Daniel Orr's Blog, page 61

May 27, 2021

May 27, 1905 – Russo-Japanese War: The start of the Battle of Tsushima, where the Japanese Navy destroys the Russian Second Pacific Fleet

On May 27, 1905, the Japanese Navy engaged a Russian fleetin a two-day battle (May 27-28, 1905). In the aftermath, the Russian fleet wasannihilated, with 10,000 Russian sailors killed or captured, 21 ships sunk,including 7 battleships, and of the 38 Russian ships that started the voyage,only 3 managed to reach Vladivostok. Japanese losses were 700 dead or wounded, andonly 3 torpedo boats sunk.

Background By March1905, Japanese forces had gained control of the entire southern Manchuria,including Port Arthur,the strong Russian outpost. But they hadfailed to annihilate the Russian Army (which remained relatively potent despitethe high losses). Because of seriouslogistical problems, the Japanese Army decided to abandon plans to advancefurther north.

(Taken from Russo-Japanese War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia – Vol. 5)

Despite the series of battlefield defeats, Tsar Nicholas IIcontinued to believe that the Russian Army would prevail eventually in aprotracted war. The now completedTrans-Siberian Railway could transfer more troops and weapons to the Far East. Butthese hopes would be dashed in the Battle of Tsushima.

In October 1904, while the Japanese Third Army was yetbesieging Port Arthur, Tsar Nicholas II orderedthe Russian Baltic Fleet, which was led by eight battleships, to head for Port Arthur and break theJapanese naval blockade, and reinforce the Russian Pacific Fleet. The Russian Baltic Fleet, soon renamed theSecond Pacific Fleet, then embarked on a seven-month (October 1904-May 1905)33,000-kilometer voyage half-way around the world by way of the Cape of GoodHope, and around the southern tip of Africa. The Russian fleet was forced to take thismuch longer route after being denied passage across the Suez Canal by Britain following the Dogger Bank incident. In thisincident, which occurred in the North Sea inOctober 1904, the Russian fleet fired on British trawlers, mistaking them forJapanese torpedo boats. The incidentsparked a furious British government protest that nearly led to war between Britain and Russia.

In January 1905, while yet in transit, the Russian fleetreceived information that Port Arthurhad fallen. As a result, it was instructed to head for Vladivostok instead. By May 1905, the Russian fleet had enteredthe waters south of the Sea of Japan, and while traversing the Tsushima Strait,located between Japan and Korea,the fleet was spotted by a Japanese ship, which then alerted the JapaneseNavy. In the previous months, theJapanese had followed the progress of the Russian fleet’s voyage, and thusprepared to do battle with it in a decisive showdown.

The Battle of Tsushima sent reverberations around the World– an Asian nation dealing a crushing defeat on a European power. In Russia,Tsar Nicholas II abandoned his hard-line position against Japan. On June 8, 1905, one week after the Tsushimabattle, Russiaagreed to negotiate an end to the war.

May 26, 2021

May 26, 1940 – World War II: Allied forces begin evacuation from Dunkirk, France to southern England

On May 26, 1940, the British High Commandimplemented Operation Dynamo, the Alliednaval evacuation from Dunkirk, with the firsttroops, numbering 28,000 being evacuated by ships to southern England on that day. Then the Allies received a stunning blow whenon May 27, Belgian King Leopold III asked the Germans for an armistice, and thenext day, May 28, 1940, the monarch formally surrendered the Belgian Army. The sudden Belgian capitulation exposed the Dunkirk perimeter’swestern flank, seriously jeopardizing the evacuation. However, fierce resistance by 40,000 Frenchtroops, the trapped remnants of the French 1st Army at Lille against four German infantry and three armoreddivisions (comprising 110,000 troops, 800 tanks) stalled the German advancethat allowed 70,000 more Allied troops to escape to Dunkirk. But as a result of the 4-day siege at Lille, the French 1st Army wasdestroyed.

(Taken from Battle of France – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe – Vol. 6)

The Dunkirk evacuation, lasting fromMay 26 to June 4, 1940, was successfully carried out: under fierce, constantGerman air, artillery, and tank fire, and a gradually shrinking perimeter asthe Germans broke through the defensive lines, hundreds of small vessels,including privately owned fishing boats and pleasure craft from southern England, were used to assist ships of theBritish Royal Navy to evacuate Allied troops from the harbor and beaches of Dunkirk. Of the 222 British Royal Navy vessels and 665other requisitioned boats that took part, 6 British and 3 French destroyers, 24smaller Royal Navy vessels, and 226 other ships were lost. Also, 19 other British destroyers weredamaged, as were over 200 other British and Allied vessels. On June 4, 1940, German forces broke throughthe last defense line and entered Dunkirk,capturing some 40,000 French troops who had failed to make the evacuation. In total, 331,000 Allied troops wereevacuated, of whom 192,000 were British and 139,000 were French. But the British Army left behind all itsheavy weaponry and equipment: 700 tanks, 45,000 trucks, 20,000 motorcycles,2,500 artillery pieces, and 11,000 machine guns.

The German Army now turned itsattention to the south, to the conquest of Parisand the rest of France. With 140 divisions (130 infantry and 10panzer) in a reconfigured Army Groups A and B (and Army Group C inside Germany facing the Maginot Line),the Wehrmacht massed along a 600-mile front along the Somme and Aisne riversstretching from Sedanto the Channel coast (the French Weygand Line). Facing the Germans were 64 French divisions comprising three ArmyGroups, including 110,000 French soldiers who had been evacuated in Dunkirk but were repatriated to Francevia Brittany and Normandy. Also arriving were two other Allied infantry divisions, one British andone Canadian, supplementing one British infantry and elements of one armoreddivision as well as Czech and Polish formations already in France, a combined total of 173,000troops.

The debacle in Belgium greatly depleted French militaryresources: France’sbest units, comprising over 60 divisions, were lost, as were elite tankformations and a considerable number of heavy equipment and weapons. However, increased moral and resolve sweptthrough the remaining French Army: officers and men were fighting for France’ssurvival, supply and communication lines were closer, and army commanders andsurviving units had gained battle experience. General Weygand implemented a “hedgehog” defense-in-depth network of mutually supporting fortifiedartillery positions, supported by armor and air cover, aimed at inflictingheavy losses to the attacking German forces.

On June 5,1940, German forces launched Fall Rot (“Case Red”),the invasion of Paris and southern France, but met fierce resistance at theSomme and Aisne, where their initial attemptsto cross the rivers were repulsed with heavy German armored losses. In one instance at the Aisne,a German armored assault lost 80 of its 500 armored vehicles. But with the Luftwaffe’s air superioritybeing brought to bear, the Wehrmacht established a number of bridgeheads, andarmored and infantry units crossed the Somme and Aisneat a number of points. French airattacks failed to destroy the bridgeheads, although the frontline artilleryunits stalled the German breakthrough for a number of days. By June 9, French air power was waning, andthe Luftwaffe soon achieved fully control of the skies. Allied operations also were being greatlyhampered by the 6-8 million French civilians clogging the roads as they fledthe German advance.

By June 10,1940, elements of German Army Group B had broken out at Abbeville, Amiens, and Peronne, while General Guderian’s panzers,part of German Army Group A, advanced toward Reims. At Juniville, the French 3rdArmored Division achieved success against the advancing German armor,destroying 100 tanks. However, Germanarmored spearheads across the line continued to advance south.

