Roy Christopher's Blog, page 9

June 13, 2023

One Podcast, Two Synchronicities, and Three Essential Things

One Podcast:

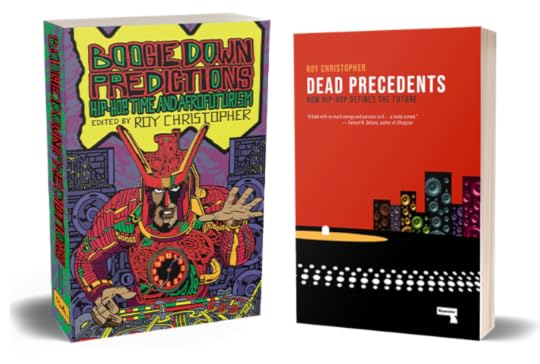

One Podcast:I had the pleasure of talking with Alex Kuchma of the New Books Network podcast about my recent edited collection, Boogie Down Predictions, as well as my books Dead Precedents and The Medium Picture. A student of hip-hop culture like me, Alex is steeped in the stuff. He came to the discussion with sharp questions and insight. It was a pleasure.

Check it out here, on Apple, or wherever you listen to podcasts. Many thanks to Alex and the New Books Network for the interest and the opportunity.

Two Synchronicities:

Two Synchronicities:I was at the Chamblin Uptown Café last week, one of the locations of the great bookstore in Jacksonville, Florida, looking for a Philip Larkin book. After going through all of the poetry section, I looked through their extensive biography section, to no avail. I went by the other location before leaving town, and I checked poetry again, then gave up.

As I was looking through the essay collections, I came across The War Against Cliché by Martin Amis. My friend Will Wiles mentioned this book specifically when Amis passed a couple of weeks ago. Though I'd never read anything by him, he'd been on my list since I read my first Will Self book about 20 years ago (Amis blurbed it). So, I flipped it open to the table of contents, and there’s a chapter on Philip Larkin...

Then, when I got back home, my mom had gotten me a book. It was the lone text in a shopping cart she bought from this bargain store she frequents. They regularly load up whole shopping carts of stuff and sell them for $10 each. The book in this one was Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury. I’d read it years before, but its sudden appearance felt important.

A little while later, I remembered that there was something in one of my notebooks that I wanted to double check. I thought I'd left that particular notebook in storage, but then I spotted it in a pile of recently retrieved stuff on the coffee table. By then I'd forgotten what it was I wanted to look up, but I opened the notebook, and on the first page were “The Three Essential Things”—from Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury…

I wrote about synchronicities like this (as well as research magick and associative trails) in my recent column for Lit Reactor, and now they seem to be happening more often.

Keep your eyes open.

Three Essential Things:

Three Essential Things:By the way, according to Faber in Fahrenheit 451, the Three Essential Things are as follows:

Quality, texture of information.

Leisure to digest it.

The right to carry out actions based on what we learn from the interaction of the first two.

These seem unfortunately germane, lo these 70 years later…

Thanks for listening, reading, and responding,

-royc.

June 6, 2023

Different Waves, Different Depths

I’ve been dabbling in fiction since I started writing, though it took me a long time to feel confident with it. During a particularly dark period in my adult life, I decided I wanted to learn how to write screenplays. I’d gone through a horrible breakup, moved back home, and was working part-time at a chain record store. I was floundering around, unsure of what to do next.

One night I watched Richard Kelly’s Donnie Darko (2001) for the second time, but I saw it for the first. It struck something in me, in that time, and I wanted to figure out how to write a movie. I got the script, watched the movie repeatedly, and started studying what you put on the page to make things happen on the screen.

As a result, the screenplay I started writing was heavily influenced by Donnie Darko. I’ve worked on it off and on in the years since, and even took an introductory screenwriting class at Second City in Chicago (Shout out to Jeph Porter). A few years ago, at the behest of my friend Jaqi Furback, I finally novelized the whole thing into a loooong short story called “Fender the Fall.”

When the pandemic hit, all of my writing projects slowed to a pause. For a long time, I found it difficult to concentrate on anything of any length, and I found myself writing poems and short stories.

The results of all of the above, “Fender the Fall” and 8 others have now been collected into a book called Different Waves, Different Depths, which comes out on September 12th from Impeller Press.

More on that in a minute, but first, an excerpt! This is “Antecedent,” which was originally published on the Close to the Bone website in 2021.

AntecedentHe held six discrete bits of information in his head simultaneously. No way to write them down so he recalled them in order on three separate occasions, six blanks in formation like a constellation. He awoke with only the memory of remembering, but not the information, his head a form unfulfilled.

An hour later, he was up and reading a well-worn library copy of Debord’s Pangyric over coffee. He put down the book and ran his hands through his greasy hair. His stomach grumbled. “Time to venture out,” he thought as he grabbed his jacket. His one-room apartment was strewn with similar texts: The Revolution of Everyday Life, Temporary Autonomous Zone, The Society of the Spectacle, The Adventures of Dr. Faustroll, Pataphysicist. Not much to do but read when you’re chronically unemployed and can’t get away with stealing anything let alone a TV or cable. He’d done several short stretches of time for petty theft, check fraud, and impersonating a police officer, but it had been a while since the last job and the last bid. He fancied himself a revolutionary, a civil disobedient. He downed the last half of a cup of coffee, rinsed it, refilled it with tap water, and downed that. Then he grabbed his jacket and headed for the stairs.

Walking by a gallery down the street, he watched as an older gentleman loaded paintings into the space from a beat-up blue Econoline.

“Can I help you with those?”

The man barely looked at him but nodded.

He grabbed the next one from the van and walked it long-ways through the narrow doorway. The man he was helping never said a word as they filed the covered canvases from the van into the small gallery.

Walking in with the last one, he heard the van’s engine stutter on. Figuring that the man was moving it to a proper parking spot, he delicately ripped off enough of the packing paper from one of the canvases to see the work. He was aghast at the sight of it. It was like nothing he’d seen before. The colors, the shadows, the rhythms sang to him like a bird uncaged. He was seduced completely. If he were able to paint, this would be the statement he would make. Unable to help himself, he ripped open another one. The effect was repeated twofold. He began to sob as he set the second one upright. This one was larger and nearly vacant, having been washed over several times with white gesso. The few extant strokes and colors were exactly as he would have wanted them. He tore open another.

Lost as he was in the collection of art he had arranged on along the walls of the space, he failed to notice that the man he’d helped with them hadn’t returned. Their spell remained unbroken by the voice of the curator approaching.

“Hello… Sir?”

He hadn’t heard her, still examining the six paintings leaning against the walls, surrounding him: a tryptic along the longest wall, two tall ones opposite, and the biggest one on the back wall by itself: the blanks in order, just as he had remembered.

“Thank you so much for letting us show your work. Do you have an arrangement in mind? We’d like to get them up as soon as possible. The reception is in a couple of hours.”

Still trying to compose himself, he didn’t speak at first. Then, pointing around the three walls at the paintings there, he said, “Just as they are now.”

“Also, are you sure you don’t have anything in mind we could put on the marquee? We’ve left your name off as requested.”

“Thank you. That’ll do.”

“Okay... Will you be joining us tonight?”

He finally turned toward her. “I’m really not sure yet.”

She forced a smile. “Well, I hope to see you in a bit.”

He was hesitant to leave the paintings behind but stepped out into the evening air with a buzzing heart and head.

