David Williams's Blog, page 28

June 29, 2023

The Recent Rains

The wind has changed

And the scent of far off fire returns

Tickling my lungs

Bloodying the sun

And I am doubly grateful

For the recent rains.

June 27, 2023

Dominion over the Earth

It is a standard refrain, whenever one talks about being both Christian and concerned about our despoilation of this little planet. With an anthropogenic mass extinction occurring all around us, and the basic processes of our global ecology beginning to transition into something more threatening and unpredictable, some of my Christian brothers and sisters choose to resist the adaptive changes that will be required to survive the storm that is coming.

None of those changes pose any threat to our faith, or to a life governed by the central virtues taught by Jesus. Wisdom and thrift, patience and generosity, welcome and mercy, grace and justice? If every Christian lived guided by these traditional Christian ethics, then we might not be in this crisis. If they did now, we would be in a far better place to endure it.

But still, there is a strong counternarrative, born mostly of the idolatrous whisperings of the Mammon-addled, those who serve it above all other masters, those who have been seduced by the world.

"Why should we do what the earth needs," their proof-texted rebuttal goes, "when scripture clearly states that we have been given dominion over the earth? It's right there in Genesis, a foundational assumption of a Biblical worldview. It is for us to rule this world, not for this world to rule us. Power belongs to us, and we can do as we wish to this planet and to those that inhabit it."

This theology is a kissin' cousin of Christian Nationalism, and we generally describe it as "dominionism." Dominionism, in its ecological variant, is the preferred theology of consumer culture, prosperity preaching, and their crass materialism. As such, there's a tendency among environmentally minded souls to push back against the idea in its entirety.

Instead, I say to those who argue we have power over the earth, sure. Yes. You are correct. We have been given dominion over the Earth. Of course. It's both scripture and a clearly observable reality. Point ceded and accepted.

Let us now follow that line of reasoning. If you are a dominionist, you are making that statement as part of your Christian faith, and I am accepting that statement as a disciple of Jesus of Nazareth. I understand my whole life as a commitment to doing as Jesus asks. If I do not do as Jesus asks, then he is not my Lord. I assume, as you and I share that commitment, that you believe that Jesus is Lord.

So the core question, for the committed dominionist, is this: What kind of King was Jesus?

Christians must, if they are meaningfully Christian, understand Godly power and authority as being of a radically different character than worldly power and authority. Worldly power is about control, about the use of coercion to enforce compliance. Worldly power is about greed and selfishness, about the amassing of Mammon. But the power of Jesus is not the brute power of the sword, and not the corrupting power of gold. Those are human things. Fallen things.

Jesus presents us with God's power, a power that both stands above and subverts every sinful human power. It is power in the form of a servant. It is power that kneels and washes your feet. It is power that welcomes the outcast as a sister or brother. It is the power of grace and the power of love. It is the power that heals. It is the power that turns the other cheek. It is the power that overcomes death by dying and rising again. Any interpretation of the Gospel that suggests differently has been corrupted by the world.

When Christians are the subjects of empire, we remain good citizens unto death. We're weird that way. But when we are given the power to rule, as can happen in a republic? Then we're weirder still. The only way Christians can rule is as servants. Profit and control are not our goal.

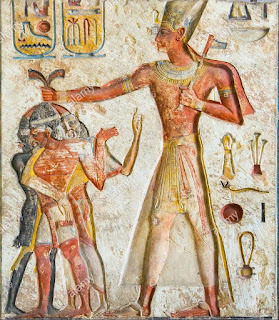

So if we have dominion over the world...which we do, as sentient beings capable of changing our environment...then our dominion must be modeled after Christ's power. Meaning, it cannot be self-serving, or profit-maximizing, or extractive, or destructive. If it is, then we are exercising dominion as Pharoah, as hard-hearted as Ramses. We become Herod. We become Nero.

Again, what kind of King was Jesus? You can't read the Gospel and miss the answer to that question.

Not without trying.