On June 9,1940, the French government declared Paris anopen (undefended) city, and the next day, it vacated the capital and moved theseat of government to Tours, and later to Bordeauxon June 14. General Weygand also stated that the FrenchArmy was on the brink of collapse and that the war was lost. Then on June 10, 1940, Italy entered the fray on Germany’s side by declaring war on France and Britain. Italian leader Benito Mussolini rejected thecounsel of his top commanders that Italy was unprepared for war,opportunistically stating that “I only need a fewthousand dead so that I can sit at the peace conference as a man who has fought”. Italy’scontribution to the campaign would be inconsequential, as the 450,000 invading Italiantroops (outnumbering the 190,000 French defenders by over 2:1) were unable tobreak through the Alpine Line in the rough, high-altitude terrain andprevailing winter-like snowy weather at the 300-mile long French-Italianborder.

Meanwhile,General Rommel’s 7th Panzer Division, advancing down the Frenchcoast, captured Le Havreon June 11, 1940, and Saint-Valery-en-Caux, forcing thesurrender of 46,000 Allied troops. OnJune 4, German troops entered Pariswithout resistance. In the east, ArmyGroups A and C were tasked with breaking through the Maginot Line, with by nowwas greatly undermanned, as many of the assigned French armies there had beentransferred to other sectors of fighting. Two panzer corps of Army Group A advanced down the rear of the MaginotLine, one taking the towns of Verdun, Toul, and Metz, while the otherproceeding to the French-Swiss border to cut off the Maginot Line from the restof France. On June 15, from the east,Army Group C launched two frontal offensives into the Maginot Line from theSaar region and from the Rhine furthersouth. In these attacks, the Germansused several hundreds of artillery pieces, including giant rail guns that weretasked with breaking down the thick concrete fortifications. The German 1st Army broke throughat Saarbrucken, while the German 7thArmy breached the Line at Colmar and Strasbourg, forcing the French defenders to retreat to theVosges Mountains. On June 17, German panzer units reached theSwiss border. Even then, much of theMaginot Line held firm, with 48 of its 58 major fortifications beingunconquered by the end of the campaign.

On June 13, 1940 in a Supreme WarCouncil meeting in Tours,the French and British governments acknowledged that the war was lost. As both parties had agreed months earlierthat neither side could seek a separate peace with Germanywithout the other side’s consent, French Prime Minister Reynaud now asked PrimeMinister Churchill to allow Franceto be released from this commitment. Churchill refused, and instead proposed a political union between thetwo countries (Anglo-French Union) and the French government and militarytransferring France’s seatof power to its colonies in North Africa wherethey would continue the war. Bothproposals were rejected by the French government, and on June 15, Reynaudresigned as Prime Minister, and was succeeded by World War I hero, MarshallPhilippe Petain, who immediately made a radio broadcast indicating hisintention to seek an armistice with Germany.

May 25, 2021

May 25, 1982 – Falklands War: Argentine air attacks destroy the British destroyer HMS Coventry

On May 21, 1982, some 4,000 British Marines landedat San Carlos Bay. After easily overpowering the small Argentinegarrison, the British soldiers secured the landing zone, where Britishtransport ships soon arrived to unload weapons and supplies. The Argentineans carried out many airattacks, sinking the British frigates HMSArdent and HMS Antelope on May 21and May 24, respectively, and the destroyer HMSCoventry on May 25. Also badlydamaged were the British frigates HMSArgonaut and HMS Brilliant. Many other ships also could have been hit orsuffered heavy damage were it not that Argentinean pilots often released theirrockets too low, which exploded with little effect or did not detonate on time.

(Taken from Falklands War– Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe – Vol. 3)

Background In early 1982, Argentina’s ruling military junta,led by General Leopoldo Galtieri, was facing a crisis ofconfidence. Government corruption, humanrights violations, and an economic recession had turned initial public supportfor the country’s military regime into widespread opposition. The pro-U.S. junta had come to power througha coup in 1976, and had crushed a leftist insurgency in the “Dirty War” byusing conventional warfare, as well as “dirty” methods, including summaryexecutions and forced disappearances. Asreports of military atrocities became known, the international communityexerted pressure on General Galtieri to implement reforms.

In its desire to regain the Argentinean people’smoral support and to continue in power, the military government conceived of aplan to invade the Falkland Islands, a British territorylocated about 700 kilometers east of the Argentine mainland. Argentinahad a long-standing historical claim to the Falklands,which generated nationalistic sentiment among Argentineans. The Argentine government was determined toexploit that sentiment. Furthermore,after weighing its chances for success, the junta concluded that the Britishgovernment would not likely take action to protect the Falklands, as theislands were small, barren, and too distant, being located three-quarters downthe globe from Britain.

The Argentineans’ reasoning was not withoutmerit. Britainunder current Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher was experiencing an economic recession, and in1981, had made military cutbacks that would have seen the withdrawal from theFalklands of the HMS Endurance, an ice patrol vessel and the British Navy’sonly permanent ship in the southern Atlantic Ocean. Furthermore, Britainhad not resisted when in 1976, Argentinean forces occupied the uninhabitedSouthern Thule, a group of smallislands that forms a part of the British-owned South Sandwich Archipelago, located 1,500 kilometers east of the Falkland Islands.

In 1982, Argentina and Britain went to war for possession of the Falkland Islands and South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands.

In 1982, Argentina and Britain went to war for possession of the Falkland Islands and South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands. In the sixteenth century, the Falkland Islands first came to European attention when they were signed byPortuguese ships. For three and a halfcenturies thereafter, the islands became settled and controlled at varioustimes by France, Spain, Britain,the United States, and Argentina. In 1833, Britaingained uninterrupted control of the islands, establishing a permanent presencethere with settlers coming mainly from Walesand Scotland.

In 1816, Argentinagained its independence and, advancing its claim to being the successor stateof the former Spanish Argentinean colony that had included “Islas Malvinas” (Argentina’s name for the Falkland Islands), theArgentinean government declared that the islands were part of Argentina’s territory. Argentinaalso challenged Britain’saccount of the events of 1833, stating that the British Navy gained control ofthe islands by expelling the Argentinean civilian authority and residentsalready present in the Falklands. Over time, Argentineans perceived the Britishcontrol of the Falklands as a misplacedvestige of the colonial past, producing successive generations of Argentineansinstilled with anti-imperialist sentiments. For much of the twentieth century, however, Britainand Argentina maintained anormal, even a healthy, relationship, although the Falklandsissue remained a thorn on both sides.

After World War II, Britain pursued a policy of decolonization thatsaw it end colonial rule in its vast territories in Asia and Africa,and the emergence of many new countries in their places. With regards to the Falklands, under UnitedNations (UN) encouragement, Britainand Argentinamet a number of times to decide the future of the islands. Nothing substantial emerged on the issue ofsovereignty, but the two sides agreed on a number of commercial ventures,including establishing air and sea links between the islands and theArgentinean mainland, and for Argentinean power firms to supply energy to theislands. Subsequently, Falklanders(Falkland residents) made it known to Britain that they wished to remainunder British rule. As a result, Britain reversed its policy of decolonization inthe Falklands and promised to respect thewishes of the Falklanders.

