Roy Christopher's Blog, page 18

April 9, 2021

Bad Flag: The Dutch Angle

This time around I’m offering a short story.

Maybe you can relate to this: When the lockdown started a year ago, I found it difficult to focus on anything very big. All of my writing projects seemed both intractable and pointless. My attention was reduced to writing poems, flash fiction, and book reviews. Slowly, the pieces I was able to concentrate on grew to something almost normal.

The following is one of the pieces I’ve written in the past year. It’s several short articles about and interviews with a fictional band, compiled to accompany a boxset of their discography. While Bad Flag doesn’t exist, they are very real. Maybe you’ll recognize them.

This story is dedicated to the memory of Sam Jayne.

[Note: The following documents are included in the liner notes to Bad Flag’s history-spanning boxset, Dutch, released by Bright Little Light in 2019.]

a.image2.image-link.image2-940-1016 { padding-bottom: 92.51968503937007%; padding-bottom: min(92.51968503937007%, 940px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-940-1016 img { max-width: 1016px; max-height: 940px; } Fiery Tale: A Brief History of Bad Flag

a.image2.image-link.image2-940-1016 { padding-bottom: 92.51968503937007%; padding-bottom: min(92.51968503937007%, 940px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-940-1016 img { max-width: 1016px; max-height: 940px; } Fiery Tale: A Brief History of Bad Flag“A work of art has to exist in a world as an object, as real as the sun, grass, a rock, water, and so on. It must also possess a slight error. In other words, to be right, it has to be a little bit wrong, a tad strange, and thereby, truly real.” — Kharms

“They were literally the best,” says one fan with the measured reverence usually reserved for religious worship. “It’s really too bad more people don’t know about them.”

“No, it’s not,” another counters. “I’m glad no one knows about them. People ruin things.”

The latter fan expresses the prevailing attitude of the underground’s old guard. It’s a mixture of ownership, selfishness, and elitism that says, This is ours, and you can’t have it. You don’t deserve it.

Whether or not you agree, there is a certain cachet that is diminished when something gets too big. When everyone knows about a cultural phenomenon, its allure is lost. Cool doesn’t scale.

Though they were once approached by the A&R of a major label, Bad Flag were never in danger of getting too big.

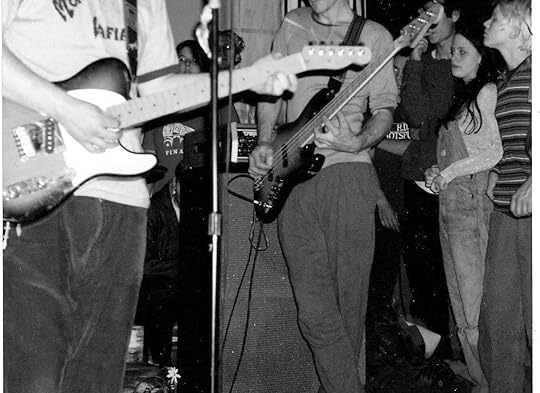

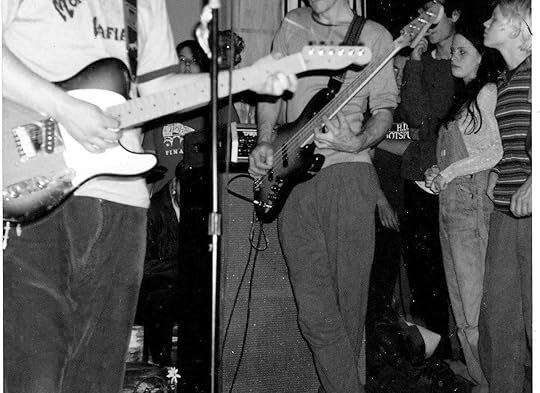

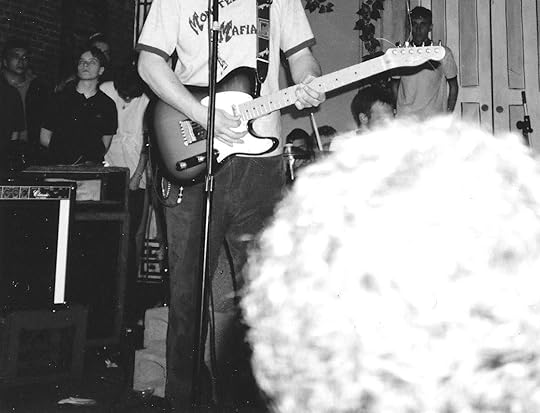

“I saw them open for someone at the Off Ramp in Seattle in 1994,” Greg Foreman tells me. “I can’t remember who it was. They were on their way out by then I’ve been told, but you certainly couldn’t tell by the way they played. They erased the headliner from my head!” Foreman worked artist and repertoire for Retropolis Records from 1987 to 1995. At the time Retropolis was a subsidiary of one of the big five American record labels and had recently signed a wave of successful indie bands, primarily at the behest of Foreman. “On their way out or not, they’re still easily the best live band I’ve ever seen—and I’ve seen a lot of bands... The records really don’t capture the lightning of their live show.” He trails off. “Hands down. The best.”

Bad Flag broke up in December of 1994, so Foreman saw one of their last shows. The records he’s referring to, of which he has two, are a scant series of seven-inch singles the band put out. Depending on who you ask, the sum of the band’s output is either three or five seven inches, one demo cassette, a rehearsal tape, and two live bootlegs. Some say the demo is just a bad copy of their early singles, but no one can explain the extra song that only appears there.

“I picked up the only two records they had with them at that show,” Foreman continues. He pulls the two records out of a steel box to the side of his racks of vinyl. I try to see what else is in there, but he quickly closes it. He holds out the two pristine artifacts, both sheathed in thick plastic sleeves. “I played them both only once, and then only to record them to tape. I mean, okay, I had to play ‘All the Way Down’ twice because I forgot to unpause the recording, but that’s it.”

“All the Way Down” is the third act, the B-side to the three-song seven inch EP, Man Amok (Bright Little Light, 1995), which marked a conceptual turn in the band’s songwriting. Acts 1 and 2, “Where the Day Goes to Die” and “Good God Gone Bad,” are on the A-side. It’s probably their best-known trilogy of songs. It was their last, and the only recording not released by the band themselves—or without their knowledge. The change is subtle but significant enough to make one wonder what would have come next.

“They didn't really seem interested in selling them,” adds Foreman “and when I told them who I was, they packed up and retreated backstage. I didn’t even get a chance to offer them a deal.”

a.image2.image-link.image2-884-1216 { padding-bottom: 72.69736842105263%; padding-bottom: min(72.69736842105263%, 884px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-884-1216 img { max-width: 1216px; max-height: 884px; } Waving Radiant: Who is Bad Flag?

a.image2.image-link.image2-884-1216 { padding-bottom: 72.69736842105263%; padding-bottom: min(72.69736842105263%, 884px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-884-1216 img { max-width: 1216px; max-height: 884px; } Waving Radiant: Who is Bad Flag?If ever there were a band deserving of the designation power trio, it is Bad Flag. Their music is a mathematics, an algorithm. It’s a process in progress that they are neither enjoying nor enduring but exacting, like an angry surgeon. It’s as heady as it is heavy. The three in question are the affable oaf, Dutch McNeal (drums), the cryptic yet quotable Sam Sports (bass, vocals), and the even-keeled Will Wilson, Jr. (guitar, backing vocals).

Don’t let their name and logo (the skull and crossbones of the Jolly Roger) fool you, their lyrics are written and sung by a young man worldly beyond his home and wise beyond his home-schooling. In one song, he can go from lines about “the stress-free skin of the unperturbed” to a string of expletives lacking rhyme, rhythm, and reason. One reviewer wrote of their first 7”, “No one should have it, and no one should be without it. That’s how controversial it is.”

Bad Flag was formed in the forges of Chicago during a particularly hot time. “Sam and I have known each other since middle school,” Will tells me over the phone. “We met Dutch in college.” By college, he means the University of Chicago. After forming, dissolving, and playing in several other bands throughout school in the Chicagoland suburbs, Sam and Will moved to Hyde Park together, hell bent on starting something new. Paul Morley’s summation of Joy Division from June of 1980 could just as easily have been written about Bad Flag:

Good rock music—the palatable, topical stuff—is an amusement and an entertainment. But the very best rock music is created by individuals and musicians obsessive and eloquent enough to inspect and judge destinies and systems with artistic totality and sometimes tragic necessity; music with laws of its own, a drama of its own. The face of rock music is changed by those who introduce to the language new tones, new tunes, and new visions.

“We had a vision that never manifested in any of the other bands we’d been in,” says Sam.

“It wasn’t like we were trying to start a revolution,” Will adds, “but we were trying to realize something we hadn’t heard anywhere else, for ourselves.” Their vision included starting with the basics—vocals, guitar, bass, and drums—and building up. “We wanted the constraints of a regular band,” says Will, “but we wanted to push on them as hard as we could.”

And push they did. Dutch seemed the missing piece. His drumming is propulsive, steady yet organic. As precise as he could be, Dutch was not a machine. He was an animal.

Sam’s songwriting might be the thing everyone remembers or writes about, but Will and Dutch are essential. “Bad Flag is the three of us,” Sam insists. “And no one else.”

Bad Flag emerged on the Chicago club scene seemingly fully formed. Their first show, opening on a three-band bill that included their heroes the Jesus Lizard and local powerhouse Tar at the Lounge Ax in 1991, was plagued with sound problems, but they played almost flawlessly. It was a performance that didn’t go unnoticed.

“We weren’t ready for them,” says Tar’s John Mohr. “I thought we were bound by tension! Those guys seem ready to snap the second they plug in.”

“There was a lot of amazing music in our circles at the time,” Steve Albini remembers. “Tortoise, Tar, Naked Raygun, the Jesus Lizard… Brise-Glace, anything with David Grubbs in it, or Jim O'Rourke… It was hard to stand out, but Bad Flag was a revelation.” Albini ended up recording all of their official releases. “I spent every session trying to recapture the magic of that first show,” he claims.

“I think he came pretty close a couple of times,” says Russ Corey, owner of Bright Little Light, who put out the band’s last 7” record. “Even on the later material, which we were over-the-moon to release, where they stretched out more than ever before… What a band…”

Though those few recordings are bought and sold like gold, everyone knows these rare documents don’t capture the caged beast that was Bad Flag live. In between that first Lounge Ax show in 1991 and the posthumous Man Amok 7” in 1995, there were two brief tours in the Anything Grows flower shop van. In 1993, Bad Flag headed east, and in 1994, they headed west.

