Conor Byrne's Blog, page 10

October 24, 2014

24 October 1537: Death of Jane Seymour

[image error]

On 24 October 1537, Queen Jane Seymour died at Hampton Court Palace, aged around twenty-nine. The third wife of Henry VIII had given birth to a male heir, Prince Edward, twelve days previously, and had been thought to have been in good health following her first birth. The queen had welcomed visitors attending her son's christening on 15 October, although following protocol, neither she nor her husband attended the christening.

Jane's queenship appears to have been passive, in contrast with the strong and authoritative queenships of her two predecessors Katherine of Aragon and Anne Boleyn, but as historians have conjectured, this may well have resulted from Henry's decision to limit his wife's influence. Jane did not lead religious reform or press for a return to traditional religion: she appears to have been conservative in her religious beliefs, since Martin Luther heard that she was 'an enemy of the gospel'.

Although the birth of the prince was arduous and difficult, there is no evidence that the queen gave birth by caesarean section, a story put forward by the Catholic priest Nicholas Sander in his work defaming Henry VIII's reformation. Jane appeared to have been making a normal recovery following the birth of her son. She initially rallied after some initial consternation about her condition, but by 24 October her life was in danger and her almoner, Robert Aldrich, bishop of Carlisle, administered extreme unction and informed the king. Although the queen's attendants were blamed for allowing her to eat food that was unsuitable and allowing her to catch a cold, it seems likely that Jane developed puerperal fever, a common condition that befell many sixteenth-century women. Alternatively, it has been suggested that the queen died because of retention of parts of the placenta in her uterus, which could have led to a catastrophic haemorrhage a few days after her child's delivery.

Whatever her condition was, Jane soon developed septicaemia, and delirium set in. She died just before midnight on 24 October, less than two weeks after the birth of Prince Edward. She was either twenty-eight or twenty-nine years of age at the time of her decease, young even by sixteenth-century standards. Her husband the king was devastated, informing the king of France: 'Divine Providence has mingled my joy [at the birth of his son] with the bitterness of the death of her who brought me this happiness'. From then on, Henry VIII would fondly remember Jane Seymour as his favourite wife, the only consort, as it turned out, who provided him with a surviving male heir. He would be buried beside Jane in St George's Chapel, Windsor, when he died in 1547.

On 24 October 1537, Queen Jane Seymour died at Hampton Court Palace, aged around twenty-nine. The third wife of Henry VIII had given birth to a male heir, Prince Edward, twelve days previously, and had been thought to have been in good health following her first birth. The queen had welcomed visitors attending her son's christening on 15 October, although following protocol, neither she nor her husband attended the christening.

Jane's queenship appears to have been passive, in contrast with the strong and authoritative queenships of her two predecessors Katherine of Aragon and Anne Boleyn, but as historians have conjectured, this may well have resulted from Henry's decision to limit his wife's influence. Jane did not lead religious reform or press for a return to traditional religion: she appears to have been conservative in her religious beliefs, since Martin Luther heard that she was 'an enemy of the gospel'.

Although the birth of the prince was arduous and difficult, there is no evidence that the queen gave birth by caesarean section, a story put forward by the Catholic priest Nicholas Sander in his work defaming Henry VIII's reformation. Jane appeared to have been making a normal recovery following the birth of her son. She initially rallied after some initial consternation about her condition, but by 24 October her life was in danger and her almoner, Robert Aldrich, bishop of Carlisle, administered extreme unction and informed the king. Although the queen's attendants were blamed for allowing her to eat food that was unsuitable and allowing her to catch a cold, it seems likely that Jane developed puerperal fever, a common condition that befell many sixteenth-century women. Alternatively, it has been suggested that the queen died because of retention of parts of the placenta in her uterus, which could have led to a catastrophic haemorrhage a few days after her child's delivery.

Whatever her condition was, Jane soon developed septicaemia, and delirium set in. She died just before midnight on 24 October, less than two weeks after the birth of Prince Edward. She was either twenty-eight or twenty-nine years of age at the time of her decease, young even by sixteenth-century standards. Her husband the king was devastated, informing the king of France: 'Divine Providence has mingled my joy [at the birth of his son] with the bitterness of the death of her who brought me this happiness'. From then on, Henry VIII would fondly remember Jane Seymour as his favourite wife, the only consort, as it turned out, who provided him with a surviving male heir. He would be buried beside Jane in St George's Chapel, Windsor, when he died in 1547.

Published on October 24, 2014 07:42

October 18, 2014

Christine de Pizan: A Remarkable Woman

The fourteenth-century was, in many respects, a century of remarkable women. Christine de Pizan was one of them, and her name continues to resonate today with connotations of learning, chivalry and courtliness. Born in 1365, Christine was a French Renaissance writer who, some have argued, wrote some of the first feminist works of literature, although it seems somewhat anachronistic to label them as such. Christine was remarkably educated and this allowed her to write, becoming what King's College termed 'the first woman in Europe to successfully make a living through writing'.

Born in Italy in 1365, Christine later departed for France at a young age when her father, Thomas de Pizan, was appointed to the position of astrologer to the French king at that time, Charles V. This atmosphere allowed his daughter to pursue her intellectual interests, for Thomas clearly believed that his daughter should enjoy a fine education. At the age of fifteen, in 1380 Christine married Etienne du Castel, a royal secretary at court, with whom she had three children (a daughter, a son, and another child who tragically died in childhood). In 1390, her husband sadly died in an epidemic, meaning that, on his death, Christine had to support her mother, her niece, and two small children. As a means of supporting herself and her family, she devoted herself to writing. By 1393 she had attracted attention for her love ballads, and between 1399 and 1412 she is said to have composed over three hundred ballads, as well as many shorter poems.

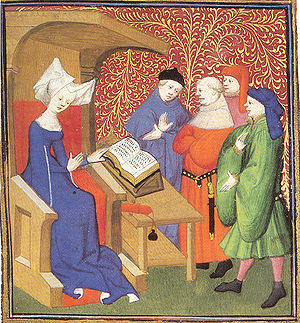

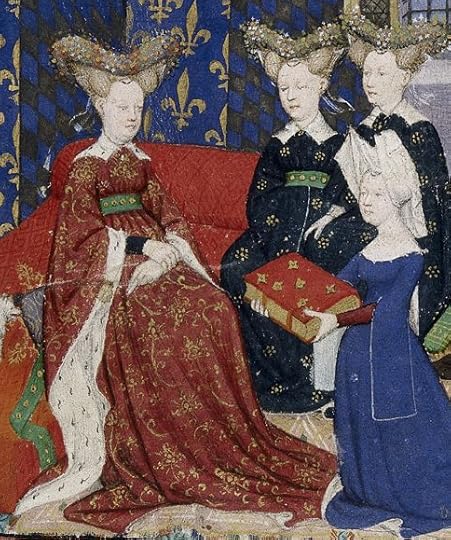

Above: Christine de Pizan presents her book to the queen of France, Isabeau of Bavaria.

In 1401-2, Christine participated in a literary debate that allowed her to move beyond the courtly circles she had up to that moment moved in. Following this, she became involved in a renowned literary controversy known as the 'Querelle du Roman de la Rose', which she helped to instigate by calling into question the literary merits of Jean de Meun's Romance of the Rose, a medieval French poem that satirised and entertained about the Art of Love. Its focus on sensual language and imagery caused particular controversy, leading to individuals, including Christine, to question it. She, in particular, condemned its suggestion that women were little more than seducers. Christine began to counter and oppose literary treatments of women that were negative or even abusive.

Christine was, and remains, best known for her vernacular works, both in prose and in verse. These include political treatises and mirrors for princes, which consequently brought her a great deal of attention from the very highest orders. Her most famous literary works, The Book of the City of Ladies (in which she created a symbolic city in which women are both appreciated and defended) and The Treasure of the City of Ladies, were both published in 1405. They both offered positive representations of women, stressing how to cultivate useful feminine qualities and celebrating women's past contributions to society. Christine emphasised that women should seek to bring about peace between people, while arguing that slanderous speech eroded one's honour. Christine also later wrote a poem eulogising the tragic Joan of Arc, burned at the stake at the age of nineteen. She died in 1430 aged sixty-five or sixty-six.

Above: A scene from The Book of the City of Ladies (1405).

Christine de Pizan was not a medieval feminist. However, she was remarkable in that, as Simone de Beauvoir wrote in 1949, her work was 'the first time we see a woman take up her pen in defence of her sex'. Historians have debated whether this period saw a 'golden age' for women that was tantalisingly brief but which afforded women splendid opportunities not experienced before. While this remains uncertain, Christine de Pizan's astonishing life demonstrates the opportunities for women of the upper orders in particular, who, mobilised by their education and status, could achieve incredible feats.

