Daniel Orr's Blog, page 70

February 24, 2021

February 24, 1968 – Vietnam War: U.S. forces recapture Hue

At Hue, in central Vietnam, the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong forces of the Tet Offensive, who had seized large sections of the city, were ordered to remain and defend their positions. A 28-day battle ensued, with U.S. forces, supported by naval and ground artillery and air support, advancing slowly and engaging the enemy in intense house-to-house battles. By late February 1968 when the last North Vietnamese/Viet Cong units had been driven out of Hue, some 80% of the city had been destroyed, 5,000 civilians killed, and over 100,000 people left homeless. Combat fatalities at the Battle of Hue were 700 American/South Vietnamese and 8,000 North Vietnamese/Viet Cong soldiers.

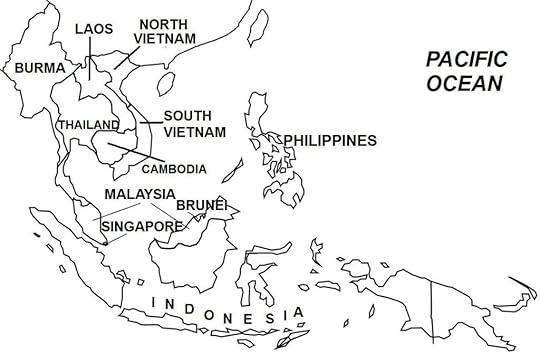

Map showing North Vietnam, South Vietnam, and other countries in Southeast Asia.

Map showing North Vietnam, South Vietnam, and other countries in Southeast Asia.(Taken from Vietnam War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

Tet Offensive Inearly 1967, North Vietnambegan preparing for a massive offensive into South Vietnam. This operation, which later came to be knownas the Tet Offensive, would have far-reaching consequences on the outcome ofthe war. The North Vietnamese plan tolaunch the Tet Offensive came about when political hardliners in Hanoi succeeded insidelining the moderates in government. As a result of the hardliners dictatinggovernment policies, in July 1967, hundreds of moderates, including governmentofficials and military officers, were purged from the Hanoi government and the Vietnamese CommunistParty.

By fall of 1967, North Vietnamese military planners had setthe date to launch the Tet Offensive on January 31, 1968. In the invasion plan, the Viet Cong was tocarry out the offensive, with North Vietnam only providing weapons and othermaterial support. The Tet Offensive,which was known in North Vietnamas “General Offensive, General Uprising”, called for the Viet Cong to launchsimultaneous attacks on many targets across South Vietnam, which would beaccompanied with calls to the civilian population to launch a generaluprising. North Vietnam believed that acivilian uprising in the south would succeed because of President Thieu’sunpopularity, as evidenced by the constant civil unrest and widespreadcriticism of government policies. Inthis scenario, once President Thieu was overthrown, an NLF-led communistgovernment would succeed in power, and pressure the United States to end its involvement in South Vietnam. Faced with the threat of internationalcondemnation, the United Stateswould be forced to acquiesce, and withdraw its forces from Vietnam.

As part of its general strategy for the Tet Offensive, North Vietnamincreased its military activity along the border region. In the last months of 1967, the NorthVietnamese military launched attacks across the border, including in Song Be,Loc Ninh, and Dak To in order to lure U.S. forces away from the mainurban areas. These diversionary attackssucceeded, as large numbers of U.S.troops were moved to the border areas.

In a series of clashes known as the “Border Battles”,American and South Vietnamese forces easily threw back these North Vietnameseattacks, inflicting heavy North Vietnamese casualties. However, U.S.military planners were baffled at North Vietnam’s intentions, asthese attacks appeared to be a waste of soldiers and resources in the face ofoverwhelming American firepower.

But the North Vietnamese had succeeded in drawing away thebulk of U.S.forces from the populated centers. Bythe start of the Tet Offensive, half of all U.S. combat troops were in I Corpsto confront what the Americans believed was an imminent major North Vietnameseinvasion into the northern provinces. U.S. militaryintelligence had detected the build ups of Viet Cong forces in the south andthe North Vietnamese in the north. Butthe U.S.high command, including General Westmoreland, did not believe that the VietCong had the capacity to mount a large offensive like that which actuallyoccurred in the Tet Offensive.

Following some attacks one day earlier (January 30), onJanuary 31, 1968 (which was the Vietnamese New Year or Tet, when a truce was traditionallyobserved), some 80,000 Viet Cong fighters, supported by some North VietnameseArmy units, launched coordinated attacks in Saigon, in 36 of the 44 provincialcapitals, and in over 100 other towns across South Vietnam. In Saigon,many public and military infrastructures were hit, including the governmentradio station where the Viet Cong/NLF tried but failed to broadcast apre-recorded message from Ho Chi Minh calling on the civilian population torise up in rebellion (electric power to the radio station was cut immediatelyafter the attack). A Viet Cong attemptto seize the U.S. Embassy in Saigon alsofailed.

Taken by surprise, South Vietnamese and American forcesquickly assembled a defense, and then soon counterattacked. Crucially, U.S.forces that had been sent to the Cambodian border returned to Saigonjust before the start of the Tet Offensive.

Viet Cong units occupied large sections of Saigon, but afterbitter street-by-street, house-to-house fighting, South Vietnamese and U.S. forces soongained the upper hand. South Vietnameseforces also mounted successful defenses in other parts of the country. In early February 1968, the Viet Congleadership ordered a general retreat. The rebels, now suffering heavy human and material losses, withdrew fromthe cities and towns.

At Hue,the ancestral capital, the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong attackers, who hadseized large sections of the city, were ordered to stay and defend theirpositions. A 28-day battle ensued, with U.S. forces,supported by naval and ground artillery and air support, advancing slowly andengaging the enemy in intense house-to-house battles. By late February 1968 when the last NorthVietnamese/Viet Cong units had been driven out of Hue, some 80% of the city hadbeen destroyed, 5,000 civilians killed, and over 100,000 people lefthomeless. Combat fatalities at theBattle of Hue were 700 American/South Vietnamese and 8,000 NorthVietnamese/Viet Cong soldiers.

While the Tet Offensive was ongoing, General Westmorelandcontinued to believe that the Tet Offensive was a diversion for a major NorthVietnamese attack in the north, particularly on the Khe Sanh American combatbase, in preparation for a full invasion of South Vietnam’s northern provinces. Thus, he sent back only few combat troops already committed to defendthe towns and cities. After the war,North Vietnamese officials have since insisted that the Tet Offensive was theirmain objective, and that their attack on Khe Sanh was merely a diversion todraw away U.S.forces from the Tet Offensive. Somehistorians also postulate that North Vietnam planned no diversion at all, butthat its purpose was to launch both the Khe Sanh and Tet offensives.

Based on the second scenario, North Vietnam planned the siege at Khe Sanh as a repetition ofits successful 1954 siege of the French base at Dien Bien Phu. A North Vietnamesevictory at Khe Sanh would have the Americans meet the same fate as the Frenchat Dien Bien Phu. Conversely, the U.S. military wanted Khe Sanh to bea major showdown with the North Vietnamese Army, where overwhelming Americanfirepower would be brought to bear in battle and inflict serious losses on theenemy.

