Conor Byrne's Blog, page 4

July 20, 2016

The Expulsion of the Jews from England

On 18 July 1290, a cataclysmic event took place that was to have far-reaching consequences. King Edward I ordered the expulsion of the Jews from England. Only in 1657, a total of 367 years later, were the Jews permitted to return to England. The Edict of Expulsion has usually been interpreted as the inevitable culmination of worsening persecution against the Jews.

By 1290, the Jews were an accepted presence in English society, although Christians viewed them with ambivalence. Economically, Jews could enjoy great influence. Loans with interest were permitted between Jews and non-Jews, contrary to English practice which expressly forbade usury, which was regarded by the Church as a heinous sin. While Jews could benefit from lending money at high rates of interest, they were also vulnerable to the whims of the king, who could levy heavy taxes on them without summoning Parliament. Their reputation as extortionate moneylenders, whether deserved or not, could make them unpopular among their Christian fellows.

In wider society, as W.D. Rubinstein has noted, anti-Jewish attitudes were prevalent. These stemmed from, and were encouraged by, negative images of the Jew as a diabolical figure that preyed on innocent Christian children. Jews were vulnerable to accusations of ritual murders; most notably, William of Norwich (d. 1144) and Little St. Hugh of Lincoln (d. 1255). Walter Laqueur opined that: 'There have been about 150 recorded cases of blood libel... that resulted in the arrest and killing of Jews throughout history, most of them in the Middle Ages. In almost every case, Jews were murdered, sometimes by a mob, sometimes following torture and a trial'.

Above: William of Norwich (left) and Little St. Hugh of Lincoln (right).

Above: William of Norwich (left) and Little St. Hugh of Lincoln (right).

Hostility to the Jews occasionally erupted in violence and bloodshed. Massacres occurred in 1189 and 1190; in York, over 100 Jews were massacred while hiding in a tower. The situation gradually worsened as, less than thirty years later, in 1218, Jews were required to wear a marking badge. Over the course of the thirteenth-century, Jews were heavily taxed. In 1275, King Edward I issued a statute that placed a number of restrictions on the Jews in England, in which he outlawed the practice of usury. Later, the king charged the Jews with failing to follow the Statute of Jewry, and he ordered their expulsion from the country in July 1290.

Only in the seventeenth-century were Jews officially permitted to return to England. The widely anti-Semitic attitudes that characterised medieval and early modern Europe, as a whole, did not disappear in modern times. The Holocaust, which claimed the lives of roughly 6 million Jews, built on and was encouraged by anti-Jewish propaganda that had existed on the Continent for hundreds of years.

Published on July 20, 2016 12:34

July 19, 2016

19 July 1543: The Death of Mary Stafford

We do not know how old Mary Stafford (nee Boleyn) was when she died on 19 July 1543. Mystery surrounds every aspect of Mary's life: we do not know her date of birth, what she looked like, whether she was the oldest or the youngest of the surviving Boleyn children, what her relationship with her siblings was like, or even where she died. Mary's life has been imagined and invented in works of fiction, most notably Philippa Gregory's bestselling novel The Other Boleyn Girl and in Karen Harper's The Last Boleyn.

Although Mary remains best known as the sister of Anne Boleyn, it seems fitting to refer to her as Mary Stafford given that she died while the wife of William Stafford. In her letter to Thomas Cromwell, written c. 1534, Mary described her second husband as 'honest' and noted that she 'could never have had one that should have loved me so well'. At a distance of almost five hundred years, it is impossible to know whether Mary's controversial marriage to William Stafford was ultimately happy, but certainly theirs appears to have initially been a love match. Like other Tudor noblewomen, such as Frances Brandon, Katherine Willoughby and Anne Stanhope, Mary had selected a second husband who was inferior to her in status because it brought the promise of security, although it enraged her family and compelled her sister to order her dismissal from court.

At her death, Mary held a number of properties, many located in Essex. After the disgrace and deaths of her brother and sister in 1536, she was her father's sole heiress and it was to her that the Boleyn inheritance passed. When Mary died, the properties passed to her son Henry Carey, who was then aged seventeen. He was highly favoured by his cousin Elizabeth following her accession in 1558. Henry's sister Katherine was also a favourite of the queen.

Above: Anne Boleyn. In the realm of fiction, Mary and Anne have often been presented as jealous rivals.

Above: Anne Boleyn. In the realm of fiction, Mary and Anne have often been presented as jealous rivals.

The last years of Mary Stafford's life were not necessarily pleasant ones. Her unexpected marriage to William Stafford displeased her family and her sister, who was then queen, banished her from court permanently. Less than two years later, Anne and George Boleyn were both executed, alongside four other men, on scandalous charges of adultery, incest and treason. Less than two years after the shocking events of 1536, Mary's mother died, and a year after that, her father also passed away. In 1542, her sister-in-law Jane Parker was beheaded for treason alongside Mary's cousin, Katherine Howard. Although she was not necessarily close to any of these individuals, it would be surprising if the betrayal, bloodshed and devastation that was inflicted on the Boleyn family between the late 1530s and early 1540s did not have an impact on Mary, by then the only surviving child of Thomas and Elizabeth Boleyn.

Two biographies of Mary have been published to date and she regularly features in general histories of Henry VIII's reign. Moreover, she has been the subject of numerous novels. However, much of Mary's life remains unknown. Perhaps it is this mystery, this uncertainty, that makes her so entrancing to modern audiences today.

[image error]Above: Katherine (left) and Henry (right), Mary's children by her first husband William Carey. Both were greatly favoured by their cousin, Elizabeth I.

[image error]Above: Katherine (left) and Henry (right), Mary's children by her first husband William Carey. Both were greatly favoured by their cousin, Elizabeth I.

Published on July 19, 2016 12:35

June 17, 2016

Queenship and Witchcraft: Joan of Navarre

In 1437, a week ago today, Queen Joan of Navarre died in London at the age of about sixty-six. Joan is one of the lesser known medieval queens of England and her controversial reputation is founded on the accusations of witchcraft that were levied against her by her stepson, Henry V. This neglect of Joan is unfortunate, because in reality she was one of the most intelligent, politically astute and capable consorts. Recently, I undertook research into Joan's life and discovered that there was a great deal more to her story than the rumours of sorcery that blackened her name.

Born around 1370 in Pamplona, Navarre, Joan married her first husband while still a teenager, in 1386. Her husband was John IV, duke of Brittany. The marriage appears to have been successful and the couple had nine children together. As duchess of Brittany, Joan participated in the ceremonies of court and she is known to have interceded for individuals who displeased her mercurial husband, including Clisson, constable of France. In her activities, Joan conformed entirely to contemporary expectations of how a noblewoman should behave. She fulfilled the roles of mother, wife, intercessor and patron. Her interest in court ceremonial, moreover, indicates that she was both cultured and artistic.

