Simon Johnson's Blog, page 44

February 24, 2012

Party of Higher Debts

By James Kwak

The Committee for a Responsible Budget recently released an analysis of the budgetary proposals of the four remaining Republican presidential candidates (hat tip Ezra Klein, who shows the key graph). In short, all of the candidates propose to increase the national debt by massive amounts relative to current law, which includes the expiration of the Bush tax cuts at the end of this year.

CFRB compares the candidates' plans to a "realistic" baseline that assumes the Bush tax cuts are made permanent and the automatic sequesters required by the Budget Control Act of 2011 are waived, among other things. Relative to that extremely pessimistic baseline, Santorum and Gingrich still want huge increases to the national debt; only Paul's proposals would reduce it. Romney's proposals would have little impact, but that was before his latest attempt to pander to the base: an across-the-board, 20 percent reduction in income tax rates.

How is this possible, since all of them have promised to cut spending? Huge tax cuts, on top of the Bush tax cuts. Romney, as mentioned above, would reduce all rates by 20 percent, repeal the AMT, and repeal the estate tax. Santorum would cut taxes by $6 trillion over the next decade. Gingrich would cut taxes by $7 trillion. Paul, the responsible one, would only cut taxes by $5 trillion.

This is pure crazy talk. I'm not sure what is more remarkable: that the candidates would compete for the affections of the Tea Party (a supposed anti-debt group) by planning to increase the national debt; that they think that they can pose as deficit hawks while planning to increase the national debt; or that they are getting away with it.

How did this happen? It's probably no surprise to you, but over the past thirty years the Republican Party has become not the party of balanced budgets, but the party of tax cuts—thanks in no small part to Grover Norquist's Taxpayer Protection Pledge. This is a story we tell in chapter 3 of White House Burning. In power, they can strong-arm enough moderate Democrats to pass their tax cuts, but can't muster the support to actually cut spending. The only surprising thing is how long they've been able to wave the flag of fiscal responsibility.

Not that I'm a fan of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. The CRFB is another of those "centrist" groups or panels (like Bowles-Simpson, like Domenici-Rivlin, like the Gang of Six) that is using deficits as an excuse to cut taxes under the guise of "tax reform." Tax reform, for these groups, means eliminating loopholes and lowering tax rates even below George W. Bush levels. By setting the baseline so low (assuming the Bush tax cuts are made permanent), they can claim that their tax reform packages will increase revenues and reduce deficits. In fact, compared to current law, they all support large tax cuts, mainly for the rich.

I can understand why you might want tax reform. I can also understand why you might want lower tax rates for the rich. (You might be rich, for one.) I don't understand how you can use the national debt as an excuse for tax cuts. If you care about the national debt, you should want to let the Bush tax cuts expire and then close loopholes without lowering rates.

February 23, 2012

Why Won't The Federal Reserve Board Talk To Financial Reform Advocates?

By Simon Johnson

The Federal Reserve has great power in modern American society, including the ability to move the economy and, at least indirectly, to create or destroy fortunes. Its powers operate in two ways: through control over monetary policy, meaning interest rates and credit conditions more broadly, and through its influence over how the financial system is regulated generally and how specific large banks are treated.

The secrecy of our central bank has long been a source of controversy. In line with changes at central banks in other countries over recent decades, the Fed's chairman, Ben Bernanke, has pushed for more transparency regarding how individual members of the Federal Open Market Committee view the economy – and thus how they are thinking about the future course of interest rates (and the Fed keeps us posted). This is a commendable change, helping people throughout the economy understand what the Fed is trying to do and why.

Under pressure from both left and right – for example, in the unlikely alliance of Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont and Representative Ron Paul of Texas – the Fed has also, after the fact, disclosed more of its actions during the recent financial crisis.

But in terms of its process for determining financial-sector regulation, the Federal Reserve – at least at the level of the Board of Governors in Washington – is moving in the wrong direction.

