Michael Patrick Hicks's Blog, page 10

September 21, 2018

Review: The Bedding of Boys by Edward Lorn

The Bedding of Boys

By Edward Lorn

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

Nevada Barnes is your average, run of the mill, hormonally supercharged fourteen-year-old. Regina Corsi, however, is decidedly atypical - a woman in her thirties, she is a hebephile and a serial killer. She seduces children, uses them to satiate her sexual desires, and then brutally murders them. Aiding her in her crimes is a strange white sheeted creature, appropriately named Ghost, who consumes Regina's victims and scrubs clean the various crime scenes in supernatural ways. Once Regina lays eyes on Nevada, neither of their lives will ever be the same...nor, I'm sure, will the small Ohioan town of Bay's End.

The Bedding of Boys is the third in Edward Lorn's Bay's End novels (there's a few short stories and novellas sets within this town's borders, as well), and although each can be read as a stand-alone work there's a hell of a lot of richness to be found throughout this series when taken as a whole. The End, as it's colloquially known, has a lot of history behind it and when read as a series you get the feel of a fully realized town, recognizing its familiar landmarks, shops, and citizens, as well as the seedy underbelly infecting this region. Bay's End is for Lorn what Derry and Castle Rock are for Stephen King. You don't have to read these books in any particular order, but I strongly recommend familiarizing yourself with Lorn's Bay's End and The Sound of Broken Ribs before hitting the sheets with this one. Feel free to ignore my advice, of course, but I suspect you'll want to know all you can about The End and its inhabitants well before this book reaches its climax.

Fair warning, though - Lorn gets into some highly fucked up terrain here. The primary thrust behind The Bedding of Boys involves a significantly older woman seducing boys much, much younger than she. Regina is, simply put, a child rapist. Lorn pulls absolutely zero punches, and right from the book's very first chapter reader's are forced to bear witness to a handful of murders and a graphically detailed sexual assault of a minor. It's shocking and vulgar and deeply unsettling, and it sets the stage for all that follows. Once Nevada is introduced in the wake of Regina's bloody mayhem, you'll instantly worry for him and your anxiety will rise in creepily steady fashion as he becomes intimately familiar with Regina.

Sex is filtered through the perspective of predator and prey, and whatever glimmers of romantic entanglements these characters may feel, Lorn never shies away from the horrific manipulations behind all of it. This isn't a Happily Ever After romance - this is straight-up horror. Sex here is a weapon, and it is wielded with profoundly deadly intent time and time again. Sex and horror have been intertwined forever, oftentimes purely for sheer titillation, or to make a point about female purity. This last point you can most surely disregard, as ain't nobody in Bay's End pure.

The Bedding of Boys has a surprising amount of depth in its themes of sexual conquest, gender roles, and the animalistic nature of passion and the pursuit for sexual pleasure. Sex begets life, and life begets death. Sex and Death are the Alpha and the Omega, and carnality comes with a cost for each and every one of these characters, rippling through time to warp both minds and bodies alike.

Like Stephen King and George R.R. Martin, Lorn enjoys flicking readers around like a yo-yo. He'll give you plenty of characters to care about, and he does an absolutely fantastic job writing teenage boys (as evidenced in the prior Bay's End), only to sucker-punch you and pull the rug out from beneath your feet. This an author who profoundly destroys his characters with masochistic glee, and there were a few times I wanted to reach out to him and ask him to stop, to leave these people alone, to not devastate them so utterly. But, hell, if I did that, it'd kinda ruin the whole point here, wouldn't it?

There's a darkness in Bay's End. You can't plead with it, and you can't stop it. You can feel the way it eddies through the streets, disrupting the whole town and its people's lives. You can feel it building toward something, too, all throughout The Bedding of Boys. Something cataclysmic. All things lead to The End, after all.

View all my reviews

September 18, 2018

Review: Fear: Trump in the White House by Bob Woodward

Fear: Trump in the White House

By Bob Woodward

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

Fear: Trump in the White House breaks absolutely zero new ground. Anybody who has been following the Trump trainwreck already knows everything they need to know about Donnie Small-Hands and then some (for instance, today's big news stories revolve around Stormy Daniels's allegations that Trump has a small mushroom-shaped dick, news that is also not very surprising in and of itself). Those who are part of the Resistance will find nothing fresh within these pages. Those who are Trump supporters will, of course, brush Bob Woodward's account off as little more than "fake news" and part of the on-going "witch hunt" within the media and the whole wide world at large.

