Kris Spisak's Blog, page 25

July 22, 2017

Authors on Editing: Interview with Allan Wolf

Sometimes, I meet another writer and just go “Wow.” I’m inspired and in awe, and then I dive into that writer’s work and find myself saying, “Wow, wow, wow” once again. If you’ve ever met Allan Wolf, seen him perform, or read his writing, you’ll know exactly what I’m talking about. If you haven’t, I’m honored to introduce you to a writer you need to know now.

Allan Wolf’s The Watch That Ends the Night was named by Booklist as one of the 50 Best Young Adult Books of All Time. Two-time winner of the North Carolina YA Book Award, Wolf is an author and performance poet based in Asheville, NC. A winner of the prestigious Claudia Lewis Poetry Award from Bank Street College, Wolf’s many books showcase his love of history, research, and poetry. His latest verse novel, Who Killed Christopher Goodman? is based on the murder of a high school friend in the summer of 1979. With literally hundreds of poems committed to memory, Wolf travels the country presenting author visits and poetry shows for all ages.

Q & A with Poet, Author, and Performer Allan Wolf

Kris: At what point in your crafting of a new project does revision come into play?

Allan: I consider revision and editing two separate things. Which is not to say that they do not cross paths. In fact, they DO cross paths—and bump and cuddle and collide and dance all the time. But revision, to me is more “meta.” During revision, a writer is simultaneously looking at “the big picture” (the arc of development, the length of each passage, the motivation and growth of characters, etc) and the “controlling theme” (the indefinable, yet inevitable, “heart” of the writing).

In my experience, this type of revision happens before I write a word. I keep it in mind as I outline and plan. (I usually have some sort of outline, from simple notes to complex index cards). And then I’ll forget about it a while as I let the characters and the action take on a life of their own. I will literally write my way to what needs to be written. This may take a day, a week, a month, or so. Then I’ll stand back and look at the big picture again as I listen for the story’s “heartbeat.”

Kris: I love that. Each story does have a heartbeat. What is your advice for writers who are working on fine-tuning the rhythm of their language to those beats?

Allan: There is no substitute for reading. Read the good, the bad, the ugly. The masters. The amateurs. Novels, magazines, and maybe even a double helping of poetry. Don’t be shy. Read the words aloud. Read aloud to yourself. To your spouse. To your dog or your houseplants. (I’m not joking.) Allow yourself to fall in love with the innate rhythms and music in our language. Find writers you admire and take apart their sentences like a child disassembling a pocket watch. What makes the language tick? What makes it perfect? The rhythms do what they must do, yet they don’t distract from the content.

Allan: There is no substitute for reading. Read the good, the bad, the ugly. The masters. The amateurs. Novels, magazines, and maybe even a double helping of poetry. Don’t be shy. Read the words aloud. Read aloud to yourself. To your spouse. To your dog or your houseplants. (I’m not joking.) Allow yourself to fall in love with the innate rhythms and music in our language. Find writers you admire and take apart their sentences like a child disassembling a pocket watch. What makes the language tick? What makes it perfect? The rhythms do what they must do, yet they don’t distract from the content.

Kris: Sometimes that rhythm comes down to just the right choice of words. When you’re looking for the perfect word to polish a sentence to a shine, what is your process?

Allan: If I’m writing with pen and paper (never pencil—thank you very much, ew!) I will mark through words lightly and write replacement words between the lines or in the margins. In particular, when I write a lot of poetry, I will re-order entire lines by placing my own specialized editing marks. I’ll place A, B, C or D next to words or sentences to show the sequence. Or a, b, c, d. Or 1, 2, 3. Etc. I’ll circle whole passages. Cross out entire stanzas and paragraphs. Once the page is so confusing that I can’t decipher my own thoughts, then I’ll turn to a fresh page and transcribe it as neatly as possible and start all over again.

If I’m composing on the computer, I will change individual words and phrases, sometimes whole sentences or lines. But again, I will begin by doing a “cut and paste” of the old line, placing the new line just below the old one, then alter the new one so I can see both versions in close proximity. If one of the examples falls out of my favor, I will use the “strike through” function, so I can still see the old line or word. If I end up with so many false starts that I’m getting confused, I will use the yellow highlight function to make the best versions “pop.” And all the while I am reading aloud and sounding it all out. All the while typing with fluidity.

