Simon Johnson's Blog, page 46

January 20, 2012

What Do Companies Do with Their Political Spending?

By James Kwak

Whatever they're doing, it doesn't seem to be good for shareholders. That's one conclusion of a new paper by John Coates, a Harvard law professor, which I discuss in today's Atlantic column (which originally misdated the Citizens United decision, thanks to some faulty proof-reading by me). Coates compares firm valuations with levels of lobbying and contributions by corporate PACs and finds that, outside of heavily regulated industries where everyone lobbies heavily, political activity is associated with lower firm value—implying that it's more like a CEO perk than like a good investment from the shareholder perspective.

January 19, 2012

Department of "Duh"

By James Kwak

The Times has a story out today: Surprise, all the Republican candidates' tax plans increase the national deficit! The numbers (reduction in 2015 tax revenues, from the Tax Policy Center):

Romney: $600 billion

Gingrich: $1.3 trillion

(Late lamented) Perry: $1.0 trillion

Santorum: $1.3 trillion

I guess that makes Romney the "fiscally responsible" choice, at least among the Republicans. But President Obama's tax proposals would only reduce 2015 tax revenues by $222 billion. (That's $385 billion in Table S-4 less $163 billion in Table S-3.)

Second surprise: The big winners in all of these tax plans are the rich! (That's not just in dollars, but in percentage increase in after-tax income.)

I don't mean to be hard on the Times reporters. This is exactly the kind of story they should be writing. Someone has to point out that the same people who are complaining about deficits are proposing to vastly increase those deficits. Especially when their fantastic claims are essentially going unchallenged on the campaign trail.

The Price of Apple

By James Kwak

Last week, This American Life ran a story about the Chinese factories that produce Apple products (and a lot of the other electronic devices that fill our lives). It featured Mike Daisey, a writer and performer who traveled to Shenzhen, China, to visit the enormous factories (more than 400,000 people work at Foxconn's, according to the story*) where electronic products are churned out using huge amounts of manual labor.

I'm sure that most of us already realized, on an intellectual level, that the stuff we buy is made by people overseas who, in general, have much less than we do and work harder than we do, under tougher working conditions. It's harder to ignore, however, listening to Daisey talk about the long shifts (up to thirty-four hours, apparently), the crippling injuries due to repetitive stress or hazardous chemicals, the crammed dormitories, and the authoritarian rules. At one point an interviewee produces a document, produced by the Labor Relations Board (with the name of the Board on it): it's a list of "troublemakers" who should be fired at once.

The question that Ira Glass asks at the end is how we should feel about all of this. Although Apple is at the center of the story—at one point Daisey shows his iPad to a man whose hand was destroyed by a machine that makes the iPad, and he called it a "thing of magic"—they seem to do a reasonable job of policing their suppliers and insisting on improvements to working conditions, at least compared to other companies. But still the number of violations doesn't go down from year to year.

Glass quotes Paul Krugman talking about how sweatshops (in Indonesia, I think), though brutal, were still better than the alternative for the people working in them, and how they contributed to economic development. He also interviews Nicholas Kristof, who agrees that working in these factories is often better than working in rice paddies—especially for young women, who can earn more money and thereby improve their bargaining power. But is that enough? Daisey doesn't think so.

I have a MacBook Pro and an iPad (and an LG phone, and a Samsung monitor, . . .). While I think OS X is far better than Windows (or Linux if, like me, you're not a power user), I would gladly switch back if I had confidence that my computer's manufacturer was an appreciably, demonstrably better employer than Foxconn. And I would pay more, too, just like I pay more for free-range eggs and organic food (which I buy for the environmental impact, not the health benefits). But while there are certification programs that provide some confidence that your coffee isn't the product of imperial exploitation, I'm not aware of such programs for electronics. Maybe there are already, and I just don't know about them.

Given that anyone buying Apple products is already paying a hefty price premium, you would think at least some of us would rather pay that premium for better labor protections.

* The TAL staff fact-checked everything they could fact-check in the story, and found only one small error (having to do with the size of the cafeterias).

January 18, 2012

Correlation, Causation

By James Kwak

XKCD (blacked out until tomorrow).

