Roy Christopher's Blog, page 12

September 27, 2022

The Advent Horizon

I call the line we draw at the edge of our comfort zone with new technologies the advent horizon. It’s a line we draw as individuals as well as a society at large. In his book Human as Media, Andrey Miroshnichenko describes it in terms of eras, writing, "If an era is shorter than a generation, the balance between the speed of technological innovation and the speed of cultural adaptation breaks down." We feel a sense of loss when we cross one of these lines.

At the DMA conference in 2011 in Boston, I described it as follows:

From the Socratic shift from speaking to writing, to the transition from writing to typing, we’re comfortable—differently on an individual and collective level—in one of these eras. As we adopt and assimilate new devices, our horizon of comfort drifts further out while our media vocabulary increases. Any attempt to return to a so-called “Natural State” is a futile attempt to get back across the line we’ve drawn for ourselves.

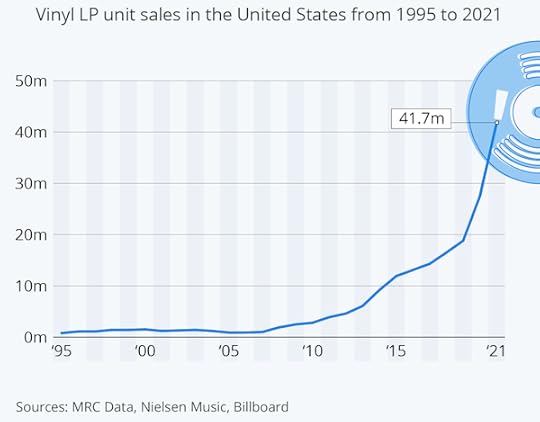

Evidence that we’ve crossed one of these lines isn’t difficult to find. Think about the resurgence of vinyl record sales since 2010. Fans of vinyl records are either clinging to their youth or celebrating the only true music format that ever mattered. A vinyl record is a true document of a slice of time.

I visited Full Sail University in Winter Park, Florida several years ago, and something about the curriculum struck me. In their animation and game design programs, students take illustration (with pencils and paper), flipbook-style animation (with paper and lightboxes), and 3D modeling (real-world 3D, sculpture with clay and other materials) before they ever sit down at a computer. Though they are natives to the latter, they are forced to learn their skills in the analog world before moving to the digital.

A vinyl record is an analog totem from a previous era. Teaching animation on paper before computers is analog scaffolding for the digital world. Clinging to a previous era and having to back up to learn something new, these are both evidence of a new era, that an advent horizon has been crossed.

Each generation is born during a certain technological era, between these lines we draw. We are imprinted by the media technology with which we grow up. For instance, there has always been a television in my world. When I was born, it was there. In contrast, my parents remember when the first TV arrived in their house. With today's personal media, television shows—along with every other kind of media content—are beamed directly to portable screens via invisible networks.

As Alan Kay once said, "Technology is anything that was invented after you were born." I have never known a world without television, and my students have never known or don’t remember a world without television, computers, the web, or cellular phones. Perhaps they will cross a line of comfort when something new becomes the norm for their children, but a world before personal media means nothing to them.

The Medium PictureThe above bit is more from my book-in-progress, The Medium Picture. We're all living through a novel overlap of generations and technological eras, and The Medium Picture explicates some of the fallout.

Thank you for your continued interest and support,

-royc.

September 20, 2022

When Everyone's a Winner

"It’s all become marketing and we want to win because we’re lonely and empty and scared and we’re led to believe winning will change all that. But there is no winning." — Charlie Kaufman, BAFTA, 2011 [1]

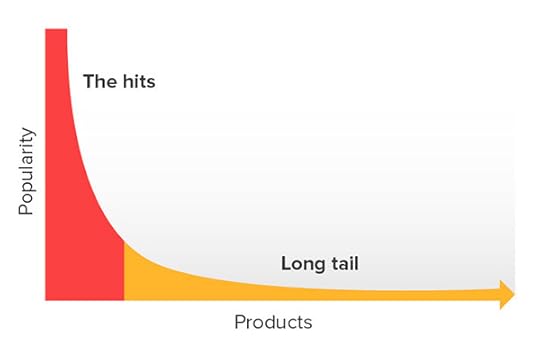

The dictum, "In the future, everyone will be famous for 15 minutes," for which several sources have claimed credit, is widely attributed to Andy Warhol. [2] Regardless of who first said it, those 15 minutes of the future are the popular origins of the long tail of fame. Though the phrase has been around since the late 1960s, its proposed future is here.

In his 1991 essay, "Pop Stars? Nein Danke!" Scottish recording artist Momus updates Warhol’s supposed phrase to say that in the future, everyone would be famous for 15 people, writing about the computer, "We now have a democratic technology, a technology which can help us all to produce and consume the new, 'unpopular' pop musics, each perfectly customized to our elective cults." [3] In Small Pieces Loosely Joined, David Weinberger’s 2002 book, he notes about bloggers, content creators, comment posters, and podcasters: “They are famous. They are celebrities. But only within a circle of a few hundred people.” He goes on to say that in the ever-splintering future, they will be famous to ever-fewer people, and—echoing Momus—that in the future provided by the internet, everyone will be famous for 15 people. [4] Democratizing the medium means a dwindling of the fame that medium can support.

Around the turn of the millennium, the long tail, [5] the internet-enabled power law that allows for millions of products to be sold regardless of shelf space, reconfigured not only how culture is consumed but also how it is created. It's since gotten so long and so thick that there’s not much left in the big head. As the online market supports a wider and wider variety of cultural artifacts with less and less depth of interest, they each serve ever-smaller audiences. Even when a hit garners widespread attention, there are still more and more of us farther down the tail, each in our own little worlds.

In his 1996 memoir, A Year with Swollen Appendices, Brian Eno proposes the idea of edge culture, which is based on the premise that "If you abandon the idea that culture has a single center, and imagine that there is instead a network of active nodes, which may or may not be included in a particular journey across the field, you also abandon the idea that those nodes have absolute value. Their value changes according to which story they’re included in, and how prominently." [6] Eno’s edge culture is based on Joel Garreau’s idea of edge cities, which describes the center of urban life drifting out of the square and to the edges of town. [7] The lengthening and thickening of the long tail plot our media culture as it moves from the shared center to the individuals on the edges, from one big story to infinite smaller ones.

Now, what does such splintering do to the economics of creating culture?

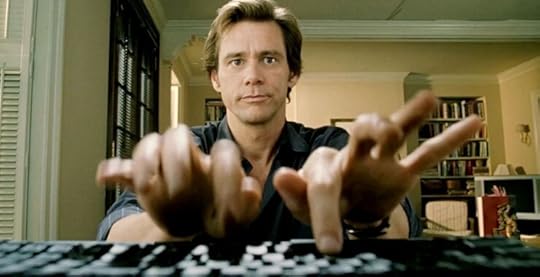

"The lottery sucks! I only won 17 bucks!" — Rioter in Bruce Almighty (2003).

Bruce Nolan, played by Jim Carrey in the 2003 movie, Bruce Almighty, is a man unimpressed with the way God is handling human affairs. In response, God lets him have a shot at it. One of the many aspects of the job that Bruce quickly mishandles is answering prayers. His head is flooded with so many, he can't even think. He sets up an email system to handle the flow, but the influx overwhelms his inbox. As a solution to that, he implements an autoresponder to send back a message that simply reads, “Yes” to every request.

Many of the incoming prayers are pleas to win the lottery. His wife's sister Debbie hits it. "There were like 433 thousand other winners," his wife Grace explains, "so it only paid out 17 dollars. Can you believe the odds of that?" [8] Subject to Bruce’s automated email system, everyone who asked for a winning ticket got one. Out of the millions on offer, everyone who prayed to God to win the lottery won 17 dollars.

That's what you get when you're famous for 15 people for 15 minutes. That's what you get when everyone's a winner.

The mainstream isn't the monolith it once was. It's a relatively small slice of the total culture now, markedly smaller than it was at the end of last century. For better or worse, the internet has democratized the culture-creating and distributing processes we used to privilege (e.g., writing, music, comedy, filmmaking, etc.), and it's brought along new forms in its image. Since the long tail took hold around the turn of the millennium, the edge culture of the internet has splintered even further via social media and mobile devices. Anyone can now create content and be famous for 15 people for 15 minutes—and earn 17 dollars for their efforts.

The Medium PictureThis piece above is another excerpt from my thinking-aloud about my book-in-progress, The Medium Picture. Here's the brief overview:

The ever-evolving ways that we interact with each other, our world, and our selves through technology is a topic as worn as the devices we clutch and carry everyday. How did we get here? Drawing from the disciplines of media ecology and media archaeology, as well as bringing fresh perspectives from subcultures of music and skateboarding, the book illuminates aspects of technological mediation that have been overlooked along the way. With a Foreword by Andrew McLuhan, The Medium Picture shows how immersion in unmoored technologies of connectivity finds us in a world of pure media and redefines who we are, how we are, and what we will be.

One day you'll get to read it all in one place in a much more organized form (a book!).

