Simon Johnson's Blog, page 39

May 8, 2012

Who Pays for Facts?

By James Kwak

The Internet has made possible a golden age of commentary. Anyone with a computer and an Internet connection can create a blog and comment to her heart’s content.

Yet as one of those commenters with a free blog, I am painfully aware that this hypertrophy of analysis has not been matched by corresponding growth in the stuff that we analyze: facts. There is no way we could have written White House Burning, with its one hundred pages of endnotes, without someone else to do the primary research: either the journalistic kind, calling around to sources in Washington to figure out what’s going on, or the data-gathering kind, visiting grocery stores in Brooklyn to track prices and calculate the inflation rate.

So I would just like to second what Menzie Chinn said about the importance of government statistical organizations, which are (along with most of the rest of the government) under attack from Paul Ryan and his troops. Even if you don’t agree with what I say, if you like reading economics blogs, you should realize that they couldn’t really exist without the BEA, BLS, Census Bureau, etc.

Of course, if your economic policy prescriptions are based entirely on pure theory, then I guess you can do without data.

May 7, 2012

Social Security Matters

By James Kwak

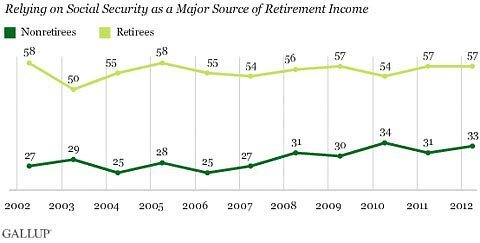

Catherine Rampell wrote a post last week about how Americans expect to retire later and how more elderly Americans are working. Her last chart also showed that a growing proportion of nonretirees expect Social Security to be a major source of their income in retirement.

That shows that Americans are becoming more realistic. But still, just 33 percent?

Just how important is Social Security, anyway? Let’s look at some numbers. Around 2003, Barbara Butrica, Howard Iams, and Karen Smith analyzed the composition of household income for people at age 67. They projected that median-income early baby boomers, when they reached 67, would have mean per capita family income of $33,000 (Table 3), of which Social Security made up $13,000, or 40 percent. Does 40 percent qualify as a “major source” of income? I would say so. Imagine losing 40 percent of your income.

But Social Security is actually more important than that. Remember, these are 67-year-old people, and 49 percent of them are still working. Yet most people hope to stop working someday. If you subtract out earnings, imputed rental income (the non-cash benefit you get from living in a house you own), and co-resident income (earnings of younger family members who happen to live with you), you’re down to a total of $23,000, of which Social Security is now 57 percent.

Another way to look at Social Security is to compare it to the things that, in some people’s eyes, were supposed to make it unnecessary: 401(k) plans. In the projection, for early baby boomers (people retiring now), about half were expected to have defined benefit pensions and the other half were expected to have individual retirement accounts like 410(k)s and IRAs. The latter group are getting about $4,000 from those retirement accounts. That could go up; maybe people are withdrawing less while they are still working. It could also go down; maybe people are withdrawing money at an unsustainable rate. But in any case it isn’t much, and it’s not even close to what Social Security contributes. (Remember, the Social Security figure of $13,000 also doesn’t include people who have chosen to delay taking benefits until after age 67.)

In 2008, Andrew Biggs and Glenn Springstead did a similar analysis, with similar results. Social Security provided 41 percent of income for beneficiaries ages 64–66 (Table 5), but when you strip out earnings and co-resident income, that figure goes up to 53 percent.

Both of these analyses focus on people in their 60s. As people get older, it seems that they rely on Social Security even more—not only because they stop working, but probably because they exhaust their other assets, or because their other pensions are not indexed for inflation (unlike Social Security). According to Sylvia Allegretto, if you look at retirees in the middle of the income distribution in California, a full 70 percent of their income comes from Social Security, with only 16 percent coming from retirement funds.

