Kris Spisak's Blog, page 20

April 12, 2018

Writing Tip 345: “Spatter” vs. “Splatter”

This artist spatters paint; Jackson Pollock had a tendency to splatter. Do you know the difference?

Before April showers bring May flowers, there are a lot of puddles around. If you’re inclined to splash around in your galoshes, you need to know the difference between “spatter” vs. “splatter.” Neither are misspellings. And there is a difference.

Take a moment with this one. Any guesses?

Here’s a hint: “Splatter” appears to actually be an old portmanteau, a squishing together of “splash” and “spatter” in the vein of frenemy, brunch, or nowadays. Its first known use was in 1785.

Here’s what you need to know:

“Spatter” can mean to splatter—as in to spread, splash, or distribute in drops—and it can also be the spread out scattering of drops themselves.

“Splatter” follows nearly the same definition as a verb and as a noun, but the difference comes in the size of the drops. Remember, when “splash” and “spatter” combined, “splatter” came into existence. Thus, “splatter” is a bigger, splashier spreading of drops.

A drizzle might spatter the pavement. A car driving by a puddle will splatter someone walking down the sidewalk. When water splatters into your watering can from your spigot, a spatter of drops might cling to the side of the metal. When the sprinkler is turned on, it will splatter your garden (or you, if you decide to run through it).

Use “spatter” and “splatter” interchangeably if you wish. Most people do. However, if your meticulous nature enjoys subtleties of language, this one’s for you.

Happy writing, folks!

Join 650+ subscribers and sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more tips like this.

The post Writing Tip 345: “Spatter” vs. “Splatter” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

April 5, 2018

Writing Tip 344: “Loaves” or “Loafs”

The last thing you want is to get burned by your language use, especially when talking to a baker.

Half of a loaf may be better than none, as the saying goes, but for those lucky enough to have more than one loaf, do you know how to pluralize this noun?

Spellcheck isn’t going to help you.

Neither are similar words that end in “s.” “Knife” becomes “knives,” and “dwarf” becomes “dwarfs” after all. (Oh, it’s true. And I hear you, ghost of Tolkien. Stop messing with people on this one!)

There’s not always logic to English language spelling, but I think we all knew that.

Remember:

“Loaves” is the plural of loaf. If you’re sending a request to the baker, this is what you want to write.

“Loafs” is a present-tense form of the verb “to loaf,” as in to loiter, hang out idly, or aimlessly wander.

Okay, we’ve talked about loaves; we’ve talked about jam. I’m feeling a future post about butter coming on… Is it a pat or pad of butter? I’m just going to let that one hang out there. The answer is coming soon!

Hmm… apparently, I’m hungry when I write these posts.

Happy writing, folks!

Join 650+ subscribers and sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more tips like this.

The post Writing Tip 344: “Loaves” or “Loafs” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

March 29, 2018

Writing Tip 343: “Through the Wringer” or “Through the Ringer”

I hope this is the end of your ring/rung vs. wring/wrung confusion.

Let’s talk about “Ring” vs. “Wring” and “Rung” vs. “Wrung.” I think that’s the best place to start with this idiom that is misspelled so often.

I know spelling can sometimes put you “through the wringer” (or is it “through the ringer”?), but it’s time to pay attention and get this right.

If you’re wringing your hands because of an alarm bell ringing, I get it. I do. But there’s a difference that we need to understand. Your hands aren’t making any noise. Go ahead. Try it. I’ll wait.

Anything happen? (Knuckles popping don’t count.)

Remember:

“Ring” – When we’re talking about the sound, the different forms should be ring/rang/rung (e.g., a bell can ring right now; yesterday, the bell rang; if you want to make it a passive bell, it was rung). I could dissect parts of speech for you, but I won’t. I feel that yawn coming. I have faith you can get this right.

“Wring” – When we’re talking about twisting and squeezing, especially when there is something wet involved, add in that “w,” a good zigzagging letter to remind you of the crunching motion (e.g., you can wring your hands over this; yesterday, perhaps you wrung your hands over this; clothes could have been wrung out before being hung on the line).

And speaking of those clothes, let’s go back to the “through the wringer” or “through the ringer” conversation. If you feel like I’m putting you through the wringer, as in pressing and squeezing you uncomfortably, like clothes going through an old fashioned cranking mechanism to dry out laundry, then you’re making the correct association with this idiom.