ICYMI:

Speaking of, in case you missed them, I have a few new books out! Get 'em however you can, and if you want to review something, let me know.

As always, thank you for reading and responding.

Hope you're well,

-royc.

Notes for the essay above:

1. Charlie Kaufman, Screenwriters' Lecture, BAFTA, September 30, 2011.

2. Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, "Andy Warhol's One-Dimensional Art: 1956–1966," In Michelson, Annette (ed.), Andy Warhol, Cambridge, MA:The MIT Press, 2001, 28.

3. The 1991 Momus essay was published by the Swedish fanzine Grimsby Fishmarket in 1992 and in the daily paper Svenske Dagblatt in 1994.

4. David Weinberger, Small Pieces Loosely Joined, New York: Perseus Books, 2002, 103-104.

5. Chris Anderson, The Long Tail, New York: Hyperion, 2006.

6. Brian Eno, A Year with Swollen Appendices, London: faber & faber, 1996, 328.

7. Joel Garreau, Edge City: Life on the New Frontier, New York: Doubleday, 1991.

8. Tom Shadyac [dir.], Bruce Almighty, Los Angeles: Universal Pictures, 2003.

September 13, 2022

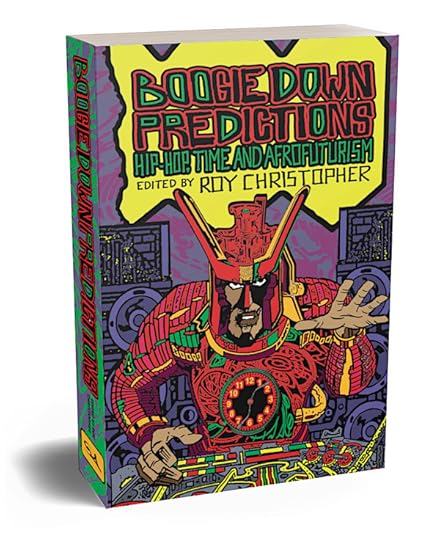

Boogie Down Predictions is Out Today!

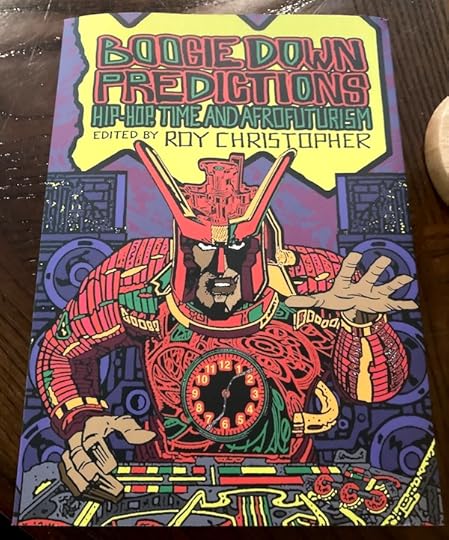

After a global pandemic, all the supply-chain delays, and a printing backlog, Boogie Down Predictions: Hip-Hop, Time, and Afrofuturism is available! You can get yours directly from Strange Attractor, the MIT Press, or the source of your choice (yes, including that one)! It's also in fine bookstores everywhere today. It is well worth the wait, but the wait is over!

Below is a bit about how it came together, a look at the cover, the blurbs, the table of contents, and an early review from The Wire magazine.

Read on!

Over the past several years, I gathered up some friends, and we’ve been working on an edited collection, sort of a companion to my book, Dead Precedents: How Hip-Hop Defines the Future (Repeater Books, 2019). Time was one of the aspects of both hip-hop and cyberpunk that I didn’t get to talk about much in that book, so I started asking around. I found many other writers, scholars, theorists, DJs, and emcees, as interested in the intersections of hip-hop, time, and Afrofuturism as I was. As I continued contacting people and collecting essays, I got more and more excited about the book.

Well, it's now available from Strange Attractor Press! Check out the cover above by Edwin Pouncey a.k.a. Savage Pencil!

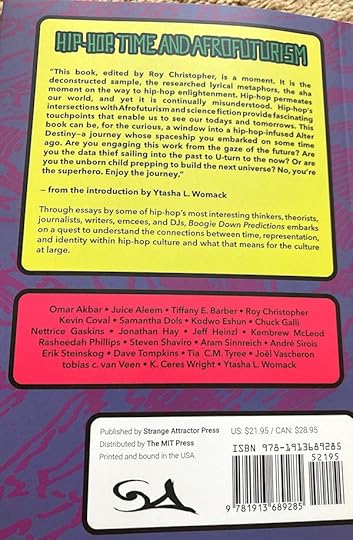

Check out the jacket copy, the blurbs, and the table of contents!Through essays by some of hip-hop’s most interesting thinkers, theorists, journalists, writers, emcees, and DJs, Boogie Down Predictions is a quest to understand the connections between time, representation, and identity within hip-hop culture, as well as what that means for the culture at large. Introduced by Ytasha L. Womack, author of Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture (Lawrence Hill Books, 2013), this collection explores these temporalities, possible pasts, and further futures from a diverse, multi-layered, interdisciplinary perspective.

“This book, edited by Roy Christopher, is a moment. It is the deconstructed sample, the researched lyrical metaphors, the aha moment on the way to hip-hop enlightenment. Hip-hop permeates our world, and yet it is continually misunderstood. Hip-hop’s intersections with Afrofuturism and science fiction provide fascinating touchpoints that enable us to see our todays and tomorrows. This book can be, for the curious, a window into a hip-hop-infused Alter Destiny—a journey whose spaceship you embarked on some time ago. Are you engaging this work from the gaze of the future? Are you the data thief sailing into the past to U-turn to the now? Or are you the unborn child prepping to build the next universe? No, you’re the superhero. Enjoy the journey.”

— Ytasha L. Womack, from her Introduction

“Boogie Down Predictions offers new ways of listening to, looking at, and thinking about hip-hop culture. It teaches us that hip-hop bends time, blending past, present, and future in sound and sense. Roy Christopher has given us more than a book; it’s a cypher and everyone involved brought bars.”

— Adam Bradley, author, Book of Rhymes: The Poetics of Hip-Hop

“The study of hip-hop requires more than a procession of protagonists, events, and innovations. Boogie Down Predictions stops the clock—each essay within it a frozen moment, an opportunity to look sub-atomically at the forces that drive this culture.”

— Dan Charnas, author, Dilla Time: How A Hip-Hop Producer Reinvented Rhythm and Changed the Way Musicians Play

“How does hip-hop fold, spindle, or mutilate time? In what ways does it treat technology as, merely, a foil? Are its notions of the future tensed…or are they tenseless? For Boogie Down Predictions, Roy Christopher’s trenchant anthology, he’s assembled a cluster of curious interlocutors. Here, in their hands, the culture has been intently examined, as though studying for microfractures in a fusion reactor. The result may not only be one of the most unique collections on hip-hop yet produced, but, even more, and of maximum value, a novel set of questions.”

— Harry Allen, Hip-Hop Activist & Media Assassin

Preface – Roy Christopher

Introduction – Ytasha L. Womack

I. TIME

1. Take Me Back: Ghostface’s Ghosts – Steven Shaviro

2. Two Dope Boyz (In a Visual World) – Tiffany E. Barber

3. Close to the Edge: “This Is America” and the Extended Take in Hip-Hop Music Video – Jeff M. Heinzl

4. Glitched: Spacetime, Repetition, and the Cut – Nettrice R. Gaskins

5. “The Theology of Timing” Black Consciousness and the Origin of Hip-hop Culture – Omar Akbar

6. Breakbeat Poems – Kevin Coval

7. The Free Space/Time Style of Black Wholes – Juice Aleem

8. Chopping Neoliberalism, Screwing the Record Labels: DJ Screw, Atavistic Hipsters and Temporal Politics – Aram Sinnreich & Samantha Dols

II. TECHNOLOGY

9. Scratch Cyborgs: The Hip-Hop DJ as Technology – André Sirois

10. Public Enemy and How Copyright Changed Hip-Hop – Kembrew McLeod

11. Done by the Trickle Trickle: Jbeez With the Ley Liners – Dave Tompkins

12. Preprogramming the Present: The Musical Time Machines of Gabriel Teodros – Erik Steinskog

13. The Cult of RAMM:∑LL:Z∑∑: A Hagiography into Chaos – Joël Vacheron

14. Hip-Hop’s Modes of Production are Futuristic – Chuck Galli

15. #ThisIsAmerica: Rappers, Racism, and Twitter – Tia C. M. Tyree

III. THE FUTURE

16. Further Considerations on Afrofuturism – Kodwo Eshun

17. Afrofuturism and the Intersectionality of Civil Rights, the Space Race, Hip-Hop, and Black Femininity – K. Ceres Wright

18. Afrofuturism in clipping.’s Splendor & Misery – Jonathan Hay

19. Black Star Lines: Ontopolitics of Exodus, Afrofuturist Hip-Hop, and the RZA-rrection of Bobby Digital – tobias c. van Veen

20. Constructing a Theory and Practice of Black Quantum Futurism – Rasheedah Phillips

Many thanks to Jamie Sutcliffe and Mark Pilkington at Strange Attractor Press for their support and enthusiasm, Dominic Rafferty for the stellar layouts, and Savage Pencil for the dopest cover. Thanks to those who contributed words, images, and direction, those who wished us well, and those who didn't.