Above left: John IV, duke of Brittany, Joan's first husband. Above right: Henry IV of England, Joan's second husband.

Above left: John IV, duke of Brittany, Joan's first husband. Above right: Henry IV of England, Joan's second husband.

In 1399, when Joan was around the age of twenty-nine, her husband died. She chose not to remarry immediately after her husband's death and instead fulfilled the role of regent for her son, John V, during his minority. It was during this period that Joan clearly emerges as a politically astute, capable and wise ruler. In 1403, she remarried. Her second husband was Henry IV of England. By marrying Henry, Joan placed herself in an ambiguous position, for her husband was a usurper. As with the later consorts Elizabeth Wydeville and Anne Neville, whose husbands also unlawfully usurped the throne, Joan was required to legitimise her husband's claim to the throne. Rumours circulated that there had been long-standing affection between Henry and Joan, and it is possible that their marriage was a love match.

However, Henry also demonstrated shrewdness in selecting Joan to be his consort. She was highly experienced in the affairs of government, intelligent and pragmatic. Moreover, in bearing her first husband nine children, she was clearly fertile, which was undoubtedly important for a medieval king whose claim to the throne was not fully secure. Unfortunately, during their ten-year marriage Joan did not bear Henry an heir, although it is possible that she experienced stillbirths. Fortunately, the queen enjoyed excellent relations with her stepchildren, including her husband's son Henry.

Above: Henry V, Joan's stepson.

Above: Henry V, Joan's stepson.Henry IV's death, however, changed Joan's life. Financially straitened, the new king, Henry V, accused Joan of witchcraft in a ruthless attempt to seize her lands and income with which to finance his foreign wars. As a highborn woman, Joan was vulnerable to accusations that were usually gender specific: namely witchcraft, sorcery and adultery. Other medieval noblewomen suffered from similarly ignominious accusations: both Eleanor Cobham, duchess of Gloucester, and Jacquetta, duchess of Bedford, were accused of witchcraft. There is no surviving evidence that Joan ever engaged in activities associated with witchcraft, and it is surely significant that she was later restored to favour.

During her imprisonment, Joan resided at Pevensey Castle and later at Nottingham Castle. Her stepson died in 1422 and was succeeded by his only son, Henry VI. Joan died on 10 June 1437, the same year in which her successor, Katherine of Valois, also died. As with many medieval queens, there is a lack of evidence concerning Joan's life and her experiences as queen. However, she seems to have enjoyed success during her husband's reign, but his death placed her in an ambiguous position, for she had borne him no children and thus was unable to exert influence in the politics of her stepson's reign. With no-one to support her interests, she was vulnerable to the whims of Henry V and was humiliated when he seized her income to finance his wars on the Continent. Although she died in obscurity, Joan of Navarre emerges as a politically astute, intelligent and influential consort, whose eventual fate bears witness to the dangers faced by highborn women in the Middle Ages.

Published on June 17, 2016 06:02

May 31, 2016

31 May 1443: The Birth of Lady Margaret Beaufort

On 31 May 1443, Lady Margaret Beaufort was born at Bletsoe Castle in Bedfordshire. She was the daughter of John Beaufort, duke of Somerset, and Lady Margaret Beauchamp. Through her father, Margaret was a descendant of Edward III. Less than a year after his daughter's birth, the duke of Somerset died in suspicious circumstances while on campaign abroad. Some of his contemporaries believed that he had committed suicide, a heinous sin in the eyes of fifteenth-century individuals. Margaret probably did not learn of her father's death until she was older, but the knowledge that he may have killed himself would have brought shame and dishonour both to herself and to her family.

Shortly afterwards, Margaret's wardship was granted to the king's favourite, William de la Pole, first duke of Suffolk. As the heiress to her father's fortunes, Margaret was a highly valuable commodity. In early 1444, when she was less than three years old, Margaret was married to the duke's son John de la Pole. Occasionally, highborn children were married while still in infancy. Later, Edward IV's son Richard married Anne Mowbray when he was four years old and she five. Other evidence indicates that Margaret may actually only have married John in 1450, the year in which Suffolk was murdered. Irrespective of its date, the marriage was annulled in 1453 and Henry VI granted Margaret's wardship to his half-brothers Edmund and Jasper Tudor.

Above: Edmund Tudor, earl of Richmond.

Above: Edmund Tudor, earl of Richmond.

On 1 November 1455, when she was twelve years old, Margaret was married to the king's twenty-four year-old half-brother Edmund Tudor, earl of Richmond. Usually when girls were married at a young age, consummation of the marriage was delayed until a later date. Edmund, however, elected to consummate his marriage immediately. At the age of thirteen, Margaret fell pregnant. Her husband, however, was not to learn the outcome of her pregnancy, for he died while in captivity at Carmarthen in November 1456, perhaps of plague. Two months later, his widow gave birth to her only child, Henry Tudor, at Pembroke Castle. Evidence suggests that the birth was a difficult one, and Margaret may have been physically and mentally scarred by the experience. A year after the birth of her son, the widowed countess remarried. Her husband was Sir Henry Stafford, son of the duke of Buckingham. Evidence suggests that their marriage was a happy one.

Above: Pembroke Castle. Margaret gave birth to her son Henry there.

Above: Pembroke Castle. Margaret gave birth to her son Henry there.

In 1461, the castle was captured by the Yorkists, and the infant Henry was placed in the custody of William Herbert, earl of Pembroke. Henry later departed for the Continent in the company of his uncle Jasper. The year her son departed for France, Margaret's husband died at the Battle of Barnet. 1471 was a tumultuous year. The Lancastrian king Henry VI was probably murdered in the Tower of London by the victorious Yorkists, and his only son Edward of Westminster was slain at Tewkesbury. Margaret, whose status had naturally inclined her to support the Lancastrian cause, dutifully made a show of supporting the new Yorkist dynasty. She understood that her son, Henry Tudor, was the only Lancastrian claimant still alive. Edward IV, understandably, was determined to gain custody of Henry. In a bid to protect both herself and her son's future, Margaret outwardly supported the house of York.

