Conor Byrne's Blog, page 9

December 21, 2014

Anne Stanhope, Duchess of Somerset

Above: Anne Stanhope (c.1510-87), duchess of Somerset.

Anne Stanhope, duchess of Somerset, has long had a negative reputation. Mary Dewar described her in 1964 as 'the terror' of her husband Edward Seymour's household and as 'a hated meddler'. William Seymour, who was a descendant of Somerset's second son by his rejected first wife, characterised Anne Stanhope as a 'proud, domineering woman, with a passion for precedence and an overwhelming interest in personal aggrandizement'. Susan E. James referred, in her biography of Queen Katherine Parr, to Anne's 'myopic arrogance'. Finally, the popular writer Alison Weir wrote of Anne Stanhope's 'monstrous' pride; she was 'a termagant who exercised much influence over her weaker husband by the lash of her tongue'.

Like other elite Tudor women, including Frances Grey, duchess of Suffolk, Anne has been slandered and criticised for perceived faults in her character. Her character has been termed arrogant, overbearing, ruthless and haughty. If she was ambitious, she was, so it goes, monstrously so. If she sought the best for her family, writers believe, it was because of her pride and her desire to out manoeuvre those she disliked. The story goes that she was married to a weak and ineffective man who she was able to dominate and manipulate. In short, she was a 'wicked woman' who was cordially despised by her contemporaries.

Popular culture either views Anne, duchess of Somerset, as a haughty she-wolf or, thanks to The Tudors, as a cunning nymphomaniac. Suffice it to say that neither can be supported with historical evidence. These negative depictions draw on polarising gender stereotypes of women that have featured in societies for millennia. The real Anne Seymour, duchess of Somerset, was a very different woman.

Above: The Duchess of Somerset in The Tudors.

Anne Stanhope was born in around 1510 to Sir Edward Stanhope and his second wife Elizabeth Bourchier. By her father's first marriage, Anne had two half brothers: Richard and Michael. Anne's uncle, John Bourchier, was earl of Bath. At an early age, Anne arrived at court and served in the household of Queen Katherine of Aragon. There, she seems to have met Edward Seymour, son of John and Margery. Edward was knighted in 1523 and became an esquire of the king's household and esquire of the king's body. His first marriage to Katherine Filliol was annulled because Edward questioned the paternity of the elder of his two sons by her. A later manuscript alleged that Katherine had had an affair with her father-in-law John Seymour, but there is no corroborative evidence to support this.

By the spring of 1535, Anne had married Edward Seymour, with whom she had ten children: Edward (who died young); Anne; Edward; Henry; Margaret; Jane; Mary; Katherine; Edward; and Elizabeth. Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn stayed with the couple at Elvetham, Hampshire, in October of that year. Anne had married into an ambitious and enterprising family. Several months after his royal visit, the king was publicly favouring Anne's sister-in-law Jane Seymour, who was perhaps two years older than her. Anne and her husband Edward acted as Jane's chaperones at Greenwich Palace, when the king desired to spend time in his new love's company. In May 1536, Queen Anne was executed and the king married Jane several days later. Anne Seymour became sister-in-law to the new Queen of England and could therefore expect political and social rewards as a result.

Above: Jane Seymour (left) and Katherine Parr (right). At different stages, Anne Seymour was sister-in-law to both of these queens of England.

In June 1536, Edward Seymour was ennobled by the king as Viscount Beauchamp, and following the birth of the queen's son in October 1537, Seymour became earl of Hertford. As countess of Hertford, Anne Seymour enjoyed a prominent and important place at court. She was involved in the reception of Anne of Cleves at Greenwich in January 1540, and attended Katherine Howard when she became queen. The Countess of Hertford enjoyed a close and warm relationship with Mary Tudor, the elder daughter of Henry VIII, with whom she played cards and exchanged gifts. Anne also appears initially to have enjoyed good relations with Katherine Parr, last queen of Henry VIII. She petitioned Queen Katherine for Hertford's return in 1544 when he was engaged in Newcastle overseeing the Scottish Borders.

Anne Seymour's religious devotions were well known and respected. She sent ten shillings to the condemned heretic Anne Askew in 1546, suggesting that the countess harboured radical religious views. In the reign of Edward VI, which sought to eliminate Catholic forms of worship, Anne Seymour was permitted to openly celebrate her Protestantism. Eight different works were dedicated to her between 1548 and 1551. As Retha Warnicke notes, 'more publications were dedicated to her than to any other woman in early Tudor England'. These works were primarily translations of books used to uphold the doctrines of Protestantism. Walter Lynne, who dedicated a book to her, referred to Anne as 'the most gracious patroness and supporter both of good learning and also of godly men'. He found her to be 'the most worthy example of all noble women, whose Godly study all Christian hearts do rejoice in'. Clearly Anne's religious beliefs were well known, while she was respected and esteemed. This respect for her encouraged individuals to seek out her patronage.

Above: Anne Seymour's tomb in Westminster Abbey.

Following Henry VIII's death in early 1547, his nine-year-old son Edward succeeded to the throne as Edward VI. Because of his youth, Edward Seymour, who at this time ennobled himself as Duke of Somerset, became Lord Protector and controlled the regency council appointed by the late king to govern the realm during his son's minority. The Lord Protector experienced growing tensions with his younger brother Thomas Seymour, who married some months later the dowager queen Katherine. This marriage caused considerable scandal and horror at court, as it was viewed as a sign of disrespect to King Henry. Both contemporaries and modern historians blamed Anne, duchess of Somerset, for the brothers' conflict. As Caroline Armbruster noted, 'allowing wives to take the blame for the misdeeds of their husbands was nothing new for sixteenth-century observers', as can be identified with the scapegoating of Anne Boleyn and Lettice Dudley for the actions of their husbands. In the fifteenth-century, Queen Elizabeth Wydeville had been blamed for the execution of her brother-in-law, the duke of Clarence; yet, as Charles Ross asserted, Elizabeth's husband Edward IV 'alone must bear responsibility for his brother's execution'. Armbruster noted that the same could be said for Edward Seymour, duke of Somerset.

Those who disliked Somerset's rule began to attack his wife as a way of attacking him. An anonymous Spanish chronicler described the Duchess of Somerset as 'more presumptuous than Luther', because she claimed precedence over the dowager queen Katherine, who was now her sister-in-law. The chronicler claimed that the duchess urged her husband to execute Thomas Seymour: 'My Lord, I tell you that if your brother does not die, he will be your death'. Writing in 1603, John Clapham specifically alleged that the dislike between the Duchess and the Queen Dowager was the cause of the hatred between Edward and Thomas: 'It hath been reported, a disagreement between Lady Somerset and Katherine [Parr] about precedency, a matter that... breeds many quarrels among women... This feminine quarrel was the first occasion of the breach between the Protector [Edward Seymour] and... his brother [Thomas Seymour]'.

Above: Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset (left), husband to Anne; and Thomas Seymour (right). Anne was blamed for the execution of Thomas Seymour in 1549.

It seems clear that the Duchess of Somerset and the Queen Dowager disliked one another and were estranged from one another, but as Warnicke notes, 'the women did not cause their husbands' disagreements'. Both the Duke and Duchess objected to Thomas Seymour's hasty marriage to Katherine Parr. If anything, it signalled disrespect for the memory of the late king, and the Somersets were not alone in reacting negatively. Mary Tudor, who had formerly been close to her stepmother Katherine, was horrified and distanced herself from the affair. Katherine and the Duke of Somerset experienced conflict with one another. Katherine complained that the duke was ignoring her requests and was disputing with her over his leasing of her dower property, Fausterne Park. It was Somerset, rather than his wife, who Katherine was displeased with, although she appears not to have liked the duchess.

The evidence for Anne Seymour's haughtiness is problematic, for none survives from before the arrest of Thomas Seymour in early 1549. No statements from this time even accused the duchess of urging her husband to order Seymour's death. The Earl of Warwick and his supporters tended to be blamed for Seymour's end. Meanwhile, renowned scholars such as John Cheke, tutor to Edward VI, continued to seek Anne's assistance and support. Cheke wrote to her in praise of her 'singular favour' and expressed thanks for her 'undeserved...goodness'.