The siege on Khe Sanh began on January 21, 1968 (ten daysbefore the Tet Offensive), when 20,000 North Vietnamese troops, after manymonths of logistical buildup and moving heavy artillery into the heightssurrounding Khe Sanh, began a barrage of artillery, mortar, and rocket fireinto the Khe Sanh combat base, which was defended by 6,000 U.S. Marines and someelite South Vietnamese troops. Another20,000 North Vietnamese troops served as reinforcements and also cut off roadaccess to Khe Sanh, sealing off, and thus surrounding, the base. The 77-day battle featured 1. artillery duelsby both sides; 2. Khe Sanh being supplied solely by air; 3. North Vietnameseprobing attacks on the Khe Sanh base; and 4. North Vietnamese assaults todislodge U.S. Marines outposts situated on a number of nearby strategic hills.

In early April 1968, the Siege of Khe Sanh ended, with U.S. airfirepower being the decisive factor. Bythen, American B-52 bombers had dropped some 100,000 tons of bombs (equivalentto five Hiroshima-size atomic bombs), which wreaked havoc on North Vietnamesepositions. U.S.bombing also destroyed the extensive network of trenches which the NorthVietnamese were building to inch ever closer to U.S. positions. The North Vietnamese planned to use thetrenches as a springboard for their final assault on Khe Sanh. (The Viet Minh had used this tactic to overrunthe Dien Bien Phu base in 1954.) NorthVietnamese forces retreated to Laosand North Vietnam. Combat fatalities during the siege of KheSanh included 270 Americans, 200 South Vietnamese, and 10,000 North Vietnamesesoldiers.

February 23, 2021

February 23, 1994 – Bosnian War: Bosniaks and Bosnian Croats form a unified government

In early 1994, with another Bosnian Serb general offensivelooming, Bosniaks and Bosnian Croats found common ground. With the urging of the United States, on February 23, 1994, Bosniaksand Bosnian Croats formed a unified government under the “Federation of Bosniaand Herzegovina”. The Bosnian War shifted to fighting betweenthe combined Bosniak-Bosnian Croat forces against the Bosnian Serb Army.

In early 1994, Bosnian Serb forces laid siege to Sarajevo, Bosnia’scapital, relentlessly pounding the city with heavy artillery and inflictingheavy civilian casualties. The siege ofthe capital drew international condemnation, with the United Nations (UN) andthe North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) becoming increasingly involved inthe war. NATO declaredBosnia-Herzegovina a no-fly zone. OnFebruary 28, 1994, NATO warplanes downed four Serbian aircraft over Banja Luka.

Under a UN threat of a NATO airstrike, Bosnian Serbs wereforced to lift the siege on Maglaj; supply convoys thus were able to reach thecity by land, the first time in nearly ten months. In April 1994, NATO warplanes attackedBosnian Serb forces that were threatening a UN-protected area in Gorazde. Later that month, a Danish contingent of theUN forces engaged Bosnian Serb Army units in the village of Kalesija. The NATO air strikes, which greatlycontributed to ending the war, were conducted in coordination with the UNhumanitarian and peacekeeping forces in Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Yugoslavia comprised six republics, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Serbia, Macedonia, and Macedonia, and two autonomous provinces, Kosovo and Vojvodina.

Yugoslavia comprised six republics, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Serbia, Macedonia, and Macedonia, and two autonomous provinces, Kosovo and Vojvodina.(Taken from Bosnian War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 1)

Bosnia-Herzegovina has three main ethnic groups: Bosniaks(Bosnian Muslims), comprising 44% of the population, Bosnian Serbs, with 32%,and Bosnian Croats, with 17%. Slovenia and Croatia declared theirindependences in June 1991. On October15, 1991, the Bosnian parliament declared the independence ofBosnia-Herzegovina, with Bosnian Serb delegates boycotting the session inprotest. Then acting on a request fromboth the Bosnian parliament and the Bosnian Serb leadership, a EuropeanEconomic Community arbitration commission gave its opinion, on January 11,1992, that Bosnia-Herzegovina’s independence cannot be recognized, since noreferendum on independence had taken place.

Bosnian Serbs formed a majority in Bosnia’snorthern regions. On January 5, 1992,Bosnian Serbs seceded from Bosnia-Herzegovina and established their owncountry. Bosnian Croats, who also compriseda sizable minority, had earlier (on November 18, 1991) seceded fromBosnia-Herzegovina by declaring their own independence. Bosnia-Herzegovina, therefore, fragmentedinto three republics, formed along ethnic lines.

Furthermore, in March 1991, Serbia and Croatia, two Yugoslavconstituent republics located on either side of Bosnia-Herzegovina, secretlyagreed to annex portions of Bosnia-Herzegovina that contained a majoritypopulation of ethnic Serbians and ethnic Croatians. This agreement, later re-affirmed by Serbiansand Croatians in a second meeting in May 1992, was intended to avoid armedconflict between them. By this time,heightened tensions among the three ethnic groups were leading to openhostilities.

Mediators from Britainand Portugalmade a final attempt to avert war, eventually succeeding in convincingBosniaks, Bosnian Serbs, and Bosnian Croats to agree to share political powerin a decentralized government. Just tendays later, however, the Bosnian government reversed its decision and rejectedthe agreement after taking issue with some of its provisions.

February 22, 2021

February 22, 1999 – Ethiopian-Eritrean War: Ethiopia launches a major offensive into Eritrea

On February 22, 1999, the Ethiopian Army, supported by air,armored, and artillery units, launched a major offensive in the easternfront. Five days later, the Ethiopianshad broken through and captured the Badme area, and had advanced 10 kilometersinto Eritrea. The Eritrean government then announced thatit was ready to accept the OAU peace plan, but Ethiopia, which earlier had alsoagreed to the proposal, now demanded that Eritrea withdraw all its forces fromEthiopian territory before the plan could be implemented.

Ethiopia, Eritrean, and nearby countries.

Ethiopia, Eritrean, and nearby countries.(Taken from Ethiopian-Eritrean War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Background In themidst of Eritrea’sindependence war, in 1974, Emperor Haile Selassie was deposed in a militarycoup and a council of army officers called “Derg” came to power. The Derg regime experienced great politicalupheavals initially arising from internal power struggles, as well as theEritrean insurgency and other ethnic-based armed rebellions; in 1977-78, theDerg also was involved in a war with neighboring Somalia (the Ogaden War, separatearticle).

By the early 1990s, the Ethiopian People’s RevolutionaryDemocratic Front (EPRDF), a coalition of Ethiopian rebel groups, had formed amilitary alliance with the EPLF and separately accelerated their insurgenciesagainst the Derg regime. In May 1991, theEPRDF toppled the Derg regime, while the EPLF seized control of Eritrea bydefeating and expelling Ethiopian government forces. Both the EPRDF and EPLF then gained power in Ethiopia and Eritrea, respectively, with theserebel movements transitioning into political parties. Under a UN-facilitated process and with theEthiopian government’s approval, Eritreaofficially seceded from Ethiopiaand, following a referendum where nearly 100% of Eritreans voted forindependence, achieved statehood as a fully sovereign state.

