Kris Spisak's Blog, page 23

October 19, 2017

Writing Tip 327: “Hank” vs. “Hunk”

Oh no, a hank or a hunk? This one always seems to confuse!

Just when you think I’m going to be writing this tip about a guy named Hank who may or may not be a dreamy hunk, think again.

There are two words that mean a section of something, and these two words are “hank” and “hunk”; however, there’s a big difference between their two meanings. And it has nothing to do with their dreaminess factor.

For example, if you had a tangle of yarn, you’d have a hank of yarn, not a hunk of yarn. Do you know why?

A “hank” is a coil, knot, or loop, often of a definite length. You can have a hank of yarn or a hank of hair.

A “hunk” is a piece or portion. You can have a hunk of cheese or a hunk of clay.

If it resembles threads, cords, or twine, use “hank.” If it’s a big chunk of something that’s not stringy, use “hunk.”

Of course,

“Hank” is also a male name, often a shortened form of “Henry.”

A “hunk” is also a studmuffin.

A Hank may be a hunk, but that’s beside the point of this reminder.

Happy writing, folks!

Join 550+ subscribers and sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more tips like this.

The post Writing Tip 327: “Hank” vs. “Hunk” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

October 12, 2017

Writing Tip 326: “Now a Days” vs. “Nowadays” vs. “Nowdays”

You might be dumbfounded to learn you can just mash words together like this and call it correct, but it’s as true with “nowadays” as it is with the word “dumbfounded.”

Sometimes, when it comes to spelling, we might feel like we’re in a daze, especially when it comes to words that we hear said more than we see written.

If you were writing this phrase in the fourteenth century—if you were lucky enough to know how to read or write in that era—you would have been using a multiple word form, but language has evolved since then.

Nowadays, the correct spelling is “nowadays”—all one word. No hyphens or spaces needed.

People seem to get nervous around words like this, as if they’re just sticking things together that don’t really belong, portmanteaus like baconator or sharknado. But like spork, brunch, and netiquette, this is a mashup that truly works.

“Nowdays,” on the other hand, is simply a typo. I feel like I have days like that sometimes, when everyone seems to want things now, now now… but that’s not really what anyone’s going for with this attempt at spelling.

Got it? Good. Happy writing, folks!

Join 550+ subscribers and sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more tips like this.

The post Writing Tip 326: “Now a Days” vs. “Nowadays” vs. “Nowdays” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

October 10, 2017

Trivia: Ghost Words

“Ghost words” are dictionary entries that are typos. They are words that don’t actually exist but are printed in the dictionary. Some past ghost words that appeared include “dord,” “abacot,” and “kimes.”

Spooky? Okay, maybe not so spooky…

Join 550+ subscribers and sign-up for my monthly email newsletter for more language trivia like this.

The post Trivia: Ghost Words appeared first on Kris Spisak.

September 30, 2017

Authors on Editing: Interview with Joanna Lee

Writers can be gifted in so many ways–in the way they create characters that readers are attached to from page one, in the way they pace their stories without a wasted word, in the way their settings come alive, in the way they make readers reimagine the world around them or reexamine old subject matter in a new light, and in so many more capacities.

Joanna Lee‘s poetry shows what happens when every single word is chosen with the precision of a scalpel’s slice through skin. She has a gift with language and metaphor; plus, she knows how to throw a book launch like nothing I’ve ever seen before (ask her about it sometime if you get the chance).

This is an Authors on Editing interview that I’m incredibly excited to share.

Never having formally studied English or creative writing past high school, Joanna Lee instead focused on the sciences, earning her MD from the Medical College of Virginia in 2007 and a further Master’s Degree in Applied Science (neuroscience) from the College of William and Mary in 2010; her writing life focuses particularly on the overlap of creativity and healing.

Never having formally studied English or creative writing past high school, Joanna Lee instead focused on the sciences, earning her MD from the Medical College of Virginia in 2007 and a further Master’s Degree in Applied Science (neuroscience) from the College of William and Mary in 2010; her writing life focuses particularly on the overlap of creativity and healing.

Joanna’s poetry has been published in a number of online and print journals, and has been nominated for both Best of the Net and Pushcart prizes. A leading force behind Richmond’s River City Poets, Joanna teaches workshops and makes possible a wide range of literary happenings from Shockoe Slip to South of the James. She is currently serving as Board Chair of the James River Writers and lives in Richmond’s Northside with her husband John and their cat Max.