I have a dog-eared rhyming dictionary, though I also use rhyming word websites. And I will use the “synonym” function of my Word dropdown menu. But beware. These paint-by-numbers tools can lead to disaster in the wrong hands.

Oh yes, and I use sound-canceling foam earplugs! Really helps me to focus.

In my longer novels, I will really only find the perfect rhythm toward the end of the writing. That’s when it all “clicks” and I’m no longer second-guessing myself. Every detail becomes “inevitable” and in perfect sync with the heartbeat. Once the “down draft” of a longer novel is done, I will return to the earlier passages and rework those moments with my newfound feel. I will add a little foreshadowing to reflect the newfound realities of the latter half of the book. I will enhance the lucky moments written before I knew how well they worked to further the story and support the theme.

Kris: There is so much solid advice here for writers to sink their teeth into! Have you ever had a discovery about your work during a revision that completely reshaped what it became?

Allan: This is true of just about everything I’ve published: poem, picture book, or novel. You may as well add song lyrics to the list too. What separates the “professional” writer from the “amateur” is a dogged faith in the process of writing your way to what needs to be written. John Keats famously called this “negative capability,” the ability to embrace uncertainty. Even the most extensive and detailed outline is just a scaffold that allows a writer to access all those out-of-the-way places. The wonder, the discovery, the Truth (with a capital “T”)—all of that lies within the framework.

We writers who are lucky enough to “have” editors are faced with an additional challenge. Does an editor make a book “better?” Or does an editor merely make a book “different?” What writer hasn’t stayed up all night asking that question? Every long novel I’ve written has been reshaped based on one or two simple notes of “the” editor.

But even editors’ comments (suggestions? demands?) are just another tool toward uncovering or clarifying some greater Truth.

Kris: Right, and you’re trying to discover that greater Truth for yourself as well as clarify it for your readers. How does knowing your audience factor into your revision process?

Allan: Excellent question. We have all heard writers say they write to please themselves and not the reader. These writers are either lying or they didn’t understand the question. Most professional writers that I know have an audience in mind for what they are writing. And the needs of their particular audience are probably most influential during TWO specific moments. One: the earliest process of outlining or brainstorming (or whatever you call it). And Two: The revisions that begin after the first complete draft.

In the early stages, I will keep my audience in mind by being sure that my overall premise passes the “so what?” test. Who will even care? Who will read these words? What do I want the reader to leave with? Then I’ll set about bumbling through the first draft (what I call the “down draft.”) This may take a day for a poem, or a couple years for a novel. Luckily I work with great editors who will flag parts of my writing that will not appeal to my audience (usually kids or young adults).

Examples: I tend to use words that I call “clever,” but what my editor will recognize as “passé.” A Tween will not use the word “smitten” for example. So we end up changing it to the tried and true phrase, “in love.” In my latest novel, Who Killed Christopher Goodman, one of my characters says, “Honest Injun,” just as I realistically did back in 1979 when the novel’s action takes place. Because I am writing for young people, I changed the phrase to the more culturally sensitive, “Hand to God.” I’ve never used the phrase “hand to God” in my life and likely never will. It was a change suggested by the book’s editor, Katie Cunningham. I liked it because it still seemed to fit the character, and there you go.

I might add here, that when I’m writing for YA, I like to be sure that my stories offer some sort of hope. And clarity. And humor. And maybe a bit of magic. These needs are not specific to young people, of course, but when I see young people as my potential readers, it certainly shapes every part of my writing process.

Kris: What is your favorite part of the editing process?

Allan: My favorite part is likely every author’s favorite part: When the FedEx truck delivers the first early galleys (what in modern times is sometimes called “First Pass Pages,” or something similar). All the formatting is done. The font is settled. The words that sprang from my own mind and my heart are all right there. The whole story has been shaped and molded and hammered and hacked and rebuilt and buried and dug up and buried again.

Now, finally here it is, an actual “thing” with a life all its own.

That’s the moment when I take the manuscript to my favorite coffee shop and I order an expensive coffee drink (since you asked, a hot hazelnut soy latte, thank you very much) with a yummy scone. And I settle in to read this “thing.” This “thing” that is separate from me. I am no longer reading it as the author, the inventor, the mother or father. I am reading it now as “the reader.” And THAT, in the final analysis, is why I write. Because somewhere, some time, some how—someone will be reading what I wrote!

That is the goal, isn’t it? That someone will read what you wrote. It’s a goal that sometimes seems so far away and sometimes just at your fingertips. Even after you’re published, there’s something profound about knowing your work is being read, that the ideas that formed in your mind have been translated onto paper and then into someone else’s imagination.

