Simon Johnson's Blog, page 42

March 20, 2012

CFA Institute Against the "JOBS" bill

By Simon Johnson

The Senate is due to vote today on the so-called "JOBS" bill – a piece of legislation, originating in the House, which aims to reduce disclosure and other securities law protections for investors (see my review yesterday; a link to HR3606 is here).

Supporters of the law claim that it will greatly increase the number of companies going public – and that this will boost economic growth and job creation. Opponents argue that by weakening investor protection, the risks of investing in start-up companies will increase – there will be more frauds and scams – and this will increase the cost of capital for honest entrepreneurs.

Members of the CFA Institute have an interest in getting this right – this is the "global association of investment professionals" and they make their living by figuring out what is a good investment and what is likely to become a losing proposition. These people also have a lot of expertise on the key issue – which is better for business, weakening investor protections or keeping them in place? Which way are these experts voting?

Overwhelmingly, members of the CFA Institute are against the "JOBs" bill as it currently stands.

According to a survey released yesterday, and available through MarketWatch, 33 percent of CFA members in the U.S. think that the Senate should "not pass this bill," while 27 percent think the Senate should pass a bill with more investor protections. (The member survey was conducted online from March 13-16, with 491 U.S. members participating.)

In terms of the effects that the legislation would have on investor protection, the view is overwhelmingly skeptical: 63 percent say "the proposed bill would create additional gaps in investor protection and transparency," and only 3 percent say the bill would improve investor protection (the rest think it will have no effect).

The essential nuts and bolts question is: What effect, if any, would the bill have on an investor's ability to make informed investment decisions? The majority, 59 percent, of those surveyed think, "The bill would decrease an investor's ability to make informed investment decisions," while only 9 percent think it will enable investors to make more informed decisions.

In rather more colorful language, the Motley Fool – a strong advocate for investors – takes an equally negative view of the "JOBS" bill. Investors in companies with less than $1 billion in revenue (i.e., most companies in the United States today) "would look forward to":

"The legalization of Wall Street pump-and-dump behavior that was banned after the Enron and WorldCom frauds.

Less clarity in executive compensation and golden parachute disclosure.

Weaker auditing standards."

Markets with weak investor protection and little effective disclosure are subject to a great deal of volatility. They also do not typically do well over time – there might be a boom for a while, but fraud and excess generally prevail, resulting in a big collapse. Well-connected people, including many stock brokers, can do well – this was the experience in the US stock market frenzy of the 1920s. But ordinary investors do not thrive in this environment – and ultimately everyone suffers, as in the 1930s.

In terms of the practical alternatives at this point, I agree with the position taken by Ilan Moscovitz in the Motley Fool article:

"Although the House has already passed the worst elements of the bill, the Senate is considering the Reed-Landrieu-Levin amendment, which would help clean up most of these problems.

Among other things, the Reed-Landrieu-Levin amendment would make sure investors still get clear executive pay disclosures, reduce the number of companies that get exempted from accounting rules, and help ensure that crowd-funding companies give true information to investors.

They're voting on it tomorrow [i.e., Tuesday/today].

What do you think? You can let your senators know here."

How Long Can We Finance the Debt?

By James Kwak

Everyone should know by now that the Treasury Department can borrow money at historically low rates. That is a major reason why some very smart economists think that the federal government should borrow more money in the short term (i.e., this year and next) and use that money to boost economic growth.

In the medium term (say, the next decade), however, the big question is how long we will be able to finance new government borrowing at such low rates. Today's low rates are a product of several factors. One is certainly the slow rate of economic growth, in particular the depressed housing market, which has reduced demand for credit. But another factor is the Federal Reserve's aggressive moves to keep long-term interest rates down; another is foreign central banks' appetite for Treasuries.

John Kitchen and Menzie Chinn have written a new paper (pre-publication version here) that attempts to disentangle these factors, which Kitchen summarized in a blog post. They show the large and growing role in the Treasury market played by the foreign official sector:

Kitchen and Chinn also measure the impact of purchases by foreign central banks on interest rates. They estimate that as those central banks increase their holdings of Treasuries by 1 percentage point of potential GDP, long-term interest rates (measured as the spread between 10-year and 3-month rates) fall by 0.33 percentage points. Since the Federal Reserve is expected to reduce its balance sheet as the economy recovers, if foreign holdings of U.S. government debt simply remain at current levels (as a share of GDP), they expect that 10-year yields would climb to 7.9 percent by 2020—rather than 5.4 percent as forecast in the CBO's baseline.

The underlying issue is that interest rates have been kept low in part by increasing foreign holdings of Treasuries; so to maintain those low rates, we need foreign central banks to continue buying more and more Treasuries, which cannot go on forever. The policy problem is that we don't want to overreact and shift to austerity prematurely (that is, while we can still borrow money cheaply), but we don't know how long foreign governments will continue increasing their Treasury portfolios.

