Simon Johnson's Blog, page 47

December 22, 2011

No One Is Above The Law

By Simon Johnson

The American ideal of "equal and impartial justice under law" has repeatedly been undermined by attempts to concentrate power. Our political system has many advantages, but it also provides motive and opportunity for resourceful people to become so strong they can elude the legal constraints that bind others. The most obvious example is the oil and railroad trusts at the end of the nineteenth century. A version of the same process is happening again today but what has become concentrated is not a vital energy source or the nation's transport arteries but rather something much more abstract: financial sector risk.

In early 2009, Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner reportedly said to President Obama and senior members of the new administration, with regard to the financial system:

"The confidence in the system is so fragile still. The trust is gone. One poor earnings report, a disclosure of a fraud, or a loss of faith in the dealings between one large bank and another—a withdrawal of funds or refusal to clear trades—and it could result in a run, just like Lehman." (from Ron Suskind's Confidence Men, p.202)

Now three years later, the megabanks are even bigger, as is the risk they concentrate (see my recent testimony to the Financial Institutions subcommittee of the Senate Banking Committee for details.) Curiously, their precariousness, as much as their power, is shielding these behemoths from the enforcement of financial fraud laws.

Thankfully, this lawlessness – and it is that – nettles some regulators and prosecutors. New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman is mobilizing the resources for a long-overdue investigation of Wall Street practices and hopefully gathering momentum. But the Obama administration continues to dither – arguing behind the scenes that the financial system is still too weak. This inertia – a government at rest tends to stay at rest – has led to public protest and deeply shaken trust in the financial system.

In an important article in the Huffington Post this week, Jeff Connaughton (former chief of staff to Senator Ted Kaufman) argues that the Department of Justice failed to concentrate the resources that might have built successful cases:

"As the New York Times and New Yorker have reported, the Department's leadership never organized or supported strike-force teams of bank regulators, F.B.I. agents, and federal prosecutors for each of the potential primary defendants and ignored past lessons about how to crack financial fraud."

We may never know exactly why the administration failed to organize effectively along these lines, but Mr. Geithner's influence likely played a role. For his part, President Obama, the few times he's been asked, explains that past unethical Wall Street actions are "not illegal."

Mr. Geithner may dispute details in Confidence Men (which was also quoted by Mr. Connaughton in his piece), but worry about system stability is part of the treasury secretary's job. Despite a lack of any supporting evidence, Mr. Geithner sees megabanks as essential to the functioning of the economy – and gambled on bailing them out as a way to restart the economy. So it would have been entirely logical for him to fear disclosures that would damage their business models and legal viability.

Whenever someone or a group of people is above the law, equality before the law is ended. And this is exactly why the megabanks threaten to undermine democracy.

For your holiday reading, pick an example of power and accomplishment gone awry in American history. I suggest the bizarre tale in the new book American Emperor: Aaron Burr's Challenge to Jefferson's America; or the classic account of the confrontation between President Andrew Jackson and the Second Bank of the United States, in The Age of Jackson by Arthur Schlesinger; or Teddy Roosevelt's confrontation with the railroad trusts in Edmund Morris's Theodore Rex. Or, if you prefer something more modern, try Richard Reeves's ultimately sad President Nixon: Alone in the White House.

The lesson of these books is throughout American history, the ultimate constraint is not so much the courtroom but rather the polling place. And here the classic American feedback mechanism appears to be damaged.

President Obama's campaigns have taken a great deal of money from Wall Street and, as Mr. Suskind's book vividly illustrates, has proved consistently reluctant to take on this powerful vested interest. This is why Mr. Geithner is still treasury secretary.

In The Rise and Decline of Nations: Economic Growth, Stagflation, and Social Rigidities, Mancur Olson identified the rise of special interests as a problem for all societies – a form of sclerosis sets in. This is a perfect idea for the political right; they can cite Friedrich Hayek's The Road to Serfdom, no less, on the idea that powerful people seize the state and its ideology to insulate themselves from competition.

Unfortunately, Mitt Romney and Newt Gingrich – the current front-runners for the Republican nomination – are also presumed to have taken or to be seeking a great deal of funding from Wall Street. (See this coverage on Obama and Romney, and on Gingrich.)

Ron Paul has expressed concern about big banks (see this link; there are no more specifics on his campaign website, e.g., here). But his only policy recommendation is not to bail them out in the future – i.e., just let them fail. Unfortunately, this philosophy fails to appreciate the true nature of the big banks' power and the damage they can cause.

Too Big To Fail banks benefit from an unfair, nontransparent, and dangerous subsidy scheme. This isn't a market. It's a government-backed distortion of historic proportions. And it should be eliminated.

Jon Huntsman, the only candidate with a credible plan to break up big banks, is currently polling 13 percent in New Hampshire (although Nate Silver sees hope).

