David Williams's Blog, page 26

August 18, 2023

Of Enemies and Gardens

When the sun peeks over the low rise to the east on a late summer morning, my garden comes alive.

As the first light streams through the trees and strikes my flowers, the first shift of pollinators and seed-snackers arrives. On the compound surface of the sunflowers, fat bumblebees trundle about, their furry pettable backs sprinkled liberally with pollen. Honeybees from one of the neighborhood apiaries flit from squashblossom to squashblossom, as other tinier indigenous bees visit the delicate flowers of tomatoes and beans.

On my sunflowers, the early birds arrive, rich red cardinals and bright goldfinches sating themselves on the fat and oil of the seeds, momentarily annoying the bumblebees before darting away. The birds are messy eaters, disturbing and dropping as many seeds as they consume, seedfall which will produce a healthy portion of next year's glorious sunflower display.

It's a great rush and bustle of living things, and as I go about my own sunrise weeding, sorting and puttering, I will often pause to admire the simple purposeful industry of it. Each of these little creatures, going about their business, doing what they were made to do. Without them, my own labors would be quite literally fruitless.

In that morning traffic, there are also workers one might not expect.

Like, say, flies. No-one's favorite creature, flies, but there they are among the mint blossoms, pollinating as they move herky jerky across the soft white fuzz of the mint. Their metallic green backs shine lovely dark emerald in the light of the new day, yet another helper bringing life to the garden. Awfully pretty for a [poop] eater, I thought to myself.

As I watched the green flies work, I caught a soft shadow drifting in the herbs, from basil flower to basil flower, as near invisible as a mote of ash, more a hint of movement than a solidity. I focused, and the delicate creature came more clearly into view.

It was an Aedes albopictus, rear legs striped black and white, curled like whiskers. An Asian Tiger. The mosquito that invaded the East Coast late in my adolescence, brought over in shipping containers. A literally mortal enemy, a tribe of voracious day-biters and despised disease vectors.

Also, of itself, harmless. It was a male, which is why it was so slightly built with feathery antennae, a fraction of the size of the females, even more delicate than the bloodthirsty skeeter-ladies that I kill on sight. The males do not bite, do not need my life-fluid to gestate, do not spread itches and tropical ailments. All they do is flit softly from flower to flower, drinking nectar and spreading pollen, and creating horrible offspring with their loathsome women.

I felt a strong, primal urge to bring my gargantuan hands together in a single killing thunder clap.

But in that moment, in the quiet of the morning and the good business of my garden, I did not. Could not, soft-hearted fool that I am. They will not hurt or destroy on all my holy mountain, sang the old prophet's voice in my ear, and I relented.

"Maybe I'll kill you tomorrow, little enemy," I muttered. "But not today. There's enough death in the world today."

August 16, 2023

A New Act

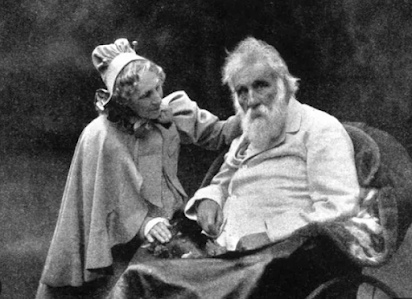

It's been a week and a half since we started Dad on hospice. With his heart failing, his kidneys failing, and the bloodflow to his feet failing, and with no viable long term treatment path for any of those conditions, it was time. He'd made it to his grandson's wedding, made it to the beach for a week of ocean breezes and family, and that meant both of the long term "goals" for survival had been met.

Adapting to that shift has been challenging. The laundry list of medications, now whittled down to only those necessary for his "terminal diagnosis." The complex care doctors and the network of specialists on whom I'd been relying for guidance, now set aside and replaced by a helpline. A helpful helpline, to be sure, but different.

The relentless focus on diet, loosening. We are no longer doing everything possible to keep him alive.

And that's been a difficult transition. My learned instinct, from the last several years of helping with his care, is to be hypervigilant, to be constantly in a state of threat-assessment. If his weight went up, what did that mean? If his BP was too low, was that a concern? If his affect changed, how did we need to respond to that?

