Daniel Orr's Blog, page 65

April 16, 2021

April 16, 1961 – Cuban Revolution: Fidel Castro announces that Cuba is a communist state

On January 7, 1959,just a few days after the Cuban Revolution ended, the United States recognized the newCuban government under President Urrutia. But as Fidel Castro later gainedabsolute power and his government gradually turned socialist, relations betweenthe two countries deteriorated rapidly. By July 1959, just seven months later, U.S.president Dwight Eisenhower was planning Castro’s overthrow; subsequently inMarch 1960, he ordered the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to organize andtrain U.S.-based Cuban exiles for an invasion of Cuba.

In 1960, Castro enteredinto a trade agreement with the Soviet Unionthat included purchasing Russian oil. Then when U.S.petroleum companies in Cubarefused to refine the imported Russian oil, a succession of measures and retaliatorycounter-measures followed quickly. InJuly 1960, Cubaseized the American oil companies and nationalized them the next month. In October 1960, the United States imposed an economic embargo on Cuba and banned all imports (which constituted90% of all Cuban exports) from Cuba. The restriction included sugar, which was Cuba’sbiggest source of revenue. In January1960, the United Statesended all official diplomatic relations with Cuba,closed its embassy in Havana,and banned trade to and forbid American private and business transactions withthe island country.

In a nationalbroadcast on April 16, 1961, Castro announced that he was a Marxist-Leninistand that Cubawill be adopt communism. With Cubashedding off democracy and taking on a clearly communist state policy,thousands of Cubans from the upper and middle classes, including politicians,top government officials, businessmen, doctors, lawyers, and many otherprofessionals fled the country for exile in other countries, particularly in theUnited States. However, many other anti-Castro Cubans choseto remain and subsequently organized into armed groups to start acounter-revolution in the Escambray Mountains; these rebel groups’ activities laid thegroundwork for Cuba’snext internal conflict, the “War against the Bandits”.

(Taken from Cuban Revolution – War of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

Background In March 1952, General Fulgencio Batista seizedpower in Cubathrough a coup d’état. He then canceledthe elections scheduled for June 1952, where he was running for the presidencybut trailed in the polls and faced likely defeat. Having gained power, General Batistaestablished a dictatorship, suppressed the opposition, and suspended theconstitution and many civil liberties. Then in the November 1954 general elections that were boycotted by thepolitical opposition, General Batista won the presidency and thus became Cuba’sofficial head of state.

President Batistafavored a close working relationship with Cuba’swealthy elite, particularly with American businesses, which had an established,dominating presence in Cuba. Since the early twentieth century, the UnitedStates had maintained political, economic, and military control over Cuba; e.g.during the first few decades of the 1900s, U.S. forces often interveneddirectly in Cuba by quelling unrest and violence, and restoring politicalorder.

American corporationsheld a monopoly on the Cuban economy, dominating the production and commercialtrade of the island’s main export, sugar, as well as other agriculturalproducts, the mining and petroleum industries, and public utilities. The United States naturally enteredinto political, economic, and military alliances with and backed the Cubangovernment; in the context of the Cold War, successive Cuban governments afterWorld War II were anti-communist and staunchly pro-American.

President Batistaexpanded the businesses of the American mafia in Cuba,where these criminal organizations built and operated racetracks, casinos,nightclubs, and hotels in Havanawith relaxed tax laws provided by the Cuban government. President Batista amassed a large personalfortune from these transactions, and Havanawas transformed into and became internationally known for its red-light district,where gambling, prostitution, and illegal drugs were rampant. President Batista’s regime was characterizedby widespread corruption, as public officials and the police benefitted frombribes from the American crime syndicates as well as from outright embezzlementof government funds.

Cuba did achieve consistently high economic growthunder President Batista, but much of the wealth was concentrated in the upperclass, and a great divide existed between the small, wealthy elite and themasses of the urban poor and landless peasants. (Cuban society also contained a relatively dynamic middle class thatincluded doctors, lawyers, and many other working professionals.)

President Batista wasextremely unpopular among the general population, because he had gained powerthrough force and made unequal economic policies. As a result, Havana(Cuba’scapital) seethed with discontent, with street demonstrations, protests, andriots occurring frequently. In response,President Batista deployed security forces to suppress dissenting elements,particularly those that advocated Marxist ideology. The government’s secret police regularlycarried out extrajudicial executions and forced disappearances, as well asarbitrary arrests, detentions, and tortures. Some 20,000 persons were killed or disappeared during the Batistaregime.

In 1953, a younglawyer and former student leader named Fidel Castro emergedto lead what ultimately would be the most serious challenge to PresidentBatista. Castro previously had takenpart in the aborted overthrow of the Dominican Republic’s dictator Rafael Trujillo and in the 1948 civildisturbance (known as “Bogotazo”) in Bogota, Colombia before completing his law studies atthe University of Havana. Castro had run as an independent for Congressin the 1952 elections that were cancelled because of Batista’s coup. Castro was infuriated and began makingpreparations to overthrow what he declared was the illegitimate Batista regimethat had seized power from a democratically elected government. Fidel organized an armed insurgent group,“The Movement”, whose aim was to overthrow President Batista. At its peak, “The Movement” would comprise1,200 members in its civilian and military wings.

April 15, 2021

April 15, 1998 – Ex-Cambodian leader Pol Pot dies

On April 15, 1998, Pol Pot, former Prime Minister ofDemocratic Kampuchea from 1976 to 1979 passed away in Anlong Veng near the Thai-Cambodianborder. He was the leader of the Khmer Rouge (Kampuchean Communist Party) andruled Kampucheaover a Marxist-Leninist government. He transformed the nation into an agrariansociety, with the entire population forced to relocate in the countryside andwork on collective farms. Extremely dire conditions on these farms whichincluded arduous living and working conditions, restricted food intake and poormedical care, worsened by mass killings, brought about the Cambodian Genocide,where some 1.5 to 3 million people, about 25% of the population, perished.

In December 1978, Vietnaminvaded Cambodia,overthrowing Pol Pot, who fled to the jungles near the Thai-Cambodian borderand waged a guerrilla war against the Vietnamese who occupied the country andinstalled a new communist government in Phnom Penh.

(Taken from Cambodian Genocide – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 5)

On April 17, 1975, the Khmer Rouge, a Cambodian communistrebel group, emerged victorious in the Cambodian Civil War (previous article)when its forces captured Phnom Penh, overthrewthe United States-backed government of the Khmer Republic,and took over the reins of power. InJanuary 1976, the Khmer Rouge ratified a new constitution, which changed thecountry’s name to “Democratic Kampuchea” (DK). In the Western press, DK, as well as the new Cambodian government,continued to be referred to unofficially as “Khmer Rouge”.

In April 1976, the Khmer Rouge’s newly formed legislature,called the Kampuchean People’s Representative Assembly, elected the country’snew government with Pol Pot (whose birth name was Saloth Sar) appointed asPrime Minister. In September 1976, PolPot declared that his government was Marxist-Leninist in ideology that wasclosely allied with Chairman Mao Zedong’s Chinese Communist Party. The following year, September 1977, herevealed the existence of Kampuchea’sstate party called the Kampuchean Communist Party, also stating that it hadbeen formed 17 years earlier, in September 1960. These disclosures confirmed the long-heldbelief by international observers that the Khmer Rouge was a communistorganization, and that DK was a one-party totalitarian state.

Pol Pot had long held absolute power in the Khmer Rouge and(secretly) held the position of General Secretary of the party since 1963behind the façade of a front organization called Angkar Padevat (“RevolutionaryOrganization”, usually shortened to Angkar, meaning “Organization”). Ostensibly, Angkar was politically moderate,as its leaders were former high-ranking Cambodian government officials who heldonly moderate leftist/socialist beliefs. However, behind the scenes, hard-line communist party ideologuescontrolled the movement.

