David Williams's Blog, page 27

July 20, 2023

"Doing the Work"

The most peculiar thing about contemporary Western progressivism is how completely it has failed to engage working folks.

Marxism always managed to connect with the proletariat, to make it clear that it was worker-oriented. The Jacobins, for all of their guillotine eccentricities and counterproductive obsession with changing everything all at once? They still resonated with the masses.

But American leftism doesn't really have the vocabulary or worldview to connect with the workers of the world. Why? Because it conceptualizes "work" as meaning something very different. It understands "work" as an abstraction, as examining and analyzing perspectives, as psychotherapeutic.

This is nowhere better evidenced than in the prog-buzzphrase "Doing the Work."

When suburban American progressives talk about "Doing the Work," they're talking about conceptual work. Emotional work. They're talking about reimagining and reckoning. They're also talking about "justice work," which means making demands of power, organizing, and activism.

But they're not talking about "work," in the sense of things that are actually being done.

"Doing The Work" doesn't mean doing plumbing or electrical work. It doesn't mean maintaining or repairing machines or HVAC equipment. It isn't about preparing a field, or harvesting, or transporting that harvest. It isn't about roofing or drywall or woodwork. It doesn't prepare or serve food, and it ain't dishroom or pots and pans, neither. It doesn't stitch up wounds, or fix potholes, or repair a tire. It doesn't involve any material labor or action at all. It's work as meta-work, work as a social construct that can mean anything at all, work distorted by the fun-house mirrors of semiotic sophistry, work as something immaterial.

Abstracted work doesn't have to change anything or move anything or make anything. It's not labor, not as that term was ever understood in the modern era.

"The Work" involves meetings and trainings and more meetings, motions and amendments to the amendment to the motion. It's work as the bourgeois and rentier classes have always conceptualized it, busy little bees bustling about doing the aforementioned "emotional labor." It's the daydream of work, work as symbol, work as utopian fantasy. Not to say that there's not pleasure in that at times. But that pleasure comes from "work" in the same way that this blog is work, or that Facebook or tweeting is "work."

Actual work makes a difference. Actual work, real work, material work in the physical world? That's measured in joules and newton-meters, sweat and effort. Most of what we do is not that. Most of what I do is not that. Our culture steers millions of us into ersatz labor, labor that does nothing, labor that is useless. We know this, instinctually, viscerally. That's one of the reasons we're all so anxious and listless.

Yesterday, before heading to church, I worked for about half an hour harvesting green beans from my raised beds. I was squatting or on my knees in the summer sun, carefully sorting through the foliage of my bush beans for perfectly ripened beans. At the end of that half hour, I had four pounds of fresh produce. Half of that yield I kept for myself and family. The other half I bagged for the produce stand section of my congregation's Little Free Pantry.

I could have written a post about food insecurity in that time. I could have Zoomed with an activist or two. Those things would be fine, but they are not of themselves work. Work is moving my butt outside. Work is my quads straining, and my eyes and hands seeking out the beans, and the act of placing those beans where someone who's worried about feeding themselves can find, prepare, and be nourished by them. There will be a change in the world because of that effort. It will be small, it will be humble, but it will also be real.

Work, in other words.

July 19, 2023

Our Home in Old Age

There comes a time when we cannot work.

There comes a time when we cannot work. Not just "don't want to." Not "quiet quitting," or whatever the term is now for hardly working rather than working hard.

But actually not being able to perform the tasks that any job requires. When our bodies no longer allow us to stand and move around, and our minds struggle to hold on to short-term memories, there's just no way for us to participate in the rush and bustle of the daily grind. The arrival of that season varies from person to person, but it comes for all of us.

When it happens, there are implications. How do we put a roof over our balding and/or silvery heads?

For the wealthy and the propertied, there are buffers and protections. I've seen this in my own family, and in my circle of family friends. One good friend from the church where I grew up has moved in with her children, and to facilitate this built a comfortable, accessible addition to their home. Another did the same thing to the home she and her husband lived in during their adult years, creating a "wing" to their house with wide doors, open and accessible bathrooms, and an elevator. These were wise uses of the resources of worldly wealth, but most Americans don't have that option.

For those who do not have retirement savings? Paying for our living space grows harder and harder as we lose the ability to care for ourselves. The long-term care that is necessary to keep us in our homes as we age isn't covered by Medicare, and private long-term care insurance is both expensive and challenging to negotiate.

Things can get really difficult, really quickly.

During the many years I delivered for Meals on Wheels, I over and over again encountered elderly folk who were struggling to make a go of it in their homes by themselves. Some were managing, mostly with the support of neighbors, younger friends, and nearby family. Others were clearly past the point where they could handle life by themselves, so physically and mentally compromised that being in their home was a burden. Those were the homes filled with piles of unopened mail and neglected possessions, the occupant either confined to a chair or obviously non compos mentis. They were relying on home aide support that was insufficient, or had no real help at all.

