Kris Spisak's Blog, page 30

February 9, 2017

Writing Tip 207: “Business” vs. “Busyness”

You can refer to a bee’s busyness, but if you’re referring to its business, that doesn’t quite make sense—unless it’s an entrepreneurial bee, making the most of its local honey, of course.

I don’t want to get all up in your business, but no matter how busy you are, make sure you know the difference between “business” vs. “busyness.”

I see the logic of this typo. After all, when you’re talking about the state of being happy, the word is “happiness”; when you mention how someone is savvy, you talk about their “savviness”; when you refer to how something is silly, you mention its “silliness.”

This “-y” to “-iness” transformation is a natural part of our everyday spelling.

The problem is that “business” is already a word.

Therefore, the correct word to use when thinking about the busy nature of your day-to-day is “busyness.”

Side note: When did it become so common for the response to “How are you?” to be “Busy”?

I’ll momentarily forgive the adjective vs. adverb slip, considering a “how” question should be answered with an adverb, but why is this the answer we all give and hear so often? A while back, I made a resolution to stop answering this way myself, not because I wasn’t busy, but because it doesn’t really answer the question, does it? Whether you’re busy or not, you could be doing wonderfully or terribly, after all. The “busy” answer has a variety of meanings too, from stressed to overjoyed, so why don’t we start answering this question a bit more precisely? We’re all busy.

Just a thought. You know editors always have side thoughts on everyday language use…

In the end, though, I hope all is well with you amidst your busyness, whether it’s busyness with your business or otherwise.

Happy writing!

Sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more writing tips like this.

The post Writing Tip 207: “Business” vs. “Busyness” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

February 7, 2017

Trivia: The Evolved Meaning of “Girl”

Originally spelled “gurle” or “girle” in Middle English, this word meant a young boy or a young girl back in the 14th century when it first originated.

You didn’t see that coming, did you?

Sign-up for my writing tips email newsletter for more word trivia like this.

The post Trivia: The Evolved Meaning of “Girl” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

February 4, 2017

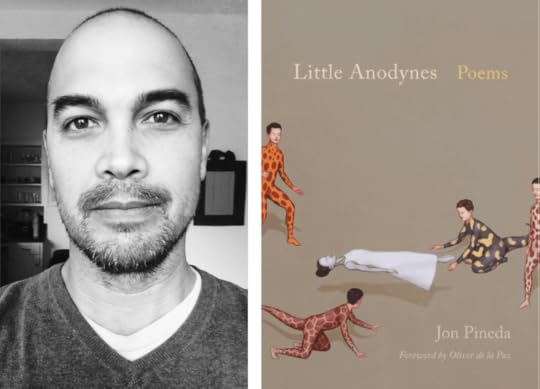

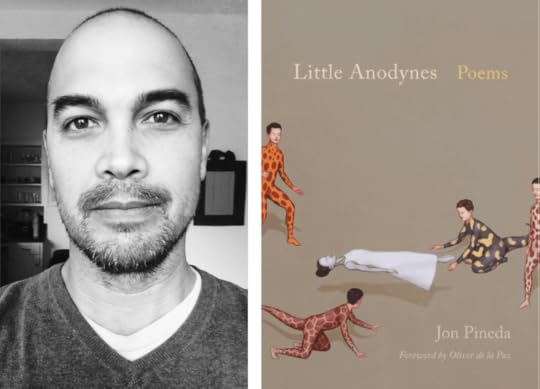

Authors on Editing: Interview with Jon Pineda

So many of us dream of being poets. The dream starves a bit amidst tiresome email correspondences or other words in our daily lives thrown down quickly and without much introspection, with no intention more than making a point as simply as possible—though, perhaps “simple” is the wrong word to contrast with a poem. Perhaps the opposite of poetry is plainness.

There is a time to be plain, but there is also a time to be astonishing. That’s why I’m thrilled that the talented poet Jon Pineda joined me to chat about his editing process.

