Daniel Orr's Blog, page 74

January 14, 2021

January 14, 1943 – World War II: The Casablanca Conference is held

On January 14, 1943, the Western Allies, United States andGreat Britain, met at the Casablanca Conference to discuss planning andstrategy, particularly for the ongoing European theatre of World War II. U.S.President Franklin D. Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchillled the delegations of their respective countries. Soviet leader Joseph Stalindeclined to attend, stating that the ongoing Battle of Stalingrad required hispresence in the Soviet Union. A delegation ofthe Free French forces also attended, led by Generals Charles de Gaulle andHenri Giraud.

The conference produced the Casablanca Declaration, which contained the stipulation that the Allies would accept only the “unconditional surrender” of Germany and Japan.

(Taken from Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

“Big Three” Allied War Conferences The United States, Britain, and Soviet Union, the so-called “Big Three” Powers, met in two major war-time conferences, at Tehran (November 28 – December 1, 1944) and Yalta (February 4-11, 1945), and in the immediate post-war period, at Potsdam (July 17-August 2, 1945). At the Tehran (Iran) Conference, the Big Three agreed to align military strategy. At the Yalta Conference (Yalta, Crimea, USSR) which was attended by U.S. President Roosevelt, British Prime Minister Churchill, and Soviet leader Stalin, the Allies, now in an overwhelming military position, agreed on the disposition of post-war Germany and Europe. By then, Stalin was negotiating in a superior position, as his Red Army was only 40 miles (65 km) from Berlin. Stalin agreed to join the war in the Asia-Pacific against Japan, and become a member of the United Nations (both requested by the United States), but in return persuaded Roosevelt and Churchill to allow the following: that the Soviet-Polish border be moved to the Curzon Line, that the Soviets gain the South Sakhalin and Kuril Islands from Japan, that the Port Arthur lease be restored to the Soviets, and that Mongolia (a Soviet satellite polity since 1924) been detached from China.

Of major contention at Yalta was the issue of Poland, asRoosevelt and Churchill wanted to return the Polish government-in-exile (inLondon) to power, while Stalin insisted on installing the pro-Soviet governmentalready operating in recaptured Polish territories In fact, Poland formed only part of thelarger issue regarding the political future of Eastern Europe, where Stalinwanted to impose a Soviet sphere of influence to safeguard against anotherinvasion from the West, while Roosevelt and Churchill wanted democraticgovernments to be established there. Instead, the Big Three signed the “Declaration of Liberated Europe”,where they agreed that European nations must be allowed “to create democraticinstitutions of their own choice” and to “the earliest possible establishmentthrough free elections [of] governments responsive to the will of the people”. Free elections were to be conducted in Polandas well, and the Soviet-sponsored provisional government, while remainingpredominant, would be encouraged to include non-communists “on a broaddemocratic basis”.

In the Potsdam agreement, the “Big Three”, now led by U.S.President Harry Truman (succeeding Roosevelt), British Prime Minister ClementAtlee (succeeding Churchill), and Stalin reaffirmed previous agreements withregards to dealing with post-war Germany and the territorial changes demandedby Stalin. As well, Germany was required to pay warreparations, and ethnic Germans were to be expelled from the former Germanlands and forced to move to within the new German borders. As Soviet domination of Poland was now a fait accompli, theWestern Allies acquiesce to the authority of the pro-Soviet Polish governmentin that country.

January 13, 2021

January 13, 1935 – Interwar period: A plebiscite in the Saar region shows that 90% of residents want re-integration with Nazi Germany

On January 13, 1935, a plebiscite conducted in the Saar region showed that 90% of residents desired to bereintegrated with Nazi Germany. The League of Nations, which had been mandated bythe 1919 Treaty of Versailles to administer the Saar for 15 years, returned theterritory to Germanyfollowing the plebiscite.

(Taken from Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

Post-World War IPacifism Because World War I had caused considerable toll on lives andbrought enormous political, economic, and social troubles, a genuine desire forlasting peace prevailed in post-war Europe,and it was hoped that the last war would be “the war that ended all wars”. By the mid-1920s, most European countries,especially in the West, had completed reconstruction and were on the road toprosperity, and pursued a policy of openness and collective security. This pacifism led to the formation in January1920 of the League of Nations (LN), an international organization which hadmembership of most of the countries existing at that time, including most majorWestern Powers (excluding the United States). The League had the following aims: to maintain world peace throughcollective security, encourage general disarmament, and mediate and arbitratedisputes between member states. In thepacifism of the 1920s, the League resolved a number of conflicts (and had somefailures as well), and by mid-decade, the major powers sought the League as aforum to engage in diplomacy, arbitration, and disarmament.

In September 1926, Germanyended its diplomatic near-isolation with its admittance to the League of Nations. This came about with the signing in December 1926 of the Locarno Treaties(in Locarno, Switzerland),which settled the common borders of Germany,France, and Belgium. These countries pledged not to attack eachother, with a guarantee made by Britainand Italyto come to the aid of a party that was attacked by the other. Future disputes were to be resolved througharbitration. The Locarno Treaties alsodealt with Germany’s easternfrontier with Poland and Czechoslovakia,and although their common borders were not fixed, the parties agreed thatfuture disputes would be settled through arbitration. The Treaties were seen as a high point in international diplomacy, and ushered in a climate of peacein Western Europe for the rest of the1920s. A popular optimism, called “thespirit of Locarno”,gave hope that all future disputes could be settled through peaceful means.

In June 1930, the last French troops withdrew from the Rhineland, ending the Allied occupation five yearsearlier than the original fifteen-year schedule. And in March 1935, the League of Nationsreturned the Saar region to Germanyfollowing a referendum where over 90% of Saar residents voted to bereintegrated with Germany.

In August 1938, at the urging of the United States and France, the Kellogg-BriandPact (officially titled “General Treatyfor Renunciation of War as an Instrument of National Policy”) was signed, whichencouraged all countries to renounce war and implement a pacifist foreignpolicy. Within a year, 62 countriessigned the Pact, including Britain,Germany, Italy, Japan,the Soviet Union, and China. In February 1929, the Soviet Union, asignatory and keen advocate of the Pact, initiated a similar agreement, calledthe Litvinov Protocol, with its Eastern European neighbors, which emphasizedthe immediate implementation of the Kellogg-Briand Pact among themselves. Pacifism in the interwar period alsomanifested in the collective efforts by the major powers to limit theirweapons. In February 1922, the fivenaval powers: United States,Britain, France, Italy,and Japansigned the Washington Naval Treaty, which restricted construction of the largerclasses of warships. In April 1930,these countries signed the London Naval Treaty, which modified a number ofclauses in the Washingtontreaty but also regulated naval construction. A further attempt at naval regulation was made in March 1936, which wassigned only by the United States, Britain, and France, since by this time, theprevious other signatories, Italy and Japan, were pursuing expansionistpolicies that required greater naval power.

