Conor Byrne's Blog, page 7

July 12, 2015

12 July 1543: Henry VIII Marries Katherine Parr

On 12 July 1543 at Hampton Court Palace, King Henry VIII of England married for the sixth and final time. His bride was thirty-one year old Katherine Parr, the eldest daughter of Thomas and Maud Parr. Unlike Anne Boleyn, Jane Seymour or Katherine Howard, Katherine Parr had not spent time in royal service, although both her siblings had operated in court circles for a number of years. Known as the most married queen of England, Katherine was marrying for the third time.

Although she was not rated for her beauty, Katherine's intelligence, charisma, and deep-rooted passion for the Protestant religion were to become well known at court. She reigned until January 1547, when her mercurial husband died aged fifty-five. Katherine was not the dull, dowdy figure of Victorian historiography. She was not only a devout Protestant but an author, a literary patron, a lover of fashion and a patron of the arts. She enjoyed warm relationships with her three stepchildren and was particularly influential on her stepdaughter Elizabeth.

I recently wrote an article exploring whether Katherine Parr could be said to have espoused feminist ideas in her written works. Of course, it is anachronistic to interpret these opinions as feminist, but Katherine certainly believed with some conviction that women, as well as men, could play indispensable roles in advancing the Protestant faith. You can read the article here.

Published on July 12, 2015 08:37

July 6, 2015

6 July 1553: The Death of Edward VI

Above: King Edward VI of England.

July was usually a joyous month in early modern England. Before the advent of the Protestant Reformation, communities across the country participated in joyous summer pastimes that included village ales and games on the green. Edward VI's Reformation, of course, had swept away remnants of England's Catholic past. Yet, to those who remained superstitious, if the weather was anything to go by the early days of July 1553 were not fortuitous. Unseasonably chilly weather augured ill for the welfare of a kingdom that was already precarious. Those in the capital would have been privy to vague reports circulating of King Edward VI's alarmingly 'thin and wasted' condition. Although modern historians have convincingly dismissed the traditional view of Edward as an individual that was sickly from birth, forever close to death, it cannot be denied that the last year of the teenage king's life was agonising and painful.

Early in the year, the king had fallen ill with a fever and cough that worsened with the passing of time. The imperial ambassador reported: 'He suffers a good deal when the fever is upon him, especially from a difficulty in drawing his breath, which is due to the compression of the organs on the right side'. Although the king's health briefly improved in April, by June his doctors were openly voicing doubts that he would ever recover from what they called 'a suppurating tumour'. Edward's legs became so swollen that he had to lie on his back. He allegedly informed his tutor John Cheke: "I am glad to die".

The end, when it came, came suddenly. Between eight and nine pm on the evening of 6 July at Greenwich Palace, the fifteen-year-old king's fragile life drew to a close. The martyrologist John Foxe later stated that Edward died in the arms of his Chief Gentleman of the Privy Chamber, Sir Henry Sidney, to whom he whispered: "I am faint, Lord have mercy upon me, and take my spirit". Historians have debated what it was that the teenage king died of. The Venetian ambassador had opined that Edward's cause of death was tuberculosis, a view which historians have generally agreed with, although Loach suspects that he may have died of acute bronchopneumonia, which led to a 'suppurating pulmonary infection'.

Above: Lady Jane Grey (left) and Mary Tudor (right).

Several months earlier, in his "Devise for the Succession", Edward had stipulated that the crown was to pass to the male heirs of Lady Jane Grey, his cousin. As his health increasingly took a turn for the worse, and it remained apparent that Jane would not bear a son anytime soon, Edward altered the wording so that Jane herself could succeed him as queen following his death. Consequently, she was proclaimed queen in the aftermath of Edward's death. Four days after her cousin's passing, she travelled to the Tower of London in preparation for her coronation. It never occurred. Supported by the majority of the former king's subjects, Mary Tudor successfully took the crown and declared herself queen. On 19 July Mary was proclaimed queen by the Privy Council, and she was eventually crowned in October of that year.

Edward VI was king of England for only six years. Given his age upon succeeding to the throne, power was concentrated in the hands of the Privy Council and, more specifically, Edward Seymour, earl of Hertford and later duke of Somerset. Upon Somerset's fall from grace, the earl of Warwick (later duke of Northumberland) wrested control of the Council and was virtual ruler of the country until Edward's untimely death. Historians have debated whether it was Edward or Northumberland who masterminded the "Devise for the Succession", but more recently, it has compellingly been demonstrated that it was the determined king who commanded that his cousin Jane, rather than his sister Mary, should inherit the crown upon his death. In the end his wishes proved of no avail. Mary became queen and the teenaged Jane was executed alongside her husband in February 1554. Edward's reign is best known for the intensity of the Protestant Reformation. Had he lived longer, and wielded power himself rather than being controlled by the likes of Somerset and Northumberland (as he would have done in time), then Edward's reign might be remembered very differently. Instead, he remains one of the more shadowy of the Tudors, a boy king who died before his sixteenth birthday.

Published on July 06, 2015 11:46

June 25, 2015

25 June 1533: The Death of Mary Tudor, Queen of France

On a midsummer day in late June, the former queen of France lay dying at her residence of Westhorpe Hall in Suffolk. Mary Tudor, the universally acknowledged beautiful younger sister of Henry VIII, was only thirty-seven years of age at the time of her death. Fiery, charismatic and passionate, Mary is perhaps better known for being the beautiful duchess of Suffolk rather than queen of France, a position she occupied for only three months. The 'white queen', as Mary has sometimes been known, was surrounded by only a few attendants in the gentle seclusion of her Suffolk estate. It is entirely possible that her husband was not at her side in her last hours.