Jon Pineda is the author of the memoir Sleep in Me, a Barnes and Noble Discover Great New Writers selection, the novel Apology, winner of the Milkweed National Fiction Prize, and the poetry collections Little Anodynes, winner of the Library of Virginia Literary Award for Poetry, The Translator’s Diary, winner of the Green Rose Prize, and Birthmark, winner of the Crab Orchard Award Series in Poetry Open Competition. He teaches in the low-residency MFA program at Queens University of Charlotte and at the University of Mary Washington.

Q & A with Author and Poet Jon Pineda

Kris: When you are revising a newly drafted poem, what is your process?

Jon: I like to read it aloud a number of times (when no one’s around, of course). Sometimes I’ll even just whisper it to myself, to see if the poem eventually wants to be in a different form. Sometimes the lineation changes considerably during this process.

Kris: Is this spoken aloud process where you edit rhythm? How can you be sure that you have it right?

Jon: I revise until the version I’m reading/hearing feels necessary, almost as if I couldn’t imagine experiencing it any other way. I keep going until the current rhythm has earned its place, in my mind. It might be right, or it might be wrong.

Kris: Speaking of right and wrong, sometimes finding the right word can be so hard. What is your advice to other writers for finding the perfect fit?

Jon: “Finding the right word” is something I often struggle with, and since I know that for me it’s sometimes an obstacle, especially in the generative stage, I’ll just put a line/”blank” wherever that spot happens to be in my journal, as a marker to go back to later. I find it’s more important to live in the momentum of drafting a poem. Let the images collide. Let the “half-meanings” do what they will. I’ll return to “finding the right word” on subsequent passes through the poem. I usually save those obstacles for revision.

Jon: “Finding the right word” is something I often struggle with, and since I know that for me it’s sometimes an obstacle, especially in the generative stage, I’ll just put a line/”blank” wherever that spot happens to be in my journal, as a marker to go back to later. I find it’s more important to live in the momentum of drafting a poem. Let the images collide. Let the “half-meanings” do what they will. I’ll return to “finding the right word” on subsequent passes through the poem. I usually save those obstacles for revision.

Kris: How true are you to the rules of punctuation within your poetry? Why do they or don’t they matter to you?

Jon: I try to use the punctuation as visual cues, but sometimes I don’t use punctuation at all. It depends on the moment I’m trying to offer up to the reader.

Kris: I like that concept of a moment that you’re “trying to offer up to the reader.” It’s not a matter of pushing a point too forcefully. A powerful poem evokes emotions and themes rather than explicitly stating a point, after all. This is something I’ve found newer poets sometimes struggle with. How are you sure that you’re never preaching on a subject?

Jon: I like what the poet Richard Hugo states in his famous essay “The Triggering Town”: “Once language exists only to convey information, it is dying.”

That’s such a powerful line, and one I hadn’t heard before. Language can be so much more than a means of conveying information. Yes, it is this, but it is so much more. That’s why we write, isn’t it? That’s why we edit the heck out of things until they polish and shine.

We may not all be poets, but we should tap into our poetic sides from time to time. When we finding right word, the right image, the right rhythm, our thoughtful language can reimagine and revitalize the world around us. At minimum, we can write the occasional awesome email that the receiving party never saw coming. At maximum, who knows…

Thank you so much, Jon Pineda, for taking the time to talk about your editing process, and happy writing, everyone!

Sign-up for my writing tips email newsletter for more interviews like this.

The post Authors on Editing: Interview with Jon Pineda appeared first on Kris Spisak.

February 2, 2017

Writing Tip 206: “Nip it in the…”

Yes, the correct phrase is “nip it in the bud,” but don’t nip this one. It’s too lovely. Okay? Thanks.

Something we really need to nip in the bud is the typo “nip in the butt.” I promise you, that’s not the correct version of this idiom.

This expression goes back to gardening. If you’re trimming back something problematic, you nip it in the bud, removing the buds before they grew into something bigger, wilder, havoc-wreaking, and generally other than what you wanted.

