Daniel Orr's Blog, page 56

July 16, 2021

July 16, 1948 – 1948 Arab-Israeli War: Israeli forces capture Nazareth

On July 16, 1948, a powerful Israeli offensive in northernPalestine captured Nazarethand the whole region of lower Galilee extending from Haifain the coastal west to the Sea of Galilee inthe east. Further north, the Syrian Army continued to hold MishmarHayarden after stopping an Israeli attempt to take the town.

(Taken from 1948 Arab-Israeli War – Wars of the 20th Century: Vol. 1)

In southern Palestine,the Egyptian offensives in Negba (July 12), Gal (July 14), and Be-erot Yitzhakwere thrown back by the Israeli Army, with disproportionately high Egyptiancasualties. On July 18, the UN imposed a second truce, this time of nospecified duration.

The truce lasted nearly three months, when on October 15,fighting broke out once more. During the truce, relative calm prevailedin Palestinedespite high tensions and the occasional outbreaks of small-scalefighting. The UN also proposed new changes to the partition plan which,however, were rejected once more by the warring sides.

On September 22, the Israeli government passed a law thatmade all captured territories an integral part of Israel, including those that wouldbe won in the future. By the autumn of 1948, the Israeli Army totaled90,000 soldiers, greatly outnumbering the combined Arab expeditionaryforces. Large shipments of war materials continued to arrive in Israel.

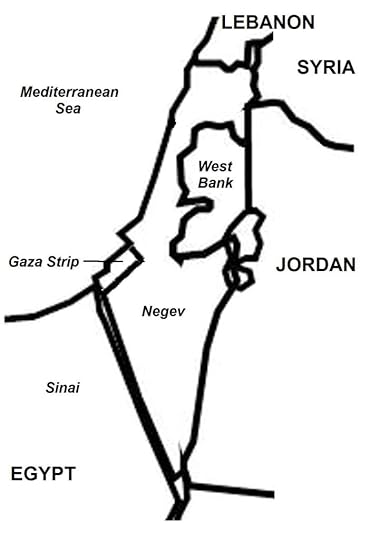

Arab-Israeli War. Key battle areas are shown. The Arab countries of Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq, assisted by volunteer fighters from other Arab states, invaded newly formed Israel that had occupied a sizable portion of Palestine.

Arab-Israeli War. Key battle areas are shown. The Arab countries of Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq, assisted by volunteer fighters from other Arab states, invaded newly formed Israel that had occupied a sizable portion of Palestine. In mid-October 1948, Israeli forces attacked and capturedEgyptian-held Beershebaand Bayt Jibrin. Consequently, the whole Negev came under Israelicontrol, with 4,000 Egyptian troops trapped in al-Faluja and Iraq al-Manshiyya, two villages near Ashkelon. Israeli warships blocked the EgyptianNavy from rescuing the trapped soldiers.

Later in October, the UN imposed a third truce. Fighting, however, continued in Marmon in northern Palestine. On October 24, anotherpowerful Israeli offensive captured the whole northern Galilee,forcing Syrian and Lebanese Army units, including Arab paramilitaryauxiliaries, to withdraw across their respective borders. Tens ofthousands of Palestinian civilians fled or were forced to leave to escape thefighting, although many other Arab residents (about 20%) remained. Thosewho remained eventually were granted Israeli citizenship.

In early November 1948, Israeli forces pursuing Lebanesetroops into the border penetrated five miles into Lebanon and captured many Lebanesevillages. Israel laterwithdrew its forces from Lebanonafter both countries signed an armistice at the end of the war.

On December 22, Israeli forces attacked Egyptian Armyunits positioned in the southern Negev,driving them across the Egyptian border after five days of fighting. TheIsraelis then crossed into the Sinai Peninsulaand advanced toward al-Arish to trap the Egyptian Army. Britain and the United States exerted pressure on Israel, forcing the latter towithdraw its forces from the Sinai.

On January 3, 1949, the Israeli Army surrounded theEgyptian forces inside the Gaza Strip in southwestern Palestine. Three days later, Egyptagreed to a ceasefire, which soon came into effect. The 1948 Arab-IsraeliWar was over. In the following months, Israelsigned separate armistices with Egypt,Lebanon, Jordan and Syria.

At war’s end, Israelheld 78% of Palestine,22% more than was allotted to the Jews in the original UN partition plan. Israel’s territoriescomprised the whole Galilee and JezreelValley in the north, the whole Negevin the south, the coastal plains, and West Jerusalem. Jordan acquired the WestBank, while Egyptgained the Gaza Strip. No Palestinian Arab state was formed.

The 1948 Arab-Israeli War. Palestine and adjacent countries are shown, as are the West Bank and the Gaza Strip.

The 1948 Arab-Israeli War. Palestine and adjacent countries are shown, as are the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. During the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, and the 1947-1948 CivilWar in Palestine (previous article) that preceded it, over 700,000 Palestinian Arabs fledfrom their homes, with most of them eventually settling in the West Bank, GazaStrip, and southern Lebanon(Map 11). About 10,000 Palestinian Jews also were displaced by theconflict. Furthermore, as a consequence of these wars, tens of thousandsof Jews left or were forced to leave from many Arab countries. Most ofthese Jewish refugees settled in Israel.

July 15, 2021

July 15, 1966 – Vietnam War: American and South Vietnamese forces launch Operation Hastings against the North Vietnamese in the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ)

In June 1966, North Vietnamese forces again attacked acrossthe DMZ, but were repulsed by U.S. Marines, supported by South Vietnamese unitsand American air, artillery, and naval forces. U.S.forces then launched Operation Hastings, leading to three weeks of largebattles near Dong Ha and ending with the North Vietnamese withdrawing backacross the DMZ. The year 1966 also sawthe United States greatly escalating the war, with U.S. deployment being increasedover two-fold from the year before, from 184,000 in 1965 to 385,000 troops in1966. In 1967, U.S. deployment would top 485,000and then peak in 1968 with 536,000 soldiers.

(Taken from Vietnam War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia: Vol. 5)

Throughout 1967, combat activity in the DMZ consisted ofartillery duels, North Vietnamese infiltrations, and firefights along theborder. As the North Vietnamese actuallyused their side of the DMZ as a base to stage their infiltration attacks, inMay 1967, the U.S. Marines militarized the southern side of the DMZ, whichsparked increased fighting inside the DMZ. Also starting in September 1967 and continuing for many months, NorthVietnamese artillery batteries pounded U.S Marine positions near the DMZ, whichinflicted heavy casualties on American troops. In response, U.S.aircraft launched bombing attacks on North Vietnamese positions across the DMZ.

Aftermath of theVietnam War The war had a profound, long-lasting effect on the United States. Americans were bitterly divided by it, andothers became disillusioned with the government. War cost, which totaled some $150 billion($1 trillion in 2015 value), placed a severe strain on the U.S. economy,leading to budget deficits, a weak dollar, higher inflation, and by the 1970s,an economic recession. Also toward theend of the war, American soldiers in Vietnamsuffered from low morale and discipline, compounded by racial and socialtensions resulting from the civil rights movement in the United States during the late 1960sand also because of widespread recreational drug use among the troops. During 1969-1972 particularly and during theperiod of American de-escalation and phased troop withdrawal from Vietnam, U.S.soldiers became increasingly unwilling to go to battle, which resulted in thephenomenon known as “fragging”, where soldiers, often using a fragmentationgrenade, killed their officers whom they thought were overly zealous and eagerfor combat action.

Furthermore, some U.S.soldiers returning from Vietnamwere met with hostility, mainly because the war had become extremely unpopularin the United States,and as a result of news coverage of massacres and atrocities committed byAmerican units on Vietnamese civilians. A period of healing and reconciliation eventually occurred, and in 1982,the Vietnam Veterans Memorial was built, a national monument in Washington, D.C.that lists the names of servicemen who were killed or missing in the war.

Following the war, in Vietnamand Indochina, turmoil and conflict continuedto be widespread. After South Vietnam’scollapse, the Viet Cong/NLF’s PRG was installed as the caretakergovernment. But as Hanoide facto held full political and military control, on July 2, 1976, North Vietnam annexed South Vietnam, and the unifiedstate was called the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.