June 26, 2023

Preparing our Souls for Aging - Faith

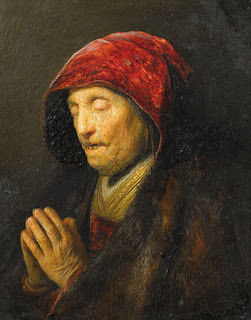

Faith grows more and more important as we age. This isn't just one of those things we Jesus folk put into our brochures, or that we cart out in debates to annoy our atheist friends. It's an observable reality, a testable hypothesis, one that's been noted enough by disinterested observers as to have some theoretic reliability.

Faith grows more and more important as we age. This isn't just one of those things we Jesus folk put into our brochures, or that we cart out in debates to annoy our atheist friends. It's an observable reality, a testable hypothesis, one that's been noted enough by disinterested observers as to have some theoretic reliability.People of faith, particularly those whose beliefs posit a loving, just God? They're consistently happier as they age, with better mental health, better mood and affect, and generally encounter the realities of aging with more resilience. The why of this is fairly straightforward and easy to grasp.

Faith gives life purpose. With purpose and meaning, you can have hope. With hope, you can endure, and Lord have mercy, does aging give us things to endure.

This is all well and good, but it only takes us so far. Unless we have a solid understanding of what faith is and is not, they're kinda meaningless.

Faith is not just believing certain things, not just assenting to one set of truth claims or another. Faith is not a set of logical constructs, woven together to create a framework for understanding the world.

Faith is the orientation of our whole selves, the fundamental commitment that defines us as a person. Faith defines and directs every other action we undertake. It is the core that binds us together, that unifies and integrates all of our other commitments. It is the measure against which we make all claims about the good.

There are other truths about faith, ones that rise from the modern era struggle against meaninglessness.

If faith is the thing that defines us, the goal and orientation of our lives, then it is possible to have faith in the wrong thing. We can choose something that will ultimately come apart in our hands like wet tissue paper, something that will crumble and shift beneath us.

We can have faith in a nation, in its flags and ceremonies, in proud songs and martial prowess and volksgeist. But nations are the work of human hands, and only a people who have forgotten history imagine that they stand forever, or that they are always good.

We can have faith in a single charismatic leader, in their confidence, in their self-professed prowess and projections of strength. We can choose believe everything they say, and set out their flags and banners out front of our home. Again, with the forgetting of history. Why are we so good at forgetting history?

We can have faith in an economic system, or in the structures and expectations and languages of an ideology or a movement. We can have faith in our family and friends, because family is always healthy and friends never let us down. We can put our faith entirely in ourselves, in our strength and the magic that is us. All we need to do is manifest! Manifest the reality we wish to inhabit!

Because you know that just always works.

All of these things are shifting sand. And like the sands of the hourglass, they don't serve us well when our time starts running out. There's a word for what happens when we place all of our faith in something that we've created ourselves. That word is "idolatry."

Faith needs to go deeper, deep down to the ground of things. It's existential and fundamental, something that rests on the depth of the real. Faith that serves us in our endgame must have that deep root, because when we come into encounter with that last stage of life, we've gotten real.

Nations and economies and our social networks are all human creations. They are convenient fictions, stories we are telling together. They exist only because we say they exist, just as the power of a despot vanishes the moment everyone decides he's just another human being.

Aging is utterly different. Aging is not a social construct. It's a biological reality, a truth that exists independent of our languages and norms and expectations. It is as inexorable as gravity, as bright as the fires of the sun, as all consuming as the sea or the endless void of space.

Faith gives us a path, a way to find our footing, and for enduring what is to come. If we're to escape the pall of existential dread and despair, faith...tested, proven, robust, and real...is a mighty fortress. So to speak.

What does that faith look like?

June 25, 2023

There's a Hole

There's a hole

In the boat

Of my soul

That I cannot now repair.

A rending, a mortal crack

through which dark cold flows

I bail, and I strive, and I row

Through the hissing waves

For I know

That finally, tired beyond tired

When I haul up panting

On the firm welcome sand

Familiar-faced fishermen

with work-scarred hands

Will mend that

Hole

In the boat

Of my soul

June 23, 2023

Preparing our Souls for Aging - Hope

Without hope, life becomes so much harder.

Hope, as we commonly understand it, is oriented towards tomorrow. It's what keeps us going when the path of life grows rocky and challenging. "This too shall pass," we say, sagely. "It gets better," says the meme that we share with a friend who vaguebooks about some life crisis they're not comfortable sharing.