No bells are involved, no cowbells, Liberty bells, jingle bells, bells that ring in the New Year, or otherwise. For whom the bell tolls is a totally different conversation. (And I’ll hold off this time about that “for whom” that I really want to dive into.)

Here’s hoping word choice decisions don’t feel like they’re putting you through the wringer, but if you feel like there’s language confusion ringing in your ears, I’m always here to help.

Happy writing, all!

Join 650+ subscribers and sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more tips like this.

The post Writing Tip 343: “Through the Wringer” or “Through the Ringer” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

March 16, 2018

Authors on Editing: Interview with Cheryl Pallant

Years ago, someone told me that taking a writing class with Cheryl Pallant would be unlike any workshop I’ve ever taken, and whoever that person was—I wish I remembered!—he or she was absolutely right. Tapping into the creative energy of your body as it moves stimulates the writing mind in ways I hadn’t experienced before.

Ask me, and I’ll tell you a story about the astounding mind-body connection of that first class with Cheryl seven years ago. But in the meantime, I’m honored to showcase author, teacher, and creative guru Cheryl Pallant and to share her thoughts on her editing process.

Cheryl Pallant is the author of several books of poetry and nonfiction, most recently Ginseng Tango, Her Body Listening, and Writing and the Body in Motion: Awakening Voice through Somatic Practice. Her stories, poems, and essays have appeared in places like New York Quarterly, Confrontation, and Fence and in anthologies like An Introduction to the Prose Poem. She teaches at University of Richmond and offers her somatic workshop, “Writing From the Body,” at retreats and art centers across the U.S. and abroad.

Q & A with Author, Poet, Dancer, and Healer Cheryl Pallant

Kris: Tell me about your editing process. Do you edit as you write, only after you finish, or a little bit of both?

Cheryl: Despite the temptation, I try to hold off on the editing until I’ve completed an initial draft.

Kris: You write so many types of projects. I’m not sure there’s much you haven’t tackled. How is editing poetry different from editing a book? And is editing a memoir different from editing other forms of non-fiction?

Cheryl: It helps to know that I write poetry, short fiction, long and short form nonfiction which includes a memoir. Each book, even those within the same genre, requires a different way of editing. Generally, I keep a two-step method in mind. There is Step One, which is writing an initial draft. Follow the flow of language and image. Minimize the amount of editing in this draft. Too much editing early on can kill the resonance and organic structure of the material.

Step Two is the editing, which is as important a part of the creative process as the first step which focuses on flow. The editing is where I flesh out the narrative and determine the difference between what’s in my mind and what’s on the page. I edit several rounds for rhythm, clarity, structure, and image, followed by edits for mechanics, spelling, and grammar.

I work a lot from a dreamlike place. In my poetry, it leads to word play, associative leaps, and precognitive knowing. The latter basically means that I don’t know what I’ve written until I read it. My poetry, specifically my first two books,

Uncommon Grammar Cloth

and

Into Stillness

, relied on a somatic writing technique that I was developing which focuses on my body primed by many years of dance and meditation.

I work a lot from a dreamlike place. In my poetry, it leads to word play, associative leaps, and precognitive knowing. The latter basically means that I don’t know what I’ve written until I read it. My poetry, specifically my first two books,

Uncommon Grammar Cloth

and

Into Stillness

, relied on a somatic writing technique that I was developing which focuses on my body primed by many years of dance and meditation.

In fiction, the dreamlike place lets the images of the movie appear. I sit back, watch, and record. Then I return later to add more description and plot development. My fiction is highly visual and surreal. Details are vital to make it believable.

The editing for my memoir, Ginseng Tango, required many structural changes, moving entire stories into new places, deleting some events and adding others. A challenge of a memoir is knowing which stories are pertinent to the book and which are best left out. The story deals with recuperating from divorce and adopting a new home in South Korea. I wrote quite a bit about the loss, but much of that writing never made its way into the book. It was essential for catharsis and expression but did little to forward the story of the book. A memoir writer has to know the difference. There’s got to be a focus, a narrative arc, and many elements found in fiction like plot. If a given scene doesn’t help the book, that material needs to be deleted. For instance, I was tangoing every week, but if I included every tale, it would have negatively weighed down the book.