Fed officials do testify frequently before Congress – 11 times last year on regulatory and supervisory matters, by the Fed's count. But the Fed's decision-making process is nowhere near as open and transparent as that of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (about which I wrote recently).

The Wall Street Journal reported on Tuesday that during the 1980s that the Fed's board held 20 to 30 public meetings a year, but these dwindled during the Greenspan years to less than five a year in the 2000s and "only two public meetings since July 2010." At the same time, "the Fed has taken on a much larger regulatory role than at any time in history" – including "47 separate votes on financial regulations" since July 2010, The Journal said.

This high level of secrecy is a concern. It is particularly alarming when combined with the disproportionate access afforded to industry participants in the arguments about what constitutes sensible financial reform.

For example, just on the Volcker Rule – the provision in Dodd-Frank to limit proprietary trading and other high-risk activities by megabanks – Fed board members and staff members apparently met with JPMorgan Chase 16 times, Bank of America 10 times, Goldman Sachs 9 times, Barclays 9 times and Morgan Stanley 9 times (as depicted in a chart that accompanies The Wall Street Journal article).

How many meetings does a single company need on one specific issue? How many would you get?

Americans for Financial Reform, an organization that describes itself as "fighting for a banking and financial system based on accountability, fairness and security," met with senior Federal Reserve officials only three times on the Volcker Rule. (Disclosure: I have appeared at public events organized by Americans for Financial Reform, but they have never paid me any money. I agree with many of its policy positions, but I have not been involved in any of their meetings with regulators.)

Americans for Financial Reform works hard for its cause, and it produced a strong letter on the Volcker Rule – as did others, including Better Markets and Anat Admati's group based at Stanford University.

Based on what is in the public domain on the Fed's Web site, my assessment is that people opposed to sensible financial reform – including but not limited to the Volcker Rule – have had much more access to top Federal Reserve officials than people who support such reforms. More generally, it looks to me as though that even by the most generous (to the Fed) account, meetings with opponents of reform outnumber meetings with supporters of reform about 10 to 1.

According to those records, for example, the Admati group has not yet managed to obtain a single meeting with top Fed officials on any issue, despite the fact that they are top experts whose input is welcomed at other leading central banks. To my definite knowledge, they have tried hard to engage with people throughout the Federal Reserve System; senior people at some regional Feds are receptive, but the board has not been – either at the governor or staff level.

When I asked the Fed Board of Governors about this lack of engagement with the most prominent research team advocating higher capital requirements, a representative sent this response, "We are meeting with a variety of groups and individuals with diverse perspectives and are carefully considering both what we hear in the meetings and what we read in the tens of thousands of comment letters we are receiving as we work with other regulators to implement the Dodd-Frank Act."

Honestly, I do not understand the Fed's attitude and policies – if they are really serious about pushing for financial reform. No doubt they are all busy people, but how is it possible they have time to meet with JP Morgan Chase 16 times (just on the Volcker Rule) and no time to meet Anat Admati – not even for a single substantive exchange of views?

The Federal Reserve should open up – creating an advisory council along the lines of what the FDIC already established for systemic resolution issues. Most importantly, this advisory council should include strong outsider experts – such as Professor Admati and her associates – and the council should meet in public, with its proceedings webcast (again, as the FDIC does). Anything less than this degree of openness and engagement will continue to help powerful special interests and end up further undermining the Fed's legitimacy.

An edited version of this post appeared this morning on NYT.com's Economix blog; it is used here with permission. If you would like to reproduce the entire post, please contact The New York Times.

February 21, 2012

What Is This White House Burning?

By James Kwak

Loyal blog readers have surely noticed the new left-hand sidebar of the blog and may be wondering what this "White House Burning" thing is about. I wanted to give you a bit more background than the jacket flap copy you can read elsewhere.