There’s a lot of talk today, some of it coming from Simon and me, about how the federal government is in danger of running out of money. But at least the federal government has some pretty potent options, like raising taxes. But American families as a whole are also running out of money, and they don’t have a lot of options. That’s a major reason why now is not the time to dismantle our social insurance programs.

May 3, 2012

Mitt Romney And Paul Ryan’s Budget

By Simon Johnson

The conventional wisdom in American presidential politics is that once a candidate has secured a party’s nomination, he tends to move away from articulating the views of the party faithful toward the political center. This makes sense as a way to win votes in the general election, and there has been a presumption that Mitt Romney will head in that direction.

However, in a panel discussion on Tuesday, Vin Weber, a senior adviser to Mr. Romney, indicated that the campaign may be moving toward positions on fiscal policy that are close to those proposed by Representative Paul D. Ryan of Wisconsin and his Republican colleagues on the House Budget Committee.

To be sure, when Mr. Ryan presented his budget in March, Mr. Romney described it as “marvelous”. In the Wisconsin primary, Mr. Ryan campaigned with Mr. Romney and speculation arose that Mr. Ryan might be the Republican vice presidential candidate.)

Yet Mr. Romney’s embrace of the Ryan plan during the general election campaign would represent a significant shift toward a much more extreme view on the future of government than many Romney proposals during the primaries (see this assessment of his primary proposals by the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget). Mr. Weber said he was not speaking for Mr. Romney; I was on the same panel, and my strong impression is that Mr. Weber was floating trial balloons.

Mr. Ryan’s proposals would substantially phase out the federal government’s role in providing basic social insurance for older people by massively reducing Medicare and by eliminating almost all nonmilitary discretionary spending. The House Budget Committee is also proposing to remove the only safeguard we have against the failure of another mega-bank. Some libertarians praise these proposals. But these Republicans’ strategy is not so much to remove government in favor of abstract “markets” but to shift the balance of power away from government and toward entrenched private lobby groups, particularly in the health-care sector and on Wall Street.

On Medicare, Mr. Ryan’s proposal is very simple. He wants to cap increases in spending on Medicare below the rate at which health-care costs increase. By his own estimates, the share of Medicare spending relative to the size of the economy would shrink dramatically over the coming decades. (Mr. Ryan proposes to keep Medicare in place for people currently retired and soon to reach the eligibility age of 65, so his proposal would affect people 55 and under today (I, by the way, am not yet 55).

Mr. Ryan’s approach certainly reduces this dimension of government spending over time. But keep in mind how the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office has assessed these ideas: according to the C.B.O., this approach would increase total health-care costs as a share of the economy and as paid by you (see Figure 1 in this C.B.O. document, which analyzes the proposal Mr. Ryan presented last year; while some details are different this year, the essential substance is the same).

The idea behind this C.B.O. scoring is simple. At present the government buys health care for about 100 million Americans. Certainly, the government could use this buying power more effectively as a way to hold down costs. The government has much more market power than you or I would have relative to health-care providers and insurers when we are in our 70s, 80s and 90s.

The C.B.O. scoring is based on actual experience, including administrative costs in Medicare compared with private insurance. These costs will fall directly on older Americans and their families.

Before Medicare was created in the 1960s, there was no meaningful health-care insurance for older Americans – and there will be none after Medicare is phased out. For the private sector, this is a set of uninsurable risks.

The federal government provides a minimum level of social insurance to all of us, in case we outlive our assets and our families’ ability to support us. Mr. Ryan – and now perhaps Mr. Romney – would end this role.

According to the C.B.O., the net impact would be to increase what you pay for health care. The government-provided piece would decline, but your insurance premiums and other out-of-pocket expenses would increase.

Just as striking is Mr. Ryan’s proposal for nonmilitary discretionary spending. This currently amounts to about $650 billion, about 4 percent of gross domestic product, and it has been around this size relative to the economy for about 50 years.