The first draft, the “down draft,” as Allan calls it, is just the beginning. You have to get it down, and then you have to make your story and your characters and your words and your ideas as simple and as profound as they can be, as exquisite and as effortless-seeming as possible. No small task to be sure. But with time, practice, and great advice to follow like what Allan shares here, I have faith it can be done.

Thank you so much for your thoughts, Allan Wolf, and happy writing, folks!

Join 550+ subscribers and sign-up for my monthly email newsletter for more interviews like this.

The post Authors on Editing: Interview with Allan Wolf appeared first on Kris Spisak.

July 14, 2017

Authors on Editing: Interview with Valley Haggard

Some creative spirits are inspiring by the work they do and others by the effortless encouragement they infuse into the atmosphere around them. Valley Haggard offers the literary world both sides of this equation.

Valley Haggard has been a Waffle House waitress, a stewardess on a cruise ship, a cabin girl on a dude ranch, the book editor for Style Weekly, a board member for the James River Writers and the director of Richmond Young Writers. She is the recipient of a 2014 Theresa Pollak Prize and a 2015 Style Weekly Women in the Arts Award. The founder and curator of the online literary magazine lifein10minutes.com, Valley leads creative nonfiction workshops and retreats for adults, helping open a dedicated writing center on Cary Street in the heart of Richmond, Virginia’s Fan District in January 2017. She is the author of The Halfway House for Writers and the co-editor of Nine Lives: A Life in 10 Minutes Anthology published by Chop Suey Books Books June 2017.

Q & A with Author, Editor & Creative Inspiration Valley Haggard

Kris: What does the word “editing” mean to you?

Valley: Editing is both a siren and a monster; it excites and terrifies me. While it’s great to be far enough along in the process to have something to edit, I have found that if I’m not vigilant, I am easily susceptible to the devastating effects of perfectionism where nothing is good enough and editing is the never-ending task of Sisyphus. Which is why I’ve started setting a timer not just to write but also to edit. After a certain amount of editing, I’m learning to accept the work as it is, without editing the life out of it or stripping it all the way down to the bone.

Valley: Editing is both a siren and a monster; it excites and terrifies me. While it’s great to be far enough along in the process to have something to edit, I have found that if I’m not vigilant, I am easily susceptible to the devastating effects of perfectionism where nothing is good enough and editing is the never-ending task of Sisyphus. Which is why I’ve started setting a timer not just to write but also to edit. After a certain amount of editing, I’m learning to accept the work as it is, without editing the life out of it or stripping it all the way down to the bone.

Kris: Tell me about your editing process. Do you edit as you write, only after you finish, or a little bit of both?

Valley: Back in the day when word counts and journalism deadlines ruled my life, I painstakingly edited my work word by word until each sentence was perfect and I wanted to stab my eyes out. I’m now a die-hard believer in editing only after I’ve finished getting my big ideas and thoughts and feelings all the way out onto the page. That way, they’re not dismembered before they’re finished being born. I write for short bursts until I feel emptied out and have a collection of partial pieces to weave together into a whole.

Kris: What do you wish you knew about the editing process a long time ago?

Valley: I wish I’d known a long time ago how unnecessary it is to force a piece to emerge before it’s ready. I’ve often had a profound sense of urgency to get everything written down and finished yesterday, but I’m learning that certain stories simply will not come until they are ready. The writing and editing processes go much more smoothly when I find the natural rhythm of my work rather than forcing it.

Kris: And your natural rhythm comes out so clearly in your writing. Do you have any advice for memoir writers on how to revise their writing bravely, digging out their own authenticity and vulnerability?

Valley: I think of writing as a process of extracting splinters. When I sit down to write, I search for the physical, mental, emotional, or spiritual thorns piercing my internal landscape, and then I use the pen to extract them one by one. Honing in on these sore spots and pulling them up rather than pushing them down keeps me emotionally honest. I encourage writers to reach toward their pain and mess rather than running away from it or shellacking it over with a fake gloss. Emotionally honest writing is what appeals to me as a reader, so I try to hold myself to that standard as a writer as well.

