Roy Christopher's Blog, page 19

February 17, 2021

Coming to Terms with Dave Chappelle

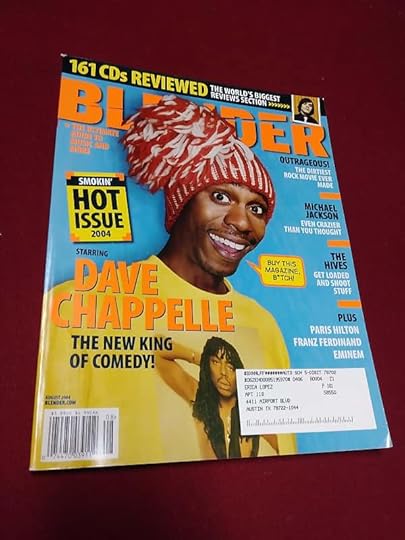

I distinctly remember the only issue of Blender Magazine that I ever read had Dave Chappelle on the cover (August 2004). The mid-00s were the magazine format’s last peak, and there were so many of them, newsstands stretching down grocery-store aisles, colorful covers like cereal boxes. I don’t remember what prompted my purchase of this particular issue, but I read the Chappelle piece with intense interest. I’d seen some of Chappelle’s stand-up and seen him in movies here and there. I’d never seen Chappelle’s Show proper, though I’d watched clips from it online. I had friends who were huge fans though, the kind who couldn’t describe a sketch without devolving into uncontrollable laughter.

a.image2.image-link.image2-800-600 { padding-bottom: 133.33333333333331%; padding-bottom: min(133.33333333333331%, 800px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-800-600 img { max-width: 600px; max-height: 800px; }

a.image2.image-link.image2-800-600 { padding-bottom: 133.33333333333331%; padding-bottom: min(133.33333333333331%, 800px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-800-600 img { max-width: 600px; max-height: 800px; } The summer of 2004 was just after the second season of Chappelle’s Comedy Central show aired, the very peak of the series. This was before the Big Deal, the third-season delays, the infamous Africa retreat, and ultimately the end of the show altogether. The end of that particular show-business drama had yet to transpire, but something about the article seemed askew. Chappelle said then that what he’d loved about doing the show was that no one was paying attention, which allowed him and his staff to do whatever they wanted. He worried that now that it was a hit, they’d be under more scrutiny and the fun would dissipate. “The show worked because we acted like nobody was watching,” he told Blender’s Rob Tannenbaum. “And now, everybody’s watching.” As I watched the subsequent events unfold, that sentiment echoed in my head. In his Showtime stand-up special from that year, For What It’s Worth, he comments, “I don’t trip off being a celebrity. I don’t like it. I don’t trust it.”

His appearance on Inside the Actor’s Studio on December 18th, 2005 might be the most the most telling of the time. His intelligence has always been evident even in the crudest of his comedy, but it really shone here. Take his thoughts on the term “crazy” applied to celebrities: “The worst thing to call somebody is ‘crazy’. It’s dismissive. ‘I don’t understand this person, so they’re “crazy.”’ That’s bullshit. These people are not crazy. They’re strong people. Maybe the environment is a little sick.” As he told Blender the year before, “The public really enjoys the downfall of celebrities too much.”

Like his forebears Richard Pryor, Paul Mooney, Bill Cosby, and Eddie Murphy, as well as his closest contemporary, Chris Rock, Chappelle’s take on race is highly nuanced and never forgets the orthogonal concern of class. All the way back to 2000’s Killin’ Them Softly in which he is taken unbeknownst to the ghetto in a limo at 3 a.m. and encounters a weed-selling infant. Acknowledging every issue that scenario entails, Chappelle twists it into one of the funniest bits of the set

a.image2.image-link.image2-392-616 { padding-bottom: 63.63636363636363%; padding-bottom: min(63.63636363636363%, 392px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-392-616 img { max-width: 616px; max-height: 392px; }

a.image2.image-link.image2-392-616 { padding-bottom: 63.63636363636363%; padding-bottom: min(63.63636363636363%, 392px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-392-616 img { max-width: 616px; max-height: 392px; } After his hiatus, he returned in 2017 with four new Netflix specials. Filmed in each of the previous three years, these show a sturdier, calmer comedian, a storyteller with a lost decade’s worth of stories to tell. There are scant set-up/punchline jokes among the laughs. Chappelle’s delivery here owes a lot to Cosby, whom he somewhat backhandedly defends in The Age of Spin (filmed in March of 2016 at the Hollywood Palladium). This bit displays much of the nuance I mentioned earlier. It’s difficult to be this nuanced, to use subtlety to great effect, when everyone seems to want to split issues right down the middle. The critics have already piled on, drawing lines between themselves and Chappelle’s views on the issues of the day.

There is an aspect of speculative design sometimes called “design fiction,” sometimes called “critical design.” Its practitioners basically set out to challenge the hegemony of the present way of thinking about things—buildings, gadgets, objects, whatever. Instead of reifying the currently held ideas, critical design imagines a different way of doing or seeing things. There’s nothing sacred in comedy, except comedy. Comedy is what’s funny. Comedy is what’s true. You don’t have to agree with it. We don’t have agree with all of the comedy that we laugh at. We don’t have to agree with all of the comedians that we love. We have to let comedy do its own brand of critical design. We have to let comedy explore other possible presents. We have to let comedy do what it does. If we don’t, it is doomed. If we continue without it, we are doomed.

a.image2.image-link.image2-422-750 { padding-bottom: 56.266666666666666%; padding-bottom: min(56.266666666666666%, 422px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-422-750 img { max-width: 750px; max-height: 422px; }

a.image2.image-link.image2-422-750 { padding-bottom: 56.266666666666666%; padding-bottom: min(56.266666666666666%, 422px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-422-750 img { max-width: 750px; max-height: 422px; } Chappelle starts off Equanimity, the first of his two New Year’s Eve specials (filmed in September of 2017 in Washington, DC), claiming to be bowing out again. His mistrust of fame lingers as he cites hitting the comedy jackpot the way he has as a sign it’s time to get out of the casino. Then he makes jokes about how good at it he is—and he is! Making jokes about making jokes is a gamble of a different kind, but Chappelle’s punchlines hit paylines every time. He goes on to address the critics of his last special mentioned above and again deftly illustrates his understanding of the divisive differences between issues of gender and race, as well as race and class. He does a lot of this by splitting the pairings that make odd relationships, from poor white people and rich presidents to the Amish and technology. To be funny is to be good at comedy. To do Chappelle’s level of cultural criticism and be this funny is to be in a rare group of masters. They kill and let live, skewering the worst of the times and making everyone else laugh. That’s comedy’s crowning achievement. And we’re all better for it.

Compared to the others, the last of this spate of specials, The Bird Revelation (filmed in November of 2017 in LA), is a far more intimate affair, in both setting and subject matter. Chappelle illuminates the recent dark days of Hollywood and America, interrogating scandals of all kinds, pushing all the issues past points of comfort, including his own career. He addresses the comedians in the back, calling for them to do the same. “You have a responsibility to speak recklessly,” he says.

Chappelle has continued to speak recklessly, recently taking on the very channel that brought him back. Netflix was streaming his old Comedy Central show without compensating the man. He called them out from the stage, and they pulled the series. Now, it’s back with his blessing. “I never asked Comedy Central for anything,” Chappelle says in a ten-minute clip called “Redemption Song.” He continues,

If you remember I said ‘I’m going to my real boss’ and I came to you because I know where my power lies. I asked you to stop watching the show and thank God almighty for you, you did. You made that show worthless because without your eyes it’s nothing. And when you stopped watching it, they called me. And I got my name back and I got my license back and I got my show back and they paid me millions of dollars. Thank you very much.

Another boon of making power, taking power, and then using it to make more.

At an appearance at Allen University in South Carolina a few years ago, Chappelle said, “It’s okay to be afraid, because you can’t be brave or courageous without fear. The idea of being courageous is that, even though you’re scared, you just do the right thing anyway.” And he told the students at Pace University in 2005, “The world can’t tell you who you are. You just gotta figure out who you are and be that.” He told James Lipton on his show that if he weren’t a comedian, he thought he’d like to be a teacher. I’d say he’s already both.

February 12, 2021

Halloween and Apocalypse: Richard Kelly's Alternate Timelines

At the height of my fandom of Richard Kelly’s first movie, Donnie Darko (2001), I attended a midnight screening of the director’s cut at The Egyptian Theatre in Seattle. During the trivia contest that preceded the movie, I was asked to sit out due to my long string of correct answers. The movie struck something in me at a time when I needed to be struck. As Kelly himself put it, “I think you are challenged by things that are slightly beyond your grasp.” It is those things obscured that make a movie like this so engaging, endearing, and enduring.

a.image2.image-link.image2-819-1456 { padding-bottom: 56.25%; padding-bottom: min(56.25%, 819px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-819-1456 img { max-width: 1456px; max-height: 819px; } Donnie Darko (Jake Gyllenhaal), Gretchen Ross (Jena Malone), and Frank (James Duvall) watching The Evil Dead.

a.image2.image-link.image2-819-1456 { padding-bottom: 56.25%; padding-bottom: min(56.25%, 819px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-819-1456 img { max-width: 1456px; max-height: 819px; } Donnie Darko (Jake Gyllenhaal), Gretchen Ross (Jena Malone), and Frank (James Duvall) watching The Evil Dead.Like its lauded indie debut cousin Reservoir Dogs (1992), Donnie Darko starts with a conversation scene set over a meal, a scene in which we meet most of the main characters of the film. It’s an elegant and efficient way to establish not only the characters but also their social dynamic. In Reservoir Dogs, the scene revolves around Mr. Blue’s Madonna monologue, which one assumes at this point was written by Roger Avery and not by Quinten Tarantino, who delivers it in the movie, Joe’s address book, and Mr. Pink’s refusal to tip. In Donnie Darko, it revolves around Donnie’s sister Elizabeth’s politics, Donnie’s apparent refusal to take his meds, and their use of foul language at the dinner table. In each, the trio of topics reveals just enough about the characters’ attitudes and how they play together.