This now represents about 20 percent of federal government activity. The federal government is roughly a $3.3 trillion shop, annually, with the big chunks of spending being Social Security, Medicare and other government-backed health care, and the military. The United States economy has a total annual production, or G.D.P., of about $15 trillion.

Mr. Ryan is less clear on the details, but assuming that he would seek to maintain military spending at no less than 3 percent of G.D.P. – which is its lowest level in the postwar period – my colleague James Kwak has projected that the domestic discretionary spending would fall to almost zero in the coming decades (see the charts at the end of this blog post).

I’m all in favor of bringing the federal debt under control – and stabilizing it at a reasonable level relative to the size of the economy (say, 40 or 50 percent of G.D.P.). But there is no need to eviscerate the federal government in order to achieve this over a reasonable time frame.

Mr. Ryan’s plan would effectively shut down the federal government’s ability to set rules for the economy and to provide essential public services, such as air-traffic control, the monitoring of hurricanes and the provision of disaster relief.

Big private companies will no doubt do well under this approach; there will be less restrictions on what they do (e.g., as the Environmental Protection Agency winds down or food-safety rules go unenforced), and they will be able to increase their market power (as the Department of Justice drops its remaining interest in antitrust issues).

This is bad news for entrepreneurs or anyone seeking to invest in start-up companies. The playing field will become ever more uneven – just as it was when J.P. Morgan and his colleagues were building the original industrial, railroad and energy trusts at the end of the 19th century.

From the perspective of too-big-to-fail banks, the news from Mr. Ryan is even better. The House Republicans are proposing to repeal Title II of Dodd-Frank, which creates the legal authority to wind down large financial institutions in an orderly fashion.

Without this, we are back at the situation of fall 2008, where big banks can blow themselves up, inflict great damage on the economy and also receive large-scale bailouts (see my recent post in this space for more on exactly how that works).

None of these Republican proposals should be dismissed as pure rhetoric. For many Republicans in Congress, the Ryan proposals are a very real agenda. And, as Ezra Klein has argued, if Mr. Romney is elected president, the Republicans are likely to gain control of the Senate and would almost certainly be able to push through a version of the Ryan agenda – particularly as the key details would be immune to filibuster in the Senate.

Under such a Ryan-Romney approach, big risks – such as severe ill health and the danger of other calamities – would be shifted from society to individuals. Large corporations in health care and finance and perhaps in other sectors would benefit. So, too, would the people who control those favored legal entities.

This is a return to the way the United States economy operated more than 100 years ago – in what Mark Twain ironically labeled the Gilded Age. A few people would do very well; almost everyone else is in for a hard time.

An edited version of this post appeared this morning on the NYT.com’s Economix blog. It is used here with permission. If you would like to reproduce the entire post, please contact the New York Times.

May 1, 2012

Stephen King Weighs In

Great article by Stephen King (hat tip Felix Salmon/Ben Walsh). Excerpt:

“The Mitch McConnells and John Boehners and Eric Cantors just can’t seem to help themselves. These guys and their right-wing supporters regard deep pockets like Christy Walton and Sheldon Adelson the way little girls regard Justin Bieber … which is to say, with wide eyes, slack jaws, and the drool of adoration dripping from their chins.”

Like me, King wants his tax bill to go up.

April 30, 2012

My Daughter Will Be CEO of the World’s Most Valuable Company Someday

By James Kwak

At least, that’s the impression I get from reading Walter Isaacson’s biography of Steve Jobs, which I finally finished this weekend. It’s not a particularly compelling read; it basically marches through the stages of his professional life, which is already the subject of legend, so there isn’t much suspense. I fear that it will inspire a new generation of corporate executives to imitate all of Jobs’s personal shortcomings—but without his genius.

The picture you get from the book is basically that Steve Jobs acted like a five-year-old for his whole life. He could be wrong about some basic, uncontroversial fact yet insist stubbornly that he was right. He divided the world into things that were great and things that were terrible, and his classifications could be arbitrary. He was an obnoxiously picky eater, constantly complaining about his food and sending it back. He threw epic tantrums that only a CEO (or a five-year-old) could get away with.