An effort by the League of Nations and non-League member United States to achieve general disarmament inthe international community led to the World Disarmament Conference in Geneva in 1932-1934,attended by sixty countries. The talksbogged down from a number of issues, the most dominant relating to thedisagreement between Germany and France, with the Germans insisting on beingallowed weapons equality with the great powers (or that they disarm to thelevel of the Treaty of Versailles, i.e. to Germany’s current militarystrength), and the French resisting increased German power for fear of aresurgent Germany and a repeat of World War I, which had caused heavy Frenchlosses. Germany,now led by Adolf Hitler (starting in January 1933), pulled out of the WorldDisarmament Conference, and in October 1933, withdrew from the League of Nations. The Genevadisarmament conference thus ended in failure.

January 12, 2021

January 12, 1958 – Ifni War: Saharan Liberation Army revolutionaries attack El-Aaiún

On January 12, 1958, Saharan Liberation Army (SLA) revolutionariesattacked El-Aaiún, the capital of Spanish Sahara,but were repulsed. The 13th Banderas,a battalion of the Spanish Legion, pursued the retreating revolutionaries fromthe city but was caught in an ambush at Edchera. Some of the war’s most intense fightingfollowed, with the Spanish fending off repeated enemy attacks and more units onboth sides joining the battle. Ultimately, the revolutionaries withdrew into the night after sustainingsome 240 killed. Spanish losses alsowere heavy, officially placed at 37 dead and 50 wounded, but perhaps higher andeven as many as the number of enemy casualties.

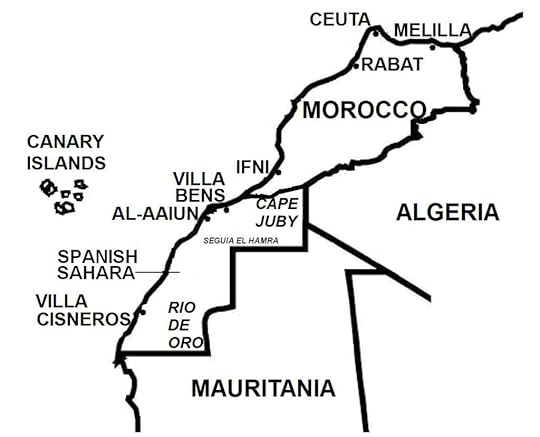

Spanish possessions in northwest Africa with adjacent countries.

Spanish possessions in northwest Africa with adjacent countries.(Taken from Ifni War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Background In1956, Morocco gained fullindependence after Franceand Spainended their 44-year protectorate and returned political and territorial controlto Mohammed V, the Moroccan Sultan. Aperiod of rising tensions and violence had preceded Morocco’s independence which nearlybroke out into open hostilities. While France fully ended its protectorate, Spain only did so with its northern zone,retaining control of the southern zone (consisting of Cape Jubyand the interior area called the Tarfaya Strip). At Morocco’s independence, apart fromMorocco’s southern zone, Spain held a number of other territories in NorthAfrica that the Spanish government viewed as integral parts of Spain (i.e. theywere not colonies or protectorates); these included Ceuta and Melilla whichSpain had controlled since the 1500s; Plazas de soberanía (English: Places ofsovereignty), a motley of tiny islands and small areas bordering the MoroccanMediterranean coastline; and Spanish Sahara, a vast territory half the size ofmainland Spain that the Spanish government had gained in 1884 as a result ofthe Berlin Conference during the period known as the “Scramble for Africa”,where European powers wrangled for their “share” of Africa.

Spain declared having historical ties, by way of the SpanishEmpire, to the Ifni region (traced incorrectly to Santa Cruz de la Mar Pequeña,a 15th century Spanish settlement which was actually located further south ofIfni), Villa Cisneros, founded in 1502 and located in Spanish Sahara, and thePlazas de soberanía. In 1946, Spain merged the regions of Ifni, Cape Jubyand Tarfaya Strip (southern zone of the Spanish protectorate), and Spanish Sahara into a single administrative unit calledSpanish West Africa (Figure 13).

The Ifni region, which had at its capital the coastal cityof Sidi Ifni,would become the focal point as well as lend its name to the coming war. After its defeat in the Spanish-Moroccan Warin April 1860, Morocco cededIfni to Spainas a result of the Treaty of Tangiers.

Shortly after Morocco gained its independence, anultra-nationalist movement, the Istiqlal Party led by Allal Al Fassi, advocated“Greater Morocco”, a political ideology that desired to integrate allterritories that had historical ties to the Moroccan Sultanate with the modernMoroccan state. As envisioned, Greater Moroccowould consist of, apart from present-day Moroccoitself, western Algeria, Mauritania, and northwest Mali – and all Spanish possessions in North Africa.

Officially, the Moroccan government did not subscribe to orespouse “Greater Morocco”, but did not suppress and even tacitly supportedirredentist advocates of this ideology. As a result, the Moroccan Army did not actively participate in thecoming war; instead, the Moroccan Army of Liberation (MAL), which was anassortment of several Moroccan militias that had organized and risen up againstthe French protectorate, carried out the war against the Spanish (and French).

Shortly after Moroccogained its independence, civil unrest broke out in Ifni,which included anti-Spanish protest demonstrations and violence targetingpolice and security forces. Infiltratorsbelonging to MAL later began supporting these activities. The unrest prompted the central government inmainland Spain,led by General Francisco Franco, to send Spanish troops, including units of theSpanish Legion, to Spanish West Africa, whose security units until thenconsisted mostly of personnel recruited from the local population.

Meanwhile, MAL militias, comprising some 4,000–5,000Moukhahidine (“freedom fighters”) and led by Ben Hamou, a Moroccan formermercenary officer of the French Foreign Legion, had deployed near southernMoroccan and Spanish Sahara, and soon werejoined by Sahrawi Berber and Arab fighters; at their peak, some 30,000revolutionaries would take part in the conflict.

January 11, 2021

January 11, 1923 – Interwar period: Troops from France and Belgium occupy the Ruhr region to force Germany to make war reparation payments

When Germany

defaulted on war reparations in December 1922, French and Belgian forces

occupied the Ruhr region, Germany’s

industrial heartland, to force payment.