Woodward's accounting, though, does lend further credibility to ousted White House staffers who have used their executive positions to pen their own tell-all novels, and further solidifies those stories published in legitimate mainstream press outlets (i.e. not Fox News). As half of the reporting team that took down Nixon, Woodward's reportage on the Trump administration is certainly welcome, as he is a credible voice, a reporter with a through-line of integrity that has been a member of the press for decades. His writing here gives us a fly-on-the-wall picture of life in Trump's Oval Office, quoting a number of administration officials such as Gary Cohn, Rob Porter, Lt. General Michael Flynn, Secretary of Defense James "Mad Dog" Mattis, Reince Preibus, and others. Woodward lets the words of these men tell the story, free of any colorful commentary or opinionated editorializing.

All of the principle players paint a strikingly similar portrait of Trump, and it's a familiar view, one that anybody who has been paying even the absolute most minimum amount of attention since the 2016 primaries would recognize. Trump is inarticulate, incurious, a compulsive liar, brash, addicted to Twitter, quick to anger, both wildly ignorant and profoundly stupid, unimaginative, and dead set in his ways. He's inflexible and unwilling to change his mind or opinions on anything, including his own deeply racist attitudes, as exhibited throughout his presidential campaign, again in the wake of the Charlottesville rioting, and yet again when discussing African nations, their inhabitants, and immigrants, as well as resolutely sexist. He has not a single shred of understanding of government, diplomacy, the military, or the economy. And, again, none of this news, nor is any of it surprising.

Because of the author's singular focus on the White House and its central players, Woodward forgoes any deeper examinations of Trump and his attitudes. Rather than an in-depth profile of the man who invented Birtherism conspiracy theories, we get the popular sketch version we see every day on the nightly news and live on Twitter. What we're told fits the common vernacular surrounding Trump, but there's never any attempt to dig deeper. Part of the sad thing (if one can ever manage to drum up anything resembling sympathy for such a rotten and disingenuous figure as Donald Trump), of course, is that any of Trump's own depth is merely skin-deep artifice. Simply put, there is nothing deeper to him. What you see is literally what you get. At the end of the day he's just another bitter, angry old man stuck in the past, sitting around watching Fox News and trying to convince everybody he's as great as he thinks he is, complaining about all the non-white men in the world. There's no question Trump thinks highly of himself, just as there's no question that his opinion is completely unfounded in fact. Facts, we know, are the one thing Trump hates perhaps more than anything, and his staffers routinely commiserate over how difficult it is to convince Trump of reality and how pointless it is for them to prepare daily briefings for him because he refuses to read

anything

.

So, is Fear worth reading? Honestly, I'm not entirely sure it is, particularly if you've already been following along since the oaf took his oath. It's a quick read, the writing breezy but plain, and Woodward certainly lives up to Christopher Hitchens's criticism of being little more than a stenographer to the stars. More than a year and a half into this national nightmare, Fear: Trump in the White House offers little in the way of actual news, and Trump's detractors will certainly find all of their worst suspicions and fears about the man confirmed. Trump's blind supporters, though, I suspect, aren't likely to ever bother reading this thing to begin with. The target audience, then, is simply the curious among us, those hoping to uncover revelations or maybe look back at the early days of this administration and chuckle knowingly to how things have played out since Jan. 2017. At one point, for instance, Trump is reported to have asked his staffers, responding to allegations in the Steele document, if he looks like a guy who needs prostitutes. I'm sure we all had our suspicions on that front, and, well, we definitively know the answer to that now, at least.

View all my reviews

September 17, 2018

Review: Scapegoat by Adam Howe and James Newman

Scapegoat

By Adam Howe, James Newman

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

2018 has been a phenomenal year for reading, with a number of titles already in the running for my best of the year list, but in terms of sheer entertainment value alone Scapegoat will be a hard one to beat.

Adam Howe and James Newman have written one hell of a crackling read here with a story that is all about the escalation of threats. Mike Rawson, Lonnie Deveraux, and Pork Chop are travelling by RV to attend WrestleMania III, accompanied by Cindi the Bar Girl, who just so happens to be way more than she appears. After taking a drug and booze-fueled detour, the gang find themselves lost in the woods, a situation Lonnie worsens even further when he accidentally runs over a woman fleeing for her life. Turns out, the woman’s own situation is damn severe even before she found herself on the wrong side of a speeding RV – she has been beaten and cut up from head to toe, the seven deadly sins engraved on her skin. Stopping to help her puts the guys right into the crosshairs of the men chasing her – a band of redneck cultists hell-bent on reclaiming their sacrificial scapegoat.