And thank you for checking it out!

A Review in The Wire:Hank Shocklee by Netrice Gaskins.

Also, there's a nice review of the book in the September issue of The Wire:

Boogie Down Predictions is available directly from Strange Attractor, the MIT Press, or the source of your choice (yes, including that one)! It's also in fine bookstores everywhere today. I cannot wait for you to see this thing!

Spread the word and the love!

Thank you!

As always, thank you for your continued interest and support! It is appreciated.

So stoked on this one!

Looking forward,

-royc.

September 11, 2022

Turn on the Bright Lights

A few weeks ago, I looked up a song on YouTube, got busy with something else, and inadvertently let the algorithm run. When I started paying attention again, a new Interpol song was playing. Realizing both that I hadn't listened to them since their debut and that the new song reminded me of the Afghan Whigs, I decided to play catch-up on both of their respective discographies.

After I listened to various records from both bands over the next few days, I found myself returning to that first Interpol more than any of the others. Soon, it was the only one I was listening to -- and I haven't stopped.

Turn on the Bright Lights (Matador Records) came out exactly twenty years before my recent kick began. Plagued by comparisons to Joy Division, Interpol's debut is rich with many other veiled and not-so-veiled influences. The shoe-gazing tendencies of Ride and My Bloody Valentine, a jaunty bounce more akin to Echo and the Bunnymen or the Doors than to their contemporaries the Strokes, and a post-punk gloom Ian Curtis could only dream of are all inherent in the early Interpol. Recorded as it was in November of 2001, 9/11 also hangs heavy over the record.

Interpol emerged from an odd New York indie-rock, post-punk revival, a scene that included TV on the Radio, Yeah Yeah Yeahs, the National, and the aforementioned Strokes. Theirs was a rich crop, not too unlike the CBGB bands of a previous era, bands like New York Dolls, the Velvet Underground, Suicide, Blondie, Television, and Talking Heads. Interpol's beginnings were in the waning days of the compact disc, when downloading MP3s was still new, and bandwidth wasn't yet wide enough enable streaming, before smartphones and social media splintered fanbases into ever and ever smaller niches. Their scene may be the last of its kind.

Though the band had written the songs on Turn on the Bright Lights long before 9/11, they have acknowledged that new meanings emerged afterwards. For instance, the song "NYC" seems to be about New York specifically after 9/11, and as Paul Banks sings on "Obstacle 1," "It's different now that I'm poor and aging / I'll never see this place again." These are laments for a time and a place that's never coming back. This is the sound of that sense of loss.

Publicist UK's 2015 debut, Forgive Yourself (Relapse Records) is the other record that I think of immediately in the midst of this rediscovery. Publicist UK is the merging of members of Municipal Waste, Discordance Axis, Revocation, Goes Cube, and several other bands. Where Interpol's debut conjured lazy comparisons to Ian Curtis and Joy Division, Publicist UK's brings to mind Andrew Eldritch and Sisters of Mercy. Like Turn on the Bright Lights (I'm finding), Forgive Yourself is one of those records I get stuck on for weeks. And like Interpol's Paul Banks, Publicist UK's Zachary Lipez is a writer, a post-punk poet masquerading as a rock lyricist. His pen drops lines like "You’re a knife in a world of cutters" from "I Wish You'd Never Gone to School" and "Pain’s a secret no one keeps / You’re the lie that I believe" from "Levitate the Pentagon," as well as the following from "Cowards":

We were born to lick boots

And pretend it was steak

It’s not hard in this world

To love what you hate

Post-punk has always been more lenient than its punk precursor. It's a genre more forgiving of experimentation, more tolerant of outside influences. Where, as Andy Greenwald once pointed out [1], punk is a cul-de-sac, post-punk is more of a wide, windy road. At its commercial peak in 1979, it included the angular and atonal guitars of Gang of Four, Public Image Limited, and Wire, the damaged pop of Joy Division, Talking Heads, and Devo, and the gothic drama of The Cure, Sisters of Mercy, and Siouxsie and the Banshees. Like most genres, there's an invisible thread that loosely unites these bands, an unseen aesthetic that links them. That same thread stretches from post-punk's origins over four decades ago, through Interpol to Publicist UK, and beyond.

Interpol may never outdo their debut, and I may never know what's so alluring about it, but I suspect it has something to do with that post-punk thread. As much guff as they got for peddling plagiarism, Interpol had clones of their own. The early 2000s owe a lot to them, their scene, and their debut album. [2]

Thank you for reading this one-off Sunday-evening edition. Our regular newsletter schedule will resume next week.

There's a Big Release coming on Tuesday! I'm so excited!

More soon,

-royc.

See Andy Greenwald, Nothing Feels Good: Punk Rock, Teenagers, and Emo, New York: St. Martin's Griffin, 2003, pp. 147-148.

This piece benefited greatly from discussions with my friends Natalie Baltierra and Nicole Nesmith.

September 6, 2022

Clay Tarver: Gone Glimmering

Clay's a guitarist, a writer, a director, and as you'll see below, he's been doing really cool stuff for a few decades now.

In addition, this one features cameos by Greg Dulli and Donal Logue.

Read on!

CLAY TARVER: Gone Glimmering

Illustration by Josh Row

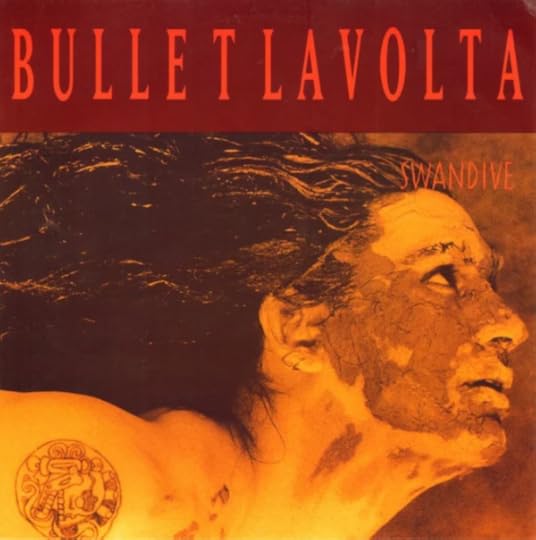

I first came across Clay Tarver in the very early 1990s. His guitar playing drove two of my favorite bands back then: Bullet LaVolta and Chavez. The former was, like a lot of the bands of the time, a hybrid of punk, metal, and some third strain of rock that was brewing but had yet to boil. I noticed producer Dave Jerden’s name on the back of several CD jackets in and near my player: Red Hot Chili Peppers’ Mother’s Milk, Jane’s Addiction’s Nothing’s Shocking, Alice in Chains’ Facelift, Armored Saint’s Symbol of Salvation, and Bullet LaVolta’s Swandive. Swandive (RCA), Bullet LaVolta’s last proper record, came out the same day as Nirvana’s Nevermind (DGC), September 24, 1991. They broke up not long after.

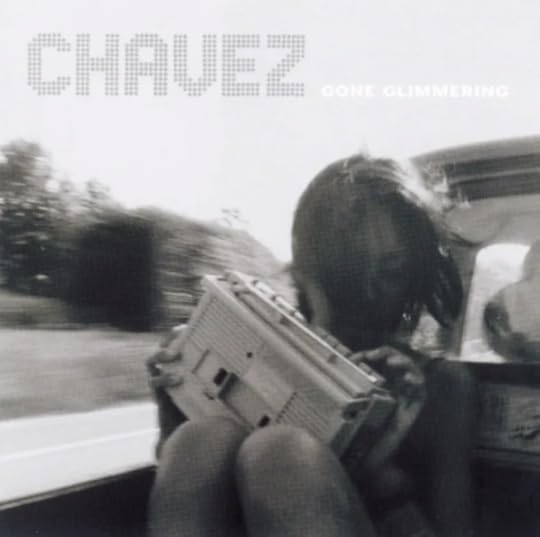

Tarver’s next band, Chavez, recorded two of the best records of the decade, both of which sound as firm and fresh now as they did then. Gone Glimmering (1995) and Ride the Fader (1996) helped Matador Records maintain a hand in the chokehold on the decade-defining sound. (The other hand belonged to Sub Pop.) Along with Matt Sweeney’s lilting vocals, it was Tarver’s guitar that formed that sound. I’ve always considered him among players whose guitar sound is their band’s identity. Think John Haggerty, Bob Mould, J. Mascis, Mary Timony, Steve Albini.

I saw Chavez play in Seattle in 1996, and after the show I went to say “hi” to Clay. I shook his hand and introduced myself, then noticed that I’d interrupted a three-way conversation-in-progress. There were mildly annoyed dudes standing on either side of me. I soon realized I was standing between Greg Dulli and Donal Logue, two of Tarver’s old friends and stars in their own right. Dulli is the lead singer of the legendary Afghan Whigs, and Logue, though he’s done tons of other things, was the dad on Fox’s Grounded for Life (2001–5) and currently plays Harvey Bullock on Gotham.