In her youth, Mary had been described as 'a Paradise - tall, slender, grey-eyed, possessing an extreme pallor'. She was born at the palace of Sheen in March 1496, the youngest surviving child of Henry VII and Elizabeth of York. When she was only six years old, her eldest brother Arthur died and her mother followed Arthur to the grave only ten months later. Mary appears to have been close with her brother Henry, later Henry VIII. He was to name his only surviving child after her, a princess born in 1516.

Mary had been married to Charles, duke of Suffolk since May 1515. Their marriage had scandalised Europe and had outraged King Henry, who was furious with the couple's failure to secure royal permission for their marriage. The couple were fortunate to escape with a heavy fine: by the standards of the time, Henry's honour had been disparaged by his sister's actions, and her husband the duke could have been imprisoned or even executed. Although the king and his younger sister had traditionally been close, their relationship was further strained after 1527, when Henry pursued marriage with Anne Boleyn. Mary was close to his wife, Katherine of Aragon, whom she had known since her early years. As David Loades writes, Mary and Anne 'exchanged insults of a semi-public nature'. Henry's annoyance with his sister's behaviour means that he seems to have failed to mourn her death. He left no comment when informed of her demise, although this reaction is perhaps explained by the fact that he had just remarried and was spending time with his new consort.

Mary's widower, Charles Brandon, was left with three children: Frances (born in 1517; she married Henry Grey the same year); Eleanor (born in 1519); and Henry (who was to die the following year). Less than three months after his wife's passing, the duke remarried. His second wife was fourteen-year-old Katherine Willoughby. The thirty-five year age difference between the duke and his teenage bride did not pass without comment, but the marriage was a successful one.

In the story of the early Tudors, Mary tends to be overshadowed by her volatile brother and the drama of his six marriages. Yet she was a passionate, intelligent and charismatic woman who was a teenaged Queen of France and who caused considerable controversy when she decided to marry her husband's favourite without seeking royal permission. Two decades after Mary's death, her granddaughter Lady Jane Grey briefly became queen of England, an event that Mary could never have foreseen.

Published on June 25, 2015 02:39

June 18, 2015

A 'New History' of Katherine Howard

Writers must always be prepared for the fact that not all readers will enjoy their books, or agree with the conclusions that have been reached. While this can sometimes be difficult to accept, it is in fact inevitable. Historians, in particular, must reconcile this with the fact that history is a contentious discipline. The further one goes back, the more difficult it becomes to ascertain what really happened. It becomes more challenging to discover the truth of the times about which one is writing. Facts are often few and far between, meaning that opinion more than anything else mostly holds sway.

My full length study of Queen Katherine Howard was published in the summer of 2014 and has proved to be controversial. Reviews of it thus far have been decidedly mixed. Detractors often questioned the appropriateness of the book's title: A New History. What was it about this book, they wondered, that rendered it a new history of Katherine Howard? How could it purport to be original, or innovative, or different? What new conclusions did it reach about this queen, and how did it challenge current thinking about her? Did it unsettle received opinion about her, as it had in fact hoped to do?

I believe that the title A New History is an accurate one and I would like to set out my reasoning for this. Firstly, the biography is the first full-length biography of Katherine Howard that challenges the assumption that she was an adulterous queen, that is, guilty of the charges for which she was executed in 1542. The majority of modern historians have accepted that she embarked on an adulterous relationship with Thomas Culpeper during her reign as the king's consort. Even writers who questioned whether she was technically guilty of the charges, including David Starkey and Antonia Fraser, eventually concluded that she certainly possessed intent to commit what amounted to treason, in the eyes of the law. In modern times, Professor Retha Warnicke is the only scholar to have challenged this notion, in her recent study of notorious women in Tudor England. Elisabeth Wheeler's study of ambitious male courtiers at the court of Henry VIII argued that neither Anne Boleyn nor Katherine Howard were guilty of adultery, although her work has not marketed itself as a biography of either queen. Biographies published by Lacey Baldwin Smith, Joanna Denny and David Loades have all concluded that the queen was guilty of the crimes for which she died.

Secondly, my study questioned prevailing notions about Katherine's portraiture. It should be noted that I now doubt the accuracy of my belief that the above portrait (painted circa 1540) is not of Katherine, as expressed in the biography. I raised the possibility (thus giving credence to Susan James' theory) that the portrait might depict Lady Margaret Douglas rather than Queen Katherine. Since the biography was published, however, I have rethought this idea and concluded that the miniature probably is of the queen rather than her niece-by-marriage. The portrait of an unknown woman housed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, which features on the front cover of Katherine Howard: A New History, might portray Katherine during her queenship, but I recognise that this is only a possibility. Indeed, on her website Alison Weir noted that the portrait might date to as early as 1522, which would definitively rule out Katherine as the sitter.

Thirdly, I challenged traditional beliefs about Katherine's actual character and achievements as queen. I dispelled the misleading theory that she was an empty-headed, promiscuous delinquent, and put forward evidence to suggest that she was rather more responsible, level-headed and intelligent than previously thought. However, she was young (especially given that Henry's other wives were, by the standards of the day, mature when they became queen), and might more fairly be considered to have been naive and inexperienced, rather than stupid or lacking in wit. I also indicated that her relationship with her stepdaughter Mary Tudor might have been less fraught than previously thought. Certainly, it cannot now be doubted that Katherine was an effective intercessor and sought to act as patron to her ambitious and large family.

