Kris Spisak's Blog, page 26

June 15, 2017

Writing Tip 223: “Short Shift” vs. “Short Shrift”

Have you ever been given short shrift? How about a short shift? It’s time to know the difference.

If you’re working nine to five, you don’t have a short shift. Depending on your job, you might feel like you’re often given short shrift, though.

If you go out shopping, maybe you could buy a short shift dress. You wouldn’t want to buy a short shrift dress, because one, it doesn’t sound like a power piece for your wardrobe, and two, I really don’t have a clue what that might look like. Maybe you could just blame that one on bad signage, I suppose. Someone should have done some editing.

Remember, if you’re looking for the phrase meaning ignored or given little consideration, “short shrift” is correct.

“Shrift” is an old word referring to confession that we don’t generally see anymore. The expression “short shrift” was used for the first time by Shakespeare in Richard III, and in this usage, it was referring to a literal brief confession. The metaphoric use that we’re familiar with today didn’t come until centuries later.

“Short shift” is a common enough typo, but it’s not one that you want to repeat or wear or print on any retail signage.

Be careful to avoid this misspelling, folks.

Join 550+ subscribers and sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more tips like this.

The post Writing Tip 223: “Short Shift” vs. “Short Shrift” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

June 10, 2017

Authors on Editing: Interview with David Kazzie

So many people say they’ve always wanted to write a book, but only a fraction of these people actually do so. The hard thing to discover is that after the passion and drive, the determination, the desperation, and the belief in your story, once you hit the last page, you aren’t actually close to being done.

It’s in the editing process that stories are spit-polished to a shine, and this week’s interview with author David Kazzie is packed with advice to bring out the best in your work.

David Kazzie lives in Virginia, where he works as a novelist and lawyer. His first novel, The Jackpot, was a No. 1 legal thriller on Amazon and was published in Bulgaria in April 2015. The Immune was published in serial format in January and February 2015. In May 2015, all four installments of his Immune series were ranked in the Top 10 on the Post-Apocalyptic genre bestseller list. Part I (Unraveling) was ranked No. 1 in Post-Apocalyptic, Dystopian, and Genetic Engineering and reached No. 31 in the Kindle store. The Living, a sequel to The Immune, was published in May 2017.

David is also the creator and writer of a series of short animated films that have nearly 3 million hits on YouTube and were featured on CNN, in the Huffington Post, the Washington Post, and the Wall Street Journal.

Q & A with Novelist David Kazzie

Kris: When you hear the word “editing,” what do you think?

David: I think, “Thank Sweet Baby Pokémon, I’ve finished the first draft!” It’s a good feeling knowing that you have something to edit. Just getting to the end of a full-length manuscript is a huge achievement, even if you know that there is as much work ahead of you, if not more, than there was behind you.

I write pretty rough first drafts, so while I can’t say I adore editing and want to marry it, I know that this is the stage where I can make the book the best it can be.

Kris: What does your editing process look like?

David: First, I put the manuscript away for several weeks, and I really try to not look at it in that time frame. This helps you come back to with fresh eyes—maybe not as objectively as a third party would—but you’ve created some distance that will help you see all the big-picture and little-picture issues you will need to address.

Second, I print it out and read it once all the way through as quickly as possible. This is when I work to identify any really glaring problems. Without fail, First-Draft Me has left some big messes for Current Me, and this is when I start identifying them, making a list of them, and formulating a plan on how to fix them.

Second, I print it out and read it once all the way through as quickly as possible. This is when I work to identify any really glaring problems. Without fail, First-Draft Me has left some big messes for Current Me, and this is when I start identifying them, making a list of them, and formulating a plan on how to fix them.

I’ve found—and this might be the most important thing I say in this interview—that this first read is the most important because the manuscript is still wet concrete—it hasn’t really started drying yet, and you’re more open to seeing problems and making big changes. After a second or third read, the manuscript will start to harden in your mind, and you’ll become more resistant to change. This is partly because after a couple reads, you will start to get sick of the book (I promise you will), and partly because it becomes more difficult to imagine the book in a different form. Your mind starts telling you that this is the book, this is the book, this is the book. Don’t be afraid to slash that draft to bits with a red pen—that’s a good way to remind yourself that the book is still under construction.

For example, the first draft of The Living came in at around 100,000 words. My first read revealed a number of really big problems that I had to address (in fact, they were so big, I briefly thought about chucking the manuscript entirely). I ended up cutting around 30,000 words and adding 45,000 new ones. If I hadn’t been willing to address the problems early on, they would’ve begun hardening and become more difficult to repair.

Then I start zeroing in on specific aspects—character, setting, story arcs, and so on.

Kris: After that first read, how do you approach your changes? Do you have stages of edits that focus on different aspects of your book?

David: I start with a wide-angle look at the book, mainly to make sure that the story holds together. When all is said and done, I’m trying to tell a good story that will have people turning the pages.