I recently asked Donal about Clay, and he had the following to say:

Clay Tarver is smarter and more talented than anyone I’ve ever met, but the super-human thing about Clay is he’s never been an attention-seeker or used any of his insanely unfair talents in some kind of narcissistic pursuit. He was the last word in any conversation regarding art or politics, but (and this is hard to articulate), he was never a dick about it. He was always just right, and his thinking was always at another level. High-school, all-state basketball star? I wouldn’t have known it unless his family told me. One of the best guitarists of all time? His own kids didn’t know he played guitar. No one has influenced me more than Clay Tarver. It’s impossible to describe Clay Tarver in a sentence, Roy, so I don’t even want to try!

Donal reiterated that the thing he finds so amazing about Clay is his modesty. “What really blows me away,” Donal said, “is how he avoided any kind of self-serving behavior, despite his gifts and talents.”

Toward the turn of the millennium, Tarver made the switch from music to movies and put together some outstanding and memorable clips in a place where it’s difficult to stand out. He directed the “Jimmy the Cabdriver” spots for MTV, which featured Donal as a greasy, fast-talking cabdriver, directed the ubiquitous “Got Milk?” commercials, and co-wrote the feature film Joy Ride (2001) with J.J. Abrams. He now serves as a consulting producer and writer for HBO’s Silicon Valley. Tarver recently signed on to script the sequel to Dodgeball for Fox, but he says that’s not likely to happen. He also owes Greg Dulli a phone call.

Roy Christopher: You’ve been on stage as a guitarist and are now writing scripts and producing. How do the two roles—one out in front of the crowd and one behind the scenes—compare? Which do you like better?

Clay Tarver: Well, the first question is easy. Being on stage is one hell of a lot more fun. And not because you’re the focus of the attention, of all the applause, etc. To me, it’s more about getting some kind of visceral gratification for what I’m doing as it happens. It’s tremendous. There’s nothing like performing with a group, in front of people, where you’re kind of all in this special moment together. Writing is the opposite. Writing is all about creating that moment for others. Sometimes fool-proofing it. It’s about craft and discipline and serious self-editing. And I suppose I enjoy the challenge. I do. Even in music, you can’t get on stage without doing the hard work of writing. But writing’s not fun. Look, I feel very fortunate to be doing what I do. I’m creatively challenged to the hilt. But I’d be lying if I told you I don’t miss playing whenever I wanted to.

RC: Man, the 1990s were a weird time for music. Looking back, it seems like genres were bending and blending in such odd ways. What do you like these days?

CT: Huh. I don’t know if I agree with you. For me, my favorite time of music was the Creem magazine days. Genres were all over the place. Any issue could have Cheap Trick, Aerosmith, The Sex Pistols, Blondie, KISS, Nugent, Elton John, Rick Derringer, and Bowie.

The ’90s were more a generational thing to me. I was glad to be a part of it. But it was much more sort of straightforward. What am I into today? Not much new. Tinariwen. Queens. Still listening to a lot of Dennis Wilson and Glen Campbell. Love the Master’s Apprentices. Saw John Prine for the first time recently and loved it.

RC: Fair enough... Donal Logue and Greg Dulli are two guys whose paths have crossed yours at various times over the past twenty-odd years. Tell me about the connection among you three.

CT: Donal was my roommate in college. And he was Bullet La- Volta’s road manager and general best friend. He came on tour with us.

In Champaign, Illinois the day of the World Series Earthquake—twenty-five years ago last month—we met and have all been friends ever since. In fact, I owe Greg a call right now (he lives right near me), and he gets real pissy when I owe him one.

Donal and I later did the cab driver things. I’d gotten a job at MTV when I moved to New York City to start Chavez. That’s actually how I became a writer. They wanted to turn it into a feature, so I thought I’d give it a try. I figured if I ever wanted to direct more stuff it would be a good skill to have. The movie never got made. But it gave me my career.

It’s funny. I never wanted to be a writer. I was one of those guys who, when I finished college, was thrilled to never write another paper again. Now fucking look at me.

RC: Ha. Speaking of, you’re a writer and consulting producer on HBO’s Silicon Valley, which is hilarious and accurate as far as my experience in start-ups has been. Have you worked in that world at all?

CT: Nope. Never. But Mike Judge did a million years ago. He’s the creator of the show, and a guy I’ve done feature work with for something like fifteen years. (A great musician, by the way. Sick stand-up bass player. A pro before he got into animation.)

Also, Alec Berg, our show runner, has a brother who worked in that world. Between us we read, did research, went on trips up there. But we also have really serious advisers who help us. We’re in the midst of Season 2 right now. Really in the trenches.

RC: Awesome! I can’t wait to see where it goes next. Okay, having been successful in two different areas of entertainment, do you have any advice for those aspiring musicians or writers out there?

CT: Ya know, people always want to “break in” to music or film or whatever. But I always found that to be a weird phrase. I think you just do what you want and hope people like it. And now, more than ever, that’s possible. Music’s great because there’s no barrier to entry. You have instruments and guys and you just go do it. If people like it, there ya go. Film is obviously more expensive. But, Christ, there’s so many different ways to get stuff out there. People make shorts and bits and all kinds of stuff. And if it’s good, usually people will find it. I say just keep doing. Keep making stuff. Keep at it.

RC: I know you’re working on Dodgeball 2, but what else is coming up?

CT: I’ve got some stuff in the works. Dodgeball 2 doesn’t seem like it’s going to happen. But I’m hoping to keep at it with Silicon Valley. I have some pretty exciting feature things kicking around. And I’m even making a music-based TV show. But in truth, who the hell knows?

[November 7, 2014]

Follow for Now, Vol. 2The interview above is an excerpt from Follow for Now, Vol. 2: More Interviews with Friends and Heroes, which is available as a free Open Access .pdf or a lovely paperback from punctum books. The book includes 37 interviews with minds of all kinds, including Ishmael Butler of Shabazz Palaces, El-P of Run the Jewels, Dave Allen of Gang of Four, M. Sayyid of Antipop Consortium, Matthew Shipp, Labtekwon, Juice Aleem, Brian Eno, Ytasha Womack, Tricia Rose, danah boyd, Mark Dery, Gareth Branwyn, Ian Bogost, Simon Critchley, Simon Reynolds, Malcolm Gladwell, and William Gibson, as well as the first interview with Tyler, The Creator, and the last one with RAMM:∑LL:Z∑∑, among many others. And each interview is illustrated by dope artists like Josh Row and Laura Persat. It's so good!

Follow for Now, Vol. 2 is now available at BookPeople in Austin, Texas, (as is Fender the Fall) as well as many other fine booksellers. My man Dustin (picture above) picked up the pair.

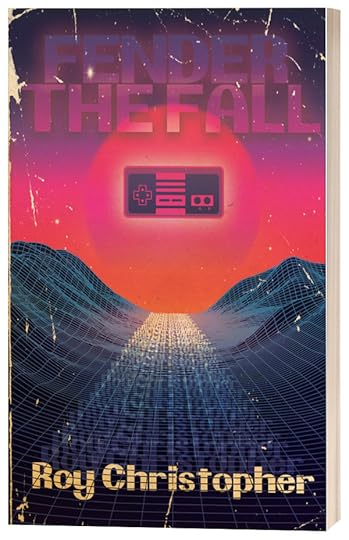

Speaking of Fender the Fall...

Fender the Fall came out a year ago, and the events in the book happen during the first week of September (this week) in 2002 and 1991. It's about Chris Bridges, a lovelorn physics graduate student who goes back in time to return the journal of his high-school crush in order to save his marriage and her life. The plan doesn’t go as planned.

Tagline: You don’t know what you’ve got until you get it back.

It’s available from Alien Buddha Press! It’s 5”x8” and 136-pages long, like a good paperback should be. It’s the perfect fall read.

I was fortunate enough to get Matthew Revert to design the cover and Mike Corrao to do the typesetting. As a result, it’s a sharp-looking little book.

Here’s what other people are saying about it:

Here’s what other people are saying about it:

“A fun, classic roller-coaster of a time-travel story that could have been published in the 1950s, except that it’s furnished with all manner of savvy insights into current 2020s life.” — Paul Levinson, author of The Plot to Save Socrates

“Fender the Fall is a nostalgia-infused journey through time about second chances and the causality of love. It’s a formative song from your youth revisited, a favorite VHS tape found in the back of your closet.” – Joshua Chaplinsky, author of The Paradox Twins

“Hard-boiled strange loops in a froth of weird.” – Will Wiles, author of Plume

Many thanks to Matthew Revert (cover design) and Mike Corrao (typesetting) for making this thing look so good; Red Focks for putting it out there; Paul Levinson, Josh Chaplinsky, Will Wiles, Jaqi Furback, Gabriel Hart, C.W. Blackwell, Ira Rat, J. Matthew Youngmark, and Jeph Porter for their time, feedback, and kind words; and Claire Putney, from whom I stole the title.