Aside from Donnie and Elizabeth (played by the real-life siblings Jake and Maggie Gyllenhaal), the Darko family consists of father Eddie (the inimitable Holmes Osborne), mother Rose (the fabulous Mary McDonnell), and kid sister Samantha (Daveigh Chase, the only original Darko defector to the abortive sequel S. Darko). Other stellar performances are turned in by Gretchen Ross (Jena Malone), Kitty “Sometimes I doubt your commitment to Sparkle Motion” Farmer (Beth Grant), Jim Cunnigham (Patrick Swayze), Ronald Fisher (Stuart Stone), Kenneth Monnitoff (Noah Wyle), Karen Pomeroy (Drew Barrymore), Ricky Danforth (Seth Rogan, in his big-screen debut), Seth Devlin (Alex Greenwald), and, of course, Frank (James Duvall).

a.image2.image-link.image2-1219-800 { padding-bottom: 152.375%; padding-bottom: min(152.375%, 1219px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-1219-800 img { max-width: 800px; max-height: 1219px; } A Pookah by Eoghan Kerrigan.

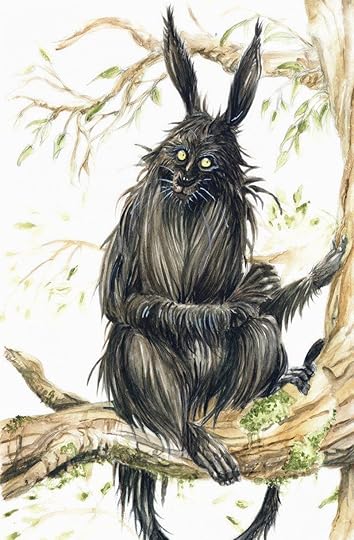

a.image2.image-link.image2-1219-800 { padding-bottom: 152.375%; padding-bottom: min(152.375%, 1219px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-1219-800 img { max-width: 800px; max-height: 1219px; } A Pookah by Eoghan Kerrigan.Though he’s never formally acknowledged it, Kelly’s Frank the Rabbit character can be interpreted as a play on the pookah legend, which Robert Anton Wilson explained as follows:

The pookah takes many forms, but is most famous when he appears as a giant, six-foot white rabbit—which is the form most Americans know from the play and film, Harvey. Whatever form the pookah takes, he retains the special ability of his species, which is like that of Thoth in Egyptian legend, Coyote in Native American myth, or Hanuman the Divine Monkey in Hindu lore — he can move us from one universe, or Belief System, into another, and he likes to play games with our ideas about “reality.”

The iconography of Donnie Darko starts with Frank. Like Jason Voorhees’ hockey mask or Freddy Krueger’s razor-fingered glove, Frank’s rabbit suit is as distinctive a symbol for a movie as there has ever been. Frank is from the future and he mentors Donnie through the film with cryptic guidance and disjointed advice. The setting and surroundings of Halloween, as well as the late-night bike-ride nod to E.T. (1982), are also endemic to this movie. For example, take the music video for “What’s a Girl to Do?” by Bat for Lashes, directed by Dougal Wilson. Aside from the rabbit mask, nothing here directly refers to the movie, but the cumulative homage is obvious.

The references to other movies in Donnie Darko are as subtle as the soundtrack is. Like Tarantino, Kelly uses music to add another element to the film. It’s a different approach to soundtracking than many movies use. For instance, I always wonder what the music in True Romance (1993) would’ve entailed had Tarantino ended up directing it as well. Tony Scott did a fine job, but the music wasn’t handled the way Tarantino usually does it. The music in Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction (1994) adds so much to the overall feel of the films. Kelly pulled off the same added element with Donnie Darko‘s soundtrack, saying, “there were opportunities in this story to put a musical code on the character’s experience within this era. Picking those songs was, on our part, not to do with making it campy and mocking of the 1980s… We wanted the music to be sincere.” To wit, the feeling and lyrics of Echo and the Bunnymen’s “Killing Moon,” INXS’s “Never Tear Us Apart,” and Joy Division’s “Love Will Tear Us Apart,” as well as Michael Andrews’ cover of Tears for Fears’ “Mad World,” all play thematically and lyrically with the complex motifs of the story.

Somehow in the midst of the musings of a confused, possibly schizophrenic teenage boy, Kelly puts no less than the future of humanity at stake. Drawing from Graham Greene’s “The Destructors,” Richard Adams’ Watership Down (the inspiration for Frank, according to Kelly), and The Last Temptation of Christ (what is Donnie Darko if not a teen-angst-ridden, sci-fi version of the Christ narrative?), he carries us to the absolute brink on All Hallow’s Eve. The meaning of all of this is never fully explained, but whatever it means remains important to us. It’s not enough to just like the characters and to wonder. We have to care. As Stephen Jay Gould explained:

But we also need the possibility of cataclysm, so that, when situations seem hopeless, and beyond the power of any natural force to amend, we may still anticipate salvation from a messiah, a conquering hero, a deus ex machina, or some other agent with power to fracture the unsupportable and institute the unobtainable.

The official story consists of a rogue alternate universe that must be resolved through a comic-book logic involving Manipulated Living, Manipulated Dead, The Living Receiver, and others, all explained in Roberta Sparrow’s book, The Philosophy of Time Travel; however, one of the enduring features of Donnie Darko is that even given an “official story,” one can draw many meanings. This is essential to its proven shelf-life.

a.image2.image-link.image2-621-1456 { padding-bottom: 42.6510989010989%; padding-bottom: min(42.6510989010989%, 621px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-621-1456 img { max-width: 1456px; max-height: 621px; } Karen Pomeroy (Drew Barrymore) and Kenneth Monnitoff (Noah Wyle) share a manipulated moment.

a.image2.image-link.image2-621-1456 { padding-bottom: 42.6510989010989%; padding-bottom: min(42.6510989010989%, 621px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-621-1456 img { max-width: 1456px; max-height: 621px; } Karen Pomeroy (Drew Barrymore) and Kenneth Monnitoff (Noah Wyle) share a manipulated moment.My favorite scene in the movie is a short snatch of conversation between Donnie’s teachers Karen Pomeroy (Drew Barrymore) and Kenneth Monnitoff (Noah Wyle). She’s having a snack while he grades papers, presumably in the teacher’s lounge at Middlesex High School. Monnitoff mentions Donnie, chuckling incredulously, and she laughs, agreeing. The scene is so brief as to be completely missable, but it indicates that they’re in on something, that they know the answer. We all know now whether or not Deckard is a Replicant in Blade Runner (1982), and as Christopher Nolan said of whether or not Dom is dreaming at the end of Inception (2010), there is an answer. That the answer doesn’t impede further speculation or meaning-mining is one of the things that makes Donnie Darko so tenacious. As Jake Gyllenhaal says, “What does it mean to you?”

a.image2.image-link.image2-627-959 { padding-bottom: 65.38060479666319%; padding-bottom: min(65.38060479666319%, 627px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-627-959 img { max-width: 959px; max-height: 627px; }

a.image2.image-link.image2-627-959 { padding-bottom: 65.38060479666319%; padding-bottom: min(65.38060479666319%, 627px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-627-959 img { max-width: 959px; max-height: 627px; } When Richard Kelly’s Donnie Darko follow-up, Southland Tales (2006), finally hit DVD, I rented it and watched it six times over the five-day rental. Like Donnie Darko, this is another absurdist eschatological fairy tale, albeit on a much grander scale, with a Pynchon-esque sprawl and a large focus on politics. Where Donnie Darko shows remarkable restraint whenever the plot threatens to spiral out of control, Southland Tales just pushes that much further, reveling in its own chaos and spectacle. It’s a carnival, a war, an end to humanity, a social comment, a political satire, a science fiction romp, and a laugh-out-loud comedy — it bends and blends genres so much as to be “as radical as reality itself,” to borrow a phrase from several sources. Not that it doesn’t have a plot or a focus, it does, but a single viewing will not provide one with all the clues to its many secrets.

This is the way the world ends.

Not with a whimper, but with a bang.

The full story spills over from the film into three prequel graphic novels and borrows liberally from The Book of Revelation, Robert Frost’s “The Road Not Taken,” Jane’s Addiction’s “Three Days,” T.S. Eliot’s “Hollow Man” (quoted in its adapted form above), Kiss Me Deadly, Repo Man, the writings of Karl Marx, and many other places. The full scope of the story is ridiculously vast. As Richard Kelly explains, “I spent the last four years of my life devoted to this insane tapestry of Armageddon,” adding that this was about “getting the apocalypse out of my system once and for all.”

The centerpiece of this “insane tapestry of Armageddon” is a drug-induced music video sequence featuring Iraq veteran Pilot Abilene (Justin Timberlake) recontextualizing “All These Things That I’ve Done” by The Killers. Like the rest of the movie, it’s over-the-top delirious, but its delirium eventually disintegrates into head-hanging melancholy and the beginning of Part VI, “Wave of Mutilation,” the final act, ridden by the motif of “friendly fire” and self-destruction. This movie must have the highest incidence of characters putting guns to their own heads in the history of film-making. It also must have the highest incidence of cameras: They’re everywhere. This movie is nothing if not panoptic.

a.image2.image-link.image2-605-1200 { padding-bottom: 50.416666666666664%; padding-bottom: min(50.416666666666664%, 605px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-605-1200 img { max-width: 1200px; max-height: 605px; } Dwayne Johnson as Boxer Santeros: “I’m a pimp, and pimps don’t commit suicide.”

a.image2.image-link.image2-605-1200 { padding-bottom: 50.416666666666664%; padding-bottom: min(50.416666666666664%, 605px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-605-1200 img { max-width: 1200px; max-height: 605px; } Dwayne Johnson as Boxer Santeros: “I’m a pimp, and pimps don’t commit suicide.”There are so many jarring non sequiturs throughout the film that when Boxer Santaros (Dwayne Johnson) dropped his signature line from the film, I was surprised that I was surprised. Absurdity is the rule here, not the exception. In one scene, Roland Taverner (Seann William Scott) makes Martin Kefauver (Lou Taylor Pucci) put on his seatbelt, just after stopping him from blowing his own head off! Some of the lines that seem to come from out of nowhere are a part of Southland Tales' “self-conscious irony,” as after “officer” Bart Bookman guns down two performance artists he utters, “Flow my tears,” offering a fleeting key to the whole mess. On the side of his police car is the Latin phrase oderint dum metuant: “Let them hate, so long as they fear,” which was a favorite saying of the Roman Emperor Caligula. These are only a few examples of the film’s many references and absurdities.

