Conor Byrne's Blog, page 2

May 19, 2017

19 May 1536: Anne Boleyn's Execution

We have no way of knowing whether Anne Boleyn was greeted by warm sunshine and birdsong as she took her final steps out of the queen's apartments and towards the scaffold within the Tower of London. Likewise, it is impossible to say whether the queen and her attendants were showered with rain, or whether blustery winds tugged on the trains of their gowns. Films and television often portray Anne's execution day as beautifully sunny and warm (think Anne of the Thousand Days; The Tudors; Henry VIII, etc.), but contemporary writers writing about that momentous day were uninterested in the finer details of the weather, and it is questionable whether Anne Boleyn herself was all too concerned if her final moments were spent in brilliant May sunshine or unseasonable damp and cold. 19 May 1536 was the date on which an unprecedented act would take place: the execution of an English queen consort, the first of its kind.

Four days earlier, she had been tried and found guilty of adultery with five courtiers, treason and plotting the death of her husband, Henry VIII. Two days later, her marriage had been annulled (probably on the grounds of her sister Mary's liaison with the king a decade earlier) and her co-accused had themselves gone to the scaffold, including her brother George, lord Rochford. Anne's tortuous imprisonment in the Tower had been, understandably, emotionally charged for her: she had experienced hope, despair, confusion, sorrow, anxiety and humour. Sir William Kingston, the constable of the Tower, had been baffled by her behaviour: one minute she seemed ready and willing to die, he reported, but the next minute she would collapse in a fit of weeping. Archbishop Cranmer, who had received patronage and support from Anne and her family, had provided Anne with hope that she would be permitted to spend the rest of her life in a nunnery, but that hope was nothing more than a cruel illusion. As May 19 dawned, the queen was aware that her life would indeed end within the walls of the Tower, rather than behind the walls of a nunnery, but at least her death would be caused by decapitation, a relatively quick form of execution, rather than by being burned at the stake, as was originally feared.

According to Edward Hall, the lawyer and chronicler, Anne spoke these words on the scaffold:

Good Christen people, I am come hether to dye, for accordyng to the lawe and by the lawe I am iudged to dye, and therefore I wyll speake nothyng against it. I am come hether to accuse no man, nor to speake any thyng of that wherof I am accused and condempned to dye, but I pray God saue the king and send him long to reigne ouer you, for a gentler nor a more mercyfull prince was there neuer: and to me he was euer a good, a gentle, & soueraigne lorde. And if any persone wil medle of my cause, I require them to iudge the best. And thus I take my leue of the worlde and of you all, and I heartely desyre you all to pray for me. O lorde haue mercy on me, to God I comende my soule.

Mercifully, Anne's head was swiftly 'stryken of with the sworde', and she was buried at the chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula. Modern readers might wonder whether Anne's last words in praise of her husband were spoken with irony, or contempt, or humour: but her speech actually followed contemporary protocol in almost every sense. The condemned was expected to praise the king and the justice of his law; to speak out against it threatened infamy and ruin to the condemned's family, and might result in an even harsher mode of execution for the condemned. Whether or not Anne was thinking of her daughter, the infant Elizabeth, when she spoke these words is uncertain, but it is possible that she was desirous of securing as stable a future as possible for her soon-to-be motherless, bastardised daughter. Criticising Henry or questioning his justice in public would hardly achieve that. In asking those present to judge the best of her case, however, Anne left the events of her ruin open to question and open to debate.

The unexpected accession of her daughter, Elizabeth, in 1558 meant that Anne's memory could be honoured and her status as queen of England celebrated, but had it not been for Elizabeth's accession, it is possible that Anne would have been confined to history as an unpopular and possibly adulterous queen. Her name was rarely spoken, at least in public, during the reigns of Henry VIII and Edward VI, and Mary I, who understandably blamed Anne for her harsh treatment during the 1530s, openly referred to Anne as an adulteress and heretic, and was desirous of preventing her half-sister Elizabeth from succeeding her. Even during Elizabeth's reign, moreover, a degree of ambivalence remained. Protestant writers, including John Foxe, dutifully celebrated Anne's piety and charity, but they refrained from discussing the events that led to her downfall and execution. To do so, perhaps, would cast doubt on Henry VIII's motives. Elizabeth herself, who gloried in her father's memory, rarely referred to her mother and, unlike her half-sister Mary (who had proclaimed her parents' marriage to be valid upon her succession to the throne in 1553), Elizabeth did not legitimise herself and did not declare her parents' union to be valid. In doing so, she left herself vulnerable to accusations of bastardy for the rest of her reign, and in Catholic Europe, her cousin Mary Queen of Scots was always regarded as the rightful queen of England, by virtue of both her unquestioned legitimacy and her Catholic faith.

Above: Elizabeth I.

Above: Elizabeth I.Why Elizabeth did not restore the legitimacy of her parents' marriage is understandable: her father had approved the dissolution of his marriage to her mother and had sanctioned her subsequent execution on charges of treason and adultery, charges that called into question Elizabeth's parentage. To have retrospectively declared the marriage to be lawful, rather than null and void, would have effectively cast Henry VIII as a murderer. As mentioned earlier, Elizabeth fondly recalled her father's memory on several occasions during her reign, including at her coronation festivities. Her relative silence concerning her mother need not be taken as evidence that she was ashamed of her, for there is other evidence to suggest that, privately at least, she honoured her mother's memory. Moreover, the likes of Foxe probably encouraged Elizabeth to view Anne Boleyn, correctly or otherwise, as an important patron and supporter of the Protestant faith, a faith with which Elizabeth identified with increasing militancy as her reign saw the introduction of gradually harsher measures against Catholics.