“The tour in 1993 was mainly to go to DC,” Will tells me. “We felt like, outside of Chicago, Olympia and DC were where our kindred bands lived. So, we booked that tour aiming to spend a couple of days in DC. We’d sent Ian [MacKaye of Fugazi and Dischord Records] our records, and he got us on a show at the 9:30 Club with Jawbox.” They also played with Five-Eight at the 40 Watt in Athens, Mary’s Pet Rock at the Nick in Birmingham, Polvo at the Cat’s Cradle in Carborro, and scattered shows by themselves in between.

Their second tour was the other direction. Setting out for the Cascades, they seem to have found a second family in the Northwest.

“We bonded instantly with a lot of the bands out there,” Will says. “I mean, we have at least as much in common with Hush Harbor and 30.06 as we do with Slint and Gastr del Sol.” It’s true. As much as Bad Flag fit in with the Chicago bands they played with, it’s not difficult to imagine them coming up in Portland, Olympia, or Seattle.

“Some Velvet Sidewalk? Unwound? Lync?” Dutch added. “We could’ve easily been on K Records or Kill Rock Stars and no one would’ve batted an eye.”

The band ended with that tour. They announced their break-up before they got back. The final performance at the Fireside Bowl in Chicago was an emotional affair. Thankfully, someone recorded it. Like seemingly every show, they played it like it was their last. This time they were right.

Bad Flag Interview, March 17, 1993:The following brief interview was conducted shortly after Bad Flag released their third seven-inch record, “Get Off the X” b/w “Dogspine” (Vortex Shedding, 1993), and just before they went on their first tour.

So, are those your real names?

Dutch: “Yep.”

Will: “They’re real enough.”

“Sam Sports,” really? You don’t seem like the sporting type.

Sam: “’Irony’ is my middle name.”

Dutch: “It is!”

Will: “He legally changed it.”

Sports seems like more of a Dutch McNeal thing.

Will: “He played in high school.”

Dutch: “Yep. Linebacker.”

What about the band’s name, “Bad Flag”?

Will: “That was also Sam’s doing.”

Dutch: “Yeah, blame Sam.” [laughs]

Sam: “We were young when we started. I know you can’t hear any Bad Religion, Bad Brains, or Black Flag in our sound, but those were my favorite bands when I first started thinking about making music myself.”

Will: “I remember, you were so excited. You couldn’t believe no one had taken that name!”

Sam: “Yeah, it seems silly now of course, childish even, but the meaning of the name has evolved for me as we’ve gotten older as people and existed and progressed as a band.”

How so?

Sam: “Just the idea of flags in general… crosses, logos, signs… We imbue these things with meaning…”

Will: “…and then the meaning gets lost.”

Sam: “Yeah, so by having a silly name and logo, we kind of avoided that, subverted it somewhat.”

Dutch: “Put it this way: If you’re not familiar with our music, and you see our name on a flier, your impression is probably not going to be accurate, and you’re not going to expect what we do.”

Sam: “By the same token you don’t want to regularly do something that looks like something else. Eventually you’ll be answering to the worst suspicions… Your symbols won’t save you.”

Speaking of signs, do you guys believe in Astrology?

Will: “No.”

Dutch: “Really, Will? You don’t think the stars and planets have any bearing on your life?

Will: “No.”

Dutch: “Then why do you go to sleep when this one is facing away from the sun and wake up when it turns back?”

Will: “Going to bed when it’s nighttime and believing in Astrology are not the same thing.”

Dutch: “Whatever.”

Sam: “No one cops so to their misgivings so easily, but they look good on the side of a bus.”

You’re about to go on your first tour. Tell me about that.

Will: “We’re headed east, to DC, then dipping south to Chapel Hill, Athens...”

Dutch: “Yeah, we’re gonna hit all the hot spots out there, stop off in Alabama to see some friends and visit my family, and then come back home.”

You have a reputation for covering some unlikely and very difficult songs, from other underground bands like Johnboy, Table, Butterfly Train, Lungfish, Scratch Acid, and of course, Big Black. How do you choose the songs you cover?

Dutch: “It’s just what we like. Sometimes it’s someone that influenced us, but it’s always a song by a band that we like.”

Will: “Yeah, especially where our contemporaries are concerned. We try to put our own spin on all of them, but yeah, it’s usually just because we like the song and the band.”

Sam: “Immolation is the sincerest form of flammability.”

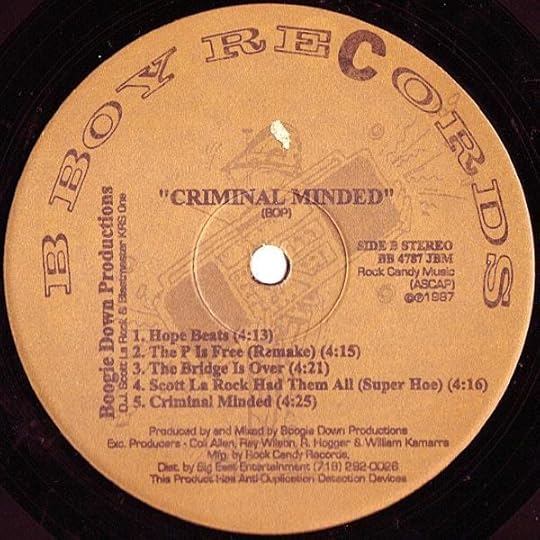

“Present Tension” b/w “Fragile Fists” (Vortex Shedding, 1991)

“Bury the Butterflies” b/w “Haunted Halo” (Vortex Shedding, 1991)

“Get Off the X” b/w “Dogspine” (Vortex Shedding, 1993)

Born with the Safety Off (Demo Cassette, 1991)

A:

“Present Tension”

“Fragile Fists”

“Bury the Butterflies”

“Haunted Halo”

B:

“Get Off the X”

“Dogspine”

“Wiser” (Coffin Break)

“Spotlight” (Candy Machine)

Rehearsal Bootleg (Cassette, 1993)

A:

“Get Off the X”

“Present Tension”

“Dogspine”

“Fiery Tale”

“Fragile Fists”

“Fish Fry” (Big Black)

“Walking the King” (Tar)

“Untitled/Entitled”

B:

“Where the Day Goes to Die”

“Good God Gone Bad”

“All the Way Down”

“Creeping Tender” b/w “Max Perlich” (Vortex Shedding, 1994)

Live from the Near-Death Experience (Last show, Fireside Bowl, 1994)

(Live Bootleg, Cassette, 1995; CDR, 1997)

“Get Off the X”

“Where the Day Goes to Die”

“Managing the Damage”

“Present Tension”

“Dogspine”

“Weightless Waitlist”

“Max Perlich”

“Bury the Butterflies”

“Gag Box” (Table)

“Fiery Tale”

“Fragile Fists”

“Untitled/Entitled”

Encore:

“Aluminum Siding” (Crackerbash)

“Bob and Cindy” (Johnboy)

“Feral Future”

Man Amok 7” (Bright Little Light, 1995)

A: “Where the Day Goes to Die,” “Good God Gone Bad”

B: “All the Way Down”

a.image2.image-link.image2-906-1184 { padding-bottom: 76.52027027027027%; padding-bottom: min(76.52027027027027%, 906px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-906-1184 img { max-width: 1184px; max-height: 906px; } Beating Hearts: An Interview with Will Wilson, Jr. and Sam Sports of Bad Flag, 2019

a.image2.image-link.image2-906-1184 { padding-bottom: 76.52027027027027%; padding-bottom: min(76.52027027027027%, 906px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-906-1184 img { max-width: 1184px; max-height: 906px; } Beating Hearts: An Interview with Will Wilson, Jr. and Sam Sports of Bad Flag, 2019Bad Flag broke up in December of 1994, and they stayed broken up. Not only was a reunion never on the table, now it’s not even possible: Their loud and lovable drummer Dutch McNeal was killed in a mass shooting in his hometown last year.

The last time I interviewed them in 1993, they were still an active and enthusiastic band. Little did any of us know that they’d break up two years later. They flared up and flared out, but they don’t come off as bitter or jaded. If you read that old interview, you may have noticed Sam’s penchant for aphorisms. If he seemed a little too ready with a handy quotation, that hasn’t changed either.

Bright Little Light is hereby releasing a full Bad Flag discography. The 3-CD, 5-LP Dutch includes remastered versions of all of the band’s seven inches, a set of bonus cover versions, and a proper remaster of their last show at the Fireside Bowl in 1994. In Dutch’s honor, I caught up with the remaining members of one of the greatest bands to ever meld minds through music.

Not to start off imprudently, but looking back, some of the quotations in our previous interview seem fake. I’ve even had a few people tell me as much.

Will: “We liked messing with interviewers, especially Sam or where Sam was concerned. He was the lyricist, so people relate to the words and want to know more. We shielded him to protect that, and sometimes it got out of hand.”

Sam: “Yeah, at some point, you’re not a trickster, you’re just a troll.”

That’s a distinction not a lot of people are going to take the time or effort to make.

Will: “Even still, it becomes something else.”

Sam: “Gossips never follow up.”

That’s not exactly fair.

Will: “Well, it cut both ways. There were a lot of misconceptions about us because of the way we dealt with the media, both by being loose and by being closed off. So, we paid for it.”

Sam: “With your walls up, it’s easier for someone to sneak up on you.”

I was sorry to hear about Dutch.

Will: “Thank you. Crazy days.”

Sam: “Yeah, I miss him.”

Will: “We all still talked regularly. It’s a weird world now.”

Really cool of you to name the boxset after him.

Will: “It seemed only right.”

Sam: “As younger men, I was always off in my head, and Will was all about the business.”

Will: “Dutch was the emotional center of the band.”

Sam: “He was the beating heart.”

Will: “He really was.”

Sam: “It’s in tribute to him, of course, but it also has other meanings.”

Like?

Sam: “It also means dander or trouble, going it alone… Looking at the world from a tilted perspective.”

Will: “It was also Reagan’s nickname, which I believe is where Dutch’s parents got it.”

Sam: “So, even if you didn’t know Dutch, it still has meaning.”

Speaking of going it alone, tell me about the break-up. You guys planned that ahead of time, right?

Sam: “Yeah, it was the difference between it ending and its having an ending.”

Will: “It was hard, but it had to happen. We were best friends from middle school to college, and it got to the point where we could either be in the band or continue to be best friends, but there was no way we could be both. We chose to stay best friends.”