You don't have to know a lot of American history to know that the War of 1812 began two hundred years ago. Yet I doubt there will be much celebration, since it's not a war we're particularly proud of, like World War II, nor is it one that is particularly controversial, like Vietnam. Its most famous moment is perhaps the burning of Washington in August 1814, although it also gave us the phrase "We have met the enemy and they are ours" (Commander Perry, Battle of Lake Erie), the words to the national anthem, and the political career of Andrew Jackson, victor at the Battle of New Orleans.

Somewhat less well known is that the United States fought the war in an almost continual state of fiscal crisis, barely able to borrow enough money to mobilize and equip an army and navy that had been starved of resources over the previous decade. That crisis was perhaps not as deep as the fiscal crisis of the Revolutionary War and its aftermath, but there at least we had an excuse: it's hard to muster the resources to fight an anti-colonial war when your country doesn't exist yet. The War of 1812, by contrast, was a war of choice, and the government's fiscal problems were largely self-induced.

The same goes for the fiscal problems the federal government faces today. Our economy generates plenty of resources, yet our political system seems unable to make any coherent choices about how to allocate (or not allocate) those resources. Our main goals in White House Burning were to explain our fiscal and political situation and show one path forward for our country.

The first part of the book describes the political struggles that have always surrounded deficits and the national debt, from 1789 through the Gingrich Revolution and the debt ceiling showdown. The second part explains what the federal government does, where the debt comes from, and why it matters (and also why it doesn't matter). The third part argues for a certain role of government in society and recommends a set of policy changes that could reduce the future national debt while increasing economic efficiency and maintaining the most important functions of the federal government. I'm sure there is something in there for everyone to disagree with, no matter where you are on the political spectrum.

In many respects, I fall into the "unemployment first, deficit later" crowd. But in politics, you can't always choose what battles to fight when. And like it or not, for good reason or bad, deficits are a major political issue this year. This is our attempt to explain how we got here and what is at stake in these debates.

February 18, 2012

Facebook's Targeted Advertising

By James Kwak

This is the best Facebook can do with the information it has about me?

Admittedly, I don't use Facebook that much—but in that respect I'm probably like the vast majority of Facebook users.

February 17, 2012

Health-Care Costs and Climate Change

By James Kwak

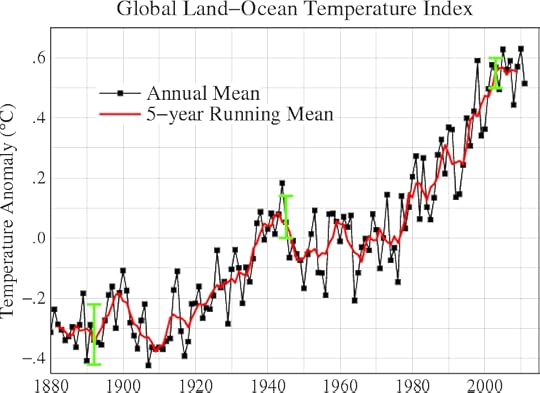

That's the average global temperature from 1998 through 2008, according to NASA. This, of course, is what enabled George Will to write, in 2009, "according to the U.N. World Meteorological Organization, there has been no recorded global warming for more than a decade."

Of course, George Will is just a run-of-the-mill climate change denier with a gift for mis-using statistics. In this case, he was probably citing a World Meteorological Organization study that said, "The long-term upward trend of global warming, mostly driven by greenhouse gas emissions, is continuing. . . . The decade from 1998 to 2007 has been the warmest on record." And here's the long-term picture, also from NASA:

You all know this, so why am I bringing it up?

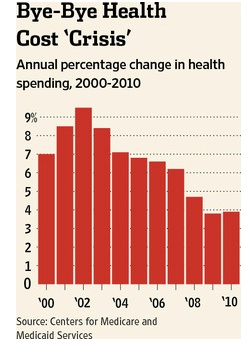

Well, look at this, from J. D. Kleinke of AEI in The Wall Street Journal:

Those are annual percentage changes in nominal terms, so his point is that annual increases are going down. But what does the long term look like?

That's health care spending as a share of the economy, so we don't have to worry about correcting for inflation (as we do with Kleinke's graph). Do you think the trend is up or down?