Are your roses getting out of hand? Are your strawberries taking over the rest of the garden? Is that Virginia Creeper strangling the life out of everything?

You know what you need to do about that? Nip it in the bud.

The phrase “nip it in the bud” as we know it today, meaning to stop something before it grows into a bigger problem, has been used since at least the early 1600s. I don’t know when the confusion set in, but it certainly has. You’ll commonly find this phrase written as “nix it in the bud” and “nix it in the butt,” as well as the ever popular “nip it in the butt,” but none of these are the correct form.

We’re not talking anatomy. We’re talking flowers, folks. Let’s take the time to get this one right.

Sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more writing tips like this.

The post Writing Tip 206: “Nip it in the…” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

January 30, 2017

Trivia: The Most Used Word in Conversation

Perhaps we could all take this as a challenge to do better?

The post Trivia: The Most Used Word in Conversation appeared first on Kris Spisak.

January 28, 2017

Authors on Editing: Interview with Pete Mosley

When I have the chance to trade letters—okay, fine emails—with writers from around the globe, I’m always fascinated by the tiny differences in communications, and I’m always inspired to remember that no matter where we are, the writing craft presents the same challenges to each of us.

Pete Mosley, a true professional who knows he’s writing to a largely American audience, didn’t let any of his Scottish turns of phrase trickle out into his answers of my questions, but the editor in me did have fun pausing at his placement of punctuation outside quotation marks, a rule that differs depending on what side of the Atlantic one calls home. (Though admittedly, his original usage—changed below—is the more logical form.)

A freelancer for over 30 years, Pete Mosley writes, speaks, and delivers workshops around doing business creatively, how to find and build relationships with customers, and how to tell a great story about your work—drawing on his wide-ranging experience of working in the space where creativity, business, and personal development meet. His first book, Make Your Creativity Pay, was published in July 2011, and his second, The Art of Shouting Quietly: a Guide to Self-promotion for Introverts and Other Quiet Souls, was published April 2015. Pete is the lead business trainer on Crafts Council UK’s prestigious Hothouse & Injection programmes, delivering business development sessions across the UK; he is Business Editor of craft&design magazine, and a regular contributor to The Design Trust UK webinars and Cape Craft & Design magazine (Cape Town, South Africa) website, among many other pursuits.

Pete is kindly offering a free giveaway of his ebook, The Art of Shouting Quietly, to readers of this blog, so I encourage all of you to take advantage of his generosity!

Q & A with Business Coach and Writer Pete Mosley

Kris: Does writing for audiences of different nationalities impact your editing process?

Pete: Yes! I’ve found it matters a lot. Being Scottish, a lot of my natural choice of words and dialect simply don’t connect with some international audiences. Also, as an introvert, my work connects more to cultures where introversion and quietness prevail.

Kris: That’s fascinating. I know that you do a lot of work with business professionals. What is your favorite tip to give leaders looking to make the most of their communications?

Pete: That’s easy—speak less, listen more.

Kris: There’s certainly an art to being succinct, and you managed it even in your answer!

Pete: Finding one’s comfort level with writing sometimes takes time, but once a writer has committed their ideas to the page, how would you recommend that they revise themselves to make the most of their own creative voice?

Pete: I record a lot of my material for audiobooks and podcasts. I find listening rather than reading often gives me a different perspective. It’s very valuable to me to listen back.

Kris: Speaking written words aloud does allow for your ear to catch the rhythm that’s off or the lack of clarity that you’re your eyes might miss. That’s great advice. There are so many details that writers focus on in the editing stage of a project. Which is the most interesting for you? Or which is the most painful?

Pete: The first stage is often the most interesting to me. I tend not to start at the beginning. I collect ideas and assemble them. The sequencing of material I find to be really fascinating. I often go through lots of revisions before I’m happy that the flow is right.

Kris: Absolutely. There’s a difference between a killer concept and a killer execution of that concept. When you have your first draft of a project written, what comes next?