A year after her husband's death, Margaret married for the last time, to Thomas Stanley. This marriage enabled Margaret to reside at court, and she appears to have enjoyed amicable relations with both the king and queen, later serving as godmother to one of their daughters. However, Edward IV's unexpected death in 1483 and the usurpation of Richard III changed Margaret's life forever. Margaret initially signalled her support of the new regime by carrying Anne Neville's train at her coronation, but she wholeheartedly supported the duke of Buckingham's rebellion against Richard III, perhaps with the backing of Edward IV's widow Elizabeth Wydeville. The rebellion was legitimated by rumours that Edward IV's sons had been murdered, perhaps on the orders of Richard III. It was agreed that, if the rebellion succeeded, Henry Tudor would marry Edward IV's daughter Elizabeth of York. However, the rebellion failed and Buckingham was executed. Margaret was stripped of her titles and estates and placed under house arrest; she was fortunate to escape with her life.

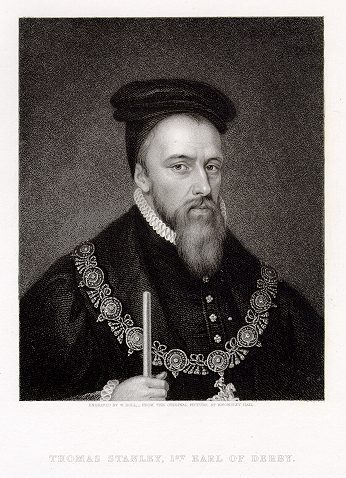

Above: Thomas Stanley, husband of Margaret Beaufort.

Above: Thomas Stanley, husband of Margaret Beaufort.

Despite this setback, Margaret continued to scheme for her son's accession. Evidence suggests that she had been content to support Edward IV and desired no more than her son's attainment of the earldom of Richmond. However, Margaret may have believed that Richard III was a usurper and perhaps viewed him as guilty of the murder of his nephews. It may have been this that encouraged her to press for Richard's deposition and his replacement with her son. At Bosworth in 1485, Henry Tudor defeated Richard and the final Yorkist king was slain. It was a moment of triumph for Margaret. Her son duly married Elizabeth of York, but Margaret's influence was considerable during her son's reign. Known as 'My Lady the King's Mother', Margaret held property independently from her husband, and she administered justice in the king's name at several courts.

Margaret was revered for her education and her piety. In 1502, she founded the Lady Margaret's Professorship of Divinity at the University of Oxford, and three years later founded Christ's College, Cambridge. St John's was founded in 1511. She was politically astute, intelligent and resourceful. Historians have debated the nature of relations between Margaret and her daughter-in-law Elizabeth of York, but irrespective of their true feelings towards each other, the two women cooperated and worked together for much of Henry's reign. Margaret's death in 1509 followed that of her only son, for whom she had schemed and worked to ensure his accession to the throne. Lady Margaret Beaufort deserves to be remembered for her considerable successes.

Above: Henry VII, son of Margaret.

Above: Henry VII, son of Margaret.

Published on May 31, 2016 02:05

May 30, 2016

The End of Joan of Arc

On 30 May 1431, a young woman of nineteen years was burned to death in Rouen, Normandy. A year previously, Joan of Arc (known to the French as La Pucelle d'Orleans, the maid of Orleans) had been captured by the Burgundians, who handed her over to the English. She had almost single-handedly revived French fortunes during the Lancastrian phase of the Hundred Years' War between the traditional enemies England and France. Now, she was to die a shameful death, associated with witchcraft and heresy, a perversion of the natural order of things.

Joan had been born in northeastern France in around 1412, in an area that remained loyal to the French crown despite being close in proximity to Burgundian lands. At the age of thirteen, Joan reportedly experienced visions while in her father's garden. She saw the figures Saint Michael, Saint Catherine and Saint Margaret, who instructed her to bring about the expulsion of the English from France, and to bring the Dauphin to Reims for his coronation. Thus began Joan of Arc's mission, as she perceived it. Her experience thus far could be viewed as a sign of God's favour, uniquely bestowed upon her, but to others it betokened witchcraft.

Joan later visited the court of Charles VII, and she was financed with an army by the king's mother-in-law Yolande of Aragon. Joan requested to be equipped for war and to be placed at the head of the king's army; her requests were duly granted. Stephen W. Richey notes: 'Only a regime in the final straits of desperation would pay any heed to an illiterate farm girl who claimed that the voice of God was instructing her to take charge of her country's army and lead it to victory'. The king perhaps viewed Joan as sent from God, the means by which France could be delivered from subjection to England. Her presence offered the promise of French independence and French victory. Others, however, were concerned; they wondered whether Joan was a heretic or a sorceress, while her decision to wear the clothing of a soldier would later be brought against her. In response to initial concerns about Joan, a commission of inquiry at Poitiers concluded that Joan was 'a good Christian' and 'of irreproachable life'. Shortly afterwards, Joan visited the besieged city of Orleans in April 1429, and was present at the councils and battles thereafter.

Above: Charles VII of France.

Above: Charles VII of France.

Joan believed that she had been instructed by God to drive the English from France and ensure that the dauphin was crowned; as she saw it, her mission was a holy one. The lifting of the siege at Orleans was perceived by contemporaries as evidence that Joan truly was God's messenger, and she gained the support of the archbishop of Embrun and the theologian Jean Gerson as a result. Joan later provided the Duke of Alencon with advice about strategy. After the lifting of the siege and the battle of Patay, which was a decisive victory for the French, Joan accompanied the victors on the march to Reims.

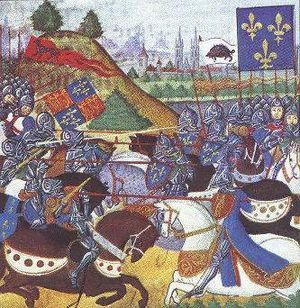

Above: The Battle of Patay, June 1429.

Above: The Battle of Patay, June 1429.

Reims opened its gates on 16 July 1429, and the coronation took place the following morning. The French army accepted peaceful surrenders from towns near the capital. In December that year, Joan and her family were ennobled by a grateful Charles VII as a reward for her actions. Six months later, she was present at the siege of Compiegne, the scene of her final military action. Joan was ambushed and captured; later, she was imprisoned by the Burgundians at Beaurevoir Castle. She made several escape attempts, including jumping from a window 70 feet high, but miraculously survived, which was for her supporters another sign of her divine favour. Later, Joan was moved to Rouen.

Above: Joan of Arc's entry into Reims in 1429; painting by Jan Matejko.

Above: Joan of Arc's entry into Reims in 1429; painting by Jan Matejko.