When we're struggling through a life crisis, or the sixth month of pandemic self-quarantine, it is hope that keeps us on our feet and moving forward. It's also the attitude of the heart that is most consistently found among survivors of natural disasters or catastrophes. If you're going to pull yourself from the burning wreck of your car and crawl back up that mountainside with a broken leg, you need to believe you're going to make it. Hope keeps you swimming towards the far off light on the shore, though the waves may be high and the water cold.

When we lose hope, we lose so much of our will to carry on.

And therein lies the challenge as we reach the life's final boss battle. Age wins. Every time. It cannot be beaten.

This too shall pass? Well, yes, but when age passes, we pass.

It doesn't matter who we are. You can be the richest man in the world, Steve Jobs with his billions, with access to the most cutting edge black arts of medical science. You can be Elon Musk, whose Neuralink is transparently an effort to create a way to download his awareness into a synthetic neural substrate.

Our bodies age, and while for a time we might become richer and deeper, a perfectly bottled fourteen year old cabernet sauvignon, eventually we become diminished.

In the face of that inexorable reality, it's easy to give in to mindsets that are unconstructive and unrealistic.

We can choose, for our entire lives, to look away. We can lose ourselves in the rush and bustle of life, living only in the moment, not preparing ourselves for the future that will inevitably come. "Live in the now," we say. "That is why they call it the present," says the wizened turtle dude in Kung Fu Panda. But the "now" we claim to inhabit is a chimera, a fleeting illusory nothing that is meaningless without the memory of what was and intention towards what will be.

When age arrives, when our legs have failed and breathing is hard, when our heart struggles in our chest and we can no longer care for ourselves, when adult diapers and Ensure meal replacement drinks are bought in bulk, "living in the now" ceases to be an escape. "Living in the now" can suck when you're standing at the exit of life.

It is our tendency, at those times, to fall back into our past. We can live in a world of memory, continually revisiting what came before, our playlist set forever on repeat. This can be pleasant, for a while, but it doesn't help us come to terms with where we are, and what is coming. It can also become a place of regret and bitterness, as we rehash all that went wrong in our lives. Memory can be a dank and dismal cell.

But what of the future? Hope is oriented towards that which does not yet exist, towards potentials yet unmanifested. Hope for what? For more of the same? For another physical system to fail? For more discomfort? The future, when you are at the end of life, holds nothing more than discomfort and death.

If you hold the attitudes I've articulated over the last four paragraphs, aging will be rough for you. Sure, they might seem "realistic," but they're also radically unconstructive. I have personally always been a pessimist, with a taste for bittersweet chocolate and haunting minor key harmonies. My mom's nickname for me as a little boy was Puddleglum, after the Narnian marshwiggle. I was sure everything was going to turn out badly, that the worst was yet to come.

As I used to put it as a lad, being a pessimist means you're either proven right or pleasantly surprised. Either way, you come out ahead. Or so I reasoned at the time.

If the attitude of our souls is negative, then not only don't we live as long, we also don't live as well.

My mother-in-law Lottie was a fiercely, stubbornly hopeful woman. She loved life and family, and wanted to drink as deeply from that cup as she could. Her Ashkenazi Jewish heritage meant that she'd inherited the BRCA 1 genetic mutation, which makes cancer an inevitability. She fought those cancers...of the breast, of the thyroid, of the gall bladder...for fifty years. Always, always, there was the desire for more life, for more experience, for one more moment of joy. It was the heart of her formidable strength. She fought as hard as a human being could fight, and her hope bought her more joy, decades more joy. Shabbas and Passover meals with a growing family. Travels to far off lands with her husband of nearly 60 years. Grandchildren who all grew up nearby, and on whom she doted and delighted as she watched them become young men and women.

Her last fight was, in a dark irony, against the catastrophic reaction to a new chemotherapy to battle that last cancer. She lacked the enzyme necessary to digest and process the drug, so the poison did not attack the cancer, instead destroying her gastrointestinal tract, her liver, and her bone marrow. Yet still she fought, all the way through that last long impossibly difficult week in the ICU.