Scapegoat is just all kinds of wild, and if you’ve read Howe’s two Reggie Levine novels previously you already know redneck backwoods shenanigans is this dude’s bread and butter. This is an odd thing, indeed, as Howe is a Brit, but thanks to American globalism and the spread of Hollywood commercialism in particular, it’s pretty clear he grew up on a steady of diet of Burt Reynolds flicks like Smokey and the Bandit and Deliverance. Howe is apparently obsessed with crafting the ultimate cross-over between these films, at least when he’s not obsessing over Nic Cage movies and skunk apes. But, you know what? I honestly wouldn’t have it any other way. Howe gets it and he knows how to craft a damn fine story that chugs along with the speed and grace of the Bandit’s own Trans Am.

To sweeten the pot even further, though, is fellow Howe fan James Newman, author of Odd Man Out, who also wrote an introduction to Howe’s Tijuana Donkey Showdown and shares co-writing credit here. Newman, hailing from the American south, clearly knows his way around the backwoods, too. Both authors inject in Scapegoat a clear affinity for wrestling, heavy metal, and Lost In The Woods And Chased By Maniacs horror. In terms of collaboration, it’s pretty clear these two guys are writing with a singular purpose and a shared hive mind. And once they get going, there’s no slowing them down.

Scapegoat is a quick, down and dirty kind of read, pared to the bone and trimmed of all the fat. While plenty of the book is a run-and-gun affair, we still get some great character beats and moments of introspection and reminiscing that illustrate the relationship between Mike, Lonnie, and Pork Chop. There’s also plenty of carnage, threatening portents of occultism, explosions galore, moments of wonderfully shocking violence, and an incredible climax that spins this story into some wonderfully dark realms. Now look, I would have been more than content to have Howe and Newman tell me a story of redneck cultists chasing after our lost losers, but the few extra miles they travel in upping the ante here is absolutely perfect. The ending in particular is incredibly gutsy and I had to take a few moments to simply appreciate the verve of these authors.

Scapegoat is a mile-a-minute blast, the type of book that’s pure joy fuel. You might even be compelled to hop into an RV and storm into the Tennessee woods looking for trouble. Just remember, those seven deadly sins serve as a warning for a reason…

[Note: I received an advance reading copy of this title from the authors to provide a publication blurb. I have chosen to review Scapegoat here as well because I just flat-out loved this damn thing.]

View all my reviews

September 15, 2018

Review: My Pet Serial Killer by Michael J. Seidlinger

My Pet Serial Killer

By Michael J. Seidlinger

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

In a crowded bar, you watch the patrons around you, sizing up a potential partner and the potential competition. You see something you like, a particular hair color or style, a smile, nice arms, nice legs, a nice chest, a pretty face or a handsome jawline. They catch you watching. Signals are exchanged, subtle but inviting. You make your move, your approach invited, expected, desired. There is, for at least a brief moment, and maybe longer if you're lucky, potential. You've been looking for certain attractive qualities, waiting for that one person who is a match. Such is the way of dating. But, what if you're looking for more than a common date? What if you're looking for, say, a serial killer?

This is, at its earliest and most basic, the premise of Michael J. Seidlinger's My Pet Serial Killer. Claire is a student studying forensic science, but she has some very particular fetishes and she knows how to find those particular qualities that she finds desirable in a mate with unerring accuracy. She could, presumably, easily become a victim, but some mysterious kink in the rules of attraction gives her an upper hand, as it has with Victor, dubbed the Gentleman Killer by the media at large.

Serial murder is most often about power and control, and is typically inextricably tied to sexual pleasure. In the world of BDSM, those who possess positions of power in their daily life often seek out sexually submissive roles in their carnal affairs. I'm sure we've all heard stories about the powerful executive who absolutely dominates the boardroom during the day, only to frequent certain types of clubs at night where he can be handcuffed and spanked. It makes sense, in certain perverse ways, that a serial killer, whose carnal activities are literally matters of life and death, who possess total and complete power over another, would enter into a submissive affair. After all, don't serial killers need love, too, and what would be the nature of their relationships?