From Henry VIII's death to the execution of the Duke of Somerset in January 1552, Anne Seymour, duchess of Somerset, was the most powerful and, arguably, important woman in England. In late 1551, Somerset was brought down by the Earl of Warwick and his allies. Following Somerset's execution for treason, Warwick ennobled himself as the Duke of Northumberland. He ordered Anne Seymour to be imprisoned in the Tower alongside her half-brother Michael, who was executed in February 1552. In the space of a few weeks, the duchess had been imprisoned and had lost both her husband and brother. Her emotional turmoil, anguish and despair can only be guessed at. The duchess remained imprisoned for two years. In August 1553, she was freed by Queen Mary, her close friend.

By January 1559, Anne Seymour had remarried. Her husband was an esquire, Francis Newdigate. Newdigate had served Edward Seymour as a gentleman usher, which is probably how the duchess became aware of him. These years involved scandal for Anne. In 1561, her son Edward's clandestine marriage to Lady Catherine Grey, younger sister of the beheaded Jane, came to light. Because Lady Catherine was popularly viewed as successor to Elizabeth I, the marriage was greeted with horror and controversy. Queen Elizabeth ordered the unfortunate couple to be incarcerated in the Tower of London where, in November 1561, Catherine was delivered of a son, Edward. Catherine gave birth to a second son, Thomas, in February 1563. The marriage had been declared invalid the year before. The boys were declared bastards and barred from inheriting their father's estates. Catherine died in 1568.

Above: Lady Catherine Grey, daughter-in-law of Anne Seymour.

Anne's final years were less troublesome and tumultuous. She died on 16 April 1587, aged around seventy-seven, at Hanworth Palace in Middlesex, and was buried in Westminster Abbey. The Duchess of Somerset was respected and esteemed in her own lifetime for her extensive religious patronage. She was regarded by authors as a pious, godly matron. Her social rank undoubtedly made her an attractive patron. Anne's family loyalty and devotion to her husband, Edward Seymour, were also recognised. She bore him ten children, and enjoyed close relations with Mary Tudor, who later became Mary I. Anne was sister-in-law to two queens of England - Jane Seymour and Katherine Parr. She seems to have been close to Queen Jane, but experienced conflict with Queen Katherine, whom she disliked. Anne did not urge her husband to put to death Thomas Seymour; contemporaries identified the Earl of Warwick as the instigator, while some actually attributed Seymour's end to the Protector himself. Warnicke rightly explains that 'Lady Somerset's reputation as an aggressively proud woman, who greatly influenced the governmental policies of the lord protector is largely a myth'.

Writers who did not know her, including the anonymous Spanish chronicler, identified her as a proud, greedy and insufferable woman who ruled her weak husband and manipulated his decisions. Historians have tended to accept these negative judgements alongside Katherine Parr's letters, in which she admitted her dislike of the duchess. Yet a wealth of other evidence offers a different view of Anne Seymour, duchess of Somerset. Those who did know her viewed her with respect and esteem, and her Protestantism encouraged religious writers to regard her as a pious and virtuous woman. In her own lifetime, Anne Seymour was never accused of promiscuity or wanton behaviour. The portrayal of her in the television series The Tudors, therefore, which depicts her as promiscuous and the mother of illegitimate children, could not be any further from the truth, for the real Anne Seymour was a loving and attentive wife who had 10 children by Edward Seymour.

Published on December 21, 2014 06:17

December 16, 2014

Frances Grey, Duchess of Suffolk: History's Scapegoat?

Above: A portrait identified by some as Frances Grey, duchess of Suffolk.

History remembers Lady Jane Grey, the so-called 'nine days queen', as an innocent teenager brutally sacrificed on the altar of ambition, greed and political treachery. This interpretation runs concurrently with the belief that Jane's family, the Greys, and her Dudley in-laws, were mercilessly ambitious, cold-hearted, scheming and brutal in their quest for power and position. In particular, Jane's mother, Frances Grey, duchess of Suffolk, is usually presented as the mother from hell: physically abusive, she allegedly took delight in bullying her young daughter and treating her with calculated cruelty. But is there any evidence for this dark view of Frances Grey?

High-born Tudor women were prone to misrepresentation and character assassination in their own lifetimes and have been savagely condemned up until the present day. Prominent examples include Anne Boleyn and Anne Stanhope, duchess of Somerset. Frances Grey is a notable example of this trend. Yet, as historical fiction writer Susan Higginbotham notes: 'the real Frances Grey bears no resemblance to the lurid tales about her. Only in our own time has she become a controversial and loathed figure'. Indeed, in her own lifetime, the Duchess of Suffolk was a respected, popular and influential woman who occupied a central place at court. Who then, exactly, was the real Frances Grey, niece of Henry VIII, mother of Lady Jane Grey and wife of the Duke of Suffolk?

Above: Frances's parents: Charles Brandon, duke of Suffolk (left), and his wife Mary Tudor, formerly queen consort of France (right).

Frances Brandon was born on 16 July 1517 at Hatfield, Hertfordshire, the seat of the bishops of Ely. She was the eldest daughter of Henry VIII's close friend and brother-in-law Charles Brandon, duke of Suffolk, by his wife Mary Tudor, younger sister of the king. Frances grew up and was educated at Westhorpe in Suffolk. In the spring of 1533 at Suffolk House in London, sixteen-year-old Frances married Henry Grey, marquis of Dorset. Her mother died at the end of June that same year. Frances served as principal mourner at her funeral in July. It is impossible to know how close she had been to Mary, but Frances surely mourned her mother's death.

After four years of marriage, Frances gave birth to her first daughter, Jane, probably in the spring of 1537 (although Jane's exact date of birth is not known). In novels such as Alison Weir's Innocent Traitor (2006), the ruthlessly ambitious Grey parents react with disappointment and anger to the birth of a daughter, but it is unlikely that this would have been the case in reality. The birth of a daughter might have been disappointing, but Frances was only twenty years old and had many years of childbearing ahead of her. As historian Eric Ives correctly notes, the Grey parents were not in the public eye when their first daughter was born, and neither Jane's date nor her place of birth have been recorded, much less her parents' response to her birth. In August 1540, a second daughter, Catherine, followed, and five years later, Mary was born in 1545. That same year, Frances's father, Charles Brandon, died.

Frances occupied an important place at court during these years. At this time, she attended Queen Katherine Parr, who was her aunt by marriage. She enjoyed a close relationship with Lady Mary, eldest daughter of Henry VIII. Frances's relationship with Queen Katherine is significant, because the queen famously enjoyed close relations with Jane Grey, Frances's eldest daughter. Jane lived in the household of Katherine Parr following the death of Henry VIII, but upon Katherine's death in 1548 Jane returned to her family home at Bradgate in Leicestershire to live with her parents.

Above: Frances's eldest daughters: Jane (left) and Catherine (right).

Frances's relations with her eldest daughter have been, to say the least, controversial. Cultural depictions present Frances as a bullying and cruel mother who treated Jane harshly and mercilessly, physically beating her into submission. This antipathy towards Frances, which stemmed from a belief that she was a poor mother, first emerged in the eighteenth-century, at the same time in which Lady Jane Grey was cast as an innocent martyr and angelic figure, incapable of sin. As Higginbotham notes, however, it was the thirteen-year-old Jane's complaint about her parents to her tutor Roger Ascham in 1550 that has caused the greatest damage to Frances's reputation. Jane complained:

For when I am in presence either of father or mother; whether I speak, keep silence, sit, stand, or go, eat, drink, be merry, or sad, be sewing, playing, dancing, or doing any thing else; I must do it, as it were, in such weight, measure, and number, even so perfectly, as God made the world; or else I am so sharply taunted, so cruelly threatened, yea presently sometimes with pinches, nips, and bobs, and other ways (which I will not name for the honour I bear them) so without measure misordered, that I think myself in hell...