The current privileged status of U.S. dollar debt is a recent phenomenon, which we describe in chapter 2 of White House Burning, and one that is by no means permanent. This is a major reason why we think that it is important to begin reducing structural deficits during the next decade. And that means we need to have an alternative to the scorched-earth policies of austerity (and tax cuts!) being pushed by Republicans and by a growing number of self-proclaimed centrists.

March 19, 2012

A Colossal Mistake of Historic Proportions: The "JOBS" bill

By Simon Johnson, co-author of White House Burning: The Founding Fathers, Our National Debt, And Why It Matters To You

From the 1970s until recently, Congress allowed and encouraged a great deal of financial market deregulation – allowing big banks to become larger, to expand their scope, and to take on more risks. This legislative agenda was largely bipartisan, up to and including the effective repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act at the end of the 1990s. After due legislative consideration, the way was cleared for megabanks to combine commercial and investment banking on a complex global scale. The scene was set for the 2008 financial crisis – and the awful recession from which we are only now beginning to emerge.

With the so-called JOBS bill, on which the Senate is due to vote Tuesday, Congress is about to make the same kind of mistake again – this time abandoning much of the 1930s-era securities legislation that both served investors well and helped make the US one of the best places in the world to raise capital. We find ourselves again on a bipartisan route to disaster.

The Senate needs to slow down and do its job – we have two legislative bodies for a reason and the Senate's historical role is partly to serve as a check on enthusiasms that may suddenly sweep the House. To pass this legislation on Tuesday would be a grave mistake.

The idea behind the JOBS bill is that our existing securities laws – requiring a great deal of disclosure – are significantly holding back the economy.

The bill, HR3606, received bipartisan support in the House (only 23 Democrats voted against). The bill's title is JumpStart Our Business Startup Act, a clever slogan – but also a complete misrepresentation.

The premise is that the economy and startups are being held back by regulation, a favorite theme of House Republicans for the past 3 ½ years – ignoring completely the banking crisis that caused the recession. Which regulations are supposedly to blame?

The bill's proponents point out that Initial Public Offerings (IPOs) of stock are way down. That is true – but that is also exactly what you should expect when the economy teeters on the brink of an economic depression and then struggles to recover because households' still have a great deal of debt. And the longer term trends over the past decade are global – and much more about the declining profitability of small business, rather than the specifics of regulation in the US (see this testimony by Jay Ritter).

Professor Ritter, a leading expert on IPOs, put it this way:

"I do not think that the bills being considered will result in a flood of companies going public. I do not think that these bills will result in noticeably higher economic growth and job creation."

In fact, he also argued that the measures under consideration "might be to reduce capital formation."

Professor John Coates hit the nail on the head:

"While the various proposals being considered have been characterized as promoting jobs and economic growth by reducing regulatory burdens and costs, it is better to understand them as changing, in similar ways, the balance that existing securities laws and regulations have struck between the transaction costs of raising capital, on the one hand, and the combined costs of fraud risk and asymmetric and unverifiable information, on the other hand." (See p.3 of this December 2011 testimony.)

In other words, you will be ripped off more. Knowing this, any smart investor will want to be better compensated for investing in a particular firm – this raises, not lowers, the cost of capital. The effect on job creation is likely to be negative, not positive.

Sensible securities laws protect everyone – including entrepreneurs who can raise capital more cheaply. The only people who lose out are those who prefer to run scams of various kinds.

Investor protection is good for growth and essential for sustaining capital markets. Experiments involving doing without such protections – as in the Czech Republic in the early 1990s, for example, have not gone well. There might be a temporary frenzy, but the subsequent fall to earth will be painful – and again hard to recover from.

Perhaps the worst parts of the bill are those provisions that would allow "crowd-financing" exempt from the usual Securities and Exchange Commission disclosure requirements. A new venture could raise up to $1-2 million through internet solicitations, as long as no investor puts in more than $10,000 (section 301 of HR3606). The level of disclosure would be minimal and there would be no real penalties for outright lying. There would also be no effective oversight of such stock promotion – returning us precisely to the situation that prevailed in the 1920s.

This might well pump up the value of particular stocks – that was the experience of the 1920s, after all. But ephemeral stock market bubbles are not without real consequences. The crash of 1929 was made possible by the lack of constraints on what stock promoters could say and do. Combined with excessive leverage, this led directly to the Great Depression.

We still have excessive leverage in our financial system today, despite the claims of the Federal Reserve. Allowing the unrestricted promotion of stocks in this fashion is a major step – again – down the path to economic self-destruction.

The legislation would also undo many parts of the 2002 Sarbanes-Oxley law, which was created in the wake of accounting scandals at the likes of Enron and WorldCom. The proposed new rules have been crafted hastily and pushed through in a great rush – presumably because the election season is upon us.

Where are the supposed guardians of our financial system?

The White House is reportedly taken with the idea of crowd-financing and wants a quick political win in the form of legislation; the Obama administration is poised to concede too much to financial sector interests, again. The Treasury Department likes to claim it provides "adult supervision" for all matters financial, yet it is conspicuously absent from serious conversation around this legislation. And he much-vaunted Financial Stability Oversight Council turns out, again, to be a meaningless paper tiger.