Because if we didn't, it might mean death. Mortality was on the line. There was a bright, simple clarity to the purpose of each step along that tightrope.

Now, though? Now things are hazier. We've not given up, or chosen to expedite death. The twofold goal is that he not feel pain, and that he be present for as long as he is present as a person, that there be some pleasure in life.

The challenge is that those two goals are often in tension. Personhood and an absence of suffering often are at odds with one another. He has struggled to sleep at night, and asked for sleep aids to help get him through the night. But those sleep aids have left him drowsier during the day, folded over and drooling onto his shirt, difficult to rouse.

Is he comfortable? Yes. Is he getting pleasure from life, savoring his last chapter? No, not really, not if he's twitching and mumbling incoherently in his wheelchair.

So the balancing act has changed. The threat has changed.

August 10, 2023

Age, Duty, and Transactional Self Interest

There comes a time when there's not much more we can do for others.

So much of our sense of self is woven up with our sense of purpose and productivity, our ability to protect provide, our ability to nurture and organize. Those are the expectations about the value we bring to the world, and also how we understand the value that other human beings bring to the world.

We offer value, and others offer value in return. That's the basic transaction of human social exchange, of our oiko-nomos, the fundamental "house law" of all economic interaction.

When we no longer has anything to offer others, what happens to that exchange?

'Cause at some point, that transaction breaks down. We cease to be able to provide a quid for a pro quo. All we have is need. There are other stages in life when this is true, like when we're in utero, or when we're a squiggly little bup that eats and poops and disrupts our parents' sleep cycle. In those times, though, we've got a future ahead of us. We offer up the promise of future returns. There's an R.O.I. on a baby, or so we tell ourselves as the college bills keep coming in.

But in the last few years of life, we can't provide return on investment. With mobility compromised, and our economic worth diminished, what do we have? For a small privileged minority, what we have are savings, a reserve of economic resources to carry us through the long desert of our senescence. These are imaginary resources, of course, resources that exist solely as a social construct, but hey. You go with what you got.

For the majority, what we will have is the reality of our need. Given that most human beings on this planet do not have large reserves of lucre, what extreme age offers is this: More need, and deepening need, with nothing but need to offer in return for the care we require.

This is where the assumptions and intentions of our transactional culture break down. Another moral framework is needed.

In the book of Ruth, we hear a story that lays out a very different vision of how we are to deal with those who can offer us no material reward when we care for them. A family of Judeans fled the region around Bethlehem to escape a time of famine, and settled in nearby Moab. The two sons both married Moabite women, and for a while, things were stable. But then the father died. Then both sons died, leaving the matriarch Naomi without a husband or male offspring. She was too old to remarry. In the patriarchal culture of that time, that meant that she was utterly bereft. She had no value at all.

Naomi was forced to return to her homeland, with the hope that she might be taken back into the care of extended family. That return offered no guarantees of anything other than poverty and hardship. Knowing this, she tells both of her daughters-in-law that they should return to their families. Both resist, but when Naomi insists they not come with her, only one of them leaves. Ruth refuses. From love and from duty, she will not abandon Naomi. Her assertion of commitment to Naomi is total:

Where you go I will go, and where you stay I will stay. Your people will be my people and your God my God. Where you die I will die, and there I will be buried. May the Lord deal with me, be it ever so severely, if even death separates you and me.

This isn't a transactional relationship, or a relationship that assumes any reward. It's an existential commitment. Ruth's entire identity...her sense of place, her relationships with others and God, and her life itself...is woven up in her commitment to stand by her mother-in-law's side.

Ruth models a relationship of duty, tempered in the fires of love, a willingness to offer up the entirety of herself to another. It's a faith commitment, one that is defining of her person, and cast in terms not of self interest but of covenant.

Where transactional morality fails to offer any grace or hope in aging, covenant commitment succeeds. Does it require sacrifice? Sure. Does it offer an easy path? No. But aging is hard. It will always be hard, as the reality of our mortality is hard. The mealy, indulgent solipsism of consumerism and profiteering offers us nothing to endure that season. For that endurance, we need the fierce strength of purpose that comes from a love as strong as Ruth's.

