Simon Johnson's Blog, page 43

March 5, 2012

Invisible Handouts and Anti-Government Conservatives

By James Kwak

Ezra Klein wrote a column for Bloomberg discussing research by political scientist Suzanne Mettler and some of her collaborators. Mettler studies what she calls the "submerged state"—the growing tendency of government programs to provide benefits in ways that mask the fact that they come from the government—and its implications for perceptions of government and ultimately for democracy.

There are several important lessons to draw from Mettler's work. The most obvious, which was highlighted by Bruce Bartlett a year ago (and that I wrote about here), is that Americans are hypocrites: many people benefit from government programs, ranging from the mortgage interest deduction to Medicare, yet deny receiving help from any "government social programs."*

Klein focuses on a different point. For him, the main problem with invisible benefit programs is that they are politically difficult to eliminate. He writes, "If Americans who either rent or own their homes outright were asked to accept a tax increase of $150 billion in order to subsidize the mortgage payments of their indebted friends, it seems unlikely they would find that appealing." Now, I hate tax expenditures as much as the next policy wonk, but I'm not entirely convinced by this. First of all, every tax expenditure was passed at some point by some elected legislature. More importantly, the mortgage interest deduction, for example, is actually quite popular. This particular deduction isn't hidden in the sense that no one knows about it; it's hidden in the sense that people think of it as a natural feature of the income tax that they are entitled to, not as a government spending program.

In fact, simply telling people about the mortgage interest deduction doesn't make it any less popular. In an experiment by Mettler and Matt Guardino (which is described in chapter 4 in Mettler's book, The Submerged State, and which I also discussed here), subjects were first asked whether they supported the mortgage interest deduction; later they were given some information about the deduction and again asked if they supported it. Among people who were simply told what the deduction is, opinions shifted from 65-7 in favor to 81-6 in favor; that is, more information made it more popular, not less. Among people who were told what the deduction is and that most of its benefits go to high-income households, opinions shifted from 55-7 in favor to 40-41 against. In other words, it's learning about the distributional effects of the policy that makes it unpopular, not simply learning that it exists or what it is.

But the most important implication of this research, I think, has to do with how these invisible handouts undermine attitudes toward government. As Mettler says (quoted by Klein), "I think one of the drivers of the kind of polarization we have today is policy design and delivery, because we have these policies where people can benefit a lot from the government but become more anti- government because they're paying higher taxes and don't think they're getting benefits."

One of the key themes we discuss in White House Burning is the rise to power of the conservative anti-tax, anti-government movement over the past half century. Government tax and spending policy is largely about distributional issues. When the poor are (indirectly) in power, they take their winnings in the form of benefit programs, since they don't have a lot of taxes to cut. When the rich are in power, they take their winnings in the form of tax breaks. (For the most part: there are also sweetheart no-bid contracts, subsidies for non-commercial airports, and so on.)

What's great about this for the rich is that those tax breaks only strengthen their political position. Tax breaks—say, preferred rates on dividends—mean either higher taxes on everyone else or larger deficits, both of which are unpopular. Since no one can see what the government is doing, it becomes less popular. Higher taxes make people think they're not getting their money's worth; larger deficits make them think the government is incompetent. Either way, they get mad at the parts of government they can see, not the tax breaks that the rich benefit from. Increasing anti-government sentiment leads to what you saw in 2010 and today: the Tea Party, demonization of the federal government, and a mad race among Republicans to see who can cut rich people's taxes by the most.

Whether this is a conscious goal of the anti-tax movement or simply a nice side benefit , it really works. In chapter 2 of The Submerged State, Mettler describes a study showing that people who benefit from visible government programs (those that are transparently delivered by government agencies, such as food stamps) are more likely to have positive views of government and its impact on their lives than people who benefit from invisible programs, even after controlling for the usual things. So you can have a program like the mortgage interest deduction that mainly helps the well-off but also helps the middle class a little—and it helps turn its middle-class beneficiaries against the federal government. If you're Grover Norquist, what could be better than that?

