Daniel Orr's Blog, page 69

March 7, 2021

March 7, 1945 – World War II: U.S. forces seize the Ludendorff Bridge on the Rhine River

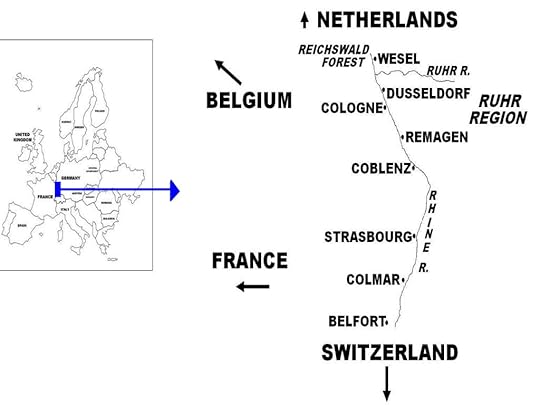

General Dwight D. Eisenhower and the Allied High Commandbelieved that attempting to cross the Rhine ona broad front would lead to heavy losses in personnel, and so they planned toconcentrate Allied resources to force a crossing on the north in the Britishsector. Here also lay the shortest routeto Berlin,whose capture was definitely the greatest prize of the war. Beating out the Soviets to Berlin was greatly desired by Prime MinisterChurchill and the British High Command, which at this point, the British andAmerican planners believed could be achieved. With Allied focus on the British sector in the north, U.S. 12th and6th Army Groups to the south were tasked with making secondary attacks in theirsectors, tying down German troops there and thus aiding the British offensive.

Then on March 7, 1945, elements of U.S. 1st Army (part of U.S. 12th Army Group), upon reaching the Rhine’s west bank at Remagen, came upon a railroad bridgethat was still standing and undefended. The Americans, taking advantage of this unexpected opportunity, rushed25,000 troops in six divisions and large numbers of tanks and artillery piecesto the other side before the bridge collapsed on March 17. By then, U.S. 1st Army had built two tacticalbridges, and had established a secure bridgehead on the eastern side some 40 kmwide and 15 km long. The Germans, duringtheir retreat, had systematically destroyed the fifty bridges across the wholelength of the Rhine, but had failed to detonate the charges on the Remagen Bridge.

Battle for the Rhine River.

Battle for the Rhine River.(Taken from Defeat of Germany in the West: 1944-1945 – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

On March 22, 1945, U.S. Third Army also crossed the Rhine, at Oppenheim and soon at two other points furthernorth. General Patton, the U.S. 3rd Armycommander, had rushed the crossings with little preparations, purposely to denyhis rival General Montgomery the honor of being the first to force an opposedcrossing of the Rhine. To the south, U.S. 7th Army crossed at Worms and the French at Germersheim.

On March 23, 1945, General Montgomery and 21st Army Grouplaunched Operation Plunder, the forcing of the Rhine at Rees, Wesel,and south of the Lippe River. As was typical with General Montgomery, theoperation was launched after thorough preparation and heavy concentration offorces. The offensive was made with thelargest airborne assault in history (Operation Varsity, involving 16,000 Alliedparatroopers in 3,000 planes and gliders), and massive air and artillerybombardment of German positions before the amphibious crossing of the Rhine by the ground forces. The operation was a great success,overwhelming the German defenders. Bylate March 1945, the Allies had established a chain of bridgeheads on the Rhine’s eastern bank and were threatening to break outinto the German heartland.

On March 28, 1945, General Eisenhower announced that thecapture of Berlinwas not anymore the main goal of the Western Allies, for the followingreasons. First, the Soviet Red Armywould clearly reach Berlin first, as it waspoised at the Oder River just 30 miles (48 km) of the German capital,while the Western Allies at the Rhine were over 300 miles (480 km) from Berlin. Second, the breakthrough in the south wouldallow the Western Allies, particularly the U.S.forces, to rapidly fan out into the heart of Germany, which would break Germanmorale and bring a quick end to the war. Third, SHAEF priority was now to capture the Ruhr region, Germany’s industrial heartland, to destroyGerman’s weapons production facilities and incapacitate Germany’sability to continue the war.

Under these revised objectives, the three Allied Army Groupsadvanced into Germany andthen into Central Europe. In the north, the British advanced toward Hamburg and the ElbeRiver, and met up with Soviet forcesat Wismar in the Baltic coast on May 2, 1945,while the Canadians secured the Netherlandsand northern German coast. To the southof the British, on March 7, U.S.9th and 1st Armies attacked the Ruhr region ina pincers movement, leading to the last large-scale battle in the WesternFront. On April 4, the pincers closed,and U.S. forcessystematically destroyed the trapped German Army Group B inside the Ruhr pocket. OnApril 21, the pocket was cleared and the Americans captured over 300,000 Germansoldiers, this unexpected massive German defeat surprising the Allied HighCommand. As a result of thiscatastrophe, German Army Group B commander General Walther Model committedsuicide, while concerted German defense of the Western Front effectivelyceased. Other elements of U.S. 9th and 1st Armies had also advancedfurther east, and on April 25, 1945, contact was made between American andSoviet forces at the Elbe River.

Further to the south, General Patton’s 3rd Army advancedinto western Czechoslovakiaand southeast for eastern Bavaria and northernAustria. U.S.6th Army Group (U.S. 7thArmy and the French Army) turned south into Bavaria,Austria, and northern Italy, with the isolated German garrisons at Heilbronn, Nuremberg, and Munich putting up somestiff resistance before surrendering.

On April 30, 1945, Hitler committed suicide, and three dayslater, Berlinfell to the Red Army. As per Hitler’slast will and testament, governmental powers of the now crumbling German statepassed on to Admiral Karl Doenitz, head of the German Navy, who at once tooksteps to end the war. On May 2, Germanforces in Italy and western Austria surrendered to the British, and two dayslater, the Wehrmacht in northwest Germany,the Netherlands and Denmark surrendered, also to the British, whileon May 5, German forces in Bavaria andsouthwest Germanysurrendered to the Americans. At thistime, isolated German units facing the Soviets were desperately trying to fighttheir way to Western Allied lines, hoping to escape the punitive wrath of theRussians by surrendering to the Americans or British.

On May 7, 1945, General Alfred Jodl, German Armed ForcesChief of Operations, signed the instrument of unconditional surrender of allGerman forces at Allied headquarters in Reims, France. A few hours later, Stalin expressed hisdisapproval of certain aspects of the surrender document, as well as itslocation, and on his insistence, another signing of Germany’s unconditionalsurrender was held in Berlin by General Wilhelm Keitel, chief of German ArmedForces, with particular attention placed on the Soviet contribution, and infront of General Zhukov, whose forces had captured the German capital.

Shortly thereafter, most of the remaining German unitssurrendered to nearby Allied commands, including Army Group Courland in the“Courland Pocket”, Second Army Heiligenbeil and Danzig beachheads, German unitson the Hel Peninsula in the Vistula delta, Greek islands of Crete, Rhodes, andthe Dodecanese, on Alderney Island in the English Channel, and in AtlanticFrance at Saint-Nazaire, La Rochelle, and Lorient.

March 6, 2021

March 6, 1975 – Iran-Iraq War: The Algiers Accord is signed

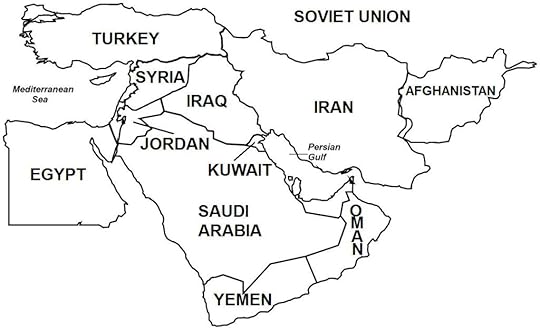

By the early 1970s, the autonomy-seeking Iraqi Kurds wereholding talks with the Iraqi government after a decade-long war (the FirstIraqi-Kurdish War, separate article);negotiations collapsed and fighting broke out in April 1974, with the IraqiKurds being supported militarily by Iran. In turn, Iraq incitedIran’sethnic minorities to revolt, particularly the Arabs in Khuzestan, IranianKurds, and Baluchs. Direct fightingbetween Iranian and Iraqi forces also broke out in 1974-1975, with the Iraniansprevailing. Hostilities ended when thetwo countries signed the Algiers Accord on March 6, 1975, where Iraq yielded to Iran’sdemand that the midpoint of the Shatt al-Arab was the common border; inexchange, Iranended its support to the Iraqi Kurds.

Iraq wasdispleased with the Shatt concessions and to combat Iran’s growing regional militarypower, embarked on its own large-scale weapons buildup (using its oil revenues)during the second half of the 1970s. Relations between the two countries remained stable, however, and evenenjoyed a period of rapprochement. As aresult of Iran’s assistancein helping to foil a plot to overthrow the Iraqi government, Saddam expelledAyatollah Khomeini, who was living as an exile in Iraq and from where the Iraniancleric was inciting Iranians to overthrow the Iranian government.