Sam: “It’s easier meeting people than it is letting them go.”

If you were able to stay together as a band, what do you think about being a band in the current state of the music industry?

Will: “Certain parts of it are great! The ability to distribute your music online is amazing.”

And other things?

Sam: “You mean social media?”

Yeah.

Will: “Ugh. For the bands, it never ends. And as a user, it’s like the food in the refrigerator: You keep looking like you’re expecting something new to be in there, because you’re hungry. That’s what social media is. You keep checking, and it’s still the same leftovers... I’m so glad that stuff wasn’t around when we were a band.”

Sam: “I agree. It seems like a lot to maintain but complaining about how different things are now betrays a profound and malignant kind of stupid.”

Will: “We’d also have to change our name to ‘Dad Flag.’”

On the back of the Man Amok seven inch, it reads “Bad Flag supports the destruction of mankind.” That seems a little extreme, even for you guys.

Will: “That came from when we were recording. We were at Albini’s house.”

Sam: “Yeah, his girlfriend Heather was really into Norwegian Black Metal, and she had procured this Black Metal magazine from Norway called Nordic Vision. In their introduction, it said, ‘Nordic Vision supports the destruction of mankind’. It became a running joke during the sessions. It fits that record thematically as well.”

Will: “But we also just thought it was funny, so we put it on the record.”

And what about all the cover songs in the box? You guys were known for doing covers live, but where did the new recordings come from?

Will: “That was thanks to Steve. We’d always warm up in the studio with cover songs, and he’d always record them. We hadn’t planned on doing anything with them, but then it became a thing. There are even several that survived that we rarely did live.”

Sam: “One might even say a few classics.”

a.image2.image-link.image2-475-802 { padding-bottom: 59.22693266832918%; padding-bottom: min(59.22693266832918%, 475px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-475-802 img { max-width: 802px; max-height: 475px; }

a.image2.image-link.image2-475-802 { padding-bottom: 59.22693266832918%; padding-bottom: min(59.22693266832918%, 475px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-475-802 img { max-width: 802px; max-height: 475px; } How do you feel about your legacy?

Will: “I feel great about it. We get mentioned in conversations that surprise me, but it’s usually in a positive way.”

Like what?

Will: “Sometimes we’re mentioned in a certain lineage that I’m not sure we were really a part of. It’s something much bigger than we were or were intending to be. A lot of it comes from hindsight and the lack of historical context, but it also comes from an intellectual tradition of taking the wrong things seriously.”

Sam: “And rushing to shelve things in the right category according to questionable or outmoded criteria.”

Will: “Yeah, that too.”

Sam: “They’re using wine theory to analyze grapes.”

Will: “We had ambitions, and a lot of the specific goals we had in mind we achieved. We started playing live sharing the stage with our heroes, and along the way we shared stages with many more of them, from the Jesus Lizard and Tar that first night to Unwound, Hush Harbor, Engine Kid, A Minor Forest, Candy Machine…”

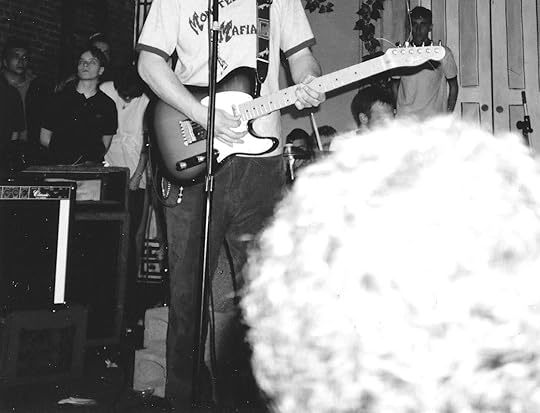

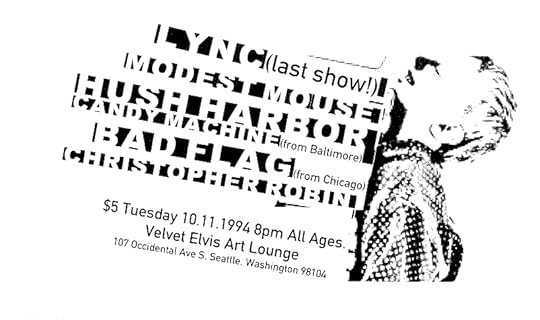

Sam: “Lync, Christopher Robin… We played with them on the same night!”

Will: “Yeah, it was at the Velvet Elvis in Seattle… Wait, wasn’t Candy Machine out there on tour too?”

Sam: “Yeah, it was us, Hush Harbor, Modest Mouse, Christopher Robin… Candy Machine, and Lync. It was Lync’s last show. James Bertram got us on that show.”

Will: “Schneider set his drums on fire.”

Sam: “That’s right… What a night! Shout out to Steve and James and Sam and Peter and all those bands.”

Will: “Remember that place we stayed in Portland the next night?”

Sam: ”With the big, brown stain on the carpet?”

Will: “Yeah, and the—”

Sam: “Our host tried to assuage our concerns by saying that it wasn’t shit, it was blood.” [laughter]

Will: “So, yeah… We played with our heroes, we put out some records, we recorded with Albini… We thought we might do a record for Touch & Go.”

Sam: “But that was never the point.”

Will: “Well, no…”

Sam: “We learned early on that all we could control was the music we were making.”

Even so, you guys are still revered as a band that maintained the underground ethos when everyone around you was groping for the brass ring.

Will: “We appreciate that, but we don’t really deserve it. I mean, this band did more than we ever expected. The records, the tours, the songs… That’s all we wanted.”

Sam: “It's easy to maintain your integrity when no one is offering to buy it.”

Will: “Besides, some people still think we were uptight curmudgeons, old men before our time.”

I mean, you guys were straight-edge, vegan teetotalers – still are! What do you say to people who think you’re no fun?

Sam: “They say that you have to know the difference between a party and a problem. We never even had a party.”

a.image2.image-link.image2-853-957 { padding-bottom: 89.13270637408569%; padding-bottom: min(89.13270637408569%, 853px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-853-957 img { max-width: 957px; max-height: 853px; } Bad Flag

Dutch

a.image2.image-link.image2-853-957 { padding-bottom: 89.13270637408569%; padding-bottom: min(89.13270637408569%, 853px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-853-957 img { max-width: 957px; max-height: 853px; } Bad Flag

Dutch

(boxset, Bright Little Light, 2019)

Disc One: Seven-Inch Discography

“Present Tension”

“Fragile Fists”

“Bury the Butterflies”

“Haunted Halo”

“Get Off the X”

“Dogspine”

“Creeping Tender”

“Max Perlich”

Man Amok:

“Where the Day Goes to Die”

“Good God Gone Bad”

“All the Way Down”

Disc Two: Covers

“Wiser” (Coffin Break)

“Spotlight” (Candy Machine)

“Aluminum Siding” (Crackerbash)

“Bob and Cindy” (Johnboy)

“Speed for Gavin” (A Minor Forest)

“Good Morning, Captain” (Slint)

“Walking the King” (Tar)

“Darjeeling” (Rodan)

“Natural’s Not in It” (Gang of Four)

“A Farewell to Kings” (Rush)

“Huck” (30.06)

“Friend to Friend in Endtime” (Lungfish)

“Windshield” (Engine Kid)

“Fish Fry” (Big Black)

Disc Three: Last Show Live, Fireside Bowl, 1994

“Get Off the X”

“Where the Day Goes to Die”

“Managing the Damage”

“Present Tension”

“Dogspine”

“Weightless Waitlist”

“Max Perlich”

“Bury the Butterflies”

“Gag Box” (Table cover)

“Fiery Tale”

“Fragile Fists”

“Untitled/Entitled”

Encore:

“Aluminum Siding” (Crackerbash cover)

“Bob and Cindy” (Johnboy cover)

“Feral Future”

Thank you for reading, responding and sharing.

Hope you’re well,

-royc.

A Résumé as Research

On December 18, 1996, I started my first online job. I remember the date because one year and one day later, the company closed its doors.

We sold software online. It sounds quaint now, but we were the first company to do it. This was back when the attitude was apocalyptic about using your credit card online. The internet was a dark, dismal place. No one out here was to be trusted. It was also when people expected software to come in a box with shiny discs and glossy instruction manuals. Customers routinely asked when they would receive these. The idea that you could download a program over the phone-lines, then install and run it on your computer without a disc was still foreign to most.

Sometime in 1997 we were purchased by another software retailer. They made their money through mail-order catalog sales and were curious about potential sales online. They bought us as a placeholder just in case this internet thing took off. When we didn’t show the returns they expected in the time they expected, they shut us down.

It sounds as weird now as downloading software did then, but this kind of turnover was normal in the dot-com era. My coworkers seemed to be split between the glib, who’d seen it all before, and the crushed, who’d harbored dreams of online fortune. We were so far ahead of other companies, many of their jobs didn’t exist anywhere else yet. As one of my friends there said, despondent after being unable to find similar work elsewhere, “I love what I do.”

I wasn’t just glib, I was stoked. I got the only severance package I’ve ever received.

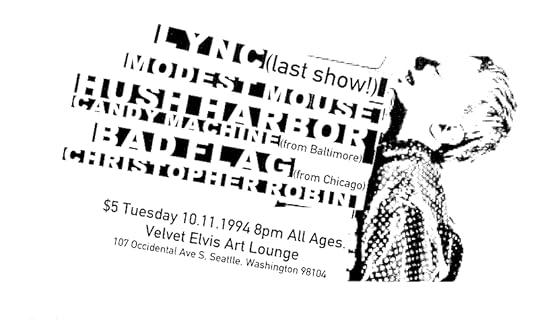

During my year and a day at that job, I got vacation time for the first time ever. So, the month before we were unexpectedly shutdown, I flew to San Francisco to work for a week at Hi-Speed Productions, the offices of Thrasher Skateboard Magazine. I’d been writing for their other magazine, SLAP, which was sort of a little brother to Thrasher, since it started. One of my friends there had just left, so there was a position open. I was vying for it, and there was nothing else I wanted to do with my newly accrued week’s vacation. A few months later, severance check in hand, I moved down there for a brief stint as SLAP’s music editor.