At the urging of the Weimar government, Ruhr authorities and residents launched passive resistance;

shop owners refused to sell goods to the foreign troops, and coal miners and

railway employees did not work. Both Germany and France suffered financial losses as

a result. Following United States intervention, in August 1924, the

two sides agreed on the Dawes Plan , where German reparations payments were

restructured, and the U.S.

and British government extended loans to help with Germany’s economic recovery. French troops then withdrew From the Ruhr

region. Subsequently in August 1929,

with the adoption of the Young Plan , Germany’s reparations obligations

were reduced and payment was extended to a period of 58 years. As a result of these and other measures,

including stronger fiscal control, introduction of a new currency, and easing

bureaucratic hurdles, Germany’s

economy recovered and expanded during the second half of the 1920s. Reparations were made, foreign investments

entered the domestic market, and civil unrest declined.

(Taken from Weimar Republic – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

Near the end of World War I, Germany was beset by severe internal tumult, as

industrial workers, including those involved in war production, launched strike

actions that were fomented by communist political and labor groups that long

opposed Germany’s

involvement in the war. Then in late

October-early November 1918 when German defeat in the war became imminent,

German Navy sailors at the ports of Wilhelmshaven

and Kiel

mutinied, and refused to obey their commanders who had ordered them to prepare

for one final decisive battle with the British Navy. Within a few days, the unrest had spread to

many cities across Germany,

sparking a full-blown communist-led revolt (the German Revolution) that peaked

in January 1919, when democracy-leaning forces quelled the uprising. But in the chaos following German defeat in

World War I, the monarchy under Kaiser (King) Wilhelm II ended, and was

replaced by a social democratic state, the Weimar

Republic (named after the city of Weimar, where the new

state’s constitution was drafted).

The Weimar Republic, which governed Germany from 1919-1933, was

permanently beset by fierce political opposition and also experienced two

failed coup d’états. A full spectrum of

opposition political parties, from the moderate to radical right-wing,

ultra-nationalist, and monarchist parties, to the moderate to extreme

left-wing, socialist, and communist parties, wanted to put and end to the

Weimar Republic, either through elections or by paramilitary violence , and to

be replaced by a political system suited to their respective ideologies. One radical political movement that emerged

at this time was the National Socialist German Workers’ Party, which came to be

known in the West as the Nazi Party, and its members called Nazis, and led by

Adolf Hitler. The Nazis participated in

the electoral process, but wanted to end the Weimar democratic system. Hitler denounced the Versailles treaty, advocated totalitarianism,

held racial views that extolled Germans as the “master race” and disparaged

other races, such as Slavs and Jews, as “sub-humans”. The Nazis also were vehemently anti-communist

and advocated lebensraum (“living space”) expansionism in Eastern Europe and Russia.

A common theme among right-wing, ultra-nationalist, and ex-military

circles was the idea that in World War

I, Germany

was not defeated on the battlefield.

Rather, German defeat was caused by traitors, notably the workers who

went on strike at a critical stage of the war and thus deprived soldiers at the

front lines of their much-needed supplies.

As well, communists and socialists were to blame, since they fomented

civilian unrest that led to the revolution; Jews, since they dominated the

communist leadership; and the Weimar Republic since it signed the Versailles treaty. This concept, called the “stab in the back”

theory, postulated that in 1918, Germany was on the brink of victory

, but lost after being stabbed in the back by the “November criminals”, i.e.

the communists, Jews, etc. After coming

to power, the Nazis would appropriate the “stab in the back” theory to fit

their political agenda in order to denounce the Versailles treaty, suppress opposition, and

establish a dictatorship.

Germany,

financially ravaged by the war, was hard pressed to meet its reparations

obligations. The government printed

enormous amounts of money to cover the deficit and also pay off its war debts,

but this led to hyperinflation and astronomical prices of basic goods, sparking

food riots and worsening the economy.

Then when Germany

defaulted on reparations in December 1922, French and Belgian forces occupied

the Ruhr region, Germany’s

industrial heartland, to force payment.

At the urging of the Weimar government, Ruhr authorities and residents launched passive

resistance; shop owners refused to sell goods to the foreign troops, and coal

miners and railway employees did not work.

Both Germany and France suffered

financial losses as a result. Following United States intervention, in August 1924, the

two sides agreed on the Dawes Plan , where German reparations payments were

restructured, and the U.S.

and British government extended loans to help with Germany’s economic recovery. French troops then withdrew From the Ruhr

region. Subsequently in August 1929,

with the adoption of the Young Plan , Germany’s reparations obligations

were reduced and payment was extended to a period of 58 years. As a result of these and other measures,

including stronger fiscal control, introduction of a new currency, and easing

bureaucratic hurdles, Germany’s

economy recovered and expanded during the second half of the 1920s. Reparations were made, foreign investments

entered the domestic market, and civil unrest declined.

The Versailles treaty was a

heavy blow to the German national morale, and was seen as a humiliation to the Weimar state, which had

been forced by the Allies to agree to it under threat of continuing the

war. From the start, the Weimar government was determined to implement re-armament

in violation of the Versailles

treaty. Throughout its existence from

1919-1933, the Weimar Republic carried out small, clandestine, and subtle

means to build its military forces, and was only restrained by the presence of

Allied inspectors that regularly visited Germany

to ensure compliance with the Versailles

treaty. These methods included secretly

reconstituting the German general staff, equipping and training the police for

combat duties, and tolerating the presence of paramilitaries with an eye to

later integrate them as reserve units in the regular army.

Also important to Germany’s

secret rearmament was the Weimar government’s

opening ties with the Soviet Union. Relations began in April 1922 with the

signing of the Treaty of Rapallo, which established diplomatic ties, and

furthered in April 1926 with the Treaty of Berlin, where both sides agreed to

remain neutral if the other was attacked by another country. In the aftermath of World War I, the Germans

and Soviets saw the need to help each other, as they were outcasts in the

international community: the Allies blamed Germany

for starting the war, and also turned their backs on the Soviet

Union for its communist ideology.

Military cooperation was an important component to

German-Soviet relations. At the

invitation of the Soviet government, Weimar Germany built several military facilities in the

Soviet Union; e.g. an aircraft factory near Moscow,

an artillery facility near Rostov, a flying

school near Lipetsk, a chemical weapons plant in

Samara, a naval base in Murmansk,

etc. In this way, Germany achieved some rearmament away from

Allied detection, while the Soviet Union, yet

in the process of industrialization from an agricultural economy, gained access

to German technology and military theory.

January 10, 2021

January 10, 1966 – Indian-Pakistani War of 1965: A peace treaty is signed

On January 10, 1966, under mediation efforts by the Soviet Union, India and Pakistan signed the Tashkent Declaration (in Tashkent, Uzbek SSR; present-day Uzbekistan) that ended the Indian-Pakistani War of 1965. The peace agreement stipulated, among other things, that the armies of both sides return to their original positions along the ceasefire line before the start of the war. The two sides carried out the agreement’s stipulations. The 1965 war, therefore, achieved no territorial gains on either side. Furthermore, India’s overwhelming military superiority also fell short of achieving a total victory on the battlefield.

