Kris Spisak's Blog, page 21

January 25, 2018

Writing Tip 337: “Nick of Time” vs. “Knick of Time”

Who is this Nick we speak of? He must be a time-traveler. No, that doesn’t sound right. It must be “knick of time,” right? Right?

Who is this Nick we speak of? He must be a time-traveler. No, that doesn’t sound right. It must be “knick of time,” right? Right?

Wrong.

Sometimes our brains want to over-complicate things, believing the simple answer can’t be right and that it must be something more profound. In this vein, I’ve seen “nick of time” written a number of ways—“knick of time” and even “gnick of time” among them. However, plain old “nick” is the correct form for this idiom.

Remember:

“Nick” is a name, but “nick” is also the word for a small notch, chip, or wound; the action of making this small notch, chip, or wound; and the action of stealing, among other definitions. The phrase “nick of time” is in reference to a measurement of time, as in a measurement between nicks on a stick.

“Knick” isn’t actually a word. “Knicks” is an abbreviation of “Knickerbockers,” meaning a resident of New York or the pro basketball team. “Knick-knack” is a small ornamental object. “Knickers” is another word for underwear. Somewhere in there, there’s a great “knick of time” story hiding about a buzzer beater shot, nostalgic finds in a grandparent’s attic, or who knows what about time-traveling underwear—but this isn’t what you’re looking for in most situations.

So there you have it. Just in the nick of time, before you misspell this phrase in your next correspondence, you have your answer.

Interestingly, the “nick” of “a nick in time” traces its roots back to the Old English word gehnycned and the Old Norse word hnykla, both meaning “to wrinkle.” If you’re a fan of Madeleine L’Engle‘s A Wrinkle in Time, allow your mind now to be blown.

Aren’t words fascinating?

Join 600+ subscribers and sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more tips like this.

The post Writing Tip 337: “Nick of Time” vs. “Knick of Time” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

January 23, 2018

Trivia: The Origin of “How do you like them apples?”

Good Will Hunting fans and language lovers alike have wondered about the origin of “How do you like them apples?”

Good Will Hunting fans and language lovers alike have wondered about the origin of “How do you like them apples?”

Where on earth did this phrase come from? Orchard owners? Apple thieves? Really proud produce managers?

The exact etymology of the phrase “How do you like them apples?” is a bit fuzzy, but many sources point to the idea that a specific type of mortar during World War I was nicknamed a “toffee apple.” It was large and spherical, which didn’t allow it to fully fit in the firing tube and gave it a candy apple appearance. It’s believed that the soldiers in the trenches were the first to say this phrase, “How do you like them apples?” upon firing the mortars across enemy lines.

More brutal than you expected?

Etymology, man. Stealing phrases from the trenches. Literally.

Join 600+ subscribers and sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more language trivia like this.

The post Trivia: The Origin of “How do you like them apples?” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

January 16, 2018

Trivia: The Origin of “Unfriend”

I don’t know if this sheep was ever really your friend, but I don’t doubt he’s unfriending you right now.

Did you know “unfriend” isn’t a new word? To “unfriend” someone might make you think of social media, but according to the Oxford English Dictionary, the action of no longer being friends with someone has been called “unfriending” since 1659.

My personal favorite part of this word history is that “unfriend” has been recorded as a noun as far back as 1275. Now, I’m not quite sure if a medieval “unfriend” is the same as a “frenemy” or is someone you’ve simply cut ties with, but either way, aren’t you excited to know that language doesn’t evolve as quickly as we think it does sometimes?

Join 600+ subscribers and sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more language trivia like this.

The post Trivia: The Origin of “Unfriend” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

January 11, 2018

Writing Tip 336: “Connote” vs. “Denote”

This rowboat with the stretched out legs inside of it connotes a sense of relaxation and an adventurous spirit. Nothing is being denoted here. Do you understand the difference?

If you’re using words like “connote” and “denote” to elevate your communications, you’re already set to take on the world, using your vocabulary to strut your stuff. The problem comes when you don’t actually realize what you’re saying.