Like Donnie Darko, Southland Tales seems to have finally found its cult audience, and the newly released Cannes Cut (More Kevin Smith! More Janeane Garofalo!) is furthering its fanbase. Here’s hoping Richard Kelly is on his way to becoming the next Kubrick and not the next Gilliam, because with his first two movies, he proved that he deserves to share their company.

Bibliography:

Gould, Stephen Jay (1999). Questioning the Millennium: A Rationalist’s Guide to a Precisely Arbitrary Countdown. New York: Crown, p. 58.

Kelly, Richard. (2003). The Donnie Darko Book. London: faber and faber, p. xiv.

Rogers, Thomas. (2007, December 19). Everything you were afraid to ask about “Southland Tales” Salon.

Wilson, Robert Anton. (1991). Cosmic Trigger, Volume II: Down to Earth. Las Vegas, NV: New Falcon, p. 29.

February 5, 2021

Algorithm Nation

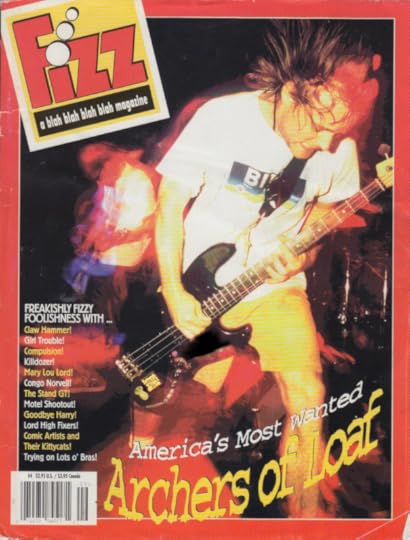

A few years ago, I was having lunch at a bar in Chicago when an Archers of Loaf song came on over the speakers. Excited, I told my partner what a big fan I am, about the first time I saw them at the Crocodile Café in Seattle, and that I saw them a dozen or so times during their first run in the 1990s, once even traveling up to Vancouver to see them play with Treepeople and Spoon. I told her how, fancying myself an indie-rock mogul, I had plans to put together a compilation of Chapel Hill bands, and they were the first to agree to contribute a song. And how I’d gotten to be pretty good friends with their bass player, Matt Gentling, how he’s also a rock climber, and we’ve stayed in touch over the years.

a.image2.image-link.image2-797-605 { padding-bottom: 131.73553719008265%; padding-bottom: min(131.73553719008265%, 797px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-797-605 img { max-width: 605px; max-height: 797px; } Matt Gentling, Arching the Loaf for Fizz Magazine in 1994. If you look closely, you can see a Front Wheel Drive sticker on his bass. That was my zine at the time.

a.image2.image-link.image2-797-605 { padding-bottom: 131.73553719008265%; padding-bottom: min(131.73553719008265%, 797px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-797-605 img { max-width: 605px; max-height: 797px; } Matt Gentling, Arching the Loaf for Fizz Magazine in 1994. If you look closely, you can see a Front Wheel Drive sticker on his bass. That was my zine at the time.As we continued to eat, song after song of theirs came on. Now, as great as they are, the Archers are not a normal thing to hear in public, much less several of their songs in a row. I finally went up to the bar and asked who the Archers of Loaf fan was. No one knew what I was talking about. I explained the same thing I just explained to you, that hearing that many of their songs in a row wasn’t normal. The third person I asked said it was just a streaming service. Somehow the streaming service’s algorithm had gotten stuck on the Archers of Loaf catalog. Not a bad place to get stuck, as far as my lunch was concerned, but it still irked me that I was alone in the experience I was having.

Studies of the digital sharing of music call it “playlistism,” a subcultural ritual that reinforces the links between music and collective identity through the practice of sharing playlists. Assuming that we compile playlists to represent our identities, the sharing of them should show how we present ourselves through music. We didn’t use the old P2P networks to share in this traditional sense. In this way, playlists are more akin to analog mix tapes. We are what we like. In any form, when compiling and sharing our musical tastes, we go from saying, “I like this” to “I’m like this.” In the example above, there’s no one saying anything. Human agency is absent.

Music fans of a certain age belabor the pre-internet era, extolling the effort it took not only to find the good stuff but also to find out about it in the first place. We relied heavily on regionally curated spaces that are less and less influential now, where they exist at all. Local record stores, small weekly papers and zines, indie labels, narrowly focused radio shows, and tiny venues created community and shared knowledge. I do not lament the effort it took to find new music then, but the missed connections like my Archers of Loaf lunch don’t happen when you’re truly sharing an experience. It’s a loss that doesn’t matter to generations since because they never had it to lose. However, it’s one thing to be cut off from each other by choice. It’s entirely another when we don’t even choose it.

The sound that 1990s Seattle is known for seems to be the last historical exemplar that emerged from such a community, formed unfettered or influenced by outside forces. For example, the movement’s flagship label, Sub Pop, started as a zine, a compilation cassette series, and a column in The Rocket, one of Seattle’s local music papers. It was a special time and a special place. Not only did all of this happen in the time untainted by the internet, but the Pacific Northwest is also isolated geographically from the paths of nationally touring bands. I moved to Seattle in the summer of 1993, after the world knew about what was going on in the area, but before it peaked. When it was still what William Gibson would call a bohemia. As he told WIRED in 1995, “I think bohemians are the subconscious of industrial society. Bohemians are like industrial society, dreaming.” He continues:

Punk was the last viable bohemia that we’ve seen, perhaps the last bohemian movement of all time. I’m afraid that bohemians will eventually come to be seen as a byproduct of the industrial civilization; and if we’re in fact at the end of industrial civilization, there may be no more bohemians. That’s scary. It’s possible that commercialization has become so sophisticated that it’s no longer possible to do that bohemian thing.

a.image2.image-link.image2-848-1276 { padding-bottom: 66.4576802507837%; padding-bottom: min(66.4576802507837%, 848px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-848-1276 img { max-width: 1276px; max-height: 848px; } Hands all over… Soundgarden. Photo by Charles Peterson.

a.image2.image-link.image2-848-1276 { padding-bottom: 66.4576802507837%; padding-bottom: min(66.4576802507837%, 848px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-848-1276 img { max-width: 1276px; max-height: 848px; } Hands all over… Soundgarden. Photo by Charles Peterson.I put this question to Malcolm Gladwell years ago, who wrote about youth culture’s commodification in his bestselling 2001 book The Tipping Point, and he responded, “Teens are so naturally and beautifully social and so curious and inventive and independent that I don’t think even the most pervasive marketing culture on earth could ever co-opt them.” Gibson is not so optimistic, or he wasn’t in 1995. Here he talks about Seattle’s music scene, which by that time had had a very public and much-debated commercial co-opting:

Look what they did to those poor kids in Seattle! It took our culture literally three weeks to go from a bunch of kids playing in a basement club to the thing that’s on the Paris runways. At least, with punk, it took a year and a half. And I’m sad to see the phenomenon disappear.

Perhaps this says more about where Gibson’s head was at the time than it does about the creativity of the youth. After all, we’ve seen plenty of cool things happen since 1995, and Gibson was writing Idoru (1996), one of his darker visions of modern culture, saturated with multi-channel, tabloid television and the rampant collecting of purchase data by unscrupulous marketers. Focus groups, surveys, and other ethnographical cool-hunting techniques farm information about users. At best, they seek to find out how people are using products, how they perceive brands, and what their desires are in order to market to and design for them better. At worst, they can seem invasive and downright icky, but they are where our wants wander into the manufactured world.

As these contexts collapse, we lose control of the processes, and we sometimes lose ourselves altogether. Thanks to some anonymous algorithm, I got to hear Archers of Loaf songs for a whole lunch hour one day. Maybe one of them was able to buy lunch themselves.

The Malcolm Gladwell quotation above is from an interview in my new anthology, Follow for Now, Vol. 2, which is coming out soon from Punctum Books. I’ll be sending updates on that in weeks to come.

And you guessed it, this is yet another edited excerpt from my book-in-progress, The Medium Picture. I made a secret page about it on my website, which I’ll be updating as it progresses.

Thanks for reading, responding, and sharing!

Power to you all,

-royc.

January 29, 2021

Audible Arrangements

When I was in the sixth grade, I was in a Vic-20 user’s group. I had a revved-up Commodore Vic-20 with an 8k-expansion cartridge and an external tape drive. Though floppy discs were available, we traded games and software via cassette tapes. There was this device at every meeting called “The Octopus.” It was a port replicator, and when we all plugged in our tape drives for copying multiple programs at once, it looked like a giant, electronic octopus.