Enter Claire. Smart and domineering, she makes killers her pets. She breaks them down piece by piece, destroying their defenses until they are left entirely subordinate to her, until a serial rapist and murderer like Victor is left wearing nothing more than a leash and literally licking her kitchen floor clean.

My Pet Serial Killer is as much about psychosexual fantasy and fetishes as it is about murder, and Seidlinger puts all of it on graphic display for readers. Perhaps more than any of these, though, My Pet Serial Killer is all about voyeurism. Claire rigs her home with webcams so she can watch Victor at work with his prey, and they routinely speak via computer chat programs like FaceTime. Written in first person, Claire tells her story directly to readers. Other chapters tell us of the eventual movie and television series based on Claire's work and relationships.

Seidlinger himself uses these various techniques and this story as a whole to riff on the relationship between his readers and the appeal that serial killer stories hold for them. Serial murderers are certainly fascinating taboo subjects, and it's fair to say there is a certain voyeuristic allure to such crimes. In both fiction and true crime works, the serial killer genre allows readers to explore dark fantasies, real or imagined, and observe horrifying experiences, descend into psychological madness, and escape all of it free from any lasting harm. We watch, disconnected and safe, seeking some degree of satisfaction from such stories. We seek understanding in the unraveling of these mysteries of a serial killer's mind, and in this understanding we've come to dominate the killer, being neither a victim nor the incarcerated murderer, reducing these crimes and the various actors within to little more than digestible forms of entertainment, making these brutal acts of atrocity and those who commit them submissive to our own morbid curiosities. We have made them into little more than performers.

My Pet Serial Killer is an interesting and intense meditation on the relationship between killers and the women who derive companionship from them, while also establishing a meta connection between the readers and the material. Claire is a forensic scientist, but Seidlinger demands that we be forensic readers, studying the crimes and the relationships presented to us to unravel the mystery, while also examining our own relationship to that which we are consuming. Is Claire any better than the killers she has dominated since the burgeoning of her sexuality, directing them to kill for her entertainment, and even going so far as to supply them with their victims and bury the evidence? Are we any better than Claire in our search and consumption of such stories, particularly true crime narratives in which actual human beings have been murdered in awfully grisly ways so that we can gaze salaciously upon them for a few hours of entertainment?

Seidlinger brings an uncomfortable fourth dimension into the equation, subverting ones typical expectations of a serial killer horror novel if you're willing to dig deeply enough and get your hands dirty. You can certainly enjoy My Pet Serial Killer on a superficial level, digging into it for its brutal kill scenes and kinky sex, but it's a far more engaging and rewarding read when approached with thoughtful deliberation and a bit of psychological studiousness. To get the most out of My Pet Serial Killer requires a willing degree of complicity and submissiveness. How you'll fare with it, though, is all part of the mystery.

[Note: I received an advance reading copy of this title from the publisher, Fangoria.]

View all my reviews

September 14, 2018

September 12, 2018

Review: The Dragon Factory (Joe Ledger #2) by Jonathan Maberry [audiobook]

The Dragon Factory: A Joe Ledger Novel

By Jonathan Maberry

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

Only two books in and the Joe Ledger series has become a fast favorite of mine. Maberry effortlessly entwines a wide range of genres - military thriller, horror, science fiction, comic book action - to create an incredibly entertaining and compulsively listenable story.

In The Dragon Factory the extinction clock is ticking, counting down to global genocide. Cyrus Jakoby is a brilliant geneticist, his research building off the horrific medical tests conducted by Nazi scientists in World War II, and he has perfected the ultimate means to deliver the Final Solution and offer the white race complete domination over the Earth. It's up to Captain Joe Ledger and Echo Team to stop them, but time is running out and the Department of Military Sciences are caught off guard, stuck playing catch-up after inter-agency politics prompts the NSA to curtail their investigations.

There's a lot going on in The Dragon Factory and Maberry is an expert wrangler, maintaining almost complete control of the story's various plot threads and its multitude of characters. There's enough 24 and James Bond-style shenanigans and to keep listeners thoroughly engaged. The Jakoby family themselves are practically plucked right out of a Bond flick, with the incestuous albino assassin twins of Paris and Hecate conducting their own secret science experiments on a secluded island research base. Not every story thread gets wrapped up sufficiently (but hey, more fodder for book #3!), and some story elements simply fall by the wayside along the way to larger, more intriguing action sequences until they're briefly revisited and fairly neatly and quickly resolved in the book's epilogue, but taken as a whole The Dragon Factory is consistently good and completely captivating.