August 7, 2023

Age, Foolishness, and Wisdom

We don't know what we don't know.

It's a peculiar reality of youth, that moment when we realize that we are no longer children, and look at the world with newly minted adult eyes. We suddenly see things anew, see adults as the flawed human beings that they are, see ourselves with an agency that childhood lacks.

This can be a time of wonder or sorrow, as we encounter everything as if it is freshly discovered. No one has ever seen the world as we see it. No one has ever had the realization we've just had about The Injustice of It All, or the Meaninglessness of Existence, or the Depth of Love.

We are, in other words, fools. I certainly was.

Well, "fool" isn't quite accurate. A better word is "sophomore." The word "sophomore" doesn't simply apply to one's second year at an institution of learning. The root of the word comes to us from two Greek terms. Sophos, meaning "wise." Moros, meaning "fool." With a limited data set defining our understanding of the world, and a shallow pool of lived experience, we extrapolate wildly, making decisions that tend...er...not to be the best.

Being fiercely attracted to people who are in need of "fixing" or "protecting" is one such error. I was, again, such a fool. Passionate? Yes. Well-meaning? Sure. But I didn't know yet how much I didn't know, both about life and myself.

Wisdom comes from listening to life, from a fullness of years in which we have experienced loss and failure, joy and sorrow. It comes from learning from one's own experience, but also being willing to acknowledge that we do not know it all. Wisdom continually learns and adds knowledge to knowledge, continually adapts, continually understands that it is limited, and that the world doesn't center around what you are feeling right now.

Age brings wisdom. Or it doesn't. There's no fool like an old fool, eh?

Still, when a culture stops valuing the insights that age can bring, it forgets itself. It "lives in the moment," showing all the foresight of a fourteen year old boy, and all the emotional maturity of a tween girl. When we imagine our past has nothing to teach us, when we silence the stories of our ancestors, both those passed and still among us, we commit all manner of errors.

Examples of this abound in the Bible, but perhaps none is so pungent as Rehoboam's folly.

Rehoboam, or so the story goes in 1 Kings 11 and 12, inherited the kingdom of Israel from Solomon. Like his father Solomon, the base of Rehoboam's power centered in and around Jerusalem. The relationship with the Northern tribes of Israel was tenuous, both during David's tumultuous reign and the Solomonic consolidation of power. Northern insurrectionists challenged and tested the power of Jerusalem, most notably Jeroboam ben Nabat, who fled to Egypt during Solomon's reign and plotted uprising.

After Solomon's death, a group of representatives from the North arrived at Rehoboam's court, asking that the freshly minted king give them some relief from taxation, levies, and oppression. "Remove this heavy yoke," they asked.

The older and wiser advisors that had served Solomon counseled Rehoboam to show some leniency, to reduce the friction between South and North, and to buy goodwill. They understood that showing grace creates grace, and that yielding and listening are necessary for reconciliation. They also understood that the North represented most of the kingdom, and that there was only so far that they could be pushed before the connection to the power centers in Jerusalem would be severed.

But Rehoboam also had another cadre of advisors, young men who'd grown up with him in the Jerusalem court. They were children of privilege, and filled with the rash aggression that so often defines manhood at that age.

Their counsel was...er..."different." They suggested that Rehoboam should tell the Northerners first that his little finger was larger than his father's loins, a reminder that the Bible can get waaay earthy at times. Then, the young men suggested telling the emissaries that Rehoboam was going to make life worse for them. Make the yoke heavier! Say, "Where my father punished you with whips, I'll punish you with scorpions."

Scorpions. LOL, bro. Scorpions are bussin'. Or groovy. Or hep. Or the bee's knees, depending on what generation of cocky young fool you are.

The voice of age and experience was ignored. The passionate selfconfidence of the young was chosen.

And the kingdom that David had created and Solomon had built collapsed forever. The outraged North seceded, turning to Jeroboam to lead their revolution. That revolt succeeded, and the North left, taking with it the name Israel, most of the people, and most of the wealth.