That’s never a good thing.

When it comes to “connote” vs. “denote,” think of “connections” and “definitions.”

Remember:

“Connote” means to show a connection or suggest an idea (but not literally)—for example, your slumped posture connotes that you need a vacation.

“Denote” means to refer to an exact meaning, a literal definition—for example, a driver’s license denotes that you are allowed to be behind the wheel on your next road trip; a “reserved” sign denotes that a certain row boat is unavailable.

Words, images, and symbols “connote” and “denote” ideas. If we’re talking about people, of course, then you would need words like “imply” and “explain.”

When you take the time to step your business communications up a notch, you can appear more educated, more thoughtful, and more prepared for the next level. Adding words like “connote” and “denote” into your everyday language is one way to start bringing you there, but just make sure you’re getting it right.

Happy writing, everyone!

Join 550+ subscribers and sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more tips like this.

The post Writing Tip 336: “Connote” vs. “Denote” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

January 9, 2018

Trivia: What is the Origin of “Long Johns”?

When it’s cold enough to freeze bubbles, these are the kind of stories to keep your insides warm and giggly.

Some etymology stories might be the product of fiction, but sometimes, they are so good, you have to hope that they’re true. This is the case of the tale concerning why we call long johns, “long johns.”

Merriam Webster tells us that the term “long johns” has been used to describe this long underwear since 1941, but when you dig a little deeper, you can come across the same story again and again:

In the late 1800s, an Irish-American boxer named John Lawrence Sullivan rose to fame because not only was he unbeatable, not only did he win the last bare-knuckle world heavyweight title bout in the 75th round after recovering from vomiting in the 44th, not only did his trainer have to drag him away from bars the full duration of his training. but he was also recorded saying that, he could “lick anyone, anytime,” and would regularly jump into the ring or any other challenge in his long underwear tucked into his socks, ready to go. He did this so commonly, fans began calling the long underwear by his name.

Is this the real origin of the term “long johns”? Maybe. It’s the consistent reference though it’s not 100% confirmed. But whether it is or isn’t, can we all at least appreciate that there was a boxer so confident and so proud that this is truly how he stepped into the ring? Nightmares about stepping on stage in your underwear have nothing on this guy.

That’s something to keep you warm on a cold winter day.

Join 550+ subscribers and sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more language trivia like this.

The post Trivia: What is the Origin of “Long Johns”? appeared first on Kris Spisak.

January 6, 2018

Authors on Editing: Interview with Katherine Neville

Many writers aspire to craft intrigue, to evoke a fascination in history and the world that we live in through page-turning plots and three-dimensional characters, but few make an impact as great as international bestseller Katherine Neville, who I am honored to have joining me for the following Authors on Editing interview.

Katherine Neville’s colorful, swashbuckling adventure novels, in the epic “Quest” tradition, have graced the bestseller lists in forty languages. But her books remain hard to pigeonhole:

Neville herself has been dubbed “the female” Umberto Eco, Charles Dickens, Alexandre Dumas, and Stephen Spielberg. Her work has been reviewed and has received awards in categories as diverse as Mystery, Thriller, Historic, Romance, Science Fiction as well as classical literature. Publishers Weekly described Neville’s works as having “paved the way for books like The Da Vinci Code.” In a national poll by the noted Spanish journal, El Pais, her novel, The Eight, was voted one of the top ten books of all time.

Neville has been an invited speaker at many universities and other venues around the world, including the Today show; National Public Radio; the Voice of America; the World Affairs Conference in Colorado; The Georgia Tech Women’s Leadership Conference; the Idaho Writers Rendezvous; the Orkney Science Fair in Scotland; the Ateneo de Madrid; the University of Menendez & Pelayo in Spain; the First International Mevlana (Rumi) Symposium in Konya, Turkey; the Turkish Culture Ministry in Ankara; The James River Writers’ Conference; the Smithsonian Associates lecture series; and The Library of Congress.