Published in 2010, The Dragon Factory feels less outlandish today than it may have at the start of this decade, as some of its more seemingly implausible aspects have been fulfilled in reality in only a handful of years. Take, for instance, the subject of white supremacists manipulating and controlling the White House and various government agencies, plotting to destroy the world by poisoning Earth's waters. Certainly this seemed more far-fetched in 2010, but here we are in 2018 with a band of white supremacists in the Oval Office, passing bills allowing our waters to be poisoned by mining waste and appointing the enemies of various government agencies to lead those very same agencies, like the EPA, and withdrawing from the Paris Climate Accord, and placing immigrant children in concentration camps, and on and on and on. Sadly, the idea of virulently evil racists plotting to destroy the world from within America and through a network of highly-placed and influential government agents isn't quite the extraordinarily imaginative work of fiction it used to be.

Besides the white supremacist bad guys, Maberry injects a metric ton of cutting edge science and plausible-enough horrors stemming from transgenic experimentation to create superhuman animal hybrids to give Ledger and company a savagely violent run for their money. Using the concept of scientific terrorism to fuel a series also gives Maberry a hell of a lot of elasticity in redefining the shape and scope of various horror genre staples. In Patient Zero, Maberry wrote about a militarized unit's response to the zombie plague. Here, we get rogue government operators, assassins, and a bevy of massive, berserker monsters, alongside a spate of other genre concepts.

It's clear Maberry is having a ton of fun writing this stuff, and his enthusiasm is infectious. The Dragon Factory is awful lot of fun to listen to, and Ray Porter delivers another knock-out reading as he firmly settles into these characters and brings them to life (and in more than a few instances death as well). He manages to make each of the characters distinct, utilizing tonal ranges, inflections, and accents to differentiate Maberry's large cast, always making it clear which character is speaking at any given moment. His is a pitch perfect narration, hitting the highs of each action scene and the softer lows of emotional reflection and devastation. Porter further solidifies the simple fact that he is the definitive voice of the Joe Ledger series, and I can't imagine listeners wanting it any other way.

Patient Zero instantly hooked me, roping me into the thick of things and making me a Joe Ledger devotee. The Dragon Factory shows that this series most certainly has legs, and that it can run for miles. While the action is fast and fluid, this is a series that is more than just muscular brawn - it has a hell of a lot of smarts, too, both on and off the page.

View all my reviews

September 10, 2018

Review: Red War (Mitch Rapp #17) by Kyle Mills

Red War (A Mitch Rapp Novel)

By Vince Flynn, Kyle Mills

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

Red War, the seventeenth Mitch Rapp thriller and fourth penned by Kyle Mills, finds the CIA assassin on a mission to execute the Russian president, Maxim Krupin. Recently diagnosed with terminal brain cancer, Krupin has grown ever more unpredictable and uses his final months to further consolidate his power, executing his enemies and political rivals, as he takes the world to the brink of World War III.

As with Tom Clancy before him, Vince Flynn's series has always been rather timely in its reflections on current events. Red War is no different, with Mills setting Krupin's actions and the CIA's response in the wake of Russian hacking efforts to disrupt US elections. One would have to be blind to miss the real-world context Mills uses as a spring broad to launch into his story of black ops and Krupin is most certainly a familiar character right from the book's opening pages.

Described as a president who keeps his citizens blinded with nationalism and memories of his country's glorious past, Krupin's behavior is irrational and erratic, his power built on a platform of lies he has told both enemies and allies in order to erode trust in anyone or anything beyond himself. If Krupin is not immediately recognizable to American readers as a Trump analogue, in addition to an obvious riff on Vladimir Putin, then he is most certainly the kind of dictator the United States's manchild of a president openly worships and models his own behaviors upon. With regular reminders that this physically and mentally ill state-head is in possession of nuclear arms, Krupin is broadcast as a legitimate threat (and by association, his real-world counterparts that so clearly served as an inspiration here) to democratic norms and the safety of the free world.