May 24, 2021

May 24, 1941 – World War II: The German battleship Bismarck sinks the British battle cruiser HMS Hood

British battleships were tasked toprotect merchant ships, and in a number of incidents, they warded off Germansurface raiders from attacking the convoys. This measure paid off materially when two German ships, the newbattleship Bismarckand the cruiser Prinz Eugen, weresighted off Iceland by aBritish naval squadron, and in the ensuing clash on May 24, 1941, the Bismarckwas damaged, although it sank the British battle cruiser HMS Hood. While attemptingto escape to France, the Bismarckwas intercepted and sunk. The increasingBritish Navy presence in the Atlantic and Hitler’s displeasure with the loss ofthe Bismarckcompelled the Fuhrer to suspend surface fleet operations in the Atlantic. TheGerman Navy’s surface vessels finally ceased to have any impact in the Atlanticwhen in February 1942, in the “Channel Dash”,the Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, and Prinz Eugenboldly crossed the heavily protected English Channel from their base in westernFrance to Norway. The transfer was prompted by reports of animminent British invasion of Norway,as well as the need for greater German naval presence in the Norwegian Arcticto stop the Allied convoys supplying the beleaguered Soviet Union.

(Taken from Battle of the Atlantic – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe – Vol. 6)

Battle of the Atlantic On September 1,1939, Germany invaded Poland; two days later, September 3, Britain and Francedeclared war on Germany,starting World War II. On September 4,1939, Britainimposed a naval blockade of German ports. Under the newly established British Contraband Control Service andFrench Blockade Ministry, the British Royal Navy and French Navy (Marine nationale) under over-all Britishcommand, imposed a blockade enforcement system where all ships passing Europeantrade routes were required to stop for inspection at designated British ports(later expanded to include other British colonial ports along merchant routesin the Mediterranean Sea and Indian Ocean). The ships’ cargoes were examined, and items found in a broad list ofdesignated contraband materials, which included ammunitions, explosives, andthe like, but also even foodstuffs, animal feed, and clothing, were subject toseizure. The Allies intended thesemeasures to force Germany,which was deficient in natural resources and heavily dependent on importationof food and raw materials for its people, civilian industries, and warcapability, to enter into peace negotiations, thus bringing the war to an end.

Instead, Germanyimposed its own naval blockade of Britain which, as an island nation,was also heavily dependent on importation of commodities in order to survive,as well as to continue the war. Germany’s aim was to starve Britain into submission. The German Navy’s attempt to stop the flow ofmaterials to Britainparticularly from North America through the Atlantic Ocean, and the Britishefforts to foil the Germans constitute what is known as the Battleof the Atlantic.

By the time of the outbreak of WorldWar II, the ambitious expansion program of the Kriegsmarine (the German Navy) under Plan Z aimed at achievingnaval equality with the British Navy (the world’s largest fleet), was far fromcomplete, and the small German fleet (by comparison) simply could not engage inopen battle either the British or French fleets, the latter two having muchlarger navies.

Instead, early in the war, theKriegsmarine initiated a strategy of commerce raiding, where German surfaceships (battleships, cruisers, destroyers, etc.) and submarines, which werecalled U-boats (from the German: Unterseeboot; “underseaboat”), were sent to the Atlantic Ocean to attack Allied and neutral-nationmerchant vessels bound for Britain. The Germans also used a number of armedmerchant vessels, which were disguised as neutral or Allied ships but manned byGerman Navy personnel, for commerce raiding. As well, later in the war, long-range Luftwaffe planes, particularly theFocke-Wulf Fw 200 Condor, were used for reconnaissance and attack missions.

The German heavy cruisers Deutschland and Admiral Graf Spee, already in the Atlantic Ocean at the outbreak of war, sank several Allied merchantships. The Allies organized severalhunting groups to locate these German ships, so straining their resources asthe British and French allocated three battle cruisers, three aircraftcarriers, fifteen cruisers, and many auxiliary ships to scour the Atlantic. But inDecember 1939, the Graf Spee wascaught and trapped near the River Plate (Rio de la Plata), off the SouthAmerican coast, and scuttled by its crew near Montevideo, Uruguay.

Despite this success, the earlyhunting-group strategy proved counter-productive, as the Allies then possessedinadequate technological resources to locate U-boats, whose strength lay inavoiding detection by submerging underwater and remaining there until thedanger passed. The U-boat’s other mainasset was stealth, and the first naval casualty of the war, the British oceanliner, SS Athenia, was attacked andsunk by a U-boat (which it mistook for a British warship) on September 3, 1939,with 128 lives lost. Also in September1939 and just a few days apart, two British aircraft carriers, the HMS Ark Royal and HMS Courageous, were both attacked by a U-boat, with the formernarrowly being hit by torpedoes, while the latter was hit and sunk. Then in October 1939, another U-boatpenetrated undetected near Scapa Flow, themain British naval base, attacking and sinking the battleship, the HMS Royal Oak.

At the start of the war, the Britishmilitary was hard-pressed on how to deal with the U-boat threat. During the interwar period, prevailing navalthought and budgetary resources, both Allied and German alike, focused onsurface ships, and the belief that battleships would play the dominant role innaval warfare in a future war. GermanU-boats had proved highly effective in World War I, causing heavy losses onmerchant shipping that nearly forced Britain out of the war, before theBritish introduced the convoy system that turned fortunes around.

However, the British Navy’simplementing the ASDIC system (acronym for “Anti-Submarine DetectionInvestigation Committee”; otherwise known as SONAR), which could detect thepresence of submerged submarines, appeared to have solved the U-boatthreat. Naval tests showed that once detectedby ASDIC, the submarine could then be destroyed by two destroyers launchingdepth charges overboard continuously in a long diamond pattern around thetrapped vessel. The British concept wasthat the U-boats could operate only in coastal waters to threaten harborshipping, as they had done in World War I, and these tests were conducted underdaylight and calm weather conditions. But by the outbreak of World War II, German submarine technology hadrapidly advanced, and were continuing so, that U-boats were able to reachfarther out into the Atlantic Ocean, eventually ranging as far as the Americaneastern seacoast, and also were able to submerge to greater depths beyond thecapacity of depth charges. These factorswould weigh heavily in the early stages of the Battleof the Atlantic.

In December 1939, hostilities weresuspended by the harsh Atlantic weather, and German surface ships and U-boatsreturned to their bases in Germany. In May 1940, the eight-month “Phoney War”period of combat inactivity in the West was broken by the German invasion of France and the Low Countries, which had beenpreceded one month earlier, April 1940, with the conquest of the Scandinaviancountries of Denmark and Norway. By late June 1940, these campaigns werecomplete, Italy had joinedthe war on Germany’s side,and Britain remained thesole defiant nation in Western Europe.

May 23, 2021

May 23, 1945 – World War II: The Flensburg government of Nazi Germany is dissolved and its leaders arrested by British forces

On May 23, 1945, the post-Hitler Flensburg government of Nazi Germany wasdissolved following the arrest of its leaders by British forces. The Flensburg government, based in northern Germany, was formed following the death bysuicide of Adolf Hitler on April 30, 1945 and exercised only limited authorityover Germanyand its territories because of the rapidly collapsing military conditionstowards the end of the war.

