Conor Byrne's Blog, page 6

October 24, 2015

The Stereotyped Six Wives: Three: 'As Gentle A Lady'

Jane Seymour, third wife of Henry VIII of EnglandLifetime: c. 1508/9 - 24 October 1537Reigned: May 1536 - October 1537 (1 year, 5 months)Pregnancies: 1Edward VI of England: 12 October 1537 - 6 July 1553

In this new six-part series, I will be reexamining the lives and personalities of Henry VIII's six wives, seeking to portray their lives realistically in a process that discards prevailing stereotypes. Much scholarly work has been done on Henry's reign in recent decades, affording fresh insights into the politics and achievements of the period. Understandably, widespread interest in Henry's marital affairs remains unabated. Yet stereotypes continue to bedevil our knowledge of the wives of this most enigmatic king.

Jane Seymour, third wife of Henry VIII, became Queen of England upon her predecessor's execution for treason in May 1536. An unassuming woman in her late twenties, Jane is perhaps the most elusive of Henry's queens. Scarcely any evidence survives for her true personality. She was Henry's wife for merely seventeen months; yet her period as queen was tumultuous, in that it witnessed the restoration of Mary Tudor to favour, the unrest of the Pilgrimage of Grace, and the long-awaited birth of a healthy son to the king. Jane has attracted few biographers because of the shortage of evidence concerning her. In many ways, though, the mystery of Jane Seymour makes her as fascinating a person of study as Henry's other wives. Whether Henry VIII truly did love Jane, his 'entirely beloved' third wife, as legend has it, is an issue that has provoked considerable debate. In actuality, the tantalising evidence we have suggests that the story is more complex. Jane's queenship was passive and her famously meek, subdued character may have owed far more to the control of her domineering husband than is usually considered.

Above: Hampton Court Palace, where Jane Seymour died merely twelve days after the birth of her son.

Above: Hampton Court Palace, where Jane Seymour died merely twelve days after the birth of her son.

Jane was the fifth child and eldest daughter of Sir John Seymour and Margery Wentworth. Twenty-nine ladies walked at her funeral procession in 1537 to mark her age: whether that means she had reached her twenty-ninth birthday, or whether she was in her twenty-ninth year, is uncertain, but it indicates that she was born either in 1508 or 1509. As with Anne Boleyn, Jane's father was much favoured by Henry VIII. Sir John Seymour, a 'gentle, courteous man', had been knighted by Henry VII at the battle of Blackheath in 1497 and later accompanied Henry VIII on the French campaign in 1513. By 1532 he had become a Gentleman of the Bedchamber, and had acted as Sheriff of Wiltshire and Dorset. Sometime in the late 1520s, Jane arrived at court to serve Queen Katherine of Aragon. It is often assumed, with little supporting evidence, that Jane was loyal to Katherine and modelled herself on her. Aside from Jane's preference for gable hoods, which Katherine also liked, and Jane's later friendship with Katherine's daughter Mary, there is barely anything to suggest that Jane particularly admired Katherine or empthasised with her during the annulment proceedings.

Although she is rarely termed stupid, Jane is often regarded as being poorly educated. Indeed, there is no evidence that she had an aptitude for languages, and unlike Anne Boleyn she was not selected to participate in court masques, which suggests that her dancing and musical ability were unexceptional. Yet she was renowned for her talent in needlework and embroidery, with some of her work surviving well into the following century. Her contemporaries were also not especially enthusiastic about her appearance. Polydore Vergil described her flatteringly as 'a woman of the utmost charm both in appearance and character', but the Spanish ambassador was of the opinion that she was 'of middle stature and no great beauty', with a 'pure white' complexion. He also reported rumours that she was both 'haughty' and 'proud'.

Indeed, it is the very absence of evidence which makes it so difficult to grasp Jane's true personality. Most historians often refer to her piety and virtue, but aside from Luther's belief that she was 'an enemy of the gospel' - in other words, she was a devout adherent of the Catholic faith - there is barely anything to suggest that she was especially pious. In contrast to Anne Boleyn, who assisted religious reformers, or Katherine Parr, who wrote evangelical works of devotion, Jane was entirely conventional in her religious devotions and may not have been interested in taking an active role in religious politics. The absence of her involvement in court masques and dances, or poetry celebrating her talents, can tentatively be interpreted to mean that she was not talented musically or artistically.

For whatever reason, by early 1536 Jane Seymour remained unwed. At the age of twenty-six, it was certainly strange that her father had not arranged an advantageous marriage alliance for her, and even more unusual given that she was the eldest daughter. Her younger sister, Elizabeth, had married in 1531 and later remarried, to the son of Thomas Cromwell. Why no marriage had been arranged for Jane remains a mystery. We can only wonder how she herself felt about this: did she passively accept her fate as God's will, something to be accepted with resignation? Did she rebel, passionately hoping for an excellent marriage one day? We can only guess. Jane's fortunes, however, took a dramatically unexpected turn in the spring of 1536. Devastated by his wife's miscarriage, and uncertain whether his second marriage had won him divine favour, Henry VIII was susceptible to a new flirtation. For reasons that have puzzled historians for centuries, the object of his affections was Jane Seymour, the unassuming and apparently unremarkable attendant of the queen.

Historians have generally suggested that Henry VIII was attracted to Jane because she 'was unquestionably virginal' and because 'there was certainly no threatening sexuality about her'. In short, it was her virtue, her piety and her goodness that charmed the ageing king. By extension, these same historians seem to imply that these were qualities decidedly lacking in Anne Boleyn, thus conveniently ignoring the considerable evidence of Anne's piety and the importance she placed on her virtue. While Henry may have been captivated by Jane's demeanour, there may be a darker story at place here.

As queen, Jane selected the motto 'Bound to Obey and Serve', thus confirming her submission to Henry VIII's will both as her husband and as her king. How far the king himself directed his new wife in this, however, should be considered. Henry VIII had been dangerously obsessed by Anne Boleyn, an assertive, educated and independent young woman who had refused to become involved with him because it offended her piety and endangered her virtue. Anne's inability to provide the much-desired male heir had gradually reduced Henry VIII's burning love to burning hatred, leaving him with a strong desire to destroy her and rejoicing in her execution, to the surprise even of Ambassador Chapuys. With Jane, he had no wish to be denied and no wish to be told 'no'. Jane's motto confirmed her husband's control of her and signalled to the world that passivity and submission, rather than the proactiveness of Katherine of Aragon and Anne Boleyn, would characterise Jane's rule.

Above: Edward VI of England was born on 12 October 1537, only child of Jane Seymour.

Above: Edward VI of England was born on 12 October 1537, only child of Jane Seymour.

Just as it is problematic to view Anne Boleyn as directly responsible for Katherine of Aragon's rustication from court and ill-treatment, so it is erroneous to view Jane as responsible for Anne's brutal end, as Victorian historians often did. In questioning her morals and condemning her actions, as Agnes Strickland did, these historians failed to understand the position Jane was in and the character of the man she married. Like Anne, she simply could not say no. With the passing of time, Henry had become increasingly autocratic and, on the single occasion that Jane did dare to voice her true opinion, she was brutally put in her place by her irascible husband, who warned her to consider her predecessor's fate before involving herself in affairs of state. There is scarcely any evidence for Jane's supposed love and admiration of Queen Katherine, and there is next to no evidence that she was hostile to Anne or resented her rise to queenship. While she did offer friendship to Mary Tudor once she had married Henry, this is understandable given their closeness in age and their shared devotion to the Catholic faith. In 1536, perhaps Jane, mindful of Henry's rejection of Anne and indifference to his second daughter, wisely judged it best not to antagonise her husband by showing marked favour to her stepdaughter Elizabeth.

The absence of evidence for her inner feelings means that we cannot suggest that Jane was hostile to Anne Boleyn or deliberately sought to bring her down because of her aversion to the reformed faith favoured by Anne or because of her supposed loyalty to Katherine. In rejecting Henry's advances, in refusing to accept presents of money from him, in behaving 'modestly' rather than flirtatiously, perhaps Jane intended to signal a lack of interest that may well have been genuine. Her true feelings for Henry are usually ignored in the rush to condemn her supposedly callous behaviour. Jane Seymour's personality and motivations are swathed in mystery and remain largely inscrutable. She may have been ambitious, but equally she may have felt that she had no choice, as Katherine Parr did when presented with an unwanted marriage proposal by the king in 1543. Perhaps Jane resented Anne, but equally she may have accepted her as her mistress and wished to show her no ill-will. What does seem likely, however, is that Jane was coached by her ambitious relatives to attract the besotted king. Certainly they profited handsomely from her rise: her brother Edward became Viscount Beauchamp and her brother Thomas was knighted. It is uncertain whether Jane was a willing participant in the schemes of 1536 or whether she was manipulated by her family to serve their own ends.