The securities industry special interests are naturally out in force – strongly supported by Senator Charles Schumer of New York and Majority Leader Harry Reid. Reports of the death of Wall Street lobbying power have been greatly exaggerated.

Financial deregulation was the result of decades-long delusion and bipartisan consensus. A major undermining of our securities law seems likely to take place on Tuesday – in a rushed moment of legislative madness.

March 15, 2012

The Fetishization of Balance

By James Kwak

I generally don't bother reading Thomas Friedman. A good friend gave me a copy of The World Is Flat, and I started reading it. Somewhere in the first one hundred pages Friedman has an extended discussion of workflow software (as a key enabler of globalization) and I realized that he knew absolutely nothing about workflow software, so I stopped reading it and gave it away.

Another friend pointed out Friedman's op-ed in the Times earlier this week in which he argues for "grand bargains" and "balanced" solutions to, well, all of our problems. For example, he says, "We need a proper balance between government spending on nursing homes and nursery schools — on the last six months of life and the first six months of life." Despite the nice ring, that's about as empty a statement as you can make about public policy.

But this is the one that really confused me (and my friend):

"The first is a grand bargain to fix our long-term structural deficit by phasing in $1 in tax increases, via tax reform, for every $3 to $4 in cuts to entitlements and defense over the next decade."

Where does this $3–4 in spending cuts to $1 in tax increases come from? To put this in perspective, over the next decade, the CBO's alternative scenario (the more realistic one) says that deficits will average 5.3 percent of GDP over the next decade. A major deficit reduction agreement would need to bring this down at least to 2 percent of GDP.* Friedman is basically saying that taxes should go up by about 0.7 percent of GDP and spending should come down by about 2.6 percent. Over the next decade, the Bush tax cuts, if extended, will reduce tax revenues by 2.2 percent of GDP.** So Friedman is really saying that the appropriate level of taxes should be well below Clinton levels and slightly above Bush levels.

In addition, these ratios of tax increases to spending cuts are essentially meaningless. Take Medicare, for example. We could increase the Part B premiums paid by high-income beneficiaries, which, according to conventional federal government accounting, would count as a spending cut. Or we could make Medicare benefits taxable for high-income beneficiaries, which would count as a tax increase. But the two would have exactly the same effect. About two-thirds of all federal spending is direct payments on behalf of individuals (e.g., Social Security checks and Medicare reimbursements). Reducing a direct payment to someone is the exact same as increasing her taxes.

In White House Burning, we propose large reductions in long-term deficits through a long list of policy changes. Many of our proposals count as tax increases from the accounting perspective. For example, we recommend eliminating or scaling back tax breaks for employer-provided health care, mortgage interest, charitable giving, and state and local government borrowing, all of which are implemented through the tax code. All of these tax breaks, however, are really government subsidies, so reducing them should count as spending cuts from an economic perspective.

You may disagree with these proposals, but they should be evaluated based on their impact—not whether they are labeled as tax increases or spending cuts. By buying into this arbitrary distinction, Friedman is really buying into the Grover Norquist view of the world, in which the only number that matters is total tax revenues.

Finally, however, what's so great about balance? There is a political rationale for the perception of balance, which is that you can't pass anything that appears to favor one side by too much unless you control the White House, the House, and sixty votes in the Senate. But there's no particular reason why the pursuit of balance will produce good policy. To take a particularly vacuous example, Friedman says:

"Within both education and health care, we need grand bargains that better allocate resources between remediation and prevention. In both health and education, we spend more than anyone else in the world — without better outcomes. We waste too much money treating people for preventable diseases and reteaching students in college what they should have learned in high school."

Is he saying that we should improve high school education (who's against that?) but that, to "balance" this improvement, we should have worse college education?

Friedman concludes, "We can't have any of these bargains, though, without a more informed public debate." Fetishizing balance as an end in itself, in order to brand himself as a reasonable centrist who wishes we could all get along, is not going to get us there.

* If you look at the long term, we think that average deficits will have to come down by 5.5 percent of GDP; details are in chapter 6 of White House Burning.

** According to the CBO, the Bush tax cuts are worth $4.4 trillion over the next decade (Table 1-6; that's the incremental effect of the tax cuts on top of indexing the AMT) while GDP will be $202 trillion (Table 1-3).

Responsible Populism

By Simon Johnson

"Populism" is a loaded term in modern American politics. On the one hand, it conveys the idea that someone represents (or claims to represent) the broad mass of society against a privileged elite. This is a theme that plays well on the right as well as the left – although they sometimes have different ideas about who is in that troublesome "elite."

At the same time, populism is often used in a pejorative way – as a putdown, implying "the people" want irresponsible things that would undermine the fabric of society or the smooth functioning of the economy.