Economix has a table listing undergraduate majors by the percentage of graduates in each major that are in the "1 percent" (by income, which I think is less important than by wealth). The data are interesting, but I don't think it's correct to say that "the majors that give you the best chance of reaching the 1 percent are pre-med, economics, biochemistry, zoology and, yes, biology, in that order."

All of the pre-med/life sciences majors (numbers 1, 3, 5, 8, and 11 on the list) do arguably increase your chances of making the 1% because they help you become a doctor, and many specialists are in the 1%. Of course, since many science majors are considered more difficult by undergraduates, you could argue that the inherent traits people bring to college are just as important as the majors they choose. Economics is #2, but that's in part because many of the people who want to be in the 1 percent major in economics.

But the interesting cases are art history (#9), area studies (#12), history (#14), and philosophy (#17), all of which are disproportionately represented in the 1%. (History, for example, ranks right behind finance.) I don't think anyone would argue that knowledge of art history is likely to earn you a high income; there just aren't that many executives at Sotheby's and Christie's. I think what's going on is that these are the kinds of things that people study at elite schools—in particular, if you're not that worried about what you're going to do after graduation. These are not the things that most people at normal schools study. In 2009, for example, art history didn't even show up on the list of majors (it's probably tucked into "liberal arts and sciences, general studies, and humanities," which came in 11th), area studies was one of the least popular majors, and so was philosophy.

So there are two possible reasons why these people make the top 1 percent. One is that they are talented, hardworking people who succeed (financially) despite what they majored in—but then why are talented, hardworking people overrepresented in these majors? The other is that they are children of the elite who go to elite schools, study whatever they feel like, and succeed because of their upbringing and connections. (The reasons are not mutually exclusive.) Given the increasing evidence that America, the land of opportunity, is actually one of limited social mobility, I think we can't overlook the latter explanation.

The End of the Blog?

By James Kwak

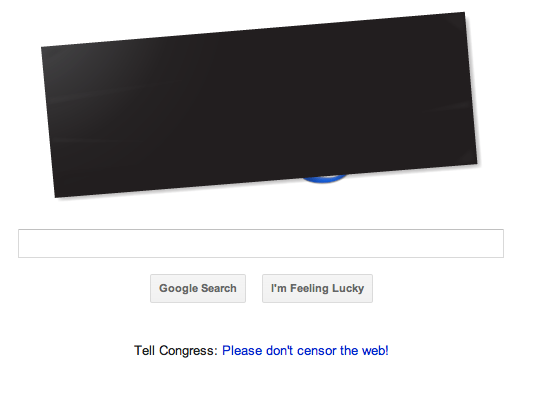

As you may have noticed by now, Wikipedia's English-language site is (mostly) down for the day to protest SOPA and PIPA, two draconian anti-copyright infringement laws moving through Congress, and Google's home page looks like this:

Under existing law (the DMCA), if someone posts copyrighted material in a comment on this blog, the copyright holder is supposed to send me a takedown notice, after which point I am supposed to take the material down (if it is in fact copyrighted).

SOPA and PIPA are bills in the House and Senate, respectively, that make it much easier for "copyright holders" (like the big media companies that back the bill—or, come to think of it, authors like me) to take action not only against "bad" web sites that make copyrighted material available (against the wishes of the copyright holders), but also against web sites that simply link to such "bad" web sites. For example, the copyright holder can require payment network providers (PayPal, credit card networks) to block payments to such web sites (in either category above) and can require search engines to stop providing advertising for such web sites—simply by sending them a letter. That's SOPA § 103(b).*

Another controversial provision is the one in § 102 that allows the Justice Department to order domain name servers to stop translating URLs (like "www.google.com") into the IP addresses that actually point your browser to the web sites you want to go to—essentially without due process. This has been described by some as tantamount to "breaking the Internet" because it would break the integrity of the domain name system that keeps the Internet organized. (For overviews of the bills, see Brad Plumer and the EFF; for the case that it violates the First Amendment, see Mike Masnick, who quotes extensively from and links to Lawrence Tribe's argument).

