David Williams's Blog, page 54

December 15, 2016

Seven Ways to Survive a Solar Apocalypse

In my family, we have some apocalypse rules. These vary, depending on the type of apocalypse.

In my family, we have some apocalypse rules. These vary, depending on the type of apocalypse.If it's a pandemic, we sneeze into the inside of our elbows, and hide out inside the house for a month or two. If it's zombies, Dad has a bite-proof armored motorcycle suit, a sledgehammer, and knows to go for the head.

If it's robots? Meaning, an artificial intelligence that arises to challenge humanity after a singularity event? The family rule is this: side with the robots.

Yeah, I know. I'm a species-traitor. But I always did kind of have a thing for the Borg.

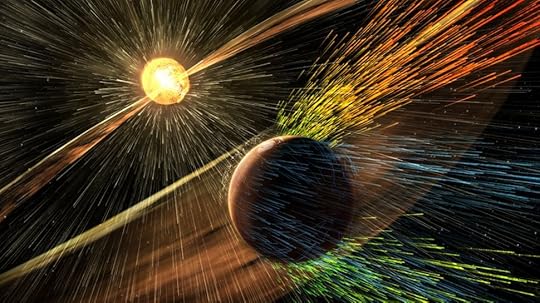

But there are other, less familiar apocalypses, ones that call for different tactics. The question was posed to me, in a phone meeting with my publisher: how would you survive a massive solar storm? My novel When the English Fall examines the impact of such an event. In it, our little world is hammered by an unprecedentedly massive coronal mass ejection, a wave of charged particles from the sun that fries the global power grid, shuts down the net, and compromises most electronics.

It's happened before, way back in 1859, when what's called the Carrington Event damaged telegraph systems, gave folks electric shocks, and put on an astounding auroral display. If a Carrington-scale event happened now, the impacts on our technologically dependent culture would be catastrophic. What would increase the likelihood of our surviving? How could we cope? What would the prospects be for our recovery?

Here for your amusement and survival advantage, I offer a listicle, your seven best ways to make it through that particular civilization-busting disaster:

1) Have emergency reserves.

This is pretty standard, but nonetheless key to most crises. The question, simple: how long could you shelter in place? If you look at your stock of nonperishable food and water, how long could you last? A week? A month? Two days, but only if you include that questionable Chinese food at the back of the fridge that you can't quite remember ordering?

A Carrington scale event might require four to six months to recover, but that first month would be key. Could you and/or your household manage a month with no outside support?

If the answer is, gosh, we just never seem to have food in the house, then you really do need to change it. Canned food, for several weeks. Potable water, and a way to either purify or collect drinking water. A heat source for cooking, with sufficient fuel.

With all electronic records either wiped out or inaccessible, we'd likely revert temporarily to a cash economy. Your credit card/debit card/Applepay? Utterly useless. Having cash on hand as a reserve would be useful...assuming our culture maintains enough trust in one another that'd anyone would still take it.

And no, gold doesn't count, for all of the right-wing pseudo-prepper sites that pitch it in the event of currency collapse. I mean, sure, you can stock up on the bullion and krugerrands if you want. But when push comes to shove, gold won't be worth its weight in Chef Boyardee.

2) Keep physical records.

Our new net-economy creates all sorts of wonderful forms of connectivity, all of which would go away if our communications infrastructure was critically compromised. That means no access to records, no evidence of your bank balance. Full recovery from a Carrington-scale event would be a matter of nine months to three years, after which, what?

If everything you do is online, where would be the evidence of your culturally-held resources when things clambered their way back into normalcy?

So print a couple of things out, so you'll be able to prove you have those accounts.

And have a few books on hand that tell you how to do things. You know, books? Those analog repositories of knowledge that operate independently of any external power source?

On your shelves, have books that describe survival basics, simple horticulture, and first aid. Maybe a map or two. Those will be remarkably helpful. Can you eat that mushroom? How do you stitch up a wound? You'll need to know those things, and Google won't be around to help.

Plus maybe a novel or three, just to take your mind off of things for a while as you read by candlelight.

3) Store a generator and key emergency electronics in a Faraday cage.

If you surround a carefully selected cache of vital electronics with a Faraday cage (a grounded structure of metal), it will channel the energies of an electromagnetic event into the earth. That's be true for solar events, extra-solar energies (like a near-space supernova or a burst of focused energy from two colliding neutron stars in our galactic neighborhood), or a localized electromagnetic pulse from a nuclear device.

So find a place in your basement, take a bale of chicken-wire, some metal posts and grounding screws, some copper wire, and a drill, and then...

"I'm not going to do that," you say. "That's nuts." Well, fine.