In Latin America, for example, there is a long tradition of populists falling into bed with a corrupt political elite, and the results invariably include irresponsible macroeconomic policies and various kinds of financial disaster (see "The Macroeconomics of Populism in Latin America," edited by Rudiger Dornbush and Sebastian Edwards).

In North America, however, the populist tradition has proved much more constructive. More than 100 years ago, hot-button issues included direct election of senators and a federal income tax. None of these demands seem irresponsible today, and achieving those goals through constitutional amendments in the run-up to 1914 in no way jeopardized American prosperity.

But there is still an undercurrent of resistance in Washington to policy ideas with widespread popular support. For example, when President Obama said to leading bankers in March 2009, "My administration is the only thing between you and the pitchforks," he was suggesting that people favoring a resolution process for large financial institutions – closing them down in an orderly fashion – were akin to some kind of a peasants' revolt.

According to Mr. Obama's framing of the issues, the administration sided with large banks that were in trouble at the beginning of his administration – and bailed them out repeatedly and on generous terms – because this was the responsible thing to do.

This was a mistake, with lasting consequences for the American economy, because it further entrenched the power of these banks and the people who ran them into the ground. It also changed our politics. On financial regulation, anti-elite ideas have broad appeal and represent the responsible course of action – and they should draw support from across the political spectrum. Populism and irresponsibility are not, in fact, synonyms. When any elite gets out of control and makes egregious financial mistakes, which happens in many societies, the choice is either to rein them in or provide them with unlimited state backing. You can imagine which course is preferred by that powerful elite and, not surprisingly, the "capture the state" approach is often what leads to the most trouble – including irresponsible macroeconomic policies, worsening inequality and further rounds of traumatic crisis.

In their new book, "Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity and Poverty," Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson suggest that most economic and political collapse is caused by overly powerful elites – which bring on a wide variety of pathologies.

In early 2009, the people who wanted to arrange the orderly liquidation of failed banks in the United States included Sheila Bair, the entirely reasonable and middle-of-the-road head of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. Ms. Bair was also an outspoken advocate of higher capital requirements and meaningful financial reform more broadly.

According to the definitive account published recently by Jesse Eisinger of ProPublica, she was opposed and largely thwarted not just by top political appointees (e.g., at the Treasury) but also by the Federal Reserve.

Ms. Bair is a Republican; at one point she worked for Senator Bob Dole of Kansas. But she draws broad bipartisan support for standing up to the banks and consistently proposing a more responsible course of action than that preferred by the banking elite. I have heard sensible people on both sides of the political aisle suggesting that she would make a very fine Treasury Secretary, and I agree with that assessment.

Elizabeth Warren is another prominent public figure who stands for reasonable constraints on egregious bad behavior by powerful financial interest groups. Ms. Warren was chairwoman of the Congressional Oversight Panel for the Troubled Asset Relief Program, or TARP, and in that capacity she drew broad bipartisan support for her even-handed assessments.

When she helped set up the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Ms. Warren stood primarily for greater transparency in financial transactions, making it easier for people to understand what they are getting themselves into. Many responsible businesses supported exactly that approach.

This week, Ms. Warren and three other former officials from the oversight panel criticized the way in which the government has helped A.I.G. through nontransparent tax breaks – details of which have only now become public.

As Ms. Warren put it, "When the government bailed out A.I.G., it should not have allowed the failed insurance giant to duck taxes for years to come." She was joined in her condemnation of the administration by Damon Silvers, a Democrat, and J. Mark McWatters and Kenneth Troske, who are Republicans.

Ms. Warren is running for the Senate in Massachusetts and seems likely to be picked as the Democratic nominee. Her opponent, Senator Scott Brown, opposed every dimension of financial reform. I do not recall his support for or even interest in any attempt – by the left or the right (and I've worked with both) – to make banking safer. The issues do not even appear in the policy section of his Web site.

To be clear, Mr. Brown eventually voted for the Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation in 2010, but only in return for the watering down of meaningful changes, "including helping strip out a proposed $19 billion bank tax and weakening a proposal to stop commercial banks from holding large interests in hedge funds and private equity funds." He now draws considerable financial support from Wall Street, where some executives seem willing to do whatever it takes to prevent the election of Elizabeth Warren.

Mr. Brown presents himself as bipartisan – presumably as a way to garner favor with Massachusetts voters. "I'm not a 'rock thrower'" is his line – which is very close to saying "I do not have a pitchfork."

But the people throwing rocks at our economy are not reasonable reformers like Ms. Bair and Ms. Warren. Important parts of our financial elite, particularly the people who ran large financial institutions, went out of control in the run-up to 2008. Powerful bankers wreaked havoc with our economy, destroyed millions of jobs and directly caused a huge increase in the national debt. These people and their successors are now poised to get out of control again.

Two stories in the news on Wednesday speak to the continuing dangers surrounding an unreformed financial sector. The very public resignation of Greg Smith from Goldman Sachs illuminated an insider's view of Wall Street culture and suggested that it has not changed much, if at all, in the past few years.