He stopped by a newsstand to check the paper for an article about the show he’d just taken responsibility for. Looking back through the weekend edition, he found it.

“Renowned Artist’s First Show in Over a Decade,” read the headline. The article said that the paintings had been created during nearly twelve years of total seclusion. After years of acclaim during which the artist felt he could do no wrong, he grew disillusioned with the art world. He decided to isolate himself and dig deeper, attempting to create a completely new form of painting.

“I’d say he succeeded,” he said to himself as he closed the paper. His stomach groaned again as he wondered if there would be free food at the opening.

Back at the gallery, the paintings were mounted just as he’d asked. The marquee out front read simply, “Artist’s First Show in Twelve Years.”

He walked in with borrowed confidence, but his smirk disappeared as soon as he saw the paintings on the walls. It was difficult to contain his emotions in the presence of such passion, such control. He stared into the strokes, mesmerized.

The curator walked in, startling him. He quickly stacked some cheese on a cracker and poured himself a glass of wine. Following his lead, she did the same.

“So good of you to join us,” she said over her glass.

He turned, finally acknowledging her presence.

“There was some doubt that any of us would get to actually meet you, given your lengthy seclusion and request to be alone while bringing in your work.”

“Well, I changed my mind,” he said smiling.

“The show is everything we expected and more,” she said looking at the two paintings on the wall nearest her, but when she turned back around, he wasn’t there. There was only his half-empty wine glass and half-eaten cheese and cracker tumbling to the floor beside her. “Where’d you go?”

“I’m right here,” he said, one painting to another, but she couldn’t hear him. He didn’t recognize his own voice. The peace in the paintings became panic in his veins.

Six discrete bits of information hanging in his head simultaneously. No way to write them down so he became them, six paintings in formation like a constellation. He awoke with only the memory of remembering, but not the information, his head a form with empty blanks. Six blanks now staring out from three walls, their form fulfilled.

Cover illustration by Jeffrey Alan Love. Book design by Patrick Barber. Different Waves, Different Depths

Cover illustration by Jeffrey Alan Love. Book design by Patrick Barber. Different Waves, Different DepthsThe story above is one of 9 stories in Different Waves, Different Depths, which is now available for preorder! The book takes its name from a comment an old crush made once about her feelings for me (Thank you, Little One). It also describes this collection, varying in style from the literarily weird to the science fiction. Jeffrey Alan Love did the beautiful cover illustration and Patrick Barber did the book’s design, inside and out. It’s 250 pages of flash stories, a pilot script, and the aforementioned out-of-print novella, Fender the Fall.

“Working the borderlands between philosophy, sci-fi, and ultra-contemporary social critique, these stories illuminate our strange cusp moment in a deeply humanistic and bracing manner. A sharp, propulsive, and canny collection.” — David Leo Rice, author, Drifter

Table of Contents:

Drawn & Courted

Kiss Destroyer

Antecedent

Not a Day Goes By

Dutch

Subletter

Hayseed, Inc.

Post-Intelligence

Fender the Fall

“In Roy Christopher’s inquiring, voracious tales, memory is a form of energy, and worlds emerge out of slippages, of which there are many more than we like to admit.” — Matthew Battles, author, The Sovereignties of Invention

There are time loops and time travel, reality television and big data, consultants who can make anyone a winner, a newspaper that’s just gone online-only, a band that never existed but is all too real, mistaken identities, roadtrips, drugs, guns, murder, and a love story or three.

Dive in deep, ease in the shallows, or just let the tide lap at your toes. Different waves are waiting.

As always, thank you for reading,

-royc.

June 1, 2023

Déjà View

Do you ever think you like something at first, and then later decide that you don’t? A friend of mine had this happen with a popular record years ago. He was really into it, and then he said he realized it was just the same moment over and over. As much as I like several of them, when the newest spate of Star Wars movies came out, I heard my friend’s words echo in my head.

I see such repetition mostly in television now. Over and over, there are stakes without consequences. Regarding Succession, Bill Wyman calls it “Narrative Groundhog Day.” It happens in the first season of The Mosquito Coast, for example. I was predisposed to like this series, fan as I am of Peter Weir’s 1986 movie and the author of the novel’s nephew, Justin Theroux, who stars in the show. As framed in the series, the premise of the story is one man and his family’s criminal response to the squeezing of means of the middle class (see also Weeds, Breaking Bad, Ozark, etc.). The husband and father of two played by Theroux is an inventor with a shady past (Harrison Ford plays him in the movie in one of his most manic and convincing performances). When the bad men come calling, he has break south and get his family to safety.

During this familial exodus, the following happen: dad is arrested; his daughter (played by the inimitable Logan Polish) crashes his truck into the police car to free him; his son is arrested in Mexico for shooting someone; the family breaks him out of jail and continues their quest for safe haven and freedom. Every time it looks like they’re screwed, they’re not. Stakes without consequences. The same moment over and over.

You can see the same repetition in TV series from across the spectrum: The Sopranos, Weeds, Dexter, Orange is the New Black, Fringe, Breaking Bad, American Horror Story, Ozark, and Succession, to name only a few. It seems more prevalent in the binge era, and I thought it was a byproduct of bingeing itself, but “weekly drops“ — that new thing they’re doing — illustrates otherwise. You really only know upon further reflection or maybe the second or third time through.

A coworker of mine once advised me to make sure I wasn’t repeating experience in my work. I’d like to demand the same from my entertainment.

The Object.Book News:

The Object.Book News:My short story collection, Different Waves, Different Depths, is currently in production! It comes out on September 12th on Impeller Press. I’ll have more details and a pre-order link in a forthcoming newsletter. So stoked on this one!

At long last, I’ve finished the manuscript for The Medium Picture! It didn’t survive the recent ownership/leadership shake-up at its publisher, so it’s looking for a new home. Here’s some advanced praise:

“Like a skateboarder repurposing the utilitarian textures of the urban terrain for sport, Roy Christopher reclaims the content and technologies of the media environment as a landscape to be navigated and explored. The Medium Picture is both a highly personal yet revelatory chronicle of a decades-long encounter with mediated popular culture.” — Douglas Rushkoff, author, Team Human

“Immersed in the contemporary digital culture he grew up with as a teenager, Roy Christopher is old enough to recall vinyl, punk, and zines — social media before TikTok and smartphones. The Medium Picture deftly illuminates the connections between post-punk music critique, the increasing virtualization of culture, the history of formal media theory, the liminal zones of analog vs digital, pop vs high culture, capitalism vs anarchy. It’s the kind of book that makes you stop and think and scribble in the margins.” — Howard Rheingold, author, Net Smart

Any takers? It’s so good…

Thank you for reading,

-royc.

May 27, 2023

Mistaken Algorithms

Cinema is our most viable and enduring form of design fiction. More than any other medium, it lets us peer into possible futures projected from the raw materials of the recent past, simulate scenes based on new visions via science and technology, gauge our reactions, and adjust our plans accordingly. These visions are equipment for living in a future heretofore unseen. As the video artist Bill Viola puts it,

the implied goal of many of our efforts, including technological development, is the eradication of signal-to-noise ratio, which in the end is the ultimate transparent state where there is no perceived difference between the simulation and the reality, between ourselves and the other. We think of two lovers locked in a single ecstatic embrace. We think of futuristic descriptions of direct stimulation to the brain to evoke experiences and memories.[1]

When we think of the future, the images we conjure end up on the screen.