Most of us prefer to stay in our homes as we age, because it's a reassuringly familiar space. But those same homes can become a shadow place, a place filled only with the echoes of our former life.

And the 20% of elderly Americans who don't own their own homes?

Sudden surges in home prices drive up rents, and then, well, then what do you do? "Camping" really isn't the most pleasant of options when you're young, but when can't really even walk on your own? It's even less so.

Medicaid does provide for nursing care for those who have exhausted their resources, but access to those nursing homes homes was never easy, and has gotten harder post-pandemic. With a significant shortage of rooms, particularly in rural areas, those who find themselves physically unable to care for themselves can be stuck in hospitals.

It's a challenge more and more will face, as our population becomes grayer.

July 15, 2023

Why We Still Work

In the face of our unpreparedness for retirement, many of us simply don't.

Sometimes, we continue to work because we love our work. We continue to be able to contribute even though our bodies may ache and complain, and our minds have trouble remembering exactly why we came downstairs. What were we getting again?

We love the mental stimulation of labor, and we know our field, and we still have something to contribute. There's pleasure in a job well done, and we want to enjoy that pleasure as long as we can.

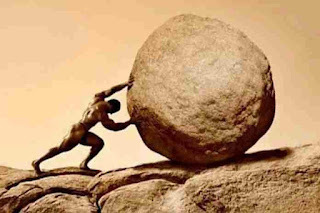

But mostly, lately, Americans continue to work because we have to work. The option of stopping our season of labor and taking sabbath at the end of a life's work simply doesn't exist, because if we took it, we would starve. Increasingly, we're forced to continue heaving that rock up the hill, whether we take joy in it or not.

Research from the Bureau of Labor Statistics shows that the number of seniors remaining in the workforce will increase by nearly 100% in the next decade, as we both age and find ourselves continuing to need a regular source of income. Though many folks retired early during the pandemic, more and more retirees are coming out of retirement, continuing to work well into old age, like Harrison Ford coming back one last time for Indiana Jones and the Greeter of Walmart.

We've got debt for medical expenses, debt for our homes, debt for our cars, debt for our children's education, and sometimes lingering debt from our own education. St. Peter may be calling, but we can't go, 'cause we owe our souls to the company store.

Given the wild fluctuations in our "free market" economy, there's also impetus to keep our toe in the water and some skin in the game. Retire at the wrong time, and you can find the assets that you'd assumed would be sufficient suddenly...aren't. As we're living longer, and retiring at sixty five or sixty seven means twenty more years of life, we're likely to see some economic catastrophe or another at least once during those two decades.

I mean, seriously, we're relying on Wall Street to provide a stable, consistent, unpanicky income for our dotage? Wall Street? How often over our lifetimes has there been an economic crisis? Pretty much every decade, some industry or another overheats and collapses, and all of the financial gurus go into a tizzy. Housing loans. Student loans. Dot coms. Asian Tiger markets. Algorithm-driven selloffs. Pandemics. You name it, the Invisible Hand of the market is great at dropping the ball, like the world's least competent Pee Wee League wide receiver. It's an ephemeral edifice fabricated from groupthink, avarice, and wet tissue paper, and it comes apart at the slightest whiff of crisis.

In America, it's always the wrong time to retire. Always.

We know this because we can see it, and so we don't retire.

July 14, 2023

We are All Unprepared

Best I can tell, I will be able to retire eventually. This was once the general assumption of most Americans, the expectation that when you reached the end of middle age, you'd set down your labors and spend your dotage travelling or puttering around in a golf cart through some sprawling community in Florida.

That is no longer the case. With the collapse of the Soviet Union back at the end of the last century, American businesses no longer had any impetus to provide cradle to grave care for their workers. Health care? Heh. Sort of, barely. Retirement benefits? Sure...but the risk is all on you, and the rewards mostly accrue to those who "handle" the trillions that pour into the markets.

That, coupled with a culture that celebrates the debt-financing of life, immediate gratification over long term planning, and fetishizes youth and adolescence? We are, as a people, catastrophically unprepared for aging. We just ain't ready. Not even faintly.

And we are aging, all at once, thanks to the great pulse of Baby Boomers who have defined our culture for a generation. They are, all together, getting older.

A recent study by the Urban Institute lays out some pretty challenging statistics about this grey wave. By 2040, the percentage of the population that is over 65 will have nearly doubled from where it was in 1980. The number of individuals in the oldest category, those who require the most care and are least able to fend for themselves? It'll be quadruple what it was in 2000.

Life expectancy has continued to rise, so those who are old will be old longer, living a decade or more deeper into age than they did a generation ago.

