Kris Spisak's Blog, page 29

March 9, 2017

Writing Tip 211: “Eek” vs. “Eke”

How does one eek/eke out a living as an ostrich farmer?

Eek! That’s the sound of me squealing either because I’m scared to death of ostriches or because spellcheck once again was not your friend.

If you’re writing about “eeking” out a living, maybe it would make sense of you’ve totally nailed the horror movie scream and are constantly cast in roles in this genre. Or maybe if you’re tending ostriches and those giant freaky birds are good at sneaking up on you. However, the expression in its correct form is to “eke out a living.”

There are in fact two words here, folks.

To “eke” means to manage or make happen with difficulty. It’s most commonly phrased “to eke out” something, such as a living, a win, or a success over spellcheck…

“Eek” is an exclamation of fear or surprise.

Are you now the one saying “eek,” realizing that you’ve been writing this one wrong for years? Take heart in that it’s a common typo, but now you know.

And you also now know I’m terrified of ostriches. (Though, if you’re a longtime reader of my blog, you might be aware of my bird-phobia already.)

Happy writing, everyone!

Sign up today to join 500+ subscribers to my monthly newsletter for more writing tips like this.

The post Writing Tip 211: “Eek” vs. “Eke” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

March 7, 2017

Trivia: What is a “Tittle”?

A “tittle” is a small mark in writing or printing, but another definition is simply a very small part.

You never realized that dot over an “i” or a “j” had a name, did you?

The post Trivia: What is a “Tittle”? appeared first on Kris Spisak.

March 4, 2017

Authors on Editing: Interview with Charles Euchner

Writing well takes some thought. It requires patience and practice. Clear, crisp communication isn’t just something for the storytellers of the world, but it’s for everyone and anyone who has a thought that they want to share.

Charles Euchner’s latest book Keep it Short: A Practical Guide to Writing in the 21st Century is a primer for everyday writers of emails and professional wordsmiths alike. His expertise on the craft of writing is immeasurable. Thus, I’m thrilled to share the following interview with him that presents tangible steps we can all take to better our writing. Pull out your pens and digital highlighters. It’s time to take some notes!

Charles Euchner—the author or editor of a dozen books who has taught writing at Yale and directed a think tank at Harvard—is the creator and principal of The Elements of Writing. He teaches one- and two-day writing seminars for businesses, authors, and teachers and students all over the U.S. and Canada.

In the past three years, Euchner has published a series of books on writing and civil rights. His books on writing— including The Elements of Writing, Keep It Short, How to Write a Book, and The One-Minute Writer—offer a complete system for all genres. He is also author of In Cold Type, a breakdown of the narrative techniques of Truman Capote’s classic In Cold Blood, and Mad Men’s Guide to Persuasion, about the popular TV drama “Mad Men.”

Q & A with Author and Writing Pro Charles Euchner

Kris: What is your best advice for writers who know that they should “keep it short” but aren’t quite sure how?

Charles: I ask: On what journey do you want to take your readers? Do you know where you and your readers are at the beginning–what you know, what you’re curious about, what problem you have to solve? Great. A starting place is a great starting place. Then I ask: Where do you want to go? You can’t get anywhere if you don’t know the destination. So what do you want the readers to know and feel at the end of your journey? Do you want them to understand a new argument, get insight from the travails of your story’s hero, or just know more facts and ideas? Once you know where you want to start and finish, figuring out the middle steps gets easier. You can ask yourself: Does this scene/detail/fact/whatever help get me from one place to another different place? If something does not advance that journey, you probably have to get rid of it.

Kris: How can a writer be sure that their intention is clear in a communication?

Charles: People know an honest writer in lots of different ways. One of the most important is how clear and direct you are. Simply eliminating all adverbs and most adjectives takes you a long way. These modifiers are really bully words: they tell the reader what to think. Most people would rather figure things out for themselves, with reliable information that you supply. So don’t tell me that someone was brilliant or the house was spooky or the plan was devious. Show me. I know, I know: “show, don’t tell” is the most cliché piece of advice that writers get. But it’s still essential to creating a good relationship between the writer and reader.