During the Cambodian Civil War, the Khmer Rouge operatedbehind the cover of Prince Norodom Sihanouk, the deposed Cambodian ruler whowas widely popular among the Cambodian masses, through a political-militaryalliance called the Royal Government of the National Union of Kampuchea, orGRUNK (French: Gouvernement royal d’union nationale du Kampuchéa). GRUNK supposedly was a coalition of allopposition movements, and was nominally controlled by Sihanouk as its head ofstate. When the Khmer Rouge seized powerin April 1975, Sihanouk continued to hold the position of head of state underthe new Khmer Rouge regime, but held no real political power. In April 1976, after resigning as head ofstate, he was placed under house arrest.

In foreign relations, DK isolated itself from much of theinternational community. Shortly aftercoming to power, the remaining 800 foreign nationals in Cambodia were gathered at theFrench Embassy in the capital, and then trucked out of the country through theThai border. All foreign diplomaticmissions in Kampucheawere closed down. However, when the DKgovernment later was granted a seat at the United Nations (UN) to represent Kampuchea (Cambodia’snew name), a small number of foreign embassies were allowed to reopen in Phnom Penh. But as foreign travel to Kampuchea was severely restricted,the country was virtually cut off from the outside world. As a result, apart from official governmentpronouncements, practically nothing was known in the outside world about thetrue conditions in the country during the Khmer Rouge regime.

At the core of the Khmer Rouge’s Marxist ideology was theregime’s desire to achieve the purest form of communism, that of a classlesssociety. The Khmer Rouge also advocatedultra-nationalism and anti-imperialism, and desired to eliminate foreigncontrol and achieve national self-sufficiency, first through the phased,collectivized agricultural development of the countryside. Before coming to power, the Khmer Rouge hadrejected the advice of Chinese communist leaders who told them that the processof transition from socialism to communism should not be rushed. But the Khmer Rouge, particularly its leaderPol Pot, was determined to achieve communism rapidly without the transitionalphases of socialism.

The Khmer Rouge first implemented its concept of communismsometime in 1970 at Ratanakiri Province in thenortheast, where it forced the local population to move from villages toagrarian communes. The Khmer Rouge alsocarried out other forced relocations at Steung Treng, Kratie, Banam and Udong. In 1973, the Khmer Rouge concluded that the“final solution” to end capitalism in Cambodia was to empty all the townsand cities, and move all Cambodians to the rural areas. Simultaneously, in areas under its control,the Khmer Rouge executed teachers, local leaders, traders, and other “counter-revolutionaries”. As well, all forms of dissent or oppositionwere met with brutal reprisals. By 1974,the Khmer Rouge was carrying out indiscriminate killings of men, women, andchildren. The rebels also destroyedvillages, such as those that occurred in Odongk and Ang Snuol districts, SarSarsdam village, and other areas.

The Cambodian government soon received reports of thesebrutalities being committed by the Khmer Rouge, but ignored them. An invaluable insight into the workings ofthe Khmer Rouge came in 1973 (two years before the rebels came to power) when aformer school teacher, Ith Sarin, went to the northwest and central regions andjoined the Khmer Rouge. Eventually, IthSarin become disillusioned and left, andreturned to the fold of the law. Hiswork, Regrets for the Khmer Soul (Khmer: Sranaoh Pralung Khmer), revealed thatthe Khmer Rouge was a Marxist organization that operated behind a frontmovement called “Angkar”. Angkar had awell-structured organization that imposed brutal, repressive policies incontrolled areas, which it called “liberated zones”.

The Cambodian government banned Ith Sarin’s book and jailedits author for being a communist sympathizer. Then, a report by an American diplomatic officer, Kenneth Quinn, whichdescribed Khmer Rouge atrocities in eastern and southern Cambodia, was also ignored, this time by U.S.authorities. Contemporary news reportsby some American newspapers (e.g. The New York Times, Baltimore Sun), whichdescribed the Khmer Rouge carrying out massacres, executions, and forcedevacuations, also escaped scrutiny by the U.S. government.

On April 17, 1975, a few hours after capturing Phnom Penh, the KhmerRouge ordered all residents to leave their homes and move to thecountryside. The order to leave was bothurgent and mandatory – those who resisted would be (and were) killed. There were no exceptions, and even the sickand elderly were ordered to leave. Hospitals were closed down and the patients, regardless of their medicalconditions, were evacuated, some still in their beds and attached tointravenous tubes.

Within a few days, Phnom Penh was completely depopulated,with all its residents – some 2.5 million (30% of the country’s population) andordered to take only a few belongings – making their way in long convoys in oxcarts, motorbikes, scooters, and bicycles, but mostly on foot, to rural areasacross the country. The Khmer Rouge’sorder was for all persons to return to their ancestral villages.

In later testimonies, genocide survivors said of being toldby Khmer Rouge cadres that the evacuation was being undertaken because Americanplanes were about to bomb the city, or that the Khmer Rouge was conductingoperations to flush out remaining government soldiers hiding in the city, orthat U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) agents were planning to launchsubversive actions in Phnom Penh to undermine the revolution, etc. Other survivors said of being told that theirdestination was only “two or three kilometers away” and that they could return“in two or three days”.

The Khmer Rouge, in official pronouncements at the time andafter the genocide, said that the forced evacuation of Phnom Penh was necessary because of animminent food shortage and the danger of starvation to city residents, and thatthe Khmer Rouge did not have the logistical capability to fill the void left bythe American departure. (In the finalstages of the war, the U.S.military was supplying Phnom Penh with foodsupplies through the Mekong River and later byairlifts.) Furthermore, the Khmer Rougeleadership stated that the presence of large numbers of people in the ruralareas would force the former urban residents to grow their own food (thusaverting a food shortage), and also help in the reconstruction of the war-ravagedcountryside.

The decision to depopulate Phnom Penh was made sometime inFebruary 1975 (three months before the city’s capture), which was part of theKhmer Rouge’s plan of turning the country into a single collectivizedagriculture-based socialist state worked by peasant-farmers in a classlesssociety. The Khmer Rouge drew itsinspiration from the ancient Khmer Empire (A.D. 800-1400), whose wealth andpower came from its vast agricultural estates. The Khmer Rouge sought to duplicate this past greatness, but under theprinciples of Marxism-Leninism and ultra-nationalism.

The Khmer Rouge viewed the Cambodian countryside as themeans to achieve pure communism, self-sufficiency, and isolation from foreigninfluences. During the Cambodian CivilWar, the Khmer Rouge owed much of its success to the rural areas, where it hadestablished its first permanent bases, and from where it relied on ruralsupport for its food, information, recruits, and sanctuaries. By contrast, the Khmer Rouge did not obtainany support from large urban areas, which it viewed as decadent, West- andcapitalism-corrupted, and must be eliminated, as they served no purpose for thetransformation of the country into a communist state.

Within a few months after the Khmer Rouge completed the masstransfer of the Cambodian population to the countryside, Phnom Penh was partially repopulated, butonly by the Khmer Rouge central government and its associated securityunits. During the DK period, Phnom Penh’s populationprobably reached 40,000 – 100,000 people.

In September 1975 through 1976 and 1977, the Khmer Rougecarried out other forced depopulations in other regions across Kampuchea,particularly in the newly designated Central, Southwest, Western, and EasternZones, (present-day provinces of Takeo, Kampong Cham, Kampong Chhnang, KampongSpeu, Kampong Thom, and Kandal) the Siem Reap and Preah Vihear Sectors,Northwest Zone (present-day provinces of Banteay Meanchey, Battambang, andPursat), and Central (Old North) Zone (Kampong Cham and Kampong Thom).

The Khmer Rouge classified the general population into twogroups: “Old People” (also called base people or full-rights people) and “NewPeople” (also called April 17 people or dépositees). The “Old People” were the peasants,villagers, and essentially those who had supported the Khmer Rouge during thecivil war, and were deemed essential to the nation’s communisttransformation. Also designated as OldPeople were Kampuchean Communist Party cadres, government officials, andmilitary personnel. The “New People”were the evacuated residents of the cities and towns, including the civilianand military components of the previous regime, and essentially those who hadopposed the Khmer Rouge during the war, and who were deemed non-essential tothe socialist revolution, and thus were expendable.