Until finally, finally, she mouthed the word "Enough." Hope carried her on to so many joys, as far as it was humanly possible to go.

Yet as powerfully as hope for more life can stir us to seek more moments of joy, there is a deeper hope still.

June 21, 2023

Preparing Our Souls for Aging - Wisdom

To age well, we need to have cultivated in ourselves the habits and disciplines that will increase the likelihood that we will be able to endure what is to come. There's no way out of becoming old, of the decline and failure of our flesh. In the face of that, mindset matters. The objective reality cannot be wished away, but our subjective encounter with that reality can be chosen. For Jesus folk, that means tending to the disciplines of soul that will give us the strength for that season.

To age well, we need to have cultivated in ourselves the habits and disciplines that will increase the likelihood that we will be able to endure what is to come. There's no way out of becoming old, of the decline and failure of our flesh. In the face of that, mindset matters. The objective reality cannot be wished away, but our subjective encounter with that reality can be chosen. For Jesus folk, that means tending to the disciplines of soul that will give us the strength for that season.The first discipline to attend to is wisdom.

With age comes wisdom, or so we tell ourselves as we grow older. "If only I knew then," we say wistfully, "what I knew now." We'd have made different relationship choices. We'd have taken different career paths. We'd have bought Bitcoin at two for a penny. Things like that.

Problem is, that's not wisdom. Simply having access to more data does not make us more wise, any more than having more information at our fingertips has made us all wiser. Sweet Bouncing Baby Jesus, is that not the case.

Wisdom is not about knowing more things. It's about knowing the right path in the world. Wisdom is the understanding of one's place in the scheme of things, of grasping the correct way to be in balance with all around you.

Wisdom, as a Biblical virtue, is a habit of mind, and not the exclusive domain the old. Of course it isn't, given how many old fools there are.

The wise, of whatever age, are measured and moderate. They speak carefully. They understand the impact of their words and actions. They are circumspect, and do not stir passions, nor do they trust their own passion as a guide. They are diligent and thrifty. They seek peace, and make peace where they do not find it. They are faithful to their word, to their commitments, and to their mates.In all of these things, being wise builds resilience, connection and community.

Most importantly, the wise listen and grow. When they're wrong, they learn from it. When a new time requires a new approach, Biblical wisdom marks and understands the season, and does what is mindful. There is a time, the author of Ecclesiastes reminds us, for everything. Wisdom is what guides us as we shift to meet that reality.

When you enter the final season of your life, that habit of adaptivity is hard to maintain. We want things to remain as they always were. We want to be just as able, just as capable, unchanged from our younger selves. When we resist those necessary shifts to accommodate the season, we lay a deeper burden upon ourselves and others.

My first funeral as a pastor was that of an older woman who had for decades been the social glue of her fading church. K was a widow, the matriarch of a longstanding church family. She was a natural hostess, the organizer of countless dinner parties and church social hours. K was well into her eighties, a large woman with a round smiling face and a bright mind. She lived in the same neatly appointed suburban home where she and her long-predeceased husband had raised their children.

As is the case with most wet-behind-the-ears young ministers, I discovered that to visit K was complicated. Every visit, there would be a tray of food set out before me. Little sandwiches. Cookies. All of the things that insure that young pastors add a few pounds in their first year in ministry. K was eager to be my hostess, to welcome me into her home, and I appreciated her gracious hospitality.

But I was also very aware of how hard this hospitality had become. Her knees barely held her, and a lifetime of preparing and loving food meant that her mobility was marginal. She was mostly confined to a single room on the first level of her three level home, having abandoned the upstairs bedrooms and the large basement years before. Getting up to prepare for the pastor's visit was immensely difficult. She would struggle to her feet, forcing herself over to the kitchen counter. I'd offer help, gently, repeatedly, but she'd always demur.

It was her house, and she would never leave it. Assisted living or nursing care were simply not acceptable. Living with one of her children was equally unacceptable. While her family was blessed with the resources to have in home care, she didn't want anyone...untrustworthy...in her house. It was her house, her castle, and she trusted no-one to clean it or help maintain it. She wanted things just the way she wanted them, and no-one could do it quite right. Having someone come live with her was also unacceptable.