Then I try to focus on each main or major character and make sure that I have done as much justice as I can to that person’s story arc. The primary subplot of The Living is the main character’s relationship with her 11-year-old son and whether she’s done him a disservice by being very overprotective in the first decade of his life. I think every parent struggles with this.

I also had to be careful to look after the son’s story arc, as he changes a lot too—but this was tricky, because the book is told entirely from his mother’s point of view. It’s easy to give non-point-of-view characters short shrift, and I always want to develop the characters as fully as I can, even if the reader is never in their heads on the page.

I also had to be careful to look after the son’s story arc, as he changes a lot too—but this was tricky, because the book is told entirely from his mother’s point of view. It’s easy to give non-point-of-view characters short shrift, and I always want to develop the characters as fully as I can, even if the reader is never in their heads on the page.

Setting is another thing I try to focus on. The Living is set a dozen years after a viral apocalypse that decimated humanity, so I wanted to really build out this world and make it feel very real. A second draft is a good place to flesh that out (but on the flip side, you have to be careful not to let the setting overwhelm the story).

Kris: Which parts of the editing process are the most fun for you?

David: I always love being able to solve a problem that I’ve found or make improvements—filling a plot hole, adding depth to a character, figuring out how to better challenge your characters using their own flaws and insecurities against them, thinking of a better scene, even if conveying the same information—these all make the book better.

I enjoy seeing some of the themes that float up, especially ones that you were not cognizant of as you were pouring out that first draft. After a couple of reads, you’re like, “oh, so this is a thing that’s important to me.” Then you can focus on really putting a shine on those parts of the book.

I also like using the editing phase to add little details, maybe some foreshadowing or symbolism that make the story more interesting. For example, there’s a tiny bit of foreshadowing in the prologue that I really love (even though you’re never supposed to love anything you write) and I only figured out to add it in a subsequent draft.

The editing process also helped me come up with a much better ending for the story than the one that appeared in the first draft—particularly by being conscious of the character arcs.

Kris: Which parts of the editing process are the most painful?

David: When you realize something is significantly wrong with the book, a systemic problem that threatens everything. I wasn’t quite there with The Living, but I was close. I had to rip out a number of major scenes and start them from scratch. I probably had a dozen chapters that just sort of ended without any resolution to that chapter or any connection to the next one (or really any connection to anything at all). It took about four months to clean up. Plus with a revision that big, I basically had to look at the manuscript with the newly added 40,000-ish words as a first draft again.

This can be one of the biggest tests you face as a writer—knowing when you have to really get in there and gut the project, even if you don’t necessarily have to start over.

This can be one of the biggest tests you face as a writer—knowing when you have to really get in there and gut the project, even if you don’t necessarily have to start over.

I do have an old manuscript sitting on my hard drive—probably my most original and best story concept—that does need a complete re-write. I remember doing my first read-through of the first draft and this growing sense of dread, the certainty that the book was so flawed that I would need to go back to the drawing board. That was really painful.

I may be getting ready to go back and tackle that one—I like the story concept too much to give up on it.

Kris: And now I’m intrigued. I hope you do! What do you look for when you’re trying to shore up your plot? Could you speak to strong pacing and story structure?

David: I am a big believer in story structure, which I think does bear on pacing. As we all learned, the vast majority of books and movies adhere to the three-act structure, but that never really did anything for me until I learned how to break that down further and understand what each Act was supposed to contain.

For example, I now know that relatively early in the story, as early as page 1, but certainly no later than page 50, you need to introduce the Inciting Incident. Every writer probably has their own interpretation as to what this means, but for me, it’s the event or incident that changes the status quo of the main character’s life—even if the main character isn’t aware of it or is not inextricably tied to it yet. This will send the protagonist on a path that will intersect with the inciting incident in some way at or near the end of Act I. It’s this intersection that launches the primary conflict that will power the rest of the story. In a way, it’s the yin to the ending’s yang.

I also pay attention to the milestones that should fall around each quarter of the story, specifically, the First Plot Point (around the 25 percent mark), the Midpoint (this splits Act II into two more manageable sections), the Second Plot Point (75 percent mark). These really should be the most important turning points in the story, and simply by spacing them correctly, almost by default, you’ll bring a nice sense of pace to the book (regardless of whether your book spans one night or one century).

These are all things to look for in editing—by keeping an eye on structure, you can decide if things happen too soon or too late or what-have-you and adjust accordingly.

These are all things to look for in editing—by keeping an eye on structure, you can decide if things happen too soon or too late or what-have-you and adjust accordingly.

Kris: Do you use your original outline, character sketches, or pre-writing notes in your editing process?

David: Sure, these can all be helpful in keeping you close to your original vision (if that’s what you want); in the case of character sketches, they can be helpful in seeing how the character has changed once you’re three or four drafts in.

Kris: Do you have any advice about strengthening your characters to make sure they’re alive on the page?

