Daniel Orr's Blog, page 59

June 16, 2021

June 16, 1940 – World War II: Marshal Henri Philippe Petain becomes Chief of State of Vichy France

On July 10, 1940, the French governmentformed a new polity called the “FrenchState” (French: État français), which dissolved the French Third Republic, and was led by WorldWar I hero Marshall Henri Philippe Petain as Chief of State.

The “FrenchState” had its capital at Vichy, some 220 miles south of Paris,and was commonly known as “Vichy France”. Officially, VichyFrance retained sovereigntyover all France,but in reality, it exercised little authority in the occupied zones. Vichy France did have full administrativepower in zone libre, and in theongoing war, it maintained a policy of neutrality (e.g. it did not join theAxis), and was internationally recognized, and maintained diplomatic relationswith the United States, Canada, the Soviet Union, even Britain, and manyneutral countries.

(Taken from Battle of France – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Europe – Vol. 6)

The Vichygovernment imposed authoritarian rule, with Petain holding broad powers, whichwas a full turn-around and rejection of the liberalism and democratic ideals ofthe French Third Republic. Using Révolutionnationale (“National Revolution”) as its official ideology, the Petainregime turned inward-looking (la France seule, or “France alone”), was deeplyconservative and traditionalist, and rejected liberal and modernist ideas. Traditional culture and religion werepromoted as the means for the regeneration of France. The separation of Church and State wasabolished, with Catholics playing a major role in affairs, the French ThirdRepublic was reviled as morally decadent and causing France’s military defeat,and anti-Semitism and xenophobia predominated, with Jews and other“undesirables”, including immigrants, gypsies, and homosexuals beingpersecuted. Communists and left-wingers,and other radicals were included in this category following the German invasionof the Soviet Union in June 1941. Xenophobia was particularly directed against Britain, with Petain and other leadersexpressing strong antipathy with the British, calling them France’s “hereditary” and lastingenemy.

The Vichyregime was challenged by General Charles de Gaulle, who in June 1940 in Britain,formed a government-in-exile called Free France, and an army, the Free FrenchForces. De Gaulle criticized Vichy Franceas illegitimate, that it had usurped power from the French Third Republic, and that it wasa puppet state of Nazi Germany. In a BBCbroadcast on June 18, 1940 (the so-called “Appeal of 18 June”; French: Appel du 18 juin), he called on theFrench people to reject the Vichyregime and resist the German occupiers. Initially, de Gaulle received littlesupport in France and amongexpatriate French, who regarded the Petain regime as being the constitutionallylegitimate authority for France.

Despite the armistice agreement’sstipulation that deactivated the French naval forces, the British governmentfeared that the French fleet would be seized by the Germans who then would useit to invade Britain. Thus, on July 3, 1940, British ships attackedthe French fleet at Mers-el-Kebir (in Algeria),sinking or damaging several French ships, while the French squadron at Alexandria (in Egypt) allowed itself to beinterned by the British fleet.

By October 1940, the Petain regime hadbegan to actively collaborate in implementing the Nazi government’sAnti-Semitism laws. Using information ofthe poll registers on the Jewish population that earlier had been collected bythe French police, French authorities and the Gestapo (German secret police),working together or separately, conducted raids where thousands of Jews (aswell as other “undesirables”) were rounded up and confined in internment campsfor eventual transport to concentration and extermination camps in EasternEurope; many concentration camps also were set up in France. Of the 330,000 Jews in France, some 77,000 perished in theHolocaust, a death rate of 25%.

As the armistice agreement alsorequired Franceto pay the cost of the German occupation, the French became dependent on andsubservient to German impositions. French farm production and resources were seized by the Germans,resulting in the deterioration of the French economy and causing severehardships to the French people, who suffered food and fuel shortages orrationing, curfew, and restricted civil liberties.

The Battle of France resulted in some1.5 million French soldiers becoming German prisoners of war. To prevent Vichy France from re-mobilizingthese troops, German authorities kept these French soldiers in labor camps inGermany and France, although some 500,000 were later released at various times,and the remaining one million freed by the Allies at the end of World War II.

By 1941, a French resistance movementcomprising many small groups had emerged, with its memberships increased by theinflux of communists following the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, and forced work evaders following theimplementation of Service du TravailObligatoire (“Obligatory Work Service”) in February 1943. The French resistance soon also made contactwith de Gaulle’s government-in-exile, the British Special Operations Executive(SOE) and the U.S. Office of Strategic Services (OSS), which sent supplies andagents. The resistance conductedsabotage operations against military-vital targets, provided the Allies withintelligence information, and sheltered and helped escape downed Allied airmen,Jews, and other elements targeted by German and Vichy authorities.

In November 1942, following the Alliedinvasion of western North Africa, the German military also occupied theterritory of Vichy France in order to safeguard thesouthern flank. The Italian occupationzone also was expanded. While France ostensibly continued its sovereignty overits territories, in reality, German military authority came into forcethroughout France, and the Vichy government exercisedlittle power. The German occupation of Vichy Francealso ended the latter’s diplomatic relations with the United States, Canada, and other Allies, and alsowith many neutral states.

June 15, 2021

June 15, 1972 – Sand War: Morocco and Algeria sign the Treaty of Ifrane

Morocco and Algeriare-established diplomatic relations following an Arab League-sponsored summitheld in Cairo, Egypt in January 1964. In border talks that took place also in 1964,the two sides agreed that the disputed areas would remain with Algeria (in effect, affirming Algeria’s succession to the colonial-eraborders) in exchange for Moroccoand Algeriasharing the wealth of a jointly established iron-ore industry in the Tindoufregion. In 1969, a treaty of solidarityand cooperation signed at Ifrane led to improved relations, which in turn ledto an agreement signed in Tlemcen, Algeria in 1970that was aimed at establishing a definitive border. On June 15, 1972, the Algeria-Morocco borderagreement was released, but which was ratified by Morocco only in May 1989.

In 1976, tensions flaredagain (that almost led to war) between the two countries over Western Sahara, arecently decolonized Spanish possession located south of Morocco and west of Algeria (see Western Sahara War, separate article).

