Kris Spisak's Blog, page 18

August 9, 2018

Writing Tip 357: Peter Piper Picked a What?

Peter Piper didn’t pick a “pack” of pickled peppers. Peter Piper picked a “peck” of pickled peppers. But have you ever wondered what the heck a peck was?

Peter Piper didn’t pick a “pack” of pickled peppers. Peter Piper picked a “peck” of pickled peppers. But have you ever wondered what the heck a peck was?

It’s a bafflement of generations. We practice the tongue twister, never teasing the meaning from the lines. But it’s time to elevate our comprehension.

In this situation, a “peck” is a term of measurement. There are four pecks in a bushel.

How much is a bushel? A bushel is thirty-two quarts. A bushel of peaches is about fifty pounds. A bushel of green peppers is about thirty.

So, if you’re imagining a bushel as a really big basket, imagine a peck as a significantly smaller basket.

The real Peter Piper seems to be a man named Pierre Poivre, who was a one-armed French colonial administrator during the mid-1700s known for stealing nuts from Dutch trade ships to plant in his garden. A bandit horticulturist? Maybe. True? Possible. But at least you now know how much the man—real or fictitious—picked (or maybe stole).

And if you’re curious about how much wood a woodchuck can chuck, we’ll leave that to another day, though I will remind you that a “woodchuck” is the same thing as a “groundhog.”

Do you have any other word questions from favorite tongue twisters or nursery rhymes? Let me know. I’m happy to help!

Join 675+ subscribers and sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more tips like this.

The post Writing Tip 357: Peter Piper Picked a What? appeared first on Kris Spisak.

Writing Tip 356: Peter Piper Picked a What?

Peter Piper didn’t pick a “pack” of pickled peppers. Peter Piper picked a “peck” of pickled peppers. But have you ever wondered what the heck a peck was?

Peter Piper didn’t pick a “pack” of pickled peppers. Peter Piper picked a “peck” of pickled peppers. But have you ever wondered what the heck a peck was?

It’s a bafflement of generations. We practice the tongue twister, never teasing the meaning from the lines. But it’s time to elevate our comprehension.

In this situation, a “peck” is a term of measurement. There are four pecks in a bushel.

How much is a bushel? A bushel is thirty-two quarts. A bushel of peaches is about fifty pounds. A bushel of green peppers is about thirty.

So, if you’re imagining a bushel as a really big basket, imagine a peck as a significantly smaller basket.

The real Peter Piper seems to be a man named Pierre Poivre, who was a one-armed French colonial administrator during the mid-1700s known for stealing nuts from Dutch trade ships to plant in his garden. A bandit horticulturist? Maybe. True? Possible. But at least you now know how much the man—real or fictitious—picked (or maybe stole).

And if you’re curious about how much wood a woodchuck can chuck, we’ll leave that to another day, though I will remind you that a “woodchuck” is the same thing as a “groundhog.”

Do you have any other word questions from favorite tongue twisters or nursery rhymes? Let me know. I’m happy to help!

Join 675+ subscribers and sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more tips like this.

The post Writing Tip 356: Peter Piper Picked a What? appeared first on Kris Spisak.

August 2, 2018

Writing Tip 356: “If I Was” vs. “If I Were”

Make a wish. Imagine the impossible. Just make sure you get your verbs straight.

If I were a rich man… If I were a boy… Whether you want to start this “if I was” vs. “if I were” conversation with Fiddler on the Roof or Beyoncé, it’s a conversation we need to have.

Let’s talk unreal conditionals and the subjunctive mood. Actually, no, let’s not. That doesn’t sound very exciting.

Let’s talk music and musicians who get grammar. More exciting? Almost. But bear with me.

You know that if you went to see your favorite band yesterday, you’d use verbs like this: “I was there”; “it rocked”; “he was bummed to miss that solo”; “you were amazing on the drums.”

But if it wasn’t a real show—a pretend show, a show you’re dreaming about existing but that doesn’t, a hypothetical or unlikely show—you’d swap up your word choice like this: “If I were there”; “if he were there”; “if they were there.”

I were… are you cringing? Deep breath. It’s what you need here, whether you like it or not.

