Kris Spisak's Blog, page 32

December 24, 2016

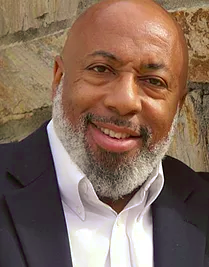

Authors on Editing: Interview with Nathan M. Richardson

A well-crafted phrase gives me the same reaction as taking that first bite into a really good cheesecake. I want to forget everything else just for that one moment and simply enjoy it for all of its luscious, delectable splendor.

As writers, many of us strive for that perfect word or that perfect line; however, poetry is an art-form focused on each and every bite. Those who can weave language, rhythm, and meaning are the ones who make me salivate and make me want to beg for their recipes.

I’m thrilled that Nathan M. Richardson, a man of many talents as a poet, a performer, and a teacher, took the time to chat with me about his writing and editing process. A reviewer of his book, Likeness of Being, once said, “This is more than a book of poetry, this is a book that resonates with the soul on a deep level.” I’d argue the same about Nathan himself.

I’m thrilled that Nathan M. Richardson, a man of many talents as a poet, a performer, and a teacher, took the time to chat with me about his writing and editing process. A reviewer of his book, Likeness of Being, once said, “This is more than a book of poetry, this is a book that resonates with the soul on a deep level.” I’d argue the same about Nathan himself.

Nathan M. Richardson is an accomplished performance poet and published author. His published collections are “Likeness of Being” and “Twenty-one Imaginary T-shirts.” He has also contributed to the following anthologies: The Poets Domain, The Cupola, The Channel Marker & Skipping Stones. Nathan teaches a variety of workshops for emerging writers and is the Head Coach of the Hampton Roads Youth Poets a division of the youth empowerment organization—Teens with a Purpose.

Demonstrating his ability to switch hats from poetry and storytelling to history and theater, Nathan is preparing for his 3rd year of The Frederick Douglass Speaking Tour, in which he delivers a remarkable portrayal of the former slave, writer, orator, and abolitionist Frederick Douglass. A short list of Nathan’s other affiliations include the Poetry Society of Virginia, Young Audiences of Virginia, and the Suffolk Arts League.

Q & A with Poet and Performer Nathan Richardson

Kris: As a poet, you know that every single word has to carry its weight. Do you have any tricks or techniques for finding exactly the right word for a line?

Nathan: I don’t know any tricks. Reading and experience build vocabulary. If my personal vocabulary fails me then, of course, I reach for the thesaurus. But I must say that poetry is more about language than it is about English. My poems are a mixture of the language and rhythms I hear around me. I sometimes cringe when I see a word so obscure the poet used a hammer and chisel to get the word to fit in the line.

Kris: Your work has an internal rhythm that is entrancing when read on the page or when spoken aloud. How do you revise your work to maintain that beat?

Nathan: My final edits always come during the memorization process. If I’m having trouble with a line rolling off my tongue without tripping, that’s a sure sign the words and my internal rhythm don’t match. Not too many people have heard me recite poetry to music. When I get the opportunity, I sometimes ask the DJ to pick a song or have a musician (guitarist, drummer, pianist) to improvise a melody at random and recite the poem without rehearsing. If I’ve paid attention to the iambic pentameter while writing the poem, it’s a seamless collaboration. I’m basically creating a RAP. Rhythm And Poetry!

Kris: That’s good advice for any writer, the idea of speaking the words aloud. The ear so often catches what the eyes miss. But knowing you have to go back to edit yourself is a learned process sometimes. How do you discuss the importance of editing with your writing students?

Nathan: For the spoken word poets I coach, it’s a matter of requiring them to listen to recordings and video of themselves. It’s easier to hear your flaws out loud than it is to see them on paper. I insist the page poets use another set of eyes (a first reader) to help them see that they did not write down what they were intending to say.

Kris: What about your own early editing process, before the final revisions that come during your memorization? Do you spill your poems all out onto the page and then edit yourself later, or do you edit as you write?

Kris: What about your own early editing process, before the final revisions that come during your memorization? Do you spill your poems all out onto the page and then edit yourself later, or do you edit as you write?

Nathan: Many times it does happen that way; the poem spills out on the page. That’s partly because most of my poems are not just one event, but a series of related observations that I might have been collecting over a long period of time. Once that bucket fills up, it tilts over and spills out.