Here’s a soundtrack I put together while writing Fender the Fall. It has songs mostly from and around the years in the story.

Order your copy of this lovely, little paperback from Alien Buddha Press now! You won’t regret it.

One last thing... BOOGIE DOWN PREDICTIONS!Boogie Down Predictions finally comes out next week from Strange Attractor Press! It's available to order directly from the publisher or for preorder from the outlet of your choice (even that one). Please preorder it if you can! Preorders set in motion all kinds of good stuff for books and their creators.

More on this one next week. Don't you dare sleep!

Thank you for reading this far. I appreciate you.

More news soon,

-royc.

August 31, 2022

Through Being Cool

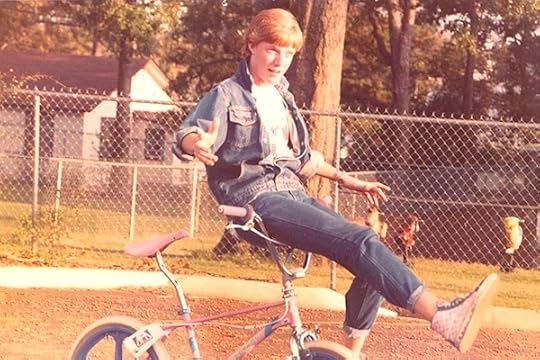

The factors involved in this move’s impact on me are several. I was in the throes of adolescence. It’s a time of trying on identities and seeking out tribes. I'd tried various sports, played Dungeons & Dragons for a couple of years, but by eighth grade I had discovered the activities and music that still define me today: BMX, skateboarding, punk rock, heavy metal, and hip-hop. I wasn't a fully formed personality yet, but I had a few, new ideas. That move would help solidify my self like nothing before it.

At Richmond Hill High School, they had a leveled system within the grades. Group A was remedial, group B was regular, and group C was advanced. Ideally, one would take all of their classes within their group. I was an eighth-grade C, but some of the 8C classes were full. So, I had a few 8C classes, a two 9B classes, and 8B P.E. Yeah, it was confusing.

In addition, by the time I arrived, the school year was already underway. The usual high-school cliques had all been established, and as it turned out, I didn’t fit in to any of the alphanumeric groups, least of all the 8Cs. Theirs was a tight circle established over years of taking the same classes together, and I was on the outside of it. The ninth graders made fun of me for being in their classes yet not being one of them. It wasn’t long before I gave up trying to fit in anywhere. Being cool was just not a possibility for me. I had a few friends, but like any 13-year old, I felt more ostracized and alone. This only intensified my interest in the activities and music I’d found in the year or so before. By the time we moved back to Alabama nine months later, I had a much better idea of who I was.

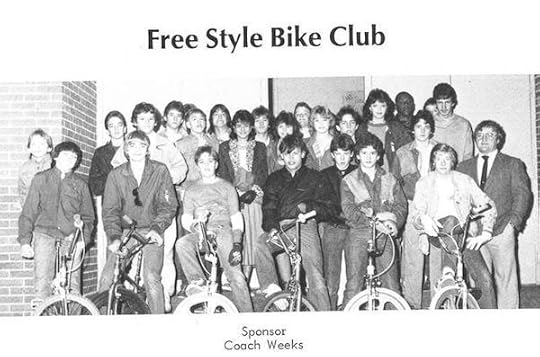

Back in Alabama, I fell in with the BMX and skateboard kids. Skateboarding was on an upswing in the mid-1980s, and BMX racing’s nascent precursor to the X-Games, freestyle trick riding, was gaining popularity. In the ninth grade, I started the “Free Style Bike Club” to further my interest in BMX bikes and foster a community around riding them. It wasn't a total success. I think we officially met twice, once mainly to take the picture for the yearbook. There are a lot of people in that picture, but don't doubt for a second that we were the outcasts in southeast Alabama. Coach Weeks was not really into it. None of it was cool. I was just passionate enough about doing tricks on my tiny bike to do it no matter and just arrogant enough to organize something to support it. I tried to organize a similar group in high school, but was met with the same indifference. I think that group only met twice as well.

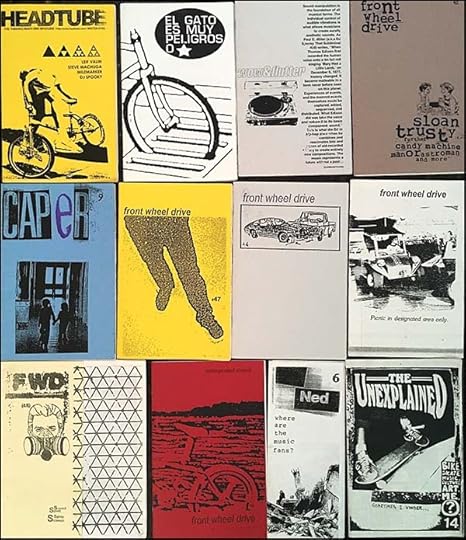

The summer before tenth grade, my friends and I started putting together a zine. It’s impossible to overstate the importance of making zines in my teens. These homegrown publications, cut and pasted together with scissors and glue and run off at the local copy shop, were the culmination of all the things that defined me. Making them taught me how to write about those things. My initial interest in the creation of these stapled-and-Xeroxed papers was laying out the pages. The grainy graphics of other zines still excites my eyes, and when I first saw them, I wanted to master all of the grungy photocopy techniques. Having grown up with an artist mom, I always thought I’d be an artist of some sort. I was even an art major for my first three years of college, aiming to go into some strain of graphic design.

Making zines also turned me into a writer. After all, if I wanted a review of the new Oingo Boingo or 7 Seconds record or an article about the 1986 Haro Summer Tour, I had to write it. By the time I finished undergrad, the writing outmoded the design, and I was an aspiring music journalist.

From mid-1984 until sometime in 1991, I did freestyle shows at community centers and schools and competed in BMX flatland competitions. Somewhere in there, I came to idolize the makers of the magazines more than the riders of the bikes. Where I’d always wanted to be a rider like Ron Wilkerson, Dave Nourie, or Dave Vanderspek, I soon wanted to be a writer like Andy Jenkins, Mark Lewman, or Spike Jonze. They were the crew behind Freestylin' and Homeboy magazines, as well as countless zines of their own. Though I was as in awe of the riding as I was the writing, I felt more comfortable with the words. I was--and still am--a mediocre BMX rider at best, but I felt like I could get better at writing and documenting these interests. One hopes that I still am.

When the BMX industry took a dive in the early 1990s, I continued making zines. I worked at record stores throughout undergrad, so, though bikes and skateboards remained among my zines’ pages, the content included more and more music. Once I moved to the Pacific Northwest in 1993, I put my DIY experience to work writing for regional music magazines.

If you’re reading this, then you probably know all of the interests above remain central my work. It was a cumulative effect, but that single move in the eighth grade galvanized my resolve and solidified my identity and its attendant activities: BMX, skateboarding, music, and writing about all of the above.

DISCONTENTS:And I never really stopped... The latest zine my friends and I put together is called discontents, and it features stories on Ceremony, Hsi-Chang Lin a.k.a. Still, and Unwound; interviews with emcee Fatboi Sharif, Coherence director James Ward Byrkit, and Crestone director Marnie Elizabeth Hertzler; pieces by Cynthia Connolly, Spike Jonze, Andy Jenkins, Timothy Baker, Greg Pratt, and Peter Relic; cover art by Tae Won Yu, layouts by Patrick Barber and Craig Gates, and drawings by Zak Sally, Marcellous Lovelace, and myself.

It's 50 solid pages of good stuff about good stuff. Get yours here!

Mixtape Menage podcast:Here's a clip of me talking to Eiliyas of Mixtape Menage about my move from zines to books, the part of my life that follows the story above:

Thank you for indulging me.

Hope you're well,

-royc.

August 24, 2022

A Now Worth Knowing

"...Our technology has produced the vision of microscopic giants and intergalactic midgets, freezing time out of the picture, contracting space to a spasm." – Rosi Braidotti, Nomadic Subjects

"How did you get here?" asks Peter Morville on the first page of his book Ambient Findability (O’Reilly, 2005). It’s not a metaphysical question, but a practical and direct one. Ambience indirectly calls attention to the here we’re in and the now we're experiencing. It is all around us at all times, yet only visible when we stop to notice. In Tim Morton’s The Ecological Thought (Harvard University Press, 2010), he explains it this way:

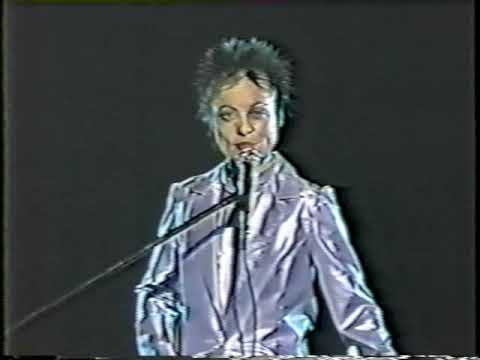

Take the music of David Byrne and Laurie Anderson. Early postmodern theory likes to think of them as nihilists or relativists, bricoleurs in the bush of ghosts. Laurie Anderson’s “O Superman” features a repeated sample of her voice and a sinister series of recorded messages. This voice typifies postmodern art materials: forms of incomprehensible, unspeakable existence. Some might call it inert, sheer existence--art as ooze. It’s a medium in which meaning and unmeaning coexist. This oozy medium has something physical about it, which I call ambience.