David: This comes with practice and reading authors whose characters made an impression on you. When you first start writing (and this happened to me), there is a tendency to make your protagonists very heroic, almost to a fault. It can be very challenging emotionally to see your characters as flawed people who’ve made mistakes, have regrets, think less-than-pure or selfish thoughts, and make bad decisions that they know are bad—possibly because it makes you confront, or at least acknowledge, those flaws in yourself.

Kris: What do you wish you knew about revision a long time ago?

David: To use the “Track Changes” feature (I write and edit in Word, no clue if you can do this in Scrivener). It seems like a simple enough thing, but it’s really helpful to be able to see all the changes you’ve made over the course of multiple revisions. It took me like three manuscripts to remember to do this because I’m generally an idiot.

Kris: Aw. We all have things like that that we should have realized earlier. It was the power of using the “Find” and “Replace” functions that I wish I’d realized earlier.

Now, you’re a lawyer by day. You know every word matters. How do you keep this in mind as you edit?

David: Well, I think you try to make sure you don’t waste the reader’s time (much like a lawyer tries not to waste a judge’s or juror’s time in making an argument). I don’t think there’s any doubt that readers today are different than they were ten years ago because of the quick-hit nature of the Internet that we’ve all become addicted to. This doesn’t mean to dumb down your writing into click-bait or anything like that. But be conscious of the fact that many things are competing for your reader’s attention. Truthfully, that’s not really different from the advice of the past anyway—if something doesn’t HAVE to be in your book, it shouldn’t be. Every word and every sentence should have a mission.

I like ending on this note. Every word and every sentence should have a mission. Every piece of a story needs to fulfill a purpose that supports the end goal.

Every part of the writing process serves a higher purpose too, even if we each get there in a different manner. Through the brainstorms and drafting, revision and fine-tuning, we work and edit until the whole is everything it can be. We need to make sure we take the time to do it right, but I have faith, with the right effort, good stories can always get there.

Thank you so much for your thoughts, David Kazzie, and happy writing, folks!

Join 550+ subscribers and sign-up for my monthly email newsletter for more interviews like this.

The post Authors on Editing: Interview with David Kazzie appeared first on Kris Spisak.

June 8, 2017

Writing Tip 222: “Burned” vs. “Burnt”

I’m sure Smokey the Bear would have something to say about this. Or maybe even Rogue Smokey… that guy’s burns would spread like wildfire.

Some days are full of social media burns so severe people are looking for ointment. Other days, people are posting Pinterest fails of recipes gone wrong. But the word that comes up again and again is that “burn.”

Have you ever been “burned” by bad spelling? Ever been “burnt” by it? Is there a difference?

In truth, I could argue that the words are interchangeable—which to a degree they absolutely are—but, okay, fine, let’s talk less about what’s formally correct, and what’s most common in American English.

“Burned” is the most frequently used past tense of the verb “burn” for U.S. writers. “Burnt” is perfectly acceptable, but like barmy and axe, it’s just not the choice word on this side of the pond.

“Burnt” does have its time to shine for American writer and speakers, though—just not in a verb form. Think of burnt casseroles or burnt toast. This spelling is commonly used in adjective form. It’s also familiar in color names like “burnt sienna” and “burnt umber,” but those usages are adjectives after all.

This explanation might not help with any other burns online, but at least your spelling won’t be going up in smoke.

Join 550+ subscribers and sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more tips like this.

The post Writing Tip 222: “Burned” vs. “Burnt” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

June 6, 2017

Trivia: The origin of the word “Frisbee”

Once upon a time there was a company called the Frisbie Pie Co. in Connecticut, which was run by Mary Frisbie. While the bakery did not last, its pie tins did–though not in a way Ms. Frisbie might have been expecting.

Wham-O gave the name “Frisbee” to the famous toy in 1957, after earlier names including the Pluto Platter and Whirlo-Way didn’t quite catch on.

Consider this trivia for the next time you’re served pie.

Join 550+ subscribers and sign-up for my monthly email newsletter for more trivia like this.

The post Trivia: The origin of the word “Frisbee” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

June 3, 2017

Authors on Editing: Interview with Kristina Wright

The diversity of a single writer sometimes blows me away. Sometimes we have this idea that writers have a single genre that they write within, a genre in which they excel and that must be their favorite. And then you discover writers like Kristina Wright, accomplished erotica writer, romance writer, and mommy blogger.

Kristina Wright is a freelance writer and editor who lives in Virginia with her husband and their two sons. She has edited over a dozen erotic romance anthologies for Cleis Press, including the Best Erotic Romance series. Her own books have been published by Harlequin and HarperCollins and her short fiction has appeared dozens of print anthologies. She blogs on parenting topics for Mom.me and Café Mom and writes about books for BookBub. Her essays have appeared in publications as diverse as the Washington Post, Cosmopolitan, Role/Reboot, Good Housekeeping and Narratively. She holds degrees in English and Humanities from Charleston Southern University and Old Dominion University and has taught at the college level. She loves reading, traveling, and coffee.