Any culture that assumes that learned experience is meaningless, and that a long-lived-life has nothing to offer?

The word for that culture? "Sophomoric."

August 4, 2023

Age and Vulnerability

The call came midway through my day, from a dear soul at my prior congregation. N was a remarkably gracious woman, bright and insightful, a retired scientist and one of the longtime bulwarks of a dying church, and when her name popped on my cellphone, I picked right up.

Her voice was agitated, and she needed prayers right away for her grandson. "What's going on?" I asked.

"Well, he's in prison in Mexico," she began, "and he called me because he needed bail money to..."

My anticipated prayers and advice took a different turn, mostly that she might get to Wells Fargo in time to stop the wire transfer she'd just authorized.

Nothing marks the shift into old age like the arrival of scammers. As we become more isolated and less engaged with the broader world, it isn't just that our physical selves become more limited. With that decline comes an increase in our broader vulnerability as persons. It becomes harder to tell when that call is coming from a trusted source, or when that email is legitimate, or when the alert that flashes in your browser isn't actually from Microsoft.

I had a long, long talk with my Dad about that last one, after I'd spent an hour rooting out the malware the "Microsoft Help Desk" person had installed on my parents desktop.

Where once being old meant that you had a familiarity with the world, the relentless pace of churn and change in our culture simply means that your lifetime of developed experience no longer has any purchase. Even in cultures where the elderly were more honored and revered than in our own adolescence-focused society, they were still in a position to be taken advantage of.

The ancient stories of scripture offer up multiple witnesses of age and its weaknesses, of how easily those who seek advantage can take it from the unwary and unprotected old.

Take, from Torah, the way that Eli's corrupt sons took advantage of their heritage, stealing his honor and using their inherited priestly position to help themselves to offerings and women, so shaming him that he took a life-ending fall.

Or again and more sharply in Torah, Jacob's brazen scamming of blind Isaac, Jacob the sly mama's boy, a trickster-archetype, approaching his visually impaired father with masked voice and disguised form, stealing a blessing and a birthright that was not his.

Or Nathan and Bathsheba in 1 Kings 1, working together to gaslight the addled, unwarmable David into supporting Bathesheba's child Solomon over Haggith's son Adonijah.

The weakness of the old makes them easy prey for those who want to take wealth or power for themselves. It makes them just as easy to ignore, or to warehouse, or to treat as something less than a person.

If we view power and strength as the measure of a person's worth, then we are just as prone to diminishing those who are no longer what they once were. We begin to treat the elderly in the same way that the ancient world treated children...like they are not fully human and worthy of treating with decency.

That view of those who are less than fully able is anathema to an authentic Christian faith. Weakness and vulnerability are not to be mocked, belittled, or viewed as an opening for advantage. Those who find themselves without power are precisely the souls that the Crucified One demands that we protect and care for, not in spite of their weakness but because of it.

Because for all the different ways we delude ourselves into believing we will never age, that we ourselves will never be weak or vulnerable? That's as false as Donald Trump's hair. We will all of us eventually be that person, unable to stand on our own, fuddled and lost and a little confused. How we...as persons, and as a culture...treat those who cannot fend for themselves is the measure by which we will be judged.

July 30, 2023

Gathered to Our People

Abraham had a most interesting life. It was, without question, an archetypal and mythic existence in the Joseph Campbell sense of those concepts. His story provides the foundation for a worldview that currently defines meaning for half of the global population, 1.6 billion Muslims and 2.4 billion Christians, and the 16 million or so Jewish souls who carry on that mother faith.

At the end of those stories of his life is the story of his aging and passing.

As the twenty-fifth chapter Genesis/Beresheet tells it, Abraham lived to the ripe old age of one hundred and seventy five, to a "good old age", a b'sayvah tovah zaqen. That age ended with him being, as most translations put in, "gathered to his people." The word that is translated "gathered", or 'acaph, implies every form of gathering. It can mean harvesting, or bringing in, or taking, or being brought together. It can mean to assemble with others.