In unreal conditionals (darn it, I didn’t mean to let that slip in again!), you’ll often see words like “would” or “ought to.“ For example, “If asked, I would step up to the stage” or “If given the opportunity, she would have blown them all away.” But when you need the verb “to be” following that “if” in these unreal situations, it always remains “were,” even when you’re working with subjects like “I” or “he,” which typically pair with a “was.” This leads to phrases like “if I were lead singer” and “if it were my birthday.”

If I were a carpenter… If I were your woman… Personally, I’m impressed that so many artists get it right. Then there’s Gwen Stefani, who went rogue in If I Was a Rich Girl, a remix of the Fiddler on the Roof classic. The gender swap, I get, but the verb swap…? Why, Gwen, why? You just confused a generation.

Is it because the “if I was a rich girl” isn’t a hypothetical in her situation? She is indeed rich, so it’s not an unreal conditional? It’s real? Honestly, I think it’s a mistake, but we can pretend she’s just going to grammar levels over all of our heads.

As for the rest of us, know your “if I was” vs. “if I were” and own it. Whether you’re on stage, in the recording studio, or maybe just belting out your favorite jam in the shower.

Happy writing, folks.

Join 675+ subscribers and sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more tips like this.

The post Writing Tip 356: “If I Was” vs. “If I Were” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

July 29, 2018

Authors on Editing: Interview with Dean King

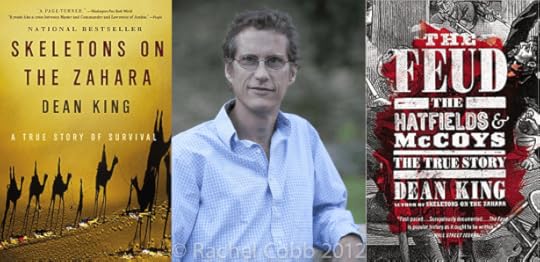

People don’t always think of wordsmiths as adventurers, of book writing as exploration, or of fine-tuning a manuscript as a process of discovery, but if that’s the case, they probably haven’t heard from award-winning, bestselling, documentary-producing author Dean King.

From the subject matter he chooses to investigate to his extensive research to the captivating storytelling that results, Dean is a master writer. I’m thrilled to welcome him to my Authors on Editing interview series.

Dean King is an award-winning author of nine non-fiction books. Dean has chased stories across Europe, Asia, Africa and now Appalachia. His goal is to draw you into a nuanced and accurate historical narrative that allows you to live with the characters, to feel their pain, striving, and joy, and to grow with them. He rides the camels, climbs the 14,000 foot passes, walks the yard-arms, and tracks down far flung sources. (He was shot at beside the Tug River while researching his latest book, THE FEUD.) Then he writes and edits until his knuckles have no skin, his elbows ache, and his family is looking for him, all to give you pleasure in lean and meaningful prose. If he makes you eager to take his book to your favorite easy chair or crawl into bed and curl up with it, he’s happy. If you learn something or feel changed, then all the better. Dean’s writing has appeared in Granta, Garden & Gun, National Geographic Adventure, Outside, New York Magazine, and the New York Times. He is a contributing editor of Virginia Living and a nationally known speaker, who has been the chief story-teller on two History Channel documentaries.

Q & A with Award-Winning Author Dean King

Kris: I’ve found everyone seems to have a different approach to editing. After you finished your first draft a project, what did you do next? Okay, after the beer or nice glass of wine (scotch?), what does your revising process look like?

Dean: There is no first draft. The whole thing is a living, palpitating, ever-changing beast. When you finish the end, you have to go back and adjust the beginning. When you adjust the beginning, you have to go back and tinker with the center. The trick is to get the beast you have created to a comfortable, conscious equilibrium, where its heart is beating on its own, and then try to run away. It will chase you, and it’s faster than you are.

Kris: Oh, I absolutely know that feeling. So, if there is no “first draft,” what does this editing process look like for you?

Kris: Oh, I absolutely know that feeling. So, if there is no “first draft,” what does this editing process look like for you?

Dean: I like to think I layer. I layer in the sources, and each time I layer in a new one, it effects all the ones that came before. It’s a laborious but beautiful process that lets all the documents and research and all the previous tellings of events contend and wrestle with one another. In the end, it is my blending, shaping, and interpretation of these things that becomes my narrative.

Kris: Has this process evolved between your first book and your more recent publications? Or more specifically, what have you learned works really well for you, and what doesn’t?