* As I said at the time, I think this is a bit of a trick question, since the researchers first asked people if they benefited from "government social programs" and then asked them if they benefited from a list of government programs like the mortgage interest deduction. I think you can know that the mortgage interest deduction is a government program (how could it not be a government program) yet legitimately not think of it as a "social program."

March 2, 2012

Thanks To "Tax Notes"

By Simon Johnson

In my post this morning on dynamic scoring and how to turn the United States into something closer to Greece, I requested that the publication Tax Notes bring an article by John Buckley out from behind their paywall ("Dynamic Scoring: Will S&P Have Company?," published February 28, 2012.)

The publishers have now done so, for which I would like to thank them – this is a public service that is greatly appreciated. I don't know how long the article will remain in the open access part of their website, so I strongly advise anyone who cares about the fiscal future of this country to read it now (and tell your friends).

"Dynamic scoring" of U.S. budget proposals would be a disaster.

Here's another version of the link, in case you prefer things that are not embedded: http://www.taxanalysts.com/www/features.nsf/Articles/43736B49FCB019E3852579B5006E1933?OpenDocument

Democrats and the Bush Tax Cuts

By James Kwak

Mark Thoma provides an excerpt from Noam Scheiber on Peter Orszag's attempt to let all of the Bush tax cuts expire. In short, Orszag wanted to extend the "middle-class" tax cuts for two years (letting the tax cuts for the rich expire); then he expected the middle-class tax cuts to expire as well. President Obama was interested in the plan, which Scheiber takes as evidence that "the president is a true fiscal conservative."

Thoma frames this as a bad thing:

"The explanation, of course, is that despite hopes to the contrary (and denial by some), the president is, 'a true fiscal conservative' — it's not just an act in an attempt to capture the middle — and that could be bad news not just for middle class tax cuts, but also for important social insurance programs such as Social Security."

I like and respect Mark Thoma a great deal, and I generally think of him as a mainstream Democrat on economic issues, neither a socialist nor a "moderate Democrat" (what we used to call a Republican). To me, his post is evidence that many Democrats think that most of the Bush tax cuts were an are a good thing. This confuses me. When did we become the party of tax cuts?

Let's leave aside the question of whether Barack Obama is a fiscal conservative (and whether that term has any meaning anymore) and focus on the narrower question of whether it would be good to let the "middle class" tax cuts (usually defined as tax cuts for married couples making less than $250,000) expire.

There are three logically separable issues here. The first is whether, leaving aside considerations of the business cycle, we would be better off with the Clinton tax code (mainly set in 1993, tweaked in 1997) or the Bush tax code (set in 2001 and 2003, extended in piecemeal fashion during the Bush administration, and finally extended in 2010 through 2012). On this question I think the answer has to be that the Clinton tax code is preferable, at least for people with generally Democratic preferences.

One way to think about it is this: In 2001 and 2003, did you think the Bush tax cuts were good policy? If you didn't think they were good policy then, why would they be good policy now? If you can't remember what you thought about them then, let me remind you. EGTRRA and JGTRRA were huge tax cuts for the rich and small tax cuts for the middle class and the poor. EGTRRA was passed at a time when large majorities of the country wanted to bolster Social Security and Medicare rather than cut taxes;* JGTRRA was passed after a recession and September 11 had already wiped out the Clinton-era surpluses and less than two months after the invasion of Iraq.

More generally, tax cuts always have to be paid for, one way or another, in lower transfers, fewer services, or higher taxes in the future. Since the poor and middle class are net beneficiaries of transfers and services, the Bush tax cuts were, on balance, bad for the poor and the middle class (unless they would be paid for by tax increases that made the tax code even more progressive than before—an unlikely prospect). For a quantitative analysis, see Elmendorf, Furman, Gale, and Harris (2008). (I'm not going to bother rebutting the supply-side justification for the tax cuts since, for now, I'm talking to Democrats; I know why Republicans liked the tax cuts.)