As suggested in this blog post, there are aspects of the biography that I now disagree with. But that is the point of working in the field of history: it is constantly open to reinterpretation and historians are happy to reconsider conclusions that they previously reached. I appreciate reviews and feedback on my work. I hope, in this blog post, to have put forward a compelling argument for why I believe my biography deserves its title of A New History. In the end, the most potent reason for this is because the traditional notion of Katherine Howard as an adulterous wife must now be challenged and, at the very least, doubted. As John Weever noted in his work of 1631, like her cousin and predecessor Anne Boleyn, Katherine was most likely a victim of 'false suggestions' that reached the ears of her suspicious husband Henry VIII, who was known to have been 'unconstant in his affections'.

Published on June 18, 2015 13:16

June 4, 2015

4 June 1550: The Wedding of Robert Dudley and Amy Robsart

Above left: Lord Robert Dudley, later earl of Leicester.

Above right: Portrait of an unknown woman, c. 1550, thought by some to be Amy Robsart.

On 4 June 1550, Robert Dudley married Amy Robsart at the royal palace of Sheen. The couple were both several days short of their eighteenth birthday, Amy celebrating her birthday on 7 June and Robert celebrating his on 24 June. Amy's father had made a marriage contract on 24 May with Robert's father John Dudley, earl of Warwick and later duke of Northumberland. In it, Robsart granted his daughter and her husband an annuity of £20 per annum until they inherited the Robsart estate after his and his wife's death. Warwick obtained for his son and daughter-in-law the lands of Coxford Priory. While Warwick might have hoped for a more ambitious marriage for his son, the marriage was beneficial in that it strengthened the earl's influence in Norfolk. As Simon Adams has written, 'the two estates combined would make the couple major figures in the county'.

Born in June 1532, Amy was the daughter of Sir John Robsart and his wife Elizabeth. Her father was a Norfolk landowner and she was probably born at Stanfield Hall in Norfolk. Robert was the fifth son of John Dudley (1504?-1553), an ambitious nobleman who became earl of Warwick and later duke of Northumberland. Robert was reputed to be gifted at languages and writing and, after growing up in the court of Henry VIII, served as a companion to the teenage king Edward VI. He was handsome, charismatic, flirtatious, outspoken and charming.

Historians have conjectured that Robert and Amy probably met during the campaign against Ket's Rebellion in 1549, when the earl of Warwick and his sons stayed near Stanfield, Amy's family residence. Evidence suggests that the young couple fell in love and decided to marry in their passion for one another. William Cecil disapprovingly remarked of the union: 'Carnal marriages begin in joy and end in weeping'.

On their wedding day, the couple were honoured by the attendance of Edward VI, the twelve-year old king of England. Scarce evidence survives of their married life together. We do not know if they were happy with one another after the initial passion of their courtship. At the time of the young king's death in 1553, Robert and Amy were residing at Somerset House, the former residence of the disgraced Earl of Somerset. That year, Robert was imprisoned in the Tower of London by Mary I on account of the support he gave for Lady Jane Grey's usurpation. His father was beheaded in August 1553, but Robert was fortunate enough to escape this grisly fate. Amy is known to have visited him while he was incarcerated in the Tower. Only in 1557, with the death of her mother (her father had died in 1554) was Amy able to inherit the Robsart estate.

Above: Elizabeth I acceded to the throne in 1558.

Elizabeth's accession in 1558, however, can be viewed as effecting a turning point in the Dudleys' marriage. As is well known, Robert Dudley was an intimate favourite of the new queen, and spent considerable time at court. Amy did not accompany her husband to court following Elizabeth's accession, but spent her time at Throcking, Hertfordshire. By December 1559 she had departed for Cumnor Place, Berkshire. Nine months later, on 8 September, she was found dead at the foot of a pair of stairs. Mystery surrounds the events of her death. It is still debated today whether she was murdered, suffered an accidental death, or committed suicide. According to contemporary evidence, Amy's death caused 'grievous and dangerous suspicion, and muttering' in the country.

Above: Engraving of Cumnor Place.

On 4 June 1550, however, all of this was well in the future. Evidence suggests that Robert and Amy's marriage was a love match. Tragically, their marriage was not fated to be a long-lasting one.

Published on June 04, 2015 04:10

May 6, 2015

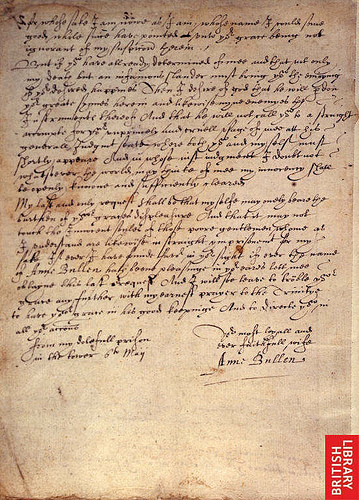

'The Lady in the Tower': Anne Boleyn's Letter to Henry VIII

On 2 May 1536, Henry VIII's second wife, Queen Anne Boleyn, was imprisoned in the Tower of London on charges of treasonable adultery and conspiracy to murder the king. Four days later, on 6 May, she is said to have written her husband a letter. This letter, which is headed 'To the King from the Lady in the Tower', has proved controversial. Historians debate whether the letter was genuinely written by the Queen, or whether it is an Elizabethan forgery. Henry Ellis referred to the letter as 'one of the finest compositions in the English language'. The letter reads as follows:

Your Grace's displeasure and my imprisonment are things so strange to me, that what to write, or what to excuse, I am altogether ignorant. Whereas you send to me (willing me to confess a truth and so obtain your favour), by such a one, whom you know to be mine ancient professed enemy; I no sooner received this message by him, than I rightly conceived your meaning; and if as you say, confessing a truth may procure my safety, I shall, with willingness and duty, perform your command.