Pete: Over the years, I have built up a group of people that I call “critical friends.” They get to see my first drafts and comment upon them. The addition of this stage is the most useful thing I have ever done to ensure my material connects with the audience, and I benefit from the honest feedback I get. I then re-write and pass to my editor.

Kris: Oh, I know those critical friends are important. I have a few of my own. I’ll have to tell them of their new title!

And speaking of titles, I love both the title of your most recent book, “The Art of Shouting Quietly,” as well as your subtitle, “A Guide to Self-Promotion for Introverts and Other Quiet Souls.” Titles are so hard sometimes. How do you finesse a title—be it of a book or a magazine article—to make the most of every word?

Pete: Again, I test book titles thoroughly with a sample of my readership. With blog articles, I tend to test variations on Twitter and use the analytics to see which gets the best response. In the case of magazine articles, I discuss options with the journalist or editor in question.

Kris: Writers don’t always think about analytics. That’s a great system. Since you do take on different types of writing, how is editing an article different from editing a book? Is either more intimidating to you?

Pete: I edit my own articles. I employ others to edit my books. I find the latter a lot more painful as I sometimes have to let go of ideas or figures of speech that I like, but are actually inappropriate for the context.

Kris: Right. That classic “kill your darlings” advice really applies to every genre and style of writing! Knowing your audience is obviously an essential part of any writing project, how do you keep this in mind with your final revisions?

Pete: Once more, my critical friends come into play. When a book is at its final stage, I send it out to key people to gather final layers of feedback—and to gather the comments that will be incorporated on the covers of the book.

Kris: Do you have any writing pet peeves that you often catch in other people’s work?

Pete: Over-intellectualization for the sake of it. I like ideas presented simply and without embellishment.

Kris: And one last question for you: what is your favorite word, and why?

Pete: Discombobulation. I often feel that way!

What writer doesn’t feel that way between all the pieces of the puzzle that we juggle? The research, the structure, the opening, the voice, the fine-tuning, the proofreading, not to mention the publication journey—yes, “discombobulation” is a fine word. I like that choice.

Thank you again, Pete Mosley, for taking the time to chat about your creative process with me and for so many great pieces of advice. Happy writing everyone!

Sign-up for my writing tips email newsletter for more interviews like this.

The post Authors on Editing: Interview with Pete Mosley appeared first on Kris Spisak.

January 26, 2017

Writing Tip 205: “Access” vs. “Assess”

A bridge to Grammartopia?

When you want to assess who has access to something, your spelling matters, doesn’t it?

Oh, there are so many directions I could take this conversation, but I’m going to keep it incredibly simple.

Remember:

“Access” means the permission or liberty to approach something or someone.

“Assess” means to determine the rate or value of something.

Yes, there are more subtleties to these words, but for our purposes, these definitions will do.

Interestingly, the word “access” stems from the Old French word acces, which in the 14th century meant an attack or onslaught, most commonly referring to the coming of an illness. This was related to the Latin form accessus, meaning an approach or an entrance. It wasn’t until the 16th century that “access” became the English word defined how we understand it today.

“Assess,” on the other hand, was strictly related to taxes from its origin in Medieval Latin, assessare, meaning to fix a tax upon, up until the 20th century. This meaning still holds, of course, but it also gained its new meaning of judging a person, value, or idea starting in roughly the 1930s.

Tax money, illnesses, and onslaughts—oh what a jolly little pair these two are. But whether you’re one who is making assessments or being assessed, whether you’re giving access or receiving it (or not), knowing the difference matters. That much, I think we can all agree on.

Sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more writing tips like this.

The post Writing Tip 205: “Access” vs. “Assess” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

January 23, 2017

Trivia: “Strengths”

“Strengths.” It’s a good word to think about. We all have a lot of strengths. Together, we can have even more.