If the tax cuts were bad a decade ago, what has changed since then (for now, leaving aside cyclical issues)? We have had one more decade of aging and health care inflation (and war), so the long-term budget outlook looks considerably worse. The need to ensure the long-term survival of Social Security and Medicare is greater. Increased income inequality has made provision of basic safety net services even more important. These are all things that demand more tax revenue, not less. The case against the Bush tax cuts has only become stronger.

Assuming you're with me so far, the second issue is whether it would be good to have just the middle-class tax cuts and not the tax cuts for the rich, which is what President Obama has proposed. (Leave aside for now the question of whether this would be politically feasible with today's Republican Party.) This is a closer call, but I still think the right answer is no tax cuts.

To begin with, who among you (again, I'm aiming this at Democratic policy wonks) thought that the thing we needed in 2001 was a middle-class tax cut? Not many, if I recall correctly. Democrats wanted more money for education, infrastructure, job training, and child care. We wanted better health care. We wanted to set aside money for Social Security and Medicare. We didn't want tax cuts. Again, I think the past decade has just strengthened all of these concerns. Yes, the middle class is struggling with stagnant wages and rising economic insecurity. But in aggregate, middle class families need robust social insurance programs to protect them from falling into poverty more than they need a few hundred dollars of after-tax income. And given the current political climate, that is the choice we face.

The third issue is whether, given the actual business cycle, we should raise taxes on the middle class right now. Here I will go along with Thoma and DeLong and Krugman and all the rest and agree that it might not be good to raise taxes on the middle class on January 1, 2013. If I were king, I might extend the middle-class tax cuts for another two years and then let them expire.

But this "if I were king" stuff is meaningless. First of all, if I were actually king, I would still let all the tax cuts expire; then I would use the additional revenues to increase government spending. (Remember, fellow Democratic policy wonks, we usually say that spending has a higher multiplier than tax cuts.) Second, I'm not king, and neither are you. We are dealing with a Republican Party that will block any package that raises taxes on anybody. They will block any tax increase, even if it hurts them in the general elections, because they are completely locked in by the Grover pledge and the Koch brothers. The only choice we have is between extending all of the tax cuts and complete gridlock, which means that they all expire. And if we extend the Bush tax cuts, we are just four Senate seats away from making them all permanent.**

Given that choice, I vote for gridlock. I understand the counterargument: tax increases would weaken the recovery and increase unemployment in the short term. But those tax revenues are crucial to the long-term health of the middle class. Ending the Bush tax cuts will slash projected deficits and push right-wing claims about the bankruptcy of Social Security and Medicare decades into the future. Yes, conservatives will always want to privatize Social Security and dismantle Medicare, but they only have a chance of actually succeeding when government deficits make those programs seem unsustainable, bringing so-called centrists over to their side.

So, for me, letting all the tax cuts expire on December 31 is better than making them permanent. Letting them all expire is also better than making just the "middle-class" tax cuts permanent. (Another note to Democrats: since when do we push for tax cuts for families making $200,000 a year?)

There's one more option you may say you prefer: letting the tax cuts for the rich expire, extending the middle-class tax cuts for another two years, and then letting them expire (assuming we are back to trend growth). As I said above, I don't think this is politically feasible, given who's in charge of the Republican Party. But if that's what you want, that's also what Peter Orszag wanted and Barack Obama seriously considered. So why are they the bad guys?*** (Note that I'm not defending Obama's willingness to negotiate away Social Security and Medicare, which I do not agree with.)

In the end, I think the Bush tax cuts were one of the two most catastrophic policy decisions of this century (the other was the Iraq War). They were a terrible idea then and they are a terrible idea now. I think letting them all expire would be good for the world and for the middle class. And whether or not that makes me a "fiscal conservative," I think it makes me a Democrat.

* See Hacker and Pierson, Off Center, pp. 49–53.