In early 1431, Joan's trial began. It was a contentious affair and several of the clergy had to be threatened with their lives to participate in it. These threats and the domination of the trial by a secular government actually violated the rules of the Church. Usually, a heresy trial should be conducted without secular interference. Ecclesiastical law was further violated by the refusal to allow Joan a legal adviser. Joan was charged with heresy and cross-dressing, a heinous offence in fifteenth-century eyes since it violated the natural order. Joan explained that she had chosen to wear male attire to protect herself from molestation; others testified that her dress had been taken by the guards and she had nothing else to wear. On 30 May, her execution took place. Burning at the stake was the customary method of execution for those found guilty of heresy. A crucifix was held before her by two of the clergy as she was tied to the stake. Her remains were cast into the Seine river. Some, at least, believed that a saint had been burned.

Two decades after her death, in 1452, a retrial was ordered, authorised by Pope Callixtus III at the request of Inquisitor-General Jean Brehal and Joan's mother, Isabelle. A formal appeal followed three years later, and in the summer of 1456, the court declared that Joan was innocent. She was canonised by Pope Benedict XV on 16 May 1920.

In a short but extraordinary life, Joan of Arc was perceived in the contradictory guises of woman, warrior, saviour, heretic, witch, and saint. Following her death, she became something of a legendary figure and has inspired many by her bravery and willingness to die for her faith. She was certain that she had been chosen by God to ensure France's total victory over the English; it was the driving force in her life. Since her death, Joan has inspired artistic and cultural depictions for six centuries. Ultimately, although she did not live to see it, France's victory in the Hundred Years' War lent credence to the legitimacy of Joan's mission, signifying that she had indeed been favoured by God. Her retrial served to vindicate Joan, and in death she has been granted the admiration and awe that was largely denied to her in life.

Published on May 30, 2016 01:17

May 1, 2016

'Now Take Heed What Love May Do'

The exact date on which King Edward IV married Elizabeth Wydeville is uncertain, but traditionally they are held to have married on, or about, 1 May 1464. In literature, Mayday had long been associated with romance, chivalry and passion. The selection of the date was appropriate, because Edward's marriage to Elizabeth appears to have been a love match.

The marriage took place in circumstances of secrecy. Elizabeth's mother Jacquetta attended - and perhaps arranged the match - as did an unnamed priest. Two gentlewomen also attended. Contemporary writers and chroniclers later wrote, variously, that Elizabeth had enchanted the young king under an oak tree; that she had defended herself with a dagger when he attempted to force himself upon her; or that he threatened her with a dagger.

Edward has been criticised by modern historians for selecting Elizabeth as his bride. However, there were good reasons to marry her. Firstly, she was undoubtedly fertile. She had already produced two sons in her first marriage, and she herself had thirteen siblings. Clearly, from Edward's perspective, Elizabeth came from good stock and would be able to produce sons, which was the primary duty of the medieval queen. Secondly, as later events would show, Elizabeth was beautiful, intelligent, charismatic, pious and ambitious. Thirdly, she was descended from the ducal house of Luxembourg, and could in theory offer her husband a prestigious foreign alliance. Fourthly, she had been married to a Lancastrian knight and the Wydevilles had traditionally supported the Lancastrian regime, so marriage to Elizabeth offered Edward the opportunity to heal the divisions between the warring houses of Lancaster and York.

On the other hand, Edward's choice was surprising to his contemporaries, because Elizabeth was not a foreign princess; marriage to a French princess would have been more profitable both for Edward and for his kingdom. The earl of Warwick had been negotiating for the king to wed Bona of Savoy. By marrying an English widow, Edward failed to consolidate his position, which was a risky policy given that he was a usurper. The situation in England remained precarious, and marriage to a foreign princess would have offered the promise of foreign military and diplomatic support, in the wake of further conflict and bloodshed. Secondly, the marriage alienated Warwick, who had supported Edward until that point. There is no evidence that the nobility as a whole resented the Wydevilles, but they were certainly disliked by Warwick, and he was a dangerous enemy to have, as events were to prove.

In defying convention, Edward behaved exactly like his future grandson Henry VIII, who married four English women, at least two for love. King Edward has often been viewed as a serial womaniser, and indeed it is possible that he was actually married to Eleanor Talbot before marrying Elizabeth Wydeville. The king could not have known it, but his previous involvement with Eleanor was to jeopardise his marriage to Elizabeth. In Richard III's reign, the Wydeville marriage was declared invalid and the children of Edward and Elizabeth were declared illegitimate and unfit to succeed.

In September 1464, Edward finally admitted that he had married Elizabeth. She was crowned queen on 26 May 1465, and gave birth to their first child, a daughter named Elizabeth, in February 1466. The marriage seems to have been a successful one. Elizabeth demonstrated her suitability to be queen and was praised for her constancy and modest behaviour, particularly during the troubles of 1470. Ultimately, it was their daughter Elizabeth's fate to be queen of England as the wife of Henry VII.

Published on May 01, 2016 05:10

April 14, 2016

The Children of Edward IV and Elizabeth Wydeville

The marriage between the first Yorkist king, Edward IV, and Elizabeth Wydeville was highly controversial in the fifteenth-century. There were doubts over its legitimacy, and some modern historians believe that Edward's first marriage to Lady Eleanor Butler rendered the Wydeville marriage invalid. This blog post does not seek to explore whether Edward's marriage to Elizabeth was valid or not. Rather, it is concerned with the offspring of the Wydeville marriage.

Queen Elizabeth proved to be a fertile bride. In nineteen years of marriage, she gave birth to ten children: seven daughters and three sons. All of the sons died young, and two of the daughters did not live to adulthood. The eldest child, Elizabeth, became Queen of England in the summer of 1485, when she married Henry VII, the first Tudor king. Her brother was Edward V, who had been imprisoned in the Tower of London with his younger brother Richard when their uncle, the duke of Gloucester, usurped the throne in 1483. Mystery surrounds the fates of the 'Princes in the Tower', as they came to be known. Most modern historians believe that they were likely dead by the autumn of 1483.

Queen Elizabeth Wydeville was close to her children, particularly her eldest daughter Elizabeth. This blog post explores the lives of the children of King Edward IV and Queen Elizabeth.