I was fortunate to have kept a journal about my many experiences in South Korea, much of which made its way into Ginseng Tango. I called upon those journal pages to assist my memory, which has its own way of editing, a.k.a. forgetting. My focus was on the shape of the Ginseng Tango with all its substories.

Editing nonfiction has its own particular requirements. Clarity and linearity are paramount (compared to my poetry which is polylinear). The challenge of long nonfiction, such as my current book Writing and the Body in Motion about somatic writing, requires me to stay focused on what’s on the page and what ideas should follow logically. It’s too easy to conflate what’s in the mind with what appears on page. The mind readily fills in the blanks, whether those blanks are structural or something as simple as a spelling error. Shorter nonfiction has its own requirements. The deadlines involved in writing for a newspaper, which I did for twelve years, meant that the material got turned in by a specific time, even if I wanted to improve the material. It limited the amount of editing time. The writing required letting go, as all writing does in one way or another.

Kris: Thank you for that thorough break-down! I’m especially intrigued by your memoir-writing process. Memoir itself is a unique genre, because it’s so much more focused than an autobiography and it needs to speak to a core truth that can often be difficult for a writer to bring to the surface. Do you have any advice for memoir writers on how to revise their writing bravely, digging out their own authenticity and vulnerability?

Cheryl: Too often memoir writers try to write too broadly and write about too much of their life and omit the tastier nuggets. Ask yourself, Why would a reader want to read this memoir? What’s in it for the reader? A good writer can make even the most mundane of topics fascinating. A poor writer can make the most riveting stories dull. Aim for the middle. Focus on the story, but also how the story is told. Let your voice come through. Allow yourself to feel vulnerable. Be sure to combine truth-telling with craft.

I often write with a notebook at my side while I type away on the computer. The computer writing is the “official” manuscript. The notebook captures my thinking and raw material. On paper I tend to be more honest and sloppy. I express myself more freely. There’s something about the sensuality of my hand making contact with the page and pen. Different parts of my brain get engaged. Ultimately, much of the notebook writing ends up on the computer.

A test for memoir writing is whether or not you want to read the book. Will your older (or wiser or more creative) self benefit from reading it? How? Writing, in general, is a courageous act. Writing is a soulful activity that doesn’t receive widespread support. Yet those of us who write know how essential it is to write. It fosters self-examination, reflection, introspection. It’s an opportunity to find out the truth of who we are. We get to peek beyond the masks of culture.

A test for memoir writing is whether or not you want to read the book. Will your older (or wiser or more creative) self benefit from reading it? How? Writing, in general, is a courageous act. Writing is a soulful activity that doesn’t receive widespread support. Yet those of us who write know how essential it is to write. It fosters self-examination, reflection, introspection. It’s an opportunity to find out the truth of who we are. We get to peek beyond the masks of culture.

Kris: I love that, and it’s so true. It is essential and powerful for both the writer and the reader. For non-fiction, what is essential in a finished product for you? How does a writer get there?

Cheryl: I work a lot from feeling and intuition. Once I’ve said what needs to be said to the best of my ability, I stop. I come back and reread. I look for motivation to continue and to determine if the book is sufficiently shaped. When a book is done, the energy to work on it further disappears. That said, it’s important to distinguish between giving up and persisting through difficulties. One can be emotionally done, but the book may be incomplete. Taking a break from it and coming back later can suss out the difference.

Kris: That’s good advice, and on a language note, I like that word “suss.” It’s not an everyday word, but it fits your sentence and your meaning perfectly. For poetry, when you’re looking for just the right word or image and you know you’re not quite there yet, what do you do?

Cheryl: There are some poets who can spend months on an image or word. If the word or image is worth the struggle, if there’s something inherent about the process, go for it. I may set something aside for a day or week or month and return with more objectivity. I aim for beauty, knowing that spending too much time chasing perfection can mean that I write only one poem a year. I’ve seen myself destroy a piece with too much editing. Writing is a journey; I want it take me places, to different states of mind and being. I want the same for a reader, to have my words carry them somewhere. My poetry intentionally disrupts usual ways of reading and understanding. I want my words to bypass usual cognitive processes.

With all my writing and editing, I rely on somatic techniques. I step away from the computer (and pen and paper) and do some movement and focus on body sensation. It takes me away from my head where I can run in circles and refreshes the creative energy. It supports the emergence of the right word, a new phrase or scene. We know more than we think we know; it’s a matter of getting out of our way and letting the writing take over.