With that shift, Social Security...which we've very much not prioritized...will come under significant pressure. With fewer working age folks supporting more older folks, that financial safety net will fray under the strain. We've pushed off doing anything about it for forty years, and the bill is coming due, no matter how much magical thinking we apply to the subject.

Our failure to prepare as a nation is mirrored by our failure to prepare as individuals. It's one of the peculiarities of a republic, as the ethics of debt play out both in the halls of Congress and our own ever-expanding credit card balances.

Right now, as of this writing, the average Social Security benefit stands at just over fifteen hundred dollars a month. Nearly half of Americans have no retirement savings at all, which means the average American household has about twenty one thousand dollars socked away for retirement. If you retire at 67, and live until you're in your eighties, twenty one thousand dollars doesn't quite cut it, and fifteen hundred a month runs through your fingers real quick lately.

Having enough financial reserve to make it more than ten months into an American retirement means you need to be, relatively speaking, rich.

My wife and I don't seem rich, at least not on the surface. We live in a 1,300 square foot rambler on a quarter acre suburban lot. This is about half the size of the average new American home. It's where we raised our kids, and while it was snug when there were four of us, its plenty of room for two. Our cars are functional and reliable Hondas, utterly unsexy and leaning towards efficiency and practicality. I ride to work and run errands on a Yamaha scooter, which gets over 80 to the gallon. As a small church pastor and author, my annual income over the last decade has averaged $35,000 a year, which...isn't much.

But scratch the surface, and we're almost painfully privileged. Rich, even. My wife's consulting business has done quite well over the last few years, in a King Lemuel's Wife sort of way. Rache and I own our home outright, so we have no mortgage. We own our cars outright. We have no debt. None at all. We live small, and live lean, and have consistently over a lifetime spent less than we made.

Our savings, for retirement and otherwise? Over One Million Dollars. That's not what it used to be, in an Austin Powers Doctor Evil sort of way, but it's nearly fifty times higher than the typical American retirement reserve.

Taken as a whole, we're just not ready. The morning has come, and we're sitting in class on the day of the final, and we're staring blankly at questions for which we don't have answers.

July 13, 2023

The Dangerous Neighbor

The carpenter bee was dying. There, on the walkway leading to my front door, it struggled to move, stumbling forward, wings humming feebly, unable to take to the air. Normally, that would feel like a tiny tragedy, as bees are always welcome in my yard, but I am of two minds about carpenter bees.

On the one hand, they're pollinators, vital for my garden and the future of our world. On the other, they have over the years carved neat hole after hole into the painted wooden awning supports and siding of my home.

By later in the day the thick-fuzzed yellow-black body was an unmoving corpse, and the reason for its demise soon became apparent. I noted a new inhabitant entering the neat circular hole formerly belonging to the bee. It was a wasp, large, starkly striped and fierce of appearance. It was the obvious culprit, and had taken the bee's hidey-hole by force, a lethal winged conquistador.

Rache and I sat out on our porch under that hole in the late afternoon, as our new neighbor hummed about near us. Rache wondered aloud whether it was dangerous, because it sure did look that way. Should I take it out? It was tempting. Bees are all fuzzy and cute, even the more troublesome ones, but wasps? Wasps just look hard, purposeful and ready to fight you. This one was nearly hornet-sized, and looked like it could deliver some serious hurt. Was it a threat?

I didn't know the answer to her question, which I quickly remedied. The critter turned out to be a variety of mason wasp, a species that will routinely attack and kill carpenter bees for the sole purpose of stealing their nests for their own. They're not aggressive like those devil-spawned yellowjackets, cursed may they be. You leave mason wasps alone, they leave you alone. They're no more likely to sting than the carpenter bees, but when they do, their sting is indeed hornet-fire agony. That was a little unsettling.

As I read more, though, I started to warm to the wasp. Mason wasps don't just murder bees and steal their homes, which seems low karma even in the insect world. They're builders, who don't do any damage to human houses themselves, preferring to create mud structures when they're not getting killy killy with some hapless bee. The wasps also pollinate as they fly from flower to flower in search of pollen and nectar, if not quite as effectively as bees. Beyond flower feeding, they also do something that carpenter bees do not: they hunt and eat caterpillars, both for themselves and to cart back to feed their young.

To which I thought, huh, they go after caterpillars? Caterpillars are not my friend. They'd devastated my greens, year after year, to the point where I now grow other crops. They've nibbled away at squash. I don't use pesticides on my garden, not ever, so when the munchy worms appear, I don't have a whole bunch of options.

All of a sudden, that lethal-looking blackstriped wasp was looking a whole bunch more welcome, less like a threat, and more like a new ally. Like having a feral cat hunting mice in the granary, or a stray dog who takes to watching the henhouse and chasing away foxes.

Only slightly less pettable. For now, they're welcome to stay.