** Does anyone think Obama would veto a bill passed by both houses that locks in lower taxes?

*** You could say that Orszag wanted to implement this policy two years ago, which meant a tax increase in 2013, while you want to implement it now, which means a tax increase in 2015. I see the point, but that's a tactical distinction, not a difference of philosophy.

Beware of "Centrists" Bearing Consensus

By James Kwak

Floyd Norris has written another good column skewering the Republican candidates' tax proposals. It's not hard: all you have to do is list the many ways they want to cut taxes—which make George W. Bush look like a veritable communist, out to confiscate all private wealth—and point out the vast increase in budget deficits that would follow.

Near the end, Norris has this paragraph:

To some deficit hawks, like Maya MacGuineas, the president of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, the campaign so far has been a disappointment. In tax policy circles, she said, there has been growing agreement that a reform similar to the 1986 Reagan tax reform is needed — cutting rates and eliminating loopholes and deductions. But while that reform was revenue-neutral, she said, this one would need to raise revenue.

I wouldn't call myself a member of "tax policy circles," so maybe there is such a consensus. "Cutting rates and eliminating loopholes and deductions" was a feature of Bowles-Simpson, Domenici-Rivlin, and the Gang of Six. But that doesn't make it right.

Eliminating loopholes and deductions obviously makes sense, both because of the distortions they create and because of the growing national debt. This is something I've argued for myself. But why do we need to lower rates? Today's tax rates were set by George W. Bush in 2001 and are considerably lower than the rates that prevailed under Bill Clinton and, for that matter, during most of the history of the income tax. The tax rates on capital gains and dividends, in particular, are at their lowest levels since before World War II. For those of you who care about global competitiveness, total taxes in the United States are lower than in most other advanced industrialized countries. Given the expected growth in the national debt due to demographic shifts and health care inflation, the obvious thing to do would be to simply return to Clinton-era tax rates.

The need to lower rates is not economic, but political. The simple fact is that given the Republican Party of Grover Norquist, you cannot get a single prominent Republican to sign on to a tax plan that does not cut tax rates. Ergo, if you want to call yourself bipartisan, you have to cut rates. But that doesn't mean it's right; that just means that the Republicans have successfully eliminated their negotiating room, forcing would-be centrists to cave in to their demands.

MacGuineas did say that tax reform this time would have to increase revenue. That sounds good—until you realize what "increase" means. Bowles-Simpson, Domenici-Rivlin, and the Gang of Six would all drastically reduce tax revenue from the levels dictated by current law.

Remember, under current law the Bush tax cuts all expire. These "centrist" plans only "increase" tax revenue by first adopting a baseline in which the Bush tax cuts are made permanent. That's how the Gang of Six plan promised to "provide $1 trillion in additional revenue" while at the same time providing "net tax relief of $1.5 trillion." Bowles-Simpson promised $180 billion in additional tax revenues in 2020—but their baseline assumed the continuation of the Bush tax cuts, which would reduce 2020 tax revenues by more than $500 billion. Domenici-Rivlin increased tax revenues by $435 billion over 2012–2020, but also only after making the Bush tax cuts permanent, costing almost $1.4 trillion over that period.* In each case, the "increased" tax revenue is only a small fraction of the tax revenue sacrificed to the Bush tax cuts.

Now, you may think that the appropriate level of taxes is just slightly above the level set by George W. Bush in 2001 and 2003. You may want to make the Bush tax cuts permanent and then trade off fewer loopholes for lower rates. But if that's what you think, just come out and say it. Don't claim to be increasing taxes in the name of fiscal responsibility.

* The cost of the Bush tax cuts here is from the CBO's August 2010 estimate and does not include interest on the additional debt.

Making the United States More Like Greece

By Simon Johnson

One of the big problems in Greece over the past decade or so is that the government was not honest with its data. Various people assisted in the matter – including Goldman Sachs with respect to some debt issues – but ultimately this was a political decision at the highest level. The people running the country decided to conceal the true nature of their budget and their debt. This deception ended up costing the country dearly – completely undermining its credibility under pressure and making it much harder to turn the fiscal and economic situation around.