Kris: And in the midst of this, how do you ever know when you are done?

Cheryl: When the work no longer calls me to work on it. When it wants to step out into the world. I may come back and tinker, but generally I’ve moved on to my next new writing.

And when Cheryl says she’s moving on, you know that there’s real movement involved. There are so many approaches to the creative process that we have to remind ourselves that there is no “right” way to do this. It’s true for the crafting, and it’s true for the editing.

As for me, I cannot sit still during the editing process for a duration of much longer than twenty minutes. When I do, my work starts to become lazy. My blood needs to flow. My body needs to stretch before I can give a project my all. We all have our ways, but ignoring the role of our physical bodies in our creative space is to ignore a core creative tool in our possession.

Thank you so much for your time, energy, and wisdom, Cheryl Pallant, and happy writing, folks!

Join 650+ subscribers and sign-up for my monthly email newsletter for more interviews like this.

The post Authors on Editing: Interview with Cheryl Pallant appeared first on Kris Spisak.

March 15, 2018

Writing Tip 342: “Raise” vs. “Raze”

So, what’s the plan? Raise it? Or raze it?

You could raise the roof, or you could raze the roof. Just know there’s a big difference between the two.

Word pairs that sound the same (homophones) aren’t often antonyms, but “Raise” vs. “Raze” is one of those rare pairings where correct spelling is essential. Imagine a city planner walking into a meeting of community members with a proposal to raise a building between two historic properties. Now, imagine that same planner wanting to raze a building. Both are logical uses of these words, but the reaction of the crowd might differ dramatically.

Here’s the difference:

“Raze” means to demolish or erase.

“Raise,” in this circumstance, means to build or to heighten.

Of course, “raise” can also mean to lift up, to bring to maturity, to incite, to awaken, and multiple other definitions in both its verb and noun forms; however it’s the “raise” vs. “raze” confusion that is worth the second glance.

If you’re talking about construction, be sure you’re fully understanding the conversation in the room. And if you’re the one writing up that community proposal, make sure you’re spelling is accurate. The reaction of your audience depends on it.

As for “raising” or “razing” the roof, I don’t know what this quite means on the dance floor, but remind me not to stand near you if you’re doing the latter.

Happy writing, folks.

Join 650+ subscribers and sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more tips like this.

The post Writing Tip 342: “Raise” vs. “Raze” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

March 1, 2018

Writing Tip 341: “Naval Gazing” vs. “Navel-Gazing”

If you’re doing lots of naval-gazing, maybe you’re missing a sailor or maybe you’re a spy. But I’m guessing it might just be a typo if you’re writing about excessive introspection.

If you’re doing lots of naval-gazing, maybe you’re missing a sailor or maybe you’re a spy. But I’m guessing it might just be a typo if you’re writing about excessive introspection.

“Navel-gazing,” meaning the contemplation of your own thoughts, concerns, and existence (often to a self-absorbed degree), was first used in 1959, but oh, the spelling confusion since then.

If you’re using the idea in terms of meditation, the literal gazing upon one’s navel, there’s always the alternate term “omphaloskepsis,” literally omphalos (navel) + skepsis (the act of looking) in Greek, which is practiced by Eastern mystics; however this isn’t the most common use of “navel-gazing” today.

I recommend being careful with this word that slants toward the egotistical and making sure you understand what it often implies. It definitely shouldn’t imply anything about shipping vessels, submarines, or US Navy ports of call. The good news is that this typo isn’t one based in solipsism, but the bad news is that it doesn’t reflect well on you. A little more contemplation is needed, actually.

Now, I hope that’s settled. Got it?

Join 650+ subscribers and sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more tips like this.

The post Writing Tip 341: “Naval Gazing” vs. “Navel-Gazing” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

February 22, 2018

Writing Tip 340: Do you “nash,” “knash,” or “gnash” your teeth?

This guy? A serious gnasher. Especially when it comes to spelling faux pas.

You’ve heard it said, but do you know how to spell it?

This is another case of the English language being funky and you over-thinking your knowledge of the the nick of time, knots, gnats, and other words with spellings that sound like they should simply begin with the letter “n.”

Sometime after the first fifteenth-century usage of “gnash” your teeth—yes, that’s the correct spelling—the phrase became an idiom of its own. Not stopping too long over the fact that this word was derived from an alliteration of the common word of the time, gnasten—how fascinating is that?—you understand that when someone gnashes their teeth, no matter how you thought it was spelled, the person in question is angry, frustrated, potentially choleric, or otherwise incensed, inflamed, or infuriated.