That one's a little overly preppery, I'll admit, bordering on tin foil hat levels of survival paranoia. But it would be efficacious. Are you sure that you wouldn't even consider...

Right. OK.

Here are a few more that are...less nuts. Let's go attitudinal.

4) Cultivate an attitude of resilience.

We are an increasingly fragile people, torn by the empty anxieties and induced stresses of our consumer culture. That level of emotional vulnerability would nontrivially reduce our capacity to survive any catastrophic event. The sturdier we are personally, the more likely we are to be able to deal with eventualities in a level-headed way. Panicking or freezing up? We'd be SOL. Focusing our energies on complaining about how unfair this all is to us or on our feelings? Again, that does you not a damn bit of good.

If you're used to demanding "safe space?" Understand this: apocalyptic events are not safe spaces. You can't worry about microaggressions when the whole world is trying to kill you. If you're obsessed with your rights, complaining endlessly about how unfair everything is? The universe couldn't care less.

What you need to survive, more than anything else is a strong, integrated, stubbornly hopeful sense of self.

In studies of survivors, that's the most powerful shared trait. Survivors just believe, resolutely, that they're going to make it. Then they work towards that goal. That belief doesn't guarantee you won't bite it. But if you give in to despair or panic, you significantly increase the probability you aren't going to make it through a crisis.

Faith, in other words, can be a powerfully beneficial adaptive trait in a crisis.

5) Know how to do something.

Personal competence at the things that matter helps. And by this, I mean things that speak directly to the act of survival.

Can you repair things, be they electronic or mechanical? Do you know first aid? Could you stitch up a wound? Could you build a fire? Could you build a shelter? Could you find your way somewhere without GPS? Could you find food in a patch of woods if need be? Do you know how to fish? Can you hunt? Do you know how to grow anything, or what forage can be had in the nearby woods?

It might seem overwhelming, given the strange and existentially irrelevant demands that our culture places on us.

But given how many things you do know, it's really not that difficult. You don't need to go the full MacGuyver. Just be really good at one or two useful things. "I can't," you say. "Pish posh," I say.

Just repurpose all of the neurons you dedicate to knowledge of the Kardashians, or any and all data regarding NFL salaries. Boom.

You don't need to know everything. Why? Well, here's why:

6) Know your neighbors.

In the aftermath of a solar storm, social connection would be key. One human being is a vulnerable thing. Ten humans, working together? Much, much stronger. Your skills join with theirs, and the community you create becomes a more robust entity. So you need friends. Real friends.

Meaning, not friends on Facebook. Not Snapchat, or Twitter. Having fifteen hundred Facebook friends and twenty three thousand Twitter followers would mean diddly squat when the net went down. All of the blabbering hyper-immediate irrelevance of our online social lives would cease to have any bearing. What would matter is local connection.

So. Do you have such a place of local connection? Who is your tribe? Are they human beings who live near you? Or are they commuting co-workers who are nowhere near you physically? Are they shuttle-activity-parents you've gotten to know from your kids various obligatory sportsball teams? Those people will be nowhere near when the world falls apart. The people who count are right there around you.

Make a mental map of your neighborhood. Those souls, the folks who you likely don't know, who move like shadows on the periphery of your busy bee awareness? That's your crisis team.

Yeah.

You've probably got work to do.

7) Continue to support space science and observatory infrastructure.

This is the biggest...and most counter-cultural...one. Honestly, the best way for modern-era humanity to survive a solar storm is supporting science. This flies against our 'Murikan tendency to view survival as an individual thing, as a rugged loner or pioneer family wins out against all odds.

But for cosmic events, the response needs to be at a national or global level. It requires a sense of common purpose.

That is where we are now. An array of probes and satellites currently provides us with significant advance warning in the event of a major solar storm. NASA and other international space agencies maintain a constant eye on the star we orbit, both to better understand it and also to give advance warning in the event of a major solar event.

With those resources in place, we'd have a chance to prepare. We'd have advance warning to unplug devices, to shut down and secure sensitive equipment. It's the cosmic equivalent of getting alerts from the National Hurricane Center. If you have three days to prepare for a Cat 5 Hurricane, the outcome is different than if it just roars up in the night. It'd be the difference between Katrina and the 1900 Galveston hurricane. Both were devastating, but one massively more lethal, with the difference being the time given to prepare.

One of the assumptions in my novel is that America has allowed both our transportation infrastructure and our space infrastructure to degrade. Solar missions have a limited lifespan, and they're not cheap. And infrastructure isn't "sexy." We neglect it to our peril.

If we don't see the value in science, or we allow ourselves to drift down the rabbit hole of technological regression, we're vulnerable. Good thing we have an administration and a Congress that understands the value of science, right?