(Taken from Sand War – Wars of the 20th Century –Vol. 4)

Background In1956, Morocco regained itsindependence, ending 44 years as a protectorate under France and Spain. Six years later, in 1962, Algeria, Morocco’seastern neighbor, also achieved statehood from France after prevailing in itscolonial war of independence. Nowsovereign states, Moroccoand Algeriafaced a crisis: a contentious border issue.

The origin of the border crisisgoes back to more than a century earlier, to 1830, when France invaded and captured Algiers, ending Ottoman rule and (ultimately)influence in the region. The Frenchgained full control during the rest of the 19th century and into the20th century, gradually expanded south, east, and west and addedmore territory into what ultimately would form French Algeria.

In 1842, the French colonialgovernment tried to negotiate a common border with the Sultanate of Morocco,its western neighbor and an independent political entity. The Moroccan sultan demurred, however. Then in 1844, war broke out between France and Morocco because of the Moroccansultan’s support for an Algerian uprising against French rule. In this war, known as the FirstFranco-Moroccan War, the French decisively defeated the Moroccans and in theTreaty of Tangiers, signed in October 1844 and later the Treaty of LallaMaghnia, signed in March 1845, the two sides ended the war. Furthermore, the latter treaty wassignificant in that Franceand Moroccoagreed to a partial demarcation of their border, i.e. from the coast to TenietSassi, a distance of 100 miles. Nophysical demarcation was carried out further south, which now formed part ofthe barren, thinly populated Sahara Desert; instead, the two sides agreed that the areasinhabited by tribes that traditionally recognized the Moroccan sultan’ssovereignty formed part of Morocco,while those tribes and their lands associated under the former Ottoman rule in Algiers belonged to French Algeria. Some of these tribes, however, were nomadicor had undefined territorial ranges, rendering border demarcation impossible tocarry out. French expansion deep intothe Sahara also brought regions historically associated with Moroccan influenceor sovereignty (e.g. Touat, Gourara, and Tidikelt, which are now located inpresent-day central Algeria)into the realm of French Algeria.

Countries in North Africa

Countries in North AfricaMeanwhile, as a result of France’s colonial expansion into western Africa,in April 1904, Britain and France signed the Entente Cordiale, an agreementwhere the British agreed to cede control of Moroccoto the French (in exchange for the French recognizing British sovereignty over Egypt). The agreement also recognized Spain’s historical sphere of influence over Morocco. In October of that year, France and Spainagreed on a delineation of zones over Moroccowhich finally resulted in the establishment of a French protectorate over Moroccoin March 1912. Then in November 1912, France handed areas of Morocco to Spain,with the latter establishing a protectorate over these areas: a northern zonearound Ceuta and Melilla,and a southern zone centered at Cape Juby (Figure 12). As a protectorate, Morocco ceded control of itsforeign affairs initiatives but remained a sovereign state according tointernational law.

In 1912, shortly afterestablishing a protectorate over Morocco, France undertook a demarcation of itsAlgerian colony for administration purposes, the land survey leading to theestablishment of the Varnier Line (French: Ligne Varnier, named after MauriceVarnier, French High Commissioner for Eastern Morocco) that extended the“border” from Teniet Sassi south to Figueg (which remained with Morocco),turned west to include Colomb-Bechar, Kenadza, and Abdla as part of FrenchAlgeria, and then turned south to an undelineated “uninhabited desert”. In the 1920s, French authorities held anumber of conferences to delineate the limits of protectorate Morocco and colonial Algeria, but these all failed toyield definitive results. In 1929, theFrench published the Confinsalgéro-marocains, which delineatedshared security and administrative jurisdictions between Morocco and Algeria along designatedoperational limits (Limite opérationnelle). In 1934, France carried out another demarcation surveyfor administration purposes that included the Draa Valley,producing the Trinquet Line (French: Ligne Trinquet).

France intended some of these surveys to be used foradministrative purposes and others to establish territorial limits, furtheringthe confusion; moreover, the latter maps that were released ran contradictoryto earlier maps and sometimes went against other international treaties. However, the French established control inareas inside the survey lines, which ultimately became crucial in the borderdispute in the post-independence period.

Shortly after World War IIended in 1945, a wave of nationalism swept across the colonized peoples ofAfrica and Asia. In Morocco,an independence movement led by the ultra-nationalist Istiqlal Party gainedwide popular support for self-determination and to end France’s protectorate over Morocco. In April 1956, Mohammed V, the Moroccansultan, succeeded in convincing Franceand Spainto end their protectorates, thus regaining full independence for hiscountry. Now independent, Moroccoestablished a constitutional monarchy, with broad powers vested on the sultan(in 1957, Mohammed V assumed the title of king). The monarchy was conservative, right-wing,and anti-communist, and was aligned with France,the United States,and the Western powers in the Cold War.

Meanwhile in Algeria, France was fighting a bitter war ofindependence against Algerian nationalists led by the National Liberation Front(FLN; French: Frontde Libération Nationale). In 1952, when Morocco’sstruggle for complete self-determination was underway, France once more redrew theadministrative line, declaring that the territory extending from Colomb-Becharto Tindouf was part of French Algeria. The French particularly were interested in Tindouf, where commercialquantities of iron ore were discovered recently and the prospect of finding oiland natural gas reserves were luring French investors. In 1956, however, when the Algerianindependence war was raging and the now independent Moroccowas aligned with France and the West, the French government offered Moroccansultan Hassan II the territorial transfer of Colomb-Bechar and Tindouf to Morocco in exchange for the Moroccan government’sending its support for Algerian nationalist guerillas who operated out of Morocco. The Moroccan monarch turned down the offer,however, saying that he would deal with the Algerian nationalists directly.

In July 1961, the Moroccangovernment and the Algerian revolutionary government-in-exile (called the Gouvemement Provisoire de la République

Algérienne, or GPRA, based in Cairo Egypt)did reach a tentative agreement: Moroccowould respect independent Algeria’sterritorial integrity, but the border would be negotiated later throughbilateral talks. The following year,1962, Algeriagained its independence. In a briefpolitical power struggle that followed, the moderate GPRA was pushed aside anda hard-line regime under President Ahmed Ben Bella was established.