During the civil war, the Khmer Rouge prepared a list ofhigh-ranking civilian and military officials targeted for execution. Instead, after the war, the Khmer Rougearrested and executed all captured government officials, military officers,businessmen, academics and intellectuals, teachers, and anyone who had playedeven only a moderate role in or were identified with the former regime. Perhaps the worst mass killing committed atthis time was the Tuol Po Chrey Massacre, where some 3,000 (to as many as10,000) mostly military officers, including the provincial governor andgovernment officials, were executed in a single day in Tuol Po Chrey, PursatProvince. As a result, professionalpeople, including doctors and engineers, technicians, and anyone who possessedsome education or skilled training, did not reveal their backgrounds andpretended as belonging to the common people. Even then, the Khmer Rouge arrested and killed those who woreeyeglasses, spoke French or other foreign languages, or anyone it considered tobe an intellectual, or had been part of the former regime, or displayed someWestern influence.

On arriving at their destinations, the New People wereorganized into brigades to begin work in agrarian communes. Collectivized farming was the cornerstone ofthe Khmer Rouge regime, and communal farms were set up across the country,consisting of separate Old People and New People communes. The Khmer Rouge called the start of itssocial revolution “Year Zero”, when it planned to wipe out everything that hadcome before, and establish a new Kampuchean state that would achieve greatnessequal to that of the ancient Khmer Empire.

The communal farms that were set up were slave labor camps,where people worked everyday from dawn to dusk (sometimes up to 10 or 11 atnight) doing farm work such as growing crops, clearing forests, drainingswamps, digging irrigation ditches, and building dams. There were no rest days, and all work wasdone by hand or using basic tools (but no machineries). Rest breaks and meals were restricted andinadequate, and work quotas and regulations were strictly enforced. Exhaustion and illness were deemed equivalentto laziness, while complaining about the work or foraging for root crops,vegetables, or fruit in the forest or wayside for personal consumption weresubject to severe punishment. Takinganything from the ground or water was considered stealing from the state. These rules were administered by armedyouths, some as young as twelve years old.

Men and women were segregated into separate living anddining quarters, and marital relations were restricted to specifiedschedules. Social life was eliminated,with religious holidays, celebrations, music, and dance forbidden, as werecourtship and family life. Privateownership was prohibited – the fields, farmlands, crops, and all items in thecommunes, even the clothes and utensils a person used, were state property.

Workers were subjected to revolutionary teachings. The government, which was identified only as“Angkar” (organization), was described as the all-powerful, all-knowing, andbenevolent entity that worked only for the common good. Unknown and unseen, Angkar was feared by all. Indeed, the highest ranking leaders of theKhmer Rouge regime, referred to as Angkar Loeu (“Upper Organization”), werehardly known or rarely seen by the general population. A worker who violated any regulation wasgiven a warning. Three warningsautomatically led to an “invitation” by Angkar, which meant death byexecution. Executions were usuallycarried out at nightfall in a wooded area just outside the commune.

The Khmer Rouge considered children as indispensable to thesocialist revolution, and thus housed them collectively and separately fromtheir parents, and indoctrinated them into communist teachings. Children also were trained to reject theirparents and families, to submit to Angkar, and to hate their enemies. Children were made to feel no sympathy oremotions, and were trained to kill animals in violent ways.

The Khmer Rouge particularly targeted the “New People” who,having lived in the towns and cities, were unprepared for agrarian work andlifestyle. As well, the regime’sharshest policies were directed at them. In the first year, the “New People” population declined considerably asa result of overwork, sickness and disease, summary executions, andstarvation. The Khmer Rouge also tookaway most of the harvest, which left the New People communes with insufficientfood supplies.

“Old People” communes generally were treated muchbetter. However, in post-wartestimonies, survivors from “Old People” communes have stated that they weresubject to the same harsh, repressive conditions experienced by the “NewPeople”.

The Khmer Rouge applied radical measures to speed up thecountry’s transition to communism. Bankswere closed down; money was abolished. Industries were dismantled as government focused on agriculturalproduction. A few industries, e.g.rubber-processing plants, were later reopened, but placed under strict statecontrol. Schools also were closed down,and teachers were executed. The KhmerRouge later opened a number of schools that taught only revolutionary ideology,and only the children of the “Old People” class were allowed to study in them.

Hospitals also were closed down, and most doctors wereexecuted. The Khmer Rouge viewed modernmedicine as “counter-revolutionary” and anathema to communist ideology. As a result of the absence of proper medicalcare, most of the general population suffered from sicknesses anddiseases. About 80% of the peoplecontracted malaria. Only traditionalforms of medicine were allowed, which proved ineffective, particularly for moreserious illnesses. The government didreopen some hospitals which practiced modern medicine, but these medicalfacilities serviced only government officials, the military, party cadres, andtheir families.

The practice of religion, although guaranteed by the KhmerRouge constitution, was suppressed. Thousandsof Buddhist monks (Buddhism was the country’s predominant religion) wereexecuted or forced to become farm workers, Buddhist images were destroyed, andtemples and pagodas were turned into prisons, execution sites, or pig pens. Other religions were persecuted as well. The ethnic minority Chams, who were Muslims,were forced from their homeland and dispersed among the agrarian communes inother regions. As well, they were killedin large numbers in massacres, and their mosques were used to raise pigs. The country’s small Roman Catholic populationalso was forced into slave labor, and the Notre Dame Cathedral and otherchurches in the capital were destroyed. To end all knowledge of and ties to the past, the Khmer Rouge destroyedlibraries and burned books.

The Khmer Rouge, with its vision of achieving Khmer racialpurity, targeted other ethnicities, including Chams, Laotians, Chinese, andparticularly the Vietnamese, who were blamed for all the country’s past andpresent troubles. Nearly all theremaining 200,000 ethnic Vietnamese were expelled from the country within a fewmonths after the Khmer Rouge came to power, following an earlier expulsion of300,000 by the previous regime. Otherethnic minorities were subject to persecutions that resulted in high numbers ofdeaths, forcing thousands of others to flee the country.

During the Cambodian Civil War, the Khmer Rouge functionedas a coalition of different regional guerilla militias, with each militiaoperating as a virtually autonomous unit under the nominal control of the KCPCentral Committee headed by Pol Pot. After achieving victory in the war, these regional forces took controlof the administrative and military functions in their respective regions. Although Saloth Sar (now going by his nom-de-guerrePol Pot) and his deputies were recognized as the national leaders of the newstate, the various regional administrations continued to exercise broadautonomous powers in their areas and outside the control of the Phnom Penh centralgovernment. Two (failed) coup attemptsagainst the central government – in July and September 1975 – highlighted thepolitical instability during this time. This period also coincided with the social upheavals generated by thepopulation transfers, when just after the war (April 1975) and then in late1975 until 1976, the Khmer Rouge executed thousands of “enemies of the state”and “counter-revolutionaries” who were identified with the previous regime.

Then in 1977, Pol Pot was ready to launch a purge of theparty. After Pol Pot entered into analliance with Southwest Zone leader Ta Mok, their combined forces initiated aseries of purges in the Eastern, Northern, and Western zones in February 1977,and in the Northwest zone in May. Thepurges were most intense in the Eastern Zone, where some 100,000 local cadres,whom Pol Pot believed were traitors and in alliance with the Vietnamesegovernment in Hanoi,were killed in massacres. Pol Pot hadderisively called Eastern Zone cadres as having “Khmer bodies with Vietnameseminds”.

Suspected disloyal cadres were sent to “interrogation anddetention centers”, which really were torture and execution facilities. These institutions originally wereestablished to prosecute “counter-revolutionaries” (i.e. persons identified withthe previous regime), but soon became packed with arrested communist cadres asthe purges intensified. Some 150 suchfacilities existed, which included Security Prison 21 (S-21) at Tuol Sleng, Phnom Penh, where manycivilian and military cadres, including those with high-ranking positions, wereimprisoned, tortured, and executed. Various forms of tortures were employed which were so brutal and painfulthat the prisoners confessed to committing nonsensical crimes which governmentauthorities had prepared beforehand. Inmany cases, prisoners were forced to implicate members of their own family, whothen were arrested and subjected to the same tortures. After a period of detention, the prisonerswere taken to another location, where they were executed and buried in massgraves. To save on ammunition, KhmerRouge executioners rarely shot their prisoners. Instead, the executions were carried out using a pickaxe, iron bar, or woodenclub, which were struck on prisoners’ head, killing them. Children were executed first by grasping themby their legs and then bashing their heads onto a tree trunk.