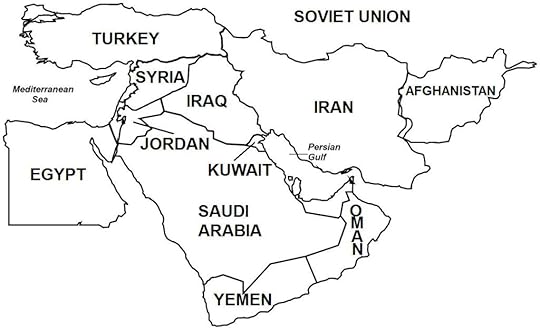

Iran, Iraq, and nearby countries.

Iran, Iraq, and nearby countries.(Taken from Iran-Iraq War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Background(continued) However, Iranian-Iraqi relations turned for the worse towardsthe end of 1979 when Ayatollah Khomeini was proclaimed as Iran’s absolute ruler. Each of the two rival countries resumedsecessionist support for the various ethnic groups in the other country. Iran’s transition to a full IslamicState was opposed by the various Iranian ethnic minorities, leading to revoltsby Kurds, Arabs, and Baluchs. TheIranian government easily crushed these uprisings, except in Kurdistan,where Iraqi military support allowed the Kurds to fend off Iranian governmentforces until late 1981 before also being put down.

Ayatollah Khomeini, in line with his aim of spreadingIslamic revolutions across the Middle East, called on Iraq’s Shiitemajority to overthrow Saddam and his “un-Islamic” government, and establish anIslamic State. In April 1980, a spate ofviolence attributed to the Islamic Dawa Party, an Iran-supported militantgroup, broke out in Iraq,where many Baath Party officers were killed and other high-ranking governmentofficials barely escaped assassination attempts. In response, the Iraqi government unleashedrepressive measures against radical Shiites, including deporting thousands whowere thought to be ethnic Persians, as well as executing Grand AyatollahMohammad Baqir al-Sadr, which drew widespread condemnation from several Muslimcountries as the religious cleric was highly regarded in the wider Islamiccommunity.

Throughout the summer of 1980, many border clashes broke outbetween forces of the two countries, increasing in intensity and frequency bySeptember of that year. As to theofficial start of the war, the two sides have different interpretations. The Iraqis cite September 4, 1980, when theIranian Army carried out an artillery bombardment of Iraqi border towns,prompting Saddam two weeks later to unilaterally repeal the 1975 Algiers Accordand declare that the whole Shatt al-Arab lay within the territorial limits of Iraq.

September 22, 1980, however, is generally accepted as thestart of the war, when Iraqi forces launched a full-scale air and groundoffensive into Iran. Saddam believed that his forces were capableof achieving a quick victory, his confidence borne by the following factors,all resulting from the Iranian Revolution. First, as previously mentioned, Iranfaced regional insurgencies from its ethnic minorities that opposed Iran’s adoptionof Islamic fundamentalism. Second, Iran furtherwas wracked by violence and unrest when secularist elements of the revolution(liberal democrats, communists, merchants and landowners, etc.) opposed theIslamist hardliners’ rise to power. TheIslamic state subsequently marginalized these groups and suppressed all formsof dissent. Third, the revolutionseriously weakened the powerful Iranian Armed Forces, as military elements,particularly high-ranking officers, who remained loyal to the Shah, was purgedand repressive measures were undertaken to curb the military. Fourth, Iran’s newly established Islamicgovernment, because it rejected both western democracy and communist ideology,became isolated internationally, even among Arab and Muslim countries.

Because of the United States’ support for Iran’s previousregime and in response to the U.S. government’s allowing the ailing Shah toseek medical treatment in the United States, hundreds of radical Iranianstudents broke into the U.S. Embassy in Tehran on November 4, 1979 and tookhostage over sixty American diplomatic personnel and citizens. (This event, known as the Iran hostagecrisis, ended on January 20, 1981 when the 52 remaining hostages werereleased.) In response, the United States ended diplomatic, economic, andlater, military relations with Iran,and imposed economic sanctions and military restrictions. These U.S.sanctions were detrimental to Iran,in particular with regards to the coming war with Iraq,as the weapons and military hardware of the Iranian Armed Forces were sourcedfrom the United States.

Saddam wanted to make Iraqthe dominant power in the Middle East, a position traditionally held by Egypt but which Egyptian President Anwar Sadathad yielded politically after signing a peace agreement with Israel in March1979. Iraq’s military buildup had, by thestart of the war, boasted some 200,000 soldiers, 2,700 tanks, 1,000 artillerypieces, and 330 planes. By contrast,Iranian forces consisted of 150,000 soldiers, 1,700 tanks, 1,000 artillerypieces, and 440 planes.

Foreign Support Thewar saw the involvement of the two major superpowers, as both the United States and the Soviet Union, in the Cold War context, sought to gain favorablepolitical, military, and economic outcomes from the conflict. The Soviet Union, long a supplier of militaryweapons to Iraq, backedSaddam, and also sought (unsuccessfully) to establish close ties with Iran. The United States initially was averse to both sides of the war,viewing Iraq as a Sovietsatellite and an enemy of Israel,and Iranas an anti-American fanatical Islamic state. With the breakdown of relations with Iranresulting from the Tehran hostage crisis, the United States threw its support (somewhatambivalently) behind Iraq.

Like the United States,Persian Gulf monarchies were disinclined toward either side in the war,opposing Iraq’s powerambitions and loathing Iraneven more, because of Ayatollah Khomeini’s view that monarchical governmentswere un-Islamic, and encouraged their overthrow. But with Irantaking the military initiative by 1982, the Gulf monarchies, particularly Saudi Arabia, Kuwait,and the United Arab Emirates,became alarmed at a potential Iranian victory and released large sums of money,by way of loans, to Iraq. Israelalso was averse to either side, as both countries held anti-Zionist policies,but ultimately supported Iran,viewing the Iraqi government’s more pronounced military involvement in theArab-Israeli wars as the bigger threat.

Very few other countries were inclined to support Iran, which wasconsidered an outcast in the international community and, throughout the comingwar, would experience difficulty procuring weapons and spare parts for itsAmerican-made military equipment. MostArab League states backed predominantly Arab Iraq against “Persian” (i.e.non-Arab) Iran. However, two Arab countries, Syria and Libya,backed and militarily supported Iran. Syriaand Iraq had a long historyof mutual distrust, while Libya,an enemy of Iran’s deposedShah, had welcomed the Iranian Revolution and established close ties with Iran’s Islamicgovernment. North Korea also sold weapons to Iran. Many other countries (e.g. China, the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia, Portugal, etc.), directly orthrough third-party arms dealers, sold weapons to both sides of the war.

Between 1985 and 1987, in an elaborate clandestinetransaction, the United Statesprovided weapons to Iran inexchange for the release of American hostages in Lebanon. This event, known as the Iran-Contra Affair,generated a breach in U.S.laws and led to a number of United StatesCongressional investigations involving high-level U.S. administration officials.

War An escalationof hostilities, including artillery exchanges and air attacks, took place inthe period preceding the outbreak of war. On September 22, 1980, Iraqopened a full-scale offensive into Iranwith its air force launching strikes on ten key Iranian airbases, a move aimedat duplicating Israel’sdevastating and decisive air attacks at the start of the Six-Day War in1967. However, the Iraqi air attacksfailed to destroy the Iranian air force on the ground as intended, as Iranianplanes were protected by reinforced hangars. In response, Iranian planes took to the air and carried out retaliatoryattacks on Iraq’svital military and public infrastructures.

Throughout the war, the two sides launched many air attackson the other’s economic infrastructures, in particular oil refineries anddepots, as well as oil transport facilities and systems, in an attempt todestroy the other side’s economic capacity. Both Iran and Iraq weretotally dependent on their oil industries, which constituted their main sourceof revenues. The oil infrastructureswere nearly totally destroyed by the end of the war, leading to the nearcollapse of both countries’ economies. Iraq was much more vulnerable, because of itslimited outlet to the sea via the Persian Gulf,which served as its only maritime oil export route.

Iran,which possessed a powerful navy, imposed a naval blockade around the PersianGulf, effectively land-locking Iraq,while Syria, Iran’s ally, closed down the Kirkuk-Banias oilpipeline, through which Iraqexported its petroleum via Syria. Iraqwas left with the Kirkuk-Ceyhan outlet through Turkey,which also became vulnerable to attack later in the war when Iraqi Kurds ofnorthern Iraq rose up inrebellion and became allied with Iran in the war.

Together with its air attacks on the first day of the war,Iraqi ground forces launched simultaneous offensives along three fronts: north,central, and south. The northern frontadvanced east of Sulaymaniyah, aimed at protecting northern Iraq’s vital installations, including the Kirkuk oil fields andDarbandikhan Dam. The central front alsowas strategically defensive and consisted of two operations, one in the norththat advanced and successfully took Qasr-e Shirin toward the approaches of theZagros Mountains, intended to guard the Baghdad-Tehran Highway; and one in thesouth that occupied Mehran, an important junction in Iran’snorth-south road near the border with Iraq.