Q & A with Erotica Writer and Parenting Blogger Kristina Wright

Kris: Before we dive into editing, what is your favorite part of the creative process?

Kristina: For me, there is nothing like creating something out of nothing, so I love the process of getting the story down. Just putting the story on the page—and hopefully coming close to how I imagine it in my brain—is the best feeling ever.

Kris: Do you edit as you write or do you plow forward at full steam, letting words and punctuation fall where they may?

Kris: Do you edit as you write or do you plow forward at full steam, letting words and punctuation fall where they may?

Kristina: If I’ve just started the piece, I’m usually anxious to get the bones down. I’ll pour it out, stream-of-consciousness style, until I’m comfortable in the groove, and then I’ll be more aware of editing as I go. But, especially for fiction, the early stages are a jumble of thoughts and snippets of dialogue here and there and notes on character. It takes me 20-30 pages to figure out where I’m going, and then I start cleaning up as I go.

Kris: Is your editing process different when you edit fiction verses when you edit a shorter essay or article?

Kristina: The shorter nonfiction pieces I do for parenting blogs (500-1000 words) are usually pretty well planned out by the time I start writing. The editing has to be tight—there’s a word count (and attention span) to be considered when you’re writing for a website. Often, I’m 100-200 words over my limit by the time I have a fairly clean draft. Then it’s a matter of going back and tightening—cutting out the adverbs, making sure I’m not repeating myself—and snipping those extra words. Often, those extra words will spin off into another piece. With fiction, I’m less concerned about word count than I am telling the story, so for me there’s more freedom to writing fiction.

Kris: Does this process differ depending on genre of fiction?

Kristina: I write romance, erotica, erotic romance, and romantic suspense, and, though they overlap in some regards, there are reader expectations in each subgenre. Keeping that in mind as I edit—what the reader expectation will be—helps the editing process. With fiction, I’m able to slip in and out of character, and there’s not the same sense of self-identity as there is with nonfiction. Personal essays and memoir, in particular, require a certain emotional vulnerability that means turning off the internal editor and just speaking truth. It’s harder, in many ways, than writing fiction.

Kris: I can completely understand that. Nonfiction requires a different voice and perspective, and when you’re writing about something as personal as parenting, which you do so openly, honestly, and refreshingly non-judgmentally, it takes this up another notch. Outside of thinking about shifts in voice between styles of writing, are there any word choices you wish more people understood?

Kristina: The one that I saw most as an editor of erotica anthologies is the misuse of the word “ravage” when the author meant “ravish.” It drives me crazy!

Kris: Ooh, I need to add that to my writing tips list. How have I not done that one yet? Thanks for the suggestion. Do you have any strong feelings about the Oxford comma?

Kristina: Hate it. Always have. It looks weird to me, stuck before the “and.” There are rare occasions where it might help clarify meaning, but reorganizing the sentence usually resolves it and makes the Oxford comma unnecessary. Having said that, I follow my various publishers’ style guides (and I grit my teeth while I do it).

Kristina: Hate it. Always have. It looks weird to me, stuck before the “and.” There are rare occasions where it might help clarify meaning, but reorganizing the sentence usually resolves it and makes the Oxford comma unnecessary. Having said that, I follow my various publishers’ style guides (and I grit my teeth while I do it).

Kris: I fear you’ll be gritting your teeth when reading the final version of this interview—my blog has always been an advocate for the Oxford comma—but this brings up another wonderful point on style. As much as some want it otherwise, there is no “right” or “wrong” when it comes to Oxford vs. Serial comma usage. It’s another one of those can’t-we-all-just-get-along conversations. Differences of opinion are okay. Not all grammar rules are black and white. I could keep going on this for another 1,000 words, but I’ll stop here. Last question for you: How do you know the story or article you’re working on is officially “done”?

Kristina: I’m never done. But the difference between being a writer and being a professional writer is getting paid for what I write, so at some point I have to let go of what I’m writing and send it out into the world. If I’m contracted and under deadline, letting go is a little easier. If I’m working on a submission to a new publication, I give myself a self-imposed deadline. I also have to trust that other sets of eyes will catch what I’ve missed.

One of my favorite quotes on the creative process comes from Leonardo da Vinci: “Art is never finished, only abandoned.” And it’s so true. Sometimes “finished” means that the deadline has arrived. Sometimes “finished” means beta reader concerns have been addressed. Sometimes “finished” means editing goals in Excel spreadsheets have been accomplished—no joke, we all work in different ways.

Writers have to be careful not to call a piece finished too soon lest a project is sent out to meet its fate before plot structure is perfected, characters are fully fleshed out, redundancies and repetitions have been tightened, or “onetime” vs. “one time” spelling blunders have been corrected. However, each piece needs its chance to meet the world.

