Kris Spisak's Blog, page 2

March 30, 2022

Writing Tip 442: Catching “Flak” or “Flack”?

“Flak” or “flack” – this debate is in many ways a battle (or at least goes back to one).

“Flak” or “flack” – this debate is in many ways a battle (or at least goes back to one).Should we talk about not catching “flak” when wearing your flak jacket? Is “flack” spelled similar to “quack”? Or else “flac” like “Big Mac”? “Flaque” like “plaque”?

First things first, let’s narrow it down to just “flak” or “flack” for this conversation.

Catching flak/flackGetting flak/flackTaking flak/flackAs always, there’s a right answer, but there’s also a larger discussion. And this time, the conversation involves artillery, publicists, and the author Tom Wolfe. Sure, this sounds like the setup of a bad joke that I’ll catch flak/flack for, but stay with me.

Here’s what you need to know:

“Flak” and “flack” are both words.Historically:

“Flak” derives from the German word fliegerabwehrkanonen, a combination of “flier” “defense” and cannons.” In World War II, the fliegerabwehrkanonen, which were pretty much anti-aircraft guns, were often abbreviated as “flak.” Thus, to be “catching flak” was a literal reference to catching gunfire. You can see where the “FL,” “A,” and “K” come from in this German word, but remember that there is no “C.” The word “flak” might look awkward to English speakers, but this is the original correct word. (If you’re now thinking about other war-based expressions, like “how do you like them apples?,” your head’s in the right place.)

“To catch flak” in a figurative sense, as in to take harsh criticism (as opposed to gunfire), began to appear in the 1960s, and it’s been a common expression ever since. However, this isn’t the end of the story.

Catching, taking, getting, or receiving “flack” started to appear in the late 1900s. Where did this come from? Well, it may be a typo that gained popularity, but there’s also another word to bring into this discussion.

“Flack” has been synonymous with “publicist” since the 1930s, interestingly enough (annoyingly enough?) the same decade that “flak” entered the English language. The origin of “flack” has a few theories, but it’s most commonly tied to a well-known Hollywood press agent of the time, Gene Flack. Was the man so good at his job that his name became synonymous with the type of work he did? Possibly. Kudos.

So, knowing this, here’s a true statement: a flack (publicist) might catch flak (criticism) for how they portray a book about fliegerabwehrkanonen (flak).

End of story? Almost.

The English language, as we know, can sometimes be fluid, and this is the continuing story of “flak” or “flack.”

As I noted, “flack” started being used for both definitions in the late 1900s, and these days, many consider “flack” to be an acceptable alternate spelling of “flak.” Why? We don’t know. The English language keeps us on our toes, and sometimes social acceptance leads to language transformation. (I’m looking at you, single-word-form of “nevermind.”)

But where does Tom Wolfe come into this story?

Well, in his 1970 book, The Bonfire of the Vanities, he wrote about “flak-catchers.” And who were these “flak-catchers”? They were workers whose jobs were to respond to criticism. These were not technically “publicists” in his novel; however, the connection between “flak-catchers” and those known as “flacks” seemed to stick in the public mind.

So, there you have it: guns, publicists, and Tom Wolfe.

These days, you might be able to get away with spelling this word “flak” or “flack”; however, the historical record argues for “flak” if we’re talking about criticism. And in the end, I will too.

Sign-up for my monthly language tips and trivia email newsletter for more articles like this.

The post Writing Tip 442: Catching “Flak” or “Flack”? appeared first on Kris Spisak.

March 16, 2022

Writing Tip 441: If I “do” or “don’t” say so myself

This duck’s feeling pretty good about himself, I think, but would he or wouldn’t he say so himself? Is that the question?

This duck’s feeling pretty good about himself, I think, but would he or wouldn’t he say so himself? Is that the question?Bragging’s not good, but a little bit of confidence can be powerful. I’m not talking about #humblebrags or #sorrynotsorry comments. When you’re with the right listener and you want to toot your own horn (there’s an expression we need to dive into on another day), what’s the correct phrase to follow your statement of pride?