The post Trivia: “Strengths” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

January 21, 2017

Authors on Editing: Interview with Patricia A. Smith

Writers and non-writers alike are sometimes baffled at how long it takes to write a book. To write well, an author needs to do justice to the story that he or she feels driven to tell—and it’s not just the crafting of the first draft. There’s also the editing of hundreds of pages, making sure the characters are true to themselves, that every scene truly drives the story forward in some way, that every line stays true to the tone of the project, and so much more.

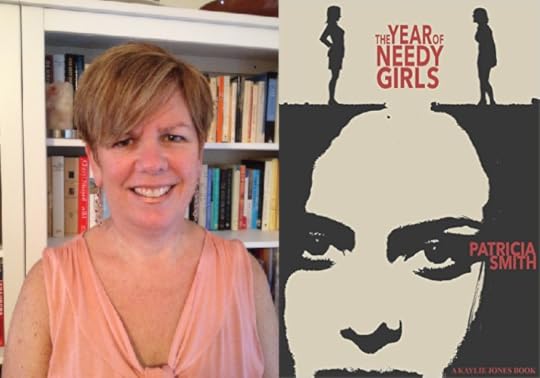

That’s why I always feel exceptionally excited when a talented writer, who’s been working hard for years, experiences the success of their first book publication. And Patricia A. Smith, who was kind enough to chat with me about her editing process, is that author who is finally seeing the fruits of her labors.

Patricia A. Smith received her MFA from Virginia Commonwealth University. Her nonfiction has appeared in the anthologies One Teacher in Ten: Gay and Lesbian Educators Tell Their Stories; Tied in Knots: Funny Stories from the Wedding Day; Something to Declare: Good Lesbian Travel Writing, and One Teacher in Ten in the New Millennium: LGBT Teachers Discuss What Has Gotten Better…and What Hasn’t. Her work has also appeared in such places as Salon, Broad Street, Prime Number, Gris-Gris, The Tusculum Review, and So to Speak. The Year of Needy Girls is her first novel.

Q & A with novelist and writing teacher Patricia A. Smith

Kris: What was the greatest lesson about editing that you learned through the process of writing and publishing The Year of Needy Girls?

Patricia: I think my greatest lesson is a truism that all budding writers hear over and over, but it finally became true for me in a concrete way—that less is more. Some readers might find that funny after reading my book, but truthfully, so much of my editing was cutting. I cut entire chapters. Fearful to do it, but trusting my editorial advice, I was surprised to see just how much stronger the narrative became when I cut away the inessential.

Kris: When you worked on your first draft of The Year of Needy Girls, did you try to commit the whole story to paper first, or did you edit as you went along?

Patricia: I wrote this book over a very long period of time, and I think if I had committed to getting the whole story down at once, I might have written it more quickly. Previously, I had written short stories and essays, and those I edit as I go along. But with a novel, it’s important to get down the whole arc of the story before you do too much close editing. Of course, the other reason I took so long to write this book is that I also teach full-time, and for a couple of years, I wrote only in the summers when I committed to going away on writing retreats. Thankfully, a couple years ago, I realized that if I wanted to finish this book, I had to make a more regular writing routine and committed to writing for an hour in the mornings before school and plowing ahead with the manuscript without editing. Instead of going back to change things, as hard as it was, I kept going and relied on my notes about what to change.

Kris: Did you have phases of revising, focusing on different aspects of your story, or did you tackle comprehensive edits all at once?

Patricia: Before I sent my book to Kaylie Jones, at Kaylie Jones Books, I tended to tackle comprehensive edits all at once, and I moved chronologically through the book. After I received editorial feedback, I revised and edited with more singular focus. For example, early feedback from Kaylie suggested (and she was right), that I take out one character who was diluting the focus of the narrative. So, I went through the entire manuscript to remove all the mentions and scenes—some of which had to be changed completely—with that character. Another concern was specific references to time, so I went through the manuscript with an eye for those details. I approached each editorial suggestion in that way.

Kris: Wow, I know deleting an entire character was a difficult process. Creating complex characters that are at once flawed and fully relate-able seems to be a specialty of yours. How do you make sure each individual is fully fleshed out and alive on the page?