The silence that followed Anne Boleyn's death well into the reign of Elizabeth stands in stark contrast to today: as Susan Bordo notes, in modern times Anne is undoubtedly the most famous of Henry's wives. Countless biographies, novels, films, television dramas and documentaries are produced about her every year. She has been portrayed in virtually every guise, from revolutionary reformer to hapless victim, from scheming adulteress to feminist icon, from deformed witch to courageous intellectual. Everything about her is debated: her date of birth, her hair colour, her facial features, her religious opinions, her character, her sexual life, her relations with her siblings, her political activities, her relationship with Henry VIII and, most explicitly, the reasons for her downfall. She continues to make the headlines in newspapers, as witnessed recently with newfound theories about her portraiture. There is an insatiable lust and desire for all things Anne Boleyn.

I recommend Susan Bordo's original and fascinating book, The Creation of Anne Boleyn, for an engaging analysis of Anne's status as an icon and her legacy, a legacy that transcended her brutal and bloody death in May 1536. Bordo also makes the important point - and one worth remembering - that "Anne Boleyn", in her many cultural guises, has by now largely overshadowed the historical remnants of the real Anne Boleyn. With so little documentary evidence for the historical figure - as noted earlier, even her date of birth is open to question - it is no wonder that historians, novelists and filmmakers alike delight in using their imaginations to fill in the gaps. It is the scarcity of surviving records that account for why Anne is such a polarising figure and why she has been portrayed in virtually every guise imaginable, even those of vampire and prophetess.

Published on May 19, 2017 02:58

May 3, 2017

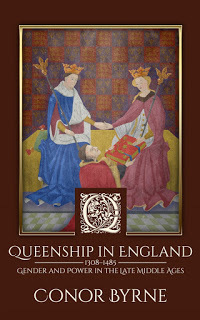

Kindle Countdown: Queenship in England

![Queenship in England: 1308-1485 Gender and Power in the Late Middle Ages by [Byrne, Conor]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1493902354i/22664618.jpg)

*Exciting Opportunity* If you own a Kindle, today and tomorrow, you can buy my book Queenship in England 1308-1485 for only 99p on Amazon UK and 99c on Amazon.com. It's a great deal and well worth taking advantage of.

Amazon UK link: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Queenship-En...

Amazon.com link: https://www.amazon.com/Queenship-Engl...

If you don't own a Kindle, rest assured: you can still buy the book in paperback, but please note that the Amazon countdown deal doesn't apply to paperbacks, only to Kindle. I hope you think this a worthwhile deal - if you're looking for something to read, I'd love you to read (and review) the book!

Published on May 03, 2017 06:47

April 23, 2017

23 April 1445: The Wedding of Henry VI and Margaret of Anjou

On 23 April - some sources suggest 22 April - 1445, Henry VI married Margaret of Anjou at Titchfield Abbey in Hampshire. The king was twenty-three years old and his new bride was fifteen. Margaret, who was born in Lorraine, had arrived in England on 9 April and met Henry shortly afterwards. The marriage was expressly designed to achieve peace between the warring kingdoms of England and France, although Margaret's dowry was rather unimpressive.

On her wedding day, the king provided Margaret with jewels, including a gold wedding ring. On 28 May, Margaret entered London and was crowned queen at Westminster Abbey two days later. The surviving evidence indicates that Henry and Margaret felt affection, possibly love, for one another, and the records demonstrate that king and queen cooperated on matters of policy during the early years of their marriage. However, Margaret's inability to conceive contributed to growing tensions at court and in the realm more generally. This childlessness, coupled with the perceived shortcomings of the Anjou alliance, meant that Margaret was unable to enjoy popularity among her subjects.

In 1453, eight years after her marriage, Margaret finally conceived and gave birth to a son, Edward, on 13 October. However, the birth of her child coincided with Henry VI's illness and compelled Margaret to take a politically active role at the centre of government. Her bid for the regency failed and the duke of York was made protector. As is well-known, Henry's incapacity and the ensuing crisis of kingship led to civil war.

In my book, Queenship in England - which can be purchased here - I examine Margaret's controversial tenure as queen:

Henry VI’s incapacity created a crisis at the centre of governance. Contemporaries feared the consequences of the king’s infirmity: ‘the reame of Englonde was out of all governaunce… for the kyng was simple… held ne householde ne meyntened no warres’. It is not true that the queen was an avaricious, grasping woman determined to enjoy power irrespective of the consequences; however, her husband’s collapse placed her in an ambiguous and uncomfortable position. Indeed, it was circumstances, including the collapse of her husband and growing discontent among the nobility, that required the queen to play a more directly political role after 1453, alongside her realisation that her son’s inheritance had to be safeguarded.

Published on April 23, 2017 04:32

March 16, 2017

The Execution of Lady Anne Lisle

I have visited Winchester several times. It is a beautiful and historic city with much to see for the history lover, including the grand and imposing Winchester Cathedral, where Mary I married Philip of Spain in 1554. However, I did not know that on 2 September 1685 a landed gentlewoman of the county was publicly executed in Winchester for harbouring fugitives after the defeat of the Monmouth Rebellion.

Lady Alice Lisle was the last woman to be beheaded in England. The unlucky women that were executed by beheading in English history were mostly queens: Anne Boleyn, Katherine Howard, Lady Jane Grey and Mary Queen of Scots. Margaret, Countess of Salisbury, niece of Edward IV and Richard III, was beheaded at the age of sixty-seven. In 1685, Alice Lisle was of a similar age to the unfortunate countess. She is thought to have been born in or around 1617, and thus would have been about sixty-eight when she met her fate.

In July 1685, shortly after the Battle of Monmouth, Lady Alice agreed to shelter the nonconformist minister John Hickes at her residence near Ringwood, in Hampshire. He was accompanied by Richard Nelthorpe, a lawyer and conspirator in the Rye House Plot under the sentence of outlawry. Like Alice, Nelthorpe was executed.