Interview with Poet & Ambassador of the Written Word Joanna Lee

Kris: When you are revising a newly drafted poem, what is your process?

Joanna: The first draft for me is almost always pen & paper; I like the little black moleskins that can slip easily into a purse (but not necessarily a pocket, unfortunately). When I feel there’s enough of the poem down on paper, it goes into a fresh Word document. That’s the first “real” editing I do—moving around verses or images, and maybe seeing for the first time what I was really trying to get at. The poem can change pretty drastically from notebook to laptop, actually; sometimes I find it’s not a whole poem yet at all. If it is, any further edits I do tend to be relatively minor—more finesse than construction. At the very least, though, I will read the laptop version aloud a few times before any other eyes get to see it; that usually will bring to light rough points I didn’t see while transcribing. Once I’m to the point where I can stand listening to it in my own voice, I’ll bring it to a critique group or two for feedback, to find out where my intention may not shine through as clearly as I’d like.

From there, I usually let it sit for a while, until I have in mind where it might belong: if I think it might find a home in a journal or fit in with a theme for a collection, I’ll go back and do further edits with the benefits of a more distanced perspective.

Kris: I admire the bravery of poets who present their work in front of audiences. Maybe more writers should do it–not just to ourselves but in front of friends and strangers alike. I image this helps a lot with the rhythm of a piece. When editing for rhythm, how can you be sure that you have it right?

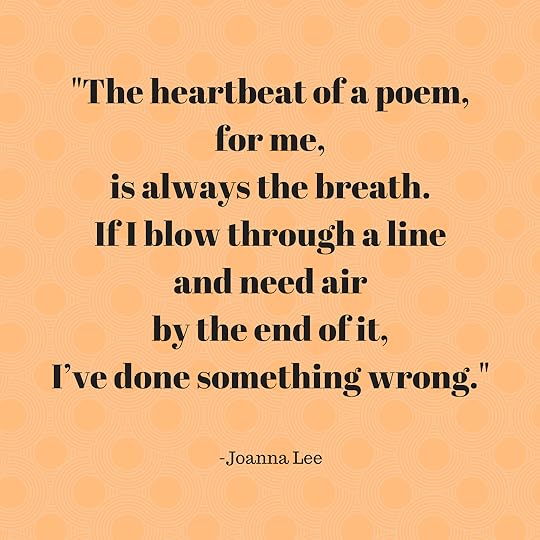

Joanna: Rhythmically, I’m not sure I ever really have it “right”; outside of a form with a prescribed meter, “right” can mean different things depending on whom you talk to. But a big part of my editing is always auditory. I think reading a draft aloud allows me to edit not only for rhythm, but also for sound. So, going back over it, I can be a little more deliberate: using a series of monosyllabic words, for example, to give weight to a verse & slow it down. Or going heavy on vowel-rich phrases to move it along. But the heartbeat of a poem, for me, is always the breath. If I blow through a line and need air by the end of it, I’ve done something wrong. I kinda believe poems exist to be read aloud, so there has to be a “resting point,” either structurally or punctuational-ly (I think I just made that word up), for every breath’s-length of poem. It’s hard to see those pauses just by looking at a poem on the page—you have to hear it, to speak it.

Kris: That’s great advice, and I love “punctuational-ly.” Speaking of words, the vocabulary that you twine through your poetry is so often thought-provoking and exquisite. What is your advice for other writers for finding the perfect fit?

Kris: That’s great advice, and I love “punctuational-ly.” Speaking of words, the vocabulary that you twine through your poetry is so often thought-provoking and exquisite. What is your advice for other writers for finding the perfect fit?

Joanna: Grr. I hate it when I can’t find the right word. I am a believer in thesauruses (thesauri?). They can usually get me close enough so I can at least will myself to move on and come back to it later. I don’t really have any great advice; not having the right word has been known to send poems to the graveyard (i.e. perpetual work-in-progress folder).

Kris: How true are you to the rules of punctuation within your poetry? Why do they or don’t they matter to you?

Joanna: I believe punctuation matters. Period. Whether you’re writing poem or prose, you have to follow the rules of usage—or be breaking them intentionally & purposefully. Sometimes a lack of punctuation can add a certain tonal effect or flow, for example, and line breaks and other structural elements can do some of the punctuational (there it is again) duty of creating pauses. But you can’t just leave out all the commas because it’s a poem… and you aren’t really sure where they go.

Kris: When playing with imagery, there’s a fine line between poignant and taking something too far. How do you know how much is enough?