Published on October 18, 2014 06:21

October 12, 2014

12 October 1537: The Birth of Edward VI

On this day in history, 12 October 1537, at two a.m. the future king Edward VI was born at Hampton Court Palace. Hugh Latimer, bishop of Worcester, greeted the news of the birth of the prince with joy, 'whom we hungered for so long'. The country at large shared his joy, and there were glorious celebrations across England. Edward was the only child of Henry VIII by his third wife, Jane Seymour. After twenty-eight years on the throne, Henry VIII finally had a male heir, and he had reason to believe that the Tudor succession was finally secure after years of uncertainty, bloodshed and religious revolution.

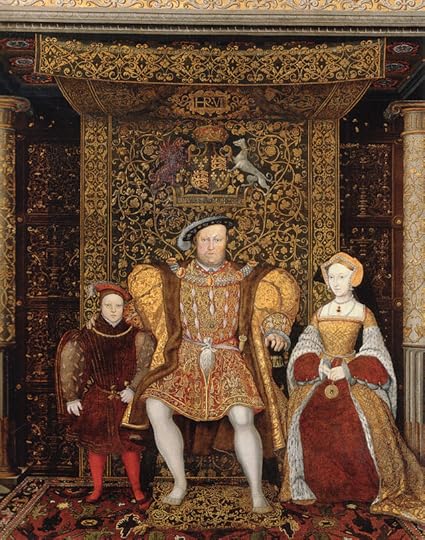

Above: Edward's parents, Henry VIII of England and his third wife Jane Seymour.

The queen's birth had been difficult, lasting two days and three nights. Three days after the birth, the prince was christened, although, as was the custom, neither the king nor his wife attended. Contrary to popular belief, Queen Jane seems to have recovered quickly, and was soon up writing letters and receiving visitors. However, the queen soon contracted an infection and she died nine days after the birth, aged twenty-nine. The king's euphoria and relief turned to sorrow at the loss of his dear consort.

It cannot be overstated how relieved the king was at the birth of his son. When he had married Katherine of Aragon, his first wife, in 1509, he would surely not have foreseen that it would be almost thirty years before his much-desired son was born. This isn't completely true, for Katherine had given birth to three sons: Prince Henry, who lived for fifty-two days before dying in February 1511; a son in the autumn of 1513; and a son the following year, both of whom died. Katherine's marriage was annulled largely because it did not provide a male heir, and Henry married her attendant Anne Boleyn in 1533. Although Queen Anne gave birth to arguably England's greatest monarch, the future Elizabeth I, that year, she too, as with her predecessor, did not give birth to a living son. Most tragically, in January 1536 she gave birth to a stillborn son. Four months later, she was decapitated for treason.

When Henry VIII married Jane in May 1536, he was almost forty-five, and from his point of view the succession was no more secure than it had been at his accession twenty-seven years earlier (although his previous wives had both given birth to a daughter). There is evidence that, when the new queen failed to conceive soon after her marriage, the king began voicing his doubts. Luckily for Jane, in early 1537 she became pregnant. Her condition was visible throughout the summer of 1537 and in September she arrived at Hampton Court for her lying-in where, a month later, she gave birth to a prince who, unlike those born to Katherine or Anne, survived.

Above: Henry VIII with his son, Edward (left), and third wife Jane (right), c. 1545. In reality, Jane had been dead for eight years when this painting was completed. The king was, at the time, married to his sixth and final wife, Katherine Parr. The painting has been interpreted as a brilliant work of Tudor propaganda.

Published on October 12, 2014 02:45

September 25, 2014

The Eternally Beautiful Anne Boleyn

[image error]

[image error]If your knowledge of Tudor history was gained from the Showtime television series The Tudors (2007-10), the profoundly successful novel The Other Boleyn Girl by Philippa Gregory, or the 2008 Hollywood adaptation of that novel starring Natalie Portman and Scarlett Johansson, your lasting impression would most likely be that Anne Boleyn was a stunningly beautiful young woman. A woman with dazzling dark eyes, long brown hair, creamy skin and rosebud lips; a woman who epitomised charm, elegance and dressed superbly. A woman who turned heads wherever she went, and who captured men's hearts with ease.

Popular culture, as Susan Bordo notes in her study of Anne, tends to present Anne as a drop-dead-gorgeous creation who captivated Henry VIII the minute he laid eyes on her, solely because of her physical appearance. In The Tudors, for example, Natalie Dormer plays a stunningly attractive Anne who captures the king's heart when they meet at the Chateau Vert pageant in early 1522. From that moment on, all he can think about is Anne. Similarly, in the novel The Other Boleyn Girl, Philippa Gregory introduces a beautiful Anne, who coldly and ruthlessly manipulates besotted male suitors to fulfil her every whim. But, popular culture aside, how accurate are these interpretations of Anne Boleyn's physical appearance? More pertinently, what do these claims and ideas suggest about prevailing ideas about female attractiveness and whether or not a person's appeal is rooted in their physical looks?

Above: The Tudors. Natalie Dormer introduced a stunningly beautiful Anne.

Henry VIII's second wife was, contrary to popular belief, not a great beauty. To be sure, we lack contemporary portraits of her, because in the wake of her disgrace and death in 1536, Henry VIII ruthlessly and efficiently destroyed everything he could find to do with her, including portraits of his once beloved queen. We therefore have very little knowledge about what Anne Boleyn actually looked like. There are some things we do, however, know about her appearance, relying on contemporary reports without taking their obvious biases and polarising viewpoints at face value.

The Venetian ambassador, who met Anne in the late 1520s, recorded that the king's new love was:

'Not one of the handsomest women in the world; she is of middling stature, swarthy complexion, long neck, wide mouth, a bosom not much raised and eyes which are black and beautiful'.

To this ambassador, then, with the exception of her 'beautiful' dark eyes, Anne Boleyn was very average in her physical appearance. His description conveys someone not particularly impressed or swept off his feet.

Others, however, were more praiseworthy about Anne's looks. Lancelot de Carles, a Frenchman who wrote a poem detailing her disgrace in 1536, remarked that she was 'beautiful', with 'an elegant figure'. John Barlow, a cleric of Anne, recorded that she was 'reasonably good looking' - again, not a dazzling beauty, but attractive enough. George Wyatt, the grandson of Thomas Wyatt (who some suspect was Anne's admirer), admitted that her colouring was 'not so whitely' as then admired, and she had several 'small moles... upon certain parts of her body'. He also stated that she had an extra nail on one hand.

The most notorious description of Anne's physical appearance, however, came from the man who did the most to blacken her name: Nicholas Sander, a Catholic recusant writing in the reign of her daughter Elizabeth I. Viewing Anne as a bewitching temptress and witch who had craftily ensnared Henry VIII into marriage, encouraging him to commit heresy by breaking away from the Roman Catholic Church and his long-suffering and devoted first wife Katherine of Aragon, Sander recorded:

'Anne Boleyn was rather tall of stature, with black hair and an oval face of sallow complexion, as if troubled with jaundice. She had a projecting tooth under the upper lip and, on her right hand, six fingers. There was a large wen under her chin, and therefore to hide its ugliness, she wore a high dress covering her throat. In this she was followed by the ladies of the court, who also wore high dresses, having before been in the habit of leaving their necks and the upper portion of their persons uncovered. She was handsome to look at, with a pretty mouth'.

The last sentence, in view of Sander's shattering and devastating description of Anne, is entirely contradictory. Regarding Anne Boleyn as the Devil's accomplice and the incarnation of evil, he gave her a witchlike appearance. This was an age, as Retha Warnicke notes in her study of Anne, when a person's outer appearance was believed to reflect and embody their inner character. Believing Anne to be utterly evil, Sander presented her as ugly, deformed, monstrous: she had a projecting tooth, an extra finger, a large wen. His statement indicated his complete lack of knowledge about fashion tastes at Henry VIII's court. A glance at portraiture from this era confirms that ladies-in-waiting did not tend to wear high dresses, including Anne.

Above: Another gorgeous Anne. Natalie Portman as Anne Boleyn in The Other Boleyn Girl (2008).

Putting to one side Sander's outrageous claims, Anne Boleyn is almost always depicted in cultural works as a ravishing beauty, a stunning woman who dressed fashionably, spoke beautifully, and enchanted all who knew her. But, as we have just seen, even observers who were at least neutral, if not friendly, to Anne confirmed that she was not jaw-droppingly beautiful. They confirmed that she was attractive, or reasonably good-looking, but none of them were swept off their feet by her physical appearance.