Jane was never crowned as queen and her reign was entirely passive, as Pamela Gross noted in her academic study of Jane. She has usually been credited with restoring Mary Tudor to favour, but it is more likely that it was Henry himself who approved and brought about his daughter's return to court only after she had grovelled to him for her disobedience: 'I beseech your Majesty to countervail my transgressions with my repentance for the same'. Jane may have been sympathetic to Mary but she was not responsible for the latter's return to favour. Even if she had wished to enjoy Mary's company, Jane would not have forgotten for a second that her primary duty as queen was to provide a male heir, and would have acknowledged that Mary's position as the bastard of an unlawful union was a foreboding reminder of her own perilous position. As Henry himself warned Jane ominously: 'She ought to study the welfare and exaltation of her own children, if she had any by him, instead of looking out for the good of others'.

Despite the oft-repeated legend that Jane Seymour was Henry VIII's most beloved wife, there is, in fact, surprisingly little evidence of his love for her dating from her own lifetime. As noted earlier, when she had voiced sympathy for Mary her husband had bluntly advised her to concern herself with producing an heir herself. If the story of her plea for the abbeys to be saved from dissolution is true, then Henry's response, in brutally reminding her of Anne's fate, is indicative of a bullying husband seeking to control a wife and prevent her from becoming unruly. Within days of his marriage to Jane, Henry VIII reportedly was acquainted with two beautiful women and voiced regret that he had not met them before he had remarried. The Second Act of Succession, which was passed in the summer of 1536, vested the succession either in Jane Seymour's offspring or in the offspring the king might have with any future wife. How Jane viewed this Act cannot be known, but as the months passed without a pregnancy, she must have lived in considerable anxiety, if not fear.

Described by Cromwell as 'a most virtuous lady', Jane conformed entirely to Henry's wishes. If she had ambition, she suppressed it. If she held opinions, she chose not to voice them. If she disagreed with her husband's policies, she did not inform him. How far Jane willingly assented to her marginalisation, how wholeheartedly she embraced her motto 'Bound to Obey and Serve', are questions that simply cannot be answered. Yet she had witnessed Katherine of Aragon's determined refusal to disobey Henry's wishes, and she had heard of the ill-treatment inflicted on the proud queen in consequence. Jane's own marriage had been made in blood: her former mistress had been imprisoned, tried and executed in less than three weeks mainly because she had failed to give her husband a son.

Jane's queenship is characterised by most historians as passive, but they have not usually considered whether she was willing in the circumscribing of her queenly authority. In concerning herself solely with domestic affairs, Jane sought to please her husband, but his threatening behaviour on several occasions towards her was a chilling reminder of the danger she faced if she displeased him. By giving birth to her son Edward on 12 October 1537 at Hampton Court Palace, Jane earned Henry's undying love and appreciation, but during her own lifetime he never demonstrated the constant passion he felt for Anne Boleyn, or the unswerving devotion he experienced for Katherine Howard. In her own lifetime, Jane was a cipher. During her brief tenure as queen, she walked on a knife edge. Her two predecessors had been rusticated and had died, alone and shamed, for their failures to give birth to a son. This thought must have constantly been in Jane's mind, and her overriding emotion at providing the male heir in the autumn of 1537 may well have been relief.

Philippa Gregory's new novel The Taming of the Queen, which describes the life of Katherine Parr as queen, focuses on the circumscribing of the queen's authority, the restriction of her power and the utter submission of the queen to her husband. This portrayal could, with some fairness, apply to Jane Seymour. Her reign has been viewed as unremarkable and devoid of achievements, with the exception of Prince Edward's birth. Historians have appreciated that, outside of her immediate household, the queen was little more than a cipher, never exercising the militant authority of Katherine of Aragon or seeking to influence religious policies, as did Anne Boleyn. But they have, tellingly, failed to consider how willing Jane was in the restrictions she faced. Perhaps she willingly accepted them, perhaps she accepted her submission as the price of her queenship. Or perhaps she resented the limits imposed on her and bridled when faced with her husband's suffocating presence.

There is no evidence to suggest that Jane was unquestionably hostile to Anne Boleyn and sought her destruction, nor is there evidence that she admired and revered Katherine of Aragon. There is scarcely any evidence for Henry's supposed love for her. It was only after her death that Jane became 'entirely beloved' and her memory revered. Only in 1544 was she celebrated in Holbein's painting as Henry's one true wife, rather than Katherine Parr, his queen at the time. Jane Seymour's queenship was circumscribed, 'tamed'. She remains a mystery because she was a cipher at court. What emerges from the sources is the strong likelihood that it was Henry VIII who was responsible for holding her in submission and curtailing her authority to ensure that she pleased him and conformed to his will.

Published on October 24, 2015 07:40

October 23, 2015

The Stereotyped Six Wives: Two: A Dangerous Obsession

Anne Boleyn, second wife of Henry VIII of EnglandLifetime: c. 1507 - 19 May 1536Reigned: May 1533 - May 1536 (3 years)Pregnancies: 3 Elizabeth I of England: 7 September 1533 - 24 March 1603

Stillborn child: June/July 1534

Miscarried son: January 1536

In this new six-part series, I will be reexamining the lives and personalities of Henry VIII's six wives, seeking to portray their lives realistically in a process that discards prevailing stereotypes. Much scholarly work has been done on Henry's reign in recent decades, affording fresh insights into the politics and achievements of the period. Understandably, widespread interest in Henry's marital affairs remains unabated. Yet stereotypes continue to bedevil our knowledge of the wives of this most enigmatic king.

The historiography of Anne Boleyn, Henry VIII's second consort, is paradoxical. More has been written about Anne than any of Henry's other wives, yet she remains the most maligned of his queens. An explanation for this can perhaps be found in the polarising nature of the surviving sources. Protestant literature that approved of the break with Rome and celebrated the accession of Elizabeth I presented Anne as 'that most holy Queen', a charitable and pious reformer who had married the king solely to further the reformed faith. By contrast, Catholic polemical works depicted Anne as a monstrous vixen who had vindictively encouraged Henry to destroy both his first marriage and the Church in England. In these accounts, the bewitching Anne was indeed guilty of the crimes of which she was charged and was punished with a shameful death for her sins.

It is unfortunate that the sources concerning Anne's life are so polarised, for they strip away the queen's humanity, presenting her as a figure not wholly human. In the Protestant works she is saintly, whereas in Counter-Reformation histories she is less than human, a worshipper of the devil. Only with difficulty can historians navigate their way through the conflicting stories of Anne's life and reach a realistic understanding of Anne as a person and as a queen. The true story is a sinister one of fatal obsession rather than love.

Above: Hever Castle in Kent, where Anne Boleyn may have been born.

Anne was the younger daughter of the diplomat and courtier Sir Thomas Boleyn and his wife Lady Elizabeth Howard. While it is a myth that she was the most nobly born of Henry's English wives, her pedigree was impressive. On her mother's side, she was the niece of the Earl of Surrey and granddaughter of the Duke of Norfolk, while on her father's side she was related to the earls of Ormond. Anne's date of birth and birthplace are unknown. Traditionally it has been suggested that she was born either at Blickling Hall in Norfolk or at Hever Castle in Kent, but several of Anne's relatives were of the opinion that her birthplace was London, perhaps Norfolk House at Lambeth. The majority of modern historians favour a birthdate of circa 1501; however, the Elizabethan antiquarian William Camden confirmed that Anne was born in 1507, while the Duchess of Feria informed her biographer Henry Clifford that Anne had not yet reached twenty-nine years of age when she was beheaded in 1536.