Higginbotham suggests that 'the impact of Ascham's recollection on Frances's reputation simply cannot be understated', for historians and novelists have used this quote from Jane to construct an image of the Grey parents as abusive and tyrannical monsters who inflicted misery on their daughters. Yet, as Frank Prochaska noted, 'Ascham may have 'overblown' Jane's comments to create additional support for his argument that teachers should not take on the role of parents and use corporal punishment to motivate their students to study' (Warnicke). Undoubtedly, Ascham may have exaggerated or even distorted what Jane actually said about her parents. Moreover, as Warnicke notes, it is significant that Ascham's account was published only after the deaths of both Jane and her parents, when he felt it was safe to do so.

Thus, Frances has been characterised as a cruel and abusive mother, and her daughter Jane an innocent and sinless victim of her mother's wrath and hatred. But Alison Plowden is right to point out that Jane's complaints about her parents may actually reflect 'the attitude of a priggish, opinionated teenager, openly scornful of her parents' conventional, old-fashioned tastes'. It is surely going too far to use this 'evidence' to construct such a dark view of Frances Grey, without any other supporting evidence. In fact, the Duchess appears to have been a well-respected and popular figure in society, and there is no evidence that her relations with her younger daughters Catherine and Mary were difficult or problematic.

Moreover, even if Jane's parents did discipline her, it seems to be going too far to characterise Jane as the victim of 'child abuse', as some historians and novelists have. In early modern England, parents were admonished to use corporeal punishment as last resort. Lloyd deMause, an American psychologist, famously put forward the suggestion in his The History of Childhood (1974) that 'the further back in history one goes, the lower the level of child care, and the more likely children are to be killed, abandoned, beaten [and] terrorized'. Other noted scholars, such as Lawrence Stone and Philippe Aries, have provided evidence in support of this. Therefore, even if Jane was physically disciplined by Frances, it does not mean that Frances was 'a child abuser' or 'a bad mother'. To condemn her as such is to apply modern values to a premodern society that had very different views and understandings of childhood.

Above: A portrait for centuries identified as a depiction of Frances Grey (left) and her second husband Adrian Stokes (right), but which actually shows Lady Mary Dacre and her son Gregory Fiennes.

Belief in Frances's supposedly cruel nature has been encouraged by a portrait thought to depict Frances alongside her second husband, Adrian Stokes, whom she married in 1555. The female figure appears greedy, unattractive, grasping and uncaring. Historians have utilised the picture as 'evidence' of the Duchess's unfavourable character. Hester Chapman, believing that the portrait depicted Frances, commented that the woman appears 'greedy', 'actively cruel' and 'coldly indifferent'. Yet the portrait is not of Frances at all, but of Lady Mary Dacre.

Above: A depiction of the execution of Lady Jane Grey. Frances Grey pleaded with Queen Mary to show mercy for both her daughter and husband.

1553 was a momentous year for the Grey family. In May of that year, sixteen-year-old Jane wed Guildford Dudley, a younger son of the Earl of Warwick, and twelve-year-old Catherine married Henry Herbert, son of the earl of Pembroke. Traditionally, it has been assumed that the reluctant Jane was physically beaten by her parents until she agreed to marry Guildford. Only continental sources put forward this story, and as such were probably reflecting sensational rumour rather than fact. English sources make no mention of any coercion. Jane was a member of the aristocracy, and would have been well aware that her marriage was politically motivated to benefit and enhance her family. When writing to Mary Tudor later on, Jane did not blame her parents.

Scholars have debated endlessly about whether the Greys allied with the Dudleys in a conspiracy to usurp the throne from Mary Tudor and replace her with the Protestant Jane. Evidence compellingly indicates that Edward VI, determined to prevent the Catholic Mary from becoming queen, masterminded a 'devise' which proposed that his Protestant cousin Jane succeed to the throne, in place of his illegitimate sisters Mary and Elizabeth. Following Edward's death on 6 July, Jane was proclaimed queen, although a lack of support for her cause amidst the remarkable disorganisation of her regime meant that she was swiftly deposed by Mary, whom many regarded as the rightful queen. Jane was imprisoned in the Tower alongside her husband and her father-in-law Warwick (now duke of Northumberland).

Frances had traditionally enjoyed a close relationship with Queen Mary, and certainly pleaded for her husband's freedom, and perhaps also for that of her imprisoned daughter. On 22 August 1553, Northumberland was executed on Tower Hill. Jane and her husband were found guilty of high treason in November, although the queen was inclined to mercy and intended to spare both from execution. Frances continued to reside at court. How she felt about her daughter's plight can only be imagined. Given the flawed and distorted nature of the 'evidence' for her relations with Jane, it is impossible to tell what the real nature of the relationship between the two was like, but Frances surely experienced considerable emotional turmoil and distress.

Jane almost certainly would have been spared, had it not been for the outbreak of Wyatt's Rebellion in early 1554, an uprising seeking to prevent the queen's planned marriage to the Catholic prince, Philip of Spain. The involvement of Jane's father, the duke of Suffolk, sealed Jane's fate. On 12 February, the sixteen-year-old was put to death on Tower Green, shortly after her husband Guildford's execution on Tower Hill. Eleven days later, Frances's husband was beheaded. In the space of less than two weeks, Frances had lost both her husband and eldest daughter. Her grief, distress and pain can only be imagined.

Frances was now placed in a very difficult position. She pleaded with the queen for clemency, and was allowed to remain at court with her two daughters. Catherine and Mary were respectively thirteen and nine years old when they lost their sister and father. These devastating events must have overshadowed their childhoods and caused both of them considerable emotional pain and torment. In March 1555, the thirty-eight year old Frances remarried. Because Frances had royal blood, that her second husband, Adrian Stokes, was merely her master of the horse, seems to indicate that her remarriage was motivated not by political ambition, but by love. Alternatively, it has been suggested that Frances deliberately chose Stokes as her second husband in a shrewd attempt to ensure that any children she had with her second husband would be too lowborn to be viewed as potential claimants to the throne. Frances remained on good terms with Queen Mary, who allowed her to reside at Richmond, while Catherine and Mary served as maids of honour to their cousin the queen. Frances had a daughter, Elizabeth, by her second husband, who died in 1556.

On 20 November 1559, Frances died at forty-two years of age. She was buried at Westminster Abbey. Her second daughter Catherine acted as chief mourner. Adrian erected a tomb with a recumbent figure in Frances's memory. Frances's funeral was actually the first Protestant service at the abbey after the reconstitution of its chapter. The inscription on Frances's grave reads (in Latin):

Nor grace, nor splendour, nor a royal name,

Nor widespread fame can aught avail;

All, all have vanished here.

True worth alone Survives the funeral pyre and silent tomb.

As Higginbotham relates, Frances Grey, duchess of Suffolk, was not a controversial woman in her own lifetime. She was respected, revered and liked. She has been more slandered in modern times than she ever was in her lifetime. As historian Leanda de Lisle notes, however:

'Since the eighteenth century she [Frances] has been used as the shadow that casts into brilliant light the eroticised figure of female helplessness that Jane came to represent. While Jane is the abused child-woman of these myths, Frances has been turned into an archetype of female wickedness; powerful, domineering and cruel.'

It is time to separate fact from fiction in the turbulent, extraordinary life of Frances Grey, duchess of Suffolk. We lack evidence for how she felt; how she interacted with her daughters; what her relationship with her husband Henry Grey was like. It seems unfair to condemn and disparage her, when there is no evidence to support this negative treatment. Frances was an esteemed and respected figure in her lifetime, and although she may certainly have experienced difficult relations with her eldest daughter, Lady Jane Grey, it seems to be going much too far to view Frances as an abusive mother who cruelly tyrannised her children. If anything, Frances deserves our sympathy and compassion for enduring a life replete with suffering.

Published on December 16, 2014 15:02

16 December 1485: The Birth of Katherine of Aragon

Above: a portrait thought to be of the teenaged Katherine of Aragon (left).

The Archbishop's Palace, Alcala de Henares (right).

On 16 December 1485, Queen Isabella of Castile gave birth to her fourth and final child, Catalina de Aragon, at the Archbishop's Palace at Alcala de Henares, north-east of Madrid. Catalina was, of course, known as Katherine of Aragon from the time of her arrival in England in 1501 to wed the eldest son of the king of England. Katherine was the youngest daughter of the 'Catholic monarchs', Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile. She was named after her great-grandmother Katherine of Lancaster, daughter of John of Gaunt and his second wife Constanza of Castile. Although the royal couple were undoubtedly pleased with the birth of their daughter, a contemporary chronicler, Alfonso de Palencia, reported that they would have preferred a son, given the uncertain health of their only son and heir, Juan.