I like ending on this note. No matter what we write, our ideas deserve their shot with an audience outside of ourselves.

Thank you so much, Kristina Wright, for taking the time to chat about your process, and happy writing, everyone!

Join 550+ subscribers and sign-up for my monthly email newsletter for more interviews like this.

The post Authors on Editing: Interview with Kristina Wright appeared first on Kris Spisak.

May 25, 2017

Writing Tip 221: “Toe the Line” vs. “Tow the Line”

Wondering if it’s “toe the line” vs. “tow the line”? Here’s your hint.

If this expression brings to mind a great heave-ho of a rope, you might be thinking about (and spelling) this expression incorrectly.

Reminder: The idiom meaning “to do what is expected” or “to follow the established rules” is correctly spelled “toe the line.”

It’s an expression that was once used at the start of a race, when runners were called to step into the ready position with their toes on the starting line. Imagine that moment after the stretches and warm up jogs, when racers are now instructed, “On your marks.”

By “toeing the line,” one would make sure be in position and not to move past a defined mark. This can mean the starting line of a race, a company practice, or a political party doctrine. To toe the line means to be where you need to be, to act as you need to act, according to a pre-defined standard.

There’s no “towing” or “hauling” involved.

Of course, before you toe any line, I’d recommend thinking hard about whether it’s a line that makes sense for you, your career, and your sense of integrity. If it does, awesome, step up to the mark. If it doesn’t, maybe you should rethink the race before you.

Join 550+ subscribers and sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more tips like this.

The post Writing Tip 221: “Toe the Line” vs. “Tow the Line” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

May 23, 2017

Trivia: the Holy Origin of “Cappuccino”

The origin of “cappuccino” goes back to the “cappuccio,” a pale brown hood worn by monks in Renaissance Italy. One order of monks took their name from this hood in the 16th century, becoming known as the Capuchin friars.

When the first cappuccino drinks came to be, it was named after these monks and their light brown hoods. The “-ino” ending was added to reference a “little” Capuchin monk. These monks dedicated themselves to helping the poor, the weak, and the needy. A good cappuccino in the morning seems like it serves a similar purpose, doesn’t it?

Join 550+ subscribers and sign-up for my monthly email newsletter for more trivia like this.

The post Trivia: the Holy Origin of “Cappuccino” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

May 20, 2017

Authors on Editing: Interview with Osita Iroegbu

Editing doesn’t just mean proper comma placement. Revision allows for a new examination of clarity, content, and a shift of perspective. Today’s interview with Osita Iroegbu dives into these complicated issues that are essential for every writer to consider to be true to their subject matter, thoughtful about the surrounding world, and to elevate the conversation at hand.

Editing doesn’t just mean proper comma placement. Revision allows for a new examination of clarity, content, and a shift of perspective. Today’s interview with Osita Iroegbu dives into these complicated issues that are essential for every writer to consider to be true to their subject matter, thoughtful about the surrounding world, and to elevate the conversation at hand.

Osita Iroegbu, a first generation Nigerian-American, is a community advocate, educator and communications professional. She previously worked at the Richmond Times-Dispatch newspaper as a general assignment reporter and at Legal Times weekly news magazine where she covered lobbying on Capitol Hill. She spent time as a public relations practitioner at Richmond Redevelopment and Housing Authority and Virginia State University where her work included speech writing, media relations, and community engagement. She also taught and co-instructed mass communication classes at Virginia State University and Virginia Commonwealth University. Osita, a Richmond native, is currently a PhD candidate in VCU’s Media, Art, and Text doctoral program where she researches the intersection of media, race/class/gender, health, and social justice. She is co-founder of the African Community Network, a nonprofit organization providing resources and services to African individuals and families in the Greater Metro Richmond area, and founder of the Little Princesses Mentoring Program, which links girls living in underserved communities with positive women in college. She occasionally writes editorial pieces for the Times-Dispatch as a guest columnist and has a newly-found affinity for Afrofuturistic literature and art.

Q & A with Community Advocate, Educator, and Communications Professional Osita Iroegbu

Kris: When you write, how important is your editing process?

Osita: The editing process is an essential part of good, effective writing. I actually edit along the way and don’t necessarily wait until the finished product. I like to re-read and review within the process of writing. At times, however, I do like to employ the stream-of-consciousness technique and write whatever is on my heart and spirit and then go back and tweak or fill in any visible gaps. The type of editing that takes place depends on the genre of writing. And it’s not just grammatical corrections I seek to make, although this is a very important part of the editing process, but I look for ways in which I can build greater context and connections with my audience in my writing, ensuring that my message is timely and speaks to the social and cultural issues confronting us. It’s really all about relationship building and using my writing in subversive, truth and justice-seeking ways. I try to make sure that I am using the best messaging that will help me to most effectively engage and build with my target audiences.

Kris: Is knowing your audience important in the editing stage?