Because of their war-time military alliance, the governmentsof Ethiopia and Eritrea maintained a close relationship and signed an Agreementof Friendship of Cooperation that envisioned a comprehensive package ofmutually beneficial political, economic, and social joint endeavors; subsequenttreaties were made in the hope of integrating the two countries in a broadrange of other fields.

Both states nominally were democracies but with strongauthoritarian leaders, Prime Minister Meles Zenawi in Ethiopia and President Isaias Afwerki in Eritrea. Stateand political structures differed, however, with Ethiopiaestablishing an ethnic-based multi-party federal parliamentary system and Eritrea settingup a staunchly nationalistic, one-party unitary system. Eritreaalso maintained a strong militaristic culture, acquired from its longindependence struggle, for which in the years after gaining independence, itcame into conflict with its neighbors, i.e. Yemen,Djibouti, and Sudan.

Ethiopian-Eritrean relations soon also deteriorated as a resultof political differences, as well as the personal rivalry between the twocountries’ leaders. Furthermore, duringtheir revolutionary struggles, the Eritrean and Ethiopian rebel groupssometimes came into direct conflict over projecting power and controllingterritory, which was overcome only by their mutual need to defeat a commonenemy. In the post-war period, thisacrimonious historical past now took on greater significance. Relations turned for the worse when inNovember 1997, Eritreaintroduced its own currency, the “nakfa” (which replaced the Ethiopian birr),in order to steer its own independent local and foreign economic and tradepolicies. During the post-war period,trade between Ethiopia and Eritrea was significant, and Eritrea gave special privileges to the nowlandlocked Ethiopia to usethe port of Assab for Ethiopian maritime trade. But with Eritreaintroducing its own currency, Ethiopiabanned the use of the nakfa in all but the smallest transactions, causing tradebetween the two states to plummet. Trucks carrying goods soon were backed up at the border crossings andthe two sides now saw the need to delineate the as yet unmarked border tocontrol cross-border trade.

Meanwhile, disputes in the frontier region in and around thetown of Badmehad experienced a steady increase. Asearly as 1992, Eritrean regional officials complained that Ethiopian armedbands descended on Eritrean villages, and expelled Eritrean residents anddestroyed their homes. In July 1994,regional Ethiopian and Eritrean representatives met to discuss the matter, butharassments, expulsions, and arrests of Eritreans continued to be reported in1994-1996. Then in April 1994, theEritrean government became aware that Ethiopia had carried out a numberof demarcations along the Badme area, prompting an exchange of letters by PrimeMinister Zenawi and President Afwerki. In November 1994, a joint panel was set up by the two sides to try andresolve the matter; however, this effort made no substantial progress. In the midst of the Badme affair, anothercrisis broke out in July-August 1997 where Ethiopian troops entered anotherundemarcated frontier area in pursuit of the insurgent group ARDUF (AfarRevolutionary Democratic Unity Front or Afar Revolutionary Democratic UnionFront); then when Ethiopia set up a local administration in the area, Eritreaprotested, leading to firefights between Ethiopian and Eritrean forces.

Another source of friction between the two countries wasgenerated when, starting in 1993, the regional administration in TigrayProvince (in northern Ethiopia) published “administrative and fiscal” maps ofTigray that included the Badme area and a number of Eritrean villages that laybeyond the 1902 colonial-era and de facto “border” line. Since the 1950s, Tigray had administered thisarea and had established settlements there. In turn, Eritreadeclared that the area had been encroached as it formed part of the EritreanGash-Barka region.

Badme, a 160-square mile area that became the trigger forthe coming war, was located in the wider Badme plains, the latter forming asection of the vast semi-desert lowlands adjoining the Ethiopian mountains andstretching west to the Sudan. During the early 20th century when theEthiopian-Italian border treaties were made, Badme was virtually uninhabited,save for the local endemic Kunama tribal people. The 1902 treaty, which became the de factoborder between the Ethiopian Empire and Italian Eritrea in the western andcentral regions, stipulated that the border, heading from west to east, ranstarting from Khor Um Hagger in the Sudanese border, followed the Tekezze(Setit) River to its confluence with the Maieteb River, at which point it ran astraight line north to where the Mareb River converges with the Ambessa River(Figure 32). Thereafter, the borderfollowed a general eastward direction along the Mareb, through the smaller Melessa River,and finally along the Muna River. In turn, the 1908 treaty specified that theborder along the eastern regions would follow the outlines of the Red Sea coastline from a distance of 60 kilometersinland. These treaties have since beenupheld by successive Ethiopian governments, whose maps have followed thetreaties’ delineations to form a border that is otherwise unmarked on theground.

February 21, 2021

February 21, 1972 – U.S. President Nixon visits the People’s Republic of China

In August-October 1969, for China’sleader Mao Zedong, the potential threat of war with the Soviet Union produced amajor shift in his view regarding China’ssecurity: that the Soviet Union, not the United States, posed the immediate danger to China. Furthermore, until then, Mao believed thatthe United States and theSoviet Union were working together to destroy China. Mao soon heeded his military’s counsel thatpolitical, ideological, and military competition between the Americans andSoviets prevented them from aligning their forces against China.

By 1969, Mao’s hard-line Marxist views had changeddramatically, this shift also being influenced by the negative effects of China’s longperiod of diplomatic isolation from the international community. Mao became convinced that China’s security was best served with analliance of convenience with the United States, which he saw as thelesser danger. Mao remarked that it wasbetter “to ally with the enemy far away … in order to fight the enemy who is atthe gate”. Furthermore, in 1968, the United Statesdecision to withdraw its forces from the Vietnam War was received positively bythe Chinese government.

In the midst of the Sino-Soviet split, the United States also wanted to establish diplomatic ties with China, in order to play the two communist giants against each other. The United States would thereby weaken communism generally, and also undermine the ambitions of its rival, the Soviet Union. Then in 1969, the government of newly elected U.S. President Richard Nixon secretly prepared to foster rapprochement with China. During the course of the year, the United States issued a number of diplomatic feelers, e.g. that the U.S. government would lift trade and travel restrictions to China; that the United States encouraged communication with China; and that China emerging from isolation would benefit Asia and the world community.

The breakthrough came from an unlikely source: at aninternational table tennis competition in Japanin April 1971, American and Chinese athletes developed a bond of friendship,which led to the U.S. tabletennis players visiting China(the first Americans to do so under communist rule) that same month, on theinvitation of the Chinese government. This series of events, called the “ping-pong diplomacy”, paved the wayfor opening secret diplomatic-level communications between the two countries, leadingto Henry Kissinger, U.S. National Security Adviser, making two trips (the firstbeing secret) to China in 1971, where he met with Premier Zhou Enlai. In these meetings, Kissinger gave thefollowing assurances: that the United States would work for China’s entry tothe United Nations (China was admitted to the UN in October 1971, replacing theRepublic of China (Taiwan), which was expelled); that the United States wouldprovide China with American-Soviet dealings; and that U.S. forces graduallywould be withdrawn from the Vietnam War.

Kissinger’s trips set the stage for President Nixon’smonumental visit to Chinain February 1972, which together with the announcement of the trip in July1971, set shock waves around the world. Closer United States-China relations soon developed, particularly afterMao’s death in September 1976 and the emergence of reformist Deng Xiaoping asthe top Chinese leader. Full diplomaticrelations between the two countries were established in January 1979. Earlier in 1973, the United States assured Mao of direct Americansupport if the Soviet Union attacked China.