Kris: Do you have any weaknesses of your own that you stay aware of in your own revising process?

Nathan: For some reason my finger never wants to hit the “r” when I’m typing the word “your.” Oh yes and the letter “o” when I’m typing the word “Hello.” If you’ve ever received an email from me that opened with the greeting – “Hell Kris!”, I hope you didn’t think I was cursing at you.

Kris: Do you have any pet peeves with writing, perhaps a mistake you see far too often that bothers you?

Nathan: Words like “like” and “because” and the phrase “you see” really make a poet sound desperate to ask a reader/listener to “see” what he’s describing.

Kris: Has working within the orations and texts of Frederick Douglass taught you anything about the use of words?

Nathan: It’s given me a great respect for even the average writers of the 19th century. It seems we have, for the sake of brevity, stopped using a lot of very powerful words in the English language. Speeches were much longer then, and it was not unusual for audiences to stand in the rain the hear great speakers. The average Douglass speeches were at least an hour long. By comparison, the edited versions that I offer my audiences are around 6 minutes in length. It’s almost like turning the 5 page Emancipation Proclamation into a Haiku. But it’s not that hard, Douglass’ writing is very poetic. I actually use a combination of editing and the Found Poem process to produce my stage versions of such speeches as “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July,” “Self Made Men,” “The Haiti Speech,” and “Woman Suffrage.” I never add or rearrange any words. The memorization process is the same that any spoken word poet might apply to memorizing a poem.

Kris: Many people don’t realize that storytelling is an art. It is a craft that can be learned and improved just as much as any written work. In your opinion, how can one turn a solid story into one that will have listeners on the edge of their seats?

Kris: Many people don’t realize that storytelling is an art. It is a craft that can be learned and improved just as much as any written work. In your opinion, how can one turn a solid story into one that will have listeners on the edge of their seats?

Nathan: This goes all the way back to Homer and the Iliad. Stories improve during the process of telling and retelling. There are plenty examples of classic stories and songs that went through generations of edits (many times by people other than the original author) before settling on the versions we know today. This re-telling is the oral version of the written edit.

And Nathan’s right. This editing process we so often embark upon has a long history that we often forget about. Homer edited his work, as did Shakespeare, as did Frederick Douglass, as we all should. The cajoling of our words and ideas is not always simple, but when we get it right, every once in a while, we can bring an audience to their feet. Nathan M. Richardson knows this well.

Thank you so much, Nathan, and happy editing, everyone!

Sign-up for my writing tips email newsletter for more interviews like this.

The post Authors on Editing: Interview with Nathan M. Richardson appeared first on Kris Spisak.

December 22, 2016

Writing Tip 200: “Imposter” vs. “Impostor”

One of them has to be an impostor–uh, imposter?–right?

When I came across one version of this word recently, I did a double-take. It simply didn’t look right to me, and as an editor, I like to be thorough. I can’t let typos slip through my grasp—even if Microsoft Word allows them. (It happens more than you might think.)

So I did my research and learned “imposter” was not the impostor I thought it was. It’s entirely acceptable. Both the “impostor” and “imposter” spellings are considered correct, and “imposter” even has an edge in Australia and New Zealand.

But where’s the grammar hullaballo? Where is the passion that drives Oxford vs. serial comma wars? Where is the backlash over the fact that a single word can have two spellings? Editors can have their persnickety moments, but apparently the “impostor” vs. “imposter” debate simply isn’t something that ruffles feathers.

Coming from the French imposteur, both “impostor” and “imposter” have been around for centuries, and everyone’s apparently cool with that. Bomb diggity. Fantabulous. I suppose in an era where there’s so much aggression in the world, we should be okay with this. Different beliefs can be valid, after all. Varying points of view can contribute new ideas to the conversation.

I was just convinced “imposter” was the impostor. Apparently, though, I had a new think coming.

This is Writing Tip #200 after all (insert confetti throw here). It’s good that I’m learning a lot along the way too.

Happy writing, everyone!