Charles: People know an honest writer in lots of different ways. One of the most important is how clear and direct you are. Simply eliminating all adverbs and most adjectives takes you a long way. These modifiers are really bully words: they tell the reader what to think. Most people would rather figure things out for themselves, with reliable information that you supply. So don’t tell me that someone was brilliant or the house was spooky or the plan was devious. Show me. I know, I know: “show, don’t tell” is the most cliché piece of advice that writers get. But it’s still essential to creating a good relationship between the writer and reader.

Kris: Absolutely. Understanding why “show don’t tell” is great writing advice is a big hurdle sometimes. We all hear it, but do we truly understand it? Great point.

Charles: You gain credibility in all kinds of other ways too. Define terms simply, so readers have the equipment they need, when they need it. Consider honest objections to your approach. Never talk down to your reader. You want to know what bugs me? The way adults talk to kids. Sometimes they talk to them like they’re pets rather than the amazing brain-sponges they are. That can carry over to writing when you know more than the audience. By the way, you should always know something more than the audience. That doesn’t make you superior. It just means that you decided to explore a topic that readers have not yet explored. So speak directly, without jargon or an attitude.

Kris: Is there a difference in writing and exploring topics for the business world as opposed to writing for other audiences? Should a writer keep this in mind while they revise themselves?

Charles: I disagree with the very idea of “business writing” as opposed to other kinds of writing. Good writing is good writing. Sure, writing for business involves a different purpose and vocabulary than, say, writing a longform narrative piece for Esquire or The New Yorker. I get that. But the essentials are the same. Understand what journey you want to give your reader. Map the steps in the journey. Test what belongs and what doesn’t. Avoid vagueness and jargon.

The key to writing in different fields is knowing what vocabulary the reader brings to the piece. When you need to introduce a new idea, define it clearly. So if you’re writing a business article for a website, you might need to define business terms like ROI, debts and liabilities, or compound interest. So define each term in its own paragraph. Tag the new term, if necessary, with a shorthand term. And then just use that tag in the same way you would with a more expert audience.

The key to writing in different fields is knowing what vocabulary the reader brings to the piece. When you need to introduce a new idea, define it clearly. So if you’re writing a business article for a website, you might need to define business terms like ROI, debts and liabilities, or compound interest. So define each term in its own paragraph. Tag the new term, if necessary, with a shorthand term. And then just use that tag in the same way you would with a more expert audience.

Kris: Do you recommend writers edit their work in phases or in one fell swoop?

Charles: Editing cannot happen in “one fell swoop.” Why? Because the brain get drained of energy when you try to perform too many tasks at the same time. In switching tasks–from one aspect of writing to another as you move from sentence to sentence, paragraph to paragraph–you lose sharpness. Your brain is like an SUV. It’s an energy-hungry machine. The brain comprises 2 percent of total body weight but uses more than 20 percent of the body’s fuel. Manage your brain’s resources. Don’t stress them.

Kris: Then, not stressing your brain’s resources, what does this step-by-step revision process look like for you?

Charles: So I use what I call the “search and destroy” method. Focus, one by one, on different aspects of a piece. First check the overall structure–whether the fragments are well-defined and put in the right sequence. Label them, using “slugs” like tabloid headlines, to capture the essence of these fragments. Then check to see if everything in those fragments speaks to that slug. If it does, keep it; if it doesn’t, toss it. Then start to assess the paragraphs, the same way. Check to see whether your sentences and paragraphs start and end strongly (remember the journey discussion above). When you’ve done all this, you will have checked most of the content. Now focus more on structure, diction, and so on.

Kris: That’s a fantastic guide to the editing process, no matter what someone is writing. And when you take a break from your own communications work, what is your favorite bookstore to pick up something perfect?

Charles: I’m a New Yorker. Could I possibly say anything besides Strand? I mean, seriously. I go there without any idea what I’m interested in, and I walk out with a few books and lots of notes of books and topics I’ll explore later. Like other cities, New York has lost most of its independent stores, but some are still here. Shakespeare still has a store on the Upper East Side. I pop into Westsider Rare and Used Books, on Broadway between 80th and 81st, whenever I can. I always discover books that slipped through the usual vetting systems–megastores like B&N, book reviews, chatters on radio.

Yes, a good indie bookstore is a fabulous place to take a break from the joys and stresses of the writing life. I couldn’t agree more. What a fabulous note to end on.

Thank you so much, Charles Euchner, for your thoughts on revision, and happy writing everyone!

Join 500+ subscribers and sign-up for my writing tips email newsletter for more interviews like this.