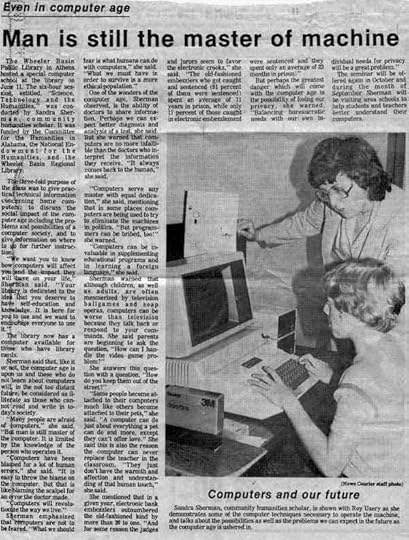

a.image2.image-link.image2-792-600 { padding-bottom: 132%; padding-bottom: min(132%, 792px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-792-600 img { max-width: 600px; max-height: 792px; } I was a computer nerd way before it was cool. Me on an Apple II in The News Courier in Athens, Alabama at age 11.

a.image2.image-link.image2-792-600 { padding-bottom: 132%; padding-bottom: min(132%, 792px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-792-600 img { max-width: 600px; max-height: 792px; } I was a computer nerd way before it was cool. Me on an Apple II in The News Courier in Athens, Alabama at age 11.Looking back at its long reign, the cassette tape is a strange piece of technology. It was horrible for software storage and retrieval. Indexing more than one program on a tape was nearly impossible. The only way to tell where one ended and the next started was by keeping note on the numbers of an unreliable analog counter. At least with music you could hear where the next song started.

The cassette tape, which was cued up in the 1960s to challenge the LP and the 8-track market as the musical format of choice, didn’t take off until it became hyper-mobile in 1979 thanks to the personal, portability of the Sony Walkman. High quality sound as such once required equipment too cumbersome to be carried. The cassette in concert with the Walkman gave everyone their own soundtrack. Their portability and customizability made them the personal electronic item. “The other big advantage of cassettes, of course, was that they were recordable,” Steven Levy elaborates, in an essay celebrating the thirty-year anniversary of the Walkman:

You’d buy blank 90-minute cassettes (chrome high bias, if you were an audio nut) and tape one album on each side. (Since most records were shorter than 45 minutes, you’d grab a song or two from another album to avoid a long dead spot before the tape reversed.) And you’d borrow albums from friends and tape your own. You could also tape from other cassettes, but the quality degraded each time you made a copy made from a copy. It was like an organic form of DRM. Everybody had a box with hand-labeled cassettes and before you went on a car trip, you’d dig in the box to find the tunes that would soundtrack your journey.

a.image2.image-link.image2-440-1064 { padding-bottom: 41.35338345864661%; padding-bottom: min(41.35338345864661%, 440px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-440-1064 img { max-width: 1064px; max-height: 440px; }

a.image2.image-link.image2-440-1064 { padding-bottom: 41.35338345864661%; padding-bottom: min(41.35338345864661%, 440px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-440-1064 img { max-width: 1064px; max-height: 440px; } The magnetic tape was as much a part of the journey as the road. The portability and recordability of cassettes, of which all sounds so very labor-intensive now, made them the precursor to MP3s and iPods and today’s mobile streaming. Personal media, as opposed to mass media, may have been birthed by the book, but the cassette took it to a new level. Just as the book individualized the exchange of stories and information, the cassette tape and its attendant technologies individualized music listening. When the Walkman first came out, it was intended for sharing. The first models released had two headphone jacks. I distinctly remember the first one I listened to having dual jacks. Nevertheless, initial sales numbers indicated that few users were sharing their devices, so Sony retooled its approach. In the ads, Alex Weheliye writes that “couples riding tandem bicycles and sharing one Walkman were replaced by images of isolated figures ensnared in their private world of sound.” As William Gibson puts it,

The tape recorder was the first widely available instrument that allows you to manipulate media. I remember I bought the first Walkman I ever saw... I didn’t even have a tape recorder. I had to go and get someone to make me a tape. The experience of taking the music of your choice and being able to move it through the environment of your choice had just never been available. It felt weirdly subversive. I could walk through rush hour crowds listening to Joy Division at skull-shattering volumes (laughs)… Like you were having this completely different experience that was completely altering the way it all looked, and no one knew.

This source of secret sound, the black box of the personal stereo, is where its cultural meaning truly lies. “People who walk around with a Walkman might seem to signify a void, the emptiness of metropolitan life,” writes Iain Chambers, “but that little black object can also be understood as a pregnant zero, as the link in an urban strategy, a semiotic shifter, the crucial digit in a particular organization of sense.” Where the television brought mass-produced narratives into our home, conflating public and private in its own way, the Walkman allowed us to create our own private narratives in public.

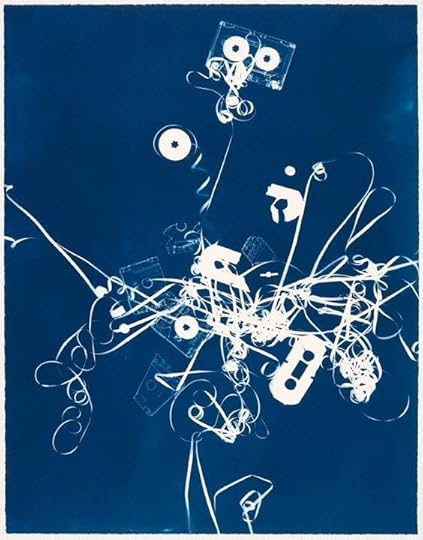

a.image2.image-link.image2-720-564 { padding-bottom: 127.65957446808511%; padding-bottom: min(127.65957446808511%, 720px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-720-564 img { max-width: 564px; max-height: 720px; } Christian Marclay, Untitled (R.E.M. and Sonic Youth), 2008. Cyanotype on 156lb. Cold Press, Aquarelle Arches, 26 x 21 in. (66 x 53.3 cm)

a.image2.image-link.image2-720-564 { padding-bottom: 127.65957446808511%; padding-bottom: min(127.65957446808511%, 720px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-720-564 img { max-width: 564px; max-height: 720px; } Christian Marclay, Untitled (R.E.M. and Sonic Youth), 2008. Cyanotype on 156lb. Cold Press, Aquarelle Arches, 26 x 21 in. (66 x 53.3 cm)The ubiquity of the cassette tape marked the shift from home recording to personal drift, as well as the loosening of the corporate grip on copyright and the individual’s perceived right to copy. “The tape cassette is a liberating force…” Malcolm McLaren proclaimed in the early 1980s. “Taping has produced a new lifestyle.” Long before CD burners became standard equipment on the personal computer and MP3s and streaming liberated music from physical formats altogether, cassettes made recording and customization possible. The formalized mix tape, in McLaren’s words, “allowed for the kinds of communication ultimately threatening to power.”

a.image2.image-link.image2-909-1200 { padding-bottom: 75.75%; padding-bottom: min(75.75%, 909px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-909-1200 img { max-width: 1200px; max-height: 909px; }

a.image2.image-link.image2-909-1200 { padding-bottom: 75.75%; padding-bottom: min(75.75%, 909px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-909-1200 img { max-width: 1200px; max-height: 909px; } “Home taping is killing music,” proclaimed the British Phonographic Industry. It sounds rather quaint now, but the British Phonographic Industry—BPI, the English sister of the RIAA—was incensed. Their attitude was that every blank tape sold was a record stolen. “BPI says that home taping costs the industry £228 billion a year in lost revenue,” McLaren said in 1979, “so they’re not happy that Bow Wow Wow have already reached No. 25 on the singles chart… ” The home-taping controversy was custom-made for McLaren. He was managing Bow Wow Wow who had a hit with a song celebrating home taping called “C-30! C-60! C-90! Go!” The numbers refer to the standard lengths of blank cassettes: 30-, 60-, and 90-minute formats. “In fact,” adds McLaren, “it’s the classic story of the 80s. It’s about a girl who finds it cheaper and easier to tape her favorite discs off the radio… which is why the record companies are so petrified.” “Mix tapes,” adds Ball, “as community-based, localized mechanisms of distribution, pose a threat to the process of managing the flow of ideas...” which in the recording industry’s opinion was strictly the business of the RIAA.

In the decades since, the industry’s paranoia has only increased. Once music was converted to digital files, then compressed to sizes tradable by computers via phone lines, listening to music on a physical format of any sort was doomed. Sony ceased production of the cassette edition of the Walkman on October 25, 2010, but the internet, which has been feeding music to portable players since the late 1990s, continues the path of both personal media and the piracy thereof.

Bibliography:

Ball, Jared, I Mix What I Like: A Mixtape Manifesto. Oakland, CA: AK Press, 2011, p. 125.

Bromberg, Craig, The Wicked Ways of Malcolm McLaren. New York: HarperCollins, 1989.

Chambers, Iain. Migrancy, Culture, Identity. New York: Routledge., 1994, p. 49-50.

Du Gay, P., Hall, S., Janes, L., & Negus, K, Doing Cultural Studies: The Story of the Sony Walkman. London: Sage, 1997.

Eshun, Kodwo, The Co-Evolution of Humans and Technology: A Discussion with William Gibson. In Roy Christopher (Ed.), Follow for Now, Volume 2: More Interviews with Friends and Heroes. Santa Barbara, CA: Punctum Books, forthcoming, Winter 2021.

Hagood, Mack, Hush: Media and Sonic Self-Control. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019, p. 195.

Levy, Steven. “The Blank Generation: 1979 as Audio Cassette Enabler.” Gizmodo, July 15, 2009.

McMahon, Jr., C. J. & Graham, Jr., C. D. Introduction to Engineering Materials: The Bicycle and the Walkman. Philadelphia, PA: Merion Books,1992.

Rasmussen, Terje, Personal Media and Everyday Life, Berlin, Germany: Springer, 2014.

Weheliye, Alexander G. Phonographies: Grooves in Sonic Afro-Modernity. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, p. 135.

If you’re still reading this, I’ll tell you a secret: The above is a part of Chapter 2 “Audible Arrangements” and a part of Chapter 3 “Message in a Bottleneck” of my homeless media theory book, The Medium Picture, edited together into one piece. One of the underlying arguments of the book is that regardless of their intended purposes or uses, we make these technologies do what we want. The parallel evolution of personal media (e.g., mix tapes and the Walkman, the iPod, and the smartphone) and piracy (specifically certain strains of affordance mining and technological appropriation) are two large historical veins in this argument. Let me know what you think.