(Taken from Sino-Soviet Border Conflict – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

The United States-China rapprochement caused great concernfor the Soviet Union. Then on the invitation of Soviet leaderLeonid Brezhnev, President Nixon visited Moscow in May 1972 (three months aftervisiting China), where the two sides signed a number of nuclear weapons controlagreements, leading to a period of improved relations between the twocountries.

Aftermath The threat of a Soviet-Chinese general war abatedfollowing the informal meeting between Premiers Kosygin and Zhou in September1969. However, tensions remained high inthe immediate aftermath, and through the 1970s and much of the 1980s. Even in 1990, when the two countries hadmoved forward toward achieving a political and territorial resolution, theirshared border continued to be heavily militarized: the Soviets had 700,000troops, or ¼ of its ground forces, as well as ⅓ of its air force, and ⅓ of itsnavy, while the Chinese had 1 million troops.

Furthermore, talks to achieve a definitive border treatyfailed to make progress. Both China and the Soviet Union shared the credit in North Vietnam’s victory over South Vietnam in April 1975, but the reunified Vietnam sooncame under the Soviet sphere of influence, straining Sino-Vietnamese relations. Then in February-March 1979, during the briefwar between Vietnam and China(Sino-Vietnamese War, separate article), tensions spiked along theChinese-Soviet border. The Soviet Union,apart from raising diplomatic protests, did not intervene militarily for Vietnam, despite a 1978 military agreementbetween Vietnam and the Soviet Union.

In December 1979, the Soviet Union launched an invasion of Afghanistan, and subsequently occupied thecountry for nearly a decade (until February 1989), which further exacerbatedSoviet-Chinese relations, as Chinaaccused the Soviets of planning to encircle China. The Soviet-Chinese ideological clash alsoextended to various conflicts in Africa, e.g.Rhodesian Bush War, Angolan Civil War, Ogaden War, etc.

By the early 1980s, China had effectively abandonedMarxism-Leninism and the communist tenets of class warfare and worldrevolution, and had adopted a mixed, semi-capitalist economy. China’s relations with the Westalso improved. And with these reformsde-emphasizing communism as paramount in China’s foreign policy,Chinese-Soviet tensions eased. In 1982,with Brezhnev calling for improved ties and the Chinese government respondingfavorably, vice-ministerial levels and trade relations were restored between thetwo countries.

In 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev, the new Soviet leader, startedto implement major political, social, and economic reforms in the Soviet Union,which soon led to profound and dramatic national, regional and internationalpolitical and security consequences. By1989, Eastern Bloc countries had discarded socialism and state-controlledeconomies, and were adopting Western-style democracy and free marketeconomies. By the end of 1991, theSoviet Union disintegrated, and its Cold War rivalry with the United Statesended.

Gorbachev also initiated reconciliation with China, whichthe latter received favorably. Relationsbetween the two countries improved considerably, particularly after the SovietUnion removed what the Chinese government called the “three obstacles” toChinese-Soviet relations: Soviet forces were withdrawn from Afghanistan; the Soviet Union ended its supportfor Vietnam’s occupation of Cambodia; and the Soviet Union and China signed anagreement which reduced their forces at the border.

At the same time, border talks between the two countriesaccelerated toward the end of the 1980s and into the early 1990s. China promised to honor the 19thcentury treaties, and negotiations focused only on the currently disputed areascomprising some 35,000 square kilometers.

In May 1991, Chinaand the Soviet Union signed a final borderagreement, which delineated much of the frontier along the eastern region. The border agreement gave China a netterritorial gain of 720 square kilometers. The thalweg principle, or the median line of a water channel, was usedto set the border line. As a result, inthe Argun River where 413 disputed islands were located, China gained 209 islands, while Russia retained204. In the Amur River where 1,680disputed islands were located, Chinagained 902 islands while Russiaretained 708. In the Ussuri Riverwhere 320 disputed islands were located, Chinagained 153 islands while Russiaretained 167. Border lines also were setalong Lake Khanka and the Granitnaya and Tumenrivers. In October 2003, a supplementaryborder agreement was signed, which resolved ownership of three other islands(which were not covered in the 1991 agreement). Of these islands, Damansky/Zhenbao Island, the site of the 1969 clashes,was awarded to China.

Following the Soviet Union’s dissolution in 1991, threeformer Soviet states in Central Asia, Kazakhstan Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan, became independent countries, andalso inherited from Russiathe disputed western border with China. Negotiations were held to resolve theissue. In 1994, in the Kazakhstan-Chinaborder agreement, of the 944 square kilometers of disputed territory, China gained 406 square kilometers (43%), while Kazakhstanretained 538 square kilometers (57%). InTajikistan, where much ofthe former Soviet-Chinese disputed border was located, a border agreement with China was signed in 2002; 1,000 squarekilometers of territory in the Pamir mountain region was transferred to China, while 28,000 square kilometers wereretained by Tajikistan. In 2004, in the China- Kyrgyzstan bordertreaty, Chinagained 900 square kilometers in the Uzengi-Kuush mountain area, or some 32% ofthe disputed area.

February 20, 2021

February 20, 1964 – Sand War: The Organization of African Union (OAU) mediates a ceasefire between Algeria and Morocco

On February 20, 1964, the Organization of African Union (OAU) negotiated a ceasefire between Algeria and Morocco, ending fighting in the Sand War. A demilitarized zone (DMZ) was established to separate the opposing forces, which withdrew to pre-war positions. A peacekeeping force from Ethiopia and Mali was deployed at the DMZ to enforce the ceasefire.

The Sand War was fought between Algeria and Morocco.

The Sand War was fought between Algeria and Morocco.(Taken from Sand War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

As early as July 1962 when Algeriahad just gained its independence, Moroccan forces infiltrated into AlgerianColomb-Bechar, declaring it as part of Moroccan territory before withdrawingback to Morocco. Then by the second half of 1963, the Moroccangovernment began carrying out propaganda attacks against Algeria,accusing it of committing acts of aggression, airspace and territorialviolations, and expelling Moroccan nationals. Algeriaresponded with a propaganda blitz of its own directed against King Hassan II,accusing the monarch of inciting war, repressing his own people, and denyingAlgerians their hard-won freedom.

In early October 1963, Moroccan auxiliary troops crossed the“border” from Tagounit and seized Hassi-Beida and Tinjoub, two towns thatformed part of the disputed Sahara region andwas situated strategically along the road between Colomb-Bechar andTindouf. On October 8, an Algeriancounter-attack recaptured the two towns. Six days later, October 14, Moroccan forces, this time from the regulararmy, attacked again, expelling the Algerian troops and wresting back controlof the towns. The Algerians responded bycapturing Ich, a small Moroccan border town which had little strategic valuebut was purposed by the Algerians to be used as a bargaining point in post-warnegotiations. Fighting also broke out inother places, notably in Tindouf and Figuig. Combat action was characterized with the Moroccan Army deployed inregular military formations and using conventional methods and combatequipment, including heavy weapons, while Algerian forces were organized intosmall guerilla units (carried over from the independence war) using asymmetric,hit-and-run warfare with mostly light weapons. The well-armed and better trained Moroccans gained the upper hand incombat but Egypt’s militaryassistance to Algeriaallowed the war to settle into a stalemate by early November 1963.