Presidential elections matter, because the winner appoints those who protect – or claim to protect – the public interest. As Jeff Connaughton reminds us:

"Repeat financial fraudsters don't pay relatively paltry — and therefore painless — penalties because of statutory caps on such penalties. Rather, regulatory officials, appointed by Obama, negotiated these comparatively trifling fines"

We could replace these officials with people who are less sympathetic to the banks. But this sympathy comes from fear – the fear of what could happen if a big bank fails. New officials would soon share the old fears.

Our biggest banks pose a real threat; if you hold them accountable for their past actions, they will collapse. The only credible way to counter to this threat – and the only reasonable way to protect our democracy – is to break them up.

An edited version of this post appeared this morning on the NYT.com's Economix blog; it is used here with permission. If you would like to reproduce the entire post, please contact the New York Times.

December 21, 2011

More on Long-Term Care Insurance

By James Kwak

After my previous post on the topic, a friend passed along a recent paper by Jeffrey Brown and Amy Finkelstein in the Journal of Economic Perspectives. I recommend reading it if you are interested in the topic because it provides a lot of good background information and explains some of why the market is the way it is.

They make some similar points to mine. For example (p. 138):

"First, the organization and delivery of long-term care is likely to change over the decades, so it is uncertain whether the policy bought today will cover what the consumer wants out of the choices available in 40 years. Second, why start paying premiums now when there is some chance that by the time long-term care is needed in several decades, the public sector may have substantially expanded its insurance coverage? A third concern is about counterparty risk. While insurance companies are good at pooling and hence insuring idiosyncratic risk, they may be less able to hedge the aggregate risks of rising long-term care utilization or long-term care costs over decades. In turn, potential buyers of such insurance may be discouraged by the risk of future premium increases and/or insurance company insolvency."

They also show just how expensive private long-term care insurance is. By their calculations, the load on a typical policy is 32% (which means that the present value of benefits is only 68% of the present value of premium costs). This is what you would expect in a thin market with a lot of adverse selection. (And one more note: The median cost of long-term care is a lot lower than in Massachusetts, the state I cited in my previous post. See this study to see where your state ranks.)

A lot of the paper is about Medicaid, which (along with other public insurance, such as Medicare's limited benefits) currently covers a staggering 60 percent of total expenditures, with private insurance paying for only 4 percent (p. 122). Brown and Finkelstein argue that the availability of Medicaid is a major reason why the private market is so anemic. Essentially, if you have a modest income and a small amount of assets, most of the benefits you would receive from a private policy simply replace benefits you would have gotten from Medicaid anyway, so the policy isn't worth much to you.

I think they are right, but I don't think the implication is that we have to reform Medicaid to encourage the private market.* I think that the other problems with long-term care insurance, which they also discuss (the passage quoted above as well as behavioral issues), mean that a private solution is likely to fail even in the absence of Medicaid. As they point out, only one-quarter of people in the top wealth quintile have long-term care insurance, and, for them, the availability of Medicaid is unlikely to affect their choices.

The other problem is that a private solution is going to create a lot of uninsured, just as it does with health insurance, and without the Medicaid backstop, that means millions of elderly people who need long-term care but can't get it. Are we really willing as a society to deny those people the care they need because they weren't farsighted or rich enough to buy insurance when they were younger?

Hubert Humphrey once said, "The moral test of government is how it treats those who are in the dawn of life, the children; those who are in the twilight of life, the aged; and those in the shadows of life, the sick, the needy and the handicapped."** The point of Medicaid long-term care insurance is that if you need long-term care, but you have nothing, the rest of society (via taxes) will pay for it. Sure it's inefficient. But is the alternative really better?

* To be fair, they don't say that we should reform Medicaid, either. Instead, they say that it would be necessary to reform Medicaid in order to increase private market coverage. For example (p. 137):

"Substantial growth of the private market is signifificantly hampered by two features of Medicaid—means-testing and its secondary payer status—which combine to impose a large implicit tax on private insurance and to crowd out the purchase of private insurance for most of the wealth distribution. . . . The evidence today suggests that Medicaid reform is a necessary condition for substantial growth in the private long-term care insurance market, but it does not at all imply that such reform would be sufficient."

** Cited by Don Berwick in his great speech on health care in the United States today.

December 20, 2011

Can We Afford Medicare?

By James Kwak

The conventional wisdom, repeated endlessly by the so-called serious people, is that we can't afford traditional Medicare and hence it has to be radically overhauled (see Ryan-Wyden for the latest round). But I've never seen a convincing argument for why we can't afford traditional Medicare. Yes, costs are rising as a share of GDP. But in principle, to make the case that we have to reform the program, you would have to argue that revenues can't rise enough to keep pace—which in most cases, just shows that you don't want revenues to rise enough.