The post Authors on Editing: Interview with Charles Euchner appeared first on Kris Spisak.

March 2, 2017

Writing Tip 210: “Nevermind” vs. “Never Mind”

Love him or hate him, but you can partially credit Kurt Cobain for a shift in spelling that has occurred in the past twenty-five or so years around this(these) word(s).

Oh wait, wrong type of nirvana… never mind

What do you think of when you hear, “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” “Come As You Are,” and “Lithium”?

Nevermind. No, I’m not discounting my last question. “Nevermind” was the name of Nirvana’s 1991 album.

What fascinates me is that parallel with this release is the growth of “nevermind” as one word, rather than “never mind,” the two word form. It didn’t start with Kurt Cobain, but there’s a good chance that this album title played a major role in this spelling shift.

The expression “never mind” goes as far back as the 1700s, when the expression “never mind it” became popular. The “it” has simply been dropped over time.

In the present day, “never mind” meanings include:

“much less” or “let alone,” when the word/phrase is used as a conjunction, (e.g., Some don’t give Cobain credit as a musical influence, never mind as a spelling authority).

“forget about it,” “don’t bother,” or “don’t worry about it,” when it’s used as a response, (e.g., What do you think of when you think of Nirvana? A sense of peace? Never mind.)

“Nevermind,” written as one word, began appearing as far back as the 1930s, when the original verb form stemming from “never mind it,” turned into a noun. Here’s where expressions like “It’s no nevermind of yours,” came to be, with “nevermind” being synonymous with “business” or “affair.”

The single-word version has trickled into usage since that time, transitioning into a slang form for the “don’t worry about it,” definition. But just because it is commonly used does not mean that it’s commonly accepted.

Personally, I’ve enjoyed the fact that as I’ve written this post both Microsoft Word and WordPress have flagged my spelling of “nevermind,” when I’ve used it as one word. This stresses my next point:

Always use the two-word form, “never mind,” in formal writing. “Nevermind” is only for casual use.

For essays, business communications, and letters to your grandmother, use “nevermind.”

For casual uses like social media—or dare I say character dialogue—I’m completely comfortable with this one word form.

Note, some people argue that “nevermind” is always incorrect. I don’t agree, but it’s an important fact to be aware of.

Am I being a bit of a grammarian rebel by accepting this latter spelling? Perhaps. Is it the influence of Nirvana on my life? Probably not. I just believe there is a time and a place that casual-speak is okay (just like the spelling of “okay,” actually, rather than “OK”).

Interestingly, the Nirvana album “Nevermind,” was almost titled “Sheep.” We can only wonder about the state of “never mind” in the present day if that was the case.

Should we go further into what could have happened with the word “Sheep” if given such a spotlight? Oh, I think I’m going to far. Nevermind.

Sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more writing tips like this.

The post Writing Tip 210: “Nevermind” vs. “Never Mind” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

February 25, 2017

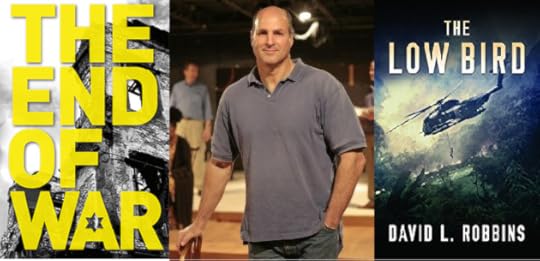

Authors on Editing: Interview with David L. Robbins

Being a writer can seem like a solo endeavor, but one of my favorite parts of my writing and editing life is interacting with other writers—aspiring writers, newly published writers, writers deep into their careers, and publishing heavy-weights. There are enough boxing metaphors in the following discussion for this description to fit here on many levels.

I first met David L. Robbins over a decade ago, and his dedication to his craft and his willingness to help others with their words have always blown me away. From high school students to military veterans seeking solace in releasing their own stories, the writers who have spent time with him have always ended up the better for it. That’s why I’m so happy to present this interview.

David L. Robbins was born in Richmond, Virginia and received his undergraduate and Juris Doctorate degrees from the College of William & Mary. He has been writer-in-residence and visiting professor of creative writing at W&M and taught advanced creative writing for the VCU Honors College. David has published twelve novels, most recently Low Bird (Thomas & Mercer, 2016), and has had several of his plays produced, including The End of War, which has its world premiere in Richmond in 2017 (tickets on sale now). He is a co-founder of James River Writers, co-founder of The Podium Foundation, and founder of The Mighty Pen Project.