"Ambience" is a loaded, little word at best. You wouldn’t be alone if the first thing that comes to mind upon reading the word is a thoughtful soundscape by Brian Eno. In Ambient Commons: Attention in the Age of Embodied Information (MIT Press, 2013), Malcolm McCullough reclaims the word for our hypermediated surroundings. Claiming that we’ve mediated aspects of our world so well that we’ve obscured parts of the world itself. Looking through the ambient invites us to think about our environment–built, mediated, situated, or otherwise–in a new way. McCullough asks, "Do increasingly situated information technologies illuminate the world, or do they just eclipse it?” He adds on the book’s website, "Good interaction design reduces the 'cognitive load' of artifacts. It also recognizes how activities make use of context, periphery, and background. But now as ever more of the human perceptual field has been engineered for cognition, is there a danger of losing awareness of how environment also informs?" How much can we augment before we begin to obscure? How far flat can we press the extremes of our world?

Canadian theorist Arthur Kroker once described the mediated spirit of the 1990s as a "spasm": everything floating and flickering, oscillating and isolating, what Bruce Sterling describes as a "state when you feel totally hyper and nauseatingly bored. That gnawing sense that we're on the road to nowhere at a million miles an hour." Since the 1990s, the feeling has expanded via media technology: ubiquitous networks and screens, social media, mobile devices. In response to this environment, a weird detached irony has become our default emotional setting. David Foster Wallace called it "Total Noise": an all-consuming cultural state that "tends to level everything out into an undifferentiated mass of high-quality description and trenchant reflection that becomes both numbing and euphoric." It's information anxiety coupled with complete boredom. What happened to the chasm between those two extremes? I won’t resist the academic tendency to turn binaries into the opposite ends of a spectrum. We have to in order to make room in the space between them.

In her song, “The Language of the Future,” Laurie Anderson says,

Always two things

switching.

Current runs through bodies

and then it doesn't.

It was a language of sounds,

of noise,

of switching,

of signals.

It was the language of the rabbit,

the caribou,

the penguin,

the beaver.

A language of the past.

Current runs through bodies

and then it doesn't

On again.

Off again.

Always two things

switching.

One thing instantly replaces

another.

It was the language

of the Future.

Anderson calls this toggling of opposites a "system of pairing." Similarly, William Gibson writes, parenthetically, "(This perpetual toggling between nothing being new under the sun, and everything having very recently changed, absolutely, is perhaps the central driving tension of my work)." That binary belies a bulging, unexplored midsection. The space between that switch from one extreme to the other consumes an important aspect of technological mediation and our current state of being.

For example, a skeuomorph is a design element that remains only as an allusion to a previous form, like a digital recording that includes the clicks and pops of a record player, woodgrain wallpaper, the desktop metaphor, or even the digital page: It’s obsolete except in signifying what it supplants. As theorized by N. Katherine Hayles, the skeuomorph exploits "a psychodynamic that finds the new more acceptable when it recalls the old that it is in the process of displacing and finds the traditional more comfortable when it is presented in a context that reminds us we can escape from it into the new." Skeuomorphs mediate the space between a familiar past and an uncertain future, bridging the new and the old, translating the unknown into the terms of the known by reimagining it in a reassuringly familiar guise. Skeuomorphs bridge the space between the extremes, obscuring the transition, and that is their purpose when it comes to adapting people to new technologies. They soften the blow of the inevitable upgrade, "reduce the 'cognitive load'," as McCullough puts it. But every new contrivance augments some choices at the expense of others. What we lose is often unknown to us.

We find our mediated selves by pulling these extremes apart. If skeumorphs smooth out the edges of the extreme, the in-between is all smooth and soft. As with a cramped muscle, the solution to Kroker’s metaphorical spasm is to stretch it out. All the way out.

“City Wall,” Helsinki Institute for Information Technology, 2007.

"It’s John Cage’s birthday," writes Laurie Anderson on September 5, 2003 in her book Nothing in My Pockets (Dis Voir, 2009), “We listen to Cage reading from his own work. He tells the famous story about when he was in an anechoic chamber, a completely silent room. And he heard two sounds. One was high and one low. As it turned out, the high sound was his nervous system, and the low sound was his blood.” These are two more extremes we live in between. Two more extremes with ambience in between.

"Ambience points to the here and now," Tim Morton continues, "in a compelling way that goes beyond explicit content… ambience opens up our ideas of space and place into radical questioning." Just as poetry calls attention to language, ambience calls attention to place, the here we’re in and the now we're experiencing, bringing the background into the fore. Ambience takes the extremes of anxiety and boredom -- of nothing changed and everything new -- and stretches them into an inhabitable environment, into a now worth knowing.

The Medium PictureThe above is an edited excerpt from my book-in-progress, The Medium Picture, which is forthcoming from Zer0 Books.

“This book looks wonderful!” says Laurie Anderson herself.

As always, thank you for reading, responding, and sharing.

More soon,

-royc.

August 17, 2022

A Bad Miracle

"I know you all think you live in all the times at once, everything recorded for you, it’s all there to play back. Digital. That’s all that is, though: playback. You still don’t remember what it felt like." – Shinya Yamazaki in William Gibson's All Tomorrow’s Parties

While Jordon Peele's Nope (2022) is many things--a modern take on the classic monster movie, a study of spectacle, a comment on our relationship with nature, a reminder of the erasure of the Black presence in cinema--it's also a critique of our media-saturated society. My interest in media drew me in to that aspect of the film over any of the others. If you've seen the trailer, you know that the main characters are Hollywood horse wranglers, descendants of Alistair E. Haywood, the black jockey in Eadweard Muybridge's 1878 series of photographs of a horse running, one of the first motion pictures ever recorded. The technological mediation of experience is less of a theme of the movie and more of a condition of the environment it's set in.

[Please note: If you haven't seen Nope, but plan to, there are spoilers galore below.]

I first started thinking about technological mediation in high school. A friend of mine had rented a video camera, and we were making goofy videos with it. In one of the shots on one of those VHS tapes, there’s a close-up view of a photocopied picture of me in a Malcolm X pose that I had pinned on the bulletin board in my room. Watching that tape on my parents' VCR, I remember thinking about the layers in that image: It was grainy playback on a cathode ray tube of a magnetic tape recording of video imagery of a manipulated photocopy of a photograph of me imitating one of my heroes. Thinking through the layers of that mediation stuck with me.

There's a scene in Nope where former child star Ricky "Jupe" Park (Steven Yuen) is explaining to Emerald (Keke Palmer) and O.J. Haywood (Daniel Kaluuya) what happened during the “Gordy’s Birthday” episode of the sitcom Gordy's Home when a chimpanzee, finally set off by birthday balloons popping, ravaged the set, killed most of the cast, and maimed his co-star. Intercut with clips from the massacre, Jupe tells the story by describing a Saturday Night Live sketch in which Chris Kattan plays the rampaging Gordy. We never actually see the fictitious SNL sketch.We're watching Yuen play Jupe in describing a sketch spoofing a sitcom in a movie. Foreshadowing aside, the layers in this scene struck me in the same way the photocopied image described above did: one event filtered through one medium after another before it is experienced. With all of our screens and things, we take such layers for granted. Ironically, this is one of the scenes in the movie least laden with the apparatus of film.

In Andrew Patterson's The Vast of Night (2019), phone operator Fay Crocker (Sierra McCormick, pictured above) and radio DJ Everett Sloan (Jake Horowitz) come across an errant frequency on the airwaves that turns out to be alien in origin. Like Peele, Patterson layered the movie with references and homages to other science fiction classics. The call sign for the radio station Everett works at is WOTW, which stands for "War of the Worlds," the classic H.G. Wells book that became the classic Orson Welles radio play. There is a Twilight Zone motif that runs through the story via an introductory voiceover and intermittent TV screens. The tiny New Mexico town the story is set in is called Cayuga, which was the name of Rod Sterling's production company. Peele, of course, has his own connections to Sterling's Twilight Zone, and like the rest of his movies, Nope has its own nods to the nerds (e.g., a Northern Exposure hat, "Circle J" trailer, 6:13, Angel's Earth, The Jesus Lizard, and Rage Against the Machine t-shirts, etc. You can read about those elsewhere online).

As The Vast of Night unfolds, telecommunication and recording devices abound: Fay's new tape recorder, the telephone switchboard, the radio station, old magnetic tapes, an old camera, etc. The presence of the aliens is discovered through some of these, and others are used in failed efforts to capture evidence of their visit.