House Republicans are now proposing something similar for the United States.

Because this concerns deficits and debt, the details may seem arcane – and that is how similar details escaped attention by almost everyone in Greece. Fortunately, in the United States we have an excellent guide – an article in Tax Notes by John Buckley. ("Dynamic Scoring: Will S&P Have Company?," February 28, 2012; at the moment this is available only behind their paywall but in the public interest I would strongly encourage Tax Notes to make this piece freely available – as they have in the past for other important articles.)

The key issue here is a concept known as "dynamic scoring." This may sound like boring jargon but in fact it cuts to the heart of the most important political issue of the day – the effect of tax cuts.

Republicans want to cut taxes – there is no secret about that. All four remaining presidential candidates have fiscal proposals with major tax cutting elements. The problem for them and for their congressional colleagues is that we have an honest broker in the fiscal arena – the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office (CBO) – that "scores" fiscal proposals according to their likely impact. (The CBO scores official proposals; it does not score candidates – but its approach to scoring is influential and largely followed by others, such as the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, CRFB.)

In the modern United States, cutting taxes leads to lower revenue and larger budget deficits. There are no two ways about this – as Ronald Reagan discovered in the early 1980s. (In our new book, White House Burning, we go through the evidence on this point in detail, including important work by Greg Mankiw, former top economic adviser to George W. Bush and now working with Mitt Romney, which confirms that cutting taxes in the U.S. will lower revenue.)

But many Republicans feel that this is not true – in my conversations with them, for example in congressional hearings over the past year, the conviction seems to be that the research on this topic is bad science, even when done by Republicans. But convincing the CBO to abandon its proven and sensible approach to budget scoring has been difficult.

The solution currently under consideration is simple in its elegance – and downright frightening in its implications.

The CBO was created by Congress and receives its instructions directly from the House and Senate Budget Committees. If the Republicans controlled both committees, it would be a simple matter to convey to the CBO director that instead of using established scoring practices, it should switch to "dynamic scoring." (If Doug Elmendorf, the highly respected current CBO director, were to resist, he could be replaced – his four year term of office will be up for renewal next year.)

What's wrong with "dynamic scoring" – a procedure that would attach magical growth implications to tax cutting? Mr. Buckley's article contains all the details, but his basic point is simple.

The macroeconomic models used to claim big growth effects for tax cuts are simply wrong – and completely at odds with the empirical evidence. A smart modeler can assume something different and show you that with a great deal of math, but this is just an assumption dressed up in a complicated fashion.

Put more bluntly – there is no magic in the real world, just very large budget deficits. As Mr. Buckley puts it, "One cannot find in the economic data for the last 30 years any evidence that supply-side-based tax policy has delivered its promised benefits."

If you cut taxes, revenues will fall and deficits will increase. If you change the CBO's scoring process to hide this fact – as is under consideration by leading Republicans on the House Budget Committee and the House Ways and Means Committee – you are engaging in exactly the same sort of deception that brought down Greece.

Alan Greenspan – a leading Republican in his day – got this right in congressional testimony back in 1995 (quoted by Mr. Buckley),

"Should financial markets lose confidence in the integrity of our budget scoring procedures, the rise in inflation premiums and interest rates could more than offset any statistical difference between so-called static and more dynamic scoring."

March 1, 2012

When Did Republicans Become Fiscally Irresponsible?

By Simon Johnson, co-author of White House Burning: The Founding Fathers, The National Debt, and Why It Matters To You, available April 3rd

The United States has a great deal of public debt outstanding – and a future trajectory that is sobering (see this recent presentation by Doug Elmendorf, director of the Congressional Budget Office). Yet the four remaining contenders for the Republican nomination are competing for primary votes, in part, with proposals that would – under realistic assumptions – worsen the budget deficit and further increase the dangers associated with excessive federal government debt.