Cardinal Wolsey himself allegedly referred to Anne in 1523 as a 'foolish girl', while Cardinal Reginald Pole described Anne as a 'girl' when Henry VIII fell in love with her. In 1534, a year after her marriage, Anne was described by the Imperial ambassador Eustace Chapuys as being 'in a state of health and of an age to have many more children'. While she could have had more children, the adjective 'many' is questionable if she were actually 33 or 34 years old. Finally, when Anne was sent abroad to the court of Margaret of Austria, she was described by the regent as being 'so pleasing in her youthful age'. In the sixteenth-century, children of the nobility and gentry were routinely sent to noble households at an early age to acquire an education. Sir Thomas, an ambitious and well-educated diplomat, surely had similar hopes for his daughter. Recognising that she was 'bright and toward', it is entirely credible that he arranged for her departure to Europe at the age of only six years old. Perhaps it was only in 1519 or 1520 that Anne formally served as a maid of honour.

From an early age, Anne would have been brought up to value her lineage. The Boleyns were not nobility, but they were an ambitious and enterprising family that had consistently married well. Sir Thomas's marriage to Elizabeth Howard had been a considerable achievement for him in that it allied the Boleyns with the Howards, the premier ducal family in England. The Howards, moreover, were closely linked to the Tudor dynasty, for Queen Elizabeth of York's younger sister Anne had married Thomas Howard, earl of Surrey and later duke of Norfolk. It is entirely credible that Anne Boleyn was named after her aunt.

Above: Margaret of Austria, duchess of Savoy (left) and Queen Claude of France (right). As a young girl, Anne Boleyn was closely acquainted with both ladies.

It is usually asserted that Anne's older sister Mary also accompanied her to France, but the list naming the maids of honour serving Mary Tudor when she married Louis XII of France in 1514 referred only to one 'M. Boleyn' rather than two. The initial 'M' referred to the title mistress rather than one's Christian name. A later inventory of ladies remaining in France referred to 'Mademoiselle Boleyn' which, again, almost certainly referred to Anne. Why Sir Thomas elected to send Anne rather than Mary to serve in the courts of Europe can perhaps be explained by the brightness and shrewd intellect that Anne already possessed. The ambitious Thomas was perhaps also hoping to wed Mary to a high-ranking English nobleman. Sending Anne abroad, rather than Mary, cannot necessarily be read as evidence of Thomas' preference for Anne or as evidence that Mary was intellectually inferior to her sister.

Anne's childhood in Europe profoundly influenced her worldviews and her inner character. Like Katherine of Aragon, she was acquainted with strong ruling women that were more than capable of governing kingdoms. Margaret of Austria was the shrewd regent of the Netherlands during Anne's stay there, and when Anne departed to France to serve Queen Mary she was acquainted with Marguerite de Navarre, sister of Francois I. The duke of Norfolk, Anne's uncle, was later to inform Marguerite that his niece was 'as affectionate to your highness as if she were your own sister, and likewise to the queen... My opinion is that she is your good and assured friend'. Two years later, in 1535, Anne herself informed Marguerite that 'her greatest wish, next to having a son, was to see you again'. While it is difficult to uncover the true nature of relations between Anne and Marguerite, it seems likely that the young Anne admired Marguerite. She was both an author and a patron of humanists and reformers. Her most famous work was Heptameron, which has been interpreted as a social and political critique, combining religiosity (pious dedication and high moral standards) with 'lurid voluptuousness'.

If Anne was influenced by Marguerite, then she would have grew to value her own ideas, to think critically of the world around her, and to place a great emphasis on inner piety and spiritual enlightenment. Anne also served Claude, wife of Francois I. Claude was renowned for her piety, virtue and goodness, and she did not encourage the licentious intrigues that pervaded the French court. As a favoured companion of the French queen, Anne would have understood that female virtue was her greatest prize. She likely came to understand her own worth and arrived at a deep understanding of herself as a woman. Influenced from a young age by strong women on the continent, including the capable Margaret of Austria, the sophisticated and educated Marguerite de Navarre, and the virtuous Queen Claude, Anne Boleyn grew up to be a remarkable woman.

She was not the most beautiful of women, but she had something more. She valued her own ideas, she read widely in secular and religious literature, and she developed an intense fascination with the reformed faith. Eric Ives has speculated that Anne underwent something of a religious enlightenment while in France, and it is certainly possible given her receptivity to the beginnings of the reformed faith that were developing across Europe. Anne also became a highly skilled musician, an excellent dancer and an intellectual with a keen interest in the Renaissance movement. Although she had not been groomed for queenship like Katherine of Aragon, she was in many respects a highly suitable candidate for royalty given her piety, her intellect, her sensitivity to the artistic movement and her interest in the Reformation. Moreover, she came from a fertile family and, while not blessed with outstandingly good looks, was physically attractive. The Venetian ambassador recorded that she was of medium stature, with a swarthy complexion, a wide mouth, and 'black and beautiful' eyes. Her brown hair was lustrous and long and her hands finely formed.

Anne returned to England late in 1521. Her father had arranged a most advantageous marriage for her to James Butler, later ninth earl of Ormond, in a bid to settle the Boleyn-Butler dispute over the title of Ormond. An ambitious young lady who had been educated to advance her lineage, Anne would surely have been aware of the advantages presented to the Boleyn family by the alliance with the Butlers. For reasons that remain unsolved, however, the marriage did not take place. Around this time Anne was appointed to serve Katherine of Aragon, first wife of Henry VIII, and alongside her sister Mary and former mistress Mary Tudor, she appeared in a court masque in March 1522 in the role of Perseverance. If George Cavendish, gentleman usher of Cardinal Wolsey, is to be believed, Anne soon afterwards became acquainted with Henry Percy, heir to the earldom of Northumberland and the two fell in love with one another. He wrote that 'there grewe such a secret love between them that at lengthe they were ensured together intending to marry'. Percy was captivated by Anne's 'excellent behaviour and gesture'. He regarded Anne as 'a convenient wife', informing the enraged Cardinal thus when Wolsey discovered the secret relationship between them. Percy described Anne as being 'descended of right noble parentage' which, in truth, she was. Heartbroken, Percy was forced to separate Anne, and she seems to have been sent from court in disgrace.

As an assertive, intellectual young woman who valued her own ideas and was interested in both the Renaissance and the Reformation, Anne Boleyn attracted admirers. At some point she attracted the king himself. It is a lingering myth that Anne deliberately set out to become queen, calculatingly ensnaring the unsuspecting king and seducing him in a bid to become queen of England. If anything, the evidence indicates the exact opposite, as recent research has demonstrated. Anne may have been in love with Henry Percy and, when the king of England fell in love with her, she might not yet have recovered from the heartbreak she had endured over Percy. A charismatic, attractive woman, she provoked dangerous obsession in men who became interested in her, one of whom was the king, and another of whom was the musician Mark Smeaton. Only in the realm of fiction have these obsessions been interpreted in a sinister light, but it is possible that fiction, in this case, mirrors reality.

For Henry's obsession with Anne was completely one-sided. She was not interested in becoming his mistress; neither did she, at least initially, wish to become queen. This perhaps is at odds with the admirable marital successes achieved by Boleyn ambition, but Anne had served several royal women on the continent and had been close to at least two of them. Her relations with Marguerite and Claude perhaps instilled in her a deep-seated loyalty to the traditions of monarchy. George Wyatt, a grandson of the poet Sir Thomas Wyatt, confirmed in his biography of Anne that she bare great 'love to the queen [Katherine] whom she served, that was also a personage of great virtue'. Loyal to Queen Katherine, and well aware that her sister Mary had been discarded by the king once her period as his mistress was over, Anne had no wish to become queen of England, and by ignoring the king's relentless stream of letters she likely hoped that he would leave her alone.

Above: Henry VIII wrote repeatedly to Anne beseeching her to become his love, but her replies were vague and she often neglected to reply, probably due to an earnest desire to be left alone.

However, Anne's behaviour served only to make the king more obsessive, often dangerously so. Nowadays his behaviour might be interpreted as stalking, which is what a handful of modern historians have interpreted it as. When she remained aloof, Henry reproached her by opining that her lack of enthusiasm 'seems a very poor return for the great love which I bear you'. She retreated from court to Hever and returned only in the company of her mother. Henry continued to entreat her 'earnestly to let me know expressly your whole mind as to the love between us'. Anne's replies, in reality, had not exactly suggested that she felt 'love' for him, as Henry disingenuously wrote. She surely knew that involvement with the king would constitute a betrayal of her mistress, and as Wyatt's evidence suggests, Anne was loyal to Katherine and had no wish to hurt her. Yet, in refusing to become Henry's mistress and in retreating from court in an attempt to escape his lust, Anne's situation only worsened. For the more she retreated, hoping that the king would respect her wishes to be left alone, the more his obsession was inflamed until it became fatal. Not, at this stage, fatal for Anne, but fatal for his kingdom and fatal for his first marriage. By the summer of 1527, Katherine was informed that her marriage was invalid on account of her previous marriage to Henry's brother Arthur. The king was certain that their lack of sons was because their marriage had offended God as an unclean union.