To be gathered in to one's people is, I would suggest, a marker of a life well lived. For those of us who use Torah as a touchstone for our moral purpose, that connectedness to those around us is a defining feature of a life lived in covenant. It is our hope in aging, because aging ain't easy, and not a one of us wants to do it on their own.

What's striking about this scriptural concept is just how far we are from it as a culture. Age and dying are kept at a remove from us, both materially and as part of our defining narrative. The stories that the old have to tell aren't relevant, aren't relevant to a new generation doing new things. Aging is best forgotten or ignored.

But covenant, like any form of deep relationship, requires more of us. It's a defining commitment, a commitment that frames our self interest in terms of our connection to another. Covenant is what builds community and connection. It gathers us in, all together, an abundant harvest of grace.

It is the antidote to our culture of isolation, to the shattering of community and the blight of loneliness. Like all commitments, it requires effort on our part.

As I write this, I sit next to Dad as he drifts in and out of sleep. Dad's always loved the beach, and summer visits to the seashore have been a part of my life for as far back as I can remember. We're on the screen porch of the Delaware beach house we've rented for the last eight years. Cool breezes come off of the Atlantic, after a night of fierce storms cleared off the heat of the summer. The sound of the waves can be heard over the dunes. The cry of seagulls fills the air, their brassy song softened by association with seasons of pleasure. Fire Island. Mombasa and Malindi. Fripp Island. Brighton and Margate. And Bethany Beach, for the majority of my lifetime.

It was harder this year. Getting him here required effort. A packed minivan full of wheelchairs, oxygen tanks, and an oxygen concentrator. A panoply of medications, neatly sorted for a week away, which we managed to forget in the hurly burly of getting him into the van for the trip. Nothing an eight hour round trip drive back home that first night couldn't cure.

His CHF has worsened as the summer has progressed, his calves now morbidly plump and taut with excess fluid, his dependence on oxygen complete. His breathing is not labored absent the aforementioned oxygen, but any effort at all is difficult. He can no longer stand on his own, not even with a walker. He sleeps most of the day.

The house that was fine for him when we first started renting it years ago is now something he can't access on his own. Doors are too small for wheelchairs to pass. The bedroom he and my mother consider theirs is on the main floor of the house, but the house...like most homes near the water...is up on pylons. Three grown men were needed to get him up that flight of stairs. It was a production.

But the beach house is where his children and grandchildren are, where there are sounds of life and laughter. He can tell his stories, and see loved ones around him. Having him here means he is part of us, and the extra effort required is simply what this stage of life demands. It is not, as I consider it, any different from the years we arrived at the beach with newborns. It's not an imposition. It's simply what must be done.

He isn't separated out, or discarded, or warehoused away. He's valued. He is gathered into his people.

July 28, 2023

Age, Pleasure, and Fruitfulness

Translation matters.

The task of a translator is, as I understand it, to best convey the intent of an author while simultaneously conveying a text into the language and idiom of the culture into which the text is being translated. It's a fine art, a careful balancing between the mother language and the receiving tongue, between one set of cultural norms and another.

Hew too tightly to the forms and expectations of the original text, and a translation can be unreadable and inscrutable. The geist of the author does not convey. On the flip side, if you make too many accommodations to the receiving language and culture, you erase the original, smearing one's own desires over that of the author.

Which is what I found myself looking at, as I looked at one of my favorite scriptures about aging. It's a familiar story, one from the heart of Torah. Abraham and Sarah are hangin' out in the shade near Mamre, when they are approached by three strangers. Abraham offers them hospitality, welcoming them to share in a meal. In return for that hospitality, one of the strangers bears a message: this old, childless couple shall have children. Sarah, hearing this, laughs softly to herself. She's old. Ain't no way that happens.

The verse in which she laughs is Genesis 18:12, and in the New Revised Standard Version, it read like this:

So Sarah laughed to herself, saying, "After I have grown old, and my husband is old, shall I have pleasure?"