More specifically, you have to know how big the Medicare deficit is and how fast it is rising. By my calculations, relying mainly on the 2011 Medicare Trustee's report, the deficit was 1.7% of GDP in 2010 and will be 3.0% of GDP in 2040. So the argument that we can't afford traditional Medicare relies on the proposition that this 1.3% of GDP is the straw that will break America's fiscal back. Needless to say, this is nonsense, especially since other tax revenues not related to Medicare will be rising over the same time period, at least under current law. For all the details and sources, see my latest Atlantic column.

Medicare has its problems. But we have choices.

December 16, 2011

Money

By James Kwak

I was browsing for Christmas presents and came across a brilliant xkcd cartoon, "Money." (Click on it to zoom in.) It includes all sorts of fun bits like this (this is just a small excerpt; you can buy a poster-size version of the whole thing):

But this was actually my favorite part:

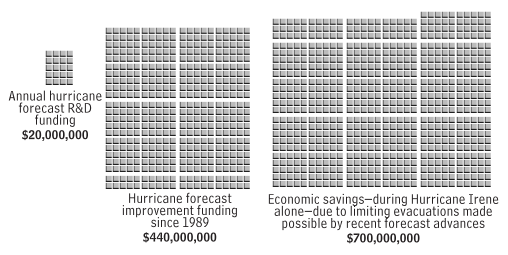

I've written elsewhere about the government's role in collecting hurricane data (including flying planes into hurricanes) and plotting their course and intensity. I think this is one of those things that we just assume the government should do—protect us from hurricanes—yet we conveniently forget about when we talk about evil big government spending.

The source for that data is a blog post by Jeff Masters, co-founder of the Weather Underground (and a former Hurricane Hunters pilot). In short, because of improvements in the way the National Hurricane Center forecasts hurricane paths, the NHC can issue much tighter forecasts than twenty years ago. In the case of Hurricane Irene (the one that hit the East Coast in late August), that meant that seven hundred miles of coastline in the Southeast (Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina) did not get official hurricane warnings; twenty years earlier, because the models weren't as good, they would have gotten warnings. Masters cites an estimate that over-warning costs $1 million per mile of coastline, for a total savings of $700 million from one storm.

The $1 million per mile estimate is hard to pin down. The paper Masters cites is John C. Whitehead, "One Million Dollars Per Mile? The Opportunity Costs of Hurricane Evacuation," Ocean & Coastal Management 46 (2003): 1069–83. But although Whitehead calls the $1 million per mile estimate "over-quoted," he actually argues that it is too high.* Still, he estimates that a mandatory evacuation order for a category 3 hurricane (which I believe Irene was when it hit North Carolina) would generate $32 million in evacuation costs, in 1998 dollars, and a voluntary evacuation would cost $6 million (Table 9, p. 1080). Given the greater length of the Florida coastline, its much higher population density (see map below, which I grabbed from here), population growth since 2003, and inflation since 1998, it's highly likely that the cost savings from avoiding over-warning run well into the tens if not hundreds of millions of dollars, even assuming just a voluntary evacuation. Whitehead's estimate also excludes lost wages and presumably lost economic output (p. 1079); this is reasonable for his estimate of evacuation costs, but those costs should be included if you're estimating the total costs of over-warning, not just the cost of evacuation. Including those potential costs makes the total cost savings even higher.

So when you pay your taxes, that's one of the things you're getting.

(I guess some libertarian will argue that this is an unjustified subsidy to people who live along hurricane-prone coasts. To which I would say that people value living on those coasts, and the incremental value they derive from living in Miami as opposed to, say, Oklahoma City, is probably far higher than the $20 million per year spent on hurricane forecasting research. This is different from the subsidy for federal flood insurance because, in that case, you could simply extract part of that incremental value by pricing the insurance appropriately; since hurricane forecasting ability is a public good, it would be harder to force people living on the coast to pay for it.)

* As an aside, I'm not sure that the $1 million per mile is "over-quoted" to begin with. Whitehead's source is a personal communication. When you Google "'one million dollars per mile' hurricane," mainly you get a lot of references to Whitehead's paper. But it could just be that Whitehead's paper swamped previous references to the rule-of-thumb estimate (which would indicate that it wasn't that widespread an estimate to begin with).

Where Is The Volcker Rule?

By Simon Johnson

Three years ago, a financial crisis threatened to bring down the United States economy – and to spread economic disaster around the world. How far have we come in preventing any kind of recurrence? And will the much-discussed Volcker Rule – attempting to limit the risks that big banks can take – play a positive role as we move forward?