Politicians of all stripes and in almost all countries claim to be "fiscally responsible." You always need to strip away the rhetoric and look at exactly what they are proposing.

The nonpartisan Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget does this for the Republican presidential contenders. I recommend making the comparison using what the committee calls its "high debt" scenario. This is the toughest and most realistic of their projections – again, a good and fair rule of thumb to use for assessing politicians everywhere.

Under this scenario, Newt Gingrich's proposals would increase net federal government debt held by the private sector to close to 130 percent of gross domestic product by 2021, from around 75 percent of G.D.P. this year.

This would put us close to Greek levels (before that country's recently proposed debt restructuring). Comparing debt levels across countries needs to be done carefully; I use the most recent available comparative numbers from the International Monetary Fund (see Statistical Tables 7 and 8). Or you can read the full report.

In contrast, Mitt Romney's and Ron Paul's fiscal plans would elevate our debt levels merely to Italian levels (around 95-100 percent of G.D.P.), while Rick Santorum would prefer to end up more like Japan (above Italy but below Greece).

The Republican Party has not always been this way. In fact, for most of its existence the party truly did stand for fiscal responsibility, with its leadership routinely placing a high priority on balancing the budget.

In fact, for nearly two centuries there was a consensus across the political spectrum in the United States, that campaigning on a platform of deliberately boosting the national debt was definitely not the thing to do, at least if you wanted to win an election at any level of government.

For example, toward the end of his second administration, President Dwight Eisenhower was pressed from some quarters to cut taxes in order to boost the election chances of Richard Nixon, his vice president. Eisenhower demurred, preferring to pass on a more nearly balanced budget to whomever his successor would prove to be.

Nixon himself was perhaps the last of the truly fiscally conservative Republicans. It was not that Republicans of that era liked taxes – who does, after all? But the idea that you could sell the electorate on the notion that a responsible politician could assert that plans to cut taxes would "pay for themselves" – and therefore not reduce revenue or increase the budget deficit – had not gained traction.

And the slogan that "deficits don't matter" also seemed too much of a stretch, even in the troubled 1970s. The budget and its deficit did not get out of control under Nixon or Gerald Ford.

It wasn't one single Republican who changed the tone of the conventional wisdom on the right. There were several, including Jack Kemp and Ronald Reagan. But one name stands out as a thread that runs throughout the tax revolt that has taken place within the Republican Party – Newt Gingrich.

From his initial election to Congress in 1978, Mr. Gingrich saw how to win votes by cutting taxes and dealing with the consequences later, or not at all. He was a strong voice against the tax increases put forward in the later Reagan years, after the initial tax cuts, and under George H.W. Bush. Mr. Gingrich left Congress in 1999, but the anti-tax movement he helped lead prepared the way for a big surge in budget deficits and national debt under George W. Bush.

To understand more about how deficits got out of control with tax cuts and spending increases during the early 2000s, read more by my Economix colleague, Bruce Bartlett, who called this as it was happening. You might start with this retrospective piece.

Claiming to be a fiscal conservative while proposing policies that will greatly increase the deficit is perhaps the most consistent hallmark of Mr. Gingrich's politics over more than 30 years.

In some sense, Mr. Gingrich has already captured the Republican Party: the Republican candidates are competing to see who can make the most fiscally irresponsible proposals and get away with it.

Whoever becomes the Republican presidential nominee will be standing on the shoulders of Mr. Gingrich.

An edited version of this post appeared this morning on the NYT.com's Economix blog; it is used here with permission. If you would like to reproduce the entire column, please contact the New York Times.

February 29, 2012

Why Is Finance So Big?

By James Kwak

This is a chart from "The Quiet Coup," an article that we wrote for The Atlantic three years ago next month. Many people have noted that the financial sector has been getting bigger over the past thirty years, whether you look at its share of GDP or of profits.