Valley: I think of writing as a process of extracting splinters. When I sit down to write, I search for the physical, mental, emotional, or spiritual thorns piercing my internal landscape, and then I use the pen to extract them one by one. Honing in on these sore spots and pulling them up rather than pushing them down keeps me emotionally honest. I encourage writers to reach toward their pain and mess rather than running away from it or shellacking it over with a fake gloss. Emotionally honest writing is what appeals to me as a reader, so I try to hold myself to that standard as a writer as well.

Kris: Now getting into the nitty-gritty side of editing, is there a confusing word pair that is your weakness or that you seem to notice incorrect other writers’ work more than others?

Valley: OK. Yes. I cannot for the life of me retain the difference between lay and lie. I have to look it up every single time I write it down. At this point, I just write lay/lie and hope it will be corrected by a better editor than me. In elementary school, I was called a creative speller and I honestly haven’t improved too much since. I have resigned from my one-time self-appointed position as Chief of Grammar Police. I wanted to be high and mighty, but I was never very good at it myself. Now I’m just happy that my students, children and adults, are really digging deep and sharing their amazing, brilliant stories with the world, polished or not. Thank God for brilliant editors. I rely on them heavily.

It makes me so happy to hear gifted writers say how thankful they are for the editors in their lives—not as a matter of wanting credit as an editor, but as a matter of seeing writing as a partnership. Sometimes, a talented teacher like Valley is needed to draw those splinters away from the bone and into the creative light. Sometimes, editors are needed to smooth, sand, and polish brilliant ideas so that they can be as piercing as ever. Sometimes, creative work needs to be workshopped and/or beta-read to bring it from pointy to poignant.

Of course, for those looking for free editing, a few days remain on my Summer 2017 Editing Giveaway. A silly, savvy language trivia online quiz determines the winner. (Enter Grammartopia Online today!)

Thank you so much, Valley Haggard, for taking the time to chat about your creative process, and happy writing, folks!

Join 550+ subscribers and sign-up for my monthly email newsletter for more interviews like this.

The post Authors on Editing: Interview with Valley Haggard appeared first on Kris Spisak.

July 13, 2017

Writing Tip 227: “Leg Work” vs. “Legwork”

You know who has some awesome leg work? This kid. I don’t think this is quite what you mean.

The Rockettes do leg work. MMA fighters do leg work. Kids with mad soccer skills do leg work. If you’re talking about research and preparation, your legs probably shouldn’t get as much of a shout-out as you seem to be giving them.

The idea of “legwork,” as a single word, dates back to the 1890s. It seems to have originated in reference to literal running around in preparation for a greater creative or mental pursuit, but today, your legs don’t have to be involved.

The etymology of “legwork” coming from “leg work” is pretty clear, but when to use one versus the other does not always seem to be. I know spacing can be tricky, but the reminder is simple:

If you’re not actually talking about your legs, don’t use the two-word form.

Now you know. I’ve done the legwork for you, making sure you have all the right information at your fingertips. If I did this research while also pedaling my under-the-desk bike, there might have also been some leg work involved, but alas, that wasn’t the case this time. I am still wishing that there was a time in my life that I ever had the soccer moves of that kid, though.

Happy writing, everyone!

Join 550+ subscribers and sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more tips like this.

The post Writing Tip 227: “Leg Work” vs. “Legwork” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

July 8, 2017

Can Your Grammar Skills Win You a Free 75-page Substantive Edit?

Author and editor Kris Spisak has helped her clients gain literary agents and hit Amazon best-seller lists. On July 31st at 12 p.m. (EST), she’s giving away a 75-page substantive fiction edit, her most thorough editing package, for free.

Author and editor Kris Spisak has helped her clients gain literary agents and hit Amazon best-seller lists. On July 31st at 12 p.m. (EST), she’s giving away a 75-page substantive fiction edit, her most thorough editing package, for free.

Contest runs July 11 – 31, 2017

What is a substantive edit?

This heavy editing process involves an examination of clarity, logic, structure, and pacing, as well as plot, character, and setting development. More than a basic proofread, a substantive edit focuses on word usage, tone, style, voice, and total writing strength. Commentary will be given on a page by page basis, and overall project commentary will also be included.

Substantive edits are one of three editing levels that Kris tackles with her fiction clients.

What do Kris’s clients say about her work?

“The detailed critique I received from Kris Spisak was well-written and easy to decipher. She found holes in the story I didn’t realize were there. Her valuable input took the novel from okay to can’t-put-down, and I can’t wait to work with her on the next one!”

–Bess George, Author

“[The manuscript edit] I got back from Kris was gloriously beyond simple punctuation and grammar remarks. It was nothing short of a mini masters class in creative writing.”