But let not your grace ever imagine your poor wife will ever be brought to acknowledge a fault, where not so much as a thought ever proceeded. And to speak a truth, never a prince had a wife more loyal in all duty, and in all true affection, than you have ever found in Anne Bulen - with which name and place I could willingly have contented myself if God and your grace's pleasure had so been pleased. Neither did I at any time so far forget myself in my exaltation, or received queenship, but I always looked for such alteration as I now find; for the ground of my preferment being on no surer foundation than your grace's fancy, the least alteration was fit and sufficient (I knew) to draw that fancy to some other subject.

You have chosen me from a low estate to be your queen and companion, far beyond my just desert or desire; if then you found me worthy of such honour, good your grace, let not any light fancy or bad counsel of my enemies withdraw your princely favour from me, neither let that stain - that unworthy stain - of a disloyal heart toward your good grace ever cast so foul a blot on me and on the infant princess, your daughter.

Try me, good king, but let me have a lawful trial, and let not my sworn enemies sit as my accusers and as my judges; yea, let me receive an open trial, for my truth shall fear no open shames; then shall you see either mine innocency cleared, your suspicions and conscience satisfied, the ignominy and slander of the world stopped, or my guilt openly declared. So that wherever God and you may determine of, your grace may be at liberty, both before God and man, not only to execute worthy punishment on me, as an unfaithful wife, but to follow your affection already settled on that party, for whose sake I am now as I am; whose name I could some good while since, have pointed unto: Your Grace being not ignorant of my suspicions therein.

But if you have already determined of me, and that not only my death, but an infamous slander, must bring you to the enjoying of your desired happiness, then I desire of God that He will pardon your great sin herein, and likewise, my enemies, the instruments thereof, and that he will not call you to a strait account for your unprincely and cruel usage of me at his general judgement-seat, where both you and myself must shortly appear; and in whose just judgement, I doubt not (whatsoever the world think of me) mine innocency shall be openly known and sufficiently cleared.

My last and only request shall be, that myself may only bear the burden of your grace's displeasure, and that it may not touch the innocent souls of those poor gentlemen, whom, as I understand, are likewise in strait imprisonment for my sake.

If ever I have found favour in your sight - if ever the name of Anne Bulen have been pleasing in your ears - then let me obtain this request; and so I will leave to trouble your grace no further: with mine earnest prayers to the Trinity to have your grace in his good keeping, and to direct you in all your actions.

From my doleful prison in the Tower, the 6th of May.

Ann Bulen

The letter is haunting, emotional and powerful: it bristles with indignation and is dominated by the writer's pleas of innocence. Most striking of all is the writer's dignified tone. Yet was the letter actually written by Queen Anne while imprisoned in the Tower? The majority of modern historians are convinced that it is a forgery. Eric Ives, Retha Warnicke and G.W. Bernard, the three most respected biographers of Anne, all dismiss the letter. Ives notes: 'its elegance has always inspired suspicion'. Professor David Starkey, Antonia Fraser and David Loades failed to even discuss the letter in their histories of Anne, almost certainly because they too subscribed to the view that it is a forgery, and was not genuinely written by the Queen.

The letter was first published in Lord Herbert's The Life and Raigne of King Henry the Eighth (1649), and then by Bishop Burnet thirty years later. In his The History of the Reformation of the Church of England (1679), Burnet noted that the imprisoned Queen made 'deep protestations of her innocence, and begged to see the King, but that was not to be expected'. Burnet found the letter with Sir William Kingston's letters among the papers of Cromwell. Other early modern historians included references to the letter in their works, including John Strype, Bishop White Kennett, and Sir Henry Ellis. As Sandra Vasoli notes, several versions of the letter survive. Yet none of them are written in Anne's handwriting as recognised from her extant letters.

This is, in fact, the main argument in favour of the letter being a forgery. Against that it can be noted that one's handwriting changes over the course of one's lifetime; the letters we have written by Anne were written in her youth. Secondly, the letter may have been dictated by the Queen to a servant or maid. James Gairdner, however, believed that the letter was written in an Elizabethan hand. Alternatively, Jasper Ridley dismissed this argument by noting that the letter 'bears all the marks of Anne's character, of her spirit, her impudence and her recklessness'.

Alison Weir, concluding that the letter is most likely a forgery, referred to other anomalies which call into question the view that the letter was genuinely penned by Anne: the writer signs herself as 'Ann Bulen' rather than 'Anne the Queen' or 'Anne Boleyn'; Cromwell kept the letter, rather than destroying it; the heading at the top is unusual ('To the King from the Lady in the Tower' - why not refer to Anne as 'the Queen' or 'Anne'?); and, perhaps most importantly, the reproving tone and bold attitude towards the king, in which the writer admonishes him for instigating a plot in order to be free of her to wed Jane Seymour.

Other writers have doubted the genuineness of the letter. Gareth Russell noted the 'psychological inconsistencies' in the letter, in which the writer refers to herself as being chosen from 'a low estate to be your queen': yet Anne was hardly from 'a low estate', she was well-connected. While it is a myth that she was the most noble of Henry VIII's English-born wives, she was related to the Howard dukes of Norfolk (her mother was a Howard), her father was heir presumptive to the earldom of Ormond at the time of her birth, and she could trace her descent from King Edward III.