(Taken from The End of World War II in Europe – Wars of the 20th Century – Vol. 6)

Germany Asstipulated in the Allied war agreements, the Polish Kresy region(188,000 km²) was annexed to the Soviet Union, and to compensate for thisloss, German territory east of the Oder-Neisse Line, which included Silesia,Neumark, and most of Pomerania (totaling 111,000 km²), was awarded toPoland. East Prussia also was detached from Germanyand divided between the Soviet Union and Poland. In total, Germany lost 25% of its pre-warterritory. The Sudetenland reverted to Czechoslovakia, as did Alsace-Lorraine to France. In 1947, the Saar region also was detachedfrom Germany and awarded to Franceas a protectorate. Following areferendum in 1955 where Saar residents rejected a proposal of independence forthe Saar, the region was incorporated into West Germany in January 1957. In April 1949, the Netherlands annexed a number ofsmall German areas near the German-Dutch border (totaling 69 sq km) as warreparation. In August 1963, these landswere returned to Germanyin exchange for monetary compensation.

The remainder of Germanterritory was then partitioned into four military occupation zones, one eachfor the Soviet Union, United States,Britain, and France[1].

The Allies freed thesurviving 11 million POWs and foreign slave workers (from the 12-15 milliontotal) in Germany, repatriating them back to their home countries: 5.2 millionto the Soviet Union 1.6 million to Poland, 1.5 million to France, 900,000 toItaly, and 300,000-400,000 each to Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, the Netherlands,Hungary, and Belgium.

The returning 1.7 millionSoviet POWs (which comprised the 30% survivors of the 5.7 million totalcaptured during the war), as well as the repatriated Soviet civilian slavelaborers, were suspected as traitors by the Soviet government, because ofStalin’s war-time “no surrender” decree. As a result, these Soviet repatriates were screened in “filtrationcamps” for possible collaboration with the Nazis, and 90% were later cleared,and 10% civilian and 20% ex-POWs were sent to “penal battalions”. Another 2% civilian and 10% ex-POWs (over200,000 soldiers) were sent to Gulag labor camps.

The Allies were determinedthat Germanyshould be prevented from starting another war. As stipulated in the Potsdam Agreement, the Allies dissolved the GermanArmed Forces (Wehrmacht) and banned Germany from producing weapons andwar-related commodities. Also of greatimportance to the Allies was the de-industrialization of Germany, particularly thedestruction of German heavy industry, including ship construction, machineproduction, and chemical plants, other war-related industries, which wasintended to eliminate German war-making capability. The Allies wanted to transform Germanyinto a semi-pastoral state by limiting its economy to agriculture and lightindustries. Consequently, a massivedismantling of German heavy industry took place, with hundreds of manufacturingplants destroyed or dismantled.

The dismantled industrialplants were claimed as war reparations and shipped to Allied countries, wherethey were re-assembled for production. The Western Allies eventually stopped the de-industrialization process withthe emerging new state of West Germany. In the Soviet sector, a much greater and longer disassembly and seizureof German industry occurred, both claimed as war reparations and to pay foroccupation cost. By 1949, nearly allindustries were in Soviet control to exploit, severely hindering reconstructionof the new Soviet-sponsored state of East Germany.

The Allies also weredetermined to impose the denazification of Germany, as stipulated in thePotsdam Agreement. In this regard, theAllies formed the International Military Tribunal which began the prosecutionof high-ranking leaders of Nazi Germany. The first of the Nuremberg Trials (in Nuremberg, Germany),as the series of prosecutions were called, took place on November 20,1945-October 1, 1946. Of the 24 personsindicted, 12 were sentenced to death, 7 were given prison sentences rangingfrom 10 years to life, 3 were acquitted, 1 committed suicide before the trialsbegan, and 1 was diagnosed as medically unfit for trial. Ten of the twelve sentenced to death wereexecuted by hanging on October 16, 1946: Joachimvon Ribbentrop (Minister for Foreign Affairs), General Wilhelm Keitel (Chief ofthe German Armed Forces), General Alfred Jodl (German Armed Forces Chief ofOperations), Hans Frank (Governor-General of the General Government of occupiedPoland), Wilhelm Frick (Minister of the Interior), Ernst Kaltenbrunner(Director of the Reich Main Security Office), Alfred Rosenberg (Head of theForeign Policy Office of the Nazi Party), Fritz Sauckel (GeneralPlenipotentiary for Labor Deployment), Arthur Seyss-Inquart (Reichskommisar inthe Netherlands), and Julius Streicher (Publisher of anti-Semitic newspapersand propaganda).

Hermann Goering, Germany’s Vice-Chancellor and head of theLuftwaffe, committed suicide the night before the scheduled executions, whileMartin Bormann, Secretary to the Fuhrer and chief of the Nazi Party HeadOffice, was determined to have already died in Berlin near the end of the war. Hitler and two other high-ranking Nazi leadersHeinrich Himmler (head of the SS and Chief of the German Police) and JosephGoebbels (Minister of Propaganda) all committed suicide at the closing days ofthe war.

Subsequently, prosecution oflower ranking Nazi officials was conducted. In total, of the 1,672 persons indicted, 1,416 were found guilty. Fewer than 200 were executed, while 279 weregiven prison life sentences. In theperiod that followed, the longer prison sentences were greatly reduced, and tendeath sentences were lowered to prison terms. In 1951, in an amnesty by the West German government, many of thoseimprisoned were released and pardoned.

The Allies also imposed warreparations on Germany,as stipulated in the Potsdam Agreement. As mentioned, Germanywas forced to cede 25% of its pre-war territory to Polandand the Soviet Union. In the following years, some 12 millionethnic Germans were expelled in the ceded German regions of Pomerania, Neumark, Silesia, and East Prussia. The long-established German populations inthe Baltic States of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania (which were now Sovietsatellite countries) also were expelled, as were those in Czechoslovakia,Hungary, Romania, and Yugoslavia. TheAllies wanted post-war European countries to have as much of a single ethnic groupas possible, that ethnic mixing would only be a source of constant tension andconflict. The expelled Germans wereforced to move within the new German borders, greatly increasing Germany’spost-war problems. By the 1950s, some20% of the West German population consisted of former refugees.

As well, the Allies seized thousands ofindustrial plants and assets aimed at destroying Germany’s heavy industries. Britainand the United States, andthe Soviet Union, separately, imposed “intellectual reparations”, where they seized Germany’s scientific and technicalassets, documents, and machineries, as well as patents, copyrights, andtrademarks, the combined value taken by the Americans and British amounting toU.S. $10 billion (U.S. $135 billion in 2017). The U.S. and Sovietgovernments also recruited many thousands of German scientists and technicians,particularly those involved in high-technology development such as long-rangerockets, nuclear bombs, and jet planes, sending them to work in these advancedtechnologies in the United Statesand Soviet Union, respectively.