Elizabeth of York (1466-1503)

Elizabeth of York (1466-1503)

The eldest child of King Edward and Queen Elizabeth was a daughter. She was born at Westminster Palace on 11 February 1466, and was named for her mother. While young, Elizabeth was briefly betrothed to George Neville, first duke of Bedford. This was not the match that the king and queen had envisaged for their eldest daughter, but the match was proposed with a view to continuing the friendship between the house of York and the Neville earls of Warwick. When George's father joined forces with his brother, the 'Kingmaker' duke of Warwick, the betrothal was called off. In 1475, in alliance with Louis XI of France, King Edward arranged a betrothal between his daughter and Charles, the French dauphin. It would have been a splendid marriage for Elizabeth, had it have gone ahead, and it would have enabled her to become Queen of France. However, it was not to be. Elizabeth's father died in 1483, and following the accession of her uncle Richard, Elizabeth accompanied her mother into sanctuary, with her other siblings. A year later, Elizabeth left sanctuary with her sisters, and they arrived at court. It is likely that they resided in the household of Queen Anne. Rumours of the queen's imminent demise fuelled speculation that King Richard was planning on marrying his niece. Whether Elizabeth truly considered marrying Richard is a mystery, and has been furiously debated by historians. It is entirely likely that she did scheme to marry her uncle, but ultimately his death at Bosworth in 1485 compelled her to honour her prior agreement to marry Henry Tudor, who had become king.

Elizabeth and Henry, to all appearances, enjoyed a warm and loving marriage. Elizabeth gave birth to seven children; three of them survived to adulthood. She appears to have been a popular queen consort and was praised for her acts of intercession. Mystery surrounds much of Elizabeth's life. We do not know the true nature of her relations with her resourceful mother-in-law, Lady Margaret Beaufort. Nor do we know whether she really believed that her younger brothers had been murdered. Whether she loved Henry or not, she was a dutiful wife and a loving mother to their children. She died in 1503, on her thirty-seventh birthday. Her son, who later became Henry VIII, was said to have been devastated by her death.

Mary of York (1467-1482)

Mary of York (1467-1482)

Mary was the second child of Edward and Elizabeth. She was born on 11 August 1467 at Windsor Castle. Very little is known about her. There were rumours during her childhood that she would marry John, the Danish king. In 1480, at the age of thirteen, she became a Lady of the Garter alongside her younger sister Cecily. Mary died on 23 May 1482 at the age of fourteen. She was buried at St. George's Chapel at Windsor Castle, where her parents would later be buried. Her early death meant that Mary did not experience the drama of the following year, when her father died, her brother was deposed and her uncle became king.

Cecily of York (1469-1507)

Cecily of York (1469-1507)

Cecily of York's life is one of drama. The events of her life suggest that she seems to have been a strong-minded, impulsive woman. Cecily was born at Westminster Palace on 20 March 1469, and was likely named after her grandmother, the duchess of York. At the age of seven, she was betrothed to the future James IV of Scotland. Cecily would have grown up believing, at least for a time, that it was her destiny to be Queen of Scotland. However, it was not to be. In 1482, when Cecily was thirteen, she was betrothed to Alexander Stewart, duke of Albany. However, the death of Edward IV the following year put paid to any hopes Cecily may have had of marrying Albany. On her uncle Richard III's orders, she and her siblings were declared illegitimate, on the grounds that the marriage of Edward and Elizabeth Wydeville was invalid. However, Richard knew that Cecily remained attractive as a prospective bride. To counter this, he arranged for her to marry Ralph Scrope of Upsall, a younger brother of Richard's supporter Thomas Scrope. It was surely not a match that Cecily had desired; given that she had been betrothed at one time to the heir to the Scottish crown, it is entirely possible that she was bitterly disappointed, perhaps even resentful.

Henry VII's accession, however, changed Cecily's fortunes. The Scrope marriage was annulled and, two years after Richard III's death, Cecily remarried. Her second husband was John Welles, first Viscount Welles, who was a maternal half-brother of Lady Margaret Beaufort and was, therefore, half-uncle to Henry VII. Again, it was probably not the match that Cecily had wanted, but it is possible that the couple were happy. They had two daughters, Elizabeth and Anne, both of whom died young. Viscount Welles died in around 1498.

It is in the aftermath of her second husband's death that we are able to gain an insight into Cecily's personality. One commentator reported that she chose to marry for a third time for 'comfort': perhaps she sought love, or stability. Her third husband was an obscure Lincolnshire esquire, Thomas Kyme. It seems to have been a love match. However, Cecily was reckless in failing to secure Henry VII's consent to the marriage, which she was required to do, as a member of the royal family. The king was furious and banished his sister-in-law from court. Lady Margaret, who appears to have been fond of Cecily, interceded for her and some of Cecily's lands were restored to her. Cecily died in 1507 at the age of thirty-eight, and she was buried at Hatfield, Hertfordshire.

Edward V (1470-1483?)

Edward V (1470-1483?)

The eldest son of King Edward and Queen Elizabeth was born on 2 November 1470 in Westminster Abbey. The queen had sought sanctuary after the Lancastrians had forced the king to flee his realm. However, King Edward emerged victorious and the prince was brought out of sanctuary. He was created Prince of Wales the following year. Prince Edward was reputedly learned, diligent, and dignified.

The birth of a son to the royal couple was highly important: it brought security to them, and offered the promise of future prosperity as well as the continuation of the dynasty. However, it was not to be. When he was only twelve years old, Prince Edward became King Edward V, upon the unexpected death of his father. However, his uncle Richard seized the throne. Edward was lodged in the Tower of London alongside his younger brother Richard, duke of York. Like his siblings, the new king was declared illegitimate and unfit to succeed to the throne.

Mystery surrounds Edward's fate. Contemporaries speculated a great deal about what had happened to him. Some outright accused King Richard of murdering him and his brother. Others believed that the king had died in the Tower from illness. The majority of modern historians believe that Edward was dead by late 1483, which if true would mean that he never reached his fourteenth birthday (and possibly not his thirteenth). Edward V is one of the shortest reigning monarchs in English history.

Richard, duke of York (1473-1483?)

Richard, duke of York (1473-1483?)

Richard was born on 17 August 1473 in Shrewsbury, and may have been named for his grandfather Richard, duke of York; alternatively, he may have been named for his uncle, Richard, duke of Gloucester. At the age of four, Prince Richard married the five-year-old Anne Mowbray, countess of Norfolk, at Westminster in January 1478. This appears utterly bizarre to modern readers. The marriage occurred on account of the king's determination to secure the Mowbray estates. Anne died in 1481, and her estates should have passed to William, Viscount Berkeley and to John, Lord Howard. However, an act was passed in 1483 that granted the Mowbray estates to Prince Richard for his lifetime, and to his heirs, if he had any, when he died. The whole episode was an example of King Edward IV's capacity for rapacity and ruthlessness when it came to acquiring greater wealth.

The declaration made in the spring of 1483, following Edward IV's death, that the children of the Wydeville marriage were illegitimate on account of their father's previous marriage to Lady Eleanor Talbot, rendered Prince Richard a bastard. The prince was escorted to the Tower of London, to join his brother, Edward V. Most historians believe that Richard was killed on the orders of King Richard; others suggest that he was put to death, but on another individual's orders: possibly Henry Tudor; possibly the duke of Buckingham; or possibly Lady Margaret Beaufort.