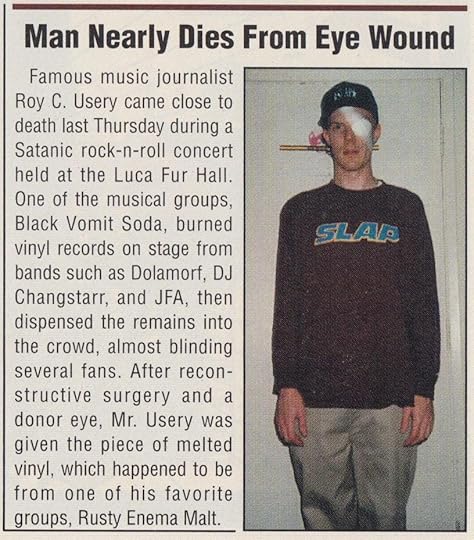

a.image2.image-link.image2-929-816 { padding-bottom: 113.84803921568627%; padding-bottom: min(113.84803921568627%, 929px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-929-816 img { max-width: 816px; max-height: 929px; } Music journalism almost killed me. Shouts out to Hassan Abdul-Wahid, Wei-En Chang, Kyle Grady, and Lance Dawes. Jake Phellps, R.I.P.

a.image2.image-link.image2-929-816 { padding-bottom: 113.84803921568627%; padding-bottom: min(113.84803921568627%, 929px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-929-816 img { max-width: 816px; max-height: 929px; } Music journalism almost killed me. Shouts out to Hassan Abdul-Wahid, Wei-En Chang, Kyle Grady, and Lance Dawes. Jake Phellps, R.I.P.Being at SLAP reminded me of my first days out of my parents’ house, those first attempts at navigating the adult world. Having grown up with an artist mom, I just assumed I’d be an artist. After trying to go to an actual art school, which involved retaking a standardized test in pursuit of a scholarship to offset out-of-state tuition, I ended up at the local community college. When it came time to transfer to a four-year institution, I was still an art major. In an attempt to monetize my waning passion for art, I chose commercial art as my area of study. I met with a professor at a school in Orlando, Florida, who flitted around his office preparing for something other than meeting with me. He told me there was no such thing as commercial art.

I tried a semester at Montevallo University near Birmingham, Alabama. As I was nearing the end of that failed experiment, I decided art wasn’t the major for me. Spurred by the social concerns of the hardcore punk and hip-hop I’d been listening to since middle school, I decided on sociology. I met with an advisor at Montevallo, who also acted as if he was readying his studio space for anything other than my presence. I ended up moving back home to finish a degree in social science.

The SLAP experience was like a second coming of age. It reminded me how my expectations had framed my future and how wrong I was again. To be accepted to school, hired for work, welcomed into a space, and then treated like your presence is nothing special is confusing. To pass the test then be treated like there wasn’t a test is confounding. To work hard to get somewhere and then be treated as if anyone there can do the work is disheartening. It felt as much my fault as anyone else’s. These were not endings, they were turns: paths that branched off from the one I thought I’d follow. The one at SLAP led me back to school.

a.image2.image-link.image2-277-1456 { padding-bottom: 19.024725274725274%; padding-bottom: min(19.024725274725274%, 277px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-277-1456 img { max-width: 1456px; max-height: 277px; }

a.image2.image-link.image2-277-1456 { padding-bottom: 19.024725274725274%; padding-bottom: min(19.024725274725274%, 277px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-277-1456 img { max-width: 1456px; max-height: 277px; } A year and a half later, I moved to Athens, Georgia to enter the University of Georgia’s master’s program in Artificial Intelligence. After extensive research, I found that their program encompassed so many of my newfound interests: cognitive science, computer science, psychology, philosophy. I was quickly in over my head. I was unprepared for the formal logic the entire program was built on. The formal logic class I was in was the fourth of a series of which I had taken none. The programming class was in a language called ProLog, which means “programming in logic.” The introductory A.I. course also required a final project written in ProLog. I was failing by midterms.

I also didn’t want to be a computer programmer, but that really wasn’t going to be a problem. The one class I never missed was the one-credit survey of all the research going on in the A.I. program and its associated disciplines. Those were all of the reasons I was drawn in the program in the first place. Those were all of the reasons I worked an extra year as a designer at an Alabama newspaper and an Army base to save up the money to go to UGA because I didn’t get in the previous year.

I bounced back into web design, and inadvertently, skateboarding. My next plan was to get a job and save up enough money to move to Austin, Texas. I had heard great things about the city, and I had a few friends living there already. After two months at a web design job in Atlanta, I got a job at Skateboard.com in San Diego.

a.image2.image-link.image2-169-900 { padding-bottom: 18.777777777777775%; padding-bottom: min(18.777777777777775%, 169px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-169-900 img { max-width: 900px; max-height: 169px; } Shouts to Chris Mullins and Tod Swank.

a.image2.image-link.image2-169-900 { padding-bottom: 18.777777777777775%; padding-bottom: min(18.777777777777775%, 169px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-169-900 img { max-width: 900px; max-height: 169px; } Shouts to Chris Mullins and Tod Swank.After another brief and uneventful stint in action sports, I was back in Seattle.

I’ve been thinking about my previous paths and branches because another one split just recently. After seven years teaching at the University of Illinois-Chicago, I took a job at a private art college in Savannah—the very art school I’d tried to get into as an undergraduate! I moved back to Georgia in the fall of 2019. I had my initial reservations but given all of the factors at the time of the decision, it was the thing to do. The new job had a dress code, way less autonomy, lots of rules anathema in academia, and no real room for growth. I lasted exactly one academic year.

Like SLAP and Skateboard.com, from the outside the school looked like the place for me. It is often difficult to convince outsiders otherwise. They see a place for you and you in that place. If it doesn’t work, then you must be the problem. You must have done something wrong. What do you mean you didn’t like working as a music editor of a skateboard magazine?! What do you mean you didn’t like writing and designing for a skateboard website?! What do you mean you didn’t like teaching at an art school?!

It just doesn’t make sense to anyone outside the situation.

You have to make sure it makes sense inside the situation.

You have to keep moving and trying until it does.

I’m still working in it.

Vicarious Life: Performing in the Fanopticon

In the first chapter of his 1992 book, Turn Signals are the Facial Expressions of Automobiles (Addison-Wesley), Donald Norman describes going to see a sixth-grade play in a relatively small auditorium. “If there had been only fifty parents present, it would have been crowded,” he writes. “But in addition to the parents, we had the video cameras.” Written some thirty years ago, this anecdote is well before the camera shrunk and merged with the mobile phone. Video cameras were cumbersome, and many didn’t yet run on batteries, hence his long-since gone concerns about space. He continues,

Ah yes, once upon a time there was an age in which people went to enjoy themselves, unencumbered by technology, with the memory of the event retained within their own heads. Today [1992] we use our artifacts to record the event, and the act of recording becomes the event.

Norman calls this need to record instead of paying attention “vicarious experiencing.” Echoing him many years later, the comedian Doug Stanhope used to do a joke about people recording his stand-up shows. As wireless networks and their bandwidth got broader and smartphones and their cameras got smaller, sharing experiences got easier and easier. Having always not only allowed but encouraged the sharing of his material online, Stanhope grew tired of people filming his performances, taking quotations out of context, as well as posting incomplete bits. “Hey, why don’t you just watch the show?” he asked. The mocking response: “Nah, I’d rather watch it on my laptop later.”

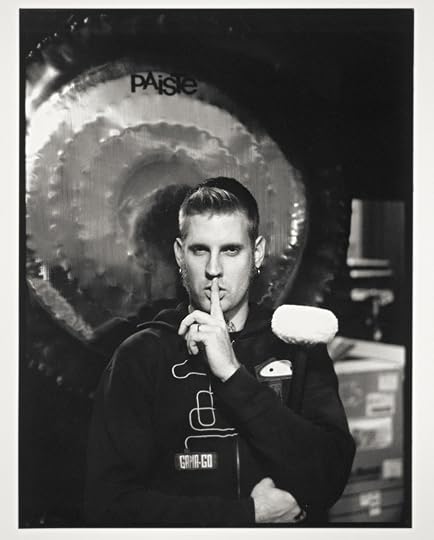

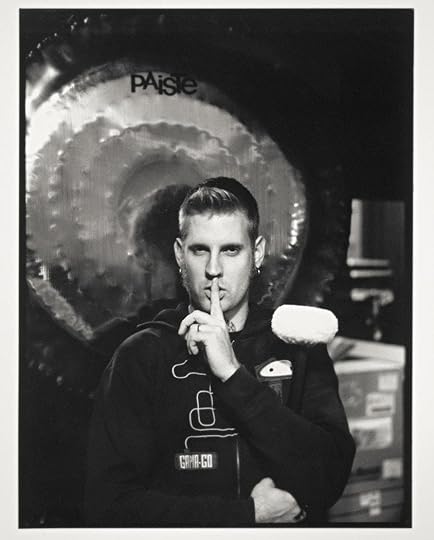

a.image2.image-link.image2-1050-844 { padding-bottom: 124.40758293838863%; padding-bottom: min(124.40758293838863%, 1050px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-1050-844 img { max-width: 844px; max-height: 1050px; } Drummer Brann Dailor is begging you to stop sharing. Photo by Jimmy Hubbard for

Revolver

during the recording of Mastodon’s Blood Mountain.

a.image2.image-link.image2-1050-844 { padding-bottom: 124.40758293838863%; padding-bottom: min(124.40758293838863%, 1050px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-1050-844 img { max-width: 844px; max-height: 1050px; } Drummer Brann Dailor is begging you to stop sharing. Photo by Jimmy Hubbard for

Revolver

during the recording of Mastodon’s Blood Mountain.On the way to record their 2006 record, Blood Mountain, with the Seattle producer Matt Bayles, Atlanta metal band Mastodon test drove many of their new songs in front of live audiences across the country. It was the last opportunity they would have to do so. By the time they were ready to record their next record, 2009’s Crack the Skye, camera-enabled smartphones and easily uploaded video made it impossible to practice in public. No more sampling a song in front of a live audience lest a lesser version be shared with the world before it’s ready.