Mills gives us a nice bit of escapism in Mitch Rapp gunning for Krupin, aided by former Russian assassin Grisha Azarov, who is violently pulled out of retirement to aid the CIA's efforts, particularly after the last several years of the US falling victim to Russian hacking efforts. As Rapp notes at one point, Russia will never be an ally to the US but they can at least be contained. The promise of the CIA delivering justice in fiction is a soothing and necessary, if short lived, balm, especially since our real-world government is content to simply maintain complicity in exchange for power. It's safe to say Mitch Rapp is needed now more than ever.

Mills continues to build on Flynn's characterization of Rapp, as well, helping to move the assassin away from the buffoonish conservative cartoon he was becoming in Flynn's later novels, edging him closer and closer to the methodical and thoughtful man of action audiences were first introduced to in Transfer of Power nearly twenty years ago. Mitch has survived a lot since then; those experiences have helped to both age and wisen him, and he's been a significant player on the global stage. It's refreshing to see Mills break away from the typical Arab threat that has been the backbone for so many of Rapp's stories, moving him into strange and unfamiliar territory with this book's Russian theater of opposition.

Red War arrives at a crucial juncture in American history, and carries with it a decidedly appropriate title. Particularly given that this book's biggest problem, potentially, may lie in convincing those Trump supporters who read it to accept Russia as a legitimate threat, even if only fictionally. Clearly, we've come a long way since the "Better Dead Than Red" days of the Cold War, but with Emily Bestler Books planning national ad campaigns to put Red War in front of the audiences of Fox & Friends and Rush Limbaugh, one must wonder just how receptive they'll be of Mills' very thinly-veiled repudiation of their red hatted leader and their likely-stained "I'd Rather Be A Russian Than A Democrat" t-shirts. Are MAGA readers willing to accept government operatives as heroes after being spoonfed so many reports of so-called fake news in regards to Russian meddling in US affairs and attacks on the various justice agencies by their Dear Leader? On the other hand, if the publisher is merely looking for an audience already lost in a fantasy world, you can't do much better than consumer's of Limbaugh and Fox News.

[Note: I received an advance reader's copy of Red War from Emily Bestler Books after being selected as a Mitch Rapp Ambassador. This is my third year as a Mitch Rapp Ambassador, however this status conveyed upon me by the publisher has in no way swayed my opinion of this work or prevented me from delivering an honest review of this title. Many thanks to the publisher for once against selecting me and providing me with this ARC.]

View all my reviews

September 6, 2018

Review: Bay's End by Edward Lorn

Bay's End

By Edward Lorn

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

REMINDER: 3 stars on the Goodreads metric means "I liked it" and is in no way, shape, or form a negative rating. And in fact, I did like Bay's End, even as I have some mixed feelings about it.

I believe Bay's End was Edward Lorn's first novel (although I could be wrong!), and it serves as a fine introduction to the town and landscape where a number of his other later works are set. It does have some of the creakiness and odd pacing issues of first novels, but as a coming of age story it also has plenty of heart and honesty, as well as a group of teens worth rooting for, and a clean, easy-going writing style that makes it compulsively readable.

I must note, though, that I came into Bay's End having already read Lorn's incredible novel, The Sound of Broken Ribs, my #1 pick for best book of 2017, and in preparation for his latest release, The Bedding of Boys. While these are each stand alone titles, these initial two books are separated by a number of years wherein Lorn grew tremendously as an author. I don't mean this as a knock, nor do I wish to infer that Bay's End is by any means a bad book. It's actually quite a fine introduction to Lorn's style, a style that he has honed and improved on over the course of his career. We must all being somewhere, though, and Bay's End is a bit of a time capsule in that regard, and a fitting one at that.

The story itself is a time capsule, as a haunted man recalls the summer of 1992. Then, Trey was twelve going on thirteen, and he's made a fast friendship with the new neighbor kid, Eddy, a bond that will last all of Trey's life, long after Eddy's untimely demise. It's a summer of first loves, near-death accidents, and the intrusion of adulthood upon adolescence far too soon. Eddy is foul-mouthed and brash, and after they run afoul of Officer Mack he has the bright idea of tossing cherry bombs into the cop's patrol car. It's a moment that changes the course of these boy's lives forever and embroils them in larger events, sinking them into the meaner, darker secrets hidden in Bay's End.

As I said, I came into Bay's End after The Sound of Broken Ribs and a few of Lorn's other short horror stories, so color me surprised at the total lack of supernatural elements! I admit, I was expecting some kind of monster to rear its ugly head, and while there is definitely a fair share of ugly heads a-rearing, the horrors herein are strictly human. Bay's End, as we discover alongside Trey, has its fair share of dark corners and corrupted souls.