June 14, 2021

June 14, 1940 – World War II: The Soviet Union issues an ultimatum to Lithuania

On June 14, 1940, the Soviet government issued an ultimatumto Lithuaniato allow Soviet troops to enter Lithuanian territory and to form a newpro-Soviet government. Nine months earlier in October 1939, the two countrieshad signed the Soviet–Lithuanian Mutual Assistance Treaty that allowed thestationing of 20,000 Soviet troops in a number of bases inside Lithuania.

With the presence of Soviet forces already in the country,on June 15, the Lithuanian government acquiesced to the ultimatum and ended thecountry’s independence. The Soviets took control of the country, installed apuppet regime, and held sham elections to the legislature. The new legislatureproclaimed the establishment of the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic andpetitioned to be admitted into the Soviet Union.In August 1940, the Soviet government accepted the petition and admitted Lithuania into the Soviet Union.

The Soviet Union signed similar mutual assistance agreementswith the other Baltic States, Estonia(September 28, 1939) and Latvia(October 5, 1939) that allowed Soviet forces to occupy specific bases in thetwo countries. Also in June 1940, Soviet forces occupied Estonia and Latvia;after socialist governments came to power in Soviet-controlled elections heldin July 1940, Estonia and Latvia were similarly incorporated into the Soviet Union in August 1940.

June 13, 2021

June 13, 1982 – Falklands War: Battles of Tumbledown and Wireless Ridge

With their flank secure, the main British force at San Carlos Bayset out for Teal Inlet, located 40 kilometers northwest from Port Stanley. In early June1982, a brigade of 3,000 British soldiers also was landed at Bluff Cove andFitzroy, 30 kilometers east from Port Stanley. The Argentineans tried to stop the landings,sending planes that attacked and hit two British transport ships at PortPleasant, near Fitzroy. Britishcasualties from these attacks were 56 killed and 150 wounded. The British, however, successfully securedand completed the landing. By then, thetotal number of British ground troops in the Falklands were 10,000 soldiers,which set out for the re-conquest of Port Stanley.

The Argentinean forces defending the capital alsoconsisted of about 10,000 troops, mostly new conscripts but reinforced with thearrival of more experienced soldiers. TheArgentineans set up the defense of the capital in and around two rings of hillson the western approach outside the city.

On May 31, 1982, British forces captured Mount Kent. The attack on the main Argentine positionswas now set. On June 11, British artilleryunits shelled the first, outer ring of hills. Then under cover of darkness, British ground troops fought their way upthe heights. Before dawn of thefollowing day, June 12, Mount Harriet, Mount Two Sisters, and strongly defended Mount Longdon,had been captured by the British.

On the night of June 13, 1982 British forcesattacked the second ring of hills, MountTumbleweed, Mount William,and Wireless Ridge. By morning of thefollowing day, Argentine forces had abandoned their positions in the heightsand were making a full retreat toward Port Stanley.

The British then advanced and surrounded Port Stanley from the land and sea, forcing the Argentineancommander of the city to ask for a ceasefire, which was granted. Soon thereafter, the British regained controlof the islands and allowed the Argentinean forces to leave. On June 20, the Argentinean presence in Southern Thule ended with the arrival of a British navalforce that forced the surrender of the Argentine garrison.

Aftermath The war had dramatic, contrastingrepercussions in Britain andArgentina. In Britain where elections werescheduled for the following year, Prime Minister Thatcher’s government trailedbadly in the polls and seemed headed for defeat. However, the war, and certainly its outcome,generated a surge of nationalism that swept the incumbents to a decisivevictory in the elections.

In Argentina,the military government also received massive public support when the ArgentineArmy gained control of the Falklands early inthe war. However, after the Argentineforces were defeated and expelled from the islands, protests and riots brokeout in Buenos Aires. General Galtieri resigned and the militarygovernment collapsed. Argentina then began its transitionback to democracy. General electionswere held in October 1983, which led to a civilian government takingoffice. Despite its defeat in the war,to this day, Argentinacontinues to claim ownership of the Falkland Islands.

The war took place during the Cold War period andwas viewed by communist countries as a conflict between two “capitalist”countries. Much of the world followedthe war with great interest. WesternEuropean countries diplomatically supported Britain,while the Non-Aligned Movement and most Latin American countries backed Argentina. At the time of the war, Argentina and Chile were locked in a borderdispute, and the two sides deployed troops in their border in anticipation foran invasion by the other side. Chile officially was neutral in the Falklands Warbut provided intelligence information to the British and tied down Argentineforces.

The United States,the region’s most dominant force, endeavored to stay neutral as it was an allyof both countries, i.e. with Britainin the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and with Argentina in their common war against communismin South America. The U.S. government, led by PresidentRonald Reagan, tried to bring the two sides to negotiate a peacefulsettlement. When the effort failed, the United Statesleaned on the side of the British, providing them with material andtechnological support during the war.

(Taken from Falklands War – Wars of the 20th Century –Vol. 3)

Background In early 1982, Argentina’s ruling military junta,led by General Leopoldo Galtieri, was facing a crisis ofconfidence. Government corruption, humanrights violations, and an economic recession had turned initial public supportfor the country’s military regime into widespread opposition. The pro-U.S. junta had come to power througha coup in 1976, and had crushed a leftist insurgency in the “Dirty War” byusing conventional warfare, as well as “dirty” methods, including summaryexecutions and forced disappearances. Asreports of military atrocities became known, the international communityexerted pressure on General Galtieri to implement reforms.

In its desire to regain the Argentinean people’smoral support and to continue in power, the military government conceived of aplan to invade the Falkland Islands, a British territorylocated about 700 kilometers east of the Argentine mainland. Argentinahad a long-standing historical claim to the Falklands,which generated nationalistic sentiment among Argentineans. The Argentine government was determined toexploit that sentiment. Furthermore,after weighing its chances for success, the junta concluded that the Britishgovernment would not likely take action to protect the Falklands, as theislands were small, barren, and too distant, being located three-quarters downthe globe from Britain.