So. There you go. Your seven handy-dandy tips for survival in the event of a solar storm. Good luck!

Published on December 15, 2016 04:43

December 13, 2016

Jesus, Shammai, and Divorce

As my adult ed/sermon series on the Sermon on the Mount continues, my class ran into the portion of that challenging, essential text that always comes as a gut punch.

As my adult ed/sermon series on the Sermon on the Mount continues, my class ran into the portion of that challenging, essential text that always comes as a gut punch.It's Jesus, talking about divorce. Just a couple of verses, sandwiched in between telling his listeners to be faithful in their relationships, and not to lie, but it still hits hard.

Divorce, Jesus says, should not happen, not unless there is infidelity involved. Then and only then may a husband leave his wife. Doing otherwise creates sin in both parties, Jesus says. He is not gentle about it.

I've read this passage before, and interpreted it in preaching. But I didn't do that again this Sunday, because I've found it's not the kind of thing you can just preach at people without offering the opportunity to talk about it. I've watched as the good souls I know who've gone through the pain of divorce responded. Seen that twinge, as if I'd just administered a mild electric shock. And then me, up there, trying to interpret Jesus, but without the insights and reflections of their stories.

So we talked about it in class instead, about how hard that teaching felt. We talked about how divorce functioned in the context of a radically patriarchal first century near Eastern society, about the impact it had...disproportionately...on women. And how in placing a radical demand on his male listeners to fidelity in relationships, Jesus was speaking up for the powerless in his culture.

But I had another minor revelation, as I studied. I realized, in my own preparation to teach the class, that I was...with Jesus...for the first time agreeing with Rabbi Shammai.

Two great proto-rabbinic schools of thought shaped first century Jewish study of Torah. There was the strict conservative school of Shammai, and the liberal school of Hillel. Jesus almost always comes down on the side of Hillel.

Take, for instance, the old Jewish tale of the student who wanted to know if the law could be summarized in a single sentence. He goes to Shammai, and asks, rabbi, I'm a little thick in the head, can you summarize Torah for me in 140 characters or less? Shammai was enraged at his insolence and stupidity, and drove him away with a stick. The same student...now a little bruised...went to Hillel. Hillel smiled, and said, "Love God with all your heart and mind and soul, and your neighbor as yourself. All the rest is commentary."

This sounds familiar, eh? Hillel and Jesus tended to go the same way.

Except when it came to divorce.

There, the liberal school of Hillel suggested that a man could divorce his wife for any reason. If he displeased her, she was out. "Even if she just burns dinner," went the formulation, with a bit of a wink. This, of course, consigned the woman to a place of social approbation, rejected by the family of her husband, separated from her own, and without any means of providing for herself.

Shammai, on the other hand, argued that you cannot break that commitment lightly. You have a duty to that relationship, one that cannot be broken on a whim.

The paradox, here, is that Shammai's strictly disciplined interpretation would have, in practical terms, ended up being functionally more gracious...particularly to those who found themselves lacking both a Y chromosome and power.

Liberal though I may be, it was a helpful reminder that justice and mercy sometimes may reside outside of my own way of thinking.

Published on December 13, 2016 06:11

December 2, 2016

The Nuclear Codes

It was one of those things I kept wishing people wouldn't say.

It was one of those things I kept wishing people wouldn't say."You can't let him near the nuclear codes," went the refrain. "If you can't trust him with a Twitter account, how can you trust him with the nuclear button?"

My take was and is a little different.

Imagine, for a moment, that America had been foolish enough to give an erratic narcissist access to our nuclear arsenal.

What are the odds they'd get us into a civilization-ending nuclear exchange?

My thought: the odds are marginal. It ain't gonna happen.

Why? Because nuclear war is a zero sum game. Both sides lose. The goal of the con-man and the narcissist is to win and profit at your expense, not to die. Unlike a zealot or an ideologue, their survival matters more to them than anything else. If you're a kleptocrat, you realize that the Wasteland isn't quite as lush pickings as a semi-functioning, gullible, and non-irradiated society. If you're into real estate in major urban areas, nukes have a tendency to reduce the value of your holdings.

And if you're all buddy-buddy with the Rooskies, and likely eager to plant a few branded casinos in gambling-addled Shanghai, going toe to toe the other nuclear powers doesn't serve any purpose.

Yet the case was made, over and over again, that he'd get us all nuked. As a talking point, that felt...stale. Old. That was a cold war fear, existing now in the realm of the childhood nightmares of aging Gen-Xers, an abstraction for most Americans.

Mushroom clouds aren't my primary concern for America's near term future.

What seems far more probable is a good old fashioned shooting war. Most likely with Iran, as I read it, particularly with folks like Flynn and Mad Dog at the helm. As Mad Dog puts it, war is a thrill, after all.