Some 1-2 million South Vietnamese, largely consisting offormer government officials, military officers, businessmen, religious leaders,and other “counter-revolutionaries”, were sent to re-education camps, whichwere labor camps, where inmates did various kinds of work ranging fromdangerous land mine field clearing, to less perilous construction andagricultural labor, and lived under dire conditions of starvation diets and ahigh incidence of deaths and diseases.

In the years after the war, the Indochina refugee crisisdeveloped, where some three million people, consisting mostly of those targetedby government repression, left their homelands in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos,for permanent settlement in other countries. In Vietnam,some 1-2 million departing refugees used small, decrepit boats to embark onperilous journeys to other Southeast Asian nations. Some 200,000-400,000 of these “boat people”perished at sea, while survivors who eventually reached Malaysia, Indonesia,Philippines, Thailand,and other destinations were sometimes met there with hostility. But with United Nations support, refugeecamps were established in these Southeast Asian countries to house and processthe refugees. Ultimately, some 2,500,000refugees were resettled, mostly in North America and Europe.

The communist revolutions triumphed in Indochina: in April1975 in Vietnam and Cambodia, and in December 1975 in Laos. Because the United States used massive air firepower in the conflicts, North Vietnam, eastern Laos, and eastern Cambodia were heavily bombed. U.S.planes dropped nearly 8 million tons of bombs (twice the amount the United States dropped in World War II), and Indochina became the most heavily bombed area inhistory. Some 30% of the 270 millionso-called cluster bombs dropped did not explode, and since the end of the war,they continue to pose a grave danger to the local population, particularly inthe countryside. Unexploded ordnance(UXO) has killed some 50,000 people in Laosalone, and hundreds more in Indochina arekilled or maimed each year.

The aerial spraying operations of the U.S. military, carriedout using several types of herbicides but most commonly with Agent Orange (whichcontained the highly toxic chemical, dioxin), have had a direct impact onVietnam. Some 400,000 were directlykilled or maimed, and in the following years, a segment of the population thatwere exposed to the chemicals suffer from a variety of health problems,including cancers, birth defects, genetic and mental diseases, etc.

Some 20 million gallons of herbicides were sprayed on 20,000km2 of forests, or 20% of Vietnam’stotal forested area, which destroyed trees, hastened erosion, and upset theecological balance, food chain, and other environmental parameters.

Following the Vietnam War, Indochinacontinued to experience severe turmoil. In December 1978, after a period of border battles and cross-borderraids, Vietnam launched afull-scale invasion of Cambodia(then known as Kampuchea)and within two weeks, overwhelmed the country and overthrew the communist PolPot regime. Then in February 1979, inreprisal for Vietnam’sinvasion of its Kampuchean ally, Chinalaunched a large-scale offensive into the northern regions of Vietnam, but after one month ofbitter fighting, the Chinese forces withdrew. Regional instability would persist into the 1990s.

July 14, 2021

July 14, 1969 – Football War: Fighting breaks out between El Salvador and Honduras

(Taken from Football War – Wars of the 20th Century – Vol. 1)

On July 3 and July 14, Honduran planes flew over Salvadoranair space. El Salvador condemned theterritorial violations and sprung into military action. In the afternoon of July 14, Salvadoranaircraft, including C-47 transports that were improvised to dispense bombs,attacked Honduran airfields in Tegucigalpaand other locations. The Salvadoranobjective was a pre-emptive air strike to destroy the much larger Honduran AirForce on the ground. However, nosignificant damage was made on the Honduran planes.

A few hours later and under cover of evening darkness,Salvadoran ground forces crossed the border into Honduras (Map 25). Major Salvadoran offensives were made in Honduras’ eastern provinceof Valle, leading to the capture ofthe towns of Aramecina and Goascoran, and in Ocotepeque Provincein the west, where Nueva Ocotepeque and La Labor were taken. The Salvadoran Army also captured Honduras’ north central border towns of Guarita,Valladolid, and La Virtud, and the Honduranislands in the Gulf of Fonseca, off thePacific coast.

Background By May1969, the land reform law in Honduraswas being fully implemented. Thousandsof dispossessed Salvadoran families returned to El Salvador, causing a sudden surgein the Salvadoran population, and straining the country’s economic resourcesand the government’s capacity to provide public services. El Salvadorcondemned Honduras,generating tensions and animosity on both sides. Nationalistic sentiments were fueled bypropaganda and rhetoric spouted by the media from the two sides.

Such was the charged atmosphere leading up to the threefootball matches between El Salvadorand Hondurasin June 1969. The first match was playedon June 8 in Tegucigalpa, Honduras’ capital, which was won 1-0 by the host team. Aside from some fansfighting in the stands, no major security breakdown occurred during the match.

In El Salvador, however, soccer fans were infuriatedby the result, believing they had been cheated. The Salvadoran media described the football matches as epitomizing the“national honor”. After the defeat, adespondent Salvadoran fan died after shooting herself. Her death became a rallying cry forSalvadorans who considered her a martyr. Thousands of Salvadorans, including the country’s president and othertop government officials, attended her funeral and joined the nation inmourning her death.

The second match was played in El Salvador on June 15, 1969, andwas won 3- 0 also by the home team, thereby leveling the series at one winapiece. The tense situation during thegame broke out in widespread violence across the capital, San Salvador. Street clashes led to many deaths, including those of Honduranfans. As a precaution, the Honduranfootball team was housed in an undisclosed location and driven to the game inarmored vehicles. After the game, theHonduran team’s vehicles plying the road back to Honduras were stoned while passingthrough Salvadoran towns.

In Honduras,the people retaliated by attacking and looting Salvadoran shops in Tegucigalpa and othercities and towns. Armed bands of thugsroamed the countryside targeting Salvadorans – beating up and killing men,raping women, burning houses, and destroying farms. Thousands of Salvadorans fled toward theborder to El Salvador. And as the prospect of war drew closer,Salvadoran and Honduran security forces guarding the border engaged in sporadicexchanges of gunfire.

The third, deciding football match was played on June 26,1969 in Mexico City,which was won by the Salvadoran team 3 – 2 in overtime. Two days earlier, Hondurashad cut diplomatic relations with El Salvador. The Salvadoran government reciprocated onJune 26, accusing Hondurasof committing “genocide” by killing Salvadoran immigrants. The two sides prepared for war by increasingtheir weapons stockpiles, which were sourced from private dealers because the United Stateshad imposed an arms embargo.

July 13, 2021

July 13, 1977 – Ogaden War: Somalian forces invade the Ogaden region of Ethiopia

On July 13, 1977, the Somali armed forces launched afull-scale invasion of the Ogaden. (Somaliaofficially stated that it did not directly participate in the war using itsregular forces; instead, the Somali soldiers who took part in the war were“volunteers on leave” who had come to fight on the side of their Somalibrothers.) At the outbreak of war, interms of troop strength, the Ethiopian Army outnumbered its Somali counterpartby a ratio of about 2:1; however, the Somalis possessed more planes andartillery, and held a more than 3:1 advantage over the Ethiopians in numbers oftanks and armored vehicles. The Somaliinvasion forces consisted of some 30,000 to 50,000 soldiers, 250 tanks, 350armored personnel carriers, 600 artillery pieces, and dozens of aircraft, andcrossed in many points across the border along two major fronts: the northernfront with its command based in Hargeisa, and the southern front with itscommand based in Baidoa and Mogadishu. The southern advance made rapid progress,taking Gode, Delo, and Filtu. At Gode,the Somalis inflicted heavy losses on Ethiopian militias who were sent toreinforce the town’s garrison, and seized large quantities of abandoned weaponsand ammunitions.

(Taken from Ogaden War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

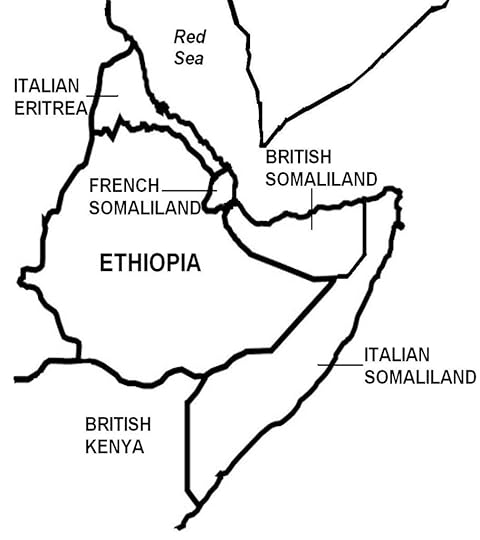

Background InDecember 1950, with Allied approval, the United Nations granted Italy a trusteeship over Italian Somaliland onthe condition that Italygrants the territory its independence within ten years. On June 26, 1960, Britaingranted independence to British Somaliland, which became the State of Somaliland, and a few days later, Italy also granted independence to the TrustTerritory of Somaliland (the former Italian Somaliland). On July 1, 1960, the two new states merged toform the Somali Republic(Somalia).