The Algerian government appealed to the Organization ofAfrican Union (OAU) for mediation, particularly invoking the 1964 OAU guidelinewhich stipulated that member countries must respect colonial-era borders (whichwas intended to prevent conflicts between modern-day states). In turn, Moroccoappealed to the United Nations (UN), invoking UN General Assembly Resolution1514 which, among other things, states that the process of decolonization mustnot infringe on an existing state’s territorial integrity, which in the case ofhistorical lands claimed by Morocco,were violated during the French colonial period.

Moroccohad achieved a strategic victory but acquiesced under strong internationalpressure and withdrew from its captured territories. Under OAU mediation and with peacekeepersfrom Ethiopia and Mali deployedalong the “border”, a ceasefire was implemented and a demilitarized zoneestablished after the belligerents withdrew to pre-war positions. In February 1964, a formal ceasefire cameinto effect.

Aftermath The twosides re-established diplomatic relations following an Arab League-sponsoredsummit held in Cairo, Egypt in January 1964. In border talks that took place also in 1964,both sides agreed that the disputed areas would remain with Algeria (in effect, affirming Algeria’s succession to the colonial-eraborders) in exchange for Moroccoand Algeriasharing the wealth of a jointly established iron-ore industry in the Tindoufregion. In 1969, a treaty of solidarityand cooperation signed at Ifane led to improved relations, which in turn led toan agreement signed in Tlemcen, Algeria in 1970that was aimed at establishing a definitive border. In 1972, the Algeria-Morocco border agreementwas released, but which was ratified by Morocco only in May 1989.

In 1976, tensions flared again (that almost led to war)between the two countries over Western Sahara, a recently decolonized Spanishpossession located south of Moroccoand west of Algeria(see Western Sahara War, separate article).

February 19, 2021

February 19, 1943 – World War II: Start of the Battle of Kasserine Pass

On February 19, 1943, Axis and Allied forces began the five-day Battle of Kasserine Pass in Tunisia. German Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, leading the Axis forces comprising German Afrika Korps and Italian units, intended to punch a hole in the Allied lines through the Kasserine Pass, a gap in the Grand Dorsal chain of the Atlas Mountains in west central Tunisia. On February 20, his forces broke through, throwing back the inexperienced American forces a distance of 80 km west of Faid Pass, inflicting heavy casualties and destroying or capturing substantial Allied equipment.

American forces soon rallied, and with reinforcing Britishunits, managed to break the Axis attack and hold the exits on the mountainpasses in western Tunisia.

Territories involved in the battles for North Africa and the Horn of Africa.

Territories involved in the battles for North Africa and the Horn of Africa.(Taken from Italian Campaign – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

In East Africa, the Italian Army achieved success initially,launching offensives from Italian territories of Ethiopia, Eritrea, and ItalianSomaliland and driving away the British from British Somaliland, and seizingsome border regions in British-controlled Sudan and Kenya (Figure 34). At this stage of World War II, Britain’soverseas possessions were extremely vulnerable, as British efforts werediverted to the homeland to confront the ongoing German air offensives (Battleof Britain, separate article). But withthe Luftwaffe scaling down operations in Britainas 1941 progressed, the British soon counter-attacked in East Africa, throwingback the Italians and regaining lost territory, and then capturing Ethiopia, Eritrea,and Italian Somaliland, and forcing the surrender of the remaining Italianforces in East Africa.

In North Africa, which was a major battleground in World WarII, the Italian Army also achieved some success initially, launching from Libya and advancing 62 miles (100 km) intoBritish-administered Egyptin September 1940, while taking advantage of the desperate situation of theBritish in the ongoing Battle of Britain. In December 1940, the British counter-attacked and threw back the muchlarger Italian forces into Libya,taking some 130,000 Italian prisoners and advancing 500 miles (800 km) to ElAgheila. Now poised to expel the ItalianArmy from North Africa altogether, the British were forced to halt theiroffensive to transfer some of their troops to Greece, to help contain a newItalian offensive there.

The pause allowed Hitler to come to the aid of hisbeleaguered ally Mussolini, in February 1941, sending the first units of theGerman Afrika Korps led by General Erwin Rommel, to fight alongside the Italianforces, which also were bolstered by reinforcements arriving from Europe. A see-sawbattle ensued for over a year, with one side pushing the other hundreds ofmiles through the desert, and then the other side launching a counter-offensivethat threw back the other and penetrating deep into enemy territory.

Then in October-November 1942, the British 8th Armydecisively defeated the German-Italian force at the Second Battle of ElAlamein, forcing the Axis to retreat 1,600 miles (2,600 km) to theLibya-Tunisia border.

Also in November 1942, an American-British force landed at Morocco and Algeria,which were administered by Vichy France. After a short period of fighting, theAmericans and British succeeded in persuading French forces there to switchsides to the Allies. American-British-French forces from the west and the British 8th Armyfrom the east then attacked and encircled the German-Italian forces in Tunisia, and in May 1943, expelled the Axis fromNorth Africa. As a result, Italylost all its African territories.

February 18, 2021

February 18, 1932 – Japan sets up Manchukuo, a puppet state in northern China

To provide legitimacy to its conquest and occupation ofManchuria, on February 18, 1932, Japanestablished Manchukuo (“State of Manchuria”), purportedly an independent state, with itscapital at Hsinking (Changchun). Puyi, the last and former emperor of China under the Qing dynasty, was named Manchukuo’s “head ofstate”. In March 1934, he was named“Emperor” when Manchukuowas declared a constitutional monarchy.

Manchukuo was viewed bymuch of the international community as a puppet state of Japan, andreceived little foreign recognition. Infact, Manchukuo’s government was controlled byJapanese military authorities, with Puyi being no more than a figurehead andthe national Cabinet providing the front for Japanese interests in Manchuria.

Japan controlled the South Manchuria Railway from Ryojun (formerly Port Arthur) to Mukden and further north by the time of its invasion of Manchuria in 1931.

Japan controlled the South Manchuria Railway from Ryojun (formerly Port Arthur) to Mukden and further north by the time of its invasion of Manchuria in 1931.(Taken from Japanese Invasion of Manchuria – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

Background Toprotect Japanese personnel and their interests, including the territory andrailway, the Japanese military formed the Kwantung Army in 1906, which soonbecame dominated by radical officers who desired that Japan took a more aggressiveforeign policy. Japanese troopsprotecting the railway were confined to a prescribed zone on both sides of thetracks, and by agreement were not allowed to operate beyond this perimeter.

In the late 1920s, the Kwantung Army drew up a plan to annexthe whole of Manchuria for Japan,but this was contingent only if Chinaprovoked a war that could justify such an invasion. The deteriorating China-Japan relations wereexacerbated by the intensely anti-foreign, particularly anti-Japanese, policiesof Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist government. Japan, having gained territories and concessions in Northeast Chinathrough treaties, complained of many violations being committed by the Chinese,including infringing on Japanese rights and interests, interfering withJapanese businesses, boycotting Japanese goods, evicting and detaining Japaneseindividuals and confiscating their properties, and cases of violence, assault,and battery.