The Allies also conscriptedGermans for forced labor in Allied and formerly occupied countries, as agreedto by the Big Three at the Yalta Conference. The Soviet Union had by far the mostnumber of German forced laborers, some 3 million of the 4 million total,comprising POWs and civilians, taken from the Eastern Front. Polandand Czechoslovakiaalso used German forced laborers. In theSoviet zone of Germany, many German laborers worked in the highly dangerousuranium mines that provided raw materials for the Soviet nuclear bombproject. In France,the Low Countries, and Norway,German forced laborers cleared minefields, which caused a high rate of deathsand injuries, e.g. in September 1945, French officials estimated that 2,000workers were killed or maimed each month. In Britain, most ofthe 400,000 German forced laborers worked on farms, and in 1945 comprised 25%of Britain’sagricultural work force. A heated debatearose in the British Parliament regarding this practice, with the Germanworkers being referred to sometimes as “slaves” or “slave labor”. Over 400,000 German POWs also were sent tothe United States, where they were detained in 700 camps around the country,and worked in farms and factories, somewhat easing the labor shortage caused bymillions of American soldiers that were fighting in the various war theatersoverseas. By 1947, most German POWs inthe United States and in theAmerican sector in Germanywere transferred to Franceand Britain,where they continued working as forced laborers there. German POWs and forced workers in British andAmerican custody were released by the end of 1949, and those by the French bythe end of the following year. In theSoviet Union, most German POWs and forced workers were freed in 1953, with thelast batch repatriated to Germanyin 1956.

In the Paris Peace Treatysigned in February 1947, theAllied Powers: United States, Soviet Union, Britain, and France stipulated aset of impositions on the minor Axis countries of Italy, Romania, Hungary, andBulgaria, as well as the non-Axis German ally, Finland. With regards to war reparations, Italy madepayments to the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia, Greece, Albania, and Ethiopia;Finland to the Soviet Union; Hungary to the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia, andYugoslavia; and Romania to the Soviet Union, Bulgaria, Greece, andYugoslavia. Italy lost its colonies (ending theItalian Empire) and parts of its mainland territory. For Finland,the Paris Peace Treaty reaffirmed two previous Finnish-Soviet agreements: theMoscow Peace Treaty of 1940 and Moscow Armistice of 1944, where Finland ceded territory to the Soviet Union. Territorial adjustmentsalso were made on the borders of Hungary,Romania, and Bulgaria.

[1] This partition was meant to be temporary, but as post-war tensionsrose between the Western Allies and the Soviet Union, the occupation zonestransitioned into political entities, with West Germany (officially: FederalRepublic of Germany) created in May 1949 from the American, British, and Frenchsectors; and East Germany (officially: German Democratic Republic) emerging inresponse in October 1949 from the Soviet sector.

May 22, 2021

May 22, 1947 – Cold War: The U.S. government aids Turkey and Greece to “contain” Soviet expansionism

American foreign policy inthe post-war era finally took shape in March 1947 with the Truman Doctrine, which arose from a speech by President Truman before theU.S. Congress, where he stated that his administration would “support freepeoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or byoutside pressures”. President Trumangave reference to supporting friendly forces in the on-going Greek Civil Warafter the British had announced the end of their involvement in theconflict. Truman also requested U.S.Congress support for Greece’sneighbor, Turkey,which was being pressured by Stalin to grant Soviet base and transit rightsthrough the Turkish Straits. Russiantroops also continued to occupy northern Iran despite the Sovietgovernment’s war-time promise to leave when the war ended. To the Truman administration, a communistvictory in Greece, and theabsorption of Turkey and Iran into the Soviet sphere of influence wouldlead to Soviet expansion into the oil-rich Middle East.

The Truman Doctrine of “containing”Soviet expansionism is generally cited as the trigger for the Cold War, theideological rivalry between the United States and Soviet Union in particular,and the forces of democracy and communism in general. By the late 1940s, with the apparent threatof imminent war looming, the Western European democracies: Britain, France,Italy, Belgium, Netherlands, Luxembourg, Portugal, Norway, Denmark, andIceland, and the United States and Canada, formed a military alliance calledthe North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in April 1949. Then in May 1955, with the entry of West Germanyinto NATO and the formation of the West German Armed Forces, the alarmed SovietUnion established a rival military alliance called the Warsaw Pact (officially:Treaty of Friendship, Co-operation, and Mutual Assistance) with its socialistsatellite states: East Germany, Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Romania,Bulgaria, and Albania. The stage thuswas set for the ideological and military division of Europethat lasted throughout the Cold War.

(Taken from The End of World War II in Europe – Wars of the 20th Century – Vol. 6)

Post-war reconstruction and start of the Cold War Europe was devastated after the war, many millions of peoplelost their lives, and many millions others lost their homes andlivelihoods. Industries were destroyed,and farm lands laid waste, leading to massive food shortages, famines, and morefatalities. Whole national economieswere bankrupt, expended largely toward supporting the war effort.

The United States, whose economy grew enormouslyduring the war, poured into Europe largeamounts of financial and humanitarian support (U.S. $13 billion; U.S. $165billion in 2017 value) toward the continent’s reconstruction. American assistance was directed mainlytoward its war-time Western Allies and formerly occupied nations. U.S.policy toward Germany in theimmediate post-war period was one of hostility and indifference, implementedunder JCS (Joint Chiefs of Staff) Directive 1067, which stipulated “to take nosteps looking toward the economic rehabilitation of Germany”. At this time, Germany was divided into fourAllied zones of occupation, and stripped of its heavy industries and scientificand technical intellectual properties, including patents, trademarks, andcopyrights.

The Allies also severelyrestricted access to Germany for international humanitarian agencies (e.g.International Red Cross) sending food, leading to low nutritional levels andhunger among Germans, which caused high mortality and malnutrition rates amongchildren and the elderly. The Alliesdeliberately limited Germany’sprocurement of food to the barest minimum, to a level just enough to preventcivil unrest or revolts, which could compromise the safety of occupationtroops. By 1946, the Allies began togradually ease these restrictions, and many donor agencies opened in Germanyto provide food and humanitarian programs.

By 1947, Europe’seconomic recovery was moving forward only slowly, despite the massive infusionof American funds. Farm production wasonly 83% of pre-war levels, industrial output only 88%, and exports just59%. High levels of unemployment andfood shortages caused labor strikes and social unrest. Before the war, Europe’seconomy had been linked to German industries through the exchange of rawmaterials and manufactured goods. In1947, the United Statesdecided that Germany’sparticipation in Europe’s economy was necessary, and the Western Allied plan tode-industrialize Germanywas ended. In July 1947, the U.S. government scrapped JCS 1067, and replacedit with JCS Directive 1779, which stated that “an orderly and prosperous Europerequires the economic contribution of a stable and productive Germany”. Restrictions on German industry productionwere eased, and steel output was raised from 25% to 50% of pre-war capacity.

In April 1948, the UnitedStates implemented a massive assistance program, the European Recovery Plan,more commonly known as the Marshall Plan (named after U.S. Secretary of State George Marshall), where the U.S.government poured in $5 billion ($51 billion in 2017 value) in 1948 infinancial aid toward European member-states of the Organisation for EuropeanEconomic Co-operation (OEEC). In theMarshall Plan, which lasted until the end of 1951, the United States donated $13 billion ($134 billionin 2017 value) to 18 countries, with the largest amounts given to Britain (26%), France(18%), and West Germany(11%). Other beneficiaries were Austria, Belgium,Luxembourg, Denmark, Greece,Iceland, Ireland, Italy,Netherlands, Norway, Portugal,Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey,and Trieste. After the Marshall Plan ended in 1952,another program, the Mutual Security Plan, poured in $7 billion ($63 billion in2017 value) annual recovery assistance to Europeuntil 1961. By the early 1950s, Western Europe’s productivity had surpassed pre-warlevels, and the region would go on to enjoy prosperity in the next two decades.