The Argentineans’ reasoning was not withoutmerit. Britainunder current Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher was experiencing an economic recession, and in1981, had made military cutbacks that would have seen the withdrawal from theFalklands of the HMS Endurance, an ice patrol vessel and the British Navy’sonly permanent ship in the southern Atlantic Ocean. Furthermore, Britainhad not resisted when in 1976, Argentinean forces occupied the uninhabitedSouthern Thule, a group of smallislands that forms a part of the British-owned South Sandwich Archipelago, located 1,500 kilometers east of the Falkland Islands.

In 1982, Argentina and Britain went to war for possession of the Falkland Islands and South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands

In the sixteenth century, the Falkland Islands first came to European attention when they were signed byPortuguese ships. For three and a halfcenturies thereafter, the islands became settled and controlled at varioustimes by France, Spain, Britain,the United States, and Argentina. In 1833, Britaingained uninterrupted control of the islands, establishing a permanent presencethere with settlers coming mainly from Walesand Scotland.

In 1816, Argentinagained its independence and, advancing its claim to being the successor stateof the former Spanish Argentinean colony that had included “Islas Malvinas” (Argentina’s name for the Falkland Islands), theArgentinean government declared that the islands were part of Argentina’s territory. Argentinaalso challenged Britain’saccount of the events of 1833, stating that the British Navy gained control ofthe islands by expelling the Argentinean civilian authority and residentsalready present in the Falklands. Over time, Argentineans perceived the Britishcontrol of the Falklands as a misplacedvestige of the colonial past, producing successive generations of Argentineansinstilled with anti-imperialist sentiments. For much of the twentieth century, however, Britainand Argentina maintained anormal, even a healthy, relationship, although the Falklandsissue remained a thorn on both sides.

After World War II, Britain pursued a policy of decolonization thatsaw it end colonial rule in its vast territories in Asia and Africa,and the emergence of many new countries in their places. With regards to the Falklands, under UnitedNations (UN) encouragement, Britainand Argentinamet a number of times to decide the future of the islands. Nothing substantial emerged on the issue ofsovereignty, but the two sides agreed on a number of commercial ventures,including establishing air and sea links between the islands and theArgentinean mainland, and for Argentinean power firms to supply energy to theislands. Subsequently, Falklanders(Falkland residents) made it known to Britain that they wished to remainunder British rule. As a result, Britain reversed its policy of decolonization inthe Falklands and promised to respect thewishes of the Falklanders.

June 12, 2021

June 12, 1999 – Kosovo War: UN peacekeepers enter Kosovo

On June 12, 1999 a NATO-led United Nations peacekeepingforce (called KFor for Kosovo Force) entered war-torn Kosovo. KFor was tasked by the UN Security Council tomaintain the peace as a result of the Kosovo War. By this time, Kosovo wasfacing a serious humanitarian crisis, with nearly one million civiliansdisplaced by the fighting.

The Kosovo War (February 1998-June 1999) was fought betweenthe Yugoslav Army and Albanian Serb militias against the Kosovo Liberation Army(KLA), a Kosovo Albanian rebel group. Subsequently, the KLA would gain airsupport from NATO and ground support from the Albanian Army.

At the outbreak of the war, Kosovo was an autonomous regionof Serbia.It had two main ethnic groups: the majority Albanians (comprising 77% of thepopulation) who desired greater autonomy from Serbia,and Kosovo Serbs (15% of the population) who wanted more political integrationwith Serbia.

(Taken from Kosovo War – Wars of the 20th Century –Vol. 1)

War In April1996, the KLA, an extremist Albanian militia that sought to gain Kosovo’sindependence by force, launched attacks against Serbian police units acrossKosovo. By March 1988, as the KLA hadgrown in strength and were intensifying its armed operations, the Yugoslav Armyentered Kosovo. Fighting occurred fromMarch to September, concentrated mostly in central-south Kosovo. The Yugoslav Army was far superior instrength, forcing the KLA to resort to guerilla tactics, such as ambushing armyand security patrols, and raiding isolated military outposts. Through a tactical war of attrition, the KLAgained control of Decani, Malisevo, Orahovac, Drenica Valley,and northwest Pristina.

In September 1998, the Yugoslav Army and Kosovo Serb forceslaunched offensive operations in northern and central Kosovo, driving away theKLA from many areas. These offensivesalso turned 200,000 civilians into refugees, prompting the United Nations tocall for a ceasefire and an end to the conflict.

With the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)threatening to intervene, Yugoslaviaagreed to a ceasefire in October 1998. Amulti-national observer team then arrived in Kosovo to monitor theceasefire. Fighting broke out inDecember 1998, however, which escalated in intensity early the next year,forcing the multi-national observer team to leave Kosovo in March 1999.

NATO became increasingly involved in the war – especiallyafter the discovery of the bodies of 45 executed Kosovo Albanian farmers – anddecided that direct military intervention was needed to end the war. In March 1999, NATO presented to Yugoslaviaa proposal to station 30,000 NATO soldiers in Kosovo to monitor and maintainpeace. Furthermore, the NATO force wasto have free, unrestricted passage across Yugoslavia. The Yugoslav government vehemently rejectedthe UN proposal, calling it a violation of Yugoslavia’s territorialsovereignty. In turn, Yugoslavia offered its own peaceproposal, which was also rejected by NATO. The diplomatic impasse prompted NATO to begin military action against Yugoslavia.

On March 23, 1999, using over one thousand planes, NATObegan launching massive air strikes against military installations andfacilities in Yugoslavia. Later, NATO targeted Yugoslav Army units aswell. NATO planes also attacked publicinfrastructures such as roads, railways, bridges, telecommunications systems,power stations, schools, and hospitals. Many unintended targets were hit as well, such as a convoy of KosovoAlbanian refugees, a Kosovo prison, a Serbian television facility, and theChinese Embassy in Belgrade. The NATO air attacks against non-militarytargets drew widespread international condemnation.

In retaliation for the air strikes, the Yugoslav Army andKosovo Serb forces expelled Kosovo Albanians from their homes. Within a few weeks, some 750,000 Kosovo Albanianshad been forced to flee to neighboring Albania,Macedonia, and Montenegro.