It's always best to learn more about a new neighbor before jumping to conclusions.

July 12, 2023

Masks, Roles, and Retirement

I dreamt, on a recent night, that I was no longer a pastor.

It was, as I considered it over the next morning's coffee, the subconscious manifestation of a thought that I have on a recurring basis: what am I going to do when I retire? There will come a point, and it's not far off, when I'll be of retirement age. In just over a decade and change, as I step into my late mid-sixties, I'll be sufficiently far along in this mortal coil that my denomination encourages folks to step aside for a younger and nominally more vital generation.

It can be a difficult thing, making the transition away from a profession that comes to define your identity. We're used to being thought of in a certain way, and standing in relationship to others in a certain way. We take on our vocation as a mask, one that defines how we are seen, one that comes to shape our personhood in ways we're reluctant to release.

This conflation of our work with our identity can make the process of aging more spiritually challenging. Who are we, if we are not the thing that fills our days? Where does our sense of self lie, when the mooring lines that hold us release?

It's be nice to say that those in spiritual leadership handle this transition more effectively than other souls. Because as we all know, pastors and rabbis, imams and priests and gurus? Utterly without ego. To which, I hope, you uttered a sad, knowing little laugh.

More often than we'd like to admit, those of us who fancy ourselves leaders of faith folk pour so much of ourselves into our role that we can't imagine being anything else. We don't allow ourselves to be anything else while we're in that role, as we become utterly consumed by the needs of our community.

This doesn't work so well. Assuming burnout doesn't immolate our sense of vocation, that compulsion to be needed leaves us poorly prepared to slow down when age requires it. Who are we, if we are not the One With The Answers, the Manager of Everything, the Putter Out of Fires, the Conduit to the Divine? When that mantle is lifted from our shoulders, it's easy to find that we no longer recognize that lined face in the mirror. Who even is that? Who are we?

It's necessary to ground our souls on something more solid. To prepare for what is to come.

First, it's essential that we develop a sense of self that rests on more than just what we "do." I love my vocation, I do, but there are other facets to my person. I read, wantonly and wildly, and enjoy few things more than settling in with a library book. I tend to my garden, puttering about weeding and seeding and watching the miracle of life rise from the soil. I game, enjoying virtual narratives and simulated worlds. I write, spinning out my thoughts in blog posts that five people read, or tell stories that I want to hear told. I enjoy film, both classic and current. I enjoy live performances, and travelling with Rache.

I've done these things for years, because waiting until one has retired to develop things that bring you joy is a fool's error. So long as God is willing, I will continue to do them.

Second, I understand my vocation as both a calling and a season. When I dreamed I was no longer a pastor, it was a good dream of a coming season. I was working with others in a church, as we prepared for an upcoming event. Being a dream, that event was a little hazy, something to do with a meal that was open to all. In that dream, I was working with others, but I wasn't running the show. I was just one of the laborers, as the group discussed and planned.

I was, in other words, in a place where I was simply a Christian, one disciple among many. It's a good thing to be, and living into that grace has always been the extent of my faith-aspirations. It's what I teach, and what I preach, and how I try to live. With the emphasis on "try."

I've always understood pastorin' and the ordination to my role within the church as a functional thing. Meaning, I'm a Minister of Word and Sacrament only as long and insofar as I preach and baptize, teach and serve at the Lord's Supper. That ordination is a question of function, not inherent and permanent authority. Once I'm not doing those things, I am not a Minister. I can stop the cosplay, take off the silly collar shirt and my careworn academic robe and return to being one servant among many. I will remain a Teaching Elder into retirement, but not a pastor, not unless I am doing pastorly things.

In my little congregation, almost everyone has been ordained to serve as an elder at one point or another. That's just the way little churches roll. They're all still Ruling Elders, technically speaking, but functionally? You're only Buildings and Grounds Elder when wrangling aging HVAC and mending leaking roofs is your specific responsibility, thank the Good Lord. You're only the Worship or Stewardship or Mission Elder for a season. After that, the ordination goes fallow until another season of labor is required.

Should I have the good fortune to reach the moment of Honorable Retirement, With All the Rights and Privileges Thereunto, I will be content to be simply another servant among servants, one living in my sabbath season.

July 10, 2023

Unborn that Way

Taylor looked up from the screen of their flat and across the central square. It was still midmorning, at the heart of the first shift. Everyone should be working, or in the Edcenter. But it was a beautiful spring day, the air tart and clean, the sky a perfect blue, speckled with little puffy clouds. It was as good as the best Virtual, only with that little bit extra, that unreplicable kiss of a soft breeze on your hand, that complex stirring of organic scent, new flower and chlorophyll and the rising of life after winter.