Anyway, as always, thank you for reading, responding, and sharing.

-royc.

January 22, 2021

Use Your Allusion

On his spoken-word album Bomb the Womb (Gang of Seven) from 30 years ago, Hugh Brown Shü does a great bit about it being 1992, and everything seeming familiar. “What has been will be again,” reads Ecclesiastes 1:9. “What has been done will be done again; there is nothing new under the sun.” That old familiar feeling has been around longer than we’d like to admit, but how do make sense of things that seem familiar but really aren’t?

The first time I heard “The Pursuit of Happiness” by Kid Cudi (2009), I felt like something was a bit off about it. I felt like it had originally be sung by a woman, and he’d just jacked the chorus for the hook. I distinctly remembered the vocals being sung by a woman but also that they were mechanically looped, sampled, or manipulated in some way.

Upon further investigation I found that the song was indeed originally Kid Cudi’s, but that Lissie had done a cover version of it. Her version is featured in the Girl/Chocolate skateboard video Pretty Sweet (2012), which I have watched many times. Even further digging found the true cause of my confusion: A sample of the Lissie version forms the hook of ScHoolboy Q’s song with A$AP Rocky, “Hands on the Wheel.” This last was the version I had in my head and the source of my confusion.

I use this rather tame example to show how easy it is to be unsure about the source of something that we feel like we know. Our memories play tricks, but so do our media. The phenomenon plays out in many other contexts as well.

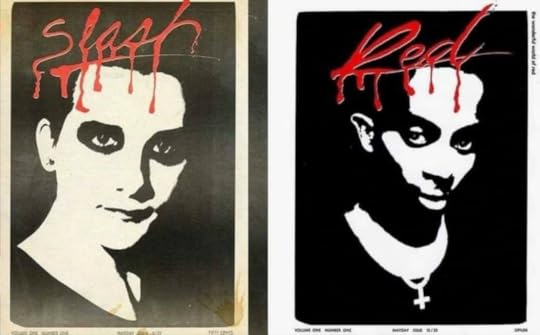

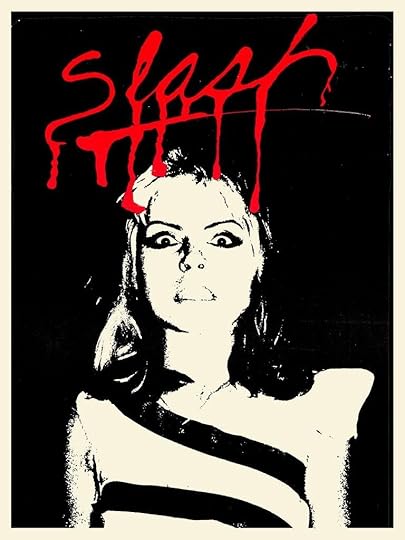

a.image2.image-link.image2-562-906 { padding-bottom: 62.03090507726269%; padding-bottom: min(62.03090507726269%, 562px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-562-906 img { max-width: 906px; max-height: 562px; } Dave Vanian of The Damned on the cover of Slash #1, May 1977, and Playboi Carti on the cover of his record Whole Lotta Red, 2020.

a.image2.image-link.image2-562-906 { padding-bottom: 62.03090507726269%; padding-bottom: min(62.03090507726269%, 562px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-562-906 img { max-width: 906px; max-height: 562px; } Dave Vanian of The Damned on the cover of Slash #1, May 1977, and Playboi Carti on the cover of his record Whole Lotta Red, 2020.The cover art for Playboi Carti’s newest record, Whole Lotta Red (2020) knocks off the lo-fi aesthetic of classic punk magazine Slash. This isn’t the first time Carti’s visual aesthetic has paid homage to punk.

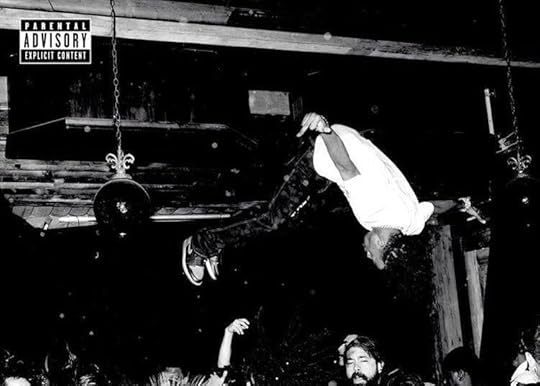

a.image2.image-link.image2-536-750 { padding-bottom: 71.46666666666667%; padding-bottom: min(71.46666666666667%, 536px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-536-750 img { max-width: 750px; max-height: 536px; } Playboi Carti Die Lit (2018)

a.image2.image-link.image2-536-750 { padding-bottom: 71.46666666666667%; padding-bottom: min(71.46666666666667%, 536px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-536-750 img { max-width: 750px; max-height: 536px; } Playboi Carti Die Lit (2018)The stage-diving photo on the cover of his last record, Die Lit (AWGE/Interscope, 2018), recalls a similar SST promo photo of HR of Bad Brains, who was notorious for doing backflips on stage. It’s closer to Edward Colver’s classic 1981 Wasted Youth live shot, which appeared on the back of their Reagan’s In LP (ICI Productions, 1981).

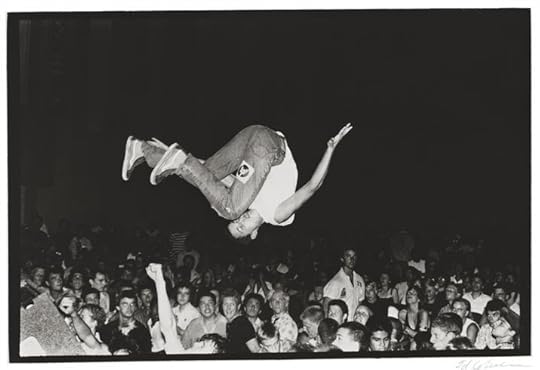

a.image2.image-link.image2-490-716 { padding-bottom: 68.43575418994413%; padding-bottom: min(68.43575418994413%, 490px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-490-716 img { max-width: 716px; max-height: 490px; } Wasted Youth Regan’s In (1981). Photo by Ed Colver.

a.image2.image-link.image2-490-716 { padding-bottom: 68.43575418994413%; padding-bottom: min(68.43575418994413%, 490px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-490-716 img { max-width: 716px; max-height: 490px; } Wasted Youth Regan’s In (1981). Photo by Ed Colver.Such allusions are everywhere in our media. They’re also prevalent in human interpersonal communication. The example I always cite for this comes from Adbusters Magazine founder Kalle Lasn. In his 1999 book Culture Jam, Lasn describes a scene in which two people are embarking on a road trip and speak to each other along the way using only quotations from movies. Based on this idea and the rampant branding and advertising covering any surface upon which an eye may light, Lasn argues that our culture has inducted us into a cult: “By consensus, cult members speak a kind of corporate Esperanto: words and ideas sucked up from TV and advertising.” Indeed, we quote television shows, allude to fictional characters and situations, and repeat song lyrics and slogans in everyday conversations. Lasn argues, “We have been recruited into roles and behavior patterns we did not consciously choose” (emphasis in original).

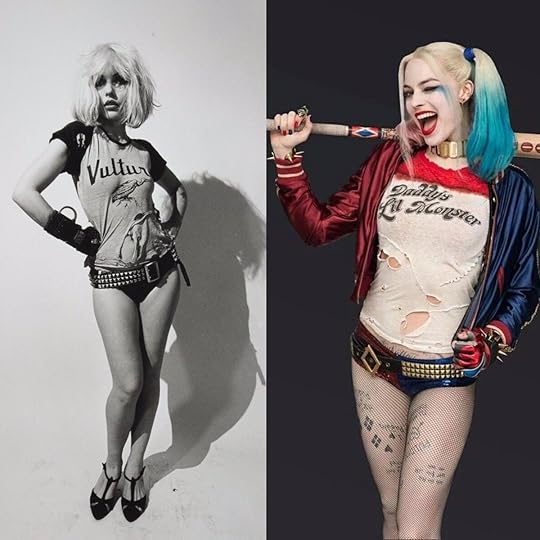

a.image2.image-link.image2-1200-1200 { padding-bottom: 100%; padding-bottom: min(100%, 1200px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-1200-1200 img { max-width: 1200px; max-height: 1200px; } Sometimes it’s not necessarily an homage. Sometimes it’s “inspiration.” Deborah Harry in 1976, and Margot Robbie as Harley Quinn in 2016.

a.image2.image-link.image2-1200-1200 { padding-bottom: 100%; padding-bottom: min(100%, 1200px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-1200-1200 img { max-width: 1200px; max-height: 1200px; } Sometimes it’s not necessarily an homage. Sometimes it’s “inspiration.” Deborah Harry in 1976, and Margot Robbie as Harley Quinn in 2016.Lasn writes about this scenario as if it is a nightmare, but to many of us, this sounds not only familiar but also fun. Our media is so saturated with allusions to other media that we scarcely think about them. A viewing of any single episode of popular television shows Family Guy, South Park, or Robot Chicken yields allusions to any number of artifacts and cultural detritus past. Their meaning relies in large part on the catching and interpreting of cultural allusions, on their audiences sharing the same mediated memories, the same mediated experiences.

In an article from 2015, Devin Blake uses comedy as an example. Pointing to the well-established fact that we no longer define ourselves by what we produce but by what we consume, he marks the rise of what he calls “consumer comedy.” That is, comedy that references other media in order to pack its punchlines. “A lot of what happens in late night TV, for example,” he writes, “seems to involve things that we consume, namely other media like TV shows, movies, and music.” The added knowledge of an allusion is crucial for comedy in that if the audience doesn’t catch a reference, they won’t get the joke. Blake adds the critical insight: “A world of comedy-for-consumers is different than one filled with comedy-for-producers.” The consumption of information is not tethered to the physical world in the way that the production of material goods is.