The Khmer Rouge killed a large number of Cambodians intowhat tantamounts to genocide. Variousestimates place the total deaths of the Cambodian Genocide at 1½ – 2½ millionpeople, to even as high as 3 million, with about half of the fatalities causedby executions, and the rest due to overwork, starvation, sickness, anddiseases. Another 300,000 perished fromstarvation in the immediate aftermath of the genocide (in the period afterJanuary 1979). Starting in the 1990s,some 20,000 mass graves have been unearthed containing the skeletal remains ofsome 1.4 million executed prisoners. These mass graves are known also as the killing fields, that is, theywere the execution sites used by the Khmer Rouge.

After two decades of war, in late 1991, peace was restoredin Cambodia. In 1997, the Cambodian government beganefforts to investigate the mass killings that occurred during the Khmer Rougeera. In June 2003, Cambodia and the United Nationsestablished the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC;informally known as the Khmer Rouge Tribunal) to prosecute high-ranking KhmerRouge leaders for various crimes including genocide, war crimes, and crimes againsthumanity. The start of the trails wasdelayed because of the lack of government funds. But with financial support provided byforeign countries, the ECCC started the judicial processes in 2006. A number of top Khmer Rouge officials (i.e.Nuon Chea, the second-highest leader; Khieu Samphan, Khmer Rouge head of state;and Kang Kek Iew (“Comrade Duch”), head of internal security and S-21commandant) have since been found guilty of criminal acts. Pol Pot had earlier passed away in April1998, and thus was not tried.

The Cambodian Genocide ended in early January 1979, with theoverthrow of the Khmer Rouge government following the Vietnamese Army’sinvasion of Cambodia.

April 14, 2021

April 14, 1940 – World War II: British forces land in Namsos, Norway

On April 14, 1940, Allied transportships landed the first British troops at Namsos, followed in the next few daysby more British units, and on April 19, by French forces. This combined Allied force advanced southtoward Steinjker, where it rendezvoused with the Norwegian 5th Divisionfor a joint assault on Trondheim. However, the Germans had gained overwhelmingair superiority in the area, which negated any chance of a successful Alliedcounter-attack. On April 20, theLuftwaffe launched a massive air raid that nearly flattened the town, and morecrucially, destroyed most of the Allied supplies needed for the attack. In late April 1940, the Allies abandonedSteinkjer and retreated to Namsos.

Together with the Namsos landing, onApril 17, 1940, Royal Navy transports landed British troops at Andalsnes. Here, instead of heading north as planned,the British advanced south toward Lillehammer,where they linked up with elements of the Norwegian 2nd Divisionwith the aim of stopping the Germans who were advancing north. As at the Namsos front, German air (andarmored) firepower was overwhelming, and the Allies were forced into a fightingretreat with rearguard battles at Tretten, Favang, Vinstra, Kvam, Sjoa, andOtta. The British did have anti-aircraftand anti-tank weapons, as well as a small squadron of 18 planes rushed to alanding strip on the frozen Lesjaskogsvatnet Lake. But the Germans’ overwhelming numericalsuperiority forced the Allies to retreat to the by-now bombed out town of Andalsnes. In early May 1940, Allied ships evacuated theBritish and French forces from Andalsnes, while remnants of the Norwegian 2ndDivision surrendered to the advancing Germans. By then, German forces from Oslo and Trondheim had linkedup. In the aftermath of the debacle incentral Norway,the British Parliament held a series of hotly contested meetings (called the“Norway Debate”)on May 7-8, 1940, which dramatically led to the loss of support of the rulingConservative government and resignation of Prime Minister NevilleChamberlain. Winston Churchill succeededas Prime Minister in a broad-based coalition government.

(Taken from Norwegian Campaign – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe: Vol. 6)

Germanyinvaded Norway mainly toensure the continued flow of iron-ore shipments from Scandinavia, particularly Sweden, to Germany(see Denmarkand Norway,separate article). On April 1, 1940, Hitler set OperationWeserubung (“Weser Exercise”; named for the Weser Riverin northwest Germany), theinvasions of Denmark and Norway,to be launched on April 9. Germanmilitary planners determined that the conquest of Denmarkwas necessary to the simultaneous invasion of Norway,as the Luftwaffe (German Air Force) needed Denmark’sair bases, particularly Aalborg base in northern Jutland, to establish airsuperiority over the Skagerrak, the strait between Denmarkand Norway, in order toprotect the German fleet transporting the ground invasion forces to Norway.

The invasion of Norway was planned as a combined-arms operationinvolving land, sea, and air units of the German military, tasked to surpriseand quickly take control of six key targets in Norway(Oslo, Narvik Trondheim, Bergen,Kristiansand,and Egersund) before the Norwegian military could mount an organizeddefense. The operation involved a highdegree of risk, because much of the German Navy, including several destroyersthat would transport the troops and a number of German capital ships that wouldprovide protection, was to venture away from the safety of German ports intohostile waters. But to counter the realdanger of intervention by the much larger Allied navies (Britain then had the world’slargest navy), the Luftwaffe was tasked to field 1,000 planes, including 186bombers, to gain control of the skies over the Norwegian coastal waters.

Battle of Norway

The Allies were oblivious of the German invasion. In turn, the Germans were unaware that the British were preparing to send a large fleet to mine the Norwegian western coastline, set to take place on April 8, 1940, one day before the German invasion date. The British assumed that its mine-laying action, codenamed Operation Wilfred, would likely generate a German response, in which case, the British would launch Plan R 4, where British troops aboard four cruisers would be landed in Norway to capture key locations. The British government could then justify its occupation of Norway as protecting the country from German invasion. British forces could then seize the Swedish iron-ore mines, thereby achieving the Allied objective of stopping iron-ore shipments to Germany.

The coincidence of the German invasionand British mine-laying operation would bring their navies, as well as those ofthe French and Norwegian navies, on a collision course in Norway, resulting in a number ofnaval clashes during the German invasion.

April 13, 2021

April 13, 1918 – Finnish Civil War: German forces capture Helsinki

Occurring nearly simultaneously with the Whiteforces’ final offensive on Tampere,some 10,000 German Army troops of the Baltic Sea Division landed at Hanko, offthe southern coast, on April 3, 1918; four days later, another German unit, theDetachment Brandenstein consisting of 3,000 soldiers, landed at Loviisa. The Germans moved rapidly toward Helsinki, taking RedFinland’s capital on April 13. Germanforces from the south and the Finnish (White) Army from the north then advancedtoward Red strongholds north of Helsinki,capturing Lahti,Hyvinkää, Riihimäki, and Hämeenlinnaby the third week of April 1918.

Finnish Civil War

(Taken from Finnish Civil War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

By late April, Viipuri, Red Finland’s capital afterevacuating Helsinki,also came under pressure from White forces. On April 29, 1918, a Finnish (White) Army offensive consisting of 18,000troops captured the city, which effectively ended Red Finland as a sovereignentity. A few days earlier, RedFinland’s political and military leaders had fled the city into Soviet Russia,leaving behind some 15,000 Red Guards who were taken prisoner after thebattle. On May 5, 1918, the Kymenlaakso region, the last major Redterritory, fell when White forces captured Kouvola and Kotka. By mid-May 1918, the Karelian Isthmus was inWhite possession; in the wake of Red Finland’s defeat, thousands of socialistsupporters fled to Russia,all the while subjected to attacks by White forces.