The square was bustling, because of course it was. Technically, it was firstshift on a workday, but it was also the day after Matchday, and everyone knew what that meant. The whole world slowed down after Matchday. Tall oaks and maples planted a century ago cast down beneficent shade, the light playing down through their breeze teased leaves. Couples and throuples and polys mingled and laughed and lounged on the grass, balancing worklife on the lifeside. At the center of the park, a single deactivated combat and interdiction golem sat powered down and at peace, the lenses of its sensorium gazing fixed up at the blue, weapons binnacles empty, a statuary reminder of victory in the Culture Wars centuries ago.

In the shadow of the great ancient bipedal machine, the young, teeners and twenties, connecting with their matches, and their energy sparkled, casual and flirtatious and excited.

Which made this whole thing harder.

Every one of these groupings, Taylor knew, had Clearance. Had received the necessary reviews and approvals. Had been matched with viable partners, single or multiple.

But Taylor themselves had not. They had waited, hoping their message tone would chime on their flat, just like it had for everyone else they knew. Excited chatter had filled the dorm as the day progressed, rising with each tone. That chatter had subsided again as the afternoon waned, had grown more quiet as other dormies had gone out into the cool spring night to meetngreet their matches.

Taylor'd not made a fuss of it, not called attention to themselves, trying not to detract from the pleasure of the day. They'd tried to fade out of view, not to Be That Person. Riley and Avery had noticed, of course, dear old friends that they were, and the three of them had huddled in a sympathetic klatch for a while. "I'm sure it's nothing," Riley'd said, smiling. "You're just so lovely and compats with everyone." "Just a glitch," Avery affirmed. "They'll be in touch soon. You are beautiful and loved."

But Riley's match was in Zone 9, and Avery's in Zone 19, and after staying as long as they could, they both left with a reluctant sigh.

Finally, finally, long hours after everyone else, the message had come through. It wasn't a match, or matches. It wasn't the particulars of their Compatibility Cleared. Just a terse formal instruction to report to the Region 12 Intimacy Coordination Center. Not to their advisor Hayden, who had been super helpful, not to Testing for some additional assessment, but to report to the Office of the Senior Regional Intimacy Coordinator. No details. Nothing about why. Taylor'd felt like the bottom of the world had fallen out, a cold stone in their stomach.

Across the park, through a gauntlet of happy hormones, stood the elegant glass edifice of the Regional Coordination Center. On the ninth floor, in suite 9.077, Mx. Turnberry, Senior Regional Intimacy Coordinator waited.

Taylor took a deep breath, and started forward through the throng.

----

"I know you're anxious to know what this is all about," Mx. Turnberry said, after Taylor had settled into a proffered chair. Turnberry was a small person, with busy little hands that fidgeted across the surface of their neat, expansive desk. Behind them, the window was bright with the light of morning, their face gently shadowed.

"Anxious is a good word for it," Taylor returned.

"Let me reassure you. You've done nothing wrong. You are beautiful and loved."

"Beautiful and loved," Taylor repeated, but without enthusiasm.

"I won't lie to you. We have a...complication." The word chilled the room.

Mx Turnberry fiddled with their flat for a moment, then continued. "Same gender attractants used to be embedded in the broader population, forced to keep themselves hidden by retrogressive and oppressive norms. Same gender attractions and variant gender identities were forcibly suppressed, which we all acknowledge now was a terrible, terrible thing. The Awakening changed all of that, and the Culture War finalized it, although it took most of a century, we together finally did the work to free the norms of culture from that primitive way of thinking. It's been three hundred years since we cast all of that aside."

Taylor pursed their lips, waiting impatiently for the familiar monologue to end. "I mean, of course, I know this, this is elementary ed stuff. Why are you telling me this now?"

"There's a..." Turnberry flushed, slightly. "Let me be more direct. There's a problem with your intimacy matching."

"A problem?"

"We...uh...don't have any matches in system for you right at the moment."

"What?"

Mx. Turnberry shook their head. "Not at the moment."

"But the testing? The assessments? The psychexam and ideologograms? Those results were...I thought I had passed."

"You did. You did exceptionally well," affirmed Turnberry, earnestly. "You are beautiful and loved, wonderful just as you are."

"Then why...what's going on? Everyone I know is being matched. What's wrong with me? You're not telling me something." Taylor's thoughts circled, swirled, repeated. "What's going on?"

"I know this is potentially traumatizing," said Turnberry, their voice measured. "And be assured that I will do everything in my power to fix this. You deserve an answer. Let me show you something."

Turnberry swept their fingers across the haptics on their flat, and a neat hidef holo appeared. Graph lines snaked across a glowing grid, frequency tracked over time. "It wasn't really something anyone considered, back when we came to better understand the fluidity and variability of gender. Cisbinidenting folx like myself and my partner could always choose to live into their birth gender. After the Culture War, those who chose differently were finally free to have full autonomy over their bodies and gender identities. No-one would ever again be forced to live into the false assumed binary of tradsexuality."