Some of his flaws, however, took more self-deception than a five-year-old is capable of. For example, when he came back to Apple in the late 1990s, he insisted he wasn’t in it for the money and took the famous $1 salary. When the board offered him stock, he said he would rather have an airplane. The board gave him a Gulfstream V and 14 million options—and Jobs insisted on 20 million (which he got). When the stock market crashed, he got them repriced (leading to the Apple backdating scandal), and when the stock price kept falling, he eventually traded them in for an outright stock grant. Now, this is the behavior you expect from corporate CEOs, but it’s a bit galling coming from someone who insisted, very publicly, that he didn’t care about money.

For a similar example, Jobs refused to have a dedicated CEO parking spot at Apple headquarters—but he regularly parked in handicapped spots. What kind of a person does that?

But, of course, the results speak for themselves. And Isaacson’s biography displays some of the traits that made Jobs such a successful businessman. He could have immense personal charm, when he wanted to. As Steve Wozniak said, “Steve could call up people he didn’t know and make them do things.” That ability, to get on the phone and talk someone else into do something that isn’t in her interests, is what I consider the most important skill in business.

Jobs was also incredibly opinionated about his products, and his opinions were usually right. He was a compulsive micro-manager who almost always got his way, and the result is the world of personal computing we see around us, from touchscreen phones to the rounded windows in desktop operating systems.

What you don’t see is any of the conventional management mumbo-jumbo that big-company CEOs spout to justify their fortunes—nothing about focusing on people, mentoring, creating a supportive work environment, giving people freedom but making them accountable, leading by following, etc. As I’ve said before, Steve Jobs violated just about every rule of generic company management. He succeeded because he had great product instincts, he was incredibly convincing, he was inspiring enough to get some great people to work for him, and he was a little bit crazy. In other words, he was the farthest thing you could find from the generic corporate executives who rule most of the business world.

April 26, 2012

American Taxpayer Liabilities Just Went Up, Again – Why Isn’t Congress Paying Attention?

By Simon Johnson

Most Americans paid no attention this weekend when the International Monetary Fund announced it was well on its way to roughly doubling the money that it can lend to troubled countries – what the organization calls a $430 billion increase in the “global firewall.”

The United States declined to participate in this round of fund-raising, so the I.M.F. has instead sought commitments from Europe, Japan, India and other larger emerging markets.

At first glance, this might seem like a free pass for the United States. The additional I.M.F. lending capacity is available to euro-zone countries that now face pressure, such as Spain or Italy, so it might seem that global financial stability is increased without any cost to the American taxpayer.

But such an interpretation mistakes what is really happening – and actually represents a much broader problem with our budgetary thinking. The I.M.F. represents a contingent liability to taxpayer sin the United States – much as the Federal National Mortgage Association (known as Fannie Mae) and Freddie Mac (formerly the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation) have in the past — and as too-big-to-fail mega-banks do now.

The budgetary consequences of all those government-supported enterprises are known as “contingent liabilities” – simply meaning that, when something goes wrong, the taxpayer is on the hook. (If you believe any of these guarantees are costless, please read the new book James Kwak and I wrote.)

The I.M.F. is not a corporation nor does it exactly resemble any other legal entity you are likely to encounter. To understand the way in which the American taxpayer is on the hook, focus on the fact that, like any corporation, the I.M.F. finances its activities with a combination of equity and debt.

Traditionally, the I.M.F. was funded mostly with “equity” – contributions paid in by member governments. In the 1940s, when the organization was created, the United States paid in dollars and gold (this was when gold was the mainstay of the international payments system). Other countries have also paid in gold, as well as in acceptable “strong” currencies.