“Long Live the New Flesh.” David Cronenberg’s Videodrome, 1983.

“Long Live the New Flesh.” David Cronenberg’s Videodrome, 1983.With only one adaptation, director David Cronenberg proved perhaps J.G. Ballard’s most effective cinematic interpreter. Roger Ebert said of his version of Crash, “it’s like a porno movie made by a computer: it downloads gigabytes of information about sex, it discovers our love affair with cars, and it combines them in a mistaken algorithm.”[2] These visions of intimate machines give both versions of Crash a sense of malign prophecy. Before Crash in 1996, an adaptation Ballard loved, Cronenberg had already established himself as the preeminent body-horror director with such films as The Brood (1979), Scanners, (1981), Videodrome (1983), The Fly (1986), Dead Ringers (1988), and Naked Lunch. (1991). Jessica Kiang writes of Crash, “Koteas’s Vaughan explains that his project is ‘the reshaping of the human body through technology,’ a pretty perfect summation of a recurring theme in the first half of Cronenberg’s career, best exemplified by his 1983 masterpiece, Videodrome.”[3]

In Videodrome, CIVIC-TV’s satellite dish operator, Harlan (played by Peter Dvorsky) pirates the signal of a plotless show of pure violence called “Videodrome” being beamed from bands in between. In search of unique programming for the station, Max Renn (played by James Woods) authorizes its rebroadcast. Renn soon finds that the footage is not faked and is PR for a socio-political movement weaponizing the signal for mind control. Professor Brian O’Blivion (played by Jack Creley) helped develop the signal to unify the minds of the viewers. Videodrome gave him a brain tumor and subsequent hallucinations. He sees the resultant state as a higher form of reality. As his daughter explains, “he saw it as part of the evolution of man as a technological animal. […] He became convinced that public life on television was more real than private life in the flesh. He wasn't afraid to let his body die.”[4] He tells Max, “the battle for the mind of North America will be fought in the video arena, the Videodrome. The television screen is the retina of the mind’s eye. Therefore, the screen is part of the physical structure of the brain. Therefore, whatever appears on the television screen emerges as raw experience for those who watch it. Therefore, television is reality, and reality is less than television.”[5] It doesn’t take long for the reality in this film to devolve into a hallucinatory state itself. As the dialog of the last scene goes, “to become the new flesh you have to kill the old flesh. Don't be afraid. Don't be afraid to let your body die. […] Watch. I'll show you how. It's easy. Long live the new flesh. Long live the new flesh.”[6]

Videodrome is another example of the view of the body—and the brain inside it—as an antenna, picking up signals from television broadcasts and the airwaves themselves. As Warren Ellis once said, “if you believe that your thoughts originate inside your brain, do you also believe that television shows are made inside your television set?”[7] It seems relevant here also that Albert Einstein wrote the preface to Upton Sinclair’s aptly titled 1930 treatise on telepathy, Mental Radio, which he described as being “of high psychological interest.”[8] These are visions of escape through media, escape routes as media.

The character of Professor Brian O’Blivion was inspired by Marshall McLuhan, one of Cronenberg’s college professors at the University of Toronto.[9] McLuhan famously appeared in a fourth-wall-breaking scene in Annie Hall (1977), where Woody Allen introduces him, speaking directly to the camera. That wall is the contested barrier of Videodrome. McLuhan’s concerns about information overload and media reconfiguring our brains were not lost on Cronenberg, and Cronenberg’s own concerns about the technological manipulation of brains and bodies weren’t lost on his son either.

An expectedly large leap from body horror’s origins in Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel, Frankenstein, Brandon Cronenberg’s 2020 film, Possessor, nonetheless concerns itself with manipulating flesh for murderous ends. Tasya Vos (played by Andrea Riseborough) hijacks bodies via their brains in order to carry out assassinations unscathed. Through an advanced neurological interface, she takes over another’s body. Once the hit is in, she returns to her own by forcing the host to kill themselves. Like the Sunken Place in Jordan Peele’s Get Out (2017), the cognitive contrivance in Possessor pushes one consciousness out of the way of another. Once in control of a new body in a new social context, the operative is able to perform heinous acts in their name—namely murder-suicides.

Predator Things: Brandon Cronenberg’s Possessor, 2020.

Predator Things: Brandon Cronenberg’s Possessor, 2020.When Tasya returns from a mission, she has to recalibrate to the real world in her own body. One of the tests for this debriefing process involves a number of analog, personal totems. This tests the idea that the analog world is our native environment as humans, as we all slide into ever more-digital worlds. The first of Tasya’s totems in the test is her grandfather’s pipe. The second is a mounted butterfly. “This is an old souvenir,” she remembers. “I killed her one day when I was a child and... I felt guilty... I still feel guilty.”[10] As much as the butterfly and her memory of it serve to anchor her here, her guilt is the real anchor. Guilt is our private connection to others.

Even so, when one of her victims, Colin Tate (played by Christopher Abbott), manages to wrest control of his body from her, he calls her agency into question. Using his fragmented access to Taysa’s memories, Colin manages to find her home, infiltrates it, and berates her husband:

just think, one day your wife is cleaning the cat litter and she gets a worm in her, and that worm ends up in her brain. The next thing that happens is she gets an idea in there, too. And it's hard to say whether that idea is really hers or it's just the worm. And it makes her do certain things. Predator things. Eventually, you realize that she isn't the same person anymore. She's not the person that she used to be. It's gotta make you wonder whether you're really married to her or married to the worm.[11]

Verifying the source of a message or an idea is a struggle even outside of our heads. When they pop in unannounced, there’s no way to know where they came from. It makes it difficult to care about the sender.

At the end of the movie when Taysa encounters the dead butterfly again during recalibration, she says she no longer feels guilty for killing it.

Yale University professor Dr. José M.R. Delgado’s 1969 book, Physical Control of the Mind: Toward a Psychocivilized Society, provides an intriguing precursor to Cronenberg’s film. In this book, Delgado outlines the methodology for Cronenberg’s fictional conceit. Delgado wrote, "by means of ESB (electrical stimulation of the brain) it is possible to control a variety of functions—a movement, a glandular secretion, or a specific mental manifestation, depending on the chosen target.”[12] While admitting that the brain is protected by layers of bone and membrane, he illustrates how easily it is accessed through the senses, drawing convenient comparisons between garage-door openers and two-way radios, and light waves and optical nerves. Direct brain interfaces through implants have existed since the 1930s when W.R. Hess wired a cat’s hypothalamus with electrodes. Hess was able to induce everything from urination and defecation to hunger, thirst, and extreme excitement.

Given the limited viability of such technology during the writing of Delgado’s book, he speculates the future of what he calls “stimoceivers,” writing, "it is reasonable to speculate that in the near future the stimoceiver may provide the essential link from man to computer to man, with reciprocal feedback between neurons and instruments which represents a new orientation for the medical control of neurophysiological functions.”[13] Though Delgado’s stimoceivers are becoming more and more viable, they still require the mind and the machine to adapt to each other.