Another difficulty is the writer's claim that Anne's rise to queenship had 'no surer foundation than your grace's fancy', which is problematic when other evidence is considered. As Warnicke notes, the Queen genuinely believed that God had selected her to become Henry's wife, and she was fond of informing visitors at court of this. Alternatively, as Marie Louise Bruce stated in her biography of Anne, she had a tendency to express herself in hyperbole and it is therefore possible that she was resorting to the use of hyperbole or, alternatively, was flattering her husband's ego at a time of danger. Interestingly, there is but one reference to Anne's daughter Elizabeth: however, this is consistent with Anne's silence about her daughter while imprisoned in the Tower, perhaps because she was hoping not to worsen the consequences of her fall for Elizabeth that were, already, looking bleak.

One way or another, it will never be known with certainty whether the letter from 'The Lady in the Tower' was genuinely written by Anne Boleyn or not. I personally believe that she may have written it. Although it is strange that Anne refers to herself as 'Ann Bulen' and there are problematic assertions in relation to her relationship with the king and her rise to queenship, I believe the emotional tone of the letter, which wavers between desperation, dignity, resolution and indignation, is consistent with what we know of the Queen's behaviour in the Tower. Her moods oscillated between despair and joy, sorrow and hysteria, panic and calmness, resignation and hope. It is entirely possible that the Queen either wrote - or dictated to someone serving her - this passionate, dignified letter.

As Vasoli notes, however, the letter never reached Henry VIII. He was not to be swayed in his decision to be rid of Anne. Nine days after the letter was supposedly written, the Queen was found guilty of the crimes with which she was charged, and four days later she went to the scaffold. Anne refused to admit her guilt on the scaffold. She admitted that she had been condemned by the law, but she did not admit to betraying the king. During her trial she pleaded her innocence and sought mercy. Her pleas of innocence are consistent with those that recur in the letter of May 6.

Published on May 06, 2015 06:15

April 27, 2015

Herstory and the Explosion of Interest in England's Ruling Women

In recent years, there has been an explosion of interest in the lives of England's medieval and early modern queens. Popular historians in particular have become fascinated by the extraordinary lives of these women. The majority of attention has focused on the late Middle Ages and the Tudor era. Countless books are published every year detailing the lives of these magnetic, captivating women.

What is to account for these trends? What makes one woman particularly fascinating to biographers, at any point in time? Where does the desire to recover her history - 'herstory', as it has been termed - come from? Why are we so fascinated by these women, and why are readers lapping up biographies of medieval queens like there's no tomorrow?

The simple answer is because their lives are interesting in and of themselves. The more complex answer is because their lives were forgotten for centuries, swept away as if they had never existed. These women, even queens, were confined to the footnotes of history, dismissed in a sentence and remembered only if they contributed to their husband's achievements. If they were not forgotten, they were misrepresented. They were slandered, their names dragged through the mud. Consider the infamous tale of Eleanor of Aquitaine, in a fit of jealous rage, murdering her beautiful rival Rosamund Clifford by poison. Or the story of Elizabeth Wydeville and her mother greedily extorting their rights to queen's gold. Or the legend of Isabella of Angouleme living in open adultery with her lovers, causing her vicious husband King John to brutally murder them in revolting fashion.

If these women were not condemned, they were sanctified in hagiographical works. They were celebrated as passive beings who caused no trouble, satisfying the whims of their husbands and living quietly and gently. Jane Seymour was idealised as a pious, motherly wife who provided Henry VIII with his heart's desire. Anne of Bohemia is remembered only for her gracious acts of intercession. For centuries, Katherine of Aragon was viewed as nothing short of a saint, the very embodiment of virtuous womanhood.

In more recent times, we as historians have become aware of how simplistic and misleading these characterisations are. We recognise that these women were complex beings; they were human. They were neither saints nor sinners, neither whores nor angels. We seek to uncover their stories respectfully, admiring their achievements, celebrating their lives and respecting their decisions. In short, historians are taking advantage of developments in the study of history to present these women more truthfully than ever before.

As a biographer of Katherine Howard, with a keen interest in the lives of medieval and early modern women, I eagerly await new studies. Having spent a number of years researching Katherine (and I continue to hope to devote more time to her life), I anticipate with pleasure upcoming biographies of her by Gareth Russell and Josephine Wilkinson. Katherine was, for centuries, the most neglected of Henry VIII's queens. Historians were not particularly interested in her. Lacey Baldwin Smith's biography of Katherine, published in 1961, remained the standard work for decades. There have since been only three published biographies of Katherine: Joanna Denny's of 2005; David Loades' of 2012; and my own.

I am not sure why historians are suddenly interested in Katherine. Perhaps they are more aware than ever of how inadequate most of the studies about her have been. Perhaps, in the light of the rehabilitation of Anne Boleyn's reputation, and the publication of impressive studies detailing the considerable achievements of Katherine of Aragon and Katherine Parr, it has been acknowledged that Katherine Howard deserves to be better known and celebrated for her own achievements. New found interest in her is surely to be welcomed.