According to the I.M.F. Web site: “The I.M.F.’s gold holdings amount to about 90.5 million troy ounces (2,814.1 metric tons), making the I.M.F. the third largest official holder of gold in the world.”

(On Tuesday, gold was trading around $1,640 a troy ounce, so the market value of the I.M.F.’s holdings was close to $148 billion. For more detail, including on how countries might get back “their” gold, see this fact sheet.)

More recently – and particularly since 2009 – the I.M.F. has increased its lending capacity not so much through additional equity (known as “quota” in I.M.F. jargon) but through debt. In effect, the I.M.F. is borrowing from some countries in order to lend to other countries.

There is a simple reason for this switch. The I.M.F. quota comes with voting rights – and these are currently skewed toward those countries that held the balance of power in the 1940s and 1950s (the I.M.F. was created in 1944). The United States has a veto, and the Europeans are overrepresented.

Now, the emerging markets, like China and the oil producers, have the cash reserves. Emerging markets would be happy to get more quota at the I.M.F., but there is no way that Europe or the United States and its allies would be comfortable with a big shift in who is calling the shots within the international monetary system.

But there’s the catch and to see it, think about the European Union’s recent decision to lend 200 billion euros (about $260 billion) to the I.M.F. If the E.U. lends to European countries under duress, it could lose this money, in the event of a complete default. But if the E.U. lends to the I.M.F. and the I.M.F. lends to stressed European countries, then the E.U. has some downside protection – from I.M.F. shareholders.

In the event of default or complete nonpayment on official borrowing, including loans from the I.M.F., the losses would be borne in the first instance by shareholders. In this sense the I.M.F. is like a bank, with loss-absorbing shareholder capital. If that capital were exhausted by losses, then the I.M.F. would be unable to pay back what it in turn had borrowed.

Some officials assert that none of this could happen, because the I.M.F. always gets paid back – one way or another. Certainly that has been the pattern in the past, but then again we have not seen this level of stress on the international system at least since the 1930s, when all the rules were torn up repeatedly.

A major euro-zone meltdown would cause severe damage around the world. Anyone who thinks otherwise has not been paying attention.

Over the weekend, the I.M.F. became a lot more leveraged – that is, its debt increased relative to its equity. The potential future liability to American taxpayers went up, because the risk of large credit losses increased, and those losses would need to be covered by shareholders (and our stake in the fund is 17.69 percent of quota, with 16.8 percent of the votes). There is also an implicit guarantee – arguably without limit – from the US to the IMF. We set up the world trading system after World War II, and we have a huge amount to lose if it fails. We also have deep pockets, compared to almost other countries.

Therefore, unlike with a typical corporation, we the shareholders in the IMF do not have limited liability – so we should care a great deal about the downside risks. The Europeans are currently increasing those risks – by lending to the I.M.F. and planning to use I.M.F. loans as part of future bailouts.

The Congressional Budget Office is getting better at scoring contingent liabilities, including United States obligations to the I.M.F., but there is still a lot more work to do. It’s time for Capitol Hill to pay more attention to the implications for the United States budget (and therefore the likely path for our national debt) of what is happening at the I.M.F. – points also made by Desmond Lachman in recent congressional testimony (see points 12-16 here.)

Do not take the statements of global leaders at face value. Congressional leaders on both sides of the aisle should begin by asking the C.B.O. to update its scoring of American commitments – explicit and implicit – to the fund.

An edited version of this material appeared this morning on the NYT.com’s Economix blog. It is used here with permission. If you would like to reproduce the entire post, please contact the New York Times.

April 18, 2012

About That State and Local Tax Deduction

By James Kwak

A couple of days ago I criticized Mitt Romney for thinking that eliminating the deductions for mortgages on second homes and for state and local taxes would pay for his 20 percent rate cuts. But there’s a more important general point to be made.