Bad loans were the primary cause of the 2007-8 financial debacle. When the full extent of the problems with those loans became apparent, there was a sharp fall in the values of all securities that had been constructed based on the underlying mortgages – and a collapse in the value of related bets that had been made using derivatives.

The damage to the economy became huge because these losses were not dispersed throughout the economy or around the world. Rather, many of the so-called "toxic assets" were held by the country's largest banks. Financial institutions that used to lend to consumers and businesses had instead become drawn into various forms of gambling on the booming mortgage market (as well as on commodities, equities and all kinds of derivatives). "Wall Street gets the upside, and society gets the downside" was the operating principle.

And what a downside that proved to be. Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson said the Troubled Asset Relief Program, or TARP, was needed to buy those toxic assets from the banks. But this quickly proved unwieldy, so TARP pumped roughly half a trillion dollars into bank equity. The Federal Reserve backed this up with a massive amount of "liquidity" through more than 21,000 transactions.

The additional government debt as a direct result of this finance-induced deep recession is estimated by the Congressional Budget Office at around 50 percent of gross domestic product, roughly $7 trillion.

These are staggering numbers. And this system of big banks taking outsized risks, failing and imposing huge damage on the rest of us has to stop. This ball is now firmly in the regulators' court.

Whatever your broader issues with the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010, one point about legislative intent in this legislation is clear: the regulators have the authority to cut banks down to size and return them to their historical role of intermediating between savers and borrowers.

As for size, the regulators have long ignored the existing guidelines and allowed the biggest banks to get bigger. We need to go in the opposite direction, and that includes cutting the private mega-banks, as well as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, down to size. It also means taking advantage of the resolution authority and all associated provisions that Sheila Bair, the former chairman of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, worked so hard to put into the Dodd-Frank Act.

As Jon Huntsman is arguing on the Republican campaign trail, too-big-to-fail banks simply need to be forced to break themselves up.

But we also need to make the mega-banks less likely to fail. The easiest way to do that would be to require banks to have enough common equity to absorb losses.

But the bankers have pushed back hard, with Jamie Dimon, head of JPMorgan Chase, leading the way with statements such as this on capital requirements, which are known loosely as the Basel Accords: "I'm very close to thinking the United States shouldn't be in Basel any more. I would not have agreed to rules that are blatantly anti-American."

Dan Tarullo, responsible for this issue on the Federal Reserve Board, seems to support the idea of requiring significantly more equity in big banks, perhaps moving in the direction recommended by Anat Admati and her colleagues. But Mr. Tarullo appears to have lost that battle for now.

If we are not breaking up banks and if we are not requiring them to have reasonable levels of capital (thus limiting how much they can borrow relative to their equity), we must use all other available tools to stop the too-big-to-fail banks from taking excessive and ill-conceived risks.

This is where the Volcker Rule becomes so important. Named for Paul A. Volcker, former chairman of the Federal Reserve, and adopted as part of Dodd-Frank at the insistence of Senators Jeff Merkley, Democrat of Oregon, and Carl Levin, Democrat of Michigan, the Volcker Rule directs the regulators to get banks out of the business of betting on the markets.

The regulators are now determining how they plan to implement it. Draft proposals are currently open for comment.

But the latest news on this front is not encouraging, as key regulators seem stuck in a "bigger is better, and anything goes for the biggest" mindset.

The Volcker Rule has some good points, including a requirement that trader compensation not be tied to speculative risk-taking, and that firms collect and report some essential data to regulators. But the current draft does too little to actually stop the banks' current risky practices.

The main problem is that the rule as drawn does not set out the clear, bright lines that banks and regulators need, nor does it provide for meaningful enforcement. Instead of drawing the lines, the proposed rule mandates that firms write many of the rules themselves.

There is some good news. At this point, it is only a proposed rule, and it is open for comment (submit a comment here). Organizations like Better Markets that promote the public interest within the regulatory process will be in there fighting to strengthen the proposed rule and make the final rule better.

Everyone who cares about real financial reform should do the same, but the regulators' draft rule has made it harder to uphold the public interest than should have been the case. For example, the regulators ignored the breadth of the Volcker statute and focused instead only a narrow slice of the bank's balance sheet – just what the bank says is for "trading" purposes. Much else of what big banks do seems likely to escape scrutiny.

The regulators also have given very little guidance on conflicts of interest, on what should be considered high-risk assets or on what high-risk trading strategies should be permitted.

During a Senate hearing at which I testified last week, Senator Bob Corker, Republican of Tennessee, focused on another important problem – the lack of any restrictions on trading in the enormous Treasury securities market. The regulators will create a lot more paperwork for the banks, but if the current draft is adopted, the too-big-to-fail banks are not likely to be forced to stop doing much.