Yet other women deserve the attention of historians, for they remain forgotten. If they are remembered, it is mostly negatively. Isabella of Angouleme, Isabella of France, and Margaret of Anjou are three powerful, well known women who continue to be misrepresented and slandered, their lives distorted. Jacquetta of Luxembourg, mother of Queen Elizabeth Wydeville, was an acknowledged woman in her own lifetime, and yet there has been no biography of her. Philippa of Hainault, Joan of Navarre and Catherine de Valois are queens of England that have still not acquired biographies in their own right. There has been exceptionally little attention given to Isabel Neville, elder sister of Queen Anne. Nor has there been for other highborn women in England who were not queens of England, but were nonetheless important. Alice Perrers, Katherine Swynford and Elizabeth Shore are women who deserve to be re-examined.

The expansion of 'herstories' is an immensely positive achievement. Let us hope the field continues to expand and develop. We need to learn more about these incredible women. We should endeavour to reinterpret their lives and re-examine the myths about them. Celebrating their achievements and respecting their experiences is essential to uncovering the full story of English history.

Published on April 27, 2015 13:38

April 16, 2015

Edward II and Isabella of France

The relationship between King Edward II and his wife Isabella of France is almost always depicted in negative terms. In Derek Jarman's film Edward II (1991), Tilda Swinton offers a sexually frustrated, ambitious Isabella who turns against her ineffectual husband and usurps his throne. In Mel Gibson's Braveheart (1995), Isabella enjoys a romantic affair with the Scottish landowner and hero William Wallace, perhaps because she experiences frustration and dismay with her husband Edward. The film even suggests that Wallace is the father of her son Prince Edward, despite the fact that Wallace died in 1305, three years before Isabella arrived in England and seven years before the birth of the prince. Biographers of Isabella have tended to characterise the queen as a passive victim of her cruel and merciless husband. She apparently was humiliated, hurt and shamed by his homosexual relationships. She was neglected at court and was mistreated by her husband's courtiers. Finally, her husband seized her children from her and took hold of all of her estates, lands and possessions. He probably allowed his lover Hugh Despenser to violate her. The long-suffering Isabella, who by now had had enough, departed for France alongside her lover Roger Mortimer and arrived back in England with foreign aid. The citizens of England, who loathed their king as much as she did, willingly rallied to her side, and together they marched through the country. Edward was removed from the throne and the popular Isabella achieved a resounding victory. Her son Edward was crowned Edward III and Isabella was celebrated forever after as a liberator.

However, the real story is not as simple as this version would like to make out. This version reduces Edward and Isabella to simplistic and unconvincing cardboard caricatures: Edward as a sexually depraved bully and Isabella as a passive, humiliated victim. This does no justice to the real people. King Edward and his queen actually enjoyed a close, supportive relationship for most of their lives together. They had four children with one another, and frequently departed for France on peace missions, where contemporaries, including Geoffrey of Paris in 1313, noted their love and respect for one another. Isabella sought her husband's support and assistance in her household governance, which he readily gave. Edward was so impressed with his young wife's success in the sphere of her household that he awarded her with possession of the great seal on two occasions, in 1319 and 1321, which greatly honoured the queen and confirmed his trust in her abilities.

Isabella was happy enough to approach Edward when she sought to intercede on behalf of individuals. The administrative documents at the National Archives are full of references to her seeking pardons from the king for those whom she felt to be oppressed and in need of assistance. Edward made sure his wife enjoyed a splendid household and she was afforded every dignity as queen. It is actually uncertain, contrary to popular belief, how she felt about Piers Gaveston, her husband's favourite and, possibly, lover, but it does not seem her relations with Gaveston were as hostile as is often believed. She assisted him financially in 1311 before his exile from England, and she sheltered some of his supporters in her household. There is no evidence of how Isabella personally felt about him.

The relationship between the royal couple did become more strained in the mid-1320s, probably because of Hugh Despenser's malign influence. He seems to have begun a concerted campaign of poisoning the king's mind against his wife, perhaps because he was attempting to replace her in Edward's counsels. In September 1324, the king seized all of Isabella's estates and lands. Yet this does not mean that Isabella gradually came to hate and despise her husband. On the contrary, when she was abroad a year or so later, she continually reiterated her desire to return to Edward, because she loved him and wished to obey his wishes. However, she felt that she could not do so on account of the enmity of Despenser and his father. She believed that her very life would be endangered if she returned to the country. Isabella also sought to protect her son Prince Edward's inheritance, who was with her in France: rumours were circulating at this point that he would be disinherited and not allowed to succeed to the throne on account of his refusal to return to England.

The evidence credibly suggests that Isabella loved her husband and longed to return to him, but could not do so on account of the malicious Despensers, who enjoyed the king's influence and protection. Edward came to view his wife as disobedient and treacherous, for he was unable to appreciate the danger she faced. Their marriage fell into ruin and they were never able to experience the happiness which they had enjoyed in each other's company for such a long period. Whether Edward was murdered in the autumn of 1327, or whether he died at a later date as an obscure pilgrim in Europe, Isabella certainly continued to honour his memory and, when she died in 1358, she chose to be buried with his heart. The relationship between Edward and Isabella was not one of abuse, hatred and murder. It was, for fifteen years, a loving, stable and supportive union. The royal couple were frequently in one another's company and were parents to four children. Contemporaries commented on their love for one another. Yet the malign influence of the Despensers and Edward's growing tyranny destroyed their once happy marriage.

Published on April 16, 2015 06:31

April 2, 2015

The Death of Arthur, Prince of Wales

[image error]

Above: Arthur Tudor, Prince of Wales.