Katherine was baptised by the Bishop of Palencia shortly after her birth, and was clothed in a white brocade gown trimmed with gold lace and lined with green velvet. During her early years, the princess accompanied her parents on their travels through Spain as they continued the war against the Muslim emirate of Granada. In 1492, Katherine was present at the ceremonial conquest of the capital of the former Nasrid kingdom. Historians have conjectured that her exposure from an early age to the war of conquest and her parents' intense struggle to eliminate heresy from Spain would have bred in Katherine a strong hatred of heresy and a belief in the righteousness of the Roman Catholic Church.

Above: Isabella of Castile (left) and Ferdinand of Aragon (right), parents of Katherine of Aragon.

From an early age, Katherine's personal emblem was the pomegranate, which symbolised fertility (ironically, as it turned out). Although she tends to be represented in popular culture as old, dowdy and dumpy, Katherine was in fact a beautiful girl famously diminutive in stature, with long reddish-gold hair, blue eyes, and a fair complexion. Sir Thomas More wrote of her upon her arrival in England: 'There is nothing wanting in her that the most beautiful girl should have'. Alison Weir noted that Katherine's youthful 'plump prettiness... was to enchant her two future husbands'.

Katherine was educated by a clerk in holy orders, Alessandro Geraldini, and his brother Antonio, both of whom were Italian humanists. She studied arithmetic, Latin (and other languages), classical and vernacular literature, religion, and domestic skills. As Fraser notes, her strong religious upbringing helped to nurture and develop a faith that would sustain her during her turbulent life. The humanist scholar Erasmus was later to explain that Katherine 'loved good literature which she had studied with success since childhood'. Katherine came to be admired by both Erasmus and the Spanish humanist Juan Luis Vives as a model of Christian womanhood.

Above: statue of Katherine at Alcala de Henares (left).

Portrait of Katherine as queen (right).

From an early age, Katherine was groomed for queenship. Henry VII, king of England, proposed that his eldest son Arthur wed the youngest daughter of the Spanish monarchs, to cement the Anglo-Spanish alliance between the two kingdoms. At this time, the Tudor dynasty was viewed as precarious given continuing insurrections against it and the lingering turbulence of the conflict known as the Wars of the Roses, and so an alliance with the prestigious and internationally renowned Trastamara dynasty would bolster the legitimacy and authority of the Tudors considerably. The Treaty of Medina del Campo in 1489 agreed that, when they reached an appropriate age, Katherine and Arthur would marry. Ten years later, on 19 May 1499, they were married by proxy. In the second half of 1501, the fifteen-year-old princess departed for England, where she would spend the remaining 35 years of her life. In November, she married Arthur at St. Paul's Cathedral. Tragically, her husband died only five months later, and Katherine was left a widow - almost certainly a virgin widow - at only sixteen.

Above: Katherine's two husbands: Arthur (left) and Henry, later Henry VIII (right).

After a difficult and turbulent seven-year period in England, Katherine's happiness and future prosperity were secured when Henry VII died and his seventeen-year old son, Henry VIII, succeeded to the throne and chose to marry the beautiful and virtuous Katherine, aged twenty-three. The two were married at Greenwich Palace on 11 June 1509. Although, tragically, Katherine was never to bear her second husband a male heir, the royal couple could not have known that on their wedding day. To Katherine, a golden world beckoned, in which her future as England's queen seemed secured.

Published on December 16, 2014 03:02

December 8, 2014

Culture in the Elizabethan Period: A Guest Post by Alex Taylor

Above: Queen Elizabeth I

Above: Queen Elizabeth Ithe last Tudor Monarch.

The following post is a guest article by Alex Taylor. Alex is a British student about to embark on his history degree. He is particularly fascinated by medieval and early modern English history. In this post, Alex explores the culture of the Elizabethan period, a mesmerising and enigmatic time which saw the flourishing of theatre, the growth of outlandish fashion, and the introduction of new foods into England. Over to Alex!

When we think of the Elizabethan period the initial image we draw up is that of Queen Elizabeth I, the daughter of King Henry VIII, the notorious Tudor king who beheaded two of his six wives. This period inspired a sense of national pride through international expansion and events such as the naval triumph of the Spanish Armada in 1588, which saw England defeat the hated Catholic Spaniards. Historians have often depicted this era as the golden age in England's history, with famous historian John Guy citing the era as 'economically healthier, more expansive, and more optimistic under the Tudors than at any time in a thousand years'.

This fascinating period represented the culmination of the English Renaissance and saw the beginnings of theatre, poetry and music. Some of England's most famous playwrights originate from this exciting and prosperous period, most notably the renowned William Shakespeare and the young Christopher Marlowe, whose works are still performed and studied almost 5 centuries later.

Fashion played a distinctive part in Elizabethan culture. It was a highly fashion conscious age with the royal family and wealthy nobles spending vast amounts of money to keep up with the current trends. Both noblemen and women were indeed expected to be keeping up with the most fashionable clothing of the era, no matter how elaborate or striking they may have been. In fact, the Elizabethans were keen to stand out, displaying some extremely ostentatious and garish arrays of clothing, including large ruffs (pleated neckpieces) and farthingales which gave the wearer an exaggerated, bell shaped skirt. A high status Elizabethan would often display their wealth through their clothing, by wearing heavily jewelled clothes encrusted with precious stones which included pearls, rubies and emeralds. These would be embroidered onto equally luxurious and fine materials such as velvets, silks, and damask. Women's hairstyles were also starting to come into fashion. The Elizabethan period saw the court ladies start to reveal more of their hair with eccentric, brushed back hair adorned with jewelled headpieces. They also indulged in new practices such as hair dying by mixing cumin seeds, saffron and olive oil. This can be related to Elizabethan make-up. High class ladies, especially ones within the royal court, would apply sulphur and lead based products to their face for a clear, pale complexion which was, in Elizabethan culture, highly desirable, Queen Elizabeth herself being an avant user of these popular products. This method was highly dangerous as lead and sulphur are both poisonous and can lead to extreme skin irritation and even death. Kohl was also used to darken eyebrows which would be plucked thinly, along with the hairline, as a large forehead was seen as attractive by the standards of the day. Fashion could also be used to display a message, for example, with the execution of Mary Queen of Scots. On her execution day, Mary wore the colour red, and died in the colour of her faith, Catholicism. As a Protestant nation, this was antithetical to England's beliefs; however, Mary was determined to die in the faith she so strongly believed in.

Many wealthy individuals, including the queen herself, had an array of portraits painted of them. Only the very rich could afford to be painted. The nobles would wear their finest clothes for their portrait and would hang them in their noble houses to show their wealth. Guests and visitors to these grand establishments would be greeted by portraits of the owners displaying their extravagant clothing, which displayed their wealth and high status. Nicholas Hilliard was a popular miniature artist during the Elizabethan period and painted for a number of high profile individuals, including the queen and her successor James I of England. These miniatures were incredibly intricate with a high attention to detail and were extremely popular during this period. They could be given as gifts and even as love tokens.

Lettice Knolly's, Countess of Leicester and Essex

Lettice Knolly's, Countess of Leicester and Essexdisplaying a large, pleated Ruff.

The English Renaissance theatre flourished during the reign of Elizabeth I and the culture of theatre grew incredibly popular with both the higher classes and the working people. It offered Elizabethans from a variety of different classes entertainment and became a definitive part of Elizabethan culture. Theatrical life was largely centred in London, being the capital of England and the most cosmopolitan city in the country. The first permanent theatre, 'The Red Lion' was open to the public in 1567, however, it soon closed down. More successful theatres, such as 'The Theatre' opened in 1576 and became popular with the citizens of London. The Theatre includes a number of importance acting troupes including 'The Lord Chamberlain Men' who employed Shakespeare as actor and playwright. Costumes were often coloured vividly so they would be attractive for the audience; they were also reused and recycled numerous times as they could be expensive to buy and re-dye. Queen Elizabeth herself did not visit any public theatres, as that would not befit her queenly status and dignity, however, Shakespeare was ardently attracted to his royal mistress and her court and proved a faithful servant, performing numerous times for her at court events within his career. It is known from the state papers that the company to which Shakespeare belonged to, in the Christmas holidays of 1598-99, played before Her Majesty at Whitehall and Richmond Palace. They also played again before Her Majesty at the latter palace on two occasions in 1600. The English Renaissance theatre continued to be popular and a large part of cultural society even after the Elizabethan period, into the reign of King James I of England and King Charles I. Its popularity began to decline during the English Civil War when it was associated with royalism and with the rise of Puritanism that saw it as highly sinful and offensive to God.