After the war, Pakistan

and India began to distance

themselves from the United

States and other Western powers and looked

toward other sources of military support.

In particular, Pakistan

felt betrayed by the United States

and drew closer to China and

the Soviet Union. Similarly, India

established friendly relations with the Soviet Union

and soon began to purchase Russian-made weapons.

Armed clashes between Indian and Pakistani forces at Rann of Kutch in April 1965 were a precursor to a full-scale war in Kashmir five months later.

Armed clashes between Indian and Pakistani forces at Rann of Kutch in April 1965 were a precursor to a full-scale war in Kashmir five months later.(Taken from Indian-Pakistani War of 1965 – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

Background As a

result of the Indian-Pakistani War of 1947 (previous article), the former

Princely State of Kashmir was divided militarily under zones of occupation by

the Indian Army and the Pakistani Army.

Consequently, the governments of India

and Pakistan

established local administrations in their respective zones of control, these

areas ultimately becoming de facto territories of their respective

countries. However, Pakistan was determined to drive away the

Indians from Kashmir and annex the whole

region. As Pakistan

and Kashmir had predominantly Muslim populations, the Pakistani government believed

that Kashmiris detested being under Indian rule and would welcome and support

an invasion by Pakistan. Furthermore, Pakistan’s

government received reports that civilian protests in Kashmir

indicated that Kashmiris were ready to revolt against the Indian regional

government.

The Pakistani Army believed itself superior to its Indian

counterpart. In early 1965, armed

clashes broke out in disputed territory in the Rann of Kutch in Gujarat State, India (Map 3). Subsequently in 1968, Pakistan was

awarded 350 square miles of the territory by the International Court of

Justice. In 1965, India was still smarting from a defeat to China in the 1962 Sino-Indian War; as a result, Pakistan

believed that the Indian Army’s morale was low.

Furthermore, Pakistan

had upgraded its Armed Forces with purchases of modern weapons from the United States, while India was yet in the midst of

modernizing its military forces.

Indian-Pakistani War of 1965. As in the 1947-49 war, Kashmir was the battle ground for the two rival countries that wanted to annex the whole region.

Indian-Pakistani War of 1965. As in the 1947-49 war, Kashmir was the battle ground for the two rival countries that wanted to annex the whole region.In the summer of 1965, Pakistan

made preparations for invading Indian-held Kashmir. To assist the operation, Pakistani commandos

would penetrate Kashmir’s major urban areas,

carry out sabotage operations against military installations and public

infrastructures, and distribute firearms to civilians in order to incite a

revolt. Pakistani military planners

believed that Pakistan

would have greater bargaining power with the presence of a civilian uprising,

in case the war went to international arbitration.

January 9, 2021

January 9, 1995 – Cenepa War – Ecuador and Peru engage in border fighting, triggering war

By early January 1995, the strong Peruvian presence was

being felt with an increase in military activities near the Ecuadorian forward

outposts. Ecuadorian and Peruvian

patrols encountered each other on January 9 and January 11, with the latter

encounter leading to an exchange of gunfire.

Then on January 21, Peruvian troops were landed by helicopter behind the

Ecuadorian outposts in preparation for a Peruvian full offensive. The infiltration was discovered when an

Ecuadorian patrol spotted some 20 Peruvian soldiers setting up a heliport. Ecuadorian Special Forces were called in;

after a two days’ trek through the jungle, the Ecuadorians located the Peruvian

camp. In the ensuing firefight, the

Ecuadorians dispersed the Peruvians. A

number of Peruvians were killed, while the abandoned weapons and supplies in

the camp were seized.

Both countries mobilized for war, massing their main forces

along the border near the Pacific coast.

The war was confined to the Condor-Cenepa region, however, where the

Peruvians launched many offensives aimed at destroying the Ecuadorian positions

located at the eastern slope of the Condor.

On January 28, Peruvian ground forces, later backed by air cover,

launched successive attempts on the Ecuadorian outposts. The ground attacks involved an uphill climb

against well-entrenched positions. More

attacks were carried out the next day and into early February, with the

Peruvians attempting to outflank the outposts but being met by strong

resistance. On February 1, a Peruvian

advance on Cuevas de los Tayos fell into a minefield, causing several

casualties.

Ecuador and Peru (and other nearby South American countries) as they appear in current maps. For much of the twentieth century, the Ecuador–Peru border was incompletely demarcated, generating tensions and wars between the two countries.

Ecuador and Peru (and other nearby South American countries) as they appear in current maps. For much of the twentieth century, the Ecuador–Peru border was incompletely demarcated, generating tensions and wars between the two countries.(Taken from Cenepa War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

Background The

1981 Paquisha War (previous article)

between Ecuador and Peru left unsettled the border dispute regarding

sovereignty over the Condor Mountain range and the Cenepa River

system located inside the Amazon rainforest.

Peruvian forces achieved a tactical victory by destroying three

Ecuadorian forward outposts and re-established control over the whole eastern

side of the Condor range, although the Ecuadorian government continued to claim

ownership over the whole Condor-Cenepa region.

In the years following the Paquisha War, the two sides strengthened

their areas of control in the region, with the Ecuadorians occupying the peaks

and western slope of the Condor range, and the Peruvians at the Condor’s

eastern slope and Cenepa

Valley. Because of the thick forest cover, Ecuadorian

and Peruvian patrols often accidentally encountered each other, which at the

very worst, led to exchanges of gunfire, but generally ended without incident,

as the two sides had agreed to abide by

the Cartillas de Seguridad y Confianza (Guidelines for Security and

Trust), which lay down the rules to prevent unnecessary bloodshed.

In November 1994, a Peruvian army patrol came upon an enemy

outpost and was told by the Ecuadorian commander there that the location was

situated inside the Ecuadorian Army’s area of control. The Peruvian Army soon learned that the

outpost, which the Ecuadorians named “Base Sur”, was located on the eastern

slope of the Condor, and therefore in the area traditionally under Peruvian

control. Thereafter, the Ecuadorian and

Peruvian local commanders met a number of times to try and work out a

resolution, but nothing came out of the meetings.

With tensions rising by December 1994, Ecuador and Peru

began sending reinforcements and large quantities of weapons and military

equipment to the disputed zone, a difficult and hazardous operation

(particularly for Peru’s Armed Forces because of the greater distance) which

required air transports because of the absence of roads leading to the Condor

region.

