imagine the past that went away than it is to imagine the future.”

— William Gibson

“What can you do? You can’t turn back the clock.That’s why you keep on moving, and you don’t stop.”— Babbletron, “The Clock Song”

“The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.” So begins the prologue to L. P. Hartley’s 1953 novel The Go-Between. Time is as inescapable as it is impossible to conceive. Technology tries to tame it, chopping it into discrete bits and arranging them in manageable lines: the alphabet, the printing press, the clock, the internet. Marshal McLuhan once wrote, “Just as work began with the division of labor, duration begins with the division of time, and especially with those subdivisions by which mechanical clocks impose uniform succession on the time sense.” From Frederick Taylor’s studies of time and scientific management to the division of labor of Taylor and Henry Ford, the inventors of modern industrialization, division and duration are operative terms for the technologies of time.

If you were asked to name the salient elements that define hip-hop music, sampling would be among the first things to come to mind. If you’re reading this, you know it started manually with fingers finessing black vinyl, chopping and stretching tones on two turntables. The manual mixing of recorded sounds by DJs allows them to, as Naut Humon puts it, “Manipulate time with your hands!” Reconfigured and recontextualized notes lift hip-hop out of the linear, tying it equally to both forgotten pasts and lost futures. Because of sampling, hip-hop’s manipulation of sound is also its manipulation of time. More so than any other musical genre, hip- hop toys with temporality.

Dart Adams knows the time.

Dart Adams knows the time.Further stretching this frame, the aesthetic of hip-hop’s early days feels like possible futures. Way before Tupac and Dr. Dre danced in the desert and Chuck D was doorman to the Terrordome, things were always already going down in the Boogie Down Bronx. The post-apocalyptic scene there in the early 1970s, the repurposing of left-behind technology, the hand-styled hieroglyphics on every building wall, and the gyrating dance moves: an entire culture assembled from the freshest of what was available at hand.

Whereas the dominant (read: “European, white, male”) culture of the 20th century regularly pictured the next century through stories and inventions, that hasn’t been the case as much among those same folks so far in the 21st. Even as far back as Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward, which viewed its 1887 present from a fictional year-2000 wherein the United States had evolved into a technologically enabled, Marxist utopia. Twenty-first century tales that venture to look that far ahead rarely find such positive results, especially where technology is concerned.

With that said, it would be remiss to talk about hip-hop and its tumultuous relationship with time without mentioning Afrofuturism. “Afrofuturism is me, us [...] is black people seeing ourselves in the future,” says Janelle Monáe, whose futuristic R&B concept records The ArchAndroid, The Electric Lady, and Dirty Computer imagine android allegories in alternative futures. Afrofuturism addresses the neglect of the Black Diaspora not only historically but also in science-fiction visions of the future.

#1 New Release on Amazon, y’all!

#1 New Release on Amazon, y’all!Through its relationship with time and its technological manipulation thereof, hip-hop also invites us to view different vantages of the future. Just as it recycles and revises the past, hip-hop also invites us to re-imagine the future. As we will see, these re-imaginings are far from apolitical. William Gibson is fond of saying that the future is already here, it’s just not evenly distributed yet. Any reader of history knows that the past isn’t evenly distributed either. Drawing different conclusions from the past and picturing a future that is different from the present are the very essence of resistance.

“Hip-hop is imprisoned within digital tools like the rest of us,” writes the technologist and musician Jaron Lanier. “But at least it bangs fiercely against the walls of its confinement,” That banging is the rhythm. That banging is the beat. That banging is the celebration of days past and the longing for better ones to come. As Kodwo Eshun writes in his 2003 essay, “Further Considerations on Afrofuturism,” reprinted herein,

Afrofuturism approaches contemporary music as an intertext of recurring literary quotations that may be cited and used as statements capable of imaginatively reordering chronology and fantasizing history. Social reality and science fiction create feedback between each other within the same phrase.

Though this dialog between social reality and its fictional futures has occurred since we started telling stories, mechanical and digital reproduction has made the exchange easier and much wider spread. The division of sampling and duration of remixing keeps the feedback flowing in time. As Jacques Attali puts it, “Our music foretells our future. Let us lend it an ear.”