The culture of this period cannot solely be attributed to just fashion and theatre, but to a large variety of different aspects including food, with new foods being introduced such as potatoes, which were popular among the higher classes until they fell out of popularity. Sugar also became a staple diet in noble families. It was even used to clean one's teeth! Sir Walter Raleigh was famous for bringing tobacco to England, popularising smoking which has continued to be consumed into the twenty-first century. During the Elizabethan period, inhaling tobacco was initially used for medicinal purposes and gradually over the centuries became addictive. It was a lifestyle choice, rather than being chosen for its health benefits, of which there are none.

Overall, the Elizabethan period has provided history with a rich and colourful culture, a culture that encompassed unique clothing, the origins of theatre and the expansion of the English Renaissance movement, exploring the new world, a sense of national pride, and a long prosperous reign under the virgin queen, Elizabeth.

Published on December 08, 2014 11:22

December 1, 2014

A Biography of Lady Catherine Grey

I am very excited to announce that my next book, if all goes well, will be a biography of Lady Catherine Grey, the beautiful and enigmatic younger sister of Lady Jane. Catherine's life was every bit as tragic and turbulent as that of her older sister. She was exposed to violence, brutality and heartbreak at an early age, and she herself died young, at the age of only 27. She was favoured by Protestants during the early years of Elizabeth I's reign as a viable successor to the throne, and in different circumstances, could very well have become queen of England upon Elizabeth's death.

I am aware that Leanda de Lisle has written an excellent study of the three Grey girls. Leanda is a fine historian who writes beautifully, and I am looking forward to reading her work on Catherine. However, there has, as yet, been no individual biography of Catherine herself, which is surprising given her dynastic importance in the 1560s, as well as the personal turbulence and tragedy of her own life. I am very much looking forward to researching Catherine's life in depth, and I am excited to share with you all the fruits of this research.

My first book was a biography of Katherine Howard, wife of Henry VIII. That covered much more familiar territory, and so I believe this project on Catherine Grey will take considerably longer. In view of this, it is unlikely that the biography will be published any time soon, but I am hoping that one day, in the not too distant future, readers will be able to enjoy my biography of Catherine Grey.

Published on December 01, 2014 03:51

November 28, 2014

28 November 1499: The Execution of Edward, Earl of Warwick

Above: Shield of the Earl of Warwick.

On 28 November 1499, Edward Plantagenet, earl of Warwick, was executed on Tower Hill for treason. The son of George, duke of Clarence, and the nephew of both Edward IV and Richard III, Warwick was only twenty-four years of age at his death.

In an article I wrote for the University of St. Andrews's History Society, which can be accessed here, I explored the tragic life of Warwick and what his cruel end demonstrates about the phenomenon of pretenders in early Tudor England. Warwick had been born on 25 February 1475 to Clarence, younger brother of King Edward, by his wife Isabel Neville, eldest daughter of Richard, earl of Warwick, known as 'the Kingmaker'. At the age of three years old, Warwick's father was brutally executed on charges of treason, and the young Edward became earl of Warwick, although the attainder of his father removed Warwick from the line of succession.

In 1484, Warwick's young cousin Edward of Middleham, the heir to the throne, died, and there has been speculation that Richard III named his nephew heir to the throne in consequence. However, historians have pointed out the lack of evidence for this, as well as the illogicality of Richard nominating his nephew as heir when Clarence's attainder had barred Warwick from the throne.

The rule of the House of York came to a bloody end in August 1485, when Richard III was killed by Henry Tudor's forces at the Battle of Bosworth. The Tudors had seized the throne and would not relinquish it until 1603 upon the death of Elizabeth I. The new king shortly afterwards imprisoned Warwick, still only ten years old, in the Tower, an act that appears cruel and callous to us today but which Henry VII surely felt was necessary for the security of his dynasty. If Henry's reign had been peaceful and free of rebellions against his rule, Warwick might reasonably have lived out the rest of his days in obscurity in the Tower. However, the first Tudor king was far from universally loved, and many remained loyal to the Yorkist cause, believing that Henry VII should be deposed and replaced with a member of the House of York.

There has been some speculation about whether Warwick was mentally deficient. The Tudor chronicler Edward Hall famously described him as being kept imprisoned for so long 'out of all company of men, and sight of beasts, in so much that he could not discern a Goose from a Capon'. This statement has subsequently been interpreted to mean that Warwick was retarded. However, Hazel Pierce argued that Hall probably actually meant that Warwick's long imprisonment had made him naive and unworldly, rather than mentally disabled.

From the onset, rebellions and conspiracies surfaced seeking to remove the first Tudor king. The appearance of the pretender Lambert Simnel in 1487 was the first of several conspiracies to usurp the throne from Henry VII and replace him with a Yorkist. Simnel claimed to be the earl of Warwick, leading the king to publicly parade the real Warwick to prove the absurdity of Simnel's pretensions. James A. Williamson suggested that Warwick was merely a figurehead for a rebellion that was already being planned by the resentful and distrustful Yorkists. Simnel, and his cause, was defeated at the Battle of Stoke in June 1487, but the affair had proven to King Henry the danger Warwick represented.

In the 1490s, Perkin Warbeck, another pretender, menaced the king. Upon his imprisonment in the Tower in 1499, Warbeck allegedly attempted to escape alongside Warwick. Both were found guilty, and Warbeck was hanged at Tyburn. Warwick was tried at Westminster in November by his peers, and was found guilty of treason. He was beheaded at Tower Hill on 28 November, aged twenty-four. He was later buried at Bisham Abbey in Berkshire. It was thought at the time that Warwick was executed to appease the Spanish monarchs, who were fearful of sending their daughter Katherine to England to marry Prince Arthur, the king's heir, in view of continuing insurgencies against the monarchy. A later sixteenth-century account, The Life of Jane Dormer (Jane Dormer having been a favourite of Mary Tudor, daughter of Katherine of Aragon), claimed that Katherine experienced considerable remorse for Warwick's death, believing that her marriage to Arthur had been made in innocent blood.

The end of Warwick provides evidence of the considerable vulnerability of the Tudor dynasty and Henry VII's intense paranoia about Yorkist conspiracies against his rule. Although he had married Elizabeth of the house of York, many resented his rule and sought his downfall. Henry's fears are understandable, given that his two immediate predecessors, Edward V and Richard III, had both been usurped and brutally killed. Despite Warwick's death, the future of the Tudor dynasty remained precarious. The king's beloved wife died in 1503. His heir Arthur had died the year before, while another son, Edmund, had died as an infant in 1500. Only the young Prince Henry (later Henry VIII) offered the hope of a peaceful and legitimate succession. The Yorkist threat did not disappear after Henry VII's death. Warwick's cousin Edmund, earl of Suffolk, plotted against the throne and fled abroad, and was executed by Henry VIII in 1513. Lady Margaret Pole, elder sister of Warwick, was brutally executed in 1541 aged sixty-seven on charges of treason, although her innocence has never been in any real doubt. She was beautified in 1886.

Published on November 28, 2014 05:56

November 20, 2014

Fantasies of a Bitch: "Anne Boleyn", Mean Girls, and Culture

Everyone loves a bitch. In one guise or another, bitches have occupied centre stage within every culture in civilisation. Medieval mean girls, ancient vixens, Renaissance shrews and modern Reginas reign supreme throughout their generations, tormenting, tantalising, manipulating, wreaking havoc, creating misery and doing it all with a stunning smile. Regina George, played by Rachael McAdams in Mean Girls, is the archetypal bitch of twenty-first century American culture: manipulative; beautiful; tormenting; ruthless; spiteful; and dizzyingly intelligent. Very much the "Queen Bee" of her school, where she rules the roost and throws every other female into the shade, Regina epitomises modern bitchiness in its every facet. For many, the Tudor equivalent of Regina George in modern America is the very mother of Elizabeth I herself, Henry VIII's second and most infamous wife: Anne Boleyn.