Is it “If I do say so myself” or “If I don’t say so myself”? If I “do” or “don’t” say so myself?

Let’s break this down:

“If I do say so myself” is like an asterisk added to a statement that, sure, you might be biased, but you’re going to say it anyway. Speaking of one’s own talent, skill, or accomplishments might sound to arrogant or boastful; however, that’s not stopping the speaker. And they’re okay with that. All cards on the table.“If I don’t say so myself” implies you aren’t saying anything. So… this one doesn’t quite make sense, does it? If you’re not speaking, you won’t have a statement about not speaking.Thus:

The correct idiom is “If I say so myself” or “If I do say so myself.”This expression seems to first have appeared in the early to mid 1800s, with “do say so myself” the clear dominant (and logical) phrase. There’s a tiny early blip (in the 1820s and 1830s, and again in the 1860s) where the negative form (“do not” or “don’t”) being more commonly used in the written record; however, these were relatively minor numbers in comparison to the modern expression.

The data, you ask? Oh, I do love data:

(Thanks to Google Books Ngram Viewer for the chart.)

I think that about sums it all up, if I do say so myself. And I am saying it. Aloud. (If you could only hear me. I really am saying it aloud as I type this.) Got it?

Sign-up for my monthly language tips and trivia email newsletter for more articles like this.

The post Writing Tip 441: If I “do” or “don’t” say so myself appeared first on Kris Spisak.

March 2, 2022

Writing Tip 440: “Invisibility” or “Invincibility”?

Should we talk about this butterfly being partially “invisible” or “invincible”? Ooh, there’s a story hiding here.

Should we talk about this butterfly being partially “invisible” or “invincible”? Ooh, there’s a story hiding here.Which would you rather have as your superpower: “invisibility” or “invincibility”? To be “invisible” or “invincible”?

Both have their perks, but that’s perhaps beside the point. Do you know the difference between these two words?

Remember:

“Invisibility” means unable to be seen.“Invincibility” means unstoppable or unconquerable.So many questions come up with this pairing:

Does the star “power up” give Mario and Luigi “invisibility” or “invincibility”?Nintendo asks for confusion here with a partially transparent/invisible visual effect; however, technically, the star gives a character “invincibility,” as in they can walk into enemies without being harmed.

Did H.G. Wells write The Invisible Man or The Invincible Man?In 1897, Wells wrote The Invisible Man. “The Invincible Man” would be a different story, perhaps a superhero comic. Does that already exist?

Does Harry Potter have an “invisibility cloak” or an “invincibility cloak”?While it seems, at times, that “The Boy Who Survived” is invincible against “He-Who-Shall-Not-Be-Named,” his cloak allows for him to be “invisible.”

Do new camera apps make that photo bomber invisible or invincible?Okay, here’s a fascinating (terrifying?) idea, but as for now, you can erase people or other background items with some photo apps, making them seem “invisible.”

In the classic story of “The King’s New Clothes,” are his clothes invisible or invincible?Ooh, trick question. The clothes aren’t there at all. (There’s a lesson about gullibility and not believing everything you’re told here I can’t help but give a shoutout to).

Yes, “invisibility” and “invincibility” are similar; however, we get sloppy when we don’t think before we write (or speak).

“Invisibility” comes from the prefix “in-,” meaning “not,” combined with the Latin word visibilis, meaning able to be seen.“Invincibility” comes from the same prefix plus the Latin word vincibilis, meaning “to be gained, easily maintained, or conquerable.”Both of these words have been around a long time, since the 14th and 15th century, respectively.

As for superpowers, in video games or otherwise, with great strength comes great responsibility, but for the sake of this conversation, let’s just stick to the responsibility of getting our language right.

Sign-up for my monthly language tips and trivia email newsletter for more articles like this.

The post Writing Tip 440: “Invisibility” or “Invincibility”? appeared first on Kris Spisak.