Getting that going will be easy. We come up with justification, provoke a Gulf-of-Tonkin-style "incident," wave flags and fill the right-wing media with good old fashioned jingo, and then in go the children of the poor, the sons and daughters of the Red States.

It's not ICBMs flying, sure.

But when it's your son or daughter coming back in a flag-draped coffin, it may as well be. For those families, for those mothers and fathers and children, the loss of that soldier in a war that serves no meaningful long term national interest might as well be a nuclear exchange.

When our children's bodies are laid into the ground, our world comes to an end, just as surely as if the whole world had come to an end.

So strange, in a nation that is weary of the familiar bloody banality of endless war, that this never quite came up.

Published on December 02, 2016 07:06

December 1, 2016

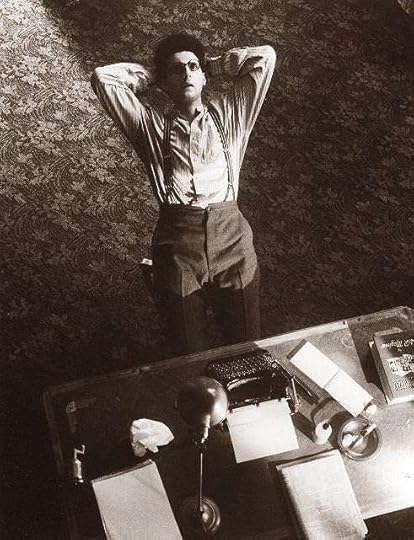

Everything Wrong With My Novel

Writers are anxious people. Or maybe they're not, generally. I don't know enough of them to have a representative sample.

Writers are anxious people. Or maybe they're not, generally. I don't know enough of them to have a representative sample.But I am.

I worry and fret over concepts, over how a thing works or does not work. There'll be a great rush of creative energy, and then, the final product before me, I'll start picking and scratching at it. What if this doesn't work? What if this is useless and pointless? Have I erred? Am I a fool and an idiot, so lost in my own dreamings that the universe itself can't help snicker at me? Am I getting this all wrong, on some fundamental level?

So. Here are my anxieties about When The English Fall, which will be my first published novel, categorized for your schadenfreude:

1) The science of solar storms. The key, transitional, apocalyptic moment of the novel is what appears to be a solar storm, one modeled after the Carrington Event of the late 1850s. The Carrington Event...the largest observed solar storm of the modern era...was an impressive thing. Telegraph systems were blown out. People touching metal farm equipment were given electric shocks. The resultant aurora were so bright that people came outside, thinking the sun had risen. It was a big deal, and would be a major concern in our technological society. That sort of catastrophic coronal mass ejection would completely devastate our vulnerable electronic systems. Our power grid and the internet would be significantly compromised. It'd be a big deal, one that we're unprepared for as a global culture.

But would it have the extreme effects outlined in the book, which are largely modeled after the localized electromagnetic pulse effects of a nuclear blast? That's not clear. Aircraft, vehicles, and grounded systems might not be impacted as substantially. Energies could have to be an order of magnitude higher to confidently project those effects. Could a Super-Carrington occur? Maybe. But my inner Bill Nye has lingering questions about whether the G-type main-sequence yellow dwarf our planet orbits is capable of that kind of violence.

What science does show us is that such an event...as described, precisely...is entirely possible. It might not come from our sun, but from extrasolar activity. A nearby supernova or a burst of energy from the collision of two neutron stars in our galactic neighborhood would have catastrophic impacts that would equal or exceed what's described in the book.

We and our tender little jewel of a world are very, very small and breakable in the vastness of Creation. That said, I'm sure some INTJ out there will roll their eyes and write a long and meticulously scathing review on Goodreads.

2) Lancaster County, PA. I've taken liberties with the geography, in ways that anyone who lives in and around Lancaster would recognize. I've been to the area, and gotten the lay of the land, more or less. I've walked the town, stood in fields, puttered down roads on my motorcycle. I've pored over GoogleMaps to map out movements and sightlines.

But I do not know the area in the way that you instinctively know a place you've lived. It's "sort-of-Lancaster." And sort of not, with the difference being driven by the needs of the narrative.

On the one hand, my perfectionist self is slightly embarrassed by this. Surely, surely, it could have been more perfect. On the other...well...it's creative license. And I don't want this to seem like I'm calling out one particular Amish community, because it's not.

Which gets to area of fretting number three:

3) Amish Culture and Folkways. My experience of the Amish is at a point of academic remove. Meaning, I've read up on them, and not just on the interwebs or wiki. I've studied the best academic ethnographies of their communities, both on my own and as part of a formal academic course of study. I've read literature written by Amish voices, listening carefully to tone and perspective. I've done everything in my power to accurately represent the dynamics of that life. I have an informed take.