Charles Mudede’s Book NookOur old friend Charles Mudede Recommended Boogie Down Predictions as a Christmas gift, pointing out a few of the features of the text as well as a special appearance by a cat.

Me and Ytasha Womack talking hip-hop and Afrofuturism at Volumes Books in Chicago. [Photo by Shannon Keane.]BDP in Chicago!

Me and Ytasha Womack talking hip-hop and Afrofuturism at Volumes Books in Chicago. [Photo by Shannon Keane.]BDP in Chicago!Ytasha Womack, who wrote the Introduction, and I did an event for Boogie Down Predictions this July at Volumes Books in Chicago, and you missed a treat if you weren’t there.

BDP at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago. [photo by Ytasha Womack]

BDP at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago. [photo by Ytasha Womack]

BDP in Houston!

BDP in Houston!On a Sunday afternoon last year at Houston Public Library's African American History Research Center at the Gregory Campus, the poet, artist, activist, and teacher Deborah D.E.E.P. Mouton and I discussed hip-hop culture, myth-making, and Afrofuturism. Mouton’s memoir, Black Chameleon: Memory, Womanhood, and Myth, (Henry Holt, 2023), explores the use of modern mythology as a path to social commentary. Thanks to Deep and James Stancil (organizer and moderator), it was a raucous talk about all of the above.

Me and Deborah D.E.E.P. Mouton at the Houston Public Library's African American History Research Center. [photo by Lily Brewer]Thank you!

Me and Deborah D.E.E.P. Mouton at the Houston Public Library's African American History Research Center. [photo by Lily Brewer]Thank you!Many thanks to Jamie Sutcliffe and Mark Pilkington at Strange Attractor Press for their support and enthusiasm, Dominic Rafferty for the stellar layouts, and Savage Pencil for the dopest cover. Thanks to those who contributed words, images, blurbs, and direction, those who wished us well, and those who didn’t. Thanks to Rebecca and Kimberly at Volumes Books for their continued support, to Ytasha Womack and Deep Mouton for their support, to James Stancil and all at Intellect U Well, Inc., and to you for checking it out!

BDP at Rough Trade in the UK.

BDP at Rough Trade in the UK.And if you don’t have a copy, do yourself a favor!

Thank you for reading, responding, subscribing, and sharing!

We in this,

-royc.

September 3, 2024

The Grand Allusion

I’ve been studying and writing about allusions since Matt McGlone pointed me toward them when I took his graduate class on metaphor at the University of Texas at Austin. I ended up doing my doctoral dissertation on the use of allusion in rap lyrics, and I’ve wanted to expand the idea ever since.

Sometimes an allusion is not necessarily an homage. Sometimes it’s just “inspiration.” Deborah Harry in 1976, and Margot Robbie as Harley Quinn in 2016.

Sometimes an allusion is not necessarily an homage. Sometimes it’s just “inspiration.” Deborah Harry in 1976, and Margot Robbie as Harley Quinn in 2016.Well, I just signed on to write a book about them called The Grand Allusion for Repeater Books! To commemorate the announcement, I thought I'd repost my early thoughts on the idea.

There are a lot of tenuously connected ideas bouncing around in what passes for an overview below, so thank you for enduring my thinking aloud. I'll be sorting these thoughts out further for the book.

Read on!

MedianesiaOn his spoken-word album Bomb the Womb (Gang of Seven) from 30 years ago, Hugh Brown Shü does a great bit about it being 1992, and everything seeming familiar. “What has been will be again,” reads Ecclesiastes 1:9. “What has been done will be done again; there is nothing new under the sun.” That old familiar feeling has been around longer than we’d like to admit, but how do make sense of things that seem familiar but really aren’t?

The first time I heard “The Pursuit of Happiness” by Kid Cudi (2009), I felt like something was a bit off about it. I felt like it had originally be sung by a woman, and he’d just jacked the chorus for the hook. I distinctly remembered the vocals being sung by a woman but also that they were mechanically looped, sampled, or manipulated in some way.