February 16, 2022

Writing Tip 439: “Collaborate” vs. “Corroborate”

Ooh, you’re savvy with your words, but do certain pairings like this still trip you up? And how on earth am I relating this to peanut butter?

Ooh, you’re savvy with your words, but do certain pairings like this still trip you up? And how on earth am I relating this to peanut butter?

No worries, wordsmiths. You’ve got this, and stay tuned for that second answer. Here’s what you need to know about “collaborate” vs. “corroborate” once and for all:

To “collaborate” means to work together on something. Kids could collaborate on a poster board project in school. Co-workers could collaborate on a client pitch. You could argue that we all try to collaborate to make the world a better place. (Or we all should, anyhow!)To “corroborate” means to confirm or give support to, most commonly with evidence or with known authority. This word does still imply a sense of “togetherness”; however, it’s more along the lines of backing someone or some idea up, rather than a joint effort. Thus, a student might corroborate a friend’s story that their dog did indeed eat the homework (if they were perhaps a witness and/or the witness who dropped his or her peanut butter sandwich on top of the said homework to make this event unfold); a coworker might corroborate the data presented by a peer, verifying the market results to the company board. Perhaps you want to corroborate the idea that getting our words right (and a grip on our grammar) can indeed change the world, because you have hard data that supports my claim.“Collaborate” vs. “corroborate” is a matter that might make many pause, but these two words aren’t as difficult to understand as you might think.

Regarding their origins, “collaborate” comes from the late Latin word collaboratus, which could further be broken down to its source com-, meaning “with” or “together,” and laborare, meaning to work or labor. To work together. Collaborate. Nice and easy for you.

“Corroborate” comes from the Latin corroboratus, which could be further traced back to com- combined with robur, meaning strength. With strength. Only with strength will whatever is being claimed be trusted, right?

I see you, kids and your dogs who eat your homework. Is this the oldest trick in the book? Maybe. I would need someone to corroborate that.

Sign-up for my monthly language tips and trivia email newsletter for more articles like this.

The post Writing Tip 439: “Collaborate” vs. “Corroborate” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

January 26, 2022

Writing Tip 438: “Cocoa” vs. “Cacao”

What kind of beans are those?

What kind of beans are those?We’re not talking pronunciation differences à la “tomato”/”to-mah-to” or “potato”/“po-tah-to.” We’re not talking regional differences. There is a distinction worth knowing when using “cocoa” vs. “cacao”; however, do you know what it is?

And when I say “using ‘cocoa’ vs. ‘cacao,’” I suppose I could be talking about usages in a recipe or in a sentence. Subtleties matter here in both circumstances.

Chocolate fans, listen up. Here’s what you need to know:

“Cacao” is a plant, native to South America. Thus, we could discuss cacao trees, cacao pods, and cacao beans—all usages here in their natural state. But “natural” in itself is a messy word. (Browsing any grocery store can show you that, right?) Let’s just say “cacao” is the term to use when there is no processing with high heat involved.“Cocoa” comes from “cacao,” but the original form has been roasted or otherwise exposed to extreme heat. It can still remain in bean form, or it could be further processed (think crushed or mixed with other ingredients) to become cocoa powder, cocoa butter, and countless other varieties.Let me repeat that: you could indeed have “cacao beans” or “cocoa beans”; it’s just a matter of how much they’ve been tampered with (or not).

Similarly, you could have cacao powder or cocoa powder. “Cocoa powder” is more common, especially in America, as an ingredient in everything from hot chocolate (a.k.a. “hot cocoa”) to candy bars. There are often additives involved in these cocoa-based products like sugar or milk fat, though. “Cacao powder” might be harder to find, but it is simply the powdered form of non-roasted cacao beans. Both “cacao powder” and “cacao nibs,” which are finely chopped cacao beans that could be substituted for a healthier version of “chocolate chips,” might be in the midst of a popularity surge, so it’s certainly worth knowing the difference. It is far more than a hipster spelling trick.