Dean: When you first get started, there’s no way to know how much time and effort it will take you to write a commendable book, because you have never done it before. It’s so much work and time that it is not imaginable. When you can’t look at the thing any longer, then go find another source and some new facts that carry you back into the story. Revise, reread, revise, until someone makes you stop.

Kris: Your writing explores stories across cultures that are often not your own. How do you review your work in regards to being authentic and telling the truth of that culture, place, and time?

Dean: Go there, or as close as you can, spend time with people, and be prepared with knowledge. You may think you cannot travel back in time, but you will be surprised. When I went to the Sahara [researching Skeletons on the Zahara ], the things I experienced were exactly the things I thought were no longer part of the culture. And the facts I set out to verify and thought I could were unascertainable. The story I most often tell about this is when I fell off my galloping camel, and my guide told me I was okay because camels are sacred and those who fall from them are never hurt. Although I was checking for cracked bones, I had a smile on my face, because Riley had reported that when he fell from his camel he was told the exact same thing in 1815. It not only verified a part of his narrative that I was unsure of, but it connected us across all that time in a shared experience. In fact, everything that went wrong on my expedition, which was only three weeks after 9-11, was everything that went right. If the journey had gone exactly as I had planned, it would not have taught me nearly as much about Riley’s hardships as the hardships I experienced ultimately did. Challenge your own preconceptions and prejudices. Question what you know—or think you know. Be open to transformation. That is when you can transcend from reporter to storyteller.

Kris: When you’re looking at a specific scene in your text and ensuring that its setting vivid and alive for your reader, what do you find yourself adding in? And/or what do you find yourself taking out?

Kris: When you’re looking at a specific scene in your text and ensuring that its setting vivid and alive for your reader, what do you find yourself adding in? And/or what do you find yourself taking out?

Dean: When writing a scene, it is important to build it one moment at a time. The writer has to stay in the moment and not give away what’s coming next. I also find myself looking for the right place to stop. “Elison Hatfield grasped the stone in one hand. He lifted it, and with all the strength he had left, he brought it down on Tolbert McCoy’s head. He heard the gut-wrenching crack of rock on skull as the blow hit home.” That’s a good place to stop. Hatfield has been stabbed and bleeding just before, and there’s a knife in his side. McCoy has now suffered a brutal blow, but what is the result? Well, you have to read on into the next chapter to find out.

Kris: Right. Telling a story is one thing, but writing a page-turner is something you’re a master of. After your initial ideas are on the page, how do you elevate your writing in regards to pacing and suspense?

Dean: I visualize it like a movie. What are the active scenes that can be described in a gripping way? End a chapter as per above, and then at the beginning of the next chapter feed the reader context, history, science, whatever you want to feed them that might otherwise slow the narrative down. They will fly through it, absorbing some, to get to find out what the result of the action at the end of the previous chapter was. My favorite example of this is in two of the Aubrey-Maturin books by Patrick O’Brian. The sea captain Jack Aubrey is sent on a mission in one book but ends up in a battle with a pirate ship before he can take the town he was sent to take. The book ends with a rousing sea battle, but you still don’t know if his actual mission was successful. At the beginning of the next book, where you expect to find out quickly, O’Brian doesn’t tell you. It’s not until a hundred pages in that a spy looking down from a tower tells a companion, “There’s Aubrey, the captain who . . . ,” that you find out (I had to cut the spoiler). O’Brian was having great fun with that, and I admire his constraint.

Kris: Now, what does your editing process look like in regards to double-checking your extensive research?

Kris: Now, what does your editing process look like in regards to double-checking your extensive research?

Dean: Dig as deep as you can and get to the closest, earliest sources you can find and then double-check them as often as you can. That’s one reason why writing a lasting book takes so long. You really have to get so steeped in your subject that you know it better than anybody. Early histories may be wrong. Later histories may be wrong. Get to documents whenever you can, but even documents may be wrong. Ultimately, you are the interpreter of the facts as the evidence seems to present them. With the Hatfields and McCoys in The Feud , every clash is told from opposite points of view. So interpreting that and doing it in a transparent way is very important. With Unbound , every detail is interpreted through a political lens, so you have to be constantly vigilant on how you present the “facts.”

Kris: I like that you put “facts” in quotation marks. They do so greatly depend on your source. Beyond interpreting your research and being thoughtful in its presentation, what do you wish more writers knew about the writing and editing of narrative nonfiction?