–Karen A. Chase, Author

What do you need to do to win?

Kris has developed a simple 25-question grammar quiz based on Grammartopia, her trademarked program designed for schools, libraries, writing conferences, and business development events. If you answer her grammar and language trivia questions correctly and you do so faster than anyone else, you win your free 75-page substantive edit!

What are the rules of the game?

The winner of “Grammartopia Online – Summer 2017” will receive a free 75-page substantive edit of their fiction work, which will begin no sooner than September 5, 2017.

The second place prize is a signed copy of Kris Spisak’s book, Get a Grip on Your Grammar: 250 Writing and Editing Reminders for the Curious or Confused (Career Press, 2017).

You must be a new Grammartopia player. If you have ever played Grammartopia online or at one of Kris’s live events, you are ineligible for either prize.

Points are earned by correct answers, and the faster you answer, the higher your score will be.

You must register your Grammartopia player username and email address to be eligible.

Each player may only play one time. In the case of an individual playing more than one time–either with the same username or with different usernames–only the lowest score will be accepted.

In the case of a tie, an additional round of Grammartopia will determine the winner.

Questions about “Grammartopia Online – Summer 2017”?

The post Can Your Grammar Skills Win You a Free 75-page Substantive Edit? appeared first on Kris Spisak.

July 6, 2017

Writing Tip 226: Adding Specificity to “This” and “That”

Bonus points to anyone who knows what part of speech “this” and “that” are! (See the end of the blog for the answer.)

If you’re talking about this, that, and the other, does everyone else in the conversation have a clue about what you’re discussing?

“This” and “that” are great words. They help with specificity when you’re talking about this bird in a nearby tree versus that bird over on the wind vane. They help distinguish between this mongoose and the one named Rikki Tikki Tavi. However, when you start dropping “this” and “that” into your writing without any clarifying words, it’s a bit like posting unfinished signage on a road. It’s often a bit confusing.

For example, “This is the coolest thing I’ve ever seen. Did you see that? How about this? That was astounding!” You have no clue what I’m talking about, do you? Sure, this sample might seem a bit extreme, but watch how “this” and “that” trickle into your email communications, your storytelling, your social media posts, and any other sentences that you might put down.

My advice is to watch out for any “this” or “that” that leaves your reader hanging. Treat them like adjectives where the modifier needs to be present. (Yikes! Grammar jargon snuck in. Ignore that!) To rephrase, treat them like they are sign posts. They need to do more than point; they need to explain what they’re pointing at. Adding a single word of explanation gives them so much more clarity.

While you’re at it, watch out for “these” and “those,” too. They can be equally vague.

And to answer my earlier question, these words (see what I did there?) are all pronouns. Did you get it right?

Join 550+ subscribers and sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more tips like this.

The post Writing Tip 226: Adding Specificity to “This” and “That” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

July 1, 2017

Authors on Editing: Interview with Luisa A. Igloria

No matter what we write, we can learn a lot from poets. Knowing how to make the most out of every word, how to find rhythm in language, and how to convey a point with subtlety and poignancy is a talent we should all aspire to.

The following interview with poet Luisa A. Igloria is full of valuable takeaways and gives a glimpse into the writing life of a gifted teacher and writer.

Luisa A. Igloria is the winner of the 2015 Resurgence Prize (UK), the world’s first major award for ecopoetry, selected by former UK poet laureate Sir Andrew Motion, Alice Oswald, and Jo Shapcott. She is the author of the chapbooks Haori (Tea & Tattered Pages Press, 2017), Check & Balance (Moria Press/Locofo Chaps, 2017), and Bright as Mirrors Left in the Grass (Kudzu House Press eChapbook selection for Spring 2015); plus the full length works Ode to the Heart Smaller than a Pencil Eraser (selected by Mark Doty for the 2014 May Swenson Prize, Utah State University Press), Night Willow (Phoenicia Publishing, Montreal, 2014), The Saints of Streets (University of Santo Tomas Publishing House, 2013), Juan Luna’s Revolver (2009 Ernest Sandeen Prize, University of Notre Dame Press), and nine other books. She teaches on the faculty of the MFA Creative Writing Program at Old Dominion University, which she directed from 2009-2015.

Q & A with Award-winning Poet Luisa A. Igloria

Kris: Do you edit as you write, or do you save your internal editor for a later stage?