"They're going to have to carry me out of here in a casket," she said, a smile on her face. "I lived my whole life in this house, and I will die in this house. Would you like another cookie?"

Family members tried to persuade her to either move or accept help, but she would have none of it. They were there many times a day, almost every day. When I visited, they'd arrive to help her clean up, just as they'd come to help her prepare. Her adult offspring conveyed their exhaustion to me, their worry at how paradoxically fragile and stubborn she was, how her refusal to change her way of life made life harder for her, and harder for everyone around her.

It was not that her desires were of themselves wrong. Not at all. She wished to show hospitality, just as she had always shown hospitality. It's a basic Biblical virtue, as feeding and welcoming and inviting in have been since that day Abram and Sarai welcomed in God unaware.

But there comes a time when welcome takes on another form, and it is wisdom that allows us to perceive the coming of that time.

As we age, our ego fights against acknowledging what changes we must accept, not just for our own well being, but also for the loved ones and care providers who are necessary for our aging well. If we are wise to the way of things, we allow ourselves to step away from that vision of ourselves that no longer matches our reality. We welcome help. We stop pretending we have capacities we do not.

We have to hear Wisdom's voice calling out on the street corner, and listen to her.

June 20, 2023

The Best Mother In Law in the Whole Wide World

Last Tuesday, my wife and I went out for dinner, sitting outside at a little Mexican place, taking a few moments together in a mess of a week. Thirty four years ago, we'd started dating, and though life was hard, we needed to mark it.

Being a peculiar sort of person, I thought there was a good chance I'd marry Rache before I screwed up the courage to cold-call her that summer evening in 1989. When I slowly, awkwardly enunciated my name for her, that was what I left unspoken. The words I said may have been "Hi, this is D-A-V-I-D W-I-L-L-I-A-M-S," but what I was really saying was "Hi, for the last six months I have been readying myself to make this call because I intend you to be my wife." Rache was, at that point, unaware how she'd stuck in my mind, how much she'd made an impression. I called her out of the blue because I remembered every single conversation we'd ever had, the ease of being with her, the rightness I felt every time we'd had a passing moment.

Though the night of our dating anniversary was beautiful, Rache and I were both tired, an anxious pall weighing on us. Her mom Lottie was hospitalized, and in the ICU. She had been deep into a battle with yet another cancer when she had a catastrophic adverse reaction to a new chemo treatment. Despite a ferocious and terrible effort, Lottie passed away just a few days later, reluctantly letting go of the life that had been such a joy.

I was blessed to know Lottie for the thirty four years Rache and I have been a thing, pretty much the entirety of my adult life. There's an assumption, in our individualistic age, that when you choose a life partner it's a binary experience. It's the two of you, locked together in the polarity of Wuv, Twue Wuv, and the rest of the universe may as well not exist. As a romantic, I get that, but the reality goes deeper. When you choose to marry, to do the as-long-as-you-both-shall-live thing, you're not just making a commitment to a lover. You're grafting yourself into their whole web of relationships. The people who are part of their lives will be a part of your life for as long as you both shall live, for better...or for worse. That's kinda Shakespeare's point in Romeo and Juliet, and we all know how that ended.

That first summer when Rache and I began dating, I was attentive to that truth.

A good wife may be hard to find, but a good mother-in-law? That you should have such a blessing. Lottie was the Platonic form of the Jewish mother, for whom family was absolutely everything. She loved and squabbled with and then loved her daughters more deeply still. But to find a Jewish mother in law who loves her goyische son in law, and who supports him when he's called not just to be a committed churchgoing Christian, but a pastor? Who knows from that? Who's heard of such a thing?

Lottie had a boundless interest in things, a desire to experience the world and all that life offered. She was an educator not simply because she loved to teach, but because she valued learning, her encounter with and delight in the new. Classes and books, shows and music and travel to every corner of the globe, she wanted to embrace all of it.

But though the world was filled with newness, the experiences that mattered most were those of family. Lottie wanted everyone there all of the time, to share every moment of life with those she loved, particularly those moments right after your plane landed. She wanted everyone she loved to share their every joy and sorrow with her, to see their every play or performance or fencing match, to read every book, to play every game, to travel in a bustling huddle across seas and in far off lands, to experience it all together.