The word “cacao” derives from the Olmec and Mayan word kakaw, but perhaps my favorite etymological tidbit is in the tree’s scientific name: Theobroma cacao. While we know scientific names are in Latin, theobroma is inspired from the Greek words θεος, meaning “god,” and βρῶμα, meaning “food.” So yes, we’re talking “food of the gods” here. There’s a historical tradition with this connection, and it trickled into the scientific classification. Don’t etymology stories like this just make you happy? Or maybe that’s the phenylethylamine in the chocolate having that effect.

Health benefits of “cacao” vs. “cocoa” aside—though, there’s a conversation I’ll absolutely lean into—the differences between these two words are not always correctly distinguished. In fact, if you pay attention, you’ll see them incorrectly written quite frequently. But you, savvy language and chocolate connoisseur, now know the difference.

Bon appétit, and happy writing!

Sign-up for my monthly language tips and trivia email newsletter for more articles like this.

The post Writing Tip 438: “Cocoa” vs. “Cacao” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

January 12, 2022

Writing Tip 437: “Gray” vs. “Grey”

What color is this cat? No, he’s not judging you as you decide… why would you say that?

What color is this cat? No, he’s not judging you as you decide… why would you say that?Whether you want to blame Ben Franklin or Noah Webster, sometimes, the English language seems unnecessarily complicated, doesn’t it?

The spelling of “gray” vs. “grey” is another such case.

But, wait, there is an answer to your question. You just need to specify which gray/grey you’re looking for.

Fancy mustard? Grey PouponBreakfast tea? Earl GreyRacing dog and/or busline? GreyhoundOscar Wilde novel? The Picture of Dorian GrayOld horse who ain’t what she used to be? The Old Gray MareTissue in the brain and spinal cord and/or an abstract term for intelligence? Gray matter, more commonly, but both are used.The purchasing power of older generations? The gray dollar or the grey poundColor? Let me answer that question with another that you might have seen coming: where do you live?In American English, the color is spelled “gray.” In British English, which is used across much of the world, the color is spelled “grey.” Both are correct. It’s just a matter of audience expectations and perhaps the writer’s background.

Let Earl Grey tea (clearly British) and the Old Gray Mare (of the American folksong canon) be your touch points here. If ever there was a contrast showcasing particularities of both sides of the pond, this might be it.

“Earl” begins with “e,” thus Earl Grey helps remind you of the British spelling.“Mare” has a long “a” just like “gray”; thus, that old horse speaks for the States.First names, surnames, and ways to describe a cloudy day aside, sometimes the choice of “gray” vs. “grey” seems complicated. The English language can make all of us pause sometimes, but as we continue pursuing our best, we just have to keep at it. Perseverance can lead to great things—there’s no gray/grey area in that debate, folks.

Sign-up for my monthly language tips and trivia email newsletter for more articles like this.

The post Writing Tip 437: “Gray” vs. “Grey” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

December 1, 2021

Writing Tip 436: How do you spell “on the lam”? (“On the lamb?”)

Is this lamb on the lam? Or is there just an annoyed expression on the lamb about the constant misspelling of this expression?

Is this lamb on the lam? Or is there just an annoyed expression on the lamb about the constant misspelling of this expression?Of course you know! Or, do you?

How do you spell “on the lam” / “on the lamb” again?Simple answer: “On the lam” (L-A-M) is the correct spelling of this expression.

Less than simple answer: But we don’t quite know where this expression comes from.

Oh, English language. There you go again.

Does this expression come from… ?

A. The Irish word leim, which means “to jump”B. The British slang word “namase,” which meant “to skedaddle” around 1855C. The Scandinavian verb lam, meaning “to beat”D. The English word “slam”All have been postulated, but only one is likely correct.

This is where we insert Jeopardy! music or etymologists heckling each other. No, you’re right. We would never do such a thing.

Well, getting back to the debate, the leading theory seems to back up option C, but just because it’s the leading theory does not mean that this is a decided matter.