Patricia: Character is one of my main concerns both as a writer and reader, so I am particularly interested in creating believable and complex characters. I was especially happy when an early reader told me that Mickey—a character who commits a horrible crime—was like-able. Because even though he is guilty, he is still someone’s son and someone’s brother. I had to work to find that human side of him.

When I was doing research for the novel, I spent some time with a police detective, trying to figure out how Mickey might be caught. And one thing the detective asked stuck with me. She said, “Is Mickey close to his mother?” Well, to be honest, at that point, I hadn’t even considered Mickey beyond the fact that I knew he had committed this crime; I didn’t know if he was close to his mother or not! And I remember feeling overwhelmed, too, suddenly realizing how little I knew about my secondary characters. The detective went on to say that if Mickey was close to his mother—something police might discover from their canvassing once they suspected him of the crime—they might, for example, use a female detective to question him because his relationship with his mother would suggest to them that he’d respond better and more deferentially to a woman. That question got me thinking in a more complex way about Mickey and who he was beyond a criminal.

Stories are less interesting to me if one of the characters is 100% “bad”—because who is that, anyway? We all have the capacity for good and evil in us. People are rarely all bad or good. TV shows, unfortunately, don’t always follow this dictum, nor do all movies, and so if young writers are getting their story inspiration from TV and film, too often they are thinking in terms of heroes and villains. And just as “bad” people have their good sides, “good” people are also flawed.

Kris: That’s a wonderful note. And how an author describes the world around their characters can portray complexity too. How did you create, maintain, and edit yourself to carry an atmosphere of suspense and tension through your entire book?

Patricia: I kept a couple things in mind from the get-go. One, I’m a New Englander by birth and temperament. I grew up in Massachusetts. I knew I wanted to set the story there. And I wanted to set it in the fall for a couple of reasons—one, because fall in New England is glorious, and two, because for teachers, at least for me, fall is the start of a fresh, new year. I’m always optimistic in the fall, looking ahead to the start of a new school year with hopes and goals for how things will happen. So, it felt important to have Deirdre’s life fall apart in the fall and the actions of the story take place against the backdrop of a—mostly—lovely New England autumn. Of course, the gorgeous fall of striking color quickly morphs into the bleak fall of black and white and grey, too, just as Deirdre’s life changes in an instant. It is probably not a coincidence that I teach The Scarlet Letter every year, either.

In my Fiction classes, I do an exercise with my students that comes from John Gardner and his book The Art of Fiction . It’s probably one that is familiar to most writers. He asks us to imagine a man whose son has just been killed in a war. Describe a barn as seen by this man; do not mention his son, or war, or death. It’s an exercise designed to teach us how to use setting to convey emotion. It also asks us to really see through the eyes of this man, to imagine what the barn really looks like to him through his grief. It is one of the best exercises I do with my students every year. And while writing the book, I consciously tried to use the setting to help convey the atmosphere of the story, and I hoped it wasn’t too heavy-handed. The prologue, too, sets the overall scene for the entire story and revs up the tension right away. By going through the manuscript and dropping in references to the missing boy every so often, my intention was to keep reminding the reader of that earlier tension and infusing each scene with an uneasiness, no matter the general feel of what was actually happening. This was something I did in later drafts, though. Early on, I wasn’t as conscious of that while I was writing Deirdre’s and SJ’s separate storylines.

Kris: You have me wanting to be a student in your class! When you have young writers in your classroom, what is your favorite piece of advice to give them?