The post Writing Tip 200: “Imposter” vs. “Impostor” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

December 20, 2016

Trivia: Folk & Folks

December 17, 2016

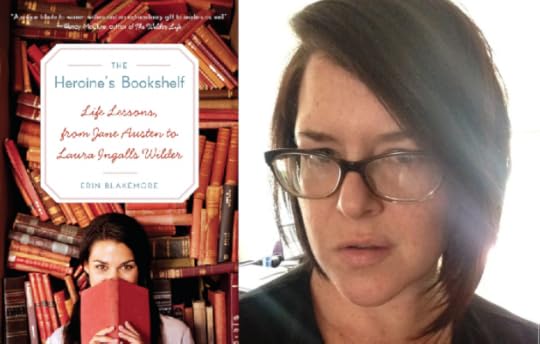

Authors on Editing: Interview with Erin Blakemore

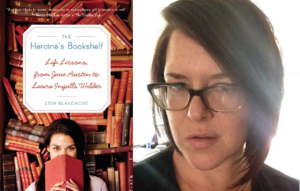

Back in 2012, someone put Erin Blakemore’s book, The Heroine’s Bookshelf: Life Lessons, from Jane Austen to Laura Ingalls Wilder, in my hands, and I gobbled it up like a guilty pleasure. When it comes to the classics, we all have our favorites, and many of mine include heroines that simply cannot be forgotten. They are power houses of strength—whether they seem it or not, whether they themselves realize it or not. The Heroine’s Bookshelf analyzed so many characters I knew so well that I could practically call them friends and allowed me to revisit each of them in a new light.

The best books are the ones that stay with you long after you close their pages. Ironically, Erin’s book about so many books had that same effect on me.

Erin Blakemore is a Boulder, Colorado-based journalist, historian, and author. Her work has appeared in publications like TIME, The Washington Post, Smithsonian, and more. Her debut book, The Heroine’s Bookshelf: Life Lessons from Jane Austen to Laura Ingalls Wilder, was published by Harper in 2010 and won a Colorado Book Award for nonfiction. Learn more about Erin at www.erinblakemore.com, or follow her on Twitter @heroinebook.

Q & A with Author & Journalist Erin Blakemore

Kris: You’ve said that you’re a person who gets paid to be curious. I know how that curiosity can drive what you choose to write about, but does that curiosity ever drive how you can put together a sentence, open an article, or revise a chapter?

Erin: Absolutely. I’m drawn to narrative, so I always try to find a “make me care” moment to insert, regardless of the length of a piece. What’s the nugget or anecdote that’s going to make someone talk about the piece at the dinner table or the next time they see their friend? Usually, that little kernel is the thing that got me into the idea to begin with. I try to let that be my guide.

Kris: Some writers’ favorite part is the research; others love the drafting and crafting; others love the later editing stages. What is your favorite part of writing a book and why?

Erin: RESEARCH. It’s the historian in me; I could do the research all day long. In part, it’s a procrastination technique—with longer-form work, the drafting is incredibly difficult for me for whatever reason, so research is something I cling to as long as possible. I always try to remember the reason I’m doing the research, though. Sure, it’s cool to know a lot, but it’s a lot harder to be selective with the details I choose to reveal and not throw the veritable book at my reader. As long as it isn’t a crutch and it gives context and depth, it’s worth doing. That said, at some point, I have to cut myself off and, you know, write.

Kris: Is your editing process different when you edit a book versus when you edit a shorter essay or article?

Erin: So, so different. I produce a lot of short work right now, and I’ve gotten to the point where my stuff doesn’t need a ton of massaging because I have a good sense of rhythm. Often, I’ll plunge into the middle of a story, then pin on the lede and kicker at the end so there’s a good progression. Since speed is so important in my profession (and to make sure I make a decent rate as a freelancer), I try not to get caught up in editorial crises of my own making. If it’s getting too complicated and I don’t have a sense of a piece’s structure, it’s time to get as simple as possible.

Kris: Getting into the nitty-gritty of that editing, talk to me about your process. What happens in the phase after you spit out that first draft? (As if it was only that easy, of course.)

Erin: For some reason, my angst and imposter syndrome like to rear their heads when I do longer work. My brain is always telling me that I’m not accomplished enough to take up that much space, or something. Blech. For that reason, I have to do what I call “the fun round” at the end of every long project. I go through and ruthlessly add fun—livelier words, shorter sentences, less repetition—so that I don’t bore myself and my readers to death with my fear-generated jargon. Cutting through that crap helps me confront the things I’m curious about head-on.