Luisa: Because I’ve built up a daily writing practice (writing at least one poem a day for the last six years plus some (as of today, 2413 days or 6 years, 7 months and 9 days), I have learned to revise as I write. For my daily writing practice, my process is primarily structured around the idea that every day, for anywhere between a half hour to an hour per day, I will come to my writing. I don’t set a particular time of day—because I’m a full time academic, a mom, a spouse, and have many responsibilities on any given day, I have learned to look for those pockets of time which can then be widened just a bit so I can drop down and come to my writing there. That can be anywhere as well—in between classes, waiting at the dentist’s, waiting for my daughter to come out of school, waiting for the rice or a roast to cook before dinner; or late at night, after I’ve done my class preparations or grading, and am sipping one last coffee before bed. When I am there in the space I’ve ordained for writing, I focus my attention on nothing else. I look forward to this and cannot imagine not writing every day now.

Luisa: Because I’ve built up a daily writing practice (writing at least one poem a day for the last six years plus some (as of today, 2413 days or 6 years, 7 months and 9 days), I have learned to revise as I write. For my daily writing practice, my process is primarily structured around the idea that every day, for anywhere between a half hour to an hour per day, I will come to my writing. I don’t set a particular time of day—because I’m a full time academic, a mom, a spouse, and have many responsibilities on any given day, I have learned to look for those pockets of time which can then be widened just a bit so I can drop down and come to my writing there. That can be anywhere as well—in between classes, waiting at the dentist’s, waiting for my daughter to come out of school, waiting for the rice or a roast to cook before dinner; or late at night, after I’ve done my class preparations or grading, and am sipping one last coffee before bed. When I am there in the space I’ve ordained for writing, I focus my attention on nothing else. I look forward to this and cannot imagine not writing every day now.

As I write, I review and revise fairly quickly. I often read lines aloud to myself. I listen for the sound of things. But no matter how close the writing and revision parts of my process are, I think the most important thing to do is to keep myself open and limber. In the writing/generative process, keeping open allows the poem’s energies to find themselves (subject, logic, development, feeling, tone). In the revision process, keeping open allows what we’ve learned about editorial/managerial processes over language and form to work in the service of the poem and not against it.

Kris: Sometimes finding the right word can be so hard. What is your advice for other writers struggling to elevate their language and find the absolute perfect fit?

Luisa: I love dictionaries. I like just flipping through dictionary pages and allowing words to just simply catch my attention. Thesauri also work in the same way for me. But the contexts surrounding words really define how we use them, and therefore our selection of them for our purposes. So then if the dictionary/thesaurus exercise doesn’t work, what usually rescues me is memory. In particular, if I try to think of the textures (not just the 5 senses, but some other more specific physical or material sensations associated with them) that attach to a memory, usually this is more helpful for better finding the right word I want to describe something.

Kris: When editing for rhythm, how can you be sure that you have it right?

Luisa: I think “getting it right” can mean many things for different kinds of poems. “Getting it right” doesn’t mean only getting a certain form down pat—as the question implies, it’s also about the music that language creates. I like to read the line(s) aloud. I try revisions of syntax, some other small reversals: for instance, moving the position of lines and stanzas in the poem. What does the poem sound like if the last line were read first and one went backward from there? Also, we often think in terms of familiar structures like demonstrative sentences. So I like to break up my own sense of rhythm just to listen for the differences, the possibilities for surprise—which sometimes are more important than regularity or “correctness.”

Kris: A powerful poem evokes emotions and themes rather than explicitly stating a point, which is something I’ve found newer poets sometimes struggle with. How are you sure that you’re never preaching?

Luisa: When it comes to this, I’ve found that understatement and “less is more” are important reminders. Also, remembering that our job as poets is never to “conclude” a poem by “driving home a point”—poetry is really about the embodiment of experience in language. The poets in one of my graduate workshops had a phrase for when poems or poem drafts sounded too didactic, too heavily stating a point—they said, “Oh, there’s a knowledge stone at the end of the poem.” You can almost hear when that happens: dun-dun. Letting concrete particulars do the work is so much more important—allowing images to speak for themselves. Also, I tell my students: invest in nouns and verbs and in their capacity to do the muscle work in poems—more than adjectives or adverbs.

Kris: What do you wish that you knew about the editing process a long time ago?