Arthur Tudor, born in 1486, had been groomed from birth for a glorious future as king of England. Arthur would have known that, when his illustrious father Henry VII died, he would succeed to the throne as King Arthur I. He had been named after the heroic king of legend, 'in honour of the British race', while confirming the Tudors' mythical descent from King Arthur. However, England was not to experience a king named Arthur I. On 2 April 1502, aged only fifteen, Arthur Prince of Wales died at Ludlow Castle,

Arthur's death left his young wife, Katherine of Aragon, a widow aged only sixteen. The marriage of the Prince of Wales had been discussed as early as 1488, and on 27 March 1489 the Treaty of Medina del Campo was signed, in which the marriage of Arthur and Katherine was provided for when they came of age. At Woodstock in 1497, a proxy betrothal took place, and two proxy marriages followed in 1499 and 1500. Finally, in late 1501, Katherine arrived in England and was married to Arthur on 14 November at St. Paul's Cathedral in a lavish ceremony. Celebrations went on for days as the capital rejoiced at the marriage of its future rulers. Soon afterwards, the Prince and Princess of Wales departed for the marches of Wales. They resided at Ludlow Castle. There had been some uncertainty as to whether the royal couple should immediately live together. Henry VII believed that his son was not old or mature enough to fulfil 'the duties of a husband', and he wrote to the Spanish monarchs explaining that his son's 'tender age' prevented cohabitation with Katherine. King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella agreed that the couple should not live together for some time, although Henry VII eventually decided that Katherine should accompany her husband to Wales.

Above: Ludlow Castle.

In the spring of 1502, however, according to the King's Printer Richard Grafton, 'there suddenly came a lamentable loss and mischance to the king, the queen and all the people'. The Receyt of the Lady Kateryne recorded that, 'from the Feast of the Nativity of Christ unto the solemn feast of the Resurrection, at the which season grew and increased upon his body, whether it was by surfeit or cause natural, a lamentable and most pitiful disease and sickness'. It is uncertain what it was that struck Arthur. Writers have suggested plague, tuberculosis, the sweating sickness, influenza, or testicular cancer. In her recent biography of Elizabeth of York, Alison Weir concludes that it was probably tuberculosis which killed Arthur. Whatever it was, on the morning of 2 April, the prince died, commending 'with most fervent devotion his spirit and soul to the pleasure and hands of Almighty God'.

Arthur's death was met with shock, dismay and grief at court. Henry VII, devastated, sent for his wife in his hour of need: 'When the King understood these sorrowful, heavy tidings, he sent for the Queen, saying that he and his wife would take their powerful sorrow'. Indeed, the occasion of their son's death brought the royal couple together and provides evidence of their close, loving relationship. Queen Elizabeth comforted her husband: 'After she was come and saw the King her lord in that natural and painful sorrow, she, with full great and constant and comfortable words, besought his Grace that he would first, after God, consider the weal of his own noble person, of the comfort of his realm, and of her'. She reminded him that they were both young and could have more children. They still had a healthy son, Henry, then aged ten, who was now heir to the throne. The king, cheered by her words, thanked her for 'her good comfort'. However, when the queen departed to her own rooms, she collapsed with grief and sorrow. The king was sent for, it now being his turn to comfort and console his devastated wife.

Above: Katherine of Aragon, Princess of Wales and, later, Queen of England.

We can only wonder how different the history of England might have been had Arthur survived and succeeded to the throne following his father's death. Given that Henry VII was to die in 1509, Arthur would have been twenty-two years of age when he became king of England. Would he and Katherine have had several children by then? Would the English succession have already been assured well before Arthur became king? What would have happened to his brother, Henry? We can but speculate. Yet, as Rosemary Horrox notes: 'With the benefit of hindsight the most important consequence of Arthur's early death was the remarriage of his widow to the prince's younger brother, the future Henry VIII, and the controversy to which that later gave rise concerning the consummation or otherwise of Katherine's first marriage'.

Above: Arthur Tudor, Prince of Wales.

Arthur Tudor, born in 1486, had been groomed from birth for a glorious future as king of England. Arthur would have known that, when his illustrious father Henry VII died, he would succeed to the throne as King Arthur I. He had been named after the heroic king of legend, 'in honour of the British race', while confirming the Tudors' mythical descent from King Arthur. However, England was not to experience a king named Arthur I. On 2 April 1502, aged only fifteen, Arthur Prince of Wales died at Ludlow Castle,

Arthur's death left his young wife, Katherine of Aragon, a widow aged only sixteen. The marriage of the Prince of Wales had been discussed as early as 1488, and on 27 March 1489 the Treaty of Medina del Campo was signed, in which the marriage of Arthur and Katherine was provided for when they came of age. At Woodstock in 1497, a proxy betrothal took place, and two proxy marriages followed in 1499 and 1500. Finally, in late 1501, Katherine arrived in England and was married to Arthur on 14 November at St. Paul's Cathedral in a lavish ceremony. Celebrations went on for days as the capital rejoiced at the marriage of its future rulers. Soon afterwards, the Prince and Princess of Wales departed for the marches of Wales. They resided at Ludlow Castle. There had been some uncertainty as to whether the royal couple should immediately live together. Henry VII believed that his son was not old or mature enough to fulfil 'the duties of a husband', and he wrote to the Spanish monarchs explaining that his son's 'tender age' prevented cohabitation with Katherine. King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella agreed that the couple should not live together for some time, although Henry VII eventually decided that Katherine should accompany her husband to Wales.

Above: Ludlow Castle.