Last year Senator Levin said:

"We hope that our regulators have learned with Congress that tearing down regulatory walls without erecting new ones undermines our financial stability and threatens our economic growth. We have legislated to the best of our ability. It is now up to our regulators to fully and faithfully implement these strong provisions."

From what we've seen so far, our regulators have not yet understood this message. They seem instead more in tune with Mr. Dimon, who insisted earlier this year that regulators should back away from any effective implementation of the Volcker Rule:

"The United States has the best, deepest, widest, most transparent capital markets in the world which give you, the investor, the ability to buy and sell large amounts at very cheap prices. I wish Paul Volcker understood that."

Mr. Dimon — who is on the board of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York — seems to have forgotten the financial crisis, its impact on ordinary Americans and the utter fiscal disaster that ensued. Or perhaps he never noticed.

Mr. Dimon seems to have forgotten the financial crisis, its impact on ordinary Americans and the utter fiscal disaster that ensued. Or perhaps he never noticed.

An edited version of this post appeared yesterday on the NYT.com's Economix blog; it is used here with permission. If you would like to reproduce the entire column, please contact the New York Times.

December 14, 2011

What Good Is the SEC?

By James Kwak

This week's Atlantic column is my somewhat belated response to Judge Jed Rakoff's latest SEC takedown, this time rejecting a proposed settlement with Citigroup over a CDO-squared that the bank's structuring desk created solely so that its trading desk could short it. I think Rakoff has identified the heart of the issue (the SEC's settlements are unlikely to change bank behavior, so what's the point?) but he's really pointing to a problem that someone else is going to have to fix: we need either a stronger SEC or stronger laws. I'd like to see an aggressive, powerful SEC that can deter banks from breaking the law, but we don't have one now.

December 9, 2011

The Private Insurance Market

By James Kwak

I'm currently in the process of buying long-term care insurance—you know, so my daughter won't have to take care of me when I'm old. I have a good agent who knows all about the market and has answered every question I've had. I understand personal finance, opportunity costs, discount rates, and inflation. I know my way around a spreadsheet (one benefit of my years at McKinsey). But I find it's still hard to figure out what to do.

A bit of background: Long-term care insurance pays for your stay in a nursing home if you become unable to take care of yourself. Depending on the policy, it may also pay for care you receive at home instead of going into a facility. According to the insurer I'm considering, the median annual cost of a semi-private room in a nursing home in my state is $145,000, and the average stay is something like three years. To put that in perspective, in 2009, the median net worth of families where the head of household was of age 65–74 was $205,000 (including real estate assets).

Long term care is not covered by Medicare, except for a short period after each acute event. It is covered by Medicaid, but to be eligible for coverage you have to exhaust all of your assets. Despite that onerous requirement, Medicaid currently covers 40 percent of all spending on long-term care. (2011 Long-Term Budget Outlook, p. 39.) The Affordable Care Act of 2010 included what is known as the CLASS Act, which would have allowed anyone to buy long-term care insurance, with an average benefit of $75 per day, for a monthly premium of $123. The CLASS Act, however, has been suspended because the administration could not certify that it would be deficit-neutral over the long term. So the bottom line is: until you use up all your money, you're on your own.

Still, shouldn't you be able to buy protection in the private insurance market? The short answer is: not really.

The first problem is that private long-term care insurance is designed to help you pay for long-term care, but not to insure you against open-ended costs. Most policies have limits on both your maximum daily benefit and your lifetime total benefit, so a typical policy will only cover you for, say, three or five years. Unlimited duration policies do exist, but they are priced to deter people from buying them—because insurance companies don't want that risk on their books. So an insurance policy will help you pay for long-term care, but won't take away the tail risk—unless you're rich enough that you can cover the tail risk yourself.

The second problem is that there's no way to protect yourself against inflation. The "inflation protection" in the policies I looked at is a simple annual increase in your daily benefit by 3 percent or 5 percent. It isn't indexed to actual inflation, let alone to actual inflation in the cost of long-term care, which is what you care about. This is important because, if you're in your forties, you're buying a policy you will probably need in about thirty years. Again, the insurance companies don't want that risk, so you get to keep it. So if you buy the maximum, 5-percent protection clause, there is a decent chance that your benefit will keep up with actual costs, but there's no assurance that it will.