Also significant was theeconomic integration of Western Europe, whichwas promoted by the Marshall Plan and spurred on further by the formation ofthe International Authority of the Ruhr (IAR) in April 1949, where the AlliedPowers set limits to the German coal and steel industries. By 1952, with West Germany firmly aligned with the Western democracies, theIAR was abolished and replaced by the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC),which integrated the economies of France,West Germany, Italy, Belgium,the Netherlands, and Luxembourg. In 1957, the ECSC was succeeded by theEuropean Economic Community (EEC), which later led to the European Union (EU)in 1993.

The Marshall Plan had beenoffered to the Soviet Union, but which Stalinrejected. The Soviet leader alsostrong-armed Eastern and Central European countries under Soviet occupation notto participate, including Polandand Czechoslovakia,which had shown interest. Stalin wasdetermined to achieve a political stranglehold on the emerging communistgovernments of Hungary, Poland, Romania,Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia,and Albania. Participation of these countries in theMarshall Plan would have allowed American involvement in their economies, whichStalin opposed.

Relations between the SovietUnion and the Western Powers, the United States and Britain, deterioratedduring the Yalta Conference (February 1945) when victory in the war becameclear, because of disagreement regarding the post-war future of Poland inparticular, and Eastern and Central Europe in general. In April 1945, new U.S. President Trumanannounced that his government would take a firmer stance against the Soviet Union more than his predecessor, PresidentRoosevelt. Following the end of the war,the United States, Britain, and Francewere wary of the continued Red Army occupation of Eastern and Central Europe,and feared that the Soviets would use them as a staging ground for the conquestof the rest of Europe and the spread ofcommunism. In war-time Alliedconferences, Stalin had demanded a sphere of political influence in Eastern andCentral Europe to serve as a buffer againstanother potential invasion from the West. In turn, Stalin saw the presence of U.S.forces in Europe as a plot by the United States to gain control ofand impose American political, economic, and social ideologies on thecontinent. In February 1946, Stalinannounced that war was inevitable between the opposing ideologies of capitalismand communism.

George Kennan, an envoy inthe U.S. diplomatic officein Moscow, thensent to the U.S. State Department the so-called “Long Telegram”, which warnedthat the Soviets were unwilling to have “permanent peaceful coexistence” withthe West, was bent on expansionism, and was prepared for a “deadly struggle fortotal destruction of rival powers”. Thetelegram proposed that the United States should confront the Soviet threat byimplementing firm political and economic foreign policies. Kennan’s proposed hard-line stance againstthe Soviet Union was eventually adopted by theTruman government. In September 1946, inresponse to the “Long Telegram”, the Soviets accused the United States of “striving for worldsupremacy”.

In March 1946, civil warbroke out in Greecebetween the local communist and monarchist forces. Also that month, Churchill delivered his“Iron Curtain” speech, where he stated that an “iron curtain” had descendedacross Eastern Europe, and warned of further Soviet expansionism into Europe. In reply,Stalin accused Churchill of “war mongering”.

May 21, 2021

May 21, 1991 – Ethiopian Civil War: Ethiopian president Mengistu flees into exile as rebel forces close in on the capital Addis Ababa

On May 21, 1991, Mengistufled into exile in Zimbabwe,where he was granted political asylum, leaving his crumbling regime to hisVice-President, Tesfaye Kidan, who offered the rebels more concessions,including forming a power-sharing government. But by May 26, the last remaining government units defending the approachesto Addis Ababahad collapsed, and the city was poised to be seized by the rebels. Meanwhile in London, under the auspices ofthe United States which was assisting in Ethiopia’s transition to democracy,negotiations between the Ethiopian government and the EPLF and EPRDF to try andwork out a post-war transitional government broke down when the governmentrepresentative walked out of the proceedings in protest of the U.S. mediator’sproposal that EPRDF forces enter the capital to prevent widespread anarchy andlawlessness that were threatening to erupt as a result of the government’simpending collapse. On May 27, 1991,EPRDF forces entered the capital; except for some minor fighting that continueduntil June 1991, the war essentially was over. During the 17-year war, an estimated 400,000 to 580,000 people werekilled in the fighting and war-related violence while another one millionpeople perished during the 1980s famines.

(Taken from Ethiopian Civil War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Background Byearly 1974 but unbeknownst at that time, the 44-year reign of Ethiopia’s aging emperor, HaileSelassie, was verging on collapse under the burgeoning weight of various internalhostile elements. Haile Selassie hadascended to the throne in April 1930, bearing the official title, “His Imperial Majesty the King of Kings ofEthiopia, Conquering Lion of the Tribe of Judah, Elect of God”, to reignover the Ethiopian Empire that had been in existence for 800 years. Except for a brief period of occupation bythe Italian Army from 1936 to 1941, Ethiopia had escaped falling underthe control of European powers that had carved up the African continent intocolonial territories during the 19th century. (The latter event, known as the Scramble forAfrica, saw only two African states, Ethiopiaand Liberia,that did not come under European domination.)

Under Haile Selassie’srule, Ethiopiabecame a founding member state of the United Nations in 1945 and theOrganization of African Unity in 1963. The Ethiopian emperor had placed great emphasis on his personal, as wellas Ethiopia’s, role inpost-World War II international affairs, and as such, had played a major rolein peacemaking and contributed to mediation efforts in various Africanconflicts (e.g. the Congo, Biafra, Algeria,and Morocco). By the 1970s (at which time, he was at the advancedage of 80), Haile Selassie was widely regarded in the international communityand respected as an elder statesman and a great African father figure.

Ethiopia and nearby countries in Africa

Ethiopia and nearby countries in AfricaAt the same time,however, Haile Selassie’s Ethiopiawas mired in numerous internal problems, foremost of which was great socialunrest generated by the deeply entrenched conservative monarchy, aristocraticnobility, and wealthy landowning and business classes that opposed reformswhich were being called for by the various emerging militant sectors ofsociety. In some regions, somelandowners owned large tracts of agricultural land, relegating most of therural population to tenant farmers and farm laborers in a semi-feudal,patronage system. Haile Selassie made someattempts to implement land reform and other measures of agrarian equality, butthese were opposed by the wealthy landowners. Social tensions also existed among Ethiopia’s many ethnic groups,which were further compounded because of the monarch’s de facto absolute rule and sometimes inequitable policies thatfavored his own Amharic ethnic class to the detriment of other regional ethnicgroups.

Ethnic tensions sometimesled to armed rebellion, such as those that occurred in northern Wollo in 1930,Tigray in 1941, and Gojjam in 1968. Haile Selassie placed much emphasis on promoting education, but hisgovernment made only modest gains to transform the elitist educationalstructure into a universal public school system, e.g. by the early 1970s, some90% of Ethiopians were still illiterate. Ironically, however, Ethiopia’seducational system became the breeding ground for radical ideas, as universitystudents, particularly those studying in Europe,became exposed to Marxism-Leninism. Inthe 1960s and 1970s, many ethnicity-motivated, separatist, or socialistmovements emerged in Ethiopia. Among the more important Marxist groups werethe All-Ethiopia Socialist Movement and EthiopianPeople’s Revolutionary Party, while major regionalmovements included the Western Somali Liberation Front (WSLF) and EritreanLiberation Front (ELF), both founded in 1960, and the Oromo Liberation Front,organized in 1973.