But I've not lived it. As a writer and a Presbyterian pastor and a doctoral student and a stay-at-home Dad shuttling kids to and from swimming and drums and afterschool activities, I didn't have the time or the bandwidth to go and live with the Amish.

"Hey, honey, can you get them to rehearsal this evening? I'm going to go live amongst the Amish for eighteen months." One does not say that to any wife one wants not to become an ex-wife.

I also wasn't sure if it would have been a good thing.

First, because the Amish honestly don't like that attention. They don't want to be viewed as a curiosity, to be observed and analyzed and photographed, tagged and released like some peculiar specimen. It can feel, for them, a bit invasive. Their culture lacks our individualistic love of attention, our net-era hunger for fame. Our peculiar obsession with their chosen path can also feel like an invitation to that kind of pride, which is anathema to their way of being.

And second, I'm not sure if that precision would help, given the complex and branching variance in Amish life. There is no one definitive way of being Amish, no single Ordnung. There are, instead, countless fragmentations, each arising from a point of decision in which one community took one path, and a group of dissenters took another.

What I've presented is an amalgam, a community that blends features of various different takes on that fascinating, unique form of life. The core principles are there, and they're as cleanly presented as I can make them. But it isn't perfect.

It'll read wrong, to someone, somewhere.

4) Jacob's Voice. Having read Amish writings, and with a sense of the journaling in an agrarian context, I took my initial swing at writing what was then called The English Fall in the summer of 2012. It's a first person narrative, and the "voice" in such a telling matters.

About eight thousand words in, I ground to a halt. My first Jacob just couldn't tell the story. It's not that the story wasn't there. It's that he was so simple, so laconic, and so earnest that he wasn't...how to put this...interesting. He didn't play with words, but instead used them simply as tools to record events.

He was too Amish, too plain. He was too much like a 19th century farming ancestor, whose diaries my family has retained. Every day, my great-great-grandfather wrote entries about livestock, just a sentence or two, marking the relevant memories of the day. When his five year old daughter fell ill with what was likely influenza, he described her decline with the same terseness. A word here. A short sentence there about doctors.

On the day she died, he wrote: "N passed today. What a patient little sufferer." That's it. All he had to say, two matter of fact sentences, about the death of his child. Authentic as it may be, it's hard to build a 54,000 word manuscript on such a voice.

I stepped back, gave it a year, and when I returned, Jacob was different. More...English...in his use of language. More introspective. Perhaps, again, he might not sound right in the ears of those souls who live in Amish communities. But the needs of the telling dictated the dynamics of his voice.

5) The Unknown Unknown. There may be stuff I just don't know I'm getting wrong. There very well could be. Somewhere in there, a fatal flaw, a critical error of continuity and narrative logic that through some terrible twist of fate my excellent editors just...missed. This is wildly unlikely and faintly insane. But this year, wildly unlikely and faintly insane things have happened.

And so, I fret. Guess that comes with the territory.

Published on December 01, 2016 05:48

November 30, 2016

The Prosperity President

What's most fascinating about the election of Donald J. Trump to be our 45th President is that it perfectly mirrors the evolving character of faith in America.

What's most fascinating about the election of Donald J. Trump to be our 45th President is that it perfectly mirrors the evolving character of faith in America.Donald is perhaps the first major candidate to arise from a new and significant force in American Christianity. No, that's not being Presbyterian, because Donald is not one of us, no matter what he says. Frozen chosen he is not. He has none of our procedural rigor, none of our austerity, none of our tendency to overthink things so much that we never quite get around to doing anything.

Overthinking is not a Trumpian characteristic.

He more closely reflects the faith of another corner of the ever changing ecology of Christianity, one that has grown and flourished as the oldline has descended into anxious irrelevance. Because this is not the era of the fading spirit of denominationalism, with its assumptions of civic duty and social order. It is the age of the prosperity preacher.

The Donald is the first president whose worldview aligns with the Prosperity Gospel. When we saw him during the campaign, surrounded by pastors earnestly laying on hands, they were mostly prosperity preachers. When we heard a faith leader earnestly asserting that the Donald had found the Lord, she was a name-it-and-claim it televangelist.

Sure, he dabbled about with biblical fundamentalists and more traditional evangelicals, understanding that he can single-issue their support. All he had to do was suggest that he opposed abortion, and their votes were his. But he is not part of that stream of faith, and traditional conservatives know it. He's an aging billionaire playboy who made a significant portion of his fortune from casino gambling, an unrepentant serial philanderer who cares about scripture in the same way he cares about anything you have to actually read.