For three decades, I've been along for that ride, and shared that life with her.

Family was everything, and Lottie and I were family. I could talk with her about anything, share myself freely with her, both in joy and in times of hardship. Her strength was mine when I was broken, and vice versa.

When you take on someone as family, you bring with you your expectations of how that works, and sometimes there are differences. In my very gentile family, for instance, the expectation was that adults all addressed their in laws by name. For Lottie, though, there was an early hope that I might call her Mom. I just couldn't quite say the word, couldn't quite get it out of my mouth. It was not for a lack of love, just that that name was already taken. Just like in Ashkenazi tradition you do not name a child after a living relative, I had someone with that name, and I couldn't get that to work in my brain. Being an anxious twenty-something who was pathologically indirect and conflict averse, there was a period of time there where I struggled to call Lottie anything at all. That wasn't at all awkward. Oy.

But eventually, she was Lottie, because I think both she and I understood her name meant more to me. I could talk with Lottie about anything, share myself freely with her. I knew that she loved me unconditionally, and she knew that I loved her just as deeply and without boundaries. Lottie loved me as a mother loves a son, and I loved Lottie as completely as a son loves their mother.

I was always there for her, in joy and hardship, on adventures and Shabbas evenings, on bright days and holding her hand through that long hard last night she spent in this world.

The word that I said may have been "Lottie," but what I was really saying was "Mom."

Her memory will be a blessing.

June 14, 2023

Preparing our Souls for Aging 1

While we need to tend to our bodies in preparation for the inevitability of age, we also need to prepare our souls.

Because gettin' old is hard on our bodies, but it can be equally taxing on the entirety of our person. Not just our physical being, the peculiar coalescence of star-stuff and ashes that defines our place in the universe, but also the ineffable and unique awareness that rises from our particular physicality.

Our souls can struggle as much as our deteriorating bodies. As we age, and the capacities and competencies of youth and adulthood wane, our sense of ourselves can unravel. Sometimes, that involves the person departing the body well before the processes of organic life have come to an end. My maternal grandmother suffered from dementia. Grandmother was a pretty little woman, full of sparkle and mischief. A fierce competitor on the tennis court, she loved dancing and driving fast. She insisted on being the first one to teach me how to drive, taking me out to tool around in her car when I was thirteen. I noted that this was a few years early, and she'd smile. "I first drove when I was eight," she would say. "I never got a license. Never needed one on the ranch in Texas." She was the sort of grandmother who buys Coca Cola...whole crates of it, in little eight ounce glass bottles from a local distributor...in preparation for the arrival of her grandsons. That, and boxes of Count Chocula and Frankenberry, which were entirely healthy, being part of a balanced breakfast and all.

As she grew old old, what had been interpreted as simple forgetfulness deepened, and her ability to remember whether she'd prepared a meal...or eaten...began to slip away. She still sparkled, moment to moment, for years. In the last season of her life, as the dementia was joined by a slowly spreading cancer, Grandmother faded away. Words vanished. The ability to dress and feed herself evaporated. That body was still mobile, that heart still beat in her chest, but...particularly in those last weeks of life...she was not present. The twinkle had vanished from her eyes. The person we knew had gone.

Alzheimers and other diseases can erase us, or make changes so radical to the flesh in which we have a foothold that we cease to exist as the person we have been. In a former church, I would visit O, a woman of remarkable grace and patience. O was in her nineties. Her husband suffered from Alzheimers, and its impacts on him had been profound. He was still physically able, but his entire persona changed. He'd been a gentle man, thoughtful and quiet, a good husband and father, grandfather and great-grandfather. With the onset of Alzheimers came a change in him. He became angry, violent, and profane, his outbursts mingled with extended periods of incoherence. For his O's safety and those of care providers, he was institutionalized.

She wasn't angry with him. "He's just no longer there," she would say.

There's very little we can do about those impacts on our time in this world. But there are other ways age can impact our souls that we can prepare ourselves to face. Just as certain habits of life can shape the way our bodies age, there are habits of the soul that can ready us to meet the mortal challenges of senescence.