Kris: Are there any words or stylistic choices that you know you sometimes overuse?

Erin: Can you tell I’m into the em dash lately?

Kris: I’ve fallen off the em dash wagon many times myself. It’s such an easy punctuation mark, it can make for a slippery slope, really.

Last question for you: what do you wish a younger version of yourself knew about the process of editing a book or any other type of writing project?

Erin: You will not be the only person who touches your work, and that’s a good thing. I used to be so insecure and competitive, but I’ve come to realize that a really good edit is like someone making you a bespoke dress. It’s perfectly tailored, and you’re the one who gets to wear it, but you benefit from another person’s years of experience, too.

Earlier this year, I had a piece appear on the front page of The Washington Post‘s health section. Their copy desk is notoriously fastidious (as they should be!) and getting a thorough fact check and copy edit from them was nothing short of thrilling. The story was about a dearth of data, and they pushed hard to make sure that it was as accurately expressed as possible. It was such a relief to me—and where years ago those challenges to my work would have felt like a challenge to my validity as a person, this time around I realized how vital they were and how much better it made the piece. “Colleagues, not competitors” is a phrase I use as a reminder when I get insecure about those collaborations, and it’s served me well.

It’s the same thing with a book. Before being published, I had NO IDEA how much work from non-authors goes into creating a book, from the agency side to editing, copyediting, typesetting, design, sales, production, shipment, bookselling, and reading. So many hands touched my book before it hit readers’ shelves, and every single pair of hands made the book that much better. We all had the same goal, and the end process was something more meaningful than I could ever have done on my own.

Back in 2012, when I was lucky enough to meet Erin at the James River Writers Conference and have her sign my copy of The Heroine’s Bookshelf, she wrote, “To Kris, Be heroic!”

It’s what we love about our favorite protagonists; it’s what we should also love about our writing and editing process, isn’t it? Every time we jot down new words or strike through not-quite-right phrases, we’re taking our power into our own hands, getting ready to show the world our best. There’s certainly a type of heroism there too.

Thank you so much, Erin, and happy writing, writers!

Sign-up for my writing tips email newsletter for more interviews like this.

The post Authors on Editing: Interview with Erin Blakemore appeared first on Kris Spisak.

December 15, 2016

Writing Tip 199: “Per se” vs. “Per say”

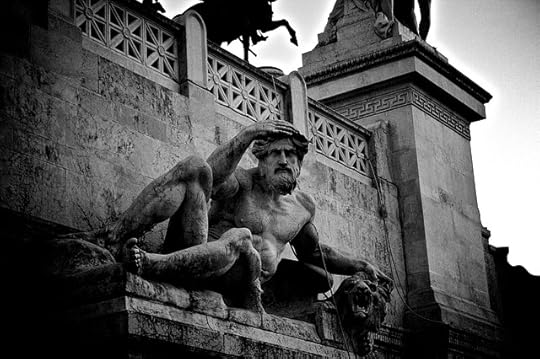

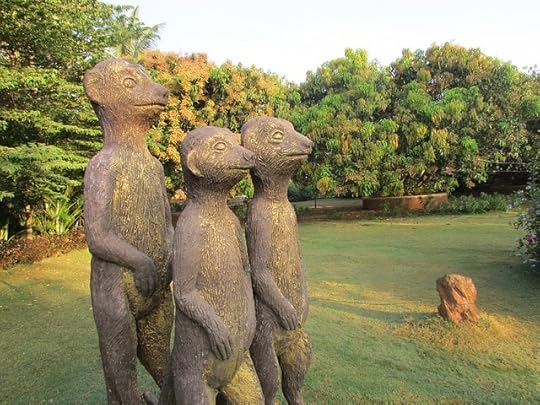

This statue probably won’t come alive and chase you down for your bad Latin spelling, but just in case, let’s work on getting “per se” vs. “per say” correct, everyone!

It’s not Latin itself that trips people up, per se, but it’s the spelling of the dead language. When interwoven with our everyday speech, Latin usage sometimes allows us to say our ideas in a more sophisticated tone, but this sophistication crumbles if we spell it “per say.”

Hear what I’m saying? Seriously, social media posters, do you? Think hard about “per se” vs. “per say.”