Even under the most favorable interpretation, the bank stress tests run by the Fed found that some banks are still struggling. I agree with Anat Admati – these stress tests were not tough enough, again raising questions about whether the degree of "regulatory capture" has also changed since the crisis.

The politicians to fear are those like Scott Brown, who refuse to stand up to Wall Street.

March 14, 2012

Who's a Freeloader?

By James Kwak

A year ago, Vanessa Williamson, Theda Skocpol, and John Coggin published a paper based on their in-depth interviews of Tea Party activists. A longer presentation of their research was published as a book a few months ago, and I was reminded of it by historian Daniel Rodgers's review in Democracy.*

Rodgers's review is titled "'Moocher Class' Warfare," picking up on one of their key findings: in general, Tea Party members like Medicare and Social Security, which they think they have earned through their work, but don't like perceived freeloaders who live off of other peoples' work. From the paper (p. 33):

The distinction between "workers" and "people who don't work" is fundamental to Tea Party ideology on the ground. First and foremost, Tea Party activists identify themselves as productive citizens. . . . This self-definition is posed in opposition to nonworkers seen as profiting from government support for whom Tea Party adherents see themselves as footing the bill. . . . Tea Party anger is stoked by perceived redistributions—and the threat of future redistributions—from the deserving to the undeserving. Government programs are not intrinsically objectionable in the minds of Tea Party activists, and certainly not when they go to help them. Rather, government spending is seen as corrupted by creating benefits for people who do not contribute, who take handouts at the expense of hard-working Americans.

Let's leave aside the self-serving nature of this distinction—I deserve my entitlement programs, but you don't deserve yours. Does it even make any sense?

Imagine Alice works from twenty-five to fifty-five making $30,000 per year, more than double the minimum wage. Then she loses her job and goes on Medicaid—a classic "welfare" program. Then imagine Beatrice, who works from twenty-five to sixty-five making $30,000 per year. (For simplicity, let's assume each person goes on benefits in 2012, and those $30,000 are constant 2012 dollars.) Then she retires and goes on Medicare—an entitlement she has "earned," according to Tea Party logic. Assume that each person paid $1,000 in federal income taxes each year. Who's the freeloader?

Each year, Beatrice paid $870 in Medicare payroll taxes. In addition, about 16 percent of her income taxes went to Medicare,** for another $160 per year. So over forty years, she contributed about $41,000. At retirement, she will have a life expectancy of about twenty years. Annual Medicare spending per beneficiary is projected by the CBO to be about $15,000 in 2022 (right in the middle of her benefit period), or maybe $12,000 in 2012 dollars, so she can expect to receive total Medicare benefits of about $240,000. That means her net transfer is about $199,000, or $10,000 per year.

About 21 percent of Alice's federal income taxes go to Medicaid,*** so she contributed $210 per year, or about $6,000. (Let's assume she paid no state taxes, which makes her look worse.) Total federal Medicaid expenditures were $273 billion in 2010; the federal government pays 57 percent of total Medicaid expenses; and there are about 56 million beneficiaries at any one time; so the average cost per full-year beneficiary is about $8,600. 49 percent of Medicaid spending, however, goes to long-term care, even though only 7 percent of Medicaid beneficiaries received long-term care benefits,**** so the average annual cost per non-long-term care beneficiary is about $4,700.***** So between the ages of 55 and 65, Alice's total benefits are worth $47,000, for a net transfer of $41,000, or $4,100 per year. Even if we double her average cost because of her age, we still get net benefits of $88,000, or $8,800 per year.

By now, the answer should be obvious. From the perspective of net benefits, they are both freeloaders. There are a host of approximations in the above calculations, but the bottom line is clear: low- to middle-income workers benefit massively from redistribution in both Medicare and Medicaid. On an annual basis, it seems like Medicare beneficiaries are freeloading even more than Medicaid beneficiaries, primarily because Medicare is more generous and because Medicare beneficiaries are older and hence consume more health care. From a lifetime perspective, however, Alice is a bit more of a freeloader than Beatrice because she will benefit both from Medicaid for ten years and then from Medicare for the rest of her life.

(In the example above, I had Alice work for thirty years and then go on Medicaid for ten. If she worked for ten and went on Medicaid for thirty, you would get similar results. Then her total benefits would be 3 x $47,000 = $141,000, her contributions would be $2,000, her total transfer would be $139,000—still less than Beatrice's total Medicare transfer—are her annual transfer would $4,600. The major driving factor is simply that Medicaid isn't that generous.)

The moral of the story is that if you follow the money, almost everyone is a freeloader; by this criterion, there's no meaningful distinction between Social Security and Medicare, on the one hand, and welfare programs, on the other hand.