The war was over; some 38,000 lost their lives, 25%in the fighting, and 75% by war-related violence. Both sides committed many atrocities againstsupporters of the opposing side, acts which were carried out by military andparamilitary forces without the consent and participation of the civilian Whiteand Red governments. The so-called RedTerror (by Red forces), which took place in territories of Red Finland, targetedconservative politicians, landowners, businessmen/industrialists, and otherWhite supporters; some 1,600 were killed. The White Terror (by White forces) targeted socialistpoliticians and leaders, Red Guards, Red Finland officials, as well as RedFinland-allied Russian soldiers; some 7,000 to 10,000 were killed. White Terror also extended to the 80,000 Redsupporters and fighters who were imprisoned after the war. Poor prison conditions and inadequate foodrations led to some 13,000 prisoner deaths, and individual prisonersexperienced as high as 20% to 30% mortality rates. While Red Terror was sporadic, random, and mostly involvedpersonal motives, White Terror was much more systematic and organized.

April 12, 2021

April 12, 1963 – The start of the Indonesia-Malaysia Confrontation

The Indonesia-Malaysia Confrontation, orKonfrontasi, began on April 12, 1963, when two groups of Indonesian-supportedSarawak rebels crossed the border from Nangabadan, Kalimantan into Sarawak andone group attacked a police station in Tebedu and the other raided a bordervillage in western Sarawak. Indonesia-based infiltrations to Sarawak and Sabah (the latter renamedfrom North Borneo) involved platoon-size units carrying light weapons whichlaunched hit-and-run attacks on enemy targets and armed raids as well as carriedout propaganda campaigns in settlements and villages. By 1964, the Indonesian Army became directlyinvolved in the fighting. At their peak,some 22,000 Indonesian troops and 4,000 irregulars, and 2,000 Sarawakrebels participated in Konfrontasi. Onthe Malaysian side, the British Army, which included Gurkhas (Nepali soldiersin the British Army), and Malaysian troops, and later Australian and New Zealandcontingents, formed the defensive forces, whose operations consisted of confrontingand repelling the attacks.

(Taken from Indonesia-Malaysia Confrontation – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Despite being a low-intensity conflict, Konfrontasitook place in extremely difficult conditions, as the 1,000-mile frontier (andmuch of the island) between Kalimantan andMalaysian Borneo was deep jungle mountains covered with thick forest cover anddense vegetation with seasonal heavy rainfalls, and intersected by many rivers,these natural barriers greatly reducing troop movements. No roads or plotted trails existed andBritish contemporary maps provided only scant topographic details; maps used bythe Indonesian Army were even much less reliable.

Figure 35. Some key areas during Konfrontasi or Indonesia-Malaysia Confrontation.

In February 1964, representatives from Indonesia and Malaysiaheld peace talks in Bangkok, Thailand, which were followed in July by morenegotiations in Tokyo, Japan; however, these meetingsfailed to produce a settlement. Thesecond half of 1964 marked the most intense phase of the war starting in Julywhen the Indonesian Army, by now carrying out or leading most of thecross-border infiltrations, launched 13 border incursions and 34 otherincidents inside Malaysian Borneo.

Then on August 14, 1964, the day President Sukarnogave his “Year of Living Dangerously” speechduring Indonesian Independence Day celebrations in Jakarta, the conflictexpanded into Peninsular Malaysia when the Indonesian armed forces sent 100commandos, supported by a team of Malaysian communists, who made a seabornecrossing over the Malacca Strait from Sumatra and landed south of Johor. British and Malaysian forces contained the intrusion,which ostensibly was aimed at establishing rebel bases on the mainland with theultimate goal of inciting a general uprising to overthrow the Malaysian governmentand install a socialist regime. Then twoweeks later, on September 2, 1964, Indonesian Air Force transport planesairdropped 96 paratroopers in Labis, near Johor; this attack also was stopped,with most of the paratroopers killed or captured.

The British government was soalarmed by the attacks on the Malayan mainland that it resolved to carry out ashow of force to deter further intrusions. In September 1964, in the incident known as the Sunda Strait Crisis, the British Navy sent a squadron of ships thatincluded the aircraft carrier HMSVictorious on a voyage from Singaporeto Fremantle, Western Australia, and which was to pass via the SundaStrait, located between Sumatra and Java. Invoking international law that granted the right of innocent passagethrough Indonesian waters, the British government requested permission from Indonesia,which produced a flurry of increasingly confrontational diplomatic exchangesbetween the two countries. TheIndonesian government then stated that its navy would be carrying out navalexercises in the Sunda Strait and that theBritish flotilla, which it deemed offensive in nature because of the presenceof the aircraft carrier, posed a threat whose consequences would be hard topredict if the ships entered the Strait. A tense three-week impasse followed, but after further strenuousnegotiations, the British ships were allowed to pass through Indonesian watersbut via the Lombok Strait, located east of Java, averting what could have ledinto an unforeseen war between Britain and Indonesia; the incident was the mostintense, dramatic phase of Konfrontasi. Britain possessed overwhelming military superiority against Indonesia,but its role as a former colonial subjugator of peoples would embroil it a politicaland diplomatic nightmare in case of a war against a Third World nation, more soagainst Indonesia that had gained its independence through an armed struggleagainst another colonial power.

In July 1964, the Britishgovernment approved Operation Claret, a clandestine counter-offensive to be launched intoKalimantan aimed at pre-empting the IndonesianArmy’s cross-border infiltrations. Awarethat such operations might generate a negative diplomatic backlash from theinternational community, Britainplanned and executed Claret under top-secret security and restraint, andacknowledged its existence only in 1974, or a decade after the war. Claret also involved the participation ofAustralia and New Zealand, whose Special Forces together with those of theBritish, carried out infiltration operations into Kalimantan to seek out andlocate Indonesian forces that were about to launch cross-border attacks intoMalaysian Borneo. With the enemypositions pinpointed, regular British and Malaysian combat forces then were sentto contain these Indonesian units before the latter could launch theirattacks. The air transport superiorityof the British military, particularly the use of helicopters to move theSpecial Forces forward and deep inside Indonesian territory, was crucial toClaret’s success. The British militaryalso used jungle combat experience it had gained in the Malayan Emergency (afailed uprising by the Malayan Communist Party in the Malay Peninsula during1948-1960), further refining its jungle fighting tactics that forced theIndonesian Army to a defensive stance, particularly since the Britisheventually carried out penetration operations with virtual impunity and atincreasingly greater depth inside Kalimantan. Operation Claret’s effective intelligence gathering intrusions andcontrol of the jungle as well as the British emphases on speed and flexibilityin carrying out hit-and-run attacks proved successful in what the Britishplanners called “aggressive defense”, inflicting heavy casualties on the enemyand forcing the Indonesian Army to stop further intrusions into MalaysianBorneo.

In December 1964, PresidentSukarno renounced Indonesia’smembership in the UN in protest of the international body’s electing Malaysiaas a non-permanent member of the United Nations Security Council (UNSC). Also, British combat successes led toincreased tensions between President Sukarno and the Indonesian military highcommand, relations which already were strained because of the military’s mistrustof the communist PKI which President Sukarno viewed as a counterweight againstthe power of the military establishment. Furthermore, by 1965, President Sukarno had lost much of his onceformidable popular support in Indonesiabecause of the country’s ongoing acute economic crisis brought about byuncontrolled inflation, widespread poverty and unemployment, high foreign debt,and neglected infrastructures and development. Indonesia’sinternal problems ultimately would force an end to the war.

April 11, 2021

April 11, 1979 – Uganda-Tanzania War: Ugandan dictator Idi Amin is overthrown

On April 11, 1979, General Idi Amin was removed frompower when the Tanzanian Army, supported by Ugandan rebels, invaded and tookover Uganda. Uganda then entered a transitionalperiod aimed at a return to democracy, a process that generated great politicalinstability. A succession of leadersheld power only briefly because of tensions between the civilian government andthe newly reorganized Ugandan military leadership. Furthermore, ethnic-based political partieswrangled with each other, hoping to gain and play a bigger role in the futuregovernment.

(Taken from Uganda-Tanzania War – War of the 20th Century – Volume 3)

Background In January 1971, Ugandan President MiltonObote was overthrown in a military coup while he wason a foreign mission. Fearing for hissafety, he did not return to Ugandabut flew to Tanzania, Uganda’ssouthern neighbor, where Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere gavehim political sanctuary. PresidentNyerere’s action, however, was not well received by General Idi Amin, the leader of theUgandan coup, and relations between the two countries deteriorated.