Most scholars agree that it was not Anne's physical looks so much as her charm, her intelligence, her accomplishments, her wit, her fiery nature, her uniqueness, in short, that captivated Henry VIII and kept his attention for the best part of 10 years. Bordo thinks our fixation with Anne's physical appearance in popular culture may lie in twentieth- and twenty-first century limits of the concepts of attraction, 'fixated as they are on the surface of the body'. Henry VIII certainly wasn't fixated on the surface of Anne's body. By all accounts, he was completely taken with her in a way he never was with any of his subsequent wives or mistresses. There was, in short, something special about Anne that cannot be restricted to her body.

Looking at Anne's portraits in an attempt to discern what she really looked like is a futile exercise. As mentioned earlier, none of them are contemporary to her, the earliest ones being produced something like fifty years after her death, and many of them later. Lacey Baldwin Smith, author of books on both Anne Boleyn and Katherine Howard, wittily quipped: 'Tudor portraits bear about as much resemblance to their subjects as elephants to prunes'.

Anne seems, in short, to have had style. Lancelot de Carles comments on the beauty of her dark eyes and her ability to captivate and entrance men merely by looking at them. One commentator reported than she was 'more a Frenchwoman' than she was English, and the French, of course, are renowned, then as now, for their style and elegance. Sixteenth-century England valued clear-skinned, blue-eyed, blonde women who were celebrated as the epitome of beauty, including Mary Tudor, younger sister of Henry VIII (below). Anne, with her 'small' breasts, dark complexion and dark hair, challenged these norms and brought in fashions and styles of her own to replace these ideals.

Above: Mary Tudor, queen consort of France, was the epitome of Tudor ideals of beauty: clear-skinned, fair-haired and light-eyed.

Bordo sums up what it was about Anne that enchanted the king:

Henry's attraction to Anne, in any case, seems to have been fueled not only by sexual attraction but by common enjoyments, compatible interests, intellectual stimulation, and shared political purpose.

Too often, as in the 2008 film The Other Boleyn Girl, Anne is characterised as a shallow, bosomy schemer who thrusts herself brazenly before the king. She is reduced, in short, to a sex symbol. But as Bordo's statement makes clear, Anne Boleyn was so much more than that. She was a devout evangelical; a keen intellectual; a woman interested in politics; possessed of a sharp mind; charitable and pious; loyal to her family and friends; musically gifted; and talented in languages. This was no floozy who wormed her way into the king's bed with seductive promises of bedtime pleasures. This was a woman who shone in the court of England as she had in the Flemish and French courts during her teenage years.

Why is it, then, that popular culture tends often to reduce her to a sex symbol or an icon of perfect beauty? What does it suggest about our own narrow, constricting, possibly harmful views of attractiveness, particularly in relation to women? Does it indicate that a woman can only be truly attractive if she is physically stunning, regardless of her intellectual and personal accomplishments? Contemporary evidence makes it devastatingly clear that Anne Boleyn was not a woman who stole hearts merely on the basis of her appearance. Popular culture would stay truer to the real woman and her incredible legacy if it focused, instead, on her remarkable personality, her contradictions, her flaws, her religious outlook, her political activities, her charities, her charm, her culture, her fashion sense, her wit, her humour, her arrogance, her insecurities, her family loyalties and devotion to her friends - everything, in short, that made Anne Boleyn a bundle of contradictions.

Published on September 25, 2014 10:52

September 21, 2014

21 September 1327: The Death of Edward II?

Above: Edward II's tomb effigy at Gloucester Cathedral.

Edward II, king of England from 1307, allegedly died at Berkeley Castle twenty years later, on 21 September 1327. As biographer Harold F. Hutchinson explains in his 1971 study of the king: 'The true story of the manner of Edward's death can never be known for certain'. The former king had been deposed in January 1327 and succeeded by his fourteen-year old son Edward, known as Edward III. His father's reign had, in the words of Natalie Fryde, been 'disastrous'. Edward's wife, Isabella of France, had invaded the country in September 1326 having initially departed to be involved in peace negotiations with the French king. Outraged by the power wielded by her husband's favourites, the Despensers, who had sequestrated her estates and virtually imprisoned herself and her servants, Isabella returned to England alongside her ally - and possibly lover - Roger Mortimer, later earl of March, and a host of supporters. City after city in England supported her, including London, which became her most imposing stronghold. Edward II was taken to Kenilworth Castle, where the bishop of Hereford demanded that he abdicate, charging the king with, amongst other things, being personally incapable of governing; of allowing himself to be led and governed by others; of devoting himself to unsuitable occupations while neglecting the government of his kingdom; of forfeiting the king of France's friendship, and losing the kingdom of Scotland and lands and lordships in Ireland and Gascony; and of exhibiting pride, cruelty, and covetousness.

Edward remained virtually imprisoned at Kenilworth until 2 April 1327, when he was transferred to the custody of Thomas Berkeley and John Maltravers, following a plot led by the Dominican John Stoke to free him. In July, a further conspiracy to release him occurred, and on 14 September, Sir Rhys ap Gruffudd's plot to liberate him was uncovered. A week later, at the parliament at Lincoln, it was announced that the former king had died 'a natural death' at Berkeley Castle in Gloucestershire. His corpse was moved to Gloucester for public display a month later, and on 20 December he was buried in St Peter's Abbey, Gloucester, in the presence of his son and his widow. A splendid tomb was erected by Edward III in his father's memory.

Above: Berkeley Castle, where Edward II allegedly died in 1327.

Historians traditionally accepted that Edward II died at Berkeley Castle on 21 September 1327. Hutchinson, for instance, noted that although a mystery surrounded his end, 'the only fact which seems well established is that Edward of Caernarvon was murdered, if not to the instructions of, at least with the connivance of Mortimer, and probably also of Isabella [Edward's wife]'. But as Natalie Fryde correctly noted in her 1979 study of the last years of his reign, 'if we separate contemporary evidence about his [Edward's] fate from the legend which has accrued around it, we are certainly left with more mystery than certainty'. It is essential to bear in mind this point - legend has replaced concrete historical fact regarding Edward II's end. An obvious example of this is the lingering popularity of the notion that Edward died by having a red hot poker thrust into his anus, allegedly a gruesome parody of his enjoyment of homosexual sex. The chronicle of Geoffrey le Baker (died c. 1360), reported this, as did the Brut chronicle, composed in the 1340s. But both Ian Mortimer and Kathryn Warner have disputed the 'anal rape' narrative of the king's death, arguing instead that it reflected beliefs that he was the passive partner in male-male sexual relations. There is, in short, no compelling evidence for the red hot poker story. As Hutchinson incredulously noted, Baker 'asks his readers to believe that Edward's murderers were so inept, and the castle walls so thin, that townsfolk outside the castle were able to hear the king's dying shrieks'. He dismisses Baker's claims as being 'lurid fiction'.

Above: Gloucester Cathedral, where Edward II may - or may not - be buried.

Other contemporary chronicles were more vague. This perhaps arises from the fact that the actual cause of the former king's death was never stated. Adam Murimuth, writing in the reign of Edward III, vaguely noted that Edward II was 'commonly said' to have been murdered as a precaution on the orders of Maltravers and Gurney. Edward's death has always invited suspicion. As Mark Ormrod notes, it was 'suspiciously timely', leading some historians to argue that the former king was murdered on the orders of the new regime. Kathryn Warner also noted in a blog post that Edward's 'death might have appeared suspiciously convenient for Roger Mortimer and Queen Isabella'. Professor Phillips, who wrote a magisterial account of the king's life, stated that murder was the likeliest fate of Edward II. He noted, however, that the king could have died of natural causes. Phillips dismissed reports of the former king's survival as being 'circumstantial', but noted the mystery about his supposed end.

Most historians have agreed that Edward II died at Berkeley Castle on the night of 21 September, perhaps of natural causes, perhaps through murder. Phillips stated that he may have been suffocated; Roy Haines speculated that the former king had been murdered and stated 'there is little reason to doubt that Edward of Caernarfon's corpse has remained there [at Gloucester Cathedral] undisturbed since December 1327 or thereabouts'; Michael Prestwich opined that Edward II 'almost certainly died at Berkeley'; Mira Rubin concluded that the former king was likely murdered; Joe Burden charged Mortimer with ordering Edward's death; and Chris Given-Wilson explained that Edward II was 'almost certainly' murdered on the night of 21 September, and died in any case.

Above: Edward III, who succeeded in 1327 on the abdication of his father.

Yet, as Warner recognises, it was only after the downfall of Mortimer and Isabella in 1330 that Edward II was reported to have been murdered, at the parliament at Westminster. Edward III accused Mortimer of 14 heinous offences, including ordering the murder of his father. Thomas Lord Berkeley, son-in-law of Mortimer and former custodian of Edward II, reported at this parliament that 'he wishes to acquit himself of the death of the same king, and says that he was never an accomplice, a helper or a procurer in his death, nor did he ever know of his death until this present parliament', a sentence that has confused and puzzled historians ever since.