Upon further investigation I found that the song was indeed originally Kid Cudi’s, but that Lissie had done a cover version of it. Her version is featured in the Girl/Chocolate skateboard video Pretty Sweet (2012), which I have watched many times. Even further digging found the true cause of my confusion: A sample of the Lissie version forms the hook of ScHoolboy Q’s song with A$AP Rocky, “Hands on the Wheel.” This last was the version I had in my head and the source of my confusion.

I use this rather tame example to show how easy it is to be unsure about the source of something that we feel like we know. It’s a form of medianesia where our entertainment messes with our memories. The phenomenon plays out in many other contexts as well.

Visualize Allusions Dave Vanian of The Damned on the cover of Slash #1, May 1977, and Playboi Carti on the cover of his record Whole Lotta Red, 2020.

Dave Vanian of The Damned on the cover of Slash #1, May 1977, and Playboi Carti on the cover of his record Whole Lotta Red, 2020.The cover art for Playboi Carti’s 2020 record, Whole Lotta Red (AWGE/Interscope) knocks off the lo-fi aesthetic of classic punk magazine Slash. This isn’t the first time Carti’s visual aesthetic has paid homage to punk.

Playboi Carti Die Lit (2018).

Playboi Carti Die Lit (2018).The stage-diving photo on the cover of his 2018 record, Die Lit (AWGE/Interscope), recalls a similar SST promo photo of HR of Bad Brains, who was notorious for doing backflips on stage. It’s closer to Edward Colver’s classic 1981 Wasted Youth live shot, which appeared on the back of their Reagan’s In LP (ICI Productions).

Wasted Youth Regan’s In (1981). Photo by Ed Colver.

Wasted Youth Regan’s In (1981). Photo by Ed Colver.Such allusions are everywhere in our media. They’re also prevalent in human interpersonal communication. The example I always cite for this comes from Adbusters Magazine founder Kalle Lasn. In his 1999 book Culture Jam, Lasn describes a scene in which two people are embarking on a road trip and speak to each other along the way using only quotations from movies. Based on this idea and the rampant branding and advertising covering any surface upon which an eye may light, Lasn argues that our culture has inducted us into a cult: “By consensus, cult members speak a kind of corporate Esperanto: words and ideas sucked up from TV and advertising.” Indeed, we quote television shows, allude to fictional characters and situations, and repeat song lyrics and slogans in everyday conversations. Lasn argues, “We have been recruited into roles and behavior patterns we did not consciously choose” (emphasis in original).

Social SteganographyLasn writes about this scenario as if it is a nightmare, but to many of us, this sounds not only familiar but also fun. Our media is so saturated with allusions to other media that we scarcely think about them. A viewing of any single episode of popular television shows Family Guy, South Park, or Robot Chicken yields allusions to any number of artifacts and cultural detritus past. Their meaning relies in large part on the catching and interpreting of cultural allusions, on their audiences sharing the same mediated memories, the same mediated experiences.

In an article from 2015, Devin Blake uses comedy as an example. Pointing to the well-established fact that we no longer define ourselves by what we produce but by what we consume, he marks the rise of what he calls “consumer comedy.” That is, comedy that references other media in order to pack its punchlines. “A lot of what happens in late night TV, for example,” he writes, “seems to involve things that we consume, namely other media like TV shows, movies, and music.” The added knowledge of an allusion is crucial for comedy in that if the audience doesn’t catch a reference, they won’t get the joke. Blake adds the critical insight: “A world of comedy-for-consumers is different than one filled with comedy-for-producers.” The consumption of information is not tethered to the physical world in the way that the production of material goods is.

Marshall McLuhan would frame these media allusions in Gestalt psychology terms as figure and ground. The figure being the overt reference—visual, verbal, or otherwise—and the ground being the invisible referent—the original image or text. “The figure is what appears and the ground is always subliminal,” he wrote. In the visual allusions above for instance, the figure is what you see, and the ground is the source material, the knowledge you have that you’ve seen the thing before, that old familiar feeling. The figure is the artifact at hand, and the ground is the historical context it’s indexing.