Here’s what you need to know about our options for the origin of “on the lam”:

A. The Irish word leim, which means “to jump”While this theory was published in Daniel Cassidy’s How the Irish Invented Slang, which won an American Book Award for nonfiction in 2007, its historical accuracy isn’t greatly accepted by the etymology community. Based on possible phonetic connections and a close definition match, not research into the evolution of language, this theory has been widely discounted; however, you can see why the author might want to stake a claim in this idea.

And it hasn’t been definitively disproven, so it still lingers in the conversation.

B. The British slang word “namase,” which meant “to skedaddle” around 1855Slang is endlessly fun, isn’t it? It transforms language rapidly, and sometimes, certain words or phrases stick long after the masses remember where they came from. (See “hipster,” “jive,” “bloomers,” and so many more, right?)

In the mid-nineteenth century, the word “namase,” alternatively spelled “nammou” and possibly “lammas,” might have meant “to run off.” It might also be related to the Old American West slang word “vamoose.” Now, I love word stories like this, but there’s not as much depth here as I would like for me to commit to this answer.

Side note: In 1972, Woody Allen wrote about the origin of “on the lam” in a humor essay titled “Slang Origins.” His theory, which was different from the above slang conversation, involved feathers, dice, and twirling in a frenzy, but the moral of the story is that we always need to be aware of our sources and whether they’re academic or not. Woody Allen’s essay was humor, not true etymological theory.

C. The Scandinavian verb lam, meaning “to beat”Mark Twain used the word “lam,” meaning “to beat,” and his usage draws back on a word that the Oxford English Dictionary says came to English in the 1500s. Merriam Webster backs this up, citing a root “perhaps of Scandinavian origin; akin to Old Norse lemja to thrash; akin to Old English lama.” Words connected to this version of “lam” include “lambaste,” “lame,” and “bedlam.”

By the mid-1800s, school kids in both England and the United States spoke of schoolyard brawls as “lamming out” or “lamming into” someone. A beating or thrashing is implied. Mark Twain, as always, is capturing the language of his era.

We also have a connection with a thief about to flee after a successful robbery from famed Scottish detective Allan J. Pinkerton in his 1886 memoir, Thirty Years A Detective, where “lam” was a code word for a successful theft and preparing to flee.

So to avoid a lamming, one lams? The expression took early forms of “take a lam,” “do a lam,” and “make a lam,” before it’s present usage of “being on the lam.”

Fun extra side note, the expression “to beat it,” meaning “to leave quickly” might be etymologically related to being “on the lab” if this “beating” origin story is our correct answer. Beating one’s feet on the pavement (or dirt… or cobblestones…)? Avoiding a beating all the while?

Ding, ding, ding. Do we have a winner? Maybe. At least, it seems the most likely.

D. “Lam” is related to the English word “slam”I’m going to note this answer because I’ve seen it suggested online; however, again, there doesn’t seem to be much in the historical record to argue for it.

So, is this more than you ever wanted to know about being on the lam? But at least you know there are no sheep involved, so I’m calling that progress.

Are there any other expressions that you’re curious about? As always, please let me know, and good luck to you and your words, folks!

Sign-up for my monthly language tips and trivia email newsletter for more articles like this.

The post Writing Tip 436: How do you spell “on the lam”? (“On the lamb?”) appeared first on Kris Spisak.

November 24, 2021

Writing Tip 435: How many sheets to the wind?

And while we’re talking about the expression, what’s the origin of it anyway?

And while we’re talking about the expression, what’s the origin of it anyway?Are you imagining laundry hanging up to dry or a bit too much of a celebration? Or if you know where I’m going, here’s your next question: how many sheets to the wind are we talking about?

In 1737, Benjamin Franklin published The Drinker’s Dictionary, a list of 228 “round-about phrases” to describe drunkenness. (More on that coming soon). Admittedly, no version of “sheets to the wind” or “sheets in the wind” (a possible older version) appeared on this list, but as you know (or might have guessed by this point), we’re talking about one more colorful expression to describe one who has imbibed too much alcohol.