Whether Anne was prepared for what was to befall her cannot be known with certainty. When she danced with Henry at a reception for the French ambassadors in May 1527, the court became aware that it was Sir Thomas Boleyn's younger, sophisticated daughter who would replace the beloved Katherine as queen of England. Anne's life became much harder around this time. Queen Katherine was reportedly 'much beloved in this kingdom' and the king himself, despite his desire to annul his first marriage, was well-liked by the people and respected by his courtiers. Who to blame, then, for the royal marital crisis? Anne herself. With the passing of time, in the exaggerated dispatches of ambassadors, the whispers of courtiers and the murmurs of discontent across the kingdom, Anne was gradually endowed with enormous power that was regarded as unthinkable in a woman. Her power was heinous, dark, supernatural: it was whispered that she had cast a spell on the unsuspecting king, manipulating him with the promises of sexual fulfillment to put aside his long-suffering wife and marry her, a younger woman, instead. Endowed with this unnatural power, Anne was figured as a witch, an enchanting siren who resorted to poisoning her enemies (including Bishop John Fisher in early 1531) and threatening the life of the Queen (that same year apparently wishing that all Spaniards were at the bottom of the sea). In short, she became a scapegoat for the annulment and a scapegoat for the king's relentless lust.

Those who scapegoated her were ignorant of her admiration for Katherine, her love for Henry Percy and her insistent refusal to become involved with Henry. They either ignored, or were not aware, that Henry's obsession for her was lethal and could not be escaped from. She had sought to escape court, she had failed to reply to his letters, she had only given in after draining months of messages and gifts. She was an intelligent, shrewd and sophisticated young woman, but she placed great value on her own virtue and piety and had no desire to replace Katherine as queen. Whether her family respected her wishes and resigned themselves to the king's longing, or whether they actively encouraged her to cultivate his interest, cannot be known with certainty. But what seems clear is that Anne herself never set out to become queen and became the victim of a relentless campaign of hatred and lies beginning in the late 1520s and continuing to her death and beyond.

It is highly unlikely that Anne Boleyn had any initial desire to become queen of England. She sought to distance herself from Henry VIII's relentless obsession, but eventually resigned herself to her fate.

In truth, Anne's individual involvement in the stages leading to the annulment was minor. As Warnicke has asserted: 'It is possible Henry... had considerably more control over their relationship than is sometimes alleged'. In his letters, he was able to deny her suits and requests, while comforting her during her absence from court in 1528. However, even if she had no desire to become queen, Anne seems to have gradually understood that she was a position to further the reformed faith. The Spanish ambassador described her and her brother George as 'more Lutheran than Luther himself', but Anne continued to respect the revered rituals and traditions of Catholicism. She read the Bible in the vernacular and increasingly afforded support to reformed scholars. Thomas Cranmer, who later became archbishop of Canterbury, was a chaplain of her family. Cranmer was later to confirm that he 'never had better opinion in woman, than I had in her'. She was also highly charitable as queen. The martyrologist John Foxe, writing in the reign of Elizabeth I, recorded: 'Also, how bountiful she was to the poor, passing not only the common example of other queens, but also the revenues almost of her estate... Again, what a zealous defender she was of Christ's gospel all the world doth know, and her acts do and will declare to the world's end'.

Given her receptivity to learned ideas on the Continent and her years of experience serving pious, virtuous royal women, it does not seem likely that Anne was the loose-living, vulgar woman of popular legend and the vitriolic dispatches of Ambassador Chapuys. Describing her as 'the concubine' or 'the whore', Chapuys believed that her primary ambition was to cause harm to Katherine and Princess Mary, asserting: 'the King's mistress has been heard to say that she will never rest until he [Henry] has had her [Katherine] put out of the way'. He had earlier opined that 'Anne might be further encouraged to execute her wicked design'. And yet Chapuys consistently refused to meet Anne and had no way of knowing her inner thoughts or the details of her conversations with Henry. Indeed, other evidence indicates that she was initially loyal to Katherine and, as queen, she consistently wrote to her stepdaughter Mary promising her that she would enjoy a favoured position at court if she would recognise that her father's marriage to Katherine was invalid. Henry's first wife had angrily referred to Anne as 'the scandal of Christendom' because, like her subjects, she blamed her husband's mistress rather than the king himself for the decision to break with Rome and the annulment of her marriage. But it seems unlikely that Anne was so consumed with hatred towards Katherine and Mary as Chapuys makes out that she would relentlessly plot their deaths.

Anne was close to her brother George and seems to have enjoyed warm relations with her mother Elizabeth. Her relationship with her older sister is uncertain, but Julia Fox's biography of Jane Boleyn, Lady Rochford, intriguingly suggests that Anne was closer to her sister-in-law Jane than to her sister Mary. Although Antonia Fraser commented that Anne had no interest in developing close friendships with other women, Anne enjoyed a warm friendship with Elizabeth, Lady Worcester, and was initially on good terms with Lady Bridget Wingfield. She also concerned herself with the marriage of her young cousin Mary Howard, arranging an excellent alliance for her with Henry Fitzroy, Henry VIII's bastard son by Bessie Blount.

Anne's position during these years and during her queenship caused her grave anxiety. There is enough extant evidence to indicate that she never felt entirely secure in Henry's affections, while simultaneously revealing her to be a highly strung, anxious and occasionally fragile woman. At a banquet in January 1535 given in honour of the French alliance, Anne reportedly 'burst out laughing' upon seeing that her husband was engaged in conversation with a beautiful lady, bringing tears to her eyes. Upon news of Katherine's death in January 1536, Anne apparently withdrew to her apartments and wept because she feared that Katherine's fate would become hers. Although Chapuys absurdly stated late in 1535 that Anne 'now rules over, and governs the nation; the King dares not contradict her', Henry was always fully in control of his relationship with Anne, as demonstrated in his chilling reminder to her that he had the power to lower her. As with Katherine, Anne's queenship, in which she enjoyed noted successes as religious patron and as governor of her household, was undermined primarily by her failure to bear a healthy son. The queen had conceived soon after the birth of Elizabeth in the autumn of 1533, but probably gave birth to a stillborn child in the early summer of 1534. Anne was well aware that her position, and that of her daughter, remained uncertain. When the Admiral of France late in 1534 proposed a marriage alliance between Mary Tudor and the Dauphin, the queen was said to have reacted with 'anger', as well she might have, for it constituted a snub of her and her marriage. Having spent her childhood in France and having enjoyed good relations with the French ruling women, as a queen herself Anne might well have expected greater support from France.

Although it is unlikely that she had ever plotted Katherine's destruction, Anne might have felt relief upon hearing of her former mistress' death in early 1536. She herself was pregnant at the time and perhaps anticipated a secure future as queen were she to present her increasingly irascible husband with the much-desired male heir. Having lived in fear during Henry's dangerous obsession with her, Anne was perhaps now apprehensive that his obsession for her was dead and feared the resulting consequences. When she miscarried a son at the end of January, the die was cast. Henry's growing infatuation with Anne's attendant Jane Seymour only worsened the perilous situation facing the queen.

Above: The Chapel of St Peter ad Vincula at the Tower of London, where Anne Boleyn was buried in May 1536.

Only four months after her final miscarriage, Anne was executed at the Tower of London alongside her brother George Boleyn, Lord Rochford, Henry Norris, William Brereton, Francis Weston and Mark Smeaton on charges of adultery and conspiracy to murder the king. The speed of the queen's downfall astonished her contemporaries and has perplexed historians ever since. A variety of complex explanations for her demise have been proffered, including the birth of a deformed foetus to Anne (thus convincing her husband that she was a witch); a court conspiracy masterminded by Anne's former ally Thomas Cromwell in alliance with those hostile to Anne and loyal to Mary Tudor; the influence of foreign policy; and more recently, that Anne was guilty as charged. Perhaps what all of these explanations lack is the human side of the story.