You know how it feels when your boss or best friend asks to see something you’re working on before it’s finished. You have to make excuses about every angle you were trying and every flaw you already know needs fixing. The unfinished can be a fragile state for the creative process, and the unfinished work is only shades of its future self at best. The unfinished opens the creator to questions that the finished version would never elicit.

a.image2.image-link.image2-600-803 { padding-bottom: 74.71980074719801%; padding-bottom: min(74.71980074719801%, 600px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-600-803 img { max-width: 803px; max-height: 600px; } Deftones and iPhones in Austin in 2011. Photo by Roy Christopher.

a.image2.image-link.image2-600-803 { padding-bottom: 74.71980074719801%; padding-bottom: min(74.71980074719801%, 600px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-600-803 img { max-width: 803px; max-height: 600px; } Deftones and iPhones in Austin in 2011. Photo by Roy Christopher.Consider the same situation for comedians like Stanhope above. Jokes have to be worked out in front of audiences. The only way to truly test the wording, the phrasing, the cadence of a set-up, and the optimal delivery of a punchline is to hear a live crowd react. There’s no way to do that if you run the risk of having every joke-in-progress recorded and posted online. And having an online audience hear all of your rough drafts diminishes the final version’s impact. Everyone loses.

The invisibility of communication networks coupled with the ubiquity of cameras and screens has collapsed contexts of all kinds. Call this one the Fanopticon. Our vicarious lives notwithstanding, the inability of live performers to practice in a semi-public arena is another unintended consequence of these collapsings.

“The Fanopticon” is another brief bit from my book-in-progress, The Medium Picture. Let me know what you think.

This week I also have a movie review of Timecrimes (2007) up on Econoclash Review. Check it out.

Again, thanks for reading, responding, and sharing.

-royc.

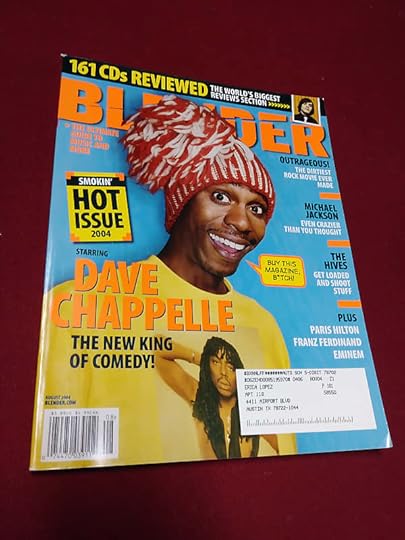

Coming to Terms with Dave Chappelle

I distinctly remember the only issue of Blender Magazine that I ever read had Dave Chappelle on the cover (August 2004). The mid-00s were the magazine format’s last peak, and there were so many of them, newsstands stretching down grocery-store aisles, colorful covers like cereal boxes. I don’t remember what prompted my purchase of this particular issue, but I read the Chappelle piece with intense interest. I’d seen some of Chappelle’s stand-up and seen him in movies here and there. I’d never seen Chappelle’s Show proper, though I’d watched clips from it online. I had friends who were huge fans though, the kind who couldn’t describe a sketch without devolving into uncontrollable laughter.

a.image2.image-link.image2-800-600 { padding-bottom: 133.33333333333331%; padding-bottom: min(133.33333333333331%, 800px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-800-600 img { max-width: 600px; max-height: 800px; }

a.image2.image-link.image2-800-600 { padding-bottom: 133.33333333333331%; padding-bottom: min(133.33333333333331%, 800px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-800-600 img { max-width: 600px; max-height: 800px; } The summer of 2004 was just after the second season of Chappelle’s Comedy Central show aired, the very peak of the series. This was before the Big Deal, the third-season delays, the infamous Africa retreat, and ultimately the end of the show altogether. The end of that particular show-business drama had yet to transpire, but something about the article seemed askew. Chappelle said then that what he’d loved about doing the show was that no one was paying attention, which allowed him and his staff to do whatever they wanted. He worried that now that it was a hit, they’d be under more scrutiny and the fun would dissipate. “The show worked because we acted like nobody was watching,” he told Blender’s Rob Tannenbaum. “And now, everybody’s watching.” As I watched the subsequent events unfold, that sentiment echoed in my head. In his Showtime stand-up special from that year, For What It’s Worth, he comments, “I don’t trip off being a celebrity. I don’t like it. I don’t trust it.”

His appearance on Inside the Actor’s Studio on December 18th, 2005 might be the most the most telling of the time. His intelligence has always been evident even in the crudest of his comedy, but it really shone here. Take his thoughts on the term “crazy” applied to celebrities: “The worst thing to call somebody is ‘crazy’. It’s dismissive. ‘I don’t understand this person, so they’re “crazy.”’ That’s bullshit. These people are not crazy. They’re strong people. Maybe the environment is a little sick.” As he told Blender the year before, “The public really enjoys the downfall of celebrities too much.”

Like his forebears Richard Pryor, Paul Mooney, Bill Cosby, and Eddie Murphy, as well as his closest contemporary, Chris Rock, Chappelle’s take on race is highly nuanced and never forgets the orthogonal concern of class. All the way back to 2000’s Killin’ Them Softly in which he is taken unbeknownst to the ghetto in a limo at 3 a.m. and encounters a weed-selling infant. Acknowledging every issue that scenario entails, Chappelle twists it into one of the funniest bits of the set

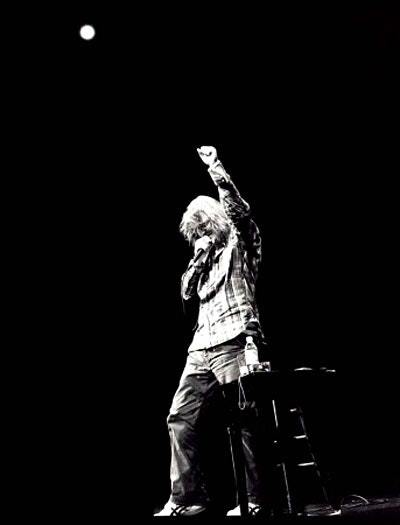

a.image2.image-link.image2-392-616 { padding-bottom: 63.63636363636363%; padding-bottom: min(63.63636363636363%, 392px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-392-616 img { max-width: 616px; max-height: 392px; }

a.image2.image-link.image2-392-616 { padding-bottom: 63.63636363636363%; padding-bottom: min(63.63636363636363%, 392px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-392-616 img { max-width: 616px; max-height: 392px; } After his hiatus, he returned in 2017 with four new Netflix specials. Filmed in each of the previous three years, these show a sturdier, calmer comedian, a storyteller with a lost decade’s worth of stories to tell. There are scant set-up/punchline jokes among the laughs. Chappelle’s delivery here owes a lot to Cosby, whom he somewhat backhandedly defends in The Age of Spin (filmed in March of 2016 at the Hollywood Palladium). This bit displays much of the nuance I mentioned earlier. It’s difficult to be this nuanced, to use subtlety to great effect, when everyone seems to want to split issues right down the middle. The critics have already piled on, drawing lines between themselves and Chappelle’s views on the issues of the day.

There is an aspect of speculative design sometimes called “design fiction,” sometimes called “critical design.” Its practitioners basically set out to challenge the hegemony of the present way of thinking about things—buildings, gadgets, objects, whatever. Instead of reifying the currently held ideas, critical design imagines a different way of doing or seeing things. There’s nothing sacred in comedy, except comedy. Comedy is what’s funny. Comedy is what’s true. You don’t have to agree with it. We don’t have agree with all of the comedy that we laugh at. We don’t have to agree with all of the comedians that we love. We have to let comedy do its own brand of critical design. We have to let comedy explore other possible presents. We have to let comedy do what it does. If we don’t, it is doomed. If we continue without it, we are doomed.

a.image2.image-link.image2-422-750 { padding-bottom: 56.266666666666666%; padding-bottom: min(56.266666666666666%, 422px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-422-750 img { max-width: 750px; max-height: 422px; }

a.image2.image-link.image2-422-750 { padding-bottom: 56.266666666666666%; padding-bottom: min(56.266666666666666%, 422px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-422-750 img { max-width: 750px; max-height: 422px; } Chappelle starts off Equanimity, the first of his two New Year’s Eve specials (filmed in September of 2017 in Washington, DC), claiming to be bowing out again. His mistrust of fame lingers as he cites hitting the comedy jackpot the way he has as a sign it’s time to get out of the casino. Then he makes jokes about how good at it he is—and he is! Making jokes about making jokes is a gamble of a different kind, but Chappelle’s punchlines hit paylines every time. He goes on to address the critics of his last special mentioned above and again deftly illustrates his understanding of the divisive differences between issues of gender and race, as well as race and class. He does a lot of this by splitting the pairings that make odd relationships, from poor white people and rich presidents to the Amish and technology. To be funny is to be good at comedy. To do Chappelle’s level of cultural criticism and be this funny is to be in a rare group of masters. They kill and let live, skewering the worst of the times and making everyone else laugh. That’s comedy’s crowning achievement. And we’re all better for it.

Compared to the others, the last of this spate of specials, The Bird Revelation (filmed in November of 2017 in LA), is a far more intimate affair, in both setting and subject matter. Chappelle illuminates the recent dark days of Hollywood and America, interrogating scandals of all kinds, pushing all the issues past points of comfort, including his own career. He addresses the comedians in the back, calling for them to do the same. “You have a responsibility to speak recklessly,” he says.

Chappelle has continued to speak recklessly, recently taking on the very channel that brought him back. Netflix was streaming his old Comedy Central show without compensating the man. He called them out from the stage, and they pulled the series. Now, it’s back with his blessing. “I never asked Comedy Central for anything,” Chappelle says in a ten-minute clip called “Redemption Song.” He continues,

If you remember I said ‘I’m going to my real boss’ and I came to you because I know where my power lies. I asked you to stop watching the show and thank God almighty for you, you did. You made that show worthless because without your eyes it’s nothing. And when you stopped watching it, they called me. And I got my name back and I got my license back and I got my show back and they paid me millions of dollars. Thank you very much.

Another boon of making power, taking power, and then using it to make more.

At an appearance at Allen University in South Carolina a few years ago, Chappelle said, “It’s okay to be afraid, because you can’t be brave or courageous without fear. The idea of being courageous is that, even though you’re scared, you just do the right thing anyway.” And he told the students at Pace University in 2005, “The world can’t tell you who you are. You just gotta figure out who you are and be that.” He told James Lipton on his show that if he weren’t a comedian, he thought he’d like to be a teacher. I’d say he’s already both.

March 29, 2021

Mitch Hedberg: Different Ingredients

Sixteen years ago today, we lost one of the funniest voices and best visionaries humanity has ever given us. The odd-angled comedy of Mitch Hedberg remains unparalleled.

There’s no way to do him justice, but years ago I attempted to pay tribute to the man. This piece originally appeared on Vulture (née Splitsider) in 2013.