Marshall McLuhan would frame these media allusions in Gestalt psychology terms as figure and ground. The figure being the overt reference—visual, verbal, or otherwise—and the ground being the invisible referent—the original image or text. “The figure is what appears and the ground is always subliminal,” he wrote. In the visual allusions above for instance, the figure is what you see, and the ground is the source material, the knowledge you have that you’ve seen the thing before, that old familiar feeling. The figure is the artifact at hand, and the ground is the historical context it’s indexing.

a.image2.image-link.image2-1024-768 { padding-bottom: 133.33333333333331%; padding-bottom: min(133.33333333333331%, 1024px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-1024-768 img { max-width: 768px; max-height: 1024px; } Deborah Harry had a Slash cover, too. Issue #5, October 1977.

a.image2.image-link.image2-1024-768 { padding-bottom: 133.33333333333331%; padding-bottom: min(133.33333333333331%, 1024px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-1024-768 img { max-width: 768px; max-height: 1024px; } Deborah Harry had a Slash cover, too. Issue #5, October 1977.So widespread is the use of allusion in our media that it has become its own cultural form. Following allusions on a path through media provides a unique way to understand contemporary mediated culture. Because allusion relies on shared media memories, exploring its use and function in media and conversation helps answer questions of how such mediated messages are stored, conceived, retrieved, and received.

Allusive tactics are not limited to television shows, movies, music, and conversations. Users employ them on social media as a form of “social steganography.” That is, hiding encoded messages where no one is likely to be looking for them: right out in the open. In one study, a teen user has problems with her mother commenting on her status updates. She finds it an invasion of her privacy, and her mom's eagerness to intervene squelches the online conversations she has with her friends. When she broke up with her boyfriend, she wanted to express her feelings to her friends but without alarming her mother. Instead of posting her feelings directly, she posted lyrics from “Always Look on the Bright Side of Life.” Not knowing the allusion, her mom thought she was having a good day. Knowing that the song is from the 1979 Monty Python movie, Life of Brian, and that it is sung while the characters are being crucified, her friends knew that all was not well and texted her to find out what was going on.

a.image2.image-link.image2-627-940 { padding-bottom: 66.70212765957447%; padding-bottom: min(66.70212765957447%, 627px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-627-940 img { max-width: 940px; max-height: 627px; } Howling on hallowed ground: Jake Angeli a.k.a. the QAnon Shaman.

a.image2.image-link.image2-627-940 { padding-bottom: 66.70212765957447%; padding-bottom: min(66.70212765957447%, 627px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-627-940 img { max-width: 940px; max-height: 627px; } Howling on hallowed ground: Jake Angeli a.k.a. the QAnon Shaman.Social steganography is not always so innocuous. Media allusions are arguably more vital on social media where memes are the currency exchanged. Conspiracy theories are spread online through shared texts as their adherents rally around allusions to those texts. The hidden knowledge allows these groups to communicate with each other out in the open without alarming others or stirring up ire or opposition. So-called “dog whistles,” these allusions are shibboleths shared by members and ignored by others. QAnon has largely shared references to their own rumors and accusations, but other texts like William Luther Prince’s The Turner Diaries and the Luther Blissett Project’s novel Q are also touchstones. On the possible connections between the Q of QAnon and the Q novel, Luther Blissett member Wu Ming 1 says, “Once a novel, or a song, or any work of art is in the world out there, you can’t prevent people from citing it, quoting it, or making references to it.”

If we’re all watching broadcast television, we’re all seeing the same shows. If we’re all on the same social network, no two of us are seeing the same thing. The limited access to content via broadcast media used to unite us. Now we're only loosely united via the platform, and the platform itself doesn't matter. What matters is ephemeral and esoteric knowledge, knowing the memes, getting the references, catching the allusions. The references are stronger than their original media vessels. As less and less of us share the ground of each figure, the latter outmodes the former as it shrinks. Whether images from other media or quotations from a text, the allusions themselves outmode the vehicles that carry them.

Bibliography:

Blake, Devin, “The Rise of Consumer Comedy,” Splitsider, 2015 [archived here].

Blissett, Luther, Q: A Novel. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 2003.

boyd, danah & Marwick, Alice E. Social Privacy in Networked Publics: Teens’ Attitudes, Practices, and Strategies. Paper presented at Oxford Internet Institute’s A Decade in Internet Time: Symposium on the Dynamics of the Internet and Society, Oxford, England, September 22, 2011.

Brown Shü, Hugh, Bomb the Womb, New York: Gang of Seven, 1992.

Brunton, Finn & Nissenbaum, Helen, Obfuscation: A User's Guide for Privacy and Protest. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2015.

Frankel, Eddie, QAnon: The Italian Artists Who May Have Inspired America’s Most Dangerous Conspiracy Theory, The Art Newspaper, January 19, 2021.

Greaney, Patrick. Quotational Practices: Repeating the Future in Contemporary Art, Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2014.

Lasn, Kalle, Culture Jam: The Uncooling of America, New York: Eagle Brook, 1999, p. 53.

McLuhan, Marshall, Understanding Media, New York: Houghton-Mifflin.

Molinaro, Matie, McLuhan, Corinne, & Toye, William (Eds.), Letters of Marshall McLuhan, New York: Oxford University Press, 1987.

Pierce, William Luther (as Andrew Macdonald), The Turner Diaries, Charlottesville, VA: National Vanguard Books, 1978.

As you may have noticed, there are a lot of tenuously connected ideas bouncing around in this one. It’s kind of a rough draft. I’ve been trying to apply my study of media allusions to the weird ways information moves around online. This will probably end up in The Medium Picture, but it’s not all there yet, so thank you for enduring my thinking aloud.

a.image2.image-link.image2-783-1456 { padding-bottom: 53.777472527472526%; padding-bottom: min(53.777472527472526%, 783px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-783-1456 img { max-width: 1456px; max-height: 783px; } Graphics by Savage Pencil.

a.image2.image-link.image2-783-1456 { padding-bottom: 53.777472527472526%; padding-bottom: min(53.777472527472526%, 783px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-783-1456 img { max-width: 1456px; max-height: 783px; } Graphics by Savage Pencil.In other news, our edited collection, Boogie Down Predictions: Hip-Hop, Time and Afrofuturism, which is forthcoming from Strange Attractor and the MIT Press, is up on Amazon for preorder already! I’ll tell you more about it as the release date approaches. It’s so dope. Get yours now!

As always, thank you for reading, responding, and sharing!

Power to you,

-royc.

January 11, 2021

Burn the Script: We Need More Voices

After a successful run of movies in the 1980s, Spike Lee used to say “Make Black Film” like a mantra. We saw it in the 1990s with Matty Rich, the Hughes Brothers, John Singleton, and Lee himself. It looks as though it’s back in effect with boundary-bombing work by Ava DuVernay, Ryan Coogler, Arthur Jafa, Donald Glover, Jordan Peele, Terence Nance, Daveed Diggs, and Boots Riley. The latter’s Sorry to Bother You (2018) is not just one of the best movies of the past few years, it’s a statement, a stance, and a hopeful catalyst for change.

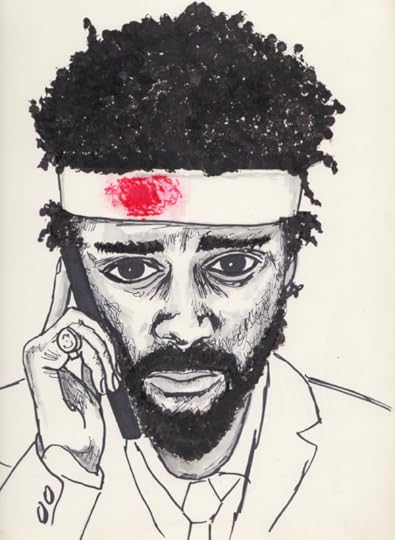

a.image2.image-link.image2-821-600 { padding-bottom: 136.83333333333334%; padding-bottom: min(136.83333333333334%, 821px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-821-600 img { max-width: 600px; max-height: 821px; } Lakeith Stanfield is Cassius Green. Sketchy sketch by Roy Christopher.

a.image2.image-link.image2-821-600 { padding-bottom: 136.83333333333334%; padding-bottom: min(136.83333333333334%, 821px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-821-600 img { max-width: 600px; max-height: 821px; } Lakeith Stanfield is Cassius Green. Sketchy sketch by Roy Christopher.Like any worthwhile project, Boots Riley had been working on this one for a while. The screenplay itself was finished in 2012 and published by McSweeney’s in 2014. I got it and started reading it before I knew it was a movie. Once I heard it had gotten made, I had to stop.

At times—for obvious reasons, I know—you can hear Riley talking directly through these characters. For instance, when Squeeze tells Cassius that it’s not that people don’t care, it’s that when they feel powerless to fix a problem, they learn to live with it. As surreal and wacky as this movie often is, social commentary rarely gets more germane than that.

While I’m writing here about voices in the figurative form, Sorry to Bother You uses them much more directly though still metonymically to make a similar point. The phrase “Sorry to Bother You” applies not only to the telemarketing refrain on which it’s based but also to the hegemony against which it stands.

Another movie that deserves another look is Daveed Diggs and Rafael Casal’s Blindspotting (2018). Less surreal than Sorry to Bother You, Blindspotting is nonetheless a great companion piece. Where Sorry to Bother You uses voices and personal financial gain to highlight its issues, Blindspotting uses gentrification and systemic racism. Visceral yet funny, it’s as poignant as it is poetic. These two movies were being filmed simultaneously in and around Oakland in 2017. It’s hard to imagine how rad that was. Now Diggs and Casal are making Blindspotting into a TV series on Starz with all of the original players. Definitely look out for that.

A couple of years ago I started a screenwriting class. I’d been trying to write a screenplay for several years just to see if I could do it. It’s a very different kind of writing than I’m used to, and I wondered what exactly you put on a page to make things happen on a screen. Since I hadn’t finished the script I started, I thought a class might help me get it done.