Apart from “Base Sur”, the Ecuadorians had set up a number

of other outposts, including “Tiwintza” and “Cueva de los Tayos”, and the

larger “Coangos”, near the top of the Condor Mountain. The camps’ defenses were strengthened by new

minefields laid out at the approaches, and the installation of anti-aircraft

batteries and multiple-rocket launchers; a further boost was provided by the

arrival of Ecuadorian Special Forces and specialized teams equipped with

hand-held surface-to-air missile launchers to be used against Peruvian planes.

By early January 1995, the strong Peruvian presence was

being felt with an increase in military activities near the Ecuadorian forward

outposts. Ecuadorian and Peruvian

patrols encountered each other on January 9 and January 11, with the latter

encounter leading to an exchange of gunfire.

Then on January 21, Peruvian troops were landed by helicopter behind the

Ecuadorian outposts in preparation for a Peruvian full offensive. The infiltration was discovered when an

Ecuadorian patrol spotted some 20 Peruvian soldiers setting up a heliport. Ecuadorian Special Forces were called in;

after a two days’ trek through the jungle, the Ecuadorians located the Peruvian

camp. In the ensuing firefight, the

Ecuadorians dispersed the Peruvians. A

number of Peruvians were killed, while the abandoned weapons and supplies in

the camp were seized.

January 8, 2021

January 8, 1987 – Iran-Iraq War: Start of the Battle of Basra

On January 8, 1987, Iran launched its long-anticipated offensive on Basra, which became the largest and bloodiest battle of the war. Some 600,000 Iranian soldiers took part and faced 400,000 Iraqi defenders. The seven-week offensive, which lasted until late February 1987, saw the Iranians launching successive assaults that succeeded in breaching four of the five Iraqi “dynamic defense” lines, including the modified barriers Fish Lake and Jasim River, and to come to within twelve kilometers of Basra, before being stopped. Iranian casualties were considerable– some 65,000 were killed; 20,000 Iraqi soldiers also perished.

The failure to capture Basra

had a powerful demoralizing effect on Iran: in the aftermath, much fewer

civilians volunteered to join the Revolutionary Guards and Basij, the general

population became war-weary and felt the war was unwinnable, and even the

Iranian leadership stopped plans for further major operations or “final

offensives”.

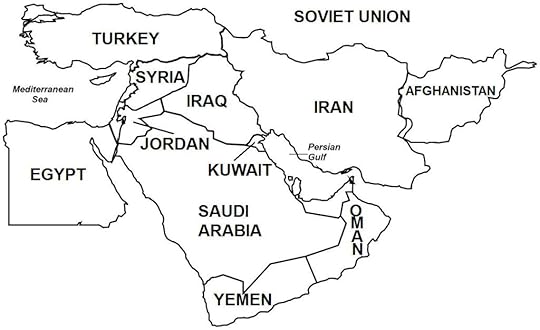

Iran, Iraq, and nearby countries.

Iran, Iraq, and nearby countries.(Excerpts taken from Iran-Iraq War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Background In

1937, the now independent monarchies of Iraq and Iran signed an agreement that

stipulated that their common border on the Shatt al-Arab was located at the low

water mark on the eastern (i.e. Iranian) side all across the river’s length,

except in the cities of Khoramshahr and Abadan, where the border was located at

the river’s mid-point. In 1958, the

Iraqi monarchy was overthrown in a military coup. Iraq

then formed a republic and the new government made territorial claims to the

western section of the Iranian border province of Khuzestan,

which had a large population of ethnic Arabs.

In Iraq,

Arabs comprise some 70% of the population, while in Iran,

Persians make up perhaps 65% of the population (an estimate since Iran’s

population censuses do not indicate ethnicity).

Iran’s demographics

also include many non-Persian ethnicities: Azeris, Kurds, Arabs, Baluchs, and

others, while Iraq’s

significant minority group comprises the Kurds, who make up 20% of the

population. In both countries, ethnic

minorities have pushed for greater political autonomy, generating unrest and a

potential weakness in each government of one country that has been exploited by

the other country.

The source of sectarian tension in Iran-Iraq relations

stemmed from the Sunni-Shiite dichotomy.

Both countries had Islam as their primary religion, with Muslims

constituting upwards of 95% of their total populations. In Iran, Shiites made up 90% of all Muslims

(Sunnis at 9%) and held political power, while in Iraq, Shiites also held a

majority (66% of all Muslims), but the minority Sunnis (33%) led by Saddam and

his Baath Party held absolute power.

In the 1960s, Iran, which was still ruled by a

monarchy, embarked on a large military buildup, expanding the size and strength

of its armed forces. Then in 1969, Iran ended its recognition of the 1937 border

agreement with Iraq,

declaring that the two countries’ border at the Shatt al-Arab was at the

river’s mid-point. The presence of the

now powerful Iranian Navy on the Shatt al-Arab deterred Iraq from

taking action, and tensions rose.

Also by the early 1970s, the autonomy-seeking Iraqi Kurds

were holding talks with the Iraqi government after a decade-long war (the First

Iraqi-Kurdish War, separate article); negotiations collapsed and fighting broke

out in April 1974, with the Iraqi Kurds being supported militarily by

Iran. In turn, Iraq incited Iran’s ethnic minorities to revolt,

particularly the Arabs in Khuzestan, Iranian Kurds, and Baluchs. Direct fighting between Iranian and Iraqi

forces also broke out in 1974-1975, with the Iranians prevailing. Hostilities ended when the two countries

signed the Algiers Accord in March 1975, where Iraq

yielded to Iran’s demand

that the midpoint of the Shatt al-Arab was the common border; in exchange, Iran ended its

support to the Iraqi Kurds.

Iraq was

displeased with the Shatt concessions and to combat Iran’s growing regional military

power, embarked on its own large-scale weapons buildup (using its oil revenues)

during the second half of the 1970s.

Relations between the two countries remained stable, however, and even

enjoyed a period of rapprochement. As a

result of Iran’s assistance

in helping to foil a plot to overthrow the Iraqi government, Saddam expelled

Ayatollah Khomeini, who was living as an exile in Iraq and from where the Iranian

cleric was inciting Iranians to overthrow the Iranian government.

However, Iranian-Iraqi relations turned for the worse

towards the end of 1979 when Ayatollah Khomeini was proclaimed as Iran’s absolute

ruler. Each of the two rival countries

resumed secessionist support for the various ethnic groups in the other

country. Iran’s transition to a full Islamic

State was opposed by the various Iranian ethnic minorities, leading to revolts

by Kurds, Arabs, and Baluchs. The

Iranian government easily crushed these uprisings, except in Kurdistan,

where Iraqi military support allowed the Kurds to fend off Iranian government

forces until late 1981 before also being put down.