The southern front was the focus of the invasion, where fiveIraqi divisions attacked the petroleum resource-rich Iranian province of Khuzestan,which generated 90% of Iran’soil production. Iraqi forces usedbridging equipment to cross the Shatt al-Arab and once on the Iranian side ofthe river, met little opposition and thus made rapid progress towardKhoramshahr and Susangerd. Iran was caughtoff-guard by the invasion and had stationed only an undermanned force to defendKhuzestan.

March 4, 2021

March 4, 1913 – Greek and Ottoman forces clash at Bizani during the First Balkan War

The Greek Army of Epirus, having been reinforced to 41,000soldiers, began its offensive on Iaonnina. On March 6, 1913, the Greeks broke through the Ottoman lines at Bizaniafter three days of fighting. Iaonnina fell soon thereafter. The Greek Army then advanced north, capturingsections of southern Albania.

On April 20, 1913, peace negotiations in London resumed. This time, the European powers (Britain, France,Germany, Austria-Hungary, Italy,and Russia)applied strong pressure, forcing the warring sides to accept a preparedagreement (the Treaty of London), which was signed on May 30, 1913 andofficially ended the war. The treaty’smost important provision forced the Ottoman Empireto cede to the Balkan League all European territory west of the Enos-MidiaLine.

The Ottoman government complied and withdrew its forces fromthe Balkans, thus ending nearly five centuries of Ottoman rule in practicallyall of Europe. After further deliberations and under strong insistence of Austria-Hungary and Italy,on July 29, 1913, the European powers agreed to recognize the independence of Albania, where local Albanian nationalists hadpreviously (on November 28, 1912) declared the province’s secession from the Ottoman Empire. Asa result, Serbia, Greece, and Montenegrowithdrew their forces from occupied areas in Albania, again after beingstrong-armed diplomatically by the European powers.

The partitioning of other Balkan territories was left to thediscretion of the Balkan League. Nevertheless, the unexpected birth of the Albanian state disrupted theSerbian-Bulgarian pre-war secret partition agreement of the Balkan region. In particular, Bulgaria was disappointed atits less than expected territorial gains in the war, more so in relation toGreece whose forces had performed exceedingly (and surprisingly) well, and hadgained a larger share of the conquered territories in southern Macedonia thatotherwise would have been won by Bulgaria. For this reason, Bulgariaput pressure on Serbia and Greece to turnover some of the conquered territories, which the latter two refused.

The stage thus was set for the resumption of hostilities,the Second Balkan War.

(Taken from First Balkan War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 3)

Background of theFirst Balkan War At the start of the twentieth century, the Ottoman Empirewas a spent force, a shadow of its former power of the fifteenth and sixteenthcenturies that had struck fear in Europe. The empire did continue to hold vastterritories, but only tolerated by competing interests among the Europeanpowers who wanted to maintain a balance of power in Europe. In particular, Britainand Francesupported and sometimes intervened on the side of the Ottomans in order torestrain expansionist ambitions of the emerging giant, the Russian Empire.

In Europe, the Ottomans hadlost large areas of the Balkans, and all of its possessions in central andcentral eastern Europe. By 1910, Serbia, Bulgaria,Montenegro, and Greecehad gained their independence. As aresult, the Ottoman Empire’s last remaining possession in the European mainlandwas Rumelia (Map 4), a long strip of the Balkans extending from Eastern Thrace,to Macedonia, and into Albania in the Adriatic Coast. And even Rumelia itself was coveted by thenew Balkan states, as it contained large ethnic populations of Serbians,Belgians, and Greeks, each wanting to merge with their mother countries.

The Russian Empire, seeking to bring the Balkans into itssphere of influence, formed a military alliance with fellow Slavic Serbia, Bulgaria, and Montenegro. In March 1912, a Russian initiative led to aSerbian-Bulgarian alliance called the Balkan League. In May 1912, Greece joined the alliance when theBulgarian and Greek governments signed a similar agreement. Later that year, Montenegrojoined as well, signing separate treaties with Bulgariaand Serbia.

The Balkan League was envisioned as an all-Slavic alliance,but Bulgaria saw the need tobring in Greece, inparticular the modern Greek Navy, which could exert control in the Aegean Seaand neutralize Ottoman power in the Mediterranean Sea,once fighting began. The Balkan Leaguebelieved that it could achieve an easy victory over the Ottoman Empire, for the following reasons. First, the Ottomans currently were locked in a war with the ItalianEmpire in Tripolitania (part of present-day Libya), and were losing; andsecond, because of this war, the Ottoman political leadership was internallydivided and had suffered a number of coups.

Most of the major European powers, and especially Austria-Hungary, objected to the Balkan Leagueand regarded it as an initiative of the Russian Empire to allow the RussianNavy to have access to the Mediterranean Sea through the Adriatic Coast. Landlocked Serbiaalso had ambitions on Bosnia and Herzegovinain order to gain a maritime outlet through the AdriaticCoast, but was frustrated when Austria-Hungary, which had occupiedOttoman-owned Bosnia and Herzegovina since 1878, formally annexed theregion in 1908.

The Ottomans soon discovered the invasion plan and preparedfor war as well. By August 1912,increasing tensions in Rumelia indicated an imminent outbreak of hostilities.

March 3, 2021

March 3, 1918 – World War I: The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk is signed, which ends the war between Russia and the Central Powers

In Soviet Russia, the Bolsheviks, whose revolution hadsucceeded partly on their promises to a war-weary citizenry and military todisengage from World War I, declared its pacifist intentions to the CentralPowers. A ceasefire agreement was signedon December 15, 1917 and peace talks began a few days later in Brest-Litovsk(present-day Brest, in Belarus).

However, the Central Powers imposed territorial demands thatthe Russian government deemed excessive. On February 17, 1918, the Central Powers repudiated the ceasefireagreement, and the following day, Germanyand Austria-Hungaryrestarted hostilities against Russia,launching a massive offensive with one million troops in 53 divisions alongthree fronts that swept through western Russiaand captured Ukraine Belarus, Lithuania,Latvia, and Estonia. German forces also entered Finland, aidingthe non-socialist paramilitary group known as the “White Guards” in defeatingthe socialist militia known as “Red Guards” in the Finnish Civil War. Eleven days into the offensive, the northernfront of the German advance was some 85 miles from the Russian capital ofPetrograd (on March 12, 1918, the Russian government transferred its capital toMoscow).

On February 23, 1918, or five days into the offensive, peacetalks were restarted at Brest-Litovsk, with the Central Powers demanding fromRussia even greater territorial and military concessions than in the December1917 negotiations. After heated debatesamong members of the Council of People’s Commissars (the highest Russiangovernmental body) who were undecided whether to continue or end the war, atthe urging of its Chairman, Vladimir Lenin, the Russian government acquiescedto the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. On March3, 1918, Russian and Central Powers representatives signed the treaty, whosemajor stipulations included the following: peace was restored between Russiaand the Central Powers comprising Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and theOttoman Empire; Russia relinquished possession of Finland (which was currentlyembroiled in a civil war), Belarus, Ukraine, and the Baltic territories ofEstonia, Latvia, and Lithuania – Germany and Austria-Hungary were to determinethe future of these territories; and Russia also ceded to the Ottoman Empirethe regions of Ardahan, Kars, and Batumi in the Caucasus.

Subsequently, German forces occupied Estonia, Latvia,Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine,and Poland,establishing semi-autonomous governments in these territories that weresubordinate to the authority of the German monarch, Kaiser Wilhelm II. The German occupation of the region allowedthe realization of the Germanic vision of “Mitteleuropa”, an expansionist ambitionaimed at unifying all Germanic and non-Germanic peoples of Central Europe into a greatly enlarged and powerful German Empire. In support of Mitteleuropa, in the Balticregion, the Baltic German nobility proposed to set up the United Baltic Duchy,a semi-autonomous political entity consisting of present-day Latvia and Estonia that would be voluntarilyintegrated into the German Empire. Theproposal was not implemented, but German military authorities set up localcivil governments under the authority of the Baltic German nobility or ethnicGermans.

Although the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in March 1918 ended Russia’sparticipation in World War I, the war was still ongoing in other fronts – mostnotably on the Western Front, where for four years, German forces were boggeddown in inconclusive warfare against the British, French and other AlliedArmies. After transferring substantialnumbers of now freed troops from the Russian front to the Western Front, inMarch 1918, Germany launchedthe Spring Offensive, a major attack into Franceand Belgiumin an effort to bring the war to an end. After four months of fighting, by July 1918, despite achieving someterritorial gains, the German offensive had ground to a halt.

The Allied Powers then counterattacked with newly developedbattle tactics and weapons and gradually pushed back the now spent anddemoralized German Army all across the line into German territory. The entry of the United States into the war on the Allied side was decisive, asincreasing numbers of arriving American troops with the backing of the U.S.weapons-producing industrial power contrasted sharply with the greatly depletedwar resources of both the Entente and Central Powers. The imminent collapse of the German Army wasgreatly exacerbated by the outbreak of political and social unrest at the homefront (the German Revolution of 1918-1919), leading to the sudden end of theGerman monarchy with the abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm II on November 9, 1918and the establishment of an interim government (under moderate socialistFriedrich Ebert), which quickly signed an armistice with the Allied Powers onNovember 11, 1918 that ended the combat phase of World War I.