The deduction for state and local taxes is a subsidy from the federal government to state and local governments. This is how it works: If you’re in the 35 percent tax bracket, for every $100 of taxes you pay to state and local governments, the federal government gives you $35. In other words, for every $100 of taxes levied, you pay $65 and Barack Obama pays $35. That’s called a subsidy. Without it, the state and local governments would only get $65—or they would have to raise taxes by over 50 percent, which would make you mad.

So eliminating this deduction basically transfers money back from states and municipalities to the federal government. The federal budget deficit goes down, but state and local budget gaps go up—meaning either higher taxes or lower services. (And these are the levels of government that pay for teachers, police, firefighters, etc.) So this is one of those solutions that helps the federal budget balance by hurting ordinary people.

That said, I still think we should get rid of the deduction because it’s a highly inefficient subsidy. It mainly benefits rich people because poor people tend not to itemize their deductions. (Their deductions aren’t big enough to be worth itemizing.) Since state taxes are not very progressive to begin with, this makes them even less progressive, or even regressive. Massachusetts, for example, basically has one tax rate—5.3 percent—so people who take the deduction are paying a lower effective rate than people who don’t take the deduction.

In addition, rich towns get bigger subsidies than poor towns, simply because they have higher property values and hence people pay higher property taxes. If Greenwich needs more money for its schools, it can increase property taxes. Residents might grumble, but they know that for every $2 they pay, the federal government is kicking in $1. In Hartford, not so much.

For these reasons, in White House Burning we recommend phasing out the state and local tax deduction entirely (p. 212). In order to reduce the damage to state and local finances, however, we recommend using half of the proceeds to fund direct grants to states and municipalities. If this were done using a population-based formula, the effect would be to reduce subsidies to Greenwich much more than to Hartford; it might even increase the amount of federal aid to poor cities, where relatively few people take the deduction today.

If, by contrast, you simply axe the deduction, you’re just transferring money from one level of government to another. At the least, that’s a problem you need to acknowledge—unless it’s a feature, not a bug.

Margaret Atwood And Tax Reform

Writing recently in The Financial Times, the renowned novelist Margaret Atwood nailed the lasting effects of the recent – and some would say continuing – global financial crisis. “Those at the top were irresponsible and greedy,” she wrote; consequently and with good reason, very few people now trust our banking elite or the system they operate. Even Cam Fine, president of Independent Community Bankers of America, is now calling for the country’s largest banks to be broken up.

But the distrust goes deeper and further, just as Ms. Atwood implies. Many people understand perfectly well that the government let the bankers take excessive risk. There was a high degree of group think among prominent officials in the United States and top banking executives in the run-up to the crisis of 2008. As chief economist at the International Monetary Fund from March 2007 through August 2008, I observed some of this first hand.

And politicians are also tarnished. They appointed the officials who failed to regulate effectively. And in 2007-8 the politicians decided to save the big banks – and most of their managers, boards of directors and shareholders – both under President George W. Bush and under President Obama. Now attention turns toward the federal government’s fiscal problems, including the complicated mess that is our tax system. Politicians say they want “tax reform,” but can you trust them to do this in a responsible manner, without falling captive to particular special interests or to otherwise undermine the general social interest?

The latest indications from Mitt Romney are not encouraging. Mr. Romney is proposing to implement a tax overhaul that he says would be revenue neutral. But his actual plans amount to cutting tax rates, particularly for high-income people, while not closing enough loopholes to make any difference (see this assessment by my colleague and co-author James Kwak, or this take by Matthew O’Brien of The Atlantic).

At the same time, President Obama is focused on increasing taxes for relatively well-off Americans. Mr. Obama wants to make the Bush-era tax cuts permanent for people earning less than $250,000, while not extending them for people with income above that level. What exactly will control the trajectory of deficits and debt in that scenario?

Perhaps we should trust our politicians to control future health-care spending, even though none of them can specify exactly how this should be done. But what is really likely to happen given that health-care providers – hospitals and doctors — are a powerful lobby, while insurance companies may be even stronger.