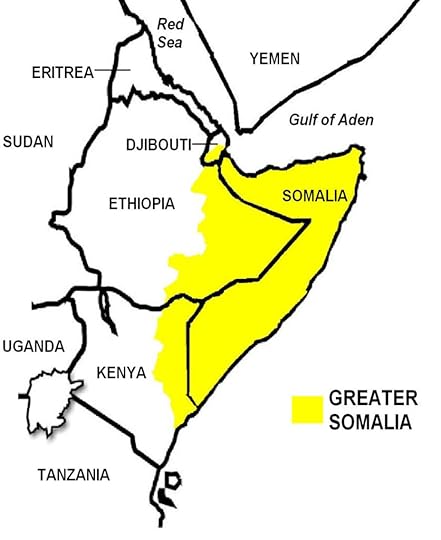

The newly sovereign enlarged state had as its primaryforeign affairs mission the fulfillment of “Greater Somalia” (also known asPan-Somalism; Figure 29), an irredentist concept that sought to bring into aunited Somali state all ethnic Somalis in the Horn of Africa who currently wereresiding in neighboring foreign jurisdictions, i.e. the Ogaden region inEthiopia, Northern Frontier District (NFD) in Kenya, and FrenchSomaliland. Somaliaofficially did not claim ownership to these foreign territories but desiredthat ethnic Somalis in these regions, particularly where they formed apopulation majority, be granted the right to decide their political future,i.e. to remain with these countries or to secede and merge with Somalia.

Nationalist Somalis in Kenyaand Ethiopia, desiring to bejoined with Somalia,soon launched guerilla insurgencies. Inthe Ogaden region, many guerilla groups organized, the foremost of which wasthe Western Somali Liberation Front (WSLF), founded in 1960, just after Somaliagained its independence. The Somaligovernment began to build its armed forces, eventually setting as a goal aforce of about 20,000 troops that it deemed was powerful enough to realize thedream of Greater Somalia. Butconstrained by economic limitations, Somaliasought the assistance of various Western powers, particularly the United States, but the latter only promised toprovide military resources for a 5,000-strong armed forces, which it deemed wassufficient for Somaliato defend its borders against external threats.

The Somali government then turned to communist states,particularly the Soviet Union; although these countries’ Marxist ideology rancontrary to its own democratic institution, Somalia viewed this as a means tobe political self-reliant and not be too dependent on the West, and to courtboth sides in the Cold War. Thus, fornearly two decades after gaining its independence, Somalia received military supportfrom both western and communist countries.

In 1962, the Soviet Union provided Somalia with asubstantial loan under generous terms of repayment, allowing the Somaligovernment to build in earnest an offense-oriented armed forces; subsequentSoviet loans and military assistance led to the perception in the internationalcommunity that Somalia fell under the Soviet sphere of influence, bolsteredfurther as Soviet planes, tanks, artillery pieces, and other military hardwarewere supplied in large quantities to the Somali Army Forces.

Tensions between Ethiopian security forces and the Ogaden Somalissporadically led to violence that soon deteriorated further with Somali Armyunits intervening, leading to border skirmishes between Ethiopian and Somaliregular security units. Large-scale fighting by both sides finally broke out inFebruary 1964, which was triggered by a Somali revolt in June 1963 atHodayo. Somali ground and air units camein support of the rebels but Ethiopian planes gained control of the skies andattacked frontier areas, including Feerfeer and Galcaio. Under mediation efforts provided by Sudanrepresenting the Organization of African Unity (OAU), in April 1964, aceasefire was agreed that imposed a separation of forces and a demilitarizedzone on the border. In the aftermath, inlate 1964, Ethiopia enteredinto a mutual defense treaty with Kenya (which also was facing arebellion by local ethnic Somalis supported by the Somali government) in caseof a Somali invasion; this treaty subsequently was renewed in 1980 and then in1987.

On October 21, 1969, a military coup overthrew Somalia’sdemocratically elected civilian government and in its place, a military juntacalled the Supreme Revolutionary Council (SRC) was set up and led by GeneralMohamed Siad Barre, who succeeded as president of the country. The SRC suspended the constitution, bannedpolitical parties, and dissolved parliament, and ruled as a dictatorship. The country was renamed the Somali DemocraticRepublic. Exactly one year after the coup,on October 21, 1970, President Barre declared the country a Marxist state, althougha form of syncretized ideology called “scientific revolution” was implemented,which combined elements of Marxism-Leninism, Islam, and Somalinationalism. The SRC forged even closerdiplomatic and military ties with the Soviet Union,which led in July 1974 to the signing of the Treaty of Friendship andCooperation, where the Soviets increased military support to the SomaliArmy. Earlier in 1972, under aSomali-Soviet agreement, the Russians developed the Somali port of Berbera,converting it into a large naval, air, and radar and communications facilitythat allowed the Soviets to project power into the Middle East, Red Sea, and Persian Gulf. TheSoviets also established many new military airfields, including those in Mogadishu, Hargeisa,Baidoa, and Kismayo.

Under pressure from the Soviet government to form a“vanguard party” along Marxist lines, in July 1976, President Barre dissolvedthe SRC which he replaced with the Somali Revolutionary Socialist Party (SRSP),whose Supreme Council (politburo) formed the new government, with Barre as itsSecretary General. The SRSP, as the solelegal party, was intended to be a civilian-run entity to replace themilitary-dominated SRC; however, since much of the SRC’s political hierarchysimply moved to the SRSP, in practice, not much changed in governance and Barrecontinued to rule as de facto dictator.

With a greatly enhanced Somali military capability,President Barre pressed irredentist aspirations for Greater Somalia, steppingup political rhetoric against Ethiopiaand spurning third-party mediations to resolve the emerging crisis. Then in the mid-1970s, favorablecircumstances allowed Somaliato implement its irredentist ambitions. During the first half of 1974, widespread military and civilian unrest grippedEthiopia,rendering the government powerless. InSeptember 1974, a group of junior military officers called the “CoordinatingCommittee of the Armed Forces, Police, and Territorial Army”, which simply wasknown as “Derg” (an Ethiopian word meaning “Committee” or “Council”), seizedpower after overthrowing Ethiopia’s long-ruling aging monarch, Emperor HaileSelassie. The Derg succeeded in power,dissolved the Ethiopian parliament and abolished the constitution, nationalizedrural and urban lands and most industries, ruled with absolute powers, andbegan Ethiopia’s gradual transition from an absolute monarchy to aMarxist-Leninist one-party state.

Ethiopiatraditionally was aligned with the West, with most of its military suppliessourced from the United States. But with its transition toward socialism, the Derg regime forged closerties with the Soviet Union, which led to thesigning in December 1976 of a military assistance agreement. Simultaneously, Ethiopian-American relationsdeteriorated, and with U.S. President Jimmy Carter criticizing Ethiopia’s poorhuman rights record, in April 1977, the Derg repealed Ethiopia’s defense treatywith the United States, refused further American assistance, and expelled U.S.military personnel from the country. Atthis point, both Ethiopiaand Somalialay within the Soviet sphere and thus ostensibly were on the same side in theCold War, but a situation that was unacceptable to President Barre with regardsto his ambitions for Greater Somalia.

In the aftermath of the Derg’s seizing power, Ethiopiaexperienced a period of great political and security unrest, as the governmentbattled Marxist groups in the White Terror and Red Terror, regionalinsurgencies that sought to secede portions of the country, and the Derg itselfracked by internal power struggles that threatened its own survival. Furthermore, the Derg distrusted thearistocrat-dominated military establishment and purged the ranks of the officercorps; some 30% of the officers were removed (including 17 generals who wereexecuted in November 1974). At thistime, the Ogaden insurgency, led by the WSLF and other groups, also increasedin intensity, with Ethiopian military outposts and government infrastructuressubject to rebel attacks. Just a fewyears earlier, President Barre did not provide full military support to theOgaden rebels, encouraging them to seek a negotiated solution throughdiplomatic channels and even with Emperor Haile Selassie himself. These efforts failed, however, and with Ethiopiasinking into crisis, President Barre saw his chance to step in.