Deep in the desert of Death Valley, there sits a sleepy little resort called Panamint Springs. The cottages and modest restaurant there are a part of no town, connected to no power grid. For several years, the normally quiet cacti and climes were invaded once a year in the peak of heat for four days by a loose band of comedians and their friends. In the summer of 2005, there were seventy-three of us.

On June 5th, the Sunday night of this four-day party, comedian Emery Emery read a newspaper article about Pope John Paul II, but instead of the Pope’s name, he inserted fellow comedian Mitch Hedberg’s, both of whom had died only months before.

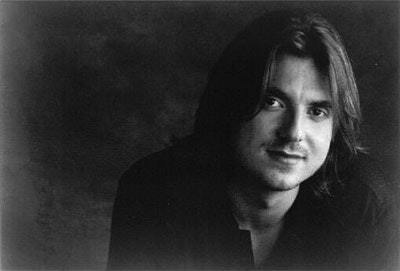

a.image2.image-link.image2-943-718 { padding-bottom: 131.25%; padding-bottom: min(131.25%, 942.375px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-943-718 img { max-width: 718px; max-height: 942.375px; } Mitch Hedberg, 1968-2005

a.image2.image-link.image2-943-718 { padding-bottom: 131.25%; padding-bottom: min(131.25%, 942.375px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-943-718 img { max-width: 718px; max-height: 942.375px; } Mitch Hedberg, 1968-2005

People wept and knelt on cobblestones as the news of his death spread across the square, bowing their heads to a man whose long and down-to-earth comedy was the only one that many young and middle-aged fans around the world remembered. For more than ten minutes, not long after his death was announced, the crowd simply applauded him...

“The world has lost a champion of human freedom and a good and faithful servant of God has been called home,” President Bush said at the White House. “Mitch Hedberg was himself an inspiration to millions of Americans and to so many more throughout the world.”

When Emery finished, he said that it’s sad that people know so much about people like the Pope and not enough about people like Mitch. To which fellow comedian and party-organizer Doug Stanhope replied, “But then we wouldn’t need Mitch.”

Then the power went out.

Then everyone there started chanting, “Mitch! Mitch! Mitch!...” and scattered throughout the darkness of the desert.

a.image2.image-link.image2-484-714 { padding-bottom: 67.75%; padding-bottom: min(67.75%, 483.735px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-484-714 img { max-width: 714px; max-height: 483.735px; }

a.image2.image-link.image2-484-714 { padding-bottom: 67.75%; padding-bottom: min(67.75%, 483.735px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-484-714 img { max-width: 714px; max-height: 483.735px; } Among the roster of beloved, recently deceased comedians—Patrice O’Neal, Mike DeStefano, and Greg Geraldo come immediately to mind—no one haunts us like Mitch Hedberg. He was a superstar in stand-up comedy when he died in late March of 2005. His widow, Lynn Shawcroft, was in attendance at the party in the desert shortly thereafter. Quoting one of his unused notebook pages, she asked me several times that week, “Do you believe in Gosh?”—a joke that later became the name of Mitch's one posthumous CD. Mitch’s laidback, sometimes self-conscious delivery and brain-backwards observations, as well as his propensity for constantly breaking character and the fourth wall of theatre, connected him to his audiences more directly than many other comedians of his time. He often reacted to his own jokes as if he were in the audience and commented on the audience’s reactions, stating that a joke was funnier than they acted, or that one joke was the same as another with "different ingredients.” Many of his shows were similar to those of a touring arena-rock band, where the audience sings along. His fans would wait for jokes that they were familiar with and yell out the punch lines as Mitch said them. Though his style was reminiscent of comedian Steven Wright, his humble and humane presence made him beloved by everyone who saw him.

Mitch’s former tour manager and friend Greg Chaille described a dream he had after Mitch’s death:

I dipped into a very deep sleep early this morning. I had a dream that I was riding in the back of a pickup with Mitch. I don’t remember who was driving but we were moving pretty good on a clear and sunny day. He was sitting on the driver’s side facing forward, and I was on the back wheel hump on the passenger side.

I just kept looking over at him thinking, “I knew he was still around.” He would just look over at me and smile a knowing smile, like “I know what I’m doing, it’s all okay. Everything is alright.”

I was so happy that Mitch was sitting across from me I started to cry. I reached over to hug him and then I woke up.

I was at a bar in Seattle called Lynda’s with Chaille and several other comedians on the two-year anniversary of Mitch’s passing, and we all went around the table telling our favorite Mitch jokes.

"Last week I helped a friend stay put,” started one comedian. “It's a lot easier than helping someone move. I just went over to his house and made sure that he did not start to load shit into a truck."

“I had my hair highlighted because I thought some strands were more important than others,” offered someone else.

"An escalator can never be broken, it can only become stairs,” added another. “Escalator temporarily stairs! Sorry for the convenience!" everyone finished in unison.

“I think Pringles original intention was to make tennis balls,” I chimed in, “but on the day the rubber was supposed to show up a truckload of potatoes came. Pringles is a laid back company, so they just said ‘fuck it, cut ‘em up!’”

During the blackout in the desert, Chaille built a bonfire in the campground across the road from the Panamint Springs resort. We all soon reconvened there, clumsily finding our way through the dark desert where Mitch’s spirit still lingered. Shortly after his death, comedians from all over the country gathered in Los Angeles to honor Mitch’s memory. “If I didn't get a chance to say hello,” friend and fellow comedian Doug Stanhope wrote on his website after the show, “it's because it was hard to talk.”

“If you would like to hear a loud tone, press 2. If not, leave a message.”

– Mitch's outgoing voicemail message.

When his CD Do You Believe in Gosh? was released in 2008, the “One Nation Under Gosh” shows celebrated Mitch in comedy clubs in Seattle, Cincinnati, Minneapolis, New York City, Hollywood, and Austin, proving that his spirit lives on on comedy stages nationwide.

a.image2.image-link.image2-477-642 { padding-bottom: 74.25%; padding-bottom: min(74.25%, 476.685px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-477-642 img { max-width: 642px; max-height: 476.685px; } Mitch Hedberg and Doug Stanhope, March 15, 2005.

a.image2.image-link.image2-477-642 { padding-bottom: 74.25%; padding-bottom: min(74.25%, 476.685px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-477-642 img { max-width: 642px; max-height: 476.685px; } Mitch Hedberg and Doug Stanhope, March 15, 2005.“Nobody has asked me how Mitch lived,” Stanhope wrote of Mitch not long after his death. “And Mitch lived like a motherfucker. More than most any of us will live. That isn't sad or tragic. Mitch was the kind of comic that was funny even when nobody was looking. It wasn't just for the stage, the ego, or the random congratulations. He was funny when he was alone.” Doug told me that his phone had never rang like it did when Mitch died, every caller eager to find out about Mitch's demise.

“I don't know how Mitch died,” Stanhope concludes. “I know how Mitch lived, and he lived brilliantly and by his own rules. The number of years next to his name is trivia. The contents of those years is inspiration.” Here’s hoping his spirit continues to inspire, haunting our hearts and heads with laughter.

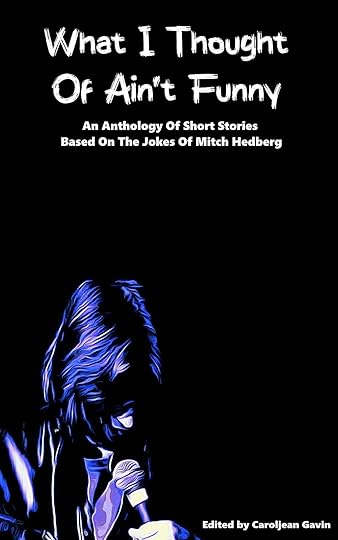

For more Hedberg-inspired reading, check out the Malarkey Books anthology, What I Thought of Ain’t Funny, edited by Caroljean Gavin: 17 short stories based on the jokes of Mitch Hedberg.

a.image2.image-link.image2-1600-1000 { padding-bottom: 160%; padding-bottom: min(160%, 1600px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-1600-1000 img { max-width: 1000px; max-height: 1600px; }

a.image2.image-link.image2-1600-1000 { padding-bottom: 160%; padding-bottom: min(160%, 1600px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-1600-1000 img { max-width: 1000px; max-height: 1600px; } Mitch Hedberg passed on March 29, 2005. Here’s to his humor and lasting memory.

March 25, 2021

Crash Worship: Examining the Wreckage

First up, a new online literature journal called Sledgehammer Lit launched today, and I have a poem up there! It’s called “San Diego,” and it will also be in my collection of poems coming out in July in Close to the Bone’s First Cut series of chapbooks. Check it out.

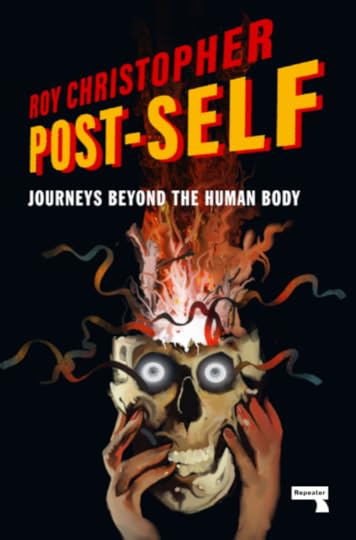

Next, the excerpt below is from my book-in-progress, Post-Self: Journeys Beyond the Human Body (Repeater Books, 2022). This bit went up on the Malarkey Books website last week, but I thought I’d share it with you here. It’s from Chapter 2, “Machine: The End of an Error.”

Planned as a short volume, Post-Self is an exploration of the human body and the ways it might be transcended. Possible escapes include machines, drugs, dreams, and death. Using extreme music and film as points of departure, it digs deep into the darkest thoughts of the most dissatisfied minds, minds that want to leave their bodies behind.

Enjoy!

a.image2.image-link.image2-775-511 { padding-bottom: 151.66340508806263%; padding-bottom: min(151.66340508806263%, 775px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-775-511 img { max-width: 511px; max-height: 775px; } Post-Self: Journeys Beyond the Human Body (Repeater Books, 2022). Cover by Johnny Bull.

a.image2.image-link.image2-775-511 { padding-bottom: 151.66340508806263%; padding-bottom: min(151.66340508806263%, 775px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-775-511 img { max-width: 511px; max-height: 775px; } Post-Self: Journeys Beyond the Human Body (Repeater Books, 2022). Cover by Johnny Bull.