Anyway, the teacher of this class made me very uncomfortable. It took me several days after our first class meeting to figure out what it was. I am not easily offended, nor do I do passive-aggressive online reviews (I emailed the institution about this teacher; in fact, much of the description in this post is excerpted from that email), but I couldn’t shake my unease after that one class. My instructor had some very odd attitudes toward movies, stories, and, more specifically, people. His frequent jokes about Harvey Weinstein, Kevin Spacey, and Woody Allen bordered on apologist, while his views on anyone who wasn’t a straight, white male were heteronormative in the extreme and bordered on the sexist, racist, and outright intolerant. He was a nice enough guy and a knowledgeable teacher, so I was trying to figure out what had me so on-edge after the one class. I kept coming back to things he’d said: subtle references, jokes, comments, and recommendations that I finally found I couldn’t ignore. I was unable to attend his class again.

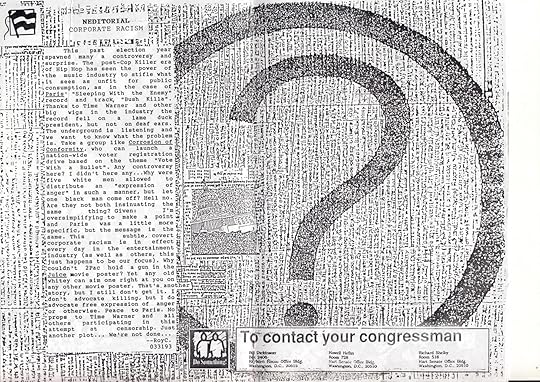

a.image2.image-link.image2-1029-1456 { padding-bottom: 70.67307692307693%; padding-bottom: min(70.67307692307693%, 1029px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-1029-1456 img { max-width: 1456px; max-height: 1029px; } Me writing on this topic for my zine in 1993.

a.image2.image-link.image2-1029-1456 { padding-bottom: 70.67307692307693%; padding-bottom: min(70.67307692307693%, 1029px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-1029-1456 img { max-width: 1456px; max-height: 1029px; } Me writing on this topic for my zine in 1993.One specific thing that instructor said is relevant here. He made the argument that if you’re telling a universal story (i.e., one about love, loss, coming of age, etc.), it doesn’t matter what your background is, your story will connect with an audience. While this assertion is true and could be the basis for a great argument for diversity, he used it to defend the longstanding white-male dominance of storytelling!

One of my other writing heroes, Tina Fey, does a great job of diplomatically explaining this issue to David Letterman on his My Next Guest Needs No Introduction. She uses the SNL writers’ room as a microcosm or cross-section of the audience at large. Explaining that things that might not have played well with mostly (white) men in the room, did once the room became more diverse. So, sketches that had never made it to dress rehearsal before started making it onto the show once there were more women and people of color in the room to laugh at them. That change is such an important shift in gate-keeping, and it applies to all such gates, not just those in comedy.

Hey! A short story I wrote called “Façade” was just published on the Close to the Bone website. It’s about love in the age of Big Data and a facial-recognition reality show called Drawn & Courted. Let me know what you think.

The script I mentioned above finally made it to full draft form recently. It’s called Fender the Fall, and it’s a sci-fi romantic dramedy about a lovelorn physicist going back in time to return the journal of his high-school crush in order to save her and his marriage. Tagline: “You don’t know what you’ve got until you get it back.”

Thank you again for reading, responding, and sharing.

I hope you’re as well as can be,

-royc.

December 28, 2020

Monads and Nomads

We’re all home for the holidays. Looking around the living room at my parents and siblings, I notice that most of them are clicking on their laptops, two are also wearing headphones, one is pecking away at her smartphone. The television is on, but no one’s watching it. Each of us is engrossed in his or her own solipsistic experience, be it a game, a TV show, or some social medium.

a.image2.image-link.image2-643-800 {

padding-bottom: 80.375%;

padding-bottom: min(80.375%, 643px);

width: 100%;

height: 0;

}

a.image2.image-link.image2-643-800 img {

max-width: 800px;

max-height: 643px;

}

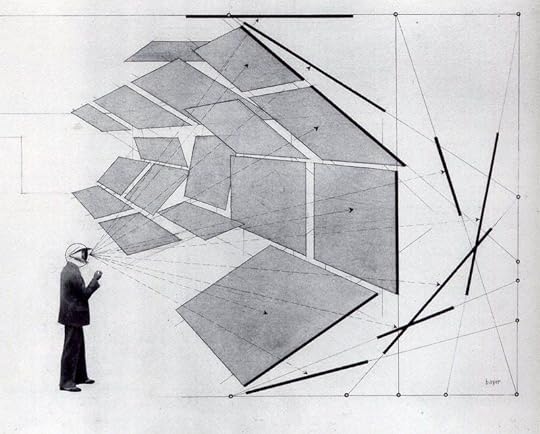

Herbert Bayer, Diagram of the Field of Vision (1930).

I started teaching college as a graduate student in 2002. In the relatively short time since, I have watched as various devices infiltrated the classroom: from no computers or phones, to special rooms with computers called “smart rooms,” and finally to every classroom fully equipped with computers and screens and every student with their own laptop, tablet, phone, and other various gadgets. “Computers aren’t the thing,” says tech executive Joe MacMillan (played by Lee Pace) in the TV show Halt and Catch Fire. “They’re the thing that gets us to the thing.” Well, if that's the case, we have failed to get to the thing in the classroom.

a.image2.image-link.image2-600-800 {

padding-bottom: 75%;

padding-bottom: min(75%, 600px);

width: 100%;

height: 0;

}

a.image2.image-link.image2-600-800 img {

max-width: 800px;

max-height: 600px;

}

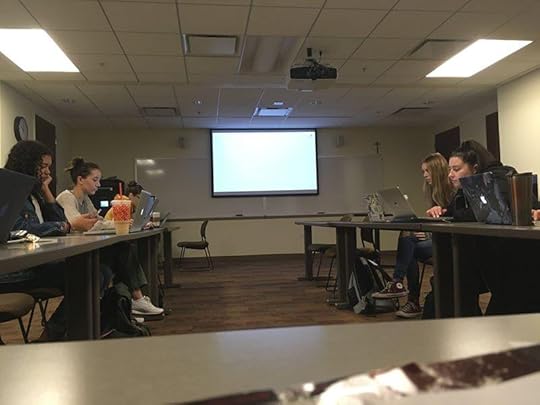

This is a classroom in 2019. The room is equipped with an iMac and a projector. As a lab, its walls are also lined with iMacs. As you can see, the students bring their own laptops as well.There are 50+ computers in this room -- not counting smartphones and tablets. The computers out-number the humans 2-to-1! It was the quietest, least-engaged class I've taught yet.

We gather around some screens and use others individually. Large flat-screen displays connected to projectors serve the former purpose, whereas laptops, tablets, and phones serve the latter. But affordances are not merely infrastructural. They are also behavioral. That is, just because technologies are capable of many things doesn’t mean we use them for all of those things. Moreover, we often use them for purposes for which they were never intended. Many affordances emerge from use.

In our evolution from television screens to computer screens and to mobile screens, we’ve fundamentally changed the infrastructure by which ideas spread. We gather together around big screens to watch passively while, paradoxically, we engage as individuals with smaller screens to connect with each other. Screens at the large scale (e.g., theatre, television, etc.) turn us into nomads, hunting and gathering in groups for news, information, and entertainment. Smaller screens turn us into monads, experiencing media individually or together in accompanied solitude. Feeling disconnected from the world we’ve created is a natural response to the fracturing of mediated experiences. Listening to music, for example, once shared together is now stowed away in portable black boxes, while others are delivered to one another via invisibly connected screens.

a.image2.image-link.image2-894-1280 {

padding-bottom: 69.84375%;

padding-bottom: min(69.84375%, 894px);

width: 100%;

height: 0;

}

a.image2.image-link.image2-894-1280 img {

max-width: 1280px;

max-height: 894px;

}

Marshall McLuhan and a few of his cool frenemies.

The disconnections inherent in our slicing up the world with media operate at different scales and via different channels. Writing before these technologies found their way into our pockets, Marshall McLuhan postulated his “electronic-age” nomads: “Man [sic] the food-gatherer reappears incongruously as information gatherer. In this role, electronic man [sic] is no less a nomad than his Paleolithic ancestors.” Our media networks have since gone global while their attendant media devices have gone mobile. Screens of different sizes and mobility shape our world in distinct ways. That is not to say that one can’t go to the theatre or watch television alone, but the design of these media lends them to sharing, whereas the mobile screen is intended for the individual. That is the price of the monad.

With screens that bring the world inside the walls of the home, the dam between the public and the private was broken. Making sense of the distinction when it comes to the mobile screen is a problem. The telephone, once considered a private matter between two callers, is now often shared in public spaces, or tapped, recorded, and stored for later scrutiny. Like the television or theatre, it can be used in groups, as the boardroom conference call illustrates, but it tends toward solitary use, even if that use often takes place in public places. The telephone, as it has become mobile, has succumbed to the screen, so much so that a phone without a screen is already an antiquated concept. The window to the web and to the world that was once in the domain of the living room converged with every other media form on the computer desktop and is now in pockets and bags dispersed throughout the human world. Given their ubiquity, it isn’t difficult to see the media as an environment: it’s all around us.

a.image2.image-link.image2-692-918 {

padding-bottom: 75.38126361655773%;

padding-bottom: min(75.38126361655773%, 692px);

width: 100%;

height: 0;

}

a.image2.image-link.image2-692-918 img {

max-width: 918px;

max-height: 692px;

}

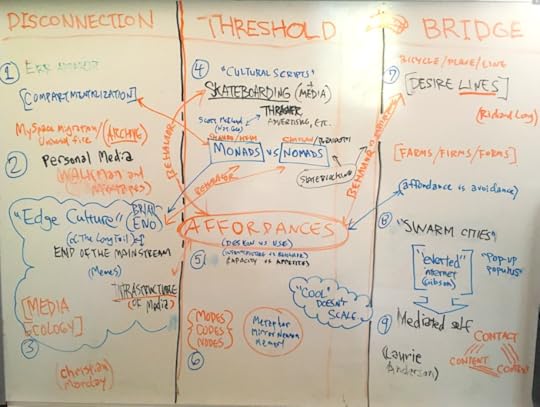

The Medium Picture, mind-mapped for clarity.