In August 1685, the Bloody Assizes commenced at Winchester in the aftermath of the Battle of Sedgemoor. Five judges were appointed and were led by 'the hanging judge', Lord Chief Justice George Jeffreys, who gained notoriety for his harsh sentences. The court progressed from Hampshire to Dorset and Somerset, and hundreds of executions took place.

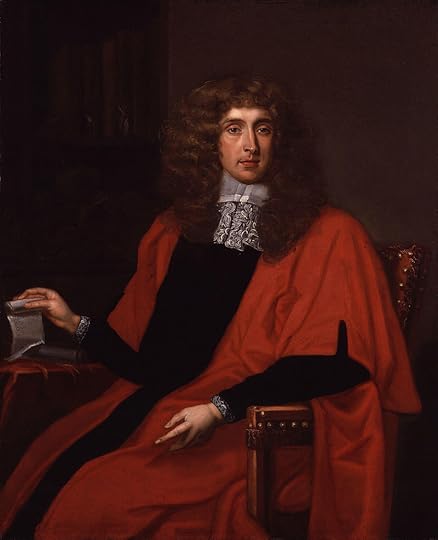

Above: George Jeffreys, 'the hanging judge'.

Above: George Jeffreys, 'the hanging judge'.Lady Alice pleaded that she had no knowledge of the seriousness of Hickes' offence, and confirmed that she had known nothing of Nelthorpe. It has been suggested that the harshness of the prosecution case derived in part from Alice's status as the widow of John Lisle, one of the regicides of Charles I. Perhaps, then, Alice's demise could be read as a process of revenge for the events of the mid seventeenth-century. She was convicted and sentenced to be burned at the stake, although the sentence was later commuted to beheading.

On 2 September 1685, Lady Alice walked out of the Eclipse Inn, where she had spent her final hours, and was executed in the market place, and was recorded as having met her fate with dignity and courage. She was buried at Ellingham, Hampshire. For harbouring fugitives, Lady Alice was convicted and executed as a traitor, but she has been viewed as a victim of judicial murder; the contemporary historian and philosopher Gilbert Burnet referred to her as a martyr.

Published on March 16, 2017 03:39

March 8, 2017

International Women's Day 2017

Today is International Women's Day. My research to date has primarily focused on late medieval and early modern women, specifically queenship. Earlier this year, MadeGlobal published my book Queenship in England 1308-1485, the culmination of years of research and what I would like to refer to as historical discovery. In honour of International Women's Day, therefore, I would like to think about some of the women that inspired my research.

My first introduction to the indomitable Isabella of France, wife of Edward II, was not an especially positive one, for it was based on a book that was both inaccurate and misleading. By immersing myself in the extant primary sources and by reading a fascinating array of secondary material, I gained a fuller and more nuanced picture of this intriguing queen. In Queenship in England, I focused on the multivalent roles that comprised the office of queenship. Isabella was highly active in her household governance, her lordship, her intercessionary activities and her patronage. Her relationship with Edward, moreover, appears to have been close and loving for the first fifteen years of their marriage. But political tensions and the ascendancy of the Despensers fractured their relationship beyond repair.

Margaret of Anjou and Elizabeth Wydeville, like Isabella, have been similarly maligned or misrepresented, but the last few decades have witnessed several publications that have aimed to rehabilitate their reputations. My research indicated that Margaret was more politically astute and pragmatic than is usually suggested, and she sought to maintain a cordial relationship with the duke of York from early on in her queenship. In the aftermath of the Wars of the Roses, it was convenient for commentators to assign blame to Margaret for the conflict, but in assuming the role of leader, she was ardently fighting to protect the inheritance of her son and the honour of her beleaguered husband.

Elizabeth's personality and appearance have both been attacked by modern historians, who have condemned her as a cold, grasping and avaricious woman. Much of this results from a misunderstanding of court protocol. In her lifetime, Elizabeth was praised for her "womanly" conduct and, indeed, she appears to have actively distanced herself from the militant queenship of her predecessor. She was, in most respects, the ideal medieval consort, and demonstrated her suitability to be queen by bearing Edward IV several children, thus testifying to divine approval of their union. The events following Edward's death and the accession of Richard III, coupled with her questionable relationship with Henry VII, have perhaps obscured the fact that Elizabeth was one of the most successful medieval queens of England.

These three women are perhaps three of the most well-known of England's medieval queens, and they are certainly not the only ones who fascinated and inspired me during my research and writing. However, I was especially drawn to their experiences and stories, in demonstrating the rich opportunities for the consort to wield agency and, in some instances, power. Investigating the relationship between gender and power as it operated in the political sphere is an exciting exercise and one that continues to resonate, and be relevant to, today.

Published on March 08, 2017 00:49

February 8, 2017

8 February 1587: The Execution of Mary I of Scotland

Before the sixteenth-century, executing a queen would have been virtually unthinkable in pre-modern Europe. By 1587, however, executing queens in England was not a strange concept. On 8 February that year, Mary I of Scotland - or Mary, Queen of Scots as she is more commonly known - was executed at Fotheringhay Castle. She was the fourth queen to be executed in England since 1536, following Anne Boleyn, Katherine Howard and Jane Grey, but unlike her headless predecessors, Mary was a Scottish queen regnant.

Mary's life following her abdication from the Scottish throne in 1567 had been difficult. Although she has frequently been disparaged as a foolish, inept queen who placed too much emphasis on matters of the heart, more recently Mary has been reappraised as a conscientious and efficient monarch who was, nonetheless, undermined by contemporary expectations of gender. In a kingdom that was, at best, ambivalent to female rule, Mary was compelled to navigate not only the political and factional rivalries that held sway at the Scottish court, but also the religious tensions unleashed by the Reformation. It was to her credit that, as a Catholic monarch, Mary attempted to reach some form of compromise with her unwavering Protestant subjects.