“Nothing of us will survive. We will be killed not by the gun but by the glad-hand. We will be destroyed not by the rocket but by the automobile…”

— Ettil In Ray Bradbury’s “The Concrete Mixer”

“Hear the crushing steel

Feel the steering wheel”

— The Normal, “Warm Leatherette”

I ordered the seven-inch of Jawbox’s 1993 single, “Motorist,” as soon as I knew it was available. The lyrics, even for a Jawbox song, were striking. “Accidental, maybe,” ponders J. Robbins, “restraints too frayed to withhold me.”[i] Paul Virilio once wrote that whenever we invent a new technology, we also invent a new kind of accident.[ii] We might never again invent a technology that is so prone to accidents as we have with the automobile. Hearing Jawbox play “Motorist” live again reminded me of the wreckage of artifacts piled up in my head around the song.

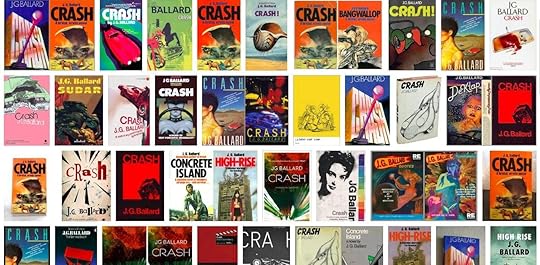

Over Zach Borocas’ lurching beat and Kim Coletta’s chugging bass, as well as his and Bill Barbot’s dual, dueling guitar feedback, Robbins yells, “when you examined the wreck, what did you see? Glass everywhere and wheels still spinning free.” I remember immediately thinking of the 1973 J.G. Ballard novel, Crash. In the simplest of terms, Crash is about a group of people who fetishize car crashes. Most of them have been in actual accidents, but they also stage their own. They are sexually aroused by the impact as well as the aftermath, the energies and the injuries.

Though I hadn’t read it, I thought Robbins had. I found out recently that the song is actually about a car accident that happened in Chicago while Jawbox was on tour some 30 years ago. While back in town during the last night of the band’s 2019 summer reunion tour, Robbins told the story on stage at the Metro. In light of this new information, I’ve tried to rewire my interpretation of the song. In my head Jawbox’s “Motorist” remains connected to Ballard’s Crash.

Compare Robbins’ singing, “cracked gauges carry messages for me. Calls and responses you can't see” to Ballard writing, “In front of me the instrument panel had been buckled inwards, cracking the clock and speedometer dials. Sitting here in this deformed cabin, filled with dust and damp carpeting, I tried to visualize myself at the moment of collision, the failure of the technical relationship between my own body, the assumptions of the skin, and the engineering structure which supported it,” or “The wounds on my knees and chest were beacons tuned to a series of beckoning transmitters, carrying the signals, unknown to myself, which would unlock this immense stasis and free these drivers for the real destinations set for their vehicles, the paradises of the electric highway.”[i] This motorized mysticism, the idea that technology enables and endures unintended uses and conjures and communicates unintended messages runs parallel to the cult of the car. Scriptures superimposed on the roads. Messages, transmitters, signals, all performing a discourse of dread, a dialogue of deadly trauma.

Automobile-accident numbers are routinely trotted out in comparison to whatever disaster is threatening human lives at the time. Gun violence, viral plagues, and various cancers are all measured at least annually against the deaths we inflict driving these vehicles. As Zadie Smith writes in The Guardian, quoting Ballard himself, “Like the characters in Crash we are willing participants in what Ballard called ‘a pandemic cataclysm that kills hundreds of thousands of people each year and injures millions.’ The death-drive, Thanatos, is not what drivers secretly feel, it’s what driving explicitly is.”[iv] When we hear the statistics, we might worry for a second, noting those we know who’ve passed away on the road or been maimed by molded metal, but we soon continue our car-enabled commutes undeterred.

a.image2.image-link.image2-670-1000 { padding-bottom: 67%; padding-bottom: min(67%, 670px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-670-1000 img { max-width: 1000px; max-height: 670px; } Collage by Roy Christopher.

a.image2.image-link.image2-670-1000 { padding-bottom: 67%; padding-bottom: min(67%, 670px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-670-1000 img { max-width: 1000px; max-height: 670px; } Collage by Roy Christopher.Death isn’t the only Freudian trope that these stories stir up. Sex is wound into the car accident as well, both as pornography and as intimacy. “When Ballard called Crash the first ‘pornographic novel about technology’,” Smith continues, “he referred not only to a certain kind of content but to pornography as an organizing principle…” We might not enjoy pornography or admit that we do, but we all understand it as a concept. It’s meaning is not a mystery. In Crash, it acts as a skewed skeuomorph. As Ballard writes, it is “as if the presence of the car mediated an element which alone made sense of the sexual act.”[v] And aren’t cars always already sexualized? The metaphor is close at hand: pistons and spark plugs, revving and thrusting, hands gripping curves and contours galore.

The jutting juxtaposition of body parts and auto parts and the blending of bodily fluids and engine oils might be more disturbing when thought of as intimacy than as pornography.[vi] “The real shock of Crash is not that people have sex in or near cars,” Smith writes, “but that technology has entered into even our most intimate human relations.” Consider the difference between the phrase “fucking the car” and “making love to the car.” It’s not the violence of the sex act but the intimate presence of technology there that chafes our sensibilities. It’s not the sexual appropriation of a mechanical contrivance but the emotional possibility of love that bothers us. “Traditional warnings against the evils of mediation reach an ironic zenith in this portrait of ‘the most terrifying casualty of the century: the death of affect’,”[vii] Dominic Pettman notes grimly. With sex and technology crammed together in this context, we can’t decide if it’s better or worse to care.

No matter how you feel about them, car-crashes and sexual encounters force one thing on everyone: exposure. From fender benders to total immobility, no one wants to get caught in the act, caught with their pants down, in flagrante delicto. Ballard himself described Crash as a forced look in the mirror. “You can see your reflection in the luminescent dash,” Daniel Miller sings on The Normal’s Crash-inspired track, “Warm Leatherette.”[viii] “Seduced reflection in the chrome,” Siouxsie Sioux adds on the Creatures’ Ballardian “Miss the Girl.”[ix] “New way to see what’s laid plain in front of me,” Robbins wails on “Motorist.” “Nothing better than a look at what I shouldn’t see.”

No one wants to get caught with their body thrown clear at odd angles, the contents of their car strewn, the whole of their very lives lying limp on the pavement. Every illicit tryst implies its own exit strategy. On “Motorist,” Robbins concludes, “Turn your back, just drive on past, because nothing is better than getting out fast.”

Look hard and then look away. The fastest car is the getaway.

Uncanny Cartographies

It’s been over a decade. A decade without Ballard. It should be more noticeable. Like filling an empty pool with emptiness, to paraphrase China Miéville.[x] A void of perspective, crumbling and gaping at our heels. Everyone should feel it. It goes without saying, but I’ll say it anyway: This is the way, step inside.

His work has been translated to the screen by directors with styles as varied as Steven Spielberg (Empire of the Sun) and David Cronenberg (Crash). He was interviewed by countless talented writers, including Jon Savage, V. Vale, Will Self, Richard Kadrey, John Gray, Simon Sellars, and Mark Dery. His influence is found in sound from Joy Division, The Jesus and Mary Chain, Sisters of Mercy, K.K. Null, and Gary Numan to Madonna, Radiohead, Trevor Horn, Cadence Weapon, and Danny Brown, as well as the aforementioned Creatures and The Normal. His writing and thinking are broad enough to elude categories and focused enough to remain absolutely singular. His work gerrymanders genre distinctions, defining and defying its own boundaries as it goes. I think of him in the same way I think of Octavia E. Butler, Thomas Pynchon, Don DeLillo, and Samuel R. Delany: as giants beyond genre.

a.image2.image-link.image2-663-1352 { padding-bottom: 49.03846153846153%; padding-bottom: min(49.03846153846153%, 663px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-663-1352 img { max-width: 1352px; max-height: 663px; } Various Ballard Crash covers.

a.image2.image-link.image2-663-1352 { padding-bottom: 49.03846153846153%; padding-bottom: min(49.03846153846153%, 663px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-663-1352 img { max-width: 1352px; max-height: 663px; } Various Ballard Crash covers.“I suppose we are moving into a realm where inner space is no longer just inside our skulls but is in the terrain we see around us in everyday life,” Ballard said in 1974:

We are moving into a world where the elements of fiction are that world—and by fiction I mean anything invented to serve imaginative ends, whether it is invented by an advertising agency, a politician, an airline, or what have you. These elements have now crowded out the old-fashioned elements of reality.[xi]

Since then a lot of mental offloading and cognitive outsourcing has occurred, our inner thoughts texture-mapped onto every surface. In that meantime some of Ballard’s children have emerged in mongrel forms and curtained corners of mass media. Think Wild Palms or Jackass or the ever-blurring lines between reality and show, news and entertainment. “It’s not news,” he wrote, “it’s entertainment news. A documentary on brain surgery is about entertainment brain surgery.” Inversely, Ballard collaged and kludged together the sets of his own Atrocity Exhibition out of internal organs: “[T]he nervous systems of the characters have been externalized, as part of the reversal of the interior and exterior worlds. Highways, office blocks, faces, and street signs are perceived as if they were elements in a malfunctioning central nervous system.”[xii] Michel de Certeau once wrote, “books are only metaphors of the body.”[xiii] Ballard often seemed to be crash-testing that idea.

The transmedia spread of everted inner space is nowhere more evident than on the internet. William Gibson said as much in his novel Spook Country.[xiv] Michel de Certeau wrote elsewhere, “what the map cuts up, the story cuts across.”[xv] These are maps of different terrain and stories of a different cut. As Simon Sellars points out, unlike the cyberpunks who followed him, Ballard’s maps of these near futures weren’t as celebratory as they were cautionary: Dangerous Curves Ahead. Slow Down.[xvi]

Post-Self will be out on Repeater Books in March of 2022.[i] J. Robbins, “Motorist.” On “Motorist” b/w “Jackpot Plus” [7” single]. Recorded by Jawbox. Washington, DC: Dischord Records, 1993.

[ii] Paul Virilo, “The Museum of Accidents,” trans. Chris Turner, International Journal of Baudrillard Studies 3, no. 2, 2006.

[iii] J.G. Ballard, Crash: A Novel. London: Jonathan Cape, 1973, p. 68; 44.

[iv] Zadie Smith, “Sex and Wheels: Zadie Smith on J.G. Ballard’s Crash.” The Guardian, July 4, 2014.