His appeal, frankly, is the same appeal as the well-dressed pastor who strides across the stage of a 10,000 seat auditorium, who shows up to church in his Bentley or S-Class, and who lives in a house twenty times the size of the homes of his flock.

This frustrates the bejabbers out of those of us who've actually studied what Jesus had to say about wealth and how Jesus-people should live their lives, but as much as we cry out "charlatan" and "huckster" and "fraud," our words cannot compete with the sparkle of a well-played con.

Look at his success, they say. He must know something. Listen to what he says, they say, as he confidently tells them exactly what it is they want to hear.

Just want it, the pastor says. All you have to do is really want it, and it will magically happen. Just pray and want it, and give me both your hopes and your treasure as a sign of your faith.

In those churches, the guy up front does very, very well for himself.

Published on November 30, 2016 06:00

November 11, 2016

The Angry White Man and the System

Yesterday it was midday on a November Thursday, and I had walked to the store to pick up a few things.

Yesterday it was midday on a November Thursday, and I had walked to the store to pick up a few things.At mid-day on a Thursday, the crowd at the grocery store is...different. A smattering of moms, their little ones ensconced in their cart seats, little legs dangling. There's a whole bunch of white hair, moving slowly, leaning on their carts for support.

And there are men. Forty and fifty somethings, dressed in ways that say they have no reason to care about how they look during the day. Shoes, a mess. Old, threadbare jackets covering stained shirts mismatched with ill fitting pants.

Meaning I fit right in.

I filled my basket, and wandered over to the short line at the self-checkout, the machines that simultaneously let large grocery chains hire fewer workers and open up the option of not ever, ever talking to another human being face to face.

In front of me, a man. A white man, maybe seven years older than I. Salt and pepper hair, unwashed, uncombed. A mustache and chin grizzle. He seemed agitated.

I know the routine. Plug in your card number, the machine prompts you, first thing. He was trying to get through that stage, jabbing at the screen with his index finger.

It wasn't working. He muttered, angrily, and tried again, jabbing harder.

Touchscreens being what they are, that didn't have the desired effect.

"[Fornicate]," he said, not quietly. He tried again, now pressing hard enough on the screen that if it had been flesh, it would have left a bruise. It didn't work. "[Fornicate]," he said, again, his voice raised enough that heads turned.

And then he balled his hand into a fist, and punched the screen. Hard. The employee responsible for the self-checkout, an older black man, looked faintly uncertain as to what to do, and not eager to intervene.

The angry man snatched up his basket and stormed off to one of the regular lines.

"[Fornicating] thing doesn't [fornicating] work," he said to me as he left.

I took my place at the machine. The screen wasn't cracked. I tested it. It was still working. I plugged in my number, gently. It took two tries, as it often does. But it took.

I finished my transaction, and loaded up my backpack.

When I left the store, the angry white man was at the back of the line, rocking slowly back and forth, eyes unfocused, staring off into the distance.

Published on November 11, 2016 06:41

October 21, 2016

The Profile of the Despot

Yesterday, as the nagging, snarling cough that has made the last week of my life unpleasant finally abated, I went down into the basement workout room/workroom/place to store random [stuff]. Finally, finally a chance to lift weights without sounding like a TB victim.

Yesterday, as the nagging, snarling cough that has made the last week of my life unpleasant finally abated, I went down into the basement workout room/workroom/place to store random [stuff]. Finally, finally a chance to lift weights without sounding like a TB victim.But while down there, I became distracted by something in a box that I was putting back where it belonged. It was a box filled with the old comic books I inherited from my uncle. Mingled in with them, I found an old magazine. It was "Current History," which is still published today. This particular issue, however, dated from July of 1928. It contained a collection of essays about the world events of the day. There were some pro-and-con back and forths from activists and constitutional lawyers about the Prohibition. There were articles about global politics, and some writing about the upcoming election.

More fascinating still : a long reflection on a major global political figure of the day, written by an Associated Press journalist. It is a character study, the observation of a seasoned journalist who had spent decades observing both the country in question and that leader in particular, and sought to report on this fascinating figure to an American audience. What was he like, as a human being? What drove him? What are his demons? Why was he so successful?

I read through the article, noting the key features of this historical figure's character. From that snapshot in history, some of the quotes seemed particularly...relevant:

He is intuitive, but not profound; he has tremendous exploitative and organizing ability, but puerile analytical powers; he is forceful, but inconsistent; impetuous and at times incoherent, he is intelligent, but has no intellectual gifts...

Here is a perfect extravert, a man always moving into his environment, never into himself, taking and transforming, but never giving. He has no friends, no allies, no collaborators. He is alone on [his] plane. All others are lower, aides or assistants.