Mary had also previously been queen consort of France as the wife of Francois II, but her young husband's death meant that Mary was compelled to return to her native kingdom to commence the business of ruling. Like her cousin Elizabeth I, the Scottish queen was expected to marry and produce an heir to ensure the continuation of the Stewart dynasty. Eventually, in 1565, she married Henry, Lord Darnley, the eldest son of Lady Margaret Douglas and a grandson of Margaret Tudor. The marriage caused a degree of controversy and was not received well by Elizabeth I, but the collapse of the marriage and Darnley's murder in 1567 fatally undermined Mary's position. Whether or not she was involved in her husband's death - and most historians generally believe she was not - Mary made a gross misjudgement by marrying the chief suspect, the earl of Bothwell, shortly afterwards. Her decision was most likely due to Bothwell's rape of her, which meant that marriage to him was the only means of protecting her honour. While this decision can, from a modern perspective, be sympathised with, it was condemned by her furious subjects, and Mary's enforced abdication followed shortly afterwards. She was succeeded by her young son James, her child by Darnley.

Above: Mary Queen of Scots was executed at Fotheringhay Castle.

Above: Mary Queen of Scots was executed at Fotheringhay Castle.

During her marriage to Francois II, Mary had publicly stated her belief that she was the rightful queen of England, by quartering the royal arms of England with those of France and Scotland. This declaration was probably viewed with apprehension by Elizabeth I, who was generally regarded in Catholic Europe as a bastard and usurper. From a Catholic perspective, Mary Queen of Scots was the rightful queen of England, both because of her religion and because she was undoubtedly legitimate. After the abdication in 1567, Mary journeyed across the border into England in a bid to secure protection from her cousin and fellow queen, and perhaps hoped that Elizabeth would assist in her restoration to the Scottish throne. This decision, with the benefit of hindsight, was probably the worst that Mary ever made. Elizabeth made no attempt to restore her cousin to the Scottish throne and effectively had her placed under house arrest.

Mary's situation became more difficult over the years, as Catholicism became more closely associated with political insurrection and foreign intrigue, especially in the context of deteriorating Anglo-Spanish relations and escalating religious tensions, resulting in bloodshed, in France. The papal bull of 1570, which effectively released Elizabeth's subjects from their bonds of allegiance to her and actively encouraged them to kill her, could be viewed as something of a turning point in the queen's attitude to her Catholic subjects. During the 1570s and 1580s, a series of increasingly harsh laws were promulgated with the intent of enforcing conformity and ensuring obedience to the Protestant queen. Harbouring priests was made a capital offence, and priests who entered the realm with the intent of ensuring conversion could be executed, and many were. Perhaps acting out of desperation, Mary became involved in a series of conspiracies aimed at deposing Elizabeth and replacing her with the Scottish queen. Mary always believed that she was the rightful queen of Scotland, anointed by God, and only death could prevent her from enjoying that honour. By this point, however, she also coveted the English crown. So seriously were these conspiracies taken by the English government that in 1584 a document known as the Bond of Association was issued. It obliged all those who signed it to execute any person who attempted to usurp the English throne or assassinated Elizabeth. It was clearly aimed at Mary.

In 1586, Mary was judged to have actively colluded in the Babington Plot, for her correspondence was said to indicate her consent to Elizabeth's assassination - an act that would lead to her succession to the English throne. In October, the Scottish queen was tried at Fotheringhay Castle, and defended herself with dignity and courage; she also questioned the right of the court to try her, a divinely anointed queen regnant. However, the verdict was never in doubt. On 25 October, Mary was found guilty. Elizabeth hesitated to proceed with her cousin's execution, perhaps because she feared the response of Catholic Europe. Mary's son, King James, diplomatically sought Elizabeth's mercy for his mother, but in reality he took very little action to assist Mary.

Above: The tomb of Mary, Queen of Scots at Westminster Abbey. Copyright Westminster Abbey.

Above: The tomb of Mary, Queen of Scots at Westminster Abbey. Copyright Westminster Abbey.

On the day of the execution, Mary proclaimed that she was dying for her Catholic religion, as a true woman of Scotland and France, the two kingdoms that she had governed. It took three blows of the axe to sever her head, but she was subsequently revered on the continent as a Catholic martyr, murdered by the ruthless and immoral Elizabeth. Although she was initially interred at Peterborough Abbey, when her son became king of England he had her reburied at Westminster Abbey. The iconography of her tomb, as Anne McLaren has stressed, celebrated her as the rightful heiress of Henry VII and, therefore, as the rightful queen of England. Her fertility and fecundity, as the mother of James I of England, was contrasted with the barrenness of her cousins, Mary I and Elizabeth I, who lay nearby. It is ironic that, shortly before her death in 1603, Elizabeth elected the son of her enemy to succeed her. In doing so, the English queen ignored the wishes of her father, Henry VIII, that the Suffolk line should succeed his children, if they all died childless, rather than the Scottish line, which he had barred completely.

Published on February 08, 2017 06:29

January 27, 2017

Holocaust Memorial Day

Above: York Minster's Star of David - image credit, York Minster.

The Holocaust, the genocide masterminded by the Nazis, took place between 1941 and 1945, at the same time as the Second World War was being fought. More than fifty years later, the horrors of this period continue to shock and continue to reverberate. Around six million Jews were murdered, while other victims numbered in the millions and thousands, including Soviet prisoners of war, the disabled, Jehovah's witnesses, homosexuals, Romani and ethnic Poles. These victims endured enslavement in concentration camps, imprisonment, torture and murder, and the testimonies of those who survived these horrors testifies to the dark depths of human hatred, intolerance and bigotry.