The graph glowed and shifted, a line spiking upwards, holding, then descending precipitously.

"That freeing came with a price, one that became more evident as time passed. It's well known that queer identities are a fluid social construct. But...they're also genetic. A question of an individual's brain structure and hormonal balance. We are born into ourselves, our particular and uniquely beautiful identities shaped by the genetic contributions of our birthing person and our seeding person."

Taylor closed their eyes, and suppressed an impatient groan. "Yeah yeah yeah. I know this."

"Given the choice to live into their gender and our prior overpopulation, a supermajority of queer folx chose, well, they chose not to reproduce."

"A right is chosen, a new world flows in," Taylor murmured, their words involuntarily following the lyrical cadence of the old kindergarten song.

"It does," said Turnberry. "Of course. It's the responsible choice, particularly as we right-populated into the collective reimagining of our ecology. Which is what makes the outcome so very...." they paused, genuine pain on their face. "Ironic. Or tragic. Some combination of the both."

Taylor's eyes widened. "What are you saying? I think...you can't be..."

"Seventeen generations, in which queer folx reproduced at a rate less than one quarter that of an already intentionally reduction-focused tradsexual population. Genetic screenings of embryo slates for Wellbaby and Chosenchild Parenting Preference Protocols also had a nontrivial impact. The genetic predispositions to certain identities that had always passed along covertly under oppressive hegemonic tradsexual reproduction norms just...didn't. Pass along, I mean."

There was a pause, then Turnberry continued. "Have you known anyone who shared your identity?"

"I haven't. But I thought...I assumed..." Taylor's voice petered out, choked away by a rising dread. They went on.

"Are you...are you saying that people like me were...bred out of existence?"

The Coordinator struggled to meet Taylor's gaze. "No no no no. 'Bred' is an assumption of imposition. This wasn't some perverse twentieth century eugenic nightmare. It was a choice, one made by millions, one that affirmed identities and birthing preferences and the social good, one informed by the intersection of gender and climate, one that..."

"But you're saying there are no more queer people."

Turnberry looked a little distressed. "No, we would never say that, of course we're all queer in our own way, and mutations do occur regularly even in a hypermajority tradsexual population. There will always be some."

"How many? How many like me right now?" Taylor's voice, tinged with heat.

Turnberry flushed. "I...it's a little.."

"You're the Senior Regional Intimacy Coordinator. You know the answer, and it's my right as a citizen to know. How many?"

"Seven."

"Only seven in the region? That's so few. Almost no-one."

Turnberry inhaled through their nose, let out a long sigh. "Oh, Taylor. That's not what I'm saying. Seven total unassigned in your age moeity, for all regions, everywhere. Four are unpaired same gender attracted birthing persons, two are birthing-person-presenting post-transition, alternate gender attractant. And there's you."

"Just...me."

"Just you."

There was a long silence. "I'm the only gay man on the planet?"

Turnberry recoiled as if struck. "You know we don't ever use those ur-fascist heteroassumptive terms, Taylor." Their voice edged colder, repressing their offense at the slurs. "You know better. But you're upset, so I'll let that pass without dinging your social score. But yes. You are the only cisbinidenting same gender attractant seeding person currently in the global dataset. Within your age moiety and psychodemography."

"I'm sorry. I'm...but...but maybe the moieties above me? Older? Younger? Maybe there's some..."

"They're not matches. We've tried. Their pairings/groupings are too settled, or their testing indicates unacceptable levels of compatibility. The numbers are just so low."

Taylor slumped back into their chair. "I...what can I...how..."

Turnberry softened. "Look. This is so, so upsetting. Traumatizing. Not just for you. For all of us. This has been taken to the highest levels, to all of the Regional Intimacy Coordinators. Even Global's paying attention. We're monitoring all tests, we've prioritized your Match. You'll have your Matchday, you will. Just not now."

Mx. Turnberry looked as earnest as they could. "You're an important person to all of us. You are beautiful and loved."

The platitude, like a cold wind in the leaves. A hiss rose in Taylor's ears, and the world spun. The saying, meaningless.

Because Taylor wasn't. Not now.

July 4, 2023

The Future Church and the Aging

I've been writing a whole bunch over the last several months, as I reflect on faith and aging. But in all of it, I'm not sure which church I'm writing for.

There's no question that my particular denomination is dying. The Presbyterian Church USA is aging out, and not replacing ourselves. Within my lifetime, the broader denomination cannot continue its current form. We'll fragment, or restructure, or collapse, but we're likely already past the inflection point for collective viability.

This is part of a larger challenge for the oldline denominations, those manifestations of early modern era Protestantism. Methodists and Baptists, Lutherans and Episcopalians, all of us are growing old. While some individual churches are pressing back against that tide, they're outliers.