Susan Bordo, in her excellent, original and provocative book The Creation of Anne Boleyn, ponders why Anne continues to be represented in cultural works as hell on earth, asking 'who let the bitch out?' Eustace Chapuys, imperial ambassador during the majority of Henry VIII's reign, created a nightmare vision of Anne that has powerfully shaped, to one degree or another, every cultural representation of her since. Presenting her as 'that accursed she-devil' who used witchcraft and magic to lure Henry into marrying her, Chapuys suggested that Anne was craftily and cunningly planning the deaths of her rival Katherine of Aragon and her stepdaughter Mary Tudor. When she wasn't busy making threats and acquiring poison to do away with enemies, she was spreading Lutheranism throughout the kingdom, luring the king into ridding England of its rightful religion. As Bordo notes: 'What this view of Anne has done is create a vivid, provocative "template" which later generations have responded to in different, often highly polarized ways'. In short, Chapuys portrayed Anne in so vile and hostile a light that represented her as the bitch of the Tudor court, a woman who stopped at nothing to attain her own ends.

Chapuys's influence can be discerned in several contemporary works. Philippa Gregory's novel The Other Boleyn Girl presented Anne as a murderous, malicious and egotistical woman who bullied her siblings into doing what she wanted. She poisoned Katherine and several bishops, slept with her brother, and stole her sister's child in an act of coldblooded cruelty. The portrayal of Anne in Hilary Mantel's Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies has been described as 'lethal' and so 'spitefully ambitious' that 'one feels any king would be justified in beheading her'. Yet there is very little to no evidence to support this. Aside from Chapuy's poison pen, and the later hostile account written by a Catholic priest, Nicholas Sander (who was himself a child when Anne was executed), contemporary accounts did not so vividly and fictionally present Anne as, in effect, the bitch of the Tudor court.

As Bordo notes, the femme fatale, the bitch, is an archetype of all cultures throughout the ages. Just perusing a GoodReads discussion entitled 'Why did everyone hate Anne Boleyn?' brought up the following claims:

'I... think she deserved to die though innocent of adultery and to other sexual misconduct but because she made C. of Aragon suffer so, slowly poisoning her to death, and treating Mary so badly. In those days queens seemed to have a Queen Bee syndrome and Anne was viciously true to form'.

'Today, she would probably be diagnosed as being a sociopath'.

'She was just cruel and crazy!'

'...She was definitely a wack job'.

'She was political and manipulative'.

'She was manipulative... today she would probably be diagnosed with a personality disorder'.

'She was a manipulator for sure'.

'Anne Boleyn was a horrible person... she stole someone's husband... she also treated Mary Catherine's daughter so badly...she deserved what she got in the end'.

What all of these views have in common is their underlying suggestion that Anne Boleyn was able to manipulate Henry VIII. She was the one who wielded power and control in their relationship. She pushed him around and made sure she got her own way. But, aside from the complete lack of evidence for this, this is in many ways an absurd and distorted characterisation of their relationship. Although some historians continue to view Henry VIII as malleable and easily led, they are very few and far between. Historians by and large generally agree that he held absolute power. Upon becoming king, he had two of his father's ministers summarily beheaded. He put to death two of his wives. He treated his elder daughter with remarkable cruelty. He put to death possibly as many as 72,000 people. He ordered the death of a 67-year-old woman innocent of any crime, who was then cruelly hacked to death. He was described as a 'tyrant' and 'worse than Nero'.

It then invites disbelief to suggest, as these readers commenting do, that Anne was able to manipulate and control Henry. People continue to believe that she was responsible for Mary's ill treatment. Yet, when Anne was beheaded, Henry continued to treat his daughter cruelly. There were even rumours that he would put her to death for refusing to recognise him as Supreme Head of the Church and because she refused to agree that her parents' marriage was invalid. This is apart from the complete lack of evidence that Anne had in any way, shape, or form, what resembled a 'personality disorder'.

So why do these views of Anne Boleyn persist? Partly, I suggest, is because history loves a bitch. Bitches are scapegoats. Queens are often closely aligned with bitchdom: consider Empress Matilda, Isabella of France, Margaret of Anjou and Elizabeth Wydeville just in relation to medieval England. They were blamed and condemned for their male relatives' behaviour. There remains a strange and very obvious reluctance to hold Henry VIII responsible for his actions. People automatically assume that he was a weak and easily led man who was manipulated by both his wives and advisers. When she wasn't luring him into bed, people think, Anne Boleyn was encouraging Henry to kill his first wife and her child. Evidence? None.

It's worth remembering, then, when readers stumble across a vengeful, demented Anne hellbent on revenge in a novel, or a particularly negative account of her actions in a serious academic study, or a TV portrayal of her as manipulative and sexually cunning, that these depictions of Anne the bitch are not grounded in, or informed by, any historical evidence. They derive from a culturally constructed archetype that has remained influential in every culture. Everyone loves a bitch, and for many, Anne Boleyn was the bitch of the Tudor period.

Published on November 20, 2014 07:07

November 13, 2014

13 November 1312: The Birth of Edward III

On 13 November 1312, future king Edward III was born at Windsor Castle to Edward II of England and his teenage wife, Isabella of France. Contemporaries wrote that 'on the feast of St Brice in the sixth year of the reign of our lord King Edward, second of that name after the Conquest', the firstborn son to the king and queen of England was born after four years of marriage.

Edward displaced his uncle Thomas of Brotherton as heir to the throne of England. He was only one of two sons born to King Edward and Queen Isabella (the second, John of Eltham, was born in 1316 and died in 1336). Edward would become one of England's greatest kings; in the words of historian Ian Mortimer, 'the father of the English nation'. He was, and is, renowned for his military successes and for restoring royal authority after the decisive and conflict-riven reign of his father.

Edward II's contemporary biographer, the Vita Edwardi Secundi, commented shortly after the birth of Prince Edward that the king's reign had enjoyed only two positives: the prestigious marriage to Isabella and the birth of a prince. These years experienced factional conflict and tensions at court resulting from Edward II's close relationship with Piers Gaveston. Although historians continue to disagree about its exact nature, they generally agree that Edward courted danger through his obvious preference for the company of Piers, to the detriment of the barons at court. Piers was brutally murdered five months before the birth of Prince Edward, in June 1312, and Edward II was keen to exact revenge upon the murderers of his beloved favourite.

Above: Edward II of England and Isabella of France. The image of Edward is not contemporary.

Both the king and queen seem to have reacted with natural delight upon the birth of their son. The birth of a male heir offered the promise of a degree of stability and hope in a fractured, divided realm. On 16 November, the prince was baptised in the chapel of St Edward the Confessor at Windsor Castle by the cardinal-bishop of St Prisca, Arnaud Nouvel. The prince had seven godfathers: Arnaud d'Aux, bishop of Poitiers and papal envoy; John Droxford, bishop of Bath and Wells; Walter Reynolds, bishop of Worcester; Louis, count of Evreux, great-uncle of the prince; John of Brittany, earl of Richmond; Aymer de Valence, earl of Pembroke; and Hugh Despenser the Elder (who, of course, would be executed fourteen years later in the midst of Isabella's attempt to depose her husband).

The French delegation had sought for the prince to be named Louis, but the English refused, and the prince was named after his father and grandfather. Contemporary chroniclers stated that Edward's birth brought some happiness to the king, who continued to grieve for Piers. The queen sent a letter to the city of London announcing the joyous news of the birth of an heir, and the city celebrated in style with dancing and drinking significant quantities of free wine for a week. Edward was raised to the earldom of Chester by his father and was granted numerous castles and manors alongside his own household. The queen was also rewarded with grants of lands in Kent, Oxfordshire, Derbyshire and Northamptonshire.