Neville resides in Washington DC and Virginia, where she is restoring a fabled Japanese house from the 1960s while writing her new novel set in the art world of the 1600s.

Q & A with Bestselling Author Katherine Neville

Kris: You do so much research ahead of your novels to make sure every detail is as accurate as possible. Your books have allowed your readers to travel the world and reimagine different time periods. While I really want to ask you about that research, I’ll hold back, but how does this quest for authenticity fit into your editing process?

Katherine: The “quest for authenticity” actually involves the writing process, not the editing. If we have multiple scenes in various time periods and locales, as I always do, we have to be able to see, hear, touch, taste, smell—to experience what the characters are experiencing. It has to be tangible.

Having said this (and I am the queen of obsessive research)—no matter how fascinating your research may seem to you, if it’s not essential, it’s the editor’s job to hunt it down and hack it out. If it doesn’t serve to develop character or advance the plot, it doesn’t belong in the book. It really needs to go. “When in doubt, leave it out,” is the motto of all seasoned writers.

Kris: That’s wonderful advice. In the joy (yes, I’ll absolutely say joy) of research, there’s so much we sometimes want to share, but it has to be there for a reason. Now, after we have the story down to the essentials, what is the difference between “okay” writing and writing that pulls a reader into that time and place?

Kris: That’s wonderful advice. In the joy (yes, I’ll absolutely say joy) of research, there’s so much we sometimes want to share, but it has to be there for a reason. Now, after we have the story down to the essentials, what is the difference between “okay” writing and writing that pulls a reader into that time and place?

Katherine: Same as above. If it’s not vital, it doesn’t engage us.

Kris: Staying on that idea of engaging writing, making sure your characters are true to themselves is essential. Is this something you focus on in your editing process?

Katherine: I use numerous historic figures as characters, and I rely upon their diaries, letters, and eyewitness reports, which are often amazing! For modern (created) characters, I rely upon them to speak for themselves. When a character starts speaking, you (the writer) become like a court stenographer, just taking down their words. If you read the Paris Review interviews, you’ll notice that most famous writers say that you know you’re a real writer “when you hear your own voice.” Not really. In fiction, it’s when you hear your characters actually speaking.

Kris: So after the research, the description, and the characters, this brings us to plotting. Pacing is really hard sometimes. How do you ensure you have it right in the end?

Katherine: I was having dinner with the editor-in-chief of a major publishing house, before my books were ever published. He told me that in my first book, which he’d bought, my “pacing was slightly off.” So I asked him what “pacing” was. (Pacing is the key ingredient that is not taught in writing programs, nor discussed much in writers conferences. Why not?)

It was a question nobody had ever asked him. After some thought he said: “It’s what makes me want to turn the page!” Amen to that.

You can’t have non-stop breakneck speed nor endlessly boring detail. There has to be a rhythm to a book. For action scenes, I write prose in iambic pentameter—like gaits on horseback—like Shakespeare, in fact! (You know that The Odyssey was written in the cadence of a John Philip Sousa march!) Pacing is the most natural, organic thing about writing. It’s something that should not be taught. Like rapping or dancing, it should be felt by the writer and the reader together.

Kris: What is your favorite piece of advice for students and new writers about revisions?

Katherine: Do it right the first time. Don’t write what people (teachers, reviewers, even publishers) tell you is “literary” or “sells.” Write a story that you yourself would love to read, and read again and again, about characters you want to live with or to know!

For more depth on the craft, I recommend the premier episode of “Author Café” that I did on Sirius XM with David Baldacci & Daniel Stashower.

Becoming a better writer and editor of yourself takes many things—reading, dedication, and, above all, practice, practice, and more practice—but learning from the masters can be a powerful step forward, no matter whether you write thrillers, young adult, nonfiction, poetry, plays, journalism, graphic novels, or anything else that involves sketching words into other peoples’ imaginations.

Thank you, Katherine Neville, for your time and your words on your craft, and happy writing, everyone!

Join 550+ subscribers and sign-up for my monthly email newsletter for more interviews like this.