Why do we need so many words and phrases? (A 2009 publication on the same subject included nearly 3,000 possibilities!) Well, to quote Franklin:

“Mankind naturally and universally approve Virtue in their Hearts, and detest Vice; and therefore, whenever thro’ Temptation they fall into a Practice of the latter, they would if possible conceal it from themselves as well as others, under some other Name than that which properly belongs to it.”

So, sure. Drunk. Sloshed. Wasted. Or, two of my favorites from Franklin’s list, “clipping the King’s English” or “contending with the pharaoh.” Maybe, as Franklin suggests, we have these words because reaching such a state is a shameful vice worth covering up. But whether you agree with this assessment or not, let’s get back to those sheets.

The expression for drunk is “three sheets to the wind” (most commonly).Wait, most commonly?

Indeed.

Some argue the number “three” is a part of a scale, where one sheet to the wind is a bit tipsy, and four is losing consciousness. Three then, according to this scale, is wildly, flailingly drunk. Or perhaps “nimptopsical” to quote Franklin again.

So, now you know: in modern usage, the expression is “three sheets to the wind.”

But wait, there’s more.

Beyond adding another possibility to the profusion of synonyms for “drunk,” this isn’t the end of our conversation, because, of course, one might wonder about these sheets and their origin.

First things first, we’re not talking about laundry on the line, so we can take that off the list; however, there are two possible origin stories for “three sheets in the wind”—both of which are solid contenders. There might even be a connection between the two.

The most likely “three sheets to the wind” etymology story comes from either the idea that:

Traditional windmills, most commonly, had four vanes or rotors that caught the wind. These rotors were covered in sheets, and caretakers of windmills might apply different numbers of sheets in different circumstances, for example no sheets when the windmill isn’t in use, two sheets for a slower rotation or in high-wind situations, or four sheets to fully capture the breeze. But what happens if one were to use one or three sheets? The entire windmill would be off-balance and wobbly, jerking and sputtering like a drunk, no? Historical records note many keepers of windmills claiming this expression, and because of the international usage of windmills on sea shores, sailors might have carried the expression from place to place.or

Sailors who’ve had too much to drink can be terrible at taking care of their ship. Now, we’re not talking about the “sails,” which one might assume when we’re saying “sheets.” No, different ropes have different names, depending on whether they’re vertical, horizontal, or otherwise, it seems. (Here’s where I insert my disclaimer that I’m only learning these nautical terms, so I welcome any clarification). But in short a “sheet,” as opposed to a “line” or a “halyard,” would be a specific type of rope or used to secure the mainsail and the headsail. And if three sheets were in the wind, meaning they’re not secure, the ship wouldn’t be able to sail as smoothly as it could. It might be juddering and out of control in its own right. Like someone drunk, right?So windmills? Another nautical origin story? Both have their claims and their defenders, and personally, I’m going to keep digging. But what we do know in the end of all of this is that the magic number is three.

“Three sheets to the wind” is the expression you’re looking for. Not ten. Not twenty. Those guesses miss the mark. If they’re quoted to you by someone who’s had too much to drink, that’s one thing; however, now you, at least, know better.

Cheers!

Sign-up for my monthly language tips and trivia email newsletter for more articles like this.

The post Writing Tip 435: How many sheets to the wind? appeared first on Kris Spisak.

November 3, 2021

Writing Tip 434: “Chalk it up” vs. “Chock it up”

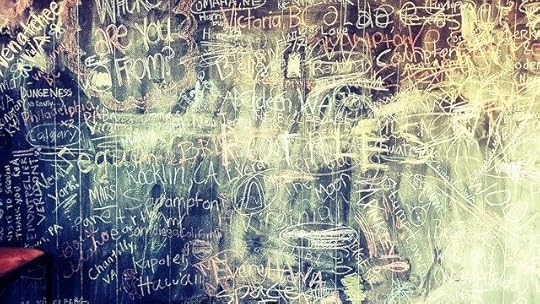

If you’re not sure about this one, here’s your big, messy hint. (Who’s having flashbacks to cleaning chalkboard erasers? Just me?)