The common defense of the financial sector is that this is a good thing: if finance is becoming a larger part of the economy, that's because the rest of the economy is demanding financial services, and hence growth in finance helps overall economic growth. But is that true?

Thomas Philippon is trying to figure this out. In an earlier paper, he looked at demand for financial services from the corporate sector and concluded that growth in the financial sector from 2001 could not be attributed to increasing demand. In a recent working paper, "Has the U.S. Finance Industry Become Less Efficient?"* he now measures the finance share of GDP against the total production of financial intermediation services by the sector. For the latter, he uses time series of corporate debt, corporate equity, household borrowing, deposits, and government debt. The conclusion is that the per-unit cost of financial intermediation has been going up for the past few decades: that is, the financial sector is becoming less efficient rather than more, and that accounts for two percentage points of finance's share of the economy.

Theoretically, finance could be providing other benefits that aren't captured in the output series, such as improved pricing or better risk management. Philippon does provide some evidence to be skeptical of those claims.

The main reason why finance's share of GDP has outstripped its production of intermediation services, according to Philippon, is a huge increase in trading volumes in recent years. Trading, of course, generates fees for financial institutions, with limited marginal social benefits. Yes, we need some trading to have price discovery. But if I sell you a share of Apple on top of the other 33 million shares that were traded today, is that really helping determine what the price of Apple should be? The more that financial institutions can convince us to trade securities, the larger their share of the economy, whether or not that activity improves financial intermediation.

There are still a lot of open issues, but Philippon's approach—measuring what the industry actually does—seems to be a useful one.

* The paper first debuted in the blogosphere back in December. Sorry, I'm behind.

Ron Paul's Budget Proposals: Fiscally Irresponsible

By Simon Johnson, co-author of White House Burning: The Founding Fathers, Our National Debt, and Why It Matters To You, available from April 3rd.

Representative Ron Paul sees himself as an independent thinker – not afraid to confront the conventional wisdom, whether in the form of Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke or mainstream views within the Republican Party. As I have written elsewhere recently, we should take Mr. Paul seriously – and not simply dismiss his proposals out of hand.

However, Mr. Paul's current proposals for the federal budget can only be described as fiscally irresponsible. This is completely at odds with his more general stated principles (including in the hearing with Mr. Bernanke this morning), including his well-articulated concern about inflation.

According to the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (CRFB), Ron Paul's proposals would – even under the most optimistic scenario – leave federal debt roughly where it is now, i.e., at an elevated and dangerous level relative to the size of our economy (see pp. 19-24 of the CRFB report). More realistically, however, we should use the CRFB's high-debt scenario to evaluate all politicians – reflecting the fact that not everything in the world economy will prove smooth sailing over the next decade.

Under this scenario, Mr. Paul's proposals would increase debt to over 90 percent of GDP – roughly the same level currently seen in Italy and other troubled European countries.

I understand that other Republican presidential candidates are even more irresponsible than Mr. Paul (including, most spectacularly, Newt Gingrich). I will have more to say about this tomorrow.

But why does Mr. Paul – an iconoclast of the right and a person who sees himself as a "fiscal conservative" – feels comfortable putting forward proposals that would likely boost our national debt by so much?