Dean: You can never read your own work in progress too many times. Relentless rewriting and editing is essential. Every sentence should be a good one. Every paragraph should be tight. It is a big responsibility to lay claim to the telling of an historical event or a life, and it is an amazing privilege to be handed a big chunk of someone’s time; honor that responsibility and that gift by putting everything you have into your work. It’s important.

Kris: Is there a difference between editing narrative nonfiction versus biography?

Dean: I think biographies should read like good narrative nonfiction. I wouldn’t edit them differently. Insignificant details should be omitted from both. The trick is figuring out was is insignificant.

Kris: When do you know your book is finally done?

Kris: When do you know your book is finally done?

Dean: In some ways a book is never really finished. It’s part of you for life, and you are its custodian for your time on earth. Deadlines are nice, and when the publisher starts charging you for any more changes, that’s when you know you have to stop. Ha. True. After writing my Patrick O’Brian biography and having it published in hard cover and serialized in four full pages in the Daily Telegraph, I received a letter from a woman who had had an affair with O’Brian at a particularly important point in the narrative. She sent a photograph of them together. I interviewed her by mail and added another thousand words to the paperback to cover that. Eventually, I want to let go though, and I do. I don’t want to be the world’s expert on all my topics for all times. Other people devote their lives to these things and to preserving the books, document, houses and other things of history, and I want to keep moving and tell other great stories. But I do keep files on all my books with correspondence and updates.

Being a successful author takes work. That’s the side of the writing life we can’t forget. Doing the work and doing it well takes time, endurance, and fortitude. But there’s also the adventure of the process, discoveries to be made in every stage that make a profound difference on a project and on you as the writer personally. Even falling off camels can be a positive step forward sometimes. We all have to find our own rite of passage. Whatever yours may be, good luck with it.

Thank you so much, Dean King, for taking the time to talk about your craft with me, and happy writing, folks!

Join 675+ subscribers and sign-up for my monthly email newsletter for more interviews like this.

The post Authors on Editing: Interview with Dean King appeared first on Kris Spisak.

July 27, 2018

Writing Tip 355: “Inflamed” vs. “Enflamed”

When the discussion gets heated, are tempers “inflamed” or “enflamed”? Is there a difference? Which one should you use? Some days, it might feel hard to keep yourself in check, but before passions flare (or is it “flair”?), let’s settle this once and for all.

When the discussion gets heated, are tempers “inflamed” or “enflamed”? Is there a difference? Which one should you use? Some days, it might feel hard to keep yourself in check, but before passions flare (or is it “flair”?), let’s settle this once and for all.

The big question is, should we start by going back to Middle English (arguably the first English form of this word) or should we go all the way back to Latin? In the 1400s, the word “enflamen” came from the Anglo-French word enflamer, but just before you want to call it a win for the “en-” form, let’s travel further (not farther) back in time to the Latin root. Now, we see where the confusion started, because this root is inflammare. Suddenly, you’re thinking about “inflammable,” “inflammation,” and a number of other words that share this same origin, all with the “in-” prefix

Thus, in short, there have been centuries of confusion and waffling between the two spellings, but since roughly 1600, “inflamed” has been the more popular form. Many dictionaries and spellcheck programs will let you get away with “enflamed,” but know that “inflamed” with that “i” is the standard spelling.

Who knew there were so many word confusion issues surrounding the idea of fire? “Lit” vs. “Lighted.” “Immolate” vs. “emulate.” “Burned” vs. “burnt.” I guess this is just one more for the list, fighting fire with grammar-checked fire.

Happy writing, everyone!

Join 675+ subscribers and sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more tips like this.

The post Writing Tip 355: “Inflamed” vs. “Enflamed” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

July 18, 2018

Writing Tip 354: “Heroine” vs. “Heroin”

Don’t give your heroine the short shrift by calling her the wrong name (and while you’re at it, don’t give her a “short shift” by mixing your words)

Oh, I see you, letter E, making your big difference between these two words. The question is, does everyone else see you too?

When I stumble upon a writing blog or a Twitter post, where someone is talking about the “heroin” of their novel, I just want to chime in. Not because I’m an editor. No, I’m sure it’s not a typo. I’m sure that wordsmith just feels like writing is such a drug, an addition, something for better or worse you just can’t shake, something that gets into your blood stream and makes you buzz sometimes, makes you giddy and exhilarated, something that makes you hallucinate and hear voices of characters when reality tells you they just aren’t there…

Or maybe it is just a typo. And maybe that writer meant to say “heroine.” With an E. That tricky, tricky letter E that sometimes likes to fall off of words just to drive us mad.