It's a polyvalent verse, meaning it bears multiple meanings. Sarah snickers inwardly for two reasons. The first has to do with the absurdity of her having a child at all. I mean, she old. I'll occasionally joke with my wife about having another kid now that our boys are grown, and she'll roll her eyes. You idiot, she says, with a smile.

But when Sarah snickers, there's more to it than that. As my Old Testament and Hebrew professor would say with a wink, it's also because she's sure there ain't no way Abraham is up for that. So to speak. Hence the use of the word "pleasure." It's a sensual thing, and Sarah finds the idea that Abraham can still get it done amusing.

The New Revised Standard Version no longer exists, having been replaced by the New Revised Standard Updated Edition. Honestly, that Bible name has started to get a little silly. I mean, at what point does that stop? Will there eventually be a New Contemporary Amended Reimagined Revised Standard Modified Updated Edition?

I probably shouldn't give anyone any ideas.

Anyhoo, in the NRSVUE, the same verse now reads:

So Sarah laughed to herself, saying, “After I have grown old, and my husband is old, shall I be fruitful?”

Instead of pleasure, fruitfulness, and honeychild, those are not the same thing.

The polyvalence is squelched, the joke, undercut. The reasons for that editorial change, as best I can tell, are to "empower" Sarah. The laugh becomes only about her fruitfulness as a...cough...birthing person, and the little roll of her eyes at her husband's withered limitations is erased.

It's waay less funny, lacking in the earthy viscerality that so often rises from ancient Jewish culture. It also doesn't represent the Hebrew word ednah, which appears only three other places in scripture. It's the feminine form of a word for pleasure, which even the NRSVUE approaches differently in every other location. In Jeremiah 51:34, it's rendered "delicacies." In 1 Samuel 1:24, it's "luxury." In Psalm 36:8, it's "delights."

Delicacy? Luxury? Delights? That ain't a way any sane person would describe the process of childbirth in the Ancient Near East, kids. It's about the sexy sexy.

When we view the aged, that element of their humanity can be muted or forgotten. It's easy to forget, as we look at the old, how vital and alive they were. We see them as only old, as if the whole arc of their lives is only defined by our perception of them in the now. The life and energy still sings in that person, both as memory and as a lingering part of their person. It's the great madness of so much of progressivism, that willful forgetting of the joy and vitality of what came before.

As we age, we can also forget that part of ourselves, allowing ourselves to assume that we are no longer capable of any joy, or of pleasure, or of delight, simply because we're no longer quite as spry and flexible as we used to be. All that we once were, we are in God's eyes. We are still children, full of promise and imagination. We are still running fast with the sap of youth. We are still brimming with love and life and promise. We are wise and well-aged. We are all of these things before our Creator, all at once.

July 27, 2023

Moral Holiness and Honoring the Aged

Within the sacred narratives of scripture, the commitment to respect and honor the old is a consistent emphasis. There's the familiar injunction which appears in both of the iterations of the Ten Commandments. In Exodus 20:12, we hear:

Within the sacred narratives of scripture, the commitment to respect and honor the old is a consistent emphasis. There's the familiar injunction which appears in both of the iterations of the Ten Commandments. In Exodus 20:12, we hear:Honor your father and your mother, so that your days may be long in the land that the Lord your God is giving you.

In Deuteronomy 5:16, that's put slightly differently:

Honor your father and your mother, as the Lord your God commanded you, so that your days may be long and that it may go well with you in the land that the Lord your God is giving you.

Those both say more or less the same thing, although the later Deuteronomic phrasing seems to acknowledge that sometimes "days may be long" doesn't mean "that it may go well." Whichever way, the commandment is essentially identical. Giving honor to the elderly is woven up with blessings of both age and a good life in one's place.

Elsewhere in Torah, that baseline commandment is reinforced. "You shall rise before the aged and defer to the old, and you shall fear your God; I am the Lord," intones the Creator of the Universe in Leviticus 19:32.

It's a baseline expectation of the Biblical covenant, which was also the standard expectation in most cultures of the Ancient Near East. The concern with care for the aged is far from being an exclusively Semitic value. It was the norm in almost every human society, a moral expectation of all premodern civilizations.