The post Authors on Editing: Interview with Katherine Neville appeared first on Kris Spisak.

January 4, 2018

Writing Tip 335: “Minuscule” vs. “Miniscule”

Sure, he’s “mini,” but is he “miniscule”?

Itty bitty, tiny little hiccups in our writing might not always be noticed, but that doesn’t mean we still shouldn’t try to do better—even when some people say these mistakes are okay.

“Minuscule” is a big word with a tiny meaning. Literally. It means to be incredibly small. It comes from a diminutive of “minus,” or minusculus in Latin.

“Miniscule” is a confused spelling, taking the idea of “mini” and mixing up the words. “Miniscule” isn’t the standard spelling. If you were in a spelling bee, it would be considered incorrect. However, because this word is misspelled so often, it’s starting to become an alternate form. Mini-me probably isn’t behind the surge of this spelling faux pas, but maybe remembering his work with Dr. Evil might help you remember that this isn’t the accepted usage you’re looking for.

I know what you’re thinking: How can people simply make up a new spelling and have it become normalized because of misspelling it so often? Depending on your outlook, this is the awesome or disturbing thing about the English language over time. Just like “pleaded” vs. “pled,” “light” vs. “lit,” and “imbed” vs. “embed,” words and their spellings evolve. Heck, sometimes mistakes even replace the original logical forms entirely.

Will we see this with “miniscule”? Time will only tell. But until then, let’s try to get it right, folks.

Join 550+ subscribers and sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more tips like this.

The post Writing Tip 335: “Minuscule” vs. “Miniscule” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

December 28, 2017

Writing Tip 334: “Hunker Down” vs. “Bunker Down”

There’s a strategy for being patient and waiting for something difficult to pass, and then there’s falling down after your golf ball lands in a sand trap. Which one do you mean?

There’s a strategy for being patient and waiting for something difficult to pass, and then there’s falling down after your golf ball lands in a sand trap. Which one do you mean?

The expression you’re looking for is to “hunker down.” To “bunker down” is not actually a thing.

I’ll admit that I’m taking some liberties with my second definition. To “bunker down” isn’t a real idiom, so I’m trying to find the best fit.

As a verb, “bunker” means:

To hit a ball into an obstacle like a sand trap on the golf course

To equip or fuel a vessel

As a noun, “bunker” means:

That golf course obstacle

A fortification, usually built under the ground

A large bin, chest or box

The confusion with the idea of endurance probably comes from this last definition of “bunker,” but even if you are in a bunker, you still want to “hunker” down while you’re there.

Of course, if you’re prone to bunker on the golf course, I suppose hiding there until the embarrassment passes is always another option, but I wouldn’t recommend it.

Happy writing, folks!

Join 550+ subscribers and sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more tips like this.

The post Writing Tip 334: “Hunker Down” vs. “Bunker Down” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

December 19, 2017

Trivia: God Rest Ye Merry, Gentlemen

We’re not talking about any merry gentlemen here, folks. Did you ever notice the correct comma placement of this line in “Deck the Halls”?

Join 550+ subscribers and sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more language trivia like this.

The post Trivia: God Rest Ye Merry, Gentlemen appeared first on Kris Spisak.

December 16, 2017

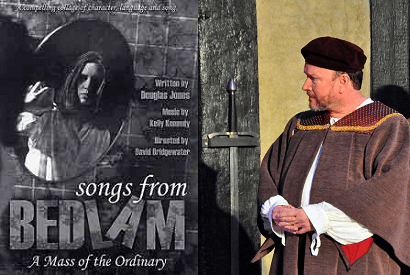

Authors on Editing: Interview with Douglas Jones

No matter how experienced a writer may be, there’s magic that can happen when you join a creative workshop with a masterful teacher. Artistic juices—no matter how active or how dormant—can come alive, and inspiration is rekindled.