Luisa: That it’s okay to not know everything about a poem when you’re working, or even when you’re beginning; that sometimes the most important discoveries come in the process of writing. Also, that it’s okay for the poem to not resolve everything. That mystery can be such an important part of a poem’s power.

A poem’s power. The power of words and language and well-composed ideas. These are the tools that can be illuminating and revolutionary, entertaining and thought-provoking and piercing.

I love Luisa’s idea that “sometimes the most important discoveries come in the process of writing.” It reminds me of Joan Didion’s words, “I write entirely to find out what I’m thinking, what I’m looking at, what I see and what it means. What I want and what I fear,” but also Henry Miller’s idea, “Writing, like life itself, is a voyage of discovery.”

Once the words are down, they can be eye-opening, and if they aren’t, we need to remember that they are composed of (digital) ink, not immobile stone. When we take the time to finesse our language use, brilliance can arise.

Thank you so much to Luisa A. Igloria for joining me for this interview, and happy writing, folks!

Join 550+ subscribers and sign-up for my monthly email newsletter for more interviews like this.

The post Authors on Editing: Interview with Luisa A. Igloria appeared first on Kris Spisak.

June 29, 2017

Writing Tip 225: “Poisonous” vs. “Venomous”

Okay, sometimes my blog images scare me a little. This is another one of those times.

I have good news for you. Contrary to what you might have heard, there’s no such thing as a poisonous snake.

But here’s the bad news, this doesn’t make your next romp through leaf piles in the woods any safer.

Remember:

“Poisonous” means something that causes illness or death if eaten, touched, or inhaled.

“Venomous” means something that injects venom into another creature, most commonly through a bite or a sting.

The key difference here is that idea of injection. Snakes aren’t poisonous to the touch, if eaten (um… yikes?), or if inhaled (yeah, no clue why you’re sniffing snakes). It’s their venom that is dangerous. Hence, snakes can be venomous, not poisonous.

Admittedly, only ten percent of snakes are venomous, so maybe we all shouldn’t be as nervous around the slithering, fork-tongued creatures as we often are—though, if you ask me, I’ll still be steering clear of any that come across my path—whether or not they’re poisonous, whether or not they’re venomous, whether or not they’re offering apples, whether or not their bites are actually exacting (or extracting?) revenge. Too far? Honestly, I’m not sure you can convince me otherwise.

Join 550+ subscribers and sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more tips like this.

The post Writing Tip 225: “Poisonous” vs. “Venomous” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

June 27, 2017

Trivia: “Goodbye”

Join 550+ subscribers and sign-up for my monthly email newsletter for more language trivia like this.

The post Trivia: “Goodbye” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

June 24, 2017

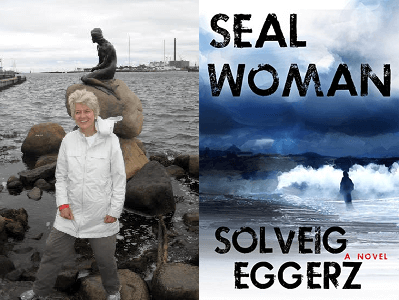

Authors on Editing: Interview with Solveig Eggerz

When I discover powerful writers who are also teachers, I’ll admit that I always get a bit excited and my questions jump out of my mouth rapid fire. Being a talented wordsmith doesn’t always mean an individual can explain the process of writing to another, and that’s why I’m excited to present the following interview with Solveig Eggerz, which is full of bite-sized takeaways for writers across any genre.

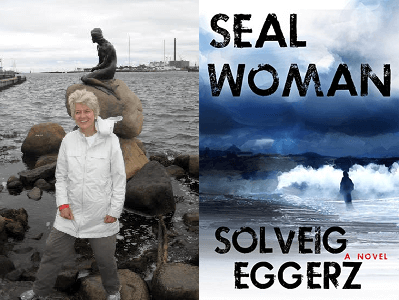

Solveig Eggerz, a native of Iceland, is the author of Seal Woman, an award-winning novel informed by the selkie legend. For many years she told folk and fairy tales in schools in Alexandria, Virginia. Using a blend of told and written story, she teaches writing at the Writer’s Center in Bethesda, Maryland, as well as “Sharing our Stories,” a writing program for individuals emerging from difficult circumstances. She holds a PhD in comparative literature from Catholic University. Her writing has appeared in such places as The Northern Virginia Review, Delmarva Review, and Palo Alto Review.

Q & A with Novelist and Teacher Solveig Eggerz

Kris: Is revision something you look forward to, something you dread, or something in the middle?