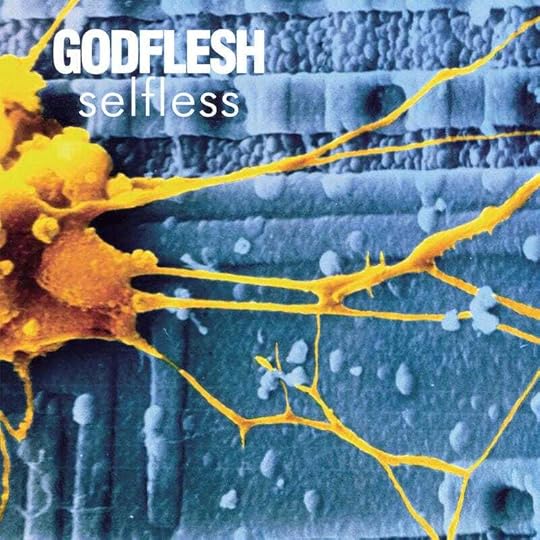

Wetware meets hardware: Godflesh’s Selfless, 1994.

Wetware meets hardware: Godflesh’s Selfless, 1994.The cover of Selfless, Godflesh’s 1994 record, is a picture of a human nerve cells growing on a microchip. It’s a picture of what’s called neuromorphic computing, a field of artificial intelligence that goes beyond using models of the human brain to physically harness its computing power, either by growing cells on chips or putting chips in brains. In August of 2020, Elon Musk debuted Tesla’s Neuralink brain implant, demonstrating the device on three unsuspecting pigs.[14] The small, coinlike device reads neural activity, and Musk hopes they will eventually write it as well, connecting brains and computers in a completely new way, mirroring neurons and computer chips. The Neuralink team hopes the devices will correct injuries, bypass pain, record and restore memories, and enable telepathy. As Ballard and the Cronenbergs warned us, one person’s mind-altering technology is another’s absolute nightmare. “In Godflesh,” Daniel Lukes writes, “the human is subsumed into the machine as an act of spiritual transubstantiation.”[15] Computer processors open another path out of the body.

ESCAPE PHILOSOPHY: Journeys Beyond the Human Body

ESCAPE PHILOSOPHY: Journeys Beyond the Human BodyThe essay above is an excerpt from Chapter 3, “MACHINE: Mechanical Reproduction,” of my book Escape Philosophy: Journeys Beyond the Human Body, which is available as an open-access .pdf and beautiful paperback from punctum books. It’s really quite good, but don’t take my word for it…

“Too often philosophy gets bogged down in the tedious ‘working-through’ of contingency and finitude. Escape Philosophy takes a different approach, engaging with cultural forms of refusal, denial, and negation in all their glorious ambivalence.” —Eugene Thacker, author, In the Dust of This Planet

“Using Godflesh—the arch-wizards of industrial metal—as a framework for a deep philosophical inspection of the permeable human form reveals that all our critical theory should begin on the street where wasted teen musicians pummel their mind and instruments into culture-shifting fault lines. Godflesh are not just a ‘mirror’ of all the horrors and glories we can inflict on our bodies, but a blasted soundscape of our moans. Roy Christopher’s book is a thought-provoking and delightful crucible of film, music, and the best kind of speculative thought.” — Peter Bebergal, author, Season of the Witch

“An interesting read indeed!” — Aaron Weaver, Wolves in the Throne Room

“An interesting read indeed!” — Aaron Weaver, Wolves in the Throne RoomIf you already have Escape Philosophy, or even if you do, and you want more of this kind of thing, check out Children of the New Flesh: The Early Work and Pervasive Influence of David Cronenberg, edited by David Leo Rice and Chris Kelso and published by the good people at 11:11 Press. It’s essential.

As always, thank you for reading,

-royc.

Notes:

[1] Bill Viola, Reasons for Knocking at an Empty House: Writings 1973–1994 (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1995).

[2] Roger Ebert, “‘Crash’ (1997),” RogerEbert.com, March 21, 1997, http://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/cra....

[3] Jessica Kiang, “‘Crash’: The Wreck of the Century,” The Criterion Collection, December 1, 2020, https://www.criterion.com/current/pos.... She continues, “so, when Vaughan later retracts that statement, calling it ‘a crude sci-fi concept that floats on the surface and doesn’t threaten anybody,’ it’s hard not to see Cronenberg slyly denigrating his own back catalog, or at least marking in boldface the end of his ongoing engagement with it. Sure enough, with the exception of a watered-down workout in 1999’s eXistenZ, Crash does represent a move away from the gleefully visceral grotesqueries of his early career, toward the more refined psychological grotesqueries of his twenty-first-century output.”

[4] David Cronenberg, dir. and writer, Videodrome (Montreal: Alliance Communications, 1983).

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] From Ellis’s defunct newsletter, quoted in Steven Shaviro, “Swimming Pool,” The Pinocchio Theory, January 29, 2004, http://www.shaviro.com/Blog/?m=200401.

[8] See Upton Sinclair, Mental Radio: Does It Work, and How? (Springfield: Charles C. Thomas, 1930), ix. Arthur Koestler called this a “symbolic act.” Arthur Koestler, The Roots of Coincidence: An Excursion into Parapsychology (New York: Vintage, 1972), 50.

[9] Ben Sherlock, “Long Live the New Flesh: 10 Behind the Scenes Facts about ‘Videodrome’,” Screen Rant, August 1, 2020, https://screenrant.com/videodrome-mov....

[10] Brandon Cronenberg, dir. and writer, Possessor (Toronto: Rhombus Media, 2020).

[11] Ibid.

[12] José M.R. Delgado, Physical Control of the Mind: Toward a Psychocivilized Society (New York: Harper & Row, 1969), 80.

[13] Ibid., 91.

[14] See Leah Crane, “Elon Musk Demonstrated a Neuralink Brain Implant in a Live Pig,” NewScientist, August 29, 2020, https://www.newscientist.com/article/.... See also Melissa Heikkilä, “Machines Can Read Your Brain. There’s Little That Can Stop Them,” Politico, August 31, 2021, https://www.politico.eu/article/machi....

[15] Daniel Lukes, “Black Metal Machine: Theorizing Industrial Black Metal,” in Helvete: A Journal of Black Metal Theory, Issue 1, edited by Amelia Ishmael, Zareen Price, Aspasia Stephanou, and Ben Woodard (Earth: punctum books, 2013), 79.

May 20, 2023

A Message in a Bottleneck

The biologist Robin Wall Kimmerer writes that when botanists go out in fields and forests looking for flora, they call it a foray, and when writers do the same, it should be called a metaphoray.[1] Marshall and Eric McLuhan open their book Laws of Media: The New Science with the claim that each of our technological artifacts is “a kind of word, a metaphor that translates experience from one form to another.”[2] That is, each new technological advance transforms us by changing our relationship to our environment, just as a metaphor does with our knowledge.

“Each person is his [sic] own central metaphor,” wrote Mary Catherine Bateson.[3] Bateson saw the perceptual processes of the organism as a metaphor for the complexities of the world outside it. With the spread and adoption of personal media and the internet, the network metaphor has creeped further and further into our thinking.[4] The center thins out to the edges as the network becomes central.[5] Extending it inward, Michael Schandorf writes that “every ‘node’ is a network all its own, each with its own very fuzzy boundaries and interpenetrations.”[6] Expanding it outward, Barry Brummett writes that texts are, “nodal: what one experiences here and now is a text, but it may well be a part of a larger text extending into time and space. Texts tend to grow nodes off themselves that develop into larger, more complex but related texts.”[7] And Steven Shaviro adds, “The network is shaped like a fractal. That is to say, it is self-similar across all scales, no matter how far down you go. Any portion of the network has the same structure as the network as a whole. Neurons connect with each other across synapses on much the same way that Web sites are linked on the World Wide Web.”[8] From texts to networks, our minds are permeable.[9] I belabor the point here because we are complicit in the use of these metaphors.