This poses something of a conundrum, because there are younger churches out there. They have young families and middle aged folks, kids programs and They're not structured on the denominational model, but on the "nondenominational" franchise/corporate model. They're evangelical and contemporary, continually adapting and finding relevance, shifting worship and music and community life to mirror the expectations of culture.

That's not my preference, of course, but that doesn't matter. Those communities are going to continue, even in the face of shifting social norms about faith. When I've attended worships in the big mega corporate congregations, they've been diverse and vibrant and materially successful. The one demographic that's been missing: the old. Old folks just aren't there, because the worship style and the music have moved on. Contemporary Christianity has left the saints behind.

The church is segregating as our culture is segregating, with the elderly continuing to be faithful in churches that aren't societally resonant, that are dying off as they die off.

What happens, then, to those saints who have worked to maintain their churches and communities? The prayerful souls who run the food pantries and clothing drives, who provide material resources to those in need? What happens to those who've spent their whole lives being faithful, but now find the congregations they've been a part of for decades drying out in the sun as the tide recedes?

It goes deeper, though, beyond simply caring for other Christians.

There will be millions of Americans who find themselves without supportive family structures, without communities around them that can manage their care, and without the material resources to sustain themselves as they lose the ability to work. The "safety net" of Social Security will have frayed through neglect, and we'll all be struggling to adapt to a harsher, hotter planet. It "ain't for sissies" now, but our future shows every sign of being a harder time to be old.

It is possible, of course, that our society will change course, and realize that the future we've created for ourselves isn't one we want to inhabit. This is possible, but improbable.

As our broader culture ages, he churches that have adapted and remain standing need to see seniors for what they are: human beings who are a field for mission, Christian care, and evangelism.

July 3, 2023

Preparing Our Souls for Aging - Love 2

Second, the love of God provides a radical affirmation of love for others. For strangers. For enemies.As we get older, the world can become a frightening place. Everything becomes more dangerous. A simple walk to the bathroom can be fraught with peril, as one missed step can change or end a life. That, and our culture now changes constantly around us. The endless rush to obsolescence and corporate capitalism's relentless remaking of the world means that we can no longer rely on a lifetime of learning and experience. A once familiar world is suddenly strange and unpredictable and complicated, and that unsettles us. Makes us feel like we're not sure about the ground under our feet. That's true both figuratively and literally.

When we feel our vulnerability, our strangeness in a strange land, it becomes easy for us to perceive threats everywhere and in everyone. Everyone is stealing from us. Everyone is suspect. That fear of the strange and the unsettling is pretty much the entire business model of most contemporary media, be it right or left leaning.

As we get older, we need to take care. Sure. That's true. But it's easy to become so hypervigilant against an endless stream of scammers and hucksters and charlatans that we may lose our ability to recognize where God is placing others in our lives. That's perhaps less true of those who are old right now, but it's going to be a challenge for those of us who will age into the world shaped by the internet. When we can't trust that the call from our adult child is really a call from our adult child, that both the number and the voice on the other end might be faked, how will we relate to the world?

From that place of fearfulness, the tendency towards social isolation can intensify. Without stable and sustained face-to-face social ties, places of deep connection to local community, we will find ourselves in a more challenging place than prior generations. Family structures, for many, have become much more complicated and fragmented, and may prove less of a support. Friendships are wonderful, but as we tend to befriend our own age demographic, those social networks will age with us.

Right now, are you laying the groundwork for life at the end of life? Being part of an intergenerational community of faith is a vital part of that experience. Here, I'm not speaking from the standpoint of crass self-interest. "Golly, I really need to be part of a church so they'll take care of me." Nope. That's not the point, although we will. That's how we roll, insofar as we are able.

Being part of a church teaches the lifeway of aging, ingraining the ethic we need to age well into us.

We learn what we will need to know as we age by connecting with those who are living through that phase of life, by visiting and befriending and being part of the lives of those further along in life's journey. Our duty to care for our elders, to honor our mothers and fathers? That duty must manifest itself when we are younger, because if we fail in that moral imperative, we can expect to reap the harvest of our neglect. The measure we give, as Jesus so succinctly put it, is the measure we will receive.

Still and all, while being part of a gathering of Christ-followers increases the probability that we will have supportive community around us as we age, it's not a guarantee.

We may find ourselves in a place where we are cared for by strangers, where those who shepherd us through to our conclusion are neither family nor part of a now-faded social circle.

If that is how we age, then we need to prepare our souls with the discipline of loving strangers. Because how we treat those who tend to us and get us to the toilet and clean and feed our frail bodies will matter. If we resent or fear the different, belittle or denigrate those who care for us? We ourselves will be diminished, not just physically, but spiritually.