Anne Boleyn's rise to queenship had occurred solely because the king of England had fallen dangerously, possessively, in love with her. His obsession for her had caused him to break with the Roman Catholic Church, annul his first marriage, and ruthlessly put to death those who opposed him, including his former friend Sir Thomas More and the aged bishop John Fisher, his own grandmother's chaplain and confessor. Anne had been blamed for all of this: by the English people at large, by foreign rulers in Europe, and by her former mistress Katherine and her daughter Mary. Only after Anne's brutal demise did they learn where responsibility for these momentous events truly lay. As mentioned, Anne's influence in the annulment proceedings was minor, and she exercised far less control, if any, in her relationship with Henry than is traditionally thought. She did not have the powerful protection of royal relatives abroad, as Katherine had.

The best explanation for Anne's demise was offered by Amy Licence in her biography of Henry's wives and mistresses:

Henry was ruthless in his personal relationships... Once-beloved favourites were rejected suddenly, almost overnight, being sent away from court with little warning, never to be seen again. Once he had made up his mind, he never went back. He could no longer tolerate their existence and had a need to close a door upon them... The greater the love he had felt for them, the greater the suffering he needed to inflict upon them... It appears that Henry had a need to punish Anne, to exact a complete revenge on her that owed less to her reputed crimes than to his own monocracy. Thus, as he had dictated the path of her rise, he had to end it decisively. He had controlled and shaped her as a mistress and queen; she was his subject, his plaything, and he could not resist imposing the ultimate authority when he had tired of the game.

Anne Boleyn was not the tyrannical, monstrous witch of Catholic propaganda or the wily seductress of popular culture. An intelligent, sophisticated and principled woman, she had sought to distance herself from Henry's relentless advances but had eventually capitulated. Once she had assented to his demands, there was no way out. Responsibility for the ill-treatment of Katherine and Mary, the break with Rome, and the brutal persecution of those who refused to recognise the king's supremacy as Head of the English Church lies entirely with Henry, not Anne. Once his obsession with her had ended, she faced a brutal death because she had not provided him with a son and because she had disappointed him. Henry's great joy at her downfall and execution, publicly displayed to his courtiers and ambassadors, is indicative of the price Anne paid for having the misfortune to attract a dangerous ruler whose obsessions proved lethal.

Published on October 23, 2015 07:25

October 22, 2015

The Stereotyped Six Wives: One: 'A Great and Strong-Laboured Woman'

Katherine of Aragon, first wife of Henry VIII of EnglandLifetime: 16 December 1485 - 7 January 1536Reigned: June 1509 - May 1533 (23 years, 11 months)Pregnancies: 6 Stillborn daughter: January 1510Prince Henry: 1 January 1511 - 23 February 1511 Stillborn son: September 1513Stillborn son: November 1514Mary I of England: 16 February 1516 - 17 November 1558Stillborn daughter: November 1518

In this new six-part series, I will be reexamining the lives and personalities of Henry VIII's six wives, seeking to portray their lives realistically in a process that discards prevailing stereotypes. Much scholarly work has been done on Henry's reign in recent decades, affording fresh insights into the politics and achievements of the period. Understandably, widespread interest in Henry's marital affairs remains unabated. Yet stereotypes continue to bedevil our knowledge of the wives of this most enigmatic king.

This first blog post examines the incredible life of Queen Katherine of Aragon, Henry's first wife. Married to Henry at the age of twenty-three, Katherine was both a princess of Spain and a queen of England. Her tenure as Henry's consort included notable achievements. Katherine successfully fulfilled the queenly role of intercessor and was an acknowledged ambassador for her home country. Her considerable achievements as queen are usually overlooked in the divorce crisis that concerned only the final six years of her reign, a fact that is often overlooked. She was Queen of England for almost 24 years and was a noted patron of the Renaissance in England. An examination of the sources concerning Katherine indicate that she was learned, charismatic, shrewd and formidable. Often depicted as the innocent, virtuous foil to the scheming Anne Boleyn, reality is rather different.

As the youngest daughter of the formidable 'Catholic Kings' Ferdinand and Isabella, who jointly ruled the Spanish kingdoms of Castile and Aragon, Katherine was expected to make an excellent marriage, but it was probably not anticipated at her birth that she would marry into the English royal family. At the time of Katherine's birth on 16 December 1485 at the Archbishop's Palace at Alcala de Henares, the Tudors had been on the English throne for less than four months. A newly established dynasty with a fairly weak claim to the throne, the Tudors were not regarded with especial confidence or admiration by other rulers in Europe. Ferdinand and Isabella, who had already ruled Spain for several years by this point, were shrewd and confident rulers and could be forgiven for regarding King Henry VII with wariness. Perhaps they wondered how long he would hold the turbulent throne. Given that England had been in a state of dynastic turmoil since the mid fifteenth-century, they could have been forgiven for thinking this.

Katherine was educated by a clerk in holy orders, Alessandro Geraldini. The Dutch humanist Erasmus later recorded that the princess was 'imbued with learning, by the care of her illustrious mother'. She learned languages (though not English, and she only acquired a knowledge of French several years later); canon and civil law; theology; philosophy; history; and arithmetic, but was also brought up with an excellent knowledge of skills deemed appropriately feminine: housewifery; embroidery; lacemaking; and music. At a time when the Renaissance was beginning to develop across Europe, the Spanish monarchs likely placed great emphasis on their daughter acquiring musical talent. As queen, Katherine was to enjoy participating in masques and dances. Perhaps most importantly, Katherine was brought up with an intense devotion and loyalty to the Roman Catholic Church. Her parents had determinedly enforced the Roman faith across their dominions, finally expelling Jews and Moors who refused to convert. Not for nothing were Ferdinand and Isabella granted the title Catholic Monarch by the satisfied pope Alexander VI. From an early age, Katherine came to regard any religion that was antithetical to the Roman faith as heresy. Given the determination with which her parents sought to expel heretics from their kingdoms, it is highly likely that Katherine was imbued with a passionate hatred of what she perceived as heresy and an instinctive intolerance for heretics.

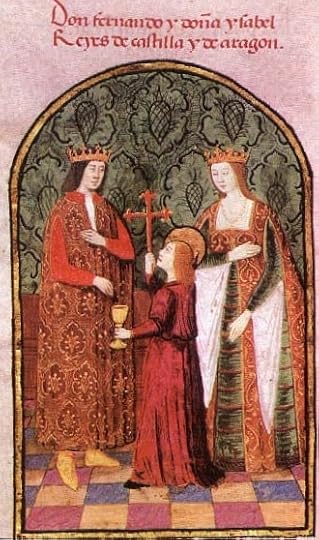

Above: Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile, the parents of Katherine of Aragon. Their active rule, which involved the determined expulsion of heresy from their kingdoms, likely had a significant influence on Katherine, inspiring her to regard heresy with revulsion while encouraging her to revere and loyally serve the Roman Catholic Church.

Above: Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile, the parents of Katherine of Aragon. Their active rule, which involved the determined expulsion of heresy from their kingdoms, likely had a significant influence on Katherine, inspiring her to regard heresy with revulsion while encouraging her to revere and loyally serve the Roman Catholic Church.The influence of Katherine's parents on their daughter's development should not be underestimated. Their shared, active rule would have signalled to Katherine that a queen could exercise tremendous influence alongside her husband in ruling a kingdom. Katherine was not brought up in England, revering the queenly model in place there: a compliant, devoted and virginal wife and mother. While she was brought up to regard these qualities as essential to successful rulership, she would also have learned that a queen consort could be active, even militant, in working alongside her husband to successfully rule. As a young girl, Katherine of Aragon's model of queenship was one that was active, determined and militant. It was also one that was fiercely intolerant of threat, whether religious or political, and one that was grounded in loyalty to one's lineage and devotion to one's faith.

Katherine grew to be both beautiful and charming. She was reputedly tiny in height, probably less than five foot tall, and her hair was long and auburn in colour. Sir Thomas More, who was to become Katherine's close friend and admirer, wrote in her praise: 'There is nothing wanting in her that the most beautiful girl should have. Everyone is singing her praises'. She was also learned and intelligent, with an interest in the burgeoning Renaissance movement and a devotion to the Roman Catholic Church: in short, she appeared the perfect queen consort for a young king. Aware of this, and determined to extend Spanish power outwards into Europe to diminish the hostile influence of France, Ferdinand and Isabella decided to marry their youngest daughter into England. She was betrothed to the English king's eldest son Prince Arthur. Given that interest in the match had first been mooted in the spring of 1488, when Katherine was only two years of age and her betrothed not yet two, it is unsurprising that Katherine came to regard herself as divinely appointed by God to be England's queen. It was her destiny. With a fierce devotion to the Catholic faith, combined with a deep-seated loyalty to her lineage, it must be borne in mind that Katherine regarded herself from infanthood as the Queen of England. Only in death could God could take that title from her.