The connections of a network are what gives it its power. In turn, the network gives each node its power as well. For example, a telephone is only as valuable as its connection to other telephones. Where value normally derives from scarcity, here it comes from abundance. If you own the only telephone or your phone loses service, it’s worthless. In addition, each new phone connected to the network adds value to every other phone.[10] At a certain point, fatigue sets in. Connectivity is great until you’re connected to people you’d rather avoid. Each new communication channel is eventually overrun by marketers and scammers, leveraging the links to sell or shill, forcing us to filter, screen, buffer, or otherwise close ourselves off from the network.[11] There is a threshold, a break boundary, beyond which connectivity becomes a bad thing and the network starts to lose its value.

Fig 6.1: A tetrad of the network. It enhances connectivity, obsolesces isolation, retrieves word of mouth, and reverses into fatigue.

Fig 6.1: A tetrad of the network. It enhances connectivity, obsolesces isolation, retrieves word of mouth, and reverses into fatigue.In their Laws of Media, Marshall and Eric McLuhan outlined the ramifications of these media through their tetrad of media effects, which states that every new medium enhances something, makes something obsolete, retrieves a previous something, and reverses into something else once pushed past a certain threshold.[12] In Fig. 6.1, I’ve applied this metaphorical framework to the network.

When we buy into these infrastructures—networks or otherwise—we’re buying into their metaphors. Moreover, we’re buying into the idea that metaphors are an effective way to represent the world.[13] “A metaphor is always a framework for thinking, using knowledge of this to think about that,” Bateson once said.[14] The word metaphor means “carrying over,” and that’s just what their meanings do. Nodes and networks: eventually, we forget all of these are metaphors. “That is the real danger,” Robert Swigart writes, “unless we pause from time to time to consider how these metaphors work to create boundaries… they will control us without our knowledge.”[15] As long as we’re paying attention though, we can always defy them.

This is another excerpt from my new manuscript, The Medium Picture. This is from Chapter 6, “A Message in a Bottleneck,” which is a theory-heavy chapter about metaphors, machines, nodes and networks.

Author of Smart Mobs and Net Smart, among many other books, Howard Rheingold, says,

Immersed in the contemporary digital culture he grew up with as a teenager, Roy Christopher is old enough to recall vinyl, punk, and zines — social media before TikTok and smartphones. The Medium Picture deftly illuminates the connections between post-punk music critique, the increasing virtualization of culture, the history of formal media theory, the liminal zones of analog vs digital, pop vs high culture, capitalism vs anarchy. It’s the kind of book that makes you stop and think and scribble in the margins.

I can’t wait to share this one with you!

Thank you for reading,

-royc.

Notes:

[1] Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass, Minneapolis, MN: Milkweed Editions, 2013, 46; With thanks to Michael Schandorf.

[2] Marshall McLuhan & Eric McLuhan, Laws of Media: The New Science, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1988, 3; As Eric McLuhan notes in The Lost Tetrads of Marshall McLuhan, “Metaphor and the tetrad on metaphor are the very heart of Laws of Media.”; Marshall McLuhan & Eric McLuhan, The Lost Tetrads of Marshall McLuhan, New York: O/R Books, 2017, 200n; So much of Marshall McLuhan’s work was done with metaphors. As he wrote, interpolating Robert Browning, “A man’s reach must exceed his grasp or what’s a metaphor.”; Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1964, 64; See also, Yoni Van Den Eede, “Exceeding Our Grasp: McLuhan’s All-Metaphorical Outlook,” in Jaqueline McLeod Rogers, Tracy Whalen & Catherine G. Taylor (eds.), Finding McLuhan: The Mind, The Man, The Message, Regina, Canada: University of Regina Press, 2015, 43-61; Roger K. Logan, McLuhan Misunderstood, Toronto: The Key Publishing House, 2013, 39-40.

[3] Mary Catherine Bateson, Our Own Metaphor, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1972, 284; See also, Gregory Bateson, “Our Own Metaphor: Nine Years After,” in A Sacred Unity: Further Steps to an Ecology of Mind, New York: HarperCollins, 1991, p. 285.

[4] This is a trend that John Naisbitt spotted in newspapers in the late 1970s; See Chapter 8, “From Hierarchies to Networks,” in John Naisbitt, Megatrends: Ten New Directions Transforming Our Lives, New York: Warner Books, 1982, 189-205.

[5] Alexander R. Galloway, Eugene Thacker, and McKenzie Wark, Excommunication: Three Inquiries in Media and Mediation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014, 2.

[6] Michael Schandorf, Communication as Gesture, Bingley, UK: Emerald Publishing, 2019, 108; Latour defines the black box similarly: “Each of the parts inside the black box is itself a black box full of parts.”; Bruno Latour, Pandora's Hope: Essays on the Reality of Science Studies. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999, 185.

[7] Barry Brummett, A Rhetoric of Style, Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2008, 118.

[8] Shaviro goes on to flip McLuhan’s claim that electronic networks are an extension of the central nervous system to write, “every individual brain is a miniaturized replica of the global communications network.”; Shaviro, 2003, 12.

[9] Nicholas Carr writes, “Those who celebrate the ‘outsourcing’ of memory to the Web have been misled by a metaphor. They overlook the fundamentally organic nature of biological memory. What gives real memory its richness and its character, not to mention its mystery and fragility, is its contingency. It exists in time, changing as the body changes. Indeed the very act of recalling a memory appears to restart the entire process of consolidation, including the generation of proteins to form new synaptic terminals.”; Nicholas Carr, The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains, New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2010, 191.

[10] Kevin Kelly calls this “the fax effect.”; Kevin Kelly, New Rules for the New Economy, New York: Viking, 1998, 39-49.

[11] Using metaphors from epidemiology, Malcolm Gladwell calls this fatigue “immunity.”; Malcolm Gladwell, The Tipping Point, New York: Little, Brown, 2000, 271-275.

[12] McLuhan & McLuhan, 1988, passim.

[13] Neal Stephenson, In the Beginning was the Command Line, New York: William Marrow, 1999.

[14] Mary Catherine Bateson, How to Be a Systems Thinker: A Conversation with Mary Catherine Bateson, Edge, April 17, 2018: https://www.edge.org/conversation/mar...

[15] Robert Swigart, “A Writer’s Desktop,” In Brenda Laurel (ed.), The Art of Human-Computer Interface Design, Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Professional, 1990, 140-141.

May 5, 2023

Bandcamp Flashback Friday

My first book was an interview anthology called Follow for Now: Interviews with Friends and Heroes, and it’s available on Bandcamp. Today is #BandcampFriday, the day when they waive all of their fees, and the money goes directly to the artists. When you order directly from me through Bandcamp, you also get fun stuff like stickers. And if you’re into it, I’ll even sign the book for you!

Follow for Now includes interviews with such luminaries as Bruce Sterling, Douglas Rushkoff, DJ Spooky, Philip K. Dick, Aesop Rock, Eugene Thacker, Erik Davis, Howard Bloom, David X. Cohen, Richard Saul Wurman, N. Katherine Hayles, Manuel De Landa, Rudy Rucker, Milemarker, Steve Aylett, Doug Stanhope, Paul Roberts, Shepard Fairey, Tod Swank, dälek, Eric Zimmerman, Steven Johnson, Mark Dery, Geert Lovink, McKenzie Wark, Brenda Laurel, Gareth Branwyn, and many, many more.