In Uganda, General Amin took overpower and established a military dictatorship, and named himself the country’spresident and head of the armed forces. He carried out a purge of military elements that were perceived as loyalto the former regime. As a result,thousands of officers and soldiers were executed. General Amin then formed a clique ofstaunchly loyal military officers whom he promoted based on devotion andsubservience to his government rather than on merit and competence. In lieu of local civilian governments,General Amin set up regional military commands led by an army officer who heldconsiderable power. Corruption andinefficiency soon plagued all levels of government.

Military officers who hadbeen bypassed or demoted from their positions became disgruntled. Many of these officers, including thousandsof soldiers, crossed the border to Tanzania and met up withex-President Obote and other exiled Ugandan leaders. Together, they formed an armed rebel groupwhose aim was to overthrow General Amin. The rebels were well received by the Tanzanian government, whichprovided them with military and financial support.

In 1972, the rebelslaunched an attack in southern Ugandaand came to within the town of Masakawhere they tried to incite the local population to revolt against the Ugandangovernment. No revolt took place,however. General Amin sent his forces toMasaka, and in the fighting that followed, the rebels were thrown back acrossthe border.

Map 21. Africa showing location of Uganda and Tanzania, and nearby countries.

Ugandan planes pursuedthe rebels in northern Tanzania,but attacked the Tanzanian towns of Bukoba and Mwanza, causing somedestruction. The Tanzanian governmentfiled a diplomatic protest and increased its forces in northern Tanzania. Tensions rose between the two countries.Through mediation efforts of Somalia,however, war was averted and the two countries agreed to deescalate thetension, and withdrew their forces a distance of ten kilometers from theircommon border.

April 10, 2021

April 10, 1950 – Chinese Civil War: Communist forces invade Hainan Island

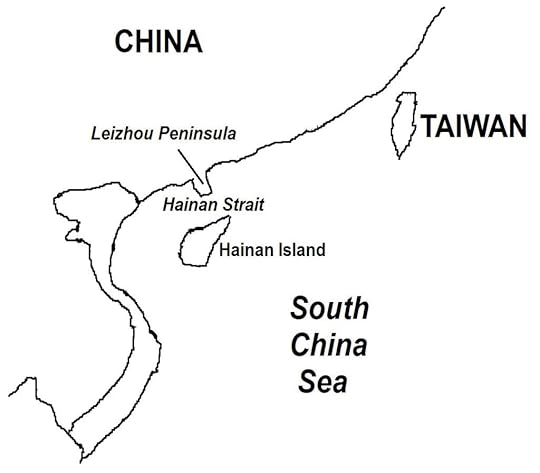

On the night of April 10, 1950, the first wave of the RedChinese main invasion force, consisting of 12,000 soldiers aboard 350 motorizedjunks, set out from the Leizhou Peninsula insouthern China. While the junks were crossing Hainan Strait, they were spottedby Nationalist Navy ships, which moved in to attack. Another flotilla ofCommunist junks, however, moved into position behind the Nationalistships. A naval battle followed. The Communists fired at theNationalist ships using field guns retrofitted on the junks. Theartillery fire from the Nationalist ships was ineffective, as their rounds,intended for armor, simply smashed into the wooden junks withoutdetonating. Following several hours of fighting, the Nationalist shipswithdrew after sustaining heavy damage. Foggy conditions during the nightprevented the Nationalist warplanes from joining the battle.

(Taken from Landing Operation on Hainan Island – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 1)

The first wave of the Communists’ main invasion forcelanded along two points located north of the island. These assaults wereaided by Communist soldiers from the earlier landings who had advanced north toattack the other Nationalist garrisons. On April 17, 1950, the main Nationalistgarrison on the island collapsed, allowing more Communist troops to pour into Hainan.

After establishing a beachhead, the invading forceslaunched a three-pronged offensive to the south: one toward the southeast,another along the west, and the third through the interior. By May 1, thewhole island had been captured. One hundred thousand Nationalist soldierswere taken prisoner; some 60,000 escaped by sea and air to Taiwan.

Map 6. Hainan Island in southern China. In April 1950, Chinese communist forces from the Leizhou Peninsula crossed Hainan Strait and invaded Hainan. After three weeks of fighting, Nationalist forces defending the island were defeated.

The Nationalists’ defeat in Hainan sent shock waves allacross Taiwanwhere desperation began to set in among the civilian population. The United States, having ceased support forPresident Chiang Kai-shek’s government, believed that Taiwan would fall before the end of1950.

Encouraged by the success of the Hainan invasion, China began preparations to invade Taiwan. Tens of thousands of Red Army soldiers were assembled, as were thousands offishermen who were enlisted to pilot the thousands of junks needed for theoperation. Commercial freighters were retrofitted for naval combat andsunken warships from the Chinese Civil War were raised and repaired.

The planned Chinese invasion of Taiwan, however, did notmaterialize. In June 1950, North Korea invadedSouth Korea, where U.S. Army troops were stationed. Suddenly dragged into the conflict now known as the Korean War, the United States broke its neutrality in the regionand sent its Seventh Naval Fleet into the Korean Peninsula. The U.S. naval presence andrenewed American support for Chiang’s government forced China to cancel its planned invasion of Taiwan.

April 9, 2021

April 9, 1975 – Vietnam War: North Vietnamese forces advance to within 40 miles of Saigon

NorthVietnamese leaders, who also were surprised by their quick successes, nowdecided to advance their timeline for conquering South Vietnam by 1976 tocapturing Saigon by May 1, 1975. The offensive on Saigon, called the Ho ChiMinh Campaign andinvolving some 150,000 troops and supplied with armor and artillery units,began on April 9, 1975 with a three-pronged attack on Xuan Loc, a city located40 miles northeast of the national capital and called the “gateway to Saigon”. Resistance by the 18,000-man South Vietnamese garrison (which wasoutnumbered 6:1) was fierce, but after two weeks of desperate fighting by thedefenders, North Vietnamese forces had broken through, with the road to Saigon now lying open.

(Taken from Vietnam War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 5)

In the midstof the battle for Xuan Loc, on April 10, 1975, President Ford again appealed toU.S. Congress for emergency assistance to South Vietnam, which wasdenied. South Vietnamese morale plungedeven further when on April 17, 1975 neighboring Cambodia fell to the communistKhmer Rouge forces. On April 21, 1975, President Thieu resigned(and went into exile abroad) and was replaced by a government to try andnegotiate a settlement with North Vietnam. But the latter, by now in an overwhelmingly superior position, rejectedthe offer.

By April 27,1975, some 130,000 North Vietnamese troops had encircled Saigon,with some intense fighting breaking out at the outskirts and bridges at thecity’s approaches. The South Vietnamesemilitary set up five defensive lines north, west, and east of Saigon,manned by 60,000 troops and augmented by other units that had retreated fromthe north. However, by this time, theSouth Vietnamese forces were verging on collapse, with morale and disciplinebreaking down, desertions widespread, and ammunition and supplies runninglow. In Saigon,desperation and anarchy reigned, with the government’s imposition of martiallaw failing to quell the panic-stricken population.

The end cameon April 30, 1975 when North Vietnamese forces, after launching an artillerybarrage on the city one day earlier, attacked Saigonand entered the city with virtually no opposition, as the South Vietnamesemilitary high command had ordered its troops to lay down their weapons. The Mekong Delta south of Saigonsoon also fell. By early May 1975, thewar was over.

In thelead-up to Saigon’s fall, thousands of SouthVietnamese made a desperate attempt to leave the country. As early as March 1975, the U.S. government had begun toevacuate its citizens and other foreign nationals, as well as some SouthVietnamese civilians. In April 1975, theU.S. launched Operation New Life, where some 110,000 South Vietnamese wereevacuated, the great majority consisting of South Vietnamese military officers,Catholics, bureaucrats, businessmen, locals employed in U.S. military andcivilian facilities, and other Vietnamese who had cooperated or associated withthe United States and thus were considered to be potential targets for NorthVietnamese reprisals. Also in the finaldays of the war, the U.S.military conducted Operation Frequent Wind, where the remaining U.S.nationals and American troops (U.S. Marines) were evacuated by helicopters fromthe Defense Attaché Compound and U.S. Embassy in Saigon onto U.S. ships waiting offshore. The chaotic evacuation, which succeeded inmoving over 7,000 Americans and South Vietnamese, was captured in film, with dramaticcamera footage showing thousands of frantic South Vietnamese civilians crowdingthe gates of the U.S. Embassy, and helicopters being thrown overboard thepacked decks of U.S.carriers to make room for more evacuees to arrive.