Holocaust Memorial Day Trust's theme for 2017 is how can life go on? The survivor and prolific author Elie Wiesel, who died last year, explained that "for the survivor death is not the problem. Death was an everyday occurrence. We learned to live with Death. The problem is to adjust to life, to living. You must teach us about living." This year's theme incorporates issues including trauma and coming to terms with the past, displacement and seeking refuge, justice, rebuilding communities, and reconciliation and forgiveness. These issues continue to resonate today, and should be considered by each and every one of us.

Yesterday, I attended a memorial service at York Minster, and a beautiful Star of David was lit in the Chapter House using candles. The service was moving, and included a talk from a young man whose relative had perished in the Holocaust. Attending services such as that at York Minster always brings back memories for me of visiting Auschwitz in 2009 while at secondary school. While our teacher prepared us as much as she could for what we would experience, visiting the camp was something that I don't think any of us could forget. Emotions ran high that day, and subsequently, but how was it possible for any of us to imagine the suffering inflicted on those who walked through Auschwitz's gates, many of whom never left? How could any of us truly come to terms with the horrors inflicted at Auschwitz, and other killing camps such as Treblinka or Sobibor?

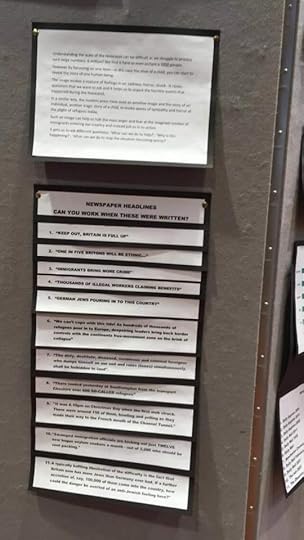

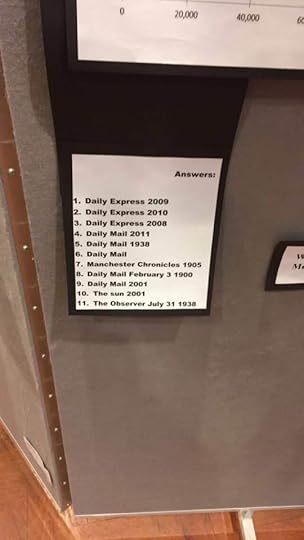

I have included some photos taken from the trip. These serve as powerful reminders of how cruelty, intolerance and hatred can extend to unspeakable crimes and to loss of life. They remind us that racism, xenophobia, anti-Semitism, ethnic cleansing, homophobia and prejudice are still with us today. These issues will always be important. They are inextricably tied to human nature, and remind us of what can happen when scapegoats are sought for perceived unfairness or problems in society.

Recently, I attended an exhibition about one of the most famous victims of the Holocaust, Anne Frank, a diarist who died at Bergen-Belsen concentration camp at the age of fifteen. The exhibition's title was 'A history for today'. It was incredibly moving to revisit Anne's story and to consider her legacy, but two photos, in particular, caught my eye and provided a startling reminder that, perhaps, we have not really moved forward since the dark days of 1941-45. Genocides in Cambodia, Rwanda, Bosnia, and Darfur - among others - are a testament to the unwillingness, or inability, of subsequent generations to learn from the horrors of the past. These two photos, I think, speak a thousand words.

Hatred, intolerance, bigotry and prejudice are still very much with us, and there are still lessons to be learned from the Holocaust.

Published on January 27, 2017 04:56

January 4, 2017

Queenship in England

Happy New Year! I am delighted to inform you that my new book, Queenship in England, will be published on 12 January 2017 by MadeGlobal. The book is currently available on Amazon to preorder on Kindle, and will be available soon in paperback. You can preorder it on Kindle here.

Queenship in England is a study of the institution of queenship between 1308 and 1485, and examines the experiences of the nine women who occupied the position of queen during that period: Isabella of France; Philippa of Hainault; Anne of Bohemia; Isabelle of France; Joan of Navarre; Katherine of Valois; Margaret of Anjou; Elizabeth Wydeville; and Anne Neville. The book has been praised by Amy Licence, author of Catherine of Aragon: An Intimate Life of Henry VIII's True Wife, as offering 'an interesting and accessible exploration of medieval queenship in relation to gender expectations', while Toni Mount, author of A Year in the Life of Medieval England, described it as 'very readable' and 'thoroughly researched'.

It was absolutely fascinating to research and write this book, and I hope you will enjoy reading it.

Published on January 04, 2017 11:05

December 14, 2016

The Tudors and TV: Is There Anything New to Say?

[image error]

Tudor enthusiasts greeted the news of Lucy Worsley's new BBC documentary about the six wives of Henry VIII with excitement. For those of us fascinated by the Tudor period, we cannot get enough of it; we read about it, we watch documentaries about it, we visit the buildings associated with it and, perhaps most of all, we love to talk about it. Admittedly, Henry's tumultuous marriages is a well-worn subject, but the enthusiastic Worsley promised to offer new insights and, for me at least, she has done so in what is, admittedly, a challenging medium: television.

However, not everyone reacted as positively to Worsley's documentary as others. Last week, an article was published in The Guardian entitled: 'Six Wives With Lucy Worsley: Why TV History Shows are for the Chop', and was written by Joel Golby. In it, he attacked Worsley's documentary as 'awful, tedious history' and 'Game of Thrones without any of the good bits', a rather absurd criticism that, nonetheless, exposes the difficulty that historians face in attempting to strike a balance between education and entertainment, when presenting TV documentaries. In one hour, Worsley was required to discuss and examine Henry's 24-year long marriage to Katherine of Aragon, her experiences of queenship and Anne Boleyn's rise to power, in a way that was both credible and engaging to viewers. Golby's scathing assessment indicates that she failed.