Other points of mystery exist. Maltravers was never accused or punished for his role in the former king's death. Berkeley himself was acquitted, as was Shalford. The former king's half-brother, the earl of Kent, conspired in 1330 to free Edward from captivity, writing a letter outlining his intent to release his half-brother with 'the assent of almost all the great lords of England'. William Melton, the archbishop of York, wrote a letter to Simon Swanland, a London merchant, in 1329/30 asking him to co-operate with William Clif in aiding the 'old king' upon his release, specifically describing the delivery of clothes and money to Edward.

Moreover, in the nineteenth century the so-called "Fieschi Letter" came to light. Written by Manuele Fieschi, a papal notary, Canon of York and Nottingham, and Bishop of Vercelli from 1342, the letter reports that Edward II escaped from Berkeley Castle in autumn 1327, making his way to Corfe Castle in Dorset, before departing for Ireland and later to Avignon clothed as a pilgrim. He spent two weeks with the pope, before making his way to Brabant, Cologne and later Italy. Recently, historians have generally tended to validate the letter's contents. Fryde stated: 'it is very difficult to think why Fieschi himself... should have manufactured such a letter'. Ian Mortimer believed it was genuine, and devoted considerable time in his studies of Roger Mortimer and Edward III to explaining his theory that Edward II was not, in fact, murdered at Berkeley Castle, and escaped to Europe. Ian Doherty and Alison Weir also accepted that the letter was genuine, and concluded that Edward did escape to Europe, living out his life as a pilgrim.

'William the Welshman' met Edward III at Koblenz in September 1338, claiming to be the king's father. Edward III spent some time with him. As Warner relates: 'other royal pretenders of the era definitely did not spend several weeks socialising with the royal personage they were pretending to be, or claiming kinship with'. She later concluded that 'Edward II or not, the whole episode is an oddity'.

Above: another unlucky king. Edward II's great-grandson, Richard II, was also deposed in 1399, and probably murdered early the following year.

Plainly, there is a wealth of evidence to call into question the traditional notion that Edward II died (probably murdered) on 21 September 1327 at Berkeley Castle. While agreeing with Ian Mortimer that it cannot now be stated with any certainty that the former king's life came to an end in the autumn of that year, less than nine months after his forced abdication, I raised some issues with the survival story. There are nagging questions in my mind that Ian Mortimer, and other revisionist historians, have not sufficiently answered (if they have even considered them in the first place). Firstly: why did Edward III wish to get back in touch with his father, as Mortimer suggests? What did it achieve? Did he want to see if 'William the Welshman' was merely an imposter, or had he enjoyed a close and intimate relationship with the former king pre-1327 that he wished to continue?

Was Edward II content to live as a pilgrim in Europe? Evidence seems to me to compellingly indicate that Edward II firmly believed in the institution of monarchy and was convinced of his right to rule. He was anoited by God, chosen by Him to represent God on earth. Why, then, would he have been content to allow his son to rule? To remove a king unlawfully, which had been the case in 1327 (Edward II only abdicated under duress and coercion), constituted usurpation and a damnable offence in the eyes of God. Ian Mortimer suggested that father and son, reunited in Europe, met and talked with one another. Was there an agreement between them that Edward III would keep his father's identity secret, as long as his father did not make a bid for the English throne? Questions like these are never comprehensively answered.

Berkeley, at the parliament of November 1330, could have been lying in an attempt to save his own skin when he declared that he had never previously heard of Edward II's death. In the medieval context, deposition was usually followed by death. Edward II was the first king to be deposed, but consider later instances: Richard II is believed by historians to have been put to death, or forcibly starved, in 1400 when Henry IV took the throne from him; Henry VI was murdered in 1471, almost certainly on the orders of Edward IV who deposed him; the twelve-year old Edward V was deposed in 1483 and probably murdered, although mystery surrounds his fate and that of his brother; and the deposed Lady Jane Grey, the 'nine-days queen', was executed by her cousin Mary I in 1554. Mortimer and Isabella's regime was notably precarious and unstable, as historians like Fryde recognise. Would they really have been content to allow Edward to live out his days in context of repeated rebellions to release him? Even if they had nothing to do with his death, his jailers may have considered that putting him to death was the only viable way forward. Or, simply, he may very well have died of natural causes.

This article does not seek to refute revisionists' claims that Edward II survived. It is extremely possible that he did, for there is no conclusive evidence that he died, or was murdered, at Berkeley Castle in 1327. But equally, it cannot be stated with certainty that he escaped abroad and lived out the rest of his days in Europe. Whether Edward II, an ill-fated and complex king, met his end at Berkeley in autumn 1327 or not, is a profound and lingering historical mystery that may never be comprehensively solved.

Published on September 21, 2014 09:47

September 11, 2014

The Wars of the Roses: A Tudor Construction?

Historian Dan Jones has published an interesting article in the October 2014 edition of BBC History Magazine claiming that the Wars of the Roses, the dynastic conflict between the royal houses of Lancaster and York in the mid-to-late fifteenth century, might have been a Tudor construction invented by that dynasty to consolidate and legitimise their rule. Some historians have supported this approach. K. B. McFarlane argued years before that there was no such thing as the 'Wars of the Roses'. This period of history has become ever more popular with the success of Philippa Gregory's "Cousins' War" novels (and the BBC television adaptation of one novel, The White Queen). But is Jones right to claim that the Wars of the Roses was, effectively, invented by the Tudors to explain their success in attaining the throne? Is the traditional interpretation of the conflict, so vividly described in Shakespeare's plays, 'misleading, distorted, oversimplified and - in parts - deliberately false'?

To start with, the term 'Wars of the Roses' certainly does not date from the time of the conflict. Sir Walter Scott seems to have coined it in his novel Anne of Geierstein, published in 1829. Scott in turn came up with the name having read Shakespeare's play Henry VI Part 1, specifically a scene in which a number of noblemen and a lawyer in the gardens of the Temple Church select red or white roses to demonstrate their loyalty to the Lancaster or York house, respectively. Jones is probably correct in suggesting that the Lancastrians never actually used the red rose as a badge during the period of conflict. As Adrian Ailes comments, Henry VII's decision to combine the red and white roses as a symbol of the end of conflict between Lancaster and York 'was a brilliant piece of simple heraldic propaganda'.

Leanda de Lisle, however, recently suggested that the term 'Wars of the Roses' actually originated long before the publication of Scott's novel in 1829. She mentions that historian David Hume referred to 'the wars between the two roses' in his work of 1762, while more than a hundred years earlier the conflict was described as 'the quarrel of the two roses'. Lisle interestingly notes that Edward IV made extensive use of the white rose as a badge representing the House of York, for it was believed to have been the badge of Edward's ancestor Roger Mortimer, the supposed 'true' heir of Richard II before his right was 'usurped' by Henry IV. Perhaps most intriguingly of all, Lisle dismisses claims that the conflict should instead be known as 'the Cousins' War'.

Above: did the Wars of the Roses really involve the red rose of Lancaster competing for the throne against the white rose of York?

Jones' argument that the Wars of the Roses was an invention of the victorious Tudors hinges on the suggestion that it is a myth that the wars erupted because 'there were too many men of royal blood clustering around the crown, vying for power and influence over a weak-willed king'. Yet, in histories of the conflict that I have read, it is argued that conflict broke out firstly because of Henry VI's incompetence as a king, and secondly because of military disasters in France. England lost all the territories it had conquered and was left only with Calais (later won back by the French in 1558). Jones argues, fairly, that the 1420s saw no serious unrest and speculates that Henry VI's weak kingship did not ultimately result in dynastic conflict until he experienced insanity in 1453. This is correct. In stating this point, why does Jones seem to imply that historians have traditionally viewed the roots of the conflict as occurring as early as the 1420s/30s? To me, it was Henry VI's madness in 1453 that instigated the conflict. His illness allowed Richard duke of York to seize the reins of government, leading to conflict and rivalry with Henry's queen, Margaret of Anjou. Jones speculates that Henry VI's forced decision to disinherit his own son Prince Edward in 1460 in favour of the Yorkists was the point at which 'the wars became dynastic'. Surely this is stating the obvious: beforehand, conflict between York and Edmund Beaufort, duke of Somerset, occurred because both men were fighting for control of the king and the greater power and influence at court. But at some point, York seems to have concluded that he would make a stronger and more efficient king than the incapacitated Henry VI.

Above: Henry VI, house of Lancaster (left).

Edward IV, house of York (right).