However, others believe that Richard escaped abroad. One line of thought posits that the pretender Perkin Warbeck, who was a menace to Henry VII, was actually Richard, duke of York, come back to claim his inheritance.

Anne of York (1475-1511)

Anne of York (1475-1511)

Anne was born on 2 November 1475 at Westminster Palace. In the summer of 1480, her father signed a treaty agreement with Maximilian I, duke of Austria, and it was agreed that Anne would marry the duke's eldest son Philip. This would have been a most prestigious marriage for Anne, for it would have enabled her to become duchess of Burgundy. Following Richard III's accession, the nine-year-old Anne was betrothed to Thomas Howard (later the uncle of Anne Boleyn and Katherine Howard) in 1484. Even after Richard's death, Howard remained eager to marry Anne. They married at Westminster Abbey on 4 February 1495. None of their children survived.

Anne was close to her sister Queen Elizabeth, and like her sister Cecily, she played an important role in court ceremonies. She carried the chrisom at the christenings of her nephew Arthur, in 1486, and niece Margaret in 1489. Anne died on 23 November 1511 and was buried at Thetford Priory in Norfolk. Later, her body was moved to the Church of St Michael the Archangel in Framlingham.

Katherine of York (1479-1527)

Katherine of York (1479-1527)

Aside from her sister Elizabeth, Katherine of York made the best marriage of any of the York children. She was born on 14 August 1479 at Eltham Palace. In childhood, Katherine had been betrothed to Juan, the heir to the kingdoms of Castile and Aragon (he was the older brother of Katherine of Aragon). Upon Henry VII's accession, Katherine was betrothed to James Stewart, duke of Ross. The same agreement envisaged marrying Katherine's mother, the dowager queen Elizabeth Wydeville, to James III of Scotland. These plans came to nothing, and in 1495, the same year her sister Anne married Howard, Katherine married William Courtenay, earl of Devon.

Again, it may not have been the marriage that Katherine had wanted, but it ensured that she was a countess. They had three children: Henry (who was executed in 1539 for plotting against Henry VIII); Edward (who died young); and Margaret (who married Henry Somerset, earl of Worcester). Her husband died in 1511. Following his death, Katherine swore a voluntary vow of chastity in the presence of the bishop of London. She was reportedly favoured by her nephew Henry VIII, who 'brought her into a sure estate'. Katherine died on 15 November 1527 at Tiverton Castle, the last of Edward IV's children to die.

Bridget of York (1480-1517)

Bridget of York (1480-1517)

Bridget was the youngest child of King Edward and Queen Elizabeth. She was born on 10 November 1480 at Eltham Palace. It is likely that Bridget was named after St. Bridget of Sweden. It seems that the king and queen decided, while Bridget was still young, that their youngest daughter would follow a religious life. At an unknown date between 1486 and 1492, when she was between the ages of six and twelve, Bridget was entrusted to Dartford Priory in Kent. Her sister, Queen Elizabeth of York, continued to write to her and send messengers. Bridget attended the funeral of her mother, Elizabeth Wydeville, in 1492. She died in 1517, and in some respects is the most obscure of Edward IV's daughters.

Children who died youngMargaret of York (born and died 1472)George, duke of Bedford (1477-1479)

Margaret of York was born on 10 April 1472 at Winchester Castle in Hampshire. She was likely named for her aunt, Margaret, duchess of Burgundy. Tragically, Margaret died at the age of only eight months, on 11 December 1472. She was buried in Westminster Abbey.

George of York was born in March 1477 at Windsor Castle. The following year, he was created duke of Bedford. The dukedom of Bedford had long been associated with the royal family. That same year, George was appointed lord lieutenant of Ireland. He died in 1479 at the age of two, perhaps from plague, and was buried in St George's Chapel at Windsor Castle, where his parents were later buried.

Published on April 14, 2016 08:44

March 10, 2016

Katherine Swynford: Enduring Interest

Above: Katherine by Anya Seton.

Katherine Swynford, duchess of Lancaster, is one of the most fascinating women in medieval English history. Most people know Katherine from Anya Seton's novel, published in 1954. Anya's Katherine is passionate, beguiling and ultimately loveable. The novel ripples with emotion, and its heroine is charismatic and memorable. At heart, it is a romantic novel, and the legendary relationship between Katherine and John of Gaunt is presented as one of passion. Whether this fictional depiction can be viewed as historically accurate is impossible to say, but Seton's reading is plausible, given that we know Katherine was John's mistress for many years before he finally married her. She became his third, and perhaps most beloved, wife.

As far as facts go, we know very little about the real woman, which is unsurprising given that she lived over six hundred years ago. Katherine Swynford was the daughter of the herald Paon de Roet, and she was born around 1350. Seton's novel depicts her as only having one sister, Philippa, but it is likely that she in fact had two (the other being Isabel). Katherine's sister Philippa, who may have been younger than Katherine, went on to marry the poet Geoffrey Chaucer, who is best known for his work The Canterbury Tales, a stunning insight into medieval English life that is replete with humour and wit.

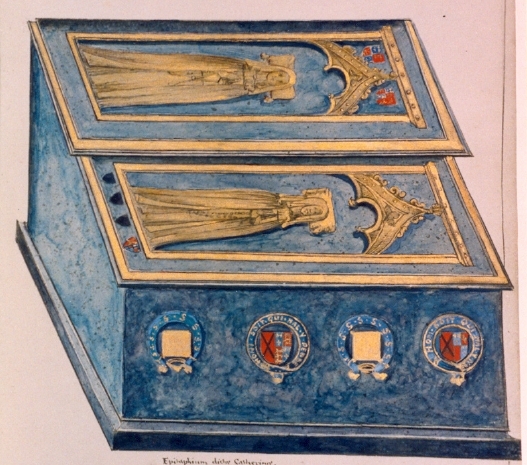

Above: The tomb of Katherine next to that of her daughter Joan.

Above: The tomb of Katherine next to that of her daughter Joan.

Katherine's first marriage was to the knight Hugh Swynford; their wedding probably occurred in 1366, when she was about sixteen. After their wedding, Hugh and Katherine resided at the manor of Kettlethorpe in Lincolnshire. By him, Katherine had three children. In the novel Katherine, the relationship between Hugh and Katherine is complex. They do experience affection for one another, but it is clear that Katherine's love for John of Gaunt takes precedence over any feelings she has for her husband Hugh. Later, Katherine became the governess of Philippa of Lancaster and Elizabeth of Lancaster, the daughters of John of Gaunt.