[v] Ballard, 1973, p. xii.

[vi] For examples regarding David Cronenberg’s 1996 film adaptation, see Martin Barker, Jane Arthurs & Ramaswami Harindranath, The Crash Controversy: Censorship Campaigns and Film Reception. London: Wallflower Press, 2001.

[vii] Dominic Pettman, After the Orgy: Toward a Politics of Exhaustion, New York: SUNY Press, 2002, p. 80. Pettman is quoting from Andrea Juno, 1984.

[viii] Daniel Miller, “T.V.O.D.” b/w “Warm Leatherette” [7” single]. Recorded by The Normal. London: Mute Records, 1978. Daniel Miller and a friend had written a screenplay based on Ballards’ Crash. When they couldn’t get it made, Miller condensed it into the song “Warm Leatherette.” Of course, this single, as auspicious as it turned out to be, was made much more popular by Grace Jones when she covered it in 1980.

[ix] Siouxsie Sioux & Budgie, “Miss the Girl” b/w “Hot Springs in the Snow” [7” single]. Recorded by The Creatures. London: Wonderland, 1983.

[x] China Miéville. (2008). Introduction. In J. G. Ballard, Miracles of Life: Shanghai to Shepperton, an Autobiography. New York: Liveright, pp. ix-xiv.

[xi] Quoted in J. G. Ballard. (2012). Extreme Metaphors: Collected Interviews. Simon Sellars & Dan O’Hara, Eds. London: Fourth Estate, p. 62; see also Ballard (1985), Crash: A Novel. New York: Vintage, p. 4-5.

[xii] J. G. Ballard. (1970). The Atrocity Exhibition. London: Jonathan Cape, p. 76.

[xiii] Michel de Certeau. (1984). The Practice of Everyday Life. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, p. 140.

[xiv] William Gibson. (2007). Spook Country. New York: Putnam, pp. 63-64.

[xv] de Certeau, 1984, p. 129.

[xvi] Simon Sellars. (2018). Applied Ballardianism: Memoir from a Parallel Universe. Falmouth, UK: Urbanomic.

March 16, 2021

Dead Precedents: How Hip-Hop Defines the Future

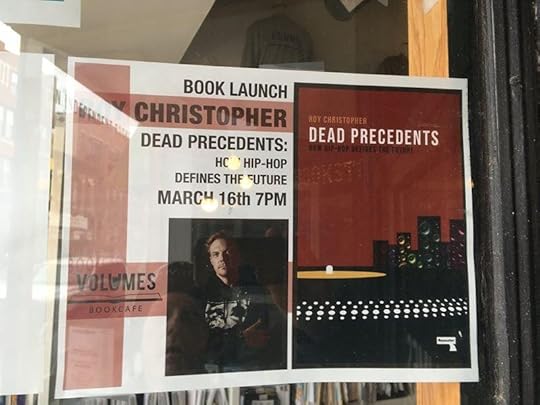

This week marks the two-year anniversary of the publication of my book Dead Precedents: How Hip-Hop Defines the Future from Repeater Books! In celebration, here are some pictures from the book’s release, the Preface from the text, and some information on a related forthcoming project. Enjoy!

a.image2.image-link.image2-600-800 { padding-bottom: 75%; padding-bottom: min(75%, 600px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-600-800 img { max-width: 800px; max-height: 600px; }

a.image2.image-link.image2-600-800 { padding-bottom: 75%; padding-bottom: min(75%, 600px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-600-800 img { max-width: 800px; max-height: 600px; } We launched Dead Precedents properly at Volumes Bookcafé in Chicago with readings by me, Krista Franklin, and Ytasha Womack.

a.image2.image-link.image2-1092-1456 { padding-bottom: 75%; padding-bottom: min(75%, 1092px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-1092-1456 img { max-width: 1456px; max-height: 1092px; } Krista Franklin, me, and Ytasha Womack. Photo by Lily Brewer.

a.image2.image-link.image2-1092-1456 { padding-bottom: 75%; padding-bottom: min(75%, 1092px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-1092-1456 img { max-width: 1456px; max-height: 1092px; } Krista Franklin, me, and Ytasha Womack. Photo by Lily Brewer.Ytasha and I went on to do a talk at the Seminary Co-op in Hyde Park, and I spoke at SXSW again, this time specifically about the ideas in Dead Precedents.

a.image2.image-link.image2-663-1200 { padding-bottom: 55.25%; padding-bottom: min(55.25%, 663px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-663-1200 img { max-width: 1200px; max-height: 663px; } Talkin’ beaks and rhymes at SXSW. Photo by Matt Stephenson.

a.image2.image-link.image2-663-1200 { padding-bottom: 55.25%; padding-bottom: min(55.25%, 663px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-663-1200 img { max-width: 1200px; max-height: 663px; } Talkin’ beaks and rhymes at SXSW. Photo by Matt Stephenson. a.image2.image-link.image2-600-800 { padding-bottom: 75%; padding-bottom: min(75%, 600px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-600-800 img { max-width: 800px; max-height: 600px; } As Pecos B. Jett called it, “Biz Marquee!“

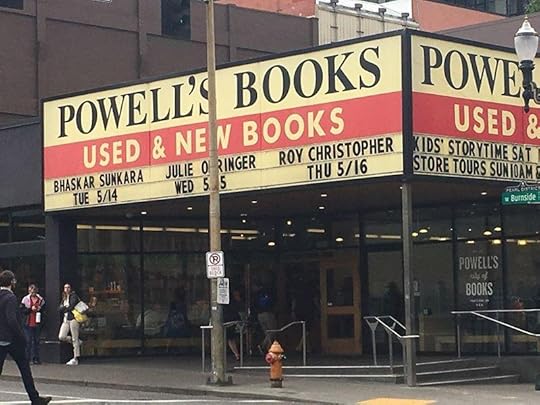

a.image2.image-link.image2-600-800 { padding-bottom: 75%; padding-bottom: min(75%, 600px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-600-800 img { max-width: 800px; max-height: 600px; } As Pecos B. Jett called it, “Biz Marquee!“A couple of months later, I ventured to my adopted home in the Pacific Northwest. I got to speak at Powell’s City of Books in Portland with Pecos B. Jett. I was even on TV!

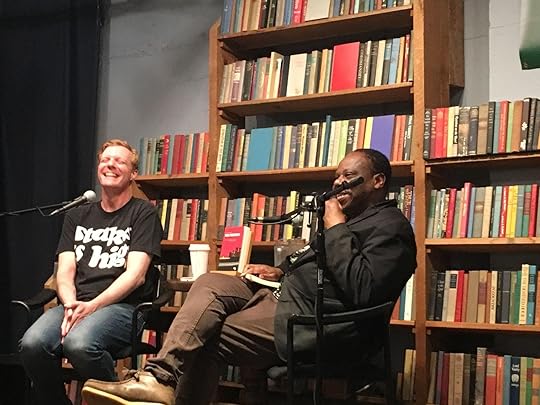

Next up was a fun chat at the Elliott Bay Book Company in Seattle with Charles Mudede.

a.image2.image-link.image2-1092-1456 { padding-bottom: 75%; padding-bottom: min(75%, 1092px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-1092-1456 img { max-width: 1456px; max-height: 1092px; } Me and Charles Mudede yuckin’ it up at Elliott Bay. Photo by Lily Brewer.

a.image2.image-link.image2-1092-1456 { padding-bottom: 75%; padding-bottom: min(75%, 1092px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-1092-1456 img { max-width: 1456px; max-height: 1092px; } Me and Charles Mudede yuckin’ it up at Elliott Bay. Photo by Lily Brewer.I was also on my favorite Hip-hop podcast, Call Out Culture with my mans Alaska, Zilla Rocca, and Curly Castro.

a.image2.image-link.image2-1388-1425 { padding-bottom: 97.40350877192982%; padding-bottom: min(97.40350877192982%, 1388px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-1388-1425 img { max-width: 1425px; max-height: 1388px; }

a.image2.image-link.image2-1388-1425 { padding-bottom: 97.40350877192982%; padding-bottom: min(97.40350877192982%, 1388px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-1388-1425 img { max-width: 1425px; max-height: 1388px; } I know Amazon is wack, but Dead Precedents was also a #1 New Release in both their Rap Music and Music History & Criticism categories.

a.image2.image-link.image2-516-640 { padding-bottom: 80.625%; padding-bottom: min(80.625%, 516px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-516-640 img { max-width: 640px; max-height: 516px; } Take that, Beastie Boys Book!

a.image2.image-link.image2-516-640 { padding-bottom: 80.625%; padding-bottom: min(80.625%, 516px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-516-640 img { max-width: 640px; max-height: 516px; } Take that, Beastie Boys Book!Many thanks to all the people who bought the book, said nice things about it, came out to hear me talk about it, gave me rides, put me up at your home, or spread the word. There are too many people I owe to list here, but I appreciate all of you who have supported me and this book in any way.

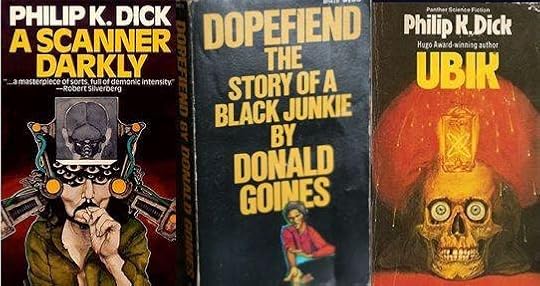

If you’re interested in more about hip-hop, cyberpunk, and Afrofuturism, a bunch of my friends and colleagues and I have put together a new book called Boogie Down Predictions: Hip-Hop, Time, and Afrofuturism.

“How does hip-hop fold, spindle, or mutilate time?” Harry Allen, Hip-Hop Activist and Media Assassin asks. “In what ways does it treat technology as, merely, a foil? Are its notions of the future tensed…or are they tenseless? For Boogie Down Predictions, Roy Christopher's trenchant anthology, he's assembled a cluster of curious interlocutors. Here, in their hands, the culture has been intently examined, as though studying for microfractures in a fusion reactor. The result may not only be one of the most unique collections on hip-hop yet produced, but, even more, and of maximum value, a novel set of questions.”

a.image2.image-link.image2-783-1456 { padding-bottom: 53.777472527472526%; padding-bottom: min(53.777472527472526%, 783px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-783-1456 img { max-width: 1456px; max-height: 783px; } Art by Edwin Pouncey a.k.a. Savage Pencil.