Even at an early age, then, Katherine was never the submissive, silent and passive consort presented in Victorian historiography and even in some modern works of history. She was an energetic, determined and resourceful woman who was appointed by God to rule England. While she would have learned from her mother that a queen's primary task was to provide male heirs with which to secure the dynasty's continuation, her mother's example also educated her daughter to believe that a queen's role in the politics of the kingdom was as important as that of her husband. Her role was active, not passive. Indeed, it is questionable whether Katherine actively cultivated a submissive ideal of womanhood that was later associated with her successor, Jane Seymour, so it is perhaps surprising that she is often identified with this role. As will be seen, she perhaps reacted more negatively and forcefully to Henry VIII's infidelities than is often assumed, and she certainly was not averse to losing her temper publicly.

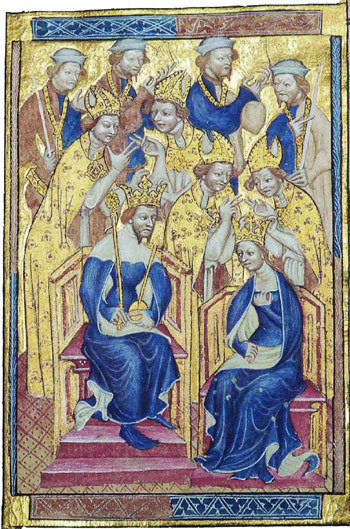

Brothers: Arthur, Prince of Wales (left) and Henry, Prince of Wales (right); later Henry VIII. Both men married Katherine of Aragon.

Brothers: Arthur, Prince of Wales (left) and Henry, Prince of Wales (right); later Henry VIII. Both men married Katherine of Aragon.

In November 1501, at the age of fifteen, Katherine of Aragon wed Arthur Tudor, prince of Wales, at St. Paul's Cathedral in London. Katherine was acquainted with her new family around this time. She reportedly enjoyed warm relations with her mother-in-law Queen Elizabeth of York, the shrewd and kindly wife of Henry VII, and she undoubtedly regarded her bridegroom's grandmother, Lady Margaret Beaufort, with respect. Like Katherine's mother Isabella of Castile, Lady Margaret was a determined and active woman who ruled her estates vigorously and exercised considerable influence at court. Contemporary ambassadors whispered rumours that she even held her daughter-in-law, the Queen of England, in subjection. Katherine would have learnt from this state of affairs that a royal woman's power and influence at the English court was potentially considerable. She may also have considered Elizabeth's situation and determined that no woman would ever oust her from a position of influence, whether that woman was family or not.

After their marriage, the prince and princess of Wales (as Katherine was now known) were sent to reside at Ludlow Castle, Arthur's ceremonial centre of power in the Welsh Marches. Traditionally, it has been argued that Katherine's marriage to Arthur was not consummated and, when the prince tragically died in the spring of 1502, the princess was left a virgin widow. However, David Starkey recently suggested that the marriage was indeed consummated. Certainly no-one at the time doubted that it had. When her marriage was threatened in 1527 by Henry VIII's determination to remarry, Katherine had every reason to lie. Not only was her position as queen endangered, but her daughter's future could be jeopardised were the princess to become a bastard. Moreover, Arthur was not the unhealthy, sickly teenager of popular legend, but a vigorous youth. Katherine's mother would have educated her about the necessity of consummating a union, to prevent doubts arising as to its legitimacy. The Catholic Church taught that a marriage could be annulled on the grounds of non-consummation, as the failed union of Henry VIII and Anne of Cleves was to prove. Given both her pride and loyalty to her lineage, and her intense devotion to her Roman Catholic faith, it seems unlikely that Katherine failed to consummate her marriage to Arthur.

Above: Ludlow Castle in Wales, where Katherine probably consummated her marriage to Arthur, Prince of Wales.

Above: Ludlow Castle in Wales, where Katherine probably consummated her marriage to Arthur, Prince of Wales.

Whether Katherine truly loved her first husband is uncertain, but her determination to become Queen of England did not die with her husband in April 1502. During her seven years of widowhood, Katherine continued to exert a forceful and vigorous presence in European politics. She regularly wrote to her parents, especially her father following the death of her mother in late 1504. Katherine informed Ferdinand that she had 'no other hope or comfort in this world' unless he wrote to her regularly. The evidence of her letters indicates that she sought to influence her father's policy, as seen in her insistent determination to have the Spanish ambassador de Puebla expelled for the 'pain and annoyance' which he had caused her, perhaps principally on account of his failure to promote her wellbeing and interests at court. She also pressured Henry VII, her father-in-law, to remember 'his daughter' and to remember that 'it will reflect dishonour upon his character if he should entirely abandon' her. Katherine's entreaties were genuine, but were also calculating. She sought to remind the English king of her position as princess of Spain and, thus, her central importance in European affairs as a prospective consort to a foreign ruler. She surely rejoiced upon learning that she was betrothed to her former husband's younger brother Henry Tudor, but whether she knew of his decision to revoke his promises to her is unknown. Certainly it would not have altered her firm belief that she would one day rule England as its queen.

Her health, however, soon became a matter of concern. Historian Giles Tremlett has speculated that the princess may have suffered from an eating disorder, although it is unwise to refer it as such in the modern sense of the term. Certainly Katherine's zeal for fasting and abstinence was famed across Europe. The Pope himself became so concerned that he issued a missive instructing that if Katherine's 'devotions and fasting' were 'thought to stand in the way of her physical health and the procreation of children', then they could be 'revoked and annulled by men'. Katherine's desire to fast is highly indicative of the importance she placed on loyally and devotedly serving the Roman Catholic faith. In her eyes, alongside her destiny as Queen of England, it was the fundamental reason for her existence.

Even as her fortunes experienced strain, during these years Katherine's belief in her God-given destiny as Queen of England remained rock-solid. If anything, the experience of adversity hardened her and accustomed her to fighting for what she regarded as her birthright. Moreover, the experience of success positioned her to regard her cause as just, certain of triumph. That success came in the summer of 1509 when, following Henry VII's death, the teenaged Henry VIII of England chose to wed Katherine. He was reputed to regard her with 'singular love', but it is also equally likely that he wished to preserve the Spanish alliance in the face of French hostility. The Tudor claim to the throne remained fragile, as the lingering fear of the White Rose proved.

Above: Katherine of Aragon's only surviving child, Mary, born in 1516.

Above: Katherine of Aragon's only surviving child, Mary, born in 1516.

It is unfortunate that Katherine of Aragon tends to be regarded in popular culture as dowdy and dull, given that she was beautiful, elegant and sophisticated in her early years as England's queen. She dressed exquisitely and was reputed to be 'a ceremonious woman in her attire'. Alongside her handsome, auburn-haired husband, Katherine represented a triumphant figure presiding over the cultured English court. God certainly seemed to smile on their union, as were the people at large who rejoiced 'in the possession of such a King'. Katherine immediately became pregnant and was delivered of a stillborn daughter in January 1510. Yet Henry was not overly concerned, writing to his father-in-law Ferdinand of the 'joy and felicity' which he had experienced in marrying the charming Katherine. 'In high health, with the greatest gaiety and contentment that ever there was', it is hardly likely that the queen was overly concerned too. She had triumphed after years of hardship and adversity, and was supremely confident that God favoured her and would reward her devotion to the faith with the birth of sons.

Despite the success of their marriage, Katherine's father had reputedly been unfaithful to his wife, and Katherine would likely have learned from an early age that kings were accustomed to taking lovers. However, that does not mean that she regarded extramarital liaisons with approval or even acceptance. Given her devout adherence to Roman Catholicism, it is rather more likely that she regarded adulterous affairs with horror and revulsion. So when Henry took Lady Anne Hastings as his lover within a year of marrying Katherine, it is not entirely surprising that the queen was said to be highly 'vexed' with her husband. She confronted him about his seduction of her lady-in-waiting and was to later show a marked disapproval of his decision to award his bastard son Henry Fitzroy with two dukedoms. While Katherine did not cause tantrums, she certainly did not necessarily acquiesce to Henry's extramarital affairs submissively or ignorantly. It is far too simplistic to interpret her behaviour in this light, as the majority of historians have done. An energetic, shrewd and determined consort, and mindful of her admirable lineage, she perhaps rationalised that such affairs were beneath her. Her primary duty was to bear sons, and if she did so, then no lady-in-waiting, no matter how beautiful or sophisticated, could threaten her.