Spanning the seven years of the turn of the millennium (1999-2006), Follow for Now is an eclectic, independently-minded snapshot of the intellectual landscape at the beginning of the twenty-first century — 43 interviews with minds of all kinds. It also includes an extensive bibliography, a full index, and weighs in at nearly 400 pages, all typeset and designed by Patrick Barber.

Ellis Goddard of the Resource Center for Cyberculture Studies says,

“Roy Christopher has long been regarded as an insightful (and sometimes inciteful) inquisitor of Internet-age antics. Follow for Now thus drops sufficiently many known and intriguing names in its table of contents (and on its cover) to stay on the shelves of both snooty philosophers and free-thinking subculturalites for decades. But the nuggets those names provide are intriguing enough to justify that stay, on those shelves and others. In short, the content is as intense as the cast.”

And Maria Popova of Brain Pickings, writes,

“Relentlessly stimulating and insight-packed, Follow for Now is the kind of book I’d like to see published every decade, and devoured every subsequent decade, from now until the end of humanity.”

Get yours from Bandcamp today for Bancamp Friday!

And don’t forget the sequel: Follow for Now, Vol. 2 from punctum books!

The Structural Dynamics of FlowFor this auspicious fifth day of May, may I also recommend The Structural Dynamics of Flow by my dudes Alaska and steel tipped dove.

In the years (decades) since his nascent Atoms Family and Hangar 18 days, versatile emcee Alaska has slowed down his flow. Don’t get it deficient: It’s for our benefit, not his. We’re the ones getting lazier, not him. He’s just making sure we can hear what he’s saying rather than marveling at his breath control. His lyrics are as topical as they are personal, and how many emcees do you know who will rhyme “mercy killer” with “Percy Miller” without pausing for effect?

Beatmeister steel tipped dove has worked with everyone from bulletproof lyricists like billy woods, Mr. Muthafuckin eXquire, and R.A.P. Ferreira to the much artier Tone Tank, Pink Siifu, and Nosaj from New Kingdom. Coming fresh off his Backwoodz Studioz debut, Call Me When You’re Outside, Dove’s production here is as jazzy as it is hazy, the beats swing between ambient loops and orthodox boom-bap. He keeps it all tight while still giving Alaska plenty of room to play.

There’s something both timeless and timely about The Structural Dynamics of Flow. The blending and bending of hip-hop sounds like New York, but maybe an area you haven’t been to yet. Pack your blunderbuss and come along with us.

Thanks for reading and listening,

-royc.

April 17, 2023

Mystery Loves Company

A few years ago, as I was on a Blue Line train on my way to the loop in Chicago, I was reading Tade Thompson’s Rosewater (Apex, 2016) and listening to Hole’s Celebrity Skin (DGC, 1998). At the exact moment that I read the phrase “all dressed in white” on page 57 of Rosewater, Courtney Love sang the same phrase in my ears on the song “Use Once & Destroy.”

A few months later, I was clearing some records off my iPod to add a few new things, including the then newly released Jay-Z record, 4:44 (Roc Nation, 2017). When I finally stopped deleting files and checked the available space, it was 444 MB. Just minutes later, while reading the latest Thrasher Magazine (July 2017), I happened to notice the issue number: 444.

Yesterday, I was browsing the clearance rack at Hot Topic (closely guarded fashion secret) as “MakeDamnSure” by Taking Back Sunday was playing loudly overhead. Just as Adam Lazzara sang “You are… you are so cool,” I slid a True Romance shirt into view that read “You are so cool” on the front.

Cliff’s Notes to Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow in Miracle Mile (1988).

Cliff’s Notes to Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow in Miracle Mile (1988).I watched Steve De Jarnatt’s Miracle Mile (1988) the other night. A while back, William Gibson posted a picture of the Cliff’s Notes for Gravity’s Rainbow with the caption “The Key.” This sent me on a search. I dug in thrift stores, looked in bookstores, asked proprietors. No one seemed to know whether these particular Notes existed.

A couple of years later, I found out that the Cliff’s Notes to Pynchon’s most famous and confounding work were a prop for De Jarnatt’s 1988 apocalyptic love story, Miracle Mile (Gibson also mentions the movie in his 1993 novel Virtual Light, which I recently reread). The movie is wild, overdone in some ways and underdone in others. It reminded me of two of my other all-time favorites, Alex Cox’s Repo Man (1984) and Richard Kelly’s Southland Tales (2006), though it’s not as intentionally campy as the former and perhaps not as fully realized as the latter.

Sometimes things just sync up with no meaning outside of the alignment itself. Sometimes it’s a winding wandering with no logic whatsoever. Other times the path is what’s important. Sometimes it’s the difference between searching and finding.

“…myths form from memories.”

“…myths form from memories.”Occasionally I get a book in the mail or from the library, and I can’t remember how I found it. In late 2000, during an especially impoverished period of my adult life, I was going to the Seattle Public Library almost every day. I was reading bits and pieces of so many books. I remember digging deeper into the work of Marshall McLuhan and Walter Benjamin, finding more Rebecca Solnit and Guy Debord, discovering Paul Virilio and Jean Baudrillard. I remember the row of volumes I had lined up against the wall in an almost completely unfurnished apartment, their spines and call numbers pointed at the ceiling. Due dates, new discoveries, and new arrivals kept the books rotating, and at some point, I started having a difficult time keeping up with where I'd read what. So, I started keeping a research journal.

While those journals — I’ve been keeping them ever since — help me remember things I’ve read after I’ve read them, they’re less helpful in tracing my path to the things I read in the first place.

Skateboarding/zine-making/movie flowchart, December 8, 2019.

Skateboarding/zine-making/movie flowchart, December 8, 2019.I’ve tried to keep up with the paths with flowcharts like the one above. It’s not a new idea. Early versions include Paul Otlet’s 1934 Traité de Documentation and Vannevar Bush’s memex from the 1940s. The memex — a portmanteau of memory and expansion — was a dream machine for navigating and researching with the vast stores of information of the time using cameras, microfilm, and print — an annotated analog hypertext system. In his 1945 article “As We May Think,” Bush wrote, “Wholly new forms of encyclopedias will appear, ready-made with a mesh of associative trails running through them, ready to be dropped into the memex and there amplified.”1 The problem with the way that Bush proposes such “associative trails” is that they are of little use to anyone aside from the researcher who’s trod them. I mean, do you find the above flowchart useful without some narrative context? As Donald Norman puts it,

Following the trails of other researchers sounds like a wonderful idea, but I am not convinced it has much value. Would it truly simplify our work, or would all the false trails and restarts simply complicate our lives? How would we know which paths would be valuable for our purposes? [...] If you, the reader, were to follow these trails, you might not be enlightened.2

Maybe the mystery is better. I have so many precious books and movies and ideas that lack provenance or pedigree. I might wonder how I found them, but does it matter? Whether by an alignment of events or a meandering path, neither changes the end result.

You can plan not synchronicity nor serendipity, but magic happens every day.

Thank you for reading.

KYEO,

-royc.

1Vannevar Bush, “As We May Think,” The Atlantic Monthly, July 1945, 176 (1): 101–108.