Remember, “per se” translates to “by itself” and means intrinsically or as such. This phrase is a quality insertion that can elevate your communication a notch, and being clever and educated is often a valuable stylistic choice. Ipso facto, don’t let a typo be your downfall.

Mea culpa if I’m pushing too hard here, but it’s the little things that we have to pay attention to. Making sure you know the right answer is just my modus operandi.

Carpe diem, and happy writing!

The post Writing Tip 199: “Per se” vs. “Per say” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

December 10, 2016

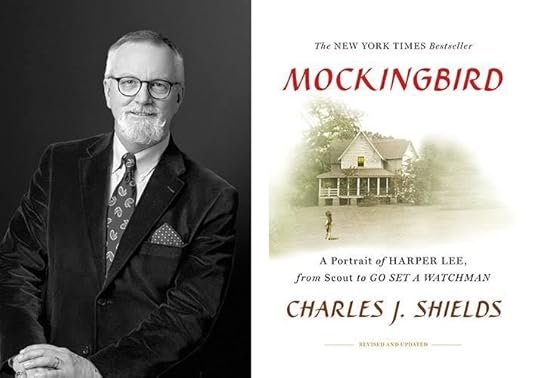

Authors on Editing: Interview with Charles J. Shields

When you have a moment to chat with an incredibly talented writer with a number of award-winning and ground-breaking books to his name, there are so many topics you could discuss, but as I’m one for digging in the weeds, seeing what I overturn, and getting my fingernails dirty (with largely digital ink), my direction was fairly clear.

I am honored to have Charles J. Shields join me to kick off my series of “Authors on Editing,” as we count-down to the release of my book, Get a Grip on Your Grammar: 250 Writing and Editing Reminders for the Curious or Confused in April of 2017.

Charles J. Shields is an American biographer of Mid-Century American novelists. His first biography for adults, Mockingbird: A Portrait of Harper Lee (Holt, 2006) become a New York Times bestseller and his young adult version, I Am Scout: The Biography of Harper Lee, received awards including being named among the American Library Association’s Best Books for Young Adults, Bank Street Best Children’s Book of the Year, and Arizona Grand Canyon Young Readers Master List. In 2011, Shields published the first biography of Kurt Vonnegut, And So It Goes: Kurt Vonnegut, A Life (Holt), which was selected as a New York Times Notable Book and Washington Post Notable Nonfiction Book for 2011. His most recent book, which is only available in Europe, is The Man Who Wrote the Perfect Novel: A Life of John Williams, focusing on the author of Stoner. Charles J. Shields resides in Charlottesville, Virginia with his wife, Guadalupe.

Q & A with Biographer Charles J. Shields

Kris: What does a biographer have to worry about in his or her final editing stages that other writers might not have to think about?

Charles: Well, I borrow from fiction to create structure and character, so my concerns are the same as a novelist’s or short story writer’s. I’d like to be able to give a more detailed answer, but I don’t get edited—barely at all. I wrote twenty books for young adults, all nonfiction, and none of them came back edited. My first editor was my father, a journalist. He edited my school papers the way he would a news or feature story, while I sat beside him. What that was like I describe in “The Editor at the Breakfast Table.”

Kris: Do you edit as you write or do you plow forward at full steam, letting words and punctuation fall where they may?

Charles: I write from an outline as quickly as I can. I try not to go back and revise right away. It’s better for me if I wait a few days and reread, then I see immediately what needs to be revised. Every time I begin writing a new project, at first it seems that the writing comes easily and reads well. After about two weeks, I realize my first draft has no style, no voice. It’s just pleasant talking on the page.

A good writing tip for any writer.

Kris: So what is your process for elevating that style and fine-tuning your voice?

Charles: Clear sentences can be found in how-to books, instruction manuals, and anniversary cards. But to make the reader believe that you, the writer, are speaking, the prose has to come as close as possible to conversation with the reader subconsciously filling-in the responses: “Oh no… really?… well, that’s typical.” The tone of the writing can be eloquent, or urgent, or anything else. But to have style, it has to sound like you are telling a story and drawing in the reader.

Something I dislike about much contemporary fiction, incidentally, is that it’s heavily expository and doesn’t allow the reader room to enter. The method seems to be “sit still and listen— after all, I’m the writer. You should be paying as much attention to me as the story.” I think this approach comes out of MFA-land.