The third problem is that you can't protect yourself against your premiums going up in the future. The standard way to pay for long-term care insurance is to pay an annual premium that stays flat in nominal terms for the rest of your life. This means that you're overpaying (relative to the actuarial cost of the insurance) in the early years and underpaying in the later years. But if the insurance company figures out that it has underpriced long-term care insurance in general, it can file for a rate increase and boost your premium payments down the line. And by that point, you're stuck. You can't switch insurers because the new insurer won't take into account the overpayments you made to the old insurer, so it's certain to charge you higher premiums.*

In a competitive market, doesn't that just mean that someone will enter the market with a product that includes real inflation protection and a lifetime premium guarantee? Well, it hasn't so far. But more importantly, that wouldn't be real insurance either, because of the fourth problem. With long-term care insurance, you're buying a product you probably won't need for decades, at which point the world will have changed considerably. There is a decent chance that your insurer has mispriced the risk (more people will need long-term care than they expect, or long-term care will be more expensive, or medical advances will mean that people are living longer in long-term care)—in which case it will go out of business. And then your insurer won't be around when you need it.** Insurance companies try to protect themselves by (a) not offering real inflation protection and (b) reserving the right to raise your premiums in the future; if they didn't, they'd be even more likely to fail. But that still isn't perfect protection, which means you're taking on counterparty risk.

Then there's the fifth problem, which applies to all private insurance without a governmental mandate: adverse selection.

In short, the private market doesn't provide good long-term care insurance—because it can't. The insurance you can buy is really just a way of reducing the amount you'll have to pay for long-term care; it's a financial planning tool that tightens the distribution of your expected long-term net worth. My spreadsheet says it's worth it on that basis, so I'm planning to buy it (although I'm not accounting for counterparty risk or the risk of future premium increases). But it isn't insurance against extreme outcomes.

If we want real long-term care insurance, there's only one place where we could get it: the federal government. The government can offer unlimited coverage and real inflation protection (benefits based on actual costs at the time you incur them) because it has the ability to absorb long-term financial risks. It can mandate universal coverage, eliminating adverse selection. Because it can raise premiums (or other taxes), it will not go out of business. (Those potential premium increases, however, do mean that it can't offer a lifetime premium guarantee.)

If this sounds radical, it shouldn't. We already do virtually the same thing: it's called Medicare Hospital Insurance, and it's one of the most popular programs in existence. The Hospital Insurance trust fund is facing a long-term deficit, but that's not because of its basic structure: it's because the premiums it charges (payroll taxes) haven't gone up along with health care inflation, so it's systematically undercharging for the risk it's taking on.

A federal long-term care insurance program would pool a major financial risk that most middle-class families today are facing alone. (Arguably, if you don't have any assets, you don't face any risk because of Medicaid.) This is exactly what governments are supposed to do: protect ordinary people from risks that they cannot absorb and that private markets do not provide good solutions for. It would probably also help budget deficits in the long term. The government already picks up 40 percent of all long-term care spending through Medicaid, for which it gets nothing; a real long-term care program could pay for itself through payroll taxes, reducing Medicaid spending.

Now I know the last thing that will happen today is a new social insurance program. Instead, middle class people will continue hoping they don't need long-term care, elderly people will spend all their money on long-term care and then go on Medicaid, and government spending on Medicaid will continue to climb. But that's a comment on our political environment, not on the proper role of government in society.

* You can accelerate your premium payments by paying the whole thing over ten years, which reduces this risk; but the people who can afford to do that are usually people who can self-insure for long-term care anyway.

** There are state guaranty funds that pick up policies from bankrupt insurers, but their benefits are likely to be less than what you originally paid for.

December 8, 2011

Karl Rove's Latest Attack On Elizabeth Warren

By Simon Johnson

Karl Rove's Crossroads GPS has another ad out attacking Elizabeth Warren (video here). This is beyond ludicrous – the ad attempts to blame Ms. Warren for the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) and for bank bailouts. The principle here seems to be that when the truth cannot be slanted in a way you want, just ignore the facts and go all out for disinformation.

I count at least five misrepresentations in the ad, and I suggest the following corrections:

TARP was a Republican program – proposed and implemented by President George W. Bush. At the time, Ms. Warren was busy championing people whose rights had been trampled by the financial sector through various kinds of abuses.

Ms. Warren became chair of the Congressional Oversight Panel (COP) for TARP, precisely because people in Congress – on both sides of the aisle – trusted her to provide an honest and professional check on the support provided to financial firms. She did her highest profile work during the Obama administration, bringing relentless pressure on the Treasury and other agencies who just wanted to prop up big firms without any conditions.

Ms. Warren has also been a strong supporter of all efforts to rein in Too Big To Fail banks, including by breaking them up. She has consistently been one of the strongest advocates for curtailing the abusive power of megabanks (and others who have behaved badly).

At the same time, Ms. Warren has not demonized the financial sector. On the contrary, when charged with setting up the new Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, she went out of her way to work closely with those in the financial sector who provide sensible products with reasonable conditions. Her emphasis throughout has been on transparency, fairness, and full disclosure in this sector. You are not allowed to sell dangerous toasters in the United States; her point is that you should not be allowed to sell financial products that have been proven dangerous.