In 1928, Chinaended over a decade of political fragmentation and achieved reunification underNationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek and his Kuomintang (KMT) government(previous article). Japan had opposed China’sreunification, viewing this as a threat to its ambitions in Manchuria. Elements of the Kwantung Army assassinatedthe leading Manchurian warlord, Zhang Zuolin, who had maintained a fragile butworkable relationship with the Japanese. Zhang Xueliang, Zhang Zuolin’s son, succeeded as the leading Manchurianwarlord, whom the Japanese hoped to win over. Instead, the young warlord recognized Chiang’s authority over Manchuria,and asked for financial assistance from the Nationalist government to constructrailway and port facilities in Manchuria. The Nationalist government soon establishedcivilian authority in Manchuria, setting uplocal administrative offices in the cities and towns. In April 1931, the Chinese governmentannounced its intention to reclaim foreign-held concessions, properties, andinfrastructures. Chiang, afterreunifying China,had long sought to renegotiate with the foreign powers for the end of theQing-era “unequal treaties”.

The Japanese naturally were alarmed, as the proposedprojects by Chinathreatened to compete directly with the existing Japan-controlled rail and portfacilities. Back at home, Japanexperienced rapid population growth pressures, a massive earthquake in 1923that killed over 100,000 people, and economic difficulties in the Showa crisis(1927) and then the ongoing worldwide Great Depression. Japan’s political system also washighly unstable, as successive governments owed their existence to and werecontrolled by the Japanese military establishment.

In mid-1931, two incidents further aggravated relationsbetween Japan and China. First, in late June, a Japanese Army officer,Captain Shintarō Nakamura, and his crew, conducting intelligence work in aremote area in Manchuria, were captured andexecuted by troops loyal to warlord Zhang Xueliang. A few days later, on July 1, 1931, when localChinese farmers in Wanpaoshan village, Manchuria,attacked newly settled ethnic Korean farmers over a dispute on irrigationrights, Japanese police intervened and protected the Koreans. The second incident triggered widespreadanti-Chinese riots in Korea,which was then a Japanese possession. The two incidents, particularly the Nakamura murder, also fueledJapanese public anger against China,and the Japanese military pressed its government to undertake stronger punitiveactions against China.

Two years earlier, in 1929, a number of Japanese officers ofthe Kwantung Army, particularly Colonel Seishirō Itagaki and Lieutenant ColonelKanji Ishiwara among others, had began preparing a contingency plan for aJapanese full-scale conquest of Manchuria. Taking advantage of Japanese public anger brought about by the tworecent incidents, Colonel Ishiwara traveled to Tokyo and presented the now completedcontingency invasion plan to the Japanese Military High Command, which thelatter approved. In Ryojun (Port Arthur), KwantungArmy commander Shigeru Honjo also agreed to carry out the contingency plan,subject to the Chinese military precipitating a major incident that couldjustify a Japanese invasion.

However, the Japanese government, which maintained aconciliatory policy on its relations with China, issued instructions to theKwantung Army’s investigation of the Nakamura incident, to proceed morediplomatically, which was a setback to officers who wanted to provoke a confrontationthat would lead to war. Then when theJapanese military high command in Tokyo sent ahigh-ranking officer to Manchuria to providecounsel on the Nakamura murder negotiations with the Chinese, the plottersdecided to take action.

February 17, 2021

February 17, 1979 –Sino-Vietnamese War: China begins invasion of Vietnam

By February 1979, 30 divisions of the People’s LiberationArmy (PLA, China’sarmed forces) were massed along the border. On February 15, 1979, Chinaannounced its plan to attack Vietnam. Also on that day, China’s1950 “Treaty of Friendship, Alliance, and MutualAssistance” with the Soviet Union ended, thus freeing China from its obligation to pursuenon-aggression against a Soviet ally. Because of the threat of Soviet intervention from the north, on February16, Chinese authorities declared that it was also prepared to go to war with theSoviet Union. By this time, the bulk of Chinese forces (some 1.5 million troops) wereconcentrated along the northern border, while 300,000 Chinese civilians inthese border regions were evacuated.

On February 17, 1979, some 200,000 PLA troops, supported byarmor and artillery, attacked along two fronts across the 1,300-kilometerChina-Vietnam border. China officially announced that its offensivewas a “self-defense counterattack” to “teach Hanoi a lesson”. The Sino-Vietnamese War hadbegun.

(Taken from Sino-Vietnamese War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

Background Inlate December 1978, Vietnaminvaded Cambodia,and within two weeks, its forces toppled the Khmer Rouge government, and set upa new Cambodian government that was allied with itself (previous article). The Khmer Rouge had been an ally of China,and as a result, Chinese-Vietnamese relations deteriorated. In fact, relations between China and Vietnam had been declining in theyears prior to the invasion.

During the Vietnam War (separate article), North Vietnam received vital military andeconomic support from China,and also from the Soviet Union. But as Chinese-Soviet relations had beendeclining since the early 1960s (with both countries nearly going to war in1969), North Vietnam was forced to maintain a delicate balance in its relationsbetween its two patrons in order to continue receiving badly needed weapons andfunds. But after the communist victoryin April 1975, the reunified Vietnamhad a gradual falling out with Chinaover two issues: the persecution of ethnic Chinese in Vietnam, and a disputed border.

Following the Vietnam War, the Vietnamese central governmentin Hanoi launched a campaign to break down thefree-market economic system in the former South Vietnam to bring it in linewith the country’s centrally planned socialist economy. Ethnic Chinese in Vietnam (called Hoa), whocontrolled the South’s economy, were subject to severe economic measures. Many Hoa were forced to close down theirbusinesses, and their assets and properties were seized by the government. Vietnamese citizenship to the Hoa was alsovoided. The government also forced tensof thousands of Hoa into so-called “New Economic Zones”, which were located inremote mountainous regions. There, theyworked as peasant farmers under harsh conditions. The Hoa also were suspected by the governmentof plotting or carrying out subversive activities in the North.

As a result of these repressions, hundreds of thousands ofHoa (as well as other persecuted ethnic minority groups) fled the country. The Hoa who lived in the North crossedoverland into China, whilethose in the South went on perilous journeys by sea using only small boatsacross the South China Sea for Southeast Asiancountries. Vietnamalso initially refused to allow Chinese ships that were sent by the Beijing government to repatriate the Hoa back to China. The Hanoigovernment also denied that the persecution of Hoa was taking place. Then when the Hanoi government allowed the Hoa to leave thecountry, it imposed exorbitant fees before granting exit visas. Furthermore, North Vietnamese troops in thenorthern Vietnamese frontier regions forced ethnic Chinese who lived there torelocate to the Chinese side of the China-Vietnam border.

Vietnamand China also had a numberof long-standing territorial disputes, including over a piece of land with anarea of 60 km2, but primarily in the Gulfof Tonkin, and in the Spratly and Paracel Islandsin the South China Sea. The dispute over the Spratly and Paracel Islands became even more pronouncedafter it was speculated that the surrounding waters potentially contained largequantities of petroleum resources.