It’s an action filled with tension. The spelling of it, however, should not be filled with tension.

Gnashing over the spelling of gnashing? I sure hope not. But if you are, I hope this settles it for you.

Happy writing, folks!

Join 650+ subscribers and sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more tips like this.

The post Writing Tip 340: Do you “nash,” “knash,” or “gnash” your teeth? appeared first on Kris Spisak.

February 17, 2018

Authors on Editing Interview with Jacqueline Woodson

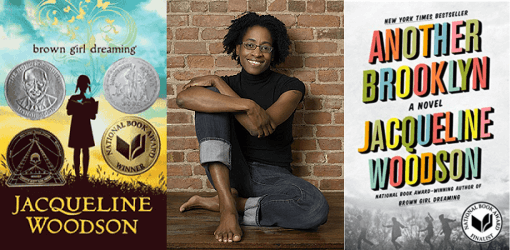

We all have certain writers we’re a bit in awe of, because of their stories and because of the power of their words. To be able to hash through the revision process with such an author is an absolute honor, and I’m thrilled to present you with the following Authors on Editing interview with National Book Award, Newbery Honor, and Coretta Scott King Award recipient Jacqueline Woodson.

Jacqueline Woodson‘s memoir BROWN GIRL DREAMING won the 2014 National Book Award and was a NY Times Bestseller. Her novel, ANOTHER BROOKLYN, was a National Book Award finalist and an Indie Pick in 2016. Among her many awards, she the recipient of the Kurt Vonnegut Award, four Newbery Honors, two Coretta Scott King Awards, and the Langston Hughes Medal. Jacqueline is the author of nearly thirty books for young people and adults including EACH KINDNESS, IF YOU COME SOFTLY, LOCOMOTION and I HADN’T MEANT TO TELL YOU THIS. She served as Young People’s Poet Laureate from 2014-2016, was a fellow at The American Library in Paris, occasionally writes for the New York Times, is currently working on more books, and – like so many writers – lives with her family in Brooklyn, New York.

Q & A with National Book Award recipient Jacqueline Woodson

Kris: Do you edit yourself as you write or after you have completed a first messy draft?

Jacqueline: Both—as I go along and then again when the draft is messy and in need of a closer, more cohesive look.

Kris: What does this revision process look like for you? Do you have sweeps that each have a different focus?

Jacqueline: Nope. I just write and rewrite and try to figure out what the heck my book is trying to say and how it’s trying to say it. I read everything out loud, and that gets me where I need to go.

Kris: I love the concept of figuring out what a book is trying to say, because you’re right—writing is such a process of discovery. I’m curious if this is also true for your characters. Writers often struggle with creating individuals that are unique and alive on the page. In your fiction, every character unquestionably has their own voice and personality. What can a writer do in their editing process to ensure each character is fully fleshed out and distinctive?

Jacqueline: I don’t think it happens in the editing process. I think it happens in your everyday living. If you don’t have an interesting and diverse crew to draw inspiration from, you’re not going to be able to tell interesting stories.

Kris: And speaking of interesting stories, In Brown Girl Dreaming, you (seemingly easily) poured yourself, your family, and American history onto the page for an exquisite result. I imagine there was so much that you also considered including but that ending up being cut in the end. How did you decide what to keep and what to remove from your final manuscript?

Jacqueline: I re-read and saw where the book was repetitive, where I’d said what I needed to say but maybe in a different way. Then I had to choose which one of those ways did I want to say that thing. I also took out stuff that didn’t move the story forward. Again, I figured out what the memoir was trying to say. It’s about a very specific moment in my childhood—my coming to consciousness. So any piece that didn’t do that was taken out.

Kris: Does your revision process differ between fiction and memoir?

Kris: Does your revision process differ between fiction and memoir?

Jacqueline: It doesn’t. Each book requires some kind of research and some kind of immersion. I try to dig in and focus, no matter what I’m writing.

Kris: Again, I’m just giddy that you’re chatting editing with me. Here’s my biggest question for you: What is the difference between okay writing and powerful writing? Do you have any recommended editing techniques to make the most of every single word?