In dividing the conflict into four phases, Jones' conclusions do not suggest that the Wars of the Roses was necessarily a Tudor invention. Rather, it indicates that the term 'Wars of the Roses', itself, is not perhaps the most helpful or effective way of characterising this period of dynastic conflict, especially given the fact that neither house probably employed their rose as the most prominent badge to represent their claim. The Tudors' decision to incorporate the red and white roses into what became the Tudor rose - achieved by Henry VII's marriage to Elizabeth of York in 1486 after his victory at Bosworth - was undoubtedly propaganda at its most effective, indicating that they had brought unity, harmony and sound rule to England after thirty years or so of political, governmental and dynastic unrest. But I remain unconvinced by Jones' claim that the Wars of the Roses should be considered a construction of the victorious Tudors. If anything, I came away from his article more convinced than before that it was a period of dynastic conflict, in which rival families sought to obtain the throne. Maybe they were not neatly separated into Lancaster and York, that is fair enough. But after 1460, there was certainly concerted rivalry between those loyal to Henry VI and the Lancastrians, and those who favoured Edward IV and the Yorkists, that blossomed due to increasing determination to obtain the throne and achieve peaceful governance after years of serious unrest.

Published on September 11, 2014 09:59

September 5, 2014

5 September 1548: The Death of Queen Katherine Parr

On this day in history, 5 September 1548, the former queen of England Katherine Parr died aged thirty-six at her home, Sudeley Castle, in Gloucestershire. It was a sad and tragic end to an extraordinary life and, in particular, provided a closing chapter to one woman's remarkable journey from minor gentry to queenship to comfortable nobility. Katherine's fate mirrored that of countless medieval and Tudor women: she died of puerperal fever shortly after giving birth to her first and only daughter, Mary. Tragically, her young daughter probably lived to be no more than two years old, although her exact fate is unknown.

On this day in history, 5 September 1548, the former queen of England Katherine Parr died aged thirty-six at her home, Sudeley Castle, in Gloucestershire. It was a sad and tragic end to an extraordinary life and, in particular, provided a closing chapter to one woman's remarkable journey from minor gentry to queenship to comfortable nobility. Katherine's fate mirrored that of countless medieval and Tudor women: she died of puerperal fever shortly after giving birth to her first and only daughter, Mary. Tragically, her young daughter probably lived to be no more than two years old, although her exact fate is unknown. In spring 1782, Katherine's coffin was discovered by some ladies visiting the castle. They discovered the inscription which read:"Here lyeth Queen Katheryne Wife to KingeHenry the VIII andThe wife of ThomasLord of Sudely highAdmy… of EnglondAnd ynkle to KyngEdward VI".

Katherine was unique in many ways: she was the first Protestant queen of England, she was the first English queen to publish books, she was the most married English queen (with four husbands in all), and perhaps most fortunately, she was the only one of Henry VIII's wives to 'survive' him (although the rejected Anne of Cleves actually survived all his wives, dying in 1557, nine years after Katherine Parr). Indeed, it is this which most people tend to remember about Katherine: she 'survived' her husband. Others believe she was an old nursemaid who dutifully and compassionately attending to the ailing and irascible Henry VIII in his old age. This is very far from the truth. Katherine was an educated, principled, pious and charitable woman who also loved fine clothing and jewellery, adored dancing, had a strong romantic streak, and was kind and loving to her family and friends. She was admired during her own lifetime and has legions of admirers to the present day, including Camilla, duchess of Cornwall. In many respects, Katherine was an excellent candidate for the position of queen of England.

Biographer Linda Porter believes that Katherine's influence was particularly important with her three royal stepchildren: Mary Tudor (who was only four years younger than her), Elizabeth, and Edward. She brought them to court and established loving and close relationships with all three. Although some of Henry's other queens, namely Anne of Cleves and Katherine Howard, had also attempted to bring the royal family together, it was Katherine Parr who provided a mother figure for Elizabeth and Edward, who had been cruelly deprived of their mothers at a very early age (Elizabeth's mother was beheaded when she was not yet three, while Edward's mother had died from puerperal fever only twelve days after his birth). To Mary, who had also suffered the loss of her mother in a humiliating and dragged-out annulment battle, Katherine was a warm and supportive companion, although the two experienced a more strained relationship after Henry VIII's death and Katherine's remarriage to Thomas Seymour.

Katherine's life was truly extraordinary. Born in 1512 (historian Susan James, who published an academic study of the queen, thought that she was probably born in about July or August of that year), Katherine's family was respected northern gentry, and she appears to have been named after Katherine of Aragon who was, of course, the first wife of Katherine Parr's future husband, Henry VIII (Maud Parr, her mother, was a close favourite of Katherine of Aragon at court). She was later married for the first time in 1529 to Edward Borough in Lincolnshire, but her husband died only four years later, leaving Katherine widowed - not for the first time - aged twenty-one.

Katherine's life was truly extraordinary. Born in 1512 (historian Susan James, who published an academic study of the queen, thought that she was probably born in about July or August of that year), Katherine's family was respected northern gentry, and she appears to have been named after Katherine of Aragon who was, of course, the first wife of Katherine Parr's future husband, Henry VIII (Maud Parr, her mother, was a close favourite of Katherine of Aragon at court). She was later married for the first time in 1529 to Edward Borough in Lincolnshire, but her husband died only four years later, leaving Katherine widowed - not for the first time - aged twenty-one.A year later her second husband was Lord Latimer, a man twenty years older than her with two children of his own. Katherine became, as with the Tudor children, a warm stepmother. She resided at Snape Castle in Yorkshire. Lord Latimer was a conventional Catholic, and historians such as David Starkey, aware that Katherine Parr later as queen developed strong reformist tendencies that we would now associate with Protestantism, have questioned whether she, too, was a traditional Catholic in these years, or whether she had already began to develop reformist ideas and beliefs that set her up in conflict to her conservative husband. The north of England was conservative as a whole, and in 1536 the most threatening rebellion of Henry VIII's reign, the Pilgrimage of Grace, occurred. Terrifyingly, Katherine herself and her stepchildren were seized as hostages in their own home. Cromwell later blackmailed Lord Latimer due to his involvement, even if unwilling, in the rebellion. Later, the couple departed for London, where they were living when Lord Latimer died in spring 1543.

Above: a family painting of Henry VIII sitting with his son, Edward, flanked by his two daughters: Mary to the left, and Elizabeth to the right. The queen who sits with Henry is his third wife Jane Seymour, although, painted as it was in 1544, his wife at that time was Katherine Parr.

Above: a family painting of Henry VIII sitting with his son, Edward, flanked by his two daughters: Mary to the left, and Elizabeth to the right. The queen who sits with Henry is his third wife Jane Seymour, although, painted as it was in 1544, his wife at that time was Katherine Parr.

Henry VIII's previous wife Katherine Howard had been executed in February 1542, and by spring 1543 the ageing king had still not remarried. At some point, he became attracted to the widowed Katherine Parr, and proposed marriage to her. Katherine felt doubt and discomfort. She appears to have been in love with Thomas Seymour, brother of the late queen Jane, at this point. But after much soul-searching, as she later admitted, she felt it was God's will that she marry the king. She perhaps also felt it would provide an excellent opportunity for her to bring about further reform within the church. On 12 July 1543, she became the sixth wife of Henry VIII at Hampton Court Palace.

While the king may not have passionately adored Katherine Parr, as he did Anne Boleyn, he does appear to have respected her deeply and to have felt genuine affection for her. Katherine, on her part, worked hard to be an effective and successful queen consort. Evidence of Henry's admiration and affection for his wife can be found in the fact that, in 1544, when he departed for France for war, he appointed her Regent. None of his other wives, with the exception of Katherine of Aragon in 1513, enjoyed this prestigious honour. Katherine was clearly ambitious. The following year, she began publishing religious works which outlined her reformist views that were bordering on the radical. Indeed, Katherine soon found herself in a position of danger when in 1546, if the martyrologist John Foxe is to be believed, the conservatives at court instigated a plot to accuse the queen of heresy. Anne Askew, who was associated with the queen, was burned at the stake in July 1546. Katherine supposedly discovered news of the plot and, falling into panic and distress, pleaded for forgiveness from the king and convinced him of her innocence. Luckily for her, she was successful.

In January 1547, the king died aged fifty-five. We cannot know what Katherine felt, but only three months later she married for the fourth time to Thomas Seymour. This may have been a love match, but perhaps the dowager queen also felt she required a helpmate and strong man to support her. Since Seymour was uncle of the new king, Edward VI, it can be argued, as Linda Porter credibly did, that she regarded marriage to him as strengthening her hand and ensuring her continuing political relevance in the kingdom. Although her stepdaughter Elizabeth and the future queen Lady Jane Grey came to reside in her household, Katherine had to battle the Lord Protector Edward Seymour, elder brother of her husband and thus her brother-in-law, for control of her dower estates.