June 13, 2023

Health and Aging

My father's father died when his heart gave out. For years, he'd been nominally on a low-salt diet, which mostly existed in the minds of his doctors. He'd grown up a farmer in upstate New York, and you ate what was in front of you and what tasted good. He was a fierce, sharply intelligent little man with a prodigious appetite, the sort of man who...having grown up hungry and hardscrabble...would eat not just everything in front of him, but food off of your plate if you were slow or distracted. Heck, he would eat food off of the plates left behind at nearby tables in a restaurant. Food must not be wasted.

Low salt? Diet? Those things meant nothing to him. He smoked in moderation, as did so many men of his era. He was fond of bourbon, which as a pastor of a large congregation in New York City was the lubricating oil of many a social gathering. He indulged that fondness until it became something both physically and spiritually toxic. He was tough as nails, but his heart was not, though it carried him into his early nineties before it finally stopped.

My father's younger sister was a vivacious, free-spirited woman, an ample redhead with a brassy lower East Side accent and a genuine easy laugh. She worked, when she worked, as a legal assistant, but her dream...as is dream of so many in that wild rumpus of a city...was the theater. She loved to eat and drink and be merry, and loved the pleasures of life, and eventually there was a whole bunch more of her than her heart could manage. She smoked for a while, because, well, people still did. With weight and a disinterest in exercise came one huge heart attack, one that she barely survived. Her heart and circulatory system struggled for the rest of her life, which she continued to enjoy as much as she could, and a little more than was good for her. Her death came too soon.

My own father's heart is in the process of giving out. He had always exercised vigorously, playing tennis and going to the gym. Despite a lifetime of exercise, he's had multiple open heart surgeries over the last decade. Bypasses. Valve replacements. He'd been encouraged to lose weight, which he did, for a while. And to take a growing list of medications, which he did, diligently. He never smoked. But he paid no meaningful attention to his diet, and shared his father's dark romance with alcohol.

Midway through the COVID pandemic, he started complaining that he was getting short of breath. I tested him, and it came back negative. Then he was struggling to breathe, every exhalation asthmatic wheezing rales. I did a little research, then got him to the hospital. It was, as I had feared, congestive heart failure. To the hospital we went, right in the thick of COVID, which was just super fun. Since then, hospitalization has followed hospitalization, as that progressive disease has slowly closed in around him.

We've fought that for more than a year. We'll fight that to the end.

It's a battle best begun before the enemy is at the gates.

Entire industries have risen up around exercise and diet, as we've simultaneously grown more sedentary and collectively overweight. Farming in the 1920s required just a little more effort than working on the couch from home does today. Heck, it required more physicality than farming today, as mechanized Big Ag rural America has become less and less healthy.

We Americans are trained to live in the moment, as good little consumers must. Food is fast and abundant, fatty and salty, sweetened with corn syrup, perfectly designed to appeal to us on a primal level, a quick hit of empty calories and lizard brain flavor. Our world is oriented towards our convenience, towards ease, towards inactivity.

When we think of caring for our bodies, we are trained to think in terms of a return to youth, or of right now. We want to look good in our swimsuits this summer. We want to be attractive and instagrammable, which I'm assuming is an adjective these days. And sure, if one wants to get theological about it, Jesus did talk about setting aside our fear about the future, about lilies of the field and sparrows and the like. Being anxious about our mortality ain't the Gospel. We are not called to obsess about tomorrow.

But we are also repeatedly reminded to live in a state of preparedness for every moment. Our lives in the right now must be lived with intention, as we acknowledge the likely outcome of any given act, or

How we choose to live our lives impacts how we will age. We know this. Not always, of course. Cancers and aneurysms, car accidents and incoming city-sized asteroids can bring an end to things no matter how well we have lived, or how relentlessly we've focused on caring for our bodies.

"Eat, drink, for tomorrow we die" neglects to consider that, well, no, actually, tomorrow we might live. If we live into hope, then it is our assumption that a probable future will arrive at our doorstep. How we've lived shapes our encounter with that future.

Given my family history of heart disease, this is a daunting truth. It may well prove to be the thing that sets up my first face-to-face with Jesus. Or perhaps it'll be the aforementioned asteroid. I'm not the one who ultimately determines that, but as a sentient being, I do have some input. From the intention of my choosing, I can choose for or against the likelihood of a more vibrant closing chapter to my life.