2Donald A. Norman, Living with Complexity, Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2011, 134-135.

April 10, 2023

Taxonomy Season

Hey, I wrote another piece for Lit Reactor called “Building a Mystery.” Kev Harrison included it in his “5 Must Read Horror Articles 27 March 2023” for This is Horror, writing, “Writer Roy Christopher looks at the moving parts of some well-known stories and explores how writers can use these examples to create their own, in this fascinating writing advice piece for LitReactor.”

More on that below.

But first…

Talk Your Talk

I’m on Talk Your Talk with my man Alaska this week. I’m the first guest on this spin off from his usual show, Call Out Culture with Curly Castro and Zilla Rocca, on which I was also the first guest. I did the artwork for their Michael Myers/Nas-themed “Killmatic” episode, too.

In this new one, we talk about my books, new, old, and not-out-yet, as well as a few high-minded social-science theories… and the raps, of course.

You can listen to our brief discussion via the podcasting network of your choice.

Building a Mystery My own sketchy rendering of Frank the Rabbit from Donnie Darko (2001).

My own sketchy rendering of Frank the Rabbit from Donnie Darko (2001).Richard Kelly’s Donnie Darko (2001), has been a source of inspiration for me for years. I recently wrote another piece for Lit Reactor called “Building a Mystery,” in which I speculate about what might constitute a taxonomy for storytelling, something akin to the usual concerns about character, plot, and structure, but different. Donnie Darko is one of the movies I analyze in the piece. Here’s an excerpt:

In a 2005 interview with Daniel Robert Epstein (R.I.P.), Pi director Darren Aronofsky likened writing to making a tapestry: “I’ll take different threads from different ideas and weave a carpet of cool ideas together.” In the same interview, he described the way those ideas hang together in his films, saying, “every story has its own film grammar, so you have to sort of figure out what the story is about and then figure out what each scene is about and then that tells you where to put the camera.”

Now, when watching a movie or reading a book, I often find myself trying to break down its constituent parts. Also, when writing or creating, I sometimes try to establish a loose taxonomy of the elements involved in the project, a list of the salient aspects of the story. These are orthogonal to the usual concerns about structure (e.g., the three acts, beat map, midpoint, climax, etc.), but they’re as important. Necessary but not sufficient.

Read the whole thing over on Lit Reactor.

No Sell Out.

The first print run of Boogie Down Predictions has sold out! There are copies still available at shops and various places online, but a second printing is imminent.

Mad thanks to everyone who copped one! We are stoked to have moved so many so quickly.

And if you don’t have it, what are you even doing?

Thank you for your continued interest,

-royc.

March 26, 2023

Dead Precedents: Four More Years

Last week marked the four-year anniversary of the publication of my book Dead Precedents: How Hip-Hop Defines the Future! In celebration, here are some pictures from the book’s release and some information on a related project you may have heard about.

Also, we’ll be returning to Volumes Bookcafé in Chicago in July for an event with Boogie Down Predictions contributors Ytasha L. Womack, Kevin Coval, and others! Look for more details on that in a future newsletter.

Thanks for reading Roy Christopher! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Read on!

We launched Dead Precedents properly at Volumes Bookcafé in Chicago with readings by me, Krista Franklin, and Ytasha L. Womack.

Krista Franklin, me, and Ytasha L. Womack. [Photo by Lily Brewer.]

Krista Franklin, me, and Ytasha L. Womack. [Photo by Lily Brewer.]Ytasha and I went on to do a talk at the Seminary Co-op in Hyde Park, and I spoke at SXSW again, this time specifically about the ideas in Dead Precedents.

Talkin’ beaks and rhymes at SXSW. [Photo by Matt Stephenson.]

Talkin’ beaks and rhymes at SXSW. [Photo by Matt Stephenson.]

As Pecos B. Jett called it, “Biz Marquee!“

As Pecos B. Jett called it, “Biz Marquee!“A couple of months later, I ventured to my adopted home in the Pacific Northwest. I got to speak at Powell’s City of Books in Portland with Pecos B. Jett. I was even on TV!

Next up was a fun chat at the Elliott Bay Book Company in Seattle with Charles Mudede.

Me and Charles Mudede yuckin’ it up at Elliott Bay. [Photo by Lily Brewer.]

Me and Charles Mudede yuckin’ it up at Elliott Bay. [Photo by Lily Brewer.]I was also on my favorite hip-hop podcast, Call Out Culture with my mans Alaska, Zilla Rocca, and Curly Castro.

I know Amazon is wack, but Dead Precedents was also a #1 New Release in both their Rap Music and Music History & Criticism categories.

Take that, Beastie Boys Book!

Take that, Beastie Boys Book!Dan Hancox reviewed Dead Precedents for The Guardian, writing that it is, "written with the passion of a zine-publishing fan and the acuity of an academic."

Dead Precedents in The Guardian. Review by Dan Hancox.

Dead Precedents in The Guardian. Review by Dan Hancox.Mark Reynolds at PopMatters wrote, "In Christopher’s construction, hip-hop is is not merely party music for black and brown Gen-Xers and millennials, but the first salvo in a radical, transformative way of understanding and making culture in the technological era — the beginning, in essence, of the world we’re living in now."

My photographer friend Tim Saccenti, who has several photos in the book, sent me a picture of it with the hands from Run the Jewels’ RTJ3, the cover of which he also shot.

Dead Precedents with the hands from Run the Jewels' RTJ3. [Photo by Tim Saccenti.]

Dead Precedents with the hands from Run the Jewels' RTJ3. [Photo by Tim Saccenti.]Many thanks to all the people who bought the book, said nice things about it, came out to hear me talk about it, gave me rides, put me up at your home, or spread the word.

Companion Compendia BOOGIE DOWN PREDICTIONS: Hip-Hop, Time, and Afrofuturism

BOOGIE DOWN PREDICTIONS: Hip-Hop, Time, and AfrofuturismIf you already have Dead Precedents, and you’re interested in more about hip-hop, cyberpunk, and Afrofuturism, a bunch of my friends and colleagues and I have put together a companion collection of essays called Boogie Down Predictions: Hip-Hop, Time, and Afrofuturism. Harry Allen, Hip-Hop Activist and Media Assassin says,

“How does hip-hop fold, spindle, or mutilate time? In what ways does it treat technology as, merely, a foil? Are its notions of the future tensed…or are they tenseless? For Boogie Down Predictions, Roy Christopher's trenchant anthology, he's assembled a cluster of curious interlocutors. Here, in their hands, the culture has been intently examined, as though studying for microfractures in a fusion reactor. The result may not only be one of the most unique collections on hip-hop yet produced, but, even more, and of maximum value, a novel set of questions.”

Cover Art by Savage Pencil.

Cover Art by Savage Pencil.Boogie Down Predictions: Hip-Hop, Time, and Afrofuturism is available directly from Strange Attractor or from the outlet of your choice! If you're still not convinced, here are more details, including the table of contents, back-cover blurbs, and a nice review from The Wire Magazine!

More Companions

I also have two companion volumes of interviews: Follow for Now (Well-Red Bear, 2007) and Follow for Now, Vol. 2 (punctum books, 2021): two decades worth of discussions, 80 interviews in all. Too many to list here. Check them out!

Thank you for reading.

Hope you're well,

-royc.