The idea that Elizabeth Warren would ever side with "big banks" against the middle class is preposterous. Time and again, she has stuck up for the middle class (and anyone who uses financial services) - even when it was deeply unfashionable to do so. The big banks have opposed her relentlessly and on-the-record, both directly and through various surrogates.

Perhaps the more interesting point about Karl Rove's ad is what it tells us about his strategic thinking. His team is implicitly conceding all of Elizabeth Warren's substantive points: big banks got out of control, they did enormous damage, and they were bailed out in an unreasonable manner. But Mr. Rove's group thinks it can turn all these issues against her, just because she worked hard against the interests of the banks – particularly to introduce effective consumer protection for financial products.

Will the people of Massachusetts really fall for such blatant and complete deception?

December 7, 2011

What Government Aid?

By James Kwak

Earlier this year I wrote about a paper by Suzanne Mettler that included a survey showing that a large proportion of beneficiaries of government programs insist that they have never been beneficiaries of any "government social programs"—60 percent for the mortgage interest deduction and 44 percent for Social Security retirement benefits, for example. This provides ample evidence that "keep your government hands off my Medicare" is not a fringe opinion.

Recently, I read Mettler's book, and there's more to the story. One of her arguments is that hiding government programs in the tax code undermines the democratic system because it obscures the role that government plays in society. There were two quantitative examples I thought were particularly revealing.

Mettler distinguishes between visible federal programs, such as Pell Grants and Social Security, which are administered by government agencies and therefore are more recognizable as government programs, and submerged programs such as the mortgage interest deduction or 529 accounts. She found that the more visible programs a person uses, "the more likely he or she was to agree that government had helped in times of need." Benefiting from submerged programs, however, had no impact on people's perception that the government had helped them—even in the case of things like HOPE or Lifetime Learning tax credits, which help people pay for eduction. In fact, "the greater the number of tax breaks an individual had benefited from, the more likely he or she was to disagree that government had provided opportunities for an improved standard of living" (pp. 41–43, emphasis added). (This is after controlling for socio-economic characteristics.)

In short, the way our government currently distributes goodies makes it possible for people to think that they are paragons of individual self-reliance while still being enormous beneficiaries of other people's tax dollars. That explains a lot about politics today.

Mettler and Matt Guardino also did an experiment that is described in chapter 4 of the book. For various tax expenditures, they asked people whether they supported them or not before and after giving them some information about the policies. For the mortgage interest deduction, one group was told only what it is; the other group was told what it is and that: "The people who benefit most from this policy are those who have the highest incomes. In 2005, a large majority of the benefits went to people who lived in households that made $100,000 or more that year." (That's absolutely true: you can look at last page of the JCT report on tax expenditures.) The first group favored the deduction by 81 percent to 5 percent; the second group was evenly split, 40 percent for and 41 percent against. (Support for the Earned Income Tax Credit, however, rose when people had more information.)

So there may be some reason for hope. Give people a little more information, and they are more likely to recognize their own self-interest. That would be a big improvement over the present state of affairs.

December 5, 2011

Thoughts on Law School

By James Kwak

A number of friends have asked me what I thought about David Segal's article in the Times a couple weeks ago on law schools, so I thought I would share my thoughts here. The short answer is that I thought it was pretty silly.

I admit that law schools aren't perfect. The simple fact that many (no one really knows how many) law school graduates can't find jobs as lawyers is a problem. Now, it's not obvious that that's the fault of law schools as a group: when you pile a severe recession on top of an ongoing shift among law firms away from first-year associates and toward contract lawyers, the number of entry-level jobs is going to go down, and no matter how good a job the law schools do, that isn't going to increase the number of jobs. Furthermore, you could make exactly the same criticism about all of higher education: it leaves people with large debts, and many don't get jobs; imagine the article you could write about humanities Ph.D. programs! Still, Segal's earlier article pointed out some of the ways in which rankings pressure has pushed some law schools to be less than candid about their graduates' job prospects, which can't be good. (And people like making fun of anything that has to do with lawyers. It comes with the territory.)

Segal's latest article, however, goes for laughs at the expense of substance. It opens, for example, with a scene in which three first-year associates are stumped by the question of how to "accomplish a merger." The answer, it turns out, is that you file a form with the secretary of state. "What they did not get, for all that time and money," Segal moralizes, "was much practical training. Law schools have long emphasized the theoretical over the useful, with classes that are often overstuffed with antiquated distinctions."

There is a kernel of substance here, but Segal manages to bury it behind this over-the-top example.* Is knowing what form you need to file where really the difference between a good legal education and a bad one?** Procedural details are the kind of thing that is best learned on the job. Knowing how to clear a jam in the copy machine is probably one of the most important skills a first-year associate needs to know (judging from my experience at McKinsey), but that doesn't mean there should be a skills class on using photocopiers in law school.