The love affair between Katherine and John is swathed in mystery, but it has been the subject of considerable attention ever since it took place. Artists, novelists and filmmakers have endlessly speculated about Katherine's relationship with John. In the novel, the two are acquainted at court and experience an instant, powerful attraction for one another that ends only with death. The truth, however, is much less certain. It may only have been when she became governess to his daughters that Katherine fell in love with John. It is entirely possible, moreover, that Katherine was more ambitious than has been traditionally thought. John of Gaunt was the third surviving son of King Edward III. While it may not have seemed likely that he would ever become king himself, he was Duke of Lancaster, probably the most powerful and influential nobleman in the kingdom. Wealth and riches were at his fingertips.

Above: A later portrait of John of Gaunt, duke of Lancaster.

Above: A later portrait of John of Gaunt, duke of Lancaster.

By this time, John's first wife Blanche had died. The first duchess of Lancaster had been much-beloved; in life she had been strikingly beautiful, gracious and virtuous. Her young death was viewed as a sorrowful tragedy, and John was believed to have felt deep grief at her passing. His second marriage, to the Infanta Constance of Castile, was an entirely political match. John married her because he was ambitiously hoping to become King of Castile. The marriage ensured that the duke obtained a kingdom of his own, perhaps because he was aware that it was unlikely that he would become king of England. Constance died in 1394.

Katherine's love affair with John had begun shortly after Blanche's death. It was, however, to ruin Katherine's reputation: she was slandered as a 'scandalous' whore. The duke was highly unpopular himself, for he was viewed as unscrupulous and scheming. At some point, Katherine's husband died, and the unmarried Katherine's reputation suffered as a result of her relations with John. By him, she bore four children. Following Constance's death, John took the momentous step of marrying Katherine, thus legitimising their children. It was a true triumph for Katherine. No longer a disgraced whore, but a duchess by marriage, she attained what few royal mistresses could hope for: marriage with her royal lover. Tragically for the couple, John died only three years after their marriage. Katherine herself lived until 1403, when she died at the age of about fifty-three.

Above: Katherine Swynford's tomb.

Above: Katherine Swynford's tomb.

Katherine Swynford's life is extraordinary, not simply because of her love affair with one of the most powerful men in the kingdom. She lived at a remarkable time. Katherine lived through the flowering of English literature; her brother-in-law was the famed poet Geoffrey Chaucer, and it is reasonable to expect that she read his works herself. She was a young woman growing up during the celebrated reign of Edward III, who has been seen as one of England's greatest monarchs. And she experienced momentous political conflict, as embodied in the Peasant's Revolt of 1381.

Perhaps Katherine's real importance and fascination, however, lies in her legacy. Through her marriage to John of Gaunt, which ensured that their children were declared legitimate, Katherine was the ancestress of the Tudor dynasty. We may know very little about the real woman's life, but Katherine Swynford has been immortalised in fiction as a passionate, charismatic and determined woman. A royal mistress and later duchess of Lancaster, her life will likely forever remain one of enduring interest.

Published on March 10, 2016 13:51

February 13, 2016

Katherine Howard and Hampton Court Palace

Above: Portrait of an unknown woman, possibly Katherine Howard (left).

The Haunted Gallery at Hampton Court Palace (right).

On 13 February 1542, two women were executed for treason within the walls of the Tower of London. On the same spot on which Anne Boleyn had been beheaded six years earlier, Katherine Howard was executed after making a short speech. Mercifully, her head was removed with a single blow of the axe. Following her death, it was the turn of her attendant Jane, viscountess Rochford. The viscountess had allegedly gone insane during her imprisonment; yet so determined was Henry VIII for her to die that he had her nursed back to health. Like the former queen, Jane was decapitated with a single strike. Both ladies were buried in the chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula.

It is often believed that Katherine was executed for committing adultery with Thomas Culpeper, a groom of the privy chamber, but the Bill of Attainder passed against her clarified that she was condemned for having lived 'an old abominable life'. The attainder explained that Katherine's decision to appoint a former lover, Francis Dereham, to the position of secretary was 'proof of her will' to return to her 'vicious life'. In this respect, it was Katherine's unchaste childhood that counted against her. When it was discovered that she was not a virgin when she married Henry VIII, her meetings with Thomas Culpeper took on a sinister light. The Bill of Attainder became law on 11 February, a day after the queen had been taken to the Tower. Two days later, she and Jane Rochford were beheaded. Neither had been given the right to a trial, as Anne Boleyn had in 1536. The Act of Attainder was later repealed in the reign of Mary I.

Having endured imprisonment for two months, Katherine's end came astonishingly quickly. Within three days she was imprisoned in the Tower and then executed. The Spanish ambassador Eustace Chapuys reported that Katherine had to be forced onto the barge 'with some difficulty and resistance' when it arrived to transport her to the Tower. Although both she and Jane were to die with dignity, rumours abounded both then and now that Katherine Howard's spirit was restless. This idea soon became legend with the story of Katherine's ghost haunting a gallery at Hampton Court Palace.

Joanna Denny, in her biography of Katherine, explains this legend:

'There is a legend at Hampton Court Palace that Katherine Howard made one last, desperate attempt to see her husband. The story goes that, knowing Henry was at service in the Chapel Royal, she broke free of her rooms and ran down the long gallery to try and talk to him and convince him of her innocence.

...It is said that Katherine's ghost is seen here, running and screaming in her panic as she calls Henry's name... She was presumably caught long before she came anywhere near the King and dragged away by her guards'.

Hampton Court Palace, on its website, provides 'anecdotal evidence' to confirm that the story is true: visitors to the gallery are often unsettled by a strange presence in the gallery, and some have fainted before. The story has moved into the realm of popular culture, and the link between Katherine Howard and the Haunted Gallery is well-known.

It's not hard to see why. The image of a teenage queen, paralysed by fear and terror, running and begging for her life is a haunting one. The legend is often included in modern novels, such as Jean Plaidy's Rose Without a Thorn, and it is occasionally referenced in television, as in the Showtime series The Tudors (2007-10). But historians have, by and large, demonstrated that the myth is exactly that: a myth. There is no contemporary evidence that Katherine Howard ran down the gallery screaming for her life; none of the court ambassadors, including the well-informed Chapuys, reported it.