In author and doctor Atul Gawande's BEING MORTAL, for instance, Gawande describes the network of community support that sustained his century-old grandfather Sitaram in a small Indian village:

Elders were cared for in multigenerational systems, often with three generations living under one roof. Even when the nuclear family replaced the extended family (as it did in Northern Europe several centuries ago), the elderly were not left to cope with the infirmities of age on their own...There was no need to save up for a spot in a nursing home or arrange for meals-on-wheels. It was understood that parents would just keep living in their home, assisted by one or more of the children that they had raised. (BEING MORTAL, p. 17)

This ain't even close to being the norm in contemporary Western society. As our family structures have been atomized by an endless fossil-fuel empowered diaspora, that cross-generational commitment has frayed. It makes living well in the last chapter of life more challenging, even given the putative abundance of wealthy nations.

During conversations about the challenges of aging in a recent class I led at my congregation, one of the participants shared her desire not to grow old in America. A is Ghanaian, and her observations of how the old are treated in Ghana and how the old are treated in the United States have led her to a very pointed conclusion. Ideally, she said, she'd grow old in a Scandinavian nation. After that, even given the limitations of the Ghanaian health system, she'd rather spend her last years in Ghana than in the United States. "I mean, if you get very sick, the hospitals are not as good," she said. "And you might die before you get to care. But at least your life up until that point will be better. So much better." She's observed how her grandparents, parents, aunts, and uncles have all been included into the large extended households that are still the norm in her culture, and how much richer that has made their quality of life.

What was a moral norm has now faded, as has the idea of moral norms itself. We postmoderns shy away from anything that resembles duty, any implication that our purpose extends beyond self-gratification and indulgence. It's an ethos that masquerades as freedom, but is not. It rises instead from consumer culture and the socially-mediated attention-deficit popcorn-brain that clouds our engagement with both past and future and keeps us imprisoned in our anxious, impulsive, profitable now.

From that solipsistic moral framework, we'd rather not be inconvenienced by the old, or by the unpleasant thought that we, too, will one day stand in their place.

Because if we are not caring for the old, then we will not be cared for. It will not, as the Deuteronomic scribes remind us, go well for us. That's the nature of covenant, after all.

July 26, 2023

Aging in History and Scripture

There's a peculiar dissonance between aging in the world of human history and aging in the narratives of Torah.

We know, because we do, that in both the ancient world and in prehistory aging wasn't something most of us did. What most of us did was die young. Get a childhood illness? You died. Have a complicated birth? You died. Get an infected wound? You died. By the time most human beings were in their mid-thirties, they weren't finally getting established in their career. They were dead.

As a species, we got around this the way that all other animals get around that basic existential challenge: we reproduced in large numbers, spamming ourselves into the world.

Age wasn't something that most people did. The idea that most human beings would make it into their seventies would have seemed impossible.

Yet the tales of Torah lay out an entirely different spin on aging. The farther back you go, the longer people live. In Genesis, we hear that Adam, literally "the creature of earth?" Adam lived nine hundred and thirty years. Nine hundred and thirty. Methuselah, whose name was once synonymous with "very old dude?" He lived the longest, at nine hundred and sixty nine years.

Noah had his kids at five hundred, which sounds...exhausting.

All of the antediluvian...meaning "before the flood"...folks in Genesis lived preposterously long lives. If one was a literalist, which I am not, there'd be all sorts of reasons one could present.

For instance, one might argue that so close to the exile from the Garden, the first humans were closer to immortality and agelessness, a lingering echo of the deathless perfection of unmediated connection with YHWH. That works theologically and within the text, but it's a little hard to jibe with the way the human body actually functions. If you have any engagement with Creation as it actually and observably exists, that sort of argument isn't particularly satisfying.

When I was a kid reading the Bible for the first time on my own, I just kinda assumed the authors of that section were using a lunar calendar, and where they said "years," they meant "months." That breaks down when you get further in, but hey, I was nine.

Or perhaps it's a factor of the peculiar subjectivity of time, in which days seem longer when you're younger.