Naturally, I was wondering how the bill would affect me. Many people think it would impose a requirement that web sites police not only the content they produce themselves, but the content contributed by visitors (e.g., blog comments), and all the content on all the sites they link to (including links in blog comments). I think this is based on § 103(a)(1)(B)(ii)(I) (don't you love bill numbering?), which puts your site in the wrong if it "is taking, or has taken, deliberate actions to avoid confirming a high probability of the use of the U.S.-directed site to carry out acts that constitute a violation of section 501 or 1201 of title 17, United States Code." What does it mean to take actions to avoid confirming a high probability that someone is using your site to link to copyrighted material?

Now, § 103 only allows copyright holders to cut you off from payment networks and advertising, and since we don't do either one here, I don't think it would mean the end of The Baseline Scenario. But it could mean the end of every commercial blog, or at least the end of comments on any commercial blog that doesn't have the staff to police comments and sites linked to in comments. And if it passes, I will at least turn off comments until I can get an opinion from a real IP lawyer whom I trust.

So if you like the Internet the way it is, tell your representatives that you oppose SOPA and PIPA, via the EFF, Google, or Wikipedia. Thanks.

(I know it's been a slow start to the year on the blog. I had a wedding to go to out of the country and an intensive week of edits on an upcoming book. Things should return to normal slowly.)

* Section 103, in bipartisan Orwellian fashion, is entitled "MARKET-BASED SYSTEM TO PROTECT U.S. CUSTOMERS AND PREVENT U.S. FUNDING OF SITES DEDICATED TO THEFT OF U.S. PROPERTY." What's market-based about a system that allows one party to cut off the revenues of another party simply by sending a letter to PayPal, MasterCard, Visa, and American Express?

January 12, 2012

Refusing To Take Yes For An Answer On Bank Reform

By Simon Johnson

The debate over megabanks and – in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis – how to deal with all the problems associated with "too big to fail" in the financial sector has not been easy for many politicians. The problems and potential real solutions do not map readily into the standard left vs. right divide in American politics.

The left generally wants the state to do more, and these days most of the right usually wants the state to do much less. But in this space regulators are "captured", meaning that too many of them are effectively working to promote the interests of the big banks rather than to limit the dangers to the rest of us – so "more regulation" does not make much sense. And these big banks have a strong incentive to get even bigger – it's their size that gives them economic and political power. If you leave these banks to their own devices, they will become even bigger and blow themselves up at greater cost to ordinary citizens (see Western Europe for details). So "no regulation" is also not an appealing proposition.

As a matter of presidential year politics, there is a remarkable convergence between President Obama and Mitt Romney, the Republican frontrunner. Both think that we can tweak the rules to keep the banks from becoming dangerous. The Obama administration calls their approach "smart regulation", while Mr. Romney has spoken of repealing the Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation (although his website is devoid of any further specifics). But as far as anyone can see, their proposed approaches for the next four years are very similar – relying on the state to play a particular oversight role that has not gone well in recent decades. They are both "statist" in this very particular sense.

The way to cut our Gordian financial knot is simple – force the big banks to become smaller. Small banks and other financial institutions can be allowed to fail unencumbered by any kind of government bailout. MF Global failed recently with about $40 billion in total assets; the shock waves did not bring on global panic. A properly functioning market economy involves failure of this kind (although it is traumatic for employees and, in this specific case, also for many customers.)

A version of this idea was put forward by Democratic Senators Sherrod Brown and Ted Kaufman during the Dodd-Frank financial reform debate last year. Their SAFE banking amendment would have put a hard size cap on the largest banks, relative to the size of the economy. This amendment was defeated, 33-61, on the floor of the Senate.

From the right, Jon Huntsman has proposed essentially the equivalent idea. He proposes a menu of options – presumably to give himself some room to negotiate with Congress – but his first idea is: "Set a hard cap on bank size based on assets as a percentage of GDP", where the specific cap seems very much in alignment with Brown-Kaufman. He also proposes a hard cap on leverage and, as a complement to this, a punitive fee on bank size: "The fee would incentivize the major banks to slim themselves down; failure to do so would result in increasing the fee until the banks are systemically safe. Any fees collected would be used to reduce taxes for the broader non-financial corporate sector."