On June 3, the government of Yugoslavia,persuaded by Russia,yielded to strong international pressure and agreed to accept NATO’s peaceproposal. Thereafter, Yugoslav forceswithdrew from Kosovo. NATO then endedits air strikes against Yugoslaviaand sent a peacekeeping force, under a UN mandate, to enter Kosovo. Russia,which was Yugoslavia’sstaunchest supporter during the war, also deployed its own peacekeepers in Kosovoto serve as a foil against the NATO troops. NATO and Russian peacekeepers coordinated their actions, however, tosecure peace in Kosovo while avoiding unwanted confrontations between them.

About 13,000 persons died in the Kosovo War. Over one million civilians fled the fightingand became refuges, although most eventually returned to their homes after thewar. Perhaps as many as 200,000 ethnicSerbs fled Kosovo in the years after the war. Yugoslavian and Kosovo Serbian political and military leaders, includingKLA members, have been charged with war crimes.

In February 2008, Kosovo Albanians declared Kosovo anindependent country. Serbia rejected Kosovo’sindependence and has since maintained its claim to Kosovo as being an integralpart of Serbian territory. While the United States, United Kingdom, and other countriesrecognize Kosovo’s independence, many others do not. Russia,in particular, insists that any proposed solution must be acceptable to both Serbiaand Kosovo.

June 11, 2021

June 11, 1942 – World War II: The United States agrees to send Lend-Lease assistance to the Soviet Union

In terms of militaryproduction, the United States entry into the war (December 1941) was decisive,as the sheer manufacturing power and size of the U.S. industry came into playjust as the early protagonists were exhausting their resources in a war ofattrition. By 1944, the United Statesproduced 60% of the Allied war materials. So massive was American production that the U.S.military gave to the other Allies large amounts of weapons and hardware, in aprogram that began in March 1941 under Lend-Lease (officially called “An Act toPromote the Defense of the United States”). Under Lend-Lease,from a total war materials worth $50 billion ($706 billion in 2017 value), some$31 billion ($438 in 2017 value) went to Britain, $11 billion ($155 billion in2017 value) went to the Soviet Union, $3.2 billion ($45 billion in 2017 value)went to France, $1.6 billion ($23 billion in 2017 value) went to China, and$2.6 billion ($37 billion in 2017 value) went to other Allied countries. American support to the Soviet Union (whichbore the brunt of the European war, with Germany concentrating 80% of itsforces in the Eastern Front) comprised 400,000 transport vehicles, 12,000armored vehicles (including 7,000 tanks), 11,400 planes, and 1.75 million tonsof food. The British provided 7,000planes, while British-Canadian support consisted of 5,000 tanks. During the Cold War, official Soviet historiographyof World War II put Allied contribution at 4% of total Soviet production. Following the end of the Soviet Union in 1991when greater access to Soviet war archives became available, more recentresearch has placed U.S. contribution to the Soviet war effort at 15-25% toeven as high as 50% depending on the type of military hardware. Both Stalin and his successor, NikitaKhrushchev have acknowledged that Western Allied support were crucial to theSoviet victory in the war.

(Taken from The End of World War II in Europe – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Europe – Vol. 6)

Allied War ConferencesThe United States, Britain,and Soviet Union, the so-called “Big Three” Powers, met in two major war-timeconferences, at Tehran (November 28 – December1, 1944) and Yalta (February 4-11, 1945), and inthe immediate post-war period, at Potsdam(July 17-August 2, 1945). At the Tehran (Iran)Conference, the Big Three agreed to align military strategy. At the Yalta Conference (Yalta,Crimea, USSR)which was attended by U.S. President Roosevelt, British Prime MinisterChurchill, and Soviet leader Stalin, the Allies, now in an overwhelmingmilitary position, agreed on the disposition of post-war Germany and Europe. By then, Stalin was negotiating in a superiorposition, as his Red Army was only 40 miles (65 km) from Berlin. Stalin agreed to join the war in the Asia-Pacific against Japan, and becomea member of the United Nations (both requested by the United States), but inreturn persuaded Roosevelt and Churchill to allow the following: that theSoviet-Polish border be moved to the Curzon Line, that the Soviets gain theSouth Sakhalin and Kuril Islands from Japan, that the Port Arthur lease berestored to the Soviets, and that Mongolia (a Soviet satellite polity since1924) been detached from China.

Of major contention at Yaltawas the issue of Poland, as Roosevelt and Churchill wanted to return the Polishgovernment-in-exile (in London) to power, while Stalin insisted on installingthe pro-Soviet government already operating in recaptured Polish territories In fact, Poland formed only part of thelarger issue regarding the political future of Eastern Europe, where Stalinwanted to impose a Soviet sphere of influence to safeguard against anotherinvasion from the West, while Roosevelt and Churchill wanted democraticgovernments to be established there. Instead, the Big Three signed the “Declaration of Liberated Europe”,where they agreed that European nations must be allowed “to create democraticinstitutions of their own choice” and to “the earliest possible establishmentthrough free elections [of] governments responsive to the will of thepeople”. Free elections were to beconducted in Polandas well, and the Soviet-sponsored provisional government, while remainingpredominant, would be encouraged to include non-communists “on a broaddemocratic basis”.

In the Potsdam agreement, the“Big Three”, now led by U.S. President Harry Truman (succeedingRoosevelt), British Prime Minister Clement Atlee (succeeding Churchill),and Stalin reaffirmed previous agreements with regards to dealing with post-warGermany and the territorial changes demanded by Stalin. As well, Germany was required to pay warreparations, and ethnic Germans were to be expelled from the former Germanlands and forced to move to within the new German borders. As Soviet domination of Poland was now a fait accompli, the Western Alliesacquiesce to the authority of the pro-Soviet Polish government in that country.

II – AFTERMATH

Europe In May 1945, at thetime of Germany’s surrender,Europe was in ruins, with its infrastructuresand economies destroyed, and great political turmoil prevailing in much of thecontinent. The human toll wasstaggering, with the greatest fatalities suffered by the Soviet Union at 27million and Germanyat 5.3 million, as a result of direct combat, massacres, mass executions,famines and diseases, harsh prison conditions, slave labor, and otherfactors. The Allied strategic bombing ofGermany and occupied Europe destroyed millions of houses and residentialbuildings, forcing millions of civilians to become refugees. As well, towards the end of the war, some 4.5million ethnic Germans fled from Eastern Europe westward into Germany to escape the advancing RedArmy. Those who were caught up sufferedterrible fates, including some 1.9 million women being raped, including 30% ofwomen in Berlin, by Russian soldiers, with rape faring prominently in theirmeans to exact revenge for the invasion and destruction of their homeland. Several millions more ethnic Germans would beexpelled from Eastern Europe in the post-warperiod.