Please remember the difference between your “heroine” and your “heroin.” Actually, no, strike that. I’m really hoping “your heroin” isn’t part of this conversation. Just know the difference. And say no to drugs.

“Heroine” is the female version of “hero.” Honestly, I’ll argue this word is past its prime and that “hero” fits both genders nowadays; however, knowing the correct spelling has some value.

“Heroin” is an opioid that’s commonly a recreational drug. It’s known for its euphoric effects.

Ah, so maybe that’s my clue. Writing’s not just those euphoria moments. It’s a prickly passion. Heroin isn’t the right metaphor, I suppose.

But no matter your relationship with words—love them, hate them, or fighting addition to them—at least know who to turn to when times get tough. A heroine can help. I’d argue against the other option.

Happy writing, folks!

Join 675+ subscribers and sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more tips like this.

The post Writing Tip 354: “Heroine” vs. “Heroin” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

July 13, 2018

Writing Tip 353: “Right” or “Rite” of Passage

Should you take a right? Or is the journey itself a rite? I could write an entire story about the muddle of these words—right, rite, write?—but I’ll stop here.

Discussions of “Rights” are sometimes tricky. Discussions of “Rites” are often equally complicated. Discussions of why I capitalized both of those words might be intimidating. But discussing the differences between “rights” and “rites” shouldn’t be a matter that mystifies us.

Remember:

“Right” can mean correct; it can mean the opposite of left. It can also mean what is just, fair, and proper, or the embodiment of something that you can claim as your due.

“Rite” is often (but not always) used in a religious sense, as a ceremonial act or initiation that one goes through.

Once these definitions are sorted out, we can tackle the question of a “Right” or “Rite” of Passage.

A “Rite of Passage” is a moment or ritual that acts as a crossover to a new stage of life. A religious confirmation is a rite of passage, as is marriage, as is a middle school grilling in grammarian jargon that may or may not shape your excitement about the English language. This is a phrase that was first used in 1909, but I’m guessing it wasn’t because of that last example. Let’s all take a deep breath and move past the memory of that last example. I know many of you have lived through it.

A “Right of Passage” doesn’t come up nearly as much as the first. It could refer to the ability or permission to cross through a certain territory. In fantasy writing, it might include trolls that are blocking a bridge. Or, in other writing, it might be a typo.

Yes, you can get this right. Correct language use is not a rite of passage—the understanding of “moot” vs. “mute” or “hone” vs. “home” as a gateway to adulthood?—but maybe it should be. Personally, I like the idea. What can we do to make that happen?

Happy writing, folks!

Join 675+ subscribers and sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more tips like this.

The post Writing Tip 353: “Right” or “Rite” of Passage appeared first on Kris Spisak.

July 2, 2018

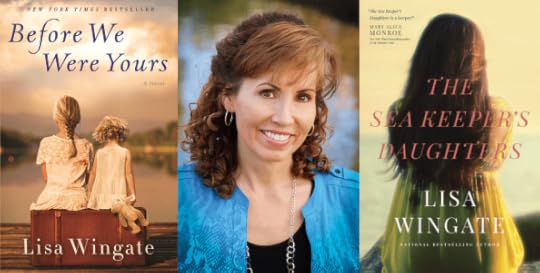

Authors on Editing: Interview with Lisa Wingate

Some writers pen works you fall head-first into, making you not want to climb out until the very last page. Lisa Wingate is one such author, who has been able to achieve this feat time and time again. Lisa’s novels have been translated into over thirty-five languages, and on top of her skills as a novelist, the group Americans for More Civility, a kindness watchdog organization, selected Lisa along with six others as recipients of the National Civics Award, which celebrates public figures who work to promote greater kindness and civility in American life.

For these reasons, and many more, I am absolutely beside myself to present the following interview, which is full of inspiration and valuable writing and editing advice.

Lisa Wingate is a former journalist, inspirational speaker, and New York Times Bestselling Author of thirty novels. Her work has won or been nominated for many awards, including the Pat Conroy Southern Book Prize, the Oklahoma Book Award, The Carol Award, and the Christy Award. Her blockbuster hit, Before We Were Yours remained on the New York Times Bestseller List for over ten months, was Publishers Weekly’s #3 longest running bestseller of 2017, and was voted by readers as the 2017 Goodreads Choice Award winner for historical fiction. Before We Were Yours has been a book club favorite worldwide and to date has sold over one million copies.