As the armistice agreement required that Germany demobilizethe bulk of its armed forces as well as withdraw the same to the confines ofthe German borders within 30 days, the German government ordered its forces toabandon the occupied territories that had been won in the Eastern Front. After Germany’scapitulation, Russiarepudiated the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk and made plans to seize back theEuropean territories it previously had lost to the Central Powers. An even far more reaching objective was forthe Bolshevik government to spread the communist revolution to Europe, first bylinking up with German communists who were at the forefront of the unrest thatcurrently was gripping Germany. Russian military planners intended theoffensive to merely follow in the heels of the German withdrawal from Eastern Europe (i.e. to not directly engage the Germansin combat) and then seize as much territory before the various local ethnicnationalist groups in these territories could establish a civilian government.

March 2, 2021

March 2, 1969 – Sino-Soviet Border Conflict: Soviet and Chinese units skirmish on Damansky/Zhenbao Island

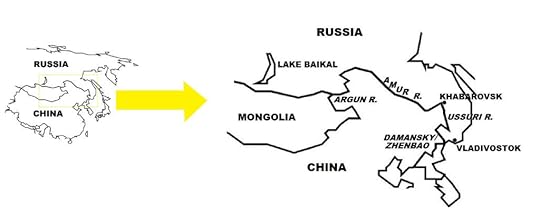

On March 2, 1969, Soviet border troops were sent toDamansky/Zhenbao Island to expel 30 Chinese soldiers who had landed on theisland. Unbeknown to the Soviets, alarge Chinese force, (300 soldiers, according to the Soviets) which was hiddenand waiting in ambush in the nearby forest, opened fire on the Soviets. Fighting then broke out, with other unitsfrom both sides joining the fray. Chinese units used artillery and small arms fire from their side of the Ussuri River,while the Soviets sent reinforcements to Damansky/Zhenbao Island from theirside of the river.

(Taken from Sino-Soviet Border Conflict – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 5)

What became the trigger for the escalation of border clashesthat nearly led to total war between China and the Soviet Union was thedisputed but nondescript Damansky Island (Zhenbao Island to the Chinese), asmall (0.74 square kilometers) 1½-mile long by ½-mile wide island located inthe Ussuri River between the Soviet bank in the east and the Chinese bank inthe west. By the terms of a treatysigned in the 19th century, Damansky/Zhenbao Island belonged to the Soviet Union. Theisland was uninhabited, and also experienced flooding from seasonal rains. Both the Chinese and Soviets regularly sentpatrols to reconnoiter the island.

During border negotiations in 1964, the Soviet Union agreedto cede the island to China,but then retracted this offer when talks broke down. Thereafter, the island became a flashpointfor armed clashes. In March 1969, China accused the Soviet Union of intruding into Damansky/Zhenbao Island sixteen times duringa two-year period in January 1967-March 1969. In December 1968 and again in January 1969, Soviet border guards usednon-lethal force to expel Chinese patrols from the island. More border incidents occurred in February1969.

Then on March 2, 1969, Soviet border troops were sent toDamansky/Zhenbao Island to expel 30 Chinese soldiers who had landed on theisland. Unbeknown to the Soviets, alarge Chinese force, (300 soldiers, according to the Soviets) which was hiddenand waiting in ambush in the nearby forest, opened fire on the Soviets. Fighting then broke out, with other unitsfrom both sides joining the fray. Chinese units used artillery and small arms fire from their side of the Ussuri River,while the Soviets sent reinforcements to Damansky/Zhenbao Island from theirside of the river.

A Chinese military report after the incident stated that theSoviets fired the first shots. Morerecent information indicates that the Chinese military planned the incident,and used elite army units with battle experience to ambush the Sovietpatrol. In this way, China hoped to retaliate for the many Sovietprovocations, and also to signal that Chinawould not be intimidated by the Soviet Union.

The two sides released different casualty figures for theDamansky/Zhenbao incident, although the Soviets may have suffered greaterlosses, at 59 dead and 94 wounded. Boththe Chinese and Soviets claimed victory. The two sides also raised strong diplomatic protests against the other,accusing the other side of starting the incident. The Soviet Union accused China of being“reckless and provocative”, while China warned that if the Soviet Unioncontinued to “provoke armed conflicts”, China would respond with “resolutecounter-blows”.

Sensationalist news reports by the media from the two sidesstirred up the general population in both countries. On March 3, 1969 in Beijing, large protests were held outside theSoviet Embassy, and Soviet diplomatic personnel were harassed. In the Soviet Union, demonstrations were heldin Khabarovsk and Vladivostok. In Moscow,angry crowds hurled stones, ink bottles, and paint at the Chinese Embassy.

On March 11, 1969 in Beijing,demonstrators besieged the Soviet Embassy in protest for the attack on theChinese Embassy. Then when Soviet mediareported that captured Russian soldiers during the Damansky/Zhenbao incidenthad been tortured and executed, and their bodies mutilated, largedemonstrations consisting of 100,000 people broke out in Moscow. Other mass assemblies also occurred in other Russian cities.

On March 15, 1969, a second (and larger) clash broke out inDamansky/Zhenbao Island, where both sides sent a force of regimental strength,or some 2,000-3,000 troops. The Chineseclaimed that the Soviets fielded one motorized infantry battalion, one tankbattalion, and four heavy-artillery battalions, or a total of over 50 tanks andarmored vehicles, and scores of artillery pieces. The two sides again claimed victory in the10-hour battle, and also accused the other side of firing the first shots. Both sides suffered heavy casualties.

The Soviets lost a number of armored vehicles, and failed toexpel the Chinese from the island. OnMarch 17, 1969, some 70 Soviet soldiers who were sent to retrieve a disabledT-62 tank were forced to retreat. TheChinese subsequently recovered the Soviet tank and transported it to Beijing where it was puton public display. Casualty figures forthe March 15-17 battles are disputed. The Soviets place their own losses at 58 dead and 94 wounded. The Chinese place their losses at 29 dead, 62wounded, and one missing. Foreignindependent sources provide much higher combined total casualty figures, from800 to 3,000 soldiers killed for both sides.

As in the first incident (March 2), more recent Chinesesources indicate that the Chinese Army had prepared for the second encounter(March 15). Chinese authorities hadanticipated that the Soviets would return in force. The Chinese Army therefore sent a greaternumber of Chinese elite units, and fortified its side of the island with landmines. With these preparations, theChinese succeeded in repelling the Soviets, who had attacked using armoredunits. After the encounter, the Sovietsbegan an extended artillery barrage of Chinese positions across the river, andhit targets as far as seven kilometers inside China.

The two incidents generated different reactions in theChinese and Soviet governments. In China, Mao madeefforts to prevent the crisis from escalating further. He ordered Chinese border troops not toretaliate to the Soviet artillery shelling of Chinese positions inDamansky/Zhenbao Island, and at the Chinese side of the Ussuri River. In Moscow, theSoviet government was thoroughly provoked by the two incidents, viewing them asa direct challenge from China.

However, Soviet authorities were divided as to theappropriate response. The ForeignMinistry called for caution, but the military wanted aggressive action. On May 24, 1969, because of continued borderincidents by Russian troops, Chinafiled a diplomatic protest, accusing the Soviet Unionof provoking war. On May 29, the Sovietgovernment threatened to go to war with China, but also called for talksbetween the two sides.

As tensions increased, so did troop deployment to thedisputed regions. Soon, 800,000 Chineseand 700,000 Soviet troops were deployed at the border. The Soviets continued to initiate borderincidents, apparently to provoke a wider conflict. On August 13, 1969 in the Tieliketi Incident,300 Soviet troops, supported by air and armored units, entered China’sTieliketi area, located in Xinjiang region, in the western border. There, they ambushed and killed 30 Chineseborder guards.

By now, the Soviet Union was preparing for war, andincreased its forces in Mongoliaand carried out a large military exercise in the Far East. Soviet authorities notified Eastern Bloccountries that Russian planes could launch an air strike on China’s nuclear facility in Lop Nur, Xinjiang. In Washington, D.C., aSoviet diplomatic official, while dining with a U.S. State Department officer,broached the planned Soviet attack on China’s nuclear site, to gaugeAmerican reaction. The U.S. official reacted negatively, and subsequentU.S. warnings of interveningmilitarily if the Soviet Union attacked China, would have far-reachingrepercussions in the ongoing Cold War.

Meanwhile in Beijing, Chineseauthorities were concerned about the growing threat of war with the Soviet Union. Despite appearing defiant, and warning Russiathat it too had nuclear weapons, Chinawas unprepared to go to war, and its military was far weaker than that of the Soviet Union. Exacerbating China’sposition was its ongoing Cultural Revolution, which was causing seriousinternal unrest.

March 1, 2021

March 1, 1941 – World War II: Bulgaria joins the Axis Powers

On March 1, 1941, Bulgaria joined the Axis by signing the Tripartite Pact. Germany had long pressured Bulgaria into allying with the Axis, but the Bulgarian government balked at getting involved in the war. However, with the Italian offensive into Greece being turned back, Adolf Hitler decided to intervene, and demanded the passage of German forces into Bulgaria for the invasion of Greece (and later including Yugoslavia). Recognizing futility to stop a German attack into its territory, the Bulgarian government acquiesced, and joined the Tripartite Pact with assurances of being given Greek territory and continued diplomatic relations with its neighbors Turkey and the Soviet Union. At that time, Germany and the Soviet Union had a ten-year non-aggression pact.