In early 1327, at the age of only fourteen, Edward would accede to the throne as Edward III of England following the deposition, or abdication (there is some controversy), of his father Edward II, who may or may not have died at Berkeley Castle in September of the same year. Edward III enjoyed a glorious reign that lasted fifty years. He died in 1377, aged sixty-four, and was succeeded by his grandson, Richard II.

Published on November 13, 2014 02:11

November 7, 2014

November 1541: The Downfall of Katherine Howard

Above: A portrait miniature thought to be of Katherine Howard, c. 1540.

For Queen Katherine, the end came quickly and inexplicably. One moment she was England's adored queen, the beloved youthful consort of Henry VIII, renowned for her beauty and virtue. Finally, it seemed, Henry had married a woman who represented everything he desired in a bride: youthfulness, beauty, virtue, chasteness, fertility and, above all, innocence. Katherine seemed to share Katherine of Aragon's loyalty and humility; Anne Boleyn's sensuality and attractiveness; Jane Seymour's demureness and modesty; Anne of Cleves' good sense. Contemporaries often noted Henry's pleasure in his bride and his new found happiness. But throughout her brief reign Katherine was on the edge of a precipice. Her past harboured dark secrets, and she was well aware of the need to conceal them from public attention, if she was to be secure as England's queen.

From her marriage in the hot days of July 1540 to the autumnal beginnings of November 1541, Queen Katherine managed rather well. Recently, historians have come to dismiss the traditional notion that she was an irresponsible, reckless hedonist who spent her days partying and making merry. David Starkey noted her excellent handling of the responsibilities of queenship and credited her with bringing the Tudor family together for the first time. My research similarly suggests that Katherine took her responsibilities as queen seriously, providing for her family, dispensing patronage and maintaining good relations with the royals. She was young and inexperienced, but she moved past these drawbacks to perform her responsibilities as queen earnestly and devotedly.

Above: Possibly Katherine Howard.

Katherine's success, however, depended on her past remaining secret. Despite her apparent successes as queen, Katherine's past haunted her from the moment she married the king. Francis Dereham, a persistent and forceful young man who had been intimately involved with the queen some years before her marriage, arrived at court hoping to win her favour. When he arrived at court in spring 1541, he began boasting of his friendship with the queen and even commented that, were the king to die, he would be sure to marry Katherine. Henry Manox, a musician who had fondled Katherine some years previously, also pressed for appointment.

In context of these dangerous rumours swirling about the queen's past, the emboldened Thomas Culpeper, a groom of the privy chamber to the king, sought out the queen and urged her to meet with him in secret. Possibly he had learned of her murky past and used it to encourage her to bestow favours upon him. Katherine, hoping to continue as England's queen, beseeched him to meet with her only in the presence of her chaperone Lady Rochford. What the two discussed is not known, but in context of dangerous allegations about the queen, it seems more credible that Culpeper had come into knowledge of Katherine's childhood liaisons and was using this knowledge to manipulate her.

Above: Hampton Court Palace, where the queen was abandoned in November 1541.

The royal court departed on a northern progress in the summer of 1541. While they were away, an ardent reformer John Lascelles (who would be burned for heresy five years later) approached the Archbishop of Canterbury with damaging knowledge about the queen. Historians have recently considered the possibility that Katherine was the victim of a reformist conspiracy designed to bring down the conservative Howards. Certainly, it seems too much of a coincidence that Lascelles informed Cranmer of Katherine's past at this time, when rumours were also circulating of her sexual misadventures. The royal couple arrived in London in late October. On 2 November, the disbelieving king was informed of his wife's misconduct before her marriage. Four days later, distraught and emotional, Henry left Hampton Court Palace. He would never see his wife again.

A day later, the queen was confined to her chambers. Katherine quickly guessed what was going on and suffered a full breakdown. Archbishop Cranmer referred to her 'lamentation and heaviness' when he visited her to interrogate her. He seems to have felt pity and compassion for her. The following day, Katherine had recovered sufficiently to answer Cranmer's questions. She admitted liaisons with both Manox and Dereham, but took care to emphasise her youth and vulnerability when these had occurred. She explained that Dereham had pursued her and that she had not enjoyed the affair. In a religious society valuing female chastity and honour, a loss of a girl's maidenhead proved personally and socially damaging. In view of this alongside her clear loyalty to her family, it is questionable whether Katherine would voluntarily and consensually have permitted either man, both of whom were lower in status, intimacies. She denied being Dereham's wife, possibly because canon law required that both vowtakers provide consent.

Both Katherine and Dereham, when questioned, responded that their relationship had not continued following Katherine's royal marriage. However, Dereham asserted that Thomas Culpeper had since succeeded him in the queen's affections. Possibly he was aware of Culpeper's knowledge about Katherine's past, and assumed that the two were close. Katherine denied committing adultery with Culpeper, but did not reveal what she had discussed with him. Possibly, if their discussions had concerned the queen's past and a need to conceal it, Katherine felt reluctant to incriminate herself further by revealing sordid details of her childhood experiences.

Although Culpeper did later admit his hope to commit adultery with Katherine, 'the queen's motives remain opaque, not least because her questioners never pressed Katherine to explain why she met with Culpeper or needed to converse with him, beyond her excuse that he insisted on seeing her'. (Warnicke) Warnicke suggests that Katherine remained silent about the topics of their discussions because 'an admission that she had been attempting to deceive the king by concealing her relationship with Dereham would not have bolstered her defence'. Thus, while she may not have committed adultery, Katherine was guilty of deceit.

The king, meanwhile, experienced extreme sorrow and desolation when faced with knowledge of his wife's misbehaviour. On 12 November his privy council described his distress in a letter to Sir William Paget, resident ambassador in France. As late as April 1542 the king was described as being a different man since hearing of Katherine's past. On 14 November, the queen was relocated to Syon. Eight days later she relinquished the title of queenship, which proved easy enough to do, since she had never been crowned and had been queen purely by virtue of her marriage to the king. The following month, Dereham and Culpeper were sentenced to death, and shortly afterwards executed at Tyburn. Katherine and Lady Rochford were never brought to trial, but were found guilty by act of Attainder. They were executed at the Tower of London in February 1542.

Katherine never did admit to adultery. Although she admitted that she had been unchaste before her marriage, she insisted that she had done no more than converse with Culpeper. Because she admitted to having had a sexual relationship with Dereham, and because she confirmed that she had met secretly on several occasions with Culpeper, both early modern and modern commentators have tended to accept her guilt. If she did not commit adultery with Culpeper, then why did she become involved with him? Possibly 'fear of disclosure would... have made her vulnerable to the machinations of seasoned courtiers like Culpeper, for as she said in her confession about Dereham, 'the sorrow of my offences was ever before my eyes''. (Warnicke)

Above: Tower Green.

Published on November 07, 2014 05:27

October 30, 2014

Egypt's Lost Queens

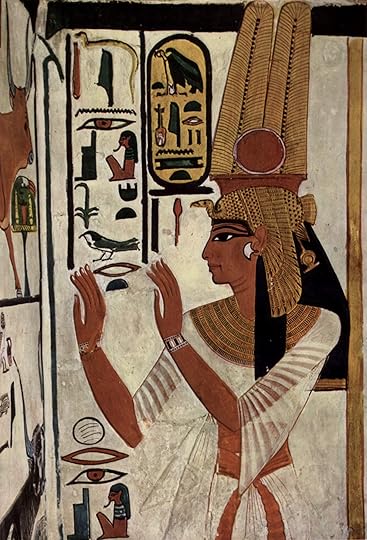

Above: Nefertari, a Great Royal Wife of Ramesses the Great.

Professor Joann Fletcher, Honorary Visiting Professor in the Department of Archaeology at the University of York, recently explored in a fascinating and engrossing television documentary the lives of Egypt's lost queens. Everyone has heard of Cleopatra, last pharaoh of Egypt, a charismatic and alluring woman so stunningly, if melodramatically, portrayed in Shakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra. Professor Fletcher, however, preferred to look at the lives of other powerful female queens. Her documentary revealed the inspiring and considerable power and authority such women wielded in Ancient Egypt.