The Vietnamese also generally distrusted the Chinese forhistorical reasons. The ancient Chineseemperors had long viewed Vietnamas an integral part of China,and brought the Vietnamese under direct Chinese rule for over a millennium (111B.C.–938 A.D.). Then during the VietnamWar, the Vietnamese accepted Chinese military support with some skepticism, andlater claimed that Chinaprovided aid in order to bring Vietnamunder the Chinese sphere of influence. Furthermore, China’simproving relations with the United Statesfollowing U.S. President Richard Nixon’s visit to Beijingin 1972 also was viewed by North Vietnam as a betrayal to its reunificationstruggle during the Vietnam War. In May1978, with Cambodian-Vietnamese relations almost at the breaking point, China cut back on economic aid to Vietnam;within two months, it was ended completely. Also in 1978, Chinaclosed off its side of the Chinese-Vietnamese land border.

Meanwhile, just as its ties with Chinawere breaking down, Vietnamwas strengthening its relations with the Soviet Union. In 1975, the Soviets provided large financialassistance to Vietnam’spost-war reconstruction and five-year development program. Two events in 1978 brought Vietnam firmlyunder the Soviet sphere of influence: in June, Vietnam became a member of theSoviet-led Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (Comecon) and in November,Vietnam and the Soviet Union signed the “Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation”,a mutual defense pact that stipulated Soviet military and economic support toVietnam in exchange for the Vietnamese allowing the Soviets to use air andnaval facilities in Vietnam. The treatyalso formalized the Soviet and Chinese domains in Indochina, with Vietnam aligned with the Soviet Union, and Cambodia aligned with China.

China nowsaw itself surrounded by the Soviet Union to the north and Vietnam to the south. But Vietnamalso saw itself threatened by hostile forces in the north (China) and southwest (Cambodia). Vietnamthen made its move in late December 1978, when it invaded Cambodia and conquered the countryin a lightning offensive. Chineseauthorities were infuriated, as their ally, the Khmer Rouge regime, had beentoppled by the Vietnamese invasion. Since one year earlier (1978), tensions between China and Vietnam had been rising, causingmany incidents of armed clashes and cross-border raids. In January 1979, the Hanoigovernment accused Chinaof causing over 200 violations of Vietnamese territory.

By February 1979, 30 divisions of the People’s LiberationArmy, or PLA (China’sarmed forces) were massed along the border. On February 15, 1979, Chinaannounced its plan to attack Vietnam. Also on that day, China’s1950 “Treaty of Friendship, Alliance, and MutualAssistance” with the Soviet Union ended, thus freeing China from its obligation to pursuenon-aggression against a Soviet ally. Because of the threat of Soviet intervention from the north, on February16, Chinese authorities declared that it was also prepared to go to war withthe Soviet Union. By this time, the bulk of Chinese forces(some 1.5 million troops) were concentrated along the northern border, while300,000 Chinese civilians in these border regions were evacuated.

February 16, 2021

February 16, 1974 – Second Iraqi-Kurdish War: The Iraqi government offers a revised autonomy plan to Kurds

In June 1973, Mustafa Barzani, leader of the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and representing the Iraqi Kurdish people, made a formal claim to Kirkuk, a major city in northern Iraq. But in December of that year, the Iraqi government released a revised Kurdish autonomy plan that did not include Kirkuk. As expected, Barzani rejected the proposal, and negotiations resumed in January 1974. Then on February 16, 1974, as the four-year deadline approached to implement Kurdish autonomy as stipulated in the Iraqi-Kurdish Autonomy Agreement of 1970, the government released yet another autonomy plan which, like the previous proposals, granted broad political, social, and economic concessions to the Kurds, but did not include Kirkuk. The government also declared that it would carry out the plan on March 11, 1974.

Aware that Barzani would reject the proposal, the Iraqigovernment went ahead with implementation, forming a Kurdish provincial counciland legislative assembly with the cooperation of Kurdish factions that opposedBarzani. On March 12, 1974, thegovernment gave Barzani 15 days to accept the plan. Barzani ignored the ultimatum.

The Kurds’ combat capability centered on the paramilitaryorganization called Peshmerga, which was controlled by Barzani. War broke out on March 12, 1974, one dayafter the autonomy law came into effect. Anticipating the resumption of hostilities, both the Iraqi Armed Forcesand Peshmerga had amassed weapons during the intervening period.

Iraq and other countries in the Middle East.

Iraq and other countries in the Middle East.(Taken from Second Iraqi-Kurdish War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Background In1961, war broke out between the Iraqi Army and Kurdish rebels because of theIraqi government’s inaction regarding the autonomy of Iraqi Kurdistan (previousarticle). Ten years of fighting led toinconclusive results, forcing the government to offer the Kurds a new proposal forautonomy. Negotiations held betweenMustafa Barzani, leader of the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) representingthe Kurds, and Iraqi Vice-President Saddam Hussein, led to the establishment ofthe Kurdish Autonomous Region in March 1970 under the Iraqi-Kurdish AutonomyAgreement.

The agreement, which gave broad national and regionalpolitical, economic, and social concessions to the Kurds, was scheduled to beimplemented in four years, i.e. starting in March 1974, subject to the resultsof a population census to determine the territorial extent of the new Kurdishautonomous region. The census itselfimmediately became the subject of contention, specifically with regards to theoil-rich region of Kirkuk (which contributed 40%of Iraq’soil production). Barzani was adamant inhis claim that Kirkukformed part of the Kurdish people’s traditional homeland and thus must beincluded in the autonomous region. TheIraqi government and Barzani agreed to defer carrying out the census andinstead negotiated the other, less contentious points; as a result, the censuswas not undertaken.

Iraq showing location of Iraqi Kurdistan (shaded).

Iraq showing location of Iraqi Kurdistan (shaded).A previous population census for Kirkuk, taken in 1957, had shown that withinthe city, Kurds did not form the largest ethnic group (Turkish speakers –37.5%, Kurds – 33%, Arabs – 22%); they did, however, across the province (Kurds– 48%, Arabs 28%, Turkmen – 21%). (Another population census, conducted in 1965, was rejected outright bythe KDP and thus not seriously taken up in the discussions.) Soon thereafter, Barzani accused thegovernment of carrying out policies that deliberately resettled ethnic Arabsfrom other parts of the country into economically important areas of Kurdistan in order to alter the population ratios to thedisadvantage of the local Kurdish population. This Arab influx ostensibly formed part of the government’s so-called“Arabization” programs and took place in Kirkuk,as well as other oil-rich areas such as Khanaqin and Sinjar.

In June 1973, Barzani made a formal claim to Kirkuk. But in Decemberof that year, the Iraqi government released a revised Kurdish autonomy planthat did not include Kirkuk. As expected, Barzani rejected the proposal,and negotiations resumed in January 1974. Then on February 16, 1974, as the four-year deadline approached toimplement Kurdish autonomy as stipulated in the Iraqi-Kurdish AutonomyAgreement of 1970, the government released yet another autonomy plan which,like the previous proposals, granted broad political, social, and economicconcessions to the Kurds, but did not include Kirkuk. The government also declared that it wouldcarry out the plan on March 11, 1974.