Some 58,000 U.S.soldiers died in the Vietnam War, with 300,000 others wounded. South Vietnamese casualties include: 300,000soldiers and 400,000 civilians killed, with over 1 million wounded. North Vietnamese and Viet Cong human lossesare variously estimated at between 450,000 and over 1 million soldiers killedand 600,000 wounded; 65,000 North Vietnamese civilians also lost their lives.

Aftermath The war had a profound, long-lasting effect on the United States. Americans were bitterly divided by it, andothers became disillusioned with the government. War cost, which totaled some $150 billion($1 trillion in 2015 value), placed a severe strain on the U.S. economy,leading to budget deficits, a weak dollar, higher inflation, and by the 1970s,an economic recession. Also toward theend of the war, American soldiers in Vietnamsuffered from low morale and discipline, compounded by racial and socialtensions resulting from the civil rights movement in the United States during the late 1960sand also because of widespread recreational drug use among the troops. During 1969-1972 particularly and during theperiod of American de-escalation and phased troop withdrawal from Vietnam, U.S.soldiers became increasingly unwilling to go to battle, which resulted in thephenomenon known as “fragging”, where soldiers, often using a fragmentationgrenade, killed their officers whom they thought were overly zealous and eagerfor combat action.

Furthermore, someU.S. soldiers returning fromVietnam were met withhostility, mainly because the war had become extremely unpopular in the United States,and as a result of news coverage of massacres and atrocities committed byAmerican units on Vietnamese civilians. A period of healing and reconciliation eventually occurred, and in 1982,the Vietnam Veterans Memorial was built, a national monument in Washington, D.C.that lists the names of servicemen who were killed or missing in the war.

Following thewar, in Vietnam and Indochina, turmoil and conflict continued to bewidespread. After South Vietnam’s collapse, the Viet Cong/NLF’s PRG was installed as the caretakergovernment. But as Hanoi de facto held full political andmilitary control, on July 2, 1976, North Vietnamannexed South Vietnam,and the unified state was called the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.

Some 1-2million South Vietnamese, largely consisting of former government officials,military officers, businessmen, religious leaders, and other“counter-revolutionaries”, were sent to re-education camps, which were laborcamps, where inmates did various kinds of work ranging from dangerous land minefield clearing, to less perilous construction and agricultural labor, and livedunder dire conditions of starvation diets and a high incidence of deaths and diseases.

In the yearsafter the war, the Indochina refugee crisis developed, where some three millionpeople, consisting mostly of those targeted by government repression, lefttheir homelands in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos, for permanent settlement inother countries. In Vietnam, some 1-2 million departingrefugees used small, decrepit boats to embark on perilous journeys to otherSoutheast Asian nations. Some200,000-400,000 of these “boat people” perished atsea, while survivors who eventually reached Malaysia,Indonesia, Philippines, Thailand, and other destinationswere sometimes met there with hostility. But with United Nations support, refugee camps were established in theseSoutheast Asian countries to house and process the refugees. Ultimately, some 2,500,000 refugees wereresettled, mostly in North America and Europe.

The communistrevolutions triumphed in Indochina: in April 1975 in Vietnamand Cambodia, and inDecember 1975 in Laos. Because the United States used massive air firepower in the conflicts, North Vietnam, eastern Laos, and eastern Cambodia were heavily bombed. U.S.planes dropped nearly 8 million tons of bombs (twice the amount the United States dropped in World War II), and Indochina became the most heavily bombed area inhistory. Some 30% of the 270 millionso-called cluster bombs dropped did not explode, and since the end of the war,they continue to pose a grave danger to the local population, particularly inthe countryside. Unexploded ordnance (UXO) has killed some 50,000people in Laos alone, andhundreds more in Indochina are killed ormaimed each year.

The aerialspraying operations of the U.S. military, carried out using several types ofherbicides but most commonly with Agent Orange (whichcontained the highly toxic chemical, dioxin), have had a direct impact onVietnam. Some 400,000 were directlykilled or maimed, and in the following years, a segment of the population thatwere exposed to the chemicals suffer from a variety of health problems,including cancers, birth defects, genetic and mental diseases, etc.

Some 20million gallons of herbicides were sprayed on 20,000 km2 of forests,or 20% of Vietnam’stotal forested area, which destroyed trees, hastened erosion, and upset the ecologicalbalance, food chain, and other environmental parameters.

Following theVietnam War, Indochina continued to experiencesevere turmoil. In December 1978, aftera period of border battles and cross-border raids, Vietnamlaunched a full-scale invasion of Cambodia(then known as Kampuchea)and within two weeks, overwhelmed the country and overthrew the communist PolPot regime. Then in February 1979, in reprisal for Vietnam’s invasion of its Kampuchean ally, China launched a large-scale offensive into thenorthern regions of Vietnam,but after one month of bitter fighting, the Chinese forces withdrew. Regional instability would persist into the1990s.

April 8, 2021

April 8, 1962 – Algerian War of Independence: Over 90% of France’s population approves of the Évian Accords

In May 1961, the Frenchgovernment and the GPRA (the FLN’s government-in-exile) held peace talks at Évian, France,which proved contentious and difficult. But on March 18, 1962, the two sides signed an agreement called theÉvian Accords, which included a ceasefire (that came into effect the followingday) and a release of war prisoners; the agreement’s major stipulations were:French recognition of a sovereign Algeria; independent Algeria’s guaranteeingthe protection of the pied-noir community; and Algeria allowing French militarybases to continue in its territory, as well as establishing privilegedAlgerian-French economic and trade relations, particularly in the developmentof Algeria’s nascent oil industry.

In a referendum held inFrance on April 8, 1962, over 90% of the French people approved of the ÉvianAccords; the same referendum held in Algeria on July 1, 1962 resulted in nearlysix million voting in favor of the agreement while only 16,000 opposed it (bythis time, most of the one million pieds-noirs had or were in the process ofleaving Algeria or simply recognized the futility of their lost cause, thus theextraordinarily low number of “no” votes).

(Taken from Algerian War of Independence – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

However, pied-noirhardliners and pro-French Algeria military officers still were determined toderail the political process, forming one year earlier (in January 1961) the“Organization of the Secret Army” (OAS; French: Organisationde l’armée secrète) led by General Salan,in a (futile) attempt to stop the 1961 referendum to determine Algerianself-determination. Organizedspecifically as a terror militia, the OAS had begun to carry out violentmilitant acts in 1961, which dramatically escalated in the four months betweenthe signing of the Évian Accords and the referendum on Algerian independence. The group hoped that its terror campaignwould provoke the FLN to retaliate, which would jeopardize the ceasefirebetween the government and the FLN, and possibly lead to a resumption of thewar. At their peak in March 1962, OASoperatives set off 120 bombs a day in Algiers,targeting French military and police, FLN, and Muslim civilians – thus, the warhad an ironic twist, as France and the FLN now were on the same side of theconflict against the pieds-noirs.

The French Army and OASeven directly engaged each other – in the Battle of Bab el-Oued, where French security forces succeeded in seizing the OAS stronghold ofBab el-Oued, a neighborhood in Algiers,with combined casualties totaling 54 dead and 140 injured. The OAS also targeted prominent AlgerianMuslims with assassinations but its main target was de Gaulle, who escaped manyattempts on his life. The most dramaticof the assassination attacks on de Gaulle took place in a Paris suburb where a group of gunmen led by Jean-MarieBastien-Thiry, a French military officer, opened fire onthe presidential car with bullets from the assailants’ semi-automatic riflesbarely missing the president. Bastien-Thiry,who was not an OAS member, was arrested, put on trial, and later executed byfiring squad.