Germany Asstipulated in the Allied war agreements, the Polish Kresy region(188,000 km²) was annexed to the Soviet Union, and to compensate for thisloss, German territory east of the Oder-Neisse Line, which included Silesia,Neumark, and most of Pomerania (totaling 111,000 km²), was awarded toPoland. East Prussia also was detached from Germanyand divided between the Soviet Union and Poland. In total, Germany lost 25% of its pre-warterritory. The Sudetenland reverted to Czechoslovakia, as did Alsace-Lorraine to France. In 1947, the Saar region also was detachedfrom Germany and awarded to Franceas a protectorate. Following areferendum in 1955 where Saar residents rejected a proposal of independence forthe Saar, the region was incorporated into West Germany in January 1957. In April 1949, the Netherlands annexed a number ofsmall German areas near the German-Dutch border (totaling 69 sq km) as warreparation. In August 1963, these landswere returned to Germanyin exchange for monetary compensation.

The remainder of Germanterritory was then partitioned into four military occupation zones, one eachfor the Soviet Union, United States,Britain, and France[1].

The Allies freed thesurviving 11 million POWs and foreign slave workers (from the 12-15 milliontotal) in Germany, repatriating them back to their home countries: 5.2 millionto the Soviet Union 1.6 million to Poland, 1.5 million to France, 900,000 toItaly, and 300,000-400,000 each to Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, the Netherlands,Hungary, and Belgium.

The returning 1.7 millionSoviet POWs (which comprised the 30% survivors of the 5.7 million totalcaptured during the war), as well as the repatriated Soviet civilian slavelaborers, were suspected as traitors by the Soviet government, because ofStalin’s war-time “no surrender” decree. As a result, these Soviet repatriates were screened in “filtrationcamps” for possible collaboration with the Nazis, and 90% were later cleared,and 10% civilian and 20% ex-POWs were sent to “penal battalions”. Another 2% civilian and 10% ex-POWs (over200,000 soldiers) were sent to Gulag labor camps.

The Allies were determinedthat Germanyshould be prevented from starting another war. As stipulated in the Potsdam Agreement, the Allies dissolved the GermanArmed Forces (Wehrmacht) and banned Germany from producing weapons andwar-related commodities. Also of greatimportance to the Allies was the de-industrialization of Germany, particularly thedestruction of German heavy industry, including ship construction, machineproduction, and chemical plants, other war-related industries, which wasintended to eliminate German war-making capability. The Allies wanted to transform Germanyinto a semi-pastoral state by limiting its economy to agriculture and lightindustries. Consequently, a massivedismantling of German heavy industry took place, with hundreds of manufacturingplants destroyed or dismantled.

The dismantled industrialplants were claimed as war reparations and shipped to Allied countries, wherethey were re-assembled for production. The Western Allies eventually stopped the de-industrialization processwith the emerging new state of West Germany. In the Soviet sector, a much greater and longer disassembly and seizureof German industry occurred, both claimed as war reparations and to pay foroccupation cost. By 1949, nearly allindustries were in Soviet control to exploit, severely hindering reconstructionof the new Soviet-sponsored state of East Germany.

[1] This partition was meant to be temporary, but as post-war tensionsrose between the Western Allies and the Soviet Union, the occupation zonestransitioned into political entities, with West Germany (officially: FederalRepublic of Germany) created in May 1949 from the American, British, and Frenchsectors; and East Germany (officially: German Democratic Republic) emerging inresponse in October 1949 from the Soviet sector.

June 10, 2021

June 10, 1935 – Chaco War: Bolivia and Paraguay sign a truce

On June 10, 1935, in a truce mediated by the Argentineangovernment, Paraguay and Bolivia agreedto end the Chaco War.

Background Duringthe 1930s, Paraguay and Bolivia went to war for possession of the North Chaco, a dry, forbidding expanse of scrub andforest that lay between the two countries (Map 27). The North Chaco forms a part of the largerGran Chaco Plains, a vast region that extends into northern Argentina, western Paraguay,eastern Bolivia, and a smallsection in western Brazil.

During the colonial era, the Gran Chaco Plains wasadministered by the Spanish government as a separate territory. In the early 1800s, the Gran Chaco Plainsbecame disputed territory when the South American countries surrounding itgained their independences. Thedelineation of the borders around the Gran Chaco Plains was not pursuedactively, however, because of the region’s harsh climate and the mistakenbelief that it contained few natural resources.

(Taken from Chaco War – Wars of the 20th Century –Vol. 1)

Through conquest from wars later in the 1800s, many areas ofthe Gran Chaco Plains were annexed by the victorious countries. Eventually, what remained undecided was theNorth Chaco, the region straddling Paraguayand Bolivia and located westof the Paraguay River and north of the Pilcomayo River.

War Fightingbroke out in June 1932 with the Paraguayan forces soon taking the initiative.But by March 1935, their offensive had sputtered. Thereafter, the ParaguayanArmy realized that while it had achieved its military objectives in the NorthChaco, it could not go any further into Bolivia without incurring heavylosses.

While some politicians on both sides demanded for thecontinuation of the war, the governments of Paraguayand Boliviawere alarmed that the huge human and economic tolls were bringing theircountries to ruin. War casualties hadreached 100,000 dead, with nearly 60% of that figure suffered by Bolivia. On June 10, 1935, in a truce mediated by theArgentinean government, Paraguayand Boliviaagreed to end the war.

Aftermath Theterritorial issue of the North Chaco wasbrought before an arbitration panel consisting of members from South Americancountries. In its decision, thearbitration panel awarded 75% of the North Chaco to Paraguay,and the rest (25%) to Bolivia. The panel’s decision also stipulated that Paraguay must grant Boliviaaccess to the Paraguay River, as well as to specified ports and rail facilitiesinside Paraguay.