There is some difference between rising temperatures and rising health care spending. Temperatures are rising because there is too much greenhouse gas in the atmosphere, and that is something we are not going to be able to change in the short run. Health care costs are somewhat more responsive to changes in behavior by companies and households, so it is possible that health care inflation could be slowing down.

But health care costs are also a lot like climate change. We have ever-improving medical technology, and we have a health care system where the usual incentives to contain costs are weak and the incentives to run up costs are strong. In that environment, even if there are short-term changes that keep costs from growing quickly for a few years, as occurred with managed care in the 1990s, the long-term trend is still up—and we should be cautious about declaring victory as long as the structural problems have not gone away.

So people from AEI cherry-pick statistics to make their political points. So what?

I only heard about Kleinke's article because it was cited by Jeff Sachs (hat tip Mark Thoma) in order to combat what he calls "entitlements hysteria." In Sachs's view, doomsday projections of health care costs are being used to fuel deficit hysteria and demands to cut government spending, especially on health care.

That is certainly true. But the fact that conservatives use those projections to argue for their policy goals (like turning Social Security into a 401(k) plan and Medicare into a voucher program) doesn't mean those projections are systematically biased. It's true that the long-term projections are likely to be wrong in one direction or the other, but we don't know which one. Health care spending could grow faster than the CBO projects (CBO models already incorporate a long-term slowdown in the rate of growth of health care spending), in which case the fiscal crisis of the 2030s would hit in the 2020s.

To my mind, if the central projection shows very bad things a long time from now, but there is a wide cone of uncertainty around the central projection, that is all the more reason to take action now to prevent the bad things from happening. That's my opinion about climate change. Sure, temperatures might not rise as fast as we currently expect, and Nathan Myhrvold might invent a magical cure for global warming in the meantime. But things could also go much worse than the current models indicate, and we need to be prepared for that scenario—not just discounting it to nothing because of the uncertainty.

Most liberals (people like me) take this view about climate change, but they take the opposite view of government deficits and the national debt: they think we should not be worried about the debt today because the projections could turn out to be wrong. Many conservatives take exactly opposed positions: they worry about the national debt (because the projections look bad) but not about climate change (because the projections have a big cone of uncertainty).

I worry about climate change and about health care costs and the long-term national debt. Sure, health care inflation could slow down, but it could also speed up. I differ from the folks at AEI in that I think we should preserve Social Security and Medicare and we can pay for them through a lot of tax changes that will be good for the economy on balance (higher capital gains taxes, carbon tax, elimination of tax expenditures, etc.). I also think that major policy changes should be deferred until the economy is stronger, if possible. But the bottom line is that the uncertainty is reason for action, not inaction.

February 16, 2012

Denial or Principle?

By James Kwak

I wanted to make a belated return to Binyamin Appelbaum and Robert Gebeloff's article on reluctant safety net beneficiaries. Earlier this week I argued that their framing of an expanding safety net that has spread from the poor to the middle class is wrong, but otherwise the themes they discuss are very important.

Many liberals like to point out the apparent hypocrisy of the people featured in the article, who rail against big government, demand lower spending, and simultaneously rake in benefits from the federal government that they hate. The central figure in the article, Ki Gulbranson, works hard yet has barely enough money to support his family, even with the earned income tax credit* and reduced-price school lunches for his kids. His conclusion: the country is going bankrupt, but people don't make enough money to pay more taxes, so we should have smaller government. He would rather go without his current benefits—but he can't imagine retiring without Medicare and Social Security.

I don't think Gulbranson is a hypocrite at all. I don't think taking a benefit you don't think should exist makes you a hypocrite, just like I don't think Warren Buffett should voluntarily pay higher taxes. I think his position is one part magical thinking and one part principle.