In the end, the OAS plan to provoke the FLN intolaunching retaliation did not succeed, as the Algerian revolutionaries adheredto the ceasefire. On June 17, 1962, theOAS the FLN agreed to a ceasefire. Theeight-year war was over. Some 350,000 toas high as one million people died in the war; about two million AlgerianMuslims were displaced from their homes, being forced by the French Army torelocate to guarded camps.

Aftermath OnJuly 3, 1962, two days after the second referendum for independence, de Gaullerecognized the sovereignty of Algeria. Then on July 5, 1962, exactly 132 years afterthe French invasion in 1830, Algeriadeclared independence and in September 1962, was given its official name, the“People’s Democratic Republic of Algeria” by the country’s National Assembly.

In the months leading upto and after Algeria’sindependence, a mass exodus of the pied-noir community took place, with some900,000 (90% of the European population) fleeing hastily to France. The European Algerians feared for their livesdespite a stipulation in the Évian Accords that independent Algeria must respect the rights and propertiesof the pied-noir community in Algeria. Some 100,000 would remain, but in the 1960sthrough 1970s, most were forced to leave as well, as the war had scarredpermanently relations between the indigenous Algerians and pieds-noirs, forcingthe latter to abandon homes and properties under the threat of “the suitcase orthe coffin” (French: “la valiseou le cercueil”). In France,the pieds-noirs experienced a difficult period of transition and adjustment, asmany families had lived for many generations in Algeria, which they regarded astheir homeland. Moreover, they werecriticized and held responsible by French mainlanders for the political,economic, and social troubles that the war had caused to France. Algerian Jews, who feared persecution becauseof their opposition to Algerian independence, also fled Algeria en masse, with 130,000 Jews leaving for France where they held French citizenship; some7,000 Jews also immigrated to Israel.

The harkis, or indigenousAlgerians who had served in the French Army as regulars or auxiliaries, met aharsher fate. Disarmed after the war bytheir French military commanders and vilified by Algerians as traitors andFrench collaborators, the harkis and their families faced harsh retaliation bythe FLN and civilian mobs – some 50,000 to 100,000 harkis and their kin werekilled, most in grisly circumstances. Some91,000 harkis and their families did succeed in escaping to France under the aegis of theirFrench commanders in violation of the orders of the French government.

The bitter effects of thewar were felt in both countries for many years. Throughout the conflict, Francedescribed its actions in Algeriaas a “law and order maintenance operation”, and not war. Then in June 1999, thirty-seven years afterthe war ended, the French government admitted that “war” had indeed taken placein Algeria.

April 7, 2021

April 7, 1994 – The start of the Rwandan genocide

On April 6, 1994, Rwandan PresidentHabyarimina and Burundi’s head of state, Cyprien Ntaryamira,were killed by undetermined assassins when their plane was shot down by arocket-propelled grenade as it was about to land in Kigali. A staunchly anti-Tutsi military government took over power in Rwanda.Within a few hours and in reprisal for the double assassinations, the newgovernment unleashed the Interahamwe “death squads” to murderTutsis and moderate Hutus on sight. Overthe next several weeks, in the event known as the “Rwandan Genocide”,large numbers of civilians were murdered in Kigali and throughout the country. No place was safe; in some instances, evenCatholic churches were the scenes of the massacres of thousands of Tutsis wherethey had taken refuge.

The attackers used clubs, spears,firearms, and grenades, but their main weapon was the machete, with which theyhad trained extensively and which they used to hack away at their victims. At the urging of local officials, Hutucivilians joined in the killing frenzy, and turned against their Tutsineighbors, acquaintances, and even relatives. In many cases, the threat of being killed for appearing sympathetic toTutsis forced many otherwise disinterested Hutus to participate.

(Taken from Rwandan Civil War and Genocide – Wars of the 20th Century– Vol. 2)

The Rwandan Army provided theInterahamwe with a list of Tutsis to be killed, and raised road blocks toprevent any escape. The death toll inthe Rwandan Genocide ranges from between 800,000 to one million; some 10% ofthe fatalities were moderate Hutus. Thegenocide lasted for about 100 days, from between April 6 to July 15, producinga killing rate of 10,000 persons a day. The speed by which it was carried out makes the Rwandan Genocide thefastest in history. (By comparison, theHolocaust in Europe during World War II,although producing a much higher death toll, was carried out over a number ofyears.)

Background Rwanda, a small country in Africa,experienced a long period of ethnic unrest before and after it gained itsindependence in the 1960s. Then in the1990s, this unrest culminated in two events known as the Rwandan Civil War and the Rwandan Genocide, bothof which caused great loss in human lives and massive destruction of thecountry.

The conflict revolved around thehostility between Rwanda’stwo main ethnic groups, the majority Hutus, who comprised 85% of thepopulation, and the Tutsis, who made up 14% of the population. The origin of this hostility goes back manycenturies to when a Tutsi monarchy was established in the Hutu-populated landof what is present-day Rwanda. Over time, the Tutsi monarch gaineddomination over the Hutus. The Tutsimonarch also acquired ownership over most of the land, which he divided intovast estates that were overseen by a hierarchy of Tutsi overlords, and workedby Hutu laborers in a feudal-type system. For the most part, however, Tutsis and Hutus lived in harmony. In the course of time, some Hutus becamewealthy, while many ordinary, non-aristocratic Tutsis remained poor.

Starting in the 1880s, Africa cameunder the control of the European powers who vied for a share of the vastcontinent in the event known as the “Scramble for Africa”. In Rwanda,the Tutsi monarchy fell under the domination of Germany,and during and after World War I, of Belgium. During the colonial period, the Belgians inparticular, emphasized ethnic distinction of the indigenous peoples, and issuedethnic identity cards to natives that indicated if the card holder was a Tutsi,Hutu, or Twa (Twa is a Rwandan tribe that comprises only 1% of thepopulation). The Belgians retained theTutsi monarch as overlord of the colony and appointed Tutsis to administrativepositions in the colonial government. The Belgians believed that Tutsis were racially superior to Hutus. The Belgian policies were resented by Hutus,sowing the seeds of the future conflict.

During the colonial period, Rwanda formed the northern portion of theBelgian colony of Ruanda-Urundi, with the southern half being present-day Burundi (Map 23). Then as a result of growing Africannationalism after World War II, the European powers gradually were grantingindependences to their African colonies. To prepare for Ruanda’s transition todemocracy, the Belgians convinced the Tutsi monarch to abolish feudalism. The Belgians allowed multi-party politics,causing political parties to form – along ethnic lines. Over the previous years, tensions had risenbetween Hutus and Tutsis. By the late1960s as the Belgians prepared to decolonize in the lead-up to Ruanda’s independence, Hutus and Tutsis had becomeconfrontational with each other; violence appeared likely to break out anytime.

Then in November 1959, a Tutsi mobattacked a Hutu politician who was then reported (erroneously) to have beenkilled in the attack. Hutu armed gangslaunched massive retaliatory attacks against Tutsis in Kigali,Ruanda’s capital, and in other areas. Some 20,000 to 100,000 Tutsis were killed,while 150,000 others fled to nearby Urundi, Uganda, Zaire,and Tanzania. The Ruandan Tutsi monarch fled into exile toescape the violence.

Then in a referendum held in 1960,Ruandans voted overwhelmingly to abolish the monarchy. A year earlier, Hutu politicians had scored adecisive victory in the local elections. By a United Nations (UN) mandate, Ruanda-Urundi was dissolved andreplaced by two successor countries, Rwandaand Burundi, both of which gained their independences on July 2, 1962. In the decades that followed theirindependences, the events in each country would have a profound effect on theother country. Rwanda was established as ademocracy, but the Hutus who gained political power ruled the country as a Hutuautocratic state.

The Tutsis who fled the 1959 violenceinto neighboring countries soon militarized, forming armed groups that launchedhit-and-run attacks into Rwanda. One particularly aggressive attack took placein late 1963, when Tutsi rebels based in Ugandacame to within the vicinity of Kigalibefore being driven back by the Rwandan Army.

Map 23: Africa showing location of Rwanda and other East African countries.