Q & A with Novelist and Playwright David L. Robbins

Kris: When you finish your last page, what do you do? Do you take a breather from it for a while or do you dive right back into your revisions?

David: Neither. By the time the book is finished, it is completely edited.

Kris: Wow. I need to hear more about this.

David: Here’s what I do. I write during the morning, and when I can sense the book getting ready to be done, when maybe I’m two to three weeks away from the ending, then I start reading the book from the beginning in the evenings. I will typically add five hundred to eight hundred words a day in the morning, and I’ll take nine hundred to twelve hundred words out a night. The book will literally get shorter as I finish writing it. My goal is to arrive at the “end” of my morning writing and my evening editing at the same time. I’ll hit the final word one morning, say good, and then that evening, hopefully, if I’ve done it right, I’ll be able to edit to the end. It’s a race.

Kris: That’s fascinating. Honestly, it’s similar to the process I accidentally stumbled into with the novel I’m presently working on. I got about twenty thousand words away from the end, but I needed to see the total story before I felt like I could do justice to the ending. I took a break from the writing for this reading though. It’s amazing to me that you plow through both processes at the same time.

David: I refresh myself by doing my editing this way. I go, “Oh, that’s right, she was on that boat that sank,” or “Oh, right, her father was an alcoholic.” That lets me really crescendo the book because I’m relighting all those fires as I get into the last portion of the book.

Kris: So no pouring it all onto the page and editing it all later for you then?

David: To me, to “get it out of your hands” and “just get it out” is reminiscent of that old joke: my grandmother walks five miles a day; she’s done it for three years, and now we don’t know where she is. It creates manuscripts that are uneditable. Minotaurs so great that writers don’t know what to do with them.

David: To me, to “get it out of your hands” and “just get it out” is reminiscent of that old joke: my grandmother walks five miles a day; she’s done it for three years, and now we don’t know where she is. It creates manuscripts that are uneditable. Minotaurs so great that writers don’t know what to do with them.

I beg aspiring writers to ignore that advice, to be meticulous, to be careful, to study their own work, to interview every character and say, do you need to be in my work? Interview every act. Does it drive the story forward? Interview every setting. Are you sufficiently dynamic to be in this book? If you were to watch me in a five hour writing session, you’d see me typing for fifteen minutes. I sat down to write today at 10:30 a.m., but I didn’t write the first word until 1:00 p.m. I did nothing but think until I could see and plan five chapters out. What is the impact of the scene? How will it come back? What will it say about my characters? Until I invented the next five scenes, I couldn’t write this one. If I was just getting my book out of my hands and writing to edit later, I’d write scene upon scene I wouldn’t be able to use.

Kris: When you’re doing your heavy editing, what kind of things are you doing to your work?

David: The first thing I look for is conciseness. If I’ve said something in ten words that I feel could be said in four, I cut the six. I go on a seek-and-destroy session to find those words that do not serve. I want my work to be round twelve of an Ali-Frazier fight. They’re exhausted, and all they can do is hit each other close and with everything they have. When you pick up page one, I want you to be exhausted by page two, because it’s intense and dynamic. There’s no waste; there’s no fat. All the punches are to the ribcage, and you feel everything.

I don’t put scenes in kitchens, on telephones, or in cars, because they’re not dynamic settings. If someone’s in a car, you know nothing’s going to happen. They’re in a car. They’re going somewhere. And if they’re on the phone, you know nothing’s going to happen because they’re in different freaking countries. I vet everything. It’s manic sometimes, but I vet everything. The early writing is sometimes me working out my thoughts. The second pass, I catch that and kill it.

Sometimes, I’ll write an entire paragraph about what someone is thinking or feeling, but the thinking and feeling will almost always be pulled out of my work, because I’m telling the reader how to think and feel rather than having the character’s actions telling the reader how to think and feel. That’s me working things out. When I pull that paragraph out, it’s because it’s already clear without the explanation. I’ve done my job and didn’t know it in the moment of creation; I do know it in the hours of editing.

Kris: And how is this process different when you’re editing a play?