My chief issue with the book, though, comes down to pacing. There were times where it simply felt like the story was moving too fast, and I wanted Lorn to ease off the gas pedal and explore the town and its people a bit more. Instead, we kind of race from one set piece of action to the next and there's not a lot of time to decompress and regroup. Such is the way of those teenage years, though, always on the go, in a hurry to get to the next big thing and rush through it for whatever next big thing lies beyond. As it is, Lorn covers a lot of ground and stumbles across a few unsavory characters along the way, but it also feels like an awful lot of stuff happening too soon.

Mostly, I just wanted to spend more time with Trey, Eddy, Candy, and Sanders. I wanted to see more of their hijinx and eavesdrop on their foul-mouthed and unerringly accurate teenage talks. Adult Trey tells the part of his psyche haunted by Eddy and the ghosts of '92 that this is a story of only a few miles, but I could have gone for a longer journey and wouldn't have minded clocking a few more miles through Bay's End.

View all my reviews

Flame Tree Press Launches Today!

Launching today are the six inaugural titles from Flame Tree Press. Over the last month or so, I've been working my way through advance review copies of these launch titles from Jonathan Janz, Hunter Shea, Tim Waggoner, and Ramsey Campbell.

David Tallerman, and J.D. Moyer are also making their Flame Tree Press debuts with The Bad Neighbor (a crime thriller) and The Sky Woman (sci-fi), respectively. Unfortunately, I haven't been able to dig into those two non-horror releases just yet, as I've had a bit of a time crunch between getting sick, my two boys and my wife getting sick, and the whole lot of us going round-robin again and again with various batches of illnesses cooked up by our daycare's biohazard division. By all means, though, click on through to check out those book's Amazon pages for more information on 'em.

Of the four horror titles I was able to read, though, I was largely impressed with Flame Tree's debut, and I am genuinely looking forward to see how this publisher shapes up in the coming months and years. If this first batch of books is anything to go by, Flame Tree most certainly deserves your support and attention, and I hope they're able to stick around for a good long while. Click on the cover images below to read to my review and visit the link within to purchase your copy of these books from Amazon.

In the coming weeks, I'll have reviews of more forthcoming Flame Tree Press books, including John Everson's The House by the Cemetery and D.W. Gillespie's The Toy Thief. I'll also be circling back around to Tallerman's and Moyer's book, as well. Stay tuned!

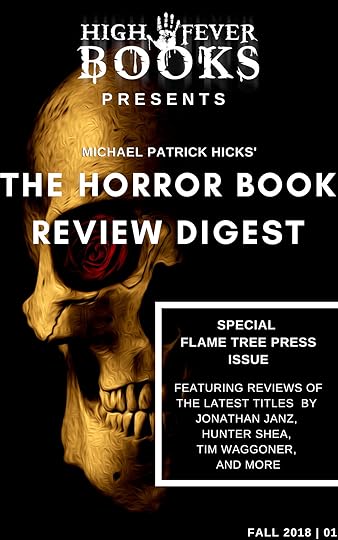

You can also find each of these Flame Tree Press reviews collected in the first issue of The Horror Book Review Digest.

This quarterly publication reviews the latest horror novels, novellas, and short stories published by the Big 5, small presses, independent authors and publishers, and emerging voices in horror, as well as less recent, classic, and soon-to-be classic horror titles.

In this debut release, horror author and HWA member Michael Patrick Hicks reviews new releases from Stephen King, CV Hunt, Rio Youers, John Connolly, Mary SanGiovanni, Jonathan Maberry, and Paul Tremblay. This volume also features reviews for each of the six launch titles from Flame Tree Press, a brand-new genre imprint launching in September with titles from Jonathan Janz, Hunter Shea, Ramsey Campbell, and others, as well as Fangoria’s book publishing debut with their title, Our Lady of the Inferno by Preston Fassel. Plus, we take a look back at the classic Jack Ketchum novels, Off Season and The Girl Next Door, as well as Brian Keene’s Darkness on the Edge of Town, and many, many more.

This special first volume of The Horror Book Review Digest features reviews of over 50 books that promise to give you chills and nightmares. Settle in, keep a light on, and find your next read.