Recording devices are rife in Nope as well, mostly those related to filmmaking, capturing action in motion. Cameras are everywhere: movie cameras, security cameras, cellphone cameras, digital cameras, and even an old flash camera in the bottom of a well. The eye/mouth of the "unidentified aerial phenomenon" even looks like a camera, as does the helmet worn by the TMZ motorcycle man who shows up during the climactic sequence of the movie, but is quickly vanquished by the alien, all the while begging O.J. to save his footage. Though the rest of the characters here are trying to capture and capitalize on the spectacle at hand, this motorcycle guy represents the pure tourism of the tabloid, the clickbait culture much of the internet has devolved into. He embodies Nahum 3:6, the Bible verse that opens the movie: "I will pelt you with filth, I will treat you with contempt and make you a spectacle." Those last two lines could've been Muybridge talking to his jockey on set.

In addition to lenses, screens through which to view the images captured by the cameras and windows through which to see the outside world are plentiful. The one pictured above frames a particularly poignant moment in the movie, but there are many more. Angel (Brandon Perea) announces the arrival of the alien by saying, "It's heeeeere," an obvious reference to the arrival of the ghosts via the TV screen in Tobe Hooper's Poltergeist (1982). It's a whole world seen through lenses, windows, and screens. Jupe even refers to the aliens as "The Viewers."

Em might have gotten the money shot at the end of alien battle, but it meant less to her than seeing that O.J. has survived. The medium is the bad miracle. The latent lesson of Nope is that as much as we might want to mediate the moment, to capture and capitalize on the spectacle we experience, we can't take the feeling with us.

Most of life's great scenes happen outside of lenses and screens, uncaptured by media of any kind.

More Science Fiction and HorrorThough there's nothing about Nope in it (Peele's Get Out does get a brief mention however), my newest book, Escape Philosophy: Journeys Beyond the Human Body, draws inspiration from scary science-fiction and horror movies like Nope, as well as heavy metal music. Eugene Thacker says,

"Too often philosophy gets bogged down in the tedious 'working-through' of contingency and finitude. Escape Philosophy takes a different approach, engaging with cultural forms of refusal, denial, and negation in all their glorious ambivalence."

So, if you're into any of that kind of stuff, the book is available as a beautifully menacing paperback or a FREE open-access.pdf from punctum books.

If you got yours already and feel compelled, please do tell the others. Thank you!

Thank you for reading and responding.

More soon,

-royc.

August 10, 2022

Don’t Believe the Hope

Here's a playlist I put together featuring all of the songs and artists discussed in the book, including Godflesh, Deafheaven, Wolves in the Throne Room, Celtic Frost, and Jawbox, among others.

Play it loud while you read this edited excerpt from the book.

Enjoy!

Don't Believe the Hope“The human race sucks. Human nature is smothered out by society, job, and work and school. Instincts are deleted by laws. I see people say things that contradict themselves, or people that don’t take any advantage to the gift of human life. They waste their minds on memorizing the stats of every college basketball player or how many words should be in a report when they should be using their brain on more important things. The human race isn’t worth fighting for anymore.” — Eric Harris, journal entry, May 6, 1998 [1]

“These premonitions of disaster remained with me. During my first days at home, I spent all my time on the veranda, watching the traffic move along the motorway, determined to spot the first signs of this end of the world by automobile, for which the accident had been my own private rehearsal.” — James in J.G. Ballard, Crash [2]

“Through fiction we saw the birth

Of futures yet to come

Yet in fiction lay the bones, ugly in their nakedness

Yet under this mortal sun, we cannot hide ourselves.”

— Isis, “In Fiction” [3]

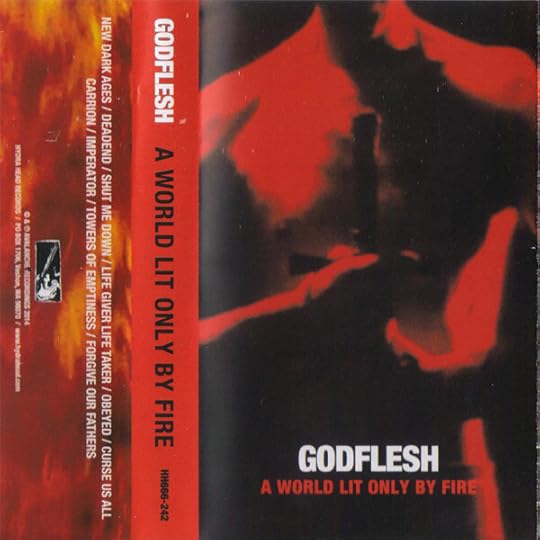

“My first love was science fiction films and the music that went along with them,” Justin K. Broadrick of Godflesh says. “My next love was horror movies, and I became fixated with the brutal, dark, and brooding sounds that went along with those as well.” [4] Godflesh’s 2014 reunion record, their first release in over a decade, is called A World Lit Only by Fire. The title evokes a flaming planet, nations and nature scorched in ruin. It’s actually a reference to a book by the same name by William Manchester about the darkness of the Middle Ages. [5] Both visions work well for Godflesh’s sound: it's dark, brutal, and could have come from a tumultuous past or a post-apocalyptic future. The hard, cold sound could be bones or stones as easily as it could be bricks or concrete blocks.

"Have you ever participated in genocide?" was the question on one of the forms Broadrick filled out on his first trip to the States after 9/11. “I always said Godflesh was, to some extent, protest music. It comes from an anarcho-punk background.” Then, echoing Columbine High School gunman Eric Harris above, he adds, “but after all the idealistic sloganeering and stuff, I sort of went the opposite way. I started to feel like the human race wasn't worth saving after all.” [6] As he sings on “Life Giver Life Taker” from A World Lit Only by Fire, “the dying sun / Is all ours / It will reclaim / Our fallen earth.” [7]

Future-minded science-fiction writers have recently been comparing the dearth of mentions of the twenty-second century so far in the twenty-first to the many mentions of the twenty-first at the same point last century. [8] It is as if we can’t even imagine our future anymore, but dystopic doom was around back then, too. “I abhor humanity,” Birkin says to Ursula in D.H. Lawrence’s 1920 novel, Women in Love, “I wish it was swept away. It could go, and there would be no absolute loss, if every human being perished tomorrow. The reality would be untouched. Nay, it would be better.” [9]

I distinctly remember an episode of The Twilight Zone I watched as a kid. It was called “Time Enough at Last” and starred the late Burgess Meredith. I don’t remember all of it, just the end: there’s a man, a bibliophile, the last person left on earth, and he’s ecstatic because he’s surrounded by books, mounds and mounds of them. He finally breaks his reverie in order to get started reading. Then he breaks his glasses.

The trepidation of that tragic moment, recombinant with worries of the apocalypse, was a seed planted in my head. And more than any other Cold War-era image of imminent destruction splashed on the television during my childhood, the nerd in me nurtured that single idea, that the apocalypse seemed inevitable, and it did not look like a particularly good time. In fact, it looked like a tailor-made, personal purgatory.

Barry Brummett writes that apocalyptic orators “claim special knowledge of a hidden order, to advise others to make great sacrifices on the basis of that knowledge, even to predict specific times and place for the end of the world.” [10] In spite of The Twilight Zone episode, I’ve always considered myself more concerned with my own demise than with the end of the word, but the latter is clearly hanging heavy in the mass-mind. Brummett also writes that the strategy of apocalyptic rhetoric is “to respond to a sense of chaos and anomie, whether acute or potential, with reassurances of a plan that is ordering history.” [11] Between looming pandemics, postponed human holocaust, and all the other global weirding, there are certainly those who would have us believe that our doom is imminent. As far as the darker strains of heavy metal music are concerned, we deserve the anxiety, as it’s likely our own fault.

This Mortal Soil

As human population continues to grow, humans are more likely to be used as a resource, raw materials for any use whatever. Moreover, the human rights in question diminish as the resources grow as well. In what Broadrick calls the “constant repetition of existence,” [12] we are the mistake that keeps on mistaking, mistaking ourselves as exceptional, mistaking ourselves as unique, mistaking ourselves as important. Even when we recognize ourselves as fallible, we still make more; the crumbling façades of buildings and the crumbling flesh of bodies.

Humanity doesn’t scale, and human nature is a farce. People will do what people will do, but we will rarely surprise you. That complete lack of surprise is all that could be called human nature. The sad predictability of the species is its nature. As Eugene Thacker puts it, “on the one hand we as human beings are the problem; on the other hand at the planetary level of the Earth’s deep time, nothing could be more insignificant than the human.” [13] Where posthumanism is most often associated with the biotechnical augmentations of cyborgs discussed before, fixing us up rather than following after we’ve gone, this is the posthumanism of extinction. [14]

In Alan Weisman’s 2007 book, The World Without Us, which speculates what life on Earth will like after humans cease to exist, he describes us as senders rather than receivers of signals, and that radio waves dispatched and drifting through space will be our final legacy. The human brain is also a transmitter, broadcasting electric impulses at very low frequencies that some believe can be focused to exact actions at a distance. “That may seem far-fetched,” Weisman writes, “but it’s also a definition of prayer.” [15]

On a more grounded note, David Leo Rice writes,

absurd as this hope surely is, I wonder if there might be a grain of truth in it. Since we, too, are creatures of the earth, made of earthly materials (as are our digital devices), perhaps there is something in our nature that can reach beyond our limited time as humans, and partake in the larger cycle of dust returning to dust. Perhaps some part of the consciousness of the earth itself exists within us, and will go on existing. [16]

Weak transmitters, antennae for sound, or just sentient meat, how ever we seek a way beyond them, we are bound by our bodies: malleable yet mortal, elastic yet earthbound. We are soil as much as we are souls. [17] The dust of this planet is people. [18]

Escape Philosophy: Journeys Beyond the Human BodyThe above excerpt is from my new book, Escape Philosophy: Journeys Beyond the Human Body. Get you an open-access .pdf or a lovely paperback from punctum books!