Q & A with Bestselling Novelist Lisa Wingate

Kris: When you hear the word “editing,” what is your gut reaction?

Lisa: After 30 novels, “edit” doesn’t strike the fear in my heart that it once did. I remember those early editing letters with the returned manuscript all red-penciled (on paper back then, just imagine!) with comments, questions, suggestions to cut this and that, rearrange chapters and/or scenes, cut out a character or add one. My heart would rebel. Eventually, I learned that if I’d just let it all settle a bit, the answers would come. I’d know how to fix the issues, satisfy the editorial suggestions, and sometimes work around them. Mostly, I learned that, while having someone else step into your story and critique it, editing (beyond self-editing, I mean) is necessary. It makes the book better, the story more complete, and more satisfying for all the eyes that will take it in when the book hits the shelves.

Kris: Tell me about your process. Do you revise as you write?

Lisa: Very little. I write a messy first draft, then edit after I have the whole story on paper. The first draft is just me telling the story to myself. When I edit it, I’m shaping it into something others can read. If I hit a rough spot as I’m working, I might take a little break, turn on some music, brew a cup of tea, or even grab my iPhone and take a walk or move to the porch, but once I’ve “reset,” I make myself write on until I reach my goal for the day. Sometimes, I’m thinking, “This is junk.” But the thing about junk is, you can always revise it later. Sometimes when I read back over the scene later, it’s actually not bad, and I don’t end up tweaking it much.

The main thing for me is to get the first draft on paper—have I said that already? Once I know the whole story, it’s much easier to shape the bits and pieces.

Kris: Oh, yes. We all have those “this is junk” moments. And we’ve all got to push through. Getting that first draft down is so essential. Thank you for saying that. So, on a macro-level review, looking at story structure and whether what you have down works, what is it that you look for? Would you walk me through how you elevate your structure to make the most of every chapter and every scene?

Lisa: Even though I’m not a big plotter and I will discover much of my story as I work, I always work according to Three Act Structure. It gives me the skeleton on which to hang the flesh of the story. I’m always working with the three act plot points in mind as I write. Every writer’s process is different, but for years I taught a workshop featuring a very simplified Three Act Structure outline. While there is no “magic bean” for writing a great story, it’s helpful to understand how the three acts of a story break down. I don’t teach the workshop anymore, but the worksheets from the class are on my website.

Kris: That is an amazing resource! I appreciate you sharing it. Now, when it comes to historical research, I’m sure there’s so much that you find that is utterly fascinating but that has to be taken out of the final draft of the book. I know this is a problem I sometimes have. How do you decide what can stay in and what has to go?

Lisa: I’m fascinated with history. I love finding a little-known historical gem and thinking, who would have lived this event? Where is the story in this? In the case of Before We Were Yours, I was up in the middle of the night, pulling a deadline. I had the TV on, but with no volume. An old episode of Investigation Discovery’s Deadly Women cycled through and caught my eye. There were images of an old mansion with a front room filled with bassinets and babies. Crying babies, laughing babies, babies who were red-cheeked and sweaty-faced and sickly looking. I turned on the volume (writers love a good distraction) and immediately became fascinated by the bizarre, tragic, and startling history of Georgia Tann and the Tennessee Children’s Home Society. I was shocked by how recent her adoption-for-profit operation was, operating from the 1920s until 1950.

I knew I had to write about this, and it occurred to me that what hadn’t really been told were the stories of the children. Mostly, I focused on that—the experience through their eyes and what parts of it would have mattered to them. What they would have seen, experienced, felt, heard, etc. when they crossed paths with Georgia Tann’s spotters and were suddenly foisted into a holding home, awaiting adoption-for-profit. I wanted my readers to be caught up in the story, the mystery, the danger. Any piece of the history that enhanced that, I tried to incorporate. Anything that slowed that down, I left out.

There was much more that could have been told in terms of the history, but a novel isn’t a history book. It’s the tale of one character’s journey (or multiple characters’ journeys). Anything not relevant to that journey, anything not propelling it along, should be left out.