For Haile Selassie’sregime, the most serious among the regional groups was the ELP-led Eritreaninsurgency. Eritreahistorically had a long political development separate from Ethiopia, but the latter regarded Eritreaas an integral part of the Ethiopian Empire. In September 1952, the United Nations federated Eritrea (then under temporary Britishadministration) with Ethiopia(the union known as the Ethiopian-Eritrean Federation), which granted Eritreabroad administrative, legislative, judiciary, and fiscal autonomy but under therule of the Ethiopian monarch. However,Eritreans desired full sovereignty and in September 1961, the ELF launched aneventually lengthy 30-year armed struggle for independence.

By the 1960s, Ethiopia’s feudalistic system, governmentcorruption, and failure to implement land reform and other social programs wereinciting student and activist groups to launch protest demonstrations and massassemblies in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia’s capital. Ultimately, however, it was the Ethiopianmilitary that would set in motion the events that would overturn Ethiopia’spolitical system. In December 1960,reformist elements of the military, led by the commander of the Imperial Guard(the emperor’s personal security unit), launched a coup d’état to overthrow Haile Selassie, who was away ona state visit to Brazil. Most of the Ethiopian Armed Forces, however,remained loyal to the government, and the coup failed. In the aftermath, Haile Selassie strove tobring the military establishment under greater control, promoting more ethnicAmharic to the officer corps and plotting discord by playing military factionsagainst each other.

However, discontentremained pervasive within the military, particularly among the rank-and-file soldiers,who chafed at the low pay and poor working conditions. In January 1974, in what became the first of aseries of decisive events, soldiers stationed at Negele, Sidamo Province,mutinied in protest of low wages and other poor conditions; in the followingdays, military units in other locations mutinied as well. In February 1974, as a result of risinginflation and unemployment and deteriorating economic conditions resulting fromthe global oil crisis of the previous year (1973), teachers, workers, andstudents launched protest demonstrations and marches in Addis Ababa demanding price rollbacks, higherlabor wages, and land reform in the countryside. These protests degenerated into bloodyriots. In the aftermath, on February 28,1974, long-time Prime Minister Aklilu Habte-Wold resignedand was replaced by Endalkachew Makonnen, whose government raised the wages of military personnel and set pricecontrols to curb inflation. Even so, thegovernment, which was controlled by nobles, aristocrats, and wealthylandowners, refused or were unaware of the need to implement major reforms inthe face of growing public opposition.

In March 1974, a group ofmilitary officers led by Colonel Alem Zewde Tessema formed the multi-unit “Armed Forces Coordinating Committee” (AFCC)consisting of representatives from different sectors of the Ethiopian military,tasked with enforcing cohesion among the various forces and assisting thegovernment in maintaining authority in the face of growing unrest. In June 1974, reformist junior officers ofthe AFCC, desiring greater reforms and dissatisfied with what they saw was theAFCC’s close association with the government, broke away and formed their owngroup.

This latter group, whichtook the name “Coordinating Committee of the Armed Forces, Police, andTerritorial Army, soon grew to about 110 to 120 enlisted men and officers (noneabove the rank of major) from the 40 military and security units across thecountry, and elected Majors Mengistu Haile Mariam and Atnafu Abate as its chairman and vice-chairman,respectively. This group, which becameknown simply as Derg (an Ethiopian word meaning“Committee” or “Council”), had as its (initial) aims to serve as a conduit forvarious military and police units in order to maintain peace and order, andalso to uphold the military’s integrity by resolving grievances, discipliningerrant officers, and curbing corruption in the armed forces.

Derg operated anonymously(e.g. its members were not publicly known initially), but worked behind suchpopulist slogans as “Ethiopia First”, “Land to the Peasants”, and “Democracyand Equality to all” to gain broad support among the military and generalpopulation. By July 1974, the Derg’spower was felt not only within the military but in the government itself, andHaile Selassie was forced to implement a number of political measures,including the release of political prisoners, the return of political exiles tothe country, passage of a new constitution, and more critically, to allow Dergto work closely with the government. Under Derg pressure, the government of Prime Minister Makonnencollapsed; succeeding as Prime Minister was Mikael Imru, an aristocrat who heldleftist ideas.

May 20, 2021

May 20, 1941 – World War II: German paratroopers invade Crete, starting the battle for the island

On May 20, 1941, German paratroopers landed on Crete, Greece’slargest island on the south. In early June 1941, the Axis conquest of all Greekterritories was completed by the German capture of Creteafter a two-week offensive. The Battleof Crete involved German paratroopers and glider units seizing strategic pointsin the northern coast preparatory to the arrival of other ground forces. The initial German landings brought neardisaster, as the paratroopers suffered heavy casualties and the Luftwaffe losta significant number of planes. But withthe capture of Maleme airfield following an Allied communications error, theGermans established a toehold in Crete formore troops to arrive. On June 1, 1941,the Germans seized the whole island; some 18,000 Allied soldiers who had failedto be evacuated were captured.

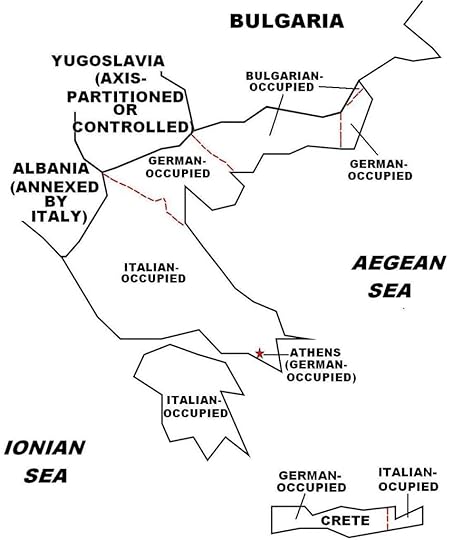

In the aftermath of the Axis campaign, Greece was divided into Axis occupation zones,with Germany taking the moststrategically important regions, including Athens,and the Italians occupying much of the rest of Greece. Bulgaria,which did not participate in the invasion, was allowed to occupy Western Thraceand Eastern Macedonia. In Athens, theGermans set up a collaborationist government under the renamed “Hellenic State”, which held no real power butserved merely as a conduit for German impositions.

(Taken from Invasion of Greece – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe – Vol. 6)

Background OnApril 6, 1941, Germanylaunched Operation Marita, the invasion of Greece,with the German 12th Army in Bulgarialaunching offensives into southern Yugoslavia,whose capture would achieve the strategic objective of cutting off the rest of Yugoslavia in the north with Greece in the south. By the second week, the Germans had capturednearly the whole Greek mainland. Over the course of five nights starting onApril 24, 1941, the British Royal Navy and other Allied ships evacuated 55,000British and Dominion troops to Crete and Egypt. The British also left behind most of theirweapons and military equipment, including trucks, tanks, and planes. For moreinformation on this war, click here.

[image error]May 19, 2021

May 19, 1919 – Turkish War of Independence: The Turkish Nationalist Movement is formed aimed at ending Allied occupation

Under the Armistice ofMudros, the Ottoman government was required to disarm and demobilize its armedforces. On April 30, 1919, Mustafa Kemal, a general in the Ottoman Army, was appointed as theInspector-General of the Ottoman Ninth Army in Anatolia,with the task of demobilizing the remaining forces in the interior. Kemal was a nationalist who opposed theAllied occupation, and upon arriving in Samsunon May 19, 1919, he and other like-minded colleagues set up what became theTurkish Nationalist Movement.