David: Everyone who wants to know how to write a book should write a play. If you are a young author and you want to know how to write a book, stop and write a play first. In a play, you don’t have 400 pages. You have an audience’s attention for two hours, and that includes an intermission. You can’t have a dull kitchen, or a car, or a phone call. It doesn’t work. You have to have kinetics. Characters that represent opposite viewpoints. Every scene in a play has to be a boxing ring. One comes from that corner, one comes from the other corner, they meet in the middle.

Try not writing tags, the “he said” or “she said.” This discipline forces you to concoct language that’s self-identifying. “Put down that gun” is clearly said by the guy who doesn’t have the gun. “Hello, how are you?” Who’s saying that?

Try not writing tags, the “he said” or “she said.” This discipline forces you to concoct language that’s self-identifying. “Put down that gun” is clearly said by the guy who doesn’t have the gun. “Hello, how are you?” Who’s saying that?

A stage play takes away everything from the author but action and dialogue, which means characters have to do and say what’s in their hearts, their intentions. Writing for the stage, your audience isn’t privileged with what someone is thinking. When a writer is struggling with a scene in a novel, I say, put down the book you’re working on, and imagine you’re writing it for the stage. Strip away everything but what they say and what they do.

Kris: There are so many great pieces of advice here, but what is your biggest note for aspiring writers about revision?

David: Aspiring writers suffer from a lack of confidence in their story. If you feel like you’re in front of your story, pulling it, don’t write it. You must sense that you’re behind your tale, chasing it, trying to corral it. You must feel like that scene and that story, and the hearts of these characters, their lives, their tragedies, their perils, goals, gifts, chasms are so mighty, that you question your ability to capture it. You should never have to invent. You always want to choose. You want to feel like every skill and talent you have is dedicated to containing the story, not hauling it over your shoulder.

I also have a list of what my students are not allowed to do. They cannot use ellipses, exclamation points, all caps, italics, dashes—

Kris: Not even dashes? You’re tougher than me.

David: Hyphenated words, sure, but no dashes. They cannot use facial expressions, tears, smiles, laughter—

Kris: One of the big ones on my list is nodding. There’s so much nodding in early drafts!

David: Yes, nodding. They cannot lock eyes across the room. They can’t use the word “now.” In a story, it’s always “now.” Get that out of there.

Kris: This interview is like a mini-master class in editing subtleties. I love it.

Thank you again, David L. Robbins, for sharing your writing and editing wisdom, and happy writing, everyone!

Sign-up for my writing tips email newsletter for more interviews like this.

The post Authors on Editing: Interview with David L. Robbins appeared first on Kris Spisak.

February 23, 2017

Writing Tip 209: “Breath” vs. “Breathe”

Take a deep breath. These two words are rather easy to remember. No hyperventilation required.

Take a deep breath. These two words are rather easy to remember. No hyperventilation required.

We aren’t going to do any breathing exercises here, only speaking exercises. Say these words aloud with me. Breath. Breathe.

No this isn’t a meta meditation. Just listen to the sound of the words. Only one of them says the letter “e” in the middle of the word.

Do you hear how “breathe,” the verb form, has the long “e” inside of it? Conveniently, this is also the form that has the “e” at the end. That’s just a phonetic cheat sheet right there.

I know this gets a bit tricky when the verb form changes (e.g., he is breathing; she breathed), but just because the verb form drops the final “e” on these occasions doesn’t mean you can drop it whenever you’d like. That’s not quite how spelling works.

Whether you’re gasping for breath, out of breath, giving rescue breaths, or breathing in the fresh air, make sure you’re spelling it right. Got it, everyone?

Sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more writing tips like this.

The post Writing Tip 209: “Breath” vs. “Breathe” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

February 20, 2017

Trivia: the Origin of “OMG”

OMG – This is one of those startling facts where I just know you’re going to ask for my sources, so I’ll start with those right here. The Smithsonian Magazine, Oxford Dictionary blog, and Time Magazine all agree that this acronym is much older than we might have guessed.

When Lord Fisher, an admiral used to speaking in codes and abbreviations, wrote to Winston Churchill, “O.M.G. (Oh! My God!)—Shower it on the Admiralty!!” he might have thought he was being clever, but I’m guessing he never saw how popular the expression would be one hundred years later.

If ever there was a time to write, “OMG,” I think this is it, right?