Kris: Speaking of pet peeves in writing, do you have any others concerning grammar or word choice?

Charles: I don’t like to see slang and idioms in print: it’s lazy, and in twenty years, those phrases will sound as dated as “no way, “lame,” or “I’m like….”

Kris: Are there any words you know you overuse or other writing weaknesses of your own that you always pay special attention to in your final editing stages?

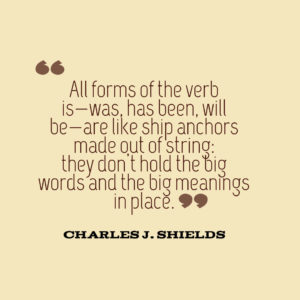

Charles: All forms of the verb is—was, has been, will be—are like ship anchors made out of string: they don’t hold the big words and the big meanings in place.

Kris: How do you know your editing process is finished and the book you’re working on is officially “done”?

Charles: The research is finished when I can’t find anything fresh. The revising and editing is finished when whole chapters scan well—smooth transitions, solid paragraphs, and a sense of immediacy as if events are happening at that moment. Of course, later when I open one of my books to a particular page, I might wince at how I expressed something, so I don’t read my work after it’s published.

Kris: Some writers’ favorite part is the research; others love the drafting and crafting; others love the later editing stages. What is your favorite part of writing a book and why?

Charles: I enjoy the research; the writing is murder. Research is like being a detective, and the discoveries are exciting.

“The writing is murder,” he says. I know a lot of writers can feel this way. I certainly have. I don’t know if it’s refreshing or terrifying hearing this from someone with as many great projects behind them as Charles J. Shields. I’m going to go with inspiring, though.

The writing is always hard. The editing is always a meticulous process. But in the end, look at the amazing stories that can be brought out into the world. Yours might not have two thousand footnotes like Shields’s biography of Vonnegut—yes, that number was written accurately—but whatever endeavor you set yourself upon, the struggle might just be worth it.

Thank you to Charles for your time, and happy writing, writers!

Sign-up for my writing tips email newsletter for more interviews like this.

The post Authors on Editing: Interview with Charles J. Shields appeared first on Kris Spisak.

December 8, 2016

Writing Tip 198: “Flu” vs. “Flue” vs. “Flew”

Historically, the word “flue” referred to the chimney itself, but either way, this one’s just asking for trouble. I bet plenty of birds flew in there! Oh, I think I’m feeling sick…

Before you start any fires in your fireplace, make sure the flue is open. Fingers crossed, no bird flew into your chimney and made a nest there. That would sure as heck freak me out—not to mention perhaps bring up concerns of avian flu.

My bird phobias aside—they are fierce little dinosaurs, aren’t they?—please make sure you’re not confusing “flu” vs. “flue” vs. “flew.”

“Flue” is the sickness, an abbreviated form of influenza.

“Flue” is the opening in a chimney that allows the smoke and fumes to escape.

“Flew” is the past tense of “fly.”

Maybe you’ve heard of “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” but here’s hoping a bemused cuckoo isn’t in your flue. Or that the cuckoo didn’t give you the flu. Or that it didn’t peck at you. Yikes.

Watch your spelling carefully, folks!

The post Writing Tip 198: “Flu” vs. “Flue” vs. “Flew” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

December 6, 2016

Editing Rudolph

Every year at Christmas time, I find myself wanting to edit a few famous lyrics.

Every year at Christmas time, I find myself wanting to edit a few famous lyrics.

Because, come on, folks, if you know “Dasher and Dancer and Prancer and Vixen

Comet and Cupid and Donner and Blitzen,” and then you’re asked about this other reindeer you may or may not recall, that doesn’t scream famous for that other guy, does it?

I love Rudolph. I love Hermey the elf dentist and the bouncing bumble, and I especially love when this maybe famous, maybe not little reindeer takes his first flight while yelling, “She said I’m cuuuuuuuuute.” But I think there is a logical issue with the start of this holiday favorite.

If we know everyone’s name except for Rudolph’s, he’s clearly not the most famous of the herd.

Some editors have pet peeves with “flair” vs. “flare,” “dragged” vs. “drug,” or “phrase” vs. “faze” (and I can be one of them), but song lyrics really get me sometimes. I’m no Scrooge with a red pen in my hands—I still sing along—but my holiday spirit falls just a notch.