Not only is Huntsman advancing concrete proposals, he is also making it abundantly clear that these policies are the proper way to apply pro-market thinking. His proposals also do not represent any kind of "move to center" (in the standard terminology of commentators).

The left does not like big banks because they represent an abuse of power by private individuals. The clear-thinking right detests such banks even more – because they are supported by large, nontransparent, and very dangerous government subsidies. There is nothing about the market in too big to fail banks – this is state capture, pure and simple.

Both sides should be able to agree that they have converged on this point. The left (and the center) should be supporting Jon Huntsman for the Republican presidential nomination – at least as a way to push the banking reform agenda in a meaningful direction.

Some commentators on the right get this. But important voices on the left hold back – perhaps refusing to believe that they can agree with an idea that also has support on the right. Granted, it doesn't happen often – but this is one such opportunity to really make progress against a powerful and dangerous special interest.

On reducing the size of our largest banks, Senators Brown and Kaufman asked the question: Can we do this, reaching across the political aisle? Their amendment was supported by a couple of Republican votes, including Richard Shelby, ranking minority member of the Senate Banking Committee. Most of their supporters were Democrats.

But now Jon Huntsman offers a different answer and a definitive "Yes" on reducing the size of our largest banks. If Huntsman becomes the Republican nominee – or even if he gets real traction in the upcoming primaries – the idea of reining in the size and power of megabanks could actually take hold within the Republican party.

Why won't people on the left see this opportunity and support it fully?

An edited version of this post appeared this morning on the NYT.com's Economix blog; it is used here with permission. If you would like to reproduce the entire post, please contact the New York Times.

January 5, 2012

Ron Paul And The Banks

By Simon Johnson

We should take Ron Paul seriously. The Texas Congressman had an impressive showing in the Iowa caucuses on Tuesday and his poll numbers elsewhere are resilient – he is running a strong third nationally, but looks like to come in second in New Hampshire. He may well become the Republican politician with populist momentum and energy in the weeks ahead.

Mr. Paul also has a clearly articulated view on the American banking system, laid out forcefully in his 2009 book, End the Fed. This book and its bottom line recommendation that we should return to the gold standard – and abolish the Federal Reserve system – tends to be dismissed out of hand by many. That's a mistake, because Mr. Paul makes many sensible and well-informed points.

But there is a curious disconnect between his diagnosis and his proposed cure. This disconnect tells us a great deal about why this version of populism from the right is unlikely to make much progress in its current form.

There is much that is thoughtful in Mr. Paul's book, including statements like this (p. 18):

"Just so that we are clear: the modern system of money and banking is not a free-market system. It is a system that is half socialized – propped up by the government – and one that could never be sustained as it is in a clean market environment."

Mr. Paul is also broadly correct that the Federal Reserve has become, in part, a key mechanism through which large banks are rescued from their own folly – so that their management gets the upside when things go well and the realization of any downside risks gets shoved onto other people.

If you don't like this characterization of the American system, turn your attention to Europe and the eurozone – where the European Central Bank is busy propping up banks with "liquidity" (in the form of three year loans), in part hoping these financial institutions can in turn support the government bond market.

There are no Ron Paul-type populists in Europe – at least I have never come across a mainstream politician there wanting to abolish any central bank. But I would predict that related views will pick up European adherents in the months ahead, for example as people in Germany increasingly worry about the actions of the European Central Bank – and want to go back to some version of their own Bundesbank, which was very careful about not creating inflation.

Mr. Paul represents an important strand of American libertarian thinking, seeing the root of all financial evil in the role of the government – and tracing this back to what he sees as deviations from the U.S. Constitution, made possible by the Supreme Court (beginning with McCulloch v. Maryland in 1819; I recommend Aggressive Nationalism: McCulloch v. Maryland and the Foundation of Federal Authority in the Young Republic, by Richard E. Ellis, if you'd like to read more on that key episode).

Mr. Paul's argument goes too far in this direction, however, including with statements like "The Supreme Court has never been a friend of sound money and has rarely been a protector of the Constitution," (p.168). His book would also be more convincing if it relied a little less exclusively on sources produced by a single publisher, the Ludwig von Mises Institute.