Ayatollah Khomeini, in line with his aim of spreading

Islamic revolutions across the Middle East, called on Iraq’s Shiite

majority to overthrow Saddam and his “un-Islamic” government, and establish an

Islamic State. In April 1980, a spate of

violence attributed to the Islamic Dawa Party, an Iran-supported militant

group, broke out in Iraq,

where many Baath Party officers were killed and other high-ranking government

officials barely escaped assassination attempts. In response, the Iraqi government unleashed

repressive measures against radical Shiites, including deporting thousands who

were thought to be ethnic Persians, as well as executing Grand Ayatollah

Mohammad Baqir al-Sadr, which drew widespread condemnation from several Muslim

countries as the religious cleric was highly regarded in the wider Islamic

community.

Throughout the summer of 1980, many border clashes broke out

between forces of the two countries, increasing in intensity and frequency by

September of that year. As to the

official start of the war, the two sides have different interpretations. The Iraqis cite September 4, 1980, when the

Iranian Army carried out an artillery bombardment of Iraqi border towns,

prompting Saddam two weeks later to unilaterally repeal the 1975 Algiers Accord

and declare that the whole Shatt al-Arab lay within the territorial limits of Iraq.

September 22, 1980, however, is generally accepted as the

start of the war, when Iraqi forces launched a full-scale air and ground

offensive into Iran. Saddam believed that his forces were capable

of achieving a quick victory, his confidence borne by the following factors,

all resulting from the Iranian Revolution.

First, as previously mentioned, Iran

faced regional insurgencies from its ethnic minorities that opposed Iran’s adoption

of Islamic fundamentalism. Second, Iran further

was wracked by violence and unrest when secularist elements of the revolution

(liberal democrats, communists, merchants and landowners, etc.) opposed the

Islamist hardliners’ rise to power. The

Islamic state subsequently marginalized these groups and suppressed all forms

of dissent. Third, the revolution

seriously weakened the powerful Iranian Armed Forces, as military elements,

particularly high-ranking officers, who remained loyal to the Shah, was purged

and repressive measures were undertaken to curb the military. Fourth, Iran’s newly established Islamic

government, because it rejected both western democracy and communist ideology,

became isolated internationally, even among Arab and Muslim countries.

January 7, 2021

On January 7, 1979: Cambodian-Vietnamese War: Vietnamese forces capture Phnom Penh

On January 7, 1979, the Vietnamese Army captured the

Cambodian capital of Phnom Penh

in a blitzkrieg campaign and overthrew the Khmer Rouge regime. Pol Pot and his staff, together the bulk of

the Khmer Rouge Army, made a strategic withdrawal to the jungle mountains of

western Cambodia

near the Thai border, where they set up a resistance government.

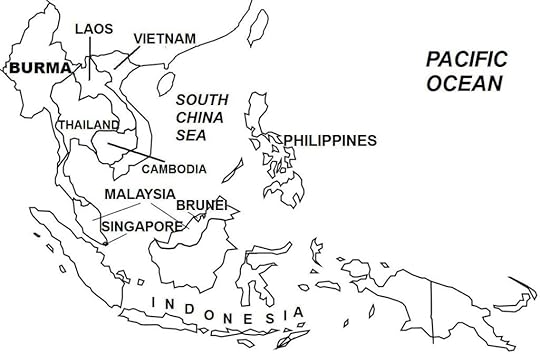

Southeast Asia during the Cambodian-Vietnamese War.

Southeast Asia during the Cambodian-Vietnamese War.(Taken from Cambodian-Vietnamese War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

Background The

revolutionary movements that eventually prevailed in Vietnam

and Cambodia (as well as in Laos)

trace their origin to 1930 when the Vietnamese Communist Party (VCP) was

formed. VCP soon reorganized itself into

the Indochinese Communist Party (ICP) to include membership to Cambodian and

Laotian communists into the Vietnamese-dominated movement. The great majority of ICP Khmers were not

indigenous to Cambodia;

rather they consisted mostly of ethnic Khmers who were native to southern Vietnam, and ethnic Vietnamese living in Cambodia.

In 1951, the ICP split itself into three nationalist

organizations for Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos respectively, i.e. Workers Party

of Vietnam, Khmer People’s Revolutionary Party (KPRP), and Neo Lao Issara. In December 1946, the Viet Minh (or League for

the Independence of Vietnam), a Vietnamese nationalist group that was formed in

World War II to fight the Japanese, began an independence war against French

rule (First Indochina War, separate article).

The Viet Minh prevailed in July 1954.

The 1954 Geneva Accords, which ended the war, divided Vietnam into two military zones, which became

socialist North Vietnam and

West-aligned South Vietnam. War soon broke out between the two Vietnams, with North

Vietnam supported by China

and the Soviet Union; and South Vietnam

supported by the United

States.

This Cold War conflict, called the Vietnam War (separate article) and

which included direct American military involvement in 1965-1970, ended in

April 1975 with a North Vietnamese victory.

As a result, the two Vietnams

were reunified, in July 1976.

Meanwhile in Cambodia,

the local revolutionary struggle ended with the 1954 Geneva Accords, which gave

the country, led by King Sihanouk, full independence from France. The Accords also ended both French rule and

French Indochina, and independence also was granted to Laos and Vietnam. Following the First Indochina War, most of

the Khmer communists moved into exile in North

Vietnam, while those who remained in Cambodia formed

the Pracheachon Party, which participated in the 1955 and 1958 elections. However, government repression forced

Pracheachon Party members to go into hiding in the early 1960s.

By the late 1950s, the Cambodian communist movement

experienced a resurgence that was spurred by a new generation of young,

Paris-education communists who had returned to the country. In September 1960, ICP veteran communists and

the new batch of communists met and elected a Central Committee, and renamed

the KPRP (Kampuchean People’s Revolutionary Party) as the Worker’s Party of

Kampuchea (WPK).

In February 1963, following another government suppression

that led to the arrest of communist leaders, the WPK soon came under the

control of the younger communists, led by Saloth Sar (later known as Pol Pot),

who sidelined the veteran communists whom they viewed as pro-Vietnamese. In September 1966, the WPK was renamed the

Kampuchean Communist Party (KCP).

The KCP and its members, as well its military wing, were

called “Khmer Rouge” by the Sihanouk government. In January 1968, the Khmer Rouge launched a

revolutionary war against the Sihanouk regime, and after Sihanouk was

overthrown in March 1970, against the new Cambodian government. In April 1975, the Khmer Rouge triumphed and

took over political power in Cambodia,

which it renamed Democratic Kampuchea.