(Taken from The Balkan Campaign – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

In August 1940, Hitler gave secret instructions to hismilitary high command to prepare a plan for the invasion of the Soviet Union, to be launched in the spring of 1941. In October 1940-January 1941, the Germanslaunched fierce air attacks on Britain,which failed to force the latter to capitulate as Hitler had hoped. Hitler then suspended his planned invasion ofBritainand instead focused on other ways to bring it to its knees. He turned to the Mediterranean Sea, whosecontrol by Germany and Italy would have the effect of cutting off Britain from its colonies in Africa and Asia viathe Suez Canal. In this plan, German forces would captureGibraltar through Spain,thus sealing off the western end of the Mediterranean Sea, while the ItalianArmy in Libya would captureBritish-controlled Egypt aswell as the Suez Canal, sealing off the eastern end of the Mediterranean Sea. German forces wouldjoin in the final stages of the Italian offensive.

As the German military formulated the invasion plan of theSoviet Union and the means to knock Britain out of the war, Hitler wasdetermined that no complications arose that would interfere with theseobjectives. Foremost, Hitler had noappetite for turmoil to break out in southeastern Europe,especially the highly volatile Balkan region, the “powder keg” that had sparkedWorld War I. Politically andstrategically, Hitler wanted stability in the Balkans to keep away the SovietUnion, with whom Germanyhad a tenuous non-aggression pact. Conflict in the Balkans would most likely prompt intervention by Russia, whichtraditionally held a strong influence there.

Hitler had long stated that he had no territorial ambitionson the Balkans. Instead, Germany’s main interest there was purelyeconomic, as the Balkan countries were Germany’s biggest partners,supplying the latter with food and mineral resources. But of the greatest importance to Hitler werethe Ploiesti oil fields in Romania, whichprovided the German military and industry with vital petroleum products.

Germanyand Italy mediated twoterritorial disputes involving Romaniaand its neighbors: on August 21, 1940, Romaniawas persuaded to cede Southern Dobruja to Bulgaria,and on August 30, 1940, it also relinquished one-third of Transylvania to Hungary. A few weeks earlier, in late June-early July1940, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin had used strong-arm tactics to force Romania to cede its northeastern regions ofBessarabia and Northern Bukovina to the Soviet Union.

Meanwhile, Hitler strove to convince Mussolini to stall thelatter’s territorial ambitions in the Balkans. Mussolini had long viewed that in the German-Italian partition ofEurope, southeastern Europe and the Balkansfell inside the Italian sphere of control. Italian forces had invaded Albaniain April 1939 (separate article), and after the fall of France in June 1940, Mussolini exerted pressureon Greece and Yugoslavia, andthreatened them with invasion. At thattime, Hitler was able to convince Mussolini to suspend temporarily his Balkanambitions and instead focus Italian efforts on defeating the British in North Africa.

But on October 7, 1940, at the request of Romanian dictatorIon Antonescu, German forces entered Romaniato guard against a Soviet invasion; for Hitler, it was to protect the vital Ploiesti oil fields. Mussolini was outraged by this German action,as he believed that Romaniafell inside his zone of control. Alsofor Mussolini, Hitler’s move into Romania was only the latest in along list of stunts that had been made without previously consulting him, andone that had to be reciprocated, or as Mussolini put it, “to repay him [Hitler]with his own coin”. Hitler had invaded Poland, Denmark,Norway, France, and the Low Countries without informing Mussolini beforehand.

On October 28, 1940, Mussolini, without notifying Hitler,launched the invasion of Greece(previous article), despite insufficient military preparation and against thecounsel of his top generals. Theoperation was a disaster, as the motivated Greek Army threw back the Italiansto Albania,and then launched its own offensive. Within three months, the Greeks occupied a quarter of Albanianterritory. Greece had declared its neutralityat the start of World War II. Butbecause of the Italian invasion, the Greek government turned to Britain forassistance. In early November 1940,British forces had arrived, and occupied two strategically important Greekislands, Crete and Limnos.

The unexpected Italian attack on Greece and likelihood of Britishintervention in the Balkans shocked Hitler, seeing that his efforts to try andmaintain peace in the region had failed. His prized Ploesti oil fields and the whole southeastern Europe were now vulnerable. On November 4, 1940, Hitler decided to becomeinvolved in Greecein order to bail out his beleaguered ally Mussolini and to forestall the British. On November 12, 1940, the German High Commandissued Directive No. 18, which laid out the German plan to contain the Britishin the Mediterranean: German forces would invade northern Greece and Gibraltar in January 1941, and thenassist the Italians in attacking Egypt in the fall of 1941. However, Spain’spro-Axis dictator General Francisco Franco refused to allow German troops into Spain, forcing Germanyto suspend its invasion of Gibraltar. On December 13, 1940, the German militaryissued Directive No. 20, which finalized the invasion of Greece undercodename Operation Marita. In the finalplan, German forces in Bulgaria would open a second front in northeasternGreece and capture the whole Greek northern coast, link up with the Italians inthe northwest, and if necessary, push south toward Athens and seize the rest ofGreece. Operation Marita was scheduledfor March 1941; however, delays would cause the invasion to be launched onemonth later.

For the invasion of Greece,Hitler considered it necessary to bring into the Axis fold the governments of Hungary, Romania,Bulgaria, and Yugoslavia,notwithstanding their stated neutrality at the start of the World War II. With their cooperation, German forces wouldcross their territories through Central and Eastern Europe,as well as control their military-important infrastructures, such as airfieldsand communications systems. Hungary, which had benefited territorially inthe German seizure of Czechoslovakiaand Axis arbitration of Transylvania, was drawn naturally to Germany. On November 20, 1940, the Hungariangovernment joined the Tripartite Pact . Three days later, Romaniaalso joined the Pact, as Romanian leader Antonescu was motivated to do so byfear of a Soviet invasion. In succeedingmonths, large numbers of German forces and weapons, passing through Hungary, would assemble in Romania, mainly for the planned invasion of the Soviet Union (whose operational plan would be finalizedin December 1940 under the top-secret Operation Barbarossa).

Bulgariabalked at joining the Pact and thus be openly associated with the Axis, andalso was concerned that participating in the invasion of Greece would leave its eastern border vulnerableto an attack by Turkey,which was allied with Greece. The Bulgarians also were aware of a Sovietplan to capture Varna, Bulgaria’s Black sea port, which the Sovietswould use to seize control of the Turkish Straits, which was a source of along-standing dispute between the Soviet Union and Turkey.

However, Hitler exerted strong diplomatic pressure on Bulgaria andalso promised to protect Bulgarian territorial integrity. Bulgaria acquiesced and agreed toallow German troops to enter Bulgarian territory. On February 28, 1941, German engineeringcrews bridged the Danube River at the Romanian-Bulgarian border, and the firstGerman units crossed into Bulgariaand continued to that country’s eastern border. The next day, March 1st, Bulgariajoined the Tripartite Pact, officially joining the Axis. On March 2, 1941, German forces involved inOperation Marita entered Bulgariaand proceeded south to the Bulgarian-Greek border.

To assure Turkey of German intentions, Hitler wrote to theTurkish government to explain that the German presence in Bulgaria was directed at Greece. To further allay the Turks, German troopswere positioned far from the Turkish border. The Turkish government accepted the German clarification, and agreed tostand down its forces during the German attack on Greece.

Meanwhile, Greecewas aware of German plans, and in the previous months, held talks with Britain and Yugoslavia to formulate a commonstrategy against the anticipated German attack. The dilemma for Greece was that by March 1941, the greater part of itsmilitary forces were still tied down against the Italians in southern Albania,leaving insufficient units to defend the rest of the country’s northernborder. At the request of the Greekgovernment, Britain and itsdominions, Australia and New Zealand, sent 58,000 troops to Greece; this force arrived in March 1941 anddeployed in Greece’snorth central border.

With regards to Yugoslavia, Hitler exerted greateffort to try and persuade the officially neutral but Allied-leaning governmentof Yugoslav Prime Minister Dragisha Cvetkovic to join the Axis. In a series of high-level meetings between thetwo countries which even included Hitler’s participation, the Germans offeredsizable rewards to Yugoslaviafor joining the Axis, including Greek territory that would include Salonicawhich would give Yugoslaviaaccess to the Aegean Sea. Talks went nowhere until Hitler met withPrince Paul on March 4, 1941, which led two weeks later to the Yugoslavgovernment agreeing to join the Axis. OnMarch 25, 1941, Yugoslaviasigned the Tripartite Pact, motivated by a secret clause in the agreement thatcontained three stipulations: the Axis promised to respect Yugoslaviansovereignty and territorial integrity, the Yugoslavian military would not berequired to assist the Axis, and Yugoslavia would not be required toallow Axis forces to pass through its territory. But two days later, March 27, the pro-AlliedSerbian military high command deposed the Yugoslav government and installeditself in a military regime, arrested Prince Paul, and named the 17-year oldminor crown prince as King Peter II. Thenew military government assured Germanythat Yugoslaviawanted to maintain friendly ties between the two countries, albeit that itwould not ratify the Tripartite Pact. Anti-German mass demonstrations broke out in Belgrade and other Serbian cities.