Or perhaps, as historical critical scholarship suggests, the great age of the antediluvian patriarchs is a conceit of the storytelling of the Ancient Near East, where the archetypal heroes lived in a time beyond time. In Mesopotamian literature, for instance, the legendary figures in their pre-flood narratives typically lived for thousands of years. This directly parallels ancient Hebrew storytelling, because of course it does.

No matter what your interpretive framework, what is clear is that age in the ancient world was viewed as a thing of great worth, something fundamentally positive. Aging was a rarity, and those who did reach their seventies or eighties were viewed with reverence and honor. Their lives would have spanned the equivalent of several normal lifetimes, and they would be valuable repositories of collective memory, living relationships, and experience.

In the ancient world, the old were rare and precious and valued, because so few human beings attained great age.

What a strange and different world that must have been.

July 20, 2023

Dad, Driving

It's grown harder and harder for Dad to move as the years have rolled by.

I first noticed it when he was in his early sixties, as it became harder and harder for him to trounce me on the tennis court. Dad was always a cagey, fierce competitor, a tournament-level senior player. I might have been thirty years younger, but my game was what one might politely call "recreational." I never, ever took a game from him. Points, on occasion. But never a game.

Dad had a short mans' game, nimble, strategic, and accurate, a holdover from an wooden-racket era when men's tennis wasn't such a drab sport to watch, just rangey dudes bashing away from the backcourt. Court mobility and placement were his strengths, and while the latter stuck around, the former?

Slowly, inexorably, his knees wouldn't let him move. He still tried, still pushed, because winning mattered to him. But I could see him hurting himself to get to the ball, see him pull up when he tried to run, a grimace breaking out on his face as pain lanced from his knees. Were I a monster, I suppose I could have taken a couple of games off of him then. Maybe a whole set. But the killer instinct is not strong in me, particularly with folks I love.

Tennis faded away. But his knees kept worsening. Walking became harder. We encouraged him to get the knees replaced, but he wanted to wait "because knee replacement surgery doesn't last forever, and I only want to do them once." There was a thrifty Scots logic to that, I suppose, but it meant years of discomfort.

Then, in his early seventies, his heart began to fail. Bypasses. Valve replacements. Emergency replacements of the valve replacements. That, plus his knees, plus his vision, plus his hip.

It wasn't simply that he couldn't walk. It became harder to drive, harder for him to remember where he was going. We live just fifteen minutes away, in the same house we've lived in for twenty five years. But Dad started having trouble remembering how to get to us, as Mom...whose memory has always been a wee bit scattered...took over navigating.

And then, finally, in his early eighties and at the height of the COVID pandemic, he was diagnosed with congestive heart failure.

Suddenly, getting out was a big deal. Walking any distance was impossible. But driving? Lord have mercy, was it hard to get him to stop. Not that he loved driving, because he was the farthest thing from a car enthusiast. Our family cars were always practical vehicles, just a way to get from point A to point B.

But point B meant being with people, and that was what gave life savor. It meant tennis and beer with friends, or just beer with friends. It meant singing in the choir, and getting to rehearsals for community theater. It meant social gatherings and dinner parties. It meant going to movies, and going to concerts.

Driving is how you live well in America, and how you spend time with other people. For men of his generation, it was also a marker of maleness, of virility, of capacity and competence. And as it became less and less safe for Dad to be behind the wheel, that sense of self started drifting away. He had to stop. Had to. He couldn't see. His reaction time was shot. He had less and less sense of where he was on the road. He was, frankly, terrifying to drive with.

But it was...as it is with so many of us...hard for him to admit it. He still hasn't totally admitted it, as of this writing. Some days he accepts that his driving days are done. Other days, when his father's stubbornness rises up in him, he'll insist that he needs to stay in practice. To get out and about. In case of an emergency.

But he can't walk to the car without his walker, and can't get into it without help. That's on a good day, when his CHF doesn't leave him so weak and winded that he can barely lift his legs.

Without mobility in a society that demands mobility, life gets so much harder.