Patricia: I usually admonish them not to kill their protagonist! I also tell them that there is often more conflict at a typical dinner table than there is in a “big scene” with guns or other weapons. This, of course, is not my original idea. I use Janet Burroway’s excellent book Writing Fiction: a Guide to Narrative Craft , and I have found much of the advice in that book to be stellar. I tell them that all good stories are rooted in character, that you need to know much more than you realize about your characters, and that plot is really a matter of knowing characters deeply and figuring out what choices the characters would make and the consequences of those choices. I tell them that rooting their fiction in familiar experiences is helpful. By this I don’t mean they can’t write fantasy—they can—but if they want to write about spies and murderers, for example, that it’s tough to do without doing extensive research (the kind they are not yet prone to do), or without some knowledge of what they’re writing. Again, they tend to base their knowledge of such characters on TV or other visual media, and for that reason, they come off as rather one-dimensional.

Kris: What’s the biggest grammar lesson you find yourself emphasizing with your students?

Patricia: Each year, with every class, I have to explain verb tenses and how to manipulate verb tense for flashbacks—that if they’re writing a story in the present, the flashback is in past but if the narrative is written in the past, the flashback is in past perfect. Similarly, I have to explain that if they’re writing a story in the past, the future is expressed by “would.” Many of even my strongest writers struggle with verb tenses.

Finally, I’d like to put in a plug for diagramming sentences. I find my students, on the whole, don’t have a strong understanding of how sentences work, of where to put or how to make effective use of clauses.

Oh, diagramming sentences. It comes up again and again, doesn’t it? There are few who went through the process who remember it as any fun (I know I didn’t think it was!), but at the same time, there are few who went through it, who remain totally baffled on the elements of sentence structure. I’m of the school of thought that you have to know the rules of writing before you can break them—or redefine them. Is it possible to teach the subtleties in different ways? Probably. Finding out that answer is a bit of a mission of mine. But I digress…

Thank you so much, Patricia A. Smith, for taking the time to talk about the editing process of your first published book, and happy writing, everyone!

Sign-up for my writing tips email newsletter for more interviews like this.

The post Authors on Editing: Interview with Patricia A. Smith appeared first on Kris Spisak.

January 19, 2017

Writing Tip 204: “Biannual” vs. “Biennial” (& “Bimonthly” too!)

Before you schedule that bimonthly meeting, make sure everyone is on the same page.

Do you know the difference between “biannual” and “biennial”? Or is there a difference? And where does “semiannual” fit in? (Cue the Jeopardy music)

This is another one that trips up native speakers. A lot of folks don’t realize that “biannual” and “biennial” are two different words with two different meanings.

“Biannual” means happening two times a year. “Semiannual” actually means the same thing.

“Biennial,” on the other hand, has the same “bi” prefix, but means “once every two years.” It’s rare, but when someone is looking for the right word in this situation, “biannual” just won’t do. Precision and correct spelling are essential.

Some people like to keep it safe and avoid the “biannual” vs. “biennial” confusion by staying away from “biannual” all together. “Semiannual” will do just fine in its place in all cases.

The prefixes seem confusing, but don’t let them trip you up.

“Bi-” means two. Think “bicycle,” two wheels, and bipod, two legs.

“Semi-” on the other hand means “half.” Think “semi-circle,” half of a circle, or “semi-truck,” a truck whose trailer cannot move without the other half (the engine).

So “semi-annual” is twice a year, breaking the year into halves, and biennial is once every two years. The same logic follows for semi-weekly, twice a week, and bi-weekly, once every two weeks.

I knew one writer who kept this straight by remembering Victoria’s Secret has a semi-annual sale. What business would survive off a big sale every two years? Throw in supermodels in their underwear, and maybe Victoria’s Secret would do just fine, but that’s beside the point, right?

Writing Tip 204.1: “Bimonthly” is a little linguistic rebel with two definitions. It can mean either two times a month or once every two months. For example, I have a bimonthly writing and editing tips newsletter, that I email out once every two months, but maybe you receive a bimonthly update two times a month from your favorite online store. Both usages are correct.

“Bimonthly” is a bit tricky and a little bit annoying, but it is what it is. And these are the details we need to teach ourselves.

Happy writing, everyone!

Sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more writing tips like this.

The post Writing Tip 204: “Biannual” vs. “Biennial” (& “Bimonthly” too!) appeared first on Kris Spisak.