As a result of the coup, a furious and humiliated Hitlerbelieved that Yugoslavia hadtaken a stand favoring the Allies, despite the new Yugoslav government’sconciliatory position toward Germany. On March 27, 1941, just hours after the coup,Hitler convened the German military high command and stated his intention to“destroy Yugoslaviaas a military power and sovereign state”. He ordered the formulation of an invasion plan for Yugoslavia, which was to be carried out togetherwith the attack on Greece. Despite the time constraint (the attack onGreece was set to be launched in ten days, April 6, 1941), the German militaryfinalized a lightning attack for Yugoslavia, code-named Operation 25, to beunder taken in coordination with the operation on Greece.

Hitler invited Bulgariato participate in the attack on Yugoslavia,but the Bulgarian government declined, citing the need to defend itsborders. As well, Hungary demurred, as it had just recently signeda non-aggression pact with Yugoslavia,but it agreed to allow the German invasion forces to mass in its southwesternborder with Yugoslavia. Romania was not asked to join theinvasion.

Mussolini, after conferring with Hitler, agreed toparticipate, and the Italian forces were to undertake the following:temporarily cease operations at the Albanian front; protect the flank of theGerman forces invading from Austriato Slovenia; seize Yugoslavterritories along the Adriatic coast; and link up with German forces for theinvasion of Greece.

On April 3, 1941, Yugoslaviasent emissaries to Moscow to try and arrange amutual defense treaty with the Soviet Union. Instead, on April 5, the Soviet governmentagreed only to a treaty of friendship and non-aggression with Yugoslavia,which did not promise Soviet protection in case of foreign aggression. As a result, Hitler was free to invade Yugoslaviawithout fear of Soviet intervention. OnApril 6, 1941, Germany and Italy launched the invasions of Yugoslavia and Greece, discussed separately in thenext two chapters.

February 28, 2021

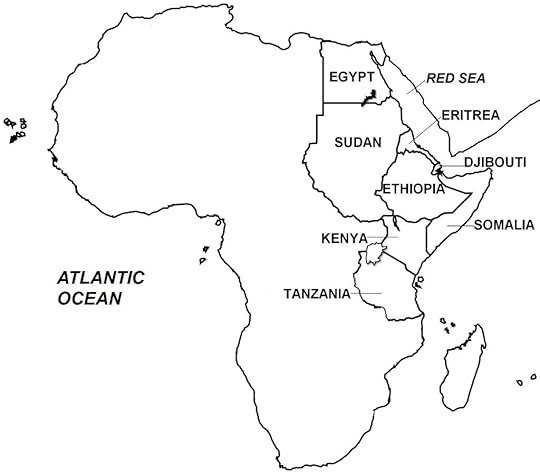

February 28, 1974 – Ethiopian Civil War: Prime Minister Aklilu Habte-Wold steps down

In January 1974, in what became the first of a series ofdecisive events, soldiers stationed at Negele, Sidamo Province, mutinied inprotest of low wages and other poor conditions; in the following days, militaryunits in other locations mutinied as well. In February 1974, as a result of rising inflation and unemployment anddeteriorating economic conditions resulting from the global oil crisis of theprevious year (1973), teachers, workers, and students launched protestdemonstrations and marches in Addis Ababa demanding price rollbacks, higher labor wages,and land reform in the countryside. These protests degenerated into bloody riots. In the aftermath, on February 28, 1974,long-time Prime Minister Aklilu Habte-Wold resigned and was replaced byEndalkachew Makonnen, whose government raised the wages of military personneland set price controls to curb inflation. Even so, the government, which was controlled by nobles, aristocrats,and wealthy landowners, refused or were unaware of the need to implement majorreforms in the face of growing public opposition.

In March 1974, a group of military officers led by ColonelAlem Zewde Tessema formed the multi-unit “Armed Forces Coordinating Committee”(AFCC) consisting of representatives from different sectors of the Ethiopianmilitary, tasked with enforcing cohesion among the various forces and assistingthe government in maintaining authority in the face of growing unrest. In June 1974, reformist junior officers ofthe AFCC, desiring greater reforms and dissatisfied with what they saw was theAFCC’s close association with the government, broke away and formed their owngroup.

Ethiopia and nearby countries.

Ethiopia and nearby countries.(Taken from Ethiopian Civil War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Background Thislatter group, which took the name “Coordinating Committee of the Armed Forces,Police, and Territorial Army, soon grew to about 110 to 120 enlisted men andofficers (none above the rank of major) from the 40 military and security unitsacross the country, and elected Majors Mengistu Haile Mariam and Atnafu Abate as its chairman andvice-chairman, respectively. This group,which became known simply as Derg (an Ethiopian word meaning “Committee” or“Council”), had as its (initial) aims to serve as a conduit for variousmilitary and police units in order to maintain peace and order, and also touphold the military’s integrity by resolving grievances, disciplining errantofficers, and curbing corruption in the armed forces.

Derg operated anonymously (e.g. its members were notpublicly known initially), but worked behind such populist slogans as “EthiopiaFirst”, “Land to the Peasants”, and “Democracy and Equality to all” to gainbroad support among the military and general population. By July 1974, the Derg’s power was felt notonly within the military but in the government itself, and Haile Selassie wasforced to implement a number of political measures, including the release ofpolitical prisoners, the return of political exiles to the country, passage ofa new constitution, and more critically, to allow Derg to work closely with thegovernment. Under Derg pressure, thegovernment of Prime Minister Makonnen collapsed; succeeding as Prime Ministerwas Mikael Imru, an aristocrat who held leftist ideas.

Haile Selassie’s concessions to the Derg included measuresto investigate government corruption and mismanagement. In the period that followed, Derg arrestedand imprisoned many high-ranking imperial, administrative, and militaryofficials, including former Prime Ministers Habte-Wold and Makonnen, Cabinetmembers, military generals, and regional governors. In August 1974, a proposed constitution thatcalled for establishing a constitutional monarchy was set aside. Now operating virtually with impunity, theDerg took aim at the imperial court, dissolving the imperial governing councilsand royal treasury, and seizing royal landholdings and commercial assets. By this time, Haile Selassie’s governmentvirtually had ceased to exist; de facto power was held by the military, or moreprecisely, by Derg.

The culmination of events occurred when Haile Selassie wasaccused of deliberately denying the existence of a widespread famine thatcurrently was ravaging Ethiopia’sWollo province, which already had killed some 40,000 to 80,000 to as many as200,000 people. Conflicting reportsindicated that Haile Selassie was not aware of the famine, was fully aware ofit, or that government administrators withheld knowledge of its existence fromthe emperor. By August 1974, largeprotest demonstrations in Addis Ababawere demanding the emperor’s arrest. Finally on September 12, 1974, the Derg overthrew Haile Selassie in abloodless coup, leading away the frail, 82-year old ex-monarch to imprisonment.

The Derg gained control of Ethiopia but did not abolish themonarchy outright, and announced that Crown Prince Asfa Wossen, HaileSelassie’s son who was currently abroad for medical treatment, was to succeedto the throne as the new “king” on his return to the country. However, Prince Wossen rejected the offer andremained abroad. The Derg then withdrewits offer and in March 1975, abolished the monarchy altogether, thus ending the800 year-old Ethiopian Empire. (OnAugust 27, 1975, or nearly one year after his arrest, Haile Selassie passedaway under mysterious circumstances, with Derg stating that complications froma medical procedure had caused his death, while critics alleging that theex-monarch was murdered.)

The surreptitious means by which Derg, in a period of sixmonths, gained power by progressively dismantling the Ethiopian Empire andultimately deposing Haile Selassie, sometimes is referred to as the “creepingcoup” in contrast with most coups, which are sudden and swift. On September 15, 1974, Derg formally tookcontrol of the government and renamed itself as the Provisional MilitaryAdministrative Council (although it would continue to be commonly known asDerg), a ruling military junta under General Aman Andom, a non-member Derg whomthe Derg appointed as its Chairman; General Aman thereby also assumed the roleof Ethiopia’s head of state.

At the outset, Derg had its political leanings embodied inits slogans “Ethiopia First” (i.e. nationalism) and “Democracy and Equality toall”. Soon, however, it abolished theEthiopian parliament, suspended the constitution, and ruled by decree. In early 1975, Derg launched a series ofbroad reforms that swept away the old conservative order and began thecountry’s transition to socialism. InJanuary-February 1975, nearly all industries were nationalized. In March, an agrarian reform programnationalized all farmlands (including those owned by the country’s largestlandowner, the Ethiopian Orthodox Church), reduced farm sizes, and abolishedtenancy farming. Collectivizedagriculture was introduced and farmers were organized into peasantorganizations. (Land reform was fiercelyresisted in such provinces as Gojjam, Wollo, and Tigray, where most farmersowned their lands and tenant farming was not widely practiced.) In July 1975, all urban lands, houses, andbuildings were nationalized and city residents were organized into urbandwellers’ associations, known as “kebeles”, which would play a major role inthe coming civil war. Despite theextensive nationalization, a few private sector industries that were consideredvital to the economy were left untouched, e.g. the retail and wholesale trade,and import and export industries.