Osita: It is critical to know the people with whom you want to connect before you even begin to write. As a journalist, I’d ask myself questions like, what do people want to know, why is this important, to whom and how? I’ve also engaged in lots of writing as a public relations practitioner. I’ve written speeches for university and non-profit executives and press releases for small to large organizations. For this type of writing, it’s important to craft the message in a way that effectively captures the voice and essence of the speaker and organization sending the message. At the same time, it is just as critical to write in ways that will be understood and felt by your particular audiences. Before and during the writing and editing process, identifying the function(s) of your writing is also essential. It’s important to ask yourself if the goal of your writing is to inform, persuade, motivate, or serve as a call to action (or a combination thereof). Either way, you want to ensure that your writing will have the intended impact on your targeted audience(s).

Kris: As a trained journalist, what is the most important lesson you learned about revising your first draft?

Osita: It’s crucial to ask yourself what you can do in a revised draft that would strengthen the effectiveness and purpose of your writing. Asking myself “why am I writing this?” helps to keep me focused and true to my goal. In journalism, I’ve also learned that accuracy is paramount. For example, ensuring that direct and paraphrased quotes are precise and true to form is a huge win not only for the writer and the person to whom the quote is attributed, but for your entire audience and thusly, society as a whole. Communicating accurate information is a reflection of truth and truth yields incredible power. We should always remember to intentionally utilize our writing to speak truth to power. This is also true of non-journalistic writing. Maya Angelou often talked about the life-giving power of literature. Poetry, works of fiction, and other genres can be used to accurately reflect and artistically address the social and historical issues of our time in very responsible and empowering ways.

Kris: How is editing academic writing different from editing a newspaper or journal article?

Osita: Academic writing is traditionally laden with explicit arguments and theories. Editing this type of writing can prove to be more technical than newspaper editing. Theoretical concepts and arguments can indeed be found in journalistic writing, including editorial pieces, but may be more implicit and can require an astute level of media literacy. The who, what, when, where, why, and how are the fundamental questions of newspaper/journalism writing that the editing process must make clear. The editing of academic writing tends to focus more on ensuring a cohesion between the writer’s argument, theoretical framework, and methodology. Both types of editing require clarity and effective organization and structure.

Kris: How can a writer make sure they are capturing the right voice in a text?

Kris: How can a writer make sure they are capturing the right voice in a text?

Osita: In order to capture the right voice, the writer must clearly define the purpose and goal of the writing and the audience must be identified. The writer should reflect on what she wants to accomplish and then evaluate the best techniques to reach that goal. It’s helpful for personality and character to shine through the writing too. This helps to establish a unique voice for the writer and builds familiarity and trust between the writer and audience.

Kris: So would you say that that editing can make a piece more or less accessible?

Osita: Editing creates the opportunity to shape and refine a text, to turn binaries into nuances and vice versa. The final product should be easily accessible, especially in terms of work that can effect social change. A work is meaningful if it is within reasonable reach of the masses. However, accessibility of language is just as crucial. If an audience can’t relate to your verbage or lingo, then you are missing the mark. As a journalist, PR professional, and scholar, I’ve written for audiences that include lobbyists, lawmakers, public housing residents, educators, students, and the wider community at large. Each piece requires a strategy of knowing your audiences and ensuring that your writing relates to their daily lives, work, and experiences. There may be times when I write for different audiences in one piece. In those cases, it becomes important to evaluate the best ways to allow my message and writing style to intersect and effectively reach diverse audiences.

Kris: What do you think writers need to keep in mind when writing about people or characters with backgrounds dissimilar to their own?

Osita: When writing about people or characters with backgrounds different from your own, writers should assess why they are choosing to write about another group in the first place, who their writing will serve and how. It is important to reflect on the writer’s true intentions and the social, cultural (and other) impact of their work.

I would advise writers who are writing outside their identity to first conduct ample research about whatever social group they are writing about. This includes engaging in in-depth dialogue with the persons or communities that are different from their own. Understanding other people’s experiences, perspectives, desires, ambitions, work, etc. is essential when attempting to write about groups or communities different from the writer’s own social group/community. Assumptions, often incorrect ones, are easily made but are even easier to prevent by communicating in a very open and honest way about your intention as a writer and your willingness to accurately reflect different people’s experiences and perspectives in your work for altruistic purposes. If it is determined that one’s work may do more harm than good or not accurately or appropriately reflect other groups and their experiences, writers must step back and re-evaluate their motives and, if necessary, step away from it all together. Now more than ever, all different forms of writing are needed to generate understanding around a variety of issues and bring about justice for people and communities that have long been confined and oppressed. I believe our job as writers is to use our words to figuratively and literally break those chains and liberate minds, people and communities. We indeed have the power to do it.

Kris: Are there any specific grammar rules, punctuation marks, or word usage issues that you wish more people paid attention to?

Kris: Are there any specific grammar rules, punctuation marks, or word usage issues that you wish more people paid attention to?