What happened next has been shrouded in controversy, but it appears Thomas Seymour began a flirtation - some would call it abuse - with the thirteen-year old Elizabeth. Unbeknownst to Katherine, he had actually, before marrying Katherine, petitioned both Mary Tudor and Elizabeth for marriage, and later even considered marrying the nine-year old Jane Grey. Clearly, Seymour was an ambitious, perhaps even unscrupulous man, who desired greater political influence and power. What he was doing with Elizabeth cannot now be known for sure. Undoubtedly, it brought scandal to Katherine's name, and she banished Elizabeth from her household in spring 1548. Rumours circulated that Elizabeth was delivered of a child in secrecy, the offspring of Thomas Seymour.

At this time, Katherine was pregnant. At a time when most Tudor noblewomen married about twenty and, in some cases, in their teens (Katherine herself had been only in her seventeenth year when she married for the first time), Katherine, at thirty-five, was rather old to be expecting her first child. This is evident in numerous letters written by her friends and relatives, who anxiously warned her of the risks of childbirth and offered soothing and comforting messages and advice. After a difficult pregnancy, Katherine gave birth not to the much-desired son but to a daughter, who was named Mary, on 30 August 1548. Only six days later, between two and three in the morning, she herself died, only thirty-six. Supposedly, she had reprimanded her husband beforehand for his ill-treatment of her, probably referring to the scandal with Elizabeth, but this story cannot be corroborated.

Katherine Parr's end was tragic. But her life was extraordinary and deserves to be remembered, admired, even celebrated. She was a successful and diligent queen consort who brought family stability and a measure of much-needed dignity and calmness to court, following the king's previous marital scandals. For perhaps the first time, Henry VIII and his three children enjoyed, under Katherine's influence, a degree of harmony and closeness with one another. Katherine Parr was far more than merely the 'survivor' of a much-married monarch.

Published on September 05, 2014 02:38

August 21, 2014

Myths About Henry VIII's Six Wives

The average person's knowledge of the six wives of Henry VIII will most likely have been shaped more by myths than by concrete historical fact. This may seem a bold claim to make, but the continuing popularity of ideas such as Anne of Cleves being 'a Flanders Mare', for example, or Anne Boleyn a six-fingered witch who slept with her brother, tends to support this statement.

The myths, legends and stereotypes of the six wives have been explored in some depth by Claire Ridgway over on The Anne Boleyn Files. This blog post concentrates in less detail on the most well-known, occasionally sensational, myths concerning these women, looking at each wife in turn.

Katherine of Aragon: Queen 1509-1533

Myth: Katherine was a bloodthirsty and fanatical Catholic.

Myth: Katherine was sultry, dark-haired and olive-skinned.

Katherine was Henry's first queen, marrying him in 1509. Their marriage officially lasted some twenty-four years by the time that it was annulled in spring 1533, although Henry VIII had been actively seeking an annulment of it since at least 1527. Katherine had been expelled from court in 1531, and never saw her daughter, Mary Tudor, again. She died, heartbroken, in January 1536, probably of cancer.

Admittedly, there are not as many myths concerning Katherine of Aragon as there are for Henry's other queens. Perhaps one lingering myth is of Katherine being a bloodthirsty Catholic who was fanatical about her faith to the point of brutality. This was suggested in Joanna Denny's controversial biography of Anne Boleyn (2004). Katherine certainly was, as David Starkey notes, a conventional and pious Catholic, and was the daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain, two dogmatic Roman Catholic rulers who had expelled the Jews from Granada in 1492. But there is no evidence of Katherine's supposed 'bloodthirstiness'. Some, perhaps seeking to explain Mary Tudor's religious policies as queen which infamously resulted in nearly 300 people being burned at the stake for heresy, have sought links with Katherine's Catholic faith, believing that she imposed her dogmatic religion on her daughter. There is no evidence of this. There is, in fact, little evidence of Katherine's personal beliefs on heresy, although it seems almost certain she viewed it with alarm and horror.

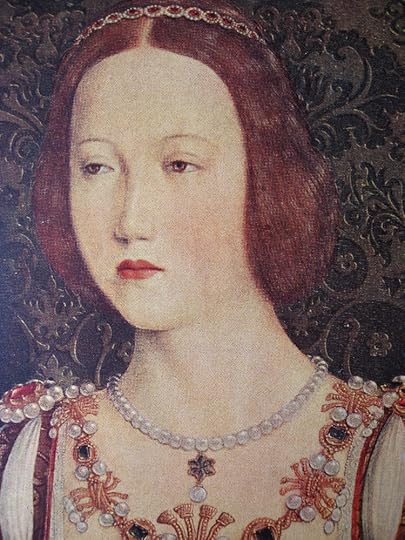

Above: a c.1502 portrait believed to depict Katherine as princess.

Above: a c.1502 portrait believed to depict Katherine as princess.

Another lingering myth about Katherine of Aragon is that she had a typical Spanish appearance: she was olive-skinned, dark-eyed, and black-haired. This is found in all varieties of popular culture: in the successful television series The Tudors, for example, Maria Doyle Kennedy depicts a brunette and swarthy Katherine. But as the above portrait shows (believed to be of Katherine in her youth), Katherine actually was of a very fair complexion, with long auburn hair and blue eyes. Attached to this myth is a belief that Katherine was physically ugly (in other words, looks were not her strong point). Yet historical evidence tends to confirm otherwise. During her lifetime, Katherine was described as being 'the most beautiful creature in the world', and Thomas More noted that there was 'nothing lacking in her that the most beautiful girl should have'.

There are not as many myths about Katherine as there are, for instance, concerning her successor Anne Boleyn, but for many, Katherine of Aragon is visualised as a dogmatic, stubborn, dull and dowdy Spanish woman with a dark complexion. The truth is very different. She was fair, beautiful and well-educated, revered for her piety.

Anne Boleyn: Queen 1533-1536

Myth: Anne Boleyn was deformed and disfigured, with six fingers.

Myth: Anne Boleyn was a witch.

Myth: Anne Boleyn was a sexual predator.

There seem to be more myths about Anne Boleyn, second queen of Henry VIII, than for any of his other wives. For many, Anne Boleyn was a six-fingered witch who likely slept with her brother. Others believe she was sexually 'corrupted' in France. Still others hold that she was physically disfigured, with moles and warts all over her body.

Above: Anne Boleyn.

Above: Anne Boleyn.

Nicholas Sander, a Catholic Reformation priest, invented a monstrous portrayal of Anne, whom he personally loathed and blamed for the development of the Reformation in England. He stated that she was very tall, with six fingers on one hand, a protruding tooth, and a wen under her chin. Sander reflected the Neoplatonic tradition, whereby a morally evil person was covered in deformities that revealed their true inner nature. George Wyatt, an apologist of the queen, amended Sander's characterisation to suggest that Anne had had a vestigial extra nail on one hand, but as Retha Warnicke as suggested, it is unlikely that Anne would have attracted the king had she even had this minor defect, at a time when deformities were regarded with horror and suspicion. Ambassadors who met Anne described her, surely accurately, as being of medium height, small-breasted, dark-haired, with a pretty mouth. No mention of deformities or warts there.

A second prevailing myth about Anne Boleyn is that she was actually a witch. This has been given impetus by Philippa Gregory's 2001 novel The Other Boleyn Girl, in which Anne consults with witches, produces a deformed child, and is said to seduce the king by witchcraft and sorcery. Sander depicted Anne as a witch and suggested that she had used the dark arts to become queen. Aside from this malicious propaganda, however, there is no evidence that Anne was a witch. She was never accused of witchcraft, contrary to popular belief. Henry VIII did state that he had been seduced into his second marriage by 'sortileges', but as Suzannah Lipscomb argues, this translates as 'divination' and suggests that Henry probably meant that he had been persuaded to marry Anne because of prophecies that she would bear a son. It does not necessarily translate as 'spells' or 'charms' that imply witchcraft.

[image error]

Above: Anne the sexual predator? Natalie Portman in The Other Boleyn Girl (2008).

Thirdly, a more popular myth in recent times casts Anne Boleyn as a sexual predator who not only manipulated Henry VIII into marriage, but seduced Henry Percy some years earlier, and possibly embarked on several extramarital affairs while queen, for which she was found guilty and executed. The Other Boleyn Girl presents a scheming and malicious Anne who plots to 'steal' the king from her sister and later sleeps with her brother George to conceive a male heir. In the first season of The Tudors, Natalie Dormer offers a similar portrayal: Anne is frequently naked or half-dressed, luring Henry with promises of sexual fulfilment and the son he so craves. But this is a myth! Feminist Karen Lindsey and Joanna Denny both suggest that Anne may have been sexually harassed by the king, for she may not have wished to marry him, and even if she did, it doesn't mean she purposefully went after him and sought to break up his marriage. There is also no convincing evidence that she slept around as queen, either.