June 9, 2021

June 9, 1967 – Six-Day War: Israel captures the Golan Heights from Syria

The Six-Day War was a short conflict fought in June 1967pitting Israel against theArab countries of Egypt, Syria, and Jordan. Mounting tensions andoccasional fighting had taken place in the period leading up to the war. On May18, the Egyptian government expelled the UN peacekeepers in the Sinai, and sentarmy units to the Egypt-Israel border, thereby militarizing the Sinai Peninsula. Afew days later, Egyptprevented Israelcommercial vessels from entering the Straits of Tiran. Israel viewed the blockade as aprovocation for war. On May 28, Israelprepared for war with a call up of reservists. Three days later, foreign embassies in Israel instructed their citizens toleave in anticipation for war. On June1, Israelfinalized its war plans. Then in ameeting held on June 4, Israel’scivilian and military leaders set the date for war for the following day, June5.

The Six-Day War was fought in three sectors: Sinai Peninsulaand Gaza, West Bank, and the Golan Heights.

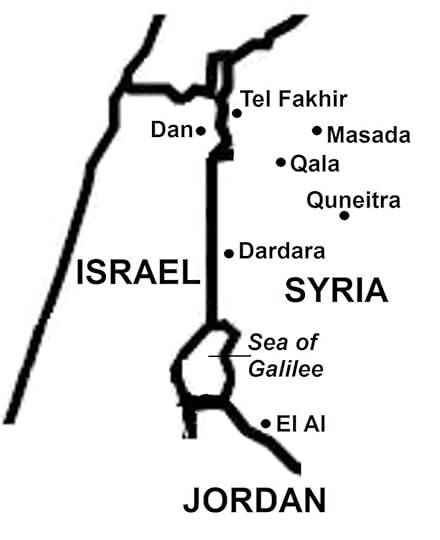

Battle for the Golan Heights On June 5, Syria opened the northern sector of the war withits artillery batteries in the Golan Heightsshelling Israeli settlements in the plains below. Syrian planes also attacked areas of Upper Galilee. Onthe night of June 5, Israeli planes attacked Syrian airbases and destroyednearly half of all Syrian planes on the ground. The Syrian Air Force then moved its remaining planes farther away fromthe battle zones and ceased to be a factor for the rest of the war. As in the other theaters of the war, Israelgained air domination on the Syrian front, which again proved decisive.

During the early stages of the war, Israel’s forces were concentrated in theEgyptian and Jordanian sectors; therefore, Israel’s strategy in the north wasmerely to hold on and defend territory with undermanned forces. Syrian offensives, however, generally werelimited in strength and effectiveness. On June 6, a Syrian infantry and armored attack on Tel Dan, Dan, andShe’ar Yashov was turned back by Israel air strikes and fierce localresistance. A large Syrian offensiveinto Galilee was aborted because of logisticaland communications problems.

(Taken from Six-Day War – Wars of the 20th Century –Vol. 2)

On June 9, as the victory over Egyptand Jordan became apparent, Israel’s military leaders approved the offensiveagainst Syrian forces on the Golan Heights. Earlier, Syriaand Israel had accepted aUnited Nations Security Council resolution for a ceasefire, but Israeliauthorities decided to attack in order to eliminate the Syrian threat,particularly the artillery batteries, which had caused so much trouble to Israel’snorthern communities and was a major cause for the war. The operation was feared to be costly,however, as the Golan Heights, at its steepest points in its northern section,was situated on a rocky escarpment 500 meters from Israel’s plains below. Syrian defenses on the Golan Heights consisted of 40,000 troops and 250 tanks, and a series ofstrong fortifications of concrete bunkers, machine gun nests, pillboxes, andartillery emplacements. The forwardapproaches were open fields laid with thousands of land mines.

On the morning of June 9, Israeli planes attacked Syrianpositions on the Golan Heights. The air strikes continued for four hours, butfailed to cause significant damage to the defenses. Towards the noon hour, Israel ground units went on theoffensive. The Israel Army High Commanddecided to attack on the Golan Height’s northern section, which was thesteepest – but also the least defended, based on reconnaissanceinformation. After sappers cleared landmines, armored bulldozers moved forward to create a road. Following behind the construction crews andequipment were the battle tanks and other armored units. The Israeli Army’s objective was thestrategically located Qala, whose capture would allow the Israelis access tothe Masada/Quneitra Road,the main thoroughfare through the Golan Heights. Qala’s capture also would permit the Israelisto attack other Syrian positions from the rear.

The Israeli advance was met with heavy fire from Syriandefenses atop the escarpment, which knocked out many bulldozers and tanks. Some Israeli units also lost their way andended up in the direction of Za’ura. After five hours and sustaining considerable losses, the Israelisreached the top of the heights, helped considerably by cover from Israeliplanes. To protect the flank of the Qalaoffensive, another infantry and armored thrust was made further north to attack13 Syrian positions at Tel Fakhir. Afterseven hours and intense fighting that involved hand-to-hand combat, the Israelisoverran Syrian positions, with considerable losses on both sides.

The Israelis also launched operations in the southern Golan Heights, whose slopes were more gradual than in thenorthern section. After several hours offighting, the Syrian southern defenses at Dardara and Tel Hilal collapsed. By the evening of June 9, Israeli forces werepouring in across the length of the Golan Heights. Considerable numbers of Israelireinforcements arrived from the Egyptian and Jordanian sectors, creatingmassive traffic congestions in Israeli streets as soldiers and war equipmentwere being moved to northern Israel. Fighting continued throughout the night asthe Israelis attempted to extend their lines.

Syrian fortifications throughout most of the Golan Heights remained intact despite the Israelibreakthrough. On the morning of June 10,however, the Syrian government mistakenly announced that Quneitra, where theSyrian regional military headquarters was located, had fallen to the Israelis. Panic broke out in the Syrian defenses in theGolan Heights as soldiers and officers abandoned their positions and fled to Damascus, Syria’scapital. As Israeli forces entered andoccupied Quneitra and other Syrian positions in the Golan Heights, they found considerable amounts of weapons, ammunitions,and military equipment that had been left behind by the Syrian Army. By the evening of June 10, Israel gained control of the Golan Heights, as a UN ceasefire came into effect. Because of the fighting, some 80,000 Syriancivilians were displaced.