As always, thank you for reading, responding, and sharing.

More soon,

-royc.

Notes for the excerpt above:

Peter Langman, ed., “Eric Harris’s Journal,” School Shooters .Info (October 3, 2014).

J.G. Ballard, Crash: A Novel (London: Jonathan Cape, [1973] 1985), 50.

Isis, “In Fiction,” on Panopticon [LP] (Los Angeles: Ipecac Records, 2012).

Quoted in Garth Ferrante, “Godflesh Explains ‘Selfless’’s Song Titles,” Godflesh.com, August 1994, https://godflesh.com/articles/int2.txt.

See William Manchester, A World Lit Only by Fire: The Medieval Mind and the Renaissance: Portrait of an Age (New York: Little, Brown & Co., 1992).

Quoted in Jason Heller, “Justin Broadrick of Jesu,” AV Club, April 5, 2007, https://film.avclub.com/justin-broadr....

Godflesh, “Life Giver Life Taker” on A World Lit Only by Fire [LP] (London: Avalanche Recordings, 2014).

See Abraham Riesman, “William Gibson Has a Theory About Our Cultural Obsession with Dystopias,” Vulture, August 1, 2017, https://www.vulture.com/2017/08/willi... SCI-Arc Channel, “Bruce Sterling & Benjamin Bratton in Conversation,” YouTube, November 5, 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z0__x....

D.H. Lawrence, Women in Love (New York: Thomas Seltzer, 1920), 143.

Barry Brummett, Contemporary Apocalyptic Rhetoric (New York: Praeger, 1991), 87.

Ibid.

Quoted in Jason Heller, “Justin Broadrick of Jesu,” AV Club, April 5, 2007, https://film.avclub.com/justin-broadr.... Douglas Coupland calls it “Strangelove Reproduction,” that is, “having children to make up for the fact that one no longer believes in the future.” Douglas Coupland, Generation X: Tales for An Accelerated Culture (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1991), 135.

Eugene Thacker, In the Dust of This Planet: Horror of Philosophy, Volume 1 (Winchester: Zer0 Books, 2011), 158.

Daniel Lukes, “Black Metal Machine: Theorizing Industrial Black Metal,” in Helvete: A Journal of Black Metal Theory Issue 1, edited by Amelia Ishmael, Zareen Price, Aspasia Stephanou, and Ben Woodard (Earth: punctum books, 2013), 71–73. See also Cary Wolfe, What is Posthumanism? (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009); Jussi Parikka, “Planetary Memories: After Extinction, the Imagined Future,” in After Extinction, ed. Richard Grusin (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2018), 27–49.

Alan Weisman, The World Without Us (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2007), 274.

David Leo Rice, “The Overlook Hotel,” The Believer, October 31, 2017, https://believermag.net/logger/overlook/. He continues, “to believe this is to believe in an afterlife of time, rather than space: to believe that human consciousness, once it has become disembodied, will not travel upward or downward to heaven or hell, nor into space as radio waves, but rather that it will linger here on earth, as earth, even when that earth is transformed into a planet that, if we were to perceive it while still human, would have to be called alien. This is the dream of the entire species being present at its own funeral.” As Roberts puts it, “the end is final, and yet it also represents a strange new beginning.” Adam Roberts, It’s the End of the World, But What Are We Really Afraid of? (London: Elliott & Thompson Limited, 2020), 9. See also Timothy Morton, Ecology Without Nature: Rethinking Environmental Aesthetics (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2010).

As William Bryant Logan writes, "human bodies belong to and depend on dirt. We spend our lives hurrying away from the real, as though it were deadly to us. But the soil is all of the earth that is really ours.” William Bryant Logan, Dirt: The Ecstatic Skin of the Earth (New York: Riverhead, 1995), 97.

Like much of the rest of this book, this final line owes its existence to both McKenzie Wark and Eugene Thacker. It combines and pays homage to the last lines of Wark’s Dispositions (Cromer: Salt Publishing, 2002) and Thacker’s In the Dust of This Planet: Horror of Philosophy, Volume 1 (Winchester: Zer0 Books, 2011).

August 3, 2022

Exit Interview: Marnie Ellen Hertzler

Ostensibly making a documentary, Hertzler manages to capture a mix of both pre-apocalyptic dread and post-apocalyptic glee. The result is a delirious detour through the chaos and contradictions of coming of age in a future that’s already ending. The cast of characters listed above and the setting—as desolate and demanding as Tatooine or Arrakis—make Crestone a mesmerizing study of people out of place, a whole subculture uprooted and relocated on the edge of the end of everything.

Hertzler is currently in production on her second feature called Eternity One about a disappearing island community.

How much of Crestone was planned beforehand?

Much of it was planned. We only had 8 days to shoot so I wanted to be sure I had some kind of structure for those 8 days so they wouldn't slip away. The guys and I had scripted some scenes together and I had roughed out a narrative through-line. The best parts in the film just happened on their own. It is nice to be able to work so freely that, when needed, you can bring the happenstance to the front. Documentary isn't real, and Narrative isn't fake. I wanted to lean into that notion and planned to do so.

Did you plan to be a part of the film?

I forget if I had planned to be a part of the film. Probably. It seems so long ago now. For many of the early cuts I wasn't in it at all. Those cuts were nice, but they weren't the film I wanted to make. So much of the film is about the experience of making it, so putting me in there was necessary to communicate that.

Did the movie turn out anything like you were expecting?

No. But to be fair, I had no expectations at all, and I worked hard to maintain the zero expectations. I did know we would at least come home with a couple of music videos and maybe a short. But somehow, we were able to dig out a feature film.

The juxtaposition of high-desert communal brotherhood with Soundcloud raps is compelling but also haunting. There are moments in the film when it really does feel like the world is ending. Did it feel that way out there?

The world was ending, in a way. It always feels like the world is ending to me wherever I go. But, yes, in Crestone in particular. The desert is terrifying and electric. Everything is loud, silent, large, minuscule all at the same time. When you go to sleep at night it feels like you never know what you will wake up to the next morning. But also, we build worlds within our relationships and the love we create with other people. Those worlds are so tenuous and delicate.

Who was that one dude who just showed up out there?

The guy chopping wood? That's Huckleberry. He's a gem. I love that guy. He has the worst jokes, best laugh, and a very buttery southern accent. He's a very talented model. He was living in Denver at the time and had become friends with some of the guys. He heard we were shooting a movie. Sadboy showed me his Instagram while we were prepping to come out there and I obviously wanted to meet him. Lucky for me, he decided to show up.

What's next for you?

I'm working on a new feature film now about Transhumanism and the Chesapeake Bay, exploring the many ways we seek salvation.

[This interview is an excerpt from the pilot issue of DISCONTENTS, which is now available to order. See below!]

DISCONTENTS:The pilot issue of DISCONTENTS features the interview with Crestone director Marnie Elizabeth Hertzler above, as well as stories on Ceremony, Hsi-Chang Lin a.k.a. Still, and Unwound; interviews with emcee Fatboi Sharif and Coherence director James Ward Byrkit; pieces by Cynthia Connolly, Spike Jonze, Andy Jenkins, Timothy Baker, Greg Pratt, and Peter Relic; cover art by Tae Won Yu, layouts by Patrick Barber and Craig Gates, and drawings by me, Zak Sally, and Marcellous Lovelace.

It's 50 solid pages of good stuff about good stuff. Get yours!

Abandoned Accounts is One Year Old!One year ago, my first collection of poems, Abandoned Accounts, was release as a part of the First Cut series. To celebrate, the lovely and talented poet HLR did this interview with me for her site, Treacle Heart. Here's an excerpt:

When the COVID lockdown started, I found it difficult to focus on the larger projects I had in progress. In the months before, I’d started writing silly little poems about odd memories I had, tiny stories that didn’t fit anywhere else. I went back to those when I couldn’t think any larger. I eventually moved on to short stories and finally back to book-length writing, but not before I amassed a small collection of fitful, misfit verse.

Abandoned Accounts has those silly memories I started writing down, including reflections of walks in the woods at my parents’ house in the hinterlands of southeast Alabama, encounters with favorite bands and somewhat famous people, tales of travel and intrigue, and a few stray poems from as far back as 1990.

Many thanks to HLR and the whole First Cut crew. Read the whole interview here.

As always, thank you for reading, responding, and sharing.

Hope you're well,

-royc.