Christian faith teaches us to be humble, to accept care with grace, to consider every soul we encounter as a human person worthy of love. The time to start practicing that discipline of the heart is right now. Do you love the stranger? Do you treat those around you with patience and respect, no matter their social status, or your relationship to them?

Are you eager to hear their stories, to connect to the personhood of those you find around you? Have you allowed the Spirit to root out your pride and bitterness, fear and resentment? The one who finds us and cares for you, after all, will be our neighbor.

June 29, 2023

Preparing our Souls for Aging - Love 1

At the heart of the Christian faith, there is our assertion that God is love. Without that claim, that God exists and that the nature of the Divine is love, all of the other assertions of our faith crumble to dust. And sure, yeah, I know, we make a But at their core, they are refined into a single orientation of the soul. We are to love the God whose nature is love.

The love commandment is the bedrock assertion of all Christian theology, the self-declared summation of all of the ethical teachings of Jesus. Wisdom without love is little more than cunning. Hope and Faith may abide, but the greatest of these is Love. Jesus folk know all of these things, if they've been paying even the slightest little bit of attention.

As we age, love must remain as the sure foundation of our souls. If we are to age well, and to endure our winter season, we must hold fast to love. Pretty words, sure, but as I have noted elsewhere, they mean little if we don't understand the reality to which they point.

Placing the love of a loving God at the heart of ourselves does two things as we age. First, it affirms our value as persons. Second, it connects us to others.

Loving God is a radical affirmation of the value of our personhood, a value that aging can challenge. As our bodies age, we become less employable. Less desirable. Less functional. Understood through the lenses of popular culture, we become at best "cute," in the sort of way that a French bulldog puppy is cute. "Awww, look at the cute oldster, thinking they're a person and all." At worst, we're a hindrance, an inconvenience that mumbles in the corner and smells like pee.

If we only define our value in cultural terms of ability, desirability, and marketability, age can become unbearable. We can lose our sense of worth, our sense that we have any value. Faced with our diminishment, we can give in to the demons of resentment, self-isolation, and despair.

With its assertion that God's love is absolute and unconditional, Christian faith challenges this mindset. We are not worthy of love because of what we can do, or for our wealth, or for our power. We are worthy of love because all of God's creatures are worthy of love. We bring nothing to that equation but our ability to accept that grace, and to love in return.

That is true in our youth, and at the height of our adult abilities. It will remain equally true when we feel the weight of the years in our knees, and most of life has become a memory. We are called to love God with all our heart, all our mind, all our strength. Nowhere in that foundational injunction is there any mention made of it being a competition. Or that being loved and lovable requires us to be at our peak.

We struggle with that, as we wane in life's sky. We can have trouble seeing who we are, when our former ability fades.

L was a remarkably capable man. Short and wiry, neatly but casually dressed, with a bright welcoming smile beneath a solid head of white hair, he was the longest standing member of my congregation when I started there O So Many years ago.

He was a former Navy man, which mattered to him, and a woodworker, which seemed to matter just as much. He made perfectly crafted children's toys, little trucks and cars that were as meticulously assembled as anything you might find in a high-end bespoke plaything boutique for the overtherapied children of Manhattan socialites. They were simple and beautiful, the handiwork of an artisan. He would donate them for sale at church auctions.

The work of his hands was everywhere. The pulpit in our tiny sanctuary sat atop a rickety prefab platform when I started there, wobbling and shaking at any movement. Collapse always seemed like a possibility, and for liturgists who were unsteady on their feet, it wasn't the best thing.

One Sunday, I arrived to find that L had built a new platform. Just up and done it. Sturdy, hardwood, and pleasing to the eye, it was as solid as a concrete foundation. He was a blessing to the church for decades and decades, and much loved by everyone.

Then L had a stroke.

"He doesn't want visitors," I was told by church folk, so I called him instead. I didn't hear back, so I called again. I reached him, and he clearly but pleasantly reiterated that request. No, he didn't need or want me to call on him. His voice was slightly muted, but still very much himself. "No, I'd rather not have contact. I'm fine. I don't want you to visit or call."

He was very clear. He was not a "lost sheep." He said, explicitly, that he wished to be left alone. Others who reached out did not hear back, or were told the same thing.

That was his choice, and it was to be respected. I'm a pastor, not a stalker. Still, it was hard. A little heartbreaking, for those who loved him. L was an able man for his whole life, one who valued his ability and his competence. He didn't want to be tended to. He didn't want to be cared for. He wanted to contribute, and be valued for his contributions.

With his capacity diminished, it was hard for him to embrace his belovedness. To see his value, absent his ability to be as he had been.

It made the subsequent years of aging...and his final passing...harder. If we are to be prepared for that time, we need to understand our value as Jesus would have us understand it.