Aftermath Israel achieved victory in one of the shortestwars in history, allowing it to expand its territory by three-fold; it hadgained control of the Sinai Peninsula and Gaza Strip, the West Bank, and the Golan Heights.

June 8, 2021

June 8, 1940 – World War II: Allied forces evacuate from Narvik, ending the Norwegian Campaign

On May 24, 1940, the Allied High Commanddecided to evacuate its forces from northern Norway,and the order for its implementation was sent to the Allied command in Norway, withinstructions to carry out the attack on Narvik as a cover for the Alliedwithdrawal. On June 7-8, 1940 underOperation Alphabet, British, French, and Polish forces were evacuated from Norway for Britain, together with King HaakonVII, the royal family, and Norwegian Cabinet. The Norwegian king had indicated his intention to remain in Norway, but was persuaded by the Britishambassador to depart for Britainto form a government-in-exile.

(Taken from Norwegian Campaign – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Europe – Vol. 6)

The Germans soon learned of the Alliedevacuation, and sent the battleships Scharnhorstand Gneisenau to intercept the Alliedconvoy. However, the German shipsencountered the British aircraft carrier HMSGlorious and her escort of two destroyers. In the ensuing battle, the German ships sank the HMS Glorious and the two destroyers, but Scharnhorst sustained heavy damage from a torpedo attack, and wasforced to retire to Trondheim. Another German attempt using the battleship Gneisenau, battle cruiser Admiral Hipper, and four destroyers tointercept the Allied ships was cancelled when the German ships detected thatthe Allied transport convoy was too heavily guarded.

On June 10, the Norwegian 6thArmy in northern Norwaysurrendered to the Germans. The 62-dayGerman campaign in Norwaywas over.

AftermathDuring World War II, Germany governed Norway under the newly formed Reichskommissariat Norwegen,a civilian administration led by ReichskommissarJosef Terboven. Terboven ruled harshlyand used the Gestapo (German secret police) to suppress all opposition, whichnot only alienated the local population, but also brought him into conflictwith General Nikolaus von Falkenhorst, the German military commander of Norway,who implemented a conciliatory policy to win over the Norwegians.

Quisling, the pro-Nazi politician whohad tried to take power in Osloduring the German invasion, was initially sidelined by the Germans because ofhis lack of popular support. But inFebruary 1942, he was allowed to form a civilian government, with himself asits “Minister President”, which had only limited administrative functions, andthe most important decisions remained with Terboven.

By May 1941, a Norwegian resistancemovement had emerged, with Milorg (Norwegian: Militær Organisasjon) being the largest among the armedmilitias. These partisans conductedraids, intelligence gathering, and sabotage operations; their most notableachievement was cooperating with he Allies in destroying the Telemark heavywater production facility in February 1943, which the Germans used in theirnuclear energy program to develop an atomic bomb.

The conquest of Norway brought positive and negative results to Germany. Iron-ore shipments to Germany increased significantly, and German airand naval bases in Norwaymade the British eastern coastal bases vulnerable to attack. From Norway,German surface and submarine fleets launched commerce-raiding attacks on Alliedmerchant ships in the Atlantic. With the German invasion of the Soviet Unionin June 1941, German ships also attacked the Allied Arctic convoys that broughtsupplies to the Russians through the ports of Murmansk and Archangelsk.

However, the campaignin Norwaycrippled the Germany Navy, which lost many ships and prevented the Germans fromlaunching another major naval operation of the same magnitude. Now suffering naval deficiency, Germany could not realistically launch across-channel invasion of Britain,which Hitler had planned after the fall of France. Moreover, for the remainder of the war, Germany was forced to allocate 400,000 troopsfor the defense of Norway,which became critical when the tide of war turned against Germany, as these troops were badlyneeded in the other fronts.

June 7, 2021

June 7, 1938 –Chinese Nationalist forces carry out the 1938 Yellow River Flood to halt the Japanese advance; some 500,000-600,000 Chinese civilians perish

In July 1937, Japanese forces launched a pre-emptive,full-scale invasion of China,sparking the Second Sino-Japanese War. The Japanese Army marched rapidly intothe heart of Chinese territory. By June 1938, the Japanese had control of allof North China. They easily captured thecoastal cities of China’seastern provinces; the Nationalist strongholds of Shanghai,Nanjing, and Wuhan also fell.

(Taken from Chinese Civil War – Wars of the 20th Century – Vol. 1)

To stop the Japanese from advancing into western andsouthern China, Chinese Nationalistleader Chiang Kai-shek ordered that the dikes of the Yellow River be destroyed. On June5-7, 1938, the dikes on the south bank were demolished, and flood watersspilled into Henan, Anhui,and Jiangsu,destroying vast stretches of farmlands. In the aftermath, the Nationalistgovernment estimated that 800,000 people perished while 10 million lost theirhomes. A 1994 study by the Red Chinese government places the figures at 900,000killed and 10 million displaced. Data from more recent studies place theestimate at 400,000-500,000 dead and 3-5 million displaced. The difficulty withascertaining exact figures is that at the time of the flooding, local officialshad already fled the areas, leaving no government control to determine thefigures. Because of the sheer numbers of deaths and displaced and the extensivedestruction generated, the 1938 Yellow River Flood has been called the “largestact of environmental warfare in history”.

Chiang Kai-shek Chiangcommitted major military blunders. At Nanjing, for instance, heallowed his forces to be trapped and then destroyed. Consequently, the Japanese killed 200,000civilians and soldiers in the city. Thenin a scorched earth strategy to delay the enemy’s advance, Chiang ordered thedams destroyed around Nanjing, which caused the Yellow River to flood and kill 500,000 people. Furthermore, as the Nationalist forcesretreated westward, they set fire to Changshato prevent the city’s capture by the Japanese, but this resulted in the deathsof 20,000 residents and the displacement of hundreds of thousands more, whowere not told of the plan.

The Chinese people’s confidence in their governmentplummeted, as it seemed to them that the Nationalist Army was incapable ofsaving the country. At the same time,the Communists’ popularity soared because, unlike the Nationalists who usedcostly open warfare against the Japanese, the Red Army employed guerillatactics with great success against the mostly lightly defended enemy outpostsin remote areas.