Kris: That’s wonderful advice, hard to follow sometimes in a rough draft, but crucial in a final manuscript. Turning to another story element, how do you revise your dialogue so that you know it rings true to both your reader’s ear and the truth of the character voice?

Lisa: I develop a lot of my dialogue as I’m dictating into the iPhone. When you speak it and then answer yourself, it sounds genuine (and a little crazy, so this isn’t something to do at the local Starbucks). It’s a lot like playing Let’s Pretend in childhood, imagining yourself as a character, talking and living the story. The toughest part of dialogue for me has to do with dialect, which can be tricky. It’s a matter of adding enough dialect to make the characters real, without adding so much that they’re speaking in code. Regional phrases are interesting too. An editor once red-penciled the phrase “she had a rigor.” In the South, people have rigors all the time. Not so on the East Coast. My editor had never heard of it. We engaged in a bit of discussion and decided that “conniption fits” are universal and understood by readers everywhere.

Kris: I’m just imagining you sitting on your front porch having conversations with yourself, phone recording it all. I love it. Some people have that natural ebb and flow to their speech that translates so well onto the page. You’re clearly a natural storyteller. Here’s my last question for you: what is your best editing advice for newer writers?

Lisa: If you receive a particular critique from one person—even an agent or editor—be skeptical unless there’s a book deal on the table. Really think it through. Does it make sense? Will it enhance your story or make it better? Could it be a matter of opinion? If you’ve received similar commentary from multiple sources, it’s time to ask the really hard questions and think about revising your story.

Hard questions. That’s really what the best editing brings outs, and with the close examinations of those hard questions, your story becomes better. I love how Lisa notes that all advice isn’t to be automatically followed. It’s a matter of finding the greater truth of your story and your characters, what works for you as a writer and for your readers—whether it’s that Southern expression that may or may not be universally understood or that fascinating history that weaves into (but not necessarily beyond) your plot.

Sometimes editing makes all the difference, self-editing and external editing. Both are crucial pieces of the writing process.

Thank you so much, Lisa Wingate, for taking the time to talk editing and craft issues with me. I’ve been truly honored to have you join our Authors on Editing conversation.

No matter what everyone is working on, happy writing, folks!

Join 675+ subscribers and sign-up for my monthly email newsletter for more interviews like this.

The post Authors on Editing: Interview with Lisa Wingate appeared first on Kris Spisak.

June 21, 2018

Writing Tip 352: “Work in Progress” vs “Work in Process”

We as a society, as a nation, as people on this earth are works in progress, no? And, wow, do we need to get to work.

What does the ever-popular #wip stand for? Or maybe I should ask, what does it stand for to you?

This is a tricky answer, because it depends on when in the past two hundred years you’re curious about, which side of the Atlantic you’re on, or if you’re in the manufacturing or finance industries.

Yes, these responses matter.

The good news is that whichever “WIP” you believe to be correct, you can get away with it. Both are commonly used in the present day and largely acceptable when talking about a project that is on its way toward completion.

“Works in progress” came first, has always been the preferred phrase in British English, and is considered the standard form, no matter where you might be across the globe today.

“Works in process” had a popularity surge between 1915 and 1960 according to Google’s Ngram Viewer, but it was apparently a short lived American fad.

Writers or artists might have a work in progress. DIYers often have lots of works in progress. Construction workers, business teams, and almost any group you could name can easily refer to their WIP.

Notice the plural spelling with “works” gaining the additional “s” not “progress,” and notice that no hyphens are necessary between these three words.

It’s true that in some production industries, both “works in progress” and “works in process” seem to be popular phrases, and they seem to imply different meanings. It comes down to the duration of the production cycle, according to Investopedia, but I don’t think the average person really needs to think about this nitty-gritty understanding.

When you look in the mirror, maybe you think you’re a work in progress, and you know what? I think we always should be. We should continue to explore the world around us, attempting new artistic expressions and innovative solutions, empathizing with the many people around us, and diving in to our works whatever they might be. Our command of the English language is simply one of these pursuits.

I’m honored to be a small part of your continued education.

Good luck with all of your WIPs, everyone.

Join 675+ subscribers and sign-up for my writing and editing email newsletter for more tips like this.

The post Writing Tip 352: “Work in Progress” vs “Work in Process” appeared first on Kris Spisak.

June 14, 2018

Writing Tip 351: “Soul of Discretion” vs. “Sole Discretion”

Kris Spisak.

Kris Spisak.