The gold standard to Mr. Paul is a panacea, because it would restrict the role of the government and what a central bank could do. In fact, in his version of the gold standard – which is not the one that generally prevailed – there is no role for a central bank whatsoever.

But Mr. Paul's own book also acknowledges the imbalance of power within the financial system that prevailed at the end of the nineteenth century – Wall Street financiers, such as the original J. P. Morgan, were among the most powerful Americans of their day. In the crisis of 1907, it was Morgan who essentially decided which financial institution would be saved and who must go the wolves.

Would abolishing the Fed really create a paradise for entrepreneurial banking start-ups – enabling them to challenge and overthrow the megabanks?

Or would it just concentrate even more power in the hands of the largest financial players? It is hard to find a moment of greater inequality of power than that of the gilded age of the late 1800s – with the gold standard and the associated credit system firmly working to the advantage of J. P. Morgan and his colleagues.

Mr. Paul insists that "In a competitive and free system, deposits would not be unsafe; any that were not paid back that were promised would fall under the laws of protection against fraud," (p. 27).

Again, this seems to mistake the true nature of power in both modern American society – and in a world without any limit on the scale and nature of banks. Laws and rules do not drop from the sky; they are shaped in minute detail by an intense and very expensive lobbying process. (For a prominent and credible example, Jeff Connaughton's latest piece on how slow the SEC has been to deal with concerns about high frequency trading.)

There is nothing on Mr. Paul's campaign website about breaking the size and power of the big banks that now predominate (http://www.ronpaul2012.com/the-issues/end-the-fed/). End the Fed is also frustratingly evasive on this issue.

Mr. Paul should address this issue head-on, for example by confronting the very specific and credible proposals made by Jon Huntsman – who would force the biggest banks to break themselves up. The only way to restore the market is to compel the most powerful players to become smaller.

Ending the Fed – even if that were possible or desirable – would not end the problem of Too Big To Fail banks. There are still many ways in which they could be saved.

The only way to credibly threaten not to bail them out is to insist that even the largest bank is not big enough to bring down the financial system.

An edited version of this post appeared this morning on the NYT.com's Economix blog; it is used here with permission. If you would like to reproduce the entire column, please contact the New York Times.

December 31, 2011

Correction to Long-Term Debt Projections

By James Kwak

Back in October, I wrote a post laying out my long-term projections for the national debt, which were basically an adjustment to existing CBO projections. Peter Berezin recently pointed out a misleading ambiguity in that post. There, I used the same long-term growth rate of tax revenues in both my extended-baseline scenario and in my "realistic" scenarios. I got that long-term growth rate from the CBO's extended baseline scenario in its 2011 Long-Term Budget Outlook, which assumes that current law remains unchanged.

In my realistic scenarios, I assumed that the AMT would be adjusted through 2021 but that the long-term growth rate would apply thereafter. I didn't say anything explicitly about the AMT after 2021, but by using the long-term growth rate from the extended baseline, I was implicitly assuming that the AMT would not be indexed after 2021.

This is certainly a possible policy choice, but I think it is optimistic (from a budgetary perspective), and a more conservative assumption is that the AMT will be indexed forever. This means that you would have to use the long-term growth rate from a world in which the AMT is indexed. Such a world is portrayed in the CBO's 2009 Long-Term Budget Outlook, alternative fiscal scenario, Figure 5-1. (The 2011 alternative fiscal scenario assumes instead that taxes will remain constant as a share of GDP.) By my calculation (from the Additional Info spreadsheet), the long-term growth rate of tax revenues is 0.3 percent per year (over the 2021–2080 period). So I've adjusted my spreadsheet to use this growth rate instead.

This yields the projections shown in the figure above. As before, the red lines are the CBO projections from June, the green lines are my adjustments to those projections based on more recent information, and the blue lines are the scenarios that I think are more realistic—one assuming expiration of the Bush tax cuts, one assuming extension.

The most important point remains the same: If we let the Bush tax cuts expire, the national debt will be significant and rising in the long term, but will not be that much larger than today even in 2035. Which means that the national debt problem over the next twenty-five years is as much about tax cuts as about entitlement spending.