July 12, 2021

July 12, 1943 – World War II: German and Soviet tanks clash at the Battle of Prokhorovka, one of the biggest armored engagements of all time

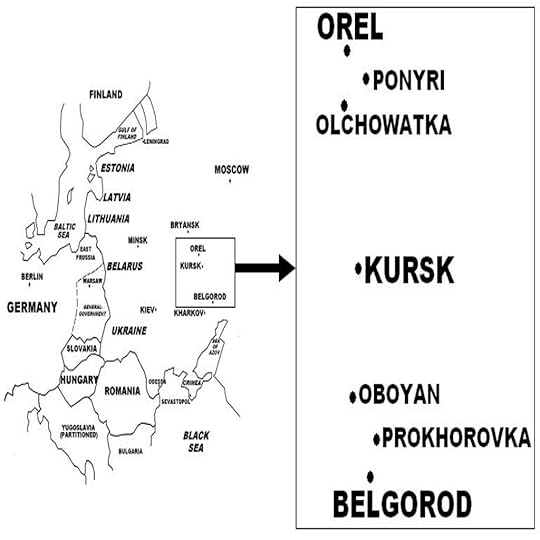

On July 5, 1943, the German Army launched Operation Citadel,sparking the Battle of Kursk aimed at pinching off the Soviet salient. Thenorthern front of the offensive bogged down within four days. On the southernfront, the German 4th Panzer Army made slow, steady progress and broke througha series of Soviet defensive lines. On July 12, the Soviets launched theircounter-attack on the northern and southern fronts. In the south, the Soviet5th Guards Tank Army clashes with units of the German 4th Panzer Army, breakingGerman attack before the Soviet third defensive line and the town ofProkhorovka.

Also on July 12, Adolf Hitler ordered that Operation Citadelbe aborted, in order to transfer some units to southern Italy where the Western Allies hadopened a second front. Following the German failure at the Battle of Kursk, theSoviet Red Army wrested the strategic initiative on the Eastern Front, which itwould hold for the rest of the war.

It was long believed that the Battle of Prokhorovka was thelargest tank battle in history. More recent research has dispelled this myth:only 294 German tanks and 616 Soviet tanks were involved, not the 1,200 to2,000 tanks previously believed. German losses of 3,500 – 10,000 troops and350-400 tanks have also been disproved, as more archival records place these at800 troops and 43-80 tanks. By comparison, Soviet losses at Prkhorovka were5,500 troops and 300-400 tanks.

(Taken from Invasion of the Soviet Union – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe: Vol. 6)

Preparations for the Battle of Kursk OnMarch 10, 1943, as the battle of Kharkov waswinding down, General Manstein, head of German Army Group South, set his sightson eliminating a large gap around Kursk that hadformed between his forces and those of German Army Group Center. With Hitler issuing Order No. 5 (March 13)authorizing such an operation, General Manstein and General Gunther von Kluge,commander of German Army Group Center, made preparations to immediately attackthe Kursk salient. But with strongSoviet concentrations on the northern side of the salient, as well asreinforcements being rushed to the south to stem General Manstein’s northernadvance, the proposed joint offensive was suspended. By then also, German forces were exhausted,and the rasputitsa season had set in, preventing further large-scale armored movement.

The Kursksalient was a Soviet protrusion into German-occupied territory, measuring 160miles long from north to south and 100 miles from east to west. Kurskand the surrounding region held no strategic value to either side, but to theGermans (and the Soviets), pinching off the salient would eliminate the dangerto their flanks.

In April 1943, Hitler’s Order No. 6 formalized the attack onthe Kursk salient under Operation Citadel, which consisted of a pincersmovement aimed at trapping five Soviet armies, with the northern pincer ofGerman Army Group Center’s 9th Army thrusting from Orel, and the southernpincer of German Army Group South’s 7th Panzer Army and German Army DetachmentKempf advancing from around Belgorod. The offensive was set for May 3.

In late April 1943, Kluge expressed doubts to Hitler aboutthe feasibility of Operation Citadel, as German air reconnaissance showed thatthe Soviets were constructing strong fortifications along the northern side ofthe salient. As well, General Mansteinwas concerned, as his idea of launching a surprise attack on the unfortifiedsalient could not be achieved anymore. The May 3 launch was not met, and on May 4, Hitler met with GeneralsKluge and Manstein and other senior officers to discuss whether or notOperation Citadel should proceed, or that other options be explored. But as the meeting produced no consensus,Hitler remained committed to the operation, resetting its launch for June 12,1943. With other issues consequentlycoming up, Hitler postponed the launch date to June 20, then to July 3, andfinally to July 5, 1943.

As Operation Citadel was successively pushed back, with thedelays ultimately lasting over two months, it also grew in importance, asHitler saw Kursk as the battle that wouldrestore German superiority in the Eastern Front following the Stalingraddebacle, which continued to weigh heavily on him and the German HighCommand. Like his generals, Hitler wasconcerned with the massive Soviet buildup in the salient, but believed that hisforces would break through, as well as surprise the enemy, using theWehrmacht’s latest armored weapons, the versatile Panther tank, the heavy Tigerbattle tank, and the goliath Elefant (“Elephant”) tank destroyer. Regaining the military initiative with avictory at Kursk also might convince Hitler’sdemoralized Axis partners, Italy,Romania, and Hungary, whose armies were battered at Stalingrad, to reconsider quitting the war.

Hitler’s concerns regarding Kursk were warranted, as the Soviets were indeedfully concentrating on the region. Butunbeknown to Hitler and the German senior staff, Stalin and the Soviet HighCommand were aware of many details of Operation Citadel, with the informationbeing provided to Soviet intelligence by the Lucy spy ring, a network ofanti-Nazi German officers working clandestinely in cooperation with the Swissintelligence bureau. Stalin and a numberof senior officers wanted to launch a pre-emptive attack to disrupt the German plans.

However, General Georgy Zhukov, deputy head of the SovietHigh Command and who was instrumental in the Soviet successes in Leningrad, Moscow, and Stalingrad and was therefore highly regarded by Stalin,convinced the latter to adopt a strategic defense against the German attack,and then to launch a counter-offensive after the Wehrmacht was weakened. Under General Zhukov’s direction, the SovietCentral Front and Voronezh Front, which defended the northern and southernsides of the salient respectively, implemented a “defense-in-depth” strategy:using 300,000 civilian laborers, six defensive lines (three main forward andthree secondary rear lines) were constructed on either side of Kursk, the totaldepth reaching over 90 miles. Thesedefensive lines, particularly the main forward lines, were fortified withminefields, wire entanglements, anti-tank obstacles, infantry trenches, dug-inarmored vehicles, and artillery and machinegun emplacements.

A German attack, even if it broke through all six lineswhile facing furious Soviet artillery fire in the minefields in between eachline, would then encounter additional defensive lines by the reserve SovietSteppe Front; by then, the Germans would have advanced through many defensivelayers a distance of 190 miles under continuous Soviet air and armoredcounter-attacks and artillery fire.

The buildup to Kurskalso saw the Soviets making extensive use of military deception, e.g. dummyairfields, camouflaged artillery positions, night movement of troops, falseradio communications, concealed troop concentrations and ammunition stores,spreading rumors in German-held areas, etc. These measures were so effective that the Germans grossly underestimatedSoviet strength at Kursk:at the start of the battle, the Red Army had assembled 1.9 million troops, 5,100tanks, and 25,000 artillery pieces and mortars, while the Germans fielded780,000 troops, 2,900 tanks, and 10,000 artillery pieces and mortars. This great imbalance of forces, as well aslarge numbers of Red Army reserves and extensive Soviet defensive preparations,would be decisive in the outcome of the battle.

July 11, 2021

July 11, 1995 – Bosnian War: The Srebrenica Massacre takes place, where 8,000 persons are killed

TheInternational Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY),established by the UN to prosecute war crimes, determined that Bosnian Serbatrocities committed in the town of Srebrenica,where 8,000 civilians were killed, constituted a genocide. Otheratrocities, such as the killing and wounding of over one hundred residents inMarkale on February 5, 1994 and August 28, 1995resulting from the Serbian mortar shelling of Sarajevo, have been declared bythe ICTY as ethnic cleansing (a war crime less severe than genocide).