In the spring of 1502, however, according to the King's Printer Richard Grafton, 'there suddenly came a lamentable loss and mischance to the king, the queen and all the people'. The Receyt of the Lady Kateryne recorded that, 'from the Feast of the Nativity of Christ unto the solemn feast of the Resurrection, at the which season grew and increased upon his body, whether it was by surfeit or cause natural, a lamentable and most pitiful disease and sickness'. It is uncertain what it was that struck Arthur. Writers have suggested plague, tuberculosis, the sweating sickness, influenza, or testicular cancer. In her recent biography of Elizabeth of York, Alison Weir concludes that it was probably tuberculosis which killed Arthur. Whatever it was, on the morning of 2 April, the prince died, commending 'with most fervent devotion his spirit and soul to the pleasure and hands of Almighty God'.

Arthur's death was met with shock, dismay and grief at court. Henry VII, devastated, sent for his wife in his hour of need: 'When the King understood these sorrowful, heavy tidings, he sent for the Queen, saying that he and his wife would take their powerful sorrow'. Indeed, the occasion of their son's death brought the royal couple together and provides evidence of their close, loving relationship. Queen Elizabeth comforted her husband: 'After she was come and saw the King her lord in that natural and painful sorrow, she, with full great and constant and comfortable words, besought his Grace that he would first, after God, consider the weal of his own noble person, of the comfort of his realm, and of her'. She reminded him that they were both young and could have more children. They still had a healthy son, Henry, then aged ten, who was now heir to the throne. The king, cheered by her words, thanked her for 'her good comfort'. However, when the queen departed to her own rooms, she collapsed with grief and sorrow. The king was sent for, it now being his turn to comfort and console his devastated wife.

Above: Katherine of Aragon, Princess of Wales and, later, Queen of England.

We can only wonder how different the history of England might have been had Arthur survived and succeeded to the throne following his father's death. Given that Henry VII was to die in 1509, Arthur would have been twenty-two years of age when he became king of England. Would he and Katherine have had several children by then? Would the English succession have already been assured well before Arthur became king? What would have happened to his brother, Henry? We can but speculate. Yet, as Rosemary Horrox notes: 'With the benefit of hindsight the most important consequence of Arthur's early death was the remarriage of his widow to the prince's younger brother, the future Henry VIII, and the controversy to which that later gave rise concerning the consummation or otherwise of Katherine's first marriage'.

Published on April 02, 2015 02:36

March 23, 2015

23 March 1430: The Birth of Margaret of Anjou, Queen of England

Above: Queen Margaret of Anjou.

On this day in history, 23 March 1430, Margaret of Anjou was born at Pont-a-Mousson in Lorraine to Rene of Anjou and his wife Isabella, duchess of Lorraine. Rene was titular king of Naples, Jerusalem, and Aragon, and duke of Anjou, Bar, Lorraine, count of Provence and count of Piedmont. Despite his claims to many kingdoms, Rene was unfavourably known as 'a man of many crowns but no kingdoms'. Margaret was the couple's fourth child and second daughter, and spent her childhood at the beautiful castle of Tarascon in southern France and in the old royal palace at Capua, near Naples. Contemporary observers described her in her youth as beautiful, dignified and graceful.

In April 1445, at the age of fifteen, Margaret married Henry VI of England and became England's queen. The marriage sought to achieve peace between the warring kingdoms of England and France, with the hope being to bring to a conclusion the brutal conflict known as the Hundred Years War. Although Margaret symbolised hopes of peace and prosperity, the marriage was not popular in England, for the bride brought no dowry, while the cessation of Anjou and Maine to Margaret's father and the king of France caused outrage and dismay. Margaret has traditionally been interpreted by historians as a cunning and avaricious meddler in politics, responsible for urging her husband to cede the kingdoms to the French, but Helen Maurer's careful research has called into question this view. Given that Margaret was only in her teenage years, in a strange land, when Anjou and Maine were ceded, it does seem unlikely that she was responsible for what took place.

Margaret's position would have been secured early on had she given birth to a son with which to secure the succession, but this was only accomplished eight years after her marriage, when her son Edward was born in October 1453. His birth could not have occurred at a worse time: several months earlier, Henry VI suffered a complete breakdown and was thought to have gone insane. He may have been suffering from a form of schizophrenia. Margaret's position became uncertain as the government fell into crisis. She did not become regent and, contrary to popular belief, did not espouse an aggressive stance towards the duke of York, who became Protector at this time. Indeed, she appears to have been content to cooperate with him and was on good terms with his wife, Cecily Neville.

Above: Henry VI.

Margaret has tended to be characterised negatively as a vengeful, aggressive, merciless and cruel woman who was responsible for the outbreak of the Wars of the Roses by virtue of her partisan favour of the earl of Suffolk and the Duke of Somerset. She is often interpreted as the leader of a court party that was corrupt, decadent and wasteful, causing damage to the kingdom and tensions in society at large. This unfair portrayal of the queen has been encouraged by Shakespeare's portrayal of her as a she-wolf. The real Margaret of Anjou was almost certainly not the evil villain of legend. She was a pragmatic, intelligent and courageous woman who fought ardently to protect her son's inheritance and to safeguard her husband's position as king. It was hardly her fault that she was married to a weak and inept king unable to control factional discontent or rule with a steady hand. Margaret's attempt to provide strong governance caused anger and dismay, given that her role in English politics threatened to unsettle the established gender order. However, with the benefit of hindsight, we can appreciate the impossible situation Margaret found herself in, and admire her brave attempts to restore her deposed husband to the throne. She was not a she-wolf, but neither was she a saint. Rather, she is someone to be admired, respected and appreciated for her courage, pragmatism and devotion to her husband and son.

Published on March 23, 2015 08:19