Although I am nominally a law professor, I haven't taught a day of law school in my life (I'm on leave now), so my impressions on mainly based on being a law student and a summer intern. My first summer, when I was doing legal services, I learned a tremendous amount that I hadn't learned in law school. I learned how to use those funny folders that have two metal prongs sticking up, and how to use the two-hole punch so you could put paper in those folders. I learned that if you want an exemption from a filing fee because you can't afford it, your statement of financial condition has to be on pink paper. Perhaps most importantly, I learned which person you should avoid in the clerk's office because he was certain to give you a hard time about your forms. These are all necessary skills of any good lawyer in that office—but that doesn't mean they should be taught in law school.

This shouldn't be surprising. Our economy runs on the premise that some things are best learned in school and some things are best learned on the job. You learn basic math in school; you learn how to use a particular piece of actuarial software on the job. If the only thing you needed to know to be a lawyer were procedural skills (by which I don't mean "procedural" in the legal sense), then we wouldn't need law school at all; we would just have apprenticeships, which is the way it was in the eighteenth century.

But it isn't. Back to me. Despite not knowing how to use those two-pronged folders, I did some valuable work that first summer. In particular, I wrote large chunks of a brief and reply brief that, largely unedited, were submitted to the state supreme court. We won. (I'm not saying that my sections were the difference—they weren't—only that experienced lawyers who were good enough to win a state supreme court case thought my sections were good enough to include alongside theirs.) I could not have done that without my first year in law school.

The most fundamental thing you need to do legal work, I believe, is an understanding of what the law is (which is more than knowing what the laws are), how it works, how courts make decisions, and how to make legal arguments. That is something that, based on my own limited experience, law school does a decent job of teaching. "Antiquated distinctions" matter, too. For example, whether your client is convicted of murder or manslaughter can depend on whether he exhibited "malice"—but to know what malice means in a legal context, you have to know the case law, some of which dates back to the nineteenth century if not earlier. But that's not the whole story.

On top of that foundation—let's call it "theoretical"—you need to have the ability to get things done. Not only do you have to identify legal issues—something that a traditional legal education does include—you have to be able to research them, come up with your own arguments, and write them down (and, in some cases, argue them aloud). This is an area where traditional law school classes may not do that well. Looking back, the most valuable classes for me—the ones that gave me the ability to write memos and briefs—were probably my first-semester small group (which included a legal research and writing component) and my clinics. Law schools in general are moving toward more and more clinics; I believe at Yale something like 80 percent of students do at least one clinic, and many students do them throughout school (I did six semesters). But you can still graduate from law school without doing a clinic.

So I think it's true—and this is the kernel of truth in Segal's article—that there are things that are better taught in school than on the job and that law schools could do a better job teaching. (Knowing what form to file where, however, is not one of those things.) There's a valuable discussion to have, and many law schools are having it now, about how to make law school more practical and give students more of the skills they will need to be successful lawyers. Better writing, which Segal does mention, is something that could probably use more attention. (Although one could also ask how people are making it through the American educational system—and most law students did very well in college—without learning how to write well.) More exposure to real or simulated cases and documents also falls into this category.

Bear in mind, however, that these things require closer supervision (clinics in particular, since you're dealing with real people's real lives) and hence are much more expensive than traditional classes. And you can't simultaneously say law professors are overpaid and that there should be more practical education. Law professors make more than professors in many other fields for the same reason that med school professors make even more: it's compensation for foregone income in practice (which starts at $170,000 for a first-year associate in a big corporate law firm—almost twice as much as the average faculty starting salary). It's true that there are some people, like me, who never considered working at corporate firms; but if you think law schools should offer more practical training, you will need even more people with significant firm experience, and they aren't going to work for free.

So before we start teaching Forms 101 and Forms 201, let's try to remember what school is for—even a vocational school. (Would you want your internist not to know, say, how the immune system works, but just how to order blood tests and write prescriptions?)

* And this isn't the silliest example. As others (I forget who) have pointed out, he makes fun of an article entitled "What Is Wrong With Kamm's and Scanlon's Arguments Against Taurek"—but doesn't point out that it is a philosophy paper written by a philosophy professor and published in a philosophy journal. That seems to me like the kind of error that requires a correction—the Times is basically our paper of record, after all—but there still isn't one.

** Besides, how to "accomplish a merger" is a vague question. My first thought was that there are different ways: one is to do a straight-up merger between the two companies; one is for the acquiring company to create a shell subsidiary and merge the target into it; one is to create the shell subsidiary and merge that into the target. Which one you choose depends on various factors—in particular, whether you want to avoid a vote by shareholders of the acquirer. This is the kind of thing you do learn in law school, and is a lot more important than where you file what form.

Simon Johnson's Blog

- Simon Johnson's profile

- 78 followers