But from my perspective, neither Alice nor Beatrice is a freeloader. The right way to look at Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid, in my opinion, is as insurance programs. They protect people against risks that may not materialize until decades in the future (unemployment, disability, death of a spouse, poor health, health care inflation, etc.). When Alice and Beatrice entered the workforce at age twenty-five, neither one could know which of the two would lose her job thirty years later, so they both benefit equally from the existence of Medicaid. I guess if someone never has any intention of working but plans to simply live off of welfare programs you could call her a freeloader, but given the paucity of the current safety net I don't think that's a viable strategy in this country.

As I wrote in yesterday's post, Americans like the things that government spends money on, but they claim not to like government, which leads to our current political mess. In White House Burning, we argue that providing social insurance is an essential and valuable function of the federal government. If people realize that the government's principal activity is protecting them against long-term risks through programs that they already like, they may change their opinions of the government and their willingness to pay for it. We can all dream.

* I have not read the book, but I did read the paper.

** In 2010, general revenue contributions to Medicare were $213 billion, which is 16 percent of total tax revenues, excluding payroll taxes, of $1,298 billion. Those figures are from the OMB Fiscal Year 2012 budget, Historical Tables, Tables 2.1 and 13.1.

*** In 2010, federal spending on Medicaid was $273 billion. That's from Table 11.3.

**** Total Medicaid spending in 2009 was $251 billion (Table 11.3). Long-term care spending was $122 billion.

***** It is appropriate to subtract out Medicaid long-term care benefits because Medicaid is the long-term care safety net for Medicare beneficiaries, so the value of those benefits is the same for Medicaid and Medicare enrollees.

March 13, 2012

Americans Like Regulation

By James Kwak

It's a well-known fact that Americans oppose government spending in the abstract yet favor virtually every government spending program. For example, last April Gallup reported that 73 percent of Americans blame the deficit on excessive spending and 48 percent wanted to reduce the deficit mainly through spending cuts (and 37 percent equally with spending cuts and tax increases). Only a few months before, however, Gallup also reported majorities opposed to cutting spending on anything—even "funding for the arts and sciences"—except foreign aid.* (This is not an isolated poll; see, for example, Washington Post-ABC News, April 2011, questions 14 and 17.)

Most government spending does go to popular programs like Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. I suspected, however, that most Americans would want to cut spending on federal regulatory agencies; I thought that they just overestimated the amount of spending on regulation, which is tiny compared to the large mandatory spending programs. (The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, for example, last year put in a budget request of around $300 million—less than one-one-hundredth of a percent of total federal spending.)

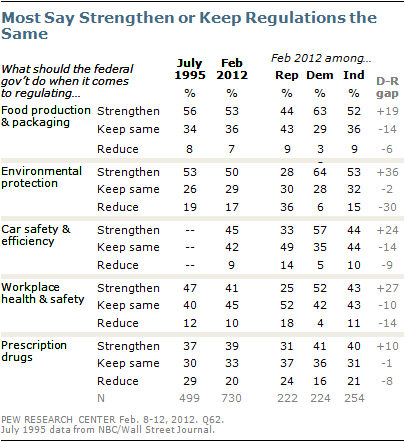

It turns out I was wrong. According to a recent study by the Pew Research Center for the People & the Press (hat tip Harold Meyerson), a small majority (52-40) thinks that government regulation does more harm than good. When you look at every actual type of regulation, however, people wanting stronger regulations vastly outnumber people wanting reduced regulation, and there is little noticeable shift since 1995—another year of intense anti-government sentiment.

So, it turns out, Americans feel about the regulation the same way they feel about government as a whole: they don't like the idea in the abstract, but they like it in concrete form. This shouldn't be too surprising. Of course people want stronger food safety regulations when they read stories about people dying from tainted food; of course they want stronger environmental protections when they hear about toxic groundwater. At the same time, exactly half of the political establishment has been on a crusade to demonize regulation in general for the past forty years.

Now, you can't really blame people too much for holding internally contradictory views about the government spending or about regulation; it's not their job to understand where their money goes or what the government does. That's one reason we wrote White House Burning chapter 4 is basically dedicated to trying to explain where our tax dollars go. Only with that kind of basic baseline understanding can we have any kind of sane discussion of fiscal policy.

* The foreign aid figure is also misleading, since Americans typically overestimate foreign aid spending by a factor of twenty-five.

March 12, 2012

The Politics of Medicare

By James Kwak

The politics of Medicare were aptly summed up by Brad DeLong last May:

"The political lesson of the past two years is now that you win elections by denouncing the other party's plans to control Medicare spending in the long run–whether those plans are smart like the Affordable Care Act or profoundly stupid like the replacement of Medicare by RyanCare for the aged–sitting back, and waiting for the voters to reward you."

This is one manifestation of an important political dynamic, which is an important theme of White House Burning: the smart political bet is to accuse the other side of fiscal irresponsibility while being as irresponsible as possible yourself.

That's the context in which to interpret the latest Republican claims that Barack Obama is trying to end Medicare, reported by Sam Stein. Mitt Romney apparently is accusing Obama of both bankrupting Medicare and of reducing Medicare spending, which are patently contradictory accusations. Yet despite its popularity, the program is so poorly understood that he and his advisers apparently think that they can get mileage out of this line of attack.