(Taken from Bosnian War – Wars of the 20th Century –Vol. 1)

Background of the Bosnian WarBosnia-Herzegovina has three main ethnic groups: Bosniaks (BosnianMuslims), comprising 44% of the population, Bosnian Serbs, with 32%, andBosnian Croats, with 17%. Sloveniaand Croatiadeclared their independences in June 1991. On October 15, 1991, theBosnian parliament declared the independence of Bosnia-Herzegovina, withBosnian Serb delegates boycotting the session in protest. Then acting ona request from both the Bosnian parliament and the Bosnian Serb leadership, aEuropean Economic Community arbitration commission gave its opinion, on January11, 1992, that Bosnia-Herzegovina’s independence cannot be recognized, since noreferendum on independence had taken place.

BosnianSerbs formed a majority in Bosnia’snorthern regions. On January 5, 1992, Bosnian Serbs seceded fromBosnia-Herzegovina and established their own country. Bosnian Croats, whoalso comprised a sizable minority, had earlier (on November 18, 1991) secededfrom Bosnia-Herzegovina by declaring their own independence. Bosnia-Herzegovina, therefore, fragmented into three republics, formed along ethniclines.

Furthermore,in March 1991, Serbia and Croatia, two Yugoslav constituent republics locatedon either side of Bosnia-Herzegovina, secretly agreed to annex portions ofBosnia-Herzegovina that contained a majority population of ethnic Serbians andethnic Croatians. This agreement, later re-affirmed by Serbians andCroatians in a second meeting in May 1992, was intended to avoid armed conflictbetween them. By this time, heightened tensions among the three ethnicgroups were leading to open hostilities.

Mediatorsfrom Britain and Portugalmade a final attempt to avert war, eventually succeeding in convincingBosniaks, Bosnian Serbs, and Bosnian Croats to agree to share political powerin a decentralized government. Just ten days later, however, the Bosniangovernment reversed its decision and rejected the agreement after taking issuewith some of its provisions.

War At any rate, by March 1992,fighting had already broken out when Bosnian Serb forces attacked Bosniakvillages in eastern Bosnia. Of the three sides, Bosnian Serbs were the most powerful early in the war, asthey were backed by the Yugoslav Army. At their peak, Bosnian Serbs had150,000 soldiers, 700 tanks, 700 armored personnel carriers, 3,000 artillerypieces, and several aircraft. Many Serbian militias also joined theBosnian Serb regular forces.

BosnianCroats, withthe support of Croatia,had 150,000 soldiers and 300 tanks. Bosniaks were at a greatdisadvantage, however, as they were unprepared for war. Although much of Yugoslavia’swar arsenal was stockpiled in Bosnia-Herzegovina, the weapons were held by theYugoslav Army (which became the Bosnian Serbs’ main fighting force in the earlystages of the war). A United Nations (UN) arms embargo on Yugoslaviawas devastating to Bosniaks, as they were prohibited from purchasing weaponsfrom foreign sources.

InMarch and April 1992, the Yugoslav Army and Bosnian Serb forces launchedlarge-scale operations in eastern and northwest Bosnia-Herzegovina. Theseoffensives were so powerful that large sections of Bosniak and Bosnian Croatterritories were captured and came under Bosnian Serb control. By the endof 1992, Bosnian Serbs controlled 70% of Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Thenunder a UN-imposed resolution, the Yugoslav Army was ordered to leaveBosnia-Herzegovina. However, the Yugoslav Army’s withdrawal did notaffect seriously the Bosnian Serbs’ military capability, as a great majority ofthe Yugoslav soldiers in Bosnia-Herzegovina were ethnic Serbs. These soldierssimply joined the ranks of the Bosnian Serb forces and continued fighting,using the same weapons and ammunitions left over by the departing YugoslavArmy.

July 10, 2021

July 10, 1951 – Korean War: Armistice negotiations begin at Kaesong

On July 10, 1951, representatives from the warring sides, China and North Korea on the one hand, and the United States, South Korea,and the United Nations opened armistice talks at Kaesong to try and end the Korean War. Kaesong (now part of North Korea) was located near thenorthern edge of the battle lines. Negotiations proved lengthy and contentiousand proceeded slowly, with long intervals between meetings. Talks were latermoved to Panmunjom, a nearby village, where anarmistice would be signed in July 1953.

(Taken from Korean War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia: Vol. 5)

Continuinghostilities before and during the armistice talks U.S. and South Korean forcessettled down to a defensive posture, fortifying existing positions. Meanwhile at the United Nations, American andSoviet delegates met to try and end the war. Then on June 23, 1951, the Soviet representative to the UN proposed anarmistice between China and North Korea on the one hand, and the United States, South Korea, and the UN, on the other hand, a proposal that wasreceived favorably by the U.S.and Chinese governments. On July 10,1951, delegates from the warring parties opened armistice talks at Kaesong. Within a few months, negotiations were movedsix miles east to Panmunjom (Figure 16), whichbecame the permanent site of negotiations. Subsequently, for the Korean War, the active phase of full-scale warfarecame to an end.

Kim Il-sung and Syngman Rhee, leaders of North Korea andSouth Korea, respectively, strongly opposed the peace negotiations and wantedto continue the war, as both were determined to reunify the Korean Peninsulaby force under their rule. But withoutthe support of the major powers, the two Korean governments were forced to backdown. The negotiations proved long andarduous, and ultimately lasted two years (July 1951-July 1953) punctuated by anumber of stoppages in the talks. Duringthis period, the fighting produced no major territorial changes, leading to astalemate in the battlefield.

One major cause of the delay in the settlement was that thewar had produced an uneven line across the 38th parallel, with the central andeastern sections being north of the parallel and the western section beingsouth of the parallel, and with a net territorial loss to North Korea. Chinese and North Korean delegates arguedthat the 38th parallel must be the armistice line, which American and SouthKorean representatives opposed, stating that the current frontlines must be thearmistice line, as these are much more defensible compared to the topographyalong the 38th parallel. By late 1951,with no agreement reached and fighting continuing, the communist side droppedits demand of opposing forces returning to the 38th parallel, and the twowarring sides came to an agreement that the frontlines during the time of thesigning of a truce would serve as the armistice line.

A second major point of contention was the issue of theprisoners of war (POWs). UN forces heldsome 150,000 Chinese and North Korean POWs, of which a sizable number refusedto be repatriated back to the their homelands, which provoked China and NorthKorean to accuse UN forces of using underhanded methods to preventrepatriation. In particular, the Chinesegovernment claimed that anti-communist Chinese POWs were allowed to torturecommunist Chinese POWs to force the latter to refuse being repatriated. In one notable event in mid-June 1953 (onemonth before the armistice agreement was signed), the South Korean governmentreleased some 27,000 anti-communist North Korean POWs, stating that theprisoners had escaped from prison.

On the UN side, American and South Korean POWs were muchmore subject to physical abuse than other UN prisoners, especially by theirNorth Korean captors. American POWssuffered from tortures, starvation, and forced labor, if not being outrightexecuted. UN prisoners in Chinese POWcamps rarely were executed, but suffered mass starvation, particularly in the1950-1951 winter, where nearly half of all U.S. POWs died from hunger. Responding to accusations by the Trumanadministration that American POWs were being ill-treated, the Chinese governmentstated that because its logistical system suffered severe inadequacies, foodshortages were widespread at the frontlines, and in fact thousands of its owntroops also perished from starvation (as well as from the sub-zero harsh winterconditions).

Furthermore, 80,000 South Korean soldiers remained missing,whom the UN command and South Korean government believed had been captured byNorth Korean forces, and were then coerced into joining the North Korean Armyor were being used as forced laborers. North Korearejected these accusations, saying that it had only 10,000 South Korean POWs,that its other POWs already had been released or were killed by the UN airattacks, and that it did not use forced recruitment into its armed forces. As a result, the fates of the missing SouthKorean POWS remained undetermined after the war.

The armistice talks ended the period of large-scaleoffensives. Then during the ensuingtwo-year period of stalemate, only small- to medium-scale limited-scope battlestook place. Most of these battles wereinitiated by UN forces, and were aimed at gaining territory that would give theUN forces better strategic and defensive positions.

In September-October 1951, after negotiations temporarilybroke down, American and South Korean forces launched a limited operation inthe central sector, advancing seven miles north of the Kansas Line. In the western sector, UN forces alsosucceeded in establishing new positions north of the Wyoming Line.