Joanna: I think it comes back to the poem’s intent, and whether the images bolster or clarify it—or whether they’re just there to make the poet look clever. I find this one of the hardest things to edit, because I really can just let the images run away with me… and they may be beautiful, harsh, powerful… but if they’re gratuitous, or all over the place, they really don’t belong in the poem—it becomes a case of killing your darlings.

Kris: A powerful poem evokes emotions and themes rather than explicitly stating a point, which is something I’ve found newer poets something struggle with. How are you sure that you’re never preaching on a point?

Joanna: Sometimes there’s a fine line between “stating” (which can be okay), and “preaching” (which is generally not). And it’s hard to know which side you stand on at times. Doing things like avoiding big, overarching statements or generalizations (and cutting out words like “all,” “everyone,” “no one”) is a good first approximation. Sometimes changing the voice of a poem to the third person can help—making it more of a narrative, the sharing of a story, than a “telling.” This one is a good one to have a critique group or beta readers for; I’ve definitely read work that for reasons I couldn’t really pinpoint, made me feel ugh because of a “preachy” vibe. (“Ugh” isn’t great feedback, though.)

Kris: Do you let a new draft rest for a while before tackling your revisions or do you dive right in?

Joanna: After that first round of edits (from the notebook to the computer, then aloud), which is fairly immediate, yes, I leave it be for a while. Generally. At least overnight, and usually over many nights. Not always, though. Some poems come out more complete than others, and I’ll do a “finessing” right away and send it out into the world. That’s always a dangerous proposition, since a lot of times poems “feel” complete—feel wonderful—right off the bat… and then look not-so-hot the next morning. Kinda like a stranger you might pick up at the bar, I guess: it’s rarely true love. But it does happen.

Joanna: After that first round of edits (from the notebook to the computer, then aloud), which is fairly immediate, yes, I leave it be for a while. Generally. At least overnight, and usually over many nights. Not always, though. Some poems come out more complete than others, and I’ll do a “finessing” right away and send it out into the world. That’s always a dangerous proposition, since a lot of times poems “feel” complete—feel wonderful—right off the bat… and then look not-so-hot the next morning. Kinda like a stranger you might pick up at the bar, I guess: it’s rarely true love. But it does happen.

Kris: You’ve mentioned reading your work aloud in front of your critique group. Do you have early readers of your work that you gain feedback from too? Or do you prefer your poetry to have these early listeners? And as a follow-up, how is revision different between these two styles of early audiences?

Joanna: I am definitely my own first “early listener,” but in most every critique group of which I’ve been a part, my colleagues are both readers AND listeners: the poet reads their poem aloud while their fellows listen and follow along with a copy in front of them. Which is, I think, the best of both possible worlds. In addition to all the “usual” criticism (format, title, imagery, cohesiveness, message, etc ), it allows feedback on whether the reading aloud (the rhythm, the sounds) fits how the poem reads on the page. Do the line breaks match? Does the punctuation make sense? I think both the hearing and the reading are necessary parts of early critique.

Kris: When are you confident that your edits are finished and a piece is done?

Joanna: Probably it’s mostly that I get to a point where I feel like I don’t want to/can’t/won’t mess with it anymore—whether I’m completely happy with it or not. But on those rare occasions I am completely happy… it’s a gut thing. I just feel like it’s a good day’s (or week’s or whatever’s) work. And if I’m extremely lucky, it’ll find a place in the world and be published and adored or even change someone’s life. But even then… I may read it slightly differently at an open mic the next month… or I may come back five years from now and totally disagree with my former happy feeling and want to go and make more changes to the piece. At that point, though (published or no), it almost becomes a different poem, with a different intention, even, maybe; or maybe a slightly different author, as I’ll have changed, myself, to some degree. I don’t know that there’s a statute on when one poem ceases to be itself and becomes a separate one, or if anyone stays completely happy with a piece forever. (Heck, Whitman didn’t.) So maybe a poem is never done; that the saying is true: everything’s only a draft until you’re dead.

Sometimes, a creative piece is due when there’s a deadline, and sometimes it does continue to evolve, to reshape itself, to redefine itself, to reincarnate itself into a different work entirely. I love ending on this idea. It’s wonderful and intimidating at the same time. But when have we writers been stopped by something slightly intimidating?

Thank you so much, Joanna Lee, for sharing your thoughts on your craft, and happy writing, everyone!

Join 550+ subscribers and sign-up for my monthly email newsletter for more interviews like this.

The post Authors on Editing: Interview with Joanna Lee appeared first on Kris Spisak.