Solveig: I enjoy revision because it is often the stage at which I begin to grasp what I am trying to say and how to say it.

Kris: At what point in your writing process do you begin editing?

Kris: At what point in your writing process do you begin editing?

Solveig: I never do the nit-picky copy editing until I am finished writing.

Kris: What about revision on deeper levels? Do you revise in stages with different focuses?

Solveig: I revise a million times, sometimes focusing on a particular character, at other times on an event that needs to be fleshed out. Sometimes I revise in direct response to what my 8 person writers group recommends.

Kris: Oh, there’s so much power in a trusty writers group or critique partnership. That’s a great note to mention. Now, a sense of is so important in Seal Woman. How do you revise your writing, ensuring that you properly capture a true sense of the setting in your story?

Solveig: I go back to the place where I first introduced the setting and make sure I have provided enough detail for the reader to be able to envision the place. Advice: ground your character early in a particular, easy to envision place.

Kris: What about your characters? How do you ensure that your characters are truly alive?

Solveig: I keep asking them this question: given who you are (i.e., considering all your character traits), how are you most likely to respond to this particular situation?

Kris: It’s fascinating to me that you phrase this as a question to your character rather than a question to yourself. Characters can absolutely lead the way so often if we only let them. And speaking of what drives your story, when you’re weaving folklore into your own tale, what are you thinking about as you revise your telling of these old stories?

Solveig: What I am thinking about is–does this fairy tale really have any relationship to the story I am writing? If it does, what part of it? If I choose the sameness between my story and the old tale carefully, I do not have to revise the fairy tale.

Kris: What is your favorite editing tool or trick?

Solveig: Reading aloud. Wherever I stumble, I know I can discard something.

Kris: When you want to make sure every sentence shines, what do you look for?

Solveig: Extra verbiage, the use of “very.” Passive voice is usually a no, no. I try to replace all kinds of helping verbs and wimp verbs with verbs that actually show the action. For example, change “he drew a conclusion” to “he concluded”; “he engaged in cutting his steak” to “he cut his steak.”

Solveig: Extra verbiage, the use of “very.” Passive voice is usually a no, no. I try to replace all kinds of helping verbs and wimp verbs with verbs that actually show the action. For example, change “he drew a conclusion” to “he concluded”; “he engaged in cutting his steak” to “he cut his steak.”

Kris: When do you know that your book is actually “done”?

Solveig: When I have resolved what I set out to resolve.

Kris: What is something about revision that you think more writers should know?

Solveig: That revision is where the real writing takes place. The first draft is just a prologue to writing.

We talk of pre-writing, but this idea of the first draft of a book being merely a prologue to the writing process is both true and intimidating beyond belief. If we can hold that idea in our minds, though, it alleviates so much of the pressure of that initial storytelling. The revision can come later, the fine-tuning, the cajoling of words into art, the tightening of lines like a rope to tug at a reader’s emotions, and everything else we do to bring out the best in a story.

Thank you so much, Solveig Eggerz, for joining me for this interview, and happy writing, everyone!

Join 550+ subscribers and sign-up for my monthly email newsletter for more interviews like this.

The post Authors on Editing: Interview with Solveig Eggerz appeared first on Kris Spisak.

June 22, 2017

Writing Tip 224: “Ravish” vs. “Ravage”

There’s a huge difference here worth noting.

If you’re talking ‘bout the birds and the bees and the flowers and the trees and the moon up above, you might be tackling this thing called “love,” but here’s a hint: if you’re writing about a lover ravaging another, it’s not a happy love story.

To take it up a notch—and maybe a few decades forward—let’s talk about what’s happening when it’s getting hot in here.

Remember:

To “ravish” is to enrapture, to fill someone with immense delight, or to carry someone off by force.

To “ravage” is to devastate or destroy.

One can be a word that intensifies a moment. The other can be a brutal typo that makes the romance and erotica editors of the world wince.

If it helps, remember “ravishing” is an adjective that means captivating and entrancing. These are good things. Ravaging is not a good thing.

So next time you write about the stars in the sky and a girl and a guy and the way they could kiss

à la the 1964 pop charts or next time you want to quote Nelly lyrics, think hard about your spelling. There’s no worse way to kill a heated moment than with bad word choice.

Join 550+ subscribers and sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more tips like this.

The post Writing Tip 224: “Ravish” vs. “Ravage” appeared first on Kris Spisak.