[He] has little power of concentration...by nature a man fitted only for action, loves the boom and blare of new starts as much as he loathes the boredom of the less sensational later steps....His activity has the regular irregularity of certain fever charts. A new "stunt" every fortnight or month, to be abandoned soon afterward through boredom, a change in adviser or greater interest in the immediately following project.

One of [his] seldom contested claims to fame, if not to greatness, is his apparently inexhaustible vitality, his constant and tireless activity...his working day is seldom less than ten hours. Often it exceeds eighteen.

He is a master at posing whether before one, a thousand or a million watchers. His skill is tremendous and seldom fails him. His bag of tricks is inexhaustible. Perhaps it is true that he acts to satisfy the appetite for drama and melodrama of the...people. Unquestionably millions of persons...are captivated and disarmed by his consummately effective histrionics.

He adores publicity and gloats openly, childishly, in the interest he produces.

[He] is simultaneously profoundly suspicious of flattery and tremendously susceptible to it. His vanity is colossal.The year, again, was 1928. The leader? Not Hitler. Not at all.

The journalist was the Associated Press reporter from Rome, and the personality he was describing was Benito Mussolini.

"Those who do not know history," as the saying goes.

Published on October 21, 2016 07:42

October 20, 2016

The Peaceful Transfer of Power

This last Saturday, my wife and I went for a long walk with our dog.

This last Saturday, my wife and I went for a long walk with our dog. It was a strikingly beautiful day, clear and perfect and touched with the first hints of our late-arriving autumn. And though we've got some beautiful parks and wooded paths near our little suburban rambler, we got in the car and drove.

Our destination: the lovely fields and forests of a nearby National Park, the park set aside as sacred ground to remember the first and second Battles of Manassas. It's a long walk, a whole afternoon, across the varying landscapes over which those battles raged.

On one great sweeping rise, rows of cannon sat silent. A young mother and father, he a person of color, she of European heritage, followed their inquisitive little toddler as he ran free across the field. "Not so far," called the mom, reflexively, but there was nothing to fear. The field went on, and on, and there was nothing more dangerous to a child than soft grass and earth.

In another field, where the grass rose tall and golden, a bright blue Ford tractor pulled a baler, as two farmhands neatly loaded a large wagon with the harvested hay. At the top of the hill, a line of pickups waited, good solid workingman's trucks, hitched to fifth-wheel flatbeds, ready to carry the hay to nearby farms.

The path across the fields brought us to woodland.

Those woods were filled with other Americans, walking and talking in little clusters of two and three. Some were running. At the bridge over Bull Run, a bride in white, flanked by her wedding party, the bridesmaids in surprisingly tasteful blue, a professional photographer and his assistant snapping those hopeful pictures for a future life.

We walked deeper through the shadows of the peaceful wood. And in one place, we came to a sign, which we respectfully read, as we'd read all of the other signs before it.

On it, a quote from a Union officer, describing the movement of his men through that same forest, less than two centuries before.

"We advanced, and the woods were filled with the bodies of the dead."

I looked at the wooded ground around the path, scattered with fallen leaves, and I could see it. I have seen it, in photographs taken of that terrible war.

Young men, no older than my own sons, shattered and cold and broken by grapeshot and musket fire, their bodies stiffening in their own blood. Those old tall trees, so calm and quiet, touched with the remembered cries and stench of death.

So hard to see with your soul, on such a beautiful, peaceful day. So hard to imagine, that such a thing could ever be.

And yet can.

All it requires is for us to forget what violence really looks and feels like, for Americans lost in the dark spell of a demagogue to speak of revolutions and uprising as if they are fanciful abstractions, as if they are a game.

All it requires is for the reality of violent conflict to be glossed over by blithe romantic fabulism and the anger-blindness of our self-righteousness.

All it requires is for us to stop believing in the old good magic of our Constitution, to let cynicism and gossip-whispers tear down the trust and mutual respect that is the bedrock of our civil society.

How easy it is for peace to be broken, when we stop believing in it.

Published on October 20, 2016 07:01

October 14, 2016

Do Not Write an Amusing Caption For This

I saw the picture, and at first captions popped into my mind, because that's what my mind reflexively does.

I saw the picture, and at first captions popped into my mind, because that's what my mind reflexively does.I blame Mad magazine, and MST3K, and, well, my fundamental nature as a mischievous little monkey. I can't see most things without thinking something faintly inappropriate. I am a silly person.

"Wouldn't that be funny," murmured my snarkiness subroutines. "Shareitshareitshareit," hummed the neurons that have been coopted by Mark Zuckerberg.

But then...I couldn't.