(This update also reflects a couple of small technical corrections, which barely changed the numbers.)

December 27, 2011

State of Nature

By James Kwak

I've been reading a lot of books lately, some of which I've mentioned here: The Submerged State by Suzanne Mettler, Invisible Hands by Kim Phillips-Fein, The Wealth and Poverty of Nations (finally) by David Landes, Exorbitant Privilege by Barry Eichengreen, and a pile of books on the national debt and deficit politics. (Despite moonlighting as a blogger, I find books more satisfying than the constant stream of newspapers, magazines, and blogs.) But my favorite book I've read in a while is Railroaded: The Transcontinentals and the Making of Modern America, by the historian Richard White.*

For some people, most notably Rick Perry but also much of the conservative base, the late nineteenth century was the golden age: of the gold standard, no income tax, senators elected by state legislatures, and, most importantly, little to no government "regulation" of business. White shows what that world was really like.

The book focuses on the "transcontinentals"—railroads that began West of the Mississippi and ran to the Pacific. These railroads have often ben heralded as great achievements of entrepreneurial capitalism and the first modern corporations. Not so much, White argues.

First of all, the transcontinental railroads were a poor use of capital. There simply wasn't enough transcontinental traffic to warrant any transcontinental railroads, let alone so many. Even in the late nineteenth century, it was cheaper to send goods by steamship (with an overland journey in Panama). The railroads only survive because the Pacific Mail was a "lazy and corrupt" company. The railroads bribed the steamship company by overpaying for capacity, and in return the Pacific Mail kept prices high enough so the railroads could "compete."

So how did unnecessary, inefficient railroads get built? Because of government subsidies. In short, the federal government paid to build the railroads through massive financing subsidies and also gave them ample land grants. The trick to building a railroad was not knowing anything about railroads or even about business; it was having friends in Washington who could give you the right financing and land subsidies.

Even then, the railroads lost money. Not only was there insufficient demand for their services, but they were run by people who were generally incompetent. (For one thing, they didn't even know their own costs of doing business.) Yet the people who owned the railroads made fabulous amounts of money (of which Stanford University is one symbol). The main way to do this was simple. The people who controlled a railroad (generally by putting up very little of their own money, thanks to the government subsidies) would also wholly own a construction company. They would cause the railroad to overpay the construction company to build the railroad—in effect transferring wealth from railroad stockholders and creditors into their own pockets. Another scheme was to buy up land along future railroad routes that only they knew to make an easy profit. Only slightly riskier were schemes to make money by using insider information to trade in securities of their own companies.

The railroads themselves also put the lie to the myth of the efficient, modern corporation. Executives had virtually no control over what went on in the field. Jobs were treated as a form of patronage, with rampant nepotism. Corruption existed on all levels, with station agents routinely pocketing a share of revenues. Competition failed to impose discipline: when one railroad lost traffic to another, it would simply overbuild in another place to compensate, leading to even more overcapacity. The only solution was cartels, but even those failed because the railroad heads were too incompetent to figure out a way to restrain their own behavior.

All along the way, you also see the other consequences of concentrated power, enormous wealth, and political protection. Railroads resisted installing automatic train couplers for decades, resulting in many unnecessary deaths. The railroads interfered in other markets by setting rates in a discriminatory fashion, influencing what crops farmers produced and determining which competitors won and lost. Through it all, you see rich people surrounded by circles of flatterers and yes-men who despise them behind their backs.

This is what the golden age of unregulated capitalism looked like. It's also the world we're heading towards: one where inefficient corporations run by incompetent bunglers make huge piles of money for a chosen few executives and owners by buying politicians (completely legally, thanks to Citizens United), shifting losses onto outsiders and imposing costs on the rest of society. If this sounds like hyperbole, just think about the financial crisis.

* I got a free copy from the publisher (which I read and then gave to Simon for Christmas).

December 23, 2011

Vouchers vs. Premium Support

Uwe Reinhardt has a very clear post on the difference between vouchers and premium support and how it applies to the Ryan-Wyden plan. You might may say that the labels are arbitrary, but there is still a substantive difference between the two in where the risk lies.

Simon Johnson's Blog

- Simon Johnson's profile

- 78 followers