Deborah Harry had a Slash cover, too. Issue #5, October 1977.

Deborah Harry had a Slash cover, too. Issue #5, October 1977.So widespread is the use of allusion in our media that it has become its own cultural form. Following allusions on a path through media provides a unique way to understand contemporary mediated culture. Because allusion relies on shared media memories, exploring its use and function in media and conversation helps answer questions of how such mediated messages are stored, conceived, retrieved, and received.

Allusive tactics are not limited to television shows, movies, music, and conversations. Users employ them on social media as a form of social steganography. That is, hiding encoded messages where no one is likely to be looking for them: right out in the open. In one study, a teen user has problems with her mother commenting on her status updates. She finds it an invasion of her privacy, and her mom's eagerness to intervene squelches the online conversations she has with her friends. When she broke up with her boyfriend, she wanted to express her feelings to her friends but without alarming her mother. Instead of posting her feelings directly, she posted lyrics from “Always Look on the Bright Side of Life.” Not knowing the allusion, her mom thought she was having a good day. Knowing that the song is from the 1979 Monty Python movie, Life of Brian, and that it is sung while the characters are being crucified, her friends knew that all was not well and texted her to find out what was going on.

Flowers for QAnon Howling on hallowed ground: Jake Angeli a.k.a. the QAnon Shaman.

Howling on hallowed ground: Jake Angeli a.k.a. the QAnon Shaman.Social steganography is not always so innocuous. Media allusions are arguably more vital on social media where memes are the currency exchanged. Conspiracy theories are spread online through shared texts as their adherents rally around allusions to those texts. The hidden knowledge allows these groups to communicate with each other out in the open without alarming others or stirring up ire or opposition. So-called “dog whistles,” these allusions are shibboleths shared by members and ignored by others. QAnon has largely shared references to their own rumors and accusations, but other texts like William Luther Pierce's The Turner Diaries and the Luther Blissett Project’s novel Q are also touchstones. On the possible connections between the Q of QAnon and the Q novel, Luther Blissett member Wu Ming 1 says, “Once a novel, or a song, or any work of art is in the world out there, you can’t prevent people from citing it, quoting it, or making references to it.”

If we’re all watching broadcast television, we’re all seeing the same shows. If we’re all on the same social network, no two of us are seeing the same thing. The limited access to content via broadcast media used to unite us. Now we're only loosely united via the platform, and the platform itself doesn't matter. What matters is ephemeral and esoteric knowledge, knowing the memes, getting the references, catching the allusions. The references are stronger than their original media vessels. As less and less of us share the ground of each figure, the latter outmodes the former as it shrinks. Whether images from other media or quotations from a text, the allusions themselves outmode the vehicles that carry them.

As always, thank you for reading, responding, and sharing.

I appreciate you,

-royc.

August 23, 2024

About Time

The time-travel trope never seems to wear thin. Even a bad time-travel story has its moments. Madeleine L'Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time (1962) was the first full-length novel I ever read, and something about it latched onto my sixth-grade imagination and hasn’t let go. Several of my favorite all-time stories involve time travel to some extent.

“Part of the fascination of time travel concerns the stark paradoxes that threaten as soon as travel into the past is considered,” writes the theoretical physicist Paul Davies in his 2001 book How to Build a Time Machine. “Perhaps causal loops can be made self-consistent. Perhaps reality consists of multiple universes.” These thought experiments are rife with unanswered and unanswerable questions, which are the very stuff of great stories.

Though the concept started in religion, it was popularized by H.G. Wells’ 1895 novella, The Time Machine. Mechanical time travel has remained a standard in science fiction ever since. According to James Gleick’s Time Travel: A History (Pantheon, 2016), H.G. Wells wasn’t trying to explain anything. He was just trying to come up with a “plausible-sounding plot device” for a story.