Others voiced their criticism of another Tudor documentary on Twitter and in the comments section of the article, although some commentators were rather more positive. One praised Worsley's coverage of 'one of the most fascinating eras.' But Golby's negativity was mirrored in another article published in History Today on 14 December by the magazine's editor, Paul Lay. The title of the piece is 'Television History and Its Discontents', and featured a still from Worsley's documentary, in which she wears Tudor costume.

Lay criticised Six Wives, for he suggested that it offered 'unconvincing, cheap looking, historical reconstructions', and because it 'says nothing that we do not know already.' I object wholeheartedly to Lay's criticism, which I believe to be both unfair and untrue. The documentary does offer new insights, and as a biographer of Katherine Howard, I wholeheartedly commend Worsley's decision to present Henry VIII's hapless fifth wife as a victim of predatory behaviour, a view that has only gained acceptance amongst historians in the last decade or so.

Before then, Katherine Howard tended to be perceived as, in Alison Weir's words, 'an empty-headed wanton', or even, to use the late David Loades's term, 'a stupid slut'. She has been derided for her 'promiscuity' and has been slated as a 'natural born tart' (Alison Plowden). Television documentaries and dramas tended to follow these interpretations: Tamzin Merchant presented Katherine as a nymphomaniac, even a prostitute, in the Showtime television series The Tudors, and even in Dr David Starkey's entertaining documentary about the six wives, Katherine was said to have shown more dignity at her death than she had ever displayed in life. An earlier documentary about the six wives produced this year also focused on Katherine as sexually adventurous both before and after her marriage.

To my knowledge, Worsley is the first to present Katherine as an abused victim in a television documentary. In doing so, she has drawn on the theories of historians such as Retha Warnicke and Joanna Denny to offer a compelling, and more historically accurate, version of Katherine's life than previously seen ever before on television. From this perspective, Lay's criticism is absurd.

It is true that there is an abundance of documentaries about Henry VIII and his wives, but is that really a bad thing? Many people are fascinated by the king and his queens, and read as many books as they can about them, as well as flocking to Hampton Court Palace, the Tower of London and Windsor Castle every year, as well as to the numerous National Trust and English Heritage owned properties. I object to criticisms of new documentaries about the Tudors and, in particular, Henry VIII - for contrary to these views, such documentaries are offering new insights and are aimed at audiences who will appreciate these insights, because they are intelligent and engaged viewers who want to learn as much as they can about the period.

Perhaps, if the likes of Golby and Lay view such documentaries as redundant, because they offer 'nothing that we do not know already', then they should not watch them, since there are many who will watch them and will learn something new. If either individual can point me towards an older documentary that portrays Katherine Howard as a victim of sexual predators, then I might rethink my views. But until they can, I stand by why I argue in this piece: that even well-trodden subjects can offer something new, which can be documented on television in a manner that is both educational and entertaining.

Tudor enthusiasts greeted the news of Lucy Worsley's new BBC documentary about the six wives of Henry VIII with excitement. For those of us fascinated by the Tudor period, we cannot get enough of it; we read about it, we watch documentaries about it, we visit the buildings associated with it and, perhaps most of all, we love to talk about it. Admittedly, Henry's tumultuous marriages is a well-worn subject, but the enthusiastic Worsley promised to offer new insights and, for me at least, she has done so in what is, admittedly, a challenging medium: television.

However, not everyone reacted as positively to Worsley's documentary as others. Last week, an article was published in The Guardian entitled: 'Six Wives With Lucy Worsley: Why TV History Shows are for the Chop', and was written by Joel Golby. In it, he attacked Worsley's documentary as 'awful, tedious history' and 'Game of Thrones without any of the good bits', a rather absurd criticism that, nonetheless, exposes the difficulty that historians face in attempting to strike a balance between education and entertainment, when presenting TV documentaries. In one hour, Worsley was required to discuss and examine Henry's 24-year long marriage to Katherine of Aragon, her experiences of queenship and Anne Boleyn's rise to power, in a way that was both credible and engaging to viewers. Golby's scathing assessment indicates that she failed.

Others voiced their criticism of another Tudor documentary on Twitter and in the comments section of the article, although some commentators were rather more positive. One praised Worsley's coverage of 'one of the most fascinating eras.' But Golby's negativity was mirrored in another article published in History Today on 14 December by the magazine's editor, Paul Lay. The title of the piece is 'Television History and Its Discontents', and featured a still from Worsley's documentary, in which she wears Tudor costume.

Lay criticised Six Wives, for he suggested that it offered 'unconvincing, cheap looking, historical reconstructions', and because it 'says nothing that we do not know already.' I object wholeheartedly to Lay's criticism, which I believe to be both unfair and untrue. The documentary does offer new insights, and as a biographer of Katherine Howard, I wholeheartedly commend Worsley's decision to present Henry VIII's hapless fifth wife as a victim of predatory behaviour, a view that has only gained acceptance amongst historians in the last decade or so.

Before then, Katherine Howard tended to be perceived as, in Alison Weir's words, 'an empty-headed wanton', or even, to use the late David Loades's term, 'a stupid slut'. She has been derided for her 'promiscuity' and has been slated as a 'natural born tart' (Alison Plowden). Television documentaries and dramas tended to follow these interpretations: Tamzin Merchant presented Katherine as a nymphomaniac, even a prostitute, in the Showtime television series The Tudors, and even in Dr David Starkey's entertaining documentary about the six wives, Katherine was said to have shown more dignity at her death than she had ever displayed in life. An earlier documentary about the six wives produced this year also focused on Katherine as sexually adventurous both before and after her marriage.

To my knowledge, Worsley is the first to present Katherine as an abused victim in a television documentary. In doing so, she has drawn on the theories of historians such as Retha Warnicke and Joanna Denny to offer a compelling, and more historically accurate, version of Katherine's life than previously seen ever before on television. From this perspective, Lay's criticism is absurd.