In the last 100 years, there have been two major shifts in media technology: the separation of communication from transportation, starting with the telegraph and continuing via radio and other broadcast media, and on to the telephone and the internet, and the move of representation from the page and the stage to the screen. Both of these shifts—the invisibility of networks and the ubiquity of screens—culminated in the rapid spread of television.

Between 1948 and 1955, television invaded almost two-thirds of American homes. In less than a decade, TV became the nexus of media presence and personal life. As powerful as printed language continues to be, it isn’t the only way we understand the world. The computer did not usher in the information age. The transition from page to screen has been privileged by those who study these changes, but the shift to broadcast media was also prefigured by the lecture circuit and stage-plays. McLuhan was fond of saying that the user of media was its content. Predating McLuhan, the Russian filmmaker and theorist Sergei Eisenstein wrote, “The spectator himself [sic] constitutes the basic material of the theatre.” We are as easily lost in words on the page and drama on the stage.

In his Confessions, St. Augustine lamented straying into fantasy, writing,

Stage-plays… carried me away, full of images of my miseries, and of fuel to my fire. Why is it, that man desires to be made sad, beholding doleful and tragical things, which yet himself would by no means suffer? yet he desires as a spectator to feel sorrow at them, and this very sorrow is his pleasure. What is this but a miserable madness? for a man is more affected with these actions, the less free he is from such affections.

St. Augustine’s confessions of losing himself in plays are all too familiar to us. Michel de Certeau wrote in 1984, “Our society has become a recited society, in three senses: it is defined by stories (récits, the fables constituted by our advertising and informational media), by citations of stories, and by the interminable recitation of stories,” his emphases. St. Augustine continues, again describing viewing stage-plays:

What marvel that an unhappy sheep, straying from Thy Flock, and impatient of Thy keeping, I became infected with a foul disease? And hence the love of griefs; not such as should sink deep into me; for I loved not to suffer, what I loved to look on; but such as upon hearing their fictions should lightly scratch the surface; upon which, as on envenomed nails, followed inflamed swelling, impostumes, and a putrified sore. My life being such, was it life, O my God?

The connection St. Augustine feels with the histrionics of the stage is also a disconnection from his everyday life, and more importantly for him, with God. This disconnection is the same one we feel through movies, television shows, and video games.

a.image2.image-link.image2-1219-1456 {

padding-bottom: 83.72252747252747%;

padding-bottom: min(83.72252747252747%, 1219px);

width: 100%;

height: 0;

}

a.image2.image-link.image2-1219-1456 img {

max-width: 1456px;

max-height: 1219px;

}

In his 1996 memoir, A Year with Swollen Appendices, Brian Eno proposes the idea of edge culture, which is based on the premise that

If you abandon the idea that culture has a single centre, and imagine that there is instead a network of active nodes, which may or may not be included in a particular journey across the field, you also abandon the idea that those nodes have absolute value. Their value changes according to which story they’re included in, and how prominently.

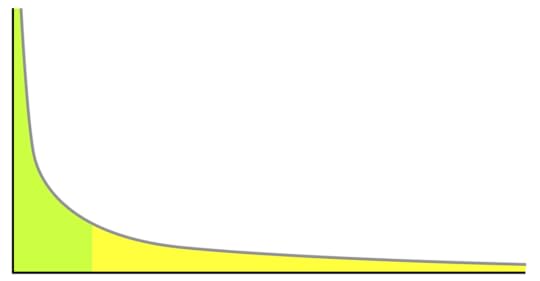

My friend Mark Wieman noted recently that the long tail, the internet-enabled power law that allows for millions of products to be sold regardless of shelf space, has gotten so long and so thick that there’s not much left in the big head. As the online market supports a wider and wider variety of cultural artifacts with less and less depth of interest, the big, blockbuster hits have had ever-smaller audiences. Eno’s edge culture is based on Joel Garreau’s idea of edge cities, which states that the center of urban life has drifted out of the square and to the edges of town. The lengthening and thickening of the long tail plot our media culture as it moves from the shared center to the individuals on the edges.

a.image2.image-link.image2-624-1200 {

padding-bottom: 52%;

padding-bottom: min(52%, 624px);

width: 100%;

height: 0;

}

a.image2.image-link.image2-624-1200 img {

max-width: 1200px;

max-height: 624px;

}

The Long Tail.

I’ve encountered this demographic splintering more and more in the classroom as I try to pick universal media artifacts to use as examples. Increasingly, even the biggest shows and movies I bring up leave most of my students out, and whenever I get into the stuff I actually like, I’m greeted with the sound of crickets.

“The Media,” which once carried the prefix “Mass,” has trickled down from a one-to-many broadcast model to more of a one-to-one, individualized state, from the center to the edges. The long tail used to describe the splintering of artifacts and attention, from blockbuster hits for all, to niche interests for each. Now it also describes the apparatuses via which we consume those artifacts, the gadgets that hold our attention. With the further individualization of our media and the adoption of personal media devices, the postmodern promise of individual viewpoints and infinite fragmentation is upon us. As the screens get smaller, so does the number of media experiences we share.

The medium is only the message at a certain scale, and that scale has diminished.

This fragmentation and its diminishing scale were never more evident than during the November 2016 presidential election. None of the old tools could provide a picture of what was going on. “It was the last time we could trust the mass media as a reliable shared narrative,” declares Chris Riley in his 2017 book, After the Mass-Age. Think about news media. As network news splintered into 24-hour cable coverage, so did its audience and its intentions. Riley writes that instead of trying to get the majority to watch, each network preferred a dedicated minority. “Now you didn’t win the ratings war by being objective; you won by being subjective, by segmenting the audience, not uniting them.” And we met them in the middle, seeking out the news that presented the world more the way we wanted to see it rather than the way it really was. “Analog media such as radio and television were continuous, like the sound on a vinyl record,” Douglas Rushkoff writes. “Digital media, by contrast, are made up of many discrete samples. Likewise, digital networks break up our messages into tiny packets and reassemble them on the other end. Computer programs all boil down to a series of 1s and 0s, on or off. This logic trickles up to the platforms and apps we use.” With the further splintering of social media, we choose the news that fits us best. If we’re all watching broadcast network news, we’re all seeing the same story. If we’re all on the same social network, no two of us are seeing the same thing. The limited access to content via broadcast media used to unite us. Now we're only loosely united via the platform.

a.image2.image-link.image2-762-713 {

padding-bottom: 106.87237026647966%;

padding-bottom: min(106.87237026647966%, 762px);

width: 100%;

height: 0;

}

a.image2.image-link.image2-762-713 img {

max-width: 713px;

max-height: 762px;

}

One world, one market. Illustration by Adam Hayes for Nike 6.0.

In the 1990s, action-sport events like the X-Games and Gravity Games and short-lived websites like Hardcloud.com and Pie.com tried to gather long-tail markets that were too small by themselves into viable mass markets, like a sort of cultural junk bond. It happened with the many musical subgenres of the time. What was the label “alternative” if not a feeble attempt at garnering enough support for separate markets under one tenuous banner? If you can get the kids and their parents invested, you might have a real hit. Then in the 2000s, sub-brands like Nike 6.0 tried again. The “6.0” suffix referred to six domains of extreme sports: BMX, skateboarding, snowboarding, wakeboarding, surfing, and motocross. Whatever the practitioners of such sports might share in attitudes or footwear, they don’t normally share in an affinity for each other. Like the individualized media mentioned above, we remain in our silos, refusing to cross-pollinate in any way.

Even the metaphor of the mainstream is outmoded. It implies groundwater, springs, wells, tributaries, all connected and flowing. There’s a concept in hip-hop regarding your place in the culture that better suits the current state of media at large. To avoid conflict in hip-hop, one creates and stays in their own lane. No merging, no switching, everyone runs parallel. Our larger media culture is much more like a multi-lane highway now than it is a flowing stream of any sort. Everyone—creator and consumer—finds their lane and stays in it, ever enabled by mobile devices with networked screens.

Whether we view ourselves in nomadic groups or as monadic individuals, our experiences collect on the screen like so much data condensation. Michael Heim describes the threshold this way:

Realities are representations continually placed in front of the viewing apparatus of the monad, but placed in such a way that the system interprets or represents what is being pictured. The monad sees the pictures of things and knows only what can be pictured. The monad knows through the interface. The interface represents things, simulates them, and preserves them in a format that the monad can manipulate in any number of ways. The monad keeps the presence of things on tap, as it were, making them instantly available and disposable, so that the presence of things is represented or “canned.”

The surrogate experiences of monads and nomads make up the diverse disconnections implemented by our use of technologies. Large or small, screens deal in illusions, and as porous as they seem, interfaces are still just surfaces.

Bibliography:

Anderson, Chris. (2006). The Long Tail. New York: Hyperion.

Saint Augustine. (1961). Confessions. New York: Penguin.

Carey, James. (1989). Communications as Culture. New York: Routledge.

de Certeau, Michel. (1984). The Practice of Everyday Life. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Eno, Brian. (1996). A Year with Swollen Appendices. London: faber & faber.

Heim, Michael R. (1993). The Metaphysics of Virtual Reality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kleberg, Lars. (1993). Theatre as Action: Soviet Russian Avant-Garde Aesthetics. New York: New York University Press.

McLuhan, Marshall. (1964). Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Riley, Chris. (2017). After the Mass-Age. Portland, OR: Analog.