Jane Seymour: Queen 1536-1537

Myth: Jane Seymour was a devout Catholic.

Myth: Jane Seymour supported and admired Katherine of Aragon and Mary Tudor.

Myth: Jane Seymour wanted Anne Boleyn dead.

Just eleven days after Anne Boleyn was beheaded, Henry VIII married for the third time to his late wife's maid of honour, Jane Seymour. Like Anne, historians have varied widely in their assessments of Jane. Alison Weir wrote admiringly of her that she was 'a strong-minded matriarch in the making', and Antonia Fraser also voiced admiration for her piety, gentleness and good character. On the other end of the spectrum, Joanna Denny condemned her for being 'sly', and David Starkey wrote scathingly in his 2004 study of the six queens: 'How Jane Seymour became Queen of England is a mystery. In Tudor terms she came from nowhere and was nothing'!

Above: Jane Seymour as queen.

Perhaps the number one myth about Jane Seymour is that she was a devout Catholic. Martin Luther did describe her as 'an enemy of the gospel', and historians have traditionally cited her supposed support for Katherine of Aragon (of which more below) and the Catholic faith, which set her up in opposition to the radical Boleyns. However, Pamela Gross found in her study of Jane that there is no convincing evidence that Jane was a devout and pious Catholic in a similar manner to that of Katherine. Her reign was essentially passive and there is no evidence of her personal religious beliefs. She did not act as patron for any religious works, unlike Henry's other queens. Alison Weir, nonetheless, wrote in her 1991 biography of Henry's wives that 'she was known to be an orthodox Catholic with no heretical tendencies whatsoever, one who favoured the old ways and who might use her influence to dissuade the King from continuing with his radical religious reforms'.

The second myth about Jane is closely connected with the first: many writers believe she was a strong supporter of Katherine of Aragon and that she admired and loved Mary Tudor, Katherine's daughter. The Imperial ambassador Eustace Chapuys wrote that Jane 'suggested that the Princess [Mary] should be replaced in her former position.' Weir stated that 'Jane greatly admired Queen Katherine, and later used her as her own role model when she herself became queen'. As Gross and Retha Warnicke have both pointed out, however, there is no evidence of this. Linked to this, Jane has been credited as being a peacemaker who brought Mary to court and reconciled her with her father. But Henry had insisted that Mary swear the Oath of Succession, thus agreeing that she was a bastard, and only restored her to favour and invited her to court in late 1536 when she had done so. Jane's involvement in this was minimal at best.

Thirdly, many continue to believe that Jane was not content with Henry annulling his marriage to Anne, but wanted her dead. The Victorian historian Agnes Strickland called Jane's conduct 'shameless' and condemned her for encouraging Henry's advances while Anne lay in terror in the Tower, awaiting the sentence of death. Some of Jane's conduct does appear calculating, for example in refusing a gift of gold sovereigns from the king in March 1536 which was calculated to inflame the king's ardour for her. But we do not know if Jane was being coached by her ambitious family, or whether she really was a virginal and chaste young woman who sought to protect her dignity and honour. There is no evidence that she wanted Anne dead, and we just do not know how she felt about her.

Anne of Cleves: Queen 1540

Myth: Anne of Cleves was 'a Flanders mare'.

There is only one major myth related to Anne of Cleves, but it is a major one. It has become enshrined in historical and popular consciousness worldwide that Anne, fourth wife of Henry VIII, was so ugly that he called her 'a Flanders mare'. This is still repeated in both novels and non-fiction. But it is exactly that: a myth. Henry VIII never referred to her as such - the label 'Flanders mare' dates from 1759 (Smollett, A Complete History of England), some two hundred years later!

Above: Anne of Cleves.

Anne is often depicted in popular culture as an ugly, awkward, disfigured but jolly woman who was too stupid to save her marriage, and blindly accepted the settlement which Henry bestowed upon her following the annulment of their marriage. But there is no evidence that Anne was unattractive. Christopher Mont, who resided in the household of Master Secretary Thomas Cromwell, stated that: 'everybody praises the lady's beauty, both of face and body. One said that she excelled the Duchess [of Milan] as the golden sun doth the silver moon'. Anne was not smelly, a popular misconception. Retha Warnicke published a study of Anne in 2000, and suggested that Anne was actually a very attractive woman with pleasant features. It was not so much her physical appearance that offended the king, it was the fact that he believed that she was pre-contracted to the duke of Lorraine, consequently impeding the consummation of his marriage to Anne. Psychological and cultural factors were at stake, rather than appearance.

Anne does not appear to have been a stupid woman, either. She got on well with Katherine Howard, her successor, and she was close to all of Henry's children, especially Elizabeth. She was famed for her successful household, and was much praised by all who knew her. To me, this indicates an intelligent, resourceful and perceptive woman of good sense. The fact that she seems to have gotten on well with all who knew her also suggests she was pleasant, kind, and good company. Hardly a 'Flanders mare'.

Katherine Howard: Queen 1540-1541

Myth: Katherine Howard was Henry VIII's 'rose without a thorn'.

I have already covered in detail misconceptions of Katherine Howard on this blog, and you can read my biography of Katherine (available NOW on Amazon), if you would like to learn more about her. Here, though, I will concentrate on one major myth about her that has recently been demolished by Claire Ridgway: that she was the king's blushing 'rose without a thorn'.

Above: Portrait of a woman, c. 1540, possibly Katherine Howard.

Agnes Strickland in the nineteenth century wrote of how Henry VIII ordered a coin struck in celebration of his marriage to Katherine, on which he referred to his new bride as his blushing 'rose without a thorn'. The name has since stuck - it was the title of Jean Plaidy's 1991 historical novel about Katherine, and is referenced by the likes of Philippa Gregory, Alison Weir, Antonia Fraser and Joanna Denny. But the legend on the coin, 'HENRICUS VIII. RUTILANS ROSA SINE SPINA', actually refers to Henry VIII himself, as noted by Dye's Coin Encyclopaedia. Tony Clayton noted that the coin was first struck in 1526, when the king was married to his first wife, Katherine of Aragon, so it had nothing to do with his marriage to Katherine Howard fourteen years later. David Starkey pointed out in his 2004 book that the motto/legend referred to Henry VIII and that the rose badge had nothing to do with Katherine, for she 'seems to have displayed no personal badge'. Sadly, then, for romantics, Katherine Howard was not affectionately nicknamed 'the rose without a thorn' by her adoring husband.

Katherine Parr: Queen 1543-1547

Myth: Katherine Parr was Henry VIII's nursemaid.

Myth: Katherine Parr was a heretic who could have been burned alive.

Myth: Katherine Parr was the least important of Henry VIII's wives.

[image error]

Above: Katherine Parr.

Katherine Parr was thirty-one when she became the sixth wife of Henry VIII in the summer of 1543. A prevailing myth about her, given both her age and Henry VIII's infirmities, is that she was not so much Henry's wife as she was his nursemaid. Legend has it that she applied poultices to the ageing king's leg ulcer and soothing him. Popular culture often follows this myth: in the 1970 BBC TV series The Six Wives of Henry VIII, Katherine Parr is a dowdy and frumpy middle-aged woman who nurses her ageing husband, and even in The Tudors, the glamorous Joely Richardson applies poultices to Henry's ulcer. As with the aforementioned myth concerning Katherine Howard, however, it seems this myth of Katherine Parr as nursemaid originated with the Victorian historian Agnes Strickland. David Starkey dismissed it contemptuously, and noted that the idea of a Tudor queen being her husband's nurse would have been both repulsive and unthinkable to the Tudors. There is no evidence that Katherine was her husband's nursemaid, contrary to popular belief.

A second prevailing myth about the sixth wife is that she was a Protestant heretic who could have been - and who almost was - burned at the stake for heresy in the mid-1540s. Katherine was definitely a reformist, and Antonia Fraser, among others, has consequently described her as the first Protestant queen of England. However, Parr's biographer Linda Porter notes that the Parr family 'were associated with reform and not ostentatiously so'. Katherine's printed works, including Prayers Stirring the Mind unto Heavenly Meditations, establishes her as an ardent evangelical who believed that the Bible should be in English. But Katherine cannot necessarily be called a heretic who was almost burned alive. John Foxe, in his "Book of Martyrs", depicted both Anne Boleyn and Katherine Parr as ardent Protestant queens who rescued England from the evils of the papacy, representing Anne as a martyr for her faith and Katherine nearly so, and he associated Katherine with the Protestant Anne Askew, who was burned alive in 1546 having been tortured. But we do not know how factual this account was, and it is uncertain if Katherine Parr really did come close to being charged with heresy.