U.S.planes continued its domination of the skies, attacking enemy road and railnetworks, supply centers, and ammunition depots. In 1952, U.S.air strikes in North Koreaincreased. The vital hydroelectricfacility at Suiho was attacked in July, and Pyongyang was subject to a large raid in August. The attack on the North Korean capital, whichinvolved 1,400 air sorties, was the largest single-day air operation of thewar.

In May 1952, General Mark Clark became the new commander ofUN forces, replacing General Ridgway. InJune 1952, after a series of fierce clashes, U.S.forces dislodged the enemy from the heights in Chorwon County,and established 11 patrol bases in a number of hills, including the highest andmost strategically important hill called “Old Baldy”. Many intense battles took place during thesecond half of 1952, as Chinese and North Korean forces attacked UN frontlineoutposts in response to U.S.air raids in North Korea. By this time, UN forces had adopted adefensive posture, and fortified their positions with trenches, bunkers,minefields, barbwire, and other obstacles all across the UN main line ofresistance from east to west of the peninsula.

In spring 1953, Chinese forces again put pressure on UNlines. But by now with fortifiedpositions on both sides, the mounting casualties, the absence of large-scaleoffensives, and the stalemated battlefield situation, the deadlock appeared tolast indefinitely. In April 1953, peacetalks resumed. Six months earlier, onNovember 29, 1952, President-elect Dwight Eisenhower, who had just won the U.S. presidential elections three weeks earlierand had promised to end the war, visited Korea to determine how thenegotiations could be accelerated. Healso threatened to use nuclear weapons in response to a build-up of Chineseforces in the western sector of the line. Furthermore, with the death of Soviet hard-line leader Joseph Stalin inMarch 1953, the new Soviet government was more conciliatory with the West, andput pressure on China toreach a peace settlement in Korea.

On April 20-26, 1953, under Operation Little Switch, bothsides exchanged sick and wounded POWs. In May-June 1953, as peace talks continued, Chinese forces launchedlimited attacks on UN positions, which were repulsed with heavy Chinese lossesby American air, armored, and artillery firepower.

On June 18, 1953, the armistice negotiations produced amutually acceptable agreement. However,the agreement was rejected by South Korean President Rhee, and shelved. Taking advantage of the new stalemate, onJuly 6, 1953, the Chinese renewed their offensive, first attacking a UN outpostknown as Pork Chop Hill, which forced the defending American troops of the U.S.7th Division to retreat after four days of fighting, with heavy losses to bothsides.

Then on July13, 1953, in the last major battle of the war, amassive Chinese force of 250,000 troops, supported with heavy artillery (over1,300 artillery pieces), struck at UN positions on a 22-kilometer front,pushing the mainly defending South Korean forces 50 kilometers south andgaining 190 km2 of territory. However,the victory was pyrrhic, as the Chinese casualties numbered some 60,000 troops,compared to South Korean losses of 14,000 troops.

Meanwhile, armistice talks resumed, which culminated in anagreement on July 19, 1953. Eight dayslater, July 27, 1953, representatives of the UN Command, North Korean Army, andthe Chinese People’s Volunteer Army signed the Korean Armistice Agreement,which ended the war. A ceasefire cameinto effect 12 hours after the agreement was signed. The Korean War was over.

War casualties included: UN forces – 450,000 soldierskilled, including over 400,000 South Korean and 33,000 American soldiers; NorthKorean and Chinese forces – 1 to 2 million soldiers killed (which includedChairman Mao Zedong’s son, Mao Anying). Civilian casualties were 2 million for South Korea and 3 million for North Korea. Also killed were over 600,000 North Koreanrefugees who had moved to South Korea. Both the North Korean and South Korean governments and their forcesconducted large-scale massacres on civilians whom they suspected to besupporting their ideological rivals. In South Korea,during the early stages of the war, government forces and right-wing militiasexecuted some 100,000 suspected communists in several massacres. North Korean forces, during their occupationof South Korea,also massacred some 500,000 civilians, mainly “counter-revolutionaries”(politicians, businessmen, clerics, academics, etc.) as well as civilians whorefused to join the North Korean Army.

July 9, 2021

July 9, 1900 – Boxer Rebellion: 45 Christians are killed in the Taiyuan Massacre

On July 9, 1900, forty-five Christians, which included men,women, and children, were killed in Taiyuan, Shanxi Province in northern China at the height of the BoxerRebellion. It was long held that the killings were ordered by Shanxi Provincegovernor Yuxian, who had imposed anti-foreign, anti-Christian policies in theprovince. More recent research indicates that the massacre resulted from mobviolence rather than a direct order from the provincial government.Subsequently, some 2,000 Chinese Christians were killed in Shanxi Province.Also during this time across northern China, Christian missionaries andChinese parishioners were being targeted for violence by the Boxers as well asby government troops.

(Taken from Boxer Rebellion – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia: Vol. 5)

The Boxers In thelate 19th century, a secret society called the ““Righteous and HarmoniousFists” (Yihequan) was formed in the drought-ravaged hinterland regions of Shandong and Zhiliprovinces. The sect formed in the villages,had no central leadership, operated in groups of tens to several hundreds ofmostly young peasants, and held the belief that China’s problems were a directconsequence of the presence of foreigners, who had brought into the countrytheir alien culture and religion (i.e. Christianity).

Sect members practiced martial arts and gymnastics, andperformed mass religious rituals, where they invoked Taoist and Buddhistspirits to take possession of their bodies. They also believed that these rituals would confer on them invincibilityto weapons strikes, including bullets. As the sect was anti-foreign and anti-Christian, it soon gained theattention of foreign Christian missionaries, who called the group and itsfollowers “Boxers” in reference to the group’s name and because it practicedmartial arts.

The Qing government, long wary of secret societies whichhistorically had seditious motives, made efforts to suppress the Boxers. InOctober 1899, government troops and Boxers clashed in the Battle of Senluo Templein northwest Shandong Province. In this battle, Boxers proclaimed the slogan“Support the Qing, destroy the foreign” which drew the interest of somehigh-ranking conservative Qing officials who saw that the Boxers were apotential ally against the foreigners. Also by this time, the Boxers had renamed their organization as the “Righteous and Harmonious Militia(Yihetuan)”, using the word “militia” to de-emphasize their origin as a secretsociety and give the movement a form of legitimacy. Even then, the Qing government continued toview the Boxers with suspicion. InDecember 1899, the Qing court recalled the Shandong provincial governor, who had shownpro-Boxer sympathy, and replaced him with a military general who launched ananti-Boxer campaign in the province.

The Boxers’ grassroots organizational structure made itssuppression difficult. The movementrapidly spread beyond Shandongand Zhili provinces. By April-May 1900,Boxers were operating in large areas of northern China,including Shanxi and Manchuria,and across the North China Plains. TheBoxers killed Chinese Christians, burned churches, and looted and destroyedChristian houses and properties. As aresult of these attacks, and those perpetrated during the Boxer Rebellion, morethan 30,000 Chinese Christians, 130 Protestant missionaries, and 50 Catholicpriests and nuns were killed.

The Boxer movement’s decentralized organization was its mainstrength, as individual units could mobilize and disband at will, and could betransferred quickly to other areas. Butits lack of a unified structure and central leadership were also its weakestpoints, as Boxer units were restricted by a lack of coordination and over-allcommand. Boxers also suffered from alack of military training and adequate weapons, and thus fought at a greatdisadvantage and easily broke apart when the fighting became intense.

By May 1900, thousands of Boxers were occupying areas aroundBeijing,including the vital Beijing-Tianjin railway line. They attacked villages, killed localofficials, and destroyed government infrastructures. The violence alarmed the foreign diplomaticcommunity in Beijing. The foreign diplomats, their staff, andfamilies in Beijinghad their offices and residences located at the Legation Quarter, located southof the city. The Legation Quarterconsisted of diplomatic missions from eleven countries: Britain, France,Russia, United States, Germany,Austria-Hungary, Japan, Italy,Belgium, Netherlands, and Spain.

In May 1900, the foreign diplomats asked the Qing governmentthat foreign troops be allowed to be posted at the Legation Quarter, which wasdenied. Instead, the Chinese governmentsent Chinese policemen to guard the legations. But the foreign envoys persisted in their request, and on May 30, 1900,the Chinese Foreign Ministry (Zongli Yamen) allowed a small number of foreigntroops to be sent to Beijing.