Nefertari, as depicted in the image of the tomb wall above, was one such woman. She was one of the Great Royal Wives, or principal wives, of Ramesses the Great, who was himself celebrated and recognised as one of the greatest and most powerful pharaohs of the Egyptian Empire. Nefertari's name means 'the beautiful one has come'. Her birthdate is unknown, and she died around 1250 BC. She was possibly related to Pharaoh Ay, and married Ramesses before he became pharaoh, bearing him at least four sons and two daughters. Her eldest son, Amun-her-khepeshef, was Crown Prince and Commander of the Troops. Nefertari first appeared as the wife of Ramesses II in official scenes during the first year of his reign. She is depicted behind her husband in the tomb of Nebwenenef, high priest of Amun, as Ramesses elevates Nebwenenef to position of High Priest of Amun during a visit to Abydos.

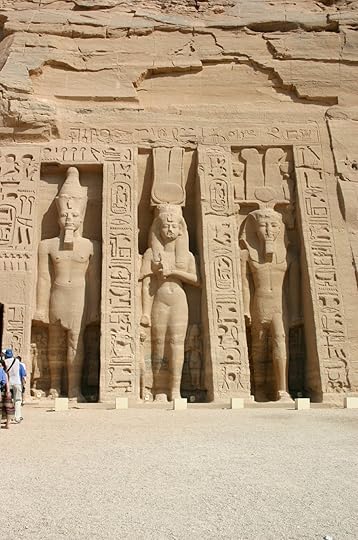

Furthermore, Nefertari is a central presence in the scenes from Luxor and Karnak, two cities in Ancient Egypt. Her roles as mother and goddess are highlighted, as she is depicted leading the royal children and appearing at the Festival of the Mast of Amun-Min-Kamephis. But it was her role as consort of the Pharaoh that was most frequently emphasised in statues. The small temple in Abu Simbel was dedicated to her and the goddess Hathor. Her prominence at court can be discerned in cuneiform tablets from the Hittite city of Hattusas, in which she corresponded with the king Hattusili III and his wife Pudukhepa. Nefertari sent gifts to Pudukhepa and referred to her as 'my sister' and 'Great Queen of the Hatti land'. She later appeared in the inaugural festivities at Abu Simbel in year 24. Following her death, she was buried in tomb QV66 in the Valley of the Queens.

Above: Temple of Nefertari at Abu Simbel.

Nefertiti was another remarkable female ruler in Ancient Egypt. She was the chief consort of Akhenaten, Pharaoh of Egypt. They have usually been associated with a religious 'revolution', in which only one god, Aten (the sun disc), was worshipped, in contrast to previous practice. With her husband, Nefertiti arguably reigned during the wealthiest period in the history of Ancient Egypt. Scholars currently debate whether Nefertiti reigned herself briefly as Neferneferuaten after the death of her husband and before Tutankhamun's accession. Her titles included: Hereditary Princess; Great of Praises; Lady of Grace; Sweet of Love; Lady of the Two Lands; Main King's Wife; Great King's Wife; Lady of All Women; and Mistress of Upper and Lower Egypt.

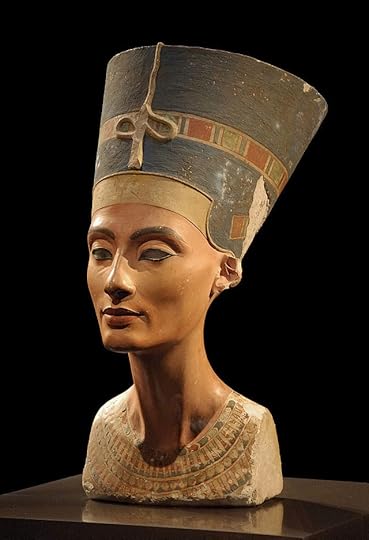

Above: Nefertiti.

Nefertiti was born circa 1370 BC and died circa 1330 BC. Her parentage is not known with certainty, although some have theorised that she was the daughter of Pharaoh Ay. She had six daughters with Akhenaten, although the date of their marriage is unknown. Nefertiti appeared in many scenes, in Thebes for example, supporting her husband, worshipping the Aten. In other scenes, she assumed the prerogative of the king in smiting the enemy, while captive enemies decorated her throne. The emergence of the cult of the Aten changed Egypt's polytheistic religion to a religion perhaps best described as a monolatry (the depiction of a single god as an object for worship), or henotheism (one god who is not the only god).

Many theories have existed about Nefertiti's death. Traditionally, she was thought to have vanished from the historical record around Year 14 of her husband's reign, with no mention of her thereafter. Explanations included a sudden death (possibly from a plague sweeping the city), or a natural death. During her husband's reign, she enjoyed unprecedented power and authority. Possibly she became co-regent by the twelfth year of Akhenaten's reign, and was therefore equal in status to the Pharaoh. Some now believe that she was the ruler Neferneferuaten and so may have exerted influence on the younger royals. Possibly, then, her influence and also life ended around the third year of Tutankhamun's reign (1331 BC). Others believe that her husband continued to rule alone until the last years of his reign, with his wife by his side, and therefore the rule of the female pharaoh Neferneferuaten must be placed between Akhenaten's death and Tutankhamun's accession.

Regardless of when she died, Nefertiti's mummified body has never been found. Joann Fletcher suggested in 2003 that the Younger Lady, one of two female mummies inside the tomb of Amenhotep II in the Valley of the Kings, may have been Nefertiti's mummy. Egyptologists have dismissed Fletcher's claims, however, by noting that ancient mummies are almost impossible to identify without having DNA. Nefertiti's conclusive identification is impossible given that the bodies of her parents and children have never themselves been identified. Others have questioned whether the mummy is even female. Despite this controversy, Nefertiti remains iconic. After Cleopatra, she is the second most famous Queen of Ancient Egypt in the Western imagination.

Above: Hatshepsut.

Hatshepsut was another extraordinary female ruler in Ancient Egypt. Her name means 'foremost of noble ladies'. She was born about 1508 BC and died 1458 BC, aged around fifty. She was the fifth pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty. She officially ruled jointly with Thutmose III, and was the chief wife of Thutmose's father, Thutmose II. Hatshepsut was daughter of Thutmose I and his primary wife Ahmes. Egyptologists tend to regard her as one of the more successful pharaohs since she ruled longer than any other woman of an indigenous Egyptian dynasty.

Hatshepsut enjoyed several major accomplishments during her lifetime. Firstly she established the trade networks that were disrupted during the Hyksos occupation of Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period (1650-1550 BC). She also oversaw preparations and funding for a mission to the Land of Punt, an Egyptian trading partner known for producing and exporting gold, aromatic resins, wild animals, ivory, ebony, and blackwood, and was known in some cases as 'the land of the god'. Her foreign policy has often been seen as having been peaceful, although she may have led military campaigns against both Nubia and Palestine.

Hatshepsut has also been recognised as one of the most prolific Ancient Egyptian builders, for she commissioned hundreds of construction projects throughout both Upper and Lower Egypt. She employed the great architect Ineni, who had worked for her father, husband, and for the royal steward Senemut. A remarkable quantity of statuary was produced during her reign, meaning that, today, almost every major museum in the world has Hatshepsut statuary. She had monuments constructed at the Temple of Karnak, and restored the original Precinct of Mut, the ancient great goddess of Egypt, at Karnak that had been ravaged by the foreign rulers during the Hyksos occupation. Obelisks were ordered to celebrate her sixteenth year of rule, while she built the Temple of Pakhet at Beni Hasan. The masterpiece of her building projects was a mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri.

In comparison with other female pharaohs Hatshepshut's reign was longer and more prosperous. She is generally recognised to have been successful in her warfare and inaugurated an era of peace that lasted for some time. She brought great wealth to the empire and re-established international trading relationships.

The experiences of Nefertari, Nefertiti and Hatshepsut, alongside the more famous Cleopatra, suggest that these female pharaohs should not be seen as 'lost'. They were authoritative, powerful women who wielded tremendous influence in their own lifetimes. This influence can still be discerned and appreciated today, in for example visiting their mesmerising building projects.

Above: Colonnaded design of Hatshepsut temple.

Published on October 30, 2014 16:48