September 3, 2018

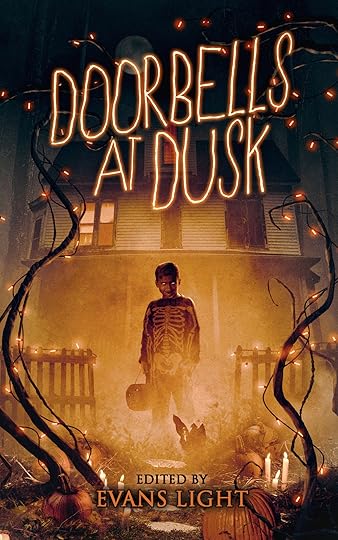

Review: Doorbells at Dusk: Halloween Stories, edited by Evans Light

Doorbells at Dusk

By Josh Malerman, Evans Light, Jason Parent, Gregor Xane, Adam Light

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

Nothing says Halloween quite so much as a new horror anthology devoted to carved pumpkins, witches, ghouls, and murder as we turn toward the darker half of the year. Doorbells at Dusk is a solid entry into the annals of such anthologies, gathering fourteen short stories from a range of the horror genre's talents like Josh Malerman, Amber Fallon, Chad Lutzke, and more.

Doorbells at Dusk showcases a broad range of Halloween horror themes, as well. There are some truly fun and occasionally depraved and psychotic stories (my favorite kind, personally), as well as gentler, spookier slice of life riffs. I always find anthologies to be a mixed bag, and this latest from Corpus Press proves to be no exception. While there a few stories I didn't care for, I still found plenty of others that impressed and delivered exactly what I was looking for in terms of haunting effectiveness and unbridled mayhem. Most of these latter were from authors whose works I've enjoyed in the past, and I found them delivering the best of the bunch here.

Adam Light's "Trick 'Em All" was easily my favorite of this antho. As I said, I like my Halloween stories depraved and bloody, and Light delivers with his story of a psychotic teen receiving messages from his newly carved pumpkin to kill his family. This is a brutal, crazy gorefest and I'll be damned if it wasn't straight up my alley.

Jason Parent serves up a fun little treat as a group of thieves break into the wrong house in "Keeping Up Appearances." Gregor Xane's "Mr. Impossible" is a fun bit of science gone wonky as a neighorhood is drugged and costumers believe they actually are whatever they are dressed as. "Rusty Husky," from Dusk's editor Evans Light, delivers on its premise of revenge on a serial killer in a nastily inventive way that's all about its tricks and treats.

Amber Fallon's "The Day of the Dead" puts a cool little The Twilight Zone spin on Día de los Muertos, one that will definitely make you want to dress up for Halloween this year. Chad Lutzke's "Vigil" goes in an entirely different direction and stands proudly as a bit of the odd man out here. Eschewing the paranormal entirely, Lutzke focuses on a different sort of monstrosity altogether as a stunned and shaken neighborhood gathers to watch the police discover and exhume a score of bodies from an abandoned house. There's no shocks or scares, but Lutzke writes so well, and so honestly, that this small town vignette captivates the whole through. Sean Eads and Joshua Viola present a historical slow-burn work of Halloween horror that good and truly sticks the landing once the full scope of "Many Carvings" atrocities are fully revealed.

Doorbells at Dusk is a welcome addition to the pantheon of Halloween horrors. Not that this is much of a shock, mind you. Evans Light knows how to deliver a great Halloween antho; you don't need to look past any of the three Bad Apples books he co-created to find proof of that, and Doorbells at Dusk serves as further evidence to this claim. Doorbells at Dusk, in fact, is a natural outgrowth from those earlier anthologies, and this one is larger and more diverse in both its stories, their premises, and contributors. Unlike Bad Apples, though, it also seems rather deliberately aimed at a wider, more general audience of horror readers, forgoing the occasionally vulgar, gruesome, splatterpunk sensibilities of its harder-edged, dare to offend cousins. This isn't a bad thing, certainly, but I still found myself wanting Doorbells at Dusk to get a bit meaner and dirtier than its raison d'être permitted. It's safe to say, though, that Light has deftly generated a small library of Halloween attractions to satisfy any number of tastes.

Doorbells at Dusk presents a fine sampling of tricks and treats for readers jonesing for some good and proper seasonal reads as the leaves turn color, a chill sets in, the world turns a little bit darker, and it arrives just in time as the membrane separating this world from another grows thinner and thinner day by day.

[Note: I received an advanced reading copy of this title from the publisher, Corpus Press.]

View all my reviews