There are the plausible-sounding back-in-time explorations like the Back to the Future franchise (1985-1990), and the time-loop lunacy of Groundhog Day (1993), as well as the outright hysterics of Hot Tub Time Machine (2010) and Hot Tub Time Machine 2 (2015), but they’re not all winners. Project Almanac (2015) illustrates the inherent paradoxes of temporal travel and their intrigue while still being only an okay movie, but it falters in spite of the time travel rather than because of it. 2009’s Triangle also loops time into a muddy and often confusing story. Time travel can be such a cumbersome cognitive load that it’s difficult to get right in a story with much else going on and even harder to make feel real. And then of course there’s Justin Smith Ruiu’s ChronoSwoop app.

With that said, here are twenty one of my favorite stories that feature time travel in one form or another.

“Time is a game

played beautifully

by children.”

— Heraclitus, Fragment 79

Jack Purvis, Malcolm Dixon, Tiny Ross, David Rappaport, and Craig Warnock in Time Bandits (1981).Time Bandits

Jack Purvis, Malcolm Dixon, Tiny Ross, David Rappaport, and Craig Warnock in Time Bandits (1981).Time BanditsThe story that best captures my childhood fascination with adventure—and directly follows the feeling I got from A Wrinkle in Time—is Terry Gilliam’s Time Bandits (1981). Reluctant to go to bed, a young boy (Kevin) is soon whisked away by a band of tiny time-traveling thieves who’ve stolen a map of the universe from the Supreme Being. Through portals marked on the map, they bounce through time, stealing whatever they can along the way. Though young Kevin has been longing for adventure, soon all he wants is to get back home.

David Sullivan and Shane Carruth in Primer (2004).Primer

David Sullivan and Shane Carruth in Primer (2004).PrimerWritten, directed, produced, edited, and scored by Shane Carruth, who also costars, Primer (2004) is a D.I.Y. garage sci-fi thriller. It got a lot of attention upon its release in 2004 for its bargain budget, but it’s an achievement at any price. Friends and engineering colleagues Aaron (Carruth) and Abe (David Sullivan) build a box that turns out to enable them to travel back in time. The fact that they stumble upon this ability and then use it for fairly frivolous means (stock trades) doesn’t dull the chronologically jumbled plot or the inevitable unraveling of their relationship.

Cristin Milioti and Andy Samberg in Palm Springs (2020).Palm Springs

Cristin Milioti and Andy Samberg in Palm Springs (2020).Palm SpringsRight when you thought the time-loop concept was past tense, it comes back around again, just as renewed and refreshed as it is recurring. A destination wedding is the setting for the temporal hijinks in Max Barbakow’s Palm Springs (2020). Like the Harlequin in Harlan Ellison’s “‘Repent, Harlequin!’ Said the Ticktockman,” who deliberately knocks a clockwork world out of its scheduled whack, Nyles (Andy Samberg) breaks everyone out of their routines and shows them a different way through the wedding day, over and over again, until Roy (J.K. Simmons) and Sarah (Cristin Milioti), er, shake things up for him.

Karra Elejalde and Bárbara Goenaga in Timecrimes (2007).Timecrimes

Karra Elejalde and Bárbara Goenaga in Timecrimes (2007).Timecrimes Timecrimes (Los Cronocrímenes; 2007) capitalizes on its causal loops and suspenseful twists rather than wasting them. The film contains exactly four actors, and its action takes place over the course of about an hour and a half. In its handling of causality, Timecrimes is somewhere between Primer and the popular Back to the Future franchise of the 1980s, both of which feature extensive backwards time travel. Like Primer, which uses time travel as the pretext for the study of larger issues, Timecrimes evokes themes of voyeurism and ethics in addition to its time-looping structure and the subsequent questions of causality. [See my full write-up in the Econo Clash Review.]

Safety Not Guaranteed

Safety Not GuaranteedInspired by a classified ad that ran in Backwoods Home Magazine in 1997, Safety Not Guaranteed (2012) shows how the possibilities of time travel test our loyalties. All of the film’s characters are faced with decision points that didn’t exist before but that point back to issues they should’ve already processed: one applying for medical school, one tracking down his high-school flame, one seemingly above everything anyway. It’s a surprisingly poignant and effective movie.