In April 1976, Derg published the “Program for the NationalDemocratic Revolution”, which outlined the regime’s objectives of transformingEthiopia into a socialist state, with powers vested in the peasants, workers,petite bourgeoisie, and anti-feudal and anti-monarchic sectors. An agency called the “Provisional Office forMass Organization Affairs” was established to work out the transformativeprocess toward socialism.

War The politicalinstability and power struggles that followed the Derg’s coming to power, theescalation of pre-existing separatist and Marxist insurgencies (as well as theformation of new rebel movements), and the intervention of foreign players,notably Somalia as well as Cold War rivals, the Soviet Union and United States,all contributed to the multi-party, multi-faceted conflict known as theEthiopian Civil War.

The Derg government underwent power struggles during itsfirst years in office. General Aman, thenon-Derg who had been named to head the government, immediately came intoconflict with Derg on three major policy issues: First, he wanted to reduce thesize of the 120-member Derg; Second, as an ethnic Eritrean, he was opposed tothe Derg’s use of force against the Eritrean insurgency; and Third, he opposedDerg’s plan to execute the imprisoned civilian and military officialsassociated with the former regime. InNovember 1974, Derg leveled charges against General Aman and issued a warrantfor his arrest. On November 23, 1974,General Aman was killed in a gunfight with government security personnel whohad been sent to arrest him.

February 27, 2021

February 27. 1976 – Western Sahara War: The Polisario Front declares independence

On February 26, 1976, Spainfully withdrew from Spanish Sahara, which henceforth became universally called Western Sahara (although the UN already had referred toit as such by 1975). As per theagreement, Moroccan forces occupied their designated region (which Morocco soon called its Southern Provinces; alsoin 1979, Morocco wouldinclude the southern zone after Mauritaniawithdrew); and Mauritanian troops occupied Titchla, La Guera, and later Dakhla(as the capital), of its newly designated Saharan province of Tirisal-Gharbiyya. Then on April 14, 1976,the two countries signed an agreement that formally divided the territory intotheir respective zones of occupation and control.

In the three-month period (November 1975–February 1976)during Spain’s withdrawaland replacement with Moroccan and Mauritanian administrations, tens ofthousands of Sahrawis fled to the Saharan desert, and subsequently into Tindouf, Algeria. On February 27, 1976, one day after Spain withdrew from the territory, the PolisarioFront declared the founding of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR),with a government-in-exile based in Algeria.

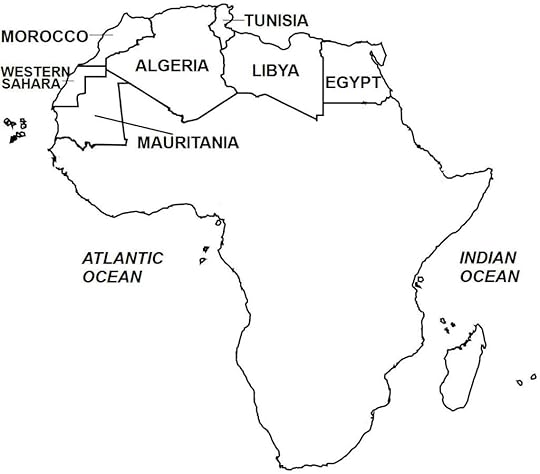

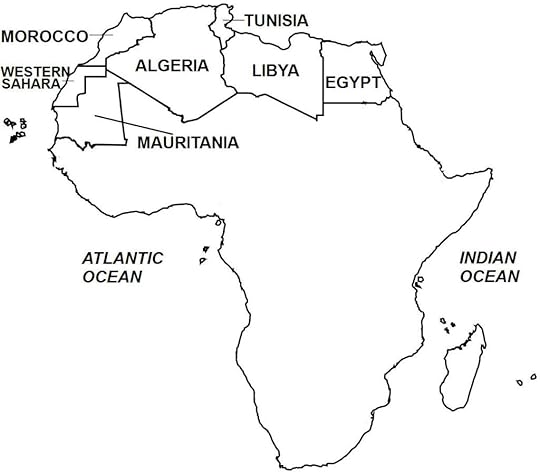

Map showing location of Western Sahara.

Map showing location of Western Sahara.(Taken from Western Sahara War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Background OnDecember 3, 1974, the UNGA passed Resolution 3292 declaring the UN’s interestin evaluating the political aspirations of Sahrawis in the Spanishterritory. For this purpose, the UNformed the UN Decolonization Committee, which in May – June 1975, carried out afact-finding mission in Spanish Sahara as well as in Morocco,Mauritania, and Algeria. In its final report to the UN on October 15,1978, the Committee found broad support for annexation among the generalpopulation in Morocco and Mauritania. In Spanish Sahara,however, the Sahrawi people overwhelmingly supported independence under theleadership of the Polisario Front, while Spain-backed PUNS did not enjoy suchsupport. In Algeria, the UN Committee foundstrong support for the Sahrawis’ right of self-determination.

Algeriapreviously had shown little interest in the Polisario Front and, in an ArabLeague summit held in October 1974, even backed the territorial ambitions of Morocco and Mauritania. But by summer of 1975, Algeria was openly defending thePolisario Front’s struggle for independence, a support that later would includemilitary and economic aid and would have a crucial effect in the coming war.

Meanwhile, King Hassan II, the Moroccan monarch (son of KingMohammed V, who had passed away in 1961) actively sought to pursue its claimand asked Spainto postpone holding the referendum; in January 1975, the Spanish governmentgranted the Moroccan request. In June1975, the Moroccan government pressed the UN to raise the Saharan issue to theInternational Court of Justice (ICJ), the UN’s primary judicial agency. On October 16, 1975, one day after the UNDecolonization Committee report was released, the ICJ issued its decision,which consisted of the following four important points (the court refers toSpanish Sahara as Western Sahara):

1. At the timeof Spanish colonization, “there were legal ties between this territory and the Kingdom of Morocco”;

2. At the timeof Spanish colonization, “there were legal ties between this territory and theMauritanian entity”;

3. Thereexisted “at the time of Spanish colonization … legal ties of allegiance betweenthe Sultan of Morocco and some of the tribes living in the territory of Western Sahara.They equally show the existence of rights, including some rights relating tothe land, which constituted legal ties between the Mauritanian entity… and theterritory of Western Sahara”;

4. The ICJconcluded that the evidences presented “do not establish any tie of territorialsovereignty between the territory of Western Sahara and the Kingdom of Moroccoor the Mauritanian entity. Thus, the Court has not found legal ties of such anature as might affect… the decolonization of Western Sahara and, in particular,… the principle of self-determination through the free and genuine expressionof the will of the peoples of the Territory”.

Far from clarifying the issue, the ICJ’s involvementradicalized the parties involved, as each side focused on that part of thecourt’s decision that vindicated its claims. Morocco and Mauritania cited “legal ties” as supporting their respectiveclaims, while the Polisario Front and Algeria pointed to “do not establish anytie of territorial sovereignty” and “the principle of self-determinationthrough the free and genuine expression of the will of the peoples of theTerritory” to put forward the Sahrawi peoples’ right of self- government. Spain’s chances of influencing thepost-colonial Saharan territory began to wane. On September 9, 1975, Spanish foreign minister Pedro Cortina y Mauri andPolisario Front leader El-Ouali Mustapha Sayed met in Algiers,Algeria to negotiate thetransfer of Saharan authority to the Polisario Front in exchange for economicconcessions to Spain,particularly in the phosphate and fishing resources in the region. Further meetings were held in Mahbes, Spanish Sahara on October 22. Ultimately, these negotiations did notprosper, as they became sidelined by the accelerating conflict and greaterpressures exerted by the other competing parties.

Shortly after the ICJ decision was released, King Hassan IIannounced that Morocco wouldhold the “Green March”, set for November 6, 1975, and called on Moroccans tomarch to and occupy Spanish Sahara. On that date, the Green March (the colorgreen symbolizing Islam) was carried out, with some 350,000 Moroccan civilians,protected by 20,000 soldiers, crossed the border from Tarfaya in southernMorocco and occupied some border regions in northern Spanish Sahara. Under instructions from the Spanish centralgovernment in Madrid,Spanish troops did not resist the incursion. On November 9, the marchers returned to Morocco, on orders of King HassanII who declared the action a success.

On October 31, 1975, six days before the Green March began,units of the Moroccan Army entered Farsia, Haousa and Jdiriya in northeastSaharan territory to deter Algerian intervention. Spainhad protested the Moroccan action to the UN in a futile attempt to have theinternational body stop the march; instead, the United Nations Security Council(UNSC) passed Resolution 380 that deplored the march and called on Moroccoto withdraw from the territory.