All significant loopholes, including the tax exemption of employer-provided health benefits and the tax deductibility of mortgage interest payments, will be defended fiercely by powerful special interests.

Top military officials seem willing to curtail spending, but members of Congress frequently resist base closings and the cancellation of weapons programs. President Eisenhower famously warned against the military-industrial complex; perhaps we should update that to acknowledge that it’s the industrial-political complex that’s the danger.

The financial crisis blew a giant hole in our budget and, with good reason, greatly undermined confidence in our political elite. Gridlock in Washington has reached a new peak – President Obama proposed the Buffett Rule, which would have raised a very small amount of additional revenue by creating a minimum tax rate of 30 percent on all income over $1 million, and the Republicans immediately blocked consideration of it in the Senate.

Most of what poses as “tax reform” in Washington today is actually tax reduction. With our public finances in their current state, this is the last thing we need. The idea that reducing taxes “pays for itself” through higher growth is just wishful thinking; in our new book, James Kwak and I debunk this in part by citing the research of Greg Mankiw, former chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers under George W. Bush and a key adviser to Mr. Romney. Yet Mr. Romney and Mr. Obama are likely to compete in November partly on the basis of their tax reduction proposals.

May we hope that there are ways to bring our national debt under control? Prospects are not so gloomy, for two reasons.

First, if true gridlock prevails, the Bush-era tax cuts will expire at the end of this year. Whatever happens in the November general election, the Democrats and the Republicans would need to agree in order for these tax cuts to be extended. It is quite possible that this will not happen.

That’s a big fiscal adjustment, to be sure. But it could well be buffered by a temporary payroll tax cut, linked to employment relative to population. As employment recovers, the payroll tax cut would fade away.

Second, one day soon the private sector will wake up to the fact that rising health-care costs are undermining the American economy, and making it much harder to earn a profit.

With money-driven politics, the only way to fight a lobby is with a bigger lobby. American businesses are typically reluctant to trespass into someone else’s sector. But they will do it when their own bottom line is at stake – as, for example, when they resist various forms of protectionism.

Health-care costs are not under control; we pay more for the same or less-good services over time; this is like the worst kind of taxation. In 20 years, the adverse impact of health-care costs of businesses will be much worse than any negative effects of taxes.

But don’t wait for the politicians to take this on. The problem is far too important and that route will take too long. Talk instead to private-sector executives and entrepreneurs. Persuade them that health-care costs need to be brought under control, and force them to think about how they can push the health-care industry in this direction.

Don’t leave banking regulation to be decided by the banks. And don’t let the health-care industry control the discussion on what needs to be changed in cost of the delivering medical services.

Cam Fine is now willing to take on the big banks – he should be commended and supported more broadly on this basis. By working on this issue at the highest political level, he can help restore grass roots confidence in community banking.

Who within the private sector is willing to take on the healthcare lobby? Who will take the lead on restoring trust in our market-based economy more broadly?

An edited version of this post appeared this morning on the NYT.com’s Economix blog; it is used here with permission. If you would like to reproduce the entire post, please contact the New York Times.

April 16, 2012

Mitt Romney Still Can’t Do Arithmetic

By James Kwak

From his closed-door fundraiser yesterday, courtesy of NBC:

“I’m going to probably eliminate for high income people the second home mortgage deduction,” Romney said, adding that he would also likely eliminate deductions for state income and property taxes as well.

“By virtue of doing that, we’ll get the same tax revenue, but we’ll have lower rates,” Romney explained.

Let’s check Romney’s arithmetic.

The home mortgage deduction was worth $22 billion to households making over $200,000 in 2009. Even if half of that was attributable to second houses—and the actual figure is certainly less—that gives you $11 billion. The deduction for state and local income taxes was worth $20 billion for those same households. So together you get a total of $31 billion.

The top 1% paid about 36 percent of individual income taxes in 2009, which were $915 billion. So they paid $329 billion in individual income taxes.