Partition of Anatolia as stipulated in the Treaty of Sevres

Partition of Anatolia as stipulated in the Treaty of SevresRise of the Turkish IndependenceMovement Contact was made with othernationalist politicians and military officers, and alliances were formed withother nationalist organizations in Anatolia. Military units that were not yet demobilized,as well as the various armed bands and militias, were instructed to resist theoccupation forces. These variousnationalist groups ultimately would merge to form the nationalists’ “NationalArmy” in the coming war. Weapons andammunitions were stockpiled, and those previously surrendered were secretlytaken back and turned over to the nationalists.

(Taken from Turkish War of Independence – Wars of the 20th Century –Vol. 3)

On June 21, 1919, Kemalissued the Amasya Circular, which declared among other things, that the unity andindependence of the Turkish state were in danger, that the Ottoman governmentwas incapable of defending the country, and that a national effort was neededto secure the state’s integrity. As aresult of this circular, Turkish nationalists met twice: at the ErzerumCongress (July-August 1991)by regional leaders of the eastern provinces, and at the Sivas Congress (September 1919) ofnationalist leaders from across Anatolia. Two important decisions emerged from thesemeetings: the National Pact and the “Representative Committee”.

The National Pact set forth theguidelines for the Turkish state, including what constituted the “homeland ofthe Turkish nation”, and that the “country should be independent and free, allrestrictions on political, judicial, and financial developments will beremoved”. The “Representative Committee”was the precursor of a quasi-government that ultimately took shape on May 3,1920 as the Turkish Provisional Government based in Ankara(in central Anatolia), founded and led byKemal.

Kemal and his RepresentativeCommittee “government” challenged the continued legitimacy of the nationalgovernment, declaring that Constantinople wasruled by the Allied Powers from whom the Sultan had to be liberated. However, the Sultan condemned Kemal and thenationalists, since both the latter effectively had established a secondgovernment that was a rival to that in Constantinople.

In July 1919, Kemal receivedan order from the national authorities to return to Constantinople. Fearing for his safety, he remained in Ankara; consequently, heceased all official duties with the Ottoman Army. The Ottoman government then laid down treasoncharges against Kemal and other nationalist leaders; tried in absentia, he wasdeclared guilty on May 11, 1920 and sentenced to death.

Initially, Britishauthorities played down the threat posed by the Turkish nationalists. Then when the Ottoman parliament in Constantinople declared its support for the nationalists’National Pact and the integrity of the Turkish state, the British violentlyclosed down the legislature, an action that inflicted many civiliancasualties. The next month, the Sultanaffirmed the dissolution of the Ottoman parliament.

Many parliamentarians werearrested, but many others escaped capture and fled to Ankara to join the nationalists. On April 23, 1920, a new parliament calledthe Grand National Assembly convened in Ankara,which elected Kemal as its first president.

British authorities soon realized that thenationalist movement threatened the Allied plans on the Ottoman Empire. From civilianvolunteers and units of the Sultan’sCaliphate Army, the British organized a militia, which was tasked to defeat thenationalist forces in Anatolia. Clashes soon broke out, with the most intensetaking place in June 1920 in and around Izmit, where Ottoman and British forcesdefeated the nationalists. Defectionswere widespread among the Sultan’s forces, however, forcing the British todisband the militia.

The British then consideredusing their own troops, but backed down knowing that the British public wouldoppose Britainbeing involved in another war, especially one coming right after World WarI. The British soon found another allyto fight the war against the nationalists – Greece. On June 10, 1920, the Allies presented theTreaty of Sevres to the Sultan. Thetreaty was signed by the Ottoman government but was not ratified, since waralready had broken out.

In the coming war, Kemalcrucially gained the support of the newly established Soviet Union, particularly in the Caucasuswhere for centuries, the Russians and Ottomans had fought for domination. This Soviet-Turkish alliance resulted fromboth sides’ condemnation of the Allied intervention in their local affairs,i.e. the British and French enforcing the Treaty of Sevres on the Ottoman Empire, and the Allies’ open support foranti-Bolshevik forces in the Russian Civil War.

May 18, 2021

May 18, 1955 – The end of Operation Passage to Freedom, where the U.S. Navy evacuates 310,000 Vietnamese civilians and soldiers, and non-Vietnamese personnel of the French Army from communist North Vietnam to South Vietnam

On May 18, 1955, the U.S. Navy concluded Operation Passageto Freedom, evacuating some 300,000 Vietnamese civilians, soldiers, andnon-Vietnamese personnel of the French Army from communist North Vietnam to South Vietnam. This action was partof the larger operation led by the French Air Force and hundreds of ships ofthe French Navy and U.S. Navy as well as other Western countries that movedsome one million Vietnamese northerners, predominantly Catholics but alsoincluding members of the upper classes consisting of landowners, businessmen,academics, and anti-communist politicians, and the middle and lower classes,moved to the southern zone. This number included more than 200,000 Frenchcitizens and soldiers in the French army. The campaign to evacuate particularlytargeted Vietnamese Catholics – some 60% of the north’s 1 million Catholics didso, and accounted for 85% of the evacuees to the south.

(Taken from First Indochina War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia – Vol. 5)

This mass movement was a result of a stipulation in theGeneva Accords (May 8, 1954) where representatives from the major powers:United States, Soviet Union, Britain, China, and France, and the Indochinastates: Cambodia, Laos, and the two rival Vietnamese states, DemocraticRepublic of Vietnam (DRV) in the north, and State of Vietnam in the south, metat Geneva (the Geneva Conference) to negotiate a peace settlement for Indochina(as well as Korea). The Conference washeld following the decisive French defeat at Dien Bien Phu(March-May 1954) in the First Indochina War (December 1946 – July 1954).

[image error]On the Indochina issue, onJuly 21, 1954, a ceasefire and a “final declaration” were agreed to by theparties. The ceasefire was agreed to byFrance and the DRV, which divided Vietnam into two zones at the 17thparallel, with the northern zone to be governed by the DRV and the southernzone to be governed by the State of Vietnam. The 17th parallel was intended to serve merely as a provisional militarydemarcation line, and not as a political or territorial boundary. The partitionwas intended to be temporary, pending elections in 1956 to reunify the countryunder a national government.

The French and their allies in the northern zone departedand moved to the southern zone, while the Viet Minh in the southern zonedeparted and moved to the northern zone (although some southern Viet Minhremained in the south on instructions from the DRV). The 17th parallel was also a demilitarizedzone (DMZ) of 6 miles, 3 miles on each side of the line.

The ceasefire agreement provided for a period of 300 dayswhere Vietnamese civilians were free to move across the 17th parallel on eitherside of the line.

The U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and State ofVietnam in a massive propaganda campaign to encourage the northerners to movesouth, including spreading rumors that Red China would invade the north, thatthe northern government would confiscate people’s possessions, and distributingpamphlets with slogans such as “Christ has gone south” and “theVirgin Mary has departed from the North”, alleging anti-Catholicpersecution under Ho Chi Minh.

While one million moved from north to south, some 100,000southerners, mostly Viet Minh cadres and their families and supporters, movedto the northern zone.