The timing of the escalating crisis could not have come at aworse time for Spain. In late October 1975, General FranciscoFranco, Spain’sdictator, was terminally ill and soon passed away on November 20, 1975. In the period before and after his death, Spainunderwent great political uncertainty, as the sudden void left by GeneralFranco, who had ruled for 40 years, threatened to ignite a political powerstruggle. The tenuous government, nowled by King Juan Carlos as head of state, was unwilling to face a potentiallyruinous war. World-wide colonialism wasat its twilight– just one year earlier, Portugal, one of the last colonialpowers, had agreed to end its long colonial wars against African nationalistmovements, eventually leading to the independences in 1975 of its Africanpossessions of Angola, Mozambique, Portuguese Guinea (since 1973), Cape Verde,and São Tomé and Príncipe.

By late October 1975, Spanish officials had begun to holdclandestine meetings in Madrid withrepresentatives from Moroccoand Mauritania. As a precaution for war, in early November1975, Spaincarried out a forced evacuation of Spanish nationals from the territory. On November 12, further negotiations wereheld in the Spanish capital, culminating two days later (November 14) in thesigning of the Madrid Accords, where Spain ceded the administration (but notsovereignty) of the territory, with Morocco acquiring the regions of El-Aaiún,Boujdour, and Smara, or the northern two-thirds of the region; while Mauritaniathe Dakhla (formerly Villa Cisneros) region, or the southern third; in exchangefor Spain acquiring 35% of profits from the territory’s phosphate miningindustry as well as off-shore fishing rights. Joint administration by the three parties through an interim government(led by the territory’s Spanish Governor-General) was undertaken in thetransitional period for full transfer to the new Moroccan and Mauritanianauthorities. (The Madrid Accords was not, and also since has not, beenrecognized by the UN, which officially continued to regard Spain as the “dejure”, if not “de facto”, administrative authority over the territory;furthermore, the UN deems the conflict region as occupied territory by Moroccoand, until 1979, also by Mauritania.)

On February 26, 1976, Spainfully withdrew from the territory, which henceforth became universally called Western Sahara (although the UN already had referred toit as such by 1975). As per theagreement, Moroccan forces occupied their designated region (which Morocco soon called its Southern Provinces; alsoin 1979, Morocco wouldinclude the southern zone after Mauritaniawithdrew); and Mauritanian troops occupied Titchla, La Guera, and later Dakhla(as the capital), of its newly designated Saharan province of Tirisal-Gharbiyya. Then on April 14, 1976,the two countries signed an agreement that formally divided the territory intotheir respective zones of occupation and control.

In the three-month period (November 1975–February 1976)during Spain’s withdrawaland replacement with Moroccan and Mauritanian administrations, tens ofthousands of Sahrawis fled to the Saharan desert, and subsequently into Tindouf, Algeria. On February 27, 1976, one day after Spain withdrew from the territory, the PolisarioFront declared the founding of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR),with a government-in-exile based in Algeria.

February 26, 2021

February 26, 1976 – Spain withdraws from Western Sahara

On February 26, 1976, Spainfully withdrew from Spanish Sahara, which henceforth became universally called Western Sahara (although the UN already had referred toit as such by 1975). As per theagreement, Moroccan forces occupied their designated region (which Morocco soon called its Southern Provinces; alsoin 1979, Morocco wouldinclude the southern zone after Mauritaniawithdrew); and Mauritanian troops occupied Titchla, La Guera, and later Dakhla(as the capital), of its newly designated Saharan province of Tirisal-Gharbiyya. Then on April 14, 1976,the two countries signed an agreement that formally divided the territory intotheir respective zones of occupation and control.

In the three-month period (November 1975–February 1976)during Spain’s withdrawaland replacement with Moroccan and Mauritanian administrations, tens ofthousands of Sahrawis fled to the Saharan desert, and subsequently into Tindouf, Algeria. On February 27, 1976, one day after Spain withdrew from the territory, the PolisarioFront declared the founding of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR),with a government-in-exile based in Algeria.

Map showing location of Western Sahara.

Map showing location of Western Sahara.(Taken from Western Sahara War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Background OnDecember 3, 1974, the UNGA passed Resolution 3292 declaring the UN’s interestin evaluating the political aspirations of Sahrawis in the Spanish territory. For this purpose, the UN formed the UNDecolonization Committee, which in May – June 1975, carried out a fact-findingmission in Spanish Sahara as well as in Morocco,Mauritania, and Algeria. In its final report to the UN on October 15,1978, the Committee found broad support for annexation among the generalpopulation in Morocco and Mauritania. In Spanish Sahara,however, the Sahrawi people overwhelmingly supported independence under theleadership of the Polisario Front, while Spain-backed PUNS did not enjoy suchsupport. In Algeria, the UN Committee foundstrong support for the Sahrawis’ right of self-determination.

Algeriapreviously had shown little interest in the Polisario Front and, in an ArabLeague summit held in October 1974, even backed the territorial ambitions of Morocco and Mauritania. But by summer of 1975, Algeria wasopenly defending the Polisario Front’s struggle for independence, a supportthat later would include military and economic aid and would have a crucialeffect in the coming war.

Meanwhile, King Hassan II, the Moroccan monarch (son of KingMohammed V, who had passed away in 1961) actively sought to pursue its claimand asked Spainto postpone holding the referendum; in January 1975, the Spanish governmentgranted the Moroccan request. In June1975, the Moroccan government pressed the UN to raise the Saharan issue to theInternational Court of Justice (ICJ), the UN’s primary judicial agency. On October 16, 1975, one day after the UNDecolonization Committee report was released, the ICJ issued its decision,which consisted of the following four important points (the court refers toSpanish Sahara as Western Sahara):

1. At the timeof Spanish colonization, “there were legal ties between this territory and the Kingdom of Morocco”;

2. At the timeof Spanish colonization, “there were legal ties between this territory and theMauritanian entity”;

3. Thereexisted “at the time of Spanish colonization … legal ties of allegiance betweenthe Sultan of Morocco and some of the tribes living in the territory of Western Sahara.They equally show the existence of rights, including some rights relating tothe land, which constituted legal ties between the Mauritanian entity… and theterritory of Western Sahara”;

4. The ICJconcluded that the evidences presented “do not establish any tie of territorialsovereignty between the territory of Western Sahara and the Kingdom of Moroccoor the Mauritanian entity. Thus, the Court has not found legal ties of such anature as might affect… the decolonization of Western Sahara and, inparticular, … the principle of self-determination through the free and genuineexpression of the will of the peoples of the Territory”.

Far from clarifying the issue, the ICJ’s involvementradicalized the parties involved, as each side focused on that part of thecourt’s decision that vindicated its claims. Morocco and Mauritania cited “legal ties” as supporting their respectiveclaims, while the Polisario Front and Algeria pointed to “do not establish anytie of territorial sovereignty” and “the principle of self-determinationthrough the free and genuine expression of the will of the peoples of theTerritory” to put forward the Sahrawi peoples’ right of self- government. Spain’s chances of influencing thepost-colonial Saharan territory began to wane. On September 9, 1975, Spanish foreign minister Pedro Cortina y Mauri andPolisario Front leader El-Ouali Mustapha Sayed met in Algiers,Algeria to negotiate thetransfer of Saharan authority to the Polisario Front in exchange for economicconcessions to Spain,particularly in the phosphate and fishing resources in the region. Further meetings were held in Mahbes, Spanish Sahara on October 22. Ultimately, these negotiations did notprosper, as they became sidelined by the accelerating conflict and greaterpressures exerted by the other competing parties.

Shortly after the ICJ decision was released, King Hassan IIannounced that Morocco wouldhold the “Green March”, set for November 6, 1975, and called on Moroccans tomarch to and occupy Spanish Sahara. On that date, the Green March (the colorgreen symbolizing Islam) was carried out, with some 350,000 Moroccan civilians,protected by 20,000 soldiers, crossed the border from Tarfaya in southernMorocco and occupied some border regions in northern Spanish Sahara. Under instructions from the Spanish centralgovernment in Madrid,Spanish troops did not resist the incursion. On November 9, the marchers returned to Morocco, on orders of King HassanII who declared the action a success.

On October 31, 1975, six days before the Green March began,units of the Moroccan Army entered Farsia, Haousa and Jdiriya in northeastSaharan territory to deter Algerian intervention. Spainhad protested the Moroccan action to the UN in a futile attempt to have theinternational body stop the march; instead, the United Nations Security Council(UNSC) passed Resolution 380 that deplored the march and called on Morocco towithdraw from the territory.

The timing of the escalating crisis could not have come at aworse time for Spain. In late October 1975, General FranciscoFranco, Spain’sdictator, was terminally ill and soon passed away on November 20, 1975. In the period before and after his death, Spain underwentgreat political uncertainty, as the sudden void left by General Franco, who hadruled for 40 years, threatened to ignite a political power struggle. The tenuous government, now led by King JuanCarlos as head of state, was unwilling to face a potentially ruinous war. World-wide colonialism was at its twilight–just one year earlier, Portugal, one of the last colonial powers, had agreed toend its long colonial wars against African nationalist movements, eventuallyleading to the independences in 1975 of its African possessions of Angola, Mozambique,Portuguese Guinea (since 1973), Cape Verde, and São Tomé and Príncipe.