It is true that there is an abundance of documentaries about Henry VIII and his wives, but is that really a bad thing? Many people are fascinated by the king and his queens, and read as many books as they can about them, as well as flocking to Hampton Court Palace, the Tower of London and Windsor Castle every year, as well as to the numerous National Trust and English Heritage owned properties. I object to criticisms of new documentaries about the Tudors and, in particular, Henry VIII - for contrary to these views, such documentaries are offering new insights and are aimed at audiences who will appreciate these insights, because they are intelligent and engaged viewers who want to learn as much as they can about the period.

Perhaps, if the likes of Golby and Lay view such documentaries as redundant, because they offer 'nothing that we do not know already', then they should not watch them, since there are many who will watch them and will learn something new. If either individual can point me towards an older documentary that portrays Katherine Howard as a victim of sexual predators, then I might rethink my views. But until they can, I stand by why I argue in this piece: that even well-trodden subjects can offer something new, which can be documented on television in a manner that is both educational and entertaining.

Published on December 14, 2016 15:12

December 8, 2016

8 December 1542: The Birth of Mary, Queen of Scots

On 8 December 1542, a princess was born to Scotland. At Linlithgow Palace, Queen Marie de Guise, consort to James V of Scotland, delivered a daughter, who was named Mary; she would be their only surviving child. Six days later, Mary became queen of Scotland, following her father's death on 14 December. It was rumoured that James had lamented that his dynasty 'came with a lass, it will pass with a lass.' It is, however, questionable whether this legend has any truth to it. Mary was the first queen regnant of Scotland since Margaret of Norway (1283-90), who died at the age of seven.

Mary's early years at the Scottish court were tumultuous ones, for her kingdom was at war with England. Henry VIII was determined to secure the submission of Scotland, and engaged in what became known as 'the Rough Wooing', in which he sought to effect the marriage of Mary to his son and heir, Edward. The two kingdoms had signed the Treaty of Greenwich in 1543, which agreed to a marriage between Edward and Mary, but the Scots soon renounced it. Mary's mother, the dowager queen, favoured an alliance with France, rather than England, and it was to France that she looked with regards to her daughter's future.

Above: Linlithgow Palace, where Mary was born in 1542.

Above: Linlithgow Palace, where Mary was born in 1542.In 1548, at the age of five, the Queen of Scots departed for France in the company of her four companions - all named Mary - and a sizeable retinue. She was betrothed to Francois, dauphin of France, and could thus anticipate a glorious future as queen consort of France, as well as queen regnant of Scotland. Mary was provided with an excellent education, in which she acquired expertise in dancing and music making, singing, needlework and horsemanship. She later became known as an accomplished poet. However, her language skills were somewhat rudimentary; certainly, she did not possess the linguistic talents of her cousin and rival, Elizabeth. As she grew to maturity, Mary was reported to be beautiful and charming. She was tall in stature, with auburn hair and dark eyes. Her love of France, and her French behaviour and customs, did not necessarily endear her to her Scottish subjects. Lord Ruthven, who was involved in the murder of her servant Rizzio, allegedly feared her wiles that she had developed while spending 'her youth in the Court of France.'

Mary was trained to regard herself as not only the queen of Scotland and France, but also the rightful queen of England and Ireland, in the event of her cousin Mary I's death. Henry VIII's will stipulated that, should Mary Tudor die without heirs, the crown should pass to her younger sister Elizabeth. However, Catholic rulers such as Henri II of France did not regard Elizabeth as the rightful heir to the English throne, on account of both her religion (Protestantism) and her bastardy (her parents' marriage had been annulled in 1536). From their point of view, it was Mary, Queen of Scots who had the right to succeed Mary Tudor. Naturally, as his son Francois was betrothed to the Queen of Scots, Henri was determined that she should be queen of England.

Mary's first two husbands: Francois II of France (left) and Henry, Lord Darnley (right).

Mary's first two husbands: Francois II of France (left) and Henry, Lord Darnley (right).

It is this context that explains why 1558 was a crucial year for Mary, Queen of Scots. On 24 April, at the age of fifteen, she married the dauphin in a splendid ceremony at Notre Dame. Seven months later, Mary I of England died. The crown passed to her sister Elizabeth, but France did not recognise the new queen, at a time of war between the two kingdoms. Instead, Mary Queen of Scots and her husband quartered the royal arms of England with those of France and Scotland, in effect proclaiming themselves the rightful king and queen of England. It was a daring move, and it did not endear the Scottish queen to her cousin Elizabeth.

Henri II's death the following year meant that Francois succeeded him as king; the sixteen-year-old Mary was now queen consort of France. However her husband, who seems to have been sickly from an early age, died the following year, and it was intimated to Mary that there was no place left for her in France. In August 1561, she returned to Scotland, determined to rule as queen regnant. Occasionally, Mary has been disparaged as a frivolous ruler uninterested in affairs of government or politics, but she appears to have frequently attended council meetings and, moreover, was eager to maintain religious stability. The tensions between Catholics and Huguenots in France were steadily increasing, and culminated in the massacre of St. Bartholomew's Day in 1572. Mary I of England, moreover, had persecuted her Protestant subjects - almost 300 were burned at the stake - while Elizabeth I was responsible for the execution of almost 200 Catholic subjects. Mary Queen of Scots, who had perhaps gained an awareness of the religious violence that threatened to undo France during her years spent there, was determined to secure a religious rapprochement in Scotland.

The Scottish Reformation had been highly effective, and Mary returned to a country that was embracing Protestantism. However, she managed to hear mass privately in her chapel at Holyrood, although she was criticised by the militant preacher John Knox for doing so. Alongside her religious compromises, Mary sought to secure the recognition of Elizabeth as her heir, should the English queen die without an heir. Elizabeth, who had been the focus of rebellion during her sister's reign, had learned of the dangers in selecting an heir during her lifetime, particularly when that heir was Catholic and the ruler of a neighbouring kingdom. She was also aware that many Catholics, especially on the Continent, refused to regard her as the rightful queen. In view of this, Elizabeth made overtures to Mary but never granted her the recognition that Mary craved.