Above: Katherine Parr as queen.

Finally, Katherine is often dismissed as the least important of Henry VIII's wives (beginning with historian Martin Hume in 1905), and as being boring and dull. However, she was far from that, and was one of the most important of his queens. Aside from her religious roles and activities, Katherine was an excellent stepmother who brought all three of Henry's children to court, establishing strong relationships with them (although she experienced conflict with Mary when Katherine remarried very soon after Henry VIII's death). Linda Porter describes how Katherine and Mary were close companions who shared a love of jewellery and fashion, music and dancing, and suggests that Katherine acted as a mother for the younger children, Elizabeth and Edward. Henry VIII also evidently trusted and respected Katherine enough to appoint her as his regent in 1544, when he left to pursue a war in France. Only Katherine of Aragon (in 1513) had previously occupied this honoured and trusted position. Her three month regency proved to be a success. Katherine was also the first Queen of England to become an author.

In conclusion, many myths and legends exist about the six wives of Henry VIII. This article has sought to demolish the most famous ones, seeking to offer the truth behind the legend.

Published on August 21, 2014 06:07

August 20, 2014

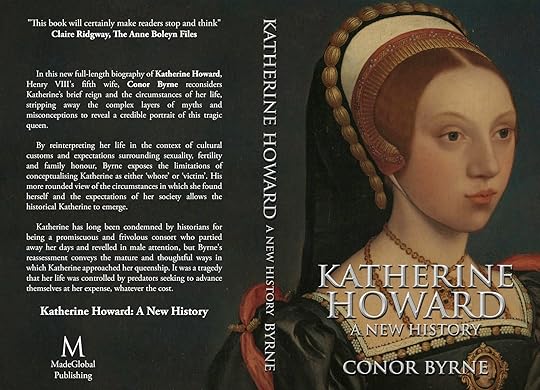

Release of "Katherine Howard: A New History"

My book, Katherine Howard: A New History, was published by Made Global Publishing on 13 August 2014 and is now available for purchase through Amazon. You can buy it either in a paperback format or on Kindle. The links are here:

Amazon US: http://www.amazon.com/Katherine-Howar...

Amazon UK: http://www.amazon.co.uk/Katherine-How...

As many of you will know, I have been researching Katherine's life properly since 2012. This blog began in November 2012, when after much thought I decided to regularly write about historical topics that interested me, and publicise them to as wide an audience as possible. Fittingly, perhaps, my first blog post in November of that year was on Katherine, discussing her birth date and childhood. If you are interested in reading this post, the link is here: http://conorbyrnex.blogspot.co.uk/201....

I have been astounded and humbled by the support I have received both with this blog and with my book. I thank each and every reader who has taken the time to read my blog posts, offer their thoughts (which I always appreciate), and continue visiting this site. If you are interested in reading the findings of my research over the course of several years, I encourage you to consider buying my book. As ever, I warmly welcome your thoughts on it.

Published on August 20, 2014 03:44

August 14, 2014

Margaret Tudor: the Forgotten Tudor?

[image error]

Above: Margaret Tudor, queen of Scotland.(accessed: http://www.nndb.com/people/074/000095...).

Henry VIII tends to outshine all of his siblings, for obvious reasons. Even so, most people, thanks to The Tudors' brazen portrayal, have some knowledge of his younger, impetuous sister Mary Tudor, who married first the king of France and later her brother's best friend, Charles Brandon, duke of Suffolk. Henry's elder brother Arthur Tudor, heir to the throne until his death at fifteen, is generally known for being the first husband of Henry's first wife, Katherine of Aragon. Controversy raged as to whether Arthur and Katherine had consummated their marriage.

But few are generally aware of Henry's elder sister, Margaret Tudor, who, like her younger sister Mary, was a queen. Margaret's life, in fact, was every bit as tumultuous and volatile as that of her younger brother. Her marriages and politics significantly shaped the future of both Scotland and of England. She was the grandmother of Mary Queen of Scots and the great-grandmother of James VI of Scotland and I of England. Her actions, in fact, played some part in the later union with England which was to result in the Act of Union in 1707. It might then be asked, how is it that Margaret remains so obscure a figure?

[image error][image error]Above: Margaret's parents, Henry VII (left) and Elizabeth of York (right).

Margaret Tudor was the second child of Henry VII and Elizabeth of York, who had married in 1486. She was born on 28 November 1489 at Westminster Palace in London. Although her father surely hoped for a second son, royal daughters were extremely useful because, through their marriages to foreign powers, they allied their countries with powerful states in prestigious unions. She spent her early years at her father's favourite place, Sheen, near the Thames (the palace was later renamed Richmond Palace), until a fire caused the royal nursery to be moved to Eltham. Margaret at an early age learned to play the lute, clavichord and to dance, traditional skills associated with feminine royalty. She also studied Latin and French, and pursued archery. It is likely that Queen Elizabeth ensured that her daughter also learned the traditional female skills of embroidery, sewing, and housewifery.

Henry was determined to bolster the prestige of the Tudor crown, particularly because pretenders continued to threaten its security. The Yorkist threat remained, meaning that the Tudor dynasty remained fragile. At the same time, England sought to achieve harmony with its northern neighbour, for the two had customarily experienced hostile and suspicious relations with one another. In view of these factors, it is unsurprising that the Tudor king arranged for his eldest daughter Margaret to marry James IV, King of Scots, a man sixteen years her senior. On 24 January 1502, the marriage treaty between England and Scotland was concluded. Henry promised a £10,000 dowry for his daughter's hand, while the Scottish king swore his bride would receive £1000 Scots per annum alongside lands and castles affording a further income of £6000 each year.

[image error]Above: James IV of Scotland, first husband of Margaret Tudor.

In February 1503, the royal family was plunged into tragedy with the death of the queen and Margaret's mother, Elizabeth of York, at the Tower of London aged thirty-seven. How Margaret felt is unknown, but at just thirteen years of age, it is reasonable to believe it impacted severely upon her. Nonetheless, preparations for her journey to Scotland continued, and on 8 July she commenced her journey north, her retinue led by the Earl of Surrey. The formal marriage service took place in Holyroodhouse on 8 August 1503. As historians have conjectured, Margaret may have found it discomfiting that her husband had seven bastard children, housed in her own dower castle of Stirling, and continued to visit his mistress Janet Kennedy.

Margaret's most important role as queen was to produce a male heir to safeguard the dynasty, and she duly did so in 1507, but the prince, named James for his father, died at Stirling in February 1508. A daughter born in July of that year died the same day. Like her sister-in-law Katherine of Aragon, Margaret experienced some tragedies in childbirth, but she was later to produce a healthy son. On 11 April 1512, aged twenty-two, Margaret gave birth to James, who later became James V, on his father's death at the Battle of Flodden on 9 September 1513.

Margaret was, according to her husband's will, to serve as regent, provided that she did not remarry. Four nobles headed a council to assist her in governing the realm. On 6 August 1514, less than a year after her first husband's death, Margaret remarried. Her husband was Archibald Douglas, sixth earl of Angus, the greatest Scottish magnate. Because of this decision, Margaret renounced her position as regent of the realm. Margaret's decision was perhaps regarded as impetuous and foolish, but she perhaps sought a measure of security and stability, being as she was a young widow with an infant son, alone in a foreign realm.

[image error]Above: Mary Stuart, queen of Scotland, was the granddaughter of Margaret Tudor.

The council subsequently invited John Stewart, cousin to the late king, to become regent. Margaret was distrusted, for her husband was extremely unpopular with the other magnates, and because she was rumoured to favour England over her adopted realm. Margaret deeply distrusted and resent Stewart, duke of Albany, and encouraged her brother, Henry of England, to restore her authority by force. On 30 September 1515, desperate and disillusioned, the former queen fled to England, in a move that strikingly foreshadowed that of her granddaughter Mary Stuart some fifty years later. Both queens sought refuge and assistance in England.

On 7 October, the heavily pregnant queen gave birth to a daughter, Margaret Douglas. The ordeal nearly killed her and left her very weak. When she lay seriously ill at Morpeth, her second son Alexander died in December of that year. On 3 May 1516, Margaret arrived in London and met her brother for the first time in thirteen years, since she had left for Scotland in summer 1503. She remained in England for over a year, separated from her husband, while the Scottish council promised to send the jewels after her and to pay her rents. While she received her jewels, her revenues were not in fact restored, forcing the humiliated queen to seek money from Cardinal Thomas Wolsey.