How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe

How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional UniverseThe narrator in Charles Yu’s How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe (Vintage, 2010) is a time-machine mechanic. Charles (the narrator has the same name as the author) travels around in his TM-31 Recreational Time Travel Device, alone save his AI supervisor Phil, his onboard computer TAMMY, and his imaginary dog Ed. His mom is stuck in a time-loop, and his dad—inventor of the TM-31—is missing. That premise and those few details unfold into some interesting possibilities and wild predicaments.

Robert Pattinson and John David Washington in Tenet (2020).Tenet

Robert Pattinson and John David Washington in Tenet (2020).Tenet Before Tenet (2021), the writer and director Christopher Nolan was often criticized for being all head and no heart, but when he ventures too far into love (e.g., Inception and Interstellar), he falters. With Tenet, Nolan seems to stay with his strengths, one of those being the technical intricacies of time travel. Here it’s not so much time travel as we think of it but reversed entropy. So, within this ontology, if one wants to go back in time, one must travel through that piece of time backwards (i.e., you can’t blink back to last Tuesday; you have to go backwards through all the days since then to get there). This yields unique results and finds Nolan at the peak of his powers. Though someone described Tenet as “a puzzle box with nothing inside,” I say it’s well worth the puzzlin’.

The tangled timelines of Lauren Beukes’ The Shining Girls (2013).The Shining Girls

The tangled timelines of Lauren Beukes’ The Shining Girls (2013).The Shining Girls“The problem with snapshots,” Kirby Mazrachi thinks, “is that they replace actual memories. You lock down the moment and it becomes all there is of it.” Kirby is one of the girls in The Shining Girls by Lauren Beukes (Mulholland Books, 2013), a disturbingly beguiling novel that is now an Apple TV series in which Elisabeth Moss plays Kirby. Beukes’ easily digestible prose and gleefully nagging narrative betray a convoluted timeline and staggering depth of research. Drifter Harper Curtis (played in the show by Jamie Bell) quantum leaps from time to time gutting the girls as he goes. The House he squats in his helper, enabling the temporal jaunts. He’s like an inverted Patrick Bateman: no money, all motive. Where Bateman’s stories are told from his point of view in the tones of torture-porn, Harper’s kills are described from the abject horror of the victims. And the victims, who are all strong-willed women with drive and purpose, are only victims at his hand. Otherwise they shine with potential and promise. [Read my full review.]

The babyfaced killer and Jessica Rothe in Happy Death Day 2U (2019).Happy Death Day and Happy Death Day 2U

The babyfaced killer and Jessica Rothe in Happy Death Day 2U (2019).Happy Death Day and Happy Death Day 2UTime-loops don’t get any loopier than this. One of the genius turns in the script for Groundhog Day, written by Danny Rubin and Harold Ramis, was their use of the Kübler-Ross model of the five stages of grief—denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance—as an outline for the loops. Christopher Landon’s Happy Death Day (2017) follows Tree (Jessica Rothe) stumbling through a similar cycle. In its sequel, Happy Death Day 2U (2019), a different person is stuck in the next day, and given her repeated previous experience, Tree steps in to help. And a third Happy Death Day is on the way!

Bruce Willis and Brad Pitt in Terry Gilliam’s 12 Monkeys (1995).12 Monkeys

Bruce Willis and Brad Pitt in Terry Gilliam’s 12 Monkeys (1995).12 MonkeysA core thread of 12 Monkeys is Gaston Bachelard’s Cassandra Complex, in which one is given knowledge of the future, but is unable to convince anyone that the knowledge is true. Inspired by a 1964 French short called La Jetée written and directed by Chris Marker, Terry Gilliam expanded it in 1995 into a feature film starring Bruce Willis, Brad Pitt, Madeline Stowe, and David Morse. James Cole (Willis) is a prisoner in a decimated 2035, having been ravaged by a virus released in 1996. Cole is sent back to 1995 to try and find the source and stop it, but no one believes his claims of imminent doom.