There are others that get me too.

If Wham! sings that “last year I gave you my heart” and that he is giving it to someone special this year, I feel bad for that someone special. Why isn’t that someone special getting a song rather than last year’s fling? That kind of tells me that last year’s fling is still more special—if there even is someone new that’s special this year. Or is that it? It’s all a ruse? Taylor Swift, your version of this is out now. I expect better things from you.

I could go on, but I won’t. There’s communicating with respect and then there’s just being logical. Aim for both, and let’s try to hold our music to the same standards.

Happy holidays, everyone!

The post Editing Rudolph appeared first on Kris Spisak.

November 29, 2016

Writing Tip 197: What is the Plural of “Mongoose”?

When Riki Tikki Tavi gets together with his friends, collectively, what are these little guys called?

When the conversation drifts from wild chickens in Kauai to the mongoose population across the Hawaiian islands, one question comes up every time. Actually, a lot of questions come up every time—ranging from reckless introductions of invasive species to the potential collection of wild chicken eggs—but most importantly for our discussion is the question of the word “mongoose.” When you have one, we have no doubt about the singular form, but…

What is the plural of “mongoose”?

I don’t know about your conversations over dinner, but this was one of mine recently. I got a special enjoyment out of the question when every head at the table looked at me.

Not being a specialist in mongooses (or was it mongeese? what about monganders?), I did some research.

Most dictionaries consider “mongooses” the proper form, while a rare few will accept “mongeese” as an acceptable alternative. I think that might be a matter of so many mistakes finally being accepted as the norm, though, since “goose” and “mongoose” derive from different roots. “Goose” comes from Old English gos, which most likely derives from the Proto-Germanic gans. Alternatively, “mongoose” derives from the Hindi and Marathi word maṅgūs.

To conclude, I recommend you use “mongooses” as the plural form of “mongoose.” It seems to be the correct word. I’ll be sure to let all the company at my dinner table know, and you can help me spread the word too.

Knowing answers can be satisfying, but I can feel the rumbles of discontent from all those who felt sure “mongeese” was the correct answer. Interestingly, there was a petition sent to the UK Parliament on the matter in recent years, where a group was attempting to change the plural form of “mongoose” to “mongi.” The petition was rejected in the end, though, as spelling was considered an issue outside the role of British government.

Have your dinnertime conversations prompted any interesting discussions lately?

Sign-up for my writing tips email newsletter for more tips like these.

The post Writing Tip 197: What is the Plural of “Mongoose”? appeared first on Kris Spisak.

November 28, 2016

The Origin of “Knuckling Down”

Did you know that the phrase “knuckling down” derives from the game of marbles where players who focused on putting their knuckles down would be able to produce the best shots? You see, they had to choose their shooter marble, which was most likely a marble bigger than all the others, and then proceed to knock the other marbles out of the ring. That’s roughly the end of my knowledge of the game, but I suddenly want to find someone who can teach me. (There’s not an app for that, or if there is, I’m sure it doesn’t do the schoolyard practice justice.)

Did you know that the phrase “knuckling down” derives from the game of marbles where players who focused on putting their knuckles down would be able to produce the best shots? You see, they had to choose their shooter marble, which was most likely a marble bigger than all the others, and then proceed to knock the other marbles out of the ring. That’s roughly the end of my knowledge of the game, but I suddenly want to find someone who can teach me. (There’s not an app for that, or if there is, I’m sure it doesn’t do the schoolyard practice justice.)

Kids don’t play marbles much these days—I don’t know why it fell out of fashion—but we all should continue to knuckle down, shouldn’t we?

Of course, now the expression is less about tiny balls of beautiful glass and more about the idea of applying oneself determinedly to a task. Knuckling down is always good advice, whether it’s in the pursuit of a passion, in an effort to meet a personal or professional goal, or simply to show off your marbles prowess.

Our knuckles might not be pressed against the schoolyard sidewalk, but getting ourselves in a position to make an impact is good advice for anyone, I’d say.

I have my causes. My guess is that you do too.

Sign-up for my writing tips email newsletter for more tips like these.

The post The Origin of “Knuckling Down” appeared first on Kris Spisak.