To be clear, Medicare costs are rising and projected to continue to grow faster than GDP. But Medicare is largely funded out of general revenues, so the only policy that could actually bankrupt the program is one that reduces general revenues—that is, tax cuts. The Affordable Care Act implemented several measures that are intended to reduce Medicare spending without changing its basic fee-for-service benefit structure; the Independent Payment Advisory Board, which Republicans love to demonize (and which I've written about before), is prohibited by law from making changes that would reduce benefits. In other words, these provisions should reduce spending while maintaining the current benefit structure.

There is a reasonable debate about how successful those measures will be. But you can't simultaneously criticize the ACA for bankrupting Medicare and for cutting Medicare spending too much. And you shouldn't criticize the ACA for bankrupting Medicare when you are pushing huge tax cuts that will undermine the funding for the program.

March 8, 2012

The Koch Brothers, The Cato Institute, And Why Nations Fail

By Simon Johnson

A dispute has broken out between the Cato Institute, a leading libertarian think tank, and two of its longtime backers – David and Charles Koch. The institute is not the usual form of nonprofit but actually a company with shares; the Koch brothers own two of the four shares and are arguing that they have the right to acquire additional shares and thus presumably exert more control. The institute and some of its senior staff are pushing back.

According to Edward H. Crane, the president and co-founder of Cato, "This is an effort by the Kochs to turn the Cato Institute into some sort of auxiliary for the G.O.P." Bob Levy, chairman of the Cato board, told The Washington Post: "We would take closer marching orders. That's totally contrary to what we perceive the function of Cato be."

Far from being just an unseemly row between prominent personalities on the right, this showdown reflects a much deeper set of concerns for American politics and society. And it raises what I regard as the central question of an important book, "Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity and Poverty," by Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson that will be published on March 20.

Professors Acemoglu and Robinson assert that "institutions," by which they mean the rule of law and constraints on government power, are critical to economic development – having great influence on which countries become rich and stay that way, and which countries over the last 200 years have failed to grow or collapsed into civil disorder. (Disclosure: I have done a great deal of joint research with Professors Acemoglu and Robinson, but I wasn't involved in writing this book.)

At one level, the Acemoglu and Robinson argument lines up well with the standard Cato Institute – and libertarian – view of the world. At the back of Cato publications is the statement, "In order to maintain its independence, the Cato Institute accepts no government funding." Without question, excessive power in the hands of governments can be bad for economic growth.

But the Acemoglu and Robinson point is not just about how things may become awful when the government goes off-track (a right-wing point). They are also more deeply concerned about how powerful people fight to grab control of the state and otherwise compete to exert influence over the rest of society (a left-wing perspective).

The outcome to fear is some form of "extractive institutions," meaning a set-up in which most of society is pressed down by working arrangements – e.g., various forms of forced labor – or civil disorder or a more general lack of property rights. They provide many historical and contemporary examples of what this means in their book (and you can see previews of some items, nicely illustrated with photos, on their blog).

"Secure property rights" is a key term for the Cato Institute and others on the right of the American political spectrum – nothing could be more important to a libertarian. But Professors Acemoglu and Robinson trace the development of such property rights in detail to the spread of political rights across a broad cross-section of society, including to people who are not (or do not start their lives among) the well-to-do.

In historical terms, Professors Acemoglu and Robinson see the progressive era at the beginning of the 20th century, including the development of countervailing power for the government against powerful private business interests, as an essential part of what has gone right in the United States of America.

Many libertarians, on the contrary, feel that the country started to go off-track at exactly this moment – for example, some blame the 16th Amendment (introducing the federal income tax in 1913), while others point the finger at the rise of social insurance programs (culminating in Social Security in the 1930s).

Libertarians, such as those who work at the Cato Institute, do not like the state and do not trust the federal government. The Acemoglu-Robinson view is much more nuanced: states are often captured by powerful elites and very much used as a tool of oppression, but it is also possible for liberal democracies to develop in which the government not only helps people but behaves in a way that is conducive to widely shared economic prosperity.

In this context, the Koch brothers are an important topic of discussion — or cause for concern. In the new Bloomberg billionaire index, released this week, the Koch brothers are each worth $33.5 billion. If they choose to act together, as often seems to be the case, including in the case of Cato, they are the richest pair in the world.

Professor Acemoglu is concerned about the Koch's well-organized attempts to exert sway over American politics (e.g., through Americans for Prosperity and its affiliated organizations). But he feels that American democracy is sufficiently strong and will prevail. If he is right, the Koch brothers are unlikely to end up calling the shots as corporate titans did in the Gilded Age at the end of the 19th century (the term was coined in "The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today," by Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner in 1873).

The Acemoglu-Robinson book is ultimately upbeat about the United States. We have built strong economic and political institutions and these will prevail.