Above: Mary Boleyn, mistress of Henry VIII. While we have no direct evidence for Queen Katherine's opinion of the woman who supplanted Bessie Blount in her husband's affections, it seems too simplistic to view Katherine as submissively ignoring Henry's adulterous affairs.

Above: Mary Boleyn, mistress of Henry VIII. While we have no direct evidence for Queen Katherine's opinion of the woman who supplanted Bessie Blount in her husband's affections, it seems too simplistic to view Katherine as submissively ignoring Henry's adulterous affairs. Aside from the royal couple's failure to have a healthy son, Katherine's queenship was largely triumphant. She enjoyed notable achievements that have often been overlooked in the focus on the 'great matter'. Not only was she a loyal ambassador of her homeland, but she was her husband's chief advisor and confidant during his early years as king. In the summer of 1513, while campaigning in France, Henry accorded his wife the supreme honour of granting her the position of regent in England. Katherine, who was well aware that the queen's role could be active and forceful rather than silent and submissive, took on this position with enthusiasm. When the Scots invaded in the autumn, she energetically mustered her troops and rallied her forces. Katherine herself declared to her husband that she was 'horribly busy with making standards, banners and badges' for the cause. The queen travelled to Buckingham and urged the English forces to victory. They were inspired by Katherine's enthusiasm and courage and resoundingly defeated the Scots at Flodden on 9 September 1513. Triumphant, Katherine wrote to her husband: 'To my thinking, this battle hath been more than should you win all the crown of France'. She also hoped that Henry would shortly return to England because of the 'joy' it would bring both her and his subjects. Katherine's confidence has often been interpreted negatively by historians, who view her as crowing and inconsiderate of Henry's feelings, in seeming to accord her victory more importance than his own triumphs in France. However, Katherine would not have regarded it that way. Her mother had been as active, as militant and as successful as her father, and Katherine would have seen no reason why she could not achieve the same greatness that Isabella had. Moreover, the English queen was pregnant during these events and although the stillbirth of her son barely a week later would have caused her sorrow, she perhaps tempered this loss with the knowledge that God had continued to smile on her by granting her an unforgettable victory on the battlefield.

Because she regarded her queenship as active and a position to be approached with consideration and respect, Katherine took on the duties of her role with enthusiasm and diligence. She was a noted intercessor and earned considerable popularity in England for her success in this sphere. Following the aftermath of the May Day riots in 1517, when the London apprentices had violently turned on the foreigners of the city, the queen begged her husband with tears in her eyes to 'spare the apprentices' from execution. Willingly, Henry acceded to her request. This incident provides further evidence of Henry's love for his wife. He later admitted during the annulment proceedings that 'if I were to marry again, I would chose her above all women' for her 'gentleness, humility and buxomness'. Katherine's influence at court extended to matters of religion; she was also known to be charitable and provided alms for the poor. Presenting herself carefully as submissive, virtuous and pious, her husband and close friends were aware that she was vigorous, determined and resourceful, particularly when it came to a crisis.

By the spring of 1527, Katherine experienced her first real crisis as queen. Eighteen years on the throne had enabled her to grow into a confident, shrewd and experienced queen who was more than comfortable in affairs of state and promoting the interests of her homeland. She had watched as Henry's lovers had come and gone. Although she did not regard his affairs with approval, and had reacted furiously when his bastard by Bessie Blount had been granted unprecedented honours in 1525, Katherine shrewdly remained calm. She had witnessed her father's infidelities and continued to believe that, since God had ordained for her to become queen, she would remain Henry's wife until the day she died. In 1516, she had given birth to her only surviving daughter Mary. Katherine exercised undoubted influence in her daughter's education, for she was determined to ensure that her daughter was an active and successful queen just as her mother and grandmother had been. The Spanish humanist Juan Luis Vives had been appointed as her tutor, and Mary was brought up to be a virtuous Christian maiden. Katherine's devotion to the Catholic faith grounded her approach to her daughter's upbringing, and Mary's intense piety was undoubtedly instilled in her from birth by her formidable mother.

Above: Peterborough Cathedral, where Katherine was buried in 1536.

Above: Peterborough Cathedral, where Katherine was buried in 1536.

Katherine's queenship had been active, resourceful, even militant. She had always been at the centre of politics and had never shied from exerting influence in matters of state. During the annulment crisis, Katherine refused to accept that she was no longer Queen. As she perceived it, she had been educated from the age of two to regard herself as England's queen. No earthly being, even her husband, could take it from her. Only God could by calling her to Heaven. It was her destiny to be Queen, just as it was her daughter Mary's destiny someday to be Queen in her mother's place. By daring to put her aside, Henry was endangering not only his immortal soul but the wellbeing of England. Several modern historians have interpreted Katherine as disloyal to English interests, but she was in fact highly concerned with England's future and interpreted Henry's selfish desires as grossly antithetical to the future harmony of England.

She had been groomed from birth to regard heresy as mortally dangerous. It was an infection, a blight on the kingdom and a warning from God. The annulment was heretical, for it was closely associated with the reformed religion. Katherine and her supporters, including the Spanish ambassador Eustace Chapuys, were united in their belief that the reformed faith was Lutheran heresy and offensive to God. Katherine's parents had militantly stamped out heresy in their dominions and their daughter was determined to do the same in her adopted home. In no sense could she have stepped aside for her husband. Not only was he, in her eyes, endangering her position as queen and threatening their daughter's future, but he was tacitly granting acceptance to newfound heresy and thus calling into question the very foundations of society, as proven by the favour he bestowed on the Boleyns, whom Katherine knew were inferior to her in birth. By preferring them to Katherine, whose lineage was prestigious and renowned across Europe, Henry's behaviour ran dangerously close to questioning God's will.

Katherine's behaviour during her years of widowhood (1502-9) had been resourceful, energetic and determined. She had not remained silent, but had issued urgent letters to her father, ambassador, friends and her aloof father-in-law Henry VII, demanding for her wellbeing to be respected and her fortunes to be restored. As then, her role during the annulment crisis was formidable. She magnificently rose to the challenge presented her and upbraided Henry at the Blackfriars court in the summer of 1529 for daring to put her aside, asking him how she had offended him and daring him to assert that he had not found her a virgin at their marriage. All the evidence demonstrates, from her position as Princess of Wales to a threatened Queen of England, that Katherine of Aragon responded magnificently to a threat. Her offensive was calculating and determined. Not only was she fighting for her daughter's future, but for her country's wellbeing.

Above: Margaret of Anjou, queen of England.

Above: Margaret of Anjou, queen of England.

Margaret of Anjou, the courageous wife of Henry VI, had been described as 'a great and strong-laboured woman, for she spareth no pain to sue her things to an intent and conclusion to her power'. The same might in fairness be said of Katherine of Aragon. The first wife of Henry VIII was perhaps the toughest and was certainly the one who felt most confident in taking on her husband and reminding him of his responsibilities as king. She had not reacted submissively to his extramarital affairs, but had dared to reproach him for his affairs with Anne Hastings and Anne Boleyn, and when he promoted his bastard son's interests to the detriment of his legitimate daughter's position, she protested so vigorously that she was punished with the removal of several of her ladies-in-waiting.

In popular culture, Katherine continues to be perceived as the virtuous and silently suffering foil to the scheming, manipulative Anne Boleyn. This interpretation is both skewed and inaccurate, and marks a betrayal of Katherine's memory, failing to understand the real woman for who she truly was. Katherine was a determined, passionate adherent of the Roman Catholic faith and viewed other religious persuasions as dangerous heresy that required elimination at all cost. She was a courageous defender of the country's interests and was prepared to lead her troops, valiantly urging them on to destroy England's enemies. An energetic, stubborn and formidable queen, she was capable of deceit. She had probably lied about the consummation of her first marriage, perhaps lied about her pregnancy in 1510 to her father, and was capable of bloodthirstiness - as her desire to send her husband the brutally mangled body of James IV proves. Yet she was also interested in the Renaissance, was unswervingly loyal to her friends and relations, and was deeply concerned to promote the welfare of her people. It is misleading to regard Katherine as a perfect saint, a wronged wife and a silently suffering mother. She, like Margaret of Anjou, was 'a great and strong-laboured woman' who never once shied away from promoting her interests at all costs, while valiantly fighting to destroy all threats to her position, whether religious, political or dynastic.