Hampton Court Palace is central to the story of Katherine Howard. Its setting was the centre piece of her spectacular rise and was to prove the site of her calamitous downfall. Unsurprisingly, then, Katherine's ghost is almost never linked with the Tower of London, but it is always associated with Hampton Court. As a young maid of honour to Queen Anne of Cleves, Katherine had captivated the ageing Henry VIII; perhaps their first meeting occurred at Hampton Court. In August 1540, less than two weeks after Katherine married Henry at Oatlands Palace, she was acknowledged as queen for the first time at Hampton Court. Formerly in the hands of Cardinal Wolsey, it had become, by the 1540s, Henry VIII's main residence.

As it had been the main setting for her rise to queenship, so Hampton Court was to be the setting for Katherine's downfall. Returning from the northern progress in the autumn of 1541, Henry VIII was confronted with a letter placed in the Chapel Royal informing him of his wife's unchaste childhood. Devastated, he departed the palace, never to see her again. The disgraced queen was eventually moved from Hampton Court to Syon, before making her final journey to the Tower of London.

In January 2016, I visited Hampton Court Palace for a ghost tour held one evening. The final stop on the tour was at the Haunted Gallery, where the story of Katherine Howard's ghost was recounted by the guide. Undeniably, the Gallery has an unsettling atmosphere, especially at night. One's imagination can run away; it is easy to imagine a frightened girl frantically running down the Gallery, screaming and begging for her life before being seized by her guards and taken back to her rooms. While the story of Katherine's ghost has no basis in reality, it does provide a poignant, chilling reminder of the speed of her downfall and death. For Katherine Howard, Hampton Court Palace was initially associated with happiness, glory and possibility, but it later became for her a site of fear, terror and destruction.

Published on February 13, 2016 03:10

February 12, 2016

Remembering Lady Jane Grey

On 12 February 1554, Lady Jane Grey was executed within the walls of the Tower of London. Three months earlier, she and her husband Guildford Dudley had been found guilty of high treason. They had unlawfully usurped the throne from the rightful queen, Mary I. Traditionally, historians presented Lady Jane as an unwilling innocent, a much wronged young girl who had no desire whatsoever to be Queen of England. Recent research has disproved this legend. In actuality, Lady Jane was an intelligent, stubborn and resilient woman who was fiercely devoted to her Protestant faith. She regarded herself as appointed by God to rule England, and she likely regarded her Catholic cousin Mary Tudor as ungodly, even abominable in the eyes of God. He had chosen Jane to be Queen, and she believed it was her destiny to be sovereign of England.

Having been selected as Edward VI's heir, Jane was proclaimed queen in July 1553. As is well known, Jane's regime collapsed within days, and Mary was declared queen on 19 July. Jane's trial followed in November, and although she and her husband were found guilty, Queen Mary showed no desire to have them put to death. However, the outbreak of rebellion in early 1554, motivated by dislike of Mary's decision to marry Philip of Spain, coupled with the decision to reinstate the medieval heresy laws, sealed Jane's fate. Her own father was involved in the plot against the queen, and he followed Jane to the scaffold a few days after her own death. A courageous and resourceful young woman, Jane accepted her fate and bravely prepared for death.

Above: The traditional view of Lady Jane Grey, as portrayed in Paul Delaroche's nineteenth-century painting, as a wronged innocent.

Above: The traditional view of Lady Jane Grey, as portrayed in Paul Delaroche's nineteenth-century painting, as a wronged innocent.

Guildford Dudley was executed on the morning of 12 February 1554 on Tower Hill, where his father, the duke of Northumberland, had died the previous August. Guildford was himself still a teenager, perhaps no more than nineteen years old, and has been the victim of notable slanders. Modern historians have usually depicted him as a snivelling, weak-willed and vicious adolescent, loathed by Jane, but Leanda de Lisle's research questions whether this portrayal is accurate, as no contemporary source describes Guildford in such a negative way. Whatever the truth of Guildford's character, his end was tragic. Like Jane, he was the victim of his father's plotting, and he duly resigned himself to his fate. His wife was confronted by the sight of her husband's headless corpse, the fabric stained with his blood, returning on a cart from Tower Hill. She knew that her own demise was imminent.

Shortly afterwards, around ten in the morning, Lady Jane Grey walked out of her apartments and mounted the scaffold that had been built within the walls of the Tower. Onlookers commented on her braveness and her piety. Two versions of her scaffold speech survive, both of which confirm that she acknowledged that she was to die under the law, having been condemned by it. She confirmed that she had offended the queen and had behaved unlawfully. Most importantly, particularly for her posthumous reputation, Jane proclaimed that she died a true Christian woman, and looked to be saved only by Christ's mercy. This confirmed her commitment to the Protestant faith, for Catholics traditionally believed that good works also played an important part in one's salvation. She then asked the onlookers to pray for her.

Above: Queen Mary I, who ordered her cousin Lady Jane Grey's execution in February 1554.

Above: Queen Mary I, who ordered her cousin Lady Jane Grey's execution in February 1554.

Lady Jane's female attendants then helped her off with her gown and gave her a handkerchief to use as a blindfold. Groping about in the dark, she could not find the scaffold, and cried, "Where is it? What shall I do?" Someone came forward to guide her and she rested her head upon the block. Mercifully, she was decapitated with one blow, probably just a few months short of her seventeenth birthday. Her remains were interred in the nearby chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula. With her passing, Lady Jane Grey's story became the stuff of legend. In Protestant works, most notably John Foxe's Book of Martyrs, she was depicted as a pious, virtuous Protestant maiden who had died for her faith, condemned by the cruel Catholic tyrant, Mary I. Victorian historians depicted her as an innocent victim of her grasping, scheming family, and portrayed Jane's mother, Lady Frances Brandon, as a tyrannical woman and an abusive mother. Modern historians have usually followed this version of events. But modern research has demonstrated that reality was more complex. Lady Jane Grey was far more than merely an innocent child, and there is no contemporary evidence to suggest that Frances was cruel to her daughters.

Lady Jane Grey remains, in many respects, a mystery. Her beheading was the first of several calamities to befall the Grey family. Her father followed her to the scaffold only eleven days after her own death; like her, he was executed as a traitor to his queen. In spite of this, Jane's mother, Frances, remained close to Queen Mary, and her younger daughters Catherine and Mary were resident at court. However, Elizabeth I's accession proved to be the final undoing of the Grey family. While she did not behead either of the Grey sisters, as Mary had done, Elizabeth had both Catherine and Mary Grey imprisoned for their clandestine marriages, and the distraught Catherine died in 1568 while still in her twenties, deprived of her husband and children. Mary followed her to the grave ten years later, her own husband having predeceased her. Lady Jane Grey's story has been represented as a great tragedy, but her younger sisters were as much victims of their birth as she was.

Published on February 12, 2016 13:39