The post Trivia: the Origin of “OMG” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

February 18, 2017

Authors on Editing: Interview with Eleanor Brown

Have you ever finished a book you thoroughly enjoyed and then wondered to yourself, how the heck did the author pull that off? Maybe, for you, it was a concept that seemed too far-fetched at first glance, a protagonist that you would never guess could be sympathetic, or a cliché that you never imagined could be turned on its head. One occasion that moment hit me was when I closed the last page of Eleanor Brown’s The Weird Sisters. Not only was it thoughtful and well-crafted on multiple levels, but it was written in the first person plural—as in the narrator didn’t say “I”; the three narrators wrote in the voice of “we.”

I can only imagine the editing involved in that project to make it so true to itself the whole way through, and that’s why I’m particularly excited that Eleanor Brown is joining me for this interview.

Eleanor Brown is the New York Times and international bestselling author of The Weird Sisters, The Light of Paris, and WOD Motivation, and the editor of the forthcoming anthology, A Paris All Your Own: Bestselling Women Writers on the City of Light. She has served as a judge for the Barnes & Noble Discover Award, The BookLife Prize for Fiction, and the Amazon Breakthrough Novel Award. Her writing has also appeared in anthologies, magazines, and journals, including The Washington Post, Publishers Weekly, and The Guardian. Eleanor lives in Colorado and teaches writing workshops across the country.

Q & A with Author Eleanor Brown

Kris: If you didn’t gather this from me already, I’m a huge fan of your work, and I’m thrilled you’re letting me ask you questions about your revision process. Do you edit as you write or do you plow forward at full steam, letting words and punctuation fall where they may?

Eleanor: I’m a plower. If I stopped to go over and over what I was doing, I’d never finish anything–I’d become obsessed with making it perfect, and of course it will never be perfect. I just tell myself as I’m writing, “I can fix it later. I can fix it later.” (Honestly, sometimes I am literally saying this aloud as I type!)

I do know writers who have to edit as they go, and as long as they can do that and move forward, I say more power to them. So much of writing is figuring out what works for you and what works for you now–it’s not necessarily always the same, from project to project or even day to day. But for me, I just try to cattle drive my way through a first draft.

I do know writers who have to edit as they go, and as long as they can do that and move forward, I say more power to them. So much of writing is figuring out what works for you and what works for you now–it’s not necessarily always the same, from project to project or even day to day. But for me, I just try to cattle drive my way through a first draft.

Shannon Hale has a great quote about this. She says, “I’m just shoveling sand so later I can build a sandcastle.” I like to get all my sand shoveled and then worry about building the castle.

Kris: I love that. And when you’re ready to start checking the structural integrity of that castle and making your design choices, what is your favorite editing methodology that you’ve learned along the way?

Eleanor: I do multiple “passes”–starting with big stuff and working my way down. This is the magical secret to editing a book-length work. I work with a lot of writers who just start reading and rewriting as they go, which means they’re really just doing line editing–ending up with pretty sentences but no improvements in story or character.

I start really high-level with story and theme, and then work my way down to the sentence level. By the end, I’m doing tiny things like using the “Find and Replace” feature to look for overused words and triple-checking that I really did get the name of that street spelled right, but I have to get the story where I want it first!

Kris: Characters are sometimes one of the hardest pieces of a story to edit, and your characters are so alive. Each is unique and fully-themselves. How do you edit your writing when it comes to your characters?

Eleanor: I do multiple passes for characters–I might go through once and just mark out their goals in each scene and what gets in their way. Then when I’m satisfied with that, I’ll go through again and look only at their dialogue, for instance, to see if they’re speaking consistently….or maybe too consistently. Again, those multiple passes really are helpful to allow me to focus on one thing at a time.

Kris: Some writers’ favorite part is the research; others love the drafting and crafting; others love the later editing stages. What is your favorite part of writing a book and why?

Eleanor: When it’s done, of course!

I don’t know…each part has its benefits and drawbacks. Outlining is fun because you’re just playing, and everything is better when it’s in your head, but hard because there are so many decisions to be made. Drafting is rewarding because you can see measurable progress with word count, but painful when the words don’t want to come, or you realize you’ve gone down a wrong road. Editing is full of joy because you have something to work with and your only job is to make it better, and full of pain when you realize exactly how much work there is to do.

Actually, now I’m wondering why I do this at all. Maybe I should just go work at Starbucks!

Actually, now I’m wondering why I do this at all. Maybe I should just go work at Starbucks!