September 26, 2017

Trivia: Overmorrow

Join 550+ subscribers and sign-up for my monthly email newsletter for more language trivia like this.

The post Trivia: Overmorrow appeared first on Kris Spisak.

September 21, 2017

Writing Tip 325: Not to “Mix” or “Mince” Words

Mincing makes things mushy. Sometimes, people simply don’t want mushy.

When it comes to the English language, it’s easy to get things mixed up, but this time, I’m asking you to “mince” it up.

Why, you ask?

No, I’m not making mincemeat pies, nor am I apprenticing with a butcher. I say this because there is a difference between “mixing words” and “mincing words,” and I’ve seen this expression terribly muddled.

Remember:

To “mince your words” means to soften them (just like mincing meat makes it mushy and manageable);

To “not mince your words” (the more common expression) means to tell it like it is and to not hold back, to not soften or make anything any easier.

To “mix your words,” when you confuse an expression or use the wrong word, is something that admittedly happens to us all sometimes.

Thus telling someone not to mix their words is a fabulous example of someone mixing their words. Not that you’d ever do this though, right?

Join 550+ subscribers and sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more tips like this.

The post Writing Tip 325: Not to “Mix” or “Mince” Words appeared first on Kris Spisak.

September 19, 2017

Trivia: Hiccup

Join 550+ subscribers and sign-up for my monthly email newsletter for more language trivia like this.

The post Trivia: Hiccup appeared first on Kris Spisak.

September 14, 2017

Writing Tip 324: “Tack” vs. “Tact”

If you think that “tact” is short for “tactic,” well… you’ve got another think coming.

If you think that “tact” is short for “tactic,” well… you’ve got another think coming.

A “tack” is so much more than a pin to hold up your favorite inspirational quote by your desk. As a noun, “tack” can be a pin or flat-headed nail; it can also be a course or approach, as well as a temporary stitch to hold fabrics together. When it comes to sailing (the origin of the expression to “change tack”), there are even more definitions.

“Tact” is a matter of social grace and sensitivity. I recommend you have some tact if you’re choosing the correct others’ grammar.

To “change tact” doesn’t really make sense unless you’re talking about a major shift in cultural and social norms in dealing with a complex situation, which I’m guessing is not what you mean.

Remember, tacks can be handy for many things. It’s good to have tact, but don’t overdo it with your word choice.

Join 550+ subscribers and sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more tips like this.

The post Writing Tip 324: “Tack” vs. “Tact” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

September 7, 2017

Writing Tip 323: “Scotch Free” vs. “Scot Free”

No, people really don’t have an issue with your bagpipes.

If your name is Scott and you didn’t make it to the party, you could argue that party is Scott-free, but what about other uses of this phrase?

Is it about being sober? (Scotch free)

Is it about excluding anyone Scottish? (Scot Free)

I’ve heard some great thoughts about where this expression comes from—and what the correct version of this expression actually is—but let me put your mind at ease.

The correct spelling is “scot free.”

However, it has nothing to do with the Scots, as in the Scottish.

In medieval England, there was a tax called a “scot,” and if someone was able to avoid paying it, they would be getting off “scot free.” And over 800 years later, we still use the expression when someone gets away with something without being punished or penalized.

It has nothing to do with a lack of bagpipes, scotch whiskey, or people named Scott. Now you know.

Join 550+ subscribers and sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more tips like this.

The post Writing Tip 323: “Scotch Free” vs. “Scot Free” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

August 31, 2017

Writing Tip 232: “Complimentative” vs. “Complimentary”

I get it kid. This one annoys me too.

It sneaks into our language often enough that it deserves a moment in the spotlight—a moment in the spotlight before we hopefully make it completely disappear.

Remember, “complimentative” is not actually a word. Neither is “complimentive” or any other variation in spelling.

“Complimentary” or “complementary” are probably what you’re looking for if any of these other forms come out of your mouth.

That free toaster for being one of the first one hundred customers? It’s complimentary.

That lovely pairing of cheese and wine? They’re complementary.

That little old lady who always gushes about your eye color. She’s complimentary.

“Complimentary” and “complimentary” have their moments of confusion (see Get a Grip on Your Grammar for that break-down), but know that “complimentative” is never the right answer. Please take a moment to strike it from your vocabulary.

The world will appreciate it.

Join 550+ subscribers and sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more tips like this.

The post Writing Tip 232: “Complimentative” vs. “Complimentary” appeared first on Kris Spisak.