Above: Mary's cousin and rival, Elizabeth I of England. (left)Mary's son and successor, James VI of Scotland. (right)

Above: Mary's cousin and rival, Elizabeth I of England. (left)Mary's son and successor, James VI of Scotland. (right)

As a queen regnant of Scotland, Mary was eager to marry again. A variety of candidates were proposed, including Don Carlos of Spain, son of Philip II. Elizabeth, for reasons that continue to perplex modern historians, offered Mary the hand of Robert Dudley, earl of Leicester. The earl was rumoured to be the English queen's lover, and he was clearly greatly inferior to the Scottish queen in status. Moreover, he came from a family of traitors. Mary, offended, declined Elizabeth's offer. The English queen had stipulated that Mary could retain her friendship only by marrying Leicester or an English subject, or by remaining unmarried, and hinted that she might recognise Mary as her heir if she conformed to these conditions. In view of this, Mary's decision to wed Henry, Lord Darnley is explicable. Henry was the eldest son of Matthew Stuart, earl of Lennox, and Lady Margaret Douglas. He was, therefore, a grandson of Margaret Tudor and a great-grandson of Henry VII. He, like Mary, had a claim to the English throne, and it was perhaps in a bid to strengthen her own claim that Mary elected to marry her relative. They married at 29 July 1565 at Holyrood.

Henry was at least three - possibly four - years younger than his wife, and events would reveal that he was immature, spoiled, vindictive and arrogant. The marriage was not popular. The English refused to recognise the marriage and declined to refer to Henry as the king of Scotland, a title he was most anxious to enjoy. Elizabeth was enraged by her cousin's activities, and it was reported that there was much 'jealousies, suspicions and hatred' between the two queens, where previously there had been 'sisterly familiarity'. By marrying Henry, a Catholic with a claim to the English throne, Mary had undermined the fragile amity between England and Scotland.

Mary's remarriage placed her in a difficult position that was exacerbated by rebellion at home - known as the Chaseabout Raid - and by increasing tensions between her Catholic and Protestant councillors. Her new husband, moreover, was furious by what he perceived as his wife's refusal to grant him the crown matrimonial of Scotland, which effectively meant that his status as king of Scotland was a rather meaningless one. The reign of Mary I of England had evidenced the ambiguities and difficulties of authority and precedence when a queen regnant married. Moreover, Mary's friendship with her adviser David Rizzio, a Savoyard musician, enraged both her husband and the Scottish nobles more broadly. On 9 March 1566, Rizzio was brutally stabbed to death by several noblemen in the queen's own chambers; Mary herself was seized by her husband and was harrassed by Lord Ruthven. Mary was probably shattered by the experience, but her pregnancy meant that she had to focus on her health. On 19 June, she gave birth to a son, James, who would later succeed her as James VI.

Mary's growing problems with Henry perhaps led her to collude in plots against him, although it is unlikely that she actively intrigued for his death. On 10 February 1567, her husband was murdered at Kirk o'Field, near Edinburgh. The murder scandalised Mary's subjects and was reported across Europe; Elizabeth I proclaimed herself shocked by what had happened, and quickly admonished Mary for her apparent closeness to the chief suspect, the earl of Bothwell. Mary has often been criticised for her behaviour, but she seems to have suffered a complete mental breakdown. Amid reports that she was depressed, perhaps suicidal, Mary was captured by Bothwell and incarcerated at Dunbar. Having abducted her, Bothwell then proceeded to rape her. In a bid to protect her own honour, as well as that of her infant son, Mary married Bothwell in May 1567. She argued frequently with her new husband and reportedly called for a knife with which to end her unhappy life. Her suicidal tendencies, coupled with her depression and anxiety that had been exacerbated by the abduction, are powerful evidence against the simplistic view that she, besotted by Bothwell, had engaged in a passionate love affair with him and then encouraged him to murder Henry. Eventually, Mary was seized by the confederate lords at Carberry Hill, abandoned by her husband, and was transported through Edinburgh as crowds shouted 'Burn the whore!' She was imprisoned at Loch Leven, and forced to abdicate in favour of her son, James.

Above: Mary's parents, James V of Scotland and Marie de Guise.

Above: Mary's parents, James V of Scotland and Marie de Guise.

At Mary's birth in December 1542, Marie de Guise could never have imagined the turbulence that would characterise her daughter's life, which arose as a result of dynastic conflict, political instability and religious tensions. Nor could she ever have imagined that Mary would be the only monarch in Scottish history to die on an English scaffold, nor could she have envisaged that Mary would be the fourth British queen in a century to suffer that humiliating death. Mary, Queen of Scots' reputation has rarely been positive or even nuanced; traditionally identified as a scheming adulteress, who colluded in her husband's murder, she has also been regarded as a virtuous martyr for the Catholic faith and the rightful queen of England, executed by her barbaric and unnatural cousin, the usurper Elizabeth. Perhaps what should most be appreciated is the difficulties Mary faced in attempting to govern a turbulent kingdom, at a time when queen regnants were viewed with suspicion or were actively disparaged. Elizabeth I proved that a woman could rule successfully and actively, but the difficult experiences of her sister Mary I and her cousin Mary, Queen of Scots provided telling evidence that such success was neither preordained nor necessarily even expected by one's subjects. More recently, historians have come to view the Scottish queen sympathetically, with a more nuanced understanding of the religious, political and dynastic conflict that severely undermined her kingdom and affected her attempts - genuine attempts - to rule successfully.

Published on December 08, 2016 02:48