If you’re not sure about this one, here’s your big, messy hint. (Who’s having flashbacks to cleaning chalkboard erasers? Just me?)We could chalk it up to the speed of communications these days muddling things, or we could chalk it up on the sidewalks of our cities and towns. Either way, there’s something we need to remember with this phrase. You might be “chock-full” of ideas, but let’s clear this up once and for all.

When it comes to the question of “Chalk it up” vs. “Chock it up” …

The correct phrase is “chalk it up” not “chock it up.”It’s all a matter of giving credit where credit is due—often figuratively these days. However, the origin of this phrase does call back to literally writing debts in chalk. If one owed a store a certain amount of money, the store owner would chalk it up on the wall to keep track of it. (Ah, the days before ecommerce, mobile credit card readers, and crypto)

Now, “chock” is indeed a word. It dates back to at least the 1600s and has a few meanings, from a solid metal casting that might appear on a bow or stern of a ship to a wedge that blocks movement of a cask or a wheel. These days, we don’t generally see “chock” on its own; however, it does still appear in the word “chock-full” (most commonly hyphenated, but sometimes spelled “chockful”). But there’s a twist you might not see coming here.

The word “chock-full” is older than the word “chock.”

Gasp. I know. I had the same reaction.

Bonus Writing Tip: If something is “chock-full,” as in filled to overflowing, we’re not talking about overflowing with blackboard chalk but we’re also not talking about heavy metal or wedges to stop casks from rolling away. In this case, we are indeed looking for “chock” with an “o,” but “chock-full” has been around since the 1400s.

It’s just the English language keeping you on your toes, folks. But you knew that already, right?

Sign-up for my monthly language tips and trivia email newsletter for more articles like this.

The post Writing Tip 434: “Chalk it up” vs. “Chock it up” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

October 20, 2021

Writing Tip 433: About those “kid gloves”

Yeah, I know. I’m sorry, little guy.

Yeah, I know. I’m sorry, little guy.If you’re handing something with kid gloves, what comes to mind? Small gloves? Or is it something else?

While the meaning is largely understood, the phrase “to handle with kid gloves”—as in to handle something delicately—should not in any way be connected with children.

Well, unless you mean a goat child, which brings us right back to the word “kid,” doesn’t it?

Yes, when you hear about those “kid gloves,” it’s not a reference to gloves for young people. The expression originates in reference to gloves made from “kid leather,” as in the skin of young goats or often young sheep. But we don’t often hear about “lamb gloves,” even if that may have been more accurate. It’s usually the “kid gloves” that get the attention.

Why kid gloves? Well, if you want to get down to specifics about leather, kid gloves are incredibly soft. In the 1700s, they could be found upon the hands of the wealthy who deemed them luxurious, as well as white-gloved butlers and servers who would be sure to wear them when handling silver, glassware, or anything that might smudge. Some deemed them ostentatious; some deemed them impractical; some deemed them simply lovely.

However, whether speaking about handing something gently (like candlesticks) or taking care of the gloves themselves (which weren’t always long-lasting because of their fine nature), it’s understood that careful conduct was key.

It’s less about the size of the gloves or the wearer. It’s all about the material. Of course, now the phrase is an idiom that can refer to handling people or situations carefully too. There are no literal gloves involved, just an expression that calls upon antiquated fashion statements and/or meticulously cautious touching. The phrase moved from the literal to the figurative in the late 1800s.

And as with many phrases, just because we say it doesn’t necessarily mean that we know what we’re talking about.

Next time you hear someone say something about “kiddie gloves,” you’ll know the difference. Now how to handle these English language faux pas… well, that depends on your audience. Perhaps the matter should be dealt with delicately. Perhaps, in fact, there’s an idiom that’s just perfect for this, no?

Sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more writing tips like this.

The post Writing Tip 433: About those “kid gloves” appeared first on Kris Spisak.