This is how I feel whenever I have the pleasure to hear Douglas Jones speak about the creative process—whether in a workshop, a literary salon, or a conversation over lunch at a writing conference. I’m honored to present the following interview with him, which is chock-full of valuable advice and inspiration.

Douglas Jones has written and seen produced more than forty plays and screenplays, including the musical Bojangles (music by Tony Award-winning composer Charles Strouse, lyrics by Academy Award-winning Sammy Cahn), The Turn of The Screw, and his award-winning Songs from Bedlam. His docudrama 1607: A Nation Takes Root is on display every day at the Jamestown Settlement & Yorktown Victory Center. He was awarded the Virginia Commission for the Arts Playwriting Grant in 2006, the Martha Hill Newell Playwrights Award in 2015, and the Emyl Jenkins Award for Promoting Writing and Writing Education in 2016. He teaches memoir, playwriting, and other classes at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts and The Visual Arts Center in Richmond, Virginia, and is a voting member of The Dramatists Guild. He lives in Richmond with his wife Harriett and his daughter Emma.

Q & A with Playwright, Teacher and Editor Douglas Jones

Kris: Tell me about your editing process. Do you edit as you write, only after you finish, or a little bit of both?

Douglas: I write without editing for the first sitting, however long or short. Then I take a break and walk away: literally take a walk, or fix a cup of tea, and try to forget about the writing. When I return to what I’ve written after a break—whether it’s been an hour or a day—I reread with a critical eye for what’s missing, what’s unclear, and what I can cut. I try to cut the fat and leave enough meat to move the muscles. If I don’t know yet how to make a transition or what comes next, I’ll use xxxs as a marker and come back to it later. F. Scott Fitzgerald (among others) said you have to decide whether you are a putter-inner or a taker-outer. I’m definitely both.

I also write in whatever order the play or story comes to me. The last five lines of my adaptation of The Turn of The Screw came first. If the first thing I think of is a scene or chapter that will go somewhere in the middle, I write it down. Once I’ve found the beginning and the middle, it’s okay if my original ending no longer fits—because it helped me find the beginning. In Bird by Bird, Anne Lamott excerpts an interview with Carolyn Chute: “I feel like a lot of time my writing is like having twenty boxes of Christmas decorations. But no tree. You’re going, where do I put this?” I tell my students it’s okay to start with individual ornaments. It may take time, but you will find the tree to hang them on.

I also write in whatever order the play or story comes to me. The last five lines of my adaptation of The Turn of The Screw came first. If the first thing I think of is a scene or chapter that will go somewhere in the middle, I write it down. Once I’ve found the beginning and the middle, it’s okay if my original ending no longer fits—because it helped me find the beginning. In Bird by Bird, Anne Lamott excerpts an interview with Carolyn Chute: “I feel like a lot of time my writing is like having twenty boxes of Christmas decorations. But no tree. You’re going, where do I put this?” I tell my students it’s okay to start with individual ornaments. It may take time, but you will find the tree to hang them on.

Kris: I love that analogy, and practically every writer has been there. Shiny, beautiful ornaments can be so hard to arrange sometimes. Now, how does your work as an actor influence the fine-tuning of your writing?

Douglas: Acting and working with actors keeps me careful about fleshing out characters, because actors only have their dialogue and action. Several years ago, a friend read a scene I had written. She said, “I don’t know, Douglas—if I was playing that part, I don’t know why I would say that except that you need it said.” Then I realized I had to revisit and more fully inhabit that character, her backstory, and motivations. I want to avoid what Robertson Davies calls “fifth business,” because no one wants to play the character that just fills in the blanks.

Dialogue is hard to teach. I think either you have an ear for it, or you don’t. You must listen to people: on the bus, at the grocery, everywhere. David Mamet jotted dialogue on napkins. Jeffrey Sweet told me that if you read your dialogue aloud and listeners can’t tell when you switch from one character to another, you need to work harder on the characters. Where is he from? What kind of education has she had? What has her experience been? Everyone must be and sound specific.