Thanks for reading Roy Christopher! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

March 21, 2023

Shooting Starlets: Girls Gone Wildin'

As if the transition from adolescence to adulthood weren’t hard enough, fame further complicates coming of age. One is reminded of a young Drew Barrymore, coming out of rehab for the first time at age 13 and the countless stories that didn’t end with her happy present. But there’s nothing quite as cool as youthful nihilism, especially when wielded by young women. Live fast, die young: Bad girls do it well.

Ten years ago, Harmony Korine’s Spring Breakers and Sophia Coppola’s The Bling Ring represented the grown-up debuts of beloved childhood Hollywood princesses, Selena Gomez, Vanessa Hudgens, Ashley Benson in one, and Emma Watson in the other. The two films are also similar for their adult themes and media commentary. Against this backdrop of conflicting contexts, Korine calls his cast “gangster mystics.” No one would say that a refusal to grow up is endearing, but resistance is fertile.

Thanks for reading Roy Christopher! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

The similarities between these two movies remind me of when in 2007 the Coen Brothers and Paul Thomas Anderson both did adaptations of stories set in West Texas, as both camps tend to write their own scripts. No Country for Old Men and There Will Be Blood are companion pieces in the same way that Spring Breakers and The Bling Ring are, but here the young ladies are the ones with the guns.

Cautionary Tail: Vanessa Hudgens, Ashley Benson, and Rachel Korine.

Cautionary Tail: Vanessa Hudgens, Ashley Benson, and Rachel Korine.These two movies seem to prefigure the ten years of turmoil since their release. Rolling Stone’s David Fear points out that in the decade since, Spring Breakers has ripened more than it has aged. He writes, “its portrait of an all-sensationalism-all-the-time mindset as an extension of American life only feels more on-brand today. You can see that same tabloid mojo online, in the news, and for a while, radiating out of the White House. What a difference a decade makes.” Korine says, “I wanted to make a film that feels like there’s no air in the room. I never wanted the audience to be comfortable or complacent.” If nothing else, he succeeded in that, especially during the movie’s inciting incident.

Spring Breakers’ heist scene might be the best few minutes of cinema of the 21st century so far. Brit (Ashley Benson) and Candy (Vanessa Hudgens) rob the Chicken Shack restaurant with a hammer and a squirt gun while Cotty (Rachel Korine) circles the building in the getaway car with the camera (and us) riding shotgun. Our limited vantage point gives the scene an added tension because though we are at a distance, it feels far from safe. Much like the security camera footage of Columbine and Chronicle, and the camera-as-character of Chronicle and Cloverfield, we receive limited visual information while experiencing total exposure. The girls’ mantra: “Just pretend it’s a fucking video game. Act like you’re in a movie or something.”

Alien (James Franco) arrives as the girls’ douche ex machina, an entity somewhere between True Romance’s Drexl Spivey (1993), Kevin Federline, and Riff Raff, the latter of whom supposedly sued over the similarities. He bails them out of jail after a party gone astray and takes them home to his arsenal. What could possibly go wrong?

Douche ex Machina: James Franco as Alien.

Douche ex Machina: James Franco as Alien.Selena Gomez does the least behaving badly, but her role as Faith is still a long way from Alex Russo or Beezus. As she tells her grandmother over the phone,

I think we found ourselves here. We finally got to see some other parts of the world. We saw some beautiful things here. Things we’ll never forget. We got to let loose. God, I can’t believe how many new friends we made. Friends from all over the place. I mean everyone was so sweet here. So warm and friendly. I know we made friends that will last us a lifetime. We met people who are just like us. People the same as us. Everyone was just trying to find themselves. It was way more than just having a good time. We see things different now. More colors, more love, more understanding… I know we have to go back to school, but we’ll always remember this trip. Something so amazing, magical. Something so beautiful. Feels as if the world is perfect. Like it’s never gonna end.

Spring break is heavy, y’all. As Korine himself explains,“I grew up in Nashville, but I was a skater, so I was skateboarding during spring break. Everyone I knew would go to Daytona Beach and the Redneck Riviera and just fuck and get drunk — you know, as a rite of passage. I never went. I guess this is my way of going.” Ultimately the movie illustrates Douglas Adams’ dictum that the problem with a party that never ends is that ideas that only seem good at parties continue to seem like good ideas. “It was about this dance of surfaces,” Korine says. “The meaning is the residue that drips down below the surface.”

Speaking of bad ideas and surfaces, Sophia Coppola’s The Bling Ring, which is based on a real group of fame-obsessed teenagers, is a mad mix of both. Not since Catherine Hardwicke’s Thirteen (2003; which features Spring Breakers’ Hudgens) has a group of teens been so overtaken by expensive clothes, handbags, and bad behavior. This crew of underage criminals used internet maps and celebrity news to find out where their targets lived and when they would be out of town. They subsequently stole $3 million worth of stuff from the empty homes of Paris Hilton, Lindsay Lohan, Megan Fox, Orlando Bloom, and Audrina Patridge. Once caught, The Ring seem more concerned with what their famous victims think than with the charges brought against them. “That part of our culture used to be small — that pop, ‘guilty pleasure’ side of things,” Coppola says, “Now it just won’t stop growing.” It’s an attitude that has only grown further and faster in the era of Instagram and TikTok.

It would be remiss of me not to note that two of my favorite composers, Cliff Martinez and Brian Reitzell, respectively, put the music together for these movies. The mood of Spring Breakers is mostly set by Martinez in collaboration with Skrillex. “I love them both,” Korine says, “and wanted to take a certain element of what each does best and have them merge. I wanted the music to have a physical presence.” Atlanta rappers Gucci Mane, who’s also in the movie, Nicki Minaj, and Waka Focka Flame also add texture to the sound. “The movie was always meant to work like a violent, beautiful pop ballad,” Korine adds, “something very polished that disappears into the night.” Seemingly just the right mix of music always accompanies Sophia Coppola’s films, and The Bling Ring features a blend of hip-hop, Krautrock, and electronic pop that reads more eclectic than it actually sounds: Sleigh Bells, Oneohtrix Point Never, CAN, 2 Chainz, M.I.A., Azealia Banks, Klaus Schulze (R.I.P.), Frank Ocean, and others. Discounting the importance of music in creating the pressure that permeates these films would be an oversight.

One more film celebrating a ten year anniversary that deserves mention here is Gia Coppola’s Palo Alto. It’s intimately connected to the other two movies: It’s based on James Franco’s short story collection of the same name, and it was adapted and directed by Sophia Coppola’s niece. Palo Alto beautifully captures the gauzy grey areas when the boundaries between adolescents and adults blur beyond recognition. More so even than Spring Breakers, it foreshadows Franco’s embodying the worst parts of his characters off-screen in the years since.

James Franco and Emma Roberts in Gia Coppola’s Palo Alto.

James Franco and Emma Roberts in Gia Coppola’s Palo Alto.The AV Club’s Hattie Lindert notes, “Spring break, by nature, is fleeting—but […] the cultural appetite for brazenly vibes-first content against a high-stakes backdrop of violence, sex, and ecstasy, endures.” Life is what you can get away with, and though these films are cautionary tales of an extreme nature, they prove that caution isn’t cool. Youth might be wasted on the young, but our heroes don’t concern themselves with consequences. There’s a decade of evidence piled up right behind us.

Happy Spring!

Thank you for reading,

-royc.

Thanks for reading Roy Christopher! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.