Osita: Possessives. We must know the difference between its and it’s! But more importantly, we should always be mindful of our subconscious usage of code words that may have adverse associations and implications.

Kris: That’s a fascinating answer, and one worth spending some time on when examining our writing. As a final question, what do you know about writing and editing now that you wish you’d learned earlier?

Osita: I started out writing short fiction stories and poetry as a child, then later journalism and public relations pieces as a mass communication professional and academic writing as a student-scholar. I’ve always utilized my writing to raise awareness around social justice issues. Through the course of my writing within different genres, I’ve discovered that there is an intertextual dynamic to all different types of writing and that creative and innovative spaces arise when genres intersect. For example, there is indeed a space where creative, journalistic and academic writing can effectively co-exist (think cadence, flow, writing style, use of figurative language, direct quotes, etc.) that may allow the writer to connect with audiences in a multi-layered, inventive and transformative way.

I like ending on this note. Connecting with audiences in a transformative way is a complex undertaking, but that should never slow a writer down. When we look at the world around us and have something to say, our words are often our best tool for awareness and the creation of change.

Thank you so much, Osita Iroegbu , for sharing your time and wisdom, and happy writing, folks!

Join 550+ subscribers and sign-up for my monthly email newsletter for more interviews like this.

The post Authors on Editing: Interview with Osita Iroegbu appeared first on Kris Spisak.

May 18, 2017

Writing Tip 220: “Manner” vs. “Manor”

Mind your “P”s and “Q”s and your spelling, please.

It’s time to mind our manners, everyone, and today, I’m not just talking about communicating with respect. I’m talking about knowing the difference between “manner” vs. “manor.”

Communicating with your pinkie up in the air isn’t quite cutting it here.

Remember:

“Manner” means a way or style of doing something—for example, hitting the books in a studious manner or hitting the books literally in a frustrated manner.

“Manners” means social etiquette—for example, being quiet shows you know your manners in a library.

“Manor” means an estate or grand residence.

“Manors” means many of these mansions.

Minding your manners when you’re at the family manor is probably important—minding how you spell these two words is equally significant. Meanwhile, it would be fun to always refer to your house as your “manor”—no matter how grand it might be. I think I might just this myself. Pip pip, cheerio, and all that.

Happy writing, everyone!

Join 550+ subscribers and sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more tips like this.

The post Writing Tip 220: “Manner” vs. “Manor” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

May 12, 2017

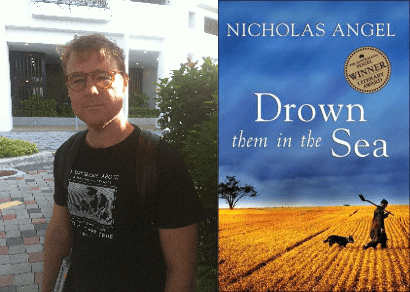

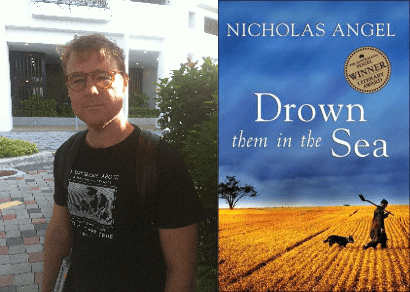

Authors on Editing: Interview with Nicholas Angel

Meeting talented storytellers from around the globe is especially fascinating to me because of the natural kinship that’s always there among writers. We are solitary in our work, but our struggles are universal—finding authenticity in our characters and our words, stretching constantly toward that finish line that often feels so far away.

When I recently had the pleasure of meeting Nicholas Angel as he was traveling through the United States doing authenticity research on an upcoming novel, I not only appreciated his cultural thoughtfulness but also his clear dedication to his craft.

Nick Angel, 38, grew up in rural Australia. He previously worked as a lawyer in Paris, Sydney, Cambodia and Myanmar. For several years, he was an environmental lawyer. His first novel, Drown them in the Sea (Allen & Unwin, 2005) received popular and critical acclaim and was a winner of the Australian Vogel Literary Award, Australia’s most prestigious award for authors under the age of 35. He was also the recipient of the Sydney Morning Herald’s Young Novelist of the Year Award.

For the past four and half years, he has lived abroad in South East Asia, the Middle East, and Europe (presently in Berlin). He is a French speaker and translator.

He has a new novel Temple & Dean, which will shortly be on submission with Australian/European literary agency Zeitgeist Media. Temple & Dean is set in a fictional town in the United States.

Q & A with Australian Vogel Literary Award-winning Author Nicholas Angel

Kris: What does the word “editing” mean to you?