The magical thinking is thinking that there is a difference between asking people to pay $100 more in taxes and asking them to take $100 less in benefits. It's thinking that you can meaningfully reduce total government spending without undermining the very programs you will need to survive in retirement. As another interviewee said, without Medicare, his wife would go blind and he would die. (For a discussion of magical thinking in its pure form, see Greg Sargent's column.)

But there may be a principle in there, too. The principle is that you should be self-reliant and not rely on your "grandchildren" to support you**—and if you don't earn enough money, then you should make do with less. And some of the people saying this, like Gulbranson, fall squarely in the "don't earn enough money" category. As Appelbaum and Gebeloff say (they can't get any of their subjects to say it clearly),

"They say they want to reduce the role of government in their own lives. They are frustrated that they need help, feel guilty for taking it and resent the government for providing it. They say they want less help for themselves; less help in caring for relatives; less assistance when they reach old age."

That may be unrealistic and foolhardy. It may also be irresponsible, especially if you're supporting your children or your elderly parents. But it's also a stand on some kind of principle; it certainly isn't in their self-interest. And it's music to the ears of Herman Cain, Mitt Romney, Newt Gingrich, the Koch brothers, and all the other super-rich ideologues who want lower taxes.

Why? I think it's another example of the fact that people's self-identity is more deeply rooted than their material self-interest or, for that matter, their understanding of the world. If you see yourself as a tough, self-reliant yeoman farmer who can handle anything the world can throw at you, it's easier to tell yourself you'll be able to deal with hardship than to admit that maybe you can't. If you think the world is divided between hard-working people who support their families and freeloaders who live off of other people's taxes, it's easier to see yourself forgoing government benefits than to see yourself as a freeloader.

This is one reason why so many "middle class" people are out there fighting to protect Herman Cain from big government.

* As I said in my earlier post, I don't consider the EITC program a safety net program. I consider it a makeshift fix to the tax code to correct for the insanely high marginal rates people would other wise pay as they enter the workforce and for regressive payroll taxes.

** Government borrowing to finance current consumption is only to a small degree a transfer from future generations to ours (if we lived in a closed economy, there would be no transfer at all), but the image of burdening our grandchildren with debt seems to be deeply ingrained at this point.

Under Construction Thursday Night

With WordPress.com, you can't modify your blog in a sandbox and then promote it to production. Things will be unsettled for a couple of hours.

Update: OK, I think I'm done for now. I'm pretty confident the page nav problem is fixed (thanks to a custom menu). I killed the image at the top of the page to save on white space. We may not need the third column, but we will next week. The Twitter feed filters out all tweets that are just robotic notifications of new blog posts, so it is 100% non-redundant with the rest of the blog.

If the fonts are too small (most common problem, I think), read this (bottom section).

Blog Housekeeping

By James Kwak

As you may have noticed, we've been making some changes to the site recently. The main thing is that I decided we needed two sidebars in order to make it into the 21st century. I've been looking for a good theme that has three columns but doesn't have dynamic page navigation (those links across the top), because we have pages that shouldn't really be made so prominent, but I couldn't find one. So I switched to this theme, which has three columns but also has dynamic page navigation. Now the problem is that the page navigation is buggy: right now it's showing pages that no longer exist, pages whose titles have changed, etc., and it seems to change mysteriously from time to time. I'm hoping it will settle down in the next few days. I've generally been very happing with wordpress.com, but this is totally infuriating.

February 13, 2012

What Expanded Safety Net?

By James Kwak

In general, I think Binyamin Appelbaum and Robert Gebeloff's article on how the same people oppose government handouts and take government handouts is very good. But I think their framing buys into a piece of conventional wisdom that just isn't true.

Here it is, without any shortening (but emphasis is mine):

"The problem by now is familiar to most. Politicians have expanded the safety net without a commensurate increase in revenues, a primary reason for the government's annual deficits and mushrooming debt. In 2000, federal and state governments spent about 37 cents on the safety net from every dollar they collected in revenue, according to a New York Times analysis. A decade later, after one Medicare expansion, two recessions and three rounds of tax cuts, spending on the safety net consumed nearly 66 cents of every dollar of revenue.