Even if we assume that all $31 billion in benefits from the deductions for interest on a second home and state and local taxes went to households in the top 1%—an unrealistic assumption, since the cutoff for the 1% is far above $200,000—that only brings their taxes up to $360 billion. Factor in the 20 percent across-the-board cut in rates that Romney has promised, and their taxes fall to $288 billion. Net, that’s a $41 billion reduction. On top of that, you have to add Romney’s proposed reduction in corporate income taxes, since the rich pay a large proportion of corporate income taxes, at least according to the Tax Policy Center and the CBO.

Republican tax cut plans fall into two categories: the ones that don’t bother pretending that they’re going to be revenue neutral and the ones that do. But the latter can never make the numbers add up because you can’t have massive rate cuts and be revenue neutral unless you’re willing to eliminate popular tax expenditures for the middle class, the preference for investment income (the most important tax break for the rich people who pay for Republican politicians’ campaigns), or both.

This is the guy who’s supposed to be the hard-headed businessman?

Update: The title is a reference to this Atlantic column, which shows that there just aren’t enough tax expenditures to balance out the huge rate cuts that Romney has promised to the 1%.

The Buffett Rule Is A Good Idea

By Simon Johnson

Some high income Americans pay a lot of tax; others do not. If you have right tax advice and if most of your income can be structured as some form of “capital gains”, your marginal rate – what you pay on the your last dollar of income – may be very low. The highest marginal income tax rate currently is 35 percent, while long-term (over a year) capital gains are taxed at 15 percent at most.

The Buffett Rule is a proposal is establish a minimum tax rate for “millionaires” – people earning more than $1 million per year – and the Senate is likely to vote on a version this week. The exact amount of revenue that this would bring in depends on the details, but there is no question that it is small relative to the country’s need to control the federal budget. (The Joint Committee on Taxation scored one version of this proposal as generating about $30 billion over ten years; the annual budget deficit will remain over $1 trillion in the near term even under the most optimistic projections.)

The biggest sticking point for any reasonable strategy to control the US federal budget is that one side – the Republicans – steadfastly refuse to raise taxes, at all and on anyone.

There are three ways forward. Either the Republicans begin to compromise – and agree to raise taxes as part of a comprehensive deficit reduction and debt control strategy, just as Ronald Reagan did. There is a great deal of confusion about whether Reagan raised taxes after first cutting them; see chapter 3 of White House Burning for the details of what actually happened.

Or the Republicans who have signed the Taxpayer Protection Pledge will prevail – no one’s taxes will go up and, most likely, some people’s taxes will go down. In this case, either the deficit will continue to grow (which is what Newt Gingrich is proposing) or Medicare and almost everything else the federal government does will be scrapped (which is the position represented by Paul Ryan). My guess is that, in this scenario, we will say farewell to any meaningful form of social insurance – good luck getting healthcare when you are 85 (unless you earned over a million dollars a year for many years).

Or the Republicans will lose big – and fiscal consolidation can proceed without them.

A complete loss of support for the Republicans seems unlikely – they will surely hold more than 40 seats in the Senate for the foreseeable future.

So the fiscal trajectory of the country – and whether Social Security and Medicare survive – depends very much on whether the Republicans will compromise on taxes.

The Buffett Rule is a tiny tax, of little consequence to the people who would pay it or to the country as a whole. The idea that $30 billion of additional revenue would tip the balance in any way is simply ludicrous.

But this is precisely what gives the Buffett Rule its powerful symbolism.

Much of federal government public finance is complex and hard for people to comprehend – demystifying deficits and debt is a major reason we wrote White House Burning. Some of the reaction to our book is encouraging, particularly from people who are willing to spend some time with the details.

But the question behind the Buffett Rule is crystal clear and does not require you to buy a book or even read the newspaper. Should all high income Americans pay a moderate level of tax?

Simon Johnson's Blog

- Simon Johnson's profile

- 78 followers