Kris: No! (And this is where my editing background is holding me back from ten gazillion exclamation points!). I know you’re kidding, but you’re touching upon a theme I’ve heard again and again in this Authors on Editing series. Every step of the writing process can be arduous, but when you push through it, amazing things can result.

One last editing question for you: do you have any grammar mistakes that bother you?

Eleanor: I used to feel this way before I had a book published. Now I know how hard it is to get your arms around 300 pages of writing, and how the fact is, no matter how many talented and skilled pairs of eyes you have on something, we are all human and we make mistakes. I just can’t work up the energy to get upset about someone using “nauseous” when they mean “nauseated”–there are bigger things to worry about in the world.

Oh man, that’s one of my favorite little-known subtleties to teach (ahem, see Get a Grip on Your Grammar for the difference). But Eleanor has a fair point. There’s a big difference in being a judgmental critic looking for details to nit-pick away at within a finished publication versus trying to help a writer catch those typos to give it a better chance of finding a publication home, or that better job, or that manifesto crafted to change the world. Not that “nauseated” vs. “nauseous” should be a word confusion on application cover letters, of course. Whether it appears in political responses is less black and white these days.

Thank you so much, Eleanor Brown, for taking the time to chat about your revision process with me, and happy writing everyone!

Sign-up for my writing tips email newsletter for more interviews like this.

The post Authors on Editing: Interview with Eleanor Brown appeared first on Kris Spisak.

February 16, 2017

Writing Tip 208: When to use “In-” vs. “Un-” Prefixes

The good news is that there is solid reasoning behind when you use the prefix of “in-” versus when you use “un-”; the bad news is that this logic will only help you if you have a solid understanding of language history.

In all cases discussed here, these prefixes mean “not” or the opposite of something. We see them in action all of the time:

Think fast: is this “insurmountable” or “unsurmountable”?* Bonus points if you say neither and go to pull out your mountain climbing gear.

Inactive

Inadvisable

Incomprehensible

Inequity

Infrequent

Unacknowledged

Unafraid

Unbecoming

Unequal

Unlimited

The answer to their usage relies on their roots. If the base word stems from a Germanic language, the proper prefix is “un-.” If it stems from a Latin word, the proper prefix is “in-.” Yes, it’s a nice simple answer, but not the easy answer that English spellers were hoping for.

If you’re still confused, don’t worry. Because this scholarly answer hasn’t been well understood over time, many words have fluctuated between prefixes. My favorite example is from the Declaration of Independence itself. There, as we all well know, is a discussion of “unalienable rights.” Are you doing a double-take? Yes, it’s written as “unalienable,” not “inalienable,” as is the more common form today—and technically, “inalienable” is the correct form, since we’re talking about a word with a Latin root.

If you’re arguing that this is unacceptable or inconclusive, I hear you. But at least you’ll have your answer now, whether it’s one that you’ll put to use or not.

*Answer – The correct word is “insurmountable,” since the root word comes from Latin.

Sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more writing tips like this.

The post Writing Tip 208: When to use “In-” vs. “Un-” Prefixes appeared first on Kris Spisak.

February 14, 2017

Trivia: The Longest English Word

What is the longest English word?

A spoonful of sugar may make the medicine go down, but contrary to what a certain magical nanny might have led you to believe, “supercalifragilisticexpialidocious” is not the answer to this question. In fact, it’s not even a word that’s universally accepted. It only appears in some dictionaries, and in these, it’s considered a casual term popularized by Mary Poppins. Sigh. Childhood linguistic reveries dashed, I know.

A real word to bring into this conversation is “sesquipedalianism,” which means the tendency to use long words, but this still isn’t the longest word in the English language.

The longest, clocking in at 45 letters is “pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis,” which is a type of lung disease, but among the longest non-scientific words are:

“Floccinaucinihilipilification” (29 letters), which is the estimation of something as worthless, and

“Antidisestablishmentarianism” (28 letters), which is opposing the withdrawal of government support of a particular church or religion.

“Incomprehensibilities”(21 letters) deserves a shout-out too, as the longest commonly-used word.

Yes, each of these words is a mouth workout, but spelling them right almost takes a touch of magic. Maybe this is where Mary Poppins can step in after all.

What do you think?

Sign-up for my writing tips email newsletter for more word trivia like this.

The post Trivia: The Longest English Word appeared first on Kris Spisak.