The next day (May 31), some 450 foreign sailors and Marineswere landed from ships from eight countries and sent by train from Taku to Beijing. But as the situation in Beijingcontinued to deteriorate, the foreign diplomats felt that more foreign troopswere needed in Beijing. On June 6, 1900, and again on June 8, theysent requests to the Zongli Yamen, with both being turned down. A separate request by the German Minister,Clemens von Ketteler, to allow German troops to take control of the Beijing railway stationalso was turned down. On June 10, 1900,the Chinese government barred the foreign legations from using the telegraphline that linked to Tianjin. In one of the last transmissions from theLegation Quarter, British Minister Claude MacDonald asked British Vice-AdmiralEdward Seymour in Tianjin to send more troops,with the message, “Situation extremely grave; unless arrangements are made forimmediate advance to Beijing,it will be too late.” And with thesubsequent severing of the telegraph line between Beijingand Kiachta (in Russia) onJune 17, 1900, for nearly two months thereafter, the Legation Quarter in Beijing would be cut off fromthe outside world.

On June 11, 1900, the Japanese diplomat, Sugiyama Akira, waskilled by Chinese troops in a Beijingstreet. Then on June 12 or 13, twoBoxers entered the Legation Quarter and were confronted by Ketteler, the GermanMinister, who drove one away and captured the other; the latter soon was killedunder unclear circumstances. Later thatday, thousands of Boxers stormed into Beijing and went on a rampage, killingChinese Christians, burning churches, destroying houses, and looting properties. In the next few days, skirmishes broke outbetween foreign legation troops, and Boxers with the support of anti-foreignergovernment units. On June 15, 1900,British and German soldiers dispersed Boxers who attacked a church, and rescuedthe trapped Christians inside; two days later (June 17), an armed clash brokeout between German–British–Austro-Hungarian units and Boxer–anti-foreignergovernment troops.

The Belgian legation was evacuated, as were those of Austria-Hungary, the Netherlands,and Italy,when they came under Boxer attack. Bythis time, the Christian missions scattered across Beijing were evacuated, with their clergy andthousands of Chinese Christians taking shelter at the Legation Quarter. Soon, the Legation Quarter was fortified, withsoldiers and civilians building barricades, trenches, bunkers, and shelters inpreparation for a Boxer attack. Ultimately, in the Legation Quarter were some 400 soldiers, 470civilians (including 149 women and 79 children), and 2,800 Chinese Christians,all of whom would be besieged in the fighting that followed. At the Northern Cathedral (Beitang) locatedsome three miles from the Legation Quarter, some 40 French and Italiansoldiers, 30 foreign Catholic clergy, and 3,200 Chinese Christians also tookrefuge, turning the area into a defensive fortification which also would comeunder siege during the conflict.

Meanwhile in Taku, in response to British MinisterMacDonald’s plea for more troops to be sent to the Beijing foreign legations,on June 10, Vice-Admiral Seymour scrambled a 2,200-strong multinational forceof Navy and Marine units from Britain, Germany, Russia, France, the UnitedStates, Japan, Italy, and Austria-Hungary, which departed by train from Tianjinto Beijing. On the first day, Seymour’s force traveled to within 40 miles of Beijing without meeting opposition, despite the presenceof Chinese Imperial forces (which had received no orders to resist Seymour’s passage) alongthe way. Seymour’s force reached Langfang, where therail tracks had been destroyed by Boxers. Seymour’stroops dispersed the Boxers guarding the area, and work crews started repairwork on the rail tracks. Seymour sent out ascouting team further on, which returned saying that more sections of therailroad at An Ting had also been destroyed. Seymour then sent a train back to Tianjin to get moresupplies, but the train soon returned, its crew saying that the rail track atYangcun was now destroyed. Having tofight off a number of Boxer attacks, his provisions running low, realizing thefutility of continuing to Beijing, and nowfeeling trapped on both sides, Seymour called off the expedition and turned thetrains back, intending to return to Tianjin.

Elsewhere at this point, the Boxer crisis deteriorated evenfurther. On June 15, 1900, at the YellowSea where Alliance ships were on high alert, andwere awaiting further developments, allied naval commanders became alarmed whenQing forces began fortifying the Taku Forts at the mouth of the Peiho River,as well as setting mines on the river and torpedo tubes at the forts. For Alliancecommanders, these actions threatened to cut off allied communication and supplylines to Tianjin, threatening the foreignenclave at Tianjin and Legation Quarter at Beijing, as well as Seymour’sforce. The foreign alliance had had nocommunication with the Seymourforce for several days. Alliance commanders thenissued an ultimatum demanding that the Taku Forts be surrendered to them, whichthe Qing naval command rejected. Earlyon June 17, 1900, fighting broke out at the Taku Forts, with Allianceforces (except the U.S.command, which chose not to participate) launching a naval and ground assaultthat seized control of the forts.

July 8, 2021

July 8, 1960 – U-2 pilot Francis Gary Powers is charged for espionage by the Soviet Union

On May 1, 1960, a United States U-2 spy plane piloted by FrancisGary Powers was shot over Soviet airspace by a Russian missile. Power’s mission, directed by the U.S. CentralIntelligence Agency (CIA), was to take surveillance photographs on anoverflight over central Russia.

Powers survived by parachuting to the ground where he wasarrested by Soviet authorities. The U.S. government of President DwightD. Eisenhower initially stated that the plane was a NASA research plane butlater admitted that the U-2 was conducting surveillance of Soviet territoryafter the Soviet government produced the captured pilot and evidence of theplane’s wreckage, and more important, surveillance equipment and photographs ofSoviet military installations taken during the flight.

Subsequently, Powers was convicted of espionage and sentencedto ten years in prison. He did not servethe full sentence but was released in February 1962 on a prisoner exchange “spyswap” agreement between the American and Soviet governments.

Following the 1960 incident, the United States made changes to policy,procedures, and protocols regarding surveillance and reconnaissance missions.Subsequently, the U-2 was used in overflight missions in Cuba when in August 1962, the firstevidence of the presence of Soviet nuclear-capable surface-to-air missile (SAM)sites were detected on the island, which sparked the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Background of theCuban Missile Crisis After the unsuccessful Bayof Pigs Invasion in April 1961(previous article), the United Statesgovernment under President John F. Kennedy focused on clandestine methods tooust or kill Cuban leader Fidel Castro and/or overthrow Cuba’s communist government. In November 1961, a U.S. covert operationcode-named Mongoose was prepared, which aimed at destabilizing Cuba’s politicaland economic infrastructures through various means, including espionage,sabotage, embargos, and psychological warfare. Starting in March 1962, anti-Castro Cuban exiles in Florida,supported by American operatives, penetrated Cuba undetected and carried outattacks against farmlands and agricultural facilities, oil depots andrefineries, and public infrastructures, as well as Cuban ships and foreignvessels operating inside Cuban maritime waters. These actions, together with the United States Armed Forces’ carryingout military exercises in U.S.-friendly Caribbean countries, made Castrobelieve that the United Stateswas preparing another invasion of Cuba.

(Taken from Cuban Missile Crisis – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

From the time he seized power in Cubain 1959, Castro had increased the size and strength of his armed forces withweapons provided by the Soviet Union. In Moscow,Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev also believed that an American invasion wasimminent, and increased Russian advisers, troops, and weapons to Cuba. Castro’s revolution had provided communismwith a toehold in the Western Hemisphere andPremier Khrushchev was determined not to lose this invaluable asset. At the same time, the Soviet leader began toface a security crisis of his own when the United States under the North Atlantic Treaty Organization(NATO) installed 300 Jupiter nuclear missiles in Italyin 1961 and 150 missiles in Turkey(Map 33) in April 1962.

In the nuclear arms race between the two superpowers, the United States held a decisive edge over the Soviet Union, both in terms of the number of nuclearmissiles (27,000 to 3,600) and in the reliability of the systems required todeliver these weapons. The Americanadvantage was even more pronounced in long-range missiles, called ICBMs(Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles), where the Soviets possessed perhaps nomore than a dozen missiles with a poor delivery system in contrast to the United States that had about 170, which whenlaunched from the U.S.mainland could accurately hit specific targets in the Soviet Union.