Published on October 22, 2015 13:19

October 9, 2015

England's Queen Annes

It has been reported that an upcoming film about machinations at the court of Queen Anne of England, entitled The Favourite, will star Olivia Colman as the last Stuart monarch, Kate Winslet as the queen's intimate friend Sarah Churchill, duchess of Marlborough, and Emma Stone as Abigail Masham, favourite of the queen. What better time, then, to look at the women named Anne who rose to the position of queen of England?

Anne of Bohemia (1366-1394), consort of Richard II

Reigned 1382-1394.

Reigned 1382-1394.

Anne of Bohemia was the eldest surviving daughter of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles IV and his fourth wife Elizabeth of Pomerania. One of the more shadowy of England's medieval queens, Anne was reputed to be kind, charitable and was popular among her English subjects. The chronicler of Evesham described her thus: 'This queen, although she did not bear children, was still held to have contributed to the glory and wealth of the realm, as far as she was able. Noble and common people suffered greatly at her death'. On 20 January 1382, at the age of fifteen, Anne married Richard II of England. Her new husband was strikingly handsome, charismatic and intelligent; but he had a cruel streak and was known to be volatile, unpredictable and at times careless. The marriage was not particularly popular among the English nobility. Anne did not bring a dowry with her and the diplomatic advantages of the match were not regarded particularly favourably. As soon as she had disembarked in her new kingdom, Anne's ships were reportedly smashed to pieces - a troubling omen for superstitious observers. Despite these undercurrents of discontent, both nobles and commons alike came to regard Anne positively. She was a noted intercessor with her husband, procuring pardons for rebels involved in the Peasants' Revolt of 1381, and interceded for both John Northampton (a former mayor of London) and the citizens of London in the ceremonial reconciliation in 1392 between king and city. However, Anne failed to fulfil the most important duty of a queen consort: childbearing. There is no evidence that she was ever pregnant, leading some historians to speculate that Richard had agreed at his marriage to fulfil a vow of chastity. Anne died in 1394 at Sheen and her grief-stricken husband ordered the building destroyed. She was buried at Westminster Abbey, where her husband later joined her upon his death.

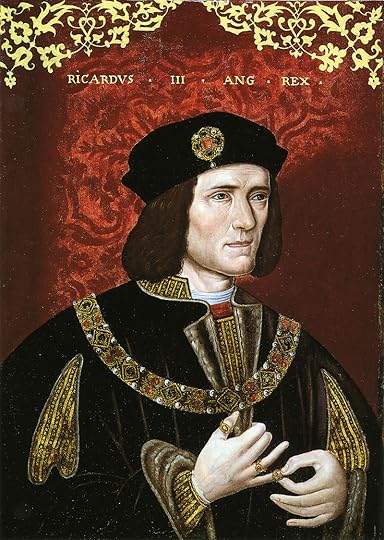

Anne Neville (1456-1485), consort of Richard III

Reigned 1483-1485.

Reigned 1483-1485.

Lady Anne Neville was the younger daughter of Richard Neville, sixteenth Earl of Warwick and Lady Anne de Beauchamp. Born at Warwick Castle, Anne's family was the premier noble family in the north of England. She spent her childhood at Middleham Castle in Yorkshire, residing with her kinsmen George of York and Richard of York (later to become her husband). In 1461, at the age of five, Anne's kinsmen Edward earl of March became King Edward IV. In 1469, Anne's sister Isabel wed George duke of Clarence. Although her family was now closely tied to the ruling House of York, Anne's fortunes were to change drastically. Her father, immortalised as the 'Kingmaker', changed sides because of his disaffection and supported the return of the defeated Lancastrians. In 1470, at the age of fourteen, Anne was betrothed to Edward of Westminster, the only son of Henry VI and Margaret of Anjou, and was married to him later that year at Angers Cathedral, thus becoming Princess of Wales. How she felt about her husband we can only speculate; but given that Anne had been educated from birth to regard the Lancastrians as immoral, corrupt and deficient rulers, it cannot have been easy for her to suddenly regard the heir to the Lancastrian throne, her husband, with respect or affection. However, Anne's fortunes were to change again. In the spring of 1471, her former brother-in-law Edward IV returned from exile and seized the throne once more from the inept Henry VI, who was put to death in the Tower of London in May. This was a traumatic time for Anne. Her father was killed at the Battle of Barnet and her husband was killed at the Battle of Tewkesbury. Before her fifteenth birthday, the younger daughter of Warwick had lost both her husband and her father; her grief and inner turmoil can only be imagined. Richard of Gloucester, younger brother of Edward IV, was determined to wed her; whether out of genuine affection or shrewd ambition, we cannot say. Richard's brother Clarence opposed the match because he desired the entire Warwick inheritance, rather than splitting it with his brother. Anne and Richard, however, escaped Clarence's clutches and wed in the spring of 1472. A year after her first husband's death, Anne became Duchess of Gloucester, equal in rank to her sister. Perhaps in 1476, Anne gave birth to her only son Edward. Upon the death of Edward IV in 1483, Richard of Gloucester seized the throne and was crowned as King Richard III at Westminster on 6 July alongside his wife. He had usurped it from his nephew Edward V; whether Edward and his brother were put to death on Richard's orders, or escaped abroad, or were incarcerated for the rest of their lives is an issue that continues to arouse passionate debate. In the spring of 1484, Anne's son died while still an infant. She was not to bear any more children. She died on 16 March 1485. Rumours alleged that Richard had poisoned her in order to wed his niece Elizabeth of York, but he declared publicly that these rumours were false and that he had always loved Anne.

Anne Boleyn (c. 1507-1536), consort of Henry VIII

Reigned 1533-1536.

Reigned 1533-1536.

Anne Boleyn was the younger daughter of Sir Thomas Boleyn and Lady Elizabeth Howard. She was most likely born in 1507 at Blickling Hall in Norfolk or Hever Castle in Kent, although later evidence indicates that her birthplace was London. Anne departed for the Continent in 1513 and served both Mary Tudor, queen consort of France, and Claude, wife of Francois I of France. She may also have known Marguerite of Alencon, Francois' sister. Anne was reputed to be charming, intelligent and witty and acquired an excellent education abroad. She was of medium height, with long dark hair, sparkling brown eyes, a wide mouth and elegant hands. Surviving evidence suggests that she was a skilled musician, a talented linguist and a shrewd intellectual with a fervent interest in the reformed faith. Anne returned to England to wed her relative James Butler, but the match did not come to fruition, and it is possible that she fell in love with Henry Percy, later sixth earl of Northumberland, and hoped to wed him. However, in 1526 or 1527 Henry VIII fell passionately in love with Anne and, after she refused to become his lover, proposed marriage to her. In 1533 she was crowned Queen of England upon the dissolution of his first marriage to Katherine of Aragon, and gave birth to Elizabeth in September. Hostile observers at court portrayed the new queen as a vindictive, cruel and outspoken woman who encouraged her husband to mercilessly kill his enemies, including his own daughter. These writers also claimed that Anne was responsible for the spread of heretical ideas. While Anne was undoubtedly an evangelical, she was not interested in the more extreme forms of Protestantism, and continued to favour traditional Catholic ideas such as the importance of good works. Anne was a charitable queen and concerned herself with education, providing generous assistance to the universities of Oxford and Cambridge. However, like Anne of Bohemia, she failed in her principal duty: to give birth to a son. In the spring of 1536, for reasons that remain mysterious and unfathomable to modern historians, the queen fell from favour and was arrested and imprisoned in the Tower of London alongside seven men, including her brother George Boleyn. She was found guilty of adultery and treason and was executed within the Tower walls on 19 May, and was later buried at the chapel of St Peter ad Vincula. Biographers and historians writing in the reign of her daughter Elizabeth stressed Anne's important contribution to the Elizabethan political and religious establishment, and were united in their belief that she was not guilty of the crimes for which she was put to death.

Anne of Cleves (1515-1557), consort of Henry VIII

Reigned 1540.