During its revolutionary struggle, the Khmer Rouge obtained

support from North Vietnam,

particularly through the North Vietnamese Army’s capturing large sections of

eastern Cambodia,

which it later turned over to its Khmer Rouge allies. But the Khmer Rouge held strong

anti-Vietnamese sentiment, and deemed its alliance with North Vietnam only as a temporary expedient to

combat a common enemy – the United

States in particular, Western capitalism in

general. The Cambodian communists’

hostility toward the Vietnamese resulted from the historical domination by

Vietnam of Cambodia during the pre-colonial period, and the perception that

modern-day Vietnam wanted to

dominate the whole Indochina region.

Soon after coming to power, the Khmer Rouge launched one of

history’s most astounding social revolutions, forcibly emptying cities, towns,

and all urban areas, and sending the entire Cambodian population to the

countryside to become peasant workers in agrarian communes under a feudal-type

forced labor system. All lands and

properties were nationalized, banks, schools, hospitals, and most industries,

were shut down. Money was

abolished. Government officials and

military officers of the previous regime, teachers, doctors, academics,

businessmen, professionals, and all persons who had associated with the Western

“imperialists”, or were deemed “capitalist” or “counter-revolutionary” were

jailed, tortured, and executed. Some 1½

– 2½ million people, or 25% of the population, died under the Khmer Rouge

regime (Cambodian Genocide, previous article).

In foreign relations, the Khmer Rouge government isolated

itself from the international community, expelling all Western nationals,

banning the entry of nearly all foreign media, and closing down all foreign

embassies. It did, however, later allow

a number of foreign diplomatic missions (from communist countries) to reopen in

Phnom Penh. As well, it held a seat in the United Nations

(UN).

The Khmer Rouge was fiercely nationalistic and xenophobic,

and repressed ethnic minorities, including Chams, Chinese, Laotians, Thais, and

especially the Vietnamese. Within a few

months, it had expelled the remaining 200,000 ethnic Vietnamese from the

country, adding to the 300,000 Vietnamese who had been deported by the previous

Cambodian regime.

January 6, 2021

January 6, 1921 – Turkish War of Independence – Greek forces attack the town of Eskişehir

On January 6, 1921, the Greek Army attacked in the direction

of the strategic town of Eskişehir,

but was repulsed at the First Battle of Inonu.

The battle was downplayed by the Greeks as a minor setback, but it

considerably raised the morale of the Turks, who for the first time, had turned

back the enemy. Because of this

development, the Allied Powers (Britain,

France, and Italy) met with

representatives of the Ottoman government and Turkish nationalists in London (known as the

Conference of London) in February-March 1921 in order to negotiate changes to

the Treaty of Sevres, which by this time was impossible to implement. However, the Turkish nationalists were

unyielding in their position that Turkey’s territorial integrity was

non-negotiable and that the Allies must withdraw. As a result, the conference ended without

reaching a settlement.

In early March 1921, with the arrival of reinforcements, the

Greeks attacked again, but were defeated at the Second Battle of Inonu, and

forced to return to Bursa. The Greeks’ southern advance captured Afyon,

but a Turkish attempt to cut the railway line between Afyon and Usak forced the

Greeks to meet and contain the threat, and then withdraw to Usak.

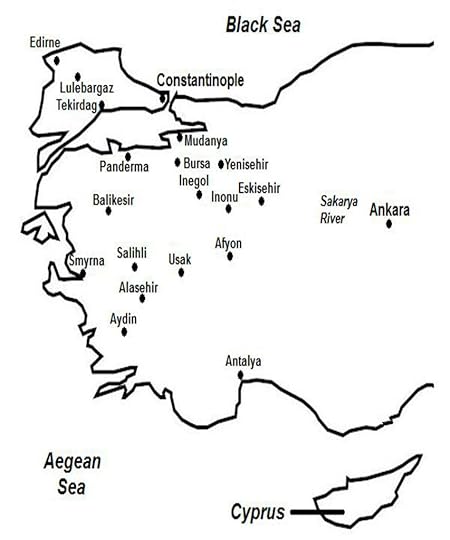

The Western Front in the Turkish War of Independence.

The Western Front in the Turkish War of Independence.(Taken from Turkish War of Independence – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 3)

Western Front Greece had entered World War I on the side of

the Allies because of Britain’s

promise to reward Greece

with a large territorial concession of Ottoman Anatolia at the end of the

war. Greece

particularly was interested in the Ottoman territories that contained a large

ethnic Greek population, notably Smyrna, which

had a sizable to perhaps even a majority Greek population and was the Greeks’

cultural and economic center in Anatolia, and Eastern Thrace, as well as the

islands of Imbros and Tenedos on the Aegean Sea.

As the Ottoman government had repressed ethnic Greeks in

Anatolia during the war, the Allied Powers invoked a stipulation in the

Armistice of Mudros to allow Greek forces to occupy Smyrna.

The presumption was that despite the Ottoman capitulation, ethnic Greeks

continued to be threatened by the Ottomans with massacres and dispossession of

properties, which were reported to have taken place extensively during the war.

A post-war complication arose since Britain, France,

and Italy previously had

signed a treaty (Agreement of St.-Jean-de-Maurienne of April 1917), whereby Smyrna and western Anatolia

were to be allocated to the Italians. At

the Paris Peace Conference held after the war, both the Italian and Greek

delegations lobbied hard for Smyrna; in the end,

the other Allied powers (led by Britain)

voted in favor of Greece.

Then in the Treaty of Sevres of 1920, Italy was granted southern Anatolia centered in Antalya, while Greece

was given western Anatolia around Smyrna (as

well as most of Eastern Thrace). The Italians, however, felt that they had

received the short end of the deal without Smyrna, a resentment that would influence the

outcome of the western front.

On May 16, 1919, with Allied approval, 20,000 Greek soldiers

landed in Smyrna,

where they were greeted as liberators by a large crowd of ethnic Greeks. A commotion broke out when a Turkish gunman

fired at the Greek Army, killing one soldier.

The Greek Army then opened fire, triggering a spate of violence across

the city. When order later was restored,

some 300 Turkish and 100 Greek civilians had been killed; many incidents of

lootings, beatings, rapes, and other crimes also took place.

War Of the Allied

occupations, the Greek entry in Smyrna

greatly provoked the Turks. As a result,

many Turkish guerilla groups formed, while it was at this time that Kemal began

organizing his revolutionary nationalist government. The western front (more commonly known as the

Greco-Turkish War of 1919-1922) began in earnest in mid-1920 (eleven months after

the initial Greek landing) as a result of Britain’s attempt to implement the

newly released Treaty of Sevres. The

treaty was presented to and signed by the Ottoman government, but was not

ratified; Ottoman authorities insisted that the treaty must be concurred to also

by Kemal, who clearly would not agree to it.