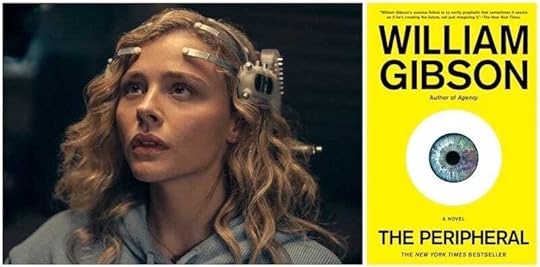

Chloë Grace-Moretz as Flynne Fisher in Scott B. Smith’s adaptation of William Gibson’s The Peripheral (2022).The Peripheral

Chloë Grace-Moretz as Flynne Fisher in Scott B. Smith’s adaptation of William Gibson’s The Peripheral (2022).The PeripheralAfter three novels set in the present, The Peripheral (Putnam, 2014) marked William Gibson’s return to the future. The story projects all of the hallmarks of cyberpunk both into the near future and much further afield. In the far future, what passes for a government has figured out how to open new timelines in the past (a.k.a. “stubs”) just prior to an apocalyptic event. As in 12 Monkeys, they’re trying to figure out what happened and somehow benefit from it, exploiting the past for gain in their present. The television adaptation predictably deviates from the novel, but is also pretty great.

Logograms from Denis Villenueve’s Arrival (2016).The Story of Your Life

Logograms from Denis Villenueve’s Arrival (2016).The Story of Your LifeLeveraging a very strict interpretation of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis (i.e., that the language you speak creates and shapes the reality you live in), the lead scientist in Ted Chiang’s “The Story of Your Life,” Dr. Louise Banks (played by Amy Adams in Denis Villenueve’s 2016 adaptation, Arrival), starts to see the world through the language of the alien visitors, the heptapods. Their language, like their perception of time, is nonlinear, so Banks begins to experience her story, and that of her daughter’s short life, according to the alien linguistic sequence.

Jake Gyllenhaal, director Duncan Jones, and Michelle Monaghan on the set of Source Code (2011).Source Code

Jake Gyllenhaal, director Duncan Jones, and Michelle Monaghan on the set of Source Code (2011).Source CodeWhat happens to one reality when we change another quantum reality’s outcome? Source Code, the system for which the movie is named, uses the last eight minutes of brain activity we all experience upon death to allow a person to experience a different timeline in another, compatible person (via quantum entanglement and “parabolic calculus”; As William Gibson put it, “The people who complain about Source Code not getting quantum whatsit right probably thought Moon was about cloning.”). The idea of the system is to be able to find out what happened just before a catastrophic event (in this case a train bombing), in order to prevent further events from happening (e.g., a massive dirty bomb set for downtown Chicago). Somewhere between brain stimulation and computer simulation, Source Code does its work. But Captain Coulter Stevens (Jake Gyllenhaal) goes in for one last shot at getting everything just right (like Aaron’s repeated runs in Primer) and manages to manipulate more than the system is supposed to allow.

KindredOctavia Butler’s Kindred (Doubleday, 1979) keeps landing her self-styled protagonist (Dana) in the slavery-era of the American South. Though she meets some of her ancestors, her jaunts are unplanned and unpredictable, making this a harrowing read at best. Among many other things, Butler is one of the few authors to address the physical dangers of time travel, as Dana loses an arm during her first temporal trip.

The Hazards of Time TravelCan you be nostalgic for the future? In Joyce Carol Oates’ The Hazards of Time Travel (Ecco Press, 2018), the 17-year-old Adriane Strohl is exiled 80 years in her past (1959), finds another expatriate from their present (2039) and thus begins a time-fraught, dystopian love story.

The Time Traveler’s WifeAudrey Neffenegger’s debut novel, The Time Traveler’s Wife (MacAdam/Cage, 2003), has already been generative enough to yield a movie and a TV series. In another interesting take on temporal logistics, the time-traveler himself, Henry, makes his unexpected jumps due to a genetic disorder.

Donnie DarkoI’ve already written quite a bit about Richard Kelly’s 2001 Halloween myth, Donnie Darko, but it deserves mention for Kelly’s attempt at constructing a comic-book logic of time travel. As somnambulistic as it is, from the very beginning of the movie, something is off, and the traveler is drawn to fix it. He leverages help from unwitting friends, family, and authority figures to correct the anomoly. [Read my full write-up.]