The impetus withered and died, because I haven't been feeling quite that way lately. So much of our political life is defined by comedy these last few years, as people behind desks or prowling a soundstage say amusing things about the people vying for the Presidency. Audiences laugh, and it's all in such fun.

And perhaps, perhaps that's comedy as prophetic discourse, comedy at the the thing that skewers our cultural delusions. Comedy can be that. So often, that's a healthy thing.

Perhaps that's comedy as release, as the tension of living in a culture that offers us no sense of shared purpose pours its hive mind dissonance into us. We need to mock, or we would go mad.

There are things that humor helps us approach. Politics is almost always one of them.

But not for me, not now. The political jesters and wags and wits who seek to amuse us with their wry or bawdy commentary do not speak to where I am. I have stopped watching them.

I don't blame them for it. It's not their fault. Perhaps for some, that is still helpful. Maybe it makes this whole mess bearable. I do not judge those who still find they want to laugh.

For me, the time feels wrong.

Like cracking wise at the graveside, when a family has lost a seven year old child to leukemia.

Like making jokes while you explain to a trembling young woman how and why you're going to use that rape kit.

I don't feel like laughing. Not right now, at this strange, surreal, dangerous time in the life of our nation.

Published on October 14, 2016 05:29

October 13, 2016

Forgiveness and Remembering

A few days ago, a friend posed the question:

A few days ago, a friend posed the question:"Where is the balance between forgiving and forgetting? Or should there be any balance at all?I'm having a hard time with this...like God is somehow telling me to completely forgive, and pretend like nothing happened? Is that really what turning the other cheek, and loving unconditionally is about? Are we called to be door mats?"

I was meditating on this question yesterday, as I sat in a tightly packed row at Yom Kippur services. It is the Day of Atonement, the day when the mother tradition to my own faith ends a year and starts another by asking for and offering forgiveness.

We sat and we recited litanies of regret, in English. We listened to them sung in Hebrew, my fingers tracing right to left across the page as the old seminary classes helped me track along through the prayerbook.

It's an important holy day, the holiest of holies, because repentance and forgiveness are at the heart of faith.

Forgiveness is essential for our spirits, but forgiveness itself cannot meaningfully exist if we imagine it requires us to forget our wounds. When we are harmed, we remember that harm. We remember it fiercely and completely, remember it as our flesh remembers sharpness with a scar. We remember it as our gut remembers the scent and flavor of a poison thing that left us retching and dizzy and folded around a cramp-tight belly.

We remember it because remembering harm on a deep gut level is how we were made. It is how we learn. It is how we survive.

When we are hurt, when we are wounded, we are not made to forget.

We Jesus folk, however, are commanded to forgive. It's one of the hardest things we're asked to do as disciples, but everything...everything...rides on it. If we do not forgive, we are not ourselves forgiven.

How does this work? How can this work, when that pain still hurts every time we remember, and that anger still flares?

Here, as I grasp it, it is important to understand that forgiveness does not imply forgetting. As creatures woven from narrative, those moments of pain and trauma are a part of us. When we are hurt, when we are betrayed, when we are lied to and manipulated and abused, we are not meant to forget those moments. We are not meant to pretend nothing happened.

Forgiveness, instead, takes that moment of pain and changes it. It allows us to open ourselves to seeing the sin-blindness of the other, to seeing how their own anxieties and hatreds have driven them to harm us, just as they themselves were harmed and misled.

This does not happen all at once, and it does not happen cheaply. Forgiveness is a discipline, and learning it is neither easy nor simple. It requires us to acknowledge the anxiety and blind rage that rise from those things that have traumatized us.

Having acknowledged those experiences, it then begins to redefine them. That takes time, and intentionality. When we turn the other cheek, the cheek that was struck still burns red from the blow. We are not meant to have forgotten this. Nor can we have.

Because forgiveness is not "being a doormat." It is a fierce demand for rightness in a relationship, one that reframes our reaction towards the possibility of restoration. It is not passive, or acquiescent to injustice.

If it is reciprocal, then even the most broken thing can be healed. If there is repentance, genuine and heartfelt and sustained, then forgiveness can remake anything. That is the heart of the Christian hope. If our forgiveness is not met with a changed heart in the other, the forgiveness remains in our own.

We are not required to stay in intimate relationship with those who view forgiveness as an opening for predation, who seek their own power and pleasure at our expense, who come demanding forgiveness with an unrepentant heart.

Those people, we can still forgive, so that our souls are not filled with a bitterness that will sour our other lifegiving relationship.

So to my friend, I would suggest that yes, we are called to completely forgive, to bathe our remembered pain in that intention, changing not just our understanding of our hopeful future, but helping us to come to terms with our wounded past.

Published on October 13, 2016 06:35