In fact, Kemal’s nationalist forces, by this time, were fighting the

French in the southern front and were preparing a major offensive against the

Armenians in the eastern front.

Furthermore, by the time of the Treaty of Sevres, divisions

caused by competing interests had developed among the Allies: France resented Britain’s

domineering position; Italy

wanted to curb British and French domination and Greek expansionism; and the

French-Armenian alliance was faltering.

January 5, 2021

January 5, 1992 – Bosnian War- Bosnian Serbs secede from Bosnia-Herzegovina

Bosnian Serbs formed a majority in Bosnia’s

northern regions. On January 5, 1992,

Bosnian Serbs seceded from Bosnia-Herzegovina and established their own

country. Bosnian Croats, who also

comprised a sizable minority, had earlier (on November 18, 1991) seceded from

Bosnia-Herzegovina by declaring their own independence. Bosnia-Herzegovina, therefore, fragmented

into three republics, formed along ethnic lines.

Furthermore, in March 1991, Serbia and Croatia, two Yugoslav

constituent republics located on either side of Bosnia-Herzegovina, secretly

agreed to annex portions of Bosnia-Herzegovina that contained a majority

population of ethnic Serbians and ethnic Croatians. This agreement, later re-affirmed by Serbians

and Croatians in a second meeting in May 1992, was intended to avoid armed

conflict between them. By this time,

heightened tensions among the three ethnic groups were leading to open

hostilities.

Mediators from Britain

and Portugal

made a final attempt to avert war, eventually succeeding in convincing

Bosniaks, Bosnian Serbs, and Bosnian Croats to agree to share political power

in a decentralized government. Just ten

days later, however, the Bosnian government reversed its decision and rejected

the agreement after taking issue with some of its provisions.

Yugoslavia comprised six republics, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Serbia, Macedonia, and Macedonia, and two autonomous provinces, Kosovo and Vojvodina.

Yugoslavia comprised six republics, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Serbia, Macedonia, and Macedonia, and two autonomous provinces, Kosovo and Vojvodina.(Taken from Bosnian War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 1)

Background Bosnia-Herzegovina

has three main ethnic groups: Bosniaks (Bosnian Muslims), comprising 44% of the

population, Bosnian Serbs, with 32%, and Bosnian Croats, with 17%. Slovenia

and Croatia

declared their independences in June 1991.

On October 15, 1991, the Bosnian parliament declared the independence of

Bosnia-Herzegovina, with Bosnian Serb delegates boycotting the session in

protest. Then acting on a request from

both the Bosnian parliament and the Bosnian Serb leadership, a European

Economic Community arbitration commission gave its opinion, on January 11,

1992, that Bosnia-Herzegovina’s independence cannot be recognized, since no

referendum on independence had taken place.

Bosnian Serbs formed a majority in Bosnia’s

northern regions. On January 5, 1992,

Bosnian Serbs seceded from Bosnia-Herzegovina and established their own

country. Bosnian Croats, who also

comprised a sizable minority, had earlier (on November 18, 1991) seceded from

Bosnia-Herzegovina by declaring their own independence. Bosnia-Herzegovina, therefore, fragmented

into three republics, formed along ethnic lines.

Furthermore, in March 1991, Serbia and Croatia, two Yugoslav

constituent republics located on either side of Bosnia-Herzegovina, secretly

agreed to annex portions of Bosnia-Herzegovina that contained a majority

population of ethnic Serbians and ethnic Croatians. This agreement, later re-affirmed by Serbians

and Croatians in a second meeting in May 1992, was intended to avoid armed

conflict between them. By this time,

heightened tensions among the three ethnic groups were leading to open

hostilities.

Mediators from Britain

and Portugal

made a final attempt to avert war, eventually succeeding in convincing

Bosniaks, Bosnian Serbs, and Bosnian Croats to agree to share political power

in a decentralized government. Just ten

days later, however, the Bosnian government reversed its decision and rejected

the agreement after taking issue with some of its provisions.

War At any rate,

by March 1992, fighting had already broken out when Bosnian Serb forces

attacked Bosniak villages in eastern Bosnia. Of the three sides, Bosnian Serbs were the

most powerful early in the war, as they were backed by the Yugoslav Army. At their peak, Bosnian Serbs had 150,000

soldiers, 700 tanks, 700 armored personnel carriers, 3,000 artillery pieces,

and several aircraft. Many Serbian

militias also joined the Bosnian Serb regular forces.

Bosnian Croats, with the support of Croatia, had

150,000 soldiers and 300 tanks. Bosniaks

were at a great disadvantage, however, as they were unprepared for war. Although much of Yugoslavia’s war arsenal was

stockpiled in Bosnia-Herzegovina, the weapons were held by the Yugoslav Army

(which became the Bosnian Serbs’ main fighting force in the early stages of the

war). A United Nations (UN) arms embargo

on Yugoslavia

was devastating to Bosniaks, as they were prohibited from purchasing weapons

from foreign sources.

In March and April 1992, the Yugoslav Army and Bosnian Serb

forces launched large-scale operations in eastern and northwest

Bosnia-Herzegovina. These offensives

were so powerful that large sections of Bosniak and Bosnian Croat territories

were captured and came under Bosnian Serb control. By the end of 1992, Bosnian Serbs controlled

70% of Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Then under a UN-imposed resolution, the Yugoslav Army was

ordered to leave Bosnia-Herzegovina.

However, the Yugoslav Army’s withdrawal did not affect seriously the

Bosnian Serbs’ military capability, as a great majority of the Yugoslav

soldiers in Bosnia-Herzegovina were ethnic Serbs. These soldiers simply joined

the ranks of the Bosnian Serb forces and continued fighting, using the same

weapons and ammunitions left over by the departing Yugoslav Army.

In mid-1992, a UN force arrived in Bosnia-Herzegovina that

was tasked to protect civilians and refugees and to provide humanitarian

aid. Fighting between Bosniaks and

Bosnian Croats occurred in Herzegovina

(the southern regions) and central Bosnia, mostly in areas where

Bosnian Muslims formed a civilian majority.

Bosnian Croat forces held the initiative, conducting offensives in Novi

Travnik and Prozor. Intense artillery

shelling reduced Gornji Vakuf to rubble; surrounding Bosniak villages also were

taken, resulting in many civilian casualties.

In May 1992, the Lasva

Valley came under attack

from the Bosnian Croat forces who, for 11 months, subjected the region to

intense artillery shelling and ground attacks that claimed the lives of 2,000

mostly civilian casualties. The city of Mostar, divided into

Muslim and Croat sectors, was the scene of bitter fighting, heavy artillery

bombardment, and widespread destruction that resulted in thousands of civilian

deaths. Numerous atrocities were

committed in Mostar.