This is How You Lose the Time WarCowritten by Amal El-Mohtar and Max Gladstone, This is How You Lose the Time War (Saga Press, 2020) chronicles the correspondence between two lovers/enemies in a war over the fate of the universe. This epistolary novel is written from the highest vantage point on time and space I’ve ever seen. Its time travel is only due to its scale. It’s difficult to even describe the scope of it, but thankfully the drama between them is relatable to all.

Before I FallLauren Oliver’s Before I Fall (HarperCollins, 2010) puts a YA twist on yet another time-loop story that flows through different stages of purpose and grief. Seventeen-year-old Sam Kingston keeps having to redo February 12, “Cupid's Day,” and has to keep doing it until she gets it right. Sam approaches the repeated day in ways she wouldn’t normally, surprising her friends and family. Like the novel, the movie—starring Zoey Deutch as Sam—is somehow both dark and uplifting.

DetentionJoseph Kahn’s 2011 genre-melting thriller Detention is a wild, wild ride. It’s like The Breakfast Club meets The Faculty meets Back to the Future. Through their school mascot, a giant grizzly bear (the time “machine”), secrets about these misfits in detention, the principle who put them there, and their collective past are revealed. Oh, also one of them is a serial killer.

The Future of Another TimelineOnce it’s possible to repair the past, which revision remains? Bouncing between 2022 and 1992, The Future of Another Timeline (Tor, 2020) by Annalee Newitz explores the very notion of what time and history actually mean when you can travel through one to change the other, yet also how everything is connected to everything else.

“Just as the river where I step

is not the same, and is,

so am I as I am not.”

— Heraclitus, Fragment 81

You Don’t Know What You’ve Got Until You Get It Back.

You Don’t Know What You’ve Got Until You Get It Back.Different Waves, Different Depths, my recent short story collection, includes two time-travel stories. One, which explores the time-loop trap of trauma, is called “Not a Day Goes By,” and the other is a novella-length, go-back-and-fix-things love story called “Fender the Fall,” the tagline of which is You Don’t Know What You’ve Got Until You Get It Back. Those are only two of the nine stories total. Get yours!

Hip-Hop, Time, and Afrofuturism

Hip-Hop, Time, and AfrofuturismSpeaking of time, our collection Boogie Down Predictions covers the many ways that hip-hop tampers with temporality through essays by Omar Akbar (“The Theology of Timing”: Black Consciousness and the Origin of Hip-hop Culture), Juice Aleem (The Free Space/Time Style of Black Wholes), Kodwo Eshun (Further Considerations on Afrofuturism), Erik Steinskog (Preprogramming the Present: The Musical Time Machines of Gabriel Teodros), and Rasheedah Phillips (Constructing a Theory and Practice of Black Quantum Futurism), among many, many others. Check it out!

If I missed your favorite time-travel tale, let me know. Special thanks to Dominic Pettman for his input on this topic.

As always, thank you for reading, responding, and sharing.

Looking forward,

-royc.

July 25, 2024

Strange Exiles: Freestyle Media

I’ve been on the road for the past month, from Jacksonville, Florida to southeast Alabama, over to Austin, Texas, to the hills of middle Tennessee, back to Alabama... I’ve visited with friends I’ve had for decades, my partner of 13 years, and my parents and sister. Getting offline and into the real world with real people sounds as corny as it is simple, but it’s been a great reminder of who we really are. I recommend it.

With that said, here are two of the best interviews I’ve ever been the subject of and a couple of articles from the last few weeks—even a bit of one from several years ago.

Read on!

Freestyle Media

Bram E. Gieben, the host of the Strange Exiles podcast and newsletter and author of The Darkest Timeline (Revol Press, 2024), and I had an hour-long discussion that covers most of my writing, from zines and magazines to blogs and books, and many of my influences along the way.

Here’s a bit from Bram’s introduction:

I’ve been especially looking forward to this interview with media theorist, cultural critic and hip-hop futurist Roy Christopher, author of one of my favourite books of the past decade, Dead Precedents: How Hip-Hop Defines the Future.