Kris: Right, because if all characters sound the same, a reader hears the author’s voice, not the individuals on the page. And speaking of those unique individuals, I love a class that you teach called, “Writing the Shadow.” I think the dark side of ourselves and our creative projects can add so much depth and reality if we dare to go there. How can a writer dig deeper into the “shadow-side” of their characters?

Douglas: I think finding a character’s shadow is the difference between a mere point-of-view and a fully realized 360-degree character. St. Paul said, “For the good that I would do, I do not; but the evil which I would not, that I do.” That’s essentially depth psychology. Every protagonist has a flaw, and every antagonist has at least one redeeming characteristic. Each of us has a shadow, which shows up in our dreams and fantasies and dark imaginings. Why not use this rich material? We certainly enjoy reading about it. I think we are fascinated by Hannibal Lector because 1) he’s brilliant at getting inside your head, and 2) he eats people, so we don’t have to.

I was on a James River Writers panel discussion years ago. During the Q and A, a woman said she was working on a story about two women who were the same age, who grew up in the same small town under similar circumstances. She said she was afraid that they sounded too similar. I said give one of them a secret: something that would destroy their friendship, if the other knew. Because we all have secrets. That is why we have therapists. It’s a good thing we can’t read each other’s minds; if we could, relationships would not be possible.

I was on a James River Writers panel discussion years ago. During the Q and A, a woman said she was working on a story about two women who were the same age, who grew up in the same small town under similar circumstances. She said she was afraid that they sounded too similar. I said give one of them a secret: something that would destroy their friendship, if the other knew. Because we all have secrets. That is why we have therapists. It’s a good thing we can’t read each other’s minds; if we could, relationships would not be possible.

Kris: How does your work as an editor impact you as a writer?

Douglas: Editing other writers keeps me honest about my own work. I taught composition before I taught fiction or memoir or playwriting. The same rules apply. Interrogate your prose. Is it clear? Is it vivid? Is it to the point? Trade passive verbs for active verbs. Look for verbs hiding in nouns or phrases. Be suspicious of adverbs. One of my teachers said it takes a good writer to use an adjective; it takes a genius to use two. Avoid the word “very”—except in dialogue—because if you trust the description or the word you’ve chosen to mean what it means, “very” doesn’t change anything. What’s the difference between the beginning and the very beginning? If you describe a character as violent, do you really add anything by calling him very violent? Violent is violent. The beginning is the beginning. Trust the word.

And don’t underestimate the importance of pacing. You should always be moving the story forward. Look for opportunities to flesh out your characters, because characters drive plot. But don’t get side-tracked or self-indulgent. Don’t fall in love with all of your research. Provide only as much as the reader needs, and cut the rest. Imagine that your reader is an audience watching your story, and cut every moment when she might glance at her watch.

Kris: What is your least favorite part of the editing process?

Douglas: Those moments when I think, who am I kidding? I don’t know how to do this. Apparently, I’ve been faking it all these years, and somehow getting away with it.

Kris: And getting away with it brilliantly, I might add. What is your favorite part of the revision process?

Douglas: Finishing it, and knowing that I am finished.

Kris: How do you know when you are done?

Douglas: When I am happy. When I can’t think of anything else to add or change that would make the writing better. When I remember that I do this because I love it—not because it makes me wealthy or famous, but because I realized at some point that I am good at this, that I love doing it, and that I am able to hear and to believe it when other people say “Well done.”

Well done, indeed. There are so many insights in this conversation that no matter what you write, I’m sure you can find some gems that apply to you.

There are highs and lows to the writing process, as Douglas said. Sometimes, we feel like we’re faking it, and sometimes, we can sincerely feel that sense of accomplishment when someone compliments the work. Wherever you and your writing happen to be today, keep going. Keep editing.Who knows what will arrive in the end. The only real faux pas is if you give up.

Thank you, Douglas Jones, and happy writing, folks!

Join 550+ subscribers and sign-up for my monthly email newsletter for more interviews like this.

The post Authors on Editing: Interview with Douglas Jones appeared first on Kris Spisak.