I'm not so sanguine. Partly this is because of my work on the rise and continuing power of big banks (including my 2010 book with James Kwak, "13 Bankers"). It's also because of my more recent work on the history and likely future of the federal government budget – and the national debt (as James and I discuss in "White House Burning," which will be out next month). The interests that would undermine government are strong and growing stronger, with rich individuals leading the charge.

Professor Acemoglu feels that a new progressive era will soon be upon us and corporate power will end up curtailed. I'm surveying the political landscape closely for anyone who can play the role of Teddy Roosevelt, using legal tools to break monopoly "trusts" and shifting the mainstream consensus decisively toward imposing constraints on the abuse of power by powerful individuals.

So far, I see no one truly in the Roosevelt tradition with a realistic chance of election, while the rich become more powerful and the powerful become even richer.

Professor Acemoglu and I are debating this and putting forward our competing views of the latest events, on Twitter at present. He's @WhyNationsFail and I'm @baselinescene. Join us there to continue the conversation.

An edited version of this post appears this morning on the NYT.com's Economix blog; it is used here with permission. If you would like to reproduce the entire column, please contact the New York Times.

March 6, 2012

Greg Mankiw's Contorted Defense of Mitt Romney

By James Kwak

It's really hard to defend the carried interest exemption (the one that allows private equity and venture capital partners to pay tax on their share of fund profits at capital gains rather than ordinary income rates). You have to give Greg Mankiw a hand: he sure gave it a good shot in the Times this weekend.

Mankiw's general point makes a lot of sense. He argues that it's sometimes hard to distinguish returns from labor and returns from investment, using five examples of people who buy a house for $800,000 and later sell it for $1,000,000. For example:

"Carl is a real estate investor and a carpenter. He buys a dilapidated house for $800,000. After spending his weekends fixing it up, he sells it a couple of years later for $1 million. Once again, the profit is $200,000."

In this case, although some of Carl's profit is due to his labor, all of it gets treated as capital gains by the tax code. In a perfect theoretical tax world, you would divide Carl into two people, the investor and the carpenter, and the investor would pay the carpenter some amount for his labor; the carpenter would pay ordinary income tax on that amount (and the investor would deduct it from his taxable profits). But that's not how we do things.

The key example, for Mankiw, is the next one:

"Dan is a real estate investor and a carpenter, but he is short of capital. He approaches his friend, Ms. Moneybags, and they become partners. Together, they buy a dilapidated house for $800,000 and sell it later for $1 million. She puts up the money, and he spends his weekends fixing up the house. They divide the $200,000 profit equally."

In this case, Dan pays capital gains tax on his $100,000 in profits because he's part of an investment partnership—even though the thing he contributed to the partnership is labor, not capital. Private equity partners, Mankiw argues, are just like Dan: they enter into a partnership with investors, in which the private equity guys contribute expertise and effort and the investors contribute cash. Hence they should pay capital gains on their share of the profits (usually 20 percent).

But there are two big problems with this argument, one of which Mankiw essentially points out. Mankiw recognizes that Carl is contributing labor, even though the tax code pretends he is just contributing capital. If the basic principle is that the capital gains rate should be reserved for profits from investment activity, not labor activity, it's clear that Carl should pay ordinary income tax on some of his profits; it's just as clear that Dan should pay ordinary income tax on all of his profits.* (That's also the logical result if you think, as many supply-siders do, that the point of lower capital gains rates is to encourage savings; Dan in particular didn't save any money.)

In other words, Mankiw's own examples make it look like Dan is benefiting from a dubious loophole. Then he argues that since private equity partners are doing the same thing Dan is, they should benefit from the same dubious loophole. That's not much of a defense.

The other problem is that private equity partners are not actually like Dan the carpenter. If Dan and Ms. Moneybags are in a true 50-50 partnership, then Dan is on the hook for half of their losses, as well. The great thing about 2 and 20, for private equity partners, is that they get a cut of the profits but they don't absorb a share of the losses. This means that the 20 is more like a performance bonus than like a partnership share. So if the 20 is in a gray area, as Mankiw argues, it is even closer to ordinary income than Dan's partnership share—which, as Mankiw shows (although he doesn't quite come out and say it, for obvious reasons), should be treated as ordinary income.

Still, I don't think you can do a better job than Mankiw does trying to defend the carried interest loophole. Which just shows how indefensible it is.

* The same argument can be made about most stock-based compensation, including stock owned by company founders. If Mark Zuckerberg ever sells any of his bajillion dollars' worth of Facebook stock, he will pay capital gains tax—even though he earned that stock by contributing expertise and labor to the company, not investing his savings in it. As a onetime company founder, I used to think that I was entitled to capital gains tax rates because I bought my shares on day one (for a pittance). But from a substantive perspective, it's clear that mainly what I contributed to the company was labor, not investment. In the end, this is all an argument (though not necessarily a conclusive one) against a distinction between ordinary income and capital gains in the first place.

Simon Johnson's Blog

- Simon Johnson's profile

- 78 followers