Nick: Editing is about improving my work. I need several drafts to get the best out of a story. Partly, this involves preparing each draft for a reader, which means I’m looking at it from a reader’s point of view. A big part of this is begging someone to read my work. If someone takes the time to do so, there’s a lot to be thankful for. It takes ages to read a book, and if someone reads mine, they’ve probably missed out on a lot of good things to do it, like reading other, already published books. Then there are all their ideas and feedback (usually provided free of charge). It’s easy to forget all that in the blind quest for admiration. I always try to be grateful as most feedback is good feedback for me. I consider all of my reader’s comments and test them. Some I implement and others I don’t. No one knows my story better than I do, so ultimately editing is my responsibility.

Kris: I love your point about being thankful for your early readers. Writers hungry for feedback often don’t think about the other side of things. Wonderful note. Now, what was the most important lesson about revision you learned with your first book publication?

Kris: I love your point about being thankful for your early readers. Writers hungry for feedback often don’t think about the other side of things. Wonderful note. Now, what was the most important lesson about revision you learned with your first book publication?

Nick: Sometimes revision feels like work or can pinch a little when an editor dismisses some carefully crafted words. But like most things, the more work you do, the better. I learned that editors made me question my own work. Not just punctuation and flow but also storytelling. Part of the process involves checking whether the devices and mechanisms you’re using are effective.

Kris: What does your editing process look like?

Nick: I do it as I go. I write several drafts of a manuscript before submitting. It’s my understanding that the manuscript needs to be as pristine as it can be before submission. I’d go so far as to hire an editor before submitting, rather than leave significant work for an editor with a publishing house.

Kris: That’s certainly a wise approach in the competitive publishing industry of today. I’d love to dig a bit deeper into different pieces of your editing process. When you are revising your characters, what specifically are you looking for? What are you trying to accomplish with them before you consider them fully fleshed out and alive on the page?

Nick: There’s a lot I could say about this, mostly about how much I’ve struggled. Succinctly, my characters’ desires and their challenges move the plot forward, so I try to make them genuine. Ultimately, I’m trying to create characters that a reader can empathize with. It takes me a long time to feel I know my characters well enough to start in on their complexities. I have to be patient.

Kris: I know that feeling. Patience with characters that are slow to reveal themselves can be hard. How important to you is knowing a setting first hand? How does this experience change your early writing?

Nick: Setting is relative to the story. I think there’s a contract between the reader and author about creating an emotional connection. A reader doesn’t have to have visited the settings of an author’s novel because the reader has an imagination, but the author must convey an authentic sense of place. For some stories—like say a story about a fictional small town—a deliberately prosaic setting might work. For others, accuracy of setting is crucial—a story set in a well-known city cannot afford to contain setting errors. My overall view is that it would be a huge shame for literature if stories had to be bound by time and place of the author’s first-hand experience. If that were the case, we wouldn’t have any sci-fi. We wouldn’t have much historical fiction, and we’d be short on a lot of literary fiction too.

Kris: What are your biggest considerations when you’re looking at the story arc of your first draft? What kind of changes do you find yourself making to strengthen your plot or pacing?

Nick: My first drafts can be a million miles from the finished story, so there’s not a whole lot that’s safe. Everything may be cut/chopped for the sake of tightening the story. I try to save dramatic turns within the story that feel correct. I try to save writing that I feel carried along with. At this point of the process, I know I’ve still got a lot of work to do, so I’m not too precious about the words I do have.

Nick: My first drafts can be a million miles from the finished story, so there’s not a whole lot that’s safe. Everything may be cut/chopped for the sake of tightening the story. I try to save dramatic turns within the story that feel correct. I try to save writing that I feel carried along with. At this point of the process, I know I’ve still got a lot of work to do, so I’m not too precious about the words I do have.

Kris: Does knowing your target audience change your revision process?

Nick: I don’t think of a particular niche audience when I’m writing. I approach the task broadly. I know I write strongly when I’m writing about something I believe in and that sense of belief is what I hope props up my writing and is transplanted into the mind of my reader. Who that reader is shifts from character to character during the process. If I’m writing a woman, I’m trying to think of how a woman reader would relate to my character. Same with a war vet, same with a truck driver. If I’m writing a truck driver, I’m trying to empathize with a truck driver as I’m writing so the resulting character is genuine. If I do all that, I hope a wider audience will find my characters credible and the story will benefit as a whole.

Kris: What do you know about writing and editing now that you wish you’d learned earlier?

Nick: I was always impatient to say, “I’m finished.” Now I like to let things settle, re-read, polish, repeat…have read, tinker… then say “what do you think of this?”

Oh, that settling time is so necessary to a project, as is the tinkering. I love ending on this note, because the editing process is never a simple once-over. It’s never a quick review. Solid revision takes a lot of work and passion (and maybe even some exhaustion), but the end result of a well-edited manuscript always shines.

Thank you for your time, Nick Angel, and happy writing, everyone!

Join 550+ subscribers and sign-up for my monthly email newsletter for more interviews like this.

The post Authors on Editing: Interview with Nicholas Angel appeared first on Kris Spisak.