I've been vegetarian for most of my adult life. There are a range of reasons for this, which I've described in detail in my other writings. It's about a minimization of suffering, particularly the horror of factory farmed meat. It's about treading more lightly on this world. There's also a strong component of enlightened self interest. From all evidence at hand, eliminating meat from one's diet is better for one's heart.

I'm taking my weight and my need for both load-bearing exercise and cardio seriously. Sure, I might be vegetarian, but beer and pizza and Ben and Jerry's New York Super Fudge Chunk Chip are all technically vegetarian. Pastoring and writing are both sedentary vocations. Gaming and reading are favorite hobbies, and neither of those...outside of Dance Dance Revolution or Beat Saber...require much effort. My preference, like my aunt's, would be to just not think about it. But that's a recipe for either a swift death or ...just as likely...a long, difficult, and early old age.

As I carry the familial Scots-Irish taste for whiskey and fermented hoppy beverages, I've forced myself to cut that back. The last thing I need are thirty five hundred empty carbs a week, laced with a substance that actively depresses and suppresses heart function.

These choices are nominally the teensiest bit selfish, all about me and my physical well being. While I am older and able, that will be true.

They are also about my loved ones, who are...assuming I'm not just set out in the woods on a cold night...those who ultimately will care for me. Caregiving is hard work, and tending to myself right now diminishes both the intensity and duration of that care.

Living well does not guarantee that we will age well. Nothing does. But we can increase the probability that we will age well, and it's always the right choice.

June 12, 2023

Of Mysticism and Deconstruction

On the surface of it, there are similarities between mysticism and deconstruction.

Mysticism is, within every one of the great religious traditions of humankind, our universal yearning for union with the Divine Fire. It is the desire to stand so fully in relation with God that you can no longer tell the difference, to lose yourself wholly in the Numinous.

Mysticism affirms the presence of God in every moment, and yet at the same time embraces the fundamental, ineffable mystery of the Holy of Holies. It giggles at efforts to use frameworks and categories and language itself to define God, because human language is utterly inadequate as a means to approach the Mysterium Tremendum. The anonymous medieval mystic text The Cloud of Unknowing put it like this:

For He can well be loved, but he cannot be thought. By love he can be grasped and held, but by thought, neither grasped nor held.

Mystic experience shatters those structures created by the human mind, those labels we apply to the world around us to bind and control it, and those labels we apply to ourselves and others. Perhaps the greatest systematizer of the two thousand years of Christian faith was St. Thomas Aquinas, whose vast Summa Theologica takes up an entire bookshelf in a library. After completing what may still be the most exhaustive and disciplined structuring of orthodox Christian faith ever undertaken, Aquinas had a deep personal experience of the Holy, after which he declared, famously, that the whole Summa was "straw." Worthless. Burnable.

I have a strong mystic leaning myself. My faith has been shaped by moments of inexpressible presence, by dreams and visions that rose unbidden. This isn't really the Presbyterian way, with our decent and orderly lawyerliness and love of procedures, processes, and protocols, but I've always been a weird sort of Presbyterian.

Mysticism, where it manifests within any institutional religion, is almost always viewed as weird at best, and dangerous at worst. Mystics are a little nuts. A little twitchy. They pose a threat to the shared assumptions and orthodoxies that establish boundaries around and within community.

Because of this, there's a tendency among many earnest souls to conceptually conflate the act of deconstruction and the mystic life. I mean, I won't deny some of the parallels. They both take things apart. They both are "reimaginings." They both challenge orthodoxies, shatter literalisms, upend institutions, and subvert human power structures. They both acknowledge the essential limitations of language itself.

So, they're the same, right?

I gently contend that they are not, and for a rather basic reason.

Deconstruction is a work of the human intellect. Mysticism is a work of God.

One is analytical and critical, the other is experiential and prayerful. One rises from academic discourse, the other, from the work of the Spirit. One leads to lament and ashes, the other to peace and joy. One rises from the ego, the other rises from an unmediated ego-death-inducing encounter with the Holy. One dis-integrates, the other integrates.

While deconstruction has its place in the work of critical secular thought, it rises from an essentially different source than mysticism. It bears very different fruit.