The Soviet nuclear weapons technology had been focused onthe more likely war in Europe and therefore consisted of shorter rangemissiles, the MRBMs (medium-range ballistic missiles) and IRBMs(intermediate-range ballistic missiles), both of which if installed in Cuba,which was located only 100 miles from southeastern United States, could targetportions of the contiguous 48 U.S. States. In one stroke, such a deployment would serve Castro as a powerfuldeterrent against an American invasion; for the Soviets, they would haveinvoked their prerogative to install nuclear weapons in a friendly country,just as the Americans had done in Europe. More important, the presence of Sovietnuclear weapons in the Western Hemisphere would radically alter the globalnuclear weapons paradigm by posing as a direct threat to the United States.

In April 1962, Premier Khrushchev conceived of such a plan,and felt that the United States would respond to it with no more thana diplomatic protest, and certainly would not take military action. Furthermore, Premier Khrushchev believed thatPresident Kennedy was weak and indecisive, primarily because of the Americanpresident’s half-hearted decisions during the failed Bay of Pigs Invasion in April1961, and President Kennedy’s weak response to the East German-Soviet buildingof the Berlin Wall in August 1961.

A Soviet delegation sent to Cuba met with Fidel Castro, whogave his consent to Khrushchev’s proposal. Subsequently in July 1962, Cubaand the Soviet Union signed an agreementpertinent to the nuclear arms deployment. The planning and implementation of the project was done in utmostsecrecy, with only a few of the top Soviet and Cuban officials being informed. In Cuba, Soviet technical and militaryteams secretly identified the locations for the nuclear missile sites.

In August 1962, U.S.reconnaissance flights over Cubadetected the presence of powerful Soviet aircraft: 39 MiG-21 fighter aircraftand 22 nuclear weapons-capable Ilyushin Il-28 light bombers. More disturbing was the discovery of the S-75Dvina surface-to-air missile batteries, which were known to be contingent tothe deployment of nuclear missiles. Bylate August, the U.S.government and Congress had raised the possibility that the Soviets wereintroducing nuclear missiles in Cuba.

By mid-September, the nuclear missiles had reached Cubaby Soviet vessels that also carried regular cargoes of conventionalweapons. About 40,000 Soviet soldiersposing as tourists also arrived to form part of Cuba’sdefense for the missiles and against a U.S. invasion. By October 1962, the Soviet Armed Forces in Cubapossessed 1,300 artillery pieces, 700 regular anti-aircraft guns, 350 tanks,and 150 planes.

The process of transporting the missiles overland from Cubanports to their designated launching sites required using very large trucks,which consequently were spotted by the local residents because the oversizedtransports, with their loads of canvas-draped long cylindrical objects, hadgreat difficulty maneuvering through Cuban roads. Reports of these sightings soon reached theCuban exiles in Miami, and through them, the U.S.government.

July 7, 2021

July 7, 1937 – Second Sino-Japanese War: The Marco Polo Bridge Incident takes places

On July 7, 1937, the Marco Polo Bridge Incident became thespark for the outbreak of full-scale war between Japanand China.The Marco PoloBridge (the Western name for the Lugou Bridge)is located southwest of the Chinese capital Beijing. On the evening of that day, Japaneseunits were conducting military exercises near the bridge when exchange ofgunfire occurred between them and the Chinese on the other side of the bridge.Soon after, the Japanese command learned that one of its soldiers was missing(who later returned). A demand to search Wanping for the missing soldier wasrefused by the Chinese. By early July 8, both sides were bringing inreinforcements to the vicinity of the bridge. Fighting soon broke out. Attemptsby both sides to negotiate led to a ceasefire, but ultimately failed to defusetensions. Full-scale fighting then broke out in the capital and elsewhere,starting the Second Sino-Japanese War on July 8, 1937.

In the period before the Marco Polo Bridge Incident,increasing tensions had already existed between the two countries following theJapanese Invasion of Manchuria in 1931 and further Japanese incursions intonorthern China.

Prelude TheJapanese invaded Manchuria in September 1931,gaining control of the territory by February 1932. While the Manchurianconflict was yet winding down, another crisis erupted in Shanghai in January1932, when five JapaneseBuddhist monks were attacked by a Chinese mob. Anti-Japanese riots and demonstrations led the Japanese Army tointervene, sparking full-scale fighting between Chinese and Japaneseforces. In March 1932, the Japanese Armygained control of Shanghai,forcing the Chinese forces to withdraw.

(Taken from Japanese Invasion of Manchuria – Wars of the 20th Century: Vol. 5)

With the League of Nations providing no more than a rebukeof Japan’s aggression,Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek saw that his efforts to force internationalpressure to restrain Japanhad failed. In January 1933, to secure Manchukuo, a combined Japanese-Manchukuo force invaded Jehol Province,and by March, had pushed the Chinese Army south of the Great Wall into Hebei Province.

Unable to confront Japanmilitarily and also beset by many internal political troubles, Chiang wascompelled to accept the loss of Manchuria and Jehol Province. In March 1933, Chinese and Japaneserepresentatives met to negotiate a peace treaty. In May, the two sides signed the Tanggu Truce(in Tanggu, Tianjin), officially ending the war, which provided the followingstipulation that was wholly favorable to Japan: a 100-km demilitarized zone wasestablished south of the Great Wall extending from Beijing to Tianjin, whereChinese forces were barred from entering, but where Japanese planes and groundunits were allowed to patrol.

In the immediate aftermath of Japan’sconquest of Manchuria, many anti-Japanese partisan groups, called “volunteerarmies”, sprung up all across Manchuria. At its peak in 1932, this resistance movementhad some 300,000 fighters who engaged in guerilla warfare attacking Japanesepatrols and isolated outposts, and carrying out sabotage actions against Manchukuoinfrastructures. Japanese-Manchukuoforces launched a series of “anti-bandit” pacification campaigns that graduallyreduced rebel strength over the course of a decade. By the late 1930s, Manchukuowas deemed nearly pacified, with the remaining by now small guerilla bandsfleeing into Chinese-controlled territories or into Siberia.

The conquest of Manchuria formed only one part of Japan’s “North China Buffer State Strategy”, abroad program aimed at establishing Japanese sphere of influence all acrossnorthern China. In 1933, in China’sChahar Province (Figure 32) where a separatistmovement was forming among the ethnic Mongolians, Japanese military authoritiessucceeded in winning over many Mongolian nationalists by promising themmilitary and financial support for secession. Then in June 1935, when four Japanese soldiers who had entered Changpei district(in Chahar Province)were arrested and detained (but eventually released) by the Chinese Army, Japan issued a strong diplomatic protest againstChina. Negotiations between the two sides followed,leading to the signing of the Chin-Doihara Agreement on June 27, 1935, where China agreed to end its political,administrative, and military control over much of Chahar Province. In August 1935, Mongolian nationalists, ledby Prince Demchugdongrub, forged closer ties with Japan. In December, with Japanese support,Demchugdongrub’s forces captured northern Chahar, expelling the remainingChinese forces from the province.

In May 1936, the “Mongol Military Government” was formed inChahar under Japanese sponsorship, with Demchugdongrub as its leader. The new government then signed a mutual assistancepact with Japan. Demchugdongrub soon launched two offensives(in August and November 1936) to take neighboring Suiyuan Province,but his forces were repelled by a pro-Kuomintang warlord ally of Chiang. However, another offensive in 1937 capturedthe province. With this victory, inSeptember 1939, the Mengjiang United Autonomous Government was formed, stillnominally under Chinese sovereignty but wholly under Japanese control, whichconsisted of the provinces of Chahar, Suiyuan, and northern Shanxi.

Elsewhere, by 1935, the Japanese Army wanted to bring Hebei Provinceunder its control, as despite the Tanggu Truce, skirmishes continued to occurin the demilitarized zone located south of the Great Wall. Then in May 1935, when two pro-Japanese headsof a local news agency were assassinated, Japanese authorities presented the Hebei provincialgovernment with a list of demands, accompanied with a show of military force asa warning, if the demands were not met. In June 1935, the He-Umezu Agreement was signed, where China ended its political, administrative, andmilitary control of Hebei Province. Hebei thencame under the sphere of influence of Japan, which then set up apro-Japanese provincial government.

China’slong period of acquiescence and appeasement ended in December 1936 whenChiang’s Nationalist government and Mao Zedong’s Communist Party of Chinaforged a united front to fight the Japanese Army. Full-scale war between China and Japan began eight months later, inJuly 1937.