February 28, 2012

Some Things Never Change

By James Kwak

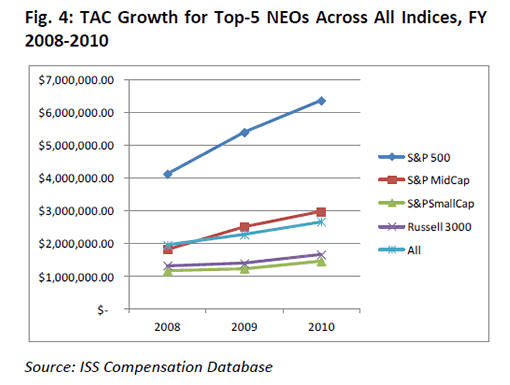

That picture is average total annual compensation for top-five named executive officers at U.S. public companies from 2008 to 2010. (It's from a blog post by Carol Bowie of MSCI, which used to be called Morgan Stanley Capital International.) Over those two years, total annual compensation increased by 37% for all companies and by 54% for companies in the S&P 500. Basically, while bonuses and severance packages have fallen or grown slowly, that effect has been swamped by much bigger stock and option packages. Which is evidence that if you try to rein in some of the more egregious aspects of executive compensation, the executives, their friends on the compensation committee, and their hired guns at the compensation consulting firms will figure out ways to keep the party going.

It's possible that 2008 was a low year for executive compensation because of the financial crisis and recession, so this is just rapid growth from a low base. But check this out:

A December 2011 survey by pay consultant Towers Watson of 265 mid-size and large organizations found 61 percent expect their annual bonus pools for 2011 "to be as large or larger than those for 2010," while 58 percent of respondents expect to fund their annual incentive plans "at or above target levels based on their companies' year-to-date performance." Moreover, 48 percent of those surveyed expect long-term incentive plans that are tied to explicit performance conditions "to be funded at or above target levels based on year-to-date performance."

Critically, 61 percent of respondent in the Towers survey said they believe their total shareholder return will decline or remain flat.

Huh?

February 27, 2012

How Much Do Taxes Matter?

By James Kwak

Christina and David Romer's new paper, "The Incentive Effects of Marginal Tax Rates: Evidence from the Interwar Era," is available as an NBER working paper (if you are so lucky). Given the current debates about taxes, the paper is likely to garner some attention.

In the central section of the paper, Romer and Romer regress reported taxable income against the policy-induced change in marginal after-tax income share. The after-tax income share is the percentage of your gross income that is left after taxes; policy-induced changes are those caused by tax changes rather than be macroeconomic changes. They do this for the top 0.05% of the income distribution, broken down into ten sub-groups by income, because the income tax only affected the very rich during the interwar years.

Their headline finding is that "The estimated impact of a rise in the after-tax share is consistently positive, small, and precisely estimated" pp. 15–16). They find an elasticity of taxable income with respect to changes in the after-tax income share of 0.19.

Advocates of lower tax rates are sure to seize on this as evidence that higher tax rates depress incentives to work. But that's hardly what the paper says. First of all, the Romers' elasticity estimate is lower than earlier empirical estimates that are largely based on the postwar period. To put this in perspective, an elasticity of 0.19 implies that tax revenues would be maximized with a tax rate of 84 percent; that is, you could raise taxes up to 84 percent before people's reduced incentives to make money would compensate for the higher tax rates.

Second, remember that this is a study of the super-rich: not the top 1%, but the top 0.05%. These are the people whom one would expect to have the highest income elasticity, precisely because they don't need the marginal dollar. Elasticities tend to be lower for ordinary people because they need to cover their expenses.

Finally, the left-hand-side variable for the main regression is reported taxable income. Taxable income can change both because people are earning less income and because they are engaging in tax strategies to reduce their taxable income. As Emmanuel Saez, Joel Slemrod, and Seth H. Giertz conclude in "The Elasticity of Taxable Income with Respect to Marginal Tax Rates: A Critical Review" (pp. 49–50):

while there is compelling U.S. evidence of strong behavioral responses to taxation at the upper end of the distribution around the main tax reform episodes since 1980, in all cases those responses fall in the first two tiers of the Slemrod (1990, 1995) hierarchy—timing and avoidance. In contrast, there is no compelling evidence to date of real economic responses to tax rates (the bottom tier in Slemrod's hierarchy) at the top of the income distribution.

In other words, recent U.S. history shows that when you raise taxes on the rich, they don't stop trying to make money: they just pay their lawyers and accountants more to avoid paying taxes. The solution to that is a simpler tax code with fewer exclusions and deductions.

Simon Johnson's Blog

- Simon Johnson's profile

- 78 followers