"The recent recession increased dependence on government, and stronger economic growth would reduce demand for programs like unemployment benefits. But the long-term trend is clear. Over the next 25 years, as the population ages and medical costs climb, the budget office projects that benefits programs will grow faster than any other part of government, driving the federal debt to dangerous heights."

The idea that politicians have expanded the safety net is just not true, with the exception of the Medicare prescription drug benefit and an expansion in Medicaid that hasn't taken effect yet. Spending on social programs has increased for a few obvious reasons: the baby boomers have started taking Social Security benefits, increasing that program's expenditures; the recession boosted unemployment benefits, disability claims, and eligibility for poverty programs; and most importantly, health care has gotten much more expensive.

But those programs themselves haven't gotten more generous (except, again, for Medicare Part C), nor have they expanded to cover more people. Instead, as Mike Konczal shows in detail, the federal government took an axe to the safety net back in the 1990s (remember welfare reform?). Remaining programs such as TANF have declined in real value. What has happened is not that the safety net has gotten more robust, but that the same real benefits have gotten more expensive because of demographic shifts and excess health care cost growth.

In short, the middle class is getting a larger proportion of "safety net" payments not because that net is expanding from the poor to the middle class, but for two other reasons: one is that we've cut the programs for the poor; the other is that health care is getting more expensive.

As Appelbaum and Gebeloff say, safety net programs (if you count Social Security and Medicare as part of the safety net, as they do) will cost more and more over the next twenty-five years. But again, that's not because those programs are becoming more generous. It's because more people will be using them and health care will become more expensive.

The earned income tax credit was expanded in the 2001 tax cut. But I wouldn't call that part of the "safety net." The point of the EITC is to encourage people to work. As your income moves from zero to a low level—say, up to $30,000 for a family—you lose important benefits, most notably Medicaid; you also have to pay a flat 15.3 percent of your income in payroll taxes (counting both the employee and employer shares). Together, this means that your marginal tax rate could be extremely high (because of those lost benefits). The EITC is designed to reduce that marginal tax rate to create the incentive to work instead of relying on benefit programs. It's not part of the safety net; it's a provision of the tax code designed to reduce the distorting influence of the safety net.

Reports of Wall Street's Death

By James Kwak

Gabriel Sherman wrote what I would call a hopeful article last week called "The End of Wall Street As They Knew It." The basic premise is that the end of the credit bubble and the advent of Dodd-Frank mean lower profits, more boring businesses, and smaller bonuses on Wall Street—permanently (or at least for the foreseeable future). Sherman also says that the former masters of the universe are now engaged in "soul-searching": "many acknowledge that the bubble-bust-bubble seesaw of the past decades isn't the natural order of capitalism—and that the compensation arrangements just may have been a bit out of whack."

Call me a skeptic, but I'm not convinced. For one thing, there are few people quoted in the article who actually seem to be engaged in anything that might be called soul-searching (as opposed to complaining—like the now-clichéd banker who watches his spending carefully but has a girlfriend who likes to eat out). The story's featured voices are ones that are not on Wall Street and have been critical of it for a long time, such as Paul Volcker and John Bogle. Another example of "self-criticism" comes from Bill Gross—but's he's on the buy side, not Wall Street.

There are certainly bankers saying that the business is getting tougher, but that's a cyclical thing. Profits were lower in 2011 than in 2010 because the economy was weaker in 2011 than in 2010. Jamie Dimon also gets a lot of words in, saying that banking is becoming a more boring business that he actually likens to Wal-Mart or Costco. But Jamie Dimon is essentially a politician, the elder statesman of the banking industry, so while I like what he says, I wouldn't take it at face value.

My main worry is that the regulations we have are still fundamentally reactive, the people on Wall Street are extremely smart, they have access to a lot of money, and they will come up with new businesses that will make lots of money and create new risks for the financial system and the economy.

Simon Johnson's Blog

- Simon Johnson's profile

- 78 followers