Jacqueline: Read. Read widely. Read beyond what you love and know. You can’t be a writer without being a reader. Then have a life and live in it. You can’t write if you’re scared. Power writing comes from a certain fearlessness.

Kris: Is there anything you wish you knew about the editing process earlier in your career?

Jacqueline: I don’t look back that way. I think it’s a waste of time. Every moment of my life has led me to this moment, so what I knew then, the mistakes I made then, the drafts I wrote then—all of that got me here. So what I knew then, obviously, was just what I needed to know.

Kris: That’s answer such a powerful answer. It’s one every writer should try to internalize. Every phase of a writing career, every step of the process needs to be there before the next step can take place. Now, after all of this talk of editing, how do you know when a manuscript is officially done?

Jacqueline: When my editor says, “I think this is done!”

And what lovely words those are to hear!

I cannot thank Jacqueline Woodson enough for taking the time to talk editing with me. No matter what step of your literary life you find yourself in, happy writing, everyone.

Join 650+ subscribers and sign-up for my monthly email newsletter for more interviews like this.

The post Authors on Editing Interview with Jacqueline Woodson appeared first on Kris Spisak.

February 15, 2018

Writing Tip 339: “Bitter Cold” vs. “Bitterly Cold”

When local television news viewers start calling out meteorologists on their weather-specific grammar, you know people are in that end-of-winter, dark, gloomy, living-in-their-long-johns state of mind. Allow me to come to the defense of on-air weather personalities everywhere to say that “bitter cold” and “bitterly cold” are both correct.

When local television news viewers start calling out meteorologists on their weather-specific grammar, you know people are in that end-of-winter, dark, gloomy, living-in-their-long-johns state of mind. Allow me to come to the defense of on-air weather personalities everywhere to say that “bitter cold” and “bitterly cold” are both correct.

However, there is a difference to be aware of.

We all know of that words ending in “-ly” are often adverbs—and by this statement, golly, holy moly, I don’t mean to imply or shilly-shally around the dastardly, grisly folly that “-ly” words are only adverbs—moreover, this spelling difference is our first clue between “bitter cold” vs. “bitterly cold.”

“Bitter” is an adjective, which modifies nouns.

“Bitterly” is an adverb, which modifies adjectives or other adverbs.

Both “bitter cold” and “bitterly cold” can be correct because “cold” itself can be both a noun or an adjective.

If you’re talking about the cold, you could talk about the bitter cold of February.

If you’re talking about the cold weather, you could talk about the bitterly cold weather of February.

I don’t know if this breaks the ice on the on-air word choice conversation or whether suddenly it will all get more frigid. Either way, though, at least you know the difference.

Perhaps I should retitle this writing tip, “Is it Spring Yet?” What do you think?

Happy writing, folks.

Join 650+ subscribers and sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more tips like this.

The post Writing Tip 339: “Bitter Cold” vs. “Bitterly Cold” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

February 8, 2018

Writing Tip 338: “Often” vs. “Oftentimes” vs. “Oft”

Often, when I’m giving workshops, a hand raises into the air with a great question. Oftentimes, it’s a question that makes me pause and think.

Often, when I’m giving workshops, a hand raises into the air with a great question. Oftentimes, it’s a question that makes me pause and think.

Recently, the question was this: If we should try to make the most of our words and tighten superfluous language, why would you say “oftentimes” instead of just “often”?

It was a fabulous question, one I didn’t immediately have the answer to.

Here’s the answer:

Both “often” and “oftentimes” have been in constant use since the 14th century, sometimes even joined by their companions “oft” and “ofttimes.” “Oft” is usually only used in a hyphenated form these days, such as “oft-praised,” and “ofttimes” has fallen out of use; however, the other two versions live on with popularity.

“Often” is the more commonly used of the two, but sources seem to agree that there’s an old-fashioned style that is appreciated in “oftentimes” that makes it unique from “often.” It’s a tone difference, not a definition difference, though.

For most modern uses, always thinking about tightening up our language, making the most of every single word, “often” is the way to go, but there’s nothing wrong with a well placed “oftentimes.”

Now, is it time to bring back “ofttimes” for a really antiquated feel? Probably not. But next time someone questions your “often” vs. “oftentimes” usage, at least you’ll have an answer.

Join 600+ subscribers and sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more tips like this.

The post Writing Tip 338: “Often” vs. “Oftentimes” vs. “Oft” appeared first on Kris Spisak.