Aware that Barzani would reject the proposal, the Iraqigovernment went ahead with implementation, forming a Kurdish provincial counciland legislative assembly with the cooperation of Kurdish factions that opposedBarzani. On March 12, 1974, thegovernment gave Barzani 15 days to accept the plan. Barzani ignored the ultimatum.

The Kurds’ combat capability centered on the paramilitaryorganization called Peshmerga, which was controlled by Barzani. War broke out on March 12, 1974, one day afterthe autonomy law came into effect. Anticipating the resumption of hostilities, both the Iraqi Armed Forcesand Peshmerga had amassed weapons during the intervening period.

February 15, 2021

On February 15, 1979 – Sino-Vietnamese War: China announces plan to attack Vietnam

By February 1979, 30 divisions of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA, China’s armed forces) were massed along the China-Vietnam border. On February 15, 1979, China announced its plan to attack Vietnam. Also on that day, China’s 1950 “Treaty of Friendship, Alliance, and Mutual Assistance” with the Soviet Union ended, thus freeing China from its obligation to pursue non-aggression against a Soviet ally. Because of the threat of Soviet intervention from the north, on February 16, Chinese authorities declared that it was also prepared to go to war with the Soviet Union. By this time, the bulk of Chinese forces (some 1.5 million troops) were concentrated along the northern border with the Soviet Union, while 300,000 Chinese civilians in these border regions were evacuated.

On February 17, 1979, some 200,000 PLA troops, supported byarmor and artillery, attacked along two fronts across the 1,300-kilometerChina-Vietnam border. China officially announced that its offensivewas a “self-defense counterattack” to “teach Hanoi a lesson”. The Sino-Vietnamese War hadbegun.

(Taken from Sino-Vietnamese War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

Background Inlate December 1978, Vietnaminvaded Cambodia,and within two weeks, its forces toppled the Khmer Rouge government, and set upa new Cambodian government that was allied with itself (previous article). The Khmer Rouge had been an ally of China, and as aresult, Chinese-Vietnamese relations deteriorated. In fact, relations between China and Vietnam had been declining in theyears prior to the invasion.

During the Vietnam War (separate article), North Vietnam received vital military andeconomic support from China,and also from the Soviet Union. But as Chinese-Soviet relations had been decliningsince the early 1960s (with both countries nearly going to war in 1969), NorthVietnam was forced to maintain a delicate balance in its relations between itstwo patrons in order to continue receiving badly needed weapons and funds. But after the communist victory in April1975, the reunified Vietnamhad a gradual falling out with Chinaover two issues: the persecution of ethnic Chinese in Vietnam, and adisputed border.

Following the Vietnam War, the Vietnamese central governmentin Hanoi launched a campaign to break down thefree-market economic system in the former South Vietnam to bring it in linewith the country’s centrally planned socialist economy. Ethnic Chinese in Vietnam (called Hoa), whocontrolled the South’s economy, were subject to severe economic measures. Many Hoa were forced to close down theirbusinesses, and their assets and properties were seized by the government. Vietnamese citizenship to the Hoa was alsovoided. The government also forced tensof thousands of Hoa into so-called “New Economic Zones”, which were located inremote mountainous regions. There, theyworked as peasant farmers under harsh conditions. The Hoa also were suspected by the governmentof plotting or carrying out subversive activities in the North.

As a result of these repressions, hundreds of thousands ofHoa (as well as other persecuted ethnic minority groups) fled the country. The Hoa who lived in the North crossedoverland into China, whilethose in the South went on perilous journeys by sea using only small boatsacross the South China Sea for Southeast Asiancountries. Vietnamalso initially refused to allow Chinese ships that were sent by the Beijing government to repatriate the Hoa back to China. The Hanoigovernment also denied that the persecution of Hoa was taking place. Then when the Hanoi government allowed the Hoa to leave thecountry, it imposed exorbitant fees before granting exit visas. Furthermore, North Vietnamese troops in thenorthern Vietnamese frontier regions forced ethnic Chinese who lived there torelocate to the Chinese side of the China-Vietnam border.

Vietnamand China also had a numberof long-standing territorial disputes, including over a piece of land with anarea of 60 km2, but primarily in the Gulfof Tonkin, and in the Spratly and Paracel Islandsin the South China Sea. The dispute over the Spratly and Paracel Islands became even more pronouncedafter it was speculated that the surrounding waters potentially contained largequantities of petroleum resources.

The Vietnamese also generally distrusted the Chinese forhistorical reasons. The ancient Chineseemperors had long viewed Vietnamas an integral part of China,and brought the Vietnamese under direct Chinese rule for over a millennium (111B.C.–938 A.D.). Then during the VietnamWar, the Vietnamese accepted Chinese military support with some skepticism, andlater claimed that Chinaprovided aid in order to bring Vietnamunder the Chinese sphere of influence. Furthermore, China’simproving relations with the United Statesfollowing U.S. President Richard Nixon’s visit to Beijingin 1972 also was viewed by North Vietnam as a betrayal to its reunificationstruggle during the Vietnam War. In May1978, with Cambodian-Vietnamese relations almost at the breaking point, China cut back on economic aid to Vietnam; withintwo months, it was ended completely. Also in 1978, Chinaclosed off its side of the Chinese-Vietnamese land border.

Meanwhile, just as its ties with Chinawere breaking down, Vietnamwas strengthening its relations with the Soviet Union. In 1975, the Soviets provided large financialassistance to Vietnam’spost-war reconstruction and five-year development program. Two events in 1978 brought Vietnam firmlyunder the Soviet sphere of influence: in June, Vietnam became a member of theSoviet-led Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (Comecon) and in November,Vietnam and the Soviet Union signed the “Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation”,a mutual defense pact that stipulated Soviet military and economic support toVietnam in exchange for the Vietnamese allowing the Soviets to use air andnaval facilities in Vietnam. The treatyalso formalized the Soviet and Chinese domains in Indochina, with Vietnam aligned with the Soviet Union, and Cambodia aligned with China.

China nowsaw itself surrounded by the Soviet Union to the north and Vietnam to thesouth. But Vietnamalso saw itself threatened by hostile forces in the north (China) and southwest (Cambodia). Vietnamthen made its move in late December 1978, when it invaded Cambodia andconquered the country in a lightning offensive. Chinese authorities were infuriated, as their ally, the Khmer Rougeregime, had been toppled by the Vietnamese invasion. Since one year earlier (1978), tensionsbetween China and Vietnam hadbeen rising, causing many incidents of armed clashes and cross-borderraids. In January 1979, the Hanoi government accused China of causing over 200violations of Vietnamese territory.

By February 1979, 30 divisions of the People’s LiberationArmy, or PLA (China’sarmed forces) were massed along the border. On February 15, 1979, Chinaannounced its plan to attack Vietnam. Also on that day, China’s1950 “Treaty of Friendship, Alliance, and MutualAssistance” with the Soviet Union ended, thus freeing China from itsobligation to pursue non-aggression against a Soviet ally. Because of the threat of Soviet interventionfrom the north, on February 16, Chinese authorities declared that it was alsoprepared to go to war with the Soviet Union. By this time, the bulk of Chinese forces(some 1.5 million troops) were concentrated along the northern border, while300,000 Chinese civilians in these border regions were evacuated.